ABSTRACT

Interprofessional education (IPE) in Ireland is at an early stage. Currently, there is no data to reflect the amount and type of IPE occurring across the Island of Ireland. To support IPE implementation, data is needed on existing IPE which will identify gaps and foundations on which to build. We designed a cross-sectional, online, anonymous survey to map geographical IPE locations, IPE setting, and type of IPE offered. Results were analyzed by exporting raw data to Microsoft Excel. The survey was completed by 21 participants. Over half of participants (n = 12) came from two professions: physiotherapy and speech and language therapy. Participants were from 4 counties (from a potential 32): Cork, Dublin, Galway, and Limerick. There were twice as many university educator participants (n = 14) as compared to clinical educators (n = 7). Shared modules and guest lectures from other professions were frequent methods of shared learning. At university level the most frequent IPE activity was interprofessional problem-based learning/case study. At clinical sites students interact with a range of qualified professionals and have limited opportunities to work with students from other professions. This may impact the range of collaborative work skills developed and thus readiness for workforce entry.

Introduction

Interprofessional education is growing and evolving globally (Clark & Formosa, Citation2017), as the need for collaborative ready graduates increases (World Health Organisation, Citation2010). The COVID-19 pandemic has provided a clear illustration of the need for a flexible workforce with the skills to work within and across professions to meet emergent healthcare needs (Goldman & Xyrichis, Citation2020). Thus, it is timely to consider how students are being prepared for workforce entry. For example, to what degree do students engage in shared or multiprofessional learning (learning side by side), as compared to IPE (learning with, from, and about each to develop collaborative working skills; Barr, Citation2002), and furthermore, how is IPE delivered at university and clinical sites (Morison et al., Citation2003).

In Ireland, as in many countries, there is limited information available about IPE on a national scale, as it is organized at a local level across academic and university sites (O’Leary et al., Citation2019). Furthermore, as IPE facilitation is typically carried out as an additional aspect to other educational roles (Bennett et al., Citation2011), it is difficult to know to what level staff are involved in IPE. Yet to properly plan for future IPE and optimize student preparation for collaborative practice as graduates, it is necessary to understand what is already occurring at a national level. Therefore, we developed a mapping survey to capture IPE in both academic institutions and clinical sites across the Island of Ireland.

Contact theory asserts that bringing students together from different professions is not sufficient to achieve meaningful collaborative learning; rather certain conditions such as purposeful activity and equal status must be put in place (Carpenter & Dickinson, Citation2016). Drawing on contact theory provided a lens through which to frame and interpret findings beyond simple description.

Methods

A cross-sectional anonymous survey was developed by the authors. Survey items were informed by contact theory and the author’s IPE experience. Items related to geographical location, work location, and a description of IPE in a range of settings. To enhance content validity, an initial draft of the survey was distributed to members of a national IPE Special Interest Group for review and editing. Members had both topic and methodological experience as they work in clinical, academic, and research settings. The survey was revised following this process. All educators working in either academic or practice education settings and involved in designing, delivering, or evaluating IPE were eligible to participate. Non-probability sampling was used to recruit participants who met the inclusion criteria. Participants were recruited through professional network mailing lists and social media advertisements.

The survey was open from 22nd September to 12th October 2020. Participants were provided with a statement of consent prior to commencing the survey and ticked the associated box to indicate consent and commence the survey. Ethical approval was received from the School of Medicine Research Ethics Committee at Trinity College Dublin (Application No: 20,200,603).

Results were analyzed by exporting raw data to Microsoft Excel, which allowed for descriptive analysis of the data using summation and charting functions

Results

Responses were received from 21 respondents, spread across four (from a potential of 32) counties. Nine professions were represented in the results. Respondents were primarily from the professions of physiotherapy (n = 6) and speech & language therapy (n = 6), with one or two each from seven other professions including nursing and dentistry. Almost twice as many respondents were primarily affiliated with a university (n = 14) as compared to clinical sites (n = 7; ). The amount of time dedicated to IPE varied between respondents. Eight participants reported it was less than 10% of their time, five respondents reported between 10–20% and five respondents reported 40–50% (three non-responses to this item).

Table 1. Participant Demographics.

