ABSTRACT

Interprofessional collaboration (IPC) in stroke care is accepted as best practice and necessary given the multi-system challenges and array of professionals involved. Our two-part stroke team simulations offer an intentional interprofessional educational experience (IPE) embedded in pre-licensure occupational therapy, physical therapy, pharmacy, medicine, nursing and speech-language pathology curricula. This six-year mixed method program evaluation aimed to determine if simulation delivery differences necessitated by COVID-19 impacted students’ IPC perception, ratings, and reported learning. Following both simulations, the Interprofessional Collaborative Competency Assessment Scale (ICCAS) and free-text self-reported learning was voluntarily and anonymously collected. A factorial ANOVA using the ICCAS interprofessional competency factors compared scores across delivery methods. Content and category analysis was done for free-text responses. Overall, delivery formats did not affect positive changes in pre-post ICCAS scores. However, pre and post ICCAS scores were significantly different for interprofessional competencies of roles/responsibilities and collaborative patient/family centered approach. Analysis of over 10,000 written response to four open-ended questions revealed the simulation designs evoked better understanding of others’ and own scope of practice, how roles and shared leadership change based on context and client need, and the value of each team member’s expertise. Virtual-experience-only students noted preference for an in-person stroke clinic simulation opportunity.

Introduction

Given the multi-system challenges and array of professionals involved in stroke care, interprofessional collaboration (IPC) is accepted as best practice and necessary. Our IPC stroke team simulations offer a shared interprofessional education (IPE) experience and are embedded in pre-licensure occupational therapy, physical therapy, pharmacy, medicine, nursing, and speech-language pathology curricula. This 6-year program evaluation aimed to determine if delivery differences necessitated by COVID-19 impacted students’ evaluation outcomes, Interprofessional Collaborative Competency Assessment Scale (ICCAS) ratings, and reported IPC learning from free text responses.

Background

Interprofessional collaboration (IPC) has been associated with reduced rates of medical errors (Reeves et al., Citation2013) and is the accepted best practice in stroke care (Heart and Stroke Foundation Canada, Citation2019; Langhorne et al., Citation2020; Teasell et al., Citation2020). The breadth of multi-system challenges and the array of professionals involved in stroke care is challenging for new learners to navigate. Literature describing IPE clinical simulations often involves students from medicine and nursing, with few simulations including the range of disciplines found on patient-centered health care teams (Champagne-Langabeer et al., Citation2019; Wallace, Citation2017). Our IPE stroke team simulations offer a shared educational and interprofessional socialization space for learners to link professional knowledge, overlaps in care, and relevant IPC practice relationships (Schot et al., Citation2020) across six disciplines including: occupational therapy (OT), physical therapy (PT), pharmacy, medicine, nursing, and speech-language pathology (SLP).

Learners are sensitive to the authenticity of IPE experiences (Thistlethwaite et al., Citation2012). Learning opportunities, therefore, must be aligned with learners’ respective professional programs’ curricula and reflective of learners’ practice experiences. Experiences that are too far a “stretch” from the learners’ lived clinical experience, or where they do not feel they have a meaningful role, are negatively viewed (Loversidge & Demb, Citation2015). Students are likewise sensitive to “add-ons,” i.e., required events they perceive to be less important than profession-specific activities, and those which are not examined (Rogers et al., Citation2017). In previous IPE program evaluation data from our institution (Doucet et al., Citation2014; MacKenzie et al., Citation2017), student feedback consistently highlighted learning values and preferences for integrated curriculum experiences, provision of academic credit, and situations in closely aligned natural teams to enhance IPE experience authenticity.

Given the constraints on instructional time, faculty are reluctant to add IPE activities unless they align with instructional objectives in a contextually relevant way (MacKenzie & Merritt, Citation2013). To this end, faculty designers must work collaboratively, applying their own interprofessional skills, including compromise, when developing interprofessional cases as they learn others’ curricula and scopes of practice (MacKenzie et al., Citation2014). While initial experiences in IPE can be based substantively on interprofessional competencies, more advanced learners seek and benefit from experiences that also provide an opportunity to demonstrate clinical roles and skills (Morison et al., Citation2003).

To address concerns about authenticity, stage of learners, human resources, and best practice standards in both stroke care and simulation, our stroke IPE experience was designed to be embedded in already-occurring skills-based courses of pre-licensure students. The two-stage design includes a simulated inpatient team meeting followed by a simulated stroke clinic. These experiences draw upon respective best practices in simulation designs (INACSL Standards Committee et al., Citation2021), standards for stroke care (Heart and Stroke Foundation Canada, Citation2019; Langhorne et al., Citation2020; Teasell et al., Citation2020), interprofessional competencies (CIHC, Citation2010), and IPE accreditation standards for the participating programs.

Our IPC simulations serve to meet two distinct sets of objectives: 1) interprofessional competencies and 2) clinical competencies for stroke care. While interrelated, both are considered explicitly in the design. Interprofessional competencies focus primarily on understanding distinct and overlapping roles, as well as learning to function as a team through patient/client-centeredness, collaborative leadership, respect, and positive communication (CIHC, Citation2010).

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, our stroke IPE consisted of an in-person team meeting followed a week later by an in-person two-station simulated stroke clinic. In 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic necessitated significant restrictions and changes in the delivery of education (Sahu, Citation2020). In 2020, our stroke IPE was required to be conducted virtually (team meeting format only) and in 2021, the team meeting remained virtual, and the stroke simulations returned to the in-person design. These extraordinary circumstances necessitated curriculum delivery changes and provided an opportunity to evaluate the design and impact of in-person, virtual, or hybrid delivery on student reported outcomes.

The purpose of this mixed method study examining our program evaluation results from 2016 through 2021 is two-fold. First, quantitative analyses were conducted to determine if delivery differences of the stroke IPE over 6 years (i.e., before and during COVID-19 restrictions) negatively impacted the students’ self-reported competencies of interprofessional collaborative practice as measured by the ICCAS (Archibald et al., Citation2014). Additionally, qualitative analysis of free-text responses to four open-ended questions was employed to explore if there were key experience or design features that contributed to their IPC learning.

