ABSTRACT

The United States (US) National Center for Interprofessional Practice and Education was funded at the University of Minnesota to serve as the National Coordinating Center for Interprofessional Education and Collaborative Practice (IPECP) in the US In 2012, the funders had specific expectations for operationalizing their vision that included scholarship, programs and leadership as an unbiased, neutral convener to align education with health system redesign. While US specific, the National Center benefited from and contributed to the international maturity of the field over the past decade. Through its various services and technology platforms, the National Center has a wide reach nationally and internationally. This perspective provides a unique view of the field in the US with observations and implications for the future.

Introduction

In 2012, the United States (US) Department of Health and Human Services Health Resources and Services Administration (DHHS-HRSA) selected the University of Minnesota (UMN) to create the National Center for Interprofessional Practice and Education (National Center) to “advance a national healthcare workforce trained to work in patient-centered, team-based settings” (Chen et al., Citation2013, p. 357; HRSA, Citation2012). DHHS-HRSA and other fundersFootnote1 expect the National Coordinating Center to serve as a respected resource for unbiased, expert guidance on issues related to interprofessional education and collaborative practice (IPECP) for the US (US Department of Health and Human Services, Citation2012). DHHS-HRSA charged the National Center staff to provide an infrastructure for national interprofessional research and evaluation activities, including data analysis and dissemination (Chen et al., Citation2013).

In the proposal to DHHS-HRSA, based upon experience, the UMN senior leaders described a growing disconnect between health professions education and the rapidly transforming US health system to prepare a workforce capable of achieving Triple Aim outcomes (improve patient experience of care, improve health of populations, and reduce per capita cost of health care) (Berwick et al., Citation2008). To address the gap, a compelling vision, called the Nexus, was proposed. This innovative framing for tackling these complex issues focuses on redesigning health professions education and healthcare practice as a united system that is more interprofessional and demonstrates patient, organisational and learning outcomes (Earnest & Brandt, Citation2013, Citation2014).

In this article, we discuss the operationalization of the National Center, including the funders’ expectations; the evolution of the signature Nexus vision that guides our scholarship and programs. This background informs the center’s current four strategic areas; the lessons learned and programming for the future.

Operationalizing the national center

The funders who conceptualized the National Coordinating Center and set its parameters were actively involved in operationalizing the National Center infrastructure. Because of the diversity of expectations, the National Center staff developed a charter document with the funders about how they would work together for aligning funding agencies’ interests, including the UMN, with the center’s goals and strategies. Over five years, these funding agencies served as the primary sounding board and problem-solving group on matters of strategy and content, reviewed high-level work plans, served as an ambassador resource to help connect the center to others in the field, and advised on aligning funding requirements.

They were also instrumental in naming the center from IPECP to the term “interprofessional practice and education,” extending the IPE acronym beyond interprofessional education. To signal that the Nexus vision is different from past US interprofessional education efforts over 50 years, IPE, with the new term, contrasts with the traditional use of IPE for interprofessional education, often interpreted by many as only pre-licensure, preparatory classroom curricula in universities and colleges. The new usage is intended to reinforce that learning and practice are inextricably linked. The shift in thinking moves the emphasis to practice and community settings to align interprofessional education with health systems redesign, focused on Triple Aim (now Quadruple Aim with the fourth aim as the health and wellbeing of clinicians) outcomes (Bodenheimer & Sinsky, Citation2014; Delaney et al., Citation2020). Today, many US universities and colleges have adopted the new IPE term and acronym in naming their interprofessional centers.

Evolution of the Nexus vision

The Nexus vision moves from primarily preparing students to be collaboration-ready to a partnership of the education and health systems to impact people in real-time (Earnest & Brandt, Citation2013, Citation2014). The Nexus is designed intentionally to link the health professions education and healthcare systems for interprofessional workforce development of future and current health professionals and to simultaneously demonstrate learning and health outcomes. In 2013, Earnest and Brandt called the Nexus, “The triple aim for alignment” and set as its goals:

Reducing costs and adding value for the alignment of the education system with the health system,

Reframing quality for the patient and learner experience by creating an integrated practice and education system to incorporate key stakeholders,

Accepting shared responsibility for population health and learning for the end goal of people- and community-centered health outcomes in a transformed system (Earnest & Brandt, Citation2013, p. 45).

The term, interprofessional practice and education, and the concept of the Nexus resonated with stakeholders. Many were skeptical about past interprofessional work after experiencing resurgence and refocusing of various initiatives with little traction or few demonstrable outcomes over decades (Baldwin, Citation1996, Citation2013; Hall & Weaver, Citation2001). Several, including some funders who had invested in interprofessional programs, found the term pejorative. As a starting point to reinforce the National Center’s work about outcomes, we use the 2010 World Health Organization (WHO) definition of interprofessional education adapted to: “two or more professions learn about, from, and with each other to enable effective collaboration and improve health outcomes” (WHO, Citation2010, p. 13). Particularly for those outside of the academic field, this definition is concise, effective, and opens up discussions about interprofessional collaboration for what matters for people who are served. Other definitions, terms and concepts readily follow in practical, situation-specific discussions when building relationships for IPE implementation.

A variety of national councils and committees have and continue to advise the National Center, ranging from a national advisory committee, process coaches, an interprofessional informatics expert committee, the Nexus Learning System advisory committee, and specific task forces on emerging issues. One task force defined the DHHS-HRSA-required operating principles of the national unbiased, neutral convener role as:

identifies “thorny” IPE issues for national discussion and recommendations;

works interprofessionally and intra-professionally to promote dialogue and understanding;

cannot favor one profession or model over another as “best” practice;

advances thinking about IPE based upon evidence, experience and expertise; and

advocates for IPE values, based upon what is learned to make a difference.

For example, during several convenings in 2017 and 2018 health professions education faculty identified the issue of competing uni-professional pre-licensure accreditation requirements as detrimental to implementation. As a result, in 2017 the National Center presented a case study to illustrate the problems to the Health Professions Accreditors Collaborative (HPAC), representing 25 health professions accreditors of schools. From 2017 to 2019, the accreditors and the National Center met to gain consensus on principles, an outline and finally guidance for developing quality interprofessional education (Health Professions Accreditors Collaborative, Citation2019).

