ABSTRACT

Engaging with interdisciplinary learning during higher education (HE) study can provide students with skills and modes of thinking informed by multiple worldviews. Opportunities for interdisciplinary learning in the English HE system are limited; associated primarily with postgraduate study or later undergraduate stages. This paper reports on an enhancement project that sought to engage first-year students with interdisciplinary learning. Drawing on data gathered from staff interviews, student focus groups and module enrolments, we examine drivers and barriers impacting on the planned curriculum transformation. Whilst drivers emerged from many directions (e.g. professional bodies, staff advocates), these were overwhelmed by the barriers – both administrative and ideological. Student responses were mixed. Some would have liked a wider choice of truly interdisciplinary modules, but it was clear many students did not understand the rationale for the modules and felt that they needed more support to participate.

Introduction

Higher education (HE) is in a period of substantial flux, as worldwide challenges such as climate change, tense international relations and inequality become more urgent, and student pressure for change intensifies (Barber et al. Citation2013; Drayson et al. Citation2014). Interdisciplinarity is increasingly being seen as a key part of the required educational response to these so-called ‘wicked problems’ (Rittel and Weber Citation1973) which have poorly defined boundaries and contested causes or solutions. Understanding the variation in disciplinary framings of wicked problems and learning to facilitate communication across different disciplines could prepare students to work on global challenges (McCune et al. Citation2021). However, there are subjective and objective constraints to interdisciplinary teaching in HE, including structural barriers inherent in the organisation of institutions into departments and faculties, and a lack of understanding of interdisciplinarity in a world where specialism is revered (Lindvig, Lyall, and Meagher Citation2019; Yang Citation2009). The ‘siloed’ nature of academic life and the existence of ‘tribes and territories’ have been effectively discussed and analysed by Becher and Trowler (Citation2001), though their focus was not specifically on interdisciplinary working. Notably, twenty years later, little has changed in the structure of teaching units in most institutions in the UK and internationally.

Before commencing any discussion of interdisciplinary teaching, it remains crucial to define the term itself, which remains contested and is often (incorrectly) considered to be synonymous with multi-disciplinarity. To summarise a lengthy and divisive debate, interdisciplinarity involves the merging or integration of disciplinary knowledge to offer novel perspectives, unlike multi-disciplinary approaches in which each discipline contributes from its epistemological origin but remains fundamentally unchanged by its encounter with alternative views (Razzaq, Townsend, and Pisapia Citation2013). Interdisciplinary teaching is considered to assist in developing ‘Mode 2 knowledge’ (Gibbons et al. Citation1994); knowledge that is outward-looking and focused on solving real-world problems. It is evident immediately that interdisciplinarity is not an easy concept to teach or learn about, especially for academics who have spent most of their education and career immersed in a disciplinary context (Lyall et al. Citation2015). Interdisciplinarity represents a way of thinking and working which involves a move away from traditional domain-specific conceptions of knowledge, to individuals embracing a view of the world which encourages them to adopt multiple perspectives and synthesise knowledge from different disciplines (Lyall et al. Citation2015). It does not seek to undervalue the position of the discipline, rather encourages reimagining of the discipline. In doing so, it encourages students to recognise the fluidity of disciplinary boundaries and be prepared to look beyond their chosen discipline to solve problems and to think critically and creatively (Brooks Citation2017; Spelt et al. Citation2009). Interdisciplinary learning is challenging: to form connections across disciplines, students need to deploy advanced cognitive skills, thus powerful pedagogies are required (Klein Citation1990). Simply put, a well-designed and learner-centred curriculum (Spelt et al. Citation2009) is important in promoting interdisciplinary learning.

Despite increasing enthusiasm for interdisciplinary study in HE (Klein Citation1990; Lyall et al. Citation2015), research on interdisciplinarity in university education remains relatively limited (Hammons et al. Citation2020). It has been argued that encouraging students to address cross-disciplinary, thematic challenges or societal problems is important (Brooks Citation2017), encouraging students to look at broader issues, beyond their immediate discipline and in the process develop higher-level skills (Kezar Citation2013). Many benefits have been claimed for interdisciplinary programmes (including increased tolerance of ambiguity, awareness of ethical issues, and critical thinking skills) yet evidence in support of these is mixed. Likewise, research comparing the learning outcomes of students who have been following interdisciplinary courses with those on discipline-focused programmes is conflicting. Newell (Citation1992) found that students in the School of Interdisciplinary Studies performed better on certain assessments than did those students in disciplinary programmes. Yet Lattuca et al. (Citation2017) identified little difference between interdisciplinary and disciplinary majors for most learning outcomes though enjoyment was higher for students on interdisciplinary programmes.

