ABSTRACT

Increasing prevalence of chronic disease leads to an increased need for person-centered care. To prepare future health professionals for this need, educational institutions provide interprofessional education in which they actively involve patients (hereafter called experts by experience). The organization of inter-institutional, interprofessional education with the active involvement of experts by experience poses challenges. To overcome these challenges, a joint student- and expert by experience-led organization was established, named Patient as a Person Foundation. This organization functions as the linking pin between three educational institutions. Jointly, they enabled the involvement of 181 experts by experience in interprofessional education and 1313 students from nine study programs over the course of two curriculum years. To facilitate joint education involving patients, Patient as a Person Foundation realizes three main activities: (a) recruitment and instruction of experts by experience, (b) enabling the inter-institutional organization of education and facilitating its logistics and financing, and (c) universal training of teaching staff. This interprofessional Education and Practice Guide aims to provide lessons on how to sustainably organize interprofessional education involving experts by experience across multiple educational institutions. The key lessons provided in this guide, underpinned by research and key literature, aim to inspire and enable similar initiatives elsewhere.

Introduction

Worldwide there is an increasing prevalence of chronic diseases and multimorbidity (Hajat & Stein, Citation2018). This leads to an increased desire for person-centered care in which allied medical professionals jointly deliver and coordinate care and assist in reaching a meaningful life for the recipients of care (Eklund et al., Citation2019). To this aim, several recommendations for health professions education have been proposed (Frenk et al., Citation2010). One of these recommendations regards interprofessional education (IPE). IPE entails occasions when members or students of two or more professions learn with, from and about each other to improve collaboration and the quality of care and services (Centre for the Advancement of Interprofessional Education, Citation2016). Additionally, active participation of patients in IPE has been described as necessary to accommodate students with the partnership-ethos (i.e. shared decision-making, promotion of self-management) required for person-centered care (Towle et al., Citation2010). Orchard et al. (Citation2005) also underscore that the patient-partnership is at the center of collaborative practice, emphasizing the complementarity of patient-centered competencies and IPE competencies in educational activities. Furthermore, while communication skills can be taught successfully using simulated IPE activities, students appreciate the authenticity of real patients’ experiences (McKinlay et al., Citation2021; Teodorczuk et al., Citation2016). Understanding patients as persons and coordinating the delivery of care to their individual needs are recognized as vital in today’s healthcare environment and should therefore be focal points of IPE.

Hence, patients and their carers (to whom we will refer as experts by experience, or EBEsFootnote1 for short), should play a crucial role in IPE. However, this is challenging. Barriers include recruiting, training, and retaining EBEs as active participants in education (Happell et al., Citation2014). Additionally, studies report lacking reciprocity for EBEs, their authentic views being disregarded, being unaware of the context of the educational activity, not receiving feedback on the content and value of their contributions, and inappropriate reimbursement (Hunt et al., Citation2011). Similarly, integration of IPE into health professions training retains barriers, such as logistic-, assessment- and implementation challenges within institutions. Between institutions, it is even more difficult to integrate IPE as staffing and structures tend to differ and change regularly (Lawlis et al., Citation2014).

In this guide, we provide recommendations on how to overcome challenges relating to the inter-institutional organization of IPE involving EBEs. The recommendations are based on a Dutch example of a student- and EBE-led, not-for-profit organization that enables IPE focusing on learning competencies required for person-centered care. EBEs play an active role in this education, which is followed by students of three educational institutions and nine different study programmes. The so-called Patient As a Person Foundation (Dutch: Stichting Mens Achter de Patiënt) realizes three main activities: (a) recruitment and instruction of EBEs, (b) enabling inter-institutional organization of education and facilitating its logistics and financing, and (c) training of teachers of various institutions in facilitating uniform delivery and assessment of an educational format called the PAP-module (Box 1).

Table

Table

Background

The organizational structure of PAP-Foundation exists of an executive board and a supervisory board. The executive board consists of two full-time student-leaders, seven part-time voluntary student board members and three voluntary EBEs. The voluntary supervisory board is responsible for strategy, overseeing the executive board, and finances, and consists of a medical doctor, a treasurer in healthcare institutions, and a communication expert.

