ABSTRACT

Practice-based interprofessional education (IPE) is both a valuable and complex model of practice education. To support educators design, deliver, and implement high-quality practice-based IPE, this guideline was developed in conjunction with a placement profile. Underpinned by educational theory, this guideline and placement profile identifies key factors to consider before, during, and after practice-based IPE. Development of the profile has involved interprofessional collaboration as well as international feedback via conference workshops. The profile has been trialed in two clinical sites involved in practice-based IPE and refined following consultation with and feedback from educators. Educators can also use the profile to track site development over time and evidence resource and support requirements. Through use additional features may become relevant and users are encouraged to add or amend as is most beneficial to their site.

Introduction

Practice-based interprofessional education (IPE) refers to pre-licensure students learning together in clinical settings (Morphet et al., Citation2014). It has unique educational value, allowing students to translate IPE theory into practice (Thistlethwaite, Citation2013). Furthermore, Gilligan et al. (Citation2014) have recognized that practice-based IPE enhances collaborative practice as a clinician. Theoretically, any placement site that receives students from more than one health professional programme has the potential for practice-based IPE (Dean et al., Citation2014). However, practice-based IPE is often an ad hoc aspect of placement curriculums, dependent on local champions (Missen et al., Citation2012). While logistical and administrative issues contribute to this (Rodger et al., Citation2008), limited planning and implementation guidelines for educators involved in practice-based IPE perpetuate these challenges. Regulatory standards of proficiency underpin placement curriculums, outlining competencies required for students to be practice ready. In Ireland programme accreditation is often provided by the regulatory body, though this may vary internationally. Therefore, it is important to ensure alignment and integration of these guidelines in the design, delivery, and implementation of practice-based IPE. This can also increase educator and student engagement with IPE. However, it is not feasible within these documents to provide guidance about implementation of practice-based IPE. As such, educators require specific support to underpin IPE in the clinical context and ensure students have adequate supports and opportunities for developing collaborative working competencies required for clinical practice. The aim of this paper is to present a guide and corresponding profile that will help clinical sites plan for practice-based IPE. It is likely most useful for settings where student placement is locally managed between academic and healthcare sites and for those who may be in the early stages of developing practice-based IPE.

Interprofessional Education and Practice Guides such as Anderson et al. (Citation2016), Brewer and Barr (Citation2016) and Lie et al. (Citation2016) have provided useful overviews and discussions of factors for educators to consider when setting up and run practice-based IPE. However, in practical terms these are not designed as functional tools that can be used by educators. Practice-based IPE tools such as Points for Interprofessional Education System (Centre for Interprofessional Education, Citation2013) address issues such as curricular alignment as opposed to providing detailed guidance for educators planning practice-based IPE. Corresponding guides such as “Facilitating interprofessional clinical learning: Interprofessional education placements and other opportunities” (Sinclair et al., Citation2007) offer practical suggestions for facilitating practice-based IPE but are not designed to capture site capacity and development over time. Others such as the “IPL for Placements” resources (University of Sydney, Citation2018) are designed to capture student experience and learning. A recent publication by Derbyshire and Machin (Citation2021) included a Practice-Based IPL Multi-Dimensional Assessment Tool to help healthcare teams assess site feasibility for practice-based IPE. While this tool considers issues relating to culture, structure, and agency there is a greater focus on evaluation than implementation. Therefore, this profile was developed to support implementation of practice-based IPE at clinical sites, by outlining features to consider and providing guidelines for developing site readiness and capacity for practice-based IPE.

