ABSTRACT

The shift towards an ecological university may be the key to achieving greater levels of social justice within higher education. This assumes that we could change the root metaphor of higher education – away from the current industrial model that is infused with neoliberal ideology and towards a more sustainable ecological model. This change involves five key moves that require us to: construct an institutional natural history to understand the network of interactions within the university; to explore the nature of the dominant narratives and move away from a narrative monoculture; to value post-abyssal thinking that includes cultural knowledge as well as academic knowledge; to move away from dependence on heroic leaders towards ecological leadership, and to consider how we can develop sustainable pedagogies that can withstand disturbances to the ecosystem. This paper acknowledges that coordination of these moves presents a considerable challenge to university managers.

Introduction

The literature describing Higher Education is full of negative imagery conveying a perception of a broken system. Expressions such as ‘the university in ruins’, ‘the toxic university’ or ‘the hollow university’ describe institutions that appear trapped within a sedimented field imaginary in which the professional values of collegiality and innovation have given way to a neoliberal emphasis on ‘anti-ecological’ values such as competition and productivity, where qualifications take priority over learning (Morini Citation2020). This may be viewed as part of the wider neoliberal ‘disimagination machine’ that is seen by Giroux (Citation2013, 264) to result in:

education policies that substitute critical thinking and critical pedagogy for paralyzing pedagogies of memorization and rote learning tied to high stakes testing in the service of creating a neoliberal, dumbed down work force.

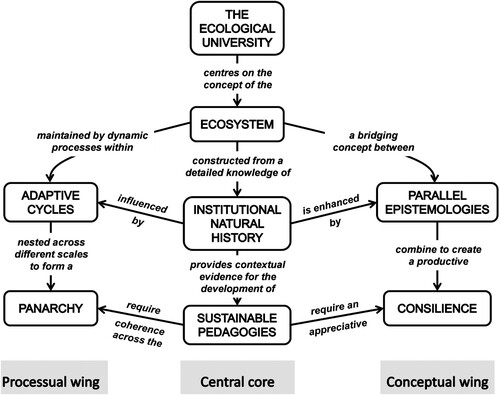

Figure 1. A concept map of the central ideas of the ecological university (modified from Kinchin Citation2022a).

From this theoretical underpinning we can start to work out what needs to be done to move universities away from the nineteenth Century industrial model of education, with its root metaphors (i.e. taken-for-granted cultural assumptions encoded in the language that allows for the conceptualization of certain relationships while hiding others) of progress, anthropocentrism and subjectively centred individualism (Bowers Citation2002), towards an ecological model with an emphasis is on connectivity, care and sustainability. The complex changes involved in the application of ecological thinking are summarized here as ‘Five Moves’ that represent the practicalities of operationalizing the ecological university model. I have used the term ‘moves’ rather than ‘steps’, as the latter suggests a linear sequence of activities that would be inappropriate in an ecological system in which transitions tend to be non-linear, or rhizomatic (e.g. Gravett Citation2021). There is also a need to avoid the reductionist socialization of ‘ecology’ that exists within the consumerist logic of neoliberal discourses where it is confined in scope to consider the eco-management way of thinking predicated on industrial root metaphors linked to consumerism (Bowers Citation2001), and maintains an anthropocentric view of the environment as a resource to be exploited. Clarity about the scope of ecological thinking is offered by Code (Citation2006, 5):

Ecological thinking is not simply thinking about ecology or about ‘the environment’, although these figure as catalysts among its issues. It is a revisioned mode of engagement with knowledge, subjectivity, politics, ethics, science, citizenship, and agency that pervades and reconfigures theory and practice. It does not reduce to a set of rules or methods; it may play out differently from location to location; but it is sufficiently coherent to be interpreted and enacted across widely diverse situations.

Construct an institutional natural history

Explore narrative ecologies

Value post-abyssal thinking

Develop ecological leadership

Develop sustainable pedagogies

These are not trivial moves, and each requires commitment on the part of stakeholders to be achieved in a way that will accrue potential benefits. Appreciation of these moves also requires an understanding of several important ideas that contribute to a transformed education sector. This will help to create a more positive narrative that is needed to empower these groups to ‘mend’ their universities (Kinchin Citation2023). The concept of the ecosystem is central to the ecological university, and it is critical to develop a deep understanding of this idea that will move thinking beyond the managerial search for simplicity and linear thinking, to embrace the value of complexity and rhizomatic thinking. Alongside these ideas is the philosophy of becoming – the acceptance that nothing is static and that an antifragile stance, where active change and uncertainty are signs of a healthy system that exhibits educational diversity (Fortunato Citation2017), is one that is achievable in practice.

