ABSTRACT

Interprofessional collaboration is vital in the context of service delivery for children with physical disabilities. Despite the established importance of interprofessional collaboration and an increasing focus on research on this topic, there is no overview of the research. A scoping review was conducted to explore current knowledge on interprofessional collaboration for children with physical disabilities from the point of view of the actors involved. The steps of this review included identifying a research question, developing a protocol, identifying relevant research, selecting studies, summarizing and analyzing the data, and reporting and discussing the results. Through databases and studies from hand-searches, 4,688 records were screened. A total of 29 studies were included. We found that four themes: communication, knowledge, roles, and culture in interprofessional collaboration illustrate current knowledge on the topic. Interprofessional collaboration for children with physical disabilities is shown to be composed of these four themes, depending on the actors involved. Interprofessional collaboration is affected by how these four themes appear; they mainly act as barriers and, to a lesser extent, as facilitators for interprofessional collaboration. Whether and how the themes appear as facilitators need further exploration to support innovation of interprofessional collaboration.

Introduction

Interprofessional collaboration is vital in providing well-functioning healthcare across services. The World Health Organization (WHO) recognizes the importance of interprofessional collaboration as key to ensure optimal patient outcomes and safety through better team coordination and communication (WHO, Citation2010). Interprofessional collaboration is an “active and ongoing partnership, often between people from diverse backgrounds with distinctive professional cultures and possibly representing different organizations or sectors, who work together to solve problems or provide services” (Morgan et al., Citation2015, p. 1218). Interprofessional collaboration includes regular interaction and negotiation between professionals, professionals and users, and professionals and the next of kin, valuing each of the various actors’ contribution and expertise (Edwards, Citation2012, Citation2017).

Children with physical disabilities receive a variety of child- and family-directed services, and often they have to relate to several different professional contacts (Kalleson et al., Citation2021). On the other hand, healthcare, social care, and education professionals providing the services must also relate to the child in question, the child’s family, and the other service providers. Interprofessional collaboration is vital in the context of service delivery for children with physical disabilities (Norwegian Directorate of Health, Citation2022). However, based on the national or regional context, agencies and professionals may have somewhat autonomous positions, with collaboration usually carried out on an ad hoc basis (Norwegian Directorate of Health, Citation2022). It is common knowledge that different stakeholders do not necessarily understand collaboration in the same way (D’Amour et al., Citation2005).

Interprofessional collaboration has the potential to enhance professional practice, patients’ quality of life, improvement in utilizing medication, care outcomes, and patient satisfaction (Carron et al., Citation2021; Reeves et al., Citation2017). To facilitate interprofessional collaboration at the team level, informal face-to-face meetings, collaboration involving equal responsibilities, and communication in the planning and execution of the work are recognized as central factors (Fukkink & Lalihatu, Citation2020).

Even with existing knowledge emphasizing the possible positive outcomes of interprofessional collaboration, implementation of the practice of interprofessional collaboration is complex (Pullon et al., Citation2016; Reeves et al., Citation2017). The complexity is partly because actual paradigms of collaboration at the institutional and child level may differ between parties, even though guidelines at the national level are clear (Nijhuis et al., Citation2007). At the team level, a challenging context is that different professionals have fundamentally different relationships with children and their parents. Some professionals may have long-term relationships with families and often meet on a daily basis, whereas others may have less contact and less frequent meetings (Fukkink & Lalihatu, Citation2020).

Children with disabilities are enrolled into a healthcare system due to their disabilities. Professionals enter the child’s life at an early age and collaborate with the child and the family through childhood. The circumstance of the children varies and, throughout their growth, their needs might change. Children with disabilities live their everyday lives at home, at nursery, or at school with their peers and family, which mirrors the need for collaboration across services. Regardless of the type of home or educational setting, parents are likely to experience frequent interactions with health and education staff. Additionally, they must negotiate the complex relationship that exists between both sets of agencies (Ryan & Quinlan, Citation2018). When healthcare – or other services – are provided in an ad hoc manner, with different criteria for who receives support, care is often fragmented. To efficiently promote child development, learning, and well-being among children with disabilities, collaboration across organizational boundaries is necessary (Kalleson et al., Citation2021; Norwegian Directorate of Health, Citation2022; World Health Organization, Citation2008).

Researchers have documented the importance of practicing interprofessional collaboration (Carron et al., Citation2021; Didier et al., Citation2020). Further, there is a growing body of evidence on factors that promote and hamper collaboration (Fukkink & Lalihatu, Citation2020; Nijhuis et al., Citation2007). Although interprofessional collaboration has been on the agenda for decades and there is a growing knowledge base concerning interprofessional collaboration for children with physical disabilities, no overview of the evidence has been conducted.

In this scoping review, our starting point was the perspectives of the actors involved. The aim of this study is to provide an overview of the current extent of knowledge concerning interprofessional collaboration for children with physical disabilities from the point of view of the actors involved. We also identify evidence gaps in the research literature. The following review questions are addressed:

What is the current extent of knowledge on interprofessional collaboration for children with physical disabilities from the point of view of the actors involved?

What characterizes (context, methodological approach, data collection, voices heard) the research on interprofessional collaboration for children with physical disabilities?

Method

Research design

A scoping review is a rigorous transparent method for mapping the knowledge base, along with summarizing and disseminating the results to inform practitioners, users, policymakers, and researchers (Arksey & O’Malley, Citation2005). We used the frameworks designed by Arksey and O’Malley (Citation2005) and by the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) for scoping reviews as the guidelines for conducting the scoping review (Peters et al., Citation2020). The steps of this review involved identifying a research question, developing a protocol, identifying relevant research, selecting studies, summarizing and analyzing the data, and reporting and discussing the results. The initial protocol can be found here: https://osf.io/bm4t7/?view_only=1675b48740cc41cda63527784c441445. As it was developed prior to conducting the review, the process was iterative, allowing for refinement as the review progressed.