Methods

The six-year mixed method program evaluation study employed a retrospective pre – post self-reported design. The study was informed by the following four principles (Schuwirth & Van der Vleuten, Citation2019). First, multiple assessment instruments were used and triangulated (i.e., evaluation rubrics for team meeting and simulation, ICCAS, free-text data after each simulation). This is a longitudinal evaluation of the learning event (i.e., 6 years of complete data sets). Instruments collected credible quantitative and qualitative data. Finally, the data produced provided meaningful feedback on the design and delivery. The routine program evaluation study relied exclusively on the use of student participant evaluation data for quality improvement, collected voluntarily and anonymously, and is therefore exempt from REB review under TCPS Article 2.5 (Secretariat on Responsible Conduct of Research, Citation2022).

Participants

Participants were pre-licensure students enrolled in their respective core discipline courses from six professions (second year master’s students in OT, PT and SLP; second year undergraduate nursing students, third year undergraduate pharmacy students, and second year medical students). They completed the two-part interprofessional experience as part of their mandatory interprofessional education programming. Teams of five to seven students remained the same for Parts I and II.

Design

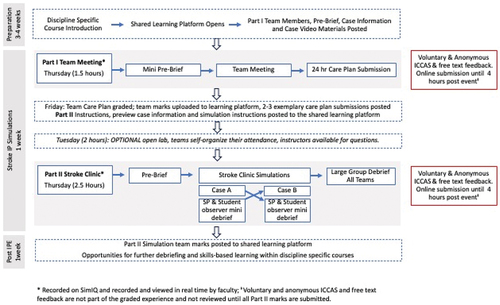

illustrates the IPE design and points of data collection. Discipline-specific instructors explained the IPE structure and deliverables in their respective core curriculum courses. An online learning management system was used to share best practice resources and preparation materials in one learning course space for all learners. The Part I simulated inpatient team meeting and Part II simulated stroke clinic were purposefully designed to require evaluated deliverables that no single profession would have the requisite knowledge to produce independently.

Prior to the 90-minute simulated inpatient team meeting, learners were expected to view an online preparatory case video and written case information. During the team meeting, the teams reviewed the client’s chart and goals. The purpose of the meeting was for each team to create one collaborative care plan that included: 1) three person-centered IPC goals with associated interventions per profession to achieve the goals, 2) a list of other referrals the patient requires, and 3) a 24-hour care plan outlining the interprofessional delivery of care. Collaborative care plans were submitted in the learning management system at the end of the 90-minute session.

Care plans were evaluated by the interprofessional faculty based on each of the three components. Specifically, the teams needed to demonstrate implementation of best practice stroke care guidelines, IPC competencies, and intention to provide coordinated and collaborative teamwork (Reeves et al., Citation2018) throughout the client’s care day. The evaluation used a rubric with the following categories: excellent, very good, good, satisfactory, and fail. Within 24 hours of the team simulation exercise, each team received one grade which contributed to each student’s core course completion.

Part II involved a large group pre-brief, two 30-minute simulated patient (SP) encounters per team, debriefing with the SPs, and a large group debrief. In each 30-minute simulation station, half of each student team worked collaboratively with one SP while the other half observed. For example, nursing, OT and PT students worked collaboratively with a simulated patient with a left hemisphere stroke while medicine, pharmacy, and SLP students observed. The team members then swapped roles for the second station with a different simulated patient. Each SP was recruited and trained by simulated patient educators (SPEs) to provide a realistic portrayal of a person post-stroke. This enhanced the fidelity of the encounter and allowed for “suspension of disbelief” (Hamstra et al., Citation2014), which allowed students to engage in the learning process and devote full attention to tasks and skills required in the scenarios. At the end of each station, the SP debriefed the students to provide feedback on how well they collaborated with each other and with the SP. Meanwhile, the observers learned about others’ roles and then gave feedback about IPC to their team members. A rubric was used to evaluate teams on their patient-centered approach, IPC, evidence-based stroke care, and task completion. Faculty assigned a global rating to each team.

Instrumentation

Upon completion of Parts I and II from 2016 to 2021, all students had the option to voluntarily and anonymously participate in an online feedback survey (hosted on OpinioTM) which included a self-reported retrospective pre – post Interprofessional Collaborative Competency Assessment Scale (ICCAS) (Archibald et al., Citation2014; Schmitz et al., Citation2017). The ICCAS contains 20 questions that are grouped into the 6 CIHC (Citation2010) competencies (Communication Q1–5; Collaboration Q6–8; Roles and responsibilities Q9–12; Collaborative patient/family centered approach Q13–15; Conflict management/resolution Q16–18; Team functioning Q19–20). The ICCAS has shown to be a reliable and valid self-assessment instrument for assessing collaborative interprofessional practice (Archibald et al., Citation2014; Schmitz et al., Citation2017; Violato & King, Citation2019). Although concerns have been raised about the possibility of recall and social desirability bias due to its retrospective design, research suggests these are not introduced by retrospective methodology (Kruger et al., Citation2023).

Additionally, four open-ended questions were asked to obtain free-text responses, including: 1) What new understandings do you have about the role of the other health professions, and did anything surprise you? 2) Do you understand your future role as a health professional as part of a health care team in a different way? 3) How will this experience change your approach to interprofessional experiences in the future? and 4) How does IPC impact your care plan?

Data analyses

Data were downloaded from OpinioTM into Microsoft Excel (2021) (Microsoft, Redmond, WA), cleaned for missing data, and divided into quantitative and qualitative datasets. Quantitative data were analyzed using SPSS (Version 28) with an alpha level of 0.05 for all statistical tests. First, pre – post ICCAS scores for each type of simulation delivery (Face to Face in person (FtF) team meeting, FtF stroke clinic, and virtual team meeting) were examined for standardized effect sizes in terms of Cohen’s d across all years. Effect sizes were interpreted as “large” if differences were greater than 0.8, “moderate” if between 0.79 and 0.50, and “small” if less than 0.5 (Cohen, Citation1988).