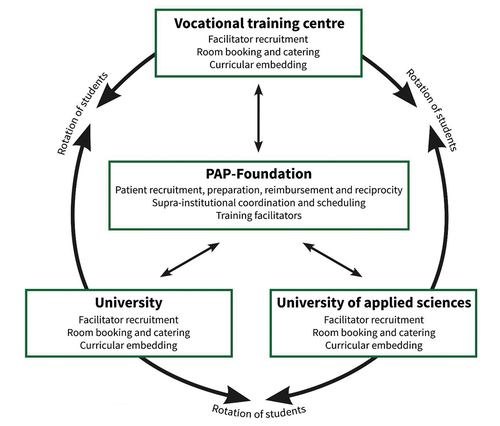

In the curriculum years 2018–2019 and 2019–2020, three educational institutions in the Netherlands jointly offered the PAP-module to a total of 1313 students (). In the Netherlands, three levels of tertiary education are distinguished: secondary vocational education, university of applied sciences and university. The three participating educational institutions all offered one of the three educational levels and were the three dominant educational institutions in the south of Limburg, a province in The Netherlands. An overview of the organization of the PAP-module and the respective responsibilities of main stakeholders are described in .

Table 1. Participants in PAP-module in the curriculum years 2018–2020.

Approach to implementing the PAP-module

The PAP-module started as a student-invented module and was scaled up over the course of three curriculum years. A pilot of 32 students in the curriculum year was followed by a pilot involving 222 in 2017–2018, to reach the end of the implementation phase in 2018–2019 with 669 students. Such gradual implementation was necessary to:

Improve the PAP-module by extensive evaluation: Extensive mixed-methods evaluations were undertaken to (1) identify improvements in the content and delivery of the PAP-module, (2) identify and tackle logistic challenges, and (3) assess whether the PAP-module was helpful for students in learning competencies required for interprofessional person-centered care (Romme et al., Citation2020). The student evaluation is summarized in Online Supplement I.

Expand the network of EBEs: The total number of individual EBEs who participated in the PAP-module grew from 24 EBEs in 2017 to 181 EBEs by 2019. The network of PAP-Foundation comprises a total of two healthcare institutions, 20 patient organizations, and eight regional institutions with various roles in the field of welfare and care. These organizations make their network available to PAP-Foundation with regard to EBE-recruitment.

Create partnerships with the various educational institutions: the process of advocating inter-institutional IPE involving patients from inception to a final stage, in which all parties involved are unified in terms of content (e.g., examination and included theoretical concepts) and practical arrangements (e.g., costs, place in or in addition to the curriculum, and when and where the education takes place).

Recommendations

Below we describe key recommendations in realizing sustainable EBE participation in IPE activities, based on the example described above.

Recommendations related to experts by experience

Centralize and facilitate EBE recruitment for multiple institutions

In many educational programmes involving patients, individual course organizers are responsible for the recruitment of EBEs, possibly via community organizations. This leads to duplicated efforts, as every course organizer has to reach out to patients or patient organizations. Structured recruitment of EBEs is feasible to establish a pool of motivated, experienced EBEs for all educational institutions in the region (Haeney et al., Citation2007; Spencer et al., Citation2018; Towle & Godolphin, Citation2013). Therefore, PAP-Foundation uses its central network of (patient) organizations and individuals, such as family physicians, nurse practitioners, and medical specialists for the recruitment of EBEs. Patient organizations have an advocacy goal and participating in the curricula of various health professions contribute to this goal. Healthcare organizations see the long-term benefit of training workers who are better equipped to work in the contemporary interprofessional healthcare environment. Hence, centralized networking- and recruitment efforts benefit all the participating educational institutions as opposed to each institution having its separate investments in EBE recruitment. PAP-Foundation facilitates a central website where information, experiences, and a sign-up form can be found.

Carefully inform and instruct EBEs

Once EBEs sign up, they participate in a telephonic intake by an EBE who is an executive board member of PAP-Foundation. Aside from the required personal information, potential EBEs can discuss questions and possible concerns regarding participation with someone who has participated as an EBE before. Briefing of EBEs is judged important before their partaking in education (Baines & Regan de Bere, Citation2018; Hatem et al., Citation2003; Towle & Godolphin, Citation2013). Therefore, prior to their first participation in the module, EBEs are briefed on the content of the education they will partake in, including their roles and responsibilities.Footnote2 Additionally, they are informed about the study backgrounds of the participating students, so they can cater their contributions to students’ frames of reference. However, in this instruction, it was emphasized that EBEs could share any experience with illness and health care that they deemed relevant. This was done to ensure EBEs’ authenticity, which is what distinguishes the PAP-module from other forms of (simulation-based) educational activities (Towle & Godolphin, Citation2013).