Identifying relevant studies

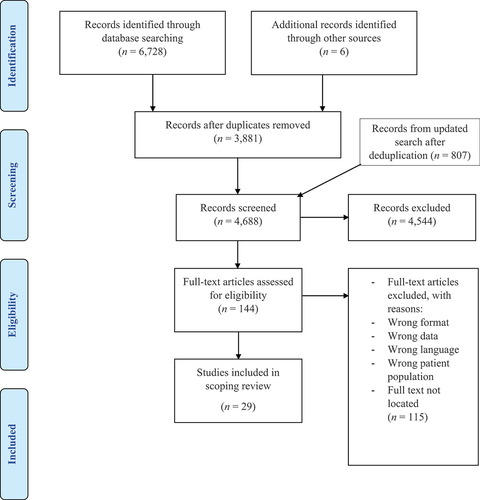

The review team consisted of five scholars as reviewers (LMS, SH, KSG, MIH, and TDM) and two university librarians. Five reviewers identified a research question and developed a protocol. The search strategy was developed, adjusted, and refined in collaboration between two of the reviewers (LMS and TDM) and librarians. A third librarian assessed the quality of the search strategy through peer review. The search strategy was linked to MeSH terms and words relating to the concepts “interprofessional collaboration” and “children with physical disabilities.” We applied a wide range of terms to ensure the identification of available evidence on the topic. For example, the search was designed to ensure that the use of the word “team” included an interprofessional dimension. The search strategy was initially developed and piloted for Medline. Keywords and index terms were adapted for each included database based on piloting work: Medline, CINAHL, ERIC, Embase, Cochrane Library, PsychInfo, Applied Social Science Index & Abstracts (ASSIA), SocIndex, and Scopus. The original search was limited to studies published between 2000 and first half of December 2021 in English or in a Scandinavian language. The chosen time frame captures the increased emphasis on collaborative practices to support children with disabilities and their families over the past several decades. Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed-method studies were all considered. The search was carried out between November – December 2021 by librarians. Online Supplement A includes the complete search strategy used for Medline. All 3,875 studies, after deduplication, were uploaded to Covidence, a workflow platform to manage the review process. Additionally, six studies from hand-searches were added. An updated search was conducted on the 11 August 2023. The search was limited to studies published 2021 to 11 August 2023 and resulted in 807 studies after deduplication. In total, 4,688 studies were screened.

Study selection

Our screening processes were blinded, since all studies were reviewed by two or more reviewers. The entire screening process was guided by the inclusion and exclusion criteria found in . The inclusion criteria concerning children between the ages of 2–18 included studies where the children were already in or entering childcare settings like nurseries. Interprofessional collaboration meant the studies did not only concern a one-on-one professional – parent partnership. The studies included had to contain primary data of the actors involved in the collaboration. One reviewer reviewed all studies to ensure reliability. A pilot screening of 200 titles and abstracts led to an adjustment and refinement of the inclusion and exclusion criteria. When agreement on screening conflicts was not reached, which occurred in four studies during full-text screening, a third reviewer was involved to reach consensus. One hundred forty-four studies were eligible for full-text screening, and the same review procedure was applied here as with the title and abstract screening. Of the 144 studies eligible for full-text review, 29 studies were included for the analysis. , Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement (Moher et al., Citation2009), outlines the record of the screening process.

Table 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Summarizing and analyzing the data

After screening of the studies, we moved onto the next step, which was summarizing and analyzing the data in the 29 studies included for analysis. Two reviewers conducted this process (LMS and TDM), while the three other reviewers (SH, KSG, and MIH) contributed through feedback sessions. Informed by guidelines created by Arksey and O’Malley (Citation2005) and the JBI methodology for scoping reviews (Peters et al., Citation2020), summarizing and analyzing the data began with extracting and tabulating descriptive data relevant to the review questions from each included study (Arksey & O’Malley, Citation2005; Peters et al., Citation2020). This included authors, year of publication, title, country, context, stated aim, participants, methodological approach, data collection, and main findings as outlined by the authors. Next, we performed a more thorough extraction of the main results and stated knowledge gaps as outlined by the authors, which also included authors, year of publication, title, and actors involved; see Online supplement B.

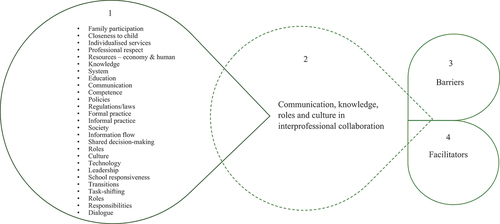

To analyze the data, Arksey and O’Malley (Citation2005) suggested using an analytical framework or thematic construction to grasp the main results. Our interpretation of the data was thereby informed by a thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). Our thematic analysis included exploring for common concepts and themes in the material over several rounds before commonalities were collated, refined, and summarized. In the final stage of our analysis, we looked for cross-cutting themes across the results in the included studies (see ).

Results

Study characteristics

A summary of the 29 studies included in this review can be found in . Twenty-one studies were qualitative studies, four studies were quantitative, and four studies utilized a mixed-method design. Studies were conducted in the following regions: nine in other western countries, eight in the Nordics, eight in North America, four in Oceania, and one in South Africa. The studies encompassed the voices of the various actors: 23 involved professionals, 14 involved parents or other family members, and four involved children/youth/young people. Regarding the contexts, 14 studies took place in a municipality and community setting. Thirteen studies were related to the context of specialized health services, while two studies related to educational settings. Of the 14 studies connected to municipality and community settings, over half concerned issues that involved or had education as their starting point. Concerning the years of publication, 24 of the studies were published in or after 2010.

Table 2. Summary of studies included in the scoping review.

Themes

The four themes identified through our thematic analysis were communication, knowledge, roles, and culture in interprofessional collaboration; see . These four themes were identified through our initial analysis, which involved capturing the main results on interprofessional collaboration for children with physical disabilities from the point of view of the actors involved. These four themes are prominent in the current knowledge base. The themes also help in pointing out research areas that need further exploration. Each theme is presented separately in the results section. Barriers and facilitators, found as cross-cutting themes in the final stage of the analysis, are outlined in the discussion section.

Communication in interprofessional collaboration

The most evident theme included in the vast majority of the studies (26 of 29), was communication in interprofessional collaboration. This theme related to situations where individuals communicated with each other or reacted to each other’s practices and how the interplay between the various arenas and contextual factors, like policies, affected the interprofessional collaboration.

In interprofessional collaboration, communication between the individuals was sometimes challenged (Goodwin et al., Citation2019; Gulmans et al., Citation2009; Jeglinsky et al., Citation2012; McKinnon et al., Citation2021; Nijhuis et al., Citation2007; Reeder & Morris, Citation2021; Skagestad et al., Citation2021). In some situations, hierarchies appeared when health professionals devalued parents’ knowledge as less specialized and did not follow up on parents’ knowledge as shared knowledge (Reeder & Morris, Citation2021). Parents’ perspectives included how disparities in communication between them and professionals are mainly related to lack of collaboration and patient-centeredness (Gulmans et al., Citation2009). Interprofessional collaboration affected by such deficiencies in the communication involved less inclusiveness, less shared decision-making, and the lack of a relational approach (Reeder & Morris, Citation2021; Skagestad et al., Citation2021). Additionally, parents’ relationship with professionals was affected by the communication between them. To some extent parents wanted to have and maintain a good relationship with professionals, but they also found it important to speak up and make sure the professionals did what was anticipated from them (Cameron, Citation2018). It was not a desire among parents to create or enter interprofessional disputes. Nevertheless, they recognized the importance of having well-functioning communication with the team members to cope with the everyday life having a child with a disability (Cameron, Citation2018). Even in settings with balanced communication, a change of professionals was to some degree recognized as good among parents, as it led to new perspectives entering the collaboration (James & Chard, Citation2010). Psychosocial challenges such as transport barriers and financial constraints, among service receivers also appeared to inhibit the communication between the actors involved in the interprofessional collaboration (Ngubane & Chetty, Citation2017).