Other research has focused on effective strategies for interdisciplinary teaching. A review by Lyall et al. (Citation2015) highlighted the lack of ‘curriculum ideologies’ to support interdisciplinary learning, which means that interdisciplinarity can be constructed in different ways. Subject-based interpretations lead to interdisciplinarity framed through a content-based lens, potentially reinforcing existing pedagogic practices and maintaining well-established disciplinary boundaries (Lyall et al. Citation2015). In-between these two positions ‘convergent’ approaches emerge, where thematic issues are addressed from disciplinary perspectives. Here the importance of multiple worldviews is strongly advocated (Brooks Citation2017). There are arguments that effective interdisciplinary practice relies on the higher-order skills (e.g. criticality, ability to synthesise multiple perspectives) that emerge through latter stages of undergraduate study (Millar Citation2016), but there have also been calls for the interdisciplinary practice to be integrated earlier, when students’ conceptions of knowledge are changing and they are potentially more receptive new ideas (Brooks Citation2017; Lyall et al. Citation2015).

Most of the research in this area has been undertaken on staff and students who work in interdisciplinary units or are enthusiasts for this approach. The literature currently has a dearth of research exploring staff and student responses to interdisciplinarity in the curriculum as encountered by non-experts whose usual mode is discipline-focused teaching (a notable exception is Lindvig, Lyall, and Meagher Citation2019), and we could find none that involved a systematic cross-institutional transformation towards embedding interdisciplinarity in the undergraduate curriculum. Our study contributes to this literature by reporting on an evaluation of the introduction of an inter-disciplinary module offered to first-year students at a large multi-discipline university in the UK and taught primarily by staff who are discipline experts with little experience in interdisciplinarity. The perceptions of academic staff and students about interdisciplinary learning were gathered as part of a large-scale study to evaluate the transformation project, offering novel insights to the ongoing debate about the role of interdisciplinary teaching and learning in HE.

Context and background to the curriculum innovation

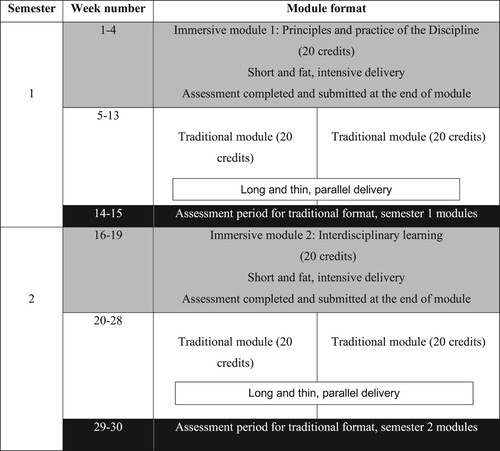

The introduction of an interdisciplinary module for all first-year students was one part of a wider curriculum innovation undertaken at a publicly funded, teaching-focused university in southern England. The curriculum framework utilised a model of extended induction to enhance student learning and reduce early withdrawals. The value of an extended first-year induction has been recognised as beneficial to all students (Bovil, Morss, and Bulley Citation2008; Tinto Citation1999), and the success of various elements of the scheme has been reported elsewhere (e.g. Turner et al. Citation2017), together with the detailed pedagogic principles of the cross-institutional project. Key elements of the scheme included a revised semester structure (which is depicted in ); each semester included one immersive (‘short fat’) modules followed by two more typical ‘long thin’ modules delivered in parallel after the conclusion of the immersive module. This revised structure of the first year was applied in each semester, followed by an assessment period.

The introduction of ‘short-fat’ modules built on practice from America, where immersive scheduling (Davies Citation2006; Muraskin Citation1998) has been identified as increasing retention (Soldner, Lee, and Duby Citation2000), developing critical thinking skills, and improving both academic performance and student-staff relationships (Richmond et al. Citation2015). Each immersive module lasted four weeks, during which time students completed module assessments. Studying only one module at key time points in the first year was felt to create opportunities for fostering strong peer connections and developing relationships with key academic staff (Turner et al. Citation2017). The modules introduced higher-level skills integral to academic success, and early assessments provided students with a sense of achievement, building their confidence in their ability to succeed at university. Immersive module one occurred at the start of semester one and focused on principles and practices of the discipline, as well as on core study skills; immersive module two took place at the start of semester two and offered all students an opportunity to experience interdisciplinary learning.

