ABSTRACT

This article looks at the effects of power (conceived as complex and multi-directional) on the collaborative, interprofessional relationships of peer coaches when delivering implementation support. The study conducted ethnographic observations, semi-structured interviews and documentary analysis to evaluate the dynamics of peer coaching during the implementation of an evidence-based programme, Patient and Family Centred Care (PFCC), to improve 24 end-of-life care services. The article draws on perspectives from critical management studies to offer insights on the effect of organisational power on collaborations during the administration of peer coaching. This article details the difficulties that organisational power structures posed to interprofessional peer-coaching collaborations. Many of the peer coaches found it difficult to place their advice in the existing ethos of organisations, existing organisational hierarchies, or collaborate in the midst of staff turnover and general time management outside of their control. These considerations meant that successful peer-coaching collaborations and the success of the implementation programme were often divergent.

Introduction

This article focuses on the establishment of peer-coaching collaborations to provide implementation support in the scale up of an implementation programme using Patient and Family Centred Care (PFCC) methodology to improve end-of-life care services in the United Kingdom. We take a critical management theory perspective ((Alvesson, Bridgman & Willmot, Citation2011) that draws on Foucault and Science and Technology Studies) to assess the effect of organisational power on the peer-coach collaborations and implementation support. We use these theories to conceive of power as complex, multi-directional and productive, i.e. as means to make social interactions possible as much as they may constrain or prevent them. Stances of critical management theory demonstrate how interventions such as the PFCC attempt to discipline individuals to internalise power and then reproduce it on others. They are used here to analyse the many vested interests shared between services, their personnel and the programme management team.

Patient and family centred care

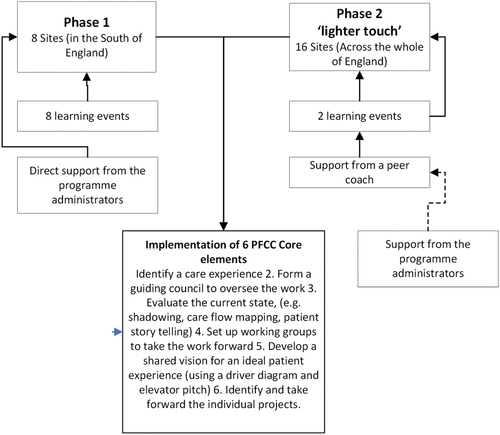

The programme analysed was initiated and managed by the Point of Care FoundationFootnote1 and ran in two stages. The first stage focused on delivering the programme to eight care service sites (a mix of in and outpatient services) with direct support from the programme administrators, and the second phase to further 16 sites using a more sustainable iteration of implementation support using peer coaching, termed by the programme administrators as “the lighter touch” (see appendix 1, figure a1).Footnote2 The lighter touch was a scaling technique designed to foster collaboration and bring about improvements with less effort, person-hours and intensive resources. This strategy relied on putting much of the responsibility for ensuring that teams stay on track in the hands of a team of coaches who were required to deliver implementation support and keep in regular contact with the teams. Then, in turn, the coaching teams received support and training from the programme administrators.

We focus on the second stage of the intervention, specifically the collaborations that were set up between peer coaches and their coachees. To scale up, the peer coaches were responsible for facilitating a series of strategies (Innovation Unit, Citation2017):

Retain key programme elements

Provide “lighter touch” project support

Provide clear guidance about what needs doing when

The administration of this support was then designed to take place at regular intervals over the phone between the coach and the programme lead at the site, where they would discuss their progress and issues encountered. The peer coaches were selected from services where successful implementation had been achieved in the first stage and comprised nurse practitioners (and one doctor, coach 4), and they were collaborating with professionals (doctors and nursing staff, a research and development manager and a quality improvement manager) at the 16 services implementing the programme. Each coach took on 2 or 3 sites apart from coach 4 (the doctor), who was specifically tasked with coaching doctors looking for support across different sites. Alongside peer coaching, the “lighter touch” also involved a series of learning events and direct implementation support from the programme administrators.

The PFCC method was originally developed by the Innovation Centre at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Centre (A. I. DiGioia & Greenhouse, Citation2011; A. M. DiGioia et al., Citation2015) and was adapted and refined by the programme administrators at the Point of Care Foundation. The programme was designed to establish infrastructure for improvement, understanding of the current and ideal states of the service and working to deliver improvements. The PFCC programme has six steps:

Identify a care experience

Form a guiding council to oversee the work

Evaluate the current state (e.g. shadowing, care flow mapping and patient story telling)

Set up working groups to take the work forward

Develop a shared vision for an ideal patient experience (using a driver diagram and elevator pitch)

Identify and take forward the individual projects.Footnote3

Principally, the active elements of the programme involve techniques of service mapping where staff chart a typical patients’ journeys through their service and service shadowing where individual professionals silently observe patients receiving care in their service. PFCC is designed to be a transformative experience for staff where they see their service from the perspective of service users and in the process not only see the problems with their service but are also able to empathise from the perspective of the patient and possibly anticipate their reactions to receiving care:

[PFCC is designed to create] a sense of empathy and urgency among caregivers by highlighting and clarifying the patient and family experience in a way that cannot be understood unless one ‘‘walks in their footsteps.’’ […] observation leads to empathy, which, in turn, leads to a sense of urgency and action; empathy is how we translate observations into insights. Traditional methods of asking people how to improve a service (e.g., focus groups and surveys) seem simple and logical, and they do have a role in PFCC; yet such methods usually lead to incremental improvements rather than insights that lead to innovation and transformation.

