ABSTRACT

This paper presents an analysis of a hundred and one handwritten essays by master students in Informatics. The students reflected on their experiences of working with pen and paper for reading and writing as a mandatory assignment for the duration of a five-week intensive course. Taking an inductive approach, reflexive thematic analysis was used to identify patterns of meaning across the full dataset. The essays elicited insightful student reflections on learning, knowing, and being. One overarching theme, New connections, and four sub-theses were identified: Handwriting as note making, Being present for learning, Freedom to think, and Materiality of reading and writing. This study contributes to an improved understanding of the affordances of paper and laptops in the lecture room, based on a student-centred approach, and reflects on how student perspectives can be implemented during lectures.

Introduction

The computer is nothing more, and nothing less, than a box of short-cuts. Admittedly, some are handy. (Ingold Citation2008)

There are several studies comparing longhand and keyboard lecture note-taking. Focusing on note-taking behaviour, Mueller and Oppenheimer (Citation2014) found that using keyboards for note-taking resulted in verbatim note-taking, even when students were instructed not to do so. The result was that these students performed worse on tests implemented a week later. The authors conclude that academic performance is weakened when laptops are used to simplify note-taking. The benefits of simplified note-taking with laptops disappear when notes are mindlessly transcribed, rather than summarised and synthesised. A comparative study by Karjo (Citation2017) confirms these findings. During a test immediately after note-taking, students using pen and paper excelled in making a diagram, summarising, and recalling lists of words.

The time between note-taking and reviewing and using notes affects academic performance. Luo et al. (Citation2018) found improved performance when students were able to review their handwritten notes for 15 minutes after taking them and before the test. The performance of longhand and laptop note-takers was equal when they were not allowed to review their notes.

Rather than using an experimental set-up, as in the above three studies, Desselle and Shane (Citation2018) studied longhand and laptop note-taking on pharmacy students’ performance during two exams in a professional doctorate course. They found a 3.5% improvement in examination scores for longhand note-taking students. Aquilar-Roca and colleagues (Citation2012) created laptop-free zones during lectures and later compared the exam results. They also found that paper note-takers performed better, as the ‘percentage of paper users who received A's was significantly higher than that for laptop users’ (Citation2012, 1304).

Handwriting is also associated with improved conceptual understanding. Differences in conceptual understanding do not become visible when tested directly after a lesson, but are significant after a week (Mueller and Oppenheimer Citation2014; Horbury and Edmonds Citation2020). These differences can be explained by research on embodied cognition (Mangen and Velay Citation2010; Mangen, Walgermo, and Brønnick Citation2013), which shows that cognition is entangled with perception and motor action: learning technologies ‘afford, require and structure sensorimotor processes and […] in turn relate to, indeed, how they shape, cognition’ (Mangen and Velay Citation2010, 397). Alonso (Citation2015) explains the difference as the result of overloading of the cognitive process when information is written with a keyboard, compared with the slow method of handwriting, where information to be recorded needs to be selected. This slower process enables students to ‘become deeper engaged with the material, which enables additionally the storage of the new learning material in a deeper and more connected way with existing knowledge’ (268).

Laptops

Research on laptop use during lectures explored the relation between laptop use, multitasking, student attention, and performance. Laptops are widely used by students for note-taking and their effects have been debated widely, with some lecturers calling for an outright ban on laptops in the lecture room (Elliott-Dorans Citation2018; Fink Citation2010; Hutcheon, Lian, and Richard Citation2019; Young Citation2006). In an analysis of student surveys, Fried (Citation2008) found that 78 of the 128 students used a laptop during the lectures and that 81% of these students checked their email during lectures, 68% used instant messaging, 43% surfed the net, 25% played games and 35% did ‘other things’ (910). The author found a significant negative relation between laptop use during lectures and class performance. Laptops interfered with students’ attention and ability to understand the lecture material. Gehlen-Baum and Weinberger (Citation2012), looking at the use of laptops, mobile phones, and tablets during lectures, found that students use their devices twice as much for unrelated activities (social media, email, chat, games, videos) than for lecture-related activities, such as writing notes, looking at slides online, and lecture-related websites. Similar findings are reported in a large study (n = 2724) in which students were observed as well as asked to self-report their activities on laptops during the lecture (Ragan et al. Citation2014). While 37% of the students reported using their laptops for note-taking, laptops were mainly used for non-lecture-related activities: 61% of the time of the lecture-based on survey data and 63% of the time of the lecture-based on observed data. A total of 88% of the laptop users multitasked during their lectures. Laptop multitasking has shown to be disruptive, both for the laptop users and for their peers seated in view of these users (Sana, Weston, and Cepeda Citation2013; Selwyn Citation2016). That multitasking affects the academic performance of students can be explained through findings in the cognitive sciences. Humans actually task-switch, they can't multi-task. Engaging in multiple tasks creates a cognitive bottleneck that slows down the performance on one task, when another task is still being processed (Kirschner and De Bruyckere Citation2017).

