ABSTRACT

This paper continues the discussion about student-driven, interactive learning activities in higher education. Using object-oriented activity theory, the article explores the relational aspects of reflexive practice as demonstrated in five online discussions groups to develop students’ conceptual understanding. The purpose of the research is to describe both the process of reflection during online interaction and how practical engagement with the discipline is supported through pedagogical guidance. The students wrote short texts on the practice of health promotion ethics and discussed their perspectives in relation to theory and research. The analysis proved the importance of structural design in learning assignments to enable the cohesive and dialogic nature of interaction. Practical reflexivity is a necessary condition for enhancing the ability of professionals to question and justify critical aspects of their organisational relationships.

Introduction

Online discussion offers a flexible channel for cooperation when the purpose is to integrate multiple perspectives and construct knowledge from the field of work and education. An asynchronous, text-based form of online education ‘supports relations among the students and with teachers, even when participants cannot be online at the same time’ (Hrastinski Citation2008, 51–52). Overall, online discussions have been observed to promote the skills of critical and reflective thinking (Langley and Brown Citation2010; Mettiäinen and Vähämaa Citation2013). However, to be successful an online learning environment calls for, among other things, the construction of some common ground for developing conceptual understanding (Laurillard Citation2012, 141–161). Research shows that online discussions often lack coherence and depth if they are not adequately structured beforehand (Dennen and Wieland Citation2007; Garrison and Cleveland-Innes Citation2005; Wegerif and De Laat Citation2011; Westberry and Franken Citation2015).

This study continues the previous discussion on the theme of reflection and reflexive practices in higher education. The framework of the study is based on cultural-historical activity theory, in which the crucial basis of collective activities is the object-oriented learning related to contradictions found in everyday practice and mediated interaction with social and historical contexts that are laden with theories (Engeström Citation2001; Miettinen and Virkkunen Citation2005). Our focus is on how social and health care professionals utilise their work experiences in constructing knowledge in the commencement phase of their Master’s degree online studies. We are interested in finding out how the groups define current ethical dilemmas in health promotion in light of research knowledge and theories. Furthermore, we seek to identify critical phases of online discussion where pedagogical guidance is necessary for practical reflexivity to emerge.

There is no consensus as to whether supervised discussions are successful in supporting collective learning. For many students, online discussions have been simply the means to fulfil course requirements, as Dennen and Wieland (Citation2007) suggest. One of the issues in the online research is how the teacher instructs the discussion process. In Arvaja’s (Citation2015) study of an online university course, the structural design of the student-driven discussions was based on pedagogical guidance. The teacher planned the learning tasks related to ‘dialogic provocations’ beforehand, using diverse (also contradictory) perspectives from various philosophical texts. Reflective journals were used as tools of individual learning when the students interpreted the given texts in the light of their work experiences. The aim of the study was to analyse how the health care professionals succeeded in connecting practical and theoretical knowledge and applying the knowledge to practice during the online course. The pre-structured tasks provided an ideal context for the students to combine institutional theoretical as well as individual experience-based knowledge.

The intersubjective nature of learning was the focus of Westberry and Franken’s (Citation2015) study on collective reflection; i.e. the activity theory based process of object-oriented learning in two student-driven online groups in tertiary education. According to the chosen approach, the learning tasks were conceptualised as constructed objects, i.e. the students uploaded a short text (an introductory paragraph or a report) to the online forum and gave written feedback on each others’ texts. The tasks were supposed to steer the pedagogical activity without the teacher’s presence. However, in the first group the object of learning was represented by the teacher in two different, even conflicting, ways. While dialogic interaction was generally favoured, the teacher defined the learning object as monologue in the official course documents, highlighting the individual criteria of evaluation. Accordingly, the students adopted the individual approach instead of building shared conceptual understandings with their peers. Also, in the other group the lecturer’s and tutors’ conflictual refrainment from giving feedback favoured individual performance. According to researchers it is possible to overcome pedagogical distance between the codified curriculum plan and its actual enactment by guiding students’ interpretation and construction of learning objects. Possible ways to increase the student understanding of the object are course outlines, website instructions, and teacher feedback (Westberry and Franken Citation2015).

Gorli, Nicolini, and Scaratti (Citation2015) implemented a large intervention project in healthcare with the aim of developing tools and methods which would strengthen the link between reflexive work and authoring in the organisational context. The researchers regarded reflection as a social and collective concept, connecting it with the idea of practical reflexivity. In other words, they extended the concept of reflexivity to include also taken-for-granted practices, features, actions, discourses, and shared knowledge in organisations. In particular, reflection of challenging and complex issues (i.e. learning objects), directed the discussion towards more actionable ideas. The researchers emphasised the difference between authorship and authoring processes, seeing authoring as a more dynamic process, whereas authorship is brought to critical consciousness in organisational contexts. In addition, it was learned that the enhancement of practical reflexivity is strengthened both by the activities of facilitators and by tools – like reflexively questioning – requiring the collective exploration of organisational practices and relationships.

