ABSTRACT

Through an evaluation of an institution-wide curriculum change process, this paper analyses how strategic policy is variously enacted in departmental communities. Linguistic ethnography of public, institutional and internal policy documents illuminates departments’ engagement with the change process. With curriculum change positioned as a disorienting dilemma, transformational learning theory provides a lens to analyse the departments’ alignment with the intention of the curriculum change policy. The paper explores the extent to which departments transformed from a disciplinary content-based and high-stakes examination approach to the curriculum to incorporating broader institutional aims and active learning theories into disciplinary language, pedagogy and practices. Three stages of engagement are identified through an evaluation rubric, offering a framework to assess curriculum change initiatives. Implications for educational leaders include the need to integrate institutional strategy with disciplinary experts and expertise and the importance of language adoption as a precursor to implementation.

Introduction

A new regulatory framework in England has led to significant changes in how universities organise, deliver and account for their educational offering (Filippakou and Tapper Citation2019). New requirements for reporting data have forced institutions to collect, analyse and manage data on an unprecedented scale. National policies on transparency of data and real-time oversight are feeding into institutional strategies and creating new requirements for evaluation and impact reporting (Strike Citation2017).

This regulatory turn is part of a long-running discourse of ‘quality’ in higher education (Gibbs Citation2012) which plays out through policy documents, institutional processes and individual practices, but the degree of enactment is less well-understood. This follows decades of governmental desire for more strategic activity around learning and teaching, but this coincided with little evaluation (Gibbs Citation2001, 3), particularly at institutional levels (Saunders, Trowler, and Bamber Citation2011). However, many institutions are making large-scale changes to various aspects of the educational experience in part in response to new regulatory requirements such as rationalising the relationship between teaching and research (Fung Citation2017); changes to marking and grading schemes (Ratcliffe Citation2019); and attainment gaps across socio-demographic characteristics (Ross et al. Citation2018).

This paper reports on a project that is part of a wider research and evaluation exercise of curriculum reform at a UK-based research-intensive institution. The educational effects of curriculum change are notoriously difficult to evaluate due to a large number of variables and the lengthy timeframes (Blackmore and Kandiko Citation2012). Thus, this paper reports on a first phase which aims to investigate not only the educational effects of institution-wide curriculum change, but also the impact on institutional and disciplinary culture. This follows in the tradition of reporting on multi-year curriculum change analysis such as that done in Finland (Annala and Mäkinen Citation2017), Australia (Davies and Devlin Citation2007) and South Africa (Shay, Wolff, and Clarence-Fincham Citation2016). The study reported here offers a snapshot in time, capturing transformation in process.

What is the curriculum?

The curriculum can be viewed narrowly ‘as a set of purposeful, intended experiences’ (Knight Citation2001, 369) or more expansively to include purpose, content, alignment, scale, learning activities, assessment, physical environments and learning collaborators, with ways of thinking and practising as a conceptual framework (Barradell, Barrie, and Peseta Citation2018). Hounsell and Anderson (Citation2009) also raise the importance of the socio-epistemic context in which the curriculum is taking place. Definitions of the curriculum vary across disciplines (Short Citation2002), academic staff (Fraser and Bosanquet Citation2006), as well as within and across national contexts (Lattuca and Stark Citation2009). Different models of the curriculum coincide with different conceptions of the curriculum, including Biggs’ (Citation1996) constructive alignment model, Barnett and Coate’s (Citation2005) knowing, acting and being framework, and Bernstein’s (Citation1975, Citation2000) work on ‘what counts as valid knowledge’ and ‘framing’.

This study takes disciplinary thinking and knowing (Barradell, Barrie, and Peseta Citation2018) and their changing curricula framing of ‘what counts as knowing’ (Bernstein Citation1975, Citation2000) into account when conceptualising the curriculum. However, the methodological approach looks at a process that centres on a narrower definition of curriculum as an ordered set of purposeful intended consequences (Knight Citation2001). Moreover, this study also includes engagement with curriculum reform policy and enactment of curricular change, going beyond a tightly focussed, process-centred ‘intended curriculum’ based definition.

Despite the fluidity around defining the curriculum, there is a recurrent discourse that the curriculum is no longer fit for purpose, is ‘old, pale and stale’ and in need of reform. Curriculum reform is contentious, as it ‘is a highly complex social process, which is related to individual, disciplinary and institutional identities and reflects the power relations within the academy’ (Annala and Mäkinen Citation2017, 1954). The dynamics of curriculum reform involve change from above (top-down and policy influenced) and from below (bottom up and focused on understanding and enactment) (McGrath and Bolander Laksov Citation2014) and balance between ‘introjection’ (internal disciplinary conceptions of the curriculum) and ‘projection’ (external demands for curriculum change) (Bernstein Citation2000). For individuals, there is an interplay between participation and reification (Wenger Citation1998), as curriculum change is disruptive whether it comes from above or below.

Curriculum reform seems to come in cycles across regions and institutional types (Hicks Citation2018; Blackmore and Kandiko Citation2012). In a cross-national comparison, Shay (Citation2015) found very different logics underlying reform discourses with different conceptualisations of the need for reform as well as different reform solutions. This divergence is also found within institutions, where there is ‘substantial educational crosstalk taking place, whereby people are experiencing a communicative mismatch in terms of negotiating the meaning of change initiatives’ (McGrath and Bolander Laksov Citation2014, 139). Keesing-Styles, Nash, and Ayres (Citation2014) identified the challenge of getting teaching staff to ‘feel a degree of ownership and relevance of the initiative’ (506) in a top-down led institutional curriculum renewal project. This highlights the need for not just top-down leadership but for bottom-up participation to engage front-line staff in meaningful institution-wide change efforts.

Demands for curriculum reform stem from gaps between intentions and actions in the curriculum (Mälkki and Lindblom-Ylänne Citation2012), as well as linking with outcomes. This results in calls for more empirical analysis of curriculum reform (Clegg Citation2016). At the schooling level in England, the Office for Standards in Education, Children's Services and Skills (Ofsted) Education Inspection Framework (Citation2019) consultation summarised their planned approach:

Inspectors will consider the extent to which the school’s curriculum sets out the knowledge and skills that pupils will gain at each stage (intent). They will also consider the way that the curriculum selected by the school is taught and assessed in order to support pupils to build their knowledge and to apply that knowledge as skills (implementation). Finally, inspectors will consider the outcomes that pupils achieve as a result of the education they have received (impact). (40)

Curriculum review in context

This study was conducted in a highly devolved, mid-size urban research-intensive institution in the UK two years into an ambitious programme of change, supported by a top-down, policy driven, nine-year investment plan. It aims to deliver world-leading education, rather than responding to specific institutional or sector challenges. This was informed by a growing awareness that traditional ways of teaching in higher education, which is dominated by transactional didactic lecture delivery (Barnett, Parry, and Coate Citation2001), do not benefit students as much as they should and are not as inclusive and engaging as they could be. Consequently, there has been a discipline-based, pedagogical research-driven change in science education (Singer, Nielsen, and Schweingruber Citation2012) with a shift to more authentic teaching through research (Wald and Harland Citation2017) and from passive to active learning (see White et al. Citation2016; Talbot et al. Citation2016; Wieman and Gilbert Citation2015; Freeman et al. Citation2014 and Deslauriers, Schelew, and Wieman Citation2011).