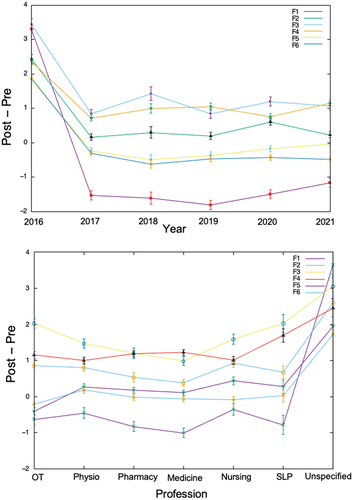

Next, a six-way univariate ANOVA, including only main effects, was conducted. Between-subjects factors included IPE Year, Delivery Method, IPE Design, Profession, and IPE Experience; the within-subject factor was pre/post scores. The ANOVA was applied to individual questionnaire factors. Missing data were excluded from the analysis, factor by factor. This approach generalizes the paired t-test applied to each question (Archibald et al., Citation2014) with the pre/post factor essentially being a paired t-test and with a search for effects of the between-subjects factors added in. The dependent variables for the ANOVA were the six ICCAS domains, defined as follows : F1 = Communication Q1–5; F2 = Collaboration Q6–8; F3 = Roles and responsibilities Q9–12; F4 = Collaborative patient/family centered approach Q13–15; F5 = Conflict management/resolution Q16–18; F6 = Team functioning Q19–20. The six-way ANOVA was applied to each ICCAS domain independently. A previous study on the pre-post data from the IPE Part I (MacKenzie et al., Citation2017) conducted a confirmatory factor analysis, using R software, revealing a significant fit of the factors to the questionnaire items (z equivalent p-values less than 0.001 for all items and on the order of 10−50 for many questions). This justifies the independent ANOVA analysis of each ICCAS factor, in line with other replication studies (Schmitz et al., Citation2017). The levels for the five between-subjects factors were as follows: IPE Year: 2016, 2017, 2018, 2019, 2020, 2021; Delivery Method: In person, Virtual; IPE Design: Team Meeting, Simulated Clinic; Profession: OT, PT, Pharmacy, Medicine, Nursing, Speech, Unspecified and IPE Experience: 2 or less, 3 to 5, > 5, Unspecified (student did not select their profession).

Qualitative data analyses used the free-text data that were collated for each open-ended question. Thematic analysis using a deductive approach was employed using the six CIHC IPC competencies CIHC (Citation2010) as pre-determined themes, plus an “open” code (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). The open code was used to capture information beyond the CIHC competency themes. The first two authors set up the coding structure. The author group was aware of their influential role with interpreting the data (Vernon, Citation2009). To mitigate potential biases of the author group, several safeguards were established. Specifically, a team member who is not otherwise involved with the IPE experiences completed the first pass coding, then all profession-specific instructors reviewed their respective sections for coding accuracy and quote selection related to the thematic codes. Throughout the analysis process, the author group discussed discrepancies and interpretations. An audit trail captured the decision-making process.

Results

displays the number of students across evaluation year, discipline, response rate per simulation, and delivery format. In 2016 there were several students who did not declare their profession in their voluntary responses. “Unspecified” participants in 2016 could have been participants from all of the six disciplines in . Additionally, in 2016, there were 12 nurse practitioners (NP) students who participated with the nursing cohort, but it is unclear how they declared their professional designation (i.e., nursing or unspecified). Possible options for participants selecting “unspecified” may include a lack of category (i.e., nurse practitioner), a feeling of feeling safer to provide feedback if identifying as “other,” and/or students were careless or inattentive with their response (Johnson, Citation2005). In total, 2405 students completed part 1, with 1498 students in FtF format and 907 in virtual format. For part II, 1471 students participated in the FtF simulated Stroke Clinic (the distributed medical school campus does not travel to participate). In 2018 part II was canceled due to a storm. In 2020, 421 students completed a second virtual team meeting for part II due to COVID restrictions not permitting FtF programming. provides the ICCAS effect sizes per delivery method. Nearly all of the effect sizes can be classified as large (Cohen, Citation1988). The effect sizes are all around one so that no differences are apparent in accordance with the formal ANOVA post-hoc analysis presented in .

Table 1. Participant disciplines per year, delivery format and ICCAS response rates.

Table 2. ICCAS effect sizes by delivery method.

As per , results from the six-way univariate ANOVA found no significant affect changes in overall pre-post ICCAS scores across delivery formats. Pre-post ICCAS scores were significantly different for two interprofessional competencies: roles/responsibilities (F3, p = .028) and collaborative patient-/family-centered approach (F4, p < .001). Only the Year and Profession ANOVA factors were associated with any significant difference between pre and post scores. In those cases, the average post score was greater than the average pre score. Given the significant differences, examination of the profile plots showed that 2016 was significantly different from all the other years and that the “unspecified” category of Profession was significantly different from the other Profession categories. An analysis of the data without the “unspecified” cases reporting no response for profession does not significantly change the results. All of the significant effects found remain the same and the profile plot of the factors by year does not visibly change.

Table 3. ANOVA analysis of ICCAS questionnaire factors.

The two significant ANOVA factors suggest, by the definition of the ANOVA null hypothesis, at least one of the groups is different from the others. plots the post hoc analysis to show that the significantly different groups are year 2016 and the “unspecified” profession. The post-hoc analysis and profile plots makes it clear that any further t-testing would reveal only spurious results given that the error bars along each factor profile overlap.