The American Interprofessional Health Collaborative (AIHC), established in 2009 at the University of Minnesota following the inaugural 2007 Collaborating Across Borders conference in Minneapolis, is an increasingly important collaborator to advance the national IPE movement with the National Center (Blue et al., Citation2010). A membership organization since 2017, AIHC is the National Center professional community steadily growing with nearly 500 individuals engaged. AIHC members are actively contributing to the interprofessional movement through committees, special workgroups, and scholarly contributions. The membership interfaces with important national and international interprofessional organizations such as Interprofessional. Global, Interprofessional Education Collaborative (IPEC), the National Academies of Practice, and individual health profession organizations.

Four strategic areas of the National Center

Because of the high visibility of the peer-reviewed grant selection process and historic multi-million-dollar investment in not only IPECP but also in health professions education in general, the UMN staff experienced a “tsunami” of requests from the first day. In the first year, hundreds of people from US higher education and healthcare systems made requests ranging from information, training, help with specific IPE implementation, inquiries for speakers, and availability of grant funding. The volume of requests from individuals and organizations globally has grown substantially over the years, allowing a “birds-eye” view of the field nationally and internationally. With the help of consultants, the National Center learned to manage and organize its work through a variety of platforms to meet the large number of stakeholder requests. This portfolio defines our current four strategic areas, described below: Nexusipe.org and the Resource Center, knowledge generation, education and training, and thought leadership.

Nexusipe org and the resource center

The 2010 US Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA) and the release of the 2011 Interprofessional Education Collaborative (IPEC) competencies stimulated the renewed interest in the 50-year-old interprofessional education field (IPEC, Citation2011; PPACA, Citation2010). In 2013, the Center staff developed a technology solution with a global reach to meet the pent-up demand for information and requests. On July 1, 2013, information technologists launched a unique platform, the Nexusipe.org and the Resource Center, a combination of community-generated and National Center-specific resources with dynamic algorithms to connect assets. Individuals or organizations create profiles and can upload their resources to share. The National Center posts announcements, reports, resources and publications on this platform, and works with partners on curated collections, described below. The platform tracks metrics and views, and contributors regularly use the IPE-specific data for promotion and tenure and other performance review purposes, similar to other systems such as Alimetric.

Since its launch, more than 580,000 new users have accessed the Nexusipe.org website. In 2022, people from 186 countries viewed Nexusipe.org compared to 126 countries in 2013. Of the total users, in 2022 37.5% were from outside the United States, primarily China, Canada, United Kingdom, India, Philippines and Germany. When someone conducts a general Internet search, the following terms populate links to Nexusipe.org with the first 1–2 search results: IPE evaluation, IPE assessment, specific interprofessional assessment tools, Collaborating Across Borders Conference, and What is T3 Training?

In 2023, the Professional Directory on Nexusipe.org is home to more than 8,000 individual and organization user profiles of those involved in IPE throughout the world. Having a profile has two functions: users contribute their own work and can access specific password-protected resources. The Resource Center currently contains more than 2,600 community-generated and National Center entries, ranging from historical documents, peer-reviewed publications, educational modules, case studies, presentations, organizational reports, and other gray literature. The platform additionally allows users to form private group discussions; a user group of more than 200 DHHS-HRSA grantees has used the platform to discuss behavioral-primary care integration since 2017. The only contribution-restricted section of Nexusipe.org is the expert peer-reviewed Measurement Collection. In the first year of operation, the number one request to the National Center was for vetted measurement tools for interprofessional education and guidance on how to use them. In 2013, using the Canadian Interprofessional Health Collaborative (CIHC) measurement tool list as a start point, the National Center evaluators identified 26 IPE measurement tools. As the staff gained experience with the nature of requests about measurement and the individual tools, two psychometric experts authored the National Center paper, Evaluating Interprofessional Education and Collaborative Practice: What should I consider when selecting a measurement tool? (Cullen & Schmitz, Citation2015). As of 2023, there have been over 3,500 unique pageviews of the document.

To further meet the demand for increased guidance regarding measurement, on 30 January 2017, the National Center relaunched its measurement and assessment collection on Nexusipe.org. Acknowledging the positive or negative influence the Center can have, two measurement experts created a standardized framework to evaluate tools, independently reviewed tools, identified and agreed upon 48 tools for inclusion, and wrote profiles for each (B. F. Brandt & Schmitz, Citation2017). The new collection features a searchable function of the identified tools with descriptive profiles. As of 2023, the Measurement Collection is the most visited section of Nexusipe.org with more than 474,000 unique pageviews by users from 190 countries.

Partners have worked with the National Center to curate specific IPE-related collections: Age-Friendly Care and Education Collection and Australian and New Zealand Regional Collection. Additionally, the National Center has made the commitment to protect historical documents of the IPE field, starting with securing the papers of Dr. DeWitt (Bud) Baldwin Jr, IPE pioneer (M. H. Schmitt, Citation2007). Through algorithms, these resources are connected to others on Nexusipe.org to support scholarship and IPE implementation.

Knowledge generation

To address the key requirement to promote “scholarship, evidence, coordination, and national visibility,” DHHS-HRSA emphasized healthcare practice, including creating a national data infrastructure and data analysis. Because the UMN senior leaders linked IPE to the Triple Aim in the proposal, a baseline scoping review was conducted to understand the existing evidence (B. Brandt et al., Citation2014). Despite decades of scholarship by multiple disciplines, the 2014 National Center scoping review revealed that IPECP inquiry:

… remains focused on examining three levels of impact – individual level in terms of immediate or short-term changes that ICP/IPE has on knowledge, skills and attitudes; practice level in terms of practice-based processes – but not outcomes; and organizational level in terms of intermediate policy changes. (B. Brandt et al., Citation2014, p. 396).