As can be seen, PFCC seeks to empower professionals to take responsibility for improvement. Such activities therefore have a direct effect on existing organisational power dynamics, as professionals may need to challenge or confront the existing status quo of their service. The coach’s role in this was to collaborate mainly with the professional responsible for implementation of the programme in a specific service and guide them through the implementation process. This project served as a test of the compatibility between PFCC methodology and the role of implementation support and collaboration in programme scale up. As such, using peer coaching to scale up PFCC implementation inadvertently expanded the role of implementation support as peer coaches felt the need to navigate organisational power dynamics and deal with the effects of vested interests when collaborating (Brotheridge & Grandey, Citation2002; Cropanzano et al., Citation2003).

Theories of implementation and power

Within the growing body of the literature on implementation science, implementation support and interprofessional collaboration power holds an important but perhaps ambiguous and underdeveloped role (Powell et al., Citation2015; Proctor et al., Citation2013; Waltz et al., Citation2014). Peer coaching is seen as a good tool to increase organisational capacity (Katz & Wandersman, Citation2016) especially when scaling up implementation and improvement programmes (Glasgow et al., Citation2012) over a large array of services where implementation programme directors may be spread thinly (many models have implementation support built into them for this reason (Hunter et al., Citation2009; Wandersman et al., Citation2012)). In many instances, the provision and delivery of collaboratory implementation support has been billed as crucial to the success of an implementation or improvement plan (Elliott & Mihalic, Citation2004; Meyers et al., Citation2012). Despite the importance placed on implementation support and interprofessional collaboration in implementation and improvement programmes, little literature has been developed that adopts a critical stance to its deployment. The overwhelming focus of the existing literature on implementation support using peer coaches is geared towards emphasising (unproblematically) the importance of collaboration (Damschroder et al., Citation2009; May & Finch, Citation2009; Rycroft-Malone, Citation2004). However, less attention has been paid to the power implications and inequalities (especially from critical perspectives) of implementation support strategies rooted in evidence-based practice, assessed as a means to improve effectiveness and efficiency, and the types of collaborations it brings about (Cohen Konrad et al., Citation2019). The success of implementation support from traditional perspectives is focused on fidelity, i.e. implementation support’s ability to implement programmes as intended (West et al., Citation2012, Metz & Bartley, Citation2012). Viewing support in this way obscures a wider view of the importance of interprofessional collaboration and the impacts implementation support may have on power dynamics and the experiences of staff being drafted into implementation programmes. Theories of critical management may be useful here to give a perspective on how power is present and emerges from every stage and member involved in interprofessional collaboration discourse. This will be used to determine how the PFCC attempts to engineer compliance by organising individuals to take responsibility for their role in implementing the intervention, and in so doing also enforcing others. We aim to demonstrate some of the many vested interests that result through interprofessional collaboration organised around implementation support.

The deployment of implementation support, therefore, should avoid describing improvements as occurring in a vacuum. Many indicators of implementation support success may not be understood as a simple list or set of rules, but as implementation support success in building effective collaborations and responsiveness to sensitive interdependent organisational structures, vested interests and unintended consequences. Existing strategies of implementation tend to explain such issues in implementation support as “contextual factors,” “organizational complexities” or “cultural factors” (Dopson & Fitzgerald, Citation2006; Scott et al., Citation2003). However, conglomerating a large range of complex activities to a label such as context (or to pose its definition unproblematically or without critique) is a simplification of a much larger set of interrelations than may be involved in collaborations (Checkland et al., Citation2007; Grey & Willmott, Citation2002). This is especially important given the setting of study in end-of-life services in busy NHS settings not easily reducible to the simple term of context. The field often mitigates these considerations with the use of wider support strategies that avoid relying solely on direct support from coaching or supervision (such as the team training workshops that were also part of the programme we observed).Footnote4 What we wish to question, however, is the extent to which power can ever be fully anticipated or accounted for as each interaction brings with its new collaborations, rationales and power dynamics. As a result, this article focuses on the power structures encountered during the deployment of collaborative peer coaching as having multiple vested and conflicting interests (Ezzamel & Willmott, Citation1998; Hardy & O’Sullivan, Citation1998), such as the need for those giving support to be aware of the ethos, hierarchies, structures and working conditions of the organisations implementing improvements.

Method

This article uses data collected during the course of an evaluation of the PFCC programme. The predominant approach to evaluate the programme was ethnography, as a means to provide rich accounts of activities, projects and programmes and highlight some of the complex power dynamics involved (Hammersley & Ethnography, Citation1983). Observations, interviews and documentary analysis were incorporated into research to vary the lines of inquiry (Denzin, Citation1988, Citation2003).

Data collection involved semi-structured interviews conducted with 5 of the 8 coaches who were supporting the teams and semi-structured interviews were also conducted with the programme administrators. Additionally, a sample of the sites (8 from 16) was also chosen to conduct semi-structured interviews with professionals who had conducted implementation and been in contact with a peer coach. This included consultants and nursing staff, a research and development manager and a quality improvement manager and was part of complicated hierarchies involved in service provision and quality improvement at their respective sites. The interviews were conducted either face to face or over the telephone and used a loose topic guide to prompt participants and were recorded and transcribed.