Literature shows that students work and learn better in an inclusive teaching environment with respect to interactive classroom communities and an appreciation of the value of different backgrounds and opinions, and social culture on campus (Gurin et al. Citation2002; Easterbrook and Parker Citation2006; Ippolito Citation2007; Scudamore Citation2013). Indeed, there is evidence that active learning preferentially closed the learning gain gap for underrepresented minority students, possibly because of increased self-efficacy and a greater sense of social belonging (Ballen et al. Citation2017). This is augmented by inventive use of technology enhanced learning opportunities which can be highly effective and engaging (Daniela, Strods, and Kalniņa Citation2019) and from which students derive high levels of satisfaction (Tamim et al. Citation2011).

The curriculum change programme also reflected a desire to build on research showing the benefits of working with students as partners in curriculum design (Matthews and Mercer-Mapstone Citation2018; Bovill and Woolmer Citation2019). This approach aims to build a stronger sense of inclusive community and address student satisfaction while delivering modern, innovative evidence-based curricula geared towards developing graduates that can tackle complex, global problems. The institutional change programme is based on four pillars:

(1) Assessment Reform: A review of curricula and assessment

(2) Active Learning: An evidence-based transformation of pedagogy, to make teaching more discovery-based

(3) Diversity and Inclusion: The fostering of an inclusive and diverse culture and sense of belonging

(4) Digital and Technology Enhanced Learning: The development of online and digital tools to enhance curricula, pedagogy and community

Two years into this strategic programme the entire undergraduate curricula offering has been reviewed, standardising credit frameworks, making space for interactive teaching and the introduction of innovative pedagogies, addressing and aligning assessment strategies and considering digital innovation and technology enhanced learning. This has been supported by additional central funding to both free-up existing disciplinary experience and bring in new pedagogic expertise to support the review process; every department bid for, and received, extra funding tailored to support the review.

In some departments, this top-down strategic approach was aligned with significant bottom-up desire for change in terms of intent and implementation, modernising practice and responding to disciplinary development and progress. In some departments, there were also concomitant external pressures from professional and regulatory bodies for curriculum development to meet changing professional expectations and needs. While in other departments there was resistance to change, this was mitigated by a reluctance to miss the opportunity for extra funding that engagement with the process afforded. This signals a patchy alignment of intent which influenced implementation. Even in these more ‘resistant’ departments there were often pockets of enthusiasm desiring change, however, these more enthusiastic individuals were not always involved in, or empowered by, the review process. These variations highlight the need for an institution-wide approach to change, rather than relying on course or departmental level impetus.

Policy enactment and institutional learning

This project draws on Ball et al.’s (Citation2012) work on policy enactment as a process contextualised by institutional cultures with a variety of participants, comprising dynamic relationships with policy processes and documents. Rather than focus on specific programme changes or their effectiveness, this paper explores how, and to what degree, a major institution-wide strategy was translated into departmental contexts. The focus is on the extent to which evidence-based strategies improve teaching, learning and the student experience are embraced by staff within departments. The strategies involve changes to structures and policies, but to be fully adopted require changes to how staff teach and conceptualise the curriculum, shifting from an instrumental view of the curriculum as a set of content to be delivered to ‘learning to understand the meaning of what is being communicated’ (Mezirow Citation1997, 6).

This shift follows a change in focus from teaching to learning, and from staff and students as passive to active agents in the curriculum. The curriculum review process becomes one of collaborative pedagogisation, ‘the establishment of a certain type of social relation which involves an attempt to modify the sociocognitive and practical frameworks of social agents engaged in practice … how power relations and social control operate within processes of policy implementation’ (Stavrou Citation2016, 789).

This approach positions engagement with the policy texts in the curriculum review process as a form of transformational learning, ‘a deep, structural shift in basic premises of thought, feelings, and actions’ (Transformative Learning Centre Citation2016, para 2), drawing on the work of Habermas (Citation1984) and Freire (Citation1970, Citation1973). ‘It is the kind of learning that results in a fundamental change in our worldview as a consequence of shifting from mindless or unquestioning acceptance of available information to reflective and conscious learning experiences that bring about true emancipation’ (Simsek Citation2012, 201). Through exploring transformational learning at an institutional level, curriculum review can be a ‘disorienting dilemma’, with discomfort and a strong emotional response an expected part of the process. However, the degree to which institutional curriculum change policy is adopted in departmental cultures, leading to transformational approaches to education, or stays as mere rhetoric in marketing brochures, is rarely explored (Blackmore and Kandiko Citation2012).

This paper evaluates the degree of departmental engagement with an institution-wide curriculum review policy. It uniquely uncovers a process which offered top-down and bottom-up active involvement in changing curriculum intent and implementation. It analyses the way departments engaged with the language and intention laid out in high-profile strategy documents, which represent a ‘negotiated covenant’ of intent and implementation between the institution, departments and students. This offers insight into how top-down policies are variously adopted within departments, as well as the role of disciplinary cultures, practices and external forces in impacting institutional change. The approach detailed here offers both an evaluative method that can be applied across institutions as well as an authentic curriculum change process that can be part of a transformative learning experience for staff and students.

Methodology

A discourse analysis approach is used on data from three linked sources to explore reform processes and their enactment, uncovering patterns of language use which ‘embody shifts in perspectives and values’ (Baldwin Citation1994, 128). Policy texts and institutional documentation are therefore discursively analysed and contrasted with each other, to capture the principles and underlying assumptions structuring accounts of policy development and enactment. By discourse we mean a regular, recurrent pattern of language that both shapes and reflects the user’s basic intellectual commitments (Sparkes Citation1990); discourses function to scaffold performances of social activities and to scaffold human affiliations (Gee Citation1999).

