ABSTRACT

This paper discusses the significance of personalised learning pedagogies in relation to developing new professional identities whilst pursuing a degree and facilitating student progression and retention. The data derived from conducting a case study focusing on culturally diverse cohorts of students completing a BSc (Hons) Counselling practitioner qualification degree at the University of East London, a discipline that requires high levels of personal reflexivity and the ‘use of self’ in translating theory to practice. A review of the course teaching styles, modes of delivery, academic advising and pastoral care provision was conducted alongside collating the final year cohort’s reflections and feedback via a focus group. The findings allow the suggestion that elements strengthen the relational quality of interaction between lecturers and learners alongside diversifying learning activities to meet more ‘personalised’ needs, fostering a learning environment that promotes student satisfaction, advances inclusivity, reduces the award gap and improves course completion.

Introduction

Personalised learning (Claxton Citation2006) is a value-based and learner-centric pedagogy that recognises the specific learning style and individual differences of each student and should be considered when designing and delivering training curricula that assists students in expressing their potential based on their readiness, strengths, needs, and interests.

Research focusing on reasons for dropping out of higher education (Lipson and Eisenberg Citation2018; Truta, Parv, and Topala Citation2018) presents a strong relationship between positive psychosocial environments, students’ satisfaction and study completion. Personalised learning entails teaching and learning strategies that develop the competence and confidence of every learner. But what specifically creates such a learning environment and a motivational mindset for students to acquire a committed and dynamic attitude towards their studies? We are using the example of an undergraduate counselling degree as a case study to explore these questions, given that the nature of such discipline often attracts learners who may be unconsciously motivated to pursue such subjects by a desire to resolve personal traumas or answer troubling existential questions (Barnett Citation2007).

The context of counselling training and the relevance of a personalised pedagogy

Counselling training engages students in a developmental process of self-discovery and competence building where the main tool is the ‘use of self’ (Blundell et al. Citation2022). It is a discipline that strives towards protecting and celebrating identity, therefore it is necessary that when future practitioners are in the process of acquiring knowledge and skills, such a personalised approach to teaching is compatible with their personal and professional development (McLeod and McLeod Citation2014) Similarly, to the idea that a child develops at their own pace, even though they are expected to reach developmental milestones, counsellors also grow their new professional identities at their own pace, depending on factors such as age, learning styles, history of trauma or mental health, a previous career or engagement with personal development activities before embarking on formal practitioner training. How does such a student profile fit within a university setting? How can we employ personalised learning pedagogies within the restrictions of HE structures? Below we present the case study of the UG counselling degree at the University of East London.

The BSc (Hons) Counselling programme at the University of East London

The BSc (Hons) Counselling at UEL is a 3-year full-time practitioner degree which was designed to meet the standards of gaining BACP (British Association for Counselling and Psychotherapy) in 2014. Situated at the heart of Newham in East London, it attracts learners from a wide range of ethnic, cultural and religious backgrounds across different age groups, including a substantial number of mature applicants seeking a career transition.

This training is also embedded within a learning environment that mirrors the ethos of pluralistic therapy (Cooper and McLeod Citation2010). A modern and intellectually active counselling paradigm grounded within an epistemology which promotes dialogical collaboration, values self- knowledge and embodies an attitude of acceptance around different theoretical approaches to provide treatment that is personalised, adaptive and co-constructed (Cooper et al. Citation2019).

This approach offers equality, accessibility and inclusivity to all stakeholders by nurturing the student’s existing knowledge to build confidence and privilege lived experiences (Ausubel, Novak, and Hanesian Citation1978). In terms of pluralistic practice, this interfaces with the notion of producing self-deterministic and empowered counsellors who are trained to incorporate a portfolio of previously acquired skills in the counselling room (Bager-Charleson Citation2010), creating a synergy between pedagogical approach and professional application (Tilley, McLeod, and McLeod Citation2015) which encourages the student to engage in continuous professional development that progresses the values, principles, morals and evidence-based practice that aligns with the standards required by the leading professional bodies. The privileging of transferable experiences is also an important motivator in building confidence and promoting engagement of the high numbers of mature trainees who are apprehensive about returning to education or do not hold recently acquired qualifications (BACP Citation2019; Coldridge and Mickelborough Citation2003).