Observations were conducted of programme events, i.e. learning events, and celebration events for coaches and service staff. Observations involved RB participating in the events and taking field notes when convenient. The sites were selected based on three criteria: types of healthcare setting, geographical spread within the programme area (England) and rural/urban mix (note some of the interviews were conducted by telephone to save staff time and travel costs). The evaluation of phase 2 of the research was also supplemented by the research of phase 1 where all eight services were either involved in a site visit, focus group or were interviewed by telephone (see Appendix 1 figure a2 for full details of the methods used). A large array of project documents was also made available to the team where two documents were identified relevant to the selection criteria of coaches and included in the analysis. The data collected from the evaluation which included interview transcripts, observation field notes and project documents were uploaded into NVivo and then analysed using grounded theory coding techniques that allowed emergent themes around interprofessional collaboration, implementation support activities and power to emerge from the data.

Findings

Peer coach selection

The success of the scale-up phase was seen as crucially influenced by the skill of the coaches. The programme administrators placed an emphasis on identifying potential coaches that they felt would have sufficient skills to guide teams through the programme effectively. The coaches were selected from the previous PFCC cohort, providing an element of peer support and tapping into the experiential learning of programme participants. In particular, participants from successful phase one sites were encouraged to apply. The original application form asked applicants to write a paragraph in response to each of the points below and to identify a senior sponsor:

What advice you would give to new teams in setting up their project?

What the best achievement was of your own PFCC project?

However, despite the structured approach to coach selection and the provision of training and ongoing support, credibility was debatable across the coaches:

One of the interesting things we had a long chat with [Anon.] about was whether the fact that she’s got such subject credibility, because she’s a specialist nurse means that she’s been so much more trusted, and she thinks it probably has had an impact, but others have been very successful as well who haven’t got it. So I think it might be an important thing for her, but I don’t think it’s an important thing for everybody. (Programme Administrator 1)

This meant that some coaches provided support in line with that anticipated by the programme administrators and have felt comfortable in the role whilst others did not. Explanations as to why this was the case varied. There was some speculation among the programme administrators as to what good coaching skills entailed, but most often, the peer coaches who were reported to have collaborated well were able to provide implementation support as well as wider organisational support.

This was reflected by peer coaches who felt that they had to show their own initiative in order to be able to carry out the role:

Yes, I mean we’ve become friends really; it’s quite a nice, friendly relationship. I think they like the phone calls just because it helps them take stock of everything they’ve done in the last month. Really I feel like I’m just encouraging and validating how well they seem to be doing, that’s the way it feels now. I met them at the learning event and just by meeting them too you just feel like they’re really fantastic staff and they’re just doing a really good job. I don’t feel like I’m probably contributing a huge amount, it’s just more of a kind of support and friendly kind of, what’s the word, just a sort of friendly hand-hold really of just carrying on with it really. (Coach 3)

As a result, even though the application process for peer coach selection and the programme activities anticipated some of the demands coaches would face, it was difficult to predict with certainty who would thrive in the peer-coaching role.

Organisational culture

This unpredictable aspect can be further demonstrated when assessing exactly what went wrong when collaborations failed in the cases that caused concern. The attempt to build supportive collaborations with existing organisation structures raised a number of issues concerning the culture of participating services. One difficulty raised was the ability of peer coaches to adapt their support around the services they were coaching to. Some sites cited a complex organisational culture that they found difficult to explain to their coaches and collaboration failed to flourish as a result:

[O]ne of the reasons we signed up to do it [was] because it absolutely chimes with the ethos of what we’re trying to do as a team in an older person’s unit, people living with frailty … .I felt sometimes that we were trying to shove a square peg into a round hole just because it was the format of the model. One of the things that we’re trying to do is to create an understanding about frailty as an end-of-life state. In other words, if somebody is diagnosed as severely frail, they are approaching the end of their lives. Even if that end may be two or three years away, they’re approaching it. Now, how you can shadow a family when actually if our staff don’t understand that, how do we enable families to understand that? So one of the things that we were really focusing on was staff training and I think it’s been very difficult [to communicate that with a peer-coach]. (Scale up site 1 General Practitioner)

The service quoted here found it difficult to arrange regular meetings with their peer coach. In the example above, the organisation demonstrated how the programme had a good fit with the existing culture of the organisation but had difficulty in translating the programme activities into their culture. Other organisations also reported that they had a good relationship with their coach but had varying success in implementing PFCC:

“The coaching was helpful, but it has spiralled a little bit out of my control. So what’s happened is we split it into a few things. We’ve been looking at the environment on the ward, we’ve been looking at improving staff confidence in having these conversations about improvements to the service […] So the things I found most helpful were getting the core group, feeling empowered to get the higher level managers on board to sort of properly instil the changes, and also working out how we can evaluate it, so with the metrics, and how we can use both run charts and other more qualitative data to show the improvements. So it’s been a steep learning curve,