The introduction of interdisciplinarity sought to create opportunities for students from different programmes to come together to work collaboratively in a way that would broaden their focus and allow them to develop new social relationships. Schools were invited to develop interdisciplinary modules that aligned with this vision. To support this, a set of guidelines were introduced to support the development of interdisciplinary modules. These guidelines directed staff to collaborate in new ways, bringing together at least two disciplines or subject areas, focusing on big picture issues that cut across disciplines or were of relevance to wider society, and employing pedagogies such as students-as-researchers that could foster interdisciplinary learning. The module teams were also directed to develop a maximum of four learning outcomes (two knowledge-based and two skills-based outcomes). The guidelines were intentionally broad to allow local innovation to promote ownership of the curriculum innovation, an approach which echoes advice in the literature (e.g. Blackmore and Kandiko Citation2012). Staff development workshops were delivered to support the planning of the modules, though these primarily focused on inclusive assessment, active learning, and module design in general, rather than interdisciplinarity specifically. Faculty advocates supported interdisciplinarity, facilitating local interpretation of the guidelines, and discussions of interdisciplinarity to consider how this may manifest within each Faculty. The rationale for the Faculty advocate role was that support for implementation from someone with local ‘field’ knowledge and experience would help promote uptake of the pedagogic innovation (Hasanefendicet al. Citation2017). A portfolio of 52 interdisciplinary immersive modules was developed, with three of the four University faculties presenting an ‘interdisciplinary offer’ to incoming students. The Health Faculty was not included in this curriculum innovation as interdisciplinarity was identified as a theme already integrated within degree programmes and also restrictions of professional accreditation. During the first few weeks of the academic year, students selected their interdisciplinary elective.

Research aims

As part of the project evaluation, staff and student experiences of the varied interdisciplinary modules were captured, to assess the drivers and barriers to interdisciplinary teaching and learning. This study represented a departure from extant research which has focused primarily on capturing staff experiences of the process of developing and delivering interdisciplinary modules (e.g. Kezar Citation2013; Mansilla and Duraising Citation2007; Spelt et al. Citation2009) by simultaneously capturing the student experience which, as Lyall et al. (Citation2015) observed, has been overlooked in much existing research. The evaluation was designed to address the following questions:

How did academic staff interpret the agenda for interdisciplinarity?

What drivers and barriers were there to the development of inter-disciplinary modules?

What were student responses to the interdisciplinary modules?

The evaluation was informed by the work of Bamber (Citation2013) who identified the need to ‘evidence value’ from curriculum innovation activities. Bamber (Citation2013) advocates drawing on measures of hard and soft outcomes (e.g. qualitative and quantitative measures of impact) to ensure insights are gained which are cognisant of context. Given this, the evaluation was multifaceted: in-depth empirical studies were designed to be undertaken during the first implementation of each immersive module. We have already reported on the evaluation on the initial immersive module which sought to introduce new students to the practices and principles of their discipline (Turner et al. Citation2017) and examined student attainment on immersive modules (Turner, Webb, and Cotton Citation2021)). In this paper, we report the evaluation undertaken to capture student and staff perspectives of the immersive interdisciplinary module.

Methodology

Using a mixed-methods approach, the study captured qualitative data through staff interviews, student focus groups and quantitative data on module enrolments. As noted above, a portfolio of 52 immersive interdisciplinary modules was developed; from this, a purposive sample of 15 interdisciplinary modules across three faculties wereselected for the study. A member of the evaluation team, external to the curriculum innovation, made initial contact with the leaders of selected modules, to introduce the study and request their participation. All agreed to be involved and, in total, 17 staff from the 15 chosen modules participated in semi-structured interviews ().

Table 1. Overview of interview participants.

The choice of an interview method enabled the opening up of what Cousin (Citation2009: 73) refers to as a ‘third space,’ where the lecturer and researcher worked together to develop an understanding of participants’ conceptualisation of interdisciplinarity, and its role in the first-year curriculum. Interviews were conducted at the end of the interdisciplinary module, to ensure participants were able to draw on their experiences of designing and delivering teaching, marking assessments and reviewing student feedback. Interviews explored the different elements of preparing and teaching the module along with participants’ perceptions and interpretations of interdisciplinarity and the opportunities and challenges the module presented for them. The study deliberately did not impose a definition of interdisciplinarity so that we were able to explore the different understandings of participants with expertise in diverse disciplines.

During the delivery of the module, two focus groups were organised with groups of course representatives (students who have volunteered to represent their cohort in giving feedback on teaching to university staff) in a single faculty, to offer an opportunity to hear the student voice more directly and capture students’ experiences of interdisciplinary learning. Focus groups are recognised as creating opportunities for the ‘sharing and comparing’ experiences (Morgan Citation2014), and they are a common approach to capture student perspectives (Cousin Citation2009). Course representatives in the chosen Faculty were regularly brought together to provide feedback on the experiences of their peers, so they were familiar and confident with doing so. The two focus groups explored student experiences of academic and social integration over their first year, teaching, learning and assessment, and specifically interdisciplinarity. In total, 14 students participated.