Reading

Studies on reading comprehension show that reading from paper results in better text comprehension than reading on a screen. Mangen, Walgermo, and Brønnick (Citation2013) found that document navigation is one of the key factors: ‘Scrolling is known to hamper the process of reading, by imposing a spatial instability which may negatively affect the reader's mental representation of the text and, by implication, comprehension’ (65). The authors also mention immediate access to the entire text, based on visual and tactile clues, as an important factor in creating a mental map supporting reading comprehension.

Subsequent research supports the finding that when students read for depth of understanding, paper supports better comprehension. Lenhard et al's (Citation2017) study with primary school children shows that screen reading results in higher error rates. Singer and Alexander (Citation2017) warn us, however, to be careful with comparing research results. Age group, length of text, topic knowledge, medium preference (digital or paper), and medium performance – how participants judge their own performance when using a particular medium – all play a role in understanding the results. Taking this into consideration in their own study, involving 90 undergraduate students, Singer and Alexander (Citation2017) found no difference between reading from paper or screen when the question was about the main idea of the text. When students were asked about the key points of the text and other relevant information in the text, students reading from the paper were better at recalling these than students reading on a screen. When these results were compared with how students judge their own abilities in reading from paper and screen, it became obvious that students overestimate their performance. The authors found that many of the students who presumed they would perform better digitally did in fact perform much better when reading from paper.

Overview of this study

Rather than taking a comparative or quantitative approach, this paper presents a qualitative analysis of student reflections on writing lecture notes with pen and paper and on using a paper course compendium. The aim of the study is to gain deeper insight into students’ use of reading and writing tools and how students experience the effect of these tools on their learning.

This study is based on the analysis of a hundred and one handwritten ‘reflective essays’ (Badley Citation2009). The essay was a mandatory assignment in the Master/PhD course Design, Technology & Society, at the Department of Informatics of the University of Oslo. In this course, the students explore a wide variety of topics emerging from the interactions between design, technology, and society. To provoke more personal reflections and experiences, one of the mandatory assignments in the course was to use a paper compendium and to write all lecture notes by hand on paper. The final assignment in the course was a hand-written essay, in which the students reflected on their experiences of reading and writing with paper in the course. The purpose of the assignment was to provide students a tool to reflect on the effects of technology on their body, a topic related to the objectives of the course, and, secondly, a tool to reflect on different reading and writing technologies and their effects on learning.

In a present-day student life, pen and paper can be considered disruptive technologies. Already during their high school studies, Norwegian students receive a personal laptop and keyboard writing has become the norm. This became also clear in the essays, in which students complained about cramps and pain in the hand holding the pen over a longer time. Students also experienced the mandatory use of pen and paper in the course as being forced to do something they usually don't: ‘I was a little shocked in the beginning. I am used to write on the computer, because it is easier […]’ [5]. Another student wrote: ‘When I first got told that everything should be written by hand and that computers were not allowed in class, I got surprised. I felt like some of my freedom was taken away from me’ [21]. This was not a negative experience, as the same student continues: ‘But one thing I noticed is that I tend to have a lower bar for handwriting than computer writing. Handwriting feels more informal and it's easier to write down my thoughts, maybe that makes me remember better?’ [21]. Others reflected in a similar way: ‘It has been an interesting experience to be ‘forced’ to write all of our notes by hand’ [53] and ‘Being forced to take my lecture notes by hand has been a freeing experience’ [24].

Theoretical and methodological positioning

This study is positioned in a critical theory of technology, which

draws on social constructivism for an alternative to technological determinism and on [Actor Network Theory] for an understanding of networks of persons and things. The constructivist approach emphasizes the role of interpretation in the development of technologies. Actor Network Theory explores the implications of technical networks for identities and worlds’ (Feenberg Citation2017, 640; Citation2002)

On the basis of Feenberg's critical theory of technology, writing technologies, such as pen, paper, and keyboard, is considered value-laden technologies. Through their design, particularly economic, cultural, and social orders are inscribed in these technologies, without denying the users of these technologies some control on how they will use them. Similarly, university lecturers cannot change the technology the students bring to the lecture room, but they can construct a learning environment which shapes the use of these technologies (Thomas, DeVoss, and Hara Citation1998).

This critical theory of technology guides the methodology of the Design, Technology & Society course (DTS), which is based on a critical pedagogy (Freire Citation2013; Kincheloe Citation2011). The course uses a critical constructive learning methodology (Bentley, Fleury, and Garrison Citation2007; Scheer, Noweski, and Meinel Citation2012), which is a student-centred: students are seen as learners, who are actively involved in creating their own knowledge processes in conversation with the lecturers. The lecturers, on their side, are actively involved in engaging learners in critically assessing information and knowledge from different sources and constructing new knowledge (van der Velden, Joshi, and Culén Citation2018)

During the course, the students had to write two reflective short essays. The first one, a reflection on the role of theory, after two weeks into the course, had no requirements; every student wrote the essay on a computer. The students were obliged to write the second essay by hand on paper. Badley (Citation2009) describes reflective essaying as a writing process in which writers interpret their experiences while they write ‘a free and serious play of mind upon a topic in order to learn’ (Badley Citation2009, 257). Reflective essaying gives students important insight into their interpretations of experiences and learning (Badley Citation2009; Hosein and Rao Citation2017; Leijen et al. Citation2012).