In some interprofessional collaboration settings, the professionals perceived the communication between professionals to mainly occur when involved in a program, just relating to greetings during visits, or when asking for a report concerning the child’s activities (Gmmash et al., Citation2020; Weglarz-Ward et al., Citation2020). With limited communication between the team members, the communication between professionals and between professionals and the family might be tainted by contractionary recommendations (Gmmash et al., Citation2020). Some prerequisites to achieve good communication between the individuals in the collaboration included prioritizing getting to know each other, inclusion of all participants, clear and open dialogue, mutual trust and respect for contributions and views of others, and regular and close informal and formal contact between team members (Cameron & Tveit, Citation2019; Mukherjee et al., Citation2002; Skagestad et al., Citation2021; Ziviani et al., Citation2013).

Communication in interprofessional collaboration was also affected by organization of the services and a lack of procedures and polices (Cameron, Citation2018; Fellin et al., Citation2015; Gmmash et al., Citation2020; Gulmans et al., Citation2009, Citation2012; Larsson, Citation2000; Lindsay et al., Citation2018; Rosendahl et al., Citation2021). An example of this is communication related to knowledge transfer to communities from hospitals concerning follow-up on rehabilitation programs, necessary devices, and coping after surgery (Capjon & Bjørk, Citation2010). Non-seamless systems can be connected to lacking formal procedures and policies, such that relevant institutions are prevented from communicating during interprofessional collaboration (Lindsay et al., Citation2018; Weglarz-Ward et al., Citation2020).

A web-based system for parent – professional and interprofessional communication was suggested by parents to contribute to sufficiency of contact, accessibility of professionals, and timely information exchange (Gulmans et al., Citation2012). Moreover, policies can dictate how providers should act during their workday through service-provision models, administrative work, and eligibility standards. Further, such dictation might hinder communication of knowledge and relational practices (Gmmash et al., Citation2020). Parents reported wanting to influence service evaluation but, when having limited opportunity to do so and not knowing how to get in touch with management, advocacy for changes that might benefit them was poorly undertaken (James & Chard, Citation2010; Pickering & Busse, Citation2010).

Knowledge in interprofessional collaboration

Knowledge in interprofessional collaboration was another evident theme in the material, included in over two-thirds of the studies (23 of 29). This theme is related to the needs and usability of the combination of skills, experience, training, and knowledge within interprofessional collaboration.

Families reported needing more information and education, especially about the rehabilitation process, beneficial aspects of rehabilitation, and the child’s diagnosis and prognosis (James & Chard, Citation2010; Ngubane & Chetty, Citation2017; Nijhuis et al., Citation2007; Reeder & Morris, Citation2021). Educational sessions and practical group work were given by health professionals to families to meet these needs. When families possessed such knowledge, it promoted rehabilitation of the child, fostered a better understanding of the child’s needs and development, and supported family’s ability to cope with the everyday life of a child with a physical disability. Additionally, being knowledgeable was connected to how active families were as participants in collaboration (Ngubane & Chetty, Citation2017; Reeder & Morris, Citation2021). When the information was given, how well the information was grasped and the family’s readiness for information were other aspects of this theme. Even though parents emphasized the need for information and education, they were not necessarily receptive to a lot of information at the stage of entry into services (James & Chard, Citation2010). For example, parents in a collaborative setting may not be able to move beyond the emotional adjustment of having a child with a disability (James & Chard, Citation2010). The parents’ preferred learning styles might also differ. Adaptation of how information was given, taking into consideration the situation and context of the receiver, using other strategies like pictures or videos, might enhance and tailor learning among families (McKinnon et al., Citation2021; Pickering & Busse, Citation2010; Ziviani et al., Citation2013).

Health professionals have been shown to discourage parents from searching for health-related information online, and such a practice is indicated as hindering parents' contribution to the interprofessional collaboration (Reeder & Morris, Citation2021). Parents’ knowledge about their child’s behaviors and needs is considered as both positive and as less important by professionals in interprofessional collaboration (Bourke-Taylor et al., Citation2018; Tragoulia & Strogilos, Citation2013). Access to information for parents concerning their child’s education was also not always self-evident in interprofessional collaboration (Tragoulia & Strogilos, Citation2013).

The actors involved in interprofessional collaboration indicated a necessity for increased knowledge and competence for themselves and others concerning issues like assessment tools, use of aids, education and training of professional development, and information on other professions (Berman et al., Citation2000; Bourke-Taylor et al., Citation2018; Fellin et al., Citation2015; Goodwin et al., Citation2019; Jeglinsky et al., Citation2012; Lindsay et al., Citation2018; Weglarz-Ward et al., Citation2020). Educational staff recognized a need for more competence on how to better meet the educational, physical, social, and self-care needs of pupils with disabilities (Bourke-Taylor et al., Citation2018; Goodwin et al., Citation2019). By taking an active part early on in the interprofessional collaboration, the educational staff could enhance their knowledge through training. This training could be individual teaching sessions with the child’s respective therapists before the child starts school, observation of the child in their current environment, and follow-up sessions with therapists when the child enters school (Bourke-Taylor et al., Citation2018). These training elements were recognized as crucial among childcare providers seeking to enhance their knowledge on children with disabilities (Weglarz-Ward et al., Citation2020). Professionals exposed to other professionals’ knowledge could also better understand the relationship between aspects like position and social interaction for the child (Sylvester et al., Citation2017). In cases where the therapists operated across diverse arenas in the child’s everyday life, transfer of knowledge was conducted with ease. In these cases, the actors involved in the collaboration could also collaborate with more ease for teaching and defining the child’s need and abilities to promote school participation (Bourke-Taylor et al., Citation2018). On the other hand, professionals from early intervention services suggested that being able to embed strategies into daily routines in childcare relied on a childcare provider with predictable routines and professional capacity (Weglarz-Ward et al., Citation2020).

Sharing of information and transfer of knowledge between professionals and institutions was one aspect of the theme (Cameron & Tveit, Citation2019; Mukherjee et al., Citation2002; Weglarz-Ward et al., Citation2020). When health-related information concerning a child with disabilities was to be shared with educational staff, there was a need to be able to deal with patient confidentiality and parental consent. Without systems to guide and support professionals in the transfer and retention of information in these cases, information might reach the wrong hands, due to a lack of knowledge on how to best deal with patient confidentiality. Professionals indicated that having competent systems promoted a good practice of information sharing to secure patient confidentiality in interprofessional collaboration (Mukherjee et al., Citation2002; Weglarz-Ward et al., Citation2020).