Qualitative thematic analysis

The program evaluation explored if there were key experience or design features that contributed to IPC learning. Qualitative data, including approximately 10,000 free-text comments across four open-ended questions and six years, were analyzed deductively using the IPC competencies. These themes are described in detail below. Overall, students described how the IPE experiences required them to use, build skills in, and appreciate the value for interprofessional competencies. Client-centredness was described as the teams’ focal point; clarifying roles, establishing leadership, and organizing team interventions were done around the client’s needs. All competencies were experienced as intertwined with each other, each supporting and establishing the need for the others. Students described how their experience helped them build confidence in these skills and their plans to use them in future practice.

Client-centredness

Client-centredness emerged as both an underlying motivation for, and the intended outcome of, interprofessional care. Thus, other competencies showed up in discussion of client-centered care. Good team functioning was needed “to balance competing objectives and priorities that are important to the patient without overwhelming them” (Medical Student). Similarly, strong interprofessional communication was needed to support the patient: “a team approach and good communication is needed for proper patient care” (Physiotherapy Student). Collaborative leadership was used with the intent to provide client-centered care and to meet a variety of patient needs: “I now understand how heavily we will all rely on each other moving forward in practice. We all play an integral part in ensuring proper patient care” (Pharmacy Student). Students often oriented their profession’s role to client-centered practice: “I feel as though I have a better understanding of where I fit in the puzzle and how I will be looking at the client’s goals closely and help to collaborate with the other professionals to advocate for the client to ensure we are going towards their goals” (Occupational Therapy Student). Client-centredness also provided a central pillar on which to manage and navigate potential team conflicts: “I have a lot more respect for those in other occupations; their roles are crucial for patient care” (Medical Student). Students noted the importance of interprofessional care for better client outcomes, including preventing errors, reducing redundancy, providing holistic care, appreciating diverse aspects of the client’s experience, and improving overall wellbeing. “Overall, it was really nice to see that multiple professions can work together to deliver the best care to a patient” (SLP Student). “The importance of asking the patient what their goals are and what they expect and want for their care and being able to communicate these with other health care professionals so that we ensure patient needs are met” (Nursing Student).

Role clarification – own and others’

Many students reflected on their experience of role clarification, both their role and others’ roles. This competency emerged interwoven with the others, for example, role clarification in terms of communication, collaborative leadership, and team function is reflected throughout. Many students expressed a clarification in the depth of their role, understanding their role, “Not necessarily in a different way but rather a deeper understanding of my previous understanding” (Physiotherapy Student). Better understanding of others’ roles appeared to improve some students’ awareness of professional boundaries: “I feel that understanding the roles of others has helped clarify my own role and space between other professions” (Occupational Therapy Student). For many, this involved understanding their role in relation to others’ roles: “I understand my role as a part of the whole picture, instead of being the whole picture. I always knew other disciplines are involved, but knowing the specifics helps me appreciate it more and see how everything works together” (Physiotherapy Student).

Medical students expressed clarification of their role in a rehabilitation context, where their role may not have been as significant as they expected: “I realized that medicine is just a small piece of what is involved in the management and rehabilitation of a stroke patient” (Medical Student). With this came recognition of the importance of others’ roles in this context: “I think this just solidified the role of my profession in a different manner. More acutely I have a larger role, but in the long-term management, medicine really needs other professions to help with patient care” (Medical Student).

Students also frequently expressed appreciation for the roles of other professions, particularly when their scope was clarified:

I have a better appreciation for the roles of occupational therapy and physiotherapy now … after hearing how these two professions can contribute to stroke care through assisting with daily tasks, restoring patient’s former abilities and helping patients regain independence, I realize that these are incredibly important in health care. (Pharmacy Student)

Others noted the importance of understanding the breadth of scope of other professions: “I didn’t realize how much the nurses do in a day. Truly seems like they do a bit of everything” (Physiotherapy Student). Another student noted: “I have a new understanding of the scope of practice for pharmacy students and have learned that it is much broader than I initially thought” (Nursing Student). For others, learning specific details of a profession’s scope was important: “I was surprised to find out that physiotherapy did blood pressure monitoring” (Occupational Therapy Student). The importance of professions’ roles was brought to awareness by their contribution, but also on teams where a profession was absent: “By not having an SLP on our team, it became dramatically clear their critical role in working with patients with aphasia” (OT Student).

Collaborative Leadership

Collaborative leadership emerged in students’ recognition of the importance of sharing leadership roles. Students recognized their own leadership potential and contribution to the team: “I felt like I had to take the lead, and realized there may be times in my future profession where people from other professions are looking to me, even though I am “just a nurse” (Nursing Student). In addition, students recognized that each profession has the skills to lead and can take the lead when needed: “I learned that each profession has the skills to facilitate and lead within the group … It was neat how all professions came together with separate strengths to collaborate on one plan” (Occupational Therapy Student). Collaborative leadership also meant learning to step back to let others lead: “I think this experience has allowed me to gain further insights into the concept of shifting leadership and allowing the most appropriate healthcare practitioner to take the lead in certain situations” (Medical Student). Sharing leadership helped students understand their role: “I see my role as more specific than before, other professions take charge of certain things more than I had thought” (Medical Student). Students also noted the importance of diverse expertise and leadership from others: “It was really neat to see how everyone is an expert in their own field, and brings a different lens to the case” (SLP Student). The importance of encouraging collaborative leadership and acknowledging others’ expertise was also noted:

My group found that at first, Med/Pharm felt like they couldn’t do much, but as the session went on, they contributed a lot. I learned from this that it is important to encourage your colleagues to draw from their strengths and experiences and share how much you value their input. (Occupational Therapy Student)

Similarly, students found shared expertise set the stage for collaboration: “I was not aware that there is so much overlap of knowledge between different disciplines. It was interesting to see individuals from different professions consulting with one another and coming up with a plan that everyone is satisfied with” (SLP Student). Frequently, students noted that having the opportunity to practice collaborative leadership would lead them to more likely and confidently consult and refer to other professionals in the future. As a Pharmacy student noted: “I feel more of a sense of community with other healthcare professions after today and will be much less hesitant to reach out to them as required for patient care.” A nursing student commented on how this event “highlighted the importance of collaborative practice in stroke rehabilitation.”