Ensure reciprocity to EBEs

To ensure that EBEs feel appreciated and to enhance their well-being, PAP-Foundation organizes events with and for EBEs. Examples include a semiannual get-together for EBEs in which they get insight into their contributions to students’ learning outcomes and have a chance to meet peers, and a two-weekly digital coffee session with EBEs. Additionally, EBEs receive an annual magazine in which their contributions and the development of the foundation are outlined. The primary intention of these activities is to create a sense of community and express gratitude for EBEs’ willingness to spend their time and energy on helping students. Elsewhere, EBEs are awarded for their contributions (University of British Columbia Health Patient & Community Partnership for Education, Citation2021). Literature suggests that not being paid appropriately for the involvement as an EBE is a potential barrier to become engaged in education (Speed et al., Citation2012). To lower this threshold, PAP-Foundation reimburses travel expenses to EBEs on behalf of the participating institutions. Since chronic illness can lead to shrunken social networks, and a lower sense of purpose, PAP-Foundation tries to contribute to EBEs’ well-being and ability to participate in society as opposed to providing financial remuneration (Biordi & Nicholson, Citation2013).

Recommendations related to the inter-institutional organization

Facilitate adequate delivery through central training of facilitators

Professional development for facilitators, to help them cope with the complex role of facilitating IPE involving EBEs, is essential (Reeves et al., Citation2016). In preceding research, facilitators reported that leading the PAP-module was perceived as demanding, and special attention should be paid to students’ vulnerability resulting from personal experience as (a relative of) a patient (Romme et al., Citation2020). To facilitate the adequate delivery of the programmes’ intended learning outcomes, even with large numbers of facilitators from different institutions, teaching staff are informed and trained by PAP-Foundation. Candidate facilitators receive training on how to cater to the different frames of reference of students of various health professions. EBEs and PAP-Foundation staff jointly facilitate these training sessions and EBEs simulate various challenging situations teaching staff might encounter. An example includes EBEs extensively focusing on and speaking to one specific profession (often doctors), thereby making the learning experience less comprehensive and less engaging for students from other disciplines.

Align examination while allowing tailoring

Different study programmes prioritize different competencies and can have different philosophies regarding the assessment of students (Smeets et al., Citation2021). This hinders the implementation of IPE (Lawlis et al., Citation2014). When students’ study programmes and students’ study levels differ, these hindrances expand. Students write a reflective assignment in interprofessional groups, which is evaluated either summatively or formatively, depending on their institution. In addition to this universal assessment, educational institutions can add their preferred form of assessment to ensure alignment with their respective curricula. In the implementation years of the PAP-module, PAP-Foundation offered a platform through which facilitators and examiners from different educational institutions could discuss and align assessment. The frequency in which these meetings took place decreased as the implementation of the PAP-module was finalized.

Empower students and patient leaders

One of the core functions of higher education is to prepare tomorrow’s leaders (Astin & Astin, (Citation2000)). Students who are involved in leadership activities have the potential to increase their skills and knowledge (Skalicky et al., Citation2020). PAP-Foundation’s leadership relies heavily on students and EBEs. They are responsible for the logistic aspects of organizing inter-institutional IPE with EBEs. Through this, student leaders acquire organizational, collaborative, and communicative competencies in a professional context. Patient leaders make their voices heard and practice for possible re-integration in paid labor (Towle et al., Citation2010).

