ABSTRACT

Trust is essential in any kind of peer-based mentoring. Taking a sociocultural view, this study focuses on how trust emerges relationally in a higher education context where colleagues observe and give feedback on one another's teaching. The term peer mentoring refers here to a collaborative approach in which faculty staff observe and give feedback on one another's teaching. The data in the study draw on video observations of and interviews with a four-member (senior faculty) peer group observed over a 5-month period. The analysis of the group interactions shows how the members made themselves vulnerable during peer review and reveals the implication of trust in this collaborative setting. The sociocultural perspective draws here attention to the key role of turn-taking rhythms in the interactions constituting the development of trust. This paper also discusses the significance of developing suitable conditions for trust when arranging peer-based review of teaching in higher education.

Introduction

In a previous study published in this journal, Clouder (Citation2009, 290) underlines the importance of creating ‘supportive, safe and trusting’ learning environments for students, ‘ … where risks can be taken’. Drawing on Clouder's notions, this study explores the role of trust when teachers expose their teaching to peers. The setting of our study is a peer-mentoring group at a Norwegian university. Observing one particular group over a period of 6 months, we emphasise how trust is created interactionally in this setting and how this contributes to a productive environment on learning about teaching.

A challenge related to teaching in higher education is that teaching has traditionally been conceptualised and conducted as an individual responsibility (Biggs and Tang Citation2010). As a result, levels of awareness, attitudes and experience sharing become limited (Edwards Citation2010; Hargreaves Citation2000; Thomas et al. Citation2014). Previous research has also documented the positive outcomes of activities engaging teachers in peer interactions to enhance their teaching (Thomas et al. Citation2014).

Based on these insights, higher education in Norway is meeting new demands for university educators across disciplines to develop teaching based on collaborative peer mentoring (Norwegian Ministry of Education Citation2017). However, asking peers to pose challenging questions and offer constructive criticism will necessarily involve trust issues. Accordingly, this study investigates the appearance and development of trust in peer mentoring, in which teachers expose their teaching to colleagues. We take particular interest in how trust is formed as a collective in-group dynamic.

The term collective refers here to a relational dynamic in which norms and structures are not necessarily clear-cut and ready-made but are created through negotiations in the group (Fenwik Citation2008). From this analytic perspective, the individual is not considered a separate participant but is seen as an intersubjective relation achieved through social interaction (Wenger Citation2000; Seemann Citation2009). We analyse this dynamic via video-recorded interactions of a peer group of four participants who review one another's teaching throughout a semester. From this perspective, we examine how trust emerges and how this grows into group expectations and relational stability. The empirical manifestations of trust here are participants’ willingness to reveal uncertainty and the extent to which group arrangements accommodate this kind of fragility (Curzon-Hobson Citation2002; Clouder Citation2009).

Peer mentoring in teaching – previous research

By involving trusted peers who can ask challenging questions and offer constructive criticism, peer-based feedback in groups has been suggested as a productive measure to enhance teaching and learning quality in higher education (Costa and Kallick Citation1993; Kohut, Burnap, and Yon Citation2007). This is particularly the case when peer observation and critical reflection about actual teaching practices are engaged (Donnelly Citation2007; Martin et al. Citation2000).

Although there is substantial literature on reflective practice as an important measure in developing teaching and instruction, empirical studies on the nature of productive peer-based reflectiveness about teaching are scarce (Hammersley-Fletcher and Orsmond Citation2005). Previous research has typically raised questions regarding the types of activities that facilitate reflexivity, as well as the role that interaction with peers and faculty members plays in enhancing supportive reflection about teaching (Thomas et al. Citation2014). Especially when considering the outcomes of feedback processes, recent studies have emphasised social and dialogical acts rather than dyadic comments (Ajjawi and Bound Citation2015; Price et al. Citation2010; Steen-Utheim and Wittek Citation2017).

The findings from such studies suggest that feedback based on participants’ joint meaning-making with clear contextual relevance appears useful (Price et al. Citation2010; Scaratti, Ivaldi, and Frassy Citation2017). This notion of situatedness and active engagement has particular relevance in the current study. The research questions we raise in this respect are as follows:

How can a sociocultural-based conception of trust contribute to understanding close collegial relations when sharing perspectives on teaching?