Knowledge in interprofessional collaboration is also related to arenas, such as school or nursery, concerning the everyday life of children with disabilities. Nurseries were found to have first-hand knowledge concerning the child’s individual and developmental needs, which was something beyond the knowledge held by professionals from other arenas (Cameron et al., Citation2014). Transferring such knowledge from nurseries to home and health services was indicated to be of great value (Cameron et al., Citation2014). The nurseries’ first-hand knowledge concerning the child was noted as not being directly related to the staff’s more formal expertise. That is, the professionals' educational approaches were not primarily emphasized by those taking part in the collaboration. The knowledge emphasized by the other actors in the collaboration was the exceptional insights that nurseries and the professionals working in nurseries had regarding the children as individuals (Cameron et al., Citation2014).

Roles in interprofessional collaboration

One of the most evident themes in the material, comprising two-thirds of the studies (18 of 29) was roles in interprofessional collaboration. Firstly, the theme refers to the roles that individuals play in interprofessional collaborative settings. Secondly, it refers to the context, like systems, and life-arenas, as well as the explicit impact that these contexts have on interprofessional collaboration. In some settings, certain roles are taken on, whereas in others they are given.

Individual roles were, for example, roles of the cultural broker, coordinator, messenger of information, parent, and understanding each other’s roles. Professionals pointed out how a social worker (SW) in the role of a “cultural broker” communicated the needs of families to other members of the team during the collaboration. Learning about the families’ diverse ethnic backgrounds, contexts, and norms through the SW in such a role supported other professionals when adapting their interventions to match what they were taught (Fellin et al., Citation2015). The role as organizer, where one assists families navigating through agencies and programs, was another role professionals either took on or were given (Fellin et al., Citation2015; Lindsay et al., Citation2018). Understanding each other’s roles was connected to the professionals’ different reasons for entering the collaboration and their previous experiences (Sylvester et al., Citation2017). Grounding in common frameworks could give an understanding of the professionals' agendas and thereby how to interact collaboratively (Sylvester et al., Citation2017). On the other hand, parents and professionals indicated how a lack of understanding of each other’s roles may lead to disruption in the practice of interprofessional collaboration (Cameron, Citation2018; Solomon & Risdon, Citation2014; Weglarz-Ward et al., Citation2020).

Parents in a coordinating role must conduct administrative work like following up on professional tasks, writing applications, and canalizing information between professionals and services (Cameron, Citation2018; Mukherjee et al., Citation2002; Reeder & Morris, Citation2021). Such a parental role was identified as hindering accurate information from reaching the right receiver within the collaborative team and also as being an extra burden for the parents, keeping them from spending time with the whole family (Cameron, Citation2018; Gulmans et al., Citation2012; Mukherjee et al., Citation2002). Although professionals did recognize the burden of a parent being given this role and the destabilizing effect it had on the collaborative setting, the absence of communication platforms seemingly left the professionals with a lack of choices (Gulmans et al., Citation2009, Citation2012; Mukherjee et al., Citation2002). Parents expressed the need for just being in a parental role where, for instance, the coordinating role – with its administrative work – was given or taken by a professional coordinator (Bourke-Taylor et al., Citation2018; Cameron, Citation2018).

Another role that the actors involved considered as conflicting was that of being the coordinator for the individual plan (IP). Such a role was often provided by a professional in the health service, but both health professionals and parents viewed staff at nurseries as well suited for such a role due to their first-hand knowledge regarding the children’s everyday life. Professionals at nurseries claimed that they did not have the resources to perform the task of being the coordinator and also that the administrative work of taking on such a role would take their focus away from the children (Cameron et al., Citation2014).

Moreover, technology, life arenas, policy, and resources had an impact on interprofessional collaboration. Our results show how technology played a role in how interprofessional collaborations were acted out, with the use of a web-based communication system for integrated care in cerebral palsy as one example (Gulmans et al., Citation2012). The technological system was highlighted by the parents as playing a supporting role in the sufficiency of contact, accessibility of professionals, and timely information exchange during collaboration (Gulmans et al., Citation2012). Despite this positive influence of technology, it was noted in the same study that technology had less impact on relieving parents from acting as care coordinators (Gulmans et al., Citation2012).

The nursery was presented as playing a key role in interprofessional collaboration for children with disabilities. Staff in nurseries met the children on a daily basis and, therefore, had first-hand knowledge regarding their everyday life. Such proximity to the child was noted to function as a shared frame of reference between the nursery and the families. Nurseries were also recognized performing a role with willingness and eagerness to move forward with the collaboration by getting other agencies involved (Cameron et al., Citation2014). However, establishing new contacts and deciding who should be involved in the interprofessional collaboration often happened at an administrative level and was influenced by how the role of organizing the services and the structure in the context affect the possibilities of achieving interprofessional collaboration (Cameron & Tveit, Citation2019; Larsson, Citation2000). In some contexts, this could mean a system with a role that was perceived as what parents called bureaucratic, unmanageable, and less user-friendly (Cameron, Citation2018).

Culture in interprofessional collaboration

A less evident theme included in about one-third of the studies (12 of 29), was culture in interprofessional collaboration. We found culture in interprofessional collaboration to be vital to the current knowledge base. Firstly, culture is related to the social behaviors and beliefs of individuals (different professionals, parents) in interprofessional collaboration. Among individuals, these behaviors and beliefs could relate to customs, traditions, norms, habits, faith, and rituals (Gmmash et al., Citation2020; Ngubane & Chetty, Citation2017). Secondly, this theme involved context and systems being recognized by leading policies, norms, habits, and other social factors (Jeglinsky et al., Citation2012; Lindsay et al., Citation2018; Rosendahl et al., Citation2021).

Among the included studies, the families’ cultural background was found to be challenging for service provision (Fellin et al., Citation2015; Gmmash et al., Citation2020; Ngubane & Chetty, Citation2017; Ziviani et al., Citation2013). One aspect related to education of the families. That is, when families were holding on to myths, stereotypes, and beliefs regarding the cause of disability, it challenged the professionals during rehabilitation programs to conduct outreach with evidence-based guidelines aiming at educating the families on issues like diagnosis and prognosis (Ngubane & Chetty, Citation2017). Furthermore, the establishment of a common ground between service receivers and service providers was challenged when the professionals’ cultural understanding of the families took greater precedence than the professional understanding (Fellin et al., Citation2015).