Guideline and profile development

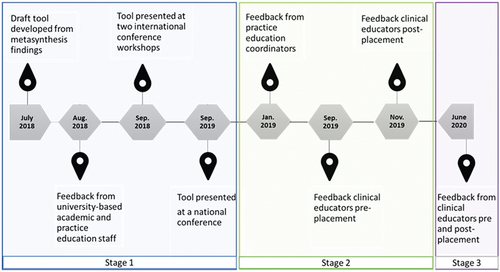

The opportunity to develop this profile and guideline emerged during a doctoral project at a school of allied health. The focus of this doctoral project was integrating practice-based IPE across healthcare curriculums (O’Leary et al., Citation2019). The stages of development, trialing, and refinement of this profile are summarized in . Development included input from academic and practice education staff based at the university, as well as trialing by clinical educators working at two placement sites. Both sites were based in the Republic of Ireland and provided adult rehabilitation services. The professions of speech and language therapy, occupational therapy, physiotherapy, dietetics and social work were represented at these sites. The profile was also presented at two international conferences. During interactive workshops, conference participants applied the profile to their own settings and provided feedback which led to further refinement. In later stages clinical educators provided feedback on their experiences of using the profile to plan and evaluate practice-based IPE, which can be found in Supplementary Material.

A lack of theoretical underpinning for IPE initiatives and resources is an issue that interprofessional researchers and educators have been striving to address over the last number of years (Danielson & Willgerodt, Citation2018). Moreover, theory can draw attention to covert factors which impact education models such as practice-based IPE (Hean et al., Citation2018). This profile is informed by the presage-process-product (3P) educational theory (Biggs, Citation1993). This theory aligned well with phases of practice-based IPE, addressing key stages from planning the placement (presage), to running the placement (process) and evaluating the placement (product). The 3P theory has previously been used to explore development and progression of IPE models, for example, Freeth and Reeves (Citation2004) and Reeves et al. (Citation2016). Several guideline development tools were considered to support rigor and transparency when developing this guideline and profile (Moher, Citation2018), including Phillips et al. (Citation2016), Brouwers et al. (Citation2016), Schünemann et al. (Citation2014), and Chen et al. (Citation2017). For this project, the Reporting Tool for Practice Guidelines in Health Care (RIGHT tool; Chen et al., Citation2017) was deemed most suitable. Details can be found in Supplementary Material.

Implementing the profile

The profile is organized into three sections: presage, process, and planning. Educators are prompted to consider how well equipped or prepared their site is for practice-based IPE, considering a range of features ahead of, during, and after the placement. It is designed for flexible use by educators involved in planning practice-based IPE and could involve academic and /or clinical educators or hired preceptors, depending on local or national arrangements. Educators could complete the profile individually but completion as a team can help develop shared understanding and consensus among team members. If completed by a team, the profile can be reviewed periodically, and profiles compared longitudinally. Each feature should ultimately be rated to reflect the overall team level of skill or capacity, considering the collaborative working required for practice-based IPE. A numerical scale is not provided as this could imply an arbitrary cutoff for when a site should or should not proceed with practice-based IPE. Rather this profile is designed to help educators identify areas of strengths, areas requiring development, plan for site development and track progress at clinical sites over time. Supplementary Material includes educator experiences of using the profile during stages two and three. A copy of the placement profile is available in Supplementary Material.

Practice-based IPE profile: key concepts

Presage

Organizational support (1.1)

The concept of organizational support alludes to the personnel involved in managing the service delivery at the level of line management and the overall culture of team working and collaboration within the organization. Inclusion of students as part of the team, where management acknowledge the role of students and encourage educators to engage in innovative practice education such as practice-based IPE lends to the development of a positive culture (Miller et al., Citation2019). Considering how to develop or harness this type of support ahead of practice-based IPE can be beneficial. For example, highlighting how practice-based IPE supports national or local health organization priorities. Organizational support could also take the form of interprofessional scheduling collaboration across the academic and practice educator collaboration to ensure that opportunities for students to be on placement at the same time as optimized, as well as accounting for practice site requirements.

Physical resources (1.2)

Practical elements such as having physical space for students and access to IT resources can have a significant impact on the overall success of practice-based IPE (Brewer et al., Citation2017). Designated or bookable physical spaces allow for collaborative teaching and learning activities. It can also be helpful for students to have space for collaborative planning and reflecting (Boshoff et al., Citation2020). Given the increased use of telehealth platforms since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, availability of IT resources such as webcams and secure consultation platforms should also be considered. Indeed, these may mitigate challenges relating to physical space constraints.