Reflexivity defined

The concepts of reflexivity and reflection have been linked with each other in pedagogical contexts of higher education (Cunliffe Citation2004; Dyke Citation2009). With regard to reflection, the individual perspective has been criticised by organisational researchers who stress the need to define the concept in a broader sense as a core process of social, collective or organisational learning activity (Høyrup Citation2004; Høyrup and Elkjaer Citation2006; Vince Citation2002). While the individual perspective of reflection has, in research, referred to sharing personal experiences and beliefs with the aim of perspective change in practice (e.g. Adamson and Dewar Citation2015; Vachon, Durand, and LeBlanc Citation2010), the organisational perspective of reflection has focused on dealing with and questioning taken-for-granted assumptions, alternatives and social relations in social systems (Allen Citation2014; Leppa and Terry Citation2004). In this journal and elsewhere, reflexivity has been distinguished from forms of reflection in terms of its focus on the self and one’s assumptions on the constraints of various realities (Garnett and Vanderlinden Citation2011; Matthews and Jessel Citation1998), by exploring the developmental process of reflexivity of professional identity in the social context of groups (Burke and Dunn Citation2006; Ryan and Carmichael Citation2016), or by being linked to dialogical and relational activity to unsettle conventional practices (Gorli, Nicolini, and Scaratti Citation2015).

Hence, as a context-bound and cyclical concept reflexivity offers a structural perspective within an organisational context, including a component of reflection (Dyke Citation2009; Ryan and Carmichael Citation2016). For instance, reflexivity has been a premise in Smith’s (Citation2011) model of critical reflection and Dyke’s (Citation2009) framework for reflexive learning. Both researchers link a variety of experiential and reflective learning with reflexivity, seeing it fundamentally as a social process: knowledge created in interaction with others. In Smith’s model the reflection process yields a critical perspective when any ethical, political or social issues encountered in professional practice are made explicit. Conversely, Dyke (Citation2009) criticises the individual approach to reflexivity and highlights the importance of questioning the complexities of situated practices as the first experience of reflexivity (see Fenwick Citation2014). According to Dyke (Citation2009), a key element in understanding reflexive learning is critical engagement with theory. However, a reflexive model for education is not linear but provides flexible learning possibilities for participants (Dyke Citation2009; Smith Citation2011).

Practice-based approach to relational activity

A theoretical framework for reflexivity is offered by the practice-based approach (Fenwick Citation2014; Nicolini, Gherardi, and Yanow Citation2003). The practice-based activity theory underlines the participants’ internal viewpoints, based on practical problems and scientific or experience-based attempts to solve these problems, arising from the organisational context. These theories underline the connection of meaning making with activity, and see the contradictions, manifested as dilemmas, problems, tensions and developmental possibilities as a central source of knowledge construction (Engeström Citation2001, Citation2015; Miettinen Citation2000). The introduction of critical viewpoints, and their development through dialogue, is the central feature of practice-based approaches. However, for the dialogue to evolve, the participants must have some common understanding of the domain under discussion.

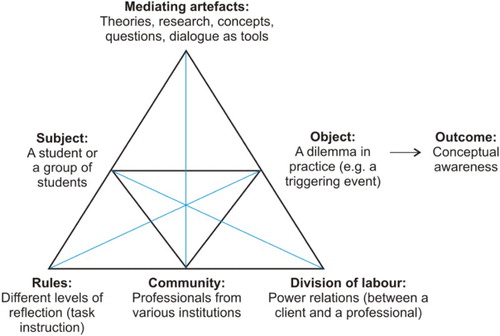

In activity theory, the prime unit of analysis is the object-oriented and artifact-mediated collective activity system (Engeström Citation2015, see ). The object refers to the problem space (e.g. a triggering event) which the activity is directed towards and about which people can express their views. It is also part of social and cultural factors, of which people have experience and knowledge and about which they have the possibility of attaining more information (Vygotsky Citation1978). Activity theory emphasises the systemic nature of organisations, and the reflexive role of artefacts and tools (theories, concepts, dialogue, etc.) by means of which the object is transformed into outcomes (conceptual awareness, self-regulation). Furthermore, the rules refer to the explicit and implicit regulations, norms and conventions that constrain interactions within the organisation. The community comprises multiple participants who share the same object and the division of labour refers to the community and the vertical division of power between participants (Engeström Citation2001, Citation2015).

Activity theory provides a holistic approach to analysing the core organising processes through which commitment to collective activities is supported (Blackler and McDonald Citation2000) because it emphasises the interaction between the various elements within the system (Engeström Citation2015). In this framework, reflection is seen as an organising process of joint activities supporting structured and systematic interaction. Reflective skills are necessary to enhance reflexive awareness at the individual and collective level. Raeithel’s (Citation1983, Citation1996) metacognitive model of reflection is based on the relational concept of the self, meaning that cooperation is integrated with the contextual factors that lead to the integration of practice, and the enhancement of collective awareness. According to Raeithel (Citation1983), knowledge is transferred, transformed and created through interaction. He characterises the structure of shared knowledge as having three components of reflection: centration (individual), decentration (situational) and the highest mode, recentration (collective).