The culture within the systems where the individuals played a part in the interprofessional collaboration is the focus here. Some of the systems seemed to be categorized by a culture lacking formal pathways and clear practice, no corresponding approach among staff for interventions and communication between sectors, and diverse viewpoints on rehabilitation between arenas (Jeglinsky et al., Citation2012; Lindsay et al., Citation2018; Rosendahl et al., Citation2021). The lack of formal pathways was perceived by professionals to lead to a practice deprived of team approaches, with professionals mostly providing one-on-one services (Lindsay et al., Citation2018). With a supportive and inclusive culture for interprofessional collaboration at the school arena, transfer of information between school and health professionals was easier, and there was an interest in interacting with other professionals from other professions. Additionally, some professionals, like teachers, working in systems of a pro-collaborative culture described becoming part of that pro-collaborative culture. They worked to onboard more skeptical colleagues, kept an eye on children’s health-related development, and turned to health staff for guidance (Bourke-Taylor et al., Citation2018; Mukherjee et al., Citation2002).

Discussion

Our scoping review was initiated due to a need for an overview of published research on interprofessional collaboration for children with physical disabilities from the viewpoint of the actors involved. Overall, the 29 included studies provide valuable insight into how the actors involved consider this collaboration. Here, we discuss how the four identified themes: communication, knowledge, roles, and culture in interprofessional collaboration act as barriers and facilitators, which are the two cross-cutting themes of our final stage of the analysis.

Barriers

Evidence highlights how individuals in interprofessional collaboration considered daily, informal, brief, and frequent communication to be what interprofessional collaboration is about (Morgan et al., Citation2015), which underpins the importance of having operating systems through which knowledge can be shared readily. According to our results, a hierarchy of knowledge was recognized as having a destabilizing effect on communication in interprofessional collaboration (Reeder & Morris, Citation2021; Skagestad et al., Citation2021). This hierarchy challenges the dialogue and the construction of a “we” between the receiver and giver of services as well between the service providers. In situations, where some knowledge is recognized as being more valuable, there is a top-down perspective concerning the importance of knowledge, which has a destructive influence on the level of participation and thereby the communication among the participants in the collaboration. Such a practice might act as a barrier to well-functioning interprofessional collaboration. Professionals indicated that having competent systems promoted a good practice of information sharing to secure patient confidentiality in interprofessional collaboration (Mukherjee et al., Citation2002; Weglarz-Ward et al., Citation2020). Indeed, when the systems available for individuals to share information are less operative and not in adherence with regulations concerning patient confidentiality, collaboration is hindered.

Cases indicating an uneven legitimization of knowledge were observed when the professionals considered parents’ competence concerning their child to a lesser extent (Tragoulia & Strogilos, Citation2013), which lead to an absence of collaboration with parents by degrading the parents’ knowledge. Such a subordination of knowledge seemingly occurs because professionals believe their expertise is sufficient in collaborating with the child. Also, this practice inhibits collaboration, as parents are required to adhere to instructions from professionals based on the professional’s expertise. Service receivers considered such a practice an imbalance of power between themselves and the professionals providing care (Didier et al., Citation2020).

Several of the included studies in this scoping review recognized how parents act out several roles in interprofessional collaboration. In particular, conflict was observed concerning the coordinator role, and how human dynamics acted as a barrier within interprofessional collaboration (Cameron, Citation2018; Mukherjee et al., Citation2002; Reeder & Morris, Citation2021). Vagueness and non-clarification of roles may lead to role conflicts and tension between the actors involved in the collaboration (Giroux et al., Citation2019; Ødegård, Citation2016). We suggest that the conflict around who should be the coordinator can be recognized as a role conflict where professionals refrain from tasks due to a high workload (Cameron et al., Citation2014). When professionals distance themselves from the coordinator role, it may lead to an uneven workload in the collaborative setting, which then becomes a barrier for interprofessional collaboration. Professionals in nurseries were valued for their closeness to the child and were considered as suitable to take on a coordinator role (Cameron et al., Citation2014). We believe that such a statement must be seen in relation to how children spend most of their time at a nursery or school, and professionals from the educational sector are considered an important part of the team in terms of interprofessional collaboration. Further, an area that requires attention to achieve well-rounded interprofessional collaboration is clarity and clarification of roles, which needs to be solved within systems and organizations.

In Norway, a new national guideline requiring municipalities to designate a child coordinator has recently been established. Such a national guideline can be understood as a response to vagueness and to promote clarification of the coordinator role as well as avoid pulverizing responsibility (Norwegian Directorate of Health, Citation2022). Nevertheless, according to the Norwegian Federation of Organizations of Disabled People (FFO), smaller municipalities have had to add a variety of functions to the role of a child coordinator due to financial constraints (Prop 100 L, Citation2020–2021). The question that thus arises is whether the child coordinator can prioritize the coordination of services to children with disabilities. We believe that such a practice can be linked to what Cameron (Citation2018) defines as bureaucratic systems.

Regarding cultural understanding in interprofessional collaboration, our results revealed that when professionals sought advice from other colleagues to improve their own understanding of the child and the family in question, having a different cultural background than their own, the clinical focus tended to become second priority (Fellin et al., Citation2015). Overlooking the needs of the individual child by generalizing culture may be considered as a barrier and thereby create disruption in the interprofessional collaboration. However, to build relationships with clients and families, some understanding of their cultural context was considered beneficial (Fellin et al., Citation2015). Notably, the professionals’ view on culture might implicitly be biased by the current emphasis on evidence-based practice, which is embedded in western biomedicine and does not leave room for alternative understandings (Carrie et al., Citation2015). Accordingly, professionals need to be aware of the possible contrasting views that may exist in order to build good relationships. Indeed, to set the framework for a well-functioning interprofessional collaboration, we argue that the families themselves should be the main source of providing the cultural understanding (Fellin et al., Citation2015). As the results emphasize, if systems and settings were characterized by a non-collaborative culture, they function as barriers for interprofessional collaboration by causing miscommunication and preventing professionals from achieving such a practice (Lindsay et al., Citation2018; Rosendahl et al., Citation2021). Hence, a non-collaborative culture could bring forth a practice where the service recipients are less likely to be receiving the care they believed was important (Nijhuis et al., Citation2007).

Facilitators

Evidence and policies highlight that the voices of all involved parties, including the child, in a collaborative process are to be viewed and taken into account in order to achieve balanced communication (Edwards, Citation2012; Jordan et al., Citation2018; Norwegian Directorate of Health, Citation2023). When commitment to a shared purpose was clear and jointly built, the individuals were able to recognize the knowledge of the other actors involved as a resource, which could be a facilitator for the communication within the collaboration (Rantavuori et al., Citation2017).

Technology creates new possibilities for information transmission (Graves & Doucet, Citation2016). One of the included studies in our scoping review revolved around the facilitating role technological communication systems may play with regard to the communication within collaboration (Gulmans et al., Citation2012). The study indicated that technology could be a contributor and thus a facilitator for the actors involved, in terms of keeping in touch with team members and the transfer of information in a timely manner. Communication technologies have the potential to make continuity in care possible and improve decision-making and interprofessional collaboration. One reason for such a potential is that technology allows professionals to work with the same patient over an extended period of time (Graves & Doucet, Citation2016).