Create a clear division of tasks and responsibilities between institutions and the third-party

Inter-institutional education requires commitment from all participating institutions. Challenges relate to joint scheduling, differing exam regulations, adequate financial investment, commitment by management, and positioning within (or in addition to) existing curricula (Lawlis et al., Citation2014). displays the division of responsibilities between PAP-Foundation and individual educational institutions. On a practical level, PAP-Foundation facilitates the complex scheduling of the module. The PAP-module is executed at different institutions simultaneously. Students from the various educational institutions are distributed over the participating institutions, meaning that some students follow the PAP-module on another institution than their own. PAP-Foundation creates a comprehensive timetable considering individual institutions’ requirements, like the number of participating students and scheduling constraints. Institutions pay a fixed fee per student to PAP-Foundation. This way educational institutions have no financial obligations toward each other. Each hosting institution individually finances costs related to the operational realization (e.g., costs of teaching staff and catering). The linking pin (in our case PAP-Foundation) is not required to be a separate legal entity but can be a task force with delegates of each participating institution as well. Importantly, students, EBEs, and network partners should experience ownership.

Table 2. Task division between a third-party and individual educational institutions based on the example of the PAP-Foundation.

Future directions

Initiated from an educational perspective, our efforts primarily focused on the learning outcomes for students. Throughout the years, we have come to see the benefits of participating in IPE for EBEs, and the proactive role academia can play in so-called university–community partnerships. These have been described as ‘the coming together of diverse interests and people to achieve a common purpose via interactions, information sharing, and coordination activities’(Bell et al., Citation2015). University-community partnerships have proven benefits for all participating parties, being students, EBEs as well as teaching staff. In this section, we formulate how we propose to optimize these benefits based on past experiences with the inter-institutional organization of IPE involving patients.

Optimize contributions to EBEs’ well-being

As described before, we organize semiannual get-togethers and offer a yearly magazine to EBEs. Currently, we are working to extend these activities into events for EBEs focusing on facilitating peer support and contributing to their personal and professional development. Examples include storytelling workshops, overcoming loneliness, and coping with illness. Additional to these incidental workshops, we created a learning continuum for EBEs who want to improve their self-management, called the Patient as a Person Academy. Through 16 weekly meetings, EBEs are supported and challenged to transform their experiences into experiential knowledge and experiential expertise subsequently (Der Schaaf Ps & Oderwald, Citation1999).

As an additional advantage, supporting the development of EBEs could aid their ability to constructively contribute to students’ learning (Armstrong et al., Citation2013; Pomey et al., Citation2015).

Use the created infrastructure to develop a learning continuum

The network of educational institutions and EBEs could be used to integrate an inter-institutional person-centered care learning continuum that students follow with students from other disciplines. Educational institutions can then opt-in or out for various parts of this learning continuum. As the infrastructure of EBEs, institutions, and the third party is already in place, the incremental costs of adding new activities are relatively low and can enhance the learning outcomes for students. Creating a learning continuum has the additional advantage that teaching staff would become more experienced in facilitating inter-institutional interprofessional education, which in turn benefits the quality of education for students (Evans et al., Citation2016, Citation2020). Furthermore, if there are more activities EBEs can choose from, they can participate in those activities that suit their preferences best to add to their well-being.

Create sustainability of the third party

The willingness of educational institutions to commit to the joint organization of IPE involving EBEs largely depends on the perceived additional value for their programmes and the perceived sustainability of the joint organization (Lawlis et al., Citation2014). The linking pin (PAP-Foundation in this case) is at the core of the organization and therefore should be sustainable and able to safeguard continued relevance and appropriate quality. Therefore, representatives of educational institutions could take place in a supervisory board to maintain influence on the direction of the linking pin. By formalizing educational institutions’ voices, educational institutions might have more comfort with and influence on its direction and simultaneously decrease described challenges in university-third party partnerships (Bell et al., Citation2015). More generally stated, any collaboration between educational institutions should carefully consider that all parties experience sufficient ownership.

Conclusion

The establishment of an independent foundation led by students and experts by experience (EBEs) that is responsible for EBE recruitment and development, and fostering inter-institutional collaboration, has enabled three educational institutions in The Netherlands to jointly provide interprofessional education in person-centered care, with active and lasting involvement of EBEs. The establishment of an organization that functions as a linking pin between participating institutions optimizes value for students, facilitators, EBEs, and educational institutions. This organizational model could be used as a starting point for other forms of interprofessional, inter-institutional interprofessional education involving EBEs.