Discourses are part of teaching and learning processes and can be understood as a set of shared understandings, assumptions, theories of action and values around a common phenomenon (Trowler and Cooper Citation2002). Although they may identify shared understandings, any text is made up of multiple discourses and does not necessarily represent a single voice.

The primary sources include three texts, summarised in . The first is an externally available but institutionally-focused Learning and Teaching Strategy representing top-down intent; next are internally-based Curriculum Redesign Forms detailing the intent of the bottom-up change and review process for each department over a two-year period; and individual Programme Specifications, which fulfil legal contractual obligations for delivery, external marketing and internal quality assurance needs, functioning as socially-constructed ‘policy objects’ (Sin Citation2014). The latter represent a mutually negotiated covenant of intent and implementation which have both official contractual obligations and form a codified representation of disciplinary intent between teachers and students, linking the top-down and bottom-up approaches. The institutional Learning and Teaching Strategy sets out the intent of the curriculum, and the Curriculum Redesign Forms and Programme Specifications detail the extent to which the Strategy has been enacted into local contexts. We analysed data from 15 undergraduate departments across three Faculties.

Table 1. Texts used in discourse analysis.

The texts were analysed using linguistic ethnography which is ‘an interpretive approach which studies the local and immediate actions of actors from their point of view and considers how these interactions are embedded in wider social contexts and structures’ (Copland and Creese Citation2015, 13). This is a subfield of discourse analysis, an underutilised methodology in higher education research (Tight Citation2003). Linguistic ethnography goes beyond the ‘ethnography of communication’ (Hammersley Citation2007), exploring the way language is used and how it impacts on social processes and vice versa and sees language and social life as mutually shaping (Rampton et al. Citation2004). We took on board principles of critical discourse analysis as an emancipatory tool (Liasidou Citation2008), a combination of microanalysis of texts alongside macroanalysis of the broader social formations the texts are part of (Luke Citation2002).

This analysis looks at the planned, or intended, curriculum by focusing on the curriculum documentation (Bernstein Citation2000), which capture a negotiated representation of intended change. The Learning and Teaching Strategy document was first analysed and fed into the development of an evaluation rubric based on its key principles. Analysis explored the extent to which these principles were adopted in the Redesign Forms and Programme Specification documents, representing a possible ‘transformational’ approach to understanding the curriculum as a site of pedagogical reform. Additionally, these were analysed for the degree to which they appeared to be completed to pass a perceived minimum quality assurance threshold or as opportunity to authentically engage with the curriculum reform; the level of competence with their understanding of the principles drawn from the learning and teaching strategy; and the degree of compliance to meaningfully engage in the process.

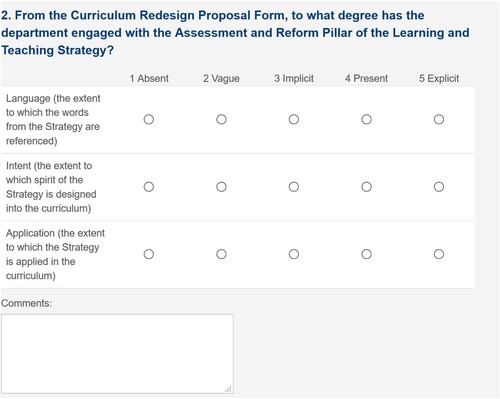

Two aspects of the analysis are explored in this paper. The first is the analysis of engagement with the four pillars of the learning and teaching strategy, using the Curriculum Redesign Proposal form, exploring:

Language (the extent to which the words from the Strategy are referenced)

Intent (the extent to which spirit of the Strategy is designed into the curriculum)

Application (the extent to which the Strategy is applied in the curriculum)

This resulted in an initial 12 indicators for each department (each of the four pillars evaluated by Language, Intent and Application), see for an example.

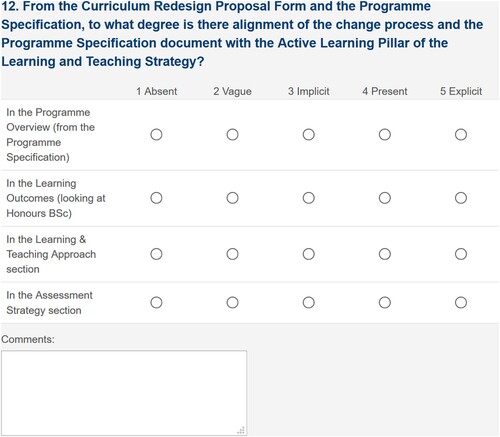

We also analysed the alignment of the Curriculum Redesign Proposal form and the Programme Specification, focusing on the sections on Programme Overview, the Learning Outcomes, the Learning and Teaching Approach and the Assessment Strategy. This led to another 16 indicators (each of the four pillars of the Learning and Teaching Strategy evaluated across the four key sections of the Programme Specification document), see for an example. In this paper we analyse these 28 indicators in the evaluation rubric.

In the evaluation rubric relevant section of the documents were judged on a scale of Absent, Vague, Implicit, Present, Explicit. The adoption of a categorical scale was used to identify patterns, acknowledging that the assigned numerical value (1–5) did not represent a comparable difference in measure. Thus, the analysis of texts was complemented by material-oriented analysis, including how policies are enacted (Ball, Maguire, and Braun Citation2012; Smith Citation2005). This approach allows for intentions of policies to be drawn out, as ‘the significance of language is what it is thought to be used for, not what it is thought to mean’ (Saarinen Citation2008, 720), in the spirit of work on the scholarship of curriculum practice (Hubball and Pearson Citation2011). The analysis has been conducted across each undergraduate teaching department, independently by two researchers, one with extensive experience with the review process and another who has not been involved previously. The rubric was piloted on two diverse departments and periodic checks confirmed its validity.

Focusing solely on texts is a limitation of this approach, as using linguistic ethnography does not account for the lived experience of curriculum review, less visible ways of delivering the curriculum or for change over time. However, this does allow insight into one facet of delivering on the intentions of curriculum strategy and provides a tool for evaluating whether such intentions are codified in institutional documentation.

Findings

Overall, analysis of all 28 indicators across each of the four pillars of the learning and teaching strategy, there were higher levels of engagement with the ‘language’ from the strategy than with ‘intent’ or ‘application’. This pattern was seen across each of the four pillars, with on average a full category drop (i.e. from ‘present’ to ‘implicit’) when looking at engagement with ‘language’ to ‘application’. This is seen in the following extract from a Curriculum Redesign Form regarding the Diversity and Inclusion pillar:

Regarding inclusivity, we have endeavoured to retain a wide range of different assessment types, so students with any weaknesses in one type of assessment will benefit from the diversity offered elsewhere.