This prioritising of counsellor autonomy is a crucial aspect of training that prepares trainees for navigating the increasingly rapid neo-liberalisation of the sector (Bondi Citation2005) and responds to the critique by Murphy (Citation2011) who suggested that structural inequalities are reaffirmed by the fact that even though the profession is still officially ‘ungoverned’ by the state, it demands practitioners hold personal responsibility to implement ethical practice to avoid both harm and litigation. The training environment also encourages trainees to recognise using ‘humility’ to address complex power dynamics in client work by understanding the cultural nuances of institutional disadvantage, being open to unfamiliar experiences and incorporating feedback reflexively (Watkins and Mosher Citation2020). This idea of placing the student as competent, experienced and valuable is always going to be constrained due to the learning relationship being situated within the traditional power relationship between academic and student (Morley Citation2003). However, by constantly revisiting the idea of reflective self-development and interfacing with the pluralistic model, these power balances are continuously monitored and even though academic expertise is highly valued, this is applied with collaborative care and consideration that deconstructs traditional dynamics and promotes progressive pedagogy (Symonds Citation2021). In many ways, this reaffirms the favoured clinical paradigm of client-focused work (Fuertes and Nutt Williams Citation2017) by centralising the student experience and personalising the expertise of the academic staff to each student, rather than recreating traditional knowledge exchanges that can fetishize ‘guru-led practice’ within a transactional learning environment which diminishes student agency (Lomas Citation2007) and creates a consumer-driven mindset that constrains student outcomes (Bunce, Baird, and Jones Citation2017).

This power balance is further addressed within our training by academic staff modelling the idea of pedagogical reflexivity as a way of disrupting traditional hierarchies within the learning environment (Iszatt-White, Kempster, and Carroll Citation2017). An example of this is that academics are encouraged to bring aspects of themselves to their teachings through professional case studies and personal anecdotes to situate the curriculum within professional encounters (Cayanus Citation2004) and encourage debate around biographical experiences (Blundell et al. Citation2022).

The introduction of a teaching style that reveals intimate parts of the educator’s life can promote attention, demystify anxiety triggers, improve engagement and bring enjoyment to the learning (Henry and Thorsen Citation2021). Although, the use of self is not a new idea within counselling (Wosket Citation2016), as many modalities actively introduce aspects of the counsellor as part of the therapeutic work to both temper the fantasy of counsellors living romanticised lives and facilitate the therapeutic alliance (Henretty and Levitt Citation2010). This use of self-disclosure is less apparent in higher education and academics can sometimes be perceived as distant and abstracted from the vocational aspects of their respective disciplines, especially for subjects outside of the social sciences and arts (Cayanus and Martin Citation2008). Drawing upon this pluralistic worldview and capitalising upon the pedagogical opportunity of counselling academics also being practitioners (BACP Citation2021) means that reflexive self-disclosure can be easily transposed from the treatment room to the teaching space (Etherington Citation2017).

The benefit of connecting the theoretical to the practical provides both richness and animation to what could be a dry representation of clinical practice. It also models how students may personalise their emerging theoretical model and naturally interfaces to the qualitative research paradigm that celebrates the active presence of the researcher in the analytical process (Watt Citation2007). Once again, this is a vital benefit of humanism within counsellor training, as students often avoid researching due to feeling scientifically marginalised and disconnected from empiricism (Bager-Charleson, McBeath, and Plock Citation2018). This reticence is not only detrimental to the growth of evidence-based practice but also creates a schism between the academic and the professional where non-practitioners dictate theoretical direction. This can create idealised practices that are disconnected from the ‘messiness’ of the profession (Schön Citation1983) and most importantly, restricts the distinctive phenomenology of how academic conjecture can be pragmatically implemented (McDonnell et al. Citation2012).

To take a student-centred approach (Baeten, Struyven, and Dochy Citation2013), it is crucial to learn what constitutes a teaching space that encourages participation, curiosity, critical thinking and a ‘safe enough’ environment (Holley and Steiner, Citation2005) that allows the discussion of controversial issues such as cultural competency, oppression and ethics that emerge during counsellor training (Feltham Citation2010). To accomplish this, students are typically invited to be introspective by sharing their worldviews to further understand how complex intersections of identity and privilege, exposure to multiculturalism and unconscious bias impact communication and behaviour (Dee and Gershenson Citation2017). These activities represent the foundations of a self-interrogating style of personal development that importantly relies on students to be responsible and nurture their interpersonal qualities through engagement with individualistic processes of personal therapy, self-awareness and inner reflection (Bennett-Levy and Haarhoff Citation2019).