Ethical approval

Netherlands Association for Medical Education (NVMO) Ethical Review Board approved the collection of the data presented in this paper under NERB file number 992. Informed consent was obtained from students prior to filling out the evaluation form.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (34.5 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the contribution made by all the EBEs, students, and facilitators involved in the organization and execution of the PAP-module throughout the years. A special acknowledgment to Marijke van Santen and Jan van Dalen for their guidance and confidence in the first pilots of the Patient As a Person module.

Disclosure statement

Both MB and SR initiated and were board members of Patient as a Person Foundation when the study was conducted. They received no financial remuneration for their contributions.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2022.2093843

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Matthijs Hugo Bosveld

Matthijs H. Bosveld, MSc has a master in Healthcare Policy, Innovation and Management and is currently finishing his master in Medicine. Additionally, Matthijs is a PhD-candidate at Maastricht University, at the Care And Public Health Research Institute (CAPHRI), department of family medicine and the School of Health Professions (SHE). His research focuses on patient participation in education and care. Furthermore, Matthijs co-founded the Patient as a Person Foundation and is appointed as a general board member.

Sjim Romme

Sjim Romme, MSc holds a master in European Health Economics and Management. Additionally, Sjim is a PhD-candidate at Maastricht University at the Care And Public Health Research Institute (CAPHRI), department of family medicine. His research focuses on patient participation in education. Furthermore, Sjim co-founded the Patient as a Person Foundation and is appointed as a general board member.

Jascha de Nooijer

Jascha de Nooijer, PhD, Professor in Interprofessional Teaching and Learning, is Director of Education for Health (Education Office, Faculty of Health, Medicine and Life Sciences (FHML), Maastricht University (since 2016). She has a background in Health Promotion and Health Professions Education. To combine these two fields of expertise, her research focuses on interprofessional education, preferably in relation to the promotion of a healthy lifestyle. She participates in the School of Health Professions Education (SHE).

Hester Wilhelmina Henrica Smeets

Hester Wilhelmina Henrica Smeets, MSc currently works at Zuyd University of Applied Sciences, within the Domain Healthcare & Well-being, as a lecturer in interprofessional education. Next to this, Hester is a PhD-candidate at the School of Health Professions Education, Maastricht University, and the Research Centre for Autonomy and Participation of Persons with a Chronic Illness at Zuyd University of Applied Sciences. Her design-based research focuses on educational assessment of interprofessional competencies.

Jerôme Jean Jacques van Dongen

Jerôme Jean Jacques van Dongen, PhD works as a lecturer and researcher at the Centre of Community Care at Zuyd University of Applied Sciences. Jerôme conducts research on interprofessional collaboration in the community. Per September 1st 2022, Jerôme is appointed as associate professor of applied sciences at Zuyd University of Applied Sciences and MIK & PIW Group.

Marloes Amantia van Bokhoven

Marloes Amantia van Bokhoven, MD PhD, is an associate professor at the department of Family Medicine at the Care And Public Health Research Institute (CAPHRI), Maastricht University. Her research focuses on interprofessional collaboration and education in primary health care. Additionally, she works as a general practitioner in Elsloo, the Netherlands.

Notes

1. Throughout this paper, the term ‘expert by experience’ is used. It encompasses people with health problems or their close relatives. These participants could also be referred to as (expert) patients, service users, clients or consumers. We recognize that no single term is adequate or universally acceptable.

2. During the COVID-19 pandemic, this instruction included a video-conferencing tutorial, as the education could not be provided at the participating educational institutions.

References

- Armstrong, N., Herbert, G., Aveling, E.-L., Dixon-Woods, M., & Martin, G. (2013). Optimizing patient involvement in quality improvement. Health Expectations, 16(3), e36–e47. https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.12039

- Astin, A. W., & Astin, H. S. (2000). Leadership reconsidered: Engaging higher education in social change. Battle Creek. W.K.