Framing

Analysis of the first 12 indicators (exploring the engagement with the Strategy in the Curriculum Redesign Forms) across the four pillars, there was more engagement with Assessment Reform and Active Learning pillars than the other two, with the language from the strategy being ‘Explicit’ or ‘Present’ for all departments. These may signal areas where staff in departments feel a greater sense of ownership of the curriculum. An example from a department in the Faculty of Engineering includes ‘Active learning to promote reflection, critical thinking, problem solving, teamwork and communication’ through project work, small group team-based learning and labs, in which ‘practical experiments brought back into each of the modules rather than as a stand-alone module. Allows students to compare theoretical calculations vs. real measurements, and explore the possible reasons behind discrepancies’.

The ‘Intent’ was somewhat less evident, being ‘Implicit’ in several departments. However, when it came to ‘Application’, there was a more mixed picture, with about a fifth of departments explicitly embedding the strategy into the curriculum, and a similar proportion only vaguely doing so. This shows the challenge of thoroughly enacting a strategy, although the general ethos may be accepted. There is relatively good alignment of language suggesting commonality of definition and strategy, this is less aligned at the level of explicit intent and even less reflected in explicit implication, although the common language may indicate the start of a process of alignment between bottom-up and top-down approaches.

In contrast, the engagement with the pillars of Diversity and Inclusion, and Digital and Technology Enhanced Learning were much lower than the other two pillars. For Diversity and Inclusion, about half of all departments adopted the language explicitly, and it was absent from the rest. Similar patterns of decreased evidence of engagement with intent and application were seen, but at even lower levels than with the Assessment Reform and Active Learning pillars. The theme of Diversity and Inclusion in relation to the curriculum is a new concept for many staff at the institution. These findings echo those of Jessop and Williams (Citation2009):

that the Higher Education (HE) curriculum is a powerful but under-utilised tool in developing a more inclusive experience for all students. They [the authors] further suggest that legal and institutional procedures are not a strong enough framework to combat racism, and that campuses with few minority ethnic students need to take a much more intentional approach to transforming the institutional culture. (95)

Similarly, departments seemed to struggle to embed the ideas around Digital and Technology Enhanced Learning into the curriculum, with this being absent from almost all departments. This may be because Digital and Technology Enhanced Learning has historically been delivered by professional units and academic departments may have not seen it as their responsibility. It also may be that those involved in digital education are more removed from the actual delivery and there may be subsequent engagement when the curricula are operationalised, but the evaluation of the curriculum documents shows that this pillar is not being embedded into departmental policy documents. However, given recent shifts in educational provision in light of the Covid-19 pandemic on-line teaching and assessment is being adopted on a global scale, but how embedded these practices become awaits to be seen. The findings from the pillars of Diversity and Inclusion and Digital and Technology Enhanced Learning suggest that departments stayed in comfort zone of the discipline but engaged with the shift from teaching to learning. However, even engaging with the language can lay the groundwork for future engagement, as was seen in the Covid-19 pandemic induced adoption of digital and technology-enhanced learning.

Alignment

Through exploring the alignment of the Strategy and the Curriculum Redesign Form with the Programme Specification, we found similar patterns as detailed above across the four pillars. There was more engagement with the Assessment Reform and Active Learning pillars. Almost all departments were able to embed these pillars of the strategy into the student-facing Programme Specification document, although with varying degrees of engagement with the ‘intent’ of the strategy. For example, a department from the Science Faculty noted in the Programme Specification:

A variety of different summative assessment methods is used, including:

– Written examinations

– Short, individual tests

– Group assignments and projects

– Individual Projects

– Online tests and quizzes

– Oral presentations

– Poster presentations.

This indicates engagement with the Assessment Reform pillar, identifying multiple forms of assessment. However, the dependency in high-stakes exams remains for this department: ‘In year 1 the end-of-year examination is usually worth 70 percent of the module; this typically increases to 80 percent in year 2 and 90 percent in year 3’.

Even if the full alignment was not in place, the linguistic engagement with Assessment Reform and Active Learning pillars was not seen for Diversity and Inclusion and Digital and Technology Enhanced Learning. These were almost entirely absent from the Programme Specifications, except for two departments out of 15 reviewed. This may signal how struggling with the adoption of the language, as noted in the Framing findings, hindered departments from being able to put the intention of the Strategy into practice in describing the course offering.

Of the different sections of the Programme Specification, the least engagement with the Strategy was in the Learning Outcomes section, which was the lowest across all four pillars, and almost entirely absent for Diversity and Inclusion, and Digital and Technology Enhanced Learning. This is somewhat concerning, as these are a central tenant of much curriculum design. This may signal an area where the departmental disciplinary curriculum focus supersedes institutional policy drives.

Departments

Across departments, we noticed different levels of engagement with the Strategy. Looking at the patterns of engagement, and complimenting with numerical analysis, three broad clusters emerged. Given the complexity of the curriculum change as detailed in the texts, we found engagement could come in different forms and across different areas of the Strategy, but that enacting changes strongly in a few areas or generally across all indicated that departments took on board the intention of the Strategy. About a third were categorised as ‘active’, being highly engaged with the process, with the intention of the themes applied in concrete actions and followed through with specific evaluation plans. For these departments, the disciplinary content was merged with adoption of the themes from the Strategy. This is seen in a department from the Medical Faculty, where the Programme Overview in the Programme Specification states:

This programme is delivered through a range of teaching methods, including small group teaching, team-based learning, interactive lectures, technology-enhanced learning, laboratory and clinical skills classes and case-based learning. You gain clinical experience early in your degree, giving you direct contact with the diverse local patient population and enabling you to apply skills learnt in the classroom at an early stage.

Another third of departments were labelled as ‘engaged’ with the change process, with the intention of the strategic themes acknowledged and various innovations proposed to embed them. This middle group did not show the level of breadth or depth of change and reflection of the Strategy as the active departments but did indicate taking aspects of the Strategy on board. However, a final third of departments took a ‘passive’ approach, with minimal engagement with the Strategy and a focus on structural issues such as reconfiguring modules and credit frameworks. Their Curriculum Redesign Forms focused on disciplinary content rather than the pillars of the Strategy.

Discussion

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the Curriculum Redesign Forms focus on the regulatory aspects of curriculum reform, including meeting standardised academic regulations and structurally aligning modules and programmes. The Programme Specifications show that a traditional high-stakes exam-based assessment culture is slow to change and indicate a challenge of documenting a commitment to diversity and inclusion and articulating digital engagement. Through this analysis, the ‘language’ of reform only provides a proxy indicator of engagement with the process, but nevertheless offers valuable insight into levels and degrees of policy enactment across departments. The documents analysed capture a codified mutual understanding of both curriculum intent and implementation, and the language is a proxy indicator of the alignment of bottom-up and top-down intent and implementation. Departments varied from disciplinary content-based views of the curriculum to incorporating institutional aims and active learning theories, some managing to embed this within their disciplinary context.