How is trust constituted in this close collegial setting of a peer group, and what conditions seem important in this respect?

The first research question above aims at establishing a sociocultural conceptual basis for our forthcoming empirical analysis. The second question signifies our attempt to identify how trust is empirically enacted in conversations and speech acts, here represented through the data collected from peer group discussions. Below, this article will start by exploring sociocultural notions of trust. This is followed by a description of the context, methods and empirical basis of our study, which is then followed by our analysis of specific conversations between peers. Finally, we will discuss how trust unfolds in this context and the significance this holds with respect to creating sharing and collaborative spaces for teachers in higher education.

Conceptual and analytic framework

Trust is commonly referred to as the interdependence between a trustor and a trustee, involving risk and vulnerability (Stensaker and Maassen Citation2015). This dyadic notion, which dominates the literature, is frequently discussed in relation to rationalist calculations of predictability and vulnerability (Kramer, Brewer, and Hanna Citation1996). Trust is also defined in terms of primary versus reflective notions, with the former referring to an ontological preconception and the latter involving trust through learning, experience and reflective thinking (Markova, Linell, and Gillepsie Citation2007). Much of this research is empirically based on retrospective analysis of how trust has been individually experienced in various contextual surroundings (Saivolainen and Ikonen Citation2016).

In this study, we define trust as a sociocultural and relational process, something that unfolds and develops through the interactions between participants within specific contexts. An overview of how trust is considered a socio-cultural phenomenon is thoroughly described in the edited volume Trust and Distrust by Markova, Linell, and Gillepsie (Citation2007). In the introductory chapter of this work, the same authors present a general structure of trust which is relevant to our study, with the following model providing a helpful overview.

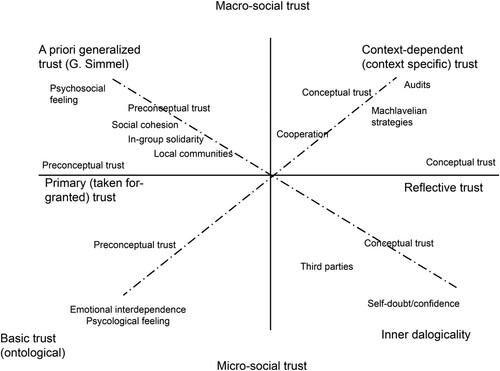

shows that basic and primary trust is something we take for granted and normally do not question. Basic primary trust (in the lower left quadrant) refers to the pre-moral and affective attachments between a caregiver and a caretaker. By contrast, a-priori generalised trust (in the top quadrant) refers to how we learn to trust in social settings and concerns dependency on others and security against threats. This kind of trust is rarely addressed explicitly and is usually taken for given. The third quadrant (on the top right) is based on a different kind of human relation, which is typical of complex and modern societies where we need to rely on people we do not know. This kind of generalised trust is more context bound to specific social practices established between strangers within organisations.

Figure 1. General structure of trust (Markova, Linell, and Gillepsie Citation2007, 11).

The fourth quadrant (bottom right of ) concerns interpersonal and intrapersonal trust and communication. The concept of inner dialogically (dialogues within the self) relates to the capacity of evaluating one's own and others’ past and present conduct, reflecting on personal issues and making predictions about future conduct and intentions (Markova, Linell, and Gillepsie Citation2007, 20).

For the purpose of investigating trust in the current study, we emphasise the third quadrant. Peer groups are considered here as a constellation of employees who have similar roles and obligations but who are personally unknown to one another, as well as being affiliated with different disciplinary domains of an organisation. This combination of shared norms, unfamiliarity and divergent affiliation brings about a cooperative setting where trust has to be established (Seemann Citation2009).

Empirical research on how this kind of interpersonal trust emerges and evolves is in its early stage, with very few studies coming from real-life situations (Saivolainen and Ikonen Citation2016). Whilst the importance of trust in collaborative settings has been widely recognised, most research has examined this topic from the perspective of individuals, thereby paying less attention to how trust emerges in group behaviour and actual collaborative interactions (Ikonen Citation2013).