Ecology and social justice

Underpinning much research into Higher Education is an explicit commitment to a more socially just education system (e.g. Shay and Peseta Citation2016; Aktaș Citation2021) – a value that underpins each of the five moves listed above. Such social justice requires a parity of participation and full epistemic access in which students can access powerful knowledge in partnership with other ‘knowers’, inside and outside the academy (Clegg Citation2016; Luckett and Shay Citation2017). This parity of participation is something that universities in the UK still struggle with. Institutions refer to this obliquely with reference to ‘attainment gaps’ exhibited by particular groups, a situation that is highlighted by Ross et al. (Citation2018) as the ‘shame of UK Higher Education’. Various scholars have drawn links between the concept of social justice and sustainability and the ways in which these combine to address inequalities in educational systems (e.g. Ketschau Citation2015; Rodrigues and Lowan-Trudeau Citation2021). Injustices in the system can be conceptualized as socio-ecological problems (Berkovich Citation2014). In their analysis, Furman and Gruenewald (Citation2004) have attempted to integrate the social justice discourse with the ecological narrative to develop an expanded concept of ‘socioecological justice’. In so doing they acknowledge the interdependence of social and ecological systems. Increasing social justice is therefore embedded within the task of moving towards an ecological university. At the moment, the coming of the ecological university (sensu Barnett Citation2011a) still feels like a distant aspiration whose adoption is, paradoxically, blocked by the neoliberal responses to various disturbances to the university ecosystem that would have been better accommodated if we had already made the necessary moves. The moves towards an ecological university may be informed by reflection on the six questions raised by Misiaszek and Rodrigues (Citation2023) to help unpack the teaching of justice-based environmental sustainability (JBES). These are questions that intersect with the five moves that are outlined below.

Construct an institutional natural history

One route towards a greater understanding of the nuances of the local teaching ecosystem is through in-house SoTL enquiry. Because of the tendency for SoTL [Scholarship of Teaching and Learning] enquiry to be small scale and contextually specific, much of the work of this sort that is undertaken in universities is unfunded and therefore seen as being of low prestige. However, the inclination to engage in unfunded research (Edwards Citation2022) may be a way of escaping the hegemonic, epistemological monoculture of research (Bennett Citation2015), in which the ‘politics of method’ (Wooten Citation2018) has resulted in a situation in which ‘most studies look the same’, and that being forced into a narrow repertoire of methodologies can ‘prevent us from doing something different’ (Guttorm, Hohti, and Paakkari Citation2015, 16,17). Currently, this type of research is suppressed by the dominant discourses of the Research Excellence Framework (REF) in the UK that requires research to be generalizable, international and large scale for it to be recognized as valuable – or worse, prestigious. The ranking of research for the REF helps to perpetuate social inequalities within academia by providing a universalizing framework of legitimacy for certain practices while devaluing others, while the underpinning symbolism of ‘research excellence’ generates a myth that can be used and rearticulated in non-academic (e.g. policy) contexts (Maesse Citation2017). The increased diversity of voices that can be uncovered through educational ethnography increases the range of ideas and assets that can be co-opted when subjected to environmental disturbances so that the ecological resilience (sensu Holling Citation1996) of the system is enhanced. In addition, environments that are described by a multiplicity of voices will be more inclusive for students and educators alike (Botticello Citation2020). SoTL activities may represent ‘small activisms’ as described by Grant (Citation2021, 541), and offer a:

resource for recouping an academic life worth living, one where we critically respond to (among other things) new norms of university teaching as they are forced upon us through policy. In so doing, we undermine the monolithic, depredating and fear-engendering forces of risk aversion, ‘excellence’-seeking and standardisation that our universities invoke more and more in everyday academic life.

Explore narrative ecologies

Restricting access to SoTL to those who are already ‘expert’ researchers or ‘leaders in teaching and learning’ (as suggested by Canning and Masika Citation2022) would play into the narrative monoculture of the neoliberal university. These monocultures push the grand narratives of the day which represent the interests of those in power and silence counter-narratives (Gabriel Citation2016). Counter-narratives are attempts by those who are marginalized or disempowered to find a voice and contest the hegemony of the grand narratives. Engagement with SoTL may offer the refuge of a ‘narrative garden’ (sensu Gabriel Citation2016), a safe space where alternative views and innovative practices may be nurtured and cultured. To deny these spaces, is to deny colleagues the potential to develop and to become something different. Gabriel (Citation2016) considers the co-constructive energy of the counter-narrative to be essential for the health of the grand narratives as part of a dynamic ‘narrative ecology’ that takes us beyond simplistic dualities. Therefore, any restriction of SoTL would reduce the diversity of narratives and weaken the narrative ecology as a whole.