Centration refers to the premise of reflection, the initial stage of individual awareness where the person is becoming aware of the structure of the reality – although the action is not yet conscious. Centration concerns one’s own performance in a given task or social situation. However, Raeithel underlines the importance of outward orientation in dealing with a common task or problem. In decentration the activity with its object and necessary tool is important. As a result the interaction develops into a social process, as an object of ‘our’ shared interest rather than an individual one. The final level of collective reflection directs a group’s attention not only to a common task or action and its social and historical context in order to develop change but also to the dynamics of the organisation. Collective reflection yields a new perspective of some kind, which increases collective awareness of the system as a whole (Engeström Citation2004; Raeithel Citation1983).

In the context of higher education, there is not much research related to how students recognise the institutional, organisational, discursive, and social conditions influencing their patterns of performance and thought (Fenwick Citation2014). Important question is how local, practical knowledge is integrated with theoretical research knowledge. Further, there is a lack of analyses regarding reflexive knowledge transformation processes in online contexts. This study is an attempt to fill this gap, for its part, by investigating three research tasks: (1) to what extent did the levels of reflection emerge in online discussion, (2) why does reflection deepen or break down during the discussion, and (3) how is the reflexive practice supported through pedagogical guidance in the critical phases of online discussion.

Methods

Data collection

The data consisted of five online discussions as part of a Master’s degree programme and it was collected at a University of Applied Sciences in southern Finland in 2011 (Curriculum Citation2011–2012). The course on ethical questions of health promotion lasted three weeks and involved 25 students divided into groups of five students who already held a Bachelor degree in social work, nursing, or physiotherapy and at least three years of work experience in their respective fields. The students were studying on a part-time basis, expecting to complete their Master’s degree in 1.5 to 2.5 years. The graduate studies comprised both contact teaching, as well as distance-learning assignments and online studies. The online course was implemented in the commencement phase of the interdisciplinary studies and the objective of the course was that the students would be able to evaluate the ethical basis of health promotion.

Each group chose a topic of interest for their discussions and specified it within the professional practice. Three groups focused on ‘Human responsibility and the right to decide on one’s lifestyle – reflection on human autonomy in lifestyle issues’, while two groups selected the topic of ‘The responsibility and wielding of power by social and health care staff in health promotion settings’. The discussion process was instructed, but not guided from outside. It was hoped that discussion would include a reflective exchange of ideas, which would integrally involve critical argumentation, the presentation of additional and supplementary questions, and analysis of arguments and concepts. A research bibliography related to the six national research publications of health promotion ethics was delivered to the groups, but the students were also free to search for some extra references in support of their discussions. Each group chose a member to enter the selected topic and specify it on the discussion platform. Students’ contributions to the online discussions were dated and labelled, showing the theme and who was replying to whom. The accumulated postings amounted to 54 pages of text.

Data analysis

The data analysis was based on a qualitative data design suitable for content and discourse analysis (DA). In qualitative content analysis, the basic issue is to decide whether the analysis should focus on manifest (the visible, obvious components) or latent (relationship aspects of underlying meaning) content (Graneheim and Lundman Citation2004). The content analysis of the levels of reflection was theory-driven (obvious components of the levels of reflection e.g. Raeithel Citation1983). Analysis of the cohesion of online discussions was based on discourse analysis proposed by Gee and Green (Citation1998), where the basis of discourse is a recognition of the sociocultural nature of discourse, social practice and learning. Bakhtinian dialogue approach was used as a means of exploring the perspective of reflexivity, i.e. the speaker-hearer relationship, where the focus lies on interpretation and meaning construction (Gee and Green Citation1998).

Dialogic analysis integrated with the above-mentioned discourse framework because relational reflexivity is predicated on dialogic activities. According to activity theory, object-related activities with their organisational tensions are considered the starting point of Bakhtinian critical dialogue (Janhonen and Sarja Citation2000; Matusov Citation2015; Oswick et al. Citation2000). The analysis was also, broadly speaking, complemented by Blackler and McDonald’s (Citation2000) approach to institutionalised power relations. Thus, the analysis framework for this study was chosen not from the research data but from the main components of reflexive practice. Analysis of the group discussions went through a number of phases, as illustrated in .

Table 1. Analysis framework for the phases of online discussions.

In line with confidence criteria (Patton Citation2015; Pope and Mays Citation2006), the orientation phase of analysis proceeded through the steps of reading and re-reading the transcripts, and of classifying different categories and connections across them. The classification frame was composed of three metacognitive levels suggested by Raeithel (Citation1983): individual, situational and collective reflection (more detail can be found in the Findings section). The relevant unit of analysis was an individual student’s ideational comment (N = 107), classifiable as such within the predefined frame and regarded as part of a chain of comments. The distribution of the levels of reflection was presented as an outcome.

In the theory-driven content analysis phase, our main interest was in exploring how the data related to the theoretical framing of the study (the activity theory). The primacy of practice with its complexities, i.e. everyday situated actions, was the premise for instigating situational reflection, meaning collective exploration of organisational practices and relationships. Discourse analysis based on the features of critical dialogue involved a shared object of learning (an ethical dilemma, triggering event etc.) which the participants agreed to discuss. Intersubjective understanding of the chosen conceptual dilemma was constructed through dialogic exchanges; that is, through connections with other contributions. Finally, some new conceptual understanding may be produced, in turn promoting reflexive awareness, i.e. an authorial approach to work (cf. Gorli, Nicolini, and Scaratti Citation2015; Matusov Citation2015).