Service-user needs (1.3)

Service-user need for collaborative input is an important consideration. Involvement of service-users in practice-based IPE should be based on clinical need, balancing potential benefits with any risks. Ideally service user representatives should be represented at the design stage of the placement and input into placement design (Vijn et al., Citation2018). Patient ability to give consent should be considered prior to commencement.

Educator skills and knowledge in practice education (1.4)

This includes educator skills and knowledge of supervising students in their own profession. Educators with previous involvement in practice education will have existing skills to draw on and will also have familiarity with profession specific requirements. While there is no definitive requirement for level of experience it may be prudent to ensure each educator has at a minimum supervised one uniprofessional placement prior to supervising students during practice-based IPE. Developing bespoke practice-based IPE training may support educator capacity and recruitment, increasing practice-based IPE stability.

Educator skills and knowledge for practice-based IPE (1.5)

It is acknowledged there are specific facilitation skills required for practice-based IPE (Grymonpre, Citation2016). These include an ability to recognize the perspective of multiple professions, manage group dynamics and apply principles of adult learning (Centre for the Advancement of Interprofessional Care, Citation2021). Educators may have acquired such skills through previous involvement in practice-based IPE, attending training events or through their own experiences of IPE or collaborative working. Open communication regarding differing levels of skill and knowledge can allow team members support each other.

Student preparation (1.6)

Access to pre-placement resources relating to the practice-based IPE aspect of their placement can help students prepare for and optimize learning from practice-based IPE (Grace & O’Neill, Citation2014). This could include advance reading material and examples of potential student activities and student roles. Where feasible meeting students as a group ahead of placement or for a joint orientation meeting may support team formation (Nisbet et al., Citation2016). It is also relevant to consider factors such as student stage of training and previous IPE experience and insofar as possible try to mitigate the impact of any differences during pre-placement preparation.

Dedicated educator time for practice-based IPE facilitation (1.7)

As educators are balancing simultaneous clinical and educator roles during practice-based IPE, allocating time for practice-based IPE facilitation prior to commencing the placement is advised. Due to the team nature of practice-based IPE this could be shared among educators. Activities could include group supervision or case reviews as is most appropriate to the site. Allocating time to these activities ensures they occur and demonstrate that practice-based IPE is valued by the team.

Regulatory requirements (1.8)

Professional regulatory requirements influence engagement with practice-based IPE (K. Steven et al., Citation2017). For example, in Ireland the multi-professional regulator accredits many healthcare training programmes and sets the standards required for new graduates entering practice. If IPE is a regulatory requirement of healthcare programmes the placing institutions will need to work with clinical partners to ensure that IPE happens on placement and that this is evidenced. As such identifying and drawing attention to collaborative competencies for the professions involved is worthwhile, as it may increase student and educator engagement. Differences in regulatory requirements among professions may impact placement design and should be explored at the planning stage.

Process

Interprofessional culture among educators (2.1)

Students are highly influenced by how educators perform their role. Therefore, it is important to think about the culture of collaborate working among educators. Educators need to model the type of working they are asking students to engage in (Croker et al., Citation2016). If students perceive educators do not truly value collaborative working, meaningful engagement with and learning from practice-based IPE will be diminished. Therefore, educators need to carefully consider how their existing work practices will be perceived by students and how these align with the aims of practice-based IPE. It is important to note here that this item is not seeking a situation where there is no uniprofessional activity or even professional disagreement. Rather it is considering how educators approach working with other professions, negotiate conflict and generally interact as healthcare professions within a team.

Team configuration (2.2)

The clinical site interprofessional team configuration is an important consideration in terms of interpersonal relationships. In our experience if the team is stable and well established, it is more likely that a placement will be facilitated. If the team includes personnel that are on temporary employment, or new members of staff, it is less likely the team will commit to establishing practice-based IPE as they are still learning about each other. However, the potential of newly developed or re-configured teams that are keen to develop practice-based IPE should not be discounted. Newly formed teams who have good collaborative working relationships may be able to offer beneficial practice-based IPE, with appropriate support from the organization and placing university.