Interprofessional Communication

Students described the characteristics, importance, and challenges of interprofessional communication. “Being a listener” was noted as a key component of interprofessional communication because “the other members of health care are vital to the care of the patient and working together is critical” (Medical Student). In addition, interprofessional communication involved learning, “Don’t be hesitant to put my ideas on the table and to get my ideas challenged” (Pharmacy Student). The importance of encouraging others to share their ideas and being open to new ideas was also described as important. A nursing student commented: “One of our group’s strengths was interprofessional communication. Not only did we engage in non-violent and respectful forms of communication with each other and with the patient, but it felt like we truly valued what the other professions had to say and brought to the table.”

Role overlaps and gaps highlighted the need for interprofessional communication: “The professions overlap, and things could potentially be either very redundant or could be overlooked if the team is not effectively communicating” (SLP Student). In addition, communication was important because everyone brought diverse ideas and information that contributed to supporting the patient: “I felt that no matter the problem, there was always someone who had a suggestion. There was always someone to ‘bring something to the table’ to help solve our patient’s problems” (Pharmacy Student). Students also noted challenges when profession-specific ideas needed to be shared with the team:

I noticed that colleagues from other professions may misunderstand what I am saying due to their different frame of reference, so I need to be very clear and confident when communicating my ideas in order to be effective. Especially if the idea is not one that is well known by others, (Occupational Therapy Student)

Recognizing their challenges, students also described the importance of the IPE for practicing communication and building confidence communicating: “I am more confident that I can contribute valuable health care interventions and am more confident in communicating with other healthcare team members” (Physiotherapy Student).

Team Function

Students noted the importance of having their individual expertise recognized within the team, and of understanding where they overlap with others and can collaborate for effective patient care. In line with collaborative leadership, students recognized that their role on the team changed based on the context and patient’s needs:

The first case showed me that the I will not always have a big role on a health care team and it’s important to step back and listen to the other health professionals discuss their roles and contribute things that could help them from a SLP perspective. (Speech Language Pathology Student)

Students noted the importance of being recognized for their role on the team beyond stereotypes of their profession: “I appreciate being involved in the team and not just being recognized as a medication dispenser but as a medication expert” (Pharmacy Student).

Students also described learning how they could work as a team on shared goals with the patient and get assistance from others to help the client work toward goals. For example, one occupational therapy student noted:

Before I saw it as “I do this, you do that and don’t do my thing,” but now I see how in order to improve care we all have to collaborate - ex. teaching nursing how to coach the client on guarding and improving bed mobility, or asking pharmacy what effects medication could have on the effectiveness of therapy.

The importance of how the professions’ interventions would influence each other, and how this needed to be reflected in the plan was also described. One physiotherapy student noted, “the importance of speaking with the nurse re: patient’s tolerance of physiotherapy from the day before and effect on vitals/health status and the importance of collaborating with pharmacy to check there are no side effects that may impact physiotherapy (i.e., dizziness, fatigue). Similarly, a medical student noted how it is “important to be aware of patient goals and how different interventions may help or hinder these goals.” Students described gaining a better understanding of their place on the team and how they could work as a team to improve patient care and support each other in their roles, while also accomplishing profession-specific goals.

Conflict resolution

Students described strategies they used to prevent and mitigate conflicts. Frequently, students across professions described needing to “keep an open mind” to others’ perspectives and ensure open communication between professions. When asked how this experience will influence their approach to interprofessional care in the future, one pharmacy student responded: “My approach in the future will revolve around having open communication with other team members.” Being open to shifting leadership roles, offering expertise, and collaborating within the team also helped to mitigate conflicts around time management. Very few students described conflict or needing to resolve conflicts within their team. Another student (nursing) shared this: “I felt there was a conflict in our ideas of how the simulation would play out when we were preparing for the simulation, and although I tried to address this using questions and clarifying statements, I feel like I wasn’t really listened to and/or understood. I’ve been in very similar situations in a clinical setting with these professions, and there was a healthier/more positive dialogue and collaboration between the nursing staff, myself, and the PT & OTs.” A key learning shared was that “It can be difficult to communicate when you have different professional agendas” (PT Student).

Open- ended response

The open-ended student evaluation responses were overwhelmingly positive. Students who experienced only the virtual formats for part I or II noted a preference for an in-person stroke clinic simulation opportunity. While their scores still positively changed between the two online team encounters, they noted missing the experience to work with each other and the simulated patient provided by a FtF simulation.

Triangulation of evaluation assessments, icass, and free-text analysis

Taken together, the quantitative and qualitative analysis support significant findings that the experience developed a better understanding of others’ and own scope of practice, how roles and shared leadership change based on context and client need; and each team member’s expertise is important and valued. Even students who previously had experienced interprofessional education training found the stroke IPE simulation experience had a meaningful impact on their learning: “ … this felt like the first time I actually got to practice interprofessional collaboration as I didn’t feel other IPE events were as effective as this one” (PT Student).

Discussion

The purpose of this six-year program evaluation was to review if design differences affected the ICCAS ratings across different delivery designs, and to identify if key experience or design features enhanced IPC learning. The results of the ICCAS ratings and the free text responses are in line with other research that shows interprofessional stroke simulations result in development of IPC competencies (Hamilton et al., Citation2022; Hayes et al., Citation2022; Pinto et al., Citation2018; Wallace, Citation2017). Stroke IPE experiences that do not include simulations have also shown IP development (e.g., Gras et al., Citation2019), but adding a simulated patient experience allows learners to practice skills and demonstrate their roles to each other. While IPC competency frameworks may differ across countries/studies, common results that we also found include improvements in role clarification, communication, and collaborative leadership.