As an indication of the depth of the analysis it should be noted, for example, that as the process went on the categorisation structure was simplified by abandoning some data, such as classifications that were complementary to each other (e.g. dialogue and knowledge types).

For the sake of confirmability – i.e. to illustrate that the chosen framework was exhaustive and mutually exclusive – authentic data samples (translated from Finnish) are presented in this article. Online discussions also included comments of no relevance to the topic concerned. Such comments were excluded from the analysis.

The authors obtained permission to conduct the research project from the respective Institutional Review Boards concerned, each of which gave ethical approval for the research. The Ethical Committee manages and monitors the ethical issues of the university’s studies. The students taking part in the courses gave their permission for the analysis of their online discussions for research purposes. Confidentiality issues were agreed upon verbally in a separate information session arranged for the participants by one of the authors. Participants’ anonymity was guaranteed by the researchers, who emphasised the voluntary nature of participation.

Findings

Before describing the reflexive practice in online discussions, the findings reported here have been quantified in order to illustrate the distribution of students’ comments across the reflection levels. The theory-driven categorisation of online discussions was based on a classification frame composed of three metacognitive levels, as shown in .

Table 2. Components of reflexive practice in group discussions.

Reflection levels of each online discussion

The online discussions about the ethics of health promotion practice included 107 comments altogether. The amount of comments varied between the groups. In general, there were more comments in groups 1 (n = 31, 29%) and 5 (n = 29, 27%), while the number of comments was lower in groups 2 (n = 19, 18%), 3 (n = 16, 15%) and 4 (n = 12, 11%) respectively. The reflection levels for each group are presented as percentages in .

Figure 1. Online discussion viewed as an activity system (adapted from Engeström Citation2015).

Overall, students’ comments featured almost equal frequencies for individual reflection (n = 47; 44%), situational reflection (n = 48; 45%), and collective reflection (n = 12; 11%). Within the groups, the comments were divided as follows, based on the differences between reflection levels. Individual reflection and situational reflection was common in all groups. The majority of the comments classified as individual reflection were in group 1 (n = 16, 52%), while in the other groups, individual reflection was about half of the amount, from seven to nine comments. Situational reflection was common in groups 1 (n = 14), 5 (n = 13), and 2 (n = 12). In groups 1, 3, and 5, the comments included all levels of reflection: individual, situational, and collective, whereas in groups 2 and 4, collective reflection was missing and group 1 included only one comment with collective-level reflection. Situational reflection was most frequent in group 2 (n = 12; 63%) and the percentage of collective reflection was highest in groups 5 (n = 8; 27.5%) and 3 (n = 3, 19%).

Next, we were interested in finding out what kind of issues either prevented or promoted the deepening of the level of reflection from individual to collective reflection. Transitions that hindered the enhancement of dialogic relationships were related to the theme, process and quality of interaction. Often, comments were not connected to the outlined theme or previous contributions but instead dealt with isolated daily routines or cited researchers’ notions in a straightforward manner without pondering their connections to the grounds of ethical decision-making. Our interest also concerned how reflexive practice was supported through pedagogical guidance in the critical phases of online discussion.

Reflexive practice is not a basis for reflection

Ethical dilemma in practice was not defined

Two online discussions (groups 2 and 4) concerned ‘Human responsibility and the right to decide on one’s lifestyle’. In these groups the discussion started to meander from one issue to another, and in a routine-like manner the participants produced the sufficient number of comments without connecting to previous contributions. The students did not identify any specific ethical dilemma in practice where they felt some need for change, as the object of their discussion (Dyke Citation2009; Fenwick Citation2014). They preferred to express their views on the chosen topic – the client’s personal autonomy – through their experiences in the form of personal stories, episodes from work or unrelated quotations from given references. The prevalence of individual reflection supports the findings of earlier research (Adamson and Dewar Citation2015; Mettiäinen and Vähämaa Citation2013; Westberry and Franken Citation2015).

In the course of discussion, situational reflection meant dealing with the concept of autonomy from different perspectives or questioning the routine-like patterns of behaviour adopted in their organisations. Sequences of connected talk and action were classified as a tool for generating relational reflexivity (Gee and Green Citation1998). The participants might refer to each other’s comments; however, they did not always introduce any complementary or contrasting contributions or any theoretical knowledge connected with those comments. The contributions often finished with a reflective or open question, and a sense of community was maintained at a discourse level with the use of the phrase ‘I agree with the previous comment’.

Student 5: I was watching the programme ‘Seventh Heaven’, where people talked about narcissism and related family violence. Isn’t it so that a lifestyle covers all this how spouses treat each other and their children?

Student 3: I, too, refer to the same programme. This became an awkward transition from the impact of socio-economic status and narcissism to our own welfare and that of our closest ones. We have a top-quality system of maternity and child health clinics. Would there be a reason to invest even more in the info given by these clinics?

Student 4: As a father of three children, we have visited a child health clinic numerous times. I can’t recall even a single thing we would have discussed there or for which I would have gotten some advice. … As far as nourishment is concerned, it’s true that socioeconomic status defines what people eat.