Student access to supervision (2.3)

It is important that provision is made for student supervision. While the format of this may vary depending on site, student stage, and the level of risk associated with the practice-based IPE activities, opportunities to reflect on IPE activities is important. For example, this may be incorporated into their standard professional supervision. Where possible it is worth considering whether supervision specific to practice-based IPE could be offered to the students as a group, potentially by a profession neutral facilitator (that is a facilitator not from the students’ own professions). It is also beneficial if all student supervisors can highlight the supporting the value of practice-based IPE, even during uniprofessional supervision.

Educator mentoring (2.4)

The development of communities of practice, for clinicians interested in practice education and practice-based IPE especially may help to support IPE in practice. Strong collegial relationships can enable realization of plans for practice-based IPE and support on-going development and evaluation. In our experience, when onsite clinicians have a direct communication pathway to academic or clinical colleagues, they feel more included and valued as educators. This may not always be feasible and onsite peer support may be more accessible. This could take the form of onsite educators allocating time for peer supervision or mentoring. Frequency of these sessions will be influenced by clinical and other demands and use of technology may help reduce time and logistical demands. If the university can facilitate mentoring for educators this could also be supportive, and illustrate that supporting educators is valued and create opportunities for developing educator networks.

Planned IPE activity /opportunities (2.5)

While unplanned teaching and learning activities will happen by virtue of being in the same place at the same time, planned learning activities should form part of the placement. This allows for equity of opportunity among students in terms of demonstrating skills and achieving identified learning outcomes.

Student and educator resources for practice-based IPE (2.6 – 2.8)

During practice-based IPE resources are required to plan for and reflect IPE activities, as well as to capture unplanned IPE activities. These resources can be locally developed and where possible should draw on theoretical and educational concepts. Previously developed tools are also available online from several healthcare providers and universities, a sample of which are included in Supplementary Material. Existing tools that invoke IPE principles can also be used. For example, the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health framework and the Meet, Assess, Goal-Set, Plan, Implement and Evaluate (MAGPIE) model have been used for these purposes (Cahill et al., Citation2013). Reflective processes such as the Gibbs cycle (Gibbs, Citation1988) can be adapted for use during practice-based IPE.

Product

Student assessment (3.1)

Assessment is a driver of learning (Cecilio-Fernandes et al., Citation2018) and this holds true in the case of practice-based IPE. Interprofessional competencies are included as a component of many standard student assessment forms such as the physiotherapy Common Assessment Form (Coote et al., Citation2007). Clearly outlining how practice-based IPE activities map onto professional competencies from the outset can enhance student engagement (Nisbet et al., Citation2016).

Team evaluation (3.2)

Evaluation of practice-based IPE can vary in formality. Internally staff involved may reflect and debrief following the placement. However, capturing the key learnings from each placement can help plan for future placements. There is also scope to use the profile to guide post-placement review through a dedicated column. Documenting post-placement evaluations can form a record to evidence development of the site for practice-based IPE over time and to highlight the need for resources such as space to management.

Service-user and student feedback (3.3 – 3.4)

Service-user and student feedback should also be sought about practice-based IPE as they are key stakeholders. For service users existing service feedback measures could be adapted to include feedback on this aspect. It would be important to highlight the sections specific to practice-based IPE to avoid conflation with the overall healthcare experience. For both groups’ options for anonymous feedback or via personnel not involved in their care or education may be required to allay concerns regarding the impact of unfavorable feedback. Where feasible online platforms may offer a convenient method of gathering feedback.

Conclusion

This guide and accompanying profile are designed to support educators navigate the complexity of practice-based IPE. While the profile is designed to be comprehensive it is not exhaustive, and we encourage educators to add to and adapt as needed for their setting. Use of this profile may also highlight needs for dedicated funding or strategic partnerships between academic and placement settings. This information can support inter-organizational lobbying to provide supports for practice-based IPE.