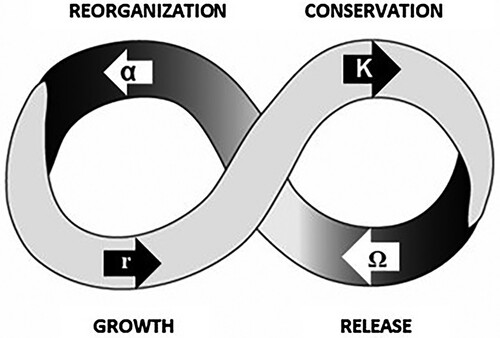

The nature of the narrative ecology will be influenced by the state of the university ecosystem. That is, which phase of the adaptive cycle best describes the current context (). The adaptive cycle (Holling Citation2001) summarizes the stabilizing and de-stabilizing factors that influence the ecosystem as a repeating sequence of four phases: release (Ω), reorganization (α), growth (r), and conservation (K). The release phase is when the functions of a system collapse and capital and connections bound up in a system are made available. This will have been seen in universities at the outset of the Covid-19 pandemic, when established processes were suddenly turned upside down as university campuses closed and teaching was forced online. The reorganization phase is when the available capital (human, social, cultural, environmental, financial, etc.) and connections are exposed to new innovations and are reconfigured. During Covid, our teaching was reconfigured as we all got to grips with teaching on Zoom. The growth phase is a period when new working patterns are established. Finally, the conservation phase is a relatively stable period where new ways of working become the accepted norm. The trajectory of the adaptive cycle alternates between the slower fore loop (r and K), characterized by ‘long periods of accumulation and transformation of resources (from growth to conservation …)’ and the faster back loop (Ω and α), characterized by ‘shorter periods that create opportunities for innovation (from release to reorganisation …)’ (Holling Citation2001, 394)

Figure 2. The adaptive cycle (after Holling Citation2001).

In institutions with a rich narrative ecology, there will be more resources and a richer diversity of assets to draw upon when a disturbance causes the ecosystem to enter the release phase. The release phase will challenge this diversity and some ways of working may have to be relinquished (temporarily or permanently). For institutions that have developed a narrative monoculture during the conservation phase, there will be a much narrower repertoire of assets to draw upon. Where the monoculture is not suited to the ‘new’ environment, there is a danger of extinction. A ‘SoTL-rich’ environment is therefore, likely to exhibit greater diversity of ideas and ownership of experiences, and so a greater level of ecological resilience in the face of major environmental disturbance. SoTL activities are not just about describing ‘where we are and who we are’, but ‘where we might go, and what we might become’: preparation for the next release phase in the adaptive cycle even though we have no idea what the trigger might be.

A pre-requisite to address the first and second questions posed by Misiaszek and Rodrigues (Citation2023) (i.e. defining ‘sustainability’ and ‘development’) is the construction of an understanding of the nature of a university’s narrative ecology. These will be informed by the root metaphors that are used to form institutional education strategies (Kinchin Citation2022b), as the terms will have different meanings under different root metaphors and will be aligned to adjunct concepts in different ways. For example, in a ‘consumer-driven’ university, ‘sustainability’ is often paired with ‘growth’, while in an ecological university it might be considered in the context of ‘sustainable de-growth’ (e.g. Prádanos Citation2015). Appreciating the local policy context is therefore essential to establish meaning and to consider terms such as sustainability and development in critical ways (e.g. Misiaszek Citation2020).

Value post-abyssal thinking

The key to understanding many of the so-called ‘wicked problems’ that challenge society may be the development of a level of epistemological flexibility. As suggested by Andreotti, Ahenakew, and Cooper (Citation2011, 46):

becoming (consciously) bi- or multi-epistemic or operational in two or more ways of knowing, involves understanding different social and historical dynamic processes of knowledge construction, their limitations and the social-historical relations of power that permeate knowledge production. It also involves being able to reference, combine and apply the appropriate frame of reference to an appropriate context.

The idea of ‘post-abyssal thinking’ draws on the work of Boaventura de Sousa Santos (Citation2014) who has considered the potential inhibitory effects of aligning ourselves to a single way of thinking – typically dominated by an epistemological perspective that is associated with ‘Western’ or ‘scientific’ reasoning. This obscures (or ignores) other types of cultural or practical knowledge that exist within communities. This dominant view has been described by Paraskeva (Citation2022) as the modern Western Euro-centric epistemological matrix. Santos described the gap between the two perspectives as an abyss, where this side of the abyss is represented by the comforting solidity of science, and the other side of the abyss (portrayed variously as anecdotal or Indigenous knowledges) is largely ignored. This becomes ‘post-abyssal’ when the two sides of the abyss are brought together, in consilience (Wilson Citation1998). Within the neoliberal university little attention is paid to the other side of the abyss as such ‘non-academic’ knowledge is often difficult to portray using the reductionist metrics that the system requires for evaluation and audit. Therefore, for many institutions, the ‘inclusion agenda’ currently only includes elements from this side of the abyss.