Variation across pillars

Looking at the pillars of the Strategy, there seemed to be broad engagement with the idea of assessment reform, but the exam-based culture is still embedded culturally, administratively and institutionally. For Active Learning there were two distinct strategic approaches. The first built on relatively established active learning approaches in the curriculum, usually combined with research engagement and building on this known approach to encourage faculty already engaging with similar pedagogy to adopt it more explicitly. The second was to start with a redesign of the first-year curriculum with plans to integrate pedagogically experienced staff to make changes in subsequent years. There were many vague mentions of piloting active learning in specific modules, but with few details. However, the intention of these two pillars has been taken on board across all departments at least to some extent, signalling a willingness to engage with the Strategy.

Regarding Diversity and Inclusion, it was only occasionally mentioned and rarely applied in practice. And although in many cases it was only implicitly explored, some of the practices mentioned in Assessment Reform and Active Learning may have positive effects on diversity and inclusion, even if this was rarely articulated. These include scaffolding, small group and team-based learning activities as well as multiple forms of assessment (see Haak et al. Citation2011; Dawkins, Hedgeland, and Jordan Citation2017; Gibson, Jardine-Wright, and Bateman Citation2015). More broadly, the curriculum review process sparked interest in Diversity and Inclusion in some departmental levels. An example was a departmental project to decolonise reading lists through exploring the geographic diversity of authors, subsequently taken on board at institutional level through the library as part of wider responses to the Black Lives Matter movement. This shows how even pockets of engagement can lead to wider curriculum changes.

For Digital and Technology Enhanced Learning, there was little engagement, despite digital activities being central to many programmes, such as Computing. Similarly with Diversity and Inclusion, the pandemic accelerated engagement with Digital and Technology Enhanced Learning. This similarly was aided by pockets of engagement with the pillar that helped lead the institutional response.

This highlights how understanding and adopting the language of curriculum reform is an initial requirement for translating policy into disciplinary context. Engaging with the discourse of the curriculum change was always evident in departments that also captured the intent and went on to apply the Strategy in their contexts. Thus, interpreting or translating the language is an act of reflection and transformation which ‘can lead developmentally toward a more inclusive, differentiated, permeable, and integrated perspective’ (Mezirow Citation1991, 155).

Departmental differences

In comparing across departments, it is necessary to acknowledge they came from different starting points in the curriculum review process. There were also variations in wider departmental engagement with the reform process, with whole departmental engagement in some cases, and others where a select group of individuals led on it. The findings reflect the stages of curriculum reform, where we see language comes first, but also the importance of intent to be able to turn the language into application. This may also be a consequence of the top-down driver for reform, versus a disciplinary or internal departmental bottom-up driver.

This also highlights the importance of agency for those implementing the curriculum change. Staff have different perspectives on curriculum and the drivers for change. Roberts (Citation2015) found curriculum orientations were found to shape academics’ responses to educational change. However, agency is necessary to be able to engage in critical reflection about the curriculum, potentially leading to changes in frames of reference: ‘sets of fixed assumptions and expectations (habits of mind, meaning perspectives, mindsets)’ (Mezirow Citation2003, 58–59). This restructuring of the curriculum in the context of the discipline is necessary to go beyond superficial mimicry in practice and outcomes. For students to be able to engage in transformative learning, they need to be able to contextualise their learning in disciplinary pedagogy.

For the group of ‘passive’ departments, it seems they engaged with the language of the Strategy enough to be compliant. This linguistic mimicry may be the start of a codified agreement that is a prerequisite for change. There was adoption of regulatory and structural changes, and some engagement with educational change, but disciplinary knowledge dominated. This was seen most evidently in the Programme Specification, which largely focused on discipline content-based learning outcomes. Drawing on the interest in disciplinary content could be a way to shift passive departments to be more engaged – for example highlighting the role of diversity and inclusion to the subject matter, such as through gendered approaches to measuring safety in engineering or the impact of ethnicity in artificial intelligence programming.

The group of ‘engaged’ departments adopted the language of the Strategy as well as the intent to implement new educational practices. This was evidenced in assigning selected modules team-based learning approaches or innovative assessment types. There was some integration with Diversity and Inclusion and some Digital and Technology Enhanced Learning into the curriculum. However, this group held back from fully engaging the disciplinary content and practices with the curriculum change. For some departments, there was more importance placed on alignment with accrediting and professional bodies than with the institutional strategy. As with the passive departments, this external driver could be way to push the engaged departments into being fully active with the Strategy, through highlighting links between professional requirements, such as enhanced practical skills and the active learning elements of the Strategy.

This disciplinary integration was seen in the group of ‘active’ departments, who used the Strategy as an opportunity to engage with change process, prepare the curriculum for the future and adopt practices relevant for a diverse student body. There was also engagement with external drivers, such as in Medicine responding to changing wider social and professional initiatives. This was seen through new approaches to learning and assessment such as longitudinal integrated clerkships (see McKeown et al. Citation2019) which integrate and empower students’ learning within the community in an authentic professional context. This explicit, active engagement suggests alignment of top-down and bottom-up intent, and in some cases implementation and integration, with wider disciplinary and professional context and possibly significant transformational change.

Educational leadership of curriculum change

This study identified the challenge of embedding strategic aims into Learning Outcomes, the foundation for an aligned curriculum. Staff are largely unskilled at writing learning outcomes. Staff with pedagogic expertise within departments, both new and existing, may not have been able to influence programme-level Learning Outcomes, which was the focus of this study. This may vary at module level. Historically, programme-level Learning Outcomes have been based on disciplinary objectives rather than broader educational outcomes. For most departments, there was a stronger influence of Professional, Statutory, and Regulatory Bodies (PSRBs) in the programme-level learning outcomes.

This shows the challenge of an institution-wide Strategy, when for many departments the curriculum is centred on the discipline, with little institutional influence. Language was seen to be a necessary minimal activity to bring departments on board but engaging with the intent of the curriculum seemed to function as a threshold concept for departments (Meyer and Land Citation2006). Reflecting on the intent of the Strategy through a disciplinary lens was seen in the ‘active’ departments as a form of collective transformational learning, with curriculum review and the quality assurance process as a necessary and perhaps driving ‘disorientating dilemma’. This is evident in the Curriculum Redesign Forms where several active departments reflected on the challenging, but ultimately worthwhile, journey of deeply engaging with the change process.