Contributions

Noreen O’Leary and Nancy Salmon developed the concept and the initial drafts of the profile and guideline. Marie O’Donnell, Saerlaith Murphy and Joanne Mannion trialled and provided feedback on the profile. All authors contributed to the writing of the manuscript. All authors have approved the submission.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (274 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the contributions of the following people:

Ms Mairead Cahill, Dr Pauline Boland, Dr Karen McCreesh, Dr Louise Larkin, Ms Fiona McDonald, Ms Aoife McGuire, Ms Eimer Ní Riain and Ms Irene O’Brien at the School of Allied Health, University of Limerick for their feedback on the initial iterations of this profile

The IPE Team in National Orthopaedic Hospital Cappagh who piloted the tool, Alison Brennan (Clinical Specialist Physiotherapy Practice Tutor), Jemma Henry (Senior Dietitian), Emma Nolan (Senior Occupational Therapist) and Andrea Ward (Senior Medical Social Worker).

The team of practice educators and practice tutors in the Intermediate Care Facility, University of Limerick Hospital Group, University of Limerick including Aoife McCarthy (Senior Occupational Therapist), Mary Flahive (Physiotherapy Practice Tutor), Scott Murphy (Physiotherapy Practice Tutor) and Sarah Kennedy (Physiotherapy Practice Tutor).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplemental Material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2022.2038551

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Noreen O’Leary

Noreen O'Leary: Speech & Language Therapist and Lecturer with special interest in interprofessional education, qualitative research and paediatric disability.

Nancy Salmon

Nancy Salmon: Occupational Therapist and Lecturer with special interest in equity and social justice, community engagement, person-centred professional practice and interprofessional healthcare education.

Marie O’Donnell

Marie O'Donnell: Physiotherapist and Practice Education Coordinator, with special interest in curricula design and development, innovations in practice education, ensuring quality in placement delivery and interprofessional education in practice placement settings

Saerlaith Murphy

Saerlaith Murphy: Speech & Language Therapist and Practice Tutor specialising in acute and subacute rehabilitation of acquired communication and swallowing disorders and interprofessional education

Joanne Mannion

Joanne Mannion: Speech & Language Therapist and Practice Tutor experienced in Acute and Primary Care settings working with adult populations and experienced in facilitating interprofessional education.

References

- Anderson, E. S., Ford, J., & Kinnair, D. J. (2016). Interprofessional education and practice guide no. 6: Developing practice-based interprofessional learning using a short placement model. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 30(4), 433–440. https://doi.org/10.3109/13561820.2016.1160040

- Biggs, J. B. (1993). From theory to practice: A cognitive systems approach. Higher Education Research & Development, 12(1), 73–85. https://doi.org/10.1080/0729436930120107

- Boshoff, K., Murray, C., Worley, A., & Berndt, A. (2020). Interprofessional education placements in allied health: A scoping review. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy in Health Care, 27(2), 80–97. https://doi.org/10.1080/11038128.2019.1642955

- Brewer, M. L., & Barr, H. (2016). Interprofessional education and practice guide no. 8: Team-based interprofessional practice placements. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 30(6), 747–753. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2016.1220930

- Brewer, M. L., Flavell, H. L., & Jordon, J. (2017). Interprofessional team-based placements: The importance of space, place, and facilitation. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 31(4), 429–437. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2017.1308318

- Brouwers, M. C., Kerkvliet, K., & Spithoff, K. (2016). The AGREE reporting checklist: A tool to improve reporting of clinical practice guidelines. British Medical Journal, 352, i1152. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i1152

- Cahill, M., O’Donnell, M., Warren, A., Taylor, A., & Gowan, O. (2013). Enhancing interprofessional student practice through a case-based model. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 27(4), 333–335. https://doi.org/10.3109/13561820.2013.764514

- Cecilio-Fernandes, D., Cohen-Schotanus, J., & Tio, R. A. (2018). Assessment programs to enhance learning. Physical Therapy Reviews, 23(1), 17–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/10833196.2017.1341143

- Centre for Interprofessional Education. (2013). Points for interprofessional education system (PIPEs). University of Toronto. Retrieved May 11 2019. https://www.ipe.utoronto.ca/sites/default/files/PIPEs%20Information%20Package.pdf