In this quote, like the one above, the staff member had varying confidence at how well the PFCC approach had worked; they felt that they put in a lot of work collaborating and translating the programme into their existing structure but lamented the lack of control they have felt over the process. We can question here how much this sentiment can be linked to the strategy of the lighter touch. The PFCC programme emphasises both shadowing and care plan mapping as exploratory methods not intended to impose a structure upon participants but for participants to use to explore their own structure. As coaches had limited contact with service personnel (in this case, the staff member interviewed was the sole contact that the peer coach had engaged with), this may have had an impact on programme delivery. When administered in phase 1, the programme team had more contact with the teams at learning events and more scope to get this point across. Similar questions were observed to take place at learning events during phase 1 and 2, and of the eight teams involved in phase 1, 1 dropped out due to a concern with administering the programme in their service structure, which demonstrates that it was a concern over both phases (excerpt from fieldnotes from phase 1 learning events 3 and 4). However, in phase 2, coaches were on their own to answer these questions, keep teams on track and avoid any noncompliance reflecting badly upon them. One aspect of successful coaching, therefore, was if coaches had the ability to collaborate with relevant personnel in the complex organisational structures they were seeking to help to improve (Persaud, Citation2004; Smith, Citation2011). This decouples perceived implementation successes from coaching success as with the example above, some services deemed their implementation programme to have been a success despite having not engaged with their coach.

Hierarchy

The issue of organisational culture can be linked to the adaption of the programme around the existing hierarchies of participating organisations. The PFCC toolkit given to participating staff cites as important two hierarchical aspects:

“Executive sponsorship and organizational attention.”

“The engagement of doctors.”

(Excerpt from analysis of the PFCC toolkit)

Participants were also very alert to the potential for hierarchical issues:

[The structure of the intervention is] clearly done in a certain way. People are expected to jump through certain hoops. There is significant arms’-length support in actually getting people to the right stage in terms of their projects, in terms of getting high-level support within organisations, getting a team structure, getting all those bits in the jigsaw that need to come together in order to create a project that potentially has sustainable life. (Scale up site 1 General Practitioner)

What is highlighted here is the awareness of how wider collaboration is needed to ensure that staff implementing the programme can navigate their services hierarchy. This was recognised as a very real threat as in other sites the hierarchy of the services had a direct impact on the effectiveness of the programme and in some instances was the cause of unsuccessful implementation. For example, a team observed during both the learning and celebration events explained that they had been delegated to attend the events by more senior members of their team rather than as the result of a more inclusive and collaborative relationship. When questioned by the programme administrators, they found it very difficult to recount the details of the programme or who was responsible for the programme at their site (excerpt from fieldnotes from phase 2 learning event 2). Although this seemed to be an isolated incident, it did highlight the importance of the organisational readiness and commitment to build effective collaborations.

In contrast to the first stage of the programme where more support was offered to the teams, as the coaches would be working more with one individual team member who would then organise the rest of the group, the second “lighter touch” phase seemed to make the structure and existing interprofessional collaboration in the participating organisations more important. To alleviate this challenge, the programme administrators identified a coach to work specifically with doctors linked to the projects. The aim of having a dedicated coach for doctors was to engage more members of the participating teams and work within existing hierarchical structures:

So having run it before, and this is what [the programme administrators] have come up with, is trying to get more doctors involved with the - and it was set up with two doctors as well, [XXXX and XXXX]. They were keen to get doctors specifically involved, and so that was my remit. Whatever it takes, within reason, keep it legal, we’ll - it’s not about sticking religiously to the methodology, because that was absolutely the line that we took with the collaborative. It’s stick to the methodology, do what we are asking you to, and you will be amazed at the power of what you are learning. It was bringing the doctors in to - if I can interest you in a communications tool that you can use as an intervention, how will that work? Where does that fit in with shadowing? That sort of thing. It wasn’t that I was giving a different methodology to them. It was that I was adding to the knowledge bank of the collaborative or the theory, the connections, the application. (Coach 4)

This additional support helped guide the service hierarchy as it specifically targeted how doctors could best collaborate with other professionals in their organisation. When less support was offered, the services themselves needed to find ways in which to support members of staff that participated in the programme. Peer coaches relied upon doctors in services to be motivated either to seek out the coaching or to get involved with implementation. As the support got lighter, more onus was on service staff with influential positions of power to take responsibility for effective collaboration. Good peer coaching therefore had a strong political aspect to it (Florin et al., Citation1993; Martin, Citation1952). The more effective the structure of the organisation was in supporting all staff regardless of position, the more likely it seemed to be that staff would collaborate together with the coaches and support implementation of the PFCC. This was easier to manage in phase 1 as there were more support sessions and more time for participants to work together as a team than in phase 2, making the programme more visible and enrolling more of staff (see appendix 1). In phase 2, there was more potential for different members of staff to see issues differently depending on their place in the hierarchy, this aspect of peer coaching could be said to be not immediately concerned with the fidelity of the intervention in terms of support, but rather on harmonising the organisational culture to work together.

Staff turnover

Another challenge to implementation support was the high staff turnover at participating sites. This meant that many of the organisational structures of the services were constantly changing during the course of the programme, and further limiting the depth and breadth of relationships, a peer coach could have with a participating service:

The core team, it’s sort of shrunk. I think we started at eight and it’s probably now four. I think we’re working with an engaged group of people within the unit; probably about 20, I suppose.