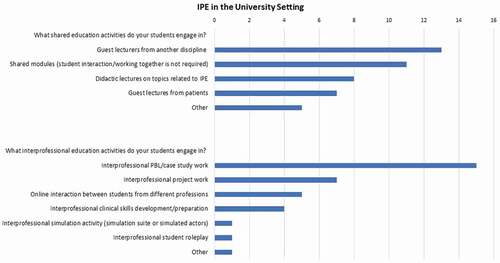

There were 43 instances of shared learning and 36 instances of IPE reported from universities. The most common shared learning activities were guest lectures by other professions (n = 13) and shared modules (n = 11). The most common IPE activity was interprofessional problem-based learning/case study work (n = 15), followed by interprofessional project work (n = 7) and interprofessional clinical skills development/preparation (n = 6). Reported methods of IPE assessment included team-based projects (n = 6) and reflective journaling (n = 4) (See, )

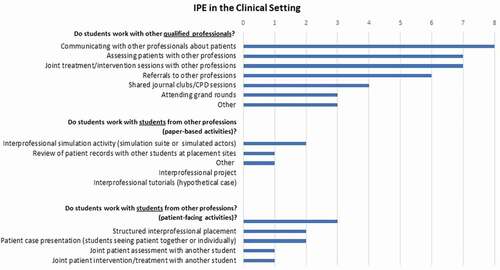

At clinical sites there were 36 reports of opportunities for working with other professionals, with 17 for student – student IPE working (paper and patient-based activities). The most reported student – student IPE activity was case presentation to educators on a patient that students are seeing (together or individually) (n = 4) (see, ).

Discussion

Survey results support the hypothesis that IPE is at a developmental stage on the Island of Ireland. In this discussion we expand on findings and develop recommendations to inform educational practice. These data indicate that within the settings engaged in IPE, there is more IPE occurring at university than clinical sites. Moreover, all respondents were from the counties with affiliated universities. This would indicate that even at clinical sites, it is those proximate to the universities that engage in IPE. As students attend placements nationally, this result implies that IPE opportunities at clinical sites are currently limited. It also highlights the benefit of having support available from a university site. With the increased use of technology in frontline healthcare services it may be possible to support the extension of IPE to clinical sites further from university settings. Targeted support to develop IPE at clinical sites is warranted as new graduates have indicated that IPE during clinical placements had the greatest influence of their graduate collaborative working (Gilligan et al., Citation2014). Collaborative working between university and placement educators is needed to support IPE during clinical placements (O’Leary et al., Citation2020).

Interprofessional problem-based learning/case study work was the most common IPE activity in university settings. Allport proposes conditions in Contact Theory for group interactions that lead to meaningful change (Mohaupt et al., Citation2012). These included having opportunities for cooperative working on a common goal (Hean & Dickinson, Citation2005). Interprofessional problem-based learning and case studies allow for this. Furthermore, this is a model that could be transferred to the clinical setting, where there are existing examples of case-based IPE activities (Nasir et al., Citation2017).

At present students have more opportunities to work collaboratively with qualified professionals than students from other professions. While this can lead to meaningful learning outcomes, there are limitations. Allport also proposed equal status as a condition necessary for changes to result from group work (Hean & Dickinson, Citation2005). During a clinical placement students and qualified professionals do not have equal status, there is a real power parity even if the qualified professional is not the student’s supervisor. Developing skills such as conflict resolution and leadership are among the core objectives of IPE (O’Keefe et al., Citation2017). Yet in a student – qualified professional interactions opportunities for developing these skills will be limited. Adopting the lens of contact theory, we can see that the condition of equity between individuals is not met in a student – qualified professional relationship (Hean & Dickinson, Citation2005).

The limited number of responses to this survey may reflect that a wider and more focused distribution strategy was required. For example, emailing individual hospital managers. However, it may also reflect that IPE is currently facilitated by a small number of educators. Globally a reliance on pockets of champions has long been acknowledged as a challenge to IPE (Steketee & O’Keefe, Citation2020). The results of this survey indicate that at a national level dedicated IPE educator training is required to support more educators become involved in IPE delivery. On a larger scale we also need to consider where IPE sits as an educational priority. Accreditation standards serve as powerful leverage for establishing new models such as IPE within curriculums and IPE is typically poorly represented (Bogossian & Craven, Citation2020). For IPE to become embedded in healthcare curriculums and more widely adopted, greater integration into accreditation standards is required.