Intent also shows why leaders need engagement and buy-in from departmental academics for successful curriculum change, as a Strategy needs to be realised in disciplinary pedagogy which can only be done by disciplinary experts. If the process is just top down, as happens with many curriculum change initiatives (Blackmore and Kandiko Citation2012), departments are stuck at mimicry stage. Integration with the discipline is essential for transformation, highlighting the need for key translators, such as disciplinary pedagogical experts, educational developers and educational technologists. Staff in such roles were highlighted as integral to understanding the Strategy and adopting changes in many of the accounts from the active and engaged departments. Conversely, several of the passive departments described narrow curriculum review teams with little to no engagement from such staff. These translators are uniquely placed to apply the Strategy to the disciplinary context, facilitating the integration of bottom up interest and engagement with the intention from the top down structure.

Implications and limitations

Large-scale curriculum change is a vast undertaking, in terms of cost and time, but is rarely evaluated. This study provides an evaluation tool for the adoption of changes ‘as intended’ at a given point in time. Reporting on a long-term project, this multi-stage evaluation offers insight into an area of increased interest for research and practice.

Inevitably with multi-year change projects there are staff changes at senior levels, which impact support and direction of reforms and it is useful to have evaluation of stages completed. Whilst reviewing a work in progress, this approach creates an evidence-based approach to taking on board new leadership and additional influences, such as the pandemic and the Black Lives Matter movement. For example, the institutional response to these has been aided by the curriculum review project and the evaluation, through recognising areas of strength and opportunity.

There are limitations of a linguistic ethnographic approach, in that those completing or controlling the documentation process may or may not be the same people responsible for operationalising actual changes and there is the possibility that ‘policy terminology’ was adopted as mimicry rather than an actual engagement as a strategic attempt to gain political capital or an instrumental approach to address bureaucratic processes. Thus, apparent engagement with the policies may, or may not, be directly related to the will for, and practice of, actual curriculum change and innovation. However, the documents used for the ethnography have the potential to represent the codified, negotiated understanding between top-down and bottom-up approaches, thus acting as an important linguistic indicator of intent and implementation.

As with all ethnographic research, observations and interpretations are situated in time and place. These may change as additional data comes available or external events such as the pandemic and the Black Lives Matter movement arise. The linguistic approach adopted captures a snapshot in time, but also allows for the possibility of reviewing additional texts in the future. Further, although focusing on documents limits the breadth of how the curriculum can be explored, those such as Programme Specifications have longevity and long-term impact, as they are valid for the duration of a student’s course. Future research will explore aspects of implementation, application and outcomes as well as how the curriculum review supported the institutional response to new changes.

Conclusion

This study shows transformation in planning and thinking about the curriculum. Initial analysis of the curriculum review process, particularly when done ‘at scale’, suggests it can be a disorienting dilemma that helps ‘drive’ transformational change (Mezirow Citation2003). Departments that integrated disciplinary content with the pillars of reform, particularly Assessment Reform and Active Learning, managed to put the intention of the Strategy into practice. For other departments, the more ‘superficial’ linguistic mimicry or echoing could be considered (perhaps at best) as indication of engagement at the level of points of view, while more integrated use of terminology and communicative adoption of the associated underlying intent could be considered as engagement at the deeper level habits of mind (Mezirow; Habermas Citation1984). The challenges of integrating Diversity and Inclusion across departments shows the slow pace of change, but also that at least acknowledging and referencing such topics may be the start of a transformative journey.

This research provides a tool for institutions looking to evaluate curriculum change initiatives and offers examples of what facilitates transformative education aims becoming embedded in disciplinary practices. The Covid-19 pandemic has shown how at least having the groundwork in place for adopting Digital and Technology Enhanced Learning can be useful when external drivers require rapid change. The challenge of the pedagogic response to the pandemic might be a second disorientating dilemma that may accelerate and broaden the transformation started by the Learning and Teaching Strategy and the curriculum review process. This research represents the beginning of a multi-stage evaluation exploring the impact of a transformational approach to curriculum change on student learning and the interaction of the pillars, such as the potential of greater adoption of Digital and Technology Enhanced Learning to reach a more diverse audience and facilitate Active Learning in a more flexible way.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Annala, J., and M. Mäkinen. 2017. “Communities of Practice in Higher Education: Contradictory Narratives of a University-Wide Curriculum Reform.” Studies in Higher Education 42 (11): 1941–1957.

- Baldwin, G. 1994. “The Student as Customer: The Discourse of ‘Quality’ in Higher Education.” Journal of Tertiary Education Administration 16 (1): 125–133.

- Ball, S. J., M. Maguire, and A. Braun. 2012. How Schools Do Policy: Policy Enactments in Secondary School. London: Routledge.

- Ballen, C. J., C. Wieman, S. Salehi, J. B. Searle, and K. R. Zamudio. 2017. “Enhancing Diversity in Undergraduate Science: Self-Efficacy Drives Performance Gains with Active Learning.” CBE—Life Sciences Education 16 (4): ar56.

- Barnett, R., and K. Coate. 2005. Engaging the Curriculum. Maidenhead: SRHE/Open University Press.

- Barnett, R., G. Parry, and K. Coate. 2001. “Conceptualising Curriculum Change.” Teaching in Higher Education 6 (4): 435–449.

- Barradell, S., S. Barrie, and T. Peseta. 2018. “Ways of Thinking and Practising: Highlighting the Complexities of Higher Education Curriculum.” Innovations in Education and Teaching International 55 (3): 266–275.

- Bernstein, B. 1975. Class, Codes and Control. Vol. 3. Towards a Theory of Educational Transmissions. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

- Bernstein, B. 2000. Pedagogy, Symbolic Control and Identity: Theory, Research and Critique. New York: Rowman and Littlefield.

- Biggs, J. 1996. “Enhancing Teaching Through Constructive Alignment.” Higher Education 32 (3): 347–364.

- Blackmore, P., and C. B. Kandiko. 2012. Strategic Curriculum Change in Universities: Global Trends. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Bovill, C., and C. Woolmer. 2019. “How Conceptualisations of Curriculum in Higher Education Influence Student-Staff Co-creation in and of the Curriculum.” Higher Education 78 (3): 407–422.

- Clegg, S. 2016. “The Necessity and Possibility of Powerful ‘Regional’ Knowledge: Curriculum Change and Renewal.” Teaching in Higher Education 21 (4): 457–470.