And so, to consider question 5 proposed by Misiaszek and Rodrigues (Citation2023) regarding ‘epistemological groundings’, I acknowledge here that the suggestion of ‘epistemological pluralism’ will cause a nervous ‘shudder’ (sensu Charteris Citation2014) among many academics. However, this may be required to initiate the necessary ‘punctuated change’ towards an ecological perspective, as the typical trajectory of change in universities (described as ‘disjointed incrementalism’ by Parsons and Fidler Citation2005) is not enough to overcome the inertia of ‘dynamic conservation’ (Ansell, Boin, and Farjoun Citation2015) that typically works to maintain the status quo.

Develop ecological leadership

The development of epistemological flexibility may support colleagues to develop their own context-specific ‘leadership literacy’ by transforming perspectives on leadership and acting as a bridge between different academic tribes in the university. To reach this goal, Davis (Citation2010:, 44) suggests:

To be leadership literate for the knowledge era, leaders need to develop a deep understanding of themselves and their world and acknowledge that they are part of their world. This goes deeper than simply learning a particular set of functional skills or being able to demonstrate a series of competencies by rote.

If we consider leadership in ecological terms, then we need to view it as a relational phenomenon that exists in the connections between team members. The de-centring of leadership as a result of ecological thinking paradoxically pushes the concept of leadership centre stage as a community endeavour rather than an activity done by heroic leaders who are external to the teaching community. This ecological perspective presents an additional step from ‘command-and-control leadership’ and beyond ‘networked leadership’. Kinder et al. (Citation2021) describe how the move towards ecological leadership requires ideational leaders to build an overall collective consciousness by creating and encouraging relationships. Only in systems where there is a high degree of trust and empathy will this succeed, and this requires leaders to be embedded within the teaching teams rather than operating from remote corners of the campus.

Develop sustainable pedagogies

The pedagogy (i.e. the values, beliefs and theories that underpin and direct our teaching practice) will need to shift away from the transmissive paradigm that still dominates much of higher education, moving towards more transformative learning orientation within a relational pedagogy (Kinchin and Gravett Citation2022). The key elements of this focus on ecology and sustainability have been helpfully synthesized by Burns (Citation2015, 272):

By drawing on the wisdom of ecological principles and Indigenous worldviews, sustainability teaching and learning can be designed in a way that is focused on learners’ whole selves, empowering learners to become citizens who know how to understand and address problems systemically and intellectually; know how to critically question dominant norms and to listen to a variety of less heard perspectives, engaging their emotions in this process; know how to work with others collaboratively, relationally, and physically in an active process of problem solving; and who know themselves and their places spiritually, who understand their interconnectedness with all life, and who can engage with the living world in a balanced and sustainable way.

There is also a need to reappraise some of the taken-for-granted mantras that dominate discourses in teaching at university (Kinchin and Gravett Citation2022). For example, Tikly (Citation2011) describes how a focus on learning outcomes points to the deep seated and subliminal nature of neoliberal management that binds itself to contradictory discourses, creating a roadblock to social justice. While Morini (Citation2020, 56) sees our current focus on outcomes as being ‘anti-ecological’ by clogging ecologies and decontextualizing the ecological systems that students inhabit, such that an ‘outcome orientation disables us from dwelling on the present and the past, disengaging us from broader communities and excising the imperialist history of Western knowledge systems, as we rush toward the next outcome’.

Conclusion

Underpinning the moves described above is the fundamental assumption that:

The use of ecology as a root metaphor … foregrounds the relational and interdependent nature of our existence as cultural and biological beings … [it] foregrounds relationships, continuities, non-linear patterns of change, and a basic design principle of Nature that favors diversity (Bowers Citation2002, 29).

Rather than concentrating exclusively on the potential benefits of a ‘feasible utopia’, we should perhaps be aware of the impact of potential dystopias (Barnett Citation2011b). Moving forward from our current position where we have an education system perceived to be one ‘that privileges memorization over critical thought and where students continue to play a passive role’, Pinto et al. (Citation2021, 102832) explain how a ‘speculative design process’ can help to highlight future risks and threats, such as warning us:

about the dangers of new technologies and raising awareness of future users about associated risks … of an education that prioritizes the use of screens, that substitute professors for holograms and where the concept of a classroom no longer exists, replaced for individual and solitary learning.

Within the ecological university the navigation of crises will follow the adaptive cycle to arrive at a new plateau. A crisis is recognized as, ‘a major source of discontinuity, [that] would prompt the production of alternative representations of the future, drawing on this discontinuity as a source of creativity that frees up the ability to imagine significantly alternative futures’ (Jahel et al. Citation2021). However, within the neoliberal university such an exploration of alternatives has not been perceived to be the case in practice. In their response to the Covid-19 crisis senior managers have become even more entrenched in neoliberal ideology. In their survey of UK academics, Watermeyer et al. (Citation2021) found that in response to the Covid-19 pandemic, senior management teams were seen to consolidate centralized decision-making with the imposition of ‘disaster managerialism’. This involves the exploitation of the crisis for positional gain and neglecting the wellbeing of the workforce while simultaneously curating an image of the benevolent employer. This has served to strengthen the neoliberal narrative monoculture (Gabriel Citation2016) that can lead to a dearth of any alternatives from the dominant linear pathway leading towards the ‘neoliberal destruction of higher education’ (Wright and Greenwood Citation2017).