In our analysis of peer groups, we are interested in exploring this research gap by addressing how trust is interactionally co-created. We will draw on Kramer, Brewer, and Hanna’s (Citation1996) idea that trust is made visible when interactions open opportunities and represent vulnerability (Kramer, Brewer, and Hanna Citation1996), but we also visualise how the participants grasp opportunities for testing unfinished thoughts and ideas.

Another empirical marker of emerging trust is so-called opening-up initiatives. These typically surface as challenges or tensions and can unfold as either backward processes leading to withdrawal or forward processes leading to deeper relations and growth opportunities (Saivolainen and Ikonen Citation2016). Depicting conversational tensions and investigating how these evolve could be a gateway for identifying emerging relational trust.

It is important to note here that the formation of trust is expected to unfold periodically across conversational events (Ikonen Citation2013). Empirically, this means that signs of emerging trust are likely to occur in spirals, in which a trusting utterance may refer to a previous clause opening a trusting expectation. Such signs may surface as confirming utterances, recognition and familiarisation, often perceived as solidarity, empathy and shared interest (Mercer Citation2000). Whilst the circularity in these interactional acknowledgements of trust can be difficult to capture in situ, we still consider it possible.

Considering the above-described empirical trust markers (exposure, episodic spirals, opening-up initiatives and confirmation), we take interest in how these characteristics can be envisioned in dialogues in our observed peer group.

Context and methods

The peer group observed in this study is a part of a professional development program at a large research university in Norway. The focus in this program is to provide theoretical and research-based perspectives on teaching and student learning in higher education and to relate these concepts to the participants’ teaching. An important part of the program is establishing peer groups in which colleagues observe, discuss and provide peer-based feedback on one another's teaching.

The main purpose of this activity is to provide a collegial forum for teachers to discuss and reflect on teaching practices. This arrangement is purely formative, building on the idea that formative reflection on one's own and others’ instructional practices is imperative for opening up to alternative perspectives and making experimental improvements (Bransford, Brown, and Cocking Citation2000; Curlette and Granville Citation2014; de Lange and Lauvås Citation2018; Lauvås, Lycke, and Handal Citation2016).

Given the complexity of the analysis and the amount of data involved, we selected one group for the video-based observation. shows the four participants in the observed group, their fields of expertise and their affiliations.

Table 1. Overview of participants, their fields of expertise and affiliations.

shows that the members of this group have different disciplinary and organisational affiliations, such as medicine, social sciences and the humanities. The empirical data collected draw on longitudinal observations stretching over a period of 5 months. Alvesson and Sköldberg (Citation2000) inspired this empirical design for a qualitative longitudinal study, in which the combination of data sources adds empirical depth to the analysis. provides an overview of all the data collected in this respect.

Table 2. Overview of collected data.

Our main data in this material are based on the video observation of all parts of the peer group arrangement. This material amounts to 18 h of data, which have been fully transcribed. All informants voluntarily agreed to participate, as confirmed in a signed consent form. The original language of the data material was Norwegian, which was translated by the authors into English. These translations were compared and discussed regarding interpretation issues. The transcribed material was also anonymised with the use of fictive names in the extracts.

Our analytic approach to the material aims to provide an overview of the video corpus based on thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke Citation2006). Drawing on the overview provided through this analysis, we have selected illustrative extracts of how trust is brought to bear in the peer group conversations. Our focus in the analysis is not on empirical generalisation but on the unique and context-specific processes related to trust development.

Given the textual limitations in this paper, we are compelled to make some empirical selections. One sampling choice is based on consideration of entry into the group at a stage where trust is still being explored by its participants. Second, we are conscious of depicting real tasks, which exclude the first meeting in the introductory course. Third, we consider it important to select two conversational episodes that demonstrate how trust unfolds, enabling us to comparatively discuss similarities and variations.

We have therefore selected two strings of conversation from the pre-observation meeting, depicting Kate explaining her teaching on welfare politics and Andrew presenting his seminar on sensors in music science. The reason for selecting these two participants is that their teaching draws on similar cases in ongoing student courses.