- Copland, F., and A. Creese. 2015. Linguistic Ethnography: Collecting, Analysing and Presenting Data. London: Sage.

- Daniela, L., R. Strods, and D. Kalniņa. 2019. “Technology-Enhanced Learning (TEL) in Higher Education: Where Are We Now?” In Knowledge-Intensive Economies and Opportunities for Social, Organizational, and Technological Growth, edited by M. D. Lytras, L. Daniela, and A. Visvizi, 12–24. Hershey, PA, USA: IGI Global.

- Davies, M., and M. Devlin. 2007. “Interdisciplinary Higher Education and the Melbourne Model.” Proceedings of the Philosophy of Education Society of Australasia, Wellington, New Zealand, 6–9 December, 1–16. Lower Hutt, NZ: Open Polytechnic of New Zealand.

- Dawkins, H., H. Hedgeland, and S. Jordan. 2017. “Impact of Scaffolding and Question Structure on the Gender Gap.” Physical Review Physics Education Research 13 (2): 020117.

- Deslauriers, L., E. Schelew, and C. Wieman. 2011. “Improved Learning in a Large-Enrollment Physics Class.” Science 332 (6031): 862–864. doi:10.1126/science.1201783.

- Easterbrook, D., and M. Parker. 2006. “Engineering Subject Centre Mini-Project: Assessment Choice Case Study.” Higher Education Academy. Accessed April 10 2017. https://www.heacademy.ac.uk/system/files/assessment-choice-case-study.pdf.

- Filippakou, O., and T. Tapper. 2019. “The State, the Market and the Changing Governance of Higher Education in England: From the University Grants Committee to the Office for Students.” In Chap. 9 in Creating the Future? The 1960s New English Universities, edited by O. Filippakou and T. Tapper, 111–121. Cham: Springer.

- Fraser, S. P., and A. M. Bosanquet. 2006. “The Curriculum? That’s Just a Unit Outline, Isn’t it?” Studies in Higher Education 31 (3): 269–284.

- Freeman, S., S. L. Eddy, M. McDonough, M. K. Smith, N. Okoroafor, H. Jordt, and M. P. Wenderoth. 2014. “Active Learning Increases Student Performance in Science, Engineering, and Mathematics.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. National Academy of Sciences 111 (23): 8410–8415. doi:10.1073/pnas.1319030111.

- Freire, P. 1970. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. New York: Herter and Herter.

- Freire, P. 1973. Education for Critical Consciousness. New York: Continuum.

- Fung, D. 2017. A Connected Curriculum for Higher Education. London: UCL Press.

- Gee, J. 1999. An Introduction to Critical Discourse Analysis. London: Routledge.

- Gibbs, G. 2001. Analysis of Strategies for Learning and Teaching: A Research Report. Bristol: Higher Education Funding Council for England.

- Gibbs, G. 2012. Implications of ‘Dimensions of Quality’ in a Market Environment. York: Higher Education Academy.

- Gibson, V., L. Jardine-Wright, and E. Bateman. 2015. “An Investigation Into the Impact of Question Structure on the Performance of First Year Physics Undergraduate Students at the University of Cambridge.” European Journal of Physics 36 (4): 045014.

- Gurin, P., E. Dey, S. Hurtado, and G. Gurin. 2002. “Diversity and Higher Education: Theory and Impact on Educational Outcomes.” Harvard Educational Review 72 (3): 330–367. doi:10.17763/haer.72.3.01151786u134n051.

- Haak, D. C., J. HilleRisLambers, E. Pitre, and S. Freeman. 2011. “Increased Structure and Active Learning Reduce the Achievement gap in Introductory Biology.” Science 332 (6034): 1213–1216.

- Habermas, J. 1984. The Theory of Communicative Action. Vol. 1: Reason and the Rationalization of Society. Translated by T. McCarthy. Boston: Beacon.

- Hammersley, M. 2007. “Reflections on Linguistic Ethnography.” Journal of Sociolinguistics 11 (5): 689–695.

- Harland, T., A. McLean, R. Wass, E. Miller, and K. N. Sim. 2015. “An Assessment Arms Race and its Fallout: High-Stakes Grading and the Case for Slow Scholarship.” Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education 40 (4): 528–541.

- Hicks, O. 2018. “Curriculum in Higher Education: Confusion, Complexity and Currency.” HERDSA Review of Higher Education 5: 5–30.

- Hounsell, D., and C. Anderson. 2009. “Ways of Thinking and Practicing in Biology and History.” In The University and its Disciplines, edited by C. Kreber, 71–83. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Hubball, H., and M. Pearson. 2011. “Scholarly Approaches to Curriculum Evaluation: Critical Contributions for Undergraduate Degree Programme Reform in a Canadian Context.” In Reconceptualising Evaluative Practices in Higher Education: The Practice Turn, edited by M. Saunders, P. Trowler, and V. Bamber, 186–192. Maidenhead: Society for Research into Higher Education/Open University Press.

- Ippolito, K. 2007. “Promoting Intercultural Learning in a Multicultural University: Ideals and Realities.” Teaching in Higher Education 12 (5): 749–763. doi:10.1080/13562510701596356.

- Jessop, T., and A. Williams. 2009. “Equivocal Tales About Identity, Racism and the Curriculum.” Teaching in Higher Education 14 (1): 95–106. doi:10.1080/13562510802602681.

- Keesing-Styles, L., S. Nash, and R. Ayres. 2014. “Managing Curriculum Change and ‘Ontological Uncertainty’ in Tertiary Education.” Higher Education Research and Development 33 (3): 496–509.

- Knight, P. T. 2001. “Complexity and Curriculum: A Process Approach to Curriculum-Making.” Teaching in Higher Education 6 (3): 369–381. doi:10.1080/13562510120061223.

- Lattuca, L. R., and J. S. Stark. 2009. Shaping the College Curriculum: Academic Plans in Context (2nd ed.). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Liasidou, A. 2008. “Critical Discourse Analysis and Inclusive Educational Policies: The Power to Exclude.” Journal of Education Policy 23 (5): 483–500.

- Luke, A. 2002. “Beyond Science and Ideology Critique: Developments in Critical Discourse Analysis.” Annual Review of Applied Linguistics 22: 96–110.

- Mälkki, K., and S. Lindblom-Ylänne. 2012. “From Reflection to Action? Barriers and Bridges Between Higher Education Teachers’ Thoughts and Actions.” Studies in Higher Education 37 (1): 33–50.

- Matthews, K. E., and L. D. Mercer-Mapstone. 2018. “Toward Curriculum Convergence for Graduate Learning Outcomes: Academic Intentions and Student Experiences.” Studies in Higher Education 43 (4): 644–659.