The reflective essay, as a method, is also part of the ‘full-contact pedagogy’ approach taken in the DTS course (Crawley Citation2008). This means that the students read the day's literature before they come to the lecture, so that the lecture is used to critically assess the literature through a case, questions, a video, etc. Crawley (Crawley Citation2008, 21) describes teaching with questions as an important tool for teaching students reflective and critical skills:

They must examine what they think about an issue, a type of organizing logic, or a theorem. Do they agree? In other words, it teaches them to critique epistemologies, which is not an easy task. Indeed, this may be the purest example of teaching critical thinking skills, which I understand to be one of the clear mandates of all disciplines.

Writing as a learning tool

On the first day of the course, writing was introduced to the students as a technology as well as a learning tool (Tynjälä Citation1998). The students were informed that digital tools were not allowed during lectures and paper notebooks and pens were distributed to the students who had not received this message via the course website.

The combination of writing as a learning tool and experiencing handwriting as a writing technology was also practiced in the form of micro-writing (Dysthe and Hertzberg Citation2006). At the end of each course day, the students were asked to put their pen on paper and write down their reflections on the day without interruption. Each micro-writing session was exactly three minutes long and the objective of this assignment was to let the students experience an uninterrupted flow of thought. Initially, students struggled with writing uninterruptedly:

[W]hen we started doing three minutes writing, I struggled at first, but with every day I could see the improvement. Comparing my notes from the first and last lecture I can see how much my way of thinking has changed [25]

At the start of each new course day, students began with a personal review of the micro-writing of the day before (these notes were never shared with others), followed by a conversation, inspired by these notes, with a student next them. This enabled the students to connect their learning from the day before to that of the other student as well as with the activities of the new course day.

Analysis

In this study, content analysis was used to analyse and make sense of what the essays had in common. The reflexive Thematic Analysis (TA) approach, developed by Braun and Clarke (Citation2006; Braun et al. Citation2018), was chosen to guide the process. Reflexive TA is based on a fully qualitative research paradigm, which ‘emphasizes meaning as contextual or situated, reality or realities as multiple, and researcher subjectivity as not just valid but a resource’ (Braun et al. Citation2018, 6). This approach is compatible with the constructivist learning methodology applied in the DTS course, as it can fully engage with the multiplicity of student experiences.

The aim of reflexive TA is to provide a consistent and convincing analysis of the data. Braun et al. (Citation2018) describe the researcher as a storyteller, using the data to give voice to a group of people or to an agenda of social critique or change. This aim corresponds with the purpose of the mandatory student essay, which provided the data for the analysis. The essay offered the students a tool to reflect on technology and learning, while the analysis provides them a voice, through this analysis, in the debate on digitalisation and education.

The reflexive TA applied in this paper consisted of six phases (see ). Reviewing and defining themes is an iterative process, in which possible themes are explored and defined or rejected. Each theme has a clear focus, scope, and purpose and, together, provides a coherent analysis of the data (Braun and Clarke Citation2012).

Table 1. Phases of thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke Citation2006, 87).

Procedure

After becoming familiarised with the content of the essays (phase 1), two rounds of coding were implemented. In the first round (phase 2), words used by the students often functioned as keywords, which were collected in a large code map, with codes on computer reading and writing on one side and codes on paper reading and writing on the other. Each code was referenced with one or more numbers, each number representing one student essay, thus facilitating consultation of the original essays when needed.

The code map enabled a comprehensive overview of all codes. The second round of coding resulted therefore in removing descriptive codes and adding interpretative codes (phases 3 and 4). Some of the interpretative codes combined two or more descriptive codes. For example, student reflections on experiences in keyboard-based note-taking were in the first round of coding described quite literally: you write the lecturer's words, not your own and typist. In the second round of coding, a more interpretative code was given, see .

Table 2. Example of the coding process (phases 2, and 3 in the thematic analysis).

The next step was the identification of themes (phases 3, 4, and 5). A theme ‘captures something important about the data in relation to the research question, and represents some level of patterned response or meaning within the data set’ (Braun and Clarke Citation2006, 82). Clustering of codes into possible themes and drawing thematic maps resulted in a final set of themes that were meaningful in relation to the research question, namely how students experience using paper for reading and writing in the lecture room. This resulted in one overarching theme and four sub-themes (see ).

Table 3. Overview of themes.

Description of the data set

The dataset itself consisted of hundred-and-one handwritten English-language essays, each with a length between 500 and 700 words. In the course document, the essay assignment was described as follows:

In this course you have worked with paper resources and you wrote all your lecture notes by hand. Write a short essay, by hand, in which you reflect on the difference between digital reading and writing and paper-based reading and writing. For example, did it make a difference in remembering things? Finding a citation in your compendium? Writing your essays? How is the experience of writing an essay by hand different than writing it on a computer?

The essays were scanned and submitted in pdf format. The essays were not graded and not read and analysed until all students had received their final grade in the course. All students were non-native speakers in English. The majority of students had Norwegian as mother tongue. In the examples below, their language has sometimes been edited slightly, for readability only. These edits are visualised with the use of square brackets around the edited word.