Some final notes on our analysis are required. A primary focus in this study is to address how trust emerges in a close collegial constellation. A primary tool of inquiry in this respect is how trust is constituted in situ or as situated meanings. Our focus is not on revealing general indicators but rather on how utterances instigating trust are implicitly rooted in and adapted to the context. This implicitness is also obvious from our thematic analysis, in which direct references to trust are rarely mentioned. Instead, what we are addressing in our analysis is how a mid-level pattern of trust is created relationally though shared experiences in practice (Gee Citation2003). Utterances are therefore not identified as fixed meanings, but how they surface as cues of meanings in the ongoing activity. We therefore look for cues of trust in utterances and make assumptions about how these interactional episodes create premises and progressions for further expectations between the participants.

Analysis

In this section, we will delve into the conversational details that appear essential in developing trustworthiness. We do so by focusing on the two selected participants, Kate and Andrew, specifically how they expose themselves and their teaching to colleagues whom they barely know, along with the responses they receive from their peers. We unpack conversations in the pre-observation meeting, which lasted for 2 h.

In the extracts below, we will encounter all the four group members (Peter, John, Andrew and Kate), in addition to a supervisor from the unit of academic development (Sarah), who led the pre-observation meeting. Prior to this pre-observation, memos for each participant, describing their teaching, had been distributed. The time slot of 2 h was divided between the four participants, and Sarah started the meeting by explaining the procedure and taking the participants through the four sessions to be observed during the following 5 months. After this introduction, the participants started going through each of the group members’ teaching, first by explaining their background and what the teaching was about, followed by what they were uncertain about and wished to discuss further with the group.

1) Andrew

Below, we enter the conversation as Andrew starts explaining his teaching, which was the third to be discussed in the pre-observation meeting. Andrew's teaching session was a seminar on sound theory and sound effects, a part of a course in musicology at the bachelor level. In this first extract, Andrew has just started describing his teaching session:

Extract 1

In line 1 in the excerpt above, Andrew starts describing the overall course in musicology. In line 3, he starts describing the particular lecture that the peer group is going to observe and give feedback on. Here, Andrew goes into more detail about the lecture, which is about sensor technology. In this introduction, Andrew elaborates on his aims and refers to reflecting about the types of sensors and the properties of sensor interaction. The other participants listen and confirm their understanding sporadically though gestures and oral confirmation. A change occurs in lines 6–8 when Andrew is interrupted by John, who questions, ‘What is a sensor?’

Regarding trust, John's formulation ‘I don't really understand’ signals openness or exposure by revealing a lack of insight. Taking this risk can be seen as a sign of trust (Kramer, Brewer, and Hanna Citation1996). The statement can, on the other hand, also be interpreted as a mild criticism of Andrew's lack of clarity and a need for additional information for the group. This can be considered an opening-up initiative, which could lead to either a forward or backward process (Saivolainen and Ikonen Citation2016). It is therefore of particular interest in our further analysis how Andrew responds to this (potentially) challenging question.

Extract 2

As we see in line 9, Andrew's uptake is an attempt to clarify what a sensor is. He elaborates this with illustrations and examples and by using his own mobile phone. In line 19, however, John again declares that he still does not understand. This second interruption creates laughter in the group but also demonstrates a misalignment in understanding Andrew's explanations. The last utterance in line 21 appears as an attempted closure, with a response that moves the focus from this pre-observation setting to the forthcoming teaching session.

In this excerpt, trust continues to be ingrained not only in John's self-exposure but also in the risk of relying on Andrew's clarification. Andrew's elaboration on sensors can, on the other hand, be considered as a forward movement of the opening-up initiative, an opportunity to create joint understanding (Seemann Citation2009; Saivolainen and Ikonen Citation2016). Peter's questioning for the second time in line 19 can be seen as an even higher risk, as it negates Andrew's attempted explanations. The attempt to close down John's contribution might therefore not be a surprising turn, in which Andrew seems to give up on his attempt to address the disruption by withdrawing (Saivolainen and Ikonen Citation2016).

As noted in the theoretical section, the way natural talk, such as this, evolves (and how themes surface and resurface) rarely develop neatly and in clear-cut ways. In this respect, it is interesting to go forward 30 s, when Andrew continues explaining his teaching session but, at a certain point, chooses to re-visit John's query: ‘But, like John asks, “What is a sensor?” Most of, well, all students will start from there: “What is a sensor?” So I will have to … well it starts from there’. In this utterance, Andrew re-opens the previous issue raised by John, and, at this point, Kate enters the discussion:

Extract 3

As we see in lines 22 and 25, Kate continues on the notion of what a sensor is and explores what this might mean in an actual teaching situation. This is confirmed by Andrew. After this, John joins in again, confirming that he comprehends more and elaborates further on what this means with respect to Andrew's teaching (lines 30–31). Sarah also joins in at the end by mentioning the diversity of the course. This last utterance is received in an interesting way, as Andrew asks, ‘Is it too much?’