Based upon these findings, the National Center staff have published extensively on the evolving approach to collecting data for contributing to the knowledge and evidence connecting IPE to learning, organisational and health outcomes (Delaney et al., Citation2020). The research approach, as identified in the DHHS-HRSA proposal, began with the original Nexus Innovations Incubator (See ) comprised of eight institutions that were implementing large-scale, system-wide IPE efforts at the time (Pechacek et al., Citation2015). From 2013 to 2017, the number of sites grew and became the Nexus Innovation Network, with 70 sites and over 100 projects submitting data to the original National Center Data Repository, the precursor to the National Center Interprofessional Information Exchange (NCIIE) (Delaney et al., Citation2020). The intensive experience with data, IPE implementation, meetings, and advisory committees created an iterative process with partners which in and of itself has been a knowledge generation approach. The National Center researchers were able to select practical instruments and create tools to be used in practice based upon continuous learning of what aligns education with US fee-for-service payment health systems models (Delaney et al., Citation2020).

The NCIIE is a scalable platform that allows real-time access to actionable data reports that support iterative practice and education improvements and longitudinal assessment of program impact on outcomes that matter. The NexusIPE™ Core Data Set has been developed to capture learner and system outcomes including attainment of interprofessional competencies and Quadruple Aim health outcomes (Delaney et al., Citation2020). Importantly, the NCIIE and NexusIPE™ Core Data Set includes two validated instruments: 1. teamness using the Assessing Collaborative Environments-15 (ACE-15) instrument and 2. interprofessional learning, the Interprofessional Collaborative Competency Attainment Survey (ICCAS) (Archibald et al., Citation2014; Tilden et al., Citation2016). An interdisciplinary research team created approaches to collect data on patient and healthcare team member satisfaction and meaningful health and system outcomes identified during the proposal process (Delaney et al., Citation2020).

The National Center Knowledge Generation approach, using the NCIIE and carefully curated essential core data elements, the NexusIPE™ Footnote2 Core Data Set, is currently in use in two DHHS-HRSA-funded projects in primary care networks: the UMN Minnesota Northstar Geriatric Workforce Enhancement Program (GWEP) and the Thomas Jefferson University JeffBeWell Primary Care Training Enhancement grant. The Northstar GWEP, also funded by the Otto Bremer Trust Foundation and the UMN, is using these tools to support development and dissemination of a new health and learning model to scale and create age-friendly practices in UMN's network of family medicine clinics. An interprofessional team is developing a clinical practice workflow to systematically collect data to be able to act in real-time on the 4 M’s of geriatric care (Medications, Mentation, Mobility and What Matters) (Institute for Healthcare Improvement [IHI], Citation2020). Similarly, the Thomas Jefferson University Department of Family and Community Medicine is studying the adoption and impact of the Integrated Behavioral Health model, first at the Jefferson Family Medicine Associates and ultimately across the Jefferson Primary Care Network. In each DHHS-HRSA-funded program, all stakeholders, including identified interprofessional learners (i.e., health professions students and family medicine residents) as well as the entire primary care clinical practice team complete instruments appropriate for their own practice. After identifying intended organizational and health/patient outcomes, electronic health record data can be entered into the NCIIE.

Education and training

The strong growth of the National Center Education and training participation since 2012 mirrors the national and international growth of the field of IPE. Beginning in March 2013, the Nexus Innovation Network annual meetings presented opportunities to share lessons learned across IPE programs while supporting and cultivating the growing numbers of collaborators and membership. In 2016, the Nexus Learning System Advisory Committee recommended that the National Center staff build upon the Network meetings by expanding to a growing national audience, focusing on advancing the national dialogue and developing practical skills to support program implementation and sustainability.

In 2016, the National Center staff launched the Nexus Summit as an action-oriented conference for those committed to working across practice and education to improve outcomes. Over the next five years, new Summit formats were introduced, such as lightning talks, conversation cafes that introduce “thorny” IPE issues for discussion and possible action, a Nexus Fair with exhibits by organizations implementing IPE, and posters. In 2020, in response to COVID-19, the National Center staff built the “More than a Meeting™” virtual platform by leveraging the Nexusipe.org platform and other technologies for a comprehensive experience, including prerecorded videos and content as well as live, interactive sessions. Post-meeting archival services with fully searchable features allow learning to extend beyond the live meeting. In addition, the inclusion of track leaders, or IPE experts, who facilitate discussions in the lightning talk sessions greatly enhanced the Summit. The track leaders worked with the National Center to create guides to deepen learning and application of the focused track content.

The Summit has also grown significantly. In the inaugural 2016 Nexus Summit, 28 abstracts were submitted for peer-review; the meeting agenda was designed with 67 plenaries, workshops, and invitational sessions. That year, 317 people registered for the Summit, with no student attendees. In 2021, 269 abstracts (861% increase from 2016) were received; and the schedule included 308 peer-reviewed and invitational plenaries, workshops, lightning talks, and posters (362% increase from 2016). In 2021, 675 people registered for the meeting (112% increase from 2016). With AIHC member encouragement, 147 students registered and actively participated as session and poster presenters.

To fulfill the funders’ expectations for outreach, an effective National Center Education and training strategy to reach a large audience has been no-cost webinars. All webinars are recorded and archived as a longitudinal learning resource in the National Center Resource Exchange. Since 2013, the National Center and the American Interprofessional Health Collaborative have sponsored 125 webinars, serving more than 6,000 attendees during live sessions. The National Center is also featured in webinars hosted by other organizations, including OptumHealth, DHHS-HRSA, the Pan American Health Organization, and IPEC. Among the most popular archived webinars are those featuring sustainability planning, measurement and assessment and social determinants of health.