- Baines, R. L., & Regan de Bere, S. (2018). Optimizing patient and public involvement (PPI): Identifying its “essential” and “desirable” principles using a systematic review and modified Delphi methodology. Health Expectations, 21(1), 327–335. https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.12618

- Bell, K., Tanner, J., Rutty, J., Astley-Pepper, M., & Hall, R. (2015). Successful partnerships with third sector organisations to enhance the healthcare student experience: A partnership evaluation. Nurse Education Today, 35(3), 530–534. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2014.12.013

- Biordi, D. L., & Nicholson, N. R. (2013). Social isolation. Chronic Illness: Impact and Intervention, 85–115 https://books.google.nl/books?hl=nl&lr=&id=rTVuAAAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PA97&dq=biordi+nicholson+social+isolation&ots=-Rz9_xoBlR&sig=6X9cCC031ENtgfJM5dyZKGDJmCU&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=biordi%20nicholson%20social%20isolation&f=false

- Centre for the Advancement of Interprofessional Education. (2016). CAIPE statement of purpose. https://www.caipe.org/resource/CAIPE-Statement-of-Purpose-2016-1.pdf

- der Schaaf Ps, V., & Oderwald, A. K. (1999). Chronisch zieken over ervaringsdeskundigheid: Een empirisch onderzoek naar de opvattingen over het begrip ervaringsdeskundigheid van chronisch zieken. In: Chronically ill people on experiential expertise: An empirical study about beliefs of chronically ill people concerning the concept of experiential expertise. Vrije Universiteit van Amsterdam, Department of Metamedica.

- Eklund, J. H., Holmström, I. K., Kumlin, T., Kaminsky, E., Skoglund, K., Höglander, J., Meranius, M. S., Condén, E., & Summer Meranius, M. (2019). “Same same or different?” A review of reviews of person-centered and patient-centered care. Patient Education and Counseling, 102(1), 3–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2018.08.029

- Evans, S., Shaw, N., Ward, C., & Hayley, A. (2016). “Refreshed … reinforced … reflective”: A qualitative exploration of interprofessional education facilitators’ own interprofessional learning and collaborative practice. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 30(6), 702–709. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2016.1223025

- Evans, S., Ward, C., Shaw, N., Walker, A., Knight, T., & Sutherland-Smith, W. (2020). Interprofessional education and practice guide No. 10: Developing, supporting and sustaining a team of facilitators in online interprofessional education. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 34(1), 4–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2019.1632817

- Faculty working group Interprofessional Education (2016). Interprofessional competence model and interprofessional building blocks. http://docplayer.nl/storage/41/22387139/1649346543/9ml3BUmc53PfaDJCHvs0Rg/22387139.pdf

- Frenk, J., Chen, L., Bhutta, Z. A., Cohen, J., Crisp, N., Evans, T., Fineberg, H., Garcia, P., Ke, Y., Kelley, P., Kistnasamy, B., Meleis, A., Naylor, D., Pablos-Mendez, A., Reddy, S., Scrimshaw, S., Sepulveda, J., Serwadda, D., & Zurayk, H. (2010). Health professionals for a new century: Transforming education to strengthen health systems in an interdependent world. The Lancet, 376(9756), 1923–1958. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61854-5

- Haeney, O., Moholkar, R., Taylor, N., & Harrison, T. (2007). Service user involvement in psychiatric training: A practical perspective. Psychiatric Bulletin, 31(8), 312–314. https://doi.org/10.1192/pb.bp.106.013714

- Hajat, C., & Stein, E. (2018). The global burden of multiple chronic conditions: A narrative review. Preventive Medicine Reports, 12(1), 284–293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmedr.2018.10.008

- Happell, B., Byrne, L., McAllister, M., Lampshire, D., Roper, C., Gaskin, C. J., Martin, G., Wynaden, D., McKenna, B., Lakeman, R., Platania‐Phung, C., & Hamer, H. (2014). Consumer involvement in the tertiary-level education of mental health professionals: A systematic review. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 23(1), 3–16. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12021

- Hatem, D. S., Gallagher, D., & Frankel, R. (2003). Challenges and opportunities for patients with hiv who educate health professionals. Teaching and Learning in Medicine, 15(2), 98–105. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15328015TLM1502_05

- Hunt, J. B., Bonham, C., & Jones, L. (2011). Understanding the goals of service learning and community-based medical education: A systematic review. Academic Medicine, 86 (2), 246–251. https://journals.lww.com/academicmedicine/Fulltext/2011/02000/Understanding_the_Goals_of_Service_Learning_and.26.aspx.