The narrative ecology within universities needs to be constantly challenged and re-invigorated in order to maintain ecological resilience and ecosystem vitality. Addressing the six questions posed by Misiaszek and Rodrigues (Citation2023) will help in this regard, so long as ‘answers’ do not become ‘fixed’ into dogma, and the act of ‘questioning’ is seen as an ongoing process of maintenance within an eco-philosophy of ‘becoming’ to reflect the dynamism of the system – rather than particular answers establishing themselves as part of a managerial philosophy of ‘being’. Ultimately one might ask if years of conditioning by neoliberal discourses that have demanded reductive simplifications have also left university managers lacking the imagination or the skill set to deal with complexity in the manner required to oversee the ecological university? Short-termism that is manifest in university strategy documents, that typically cover no more than the next few years, seems to be more in rhythm with political cycles and responsive to the corporate puppeteers who pull the strings of neoliberal discourses of the sector rather than the academic discourses representing the professional values that drive university academics. Failure to recognize and address the ecological crisis that looms over our universities and threatens any progress in terms of social justice, may well lead to the same situation as currently being faced by the biological environment; that is a ‘silent spring’ (sensu Carson Citation1962), in which the rich narrative ecology has lost its voice and is reduced to a sterile monoculture of dominant narratives, signaling ecological collapse. In such an environment, justice-based environmental sustainability will fall off the managerial agenda.

Dialogue with other papers in this issue

The arguments presented above in this paper offer considerable overlap with those presented in Ajaps (Citation2023) and they can be seen to offer some additional nuance to the concepts presented here (summarized in ). Central to Ajaps (Citation2023) argument is the need to accept an ecology of knowledges that recognizes the value of non-Western epistemologies. I agree that this should not be considered as a hierarchy of knowledges where one epistemology is seen as superior to another, but rather as an ecological consilience (sensu Wilson Citation1998) in which the different epistemologies are each seen to contribute to an overall ecological perspective, and avoiding the North–South and human-posthuman binaries that may create tensions and inhibit progress (e.g. Rodrigues et al. Citation2020). However, this will play out differently within different disciplinary arenas: for example, within the natural sciences it has been shown that academics find it very difficult to accept the validity of any form of knowledge that cannot be recognized as scientific (see Skopec et al. Citation2021), and so simply making knowledge available will be insufficient for its incorporation into a curriculum. Such knowledge will need to be carefully curated (e.g. Bradley Citation2022) to ensure it is not simply rejected. Ajaps (Citation2023) also talks about the imbalance in globalization as a constraint, particularly where some countries have ‘globalizing powers’ whereas others are ‘globalized’. It seems that it is the asymmetry inherent within globalization that is the problem rather than the being globally connected per se – after all, the acceptance of epistemologies of the South into the pedagogies of the Global North requires a degree of connectedness. Evidently, we need to reframe the concept of globalization to ensure that it is not conflated with ideas such as colonization or domination, highlighting the need to continually clarify terminology so that words do not carry unhelpful conceptual baggage that can create unintended suggestions. Another such instance of this occurs when Ajaps (Citation2023) refer to ‘pedagogical inconsistency’, which then then modify as ‘incompatibility’. I suggest that one person’s ‘inconsistency’ might be another’s ‘diversity’. And whilst I understand Ajaps' suspicions about ‘structured education’ and ‘classroom activities’, there is an inevitability that these elements will persist within our education systems. I see the diversity of terms summarized by Ajaps (Citation2023) as an indicator that ‘inconsistency’ or ‘diversity’ of application is inevitable, and even necessary to ensure ecological resilience and the transition to a new basin of attraction [as discussed in Bills and Klinsky Citation2023. However, it does suggest that academics need to have a common framework (such as the ecological university) to help make sense of these approaches and to align them with values that underpin an agenda to promote eco-social justice.

A focus on ‘the environment’ has been described by Code (Citation2006) as a catalyst for the development of ecological thinking. This has been explored in greater depth in this issue by McCowan (Citation2023) who see the climate crisis as a driver for pedagogical renewal. This is a good place for many to start to engage in a journey towards an ecological university. However, we must also take care to ensure that ‘ecological thinking’ is not confused with ‘thinking about ecology’. The ecological university has the potential to change thinking in disciplinary areas where teachers may struggle (at least initially) to make helpful links with their disciplinary knowledge. To move our teaching to a new ecological perspective, we must ensure that we are not distracted by issues that, while important in themselves, may not necessarily help our navigation from the neoliberal to the ecological university.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Ajaps, S. 2023. Deconstructing the constraints of justice-based environmental sustainability in higher education. Teaching in Higher Education 28, no. 5: 1024–38. doi:10.1080/13562517.2023.2198639.