This excerpt is interesting in several respects. First, when Andrew re-opens the previous challenge of John not understanding, he acknowledges the relevance of John's contribution and thereby re-opens the opportunity to explore the issue in more depth. This might be an attempted conversational repair. When Kate also enters the discussion, she does two important things – she confirms John's previous challenge (by referring to it) and acts on Andrew's re-opening by encouraging further elaboration. Kate's contribution therefore has a double function of confirming both John's and Andrew's previous utterances (Mercer Citation2000) whilst providing an opportunity for forward processing and deepening the conversation (Saivolainen and Ikonen Citation2016). Trust here is generically rooted in the confirmation of previous contributions, as well as in opening a space for further elaboration. Kate's contribution can therefore be considered an interactional enactment of trust providing the opportunity for a forward process.

Finally, the above episode is an interesting illustration of the periodic characteristics in trust-formation unfolding in an interactional spiral (Ikonen Citation2013). It is also interesting to note that Andrew ended up with using his mobile phone in his teaching.

2) Kate

We will now turn to the next session from the pre-observation, when Kate's teaching is discussed. The excerpt starts with Kate stating that she is excited to have her peers observing her teaching:

Extract 4

In lines 1 and 3, Kate opens up for a joint exploration of her teaching challenges. The lecture is new to her, and it is the first one in the course. In line 3, she explicitly states that she has two different foci she wants to discuss – how to make a rather boring theme interesting for the students and how to engage the students in a dialogical exploration. In this initial opening, Kate presents herself as vulnerable because she lacks a solution, with the possible gain emerging from the conversation in the group (Kramer, Brewer, and Hanna Citation1996). For several minutes, the group discusses how to make the academic content relevant and interesting for the students. Peter and John have a number of ideas about stories from the media that she can incorporate as hooks.

Extract 5

At the beginning of this excerpt, John begins by presenting suggestions on how to start Kate's teaching. Kate recognises the input by showing minimal response (nodding, smiling, taking notes, saying ‘Yes’ and ‘Mmm’), indicating that she is interested to hear more about their ideas. She demonstrates trust to the group by expecting that they can contribute with their advice. At one point, Kate takes an initiative to change the focus in the conversation away from how she should approach engaging the students’ interest to more genuinely creating a dialogical classroom environment.

Extract 6

In lines 26, 28 and 30, Kate repeats that one of the core aims of her teaching is to establish a safe atmosphere for the students; she displays eagerness to discuss how she, as a university teacher, can establish a dialogue with her students instead of taking a traditional lecturing role. Andrew acknowledges Kate's statement immediately by referring to his own view and his own experiences in line 31, exposing his own vulnerability as a teacher in establishing a good relation with his students. This interactional confirmation (Mercer Citation2000) can be considered an empathic supportive statement in sharing vulnerability with Kate and thereby signalling a safe space for the conversation.

However, in line 41, John again picks up the idea of including an interesting story to draw the students’ interest. The conversation after this continues to follow John's input despite Kate's effort to change the focus of the conversation. After five minutes, Kate makes a new attempt:

Extract 7

In line 42, Kate takes a new initiative to move the discussion towards how to include the students. Andrew's uptake is interesting in this regard. In line 47, he politely expresses that John's suggestions might be less relevant for Kate and that the group should create a joint focus of the conversation for the benefit of Kate's interests. This initiative by Andrew is partially challenging the previous focus of the conversation and runs the risk of retrieval and even defensiveness; however, it is also an opportunity for forward processing and deepening the conversation (Saivolainen and Ikonen Citation2016). Andrew reinforces this initiative in line 49 by continuing the discussion of practical implications, thus trusting Kate to accept this confirmation. He supports Kates re-opening in line 42 by expressing a shared understanding but also takes the risk of being reinforced by her. In this sense, we might be witnessing an attempt to re-establish trust in the group.