- Centre for the Advancement of Interprofessional Care. (2021). Interprofessional education handbook: For educators and practitioners incorporating integrated care and values-based practice. Retrieved October March 28 2021. https://www.caipe.org/resources/publications/caipe-publications/caipe-2021-a-new-caipe-interprofessional-education-handbook-2021-ipe-incorporating-values-based-practice-ford-j-gray-r

- Chen, Y., Yang, K., Marušic, A., Qaseem, A., Meerpohl, J. J., Flottorp, S., Akl, E. A., Schünemann, H. J., Chan, E. S., Falck-Ytter, Y., Ahmed, F., Barber, S., Chen, C., Zhang, M., Xu, B., Tian, J., Song, F., Shang, H., Tang, K., … Norris, S. L. (2017). A Reporting tool for practice guidelines in health care: The RIGHT statement. Annals of Internal Medicine, 166(2), 128–132. https://doi.org/10.7326/M16-1565

- Coote, S., Alpine, L., Cassidy, C., Loughnane, M., McMahon, S., Meldrum, D., O’Connor, A., & O’Mahoney, M. (2007). The development and evaluation of a common assessment form for physiotherapy practice education in Ireland. Physiotherapy Ireland, 28(2), 6–10.

- Croker, A., Smith, T., Fisher, K., & Littlejohns, S. (2016). Educators’ interprofessional collaborative relationships: Helping pharmacy students learn to work with other professions. Pharmacy, 4(2), 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy4020017

- Danielson, J., & Willgerodt, M. (2018). Building a theoretically grounded curricular framework for successful interprofessional education. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 82(10), 1133–1139. https://doi.org/10.5688/ajpe7075

- Dean, H. J., MacDonald, L., Alessi-Severini, S., Halipchuk, J. A. C., Sellers, E. A. C., & Grymonpre, R. E. (2014 8 January). Elements and Enablers for Interprofessional Education Clinical Placements in Diabetes Teams. Canadian Journal of Diabetes, 38(4), 273–278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcjd.2014.02.024

- Derbyshire, J.A. & Machin, A. (2021) The influence of culture, structure, and human agency on interprofessional learning in a neurosurgical practice learning setting: a case study. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 35(3), 352–360. doi: 10.1080/13561820.2020.1760802

- Freeth, D., & Reeves, S. (2004). Learning to work together: Using the presage, process, product (3P) model to highlight decisions and possibilities. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 18(1), 43–56. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820310001608221

- Gibbs, G. (1988). Learning by doing: A guide to teaching and learning methods. Further Education Unit Oxford Polytechnic.

- Gilligan, C., Outram, S., & Levett-Jones, T. (2014 March 18). Recommendations from recent graduates in medicine, nursing and pharmacy on improving interprofessional education in university programs: A qualitative study. BMC Medical Education, 14(1), 52. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6920-14-52

- Grace, S., & O’Neill, R. (2014). Better prepared, better placement: An online resource for health students. Asia-Pacific Journal of Cooperative Education, 15(4), 291–304. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1113558

- Grymonpre, R. E. (2016). Faculty development in interprofessional education (IPE): Reflections from an IPE coordinator. Journal of Taibah University Medical Sciences, 11(6), 510–519. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtumed.2016.10.006

- Hean, S., Green, C., Anderson, E., Morris, D., John, C., Pitt, R., & O’Halloran, C. (2018). The contribution of theory to the design, delivery, and evaluation of interprofessional curricula: BEME Guide No. 49. Medical Teacher, 40(6), 542–558. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2018.1432851

- Lie, D. A., Forest, C. P., Kysh, L., & Sinclair, L. (2016, May). Interprofessional education and practice guide No. 5: Interprofessional teaching for prequalification students in clinical settings. J Interprof Care, 30(3), 324–330. https://doi.org/10.3109/13561820.2016.1141752

- Miller, R., Scherpbier, N., van Amsterdam, L., Guedes, V., & Pype, P. (2019). Inter-professional education and primary care: EFPC position paper. Primary Health Care Research & Development, 20, e138–e138. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1463423619000653