Common ethical dilemma was ignored

Discussion group 1 chose the topic ‘The responsibility and wielding of power by social and health care staff in health promotion settings’. In the opening phase, the known ethical dilemma related to the financial exploitation of older patients was proposed by a student as a possible object of learning. In order to deepen the level of reflection by exploring the organisational, social and individual bases of their actions, the group should have reconstructed this holistic organisational issue from multiple perspectives (cf. Leppa and Terry Citation2004). Instead, object-oriented discussion was ignored in subsequent contributions, as professionals started to describe various projects implemented in their organisations. Because of the complexity of the known (inherent) dilemma, participants were unwilling to explore the organisational relations in the given situation through conceptual knowledge. Here a sense of community was again created at a discourse level by dialogic exchanges, but the opportunity presented by the efforts of a student to move the dialogue to the institutional ethical dilemmas was not grasped.

Student 2: In meetings where a patient’s discharge was considered, we often faced the fact that the patient’s condition and functional abilities called for staying in institutional care. Yet, a relative was insisting on discharge. Sometimes it was clearly evident that such demands were made in the hope of exploiting the patient financially. This way, the relative got a chance to seize the patient’s pension. Financial exploitation of elderly people is hard to prove. Primarily, the problem is that personnel in different sectors have become cynical in their work. In particular, today’s differentiated sectors take care of only their own.

Student 4: As an awkward transition to the previous comment, I could tell you about the model used in our community. The purpose of the open collaboration model for early intervention (Varpu) used in our municipality is to respond to the needs of children and families at an early stage. The model integrates cooperation between different sectors and clients in occupational welfare services. For the elderly, we have the Ehko project.

Towards practical reflexivity

Practical reflexivity was constructed in dialogues where collective reflection, meaning the orientation towards the object-oriented activity, its developmental context and exploration of the internal dynamic of organisation (Raeithel Citation1983), was dominant. The topic of group 3 concerned ‘The responsibility and wielding of power by social and health care staff in health promotion settings’. In the initial stage of discussion, the group’s outward orientation was stimulated by offering a real ethical dilemma with two provocative headlines about power wielded in practice by nurses over their patients. The research knowledge (two contrary concepts) was used as a tool to validate dealing with the presented example as an organisational level issue (student 2). This statement is congruent with Dyke’s (Citation2009) framework, where one key element of reflexivity is critical and open engagement with theory.

Importantly, organisational power relations, the assumptions that underpin organising processes and professional-client relations were brought to light in the next contribution, by student 3. The contribution is concluded by a collective-level reflexive question, again based on research knowledge. It is clear that the organization-level comment enables collective reflection on the ethical grounds of decision-making in a health promotion context, as demonstrated by the next comment (student 4). The concept of power is defined as a focus of collective reflection. Here, critical dialogue constructs intersubjective sense-making when institutionalised power relations are linked with the authoritative model of action (cf. Blackler and McDonald Citation2000). As an outcome of collective reflection, a conceptual awareness of the activity system as a whole starts to develop. Routinised work practices are questioned when student 6 argues for the importance of critical reflection in recognising elements of wielding power in themselves. Finally, shared knowledge construction is crystallised in the form of the concept of empowerment.

Student 1: (Two examples from health practice!) Would it still be good to open up the concept of power and how it is wielded by nurses over their patients? If power is the ability to reach desired goals (Palokangas), doesn’t it then mean that the critical point here is the ethicalness of the goals? So it’s worth considering whether wielding of power can also have some positive aspects in non-voluntary care settings? What I’m trying to ponder here is the setting of good power/evil power. (Outlining the object of discussion)

Student 2: An interesting point of view and issue to consider. The results of a literature review indicated that power has been studied from several perspectives, but few studies as an organizational-administrative issue.

Student 3: A really interesting viewpoint. Will the definition of good power change according to the agent or the object? The publication entitled ‘XXX’, leads us to consider the point whether people have the right to end their own lives and whether care personnel have the right to prevent this by using their power? (Outlining the object of discussion)

Student 4: Good power has been touched upon in previous writings. I make decisions on patients’ behalf on, often against the patient’s own will. This kind of power is situational. Many things justify the exercise of power, but also restrict it. According to the study by Palokangas, ‘power or responsibility is based on an authoritative relationship (Wrong), which places a health care client in an inferior position in relation to professional staff.’ In the hospital world, this setting is deep-seated and health promotion is based on this type of guidance. Indeed, where is the line for professional staff’s power to make decisions on behalf of others? Is good power based on everyone’s personal view about right and wrong, general norms, and ethics?

Student 6: In Syrjäpalo’s dissertation on psychiatric care, the staff don’t consider wielding of power to be included in motivation for nurse’s work. A patient’s mistreatment can therefore be sometimes because the nurses don’t recognise in themselves the elements of wielding of power and are thus unable to promote professionalism in their own work. Who defines what is good and what is evil in this dynamic era, where individual’s values may be emphasised at the expense of the community?

Student 2: It is omnipotent to think that help depends on the professional only, when it is perhaps a matter of empowerment after all. Empowerment is a personal and social process arising from the person him/herself, which is defined by goals, ability, beliefs, contextual beliefs, and emotions as well as the internal relationships of these (Siitonen).