In addition, the National Center as a Jointly Accredited Provider™ for Interprofessional Continuing Education has extended its education and training partnerships with numerous organizations and is a collaborator with organizations such as the Josiah Macy Jr. Foundation-funded Train-the-Trainer (T3) Faculty Development Program created by the University of Washington, University of Virginia at Charlottesville, University of Missouri and University of Texas at Austin; the Nexus Innovation Challenge in partnership with the National Collaborative for Improving the Clinical Learning Environment and SmithGroup, and Collaborating Across Borders with AIHC and the Canadian Interprofessional Health Collaborative (CIHC). During the period 2016–2021, T3 trained 107 teams including 488 people representing more than 20 different professions (Summerside et al., Citation2018; Willgerodt et al., Citation2019).

In 2021, the National Center entered a strategic partnership with the UMN College of Pharmacy and School of Nursing to form the Office of Interprofessional Continuing Professional Development to expand programming for the healthcare team. The office accredits interprofessional programs for medicine, nursing, pharmacy, social work, and other professions. As of November 2021, the National Center has provided people with accredited content more than 8,100 times over the course of more than 670 activities. In December 2021, the Joint Accreditation™ for Interprofessional Continuing Education awarded commendation to the National Center for engaging patients and students as planners and teachers, optimizing communication skills and for individualized learning plans.

Thought leadership

Communication and business consultants who reviewed documents and services of the National Center noted that the National Center staff and affiliated colleagues serve as thought leaders: experts in the field with significant intellectual influence and innovative, pioneering thinking, represented by the Nexus vision (Erickson & Chervany, Citation2018). The large number of requests and interactions from multiple sectors since 2012 documents that the National Center staff serve as important thought leaders in the field through serving as keynote speakers at national and international conferences, professional meetings, and significant regional events on a wide range of Nexus topics in support of advancing interprofessional practice and education.

Since 2014, the National Center staff have presented and consulted with more than 200 organizations, conducted nearly 50 site visits, and served on boards, advisory and expert panels such as the American Medical Association Accelerating Change in Medical Education; the National Academy of Science, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) Global Forum on Innovation in Health Professional Education; National Collaborative for Improving the Clinical Learning Environment (NCICLE); and Josiah Macy Jr. Foundation. In addition, the National Center staff have been hired as consultants by higher education institutions, health systems, and associations, such as the American College of Physicians, and the National Center for Complex Care and Social Needs. Finally, the National Center staff have published peer-reviewed papers, commissioned papers, national reports, book chapters about the Nexus and IPE located on Nexusipe.org (https://nexusipe.org/advancing/national-center-publications).

These opportunities to engage “on the ground” with thought leaders and those working to transform interprofessional practice and education provide rich opportunities for the National Center staff to identify current opportunities, challenges, and educational needs for advancing IPE. Further informed by historic and current literature, national advisors, and leaders of AIHC, the National Center is able to tailor educational offerings to address pressing issues in IPE, such as demonstrating outcomes that matter to educators and learners as well as health systems and patients; the need to make new interprofessional educators aware of the history of the field; opportunities for IPE to impact contemporary workforce challenges; and the need to better integrate the social sciences into IPE programming and research. This content is delivered through the annual Nexus Summit, in webinars and local consultations, and through the work of National Center and AIHC committees and workgroups.

2023 Emerging themes with implications for the future

By virtue of the breadth of interactions, program development and experience, the National Center staff have gained a unique national perspective about the field of IPE and implications for its future in the US Based upon this experience, in 2023 below are what we consider four major observations and emerging themes with implications for the future of IPE.

Strong Growth in Numbers since 2011. As demonstrated by the increasing interest in the work of the National Center and other national and international initiatives, IPE and commitment to interprofessional careers have grown significantly in the last decade. In the past decade, many national and local developments are positive signs and symptoms of a growth trajectory, e.g., increasing membership of the IPEC and NCICLE as well as the strengthening of the National Academies of Practice and Joint Accreditation™ for Interprofessional Continuing Education. In addition to the Journal of Interprofessional Care, publication outlets are expanding in disciplinary and interprofessional journals, such as the Journal of Interprofessional Education and Practice based in the U.S. and the Journal of Research in Interprofessional Practice and Education based in Canada. National policy recommendations for team metrics and payment models are routinely made by such groups as the National Quality Forum and the National Academy of Science, Engineering and Medicine (HPAC, Citation2019; National Academies of Sciences, Citation2021). Anecdotally, by the number and nature of presentations at the Nexus Summits, some academic health centers are changing the use of language and perhaps culture to infuse interprofessional principles throughout their institutions.

IPE champions have much to celebrate and at the same time need to be vigilant for the predictable patterns of ebbs and flows of interest and resource investments in IPE, as described below (B. F. Brandt et al., Citation2023; B. F. Brandt, Citation2022; Shrader et al., Citation2022). For example, particularly important is the role of senior leaders in the education and health systems who “set the tone at the top” to signal culture change and provide the requisite resources to integrate the IPE vision into institutional commitment over time (Cerra & Brandt, Citation2015; Cerra et al., Citation2015; Reeves et al., Citation2016). Transitions and frequent flux of one senior leader to another is a vulnerable time for a variety of reasons: competing agendas and resources, questioning impact, lack of understanding about what the goals of the IPE are, and a “checklist” mentality to meeting accreditation standards rather than a deep commitment to transformational culture (B. F. Brandt et al., Citation2023). IPE champions need to be at the senior leadership table to assure sustained and substantive change.

Successful IPE champions need to create and communicate meaningful local evidence of the impact of IPE on both learning and health outcomes that matter to their constituents so it increasingly becomes difficult to view IPE as an “expensive extra.” The implication is that for champions who are advocating for IPE at their own institution, in their individual professions, and nationally need to simplify their message by being practical, not theoretical, with explicit pragmatic examples of evidence of what problems have and can be solved or how opportunities can be seized. A starting point is to use the adapted WHO definition for the work rather than use complex details and obtuse, academic language to educate senior leaders and inspire those needed to be involved in IPE implementation. At the same time, it is critical that research into effective, impactful IPE to achieve outcomes that matter to those served be accelerated to sustain and grow this important work. IPE’s renaissance during this precious period of time provides opportunities to systematically study it in new ways.