These worldviews are then shared within personal development spaces that allow students to mobilise creative skills of improvisation to foster collective understanding by situating the learner in a relatable context and lived experience (Mann, Gordon, and MacLeod Citation2009). The newly abstracted ideas are then formally conceptualised and reinforced through assessed learning that requires students to integrate their identity components into a pedagogical framework by completing various summative assessments (Biggs Citation2014). These include portfolios, creative collages and the group debating of perennial ethical dilemmas (McLeod Citation2000) in the presence of a critical audience (Butler and Winne Citation1995). The significance of implementing a learning paradigm that scaffolds attaining academic understanding through application and creative interpretation is that all students can develop critical thinking and reflexivity regardless of scholarly ability and favoured learning style (Race Citation2019).

Besides the philosophical underpinnings described above, there are some practices we have acquired that resulted from contemplating the following questions, which were adopted as our research questions for this paper:

How do we facilitate personalised learning on such a programme that considers learners’ ongoing professional identity development?

How do we enhance the student experience and support academic progression that is congruent to the development of a new role where the ‘use of self’ is the main tool?

Some examples of ‘how’ we approach this on the course at UEL are

Competence-based progression

Continuous assessment that monitors the developmental process of each student and allows for timely support that will assist the learner to reach the standards required to begin placement with real clients in community counselling services. This means that each student develops at their own pace, whilst using the functions of personal therapy, clinical supervision and ongoing tutor and peer feedback to facilitate progress and reach the developmental milestones required to perform the counsellor role. Students are given tutor and peer feedback ‘in real time’ during triad practice weekly.

Tutorials and academic advising

Regular meetings are offered that allow for each student and tutor to set both short-term and long-term goals and ways towards achieving those. Also, a space to voice personal difficulties that may require input from different support services or making an informed decision about taking a study break. It is important that counselling trainees develop their reflexivity to be able to make ethical decisions.

Inviting students to form their curriculum

Whilst the course curriculum has been designed based on specific theories and skills that a counsellor shall acquire as part of their core training, there is scope in some modules for a student to propose a specific topic where they acknowledge a gap in their knowledge. For example, students are invited to suggest a topic under the ‘Working with … ’ series that covers specific client groups or propose topics of interest for their optional summer workshops. They can also choose optional modules from different departments to diversify their knowledge and skills.

Empowering low-performing or marginalised groups in the classroom through topics that are often avoided or considered ‘taboo’

It is often suggested that students under specific ethnic or socio-cultural backgrounds fall under what is called ‘the attainment gap’, something that sometimes can also be reinforced by unconscious bias or unacknowledged dynamics of white privilege and structural racism that may exist amongst staff (Bunce et al. Citation2021). Lecturers need to be actively engaging in their own personal and professional development to be able to question and review their attitudes and delivery. Considering a learner’s context and history, adapting teaching techniques, and incorporating social experiences outside the university are some ways that can facilitate embracing cultural, racial/ethnic, and linguistic diversity (Blundell et al. Citation2022). When a diverse student experience is acknowledged and celebrated, learners are less likely to feel disconnected from their studies and communities which would inevitably impede their learning (Berry and Candis Citation2013; Gay Citation2018). Culturally responsive teaching and engaging learners with protected characteristics are part of the core objectives and philosophy of the course as we aim at supporting future graduates who will become equitable and ethical practitioners.

Self-direction and self-reflection at the core of assessment

Self and peer assessment are continuous, and formative opportunities before the summative submissions are suitably scheduled each term. It is worth noting that one of the challenges we have encountered is the potential tensions that can arise between the reflective stances we expect students to undertake in their essay writing or experiential learning activities and evidencing specific learning outcomes that hold the academic standards in place (Briggs, Clark, and Hall Citation2012). This requires a sensitive approach towards holding clear boundaries in our dual roles as tutors where, on one hand, we offer pastoral support to students when ‘life happens’ and on the other hand, it is within our role to assess their work. The way we have approached that as a team is via acquiring an attitude drawn from Starr’s (Citation1982) conceptualisation of vocational occupation that emphasises cultivating a sense of ownership and professional conscience in students when interacting with them:

A pro- fession is an occupation that regulates itself through systematic, required training and collegial discipline; that has a base in technical, specialized knowledge; and that has a service rather than profit orientation enshrined in its code of ethics. (Starr Citation1982, 15)

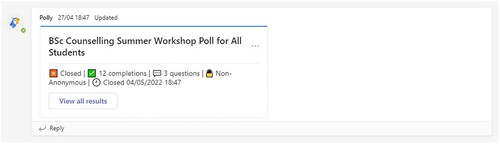

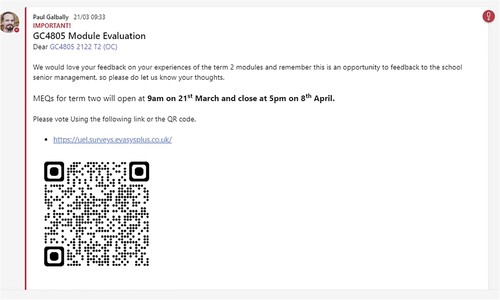

Inviting students for feedback using virtual learning spaces (MS Teams, Polly, Evasys)