Student 3: At social work you see many people who are outpatients. They are responsible for taking any medicine they may be given and for taking part in psychotherapeutic care contacts. This is a question of client autonomy. It is important to think about how you motivate the client and how you deal with the kind of patient who decides not to take part in care. … Well, autonomy means that one may decide about one’s own matters and choices. Who or what does define what is good for a client? In the book ‘XXX’ (Pursiainen), an individual’s good is what he or she him/herself chooses for his/her own good. Is the issue so explicit, however? (Outlining the object of discussion)

Student 1: I think as social and health care professionals we should look at the issues in a larger context! Why do people eat too much or why do they use intoxicants unreasonably? In his book, Lindqvist considers care staff’s ethics and care organisations’ humanity from many perspectives. Would we wish ourselves that some outsider decides on our lives and how would it feel in reality?

Student 3: Yet, professionals should aim towards a preventive approach in their work and they should take up health-related issues when working with clients. However, how should the professionals go about it so as to account for everyone’s autonomy in the encounter?

Student 4: I will summarise about all the issues we have already discussed. We have used literature more than they wished us to in the instruction. I ask, what would be a useful way for us to deal with this theme? (Redefining the object of discussion)

Student 1: I propose that we first deal with people’s own responsibility for their lives and actions. For example, in the Stakes publication ‘XXX’, it is suggested that for the increasing health care costs we should seriously consider a model where those neglecting their own health would be made to pay for at least a part of the treatment of their illnesses themselves.

Student 5: Solely from an economic point of view, that would indeed be reasonable. From a humane perspective, the model would be problematic. Health and lifestyle are not explicitly measurable. … Surely, society could support the adoption of healthy lifestyles. … For example, according to a study, sugar taxation would substantially decrease overweight, type II diabetes, and coronary artery disease. Therefore, merely informing people about healthy nourishment is not enough, but it would be wise also to steer people’s choices by economic means.

Student 3: Järvi stresses that clients need long-standing support and guidance in their lifestyle changes. Clients should be directed to inexpensive hobbies, so that poorer people can also afford it. In all, health education should be provided in an encouraging manner, not through a sense of guilt.

Discussion

Our purpose has been to describe how student-driven online discussion promotes knowledge integration and transformation processes. Here, different levels of reflection were analysed with groups of undergraduate students with work experience. The majority of comments analysed were based either on individual (44%) or situational (45%) reflection. In accordance with earlier research, individual reflection was descriptive and concerned either one’s personal experiences, or was solely based on research literature, or opinion pieces (cf. Adamson and Dewar Citation2015; Mettiäinen and Vähämaa Citation2013). The meaning of complex issues in their situational practice was related to the development of joint activities at the level of outward oriented situational reflection. The shift to the collective reflection (11%) where the internal dynamic of the work organisation, its developmental context and a shared ethical issue defined the discussion, was not very common.

First, structuring of the online discussion enables the depth of learning, the linking of complementary knowledge. In this research, the learning task was introduced as broad discussion topics by the teacher. After the selected topic was initiated, participants were asked to explore the presented dilemma by providing comments, arguments, questions, alternatives or summaries based both on their experience and any literature they had read. Previous research shows that educational experience needs to be structured through activating tools of inquiry (dialogic provocations, engaging questions, contracting cases or statements and so on) to enable collective reflection (Arvaja Citation2015; Laurillard Citation2012; Leppa and Terry Citation2004). For instance, Dyke (Citation2009) suggests the use of computer-mediated conferencing (e.g. live video links to practice situations) as a means of delivering reflexive learning from practice. Also, the visual modelling of inter-professional group activities has offered a tool for the enhancement of practical reflexivity (Sarja et al. Citation2012).

Second, object-oriented discussion is the necessary for dialogic relationships to develop. Health promotion ethics, as well as the definition and concepts of health promotion, have been found to be problematic due to the necessary value considerations involved (Carter Citation2014). However, problems that are complex or authentic situations are required to study conflicting practices from the point of theoretical, research-based knowledge (Vachon, Durand, and LeBlanc Citation2010). In activity theory, knowledge of the world of external objects is not reduced to an individual’s reflection about the self and its assumptions underpinning academic practices; instead, groups construct their everyday practice and reflexion emerges in the course of joint activities with systems of objectified forms of external knowledge (Lektorsky Citation1985). Consequently, a clearly defined object-related discussion and continuous reference to the object during the process leads in an ideal case to self-regulation at the individual or group level (Raeithel Citation1996).

Finally, there is no consensus on how the strengthening of reflexive practice ought to be guided in online discussion fora. In this research, the teacher did not guide the ongoing discussion; the constant evaluation of online activities takes considerable time. The inclusion of guidance also poses a risk in that the teacher might indirectly deliver knowledge or offer answers to problems for which there is no single right answer (cf. Westberry and Franken Citation2015). The finding of students’ weak engagement in object-oriented discussions without pedagogical guidance are consistent with those of earlier online research (Dennen and Wieland Citation2007; Garrison and Cleveland-Innes Citation2005; Wegerif and De Laat Citation2011). Our findings also agree with those of Allen (Citation2014), in showing that professionals in health care organisations are not necessarily used to dealing with relational issues beyond the boundaries of their local practice.