The process of relational trust developing in this second case is complex, as it stretches over several clauses; here, John and Peter seem to be pulling the conversation towards a focus slightly misaligned with what Kate expresses. This misalignment is not immediately notable and does not evolve into a direct confrontation as in excerpt 7. Similar to Andrews's case, the establishing and channelling of trust here seem to unfold in a spiral manner with subtle references across interactional events (Ikonen Citation2013). In this second case, the formation of trust therefore seems to unfold in a backward process (excerpts 5 and 6) by building on previous utterances, such as Andrew's reinforcement of Kate's re-opening.

In summary, what surfaces in both cases is how the participants make themselves vulnerable by displaying uncertainties, doubt, insecurity, lack of experience and lack of control of the expected outcomes of their teaching tasks. Both cases also demonstrate how these steps of vulnerability open opportunities for discussing them, although the conversation can be derailed and therefore needs to be pulled back by the trustee. Another common feature from these two cases is how trust emerges relationally as a synthesis between the risk-taking and the response.

Discussion and conclusion

The first research question in this study concerns how trust can be conceptualised from a sociocultural perspective and what this conceptual grounding provides in the analysis of collegial relations. In the theoretical section, we established that peer mentoring would need to be addressed on a relational basis, achieved though the participants’ interactions. In this perspective, trust is made visible through interactions that not only represent vulnerability but also open opportunities for supporting contributions from colleagues. What the theoretical section of this paper identifies was firstly context-dependent trust, which is typical of professional settings; it is achieved though collaboration and is bound to micro-settings with a form of limited trust that has to be established between participants. The analysis of trust on these grounds could potentially provide an explanatory basis for how group expectations, norms and relational stability are established interactionally in a specific small-group setting.

How this conceptual grounding actually works, however, must be demonstrated through concrete empirical analysis. This brings us to the second research question addressing how trust is constituted in a peer group setting. Within this focus, we intended to look at the participants’ willingness to take risks, reflecting their readiness to expose themselves to the group and applying a sociocultural analytic lens in doing so.

What our above analysis has revealed is how trust is constituted in a setting where participants have to rely on one another when they do not know one another very well. It is interesting to note from the conversations that although the discussions are supposed to focus on the pedagogical aspects of teaching, all the participants dwell rather extensively on one another's academic themes that will be addressed in their teaching. This might be a part of how trust is constituted – partially by respecting one another's disciplinary field and by gaining sufficient insight to give appropriate feedback.

What we have attempted to demonstrate through our analysis is how a context-specific form of trust is implicitly present in interactions and group relations (Markova, Linell, and Gillepsie Citation2007). What we can also see from the analysis is how trust is implicitly negotiated and re-negotiated, rather than focusing on individual properties and personal qualities. This is of particular interest in professional micro-settings where relational trust is achieved between previously unknown participants. The contribution of the sociocultural perspective is here to explain beyond individual perceptions how joint actions contribute to creating mutual trust (Seemann Citation2009).

The way we conceptualise trust in this text also highlights how vulnerability emerges when peers open up for alternative teaching perspectives and suggestions. Opening up like this has a potential cost associated with it and relies on trust. In the previous analysis, we unpacked how Andrew and Kate open up spaces for the joint exploration of their teaching contexts. They do so by revealing their uncertainty. They invite their peers into discussions that become rich and engaged, and the peers trust that their input is welcome. The symmetric relations in this group constellation also suggest that trust is vital for opening the intimate space of the classroom and allowing for productive and supportive discussions about teaching strategies (de Lange and Lauvås Citation2018). In several incidents, this is revealed in talk focused on creating mutuality through confirmation and elaboration, with an implicit focus on achieving solidarity rather than seeking a correct outcome (Mercer Citation2000). The focus in this kind of conversation is therefore marked by joint decisions without really challenging one another's utterances. However, we also see how the participants close down the conversations at a certain point, clarifying that they appreciate the suggestions but that they, from that point, will have to make their own decisions about their teaching. This opportunity to close down the conversations likewise seems to represent an important part of the space of trust emerging in the conversations in this peer group (Saivolainen and Ikonen Citation2016).