Students are regularly engaged in a collaborative forum hosted on Microsoft Teams that allows tutors to offer guidance on assessment, share resources and provide feedback that all students can access and respond to. This virtual and collaborative style of interaction fosters a sense of scholarly community amongst students and encourages additional learning and engagement between formalised curriculum activities (Alves, Miranda, and Morais Citation2017). Additionally, these online communities are separated into specialised teams that allow students to receive targeted information by sending general items such as external training opportunities to all students and communicating more specific information on summative assessments or recently attended lectures via customised module teams. The use of dynamic and ‘live’ virtual feedback mechanisms is more critical and in-depth when compared to classroom-based methods and has also been found to be vital in setting up good communicative and engagement practices with first-year students (McCarthy Citation2017).

Alongside the use of MS Teams as a forum, we have also introduced specific data collection tools that can gauge quick opinions on items such as preferred summer workshops topics through Polly ( – https://www.polly.ai/microsoft-teams) and more formalised data harvesting of institution-required module evaluations via the online platform EvaSys (. https://Evasys.co.uk/). The interfacing of in-person teaching and skills practice with extracurricular engagement in a virtual space offers a variety of benefits by most obviously connecting students to their courses when not on campus. Additionally, it acts as a social platform for students who are less vocal in a classroom environment to be part of the conversation and offers a cognitive opportunity for those who prefer to communicate asynchronously (Galikyan and Admiraal Citation2019).

Figure 2. Example of requesting student feedback on a recently attended module hosted through the MS Teams specific module team.

Furthermore, these add-on tools allow students to effortlessly respond to academic discussion, social chatter, evaluation and assessment using a variety of digital interfaces such as smartphones and laptops and access electronic resources via dynamic hyperlinks or digital QR codes; functions that promote engagement and completion through user-friendly interfaces (Tan et al. Citation2022). This collective workspace also prioritises representing the student voice throughout the course and not just at traditional evaluation points such as the end of a module or teaching semester. Importantly, the dynamic and live virtual classroom provides agency to the student and creates a sense of empowerment which promotes ownership of the course by providing each learner opportunity to adapt the curriculum for personalised pedagogy (Elen et al. Citation2007). It has also been shown that facilitating the evaluation experience within a public academic forum improves agency and can reduce institutional inequalities by allowing students transparent access to historically esoteric university data analytics (Tsai, Perrotta, and Gašević Citation2020).

The shift in learning spaces and practices because of the COVID-19 pandemic

The pandemic that began in the spring of 2020 forced education institutions to adopt new modes of delivery and transformed teaching and learning. When it comes to the discipline of counselling and psychotherapy where students are expected to complete a placement with real clients in a counselling service, the lockdown restrictions led to the need for students to swiftly acquire knowledge and skills that would prepare them to continue with their placement via offering sessions remotely (BACP Citation2021). This shift in the online space of the relationship as well as an intellectual shift about how students perceive and manage relational dynamics when not in the same room with their clients presented the challenge for tutors to design suitable material for trainees who were required to make such a shift competently enough before they had the opportunity to refine the necessary skills when working ‘in the room’ (Christian, McCarty, and Brown Citation2021).

During our training at UEL, a collation of specialised material took place which led to the creation of an e-therapy portfolio that included relevant reading, podcasts, training videos, ‘live’ online lectures and weekly online clinical supervision to support students whilst making this transition. All their lectures, seminars and personal development activities started taking place online with immediate effect, something that contributed to both becoming confident with the use of technology and learning about relational dynamics in virtual spaces because of interacting with peers and tutors via the use of online platforms.

It is worth noting that everyone, students, and tutors alike, was affected by the pandemic, including getting ill, losing loved ones, disconnecting from family and friends, dealing with isolation, developing anxiety, losing financial stability, losing community support, experiencing grief or even trauma (Burns, Dagnall, and Holt Citation2020). In such circumstances, we had to review how we work and relate and consider how this collectively challenging episode affected our ability to meaningfully engage in both academic tasks and professional practice. It was well documented that the pandemic resulted in increased levels of psychological stress and exacerbated existing mental health issues in student populations (Zimmermann, Bledsoe, and Papa Citation2021). We were also acutely aware that many of our students fall into the latter category, as the ‘vocational call’ to follow a career in counselling is often initiated by experiences of familial health issues, personal trauma, mental health concerns or engagement with social or healthcare services (Adams Citation2014).