Conclusions

The results show the importance of constituting an authorial object of learning in practice to which students are willing to commit and demonstrate their theory-laden experiences. Practical reflexivity is the point of departure for the deepest level of collective or critical reflection. While collective reflection becomes a prerequisite in searching for shared conceptual awareness or understanding, critical dialogue enables the students to recognise the complex ethical and professional issues involved. In the current research, reflexive practice has been conceptualised as individuals’ ability to consider themselves in relation to their social context. In this research, reflexive practice is conceptualised as collective awareness of making sense of and shaping the organising structures that create and maintain authoritative power relations. Consequently, various organisational dilemmas and tensions have to become apparent and as the object of their learning. We argue that when the students commit to transform their conceptual understanding through collective and critical reflection, they will be able to strengthen their organisational authorship as responsible professionals in their challenging organisational practices and relationships.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Adamson, E., and B. Dewar. 2015. “Compassionate Care: Student Nurses’ Learning Through Reflection and the Use of Story.” Nurse Education in Practice 15 (3): 155–161. doi:10.1016/j.nepr.2014.08.002.

- Allen, D. 2014. “Re-conceptualising Holism in the Contemporary Nursing Mandate: From Individual to Organisational Relationships.” Social Science & Medicine 119: 131–138. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.08.036

- Arvaja, M. 2015. “Experiences in Sense Making: Health Science Students’ I-positioning in an Online Philosophy of Science Course.” Journal of the Learning Sciences 24 (1): 137–175. doi:10.1080/10508406.2014.941465.

- Blackler, F., and S. McDonald. 2000. “Power, Mastery and Organizational Learning.” Journal of Management Studies 37 (6): 833–852. doi: 10.1111/1467-6486.00206

- Burke, J. P., and S. Dunn. 2006. “Communicating Science: Exploring Reflexive Pedagogical Approaches.” Teaching in Higher Education 11 (2): 219–231. doi:10.1080/13562510500527743.

- Carter, S. M. 2014. “Health Promotion: An Ethical Analysis.” Health Promotion Journal of Australia 25 (1): 19–24. doi:10.1071/HE13074.

- Cunliffe, A. L. 2004. “On Becoming a Critically Reflexive Practitioner.” Journal of Management Education 28 (4): 407–426. doi:10.1177/105256290426440

- Curriculum. 2011–2012. Degree Programme in Health Promotion: Regional Development and Management. Helsinki: Laurea University of Applied Sciences.

- Dennen, V. P., and K. Wieland. 2007. “From Interaction to Intersubjectivity: Facilitating Online Group Discourse Processes.” Distance Education 28 (3): 281–297. doi:10.1080/01587910701611328.

- Dyke, M. 2009. “An Enabling Framework for Reflexive Learning: Experiential Learning and Reflexivity in Contemporary Modernity.” International Journal of Lifelong Education 28 (3): 289–310. doi:10.1080/02601370902798913.

- Engeström, Y. 2001. “Expansive Learning at Work: Toward an Activity Theoretical Reconceptualization.” Journal of Education and Work 14 (1): 133–156. doi:10.1080/13639080020028747.

- Engeström, Y. 2004. Ekspansiivinen Oppiminen ja Yhteiskehittely Työssä [ Expansive Learning and Co-configuration in Work]. Tampere: Vastapaino.

- Engeström, Y. 2015. Learning by Expanding: An Activity-theoretical Approach to Developmental Research. 2nd ed. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Fenwick, T. J. 2014. “Assessment of Professionals’ Continuous Learning in Practice.” In International Handbook of Research in Professional and Practice-based Learning, edited by S. Billett, C. Harteis, and H. Gruber, 1271–1297. Dordrecht: Springer. doi: 10.1007/978-94-017-8902-8_46

- Garnett, R. F., and L. K. Vanderlinden. 2011. “Reflexive Pedagogy: Disciplinary Idioms as Resources for Teaching.” Teaching in Higher Education 16 (6): 629–640. doi:10.1080/13562517.2011.570444.

- Garrison, D. R., and M. Cleveland-Innes. 2005. “Facilitating Cognitive Presence in Online Learning: Interaction Is Not Enough.” American Journal of Distance Education 19 (3): 133–148. doi:10.1207/s15389286ajde1903_2.

- Gee, J. P., and J. L. Green. 1998. “Discourse Analysis, Learning, and Social Practice: A Methodological Study.” Review of Research in Education 23: 119–169.

- Gorli, M., D. Nicolini, and G. Scaratti. 2015. “Reflexivity in Practice: Tools and Conditions for Developing Organizational Authorship.” Human Relations 68 (8): 1347–1375. doi:10.1177/0018726714556156.

- Graneheim, U. H., and B. Lundman. 2004. “Qualitative Content Analysis in Nursing Research: Concepts, Procedures, and Measures to Achieve Trustworthiness.” Nurse Education Today 24 (2): 105–112. doi:10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001.

- Høyrup, S. 2004. “Reflection as a Core Process in Organisational Learning.” Journal of Workplace Learning 16 (8): 442–454. doi:10.1108/13665620410566414.

- Høyrup, S., and B. Elkjaer. 2006. “Reflection: Taking it Beyond the Individual.” In Productive Reflection at Work: Learning for Changing Organizations, edited by D. Boud, P. Cressey, and P. Doherty, 29–42. New York: Routledge.