In order to de-identify the authors of the essays, the citations in the text use a number (e.g. [7] stands for student essay 7). After the delivery of the essays, students were informed about the possible use of their essays for an academic article.

Results

In the presentation of the results of the thematic analysis, frequency counts are not used, as the free-style reflective essay does not facilitate this. However, in some cases, it is relevant to give an indication of the frequency. In this paper, some refers to less than ten students, several refers to less than twenty students, many refers to less than sixty students, while almost all refers to more than sixty students.

Almost all students reflected on the practicalities related to using pen and paper and digital tools. The computer was perceived as a superior technology when it comes to search, referencing, spelling checking, and editing a text. However, drawing, highlighting, connecting words and concepts were considered easier with pen and paper.

Several students started their essay with a reflection on their initial reaction when they heard they could use only pen and paper during the lecture: ‘My first reaction was a bit negative’ [39] or ‘At the beginning I wasn't a fan of the practice – being forced to do something you normally do not do triggers some self-defense mechanism making me not to want to do these exact things’ [3]. Handwriting was also connected with ‘the paste I had left behind’ [90].

Overarching theme: new connections

The analysis of the essays resulted in the overarching theme of New connections. This theme captures the overall experience by the students of being able to make new connections between technology and learning, between past and present, and between mind and body. One of the students expressed this as follows:

[Writing] by hand made me feel like I became ‘a part of my body’. I felt a new connection between my fingers and brain, and the parts in me were working together [in] a much better way than before. For one thing, it gave me more time to think and understand the articles without knowing it. And the best part – I remembered the information even two days later! [8]

The overarching theme also refers to reflections in which student re-connect with previous experiences. Student describes handwriting as ‘old-fashioned’ or something from the past: ‘I close my eyes and I can see perfect cursive writing that during years filled pages and pages of their old notebooks’ [10], while another writes:

Eager as my teenage self was to be taken seriously, I got an idea about the importance of efficient writing on the computer and the importance of making ‘real art’, no more childish scribbles for me. Looking back, I believe this to be misguided conceptions. [55]

Connections are also experienced as consciousness or mindfulness:

In those moments, it is me and the paper with the pen. Not me with the computer and the document, along with the apps, and the distractions, and the calendar, and my mail my google search bar, and my notifications. Just me and the paper. [90]

The overarching theme combines four subthemes: Handwriting as note-making; Being presence for learning; Freedom to think and Materiality of reading and writing (see ).

Theme 1: handwriting as note-making

Students described writing by hand, during the morning lectures and in the micro-writing exercise in the end of the day, as a creative and meaning-making activity: ‘you become more aware of writing down your own thoughts and not just copying the lecturer's notes on the powerpoint’ [41] or transcribing ‘a whole lecture; every single word’ [18]. Students reflected on the visualisation of meaning through the use of highlighters, drawings, and mind-maps, while making lecture notes. One student wrote all her lecture notes as mind-maps: ‘Drawing mind-maps is even more stimulating, as I need to find and draw relevant illustrations to accompany each branch [in the mind-map]’ [47] (see ).

Several students associated handwriting with particular affordances. ‘It clearly offers a lot more freedom to be more creative when taking notes, for example to draw small illustrations, tables, draw lines between different parts of the text, etc.’ [53]. Others reflected on the handwriting as being more expressive, more authentic, and more personal. As a result, one becomes more attached to the words, because they are more meaningful.

Note-making and learning

Many students reflected on the issue of memory when writing lecture notes by hand and wrote that they experienced improved memory. Reasons for improved memory varied, such as:

Writing on paper can make you more creative and makes it easier to remember what you have written. Maybe the reason for this is that you write slower and the brain gets time to reflect what you have written. You are also using the pen and make each letter, instead of just typing the letter. [60]

Theme 2: being present for learning

Many students mentioned the distractive potential of laptops and mobile phones. A learning situation in which all students were using pen and paper was described as enabling presence and more focus during the lecture, not only in relation to the lecturer, but also to fellow students. Some students used the terms ‘more conscious’ or ‘more concentrated’ to express being present for learning.

Student reflections on using a laptop to write lecture notes focused very much on the experience of being a disconnect between typing and thinking, e.g. ‘Did I type this?’ [08]. They described their note taking as being a typist who wrote the lecturer's words, not one's own.

One student also reflected on how writing by hand reflects certain values towards the speaker:

For that reason I feel noting on paper is a more honest way of expressing that they have my attention. Another side is that it shows that I am serious about being there, I am open for knowledge and care to remember it. [83]

Theme 3: freedom to think

In the previous theme, a disconnect between typing and thinking was mentioned. The connection between writing lecture notes and thinking is not only re-established in the use of pen and paper, students express the experience of re-connection in the form of being free or freer: ‘Being forced to take my lecture notes by hand has been a freeing experience’ [24] or ‘On paper, I have greater flexibility when it comes to [writing]. There are no rules – I can make the compendium into my personal ‘recipe’ [8].