As much as this phenomenological biography is typically mobilised as an asset to empathy and visceral understanding during counsellor training (Zerubavel and O’Dougherty Wright Citation2012), the increased stress of the pandemic meant that some students struggled, and we observed an increase in vulnerability that elevated the level of pastoral support required (Burns, Dagnall, and Holt Citation2020). This unique interrelation of personality type and increased exposure to shared adverse psychological experiences meant that the typically positive ‘wounded healer’ archetype was susceptible to transforming into a less helpful ‘walking wounded’ (Conchar and Repper Citation2014). The implication was that not only were students potentially in danger of reduced well-being that could be detrimental to both personal lives and academic outcomes but also created a concern of students being unfit to practise by bringing unacceptable risk into clinical work (Tribe and Morrissey Citation2020).

Methodology

Footnote1To embody the student lead and co-creative ethos of this paper, the most collaborative choice of methodology was to take a qualitative approach that provided pedological insight from a student perspective. This was considered in accord with our desire to celebrate the student voices and it seemed fitting to collect these voices directly through a focus group. Winlow et al. (Citation2013) have successfully established the use of focus groups for studying pedagogy in UK Higher Education and provided several recommendations that we adopted. Firstly, they highlighted the importance of encouraging sharing opinions and the value of having an assembled cohort in place to discuss their course and institution with candour and a reflective group process. Secondly, they acknowledge the opportunity to collect enriched data from a variety of perspectives through a singular session and finally they promote the introduction of group dynamics which can enable less vocal students to share and provides insight into the interpersonal interactions within the group.

The recommendations of Winlow et al. (Citation2013) allowed us not only to build a sound rationale for the use of focus groups but also connected the method to our research aims of understanding personalised pedagogy, academic support and the prioritising of student storytelling that could aid developing a ‘lived’ curriculum via a process of ‘collective sense-making’ (Wibeck, Dahlgren, and Öberg Citation2007, 249). With this in mind, we considered the selection of this group by taking a purposeful sample (Ritchie et al. Citation2014) of final-year students who not only had collective experiences and exposure to being on the programme (Breen Citation2006) but were also were familiar with each other and the staff within a naturalised educational setting (Hydén and Bülow Citation2003). The latter point was fundamental in alerting us to be mindful of addressing the ethical dilemma of natural power differentials between academics and students (Iszatt-White, Kempster, and Carroll Citation2017) by holding the group outside traditional class schedules, outside final marking periods and being candid about a discussion that had permission to be critical of the pastoral support, the institution and the teaching.

The group size was agreed to be ten students and two facilitators which corresponded with recommendations of having a lively well-managed group that allowed for an inclusive and open dialogical (Hydén and Bülow Citation2003). To maintain an ethical research stance (Breen Citation2006), we briefed potential attendees in advance of the purpose of the group and on the day the sample was self-selected and then consented to the research and recording at the start of the session. Our approach was flexible and conversational, but we also offered a brief introduction to the research to help focus the group (Wibeck, Dahlgren, and Öberg Citation2007) and worked from a semi-structured framework to ensure research aims were prioritised (Krueger and Casey Citation2015). This framework was built around the two key research questions, and we adopted a logical flow that made sure that we ‘funnelled’ the group from generalised experiences to specific topics that were introduced directly in the latter half of the session (Breen Citation2006). We were also careful to keep the duration of the session to the recommended length of between 1 and 2 h to avoid digressing, fatigue and tensions from group interactions (Krueger and Casey Citation2015).

The student voices

During spring 2022, we conducted a focus group session with the Level 6 final year cohort where we invited students to share their experience on the course as they have reached its final stage. The discussion was navigated around the following questions as conversation instigators:

How would you say that this course has felt unique or personalised to you? (Personalised Learning)

Follow Up: How has the course developed your own personal skills, strengths, and resources?

Have you found the academic advisory process useful? How? (Tutor Pastoral Input)

Follow up: How has engaging in this process developed your intellectual development and professional practice?

Did you feel that you were able to tell your story during the course? (Lived curriculum)

Follow up: In what situation/was it useful?

