ABSTRACT

Speaking up for patient safety is a well-documented, complex communication interaction, which is challenging both to teach and to implement into practice. In this study we used Communication Accommodation Theory to explore receivers’ perceptions and their self-reported behaviors during an actual speaking up interaction in a health context. Intergroup dynamics were evident across interactions. Where seniority of the participants was salient, the within-profession interactions had more influence on the receiver’s initial reactions and overall evaluation of the message, compared to the between profession interactions. Most of the seniority salient interactions occurred down the hierarchy, where a more senior professional ingroup member delivered the speaking up message to a more junior receiver. These senior speaker interactions elicited fear and impeded the receiver’s voice. We found that nurses/midwives and allied health clinicians reported using different communication behaviors in speaking up interactions. We propose that the term “speaking up” be changed, to emphasize receivers’ reactions when they are spoken up to, to help receivers engage in more mutually beneficial communication strategies.

Introduction

Speaking up in the healthcare context is explicit communication that challenges the status quo, for the prevention of error and/or harm (physical and/or psychological) to healthcare staff and patients (Lyndon et al., Citation2012; Morrison, Citation2014). The importance of speaking up for patient safety in the health context is well documented and shown to enhance patient safety through medical error prevention and risk mitigation (World Health Organisation, Citation2019). However, speaking up is not consistently applied in practice, and so patients and staff are still at risk. Healthcare organizations implement speaking up training that routinely teaches clinicians (from all professions and seniority levels) conversational mnemonics to help speakers phrase their concerns (e.g., CUS: I’m Concerned, I’m Uncomfortable, this is a Safety issue; Hanson et al., Citation2020). These mnemonics are used to voice a concern regardless of the context and who the receiver is (seniority, profession).

Unfortunately, such interventions are resistant to training due to preexisting dynamics, such as hierarchy (Jones et al., Citation2021). Previous research on speaking up has identified that speakers, before speaking, consider trade-offs between voice and silence, and whether the cost-benefit of speaking up is greater than staying silent (Noort et al., Citation2021). Possible cost considerations include fear of damage to existing relationships, the psychological safety of the speaker due to fear of repercussions, and traditional hierarchical structures that restrict forms of challenge (Edmondson & Besieux, Citation2021). The benefits of voicing a concern are patient safety and protecting a colleague from making an error (Szymczak, Citation2016). Speaker centric research has identified the communication needs of the speaker, but this knowledge now needs to be extended through an understanding of the receiver’s needs and what drives the receiver’s communication behavior choices.

Background

Recently researchers have begun exploring the receiver’s perspective in speaking up interactions within both experimental and clinical contexts (Krenz et al., Citation2019; Lemke et al., Citation2021; Long et al., Citation2020). Lemke et al. (Citation2021) observed 13 receivers’ affect (demonstration of interest, validation, or defensiveness), and verbal responses (short approval, elaboration, or rejection of the concern) when spoken up to. Lemke et al. also identified that speaking up is not unidirectional up the hierarchy, despite the common belief where it is often defined as “voice behavior toward the supervisor”, or “challenging authority” (Sayre et al., Citation2012, p. 458). Long et al. (Citation2020) studied the behavior of receivers within the wider perioperative environment and identified three phases in the speaking up interaction: the act of speaking up (content and manner), receiver filters, and potential impacts of the receiver’s response (on the team and on patient care). They identified several filters participants reported, including their own state of mind, professional norms, and their own fallibility. These recent receiver focused studies represent important contributions to understanding the receiver’s role, but stopped short of exploring how a receiver perceived the interaction and their subsequent rationale motivations and behavioral choices. In addition, Long et al. and Lemke et al.’s studies did not adopt a theoretical perspective, so their findings do not predict and explain contexts outside of the perioperative environment.

A further limitation is that speaking up research in health has been nursing and physician centric, with very few researchers studying speaking up interactions within allied health disciplines (e.g., Friary et al., Citation2021). In this study, allied health personnel came from physiotherapy, social work, occupational therapy, speech pathology, and radiography. Understanding the perspectives of other disciplines within these often-challenging encounters is essential to help enhance interprofessional communication and patient safety. Our study addresses all three of the identified gaps in the literature. We used Communication Accommodation Theory (CAT: Giles, Citation2016) to understand the behavior of receivers and the impact that the speaker’s communication choices have on the receiver.

Application of theory

We applied CAT to examine the perceptions and self-reported behavior of receivers within speaking up interactions. CAT is an intergroup-centered theory of communication, that explains verbal and nonverbal communicative adjustments within an interpersonal interaction (Giles, Citation2007, Citation2016). CAT unpacks how communication behavior and adjustments can differ according to the context of the conversation and in relation to an individual’s communication motives and goals. It applies Social Identity Theory (Tajfel, Citation1974), which recognizes the importance and salience of a person’s social or professional identity in an interaction. Key social identities in healthcare are the person’s profession/discipline (e.g., nurse, physiotherapist), their seniority level (e.g., graduate nurse, nurse unit manager) and their department (e.g., operating theaters, inpatient ward). Each professional group develops unique attributes, perspectives, values, or worldviews that inform how they approach situations and conversations (Mitchell & Boyle, Citation2015). When a group membership is salient within an interaction, individuals are perceived and judged according to their salient group membership, rather than their individual characteristics (Setchell et al., Citation2015). This difference between groups is referred to as the “social distance” between interactants.