Both focus groups and interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. An iterative process of analysis was employed (Silverman Citation2005); the initial round of coding was informed by common themes in the literature but was expanded as new themes emerged from the data (Silverman, Citation2005). We also examined module enrolment data, to gain insights into the extent to which students engaged with the elective component of this curriculum innovation and whether they opted to embrace the choice afforded to them. Whilst the results of this single institution research are not open to statistical generalisation, it is possible to use the data collected to theorise about the possible wider applicability of the findings to interdisciplinary teaching and learning in other contexts using ‘theoretical inference’ (Hammersley Citation2014). The paucity of literature on this topic and the importance of interdisciplinary learning in HE enhance the value of this research.

Findings and discussion

Across these data, there were very diverse responses and respondents, with some staff and students embracing the curriculum innovation and interdisciplinary working, and others preferring to retreat to more safe and familiar educational territory. Three themes emerged across the staff and student data sets, as follows:

Conceptions of interdisciplinarity (staff)

Champions and mutineers (staff)

Module choice and interdisciplinarity (staff and students).

These themes are discussed in turn below.

Conceptions of interdisciplinarity

Unsurprisingly, staff interpretation of interdisciplinarity affected the framing and development of modules. A content-focused or disciplinary interpretation prevailed, with 33 of the 52 modules dominated by disciplinary discourse (as reflected by module titles such as ‘principles of business for the twenty-first century’; ‘foundations in philosophy’), justified through practical or functional reasons. Though the guiding principles directed staff to design modules that could be taken by students from across schools and faculties, lecturers often focused on what they perceived their students needed:

What could we do that would be useful to [names discipline] students that was outside of their discipline, and might also be relevant to people in other disciplines? That was our thinking at the time. (Business ML4)

In a similar vein some of our respondents seemed unclear about what made the module interdisciplinary, with some assuming that it was about the staff involved or the students registered on it, rather than the content or pedagogic approach:

I understood that the goal for a successful [interdisciplinary] module was to develop a module that included at least one other programme of study … maybe I misinterpreted it from the beginning. (Arts ML3)

I think what makes it interdisciplinary is the subject matter, it's not who teaches it, or who it's taught to. It's the fact that it is a subject which is interdisciplinary. (Business ML4)

The module has been set up with the expectation that all [names programme] students will enrol. It links with their tutorials and is assessed by their tutors. (Science ML2)

the subject which I know the most about, which is [names subject], relies on collaboration out in the industry between any number of different people that might make up teams or that might be involved in the commissioning process. So [names profession] work with [names five other disciplines]. So a key skill, I think, for [names discipline] students, might be to understand that depending on the brief or the activity or the commission, you may find yourself needing to work beyond a prescribed discipline and embrace interdisciplinarity. To do this you need an understanding of how other people's practice may influence your own, there interdisciplinarity becomes potentially very important.

[…] students demonstrated an awareness of other practitioners operating with similar context and work collaboratively with them. (Arts ML2)

Not only do they have to reflect about what it meant to work with people outside their programme or outside their discipline, but also to reflect on what they learnt about working with others. (Arts ML3)

trying to construct modules so that one group of students in [names programme] might learn as much from students who are [names another disciplinary area].

Even those who embraced the opportunities of interdisciplinary practice reported challenges in changing entrenched attitudes, which may have further reinforced multi rather than interdisciplinary practice across the module portfolio:

There are people who stay very firmly within their disciplines or, if you like, their taught discipline, but there are other people who desperately want to break out of those disciplines. I've grown to hate silos […] I don't understand that thing of protecting one's own practice […] it can sometimes stifle an individual's creativity. For me, I think interdisciplinarity is very important, and probably doesn't happen enough. And students actually say that too. One of the ideas was I think initially to try and move away from the very strong siloing of the English system which is not necessarily in step with a lot of the other … much of the rest of the world where there's a lot more flexibility.

if they're talking to their friends, and their friends have done something which is totally different from what they've done, they'll be thinking, well was that more burdensome? Did they get higher marks? Did they learn more? Was it more enjoyable? You want to have some commonality of student experience, or at least be able to tell the students, if you do this, then this is what you'll get out of it. (Business ML3)

I am completely interdisciplinary [but] I really found it very, very hard to get any cooperation from colleagues. And I didn’t get the impression that any resource is associated with this at all! (Arts ML4)