Freedom also results doing things one otherwise wouldn't do:

Weirdly enough, it makes me feel more free, less academic, more creative – I made the title a little flower, and the subtitle a cloud. I don't know if that is good or bad, but it would’ve never happened digitally. [100]

The use of the keyboard is sometimes described as a loss of freedom:

There is normally a price to pay with technology. Have we lost a part of who we are. Of how we express and communicate to others, to become ‘standardized’? Have we lost the freedom and creativity the pen gives us? [10]

Theme 4: materiality of reading and writing

Many students reflected on what can be described as the matter (bodies and technologies) of reading and writing as learning activities. The student reflections often focused on the body, such as eyes, brain, and hands. Reflections on the use of the compendium, a 200-page book with copies of articles from journals and books, mentioned the stress on the eyes when reading from a screen. They stated that they were a better reader on paper, had a better overview of the literature, and knew where words were on paper, and had a better understanding of what they were reading, also because they got less distracted. They enjoyed being able to use a highlighter, sticky notes, and writing comments in the margins of the text. While the tangibility of the compendium was seen as positive, the advantages of a digital compendium were often mentioned, such as that it is always accessible online.

Writing by hand was perceived as (re-) establishing the connection between body and writing, by creating a new connection between fingers, brain, and body. These physical connections were seen as positive: ‘The physical movement of my hand as I shape letters and words on paper seems to contribute to me remembering the material better’ [29]. In contrast with using a laptop: ‘By punching away on the keyboard, I wonder if it is the fingers or the brain that is learning a lesson’ [09]. Handwriting was perceived as giving the brain a break, because it is less tiring and stress, and helps to externalise thoughts.

The experience of speed was also noted. Writing by hand was associated with working slower and needing to think before you write, which can be positive, but also negative. In contrast, writing on a computer was associated with writing faster, not the least because several activities could be delegated to the computer, such as spelling checking, citations, and search: ‘As I am writing this essay, I am constantly asking myself ‘Am I spelling this word right?’ or ‘Does my sentences make sense?’’ [41]. Structuring a handwritten essay was often mentioned as a challenge, requiring preparations, such as starting with a mind-map, that were not needed when writing on a computer (see ).

In addition, the red crinkly line, used in a word processing programme to denote a spelling issue, was missed, but some students reflected on the effects of using a spelling checker: they had become worse in spelling and that writing by hand actually improved their spelling.

Discussion

A thematic analysis of the reflective essays was used to give voice to students’ deeper insight in their use of reading and writing tools during lectures and how the students experience the effect of these tools on learning and student work. This resulted in four sub-themes, Handwriting as note-making, Being present for learning, Freedom to think, and Materiality of reading and writing, which together informed the overarching theme of New connections.

The students recognised both advantages and disadvantages of using a computer or pen and paper for reading and writing. These experiences were expressed in bodily terms, such as tired eyes as a result of reading from screens and cramps and pain in the case of handwriting, and in terms of the effectiveness of study-related activities. Editing, referencing, and search were more effectively implemented on the computer than on paper. The majority of these experiences thus conform findings from comparative and quantitative literature on the use of pen/paper and laptops in higher education.

The overarching theme of New connections refers to a particular understanding of the relations between people and technology. Digital technologies are often about connectivity, which refers to being connected with others (Dijck Citation2013). Rather than being connected with others, often through non-academic activities on mobile phones and laptops, the experiences of using pen and paper (reading and writing) was interpreted as creating new connections within oneself and with the learning material. The handwritten essay enabled the students to reflect on experiences of connectedness that were not mediated through a digital technology (laptop, smartphone), but through what was considered an old-fashion technology, pen and paper. The students reflected especially on the connection between the hand that writes and the brain that thinks and learns, which is an important theme in research on embodied cognition (Alonso Citation2015; Mangen and Balsvik Citation2016).

Students associated their experiences in using pen and paper with freedom, creativity, flexibility, and personalisation. These characteristics are usually not mentioned in the literature on learning technologies, but provide important understanding of how students experience learning technologies. The use of pen and paper for lecture notes changed taking notes in making notes. Notes became ‘meaningful’, both in the meaning of words as in their visual expressions through highlighting, circling, underlining, and connecting words, etc. In the essays, these experiences were interpreted as enabling a better understanding of the lecture as well as improved memory.

Another new connection was experienced through the use of the paper syllabus. While the students general perceived computers as a better way to organise and search documents, the syllabus, as a collection of printed articles, enabled them to make connections between the different articles in ways they couldn't do with digital articles. The paper format of the syllabus and the tangibility of its pages enabled both memory as well as connections between the different articles and the different concepts and frameworks presented in these publications. Research has showed the importance of spatial representation of text for text memory and recall (Mangen, Walgermo, and Brønnick Citation2013). The findings seem to suggest that such spatial representation is not only helpful within a document, but also within a set of documents, such as a course syllabus.