Conclusion

This survey provided a descriptive snapshot of IPE on the Island of Ireland at present. This paper reflects a jurisdiction where IPE is at an early stage and rarely has dedicated posts or resources to support implementation. As such findings may be relevant to other countries in similar situations. Implementation of the recommendations can support further evolution of IPE beyond its current formative stage and enhance student preparation for workforce entry. Indeed, it will be important to report and document national level developments as IPE continues to evolve. This will allow for tracking of workforce preparation and development over time. This paper can serve as a preliminary foundation for such research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Noreen O’Leary

Noreen O'Leary: Noreen, a qualified speech and language therapist, completed her PhD in interprofessional education at the School of Allied Health, University of Limerick. Noreen's research relates to practice-based interprofessional education and seeks to reflect the experiences of a range of stakeholders, influenced by principles of Public Patient Involvement. Other research interests include professional identity and socialisation, pedagogical theories and the application of qualitative research methodologies.

Dr Emer Guinan

Emer Guinan: Assistant Professor in the School of Medicine with responsibility for the Interprofessional Learning programme for the Faculty of Health Sciences. Emer's main research interest is in the role of exercise and physical activity in ameliorating treatment side effects and optimising survivorship for patients with cancer.

References

- Barr, H. (2002). Interprofessional education. Today ,Yesterday and Tomorrow. A review: The Learning and Teaching Support Network for Health Sciences & Practice. https://www.unmc.edu/bhecn/_documents/ipe-today-yesterday-tmmw-barr.pdf

- Bennett, P. N., Gum, L., Lindeman, I., Lawn, S., McAllister, S., Richards, J., Kelton, M., & Ward, H. (2011). Faculty perceptions of interprofessional education. Nurse Education Today, 31(6), 571–576. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2010.09.008

- Bogossian, F., & Craven, D. (2020). A review of the requirements for interprofessional education and interprofessional collaboration in accreditation and practice standards for health professionals in Australia. Journal of Interprofesional Care, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2020.1808601

- Carpenter, J., & Dickinson, C. (2016). Understanding interprofessional education as an intergroup encounter: The use of contact theory in programme planning. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 30(1), 103–108. https://doi.org/10.3109/13561820.2015.1070134

- Clark, P. G., & Formosa, M. (2017). Global trends in interprofessional education in aging and health: Program development and evaluation. Innovation in Aging, 1(suppl_1), 77. https://doi.org/10.1093/geroni/igx004.318

- Gilligan, C., Outram, S., & Levett-Jones, T. (2014). Recommendations from recent graduates in medicine, nursing and pharmacy on improving interprofessional education in university programs: A qualitative study. BMC Medical Education, 14(1), 52. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6920-14-52

- Goldman, J., & Xyrichis, A. (2020). Interprofessional working during the COVID-19 pandemic: Sociological insights. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 34(5), 580–582. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2020.1806220

- Hean, S., & Dickinson, C. (2005). The Contact Hypothesis: An exploration of its further potential in interprofessional education. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 19(5), 480–491. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820500215202

- Mohaupt, J., van Soeren, M., Andrusyszyn, M.-A., Macmillan, K., Devlin-Cop, S., & Reeves, S. (2012). Understanding interprofessional relationships by the use of contact theory. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 26(5), 370–375. https://doi.org/10.3109/13561820.2012.673512

- Morison, S., Boohan, M., Jenkins, J., & Moutray, M. (2003). Facilitating undergraduate interprofessional learning in healthcare: Comparing classroom and clinical learning for nursing and medical students. Learning in Health and Social Care, 2(2), 92–104. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1473-6861.2003.00043.x

- Nasir, J., Goldie, J., Little, A., Banerjee, D., & Reeves, S. (2017, January). Case-based interprofessional learning for undergraduate healthcare professionals in the clinical setting. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 31(1), 125–128. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2016.1233395

- O’Keefe, M., Henderson, A., & Chick, R. (2017, May). Defining a set of common interprofessional learning competencies for health profession students. Medical Teacher, 39(5), 463–468. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159x.2017.1300246

- O’Leary, N., Salmon, N., & Clifford, A. M. (2020). Inside-out: Normalising practice-based IPE. Advances in Health Sciences Education. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-020-10017-8

- O’Leary, N., Salmon, N., Clifford, A., O’Donoghue, M., & Reeves, S. (2019). ‘Bumping along’: A qualitative metasynthesis of challenges to interprofessional placements. Medical Education, 53(9), 903–915. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.13891

- Steketee, C., & O’Keefe, M. (2020). Moving IPE from being ‘worthy’ to ‘required’ in health professional curriculum: Is good governance the missing part? Medical Teacher, 42(9), 1005–1011. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2020.1774526

- World Health Organisation. (2010). Framework for Action on interprofessional Education & Collaborative Practice. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/70185/WHO_HRH_HPN_10.3_eng.pdf;jsessionid=3351451835E915FF721E06BD01FA054A?sequence=1