Teams at other sites also highlighted difficulties presented by high staff turnover:

“So it’s been in flux. I think we started off with eight, and then at one point we’d managed to drop to two, and now we’re back up to six. There’s a high staff turnover.

Has there been a high staff turnover for the duration of the running of the project?

So every staff member is really only turned over once, but I think, apart from two of us, we’ve all turned over. So apart from two of us, it’s not the same people now that it was at the beginning … There have been lots of people who’ve been really engaged and wanted to change. I think it’s quite a good area. It’s really relevant to our ward, and it’s one of the priorities for the trust and the community, so everyone’s been very supportive and very positive about it.” (Scale up site 2 Associate Director Research)

Another example:

We’ve been decimated by maternity.

So some people have gone on maternity?

Two people have gone off on maternity. Three people have left their posts.

Do you think that had an impact on the programme?

It definitely made it harder, because I’m part-time, so time has been an issue; there’s just not enough time. People have actually been really engaged, but a lot of people need the - you need direction, you need to meet, you need to make sure things are still moving, and that’s the side of things that has been more difficult. Oh, I completely forgot, sorry; there are three of us from the core group. There’s also [another one], [XXXX]. She’s been there from the start as well. She’ll kill me if I’ve forgotten her.” (Scale up site 2 Associate Director Research continued)

Staff turnover was also a problem that the peer coaches thought had impacted the implementation of the programme:

I think the [XXXX] team had problems where the original team that were going to do the work has actually changed over time so it’s been quite difficult for them I think to cover the ground really. (Coach 2)

Another example:

One of them has had a change of job; right at the beginning of the coaching she was being interviewed for a new job of a dementia specialist role and she got that role. Then it was about whether she really wanted it so we kind of went into some of her personal thinking and reflections and so she’s had a quite big change of role too early on in the process but she’s still doing the job she’s in until January; but it’s kind of looking a little bit about her personal changes too that are going on. (Coach 3)

As turnover became more pronounced, the role of peer coach changed from one of the intervention support to supporting staff members through career and service changes. Interventions are powerless in the face of these dynamics, as in many cases they are the results of outside social, political or cultural processes (which is especially pronounced in healthcare systems such as the NHS) (Gray & Smith, Citation2000; Kelly et al., Citation2000). Such dynamics caused coaches to blur professional boundaries and to offer support on staff turnover, which they may not have had the management expertise required to deliver effectively. The use of peer coaching to guide implementation around staff shortages was against the design of the programme and beyond the training peer coaches were given and raises questions about the fidelity demands of the programme. One of the tips for success detailed in the programme handbook advises teams to:

Hav[e] a sense of where you would like PFCC to sit in your organisation in the longer term. (Excerpt from analysis of the PFCC programme handbook)

In the face of high staff turnover and the possibility that teams had little control over the longer term, peer coaches may have been put in the position where they question whether they should prioritise supporting staff over and above the success of the intervention.

Time management

Another instance of organisational structures influencing collaboration was the expression that teams had to manage their time effectively in order to organise opportunities for collaboration and implementation of the programme. Most of the onus for time management was up to the teams themselves:

I thought they [Point of Care Foundation] were extremely helpful. I like the fact that they kept us to the deadline which we needed, because as you know, life takes over so quickly. (Scale up site 3 Generative Consultant)

Time management was an issue felt by several teams, and it was also something felt by peer coaches to have had a big impact on the quality of their collaboration:

I think sometimes you know when people are really busy and they’re juggling things and you’re very aware of that and you are making sure you use that time appropriately and you’re helpful to them. I guess it’s always that juggling feeling. I think the other thing I think from my experience of receiving coaching is it helps you gather your thoughts and concentrate on what you need to, and also keeps you on track, because weeks go by and you think oh my goodness have I done that? I think having someone phone you up and saying, ‘How’s it going?’ keeps you focussed I’d say. (Coach 2)

Another example:

“The anxieties they’ve had around pressure of work, just the amount of things they’re having to do with their day job targets and they’ve had CQC inspections and the general pressure of the NHS and wondering if they’re going to manage to do anything extra to what they have to do in their day job. That’s a general thing. (Coach 3)

The variability of the coaching and their limited contact with the services meant that coaches who were themselves better at time management and enabling teams to schedule regular appointments were more able to support organisations in collaboration and sticking to the programme. Implementation support in this sense had to be sensitive to wider anxieties felt by the teams in order to make the intervention one of their priorities. Successful coaches were the ones taking on these extra anxieties. But it should also be stressed that it was a two-way relationship and service teams often also needed to communicate with their coaches effectively to ensure a good rapport. However, in these circumstances, it can be questioned if the sense of success felt by the peer coaches and programme fidelity amounted to one and the same thing, i.e. that successfully collaborating to agree on what would represent positive change was more important that systematically replicating the programme and all its steps entirely.