Some studies focusing on the positive and negative properties of learning and writing technologies use the notion of affordance (Piper and Hollan Citation2009; Wrigley Citation2019; Fortunati and Vincent Citation2014; Taipale Citation2014). Affordance, a concept developed by Gibson (Citation1986), refers to actions that become possible through an organism's perception of its environment. Many of the affordances the students described in their essays are not just based on perception, but on the tactile information perceived while interacting with pen, paper or keyboard. Affordances may thus be perceived by senses other than our visual sense and become only available while interacting with our environment, not as a perception of our environment. The students’ associations of freedom, creativity, flexibility, and personalisation should therefore not be understood as functions or properties of pen and paper, but as emerging from student practices with pen and paper. Affordances emerge in the relationship between people and technology (Gaver Citation1991; van der Velden Citation2016).

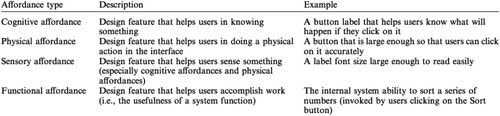

Affordances are an important theme in studies of technology design and use. In the context of interaction design, the design of interactive products and systems, Norman (Citation1998) differentiated between perceived and real affordances. Real affordances are the physical affordances, as understood by Gibson. The notion of perceived affordances refers to what interactions the user of a design perceives as possible or impossible. Hartson (Citation2003) further differentiates between cognitive, physical, sensory, and functional affordances in interaction design (see ).

Figure 3. Types of affordances (Hartson Citation2003, 323).

Hartson's typology contributes to a better understanding the students’ descriptions of the affordances of pen–paper and keyboard. The students reflected in particular on physical and sensory affordances; the physical affordances of the pen allowed them to use it in many more ways during lectures than a keyboard.

Hartson's typology can't explain the experience of new connections between fingers, brain, and body, as these cannot be described in terms of design features. Shotter’s (Citation1983) understanding of affordances may better express how the students reflected on their experiences with pen and paper. Shotter argues that affordances don't pre-exist, they are only there after an activity (interaction) has been completed: ‘an affordance is only completely specified as the affordance it is when the activity it affords is complete’ (27). The affordances identified in this study are not out there to be discovered, but emerge in the active and creative interaction between technology and user. This understanding of affordances is both relational and temporal. Relational in that these particular affordances of pen and paper only became perceptible within reading and writing practices; and temporal, because they could only be identified as affordances after the termination of the practices and during reflections on these past practices in the essay.

The method of writing an essay by hand, to reflect on writing lecture notes and reading course literature, was part of the critical learning pedagogy informing the course. This student-centered approach enabled the students to think beyond the theories and assumptions surrounding the different learning technologies. The reflections on their own experiences enabled them to create new knowledge on the affordances, and their effects, of learning technologies; knowledge that emerged from the interactions between the learning technologies and the sensorimotor processes they afford and structure (Mangen and Velay Citation2010). The thematic analysis of the reflective essays consolidated this knowledge, ‘giving voice’, as Braun et al. (Citation2018) mention, to university students as well as to an agenda of change.

Concluding remarks

This paper presented a reflexive thematic analysis of reflective essays written as part of a student-centred learning approach. The analysis contributed to understanding the experiences students gained in the course, such as the relations between body, technology, and learning (embodied cognition), and the importance of spatial representation in reading. The analysis also contributed to a deeper insight into the affordances of learning technologies, which only become perceptible through multisensory interaction (relational) and known after use (temporal).

The findings emphasise the importance of handwriting for deeper cognitive understanding, not necessarily better test results, and the distractions resulting from the use of laptops and other screens in the lecture room. Students of all disciplines may benefit from being informed about the advantage of handwriting lecture notes.

Acknowledging the importance of handwriting lecture notes needs to be accompanied by some adaptations by the lecturer. Students, who wish to handwrite lecture notes can be invited to sit in the front of the lecture room, so as not to be distracted by colleagues using laptops. Secondly, rather than presenting the students slides full of text, accompanied by even more words by the lecturer, the lecturer could use slides that support the spoken text. This can be photos, diagrams, and keywords. This will enable students to create their own understanding from the spoken text and slides and give them enough time to note this down in a meaningful manner. Students taking lecture notes on laptops will also benefit from having more time to reflect on the slides and spoken words. These slides are preferably not made available during the lecture, because the handout-format restricts the free flow of writing and thinking.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Aguilar-Roca, Nancy M., Adrienne E. Williams, and Diane K. O'Dowd. 2012. “The Impact of Laptop-free Zones on Student Performance and Attitudes in Large Lectures.” Computers & Education 59 (4): 1300–1308.

- Alonso, María A. Pérez. 2015. “Metacognition and Sensorimotor Components Underlying the Process of Handwriting and Keyboarding and Their Impact on Learning: An Analysis from the Perspective of Embodied Psychology.” Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 176 (Feb.): 263–269.

- Badley, Graham. 2009. “A Reflective Essaying Model for Higher Education.” Education+Training, May. https://doi.org/10.1108/00400910910964548.

- Bentley, Michael, Stephen C. Fleury, and Jim Garrison. 2007. “Critical Constructivism for Teaching and Learning in a Democratic Society.” Journal of Thought 42 (3–4): 9..

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101.

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2012. “Thematic Analysis.” In APA Handbook of Research Methods in Psychology, Vol 2: Research Designs: Quantitative, Qualitative, Neuropsychological, and Biological, 57–71. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/13620-004.