The need to broaden perspectives about IPE. In the US, the field of IPECP has a history characterized by bursts, booms, and busts since the 1960s (Baldwin, Citation1996; M. Schmitt, Citation1994). Even at its low ebb, embers of interest have kept it alive, waiting for new external drivers to spark interest in teams and interprofessional collaboration and move the field forward again. Each successive resurgence has helped as well as hindered the advancement of the field. By not consistently building the field over the decades, there have been large gaps in commitment over time and handing down what has already been learned. Since 2011, in the US, the majority of people in the field have entered during the era of patient safety, medical errors, quality improvement, the IPEC competencies, and team training. The current generation is often unaware of the early documented health teamwork in communities dating to the 1910s in the US and the variety of practice-based IPE and interprofessional community-based education in North America in the 1960s and 1970s (Hendrick, Citation1914; IOM, Citation1972; McCreary, Citation1964, Citation1968). With the COVID-19 pandemic, the lessons from earlier efforts are more relevant than ever to address societal issues such as health inequity and the social determinants of health (Barton et al., Citation2020).

Furthermore, beyond temporal issues, we observe that most in the US are unfamiliar with the preceding deep IPE social science scholarship and research of international colleagues, notably the Center for the Advancement of Interprofessional Education (CAIPE) in the United Kingdom paralleling decades of work and leadership nurturing the Journal of Interprofessional Care (Barr et al., Citation2005). The US National Center senior leaders participated in global conversations before 2012 and continue to be informed by and benefit from this rich tradition and global growth trajectory. Although established specifically to support IPE in the US, the National Center has benefited from being part of the robust growing international community (Barr, Citation2015).

As a result of the ebbs, flows, and gaps of lost history, IPE as a field of study has not been codified nor are there many US academic programs specifically dedicated to advancing its scholarship and science. What are the knowledge, skills and attitudes that should be expected to be an effective IPE educator? Today, often unaware of the historical background or decades of research on interprofessional work, the majority of IPE scholarship by necessity is being interpreted through the lens of other academic disciplines or faculty in such fields as higher education administration, communication, health services research, and medical school clinical departments.

Why does this lack of knowledge about the field’s history or global contributions matter? Today, the multiple generations and their views of IPE are working together in their organizations. With each wave of renewed interest in IPE, many start anew and do not benefit from the past research, scholarship, philosophy and vision as well as the lessons that were learned by those who preceded them. Much of the early work is in gray literature and unpublished because of a long history of disciplinary journals not accepting interprofessional papers. Second, we observe institutional memory lapses in higher education institutions with once vibrant IPE programs in the past that were closed or significantly downsized. Several were a part of the Nexus Innovation Network or earlier work showcased by the Association of Academic Health Centers (AAHC, Citation1999). Many have started and struggled with new IPE initiatives and are unaware of these past efforts and the seasoned IPE champions at their own institution.

Nationally and locally, each iteration is built upon confusion about the concept and goals of IPE. Similar to the parable of the blind man and the elephant, people are influenced by their immediate environments and national trends at a certain point in time. The lack of consensus about the field at a high level hinders the ability to communicate and advocate to people in many sectors who need to be influenced. The field is left to the interpretation and assumptions by scholars who have little understanding of or practical experience in it. We have observed the negative impact of influential, isolated papers being used as “evidence” on senior leaders to withdraw support of current IPE programs.

The National Center staff has launched an IPE Ideas Project centered around the Baldwin Collection to protect the lessons learned prior to the extraordinary advances of the past decade. A perusal of the Baldwin curation of documents in the Resource Center demonstrates the history of IPE in the US and beyond, and informs us that we have been here before: training programs for interprofessional teamwork in the 1970s; incorporating paraprofessionals on healthcare teams; 23-years of IPECP research conferences including 500 scholarly papers, many of which had difficulty finding disciplinary publication outlets; and fully implemented IPE programs that were closed in a matter of months (Baldwin, Citation1996, Citation2013; M. Schmitt, Citation1994). The many lessons learned will inform IPE champions about enabling and interfering influences, what to avoid and what to strengthen, as well as important knowledge and theoretical models.

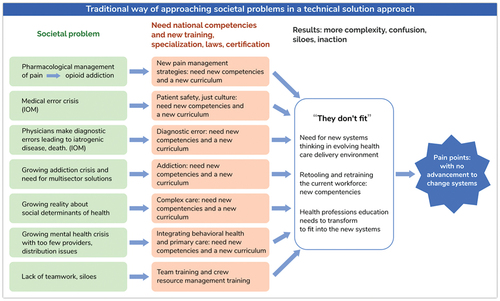

Don’t let education get in the way of learningFootnote3. Scientifically based professions naturally seek technical, evidence-based solutions to problems, particularly when they are complex. Because of the “birds-eye” view across professions, higher education institutions, and healthcare organizations, the National Center staff have observed a proliferation of competencies in a variety of individual areas, new curricula, accreditation requirements, legislations, certifications, and regulations, all with an underpinning of interprofessional teamwork. National competencies are important high-level guideposts to provide the direction for uni-professional and interprofessional work; however, new layers of details are adding another layer of confusion about IPE. It is impossible for professional schools and continuing professional development to address the myriad of detailed requirements. The question is: are these isolated technical solutions leading to the impact we intend for today’s societal problems? ()

The increasing requirements of individual, detailed competency domains within a single profession as well as areas such as diagnostic errors, addiction care, chronic disease management, behavior health integration, and HIV-AIDS are importantly inter-related in the real world. When these competency domains are defined, validated and certified in isolation from each other they communicate artificial siloes and barriers to contributing what matters most to the people who are served and addressing societal problems. How can individual competency domains be reframed using an interprofessional framework rather than building artificial siloes?