Discussion

This study looks at power in the scaling up of the PFCC programme using peer coaching. Our findings demonstrate that in order to be effective, peer coaches were required to foster collaboration in accordance with the sensitivities that organisations were operating within (Brotheridge & Grandey, Citation2002; Yoo et al., Citation2014). In this process, we argue that successful peer coaching is defined by how well collaborations are built in complex organisational power structures (Sabatier, Citation1986). Conceptualising power as multi-directional and productive revealed much peer coach flexibility and adaptation in the collaborations observed that was above and beyond the role of a peercoach as implied in the intervention handbook. Every organisation in the programme displayed their own culture variances and the untranslatability of cultural differences or ethos was used in itself as an excuse to withdraw from the programme or to not comply. In PFCC methodology and implementation literature, flexibility comes into conflict with the concept of “fidelity” – i.e. the extent to which it is possible to adapt the programme before it no longer resembles the original intervention (Elliott & Mihalic, Citation2004). The programme administrators saw big variability across the two phases. The amount to which the teams followed the methodology varied from team to team. In these instances, coaches found themselves in the tricky position of needing to ensure that coaches could still maintain some rapport with services that may be at the expense of not implementing all aspects of the intervention fully (Hamdallah et al., Citation2006). Issues observed included some organisations not implementing all six steps of the programme, and there being discrepancies over the extent different staff members across the organisation were involved in the programme. Success in terms of collaboration therefore was often at odds with implementation strategies employing a strict sense of fidelity, and consequently a complicated, multi-directional power dynamic between the peer coaches, the service teams and the programme administrators was created. Several coaches and coachees were observed to evaluate the importance and usefulness of the collaborations they formed decoupled from implementation success.

This finding is influenced in a large part by the ways in which the intervention defined success. Under the guidance of the programme administrators, service teams were asked to define what success would look like before beginning the programme, and the meaning of success needed to be established in constant dialogue with the professionals themselves. This is inherently helpful in making success measurable but does not account for how failures are constituted. The more that implementation programmes such as the one explored can involve individuals across the whole of service hierarchies and cultures, the more chance they have to be supported. Implementation or improvement activities cannot be practiced in a powerless vacuum; its deployment affects and is affected by the multitude of vested interests involved in any situation it intervenes within. The implementation of the programme has coincided with crises in funding and staffing turnover of the UK NHS and has had knocked on effects to age-old issues of working conditions in tough, emotionally laden services such as end-of-life care (Hospice Friendly Hospitals Programme, Citation2013). The solution to these issues could be said to lie not in the technical part of implementation support, but the collaborations formed by a politically astute, well-experienced ear. As a result, peer coaches found themselves building collaborations caught between broader issues of organisational power and programme considerations (Aarons et al., Citation2017; Durlak & DuPre, Citation2008; Mitchell et al., Citation2002).

Conclusion

The success of the collaborations hinged partly upon the ability of the peer coach and the power dynamics observed. Participants reacted favorably to the lighter touch implementation support approach, valuing the degree of local discretion that it entailed alongside the collaborations they built with the coaches. The PFCC programme was designed so that the teams adopting it would find it as easy as possible to follow, and coaches were selected and supported to have the necessary collaborative skills to guide others through the programme. Despite this, many aspects of the success of the interprofessional collaborations overall were beyond the scope of implementation support, the peer coaches personally, or the programme administrators. Aspects such as the culture of the organisation; or the organisational hierarchy; or the amount of staff turnover; or staff members’ disposition were all important power factors that are outside of the scope of the peer coaches (McClellan et al., Citation2010; Yazejian et al., Citation2019). Therefore, successful peer-coaching collaborations and implementation success may not always be mutually inclusive, depending upon the ways in which power is accounted for, which may leave some peer coaches in a difficult position.

Abbreviations

| PFCC | = | Patient and Family Centred Care Declaration |

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This project was ethically approved by London – Surrey Borders Research Ethics Committee (16/LO/2197) on 01 March 2017. The project’s IRAS ID is 219,263. All participants provided written informed consent before participation.

Availability of data and materials

Due to the sensitivity of the data and ethical obligations, study data are not generally available to people outside the evaluation team.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the contribution of all members of the Point of Care Foundation, the Health Foundation, and the steering group who helped to shape this project. Many thanks to Bev Fitzsimons, Louise Locock and Allison Metz who read over previous versions of this manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Richard Boulton

Richard Boulton is a Lecturer at St George's, University of London. His research interests include how methodologies of the social scences cross over between implementation and improvement and evidence based practice.

Annette Boaz

Annette Boaz is a Professor of Health Care Research with over 25 years experience in supporting the use of evidence across a range of policy domains. She has a particular research interest in stakeholder involvement, the role of partnerships in promoting research use, implementation science and service improvement.

Notes

1. The Point of Care Foundation is an independent charity that undertakes research to identify and test the most promising interventions to promote patient-focused improvement in the NHS. https://www.pointofcarefoundation.org.uk/.

2. These approaches to implementation support have parallels to versions of Technical Assistance that are of growing prevalence and extensivity in the USA but as yet remain relatively underdeveloped in UK healthcare settings(2–4).

3. More details can be found in the Point of Care Foundation toolkit: https://www.pointofcarefoundation.org.uk/resource/patient-family-centered-care-toolkit.

4. See for example the broad range of resources developed in technical assistance centers such as this one: https://ectacenter.org/portal/ecdata.asp.

References

- Aarons, G. A., Sklar, M., Mustanski, B., Benbow, N., & Brown, C. H. (2017, Sep). “Scaling-out” evidence-based interventions to new populations or new health care delivery systems. Implementation Science, 12(1), 111. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-017-0640-6

- Alvesson, M., Bridgman, T., & Willmot, H., Eds. (2011). Chapter 1 Introduction. The Oxford Handbook of Critical Management Studies (pp. 28). Oxford University Press .