Considerable planning of the design, materials and delivery were done to achieve the intended learning outcomes, as well as mitigate unintended outcomes not in line with those planned (Doucet et al., Citation2014; Hafferty, Citation1998; Holmes & Mellanby, Citation2022). Design features contributing to learning included the use of a two-part simulation, the opportunity to work in the same team during both a team meeting and two different patient interactions, and the opportunity to observe and collaborate with other disciplines to provide care. This intentional design allowed students to understand how teams functioned differently base upon patient needs with varying professions taking the lead at different times, fostering both role clarity and collaborative leadership. Students’ descriptions of being in leadership roles and the sometimes-unexpected reliance on their leadership and skills support this. In addition, the strategic design of the case to highlight role contributions from the different professions, as well as where overlap and collaboration is possible, allowed for interdisciplinary collaboration. Even though the patient was not physically present during the team meeting, working together to plan an intervention within the constraints of clinical practice structures and to support patient needs and priorities facilitated collaboration. Even when the simulation with the simulated patient was canceled, this team meeting still led to intended outcomes.

Context for evaluation positivity

Our simulation was made more efficient and financially feasible in part by the co-location of learners from a variety of professional disciplines with curriculum-based interprofessional requirements together with instructors tasked with delivering their core discipline’s IPE curriculum. Our institution is home to one of the largest array of health discipline training programs. While co-location of programs provides some advantage, academic schedules across the disciplines in terms of course times, study breaks, exam periods, and holidays vary. Therefore, some programs have learned about stroke prior to both experiences while other programs have not. The interprofessional curriculum design team negotiates scheduling a year in advance, and content is deliberately selected to allow students from each participating discipline to contribute within their practice scope and learn other discipline-specific competencies related to the patient case. Learners are further supported by provision of best practice resources to review prior to these IPE events.

Although co-location simplifies some aspects of these simulations, the online portion was shown to be effective even when learners could not share an in-person learning space. Hamilton et al. (Citation2022) have demonstrated similar results when integrating learning amongst students across distinct campuses. Both the in-person and virtual stroke simulations efficiently addressed stroke care knowledge and skills, as well as IPC practice relationships. Although the knowledge content was not significantly impacted by the online delivery, differences were found in role clarification and client-centered care. Both students and the author group expressed concerns that online simulations were less effective than real-time interprofessional skill development – including, but not limited to, collaboration, trust, and best-practice care. The in-person stroke clinic was preferred as the interaction with the simulated patient, team members, and skills practice were deeper.

The importance of setting up psychological safety for the learners in a simulated learning environment cannot be emphasized enough – particularly in an IPE simulation (Holmes & Mellanby, Citation2022). This is necessary for students to fully engage in skills practice and explore the IPC competencies in a safe and supported space. To this end, we propose that our embedded design meant that the stroke IPE facilitators, each from one of the six participating disciplines, served as faculty champions of the IPE events, fostering an understanding of both the clinical and IPE learning outcomes. They created a safe learning space in both the preparation and post simulation phases, particularly if further debriefing was required. We believe that faculty champions are a necessary and key piece of the success and positive review of this stroke IPE experience. These faculty are content experts, place a high value on IPE, demonstrate enthusiasm for facilitating IPE learning, are trained in simulation, and have a high commitment to the program (Treadwell & Havenga, Citation2013).

Limitations and future directions

While our results suggest strong positive experiences for learners, there are limitations to our program and our evaluation procedures, some of which have been noted by others (e.g., Pinto et al., Citation2018). Examples include uneven numbers of learners across programs, resulting in non-uniform teams (e.g., some teams may have one learner from each discipline, where others may have two from one discipline while missing another). Of note, program enrollment dictated SLP to only 25 students while medicine, pharmacy and nursing had approximately 100. Learners in teams without an SLP student sometimes commented that they would have benefited from having an SLP to demonstrate how to communicate with a patient with aphasia. These students, however, still became aware of the importance of collaborative practice with that discipline when working with stroke patients. Ideally, each team would be comprised of learners from each discipline. While all teams were provided with resources (e.g., videos of supportive communication with people with aphasia) to support the team in absence of a particular discipline, intensive planning is underway to enhance the communication training and educational supports available to all students prior to participation in future Stroke IPE simulations.

There could be a question of a halo effect (Nisbett & Wilson, Citation1977). In the context of this IPC experience, we challenge the idea that positive effects are solely due to a halo effect. The students enrolled in this event all have previous IPE to reflect upon in evaluating this experience. Additionally, the Stroke IPE instructors with the same cohorts of students receive less favorable feedback on other learning experiences (e.g., teaching evaluations) in their respective core course evaluations within the same term and year, indicating a willingness by learners to deliver honest and constructive feedback on all experiences.

Another limitation is the study design, which uses retrospective pre-post data. This is an evaluation study rather than a controlled experiment. An experimental design would allow for further questions to be answered, e.g., the question of the halo effect. However, given that this is conducted for educational purposes rather than for research purposes, a pre-post design is within the scope of the work.

A final limitation is in the lack of evidence for sustainability of learning into practice. Our results revealed immediate positive impacts on learners from six disciplines who had the opportunity to experience collaborative stroke care using best practices; however, we do not yet know how this learning will impact future patient care. Ojelabi et al. (Citation2022) note that IPE amongst professional teams yields positive outcomes in the IP domains of communication and collaboration, but the impact on care requires further research. Our collective goal is to provide a powerful educational experience that can lead the learners to reflect upon their values and plans as future health professionals working collaboratively with their interprofessional colleagues. Wallace (Citation2017) found that SLP students reported positive impacts on their clinical skills and experiences one year after a stroke IPE workshop with seven disciplines represented. It is our hope that the IPE design provided positive IPC and socialization experiences, regardless of delivery differences during COVID-19, and will similarly influence our learners to pursue IPC practice (Schot et al., Citation2020). Impact of the stroke IPE on learners as they move into practice is an area in need of future research.