For example, to mirror real-life, how can mastering these competencies in specific practice contexts be facilitated at the same time? Given the situation, this reframing would incorporate the vital intertwined imperatives in all clinical and practice settings, such as patient safety, accurate diagnosis, appropriate therapies engaging the right professional and others at the right time, patient engagement, complex care, and the social determinants of health as they are relevant to a specific situation (B. F. Brandt et al., Citation2023). The IPEC competency high-level domains are powerful as contextualized tools at a specific time addressing what people want and need within the context of specific populations and communities, such as addiction, developmental disabilities, rehabilitation, geriatrics, pediatrics, primary care, surgical care, etc.

One approach to answering the question is to expand scholarship in IPE beyond the currently used training and behavioral models to incorporate the rich array of learning theories and science that are scantily cited in the IPE literature. These learning theory approaches need to include cognitive and constructivist models that emphasize learning in natural environments and practice settings (Hean et al., Citation2009, Citation2012; Nisbet et al., Citation2013). Examples of educational approaches that beg to be translated into IPE include informal learning, workplace learning, situated cognition, transformative learning, cognitive apprenticeships, and interprofessional entrustable professional activities. (B. L. Brandt et al., Citation1993; Dochy et al., Citation2022; Meizrow, Citation2000; ten Cate & Pool, Citation2020).

Reconsidering longitudinal IPE curriculum design. The National Center staff have experience in mentoring IPE champions and collecting data during active implementation in community-based and clinical practice settings (B. F. Brandt et al., Citation2023; Delaney et al., Citation2020). We, like others, observe that most US IPE is offered prior to experiential rotations for pre-professional students and is poorly integrated into health professions curricula (B. F. Brandt, Citation2022; O’leary et al., Citation2021; Shrader et al., Citation2022). Furthermore, the greatest opportunity for mastery of collaborative practice is when students/trainees are working together in clinical practice, where relationships are formed and interdependence is readily evident (Zierler et al., Citation2016). O’Leary et al. point out that practice-based IPE should be “normalized” as a key feature in preparing a “collaboration-ready” workforce (2021). IPE that impacts learning, organizational, and health outcomes is possible if emphasis is placed on designing programs for outcomes that matters most to people (individuals,Footnote4 families, communities and populations) we serve first, and then students and professionals in practice settings (B. F. Brandt et al., Citation2023; Fraher & Brandt, Citation2019).

The field can celebrate the unprecedented growth and now has sufficient experience to turn to more sophisticated IPE curriculum design discussions. Because of vast experience, today’s seasoned IPE champions can shift to new conversations about how historical lessons learned and knowledge gained in the past decade, particularly during COVID-19, can inform more sophisticated IPE designs for impact. Yet, much IPE curricular implementation is still the result of a blunt instrument: based upon workarounds, convenience, and politics rather than intentional design that starts with the ends in mind and considers the best learning strategies at developmental stages and milestones across the career continuum (HPAC, Citation2019). In higher education, we observe that more often than not curricular implementation runs out of steam before meaningfully connecting with healthcare and community practice.

Sustainability

Many US IPE programs were initiated with grant funding or one-time investments with expectations that they will be sustained and grown through grants. Often these programs are structured to meet funders’ requirements, and it is unclear what the long-term impact is of reliance on external funding to initiate an IPE program. Similarly, a collaboration between DHHS-HRSA and foundation funders initially provided funding to create the National Center. The funders were actively involved in shaping the Center and expected the National Center staff to develop plans to sustain and grow not only the Center but also the interprofessional movement beyond their investment. They no longer fund the Center and have changed their funding focus under new leadership. Today, a balanced portfolio of resourcing includes UMN support, grants, consultative services, interprofessional continuing professional development activities, program evaluation, and signature programming such as the annual Nexus Summit. Organizations outside the interprofessional community are paying for services, such as the More-Than-A-Meeting™ platform. This business model to date allows us to continue to provide open resources and other platforms to support the IPE field.

Throughout this article and Journal issue, we write about the bursts, booms and busts of the interprofessional movement that can be attributed to a number of factors. While celebrating growth, we know IPE programs can vanish overnight because of a variety of realities that we have already described. Sustainability is an interconnected international, national and local issue. To that end, a defining principle for the Nexus over the next decade is a focus on assuring IPE is a thriving movement for the next generations and beyond. We will be taking the road less traveled by asking uncomfortable questions (B. F. Brandt, Citation2023).

Concluding remarks

Established with a clear mission to support IPE in the US, the National Center has never-the-less had growing engagement with the international IPE community, as witnessed by international interest in the Resource Center and other programming and formal engagement, through AIHC, with colleagues in Interprofessional.Global.

Because of the foresight and high engagement by the original funders, in its tenth year, the National Center has launched a new forward-looking strategic plan and expanded portfolio of services along with a strengthened commitment to the Nexus with the addition of Christine Arenson as the new Center director joining founding director, Barbara Brandt.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the past and present National Center staff members, our advisors, partners, contributors and members of the American Interprofessional Health Collaborative (AIHC) for their commitment to advancement of interprofessional practice and education. We would like to thank our funders and the University of Minnesota for their support and commitment to the National Center as a valued resource. We would also like to thank the Nexus Innovation Network members, advisors and program participants from whom we learn every day. We also acknowledge Savannah Salato for her technical support on this manuscript. Finally, we thank Madeline Schmitt, PhD, RN, FAAN, FNAP for serving as mentor and expert editor in the development of this paper, always pushing for new thinking.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Barbara F. Brandt

Barbara F. Brandt is the founding director of the National Center for Interprofessional Practice and Education and served as the Associate Vice President for Education at the University of Minnesota Academic Health Center, overseeing the implementation of interprofessional practice and education programs from 2000 to 2017. She has served on the strategic advisory board of the Journal of Interprofessional Care and on the editorial board of the Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions.

Jennifer Stumpf Kertz

Jennifer Stumpf Kertz serves as the deputy director of the National Center for Interprofessional Practice and Education, providing guidance and oversight for administrative, fiscal, policy and operations functions. She has served in various interprofessional academic administration roles since 2002, including the creation of an interprofessional academic infrastructure linked to practice.