Overall, conceptions of interdisciplinarity were complex, and shaped by a range of factors, that extended beyond understandings of interdisciplinary practice, to more practical or local concerns, that collectively determined the extent to which the vision of these modules was realised.

| 2. | Champions and mutineers | ||||

The positive contributions interdisciplinarity can make to address global issues and enhancing graduate employability represent powerful drivers that can challenge traditional disciplinary practices (Borrego and Newswander Citation2010; Lattuca, Voight, and Faith Citation2004; Spelt et al. Citation2009). However, there are hints in the literature that the position of champion of interdisciplinary teaching and learning is not always an easy one:

Individuals who develop interdisciplinary teaching provision were seen as pioneering champions often working against the status quo. (Lindvig, Lyall, and Meagher Citation2019, 355)

I really like the concept; I think it's a good idea. […] I like the idea of trying to do something slightly different, interdisciplinary, get the students involved as researchers. (Business ML1)

I think if you throw it open, like with anything in a large organisation, then it's hard to just see what will actually happen […] a lot of people [were] just saying, we’re just going to stick to our subject-specific stuff. (Science ML1)

I was sceptical to start off with, because I felt that it had been introduced with perhaps insufficient institutional knowledge. But having had to implement it, I have really come round to it, and I really enjoy it, and I think it’s quite an interesting experience for the students. (Business ML2)

I like having flexibility, but I like to know what the framework, within which I can exercise the flexibility, is supposed to be […] I like to know what the objectives are, what are we trying to achieve […] what I don't like is not being clear about what the limits of our flexibility are. (Business ML3)

Some academics have concerns that we’re losing these 20 credits from the curriculum and they’re necessary for students in this programme […] so actually it does need to be more discipline focused than we originally wanted […] and perhaps limited the interdisciplinarity of the module. (Business ML5)

For some staff, organisational complexity became a focal point of their frustrations, as they viewed the interdisciplinary module as difficult to deliver and irrelevant to students’ core subject:

[…] if you're just doing a little pocket four-week module in the middle of your [subject] degree which is also about [subject] but not related to anything. I mean, why not just study [subject] and be done with it. (Arts ML1)

| 3. | Module choice and interdisciplinarity | ||||

One of the reasons it has been argued that interdisciplinary teaching is not more widespread at the undergraduate level relates to the strong ‘framing’ (Bernstein Citation2000) or constraints on the curriculum at this level (Lindvig, Lyall, and Meagher Citation2019). Lindvig et al. (2019) argue that the strong external framing of undergraduate degrees in many European universities limits the extent of curricular innovation towards interdisciplinarity. In our study, arguably, the external framing itself had been challenged by the cross-institutional innovation – this should have made it easier for staff to colonise the liminal spaces between disciplines (the ‘interstices’ as Lindvig, Lyall, and Meagher (Citation2019) described them). Nonetheless, certain elements of the undergraduate education structure proved remarkably resistant to change – and it became evident that both students and staff could act as brakes on innovation by defaulting to their habitual modes of working. So for example, module choices (in theory a key part of the curriculum innovation) were in practice highly variable. For some programmes, student choice was seemingly inconceivable:

We had all of our cohort doing the one module. So they didn’t get the choice to go and do elective modules elsewhere. (Science ML3)

I like the idea of flexibility of it. That students can choose what they want to do rather than have a module imposed upon them. (Arts ML2)

It needs to be signposted much more for students […] it needs to be signposted much more for the University generally to say we are moving in an interdisciplinary direction and we expect you as students to contextualise your knowledge within different disciplines and get exposure to them. (Business ML2)

There probably was some sort of document online about it but no, I didn’t see it, unfortunately. (Student FG1)

Yes, so we got like a set of ten things, you got an email with like some slides on it and they had like ten different topics and it told you a little bit about what each one was and then you just had to pick one. (Student FG1)

I like went out of my own way, just looked at some books, and that, and that’s how I made my decision. (Student FG1)

Another impact on student choice was the extent to which they were concerned by having to form new social groupings with staff and students who were unfamiliar to them:

I had to go socialise with other people […] the friend making thing […] becomes more difficult as the stage goes on. (Student FG1)

I didn’t recognise any of the lecturers […] I was just there like, I can't take any of this in, sort of thing. So it was so different to what I was used to. (Student FG2)

[…] because we didn’t have any like ice breakers, everyone just like shows up, goes to a lecture goes home. Unless you're in the seminar and you kind of become friends like that way. I know we did a field trip but that was in the middle of the year when everyone’s already made their friends. So my course, I don’t know if it's just my year, but no one’s really friends on it. I see them but they just don’t talk because there's no like opportunity to. (Student FG2)