- Aktaș, C.B. 2021. Enhancing social justice and socially just pedagogy in higher education through participatory action research. Teaching in Higher Education, doi:10.1080/13562517.2021.1966619.

- Allen, K.E., S.P. Stelzner, and R.M. Wielkiewicz. 1999. The ecology of leadership: Adapting to the challenges of a changing world. Journal of Leadership Studies 5, no. 2: 62–82. doi:10.1177/107179199900500207.

- Andreotti, V., C. Ahenakew, and G. Cooper. 2011. Epistemological pluralism: Ethical and pedagogical challenges in higher education. AlterNative 7, no. 1: 40–50. doi:10.1177/117718011100700104.

- Ansell, C., A. Boin, and M. Farjoun. 2015. Dynamic conservatism: How institutions change to remain the same. In Institutions and ideals: Philip Selznick’s legacy for organizational studies, ed. M.S. Kraatz, 89–119. Bingley, UK: Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

- Barnett, R. 2011a. The coming of the ecological university. Oxford Review of Education 37, no. 4: 439–55. doi:10.1080/03054985.2011.595550.

- Barnett, R.A. 2011b. The idea of the university in the twenty first century: Where’s the imagination? Journal of Higher Education 1, no. 2: 88–94. doi:10.2399/yod.11.088.

- Beattie, M. 1995. Constructing professional knowledge in teaching: A narrative of change and development. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

- Bennett, K. 2015. Towards an epistemological monoculture: Mechanisms of epistemicide in European research publication. In English as a scientific and research language, eds. D. Britain, and C. Thurlow, 9–36. Berlin/Boston: Walter de Gruyter Inc.

- Berkovich, I. 2014. A socio-ecological framework of social justice leadership in education. Journal of Educational Administration 52, no. 3: 282–309. doi:10.1108/JEA-12-2012-0131.

- Bills, H., and S. Klinsky. 2023. The resilience of settler colonialism in higher education: A case study of a western sustainability department. Teaching in Higher Education 28, no. 5: 969–86. doi:10.1080/13562517.2023.2197111.

- Botticello, J. 2020. Engaging many voices for inclusivity in higher education. Journal of Impact Cultures 1, no. 1: 22–38. doi:10.15123/uel.8805x.

- Bowers, C.A. 2001. How language limits our understandings of environmental education. Environmental Education Research 7, no. 2: 141–51. doi:10.1080/13504620120043144.

- Bowers, C.A. 2002. Toward an eco-justice pedagogy. Environmental Education Research 8, no. 1: 21–34. doi:10.1080/13504620120109628.

- Bradley, J.P.N. 2022. On the curation of negentropic forms of knowledge. Educational Philosophy and Theory 54: 465–76. doi:10.1080/00131857.2021.1906647.

- Burns, H.L. 2015. Transformative sustainability pedagogy: Learning from ecological systems and indigenous wisdom. Journal of Transformative Education 13, no. 3: 259–76. doi:10.1177/1541344615584683.

- Canning, J., and R. Masika. 2022. The scholarship of teaching and learning (SoTL): The thorn in the flesh of educational research. Studies in Higher Education 47, no. 6: 1084–96. doi:10.1080/03075079.2020.1836485.

- Carson, R. 1962. Silent Spring. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

- Charteris, J. 2014. Epistemological shudders as productive aporia: A heuristic for transformative teacher learning. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 13, no. 1: 104–21. doi:10.1177/160940691401300102.

- Clegg, S. 2016. The necessity and possibility of powerful ‘regional’ knowledge: Curriculum change and renewal. Teaching in Higher Education 21, no. 4: 457–70. doi:10.1080/13562517.2016.1157064.

- Code, L. 2006. Ecological thinking: The politics of epistemological location. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Davis, H. 2010. Other-centredness as a leadership attribute: From ego to eco centricity. Journal of Spirituality, Leadership and Management 4, no. 1: 43–52. http://www.slam.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/JSLaMvol4-2010.pdf#page=49.

- Edwards, R. 2022. Why do academics do unfunded research? Resistance, compliance and identity in the UK neo-liberal university. Studies in Higher Education 47, no. 4: 904–14. doi:10.1080/03075079.2020.1817891.

- Fleming, P. 2021. The Ghost University: Academe from the Ruins. Emancipations: A Journal of Critical Social Analysis 1, no. 1: 4. https://scholarsjunction.msstate.edu/emancipations/vol1/iss1/4.

- Fortunato, M.W.P. 2017. Advancing educational diversity: Antifragility, standardization, democracy, and a multitude of education options. Cultural Studies of Science Education 12: 177–87. doi:10.1007/s11422-016-9754-4.

- Furman, G.C., and D.A. Gruenewald. 2004. Expanding the landscape of social justice: A critical ecological analysis. Educational Administration Quarterly 40, no. 1: 47–76. doi:10.1177/0013161X03259142.