- Brotheridge, C. M., & Grandey, A. A. (2002, Feb). Emotional labor and burnout: Comparing two perspectives of “People Work”. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 60(1), 17–39. https://doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.2001.1815.

- Checkland, K., Harrison, S., & Marshall, M. (2007, Apr). Is the metaphor of “barriers to change” useful in understanding implementation? Evidence from general medical practice. Journal of Health Services Research & Policy, 12(2), 95–100. https://doi.org/10.1258/135581907780279657

- Cohen Konrad, S., Fletcher, S., Hood, R., & Patel, K. (2019, Sep). Theories of power in interprofessional research – developing the field. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 33(5), 401–405. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2019.1669544

- Cropanzano, R., Rupp, D. E., & Byrne, Z. S. (2003). The relationship of emotional exhaustion to work attitudes, job performance, and organizational citizenship behaviors. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(1), 160–169. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.1.160

- Damschroder, L. J., Aron, D. C., Keith, R. E., Kirsh, S. R., Alexander, J. A., & Lowery, J. C. (2009, Aug). Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: A consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implementation Science, 4(1), 50. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-4-50

- Denzin, N. K. (1988). The research act: Theoretical introduction to sociological methods (3rd Revised ed.). Prentice-Hall.

- Denzin, N. K. (2003). Performance ethnography: Critical pedagogy and the politics of culture. Sage Publications, Inc.

- DiGioia, A. I., & Greenhouse, P. K. (2011, Jan). Patient and family shadowing: Creating urgency for change. The Journal of Nursing Administration, 41(1), 23. https://doi.org/10.1097/NNA.0b013e3182002844

- DiGioia, A. M., Greenhouse, P. K., Chermak, T., & Hayden, M. A. (2015, Dec). A case for integrating the patient and family centered care methodology and practice in lean healthcare organizations. Healthcare, 3(4), 225–230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hjdsi.2015.03.001

- DiGioia III, A., Lorenz, H., PK, G., DA, B., & SD, R. (2010). A patient-centered model to improve metrics without cost incrEase: Viewing all care through the eyes of patients and families. JONA: The Journal of Nursing Administration, 40(12), 540–546. https://doi.org/10.1097/NNA.0b013e3181fc1

- Dopson, S., & Fitzgerald, L. (2006, Jan). The role of the middle manager in the implementation of evidence-based health care. Journal of Nursing Management, 14(1), 43–51. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2934.2005.00612.x

- Durlak, J. A., & DuPre, E. P. (2008, Mar). Implementation matters: A review of research on the influence of implementation on program outcomes and the factors affecting implementation. American Journal of Community Psychology, 41(3–4), 327. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-008-9165-0

- Elliott, D. S., & Mihalic, S. (2004, Mar). Issues in disseminating and replicating effective prevention programs. Prevention Science, 5(1), 47–53. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:PREV.0000013981.28071.52

- Ezzamel, M., & Willmott, H. (1998). Accounting for teamwork: A critical study of group-based systems of organizational control. Administrative Science Quarterly, 43(2), 358–396. https://doi.org/10.2307/2393856

- Fixsen, D., Blase, K., Metz, A., & Van Dyke, M. (2013, Jan). Statewide implementation of evidence-based programs. Exceptional Children, 79(2), 213–230. https://doi.org/10.1177/0014402913079002071

- Florin, P., Mitchell, R., & Stevenson, J. (1993). Identifying training and technical assistance needs in community coalitions: A developmental approach. Health Education Research, 8(3), 417–432. https://doi.org/10.1093/her/8.3.417

- Glasgow, R. E., Vinson, C., Chambers, D., Khoury, M. J., Kaplan, R. M., & Hunter, C. (2012, Jul). National institutes of health approaches to dissemination and implementation science: Current and future directions. American Journal of Public Health, 102(7), 1274–1281. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2012.300755

- Gray, B., & Smith, P. (2000). An emotive subject: Nurses’ feelings. Nursing Times, 96(27), 29–31.

- Grey, C., & Willmott, H. (2002). Contexts of CMS. Organization, 9(3), 411–418. https://doi.org/10.1177/135050840293006

- Hamdallah, M., Vargo, S., & Herrera, J. (2006, Aug). The VOICES/VOCES success story: Effective strategies for training, technical assistance and community-based organization implementation. AIDS Education and Prevention, 18(supp), 171–183. https://doi.org/10.1521/aeap.2006.18.supp.171

- Hammersley, M., & Ethnography, A. P. (1983). Principles in practice. Taylor & Francis.