Within conversations, this social distance can be reduced or increased depending on how each speaker perceives the other. Perceptions can be based on past interactions, group membership, or behavior within the current interaction. Communication is deemed to be accommodative if the behavior is perceived as trying to reduce the social distance (increase similarity) between individuals from two differing groups, for example “I saw you coming to see the patient without washing your hands, and I know washing hands is really important for infection control. How do you see it?.” Those in lower status positions, such as a junior clinician, tend to accommodate more to those with higher status such as a senior physician (Gallois et al., Citation2005), for fear of repercussions or retribution (Edmondson & Besieux, Citation2021). Nonaccommodative behavior refers to where little or no effort has been made to reduce the social distance, or differences are exacerbated or maintained, “You need to go back out of the room now and wash your hands.” Counter-accommodative behavior refers to hostile communication behavior that increases social distance. Behavior then can become discriminatory and harmful (Hogg & Terry, Citation2000), “What are you doing?! How could you not know that is wrong?!”

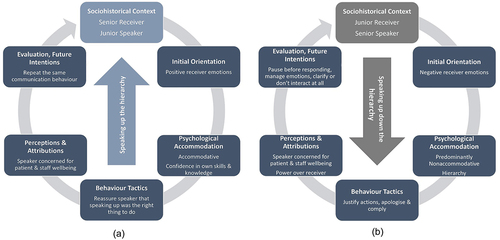

The CAT model explains an entire conversational interaction, which consists of three phases (see ). Phase one, the Initial orientation, describes the goals and beliefs each person brings to the interaction, based on their group memberships and prior experiences and/or interactions (Gallois et al., Citation2005). The Immediate Interaction (Phase two) represents the actual interaction and the accommodative or nonaccommodative communication behaviors of each person. The immediate interaction also includes the attributions that individuals make about the other. These perceptions and attributions in turn influence each person’s overall evaluation of the interaction. Evaluations made of the interaction then, in turn, influence future interactions, which is the third and final phase of the model, Evaluation and Future Intentions (Gallois et al., Citation2005).

Figure 1. Alignment of study survey questions to CAT model (CAT model from: Gallois et al., Citation2005).

The healthcare environment is highly intergroup, with strong traditional hierarchies between both seniority levels and health professions (Rogers et al., Citation2020). The lack of standardization of communication frameworks across health professions (Foronda et al., Citation2016), paired with differing power dynamics between professions, can have an negative impact on communication and, in turn, patient health outcomes (World Health Organisation, Citation2019). CAT is an ideal theory to apply in the speaking up healthcare context. As an intergroup theory, CAT provides an understanding and explanation about how individuals and groups behave within these challenging interactions. The theory acknowledges both the speaker and receiver equally within an interaction, something which is currently lacking in healthcare speaking up.

Methods

We examined receivers’ descriptions of a real speaking up interaction. We used a qualitative approach to investigate different aspects of a self-reported speaking up interaction. Our aim was to understand in a real health context, what a receiver reported hearing influenced how they heard the message, their reported subsequent behavior, including their motivation and justification, and how they reported that the interaction would influence their behavior in future speaking up interactions.

Aims

To address the aim of understanding receiver behavior in a real health context, we posed two research questions: RQ1: How does the speaker influence a receiver’s evaluation of a speaking up interaction? RQ2: How does receiver’s profession influence evaluations of a speaking up interaction?

Design

We used an inductive qualitative design to examine complete speaking up interactions, using the phases of the CAT model, to understand the social reality of the receiver when being spoken up to (Varpio et al., Citation2020). Applying this inductive analysis approach allowed us to identify patterns of meaning within the data (Braun & Clarke, Citation2013).

Participants

Participants were recruited via a convenience sample. This was chosen to obtain a sufficient sample size to understand receiver behavior when receiving a speaking up message from different professions or seniority levels. Participants were eligible for inclusion if they were over 18 years of age and a qualified health professional of any clinical profession employed within the organization. Owing to the diversity of clinical professions, participants were categorized into three receiver groups: Nurses/Midwives (NM), Allied Health (AH) and, Physicians, referred to as Medical Officers (MO). According to Braun and Clarke (Citation2013, p. 50) a sample size between 15–50 is sufficient data for a small qualitative study using participant generated textual data. A sample size of 45 was targeted (15 participants in each receiver group). Refer to for participant characteristics.

Table 1. Participant characteristics.

Data collection

Data collection occurred within a large Australian metropolitan tertiary health organization (800 beds) providing both public and private health care services. Participants were recruited over a 4-month period between November 2019 and March 2020. Participants shared a story of an incident that occurred within the last 6 months, where they received a speaking up message in clinical practice. The term speaking up was defined in the participant instructions. Participants described their stories through short answer responses and responded to 12 questions about the incident (see ). The questions reflected the three phases of the CAT model (Gallois et al., Citation2005, p. 135).

Table 2. Survey questions in full.

We developed a short answer electronic survey using Qualtrics, [Version 2019] (Qualtrics, Citation2023) so the survey could be completed in a shorter time frame and was more flexible for time poor clinicians than interviews. Participants were recruited via an e-mail, which included the survey link, sent by the relevant clinical directors on behalf of the research team. A follow-up reminder was emailed after 2 weeks. The survey link was also placed in the physician monthly newsletter to recruit physicians. All responses were automatically anonymized by the survey software program, ensuring participant confidentiality. The survey included a participant information sheet and consent form. Participants could not start the survey without actively consenting to participate. On average it took participants 25.75 minutes to complete the survey.