A limitation of our study besides its limited empirical sample is the possible constraints implicit to the peer group arrangement and organisation. It would be interesting to conduct a follow-up study that looks into how the peer feedback arrangement worked if there were a second phase that repeated the entire procedure. Through the first phase (which is covered by our study), the participants learn about one another, and they become familiar with the structure of the model for peer supervision. These are all important aspects of developing trust as an in-group dynamic. Whilst our analysis unpacks how fine-tuned and complex the constitution of trust is in this context, how this evolves throughout different phases should be investigated in further depth. Another limitation is that our empirical sample does not provide a sufficient explanatory grounding for gender differences, which calls for a more extended dataset for further explorations.

As a concluding remark, we consider it timely to revisit the notion of trust introduced at the beginning of this paper. Trust was presented as an important focus for establishing fruitful relations and creating a space where learners feel ready and safe to reveal their uncertainty more openly (Curzon-Hobson Citation2002; Clouder Citation2009). What our analysis first displays is that this kind of trust is related to a space of focused social interactions where trusted relations can emerge over time. Equally important is reciprocity, which seems to be an important premise in establishing the kind of peer-based relations where trust can be empowering and can contribute to transforming dialogue (Curzon-Hobson Citation2002, 272). The intricacy in creating this kind of environment for both academic peers and students is how this exposure can be made safe in a larger learning environment or if this has to be limited to smaller group settings. A criticism to this group-based organisation is that asymmetry can emerge, as small group constellations can be taken over by dominant participants or internal power relations. This is especially a risk when groups operate without guidance and supervision. Another question is how certain modus operandi can prevent this typical challenge in group work and the extent to which approaches suitable for plenary settings can be developed.

What we can confirm on the basis of our qualitative analysis is an empirical illustration of how trust has been constituted interactively between peers within a specific micro-social setting. We have also demonstrated how this created a learning space, albeit for teachers, to achieve a mutual benefit, which is to improve their teaching. What our empirical manifestations also demonstrate is the fragility that this kind of exposure entails and simultaneously the opportunities for development it can create; these opportunities would be difficult if not impossible to attain without this kind of exposure. An idea worth pondering in this respect is what could potentially happen to the group if summative assessment demands were added as a quality measure of teacher performance. A comparative analysis of conditions between formative and summative measures could potentially be very informative in displaying the significance and conditions of trust in our efforts to develop productive environments for learning about teaching in higher education.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Ajjawi, R., and D. Bound. 2015. “Researching Feedback Dialogue: An Interactional Analysis Approach.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 42 (2): 252–265. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2015.1102863

- Alvesson, M., and K. Sköldberg. 2000. Reflexive Methodology: New Vistas for Qualitative Research. London: Sage Publications.

- Biggs, J., and C. Tang. 2010. Teaching for Quality Learning at University. 4th ed. Berkshire: Open University Press.

- Bransford, J. D., A. L. Brown, and R. R. Cocking. 2000. How People Learn. Cambridge, MA: National Academy Press.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in n Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101. doi: https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Clouder, L. 2009. “‘Being Responsible’: Students’ Perspectives on Trust, Risk and Work-Based Learning.” Teaching in Higher Education 14 (3): 289–301. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/13562510902898858

- Costa, A., and B. Kallick. 1993. “Through the Lens of a Critical Friend.” Educational Leadership: Journal of the Department of Supervision and Curriculum Development 51 (2): 49–51.

- Curlette, W. L., and H. G. Granville. 2014. “The Four Crucial Cs in Critical Friends Groups.” The Journal of Individual Psychology 70 (1): 21–30. doi: https://doi.org/10.1353/jip.2014.0007

- Curzon-Hobson, A. 2002. “A Pedagogy of Trust in Higher Learning.” Teaching in Higher Education 7 (3): 265–276. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/13562510220144770

- de Lange, T., and P. Lauvås. 2018. “Faculty Peer Mentoring in Higher Education – An Analysis of Peer Conversations.” UNIPED 41 (3): 259–274. doi: https://doi.org/10.18261/issn.1893-8981-2018-03-07

- Donnelly, R. 2007. “Perceived Impact of Peer Observation of Teaching in Higher Education.” International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education 19 (2): 117–129.

- Edwards, A. 2010. Being an Expert Professional Practitioner: The Relational Turn in Expertise. London: Springer.