- Braun, Virginia, Victoria Clarke, Nikki Hayfield, and Gareth Terry. 2018. “Thematic Analysis.” In Handbook of Research Methods in Health Social Sciences, edited by Pranee Liamputtong, 1–18. Singapore: Springer Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-2779-6_103-1.

- Crawley, Sara L. 2008. “Full-contact Pedagogy: Lecturing with Questions and Student-centered Assignments as Methods for Inciting Self-reflexivity for Faculty and Students.” Feminist Teacher 19 (1): 13–30.

- Desselle, Shane, and Patricia Shane. 2018. “Laptop Versus Longhand Note Taking in a Professional Doctorate Course: Student Performance, Attitudes, and Behaviors.” Innovations in Pharmacy, January, [Article 15]. https://doi.org/10.24926/iip.v9i3.1392.

- Dijck, Jose van. 2013. The Culture of Connectivity: A Critical History of Social Media. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Dysthe, Olga, and Frøydis Hertzberg. 2006. “‘Skriv Alt Du Vet Om … ’ Bruk Av Mikrooppgaver i Undervisningen.” In Når Læring Er Det Viktigste: Undervisning i Høyere Utdanning [When Learning Is the Most Important Thing: Teaching in Higher Education], edited by Helge I. Strømsø, Kirsten Hofgaard Lycke, and Per Lauvås, 177–193. Oslo: Cappelen Akademiske Forlag.

- Elliott-Dorans, Lauren R. 2018. “To Ban or Not to Ban? The Effect of Permissive Versus Restrictive Laptop Policies on Student Outcomes and Teaching Evaluations.” Computers & Education 126 (Nov.): 183–200.

- Feenberg, Andrew. 2002. Transforming Technology: A Critical Theory Revisited. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Feenberg, Andrew. 2017. “A Critical Theory of Technology.” In Handbook of Science and Technology Studies, edited by Ulrike Felt, Rayvon Fouché, Clark A. Miller, and Laurel Smith-Doerr, 635–663. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446282229.n9.

- Fink, Joseph L. 2010. “Why We Banned Use of Laptops and ‘Scribe Notes’ in Our Classroom.” American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education 74 (6): 1–2. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2933023/.

- Fortunati, Leopoldina, and Jane Vincent. 2014. “Sociological Insights on the Comparison of Writing/Reading on Paper with Writing/Reading Digitally.” Telematics and Informatics 31 (1): 39–51.

- Freire, Paulo. 2013. Education for Critical Consciousness. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Fried, Carrie B. 2008. “In-class Laptop Use and Its Effects on Student Learning.” Computers & Education 50 (3): 906–914.

- Gaver, William W. 1991. “Technology Affordances.” In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, CHI ’91, 79–84. New York, NY: ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/108844.108856.

- Gehlen-Baum, Vera, and Armin Weinberger. 2012. “Notebook or Facebook? How Students Actually Use Mobile Devices in Large Lectures.” In 21st Century Learning for 21st Century Skills, edited by Andrew Ravenscroft, Stefanie Lindstaedt, Carlos Delgado Kloos, and Davinia Hernández-Leo, 103–112. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Berlin: Springer.

- Gibson, James Jerome. 1986. The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception. New York: Psychology Press.

- Hartson, Rex. 2003. “Cognitive, Physical, Sensory, and Functional Affordances in Interaction Design.” Behaviour & Information Technology 22 (5): 315–338.

- Horbury, Simon R., and Caroline J. Edmonds. 2020. “Taking Class Notes by Hand Compared to Typing: Effects on Children’s Recall and Understanding.” Journal of Research in Childhood Education, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/02568543.2020.1781307.

- Hosein, Anesa, and Namrata Rao. 2017. “Students’ Reflective Essays as Insights into Student Centred-pedagogies Within the Undergraduate Research Methods Curriculum.” Teaching in Higher Education 22 (1): 109–125.

- Hutcheon, Thomas G., Aileen Lian, and Anna Richard. 2019. “The Impact of a Technology Ban on Students’ Perceptions and Performance in Introduction to Psychology.” Teaching of Psychology 46 (1): 47–54.

- Ingold, Tim. 2008. “In Defence of Handwriting.” Writing Across Boundaries (blog). https://www.dur.ac.uk/writingacrossboundaries/writingonwriting/timingold/.

- Karjo, Clara Herlina. 2017. “The Effects of ICT and Longhand Note-taking on Students’ Comprehension.” Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities 82: 64–66.

- Kincheloe, Joe L. 2011. “Critical Pedagogy and the Knowledge Wars of the Twenty-first Century.” In Key Works in Critical Pedagogy, 385–405. Bold Visions in Educational Research. Sense Publishers. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-6091-397-6_29.

- Kirschner, Paul A., and Pedro De Bruyckere. 2017. “The Myths of the Digital Native and the Multitasker.” Teaching and Teacher Education 67 (Oct.): 135–142.

- Leijen, Äli, Kai Valtna, Djuddah A.J. Leijen, and Margus Pedaste. 2012. “How to Determine the Quality of Students’ Reflections?” Studies in Higher Education 37 (2): 203–217.