In this dialogue, it is interesting to share and reflect upon some of the students’ responses within the context of the two research questions:

Personalised learning

Abebi discussed studying for a law degree which she did not complete. She explained that our course developed self-awareness and self-reflection through what she termed ‘processing’ by engaging in activities such as PDG (Personal Development Group) and supervision. Her previous courses lacked a sense of embodied personalisation, and the learning was targeted towards tangible goals and objectives.

My first attempt at Uni was a law degree and obviously that’s such a completely different experience. It was ten years before now and just I can see like how comparatively there’s so much more focus on processing and self-awareness. I think there’s like a lot of processing that happens in this course […] And when I say processing, I mean like looking at things that are going on internally, emotionally … And that is kind of unique in this course.

I think that this course when compared to like when all my friends went to university, they had so many people in their year, and you know they when I talk about like Uni now to them and the fact that I know everyone on a first name basis […] I think that really impacts this course because it means that you feel able to bring yourself and you’re not … Like a stranger in the cohort.

I think that you know the bond between everyone would be so much stronger and we would all have been able to bring ourselves a lot more because I know for me, like when we came back in 3rd year it was, I was so I was so scared just to speak up because I felt like a stranger again and then we had to get to know each other.

But, uh, I think you know the knowledge, of course was good, but definitely looking back was the human interactions. Because the knowledge made more sense through the human interactions.

I kind of wrote about this in my essay like developing alongside your peers like you can look and you can go like. Ohh I can actually see like how far you’ve come […] even if you didn’t have a sense of yourself changing and developing.

You know that for me was such a profound moment because it was like what they (the academics) were talking about. Seeing that process happening with like everyone, I saw that with my own two eyes, and it was really meaningful for me

The whole course was for me because a kind of lesson for setting boundaries in my life. We had lots of discussions and lectures and behind the PDG had personal therapy and our relationship with an academic advisor. All of them had different boundaries and showed me how I can set boundaries in my personal life with different people … And yeah, now when I reflect, I can see that it’s really impacted my personal life as well.

Student support

The above extract is an interesting segue into how student support is vital in facilitating students in creating a safe enough learning space that encourages cognitive, emotional and developmental growth and experimentation (Ali Citation2017). Niloufar previously explained her understanding of boundaries, but this was not imbued solely from theoretical lecturing and textbooks. Instead, her experience was relational and immersive, and her boundaries developed dynamically through interacting with experiential activities and academics in a variety of pedagogical environments such as pastoral tuition and PDG.

One common theme across the group was that students recognised and valued the academic staff moving from a position of depersonalisation by taking a stance of collaborative learning by ‘joining’ the student body in a way that allowed knowledge and wisdom to be shared without authoritarian power dynamics and the constraints of traditional stances of educational exceptionalism and expertise (Iszatt-White, Kempster, and Carroll Citation2017). Lisa compares her experience at UEL with a previous degree and remarks how the investment of the learner is reliant on a sense of ‘knowing the lecturers’, which was distinctly different from the traditionally expected academic relationships:

I don’t remember having that relationship with lecturers. There’s also a lot of the lecturers’ personality and feelings and you know them as well and I don’t think you normally have that knowledge or feel that level of sort of support is a different kind of support.

I mean you don’t hear about all you know, a lecturer’s child or that a lecturer was working with this person … Why would you ever hear that on another course? Yeah, I definitely found those experiences of lecturers who would speak about applications or give life examples or whatever. It really furthered my learning because it just … It just was like, ah, that’s what you’re saying

But I was just gonna say like the support for me towards the end of this course has been really helpful. And I think just having the opportunity to just be open and to speak about it made things a lot easier because sometimes you think … Who do I go to? What am I going to do? What’s the next step? How do I go about even getting help? So having that opportunity to ask it just made all the difference and that to me is the difference between someone continuing and someone dropping out.

When I told Jack (course lead at the time) that this is a bit much for me, he said that it’s OK for me to skip it if I feel like I can’t do it and then do it at home myself. So, there was this kind of possibility to adapt a bit and to kind of see whether I was ready to engage with something like that in front of the whole class … Kind of personalizing for me.

Discussion

The data collated above confirms that university students feel empowered and thrive within learning environments that encourage personal reflection that is valued as courageous than indulgent, well-boundaried but emotionally intimate relationships amongst peers and tutors and an atmosphere of respect and consideration towards individual needs and circumstances. This steps away from the more common disconnected or sterile atmosphere that can dominate academic settings and allow for a more ‘holistic’ approach (Miller et al. Citation2018).