A final issue with choice was that many students left it until the last minute and, to our surprise, more than 10% of students did not engage with the module selection process at all, so were allocated to a module centrally. The relatively limited engagement with interdisciplinarity was also evident through module enrolment data with only 2.07% of students who could select an elective choosing one outside their Faculty. The majority selected modules directly related to their chosen area of study; for example, students on environmentally-focused programmes selected electives that addressed themes such as geohazards, sustainability or climate change. Students opted for the familiar; they chose course titles that resonated or options that minimised disruption of established peer networks. Therefore, how student choice is framed is crucial. Arguably, rather than creating an additional administrative burden in terms of shifting resources, the focus should be on within-faculty choice, and interdisciplinarity positioned within rather than outside of this institutional structure.

Conclusion and recommendations

This research captured the responses of academic staff to the introduction of interdisciplinary learning into the first-year curriculum and the experiences of students studying these modules. Integrating interdisciplinary learning into the first-year curriculum was a significant departure from previous practice in this institution (as in many UK universities). Our findings indicate that, with a few exceptions, staff conceptions of interdisciplinarity were often limited, aligning more with multi-disciplinarity perspectives rather than interdisciplinarity. This in itself is an important outcome, a step in the right direction, but it also highlights the support that needs to be put in place, in terms of staff and module development, and structural change that may be required, to allow staff to engage with interdisciplinary. The discipline and programme focus represented the priority for many academics, and this became a barrier to developing interdisciplinary modules. Staff who recognised the opportunities presented by the early integration of interdisciplinarity, focused on skills such as collaboration, problem solving and communication, associated with interdisciplinary working to introduce and engage students with this agenda. Whilst drivers emerged from many directions (including some professional bodies, staff enthusiasts and student interest), these were generally overwhelmed by the barriers – both administrative and ideological – to delivering a truly interdisciplinary experience. Staff resistance was a key barrier: sometimes with good reason, staff were very protective about their discipline and students. However, administrative barriers (both financial and practical) were also very much in evidence despite the top-down nature of the curriculum innovation.

Student responses were mixed: Some would have liked a wider choice of truly interdisciplinary modules, but it is equally evident that many students did not understand the rationale for the modules, and felt that they needed more information and support to participate in them enthusiastically. Student disengagement with opportunities for interdisciplinarity emerged as a significant, but unanticipated, finding of this study.

In considering future research, it is useful to revisit the scope of this work. We did not set out to critically examine interdisciplinarity and the role it can play in the first-year curriculum, rather we sought to explore how staff, many of whom had limited prior experience of interdisciplinarity, responded to and engaged with an agenda to integrate into the first-year curriculum. In doing this work we have highlighted the parameters on which future curriculum innovation work in this area can build. Following on from this, future research might focus specifically on pedagogic practices that promote interdisciplinary working with first-year students, as positive reactions were documented by lecturers and students in response to the use of group work and collaboration around thematic issues. Examining how to introduce and frame interdisciplinarity when disciplinary identities are still emerging would support on-going pedagogic innovation in this area for the lower levels of undergraduate study. Focusing further research on students’ experiences of interdisciplinarity would also be beneficial as this remains a gap in the extant literature. As the research presented here indicates, despite the multitude of advantages of interdisciplinary learning laid out in the literature, realising these in practice is rather more problematic.

Key recommendations for institutions planning to embed interdisciplinary modules into the curriculum (especially in the first year) are as follows:

Engage academics through targeted staff development to get a shared understanding of interdisciplinarity – and how it diverges from multi-disciplinary approaches – paying attention to current debates and practices in interdisciplinary learning and allow time for reflection and discussion. This could potentially mitigate staff resistance to interdisciplinarity, or a belief that it was a threat to their discipline.

Ensure resource follows students to encourage staff to offer modules which cut across traditional disciplinary boundaries, and minimise the burden of administration that comes with such modules.

Set up a clear process for student information and choice that includes recognition of the need to consider the link between an interdisciplinary module and their programme of study and future career.

In conclusion, this research reinforces the fact that both teaching and learning in interdisciplinary ways are complex skills that make significant demands on both parties. Despite the strong institutional support for this innovation, the barriers of administrative framing and staff and student habits proved challenging to overcome. As the value of interdisciplinary boundary-crossing is evidenced yet more strongly through the COVID-19 pandemic, the need to challenge the status quo in higher education grows ever more urgent.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Akkerman, S. F., and A. Bakker. 2011. “Boundary Crossing and Boundary Objects.” Review of Education Research 82 (2): 132–169.

- Bamber, V. 2013. “A Desideratum of Evidencing Value.” In Evidencing the Value of Educational Development, edited by V. Bamber, 39–46. London: SEDA.