- Missen, K., Jacob, E. R., Barnett, T., Walker, L., & Cross, M. (2012). Interprofessional clinical education: Clinicians’ views on the importance of leadership. Collegian, 19(4), 189–195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colegn.2011.10.002

- Moher, D. (2018). Reporting guidelines: Doing better for readers. BMC Medicine, 16(1), 233. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-018-1226-0

- Morphet, J., Hood, K., Cant, R., Baulch, J., Gilbee, A., & Sandry, K. (2014). Teaching teamwork: An evaluation of an interprofessional training ward placement for health care students. Advances in Medical Education and Practice, 5(5), 197–204. https://doi.org/10.2147/AMEP.S61189

- Nisbet, G., O’Keefe, M., & Henderson, A. (2016). Twelve tips for structuring student placements to achieve interprofessional learning outcomes. MedEdPublish, 5(3), 23. https://doi.org/10.15694/mep.2016.000109

- O’Leary, N., Salmon, N., Clifford, A., O’Donoghue, M., & Reeves, S. (2019). ‘Bumping along’: A qualitative metasynthesis of challenges to interprofessional placements. Medical Education, 53(9), 903–915. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.13891

- Phillips, A. C., Lewis, L. K., McEvoy, M. P., Galipeau, J., Glasziou, P., Moher, D., Tilson, J. K., & Williams, M. T. (2016). Development and validation of the guideline for reporting evidence-based practice educational interventions and teaching (GREET). BMC Medical Education, 16(1), 237. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-016-0759-1

- Reeves, S., Fletcher, S., Barr, H., Birch, I., Boet, S., Davies, N., McFadyen, A., Rivera, J., & Kitto, S. (2016). A BEME systematic review of the effects of interprofessional education: BEME Guide No. 39. Medical Teacher, 38(7), 656–668. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2016.1173663

- Rodger, S., Webb, G., Devitt, L., Gilbert, J., Wrightson, P., & McMeeken, J. (2008). A clinical education and practice placements in the allied health professions: An international perspective. Journal of Allied Health, 37(1), 53–62. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18444440/

- Schünemann, H. J., Wiercioch, W., Etxeandia, I., Falavigna, M., Santesso, N., Mustafa, R., Ventresca, M., Brignardello-Petersen, R., Laisaar, K.-T., Kowalski, S., Baldeh, T., Zhang, Y., Raid, U., Neumann, I., Norris, S. L., Thornton, J., Harbour, R., Treweek, S., Guyatt, G., & Akl, E. A. (2014). Guidelines 2.0: Systematic development of a comprehensive checklist for a successful guideline enterprise. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 186(3), E123. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.131237

- Sinclair, L., Lowe, M., Paulenko, T., & Walczak, A. (2007). Facilitating interprofessional clinical learning: Interprofessional education placements and other opportunitie. University of Toronto, Office of Interprofessional Education.

- Steven, K., Howden, S., Mires, G., Rowe, I., Lafferty, N., Arnold, A., & Strath, A. (2017). Toward interprofessional learning and education: Mapping common outcomes for prequalifying healthcare professional programs in the United Kingdom. Medical Teacher, 39(7), 720–744. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2017.1309372

- Thistlethwaite, J. (2013 6 January). Practice-based learning across and between the health professions: a conceptual exploration of definitions and diversity and their impact on interprofessional education. International Journal of Practice-based Learning in Health and Social Care, 1(1), 15–28. https://doi.org/10.11120/pblh.2013.00003

- University of Sydney. (2018). Interprofessional learning resources for placements. Retrieved Nov 16 2020. https://health-ipl.sydney.edu.au/

- Vijn, T. W., Wollersheim, H., Faber, M. J., Fluit, C. R. M. G., & Kremer, J. A. M. (2018). Building a patient-centered and interprofessional training program with patients, students and care professionals: Study protocol of a participatory design and evaluation study. BMC Health Services Research, 18(1), 387. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-018-3200-0