Conclusion

The IPC stroke simulations delivered virtually and in-person offer an efficient design to address stroke care content, practice skills and IPC practice relationships. With just two IPE encounters with teams from six disciplines, learners reported development in IP competencies across several domains. Learners have truly learned about, from and with each other as indicated by free-text comments. Though virtual experiences did contribute to learning, face-to-face encounters show more growth in person-centered care. Teams interacting with the purposefully designed scenarios and simulated stroke patients benefit from the realistic portrayal of actual clinical practice.

Acknowledgments

Our learners; our previous, present and future patients; Faculty of Health & Faculty of Medicine, Centre for Collaborative Clinical Learning and Research Staff (John Kyle, Technical, Doug Ferkol & Karen Bassett, Simulated Patient Educators, and Simulated Patients).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Diane MacKenzie

Diane E. MacKenzie, PhD, OT Reg. (N.S.) Associate Professor, School of Occupational Therapy, Dalhousie Faculty of Health Interprofessional Education Coordinator, and Affiliated Scientist (Research) with Nova Scotia Health.

Kaitlin Sibbald

Kaitlin Sibbald, PhD, MSc, OT Reg. (N.S.) Instructor, School of Occupational Therapy, Faculty of Health, Dalhousie University.

Kim Sponagle

Kim Sponagle, M.Ed., BscPharm, University Teaching Fellow and Associate Director, Student Affairs in the College of Pharmacy, Dalhousie University.

Ellen Hickey

Ellen Hickey, Ph.D., SLP-Reg. (NS), Associate Professor, Speech-Language Pathology, School of Communication Sciences & Disorders, Dalhousie University.

Gail Creaser

Gail Creaser, MA(Ed), BScPT, School of Physiotherapy, Dalhousie University.

Kim Hebert

Kim Hebert, MN NP Coordinator, Clinical Learning and Simulation Centre, School of Nursing, Faculty of Health, Dalhousie University.

Gordon Gubitz

Gord Gubitz, MD, FRCPC, Stroke Neurologist, Professor, Division Head of Neurology at the QEII Health Sciences Center in Halifax, and Director of the Outpatient Neurovascular Clinic. Dr. Gubitz is a member of the Executive Committee for Heart and Stroke Canadian Stroke Best Practices.

Anu Mishra

Anuradha Mishra, MD, FRCSC, Assistant Dean, Skilled Clinician Program & Inter-professional Education, Dalhousie Medicine Nova Scotia.

Marc Nicholson

Marc Nicholson, MD, FRCPC, MEd, Pediatrician, Service Learning & Interprofessional Education Program Director, Dalhousie Medicine New Brunswick.

Gordon E. Sarty

Gordon E. Sarty, P. Eng, PhD, Professor, Psychology Department Head, University of Saskatchewan, SK.

References

- Archibald, D., Trumpower, D., & MacDonald, C. J. (2014). Validation of the interprofessional collaborative competency attainment survey (ICCAS). Journal of Interprofessional Care, 28(6), 553–558. https://doi.org/10.3109/13561820.2014.917407

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Champagne-Langabeer, T., Revere, L., Tankimovich, M., Yu, E., Spears, R., & Swails, J. L. (2019). Integrating diverse disciplines to enhance interprofessional competency in healthcare delivery. Healthcare, 7(2), 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare7020075

- CIHC. (2010). A national interprofessional competency framework. University of British Columbia. https://phabc.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/CIHC-National-Interprofessional-Competency-Framework.pdf

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Doucet, S., MacKenzie, D. E., Loney, E., Godden Webster, A. L., Lauckner, H., Alexiadis Brown, P., Andrews, C., & Packer, T. (2014). Student perspectives on a community-based interprofessional education program: The intended and unintended curricular factors that acted as barriers to student learning. Journal of Research in Interprofessional Practice and Education, 42, 1–30. https://doi.org/10.22230/jripe.2014v4n2a174

- Gras, L. Z., Brown, S., Durnford, S., Fishel, S., Elich Monroe, J., Plumeau, K., & Taves, J. V. (2019). Impact of a one-time interprofessional education event for rehabilitation after stroke for students in the health professions. Journal of Allied Health, 48(3), 167–171.

- Hafferty, F. W. (1998). Beyond curriculum reform: Confronting medicine’s hidden curriculum. Academic Medicine: Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges, 73(4), 403–407. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-199804000-00013

- Hamilton, L. A., Borja-Hart, N., Choby, B. A., Spivey, C., & Shelton, C. M. (2022). Impact of a stroke interprofessional simulation on health professional students. Currents in Pharmacy Teaching and Learning, 14(8), 938–948. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cptl.2022.07.007

- Hamstra, S. J., Brydges, R., Hatala, R., Zendejas, B., & Cook, D. A. (2014). Reconsidering fidelity in simulation-based training. Academic Medicine, 893(3), 387–392. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000130

- Hayes, C., Power, T., Forrest, G., Ferguson, C., Kennedy, D., Freeman-Sanderson, A., Courtney-Harris, M., Hemsley, B., & Lucas, C. (2022). Bouncing off each other: Experiencing interprofessional collaboration through simulation. Clinical Simulation in Nursing, 65, 26–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecns.2021.12.003

- Heart and Stroke Foundation Canada. (2019). Canadian stroke best practices - rehabilitation and recovery following stroke (5th ed.). https://www.strokebestpractices.ca/recommendations/stroke-rehabilitation

- Holmes, C., & Mellanby, E. (2022). Debriefing strategies for interprofessional simulation-a qualitative study. Advances in Simulation, 7(1), 18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41077-022-00214-3

- INACSL Standards Committee, Charnetski, M., & Jarvill, M. (2021). Healthcare simulation standards of best practiceTM operations. Clinical Simulation in Nursing, 58, 33–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecns.2021.08.012