- McGrath, C., and K. Bolander Laksov. 2014. “Laying Bare Educational Crosstalk: A Study of Discursive Repertoires in the Wake of Educational Reform.” International Journal of Educational Development 19 (2): 139–149.

- McKeown, A., J. Mollaney, N. Ahuja, R. Parekh, and S. Kumar. 2019. “UK Longitudinal Integrated Clerkships: Where are we now?” Education for Primary Care 30 (5): 270–274.

- Meyer, J. H. F., and R. Land. 2006. Overcoming Barriers to Student Understanding. London: Routledge.

- Mezirow, J. 1991. Transformative Dimensions of Adult Learning. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Mezirow, J. 1997. “Transformative Learning: Theory to Practice.” New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education 74: 5–12.

- Mezirow, J. 2003. “Transformative Learning as Discourse.” Journal of Transformative Education 1 (1): 58–63.

- Ofsted. 2019. “School Inspection Handbook: Draft for Consultation. No. 180041.” Crown copyright. Available at https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/801615/Schools_draft_handbook_180119_archived.pdf.

- Ofsted (Office for Standards in Education, Children's Services and Skills). 2018. “An Investigation into How to Assess the Quality of Education Through Curriculum Intent, Implementation and Impact. No. 180035.” Crown Copyright. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/curriculum-research-assessing-intent-implementation-and-impact.

- Rampton, B., K. Tusting, J. Maybin, R. Barwell, A. Creese, and V. Lytra. 2004. “UK Linguistic Ethnography: A Discussion Paper”. www.ling-ethnog.org.uk.

- Ratcliffe, M. 2019. “Why my University is Glad to be Awarding Fewer First Class Degrees.” Wonkhe Blog, November 13. https://wonkhe.com/blogs/why-my-university-is-glad-to-be-awarding-less-first-class-degrees/.

- Roberts, P. 2015. “Higher Education Curriculum Orientations and the Implications for Institutional Curriculum Change.” Teaching in Higher Education 20 (5): 542–555. doi:10.1080/13562517.2015.1036731.

- Ross, F., J. Tatam, A. L. Livingstone, O. Beacock, and N. McDuff. 2018. “‘The Great Unspoken Shame of UK Higher Education’ Addressing Inequalities of Attainment.” African Journal of Business Ethics 12 (1): 104–115.

- Saarinen, T. 2008. “Position of Text and Discourse Analysis in Higher Education Policy Research.” Studies in Higher Education 33 (6): 719–728.

- Saunders, M., P. Trowler, and V. Bamber. 2011. Reconceptualising Evaluative Practices in Higher Education: The Practice Turn. Maidenhead: Society for Research into Higher Education/Open University Press.

- Scudamore, R. 2013. “Engaging Home and International Students: A Guide for New Lecturers.” Higher Education Academy. Accessed 6 March 2020. https://www.heacademy.ac.uk/system/files/rachelscudamorereportfeb2013.pdf.

- Shay, S. 2015. “Curriculum Reform in Higher Education: A Contested Space.” Teaching in Higher Education 20 (4): 431–441.

- Shay, S., K. Wolff, and J. Clarence-Fincham. 2016. “Curriculum Reform in South Africa: More Time for What?” Critical Studies in Teaching and Learning 4 (1): 74–88.

- Short, E. C. 2002. “Knowledge and the Educative Functions of a University: Designing the Curriculum of Higher Education.” Journal of Curriculum Studies 34 (2): 139–148.

- Simsek, A. 2012. “Transformational Learning.” In Encyclopedia of the Sciences of Learning, edited by N. M. Seel, 201–211. Boston: Springer.

- Sin, C. 2014. “The Policy Object: A Different Perspective on Policy Enactment in Higher Education.” Higher Education 68 (3): 435–448.

- Singer, S. R., N. R. Nielsen, and H. A. Schweingruber. 2012. Discipline-Based Education Research: Understanding and Improving Learning in Undergraduate Science and Engineering. Washington, DC: National Academies.

- Smith, D. 2005. Institutional Ethnography. A Sociology for People. Lanham, NJ: Rowman and Littlefield.

- Sparkes, A. 1990. Curriculum Change and Physical Education: Towards a Micropolitical Understanding. Geelong: Deakin University Press.

- Stavrou, S. 2016. “Pedagogising the University: on Higher Education Policy Implementation and its Effects on Social Relations.” Journal of Education Policy 31 (6): 789–804.

- Strike, T. 2017. Higher Education Strategy and Planning: A Professional Guide. London: Taylor and Francis.

- Talbot, R. M. I., L. Doughty, A. Nasim, L. Hartley, P. Le, L. H. Kramer, H. Kornreich-Leshem, and J. Boyer. 2016. “Theoretically Framing a Complex Phenomenon: Student Success in Large Enrollment Active Learning Courses”, in 2016 Physics Education Research Conference Proceedings.” American Association of Physics Teachers, 344–347. doi:10.1119/perc.2016.pr.081.

- Tamim, R. M., R. M. Bernard, E. Borokhovski, P. C. Abrami, and R. F. Schmid. 2011. “What Forty Years of Research Says About the Impact of Technology on Learning: A Second-Order Meta-Analysis and Validation Study.” Review of Educational Research 81 (1): 4–28. doi:10.3102/0034654310393361.

- Tight, M. 2003. Researching Higher Education. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

- Transformative Learning Centre. 2016. Retrieved from Transformative Learning Centre Web site: https://www.oise.utoronto.ca/tlcca/About_The_TLC.html.

- Trowler, P. R., and A. Cooper. 2002. “Teaching and Learning Regimes: Implicit Theories and Recurrent Practices in the Enhancement of Teaching and Learning Through Educational Development Programmes.” Higher Education Research and Development 25 (4): 323–339.

- Wald, N., and T. Harland. 2017. “A Framework for Authenticity in Designing a Research-Based Curriculum.” Teaching in Higher Education 22 (7): 751–765. doi:10.1080/13562517.2017.1289509.

- Wenger, E. 1998. Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning and Identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- White, P. J., I. Larson, K. Styles, E. Yuriev, D. R. Evans, P. K. Rangachari, J. Short. et al. 2016. “Adopting an Active Learning Approach to Teaching in a Research-Intensive Higher Education Context Transformed Staff Teaching Attitudes and Behaviours.” Higher Education Research and Development 35 (3): 619–633.

- Wieman, C., and S. Gilbert. 2015. “Taking a Scientific Approach to Science Education, Part II-Changing Teaching.” Microbe 10 (5): 203–207.