Sharing knowledge within the collaborative team is recognized as a facilitator for interprofessional collaboration. In collaboration, where the knowledge of the perspectives represented is listened to and taken into account, relational approaches can occur. Being able to listen to and understand others enables those taking part in the interprofessional collaboration to expand their understanding of the problem. Further, the actors involved in the collaboration can work on cohesiveness by applying this knowledge and adjusting their approaches according to each other, aiming toward a common goal, which promotes successful interprofessional collaboration (Edwards, Citation2012).

The theme culture in interprofessional collaboration could appear as a facilitator for interprofessional collaboration through a pro-collaborative culture within the settings where interprofessional collaboration occurred (Mukherjee et al., Citation2002). A system and structure where management and leadership have a positive attitude toward collaboration can lead to a more pro-collaborative culture among the actors involved. This might ease the information flow and enhance relational practices, hence enabling well-functioning interprofessional collaboration. However, we argue that obtaining such a pro-collaborative culture requires the majority of the systems and structures involved in the interprofessional collaboration to be framed toward such a practice. A development of a local policy to pass on information from health staff to school staff contributes to creating such a constructive culture (Mukherjee et al., Citation2002).

Implications for practice and future research

Our scoping review allows the reader to grasp the commonalities in the literature concerning interprofessional collaboration for children with physical disabilities. In summing up, we want to make both service providers and service users aware of how to act upon the results. Firstly, we suggest that service providers consider their roles within interprofessional collaboration. By focusing on developing the role related to their interprofessional identity, efficient distribution of work demands could be enhanced. Service providers are also recommended to develop their role related to facilitated involvement of service users in the collaboration. Such development can be achieved by focusing on increasing their knowledge and skills on the subject user involvement. Secondly, service users are encouraged to take on an active role in the collaboration, by, for example, asking professionals what their options are and the possible pros and cons concerning these options. Furthermore, we recommend service users to share their expertise, concerning, for example, individual needs.

We recognize how the current extent of knowledge on interprofessional collaboration for children with physical disabilities from the point of view of the actors involved mainly revolves around themes that act as barriers for the collaboration. With the identified shortfall in published studies, future researchers should strengthen the research base, with an emphasis on conducting qualitative research on features that can serve as facilitators of interprofessional collaboration. Knowledge regarding barriers gives an understanding on what does not work; however, to know how to make it work, evidence regarding enabling factors is needed. Future researchers could explore the interaction between participants in the collaboration collectively and not solely individually. Also, upcoming qualitative research should shed more light on interprofessional collaboration practices across organizational boundaries and transitional phases. We believe that such potential research would benefit from drawing on theoretical concepts that support and develop a robust evidence base for understanding interprofessional collaboration with regard to care for children with physical disabilities. Finally, it would be valuable for upcoming research in the field to focus on exploring the characteristics of interprofessional collaboration processes in diverse practices and organizational contexts.

Strengths & limitations

During the development of a search strategy, there is a trade-off between precision and comprehensiveness. Considerations concerning the linking of search terms/words were done to obtain as comprehensive a search as possible while maintaining precision to be able to answer the review question. This gave us a broad and thorough search strategy, which we argue to be a strength of our scoping review. Another strength is that the search strategy was developed along with university librarians and reviewed by an independent librarian.

The inclusion and exclusion criteria may have caused a bias effect, as not all studies may have used the term “physical disability” in their abstracts or keywords and may have therefore been excluded. Also, we acknowledge that some included studies were cited more than others, because their comprehensiveness was better suited to represent our results. Despite these limitations, this scoping review contributes new insights for the research field, service providers, and service users on the current extent of knowledge on interprofessional collaboration for children with physical disabilities from the point of view of the actors involved.

Conclusion

The current knowledge base on interprofessional collaboration for children with physical disabilities from the point of view of the actors involved revolves around four key themes: communication, knowledge, roles, and culture in interprofessional collaboration. Communication relates to exchange and interplay of information; knowledge is possessed, used, and demanded; roles are taken on and given and culture influences habits, norms, and policies. Interprofessional collaboration is affected by how these four themes act as facilitators and barriers. Further, they mainly act as barriers and, to a lesser extent, as facilitators. The current review demonstrates how one cannot anticipate that simply bringing service providers and service receivers together in teams will lead to effective interprofessional collaboration. There is a need for further exploration into enabling factors in order to support the innovation of interprofessional collaboration for all actors involved in the care of children with physical disabilities.

Abbreviations

| SCOSD | = | Southern California Ordinal Scales of Development |

| NHS | = | National Health Service |

| MPOC | = | Measure of processes of Care (service receiver) |

| MPOC SP | = | Measure of Processes of Care for service providers |

| ISP | = | Individualised team |

| OTs | = | Occupational therapists |

| PTs | = | Physiotherapists |

| MP | = | Multiprofessional teams |

| HCPs | = | Healthcare professionals |

| IPC | = | Interprofessional collaboration |

| FCC | = | Family centered care |

| QoL | = | Quality of Life |

| CP | = | Cerebral Palsy |

| EI | = | Early intervention |

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this article.

Acknowledgments

The systematic and peer-reviewed literature search was conducted by The Literature Search Expert Group at OsloMet – Oslo Metropolitan University.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Line Myrdal Styczen

Line Myrdal Styczen is a PhD-student in the Department of Rehabilitation Science and Health Technology, Faculty of Health Sciences, Oslo Metropolitan University, Norway. Her research has focused on children’s everyday life and interprofessional collaboration.

Sølvi Helseth

Sølvi Helseth is a professor of Nursing in Child and Adolescent Health and Quality of Life. She is also Vice-Dean of Research at the Faculty of Health Sciences, Oslo Metropolitan University, Norway.

Karen Synne Groven

Karen Synne Groven is a professor in the Department of Rehabilitation Science and Health Technology, Oslo Metropolitan University, Norway, and the Faculty of Health Sciences, VID Specialized University, Norway. In her research, she has focused on rehabilitation, public health, and women’s health.

Mona-Iren Hauge

Mona-Iren Hauge is Associate Professor and dean at the Faculty of Social Studies at VID Specialized University, Norway.

Tone Dahl-Michelsen

Tone Dahl-Michelsen is a professor of health and rehabilitation in the Department of Health, Faculty of Health Science, VID Specialized University, Norway and in the Department of Rehabilitation Science and Health Technology, Faculty of Health Sciences, Oslo Metropolitan University, Norway. Her research has focused on professional practice and rehabilitation.