Ethical considerations

The study had ethics approval from the health organization’s Research Human Research and Ethics Committee HREC/18/MHS/78 and received ratification from the university’s ethics committee.

Data analysis

We followed COREQ guidelines (Booth et al., Citation2014). Qualtrics was used as it automatically anonymized all participant responses. Any identifiable data in the written responses such as names of the speaker/receiver, were removed by first author (MB) prior to analysis. Researcher MB read through all responses four times to ensure familiarization with the data. Each phase of the CAT model was analyzed separately. The data were analyzed by authors from two different professions (nursing and psychology) to maintain an open dialogue and discussion. Coding began by the coders (MB, BW:CAT expert) independently coding the speaker’s stance, that is, evaluating the speaker’s behavior when delivering the message as accommodative (accommodative stance) or nonaccommodative (nonaccommodative stance). This was required to understand the influence of speaker stance on the receiver, and to see how the initial evaluation of the message influenced the receiver’s overall evaluation of the interaction. The two coders met to discuss and reach consensus. A third coder and author (EJ: psychologist and CAT expert) cross-checked the coding of speaker stance. After final consensus, we created a data collection sheet to thematically code the receivers’ stories across the phases of the CAT model and for speaker stance. Coders conversed regularly to reach mutual agreement. All meetings were video recorded as part of the reflexive journaling process.

Results

Because not all directors sent the e-mail with the survey link to their clinician team, it is unknown how many people received the survey. A total of 103 people completed the online consent form, but only a third of those (n = 33) went on to complete the survey. A further four surveys were removed from the analysis; two due to incomplete responses, and two because they were speaking up stories from the perspective of the speaker, not the receiver. Total participant numbers were n = 29, resulting in a survey completion rate of consented participants of 28%. There were more interactions describing accommodative speaker behavior (17), than nonaccommodative (8) or counter-accommodative (4). presents the characteristics of the speakers and receivers according to discipline and seniority levels.

Table 3. Characteristics of the described speaking up interaction as defined by group membership of the speaker and receiver (n = 29).

Phase 1

Initial orientation

Four stories between different professions (profession outgroup) were reported. Twenty-five (86%) of receivers described conversations within the same professional group (profession ingroup), but with speakers of differing seniority levels. In the initial orientation phase, it was clear that within profession and speaker seniority were key influencing factors for receivers.

The majority of speaking up stories shared by receivers were delivered down the hierarchy, that is, the receiver was more junior than the person speaking up, “The fact that they are my manager provides them with the power to put me under supervisory order” [P7:NM]. Irrespective of how the message was delivered, when spoken up to by a senior clinician, receivers reported feeling self-doubt in their skills and knowledge, “Made me feel I didn’t know what I was doing” [P15:NM]. Participants described a fear of being evaluated as an incompetent clinician or described a loss of confidence in their ability, “I felt upset and now question my confidence and ability” [P16:NM]. There was a frequently mentioned belief that “my voice is not valued” [P1:NM] and receivers described the need for obedience, that is, following orders of a more senior speaker without question, “She was my TL [team leader], so I did what I was told” [P11:NM], and “talking up to your manager makes you feel at times as if you are speaking back to them, which is disrespectful” [P7:NM]. Receivers also described having concerns about the legitimacy of the speaker; they doubted the speaker had legitimate positional authority, but still perceived the speaker as more senior, which influenced the receiver’s behavior, “I felt interrogated, and I knew he had no right to do this as the issue was outside his role scope” [P19:AH]. Even when the speaker was more junior, receivers commented on how their reaction would have potentially been different had the speaker been more senior; “It may have been more confronting if the person had been a senior or leader, more embarrassing” [P21:AH]. There was one exception. One receiver positively described the senior speaker when the stance was accommodative, due to the speaker being “very open and the wording … came across as very approachable” [P18:NM].

Eight participants described interactions that were speaking up messages delivered up the hierarchy (more junior speaker), with the majority reported by allied health participants. Receivers described positive reactions and emotions when a more junior speaker spoke up to them, “grateful,” “impressed,” and evaluated the speaker as accommodative, “I was very grateful to them for prompting me” [P22:AH]. Receivers, when spoken up to by an accommodative junior, described having confidence in their own capability, rather than a concern for their professional reputation or competence level. These receivers described having confidence in their own skills, knowledge, and clinical abilities, which allowed them to actively engage in the interaction rather than become defensive, “I felt confident in my role” [P24:AH]. Overall, more positive reactions and emotions were described by senior receivers when a more junior clinician spoke up, with all interactions evaluated as accommodative, “I was impressed that they felt they were able to address the issue with me despite me being more senior” [P2:NM], and “I was surprised and pleased that he had the courage to say that as it is not often that an RMO [Resident Medical Officer] will speak up to a Consultant [senior physician] in a public setting like this [operating theater]” [P5:MO].

Of the four peer to peer interactions, one receiver described how they had negative emotions, and the interaction was counter-accommodative, “insulted, unrespected [sic] and embarrassed” [P8: NM]. For the remaining peer interactions, receivers described having positive reactions and emotions, and all were evaluated as accommodative, “I was thankful that it was brought up” [P21:AH].