- Johnson, J. A. (2005). Ascertaining the validity of individual protocols from web-based personality inventories. Journal of Research in Personality, 39(1), 103–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2004.09.009

- Kruger, J. S., Tona, J., Kruger, D. J., Jackson, J. B., & Ohtake, P. J. (2023). Validation of the interprofessional collaborative competency attainment survey (ICCAS) retrospective pre-test measures. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 37(5), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2023.2169261

- Langhorne, P., Ramachandra, S., & Stroke Unit Trialists’ Collaboration. (2020). Organised inpatient (stroke unit) care for stroke: Network meta-analysis. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 4(4), CD000197. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD000197.pub4

- Loversidge, J., & Demb, A. (2015). Faculty perceptions of key factors in interprofessional education. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 29(4), 298–304. https://doi.org/10.3109/13561820.2014.991912

- MacKenzie, D., Creaser, G., Sponagle, K., Gubitz, G., MacDougall, P., Blacquiere, D., Miller, S., & Sarty, G. E. (2017). Preparing students for best practice collaborative stroke care: Changing knowledge and attitudes. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 31(6), 793–796. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2017.1356272

- MacKenzie, D., Doucet, S., Nasser, S., Godden Webster, A., Andrews, C., & Kephart, G. (2014). Collaboration behind-the-scenes: Key to effective interprofessional education. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 28(4), 381–383. https://doi.org/10.3109/13561820.2014.890923

- MacKenzie, D., & Merritt, B. K. (2013). Making space: Integrating meaningful interprofessional experiences into an existing curriculum. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 27(3), 274–276. https://doi.org/10.3109/13561820.2012.751900

- Morison, S., Boohan, M., Jenkins, J., & Moutray, M. (2003). Facilitating undergraduate interprofessional learning in healthcare: Comparing classroom and clinical learning for nursing and medical students. Learning in Health and Social Care, 2(2), 92–104. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1473-6861.2003.00043.x

- Nisbett, R. E., & Wilson, T. D. (1977). The halo effect: Evidence for unconscious alteration of judgments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 35(4), 250–256. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.35.4.250

- Ojelabi, A., Ling, J., Roberts, D., & Hawkins, C. (2022). Does interprofessional education support integration of care services? A systematic review. Journal of Interprofessional Education & Practice, 28, 100534. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xjep.2022.100534

- Pinto, C., Possanza, A., & Karpa, K. (2018). Examining student perceptions of an inter-institutional interprofessional stroke simulation activity. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 32(3), 391–394. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2017.1405921

- Reeves, S., Perrier, L., Goldman, J., Freeth, D., & Zwarenstein, M. (2013). Interprofessional education: Effects on professional practice and healthcare outcomes (update). The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2013(3), CD002213. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD002213.pub3

- Reeves, S., Xyrichis, A., & Zwarenstein, M. (2018). Teamwork, collaboration, coordination, and networking: Why we need to distinguish between different types of interprofessional practice. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 32(1), 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2017.1400150

- Rogers, G. D., Thistlethwaite, J. E., Anderson, E. S., Abrandt Dahlgren, M., Grymonpre, R. E., Moran, M., & Samarasekera, D. D. (2017). International consensus statement on the assessment of interprofessional learning outcomes. Medical Teacher, 39(4), 347–359. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2017.1270441

- Sahu, P. (2020). Closure of universities due to coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): Impact on education and mental health of students and academic staff. Cureus, 12(4), e7541. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.7541

- Schmitz, C. C., Radosevich, D. M., Jardine, P., MacDonald, C. J., Trumpower, D., & Archibald, D. (2017). The interprofessional collaborative competency attainment survey (ICCAS): A replication validation study. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 31(1), 28–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2016.1233096

- Schot, E., Tummers, L., & Noordegraaf, M. (2020). Working on working together. A systematic review on how healthcare professionals contribute to interprofessional collaboration. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 34(3), 332–342. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2019.1636007

- Schuwirth, L. W., & Van der Vleuten, C. P. (2019). Current assessment in medical education: Programmatic assessment. Journal Applied Testing Technology, 20, 2–10. https://jattjournal.net/index.php/atp/article/view/143673

- Secretariat on Responsible Conduct of Research. (2022). Chapter 2 – scope and approach. Tri-council policy statement: ethical conduct for research involving humans – TCPS 2. https://ethics.gc.ca/eng/tcps2-eptc2_2022_chapter2-chapitre2.html#4

- Teasell, R., Salbach, N. M., & Foley, N. (2020). Canadian stroke best practice recommendations: Rehabilitation, recovery, and community participation following stroke. Part One: Rehabilitation and recovery following stroke 6th edition update. 2019. International Journal of Stroke, 15(7), 763–788. https://doi.org/10.1177/1747493019897843.

- Thistlethwaite, J. E., Davies, D., Ekeocha, S., Kidd, J. M., MacDougall, C., Matthews, P., Purkis, J., & Clay, D. (2012). The effectiveness of case-based learning in health professional education. A BEME Systematic Review: BEME Guide No 23 Medical Teacher, 34(6), e421–e444. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2012.680939

- Treadwell, I., & Havenga, H. S. (2013). Ten key elements for implementing interprofessional learning in clinical simulations. African Journal of Health Professions Education, 5(2), 80. https://doi.org/10.7196/AJHPE.233

- Vernon, W. (2009). The delphi technique: A review. International Journal of Therapy and Rehabilitation, 16(2), 69–76. https://doi.org/10.12968/ijtr.2009.16.2.38892

- Violato, E. M., & King, S. (2019). A validity study of the interprofessional collaborative competency attainment survey: An interprofessional collaborative competency measure. Journal of Nursing Education, 58(8), 454–462. https://doi.org/10.3928/01484834-20190719-04

- Wallace, S. E. (2017). Speech-language pathology students’ perceptions of an IPE stroke workshop: A one-year follow up. Teaching and Learning in Communication Sciences & Disorders, 1(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.30707/TLCSD1.1