- Gabriel, Y. 2016. Narrative ecologies and the role of counter-narratives: The case of nostalgic stories and conspiracy theories. In Counter-narratives and Organization, eds. S. Frandsen, T. Kuhn, and M.W. Lundholt, 208–26. London: Routledge.

- Giroux, H.A. 2013. The disimagination machine and the pathologies of power. symplokē 21, no. 1: 257–69. doi:10.5250/symploke.21.1-2.0257.

- Grant, B. 2021. Becoming teacher as (in)activist: Feeling and refusing the force of university policy. Policy Futures in Education 19, no. 5: 539–53. doi:10.1177/14782103211004038.

- Gravett, K. 2021. Troubling transitions and celebrating becomings: From pathway to rhizome. Studies in Higher Education 46, no. 8: 1506–17. doi:10.1080/03075079.2019.1691162.

- Guttorm, H., R. Hohti, and A. Paakkari. 2015. Do the next thing: An interview with Elizabeth Adams St. Pierre on Post-qualitative methodology. Reconceptualizing Educational Research Methodology 6, no. 1: 15–22. doi:10.7577/rerm.1421.

- Holling, C.S. 1996. Engineering resilience vs. ecological resilience. In Engineering within ecological constraints, ed. P.C. Schultze, 31–43. Washington: National Academy Press.

- Holling, C.S. 2001. Understanding the complexity of economic, ecological, and social systems. Ecosystems 4: 390–405. doi:10.1007/s10021-001-0101-5.

- Jahel, C., R. Bourgeois, D. Pesche, M. de Lattre-Gasquet, and E. Delay. 2021. Has the COVID-19 crisis changed our relationship to the future? Futures & Foresight Science 3, no. 2: e75. doi:10.1002/ffo2.75.

- Ketschau, T.J. 2015. Social justice as a link between sustainability and educational sciences. Sustainability 7: 15754–71. doi:10.3390/su71115754.

- Kinchin, I.M. 2016. The mapping of pedagogic frailty: A concept in which connectedness is everything. In Innovating with Concept Mapping, edited by A. Cañas, P. Reiska, and J. Novak, 229–40. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Kinchin, I.M. 2017. Visualising the pedagogic frailty model as a frame for the scholarship of teaching and learning. PSU Research Review 1, no. 3: 184–93. doi:10.1108/PRR-12-2016-0013.

- Kinchin, I.M. 2022a. Exploring dynamic processes within the ecological university: A focus on the adaptive cycle. Oxford Review of Education 48, no. 5: 675–92. doi:10.1080/03054985.2021.2007866.

- Kinchin, I.M. 2022b. The ecological root metaphor for higher education: Searching for evidence of conceptual emergence within University Education Strategies. Education Sciences 12, no. 8: 528. doi:10.3390/educsci12080528.

- Kinchin, I.M. 2023. How to mend a university: Towards a sustainable learning environment in higher education. London: Bloomsbury (In Press).

- Kinchin, I.M., and K. Gravett. 2022. Dominant discourses in higher education: Critical perspectives, cartographies and practice. London: Bloomsbury.

- Kinchin, I.M., and A.E. Thumser. 2021. Mapping the ‘becoming-integrated-academic': An autoethnographic case study of professional becoming in the biosciences. Journal of Biological Education, doi:10.1080/00219266.2021.1941191.

- Kinchin, I.M., and N.E. Winstone, eds. 2017. Pedagogic frailty and resilience in the university. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

- Kinchin, I.M., and N.E. Winstone, eds. 2018. Exploring pedagogic frailty and resilience: Case studies of academic narrative. Leiden: Brill.

- Kinder, T., J. Stenvall, F. Six, and A. Memon. 2021. Relational leadership in collaborative governance ecosystems. Public Management Review 23, no. 11: 1612–39. doi:10.1080/14719037.2021.1879913.

- Luckett, K., and S. Shay. 2017. Reframing the curriculum: A transformative approach. Critical Studies in Education 61, no. 1: 50–65. doi:10.1080/17508487.2017.1356341.

- Maesse, J. 2017. The elitism dispositif: Hierarchization, discourses of excellence and organizational change in European economics. Higher Education 73, no. 6: 909–27. doi:10.1007/s10734-016-0019-7.

- McCowan, T. 2023. The climate crisis as a driver for pedagogical renewal in higher education. Teaching in Higher Education 28, no. 5: 933–52. doi:10.1080/13562517.2023.2197113.

- Misiaszek, G.W. 2020. Ecopedagogy: Teaching critical literacies of ‘development’, ‘sustainability’, and ‘sustainable development’. Teaching in Higher Education 25: 615–32. doi:10.1080/13562517.2019.1586668.