Phase 2

Psychological accommodation: speaker stance

Speaker stance had a substantial influence on the immediate and the overall evaluation of the interaction, including whether receivers described successfully achieving a resolution (a decision on how to move forward), and reaching mutual agreement (the resolution was agreed to by both speaker and receiver). Accommodative stance positively influenced receiver response “He said it very respectfully, so I didn’t get defensive” [P5:MO]. In fact, across participants (receivers), speaking up interactions that were perceived in the immediate interaction (at the start of the conversation) as accommodative, were also described overall as accommodative at the conclusion of the interaction. Importantly, all were described as having achieved a mutually agreed resolution, where interactants had a shared approach to resolving the concern “I do believe it went well, thorough discussion about the situation. Clarified through discussion, suggested an ERIC [incident report] and reported to the Nurse Unit Manager” [P3:NM]. This was not the case when the initial interaction was perceived as nonaccommodative or counter-accommodative, “I felt the verbal attack on myself to be unprovoked, unprofessional and the only way the situation could be improved would be disciplinary actions toward the staff member’s [speaker] behavior” [P8:NM].

In the counter-accommodative interactions receivers described the achievement of a resolution, however, in each occurrence, this was achieved by the receiver agreeing with the speaker’s request to help close the interaction. In addition, all these interactions involved a more senior person speaking up. The combination of the power differentials and perceived poor speaker behavior, equally contributed to receivers describing the sense of powerlessness to disagree and/or engage in the conversation “I was just surprised at her tone, she seemed flustered, and she was my team leader, so I did what I was told” [P11:NM]. This reaction resulted in the receiver reporting strong negative emotions, and in this example resulted in direct patient harm “I should have said no, then my patient would not have fell” [P11:NM]. All more junior speaker conversations were evaluated as accommodative and were mutually resolved.

Communication goals and behaviour tactics

Commonly described goals and tactics, regardless of the stance or seniority of the speaker, were to justify their actions, “Justify my actions, why I didn’t complete the task as requested” [P13:NM], “I wanted them to be aware that I thought I was following the correct procedure” [P18:AH], and to find a resolution “[I wanted to achieve] a solution to the problem” [P25:AH]. Receivers wanted to reassure the speaker that the error was not intentional, “[I] explained I’m really sorry, I didn’t realize. I thought I was doing the right thing by disconnecting the line” [P17:NM], and to admit to being in the wrong, “I acknowledged my behavior was not professional” [P10:NM]. One junior receiver, where the speaker used a nonaccommodative stance, was motivated to build a positive relationship with the speaker, who was both from another profession and more senior, “I wanted to try to gain respect and rapport” [P27:AH].

Within the CAT model, it is here, when describing the behavior tactics, that receivers started to differ between clinical professions. When looking at receiver tactics, a common tactic reported by more junior nurse/midwife receivers was to explicitly apologize. This tactic was unique to this receiver group, “I said sorry to the more senior nurse” [P14:NM]. More explicitly, when the stance was nonaccommodative or counter-accommodative, the apology, paired with verbalizing a justification of their actions, appeared to be used as a tactic to assist the receiver to disengage from, or shut down the conversation, “I just wanted to get them to end the phone conversation quickly … I didn’t have the confidence to speak up to her at that time” [P7:NM]. However, the behavioral tactic of saying thank you was only reported by nurses/midwives when the speaker was more senior to them. Allied health personnel only reported saying thank you when the speaker was more junior or a peer, “I thanked them for speaking up, acknowledging what they did was helpful” [P21:AH].

The senior receivers who positively evaluated a junior speaking up went on to share that their underlying goal was to impart skills and knowledge. They wanted to reassure the more junior speaker, to ensure the speaker felt heard by seeking their perspective, and to achieve a shared understanding, “[I wanted to] thank them for speaking up and acknowledging that what they did was helpful and shouldn’t have been detrimental to them for speaking up” [P21:AH], and “I wanted to reassure him that the patient was safe and that his concerns were heard” [P5:MO]. These receivers portrayed an awareness of their more senior position and described valuing the speaker’s concern and wanting to encourage the more junior clinician to engage in the conversation.

One nurse/midwifery receiver explained that the behavior they deployed was intentionally divergent to that of the speaker, that is, they intentionally slowed down their rate of speech and volume to help manage a nonaccommodative situation. Although this behavior was divergent to the speaker’s behavior, it can be seen as accommodative because the receiver described that their goal was to enhance the interaction, to help reduce the perceived aggression being displayed by the speaker.

Perceptions and attributions

Participants mentioned both positive and negative attributions for the speaker’s intentions in speaking up. The most frequently reported positive attribution for speaking up was patient and/or staff wellbeing, irrespective of speaker stance, “I think they wanted me to be safe” [P17:NM], and “their motivation was to be the voice for the patient [P24:AH].

Negative attributions about the speaker’s intentions occurred most frequently when the speaker’s stance was nonaccommodative or counter-accommodative, and the speaker was more senior. Receivers attributed the speaker’s intention as to have power over the receiver and to ensure the receiver knew they were of lower status, “I believe they wanted me to know my role within the team and not overstep boundaries in future” [P7:NM], and “I honestly feel like they wanted to exceed power over me and they wanted to feel like they knew more than me/were better than me at this job” [P19:AH].

Phase 3

Future intentions

When the whole interaction was evaluated as accommodative, receivers stated they would repeat their described behavior in future interactions, “[I would do] nothing different except encourage them to speak up in the future” [P22:AH], and “I think it was actually a good speaking up moment and there is not much I would do differently” [P2:NM]. When the speaker was more junior, receivers stated they would repeat the same communication behavior, but “I would be more explicit in thanking the person speaking up” [P21:AH]. The physician suggesting “perhaps I could have spent more time in demonstrating to him ovarian palpation and made it more of a teaching moment” [P5:MO].