- Barber, M., K. Donnelly, S. Rizvi, and L. Summers. 2013. An Avalanche is Coming. Higher Education and the Revolution Ahead. London: Institute for Public Policy Research.

- Barnett, R., G. Parry, and K. Coate. 2001. “Conceptualising Curriculum Change.” Teaching in Higher Education 6 (4): 435–449.

- Becher, T., and P. Trowler. 2001. Academic Tribes and Territories. Intellectual Enquiry and the Culture of the Disciplines. 2nd ed. Buckingham: SRHE/Open University Press.

- Bernstein, B. 2000. Pedagogy, Symbolic Control, and Identity: Theory, Research, Critique. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Billing, D. 1996. “Review of a Modular Implementation in a University.” Higher Education Quarterly 50: 1–21.

- Blackmore, P., and C. Kandiko. 2012. Strategic Curriculum Change. Global Trends in Universities. London: Routledge.

- Borrego, M., and W. H. Newswander. 2010. “Definitions of Interdisciplinarity Research: Towards Graduate-Level Interdisciplinary Learning Outcomes.” The Review of Higher Education 34 (1): 61–84.

- Bourner, J., M. Hughes, and T. Bourner. 2001. “First-Year Undergraduates Experience of Group Project Work.” Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education 26 (1): 19–39.

- Bovil, C., K. Morss, and C. Bulley. 2008. Quality Enhancement Themes: The First Year Experience: Curriculum Design for the First Year. Glasgow: Quality Assurance Agency Scotland.

- Brooks, C. F. 2017. “Disciplinary Convergence and Interdisciplinary Curricula for Students in an Information Society.” Innovations in Education and Teaching International 54 (3): 206–213.

- Cousin, G. 2009. Researching Learning in Higher Education: an Introduction to Contemporary Methods and Approaches. London: Routledge.

- Davies, W. M. 2006. “Intensive Teaching Formats: A Review.” Issues in Educational Research 16 (1): 1–20.

- Drayson, R., E. Bone, J. Agombar, and S. Kemp. 2014. Student Attitudes Towards and Skills for Sustainable Development. York: NUS/HEA.

- Gibbons, M., C. Limoges, H. Nowotny, S. Schwartzman, P. Scott, and M. Trow. 1994. The New Production of Knowledge. The Dynamics of Science and Research in Contemporary Societies. London: Sage.

- Hacker, A., and C. Dreifus. 2010. Higher Education? How Colleges are Wasting our Money and Failing Our Kids – and What We Can Do About it? New York, NY: St Martins Griffin.

- Hammersley, M. 2014. The Limits of Social Science: Causal Explanation and Value Relevance. Sage: London.

- Hammons, A. J., B. Fiese, B. Koester, G. L. Garcia, L. Parker, and D. Teegarden. 2020. “Increasing Undergraduate Interdisciplinary Exposure Through an Interdisciplinary Web-Based Video Series.” Innovations in Education and Teaching International 57 (3): 317–327.

- Hasanefendic, S., J. M. Birkholz, H. Horta, and P. Van Der Sijde. 2017. “Individuals in Action: Bringing about Innovation in Higher Education.” European Journal of Higher Education 7 (2): 101–119.

- IchemE. 2008. “Accreditation of Chemical Engineering Degrees – a Guide for University Departments and Assessors, Based on Learning Outcomes.” Master & Bachelor Level Degree Programmes. Institute of Chemical Engineers, Rugby.

- Jenkins, A., and L. Walker. 1994. “Introduction.” In Developing Student Capability Through Modular Courses, edited by A. Jenkins, and L. Walker, 19–23. London: Kogan.

- Kezar, A. 2013. “Understanding Sensemaking/Sensegiving in Transformational Change Processes from the Bottom up.” Higher Education 65: 761–780.

- Klein, J. T. 1990. Interdisciplinarity: History, Theory and Practice. Detroit: Wayne State University Press.

- Klein, J. T., and W. H. Newell. 1996. “Advancing Interdisciplinary Studies.” In Handbook of the Undergraduate Curriculum, edited by J. G. Gagg and J. L. Ratcliff, 3–22. San Fransisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Lattuca, L. R., D. Knight, T. A. Seifert, R. D. Reason, and Q. Liu. 2017. “Examining the Impact of Interdisciplinary Programs on Student Learning.” Innovative Higher Education 42: 337–353.

- Lattuca, L. R., L. J. Voight, and K. Q. Faith. 2004. “Does Interdisciplinarity Promote Learning? Theoretical Support and Researchable Questions.” Review of Higher Education 28 (1): 23–48.