- Lawlis, T. R., Anson, J., & Greenfield, D. (2014). Barriers and enablers that influence sustainable interprofessional education: A literature review. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 28(4), 305–310. https://doi.org/10.3109/13561820.2014.895977

- McKinlay, E., Brown, M., Wallace, D., Morris, C., Garnett, A., & Gray, B. (2021). A match made in heaven: Exploring views of medicine students, pharmacy interns and facilitators in an interprofessional medicines pilot study. The Internet Journal of Allied Health Sciences and Practice, 19(1), 3. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/46ad/a2f387fd2f855865694e47bedba1feeab10c.pdf

- Orchard, C. A., Curran, V., & Kabene, S. (2005). Creating a culture for interdisciplinary collaborative professional practice. Medical Education Online, 10(1), 4387. https://doi.org/10.3402/meo.v10i.4387

- Pomey, M.-P., Hihat, H., Khalifa, M., Lebel, P., Néron, A., & Dumez, V. (2015). Patient partnership in quality improvement of healthcare services: Patients’ inputs and challenges faced. Patient Experience Journal, 2(1), 29–42. https://doi.org/10.35680/2372-0247.1064

- Reeves, S., Pelone, F., Hendry, J., Lock, N., Marshall, J., Pillay, L., & Wood, R. (2016). Using a meta-ethnographic approach to explore the nature of facilitation and teaching approaches employed in interprofessional education. Medical Teacher, 38(12), 1221–1228. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2016.1210114

- Romme, S., Bosveld, M. H., Van Bokhoven, M. A., De Nooijer, J., Van den Besselaar, H., & Van Dongen, J. J. J. (2020). Patient involvement in interprofessional education: A qualitative study yielding recommendations on incorporating the patient’s perspective. Health Expectations, 23(4), 943–957. https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.13073

- Skalicky, J., Warr Pedersen, K., van der Meer, J., Fuglsang, S., Dawson, P., & Stewart, S. (2020). A framework for developing and supporting student leadership in higher education. Studies in Higher Education, 45(1), 100–116. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2018.1522624

- Smeets, H., Moser, A., Sluijsmans, D., Janssen-Brandt, X., & Van Merrienboer, J. (2021). The design of interprofessional performance assessments in undergraduate healthcare & social work education: A scoping review. Health, Interprofessional Practice and Education, 4(2), 2144. https://doi.org/10.7710/2641-1148.2144

- Speed, S., Griffiths, J., Horne, M., & Keeley, P. (2012). Pitfalls, perils and payments: Service user, carers and teaching staff perceptions of the barriers to involvement in nursing education. Nurse Education Today, 32(7), 829–834. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2012.04.013

- Spencer, J., McKimm, J., & Symons, J. (2018). Patient involvement in medical education. Understanding Medical Education, 207–221. https://shmu.ac.ir/file/download/page/1640671652-understanding-medical-education.pdf#page=227

- Teodorczuk, A., Khoo, T. K., Morrissey, S., & Rogers, G. (2016). Developing interprofessional education: Putting theory into practice. The Clinical Teacher, 13(1), 7–12. https://doi.org/10.1111/tct.12508

- Towle, A., Bainbridge, L., Godolphin, W., Katz, A., Kline, C., Lown, B., Madularu, I., Solomon, P., & Thistlethwaite, J. (2010). Active patient involvement in the education of health professionals. Medical Education, 44(1), 64–74. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03530.x

- Towle, A., & Godolphin, W. (2013). Patients as educators: Interprofessional learning for patient-centred care. Medical Teacher, 35(3), 219–225. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2012.737966

- University of British Columbia Health Patient & Community Partnership for Education. (2021). Awards/Scholarships: Recognizing patient and community expertise. https://health.ubc.ca/pcpe/awardsscholarships

Appendix I

– Student evaluation of the PAP-module

At the end of each PAP-module, students were asked to fill out a quantitative evaluation. In the curriculum years 2018–2019 and 2019–2020 this questionnaire was completed by 646 students. The questionnaire was offered to 1016 students, so 64% responded. The data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 26.0. Students reported positive outcomes of learning how to adopt a person-centered approach to patients and collaborating interprofessionally. Students found visiting the EBEs in their personal environment the most instructive part of the module (4.3 out of 5). The added value of the PAP-module in terms of learning about other professions was considered lower (3.5 out of 5) compared to developing insight into the impact of illness on EBEs’ lives ().