In nonaccommodative or counter-accommodative interactions, receivers reported they would better manage their own emotions and described the need to pause before responding, “Listen to everything she had to say before I reacted [P12:NM], and “take a breath and ask what was actually wrong” [P4: NM]. Receivers also described future avoidance strategies, such as finishing the conversation quickly, or deferring to another in higher authority, rather than engaging in a meaningful conversation, “Not engage in the conversation as soon as the door closed” [P19:AH]. To summarize, provide a high-level overviews of how receivers, according to seniority, behaved across the reported interactions.

Receiver discipline

There were differences in reactions and responses between the receiver discipline groups across the phases within the reported interactions. Allied health reported more junior speaker encounters, and nurses/midwives reported apologizing more as a behavioral tactic. Nurses/midwives were the only group to have commentary on the presence of other people during the reported interactions, which were only reported when speaker stance was nonaccommodative. When an error was pointed out in front of others, receiver reactions included “embarrassment” and “anger.” It seems nurses/midwives were more concerned about the perceptions of others regarding their competency as a clinician, and this appeared to influence their ability to engage in the conversation.

Overall, the communication goals for nurses/midwives tended to be more receiver-centric, that is, they described more face-saving behaviors, such as needing to justify their actions, apologize, and reassure the speaker that their actions or perceived errors were not intentional. The allied health participants’ goals were more speaker-centric and relational. They also wanted to justify their actions however, their narrative was more about providing reassurance to the speaker that they had done the right thing by speaking up and trying to put the speaker at ease.

Discussion

We examined speaking up interactions from the perspective of the receiver. We sought to understand how the speaker may influence the receiver’s evaluation of the interaction, and if receiver profession influenced these evaluations. We discuss our findings using CAT. We found that in within-profession interactions, speaker hierarchy was an important factor influencing receivers both prior and during the conversation. Within-profession communication interactions are a high frequency event as part of the daily clinical routine. Despite the familiarity, receivers had a strong emotional reaction to being spoken up to by an ingroup senior, in part because they perceived the speaker to be threatening their identity as a competent clinician. From the receiver’s perspective, clinicians who are more junior to their conversational partner are aware of their vulnerability, and, in nursing, confidence in their own clinical abilities and being viewed as competent by others, is key to being accepted into the ingroup (Feltrin et al., Citation2019).

Junior nurses having less than positive responses to speaking up was also highlighted by Long et al. (Citation2020), due to threats to professional identity, and self-esteem. Receiving speaking up messages is therefore not an “emotionally neutral task” (Eva et al., Citation2012, p. 23). Schwappach and Aline (Citation2018) suggested that this is indicative of the culture within specific professional groups. Nurses “eating their young” has been identified as a common term within nursing (Anderson & Morgan, Citation2017). Nurses describing frequent and commonplace experiences of horizontal violence, predominately from aggressive or patronizing intergenerational counter-accommodative behavior. Such group behavior can influence the felt level of psychological safety (Edmonson, Citation1999). Schwappach and Aline found that working environments with lower levels of psychological safety were accompanied by stronger emotional repercussions for those speaking up, influencing both speaking up and withholding voice behavior.

One consideration is that the more senior speakers do not view their comments as speaking up, rather it may be viewed as a provision of feedback, or even instruction. However, the more junior receivers in this study defined these interactions as speaking up occurrences. Not sharing understanding of the type of conversation an interactant is engaged in has been reported as a barrier in feedback conversations (Stone & Heen, Citation2015). It could be this distinction triggered the emotional reactions, as speaking up is often defined as difficult and challenging (Williams et al., Citation2017). To help enhance mutual accommodation in these conversations, it is important that there is clear articulation and understanding about the purpose of the conversation, and what communication goals are in play, for example patient safety, rather than a judgment of clinical competence.

In speaker-centric studies, more junior clinicians often have expressed fear and struggle to speak up the hierarchy, and receivers are often described as wanting to seek retribution, ignore, or silence speakers, leading to nonaccommodative interactions (Fisher & Kiernan, Citation2019; Pattni et al., Citation2019). Unexpectedly, all stories in this study where a more junior person was speaking up elicited positive receiver emotions and responses and were evaluated as accommodative. Why then were senior receivers not triggered by a junior speaking up about an aspect of their care or behavior in the reported occurrences? The more senior receivers in our study described having confidence in their own clinical ability, but importantly this was paired with a sense of humility. This combination seemed to allow the senior receiver to be more receptive to the junior’s message, and for them to attribute the speaker’s intent as saving them and/or the patient from harm. From other applications of CAT in healthcare (Chevalier et al., Citation2017), when the speaker was deemed accommodative, it elicited a sense of openness and reduced the level of uncertainty within an interaction. How the message was delivered, may have also portrayed a sense of respect, helping to reduce the social distance between the two groups. However, we also acknowledge that our finding regarding positive interactions being reported may be the result of social desirability bias. Future researchers should explore what enables receivers to get into a positive receiving mind-set and how receivers can tangibly demonstrate positive receiver behavior.