References

- Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

- Berman, S., Miller, A. C., Rosen, C., & Bicchieri, S. (2000). Assessment training and team functioning for treating children with disabilities. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 81(5), 628–633. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0003-9993(00)90047-9

- Bourke-Taylor, H. M., Cotter, C., Lalor, A., & Johnson, L. (2018). School success and participation for students with cerebral palsy: A qualitative study exploring multiple perspectives. Disability and Rehabilitation, 40(18), 2163–2171. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2017.1327988

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Cameron, D. L. (2018). Barriers to parental empowerment in the context of multidisciplinary collaboration on behalf of preschool children with disabilities. Scandinavian Journal of Disability Research, 20(1), 277–285. https://doi.org/10.16993/sjdr.65

- Cameron, D. L., & Tveit, A. D. (2019). ‘You know that collaboration works when …’ identifying the features of successful collaboration on behalf of children with disabilities in early childhood education and care. Early Child Development and Care, 189(7), 1189–1202. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2017.1371703

- Cameron, D. L., Tveit, A. D., Midtsundstad, J., Nilsen, A. C. E., & Jensen, H. C. (2014). An examination of the role and responsibilities of kindergarten in multidisciplinary collaboration on behalf of children with severe disabilities. Journal of Research in Childhood Education, 28(3), 344–357. https://doi.org/10.1080/02568543.2014.912996

- Capjon, H., & Bjørk, I. T. (2010). Rehabilitation after multilevel surgery in ambulant spastic children with cerebral palsy: Children and parent experiences. Developmental Neurorehabilitation, 13(3), 182–191. https://doi.org/10.3109/17518421003606151

- Carrie, H., Mackey, T. K., & Laird, S. N. (2015). Integrating traditional indigenous medicine and western biomedicine into health systems: A review of Nicaraguan health policies and miskitu health services. International Journal for Equity in Health, 14, 129. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-015-0260-1

- Carron, T., Rawlinson, C., Arditi, C., Cohidon, C., Hong, Q. N., Pluye, P., Gilles, I., & Peytremann-Bridevaux, I. (2021). An overview of reviews on interprofessional collaboration in primary care: Effectiveness. International Journal of Early Childhood Special Education, 21(2), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.5334/ijic.5588

- D’Amour, D., Ferrada-Videla, M., San Martin Rodriguez, L., & Beaulieu, M.-D. (2005). The conceptual basis for interprofessional collaboration: Core concepts and theoretical frameworks. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 19(S1), 116–131. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820500082529

- Didier, A., Dzemaili, S., Perrenoud, B., Campbell, J., Gachoud, D., Serex, M., Staffoni-Donadini, L., Franco, L., Benaroyo, L., & Maya, Z.-S. (2020). Patients’ perspectives on interprofessional collaboration between health care professionals during hospitalization: A qualitative systematic review. Joanna Briggs Institute Evidence Synthesis, 18(6), 1208–1270. https://doi.org/10.11124/jbisrir-d-19-00121

- Edwards, A. (2012). The role of common knowledge in achieving collaboration across practices. Learning, Culture & Social Interaction, 1(1), 22–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lcsi.2012.03.003

- Edwards, A. (2017). Revealing relational work. In A. Edwards (Ed.), Working relationally in and across practices: A cultural-historical approach to collaboration (pp. 1–22). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781316275184.001

- Fellin, M., Desmarais, C., & Lindsay, S. (2015). An examination of clinicians’ experiences of collaborative culturally competent service delivery to immigrant families raising a child with a physical disability. Disability and Rehabilitation, 37(21), 1961–1969. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2014.993434

- Fukkink, R., & Lalihatu, E. S. (2020). A realist synthesis of interprofessional collaboration in the early years: Becoming familiar with other professionals. International Journal of Integrated Care, 20(3), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.5334/ijic.5482

- Giroux, C. M., Wilson, L. A., & Corkett, J. K. (2019). Parents as partners: Investigating the role(s) of mothers in coordinating health and education activities for children with chronic care needs. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 33(2), 243–251. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2018.1531833

- Gmmash, A. S., Effgen, S. K., & Goldey, K. (2020). Challenges faced by therapists providing services for infants with or at risk for cerebral palsy. Pediatric Physical Therapy, 32(2), 88–96. https://doi.org/10.1097/PEP.0000000000000686

- Goodwin, J., Lecouturier, J., Smith, J., Crombie, S., Basu, A., Parr, J. R., Howel, D., McColl, E., Roberts, A., Miller, K., & Cadwgan, J. (2019). Understanding frames: A qualitative exploration of standing frame use for young people with cerebral palsy in educational settings. Child: Care, Health and Development, 45(3), 433–439. https://doi.org/10.1111/cch.12659

- Graves, M., & Doucet, D. S. (2016). Factors affecting interprofessional collaboration when communicating through the use of information and communication technologies: A literature review. Journal of Research in Interprofessional Practice and Education, 6(2), 1–33. https://doi.org/10.22230/jripe.2017v6n2a234

- Gulmans, J., Vollenbroek-Hutten, M., van Gemert-Pijnen, L., & van Harten, W. (2009). Evaluating patient care communication in integrated care settings: Application of a mixed method approach in cerebral palsy programs. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 21(1), 58–65. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzn053

- Gulmans, J., Vollenbroek-Hutten, M., van Gemert-Pijnen, L., & van Harten, W. (2012). A web-based communication system for integrated care in cerebral palsy: Experienced contribution to parent-professional communication. International Journal of Integrated Care, 12(1). https://doi.org/10.5334/ijic.672

- James, C., & Chard, G. (2010). A qualitative study of parental experiences of participation and partnership in an early intervention service. Infants & Young Children, 23(4), 275–285. https://doi.org/10.1097/IYC.0b013e3181f2264f

- Jeglinsky, I., Salminen, A.-L., Carlberg, E. B., & Autti-Rämö, I. (2012). Rehabilitation planning for children and adolescents with cerebral palsy. Journal of Pediatric Rehabilitation Medicine, 5(3), 203–215. https://doi.org/10.3233/PRM-2012-0213

- Jordan, A., Wood, F., Edwards, A., Shepherd, V., & Joseph-Williams, N. (2018). What adolescents living with long-term conditions say about being involved in decision-making about their healthcare: A systematic review and narrative synthesis of preferences and experiences. Patient Education and Counseling, 101(10), 1725–1735. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2018.06.006

- Kalleson, R., Jahnsen, R., & Østensjø, S. (2021). Comprehensiveness, coordination and continuity in services provided to young children with cerebral palsy and their families in Norway. Child Care in Practice, 28(4), 610–624. https://doi.org/10.1080/13575279.2021.1898934

- Larsson, M. (2000). Organising habilitation services: Team structures and family participation. Child: Care, Health and Development, 26(6), 501–514. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2214.2000.00169.x

- Lindsay, S., Duncanson, M., Niles-Campbell, N., McDougall, C., Diederichs, S., & Menna-Dack, D. (2018). Applying an ecological framework to understand transition pathways to post-secondary education for youth with physical disabilities. Disability and Rehabilitation, 40(3), 277–286. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2016.1250171