Christine Arenson

Christine Arenson is the director of the National Center for Interprofessional Practice and Education and Professor in the Department of Family Medicine and Community Health at the University of Minnesota School of Medicine. Prior to joining the National Center, she served in a variety of academic and practice leadership roles at Thomas Jefferson University, including founding director of the Division of Geriatric Medicine and Palliative Care, founding co-director of the Jefferson Center for Interprofessional Practice and Education, and Chair of the Department of Family and Community Medicine. She has been engaged in academic-community partnerships and practice transformation at local and health system levels for over two decades.

Notes

1. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, Josiah Macy Jr. Foundation, and the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation. In 2016, the John A Hartford Foundation joined the three foundations to fund the National Center’s Accelerating Interprofessional Community-based Education and Practice Initiative.

2. Gail Jensen, PhD., Creighton University, Plenary, Nexus Summit 2021. Paraphrasing Mark Twain’s quote for IPE: “I have never let schooling interfere with my education.” September 14, 2021.

3. The use of the term “Nexus” refers to the vision for aligning practice and education. In 2020, the University of Minnesota trademarked the term, “NexusIPE,” to be used for programs and services offered by the National Center.

4. The term “people” collectively refers to patients/individuals, families, communities, and populations. The local context determines which term may be more appropriate.

References

- Archibald, D., Trumpower, D., & MacDonald, C. J. (2014). Validation of the interprofessional collaborative competency attainment survey (ICCAS). Journal of Interprofessional Care, 28(6), 553–558. https://doi.org/10.3109/13561820.2014.917407

- Association of Academic Health Centers. (1999). Catalysts in interdisciplinary education: Innovation by academic health centers. (Holmes, D. E., & Osterweis, M., Eds.).

- Baldwin, D. C. (1996). Some historical notes on interdisciplinary and interprofessional education and practice in health care in the USA. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 10(2), 173–187. https://doi.org/10.3109/13561829609034100

- Baldwin, D. C. (2013). Reforming medical education: Confessions of a battered humanist. In L. A. Headrick & D. K. Litzelman (Eds.), Educators’ stories of creating enduring change – enhancing the professional culture of academic health science centers (pp.195–221). Radcliffe Publishing, Ltd.

- Barr, H. (2015). Interprofessional education: The genesis of a global movement. ISBN:978-0-9571382-4-7.

- Barr, H., Koppel, I., Reeves, S., Hammick, M., & Freeth, D. (2005). Effective interprofessional education: Argument, assumption and evidence. Blackwell Publishing Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470776445

- Barton, A. J., Brandt, B. F., Dieter, C. J., & Williams, S. D. (2020). Nursing, interprofessional, and health professions education at a crossroads [Commissioned paper]. National Academies Press.

- Berwick, D. M., Nolan, T. W., & Whittington, J. (2008). The triple aim: Care, health and cost. Health Affairs, 27(3), 759–769. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.27.3.759

- Blue, A., Brandt, B. F., & Schmitt, M. H. (2010). American Interprofessional Health Collaborative: Historical roots and organizational beginnings. Journal of Allied Health, 39(1), 204–209.

- Bodenheimer, T., & Sinsky, C. (2014). From triple to quadruple aim: Care of the patient requires care of the provider. Annals of Family Medicine, 12(6), 573–576. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1713

- Brandt, B. F. (2022). Answering the vexing questions about organizing IPE in higher education. Journal of Interprofessional Education & Practice, 27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xjep.2022.100502

- Brandt, B. F. (2023). Creating a utopian future by asking uncomfortable questions. [Editorial]. Journal of Interprofessional Care, XXX.

- Brandt, B. F., Dieter, C., & Arenson, C. (2023). From Nexus vision to NexusIPE™ learning model. Journal of Interprofessional Care, XXX.

- Brandt, B. L., Farmer, J. A., Jr., & Buckmaster, A. (1993). Cognitive apprenticeship approach to helping adults learn. New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education, 1993(59), 69–78. https://doi.org/10.1002/ace.36719935909

- Brandt, B., Lutfiyya, M. L., King, J. A., & Chioreso, C. (2014). A scoping review of interprofessional collaborative practice and education using the lens of the Triple Aim. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 28(5), 393–399. https://doi.org/10.3109/13561820.2014.906391

- Brandt, B. F., & Schmitz, C. C. (2017). The US National Center for interprofessional practice and education measurement and assessment collection. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 31(3), 277–281. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2017.1286884

- Cerra, F. B., & Brandt, B. F. (2015). The growing integration of health professions education. In S. A. Wartman (Ed.), The transformation of academic health centers (pp. 81–90). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-800762-4.00009-8

- Cerra, F. B., Pacala, J., Brandt, B. F., & Lutfiyya, M. N. (2015). The application of informatics in delineating the proof of concept for creating knowledge of the value added by interprofessional practice and education. Healthcare, 3(4), 1158–1173. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare3041158

- Chen, F. M., Williams, S. D., & Gardner, D. B. (2013). The case for a national center for interprofessional practice and education. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 27(5), 356–`357. https://doi.org/10.3109/13561820.2013.786691

- Cullen, M., & Schmitz, C. C. (2015). Evaluating interprofessional education and collaborative practice: What should I consider when selecting a measurement tool?. National Center for Interprofessional Practice and Education.

- Delaney, C. W., AbuSalah, A., Yeazel, M., Kertz, J. S., Pejsa, L., & Brandt, B. F. (2020). National center for interprofessional practice and education IPE core data set and information exchange for knowledge generation. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2020.1798897

- Dochy, F., Gijbels, D., Segers, M., & Van den Bossche, P. (2022). Theories of workplace learning in changing times (2nd ed.). Routledge Taylor & Francis Group.

- Earnest, M., & Brandt, B. (2013). Building a workforce for the 21st century healthcare system by aligning practice redesign and interprofessional education. In M. Cox & M. Naylor (Eds.), Transforming patient care: Aligning interprofessional education with clinical practice redesign. Proceedings of a Conference sponsored by the Josiah Macy Jr. Foundation in January 2013 (pp. 37–54). Josiah Macy Jr. Foundation.