Speaking up across professional hierarchies (e.g., nurse to physician), is a commonly cited barrier to voice within healthcare (Rogers et al., Citation2020), yet, interestingly, in our study there were very few professional intergroup interactions described, and no accounts where a medical officer was speaking up. From our observational simulation-based study (Barlow et al., Citation2023), nurses/midwives and allied health personnel did not define these conversations as speaking up interactions, rather medical officers were delivering a nonnegotiable order. Physicians may not have this intention, but this is how their behavior is being interpreted based on intergroup norms and stereotypes. Besides hierarchy, this may also be due to how health professionals are taught to communicate. Freeman et al. (Citation2000) described how medical officer communication is underpinned by a directive communication philosophy, as opposed to allied health, who have a more integrative philosophy.

The second research question we posed was what affected the receiver’s overall evaluation of the interaction, and, in turn, potentially influenced their intentions for future similar interactions. In alignment with CAT principles (Gallois et al., Citation2005), participants evaluated the accommodative speaker stance more positively than the nonaccommodative stance. The perceived level of accommodation appeared to have an impact on the assumptions made about the speaker’s intent for speaking up. Gasiorek and Giles (Citation2013) described how the more receivers perceived the speaker’s nonaccommodation to be negatively motivated, the more the receiver would respond nonaccommodatively. This also was true in our findings. Receivers frequently made attributions about the speakers wanting to have power over them in the nonaccommodative and counter-accommodative stories. Receivers reported that this in turn, influenced their intended future behavior.

Receivers described that in future they would not want to engage in a similar conversation or would rapidly shut it down. Particularly concerning was when a senior spoke up in a nonaccommodative, or counter-accommodative manner, many receivers described being complicit to the senior’s request, to conclude the interaction as soon as possible. This may in fact encourage continuing poor speaker behavior, because it reinforces that the speaker is right based on seniority alone, rather than what is right for the situation or patient, reinforcing hierarchical group distinctiveness. Within the speaking up literature, this described behavior is exactly what has been identified as a barrier to speaking up; the receiver not listening or wanting to engage (Edmondson & Besieux, Citation2021). It is therefore important to teach clinicians how to speak up in an accommodative way to enhance message reception. This is not a simple task, as professional identity, as defined by clinical discipline, has shown to influence receiver evaluation of what is an accommodative message and what is not (Barlow et al., Citation2023; Long et al., Citation2020). One size does not fit all.

Implications for practice and research

Consistent with previous receiver based research (Lemke et al., Citation2021), our results demonstrate that speaking up is not unidirectional, as often described (challenging higher authority), but rather moves up, down and across the hierarchical structures. Additionally, we found that when the receiver perceives and judges the speaker to be accommodative, all conversations were mutually resolved, with an agreed forward approach to manage the situation. In the counter-accommodative interactions there was no mutual agreement achieved. In acknowledgment of the multidirectional nature of speaking up, and to enhance accommodation and reduce receiver anxiety, we recommend renaming speaking up to being a “safety negotiation.” Revising the speaking “up” nomenclature, may flatten the hierarchical connotations that was clearly evident in our findings and highlight the equal accountability of the speaker and receiver. This relabeling would aim to help speaking up training programs shift from focusing on just the act of speaking up, to the speaking up interaction.

Secondly, irrespective of how the message was delivered, interactions down the hierarchy evoked significant emotional reactions within the receivers. Martin et al. (Citation2015) found that clinician emotions influenced the quality-of-care provision. Our study builds on this, as we found that emotions also influenced the quality of the conversations and their outcomes. To assist clinicians to manage emotions, and effectively and meaningfully engage in the conversation, requires explicit training. To begin to refocus speaking up being viewed as a negotiation, receivers must be trained how to manage their emotions, as well as how to, in the moment, formulate an accommodative response. This requires speaking up programs placing equal emphasis on the receiver, as they too are a speaker, and requires moving beyond the teaching of speaking up mnemonics.

Although psychology has always understood and applied the two-way dynamic between the speaker and receiver in a communication interaction (Narula, Citation2006), this has not been consistently acknowledged, or tangibly applied within hospital-based communication programs. Our results demonstrated that speaking up is a two-way intergroup interaction (between professions and/or seniority levels). We argue that it is important that communication theories, such as CAT, which acknowledge and address intergroup dynamics, are used, and applied in healthcare communication programs.

Limitations

Our participants were predominately female. Fifty-one percent of clinicians had less than 9 years’ experience which may have contributed to the rate of senior to junior stories shared. The majority of the speaking up occurrences were situated in inpatient ward areas. This does represent a substantial proportion of clinical activity in hospitals, but it also needs to be acknowledged that the team dynamics may differ in critical care or procedural areas. Physician engagement was low in the study. From anecdotal feedback we believe this was due to the type of study (qualitative) and the survey being sent via work e-mails, which meant completion during work hours. Due to the onset of COVID-19 in early 2020, data collection could not be extended.

Conclusion

We used a robust theory of communication to explore what receivers report influences their behavior and their evaluation of a speaking up interaction. The findings highlight that the seniority of the speaker matters, and influences how the receiver initially evaluates speaker stance, which in turn determines the overall evaluation of the interaction. This evaluation impacts receiver behavior within the actual interaction and their intentions for future interactions. With most shared receiver stories being within profession group and down the hierarchy chain, it is time to redefine the phrase speaking up. The design of educational opportunities targeted at senior speakers concerning their impact on more junior receivers, irrespective of stance, is important. In addition, we can better train receivers on deliberate communication strategies and behaviors to manage their emotions and engage in a respectful and meaningful mutual negotiation.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to the clinicians who were generous in sharing their stories

Disclosure statement

This study was part of the author’s doctoral work, which was supported by the Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship. There are no conflicts of interest to declare. Study participants were paid employees of the health organisation in which the study took place and who voluntarily consented to participate.