- McKinnon, C., White, J., Morgan, P., Harvey, A., Clancy, C., Fahey, M., & Antolovich, G. (2021). Clinician perspectives of chronic pain management in children and adolescents with cerebral palsy and dyskinesia. Physical & Occupational Therapy in Pediatrics, 41(3), 244–258. https://doi.org/10.1080/01942638.2020.1847236

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Altman, D. G. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine, 6(7), e1000097. Article e1000097 https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

- Morgan, S., Pullon, S., & McKinlay, E. (2015). Observation of interprofessional collaborative practice in primary care teams: An integrative literature review. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 52(7), 1217–1230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2015.03.008

- Mukherjee, S., Lightfoot, J., & Sloper, P. (2002). Communicating about pupils in mainstream school with special health needs: The NHS perspective. Child: Care, Health and Development, 28(1), 21–27. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2214.2002.00242.x

- Ngubane, M., & Chetty, V. (2017). Caregiver satisfaction with a multidisciplinary community-based rehabilitation programme for children with cerebral palsy in South Africa. South African Family Practice, 59(1), 35–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/20786190.2016.1254929

- Nijhuis, B. J. G., Reinders-Messelink, H. A., de Blecourt, A. C. E., Hitters, W. M. G. C., Groothoff, J. W., Nakken, H., & Postema, K. (2007). Family-centred care in family-specific teams. Clinical Rehabilitation, 21(7), 660–671. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269215507077304

- Nijhuis, B. J. G., Reinders-Messelink, H. A., de Blecourt, A. C. E., Olijve, W. G., Haga, N., Groothoff, J. W., Nakken, H., & Postema, K. (2007). Towards integrated paediatric services in the Netherlands: A survey of views and policies on collaboration in the care for children with cerebral palsy. Child: Care, Health and Development, 33(5), 593–603. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2214.2006.00719.x

- Norwegian Directorate of Health. (2022, 11 April). Samarbeid om tjenester til barn, unge og deres familier. Nasjonal veileder [Collaboration on services to children, youth and their families. National guidelines]. Author. Retrieved October 1, 2023, from https://www.helsedirektoratet.no/veiledere/samarbeid-om-tjenester-til-barn-unge-og-deres-familier

- Norwegian Directorate of Health. (2023, 30 November). Rehabilitering Habilitering, Individuell Plan Og Koordinator. Nasjonal Veileder [Rehabilitation, Habilitation, Individual Plan and Coordinator. National Guidelines]. Author. Retrieved September 15, 2023, from https://www.helsedirektoratet.no/veiledere/rehabilitering-habilitering-individuell-plan-og-koordinator

- Ødegård, A. (2016). Konstruksjoner av tverrprofesjonelt samarbeid [Constructions of interprofessional collaboration]. In E. Willumsen & A. Ødegård (Eds.), Tverrprofesjonelt samarbeid: Et samfunnsoppdrag [interprofessional collaboration: A community mission] (2 ed., pp. 113–127). Universitetsforlaget.

- Peters, M., Godfrey, C., McInerney, P., Munn, Z., Tricco, A., & Khalil, H. (2020). Scoping reviews. In E. A. In & Z. Munn (Eds.), Joanna Briggs Institute manual for evidence synthesis (pp. 406–451). Joanna Briggs Institute. https://doi.org/10.46658/JBIMES-20-12

- Pickering, D., & Busse, M. (2010). An audit of disabled children’s services - what value is MPOC-SP? Clinical Audit, 2, 13–22. https://doi.org/10.2147/CA.S8073

- Prop. 100 L. (2020–2021). Endringer i velferdstjenestelovgivningen (samarbeid, samordning og barnekoordinator) [changes in the welfare service legislation (collaboration, coordination and children’s coordinator)]. Ministry of Education and Research. https://www.regjeringen.no/no/dokumenter/prop.-100-l-20202021/id2838338/?ch=7

- Pullon, S., Morgan, S., Macdonald, L., McKinlay, E., & Gray, B. (2016). Observation of interprofessional collaboration in primary care practice: A multiple case study. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 30(6), 787–794. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2016.1220929

- Rantavuori, L., Kupila, P., Karila, K., & Varhaiskasvatusry, S. (2017). Relational expertise in preschool–school transition. Journal of Early Childhood Education Research, 6(2), 230–248.

- Reeder, J., & Morris, J. (2021). Becoming an empowered parent. How do parents successfully take up their role as a collaborative partner in their child’s specialist care? Journal of Child Health Care, 25(1), 110–125. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367493520910832

- Reeves, S., Pelone, F., Harrison, R., Goldman, J., & Zwarenstein, M. (2017). Interprofessional collaboration to improve professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2018(8). https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD000072.pub3

- Rosendahl, N. M. H., Jensen, R. C., & Holst, M. (2021). Efforts targeted malnutrition among children with cerebral palsy in care homes and hospitals: A qualitative exploration study. Journal of Early Childhood Education Research, 35(1), 49–57. https://doi.org/10.1111/jhn.12916

- Ryan, C., & Quinlan, E. (2018). Whoever shouts the loudest: Listening to parents of children with disabilities. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 31(S2), 203–214. https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.12354

- Skagestad, L. J., Østensjø, S., & Ulvik, O. S. (2021). Collaborations between young people living with bodily impairments and their multiprofessional teams: The relational dynamics of participation and power. Children and Society, 35(5), 633–647. https://doi.org/10.1111/chso.12419

- Solomon, P., & Risdon, C. (2014). A process oriented approach to promoting collaborative practice: Incorporating complexity methods. Medical Teacher, 36(9), 821–824. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2014.917285

- Sylvester, L., Ogletree, B. T., & Lunnen, K. (2017). Cotreatment as a vehicle for interprofessional collaborative practice: Physical therapists and speech-language pathologists collaborating in the care of children with severe disabilities. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 26(2), 206–216. https://doi.org/10.1044/2017_AJSLP-15-0179

- Tragoulia, E., & Strogilos, V. (2013). Using dialogue as a means to promote collaborative and inclusive practices. Educational Action Research, 21(4), 485–505. https://doi.org/10.1080/09650792.2013.832342

- Weglarz-Ward, J. M., Santos, R. M., & Hayslip, L. A. (2020). How professionals collaborate to support infants and toddlers with disabilities in child care. Early Childhood Education Journal, 48(5), 643–655. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-020-01029-5

- World Health Organization. (2008). Primary health care now more than ever: Introduction and overview. Author. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/69863

- World Health Organization. (2010). Framework for action on interprofessional education and collaborative practice. Author. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/70185/WHO_HRH_HPN_10.3_eng.pdf?sequence=1

- Ziviani, J., Darlington, Y., Feeney, R., Rodger, S., & Watter, P. (2013). Service delivery complexities: Early intervention for children with physical disabilities. Infants & Young Children, 26(2), 147–163. https://doi.org/10.1097/IYC.0b013e3182854224