- Earnest, M., & Brandt, B. (2014). Aligning practice redesign and interprofessional education to advance triple aim outcomes. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 28(6), 497–500. https://doi.org/10.3109/13561820.2014.933650

- Erickson, E., & Chervany, H. (2018, May 3). Recommendations for the strategic focus of the National Center for Interprofessional Practice and Education Presentation. National Advisory Council.

- Fraher, E., & Brandt, B. (2019). Toward a system where workforce planning and interprofessional practice and education are designed around patients and populations not professions. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 33(4), 389–397. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2018.1564252

- Hall, P., & Weaver, L. (2001). Interdisciplinary education and teamwork: A long and winding road. Medical Education, 35(9), 867–875. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2923.2001.00919.x

- Health Professions Accreditors Collaborative. (2019). Guidance on developing quality interprofessional education for the health professions.

- Health Resources and Services Administration. (2012). New coordinating center will promote interprofessional education and collaborative practice in health care. ( Press release). US Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.hrsa.gov/about/news/press-releases/2012-09-14-interprofessional.html

- Hean, S., Craddock, D., & Hammick, M. (2012). Theoretical insights into interprofessional education: AMEE guide No. 62. Medical Teacher, 34(2), e78–101. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2012.650740

- Hean, S., Craddock, D., & O’halloran, C. (2009). Learning theories and interprofessional education: A user’s guide. Learning in Health and Social Care, 8(4), 250–262. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1473-6861.2009.00227.x

- Hendrick, B. J. (1914). Team work in healing the sick. The World’s Work, 2, 410–417.

- Institute for Healthcare Improvement. (2020). Age-friendly health systems: Guide to using the 4 Ms in the care of older adults. Institute for Healthcare Improvement. http://www.ihi.org/Engage/Initiatives/Age-Friendly-Health-Systems/Documents/IHIAgeFriendlyHealthSystems_GuidetoUsing4MsCare.pdf.

- Institute of Medicine. (1972). Educating for the health team: Report of the conference on the interrelationships of educational programs for health professionals (October 2-3, 1972). National Academy of Sciences.

- Interprofessional Education Collaborative Expert Panel. (2011). Core competencies for interprofessional collaborative practice: Report of an expert panel. Interprofessional Education Collaborative.

- McCreary, J. F. (1964). The education of physicians in Canada. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 90(21), 1215–1221.

- McCreary, J. F. (1968). The team approach for medical education. Journal of the American Medical Association, 205(7), 1554–1557. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1968.03150070092018

- Meizrow, J. (Ed.). (2000). Learning as transformation: Critical perspectives on a theory in progress. The Jossey-Bass higher and adult education series. Jorsey-Bass Publishers.

- National Academies of Sciences. (2021). Engineering, and Medicine. The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/25983

- Nisbet, G., Lincoln, M., & Dunn, S. (2013). Informal interprofessional learning: An untapped opportunity for learning and change within the workplace. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 27(6), 469–475. https://doi.org/10.3109/13561820.2013.805735

- O’Leary, N., Salmon, N., & Clifford, A. M. (2021). Inside-out: normalising practice-based IPE. Advances in Health Sciences Education, 26, 653–666. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-020-10017-8

- Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010, Pub. L. No. 111-148, 124 Stat. 119. (2010)

- Pechacek, J., Cerra, F., Brandt, B. F., Lutfiyya, M. N., & Delaney, C. (2015). Creating the summary of evidence through comparative effectiveness research for interprofessional education and collaborative practice by deploying a national intervention network and a national data repository. Healthcare, 3(1), 146–161. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare3010146

- Reeves, S., Fletcher, S., Barr, H., Birch, I., Boet, S., Davies, N., & Kitto, S. (2016). A BEME systematic review of the effects of interprofessional education: BEME guide no. 39. Medical Teacher, 38(7), 656–668. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2016.1173663

- Schmitt, M. (1994). USA: Focus on interprofessional practice, education, and research. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 8(1), 9–18. https://doi.org/10.3109/13561829409010397

- Schmitt, M. H. (2007). DeWitt C. Baldwin Jr., MD: An interprofessional celebration. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 21(sup1), 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820701642873

- Shrader, S., Ohtake, P. J., Bennie, S., Blue, A. V., Breitbach, A. P., Farrell, T. W., Hass, R. W., Greer, A., Hageman, H., Johnston, K., Mauldin, M., Nickol, D. R., Pfeifle, A., Stumbo, T., Umland, E., & Brandt, B. F. (2022). Organizational structure and resources of IPE programs in the United States: A national survey. Journal of Interprofessional Education & Practice, 26, 100484. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xjep.2021.100484

- Summerside, N., Blakeney, E. A. R., Brashers, V., Dyer, C., Hall, L. W., Owen, J. A., Ottis, E., Odegard, P., Haizlip, J., Liner, D., Moore, A., & Zierler, B. K. (2018). Early outcomes from a national train-the-trainer interprofessional team development program. Journal of Interprofessional Care. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2018.1538115

- ten Cate, O., & Pool, I. A. (2020). The viability of interprofessional entrustable professional activities. Advances in Health Sciences Education, 25(5), 1255–1262. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-019-09950-0

- Tilden, V. P., Eckstrom, E., & Dieckmann, N. F. (2016). Development of the assessment for collaborative environments (ACE-15): A tool to measure perceptions of interprofessional ‘teamness’. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 30(3), 288–294. https://doi.org/10.3109/13561820.2015.1137891

- Willgerodt, M. A., Blakeney, E. A. R., Summerside, N., Vogel, M. T., Liner, D. A., & Zierler, B. (2019). Impact of leadership development workshops in facilitating team-based practice transformation. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 34(1), 76–86. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2019.1604496

- World Health Organization. (2010). Framework for Action on Interprofessional Education & Collaborative Practice. WHO Press.

- Zierler, B., Brandt, B., Reeves, S., & Cox, M. (2016). Critically examining the evidence for IPE: Findings from an institute of medicine consensus committee. National Academies Press.