Data availability statement

All data are reported. The data that support the study findings are available from the corresponding first author, upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Melanie Barlow

Melanie Barlow, RN, MN, PhD(c), is the national Academic Lead for Specialised learning environments and simulation at the Australian Catholic University, Australia. She has a passion for helping to improve healthcare communication and using experiential learning to enhance skills, knowledge, and teamwork.

Bernadette Watson

Bernadette Watson, PhD, is a psychologist and Professor in the area of health communication. She is Honorary Professor at The University of Queensland, Australia, and Adjunct Professor at The Hong Kong Polytechnic University. Her research interests include psychological wellbeing and health, interdisciplinary health professional communication, language and social psychology, and intercultural communication.

Elizabeth Jones

Elizabeth Jones, PhD, is a psychologist and Professor and Head of Department of Psychology at Monash University Malaysia. She is also an adjunct professor at Griffith University, Australia. Her research interests include psychological wellbeing and health, interdisciplinary health professional communication, organisational communication, and intercultural communication.

Catherine Morse

Catherine Morse, PhD, is an advanced practice nurse, the Assistant Dean for Experiential Learning and Innovation, and an Associate Clinical Professor of Nursing at Drexel University, USA. She has expertise in simulation methodology and research, including debriefing, feedback, speaking up, curriculum design.

Fiona Maccallum

Fiona Maccallum, PhD, is a clinical psychologist and lecturer at the University of Queensland, Australia. Her research interests are in grief & loss, trauma, and anxiety. She undertakes experimental and clinical investigations of autobiographical memory, self-identity and future thinking, attachment, emotion regulation, and motivation.

References

- Anderson, L. B., & Morgan, M. (2017). An examination of nurses’ intergenerational communicative experiences in the workplace: Do nurses eat their young? Communication Quarterly, 65(4), 377–401. https://doi.org/10.1080/01463373.2016.1259175

- Barlow, M., Morse, C., Watson, B., & Maccallum, F. (2023). Identification of the barriers and enablers for receiving a speaking up message: A content analysis approach. Advances in Simulation, 8(1), 17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41077-023-00256-1

- Barlow, M., Watson, B., Jones, E., Maccallum, F., & Morse, K. (2023). The influence of professional identity on how the receiver receives and responds to a speaking up message: A cross-sectional study. BMC Nursing, 22(26). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-023-01178-z

- Booth, A., Hannes, K., Harden, A., Noyes, J., Harris, J., & Tong, A. (2014). COREQ (consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative studies). In D. Moher, D. Altman, K. Schulz, I. Simera, & E. Wager (Eds.), Guidelines for reporting health research: A user’s manual (pp. 214–226). https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118715598.ch21

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2013). Successful qualitative research: A practical guide for beginners. Sage.

- Chevalier, B. A. M., Watson, B. M., Barras, M. A., & Cottrell, W. N. (2017). Investigating strategies used by hospital pharmacists to effectively communicate with patients during medication counselling. Health Expectations, 20(5), 1121–1132. https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.12558

- Edmondson, A. C., & Besieux, T. (2021). Reflections: Voice and silence in workplace conversations. Journal of Change Management, 21(3), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/14697017.2021.1928910

- Edmonson, A. (1999). Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44(2), 350. https://doi.org/10.2307/2666999

- Eva, K. W., Armson, H., Holmboe, E., Lockyer, J., Loney, E., Mann, K., & Sargeant, J. (2012). Factors influencing responsiveness to feedback: On the interplay between fear, confidence, and reasoning processes. Advances in Health Science Education Theory Practice, 17(1), 15–26. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-011-9290-7

- Feltrin, C., Newton, J. M., & Willetts, G. (2019). How graduate nurses adapt to individual ward culture: A grounded theory study. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 75(3), 616–627. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.13884

- Fisher, M., & Kiernan, M. (2019). Student nurses’ lived experience of patient safety and raising concerns. Nurse Education Today, 77, 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2019.02.015

- Foronda, C., MacWilliams, B., & McArthur, E. (2016). Interprofessional communication in healthcare: An integrative review. Nurse Education in Practice, 19, 36–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2016.04.005

- Freeman, C., Miller, N., & Ross, M. (2000). The impact of individual philosophies of teamwork on multi-professional practice and the implications for education. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 14(3), 237–247. https://doi.org/10.1080/713678567

- Friary, P., Purdy, S. C., McAllister, L., & Barrow, M. (2021). Voice behavior in healthcare: A scoping review of the study of voice behavior in healthcare workers. Journal of Allied Health, 50(3), 242–260.

- Gallois, C., Ogay, T., & Giles, H. (2005). Communication accommodation theory: A look back and a look ahead. In W. Gudykunst (Ed.), Theorizing about intercultural communication (pp. 121–148). TSage.

- Gasiorek, J., & Giles, H. (2013). Accommodating the interactional dynamics of conflict management. International Journal of Society, Culture & Laguage, 1(1), 10–20.