- Fenwik, T. 2008. “Understanding Relations of Individual-Collective Learning in Work: A Review of Research.” Management Learning 39 (3): 227–243. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/1350507608090875

- Gee, J. P. 2003. An Introduction to Discourse Analysis—Theory and Method. London: Routledge.

- Hammersley-Fletcher, L., and P. Orsmond. 2005. “Reflecting on Reflective Practices Within Peer Observation.” Studies in Higher Education 30 (2): 213–224. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070500043358

- Hargreaves, A. 2000. “Contrived Collegiality: The Micropolitics of Teacher Collaboration.” Sociology of Education: Major Themes 3: 1480–1503.

- Ikonen, M. 2013. “Trust Development and Dynamics at Dyadic Level. A Narrative Approach to Studying Processes of Interpersonal Trust in Leader–Follower Relationships.” PhD diss., University of Eastern Finland.

- Kohut, G. F., C. Burnap, and M. G. Yon. 2007. “Peer Observation of Teaching: Perceptions of the Observer and the Observed.” College Teaching 55: 19–25. doi: https://doi.org/10.3200/CTCH.55.1.19-25

- Kramer, R. M., M. B. Brewer, and B. A. Hanna. 1996. “Collective Trust and Collective Action: The Decision to Trust as a Social Decision.” In Trust in Organizations: Frontiers of Theory and Research, edited by R. M. Kramer, and T. R. Tyler, 357–389. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Lauvås, P., H. K. Lycke, and G. Handal. 2016. Kollegaveiledning—med Kritiske Venner [Peer Supervision—with Critical Friends]. Oslo: Cappelen Damm Akademisk.

- Markova, I., P. Linell, and A. Gillepsie. 2007. “Trust in Society.” In Trust and Distrust—Sociocultural Perspectives, edited by I. Markova, and A. Gillespie, 3–27. New York: Information Age Publishing.

- Martin, E., M. Prosser, K. Trigwell, P. Ramsden, and J. Benjamin. 2000. “What University Teachers Teach and How They Teach It.” Instructional Science 28: 469–490. doi: https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1026559912774.

- Mercer, N. 2000. Words and Minds: How We Use Language to Think Together. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Norwegian Ministry of Education. 2017. Kultur for Kvalitet i Høyere Utdanning (Culture for Quality in Higher Education). White paper no. 16, 2016–2017.

- Price, M., K. Handley, J. Millar, and B. O’Donovan. 2010. “Feedback: All That Effort, but What Is the Effect?” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 35 (3): 277–289. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/02602930903541007

- Saivolainen, T. I., and M. Ikonen. 2016. “Process Dynamics of Trust Development: Exploring and Illustrating Emergence in the Team Context.” In Trust, Organizations and Interaction: Studying Trust as Process, edited by S. Jagd, and L. Fuglsang. Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Scaratti, G., S. Ivaldi, and J. Frassy. 2017. “Networking and Knotworking Practices: Work Integration as Situated Social Process.” Journal of Workplace Learning 29 (1): 2–23. doi: https://doi.org/10.1108/JWL-06-2015-0043

- Seemann, A. 2009. “Joint Agency: Intersubjectivity, Sense of Control, and the Feeling of Trust.” Inquiry 52 (5): 500–515. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/00201740903302634

- Steen-Utheim, A. T., and A. L. Wittek. 2017. “Dialogic Feedback and Potentialities for Student Learning.” Learning, Culture and Social Interaction 15: 18–30. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lcsi.2017.06.002.

- Stensaker, B., and P. Maassen. 2015. “A Conceptualisation of Available Trust-Building Mechanisms for International Quality Assurance of Higher Education.” Journal of Higher Education Policy Management 19 (1): 30–40. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/1360080X.2014.991538

- Thomas, S., Q. T. Chie, M. Abraham, S. J. Raj, and L. S. Beh. 2014. “A Qualitative Review of Literature on Peer Review of Teaching in Higher Education: An Application of the SWOT Framework.” Review of Educational Research 84 (1): 112–159. doi: https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654313499617

- Wenger, L. 2000. “Communities of Practice and Social Learning Systems.” Organization 7 (2): 225–246. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/135050840072002