- Misiaszek, G.W., and C. Rodrigues. 2022. Six critical questions for teaching justice-based environmental sustainability (JBES) in higher education. Teaching in Higher Education 28, no. 1: 211–19. doi:10.1080/13562517.2022.2114338.

- Morini, L. 2020. The anti-ecological university: Competitive higher education as ecological catastrophe. Philosophy and Theory in Higher Education 2, no. 2: 45–66. doi:10.3726/PTIHE022020.0003.

- Paraskeva, J.M. 2022. The generation of the utopia: Itinerant curriculum theory towards a ‘futurable future’. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education 43, no. 3: 347–66. doi:10.1080/01596306.2022.2030594.

- Parsons, C., and B. Fidler. 2005. A new theory of educational change–punctuated equilibrium: The case of the internationalisation of higher education institutions. British Journal of Educational Studies 53, no. 4: 447–65. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8527.2005.00306.x.

- Pinto, J.P., P.J. Ramírez-Angulo, T.J. Crissien, and K. Bonett-Balza. 2021. The creation of dystopias as an alternative for imagining and materializing a university of the future. Futures 134: 102832. doi:10.1016/j.futures.2021.102832.

- Prádanos, L.I. 2015. The pedagogy of degrowth: Teaching hispanic studies in the age of social inequality and ecological collapse. Arizona Journal of Hispanic Cultural Studies 19: 153–68. doi:10.1353/hcs.2016.0029.

- Rodrigues, C., and G. Lowan-Trudeau. 2021. Global politics of the COVID-19 pandemic, and other current issues of environmental justice. The Journal of Environmental Education 52, no. 5: 293–302. doi:10.1080/00958964.2021.1983504.

- Rodrigues, C., P.G. Payne, L.L. Grange, I.C. Carvalho, C.A. Steil, H. Lotz-Sisitka, and H. Linde-Loubser. 2020. Introduction: “New” theory, “post” North-South representations, praxis. The Journal of Environmental Education 51, no. 2: 97–112. doi:10.1080/00958964.2020.1726265.

- Ross, F.M., J.C. Tatam, A.L. Hughes, O.P. Beacock, and N. McDuff. 2018. The great unspoken shame of UK higher education: Addressing inequalities of attainment. African Journal of Business Ethics 12, no. 1: 104–15. doi:10.15249/12-1-172.

- Santos, B.de.S. 2014. Epistemologies of the South: Justice against Epistemicide. London: Routledge.

- Shay, S., and T. Peseta. 2016. A socially just curriculum reform agenda. Teaching in Higher Education 21, no. 4: 361–6. doi:10.1080/13562517.2016.1159057.

- Skopec, M., M. Fyfe, H. Issa, K. Ippolito, M. Anderson, and M. Harris. 2021. Decolonization in a higher education STEMM institution – is ‘epistemic fragility’ a barrier? London Review of Education 19: 1–21. doi:10.14324/LRE.19.1.18.

- Soga, M., and K.J. Gaston. 2016. Extinction of experience: The loss of human-nature interactions. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 14, no. 2: 94–101. doi:10.1002/fee.1225.

- Sterling, S. 2004. Higher Education, sustainability and the role of systemic learning. In Higher Education and the challenge of sustainability: Contestation, critique, practice and promise, eds. P.B. Corcoran, and A. E. J. Wals, 49–70. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic.

- Stratford, R. 2015. What is the ecological university and why is it a significant challenge for higher education policy and practice? Melbourne: PESA-Philosophy of Education Society of Australasia, ANCU. https://www.academia.edu/19661131.

- Tikly, L. 2011. A roadblock to social justice? An analysis and critique of the South African education roadmap. International Journal of Educational Development 31, no. 1: 86–94. doi:10.1016/j.ijedudev.2010.06.008.

- Watermeyer, R., K. Shankar, T. Crick, C. Knight, F. McGaughey, J. Hardman, V.R. Suri, R. Chung, and D. Phelan. 2021. ‘Pandemia’: A reckoning of UK universities’ corporate response to COVID-19 and its academic fallout. British Journal of Sociology of Education 42, no. 5–6: 651–66. doi:10.1080/01425692.2021.1937058.

- Wilson, E.O. 1998. Consilience: The unity of knowledge. London: Abacus.

- Wong, B., J. DeWitt, and Y.-L.T. Chiu. 2023. Mapping the eight dimensions of the ideal student in higher education. Educational Review 75, no. 2: 153–71. doi:10.1080/00131911.2021.1909538.

- Wooten, M.M. 2018. A cartographic approach toward the study of academics of science teaching and learning research practices and values. Canadian Journal of Science, Mathematics and Technology Education 18, no. 3: 210–21. doi:10.1007/s42330-018-0029-9.

- Wright, S., and D.J. Greenwood. 2017. Universities run for, by, and with the faculty, students and staff: Alternatives to the neoliberal destruction of higher education. Learning and Teaching 10, no. 1: 42–65. doi:10.3167/latiss.2017.100104.