In our experience, the positionality and teaching style of lecturers and educators plays a significant role in engaging students in a more visceral and committed way towards their studies. One of the frameworks that are useful in adopting such an approach is the ‘pedagogy of vulnerability’ (Brantmeier and McKenna Citation2020) which is defined by (Kelly and Kelly Citation2020, 177) as ‘purposeful and selective acts of self-disclosure by teachers [to] help build the conditions of trust and care needed for dialogue around emotionally and politically challenging topics.’ This is an approach that both authors of this article are bringing in class and in interactions with students, something that also broke barriers at the focus group discussion. It is this ‘humanising’ of the learning space and disrupting traditional hierarchies of power that supports them in making links between what they learn and real-life applications, hence bringing their interest and passion to the fore which translates to smooth progression and completion.

It is worth noting that valuing personalised learning in culturally diverse institutions like the one we find ourselves in East London is intricately linked to the commitment to decolonisation and addressing the ‘award gap’ when we talk about student attainment (Alexander and Arday Citation2015). Besides the courage for vulnerability which honours and holds the voices of minoritized groups, another framework that comes hand-in-hand are that of a ‘pedagogy of discomfort’ (Boler Citation1999; Boler and Zembylas Citation2003); in that discourse, there is ‘an invitation to the inquiry’ and a ‘call to action’ as evident in the quotes by student further above who brought both their personal insights in terms of their personal and professional development as a result of engaging in such level of experiential learning and a thirst to do something beyond their degree, to find ways to bring their impact to the profession and society more broadly.

Whilst this paper is showcasing a specific case study in the Psychology department within our institution, its significance and impact would be limited if we had not taken initiative to look for and collaborate with similar case studies within different disciplines in different departments.Footnote2 Some of these examples in other disciplines at UEL are the work on decolonisation of medical research and medical outcomes by Professor Winston Morgan at the Department of Bioscience, the work by Dr Michael Cole in Sport through critical whiteness studies (Cole Citation2021) and the work by Dr Anna Caffrey in Public Health and Nursing that is inspired by Powell et al. (Citation2022). In collaboration with the UEL Office of Institutional Equity, a series of training sessions for staff are regularly organised which have a focus to foster equitable and anti-racist pedagogies at an institutional and structural level.

This drive to improve inclusive pedagogy is encapsulated in an institutional charter (UEL Citation2020, 10) that seeks to ‘More than halve the attainment gap between White and Black full-time undergraduate students from a baseline of 19% to 9% by 2024–2025.’ It is worth noting that our course has already achieved this by implementing what has been outlined previously and recording an enrolment figure of 35.8% of our students being from a minority ethnic background and closing the award gap to 5.8% in 2020/21; A gap significantly smaller than the UK average of 8.5% and the university average of 11.4% (Abdalla Citation2022). Furthermore, through adopting an actively anti-racist stance we have also reduced our course dropout rates, an area in which students from minority ethnic backgrounds are significantly overrepresented (Petrie and Keohane Citation2017) to 5.9% in 2020/21, a figure that is 2.7% below UK higher education averages (HESA Citation2022). Finally, 91.3% of our 2020/21 graduates were awarded good honours, in comparison to the institution’s average of 75.4% (Abdalla Citation2022) and the national average of 82.1% (HESA Citation2022).

Final remarks: moving from the personal to the social

This paper provides empirical evidence of how our recommendations can profoundly impact attainment, inclusivity and student experience and contributes to understanding the benefits of adopting the personalised pedagogies outlined above. We also highlight some challenges and lessons along the way which can lead to disciplinary-specific adaptations, dependent on the student profile that tends to engage with a particular discipline. There is a limitation in attempting to draw some conclusions from such a small sample; however, given the case study is based on data collected in the context of counselling training, one could argue that the level of psychological mindedness and ability to articulate nuanced processes we often witness in such cohorts, offers the possibility of informing the broader thinking around pedagogic approaches that are to link the ‘personal’ to the ‘social. If we were to draw from Carl Rogers’s famous quote ‘What is most personal is most general.’ (Rogers Citation1961, 26), this could situate the field of psychology at the heart of social change (Cooper Citation2023) and invite contemplation on the more political dimensions of radical and inclusive pedagogies where students and tutors develop relationships that inspire activism and dismantle oppressive ideologies (Braveman et al. Citation2022) towards humanising and supporting a more equitable higher education.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 This paper was written on request of the University as part of the 2022 TEF submission and ethical approval was given to the authors to approach the student body to request participation. All students included in the analysis have consented to take part in the research and have been given culturally appropriate pseudonyms to respect privacy.