- Lindvig, K., C. Lyall, and L. R. Meagher. 2019. “Creating Interdisciplinary Education Within Monodisciplinary Structures: The Art of Managing Interstitiality.” Studies in Higher Education 44 (2): 347–360.

- Lyall, C., L. J. Meagher, Bandola Gill, and A. Kettle. 2015. Interdisciplinary Provision in Higher Education: Current and Future Challenges. York: Higher Education Academy.

- Mackinnon, P. J., D. Hine, and R. T. Barnard. 2013. “Interdisciplinary Science Research and Education.” Higher Education Research and Development 32 (3): 407–419.

- Mansilla, A. B., and E. D. Duraising. 2007. “Targeted Assessment of Students’ Interdisciplinarity Work: An Empirically Grounded Framework.” The Journal of Higher Education 78 (2): 215–237.

- McCune, V., R. Tauritz, S. Boyd, A. Cross, P. Higgins, and J. Scoles. 2021. “Teaching Wicked Problems in Higher Education: Ways of Thinking and Practising.” Teaching in Higher Education. doi:10.1080/13562517.2021.1911986.

- Millar, V. 2016. “Interdisciplinary Curriculum Reforms in the Changing University.” Teaching in Higher Education 21 (4): 471–483.

- Morgan, D. L. 2014. “Focus Groups and Social Interaction.” In The Sage Handbook of Interview Research: the Complexity of Craft, edited by J. F. Gubrium, J. A. Holstein, A. B. Marvasti, and K. D. McKinney, 161–176. Sage: London.

- Muraskin, L. D. 1998. A Structured Freshman Year for At-Risk Students. Washtoning, DC: US Department of Education.

- Newell, W. H. 1992. “Academic Disciplines and Undergraduate Interdisciplinary Education: Lessons from the School of Interdisciplinary Studies at Miami University, Ohio.” European Journal of Education 27: 211–221.

- Plastow, N., G. Spiliotopoulou, and S. Prior. 2010. “Group Assessment at First Year and Final Year Degree Level: A Comparative Evaluation.” Innovations in Education and Teaching International 47 (4): 393–403.

- Razzaq, J., T. Townsend, and J. Pisapia. 2013. “Towards an Understanding of Interdisciplinarity: The Case of a British University.” Issues in Interdisciplinary Studies 31: 149–173.

- Richmond, A. S., B. C. Murphy, L. S. Curl, and K. A. Broussard. 2015. “The Effect of Immersion Scheduling on Academic Performance and Students’ Ratings of Instructors.” Teaching of Psychology 42 (1): 26–33.

- Rittel, H. W. J., and M. M. Weber. 1973. Policy Science 4: 155–169.

- Silverman, D. 2005. Interpreting Qualitative Data. Sage: London.

- Soldner, L., Y. Lee, and P. Duby. 2000. “Welcome to the Block: Development Freshman Learning Communities that Work.” Journal of College Student Retention: Research, Theory and Practice 1 (2): 115–129.

- Spelt, E. J. H., H. J. A. Biemans, H. Tobi, P. A. Luning, and M. Mulder. 2009. “Teaching and Learning in Interdisciplinary Higher Education.” Educational Psychology Review 21: 365–378.

- Tinto, V. 1999. “Taking Retention Seriously: Rethinking the First Year of College.” NACADA Journal 19 (2): 5–9.

- Trowler, P. 1997. “Beyond the Robbins Trap: Reconceptualising Academic Responses to Change in Higher Education (or Quiet Flows the Don?).” Studies in Higher Education 22 (3): 301–318.

- Turner, R., D. Morrison, D. Cotton, S. Child, S. Stevens, and P. Kneale. 2017. “Easing the Transition of First Year Undergraduates Through an Immersive Induction Module.” Teaching in Higher Education 22 (7): 805–821.

- Turner, R., O. J. Webb, and D. R. E. Cotton. 2021. “Introducing Immersive Scheduling in a UK University: Potential Implications for Student Attainment.” Journal of Further and Higher Education 45 (10): 1371–1384. doi:10.1080/0309877X.2021.1873252.

- Wingate, U. 2007. “A Framework for Transition: Supporting ‘Learning to Learn’ in Higher Education.” Higher Education Quarterly 61 (3): 391–405.

- Woods, C. 2007. “Researching and Developing Interdisciplinary Teaching: Towards a Conceptual Framework for Classroom Communication.” Higher Education 54 (6): 853–866.

- Yang, M. 2009. “Making Interdisciplinary Subjects Relevant to Students: An Interdisciplinary Approach.” Teaching in Higher Education 14 (6): 597–606.