- Hardy, C., & O’Sullivan, S. (1998, Apr). The power behind empowerment: Implications for research and practice. Human Relations, 51(4), 451–483. https://doi.org/10.1177/001872679805100402

- Hospice Friendly Hospitals Programme. (2013). End of life care and supporting staff: A literature review [Internet]. Irish Hospice Foundation. http://endoflifecareambitions.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Ambitions-for-Palliative-and-End-of-Life-Care.pdf

- Hunter, S. B., Chinman, M., Ebener, P., Imm, P., Wandersman, A., & Ryan, G. W. (2009, Oct). Technical assistance as a prevention capacity-building tool: A demonstration using the getting to outcomes® framework. Health Education & Behavior, 36(5), 810–828. https://doi.org/10.1177/1090198108329999

- Innovation Unit. (2017). AGAINST the ODDS: Successfully scaling innovation in the NHS [Internet]. The Health Foundation. https://www.innovationunit.org/wp-content/uploads/Against-the-Odds-Innovation-Unit-Health-Foundation.pdf#page=22

- Katz, J., & Wandersman, A. (2016, May). Technical assistance to enhance prevention capacity: A research synthesis of the evidence base. Prevention Science, 17(4), 417–428. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-016-0636-5

- Kelly, D., Ross, S., Gray, B., & Smith, P. (2000, Oct). Death, dying and emotional labour: Problematic dimensions of the bone marrow transplant nursing role? Journal of Advanced Nursing, 32(4), 952–960. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2648.2000.t01-1-01561.x

- Martin, R. C. (1952). Technical assistance: The problem of implementation. Public Administration Review, 12(4), 258–266. https://doi.org/10.2307/972490

- May, C., & Finch, F. T. (2009, Jun). Implementing, embedding, and integrating practices: An outline of normalization process theory. Sociology, 43(3), 535–554. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038509103208

- McClellan, M., McKethan, A. N., Lewis, J. L., Roski, J., & Fisher, E. S. (2010, May). A national strategy to put accountable care into practice. Health Affairs, 29(5), 982–990. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0194

- Metz, A., & Bartley, L. (2012). Active implementation frameworks for program success: How to use implementation science to improve outcomes for children. Zero to Three, 32(4), 11–18.

- Meyers, D. C., Durlak, J. A., & Wandersman, A. (2012, Dec). The quality implementation framework: A synthesis of critical steps in the implementation process. American Journal of Community Psychology, 50(3–4), 462–480. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-012-9522-x

- Mitchell, R. E., Florin, P., & Stevenson, J. F. (2002, Oct). Supporting community-based prevention and health promotion initiatives: Developing effective technical assistance systems. Health Education & Behavior, 29(5), 620–639. https://doi.org/10.1177/109019802237029

- Persaud, R. (2004, Aug). Faking it: The emotional labour of medicine. The BMJ, 329(7464), s87–s87. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.329.7464.s87

- Powell, B. J., Waltz, T. J., Chinman, M. J., Damschroder, L. J., Smith, J. L., Matthieu, M. M., Proctor, E. K., & Kirchner, J. E. (2015, Feb). A refined compilation of implementation strategies: Results from the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) project. Implementation Science, 10(1), 21. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-015-0209-1

- Proctor, E. K., Powell, B. J., & McMillen, J. C. (2013, Dec). Implementation strategies: Recommendations for specifying and reporting. Implementation science : IS, 8(1), 139. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-8-139.

- Rycroft-Malone, J. (2004). The PARIHS framework—a framework for guiding the implementation of evidence-based practice. Journal of Nursing Care Quality, 19(4), 297–304. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001786-200410000-00002

- Sabatier, P. A. (1986, Jan). Top-Down and Bottom-Up approaches to implementation research: A critical analysis and suggested synthesis. Journal of Public Policy, 6(1), 21–48. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0143814X00003846

- Scott, T., Mannion, R., Marshall, M., & Davies, H. (2003, Apr). Does organisational culture influence health care performance? A review of the evidence. Journal of Health Services Research & Policy, 8(2), 105–117. https://doi.org/10.1258/135581903321466085

- Smith, P. (2011). The emotional labour of nursing revisited: Can Nurses Still Care?. Macmillan International Higher Education.

- Waltz, T. J., Powell, B. J., Chinman, M. J., Smith, J. L., Matthieu, M. M., Proctor, E. K., Damschroder, L. J., & Kirchner, J. E. (2014, Mar). Expert recommendations for implementing change (ERIC): Protocol for a mixed methods study. Implementation Science, 9(1), 39. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-9-39

- Wandersman, A., Chien, V. H., & Katz, J. (2012, Dec). Toward an evidence-based system for innovation support for implementing innovations with quality: tools, training, technical assistance, and quality assurance/quality improvement. American Journal of Community Psychology, 50(3), 445–459. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-012-9509-7

- West, G. R., Clapp, S. P., EMD, A., & Cates, W. (2012, Oct). Defining and assessing evidence for the effectiveness of technical assistance in furthering global health. Global Public Health, 7(9), 915–930. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2012.682075

- Yazejian, N., Metz, A., Morgan, J., Louison, L., Bartley, L., Fleming, W. O., Haidar, L., Schroeder, J. (2019). Co-creative technical assistance: Essential functions and interim outcomes [Internet]: Policy Press.https://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/tpp/ep/2019/00000015/00000003/art00002

- Yoo, W., Namkoong, K., Choi, M., Shah, D. V., Tsang, S., Hong, Y., Aguilar, M., & Gustafson, D. H. (2014, Jan). Giving and receiving emotional support online: Communication competence as a moderator of psychosocial benefits for women with breast cancer. Computers in Human Behavior, 30(0), 13–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.07.024

Appendix 1

Appendix 2

Table A1. Data collection methods.