- Lenhard, Wolfgang, Ulrich Schroeders, and Alexandra Lenhard. 2017. “Equivalence of Screen Versus Print Reading Comprehension Depends on Task Complexity and Proficiency.” Discourse Processes 54 (5–6): 427–445.

- Luo, Linlin, Kenneth A. Kiewra, Abraham E. Flanigan, and Markeya S. Peteranetz. 2018. “Laptop Versus Longhand Note Taking: Effects on Lecture Notes and Achievement.” Instructional Science 46 (6): 947–971.

- Mangen, Anne, and Lillian Balsvik. 2016. “Pen or Keyboard in Beginning Writing Instruction? Some Perspectives from Embodied Cognition.” Trends in Neuroscience and Education 5 (3): 99–106.

- Mangen, Anne, and Jean-Luc Velay. 2010. “Digitizing Literacy: Reflections on the Haptics of Writing.” In Advances in Haptics, edited by Mehrdad Hosseini. https://doi.org/10.5772/8710. InTech.

- Mangen, Anne, Bente R. Walgermo, and Kolbjørn Brønnick. 2013. “Reading Linear Texts on Paper Versus Computer Screen: Effects on Reading Comprehension.” International Journal of Educational Research 58 (Jan.): 61–68.

- Mueller, Pam A., and Daniel M. Oppenheimer. 2014. “The Pen Is Mightier Than the Keyboard: Advantages of Longhand Over Laptop Note Taking.” Psychological Science 25 (6): 1159–1168.

- Norman, Donald A. 1998. The Design of Everyday Things. London: MIT.

- Piper, Anne Marie, and James D. Hollan. 2009. “Tabletop Displays for Small Group Study: Affordances of Paper and Digital Materials.” In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, CHI ’09, 1227–1236. New York, NY: Association for Computing Machinery. https://doi.org/10.1145/1518701.1518885.

- Ragan, Eric D., Samuel R. Jennings, John D. Massey, and Peter E. Doolittle. 2014. “Unregulated Use of Laptops Over Time in Large Lecture Classes.” Computers & Education 78 (Sept.): 78–86.

- Sana, Faria, Tina Weston, and Nicholas J. Cepeda. 2013. “Laptop Multitasking Hinders Classroom Learning for Both Users and Nearby Peers.” Computers & Education 62 (Mar.): 24–31.

- Scheer, Andrea, Christine Noweski, and Christoph Meinel. 2012. “Transforming Constructivist Learning into Action: Design Thinking in Education.” Design and Technology Education: An International Journal 17 (3): 12.

- Selwyn, Neil. 2016. “Digital Downsides: Exploring University Students’ Negative Engagements with Digital Technology.” Teaching in Higher Education 21 (8): 1006–1021.

- Shotter, John. 1983. “‘Duality of Structure’ and ‘Intentionality’ in an Ecological Psychology.” Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour 13 (1): 19–44.

- Singer, Lauren M., and Patricia A. Alexander. 2017. “Reading Across Mediums: Effects of Reading Digital and Print Texts on Comprehension and Calibration.” The Journal of Experimental Education 85 (1): 155–172.

- Taipale, Sakari. 2014. “The Affordances of Reading/Writing on Paper and Digitally in Finland.” Telematics and Informatics 31 (4): 532–542.

- Thomas, Sharon, Danielle DeVoss, and Mark Hara. 1998. “Toward a Critical Theory of Technology and Writing.” The Writing Center Journal 19 (1): 73–86. https://www.jstor.org/stable/43442636.

- Tynjälä, Päivi. 1998. “Writing as a Tool for Constructive Learning: Students’ Learning Experiences During an Experiment.” Higher Education 36 (2): 209–230. http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ehh&AN=1030879&site=ehost-live.

- van der Velden, Maja. 2016. “Design as Regulation.” In Culture, Technology, Communication: Common World, Different Futures, edited by José Abdelnour-Nocera, Michele Strano, Charles Ess, Maja Van der Velden, and Herbert Hrachovec, 32–54. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- van der Velden, Maja, Suhas Govind Joshi, and Alma Culén. 2018. “Designed for Learning: Experiences with the Intensive Course Format in Informatics.” In Proceedings from the Annual NOKOBIT Conference Held at Svalbard the 18th–20th of September 2018, Vol. 26. https://ojs.bibsys.no/index.php/Nokobit/article/view/555.

- Wrigley, Stuart. 2019. “Avoiding ‘de-Plagiarism’: Exploring the Affordances of Handwriting in the Essay-writing Process.” Active Learning in Higher Education 20 (2): 167–179.

- Young, Jefferey R. 2006. “The Fight for Classroom Attention: Professor vs. Laptop.” Chronicle of Higher Education 52 (39): A27–A29. http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ehh&AN=21116420&site=ehost-live.

![Figure 1. A mind-map of a lecture, made by one of the students [47].](/cms/asset/3ce23dfd-ce9d-4807-a212-b0080c51a280/cthe_a_1863347_f0001_oc.jpg)

![Figure 2. Mind-map used to structure a handwritten essay [84].](/cms/asset/8961ae41-0c97-463e-b3ce-691d22270449/cthe_a_1863347_f0002_oc.jpg)