- Giles, H. (2007). Communication accommodation theory. Wiley Online Library. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781405186407.wbiecc067

- Giles, H. (2016). Communication accommodation theory. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118766804.wbiect056

- Hanson, J., Walsh, S., Mason, M., Wadsworth, D., Framp, A., & Watson, K. (2020). ‘Speaking up for safety’: A graded assertiveness intervention for first year nursing students in preparation for clinical placement: Thematic analysis. Nurse Education Today, 84, 104–252. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2019.104252

- Hogg, M., & Terry, D. (2000). Social identity and self-categorization processes in organizational contexts. The Academy of Management Review, 25(1), 121–140. https://doi.org/10.2307/259266

- Jones, A., Blake, J., Adams, M., Kelly, D., Mannion, R., & Maben, J. (2021). Interventions promoting employee “speaking-up” within healthcare workplaces: A systematic narrative review of the international literature. Health Policy, 125(3), 375–384. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2020.12.016

- Krenz, H. L., Burtscher, M. J., & Kolbe, M. (2019). “Not only hard to make but also hard to take:” team leaders’ reactions to voice. Gruppe Interaktion Organisation Zeitschrift für Angewandte Organisationspsychologie (GIO), 50(1), 3–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11612-019-00448-2

- Lemke, R., Burtscher, M., Seelandt, J., Grande, B., & Kolbe, M. (2021). Associations of form and function of speaking up in anaesthesia: A prospective observational study. British Journal of Anaesthesia, 127(6), 971–980. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bja.2021.08.014

- Long, J., Jowsey, T., Garden, A., Henderson, K., & Weller, J. (2020). The flip side of speaking up: A new model to facilitate positive responses to speaking up in the operating theatre. British Journal of Anaesthesia, 125(6), 1099–1106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bja.2020.08.025

- Lyndon, A., Sexton, J. B., Simpson, K. R., Rosenstein, A., Lee, K. A., & Wachter, R. M. (2012). Predictors of likelihood of speaking up about safety concerns in labour and delivery. BMJ Quality & Safety, 21(9), 791–799. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2010-050211

- Martin, E. B., Mazzola, N. M., Brandano, J., Luff, D., Zurakowski, D., & Meyer, E. C. (2015). Clinicians’ recognition and management of emotions during difficult healthcare conversations. Patient Education and Counseling, 98(10), 1248–1254. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2015.07.031

- Mitchell, R., & Boyle, B. (2015). Professional diversity, identity salience and team innovation: The moderating role of open mindedness norms. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 36(6), 873–894. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2009

- Morrison, E. W. (2014). Employee voice and silence. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 1(1), 173–197. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-031413-091328

- Narula, U. (2006). Communication models. Atlantic Publishers & Dist.

- Noort, M. C., Reader, T. W., & Gillespie, A. (2021). The sounds of safety silence: Interventions and temporal patterns unmute unique safety voice content in speech. Safety Science, 140, 105289. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2021.105289

- Pattni, N., Arzola, C., Malavade, A., Varmani, S., Krimus, L., & Friedman, Z. (2019). Challenging authority and speaking up in the operating room environment: A narrative synthesis. British Journal of Anaesthesia, 122(2), 233–244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bja.2018.10.056

- Qualtrics. (2023). Qualtrics (Version 2019). In https://www.qualtrics.com

- Rogers, L., De Brún, A., Birken, S., Davies, C., & McAuliffe, E. (2020). The micropolitics of implementation; a qualitative study exploring the impact of power, authority, and influence when implementing change in healthcare teams. BMC Health Services Research, 20(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-020-05905-z

- Sayre, M. M., McNeese-Smith, D., Phillips, L. R., & Leach, L. S. (2012). A strategy to improve nurses speaking up and collaborating for patient safety. JONA: The Journal of Nursing Administration, 42(10), 458–460. https://doi.org/10.1097/NNA.0b013e31826a1e8a

- Schwappach, D., & Aline, R. (2018). Speak up-related climate and its association with healthcare workers’ speaking up and withholding voice behaviours: A cross-sectional survey in Switzerland. BMJ Quality & Safety, 27(10), 827. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2017-007388

- Setchell, J., Leach, L. E., Watson, B. M., & Hewett, D. G. (2015). Impact of identity on support for new roles in health care: A language inquiry of doctors’ commentary. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 34(6), 672–686. https://doi.org/10.1177/0261927X15586793

- Stone, D., & Heen, S. (2015). Thanks for the feedback: The science and art of receiving feedback well. Penguin Books.

- Szymczak, J. (2016). Infections and interaction rituals in the organisation: Clinician accounts of speaking up or remaining silent in the face of threats to patient safety. Sociology of Health and Illnes, 38(2), 325–339. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9566.12371

- Tajfel, H. (1974). Social identity and intergroup behavior. Social Science Information, 13(2), 65–93. https://doi.org/10.1177/053901847401300204

- Varpio, L., Paradis, E., Uijtdehaage, S., & Young, M. (2020). The distinctions between theory, theoretical framework, and conceptual framework. Academic Medicine, 95(7), 989–994. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000003075

- Williams, B., Beovich, B., Flemming, G., Donovan, G., & Patrick, I. (2017). Exploration of difficult conversations among Australian paramedics. Nursing & Health Sciences, 19(3), 358–365. https://doi.org/10.1111/nhs.12354

- World Health Organisation. (2019). WHO Calls for Urgent Action to Reduce Patient Harm in Healthcare. WHO. Retrieved May 10, from https://www.who.int/news/item/13-09-2019-who-calls-for-urgent-action-to-reduce-patient-harm-in-healthcare