- Hrastinski, S. 2008. “Asynchronous and Synchronous E-learning.” EDUCAUSE Quarterly 31 (4): 51–55. https://net.educause.edu/ir/library/pdf/eqm0848.pdf

- Janhonen, S., and A. Sarja. 2000. “Data Analysis Method for Evaluating Dialogic Learning.” Nurse Education Today 20 (1): 106–115. doi: 10.1054/nedt.1999.0370

- Langley, M. E., and S. T. Brown. 2010. “Perceptions of the Use of Reflective Learning Journals in Online Graduate Nursing Education.” Nursing Education Perspectives 31 (1): 12–17.

- Laurillard, D. 2012. Teaching as a Design Science: Building Pedagogical Patterns for Learning and Technology. New York: Routledge.

- Lektorsky, V. A. 1985. Subject Object Cognition. Moscow: Progress Publishers.

- Leppa, C. J., and L. M. Terry. 2004. “Reflective Practice in Nursing Ethics Education: International Collaboration.” Journal of Advanced Nursing 48 (2): 195–202. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03187.x.

- Matthews, B., and J. Jessel. 1998. “Reflective and Reflexive Practice in Initial Teacher Education: A Critical Case Study.” Teaching in Higher Education 3 (2): 231–243. doi:10.1080/1356215980030208.

- Matusov, E. 2015. “Comprehension: A Dialogic Authorial Approach.” Culture & Psychology 2 (3): 392–416. doi:10.1177/1354067X15601197.

- Mettiäinen, S., and K. Vähämaa. 2013. “Does Reflective Web-based Discussion Strengthen Nursing Students’ Learning Experiences During Clinical Training?” Nurse Education in Practice 13 (5): 344–349. doi: 10.1016/j.nepr.2012.09.012

- Miettinen, R. 2000. “Varieties of Constructivism in Education. Where Do We Stand?” Lifelong Learning in Europe 7 (1): 41–48.

- Miettinen, R., and J. Virkkunen. 2005. “Epistemic Objects, Artefacts and Organizational Change.” Organization 12 (3): 437–456. doi:10.1177/1350508405051279.

- Nicolini, D., S. Gherardi, and D. Yanow. 2003. “Introduction: Toward a Practice-based View of Knowing and Learning in Organizations.” In Knowing in Organizations: A Practice-based Approach, edited by D. Nicolini, S. Gherardi, and D. Yanow, 3–31. Armonk: Sharpe.

- Oswick, C., P. Anthony, T. Keenoy, and I. L. Mangham. 2000. “A Dialogic Analysis of Organizational Learning.” Journal of Management Studies 37 (6): 887–902. doi: 10.1111/1467-6486.00209

- Patton, M. Q. 2015. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods. 3rd ed.Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Pope, C., and N. Mays. 2006. Qualitative Research in Health Care. London: BMJ Books.

- Raeithel, A. 1983. Tätigkeit, Arbeit und Praxis: Grundbegriffe für eine praktische Psychologie [ Activity, Work and Practice: Basic Concepts for a Practical Psychology]. Frankfurt: Campus.

- Raeithel, A. 1996. “On the Ethnography of Cooperative Work.” In Cognition and Communication at Work, edited by Y. Engeström, and D. Middleton, 319–339. Cambridge: University Press.

- Ryan, M., and M.-A. Carmichael. 2016. “Shaping (Reflexive) Professional Identities Across an Undergraduate Degree Programme: A Longitudinal Case Study.” Teaching in Higher Education 21 (2): 151–165. doi:10.1080/13562517.2015.1122586.

- Sarja, A., S. Janhonen, P. Havukainen, and A. Vesterinen. 2012. “Modelling in Evaluating a Working Life Project in Higher Education.” Studies in Educational Evaluation 38 (2): 55–64. doi: 10.1016/j.stueduc.2012.06.001

- Smith, E. 2011. “Teaching Critical Reflection.” Teaching in Higher Education 16 (2): 211–223. doi:10.1080/13562517.2010.515022.

- Vachon, B., M. J. Durand, and J. LeBlanc. 2010. “Using Reflective Learning to Improve the Impact of Continuing Education in the Context of Work Rehabilitation.” Advances in Health Sciences Education 15 (3): 329–348. doi:10.1007/s10459-009-9200-4.

- Vince, R. 2002. “Organizing Reflection.” Management Learning 33 (1): 63–78. doi: 10.1177/1350507602331003

- Vygotsky, L. S. 1978. Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Wegerif, R., and M. De Laat. 2011. “Using Bakhtin to Re-think the Teaching of Higher-order Thinking for the Network Society.” In Learning Across Sites: New Tools, Infrastructures and Practices, edited by S. Ludvigsen, A. Lund, I. Rasmussen, and R. Säljö, 313–329. New York: Routledge. Retrieved from http://www.earli.org/resources/Publications/Learning%20Across%20Sites.pdf

- Westberry, N., and M. Franken. 2015. “Pedagogical Distance: Explaining Misalignment in Student-driven Online Learning Activities Using Activity Theory.” Teaching in Higher Education 20 (3): 300–312. doi:10.1080/13562517.2014.1002393.