2 These developments are ongoing and this list of colleague’s work is not exhaustive.

References

- Abdalla, H. 2022. University of East London degree outcomes statement 2022. London: University of East London. https://uel.ac.uk/sites/default/files/degree-outcomes-statement-2022.pdf

- Adams, M. 2014. The myth of the untroubled therapist: Private life, professional practice. Hove, UK: Taylor & Francis.

- Alexander, C., and J. Arday. 2015. Aiming higher: Race, inequality and diversity in the academy. London: Runnymede Trust.

- Ali, D. 2017. Safe spaces and brave spaces. NASPA Research and Policy Institute 2: 1–13.

- Alves, P., L. Miranda, and C. Morais. 2017. The influence of virtual learning environments in students’ performance. Universal Journal of Educational Research 5, no. 3: 517–27. doi:10.13189/ujer.2017.050325

- Aristovnik, A., D. Keržič, D. Ravšelj, N. Tomaževič, and L. Umek. 2020. Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on life of higher education students: A global perspective. Sustainability 12, no. 20: 8438. doi:10.3390/su12208438

- Audet, C., and R.D. Everall. 2003. Counsellor self-disclosure: Client-informed implications for practice. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research 3, no. 3: 223–31. doi:10.1080/14733140312331384392

- Ausubel, D.P., J.D. Novak, and H. Hanesian. 1978. Educational psychology: A cognitive view. New York: Holt Rinehart and Winston.

- BACP. 2019. 2019 BACP membership survey. Lutterworth. https://www.bacp.co.uk/about-us/about-bacp/2019-bacp-membership-survey/.

- BACP. 2021. Criteria for the accreditation of training courses (Gold Book) including OPT criteria. Lutterworth. https://www.bacp.co.uk/membership/organisational-membership/course-accreditation/.

- Baeten, M., K. Struyven, and F. Dochy. 2013. Student-centred teaching methods: Can they optimise students’ approaches to learning in professional higher education? Studies in Educational Evaluation 39, no. 1: 14–22. doi:10.1016/j.stueduc.2012.11.001.

- Bager-Charleson, S. 2010. Chapter 3 – Culturally Tinted Lenses. In Reflective practice in counselling and psychotherapy, edited by Sofie Bager-Charleson, 54–71. Exeter, UK: Learning Matters Ltd.

- Bager-Charleson, S., A. McBeath, and S.D. Plock. 2018. The relationship between psychotherapy practice and research: A mixed-methods exploration of practitioners’ views. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research 19, no. 3: 195–205. doi:10.1002/capr.12196

- Barnett, M. 2007. What brings you here? An exploration of the unconscious motivations of those who choose to train and work as psychotherapists and counsellors. Psychodynamic Practice 13, no. 3: 257–74. doi:10.1080/14753630701455796

- Bennett-Levy, J., and B. Haarhoff. 2019. Why therapists need to take a good look at themselves: Self-practice/self-reflection as an integrative training strategy for evidence-based practices. In Evidence-based practice in action: Bridging clinical science and intervention, ed. S. Dimidjian, 380–94. New York: Guilford Publications.

- Berry, T., and M. Candis. 2013. Cultural identity and education: A critical race perspective. Educational Foundations 27, no. 3: 43–64.

- Biggs, J. 2014. Constructive alignment in university teaching. HERDSA Review of Higher Education 1: 5–22.

- Blundell, P., B. Burke, A.-M. Wilson, and B. Jones. 2022. Self as a teaching tool: Exploring power and anti-oppressive practice with counselling/psychotherapy students. Psychotherapy & Politics International 20, no. 3: 1–22. doi:10.24135/ppi.v20i3.03

- Boler, M. 1999. Feeling power: Emotions and education. New York: Routledge.

- Boler, M., and M. Zembylas. 2003. Chapter 5: Discomforting truths: The emotional terrain of understanding differences. In Pedagogies of difference: Rethinking education for social justice, edited by Peter Pericles Trifonas, 110–136. New York: Routledge.

- Bondi, L. 2005. Working the spaces of neoliberal subjectivity: Psychotherapeutic technologies, professionalisation and counselling. Antipode 37, no. 3: 497–514. doi:10.1111/j.0066-4812.2005.00508.x

- Boud, D. 1988. Developing student autonomy in learning. 2nd ed. Abingdon, UK: Taylor & Francis.

- Brantmeier, E.J., and M.K. McKenna. 2020. Pedagogy of vulnerability. Charlotte: Information Age Publishing, Incorporated.

- Braveman, P., E.T. Arkin, D. Proctor, T. Kauh, and N. Holm. 2022. Systemic and structural racism: Definitions, examples, health damages, and approaches to dismantling. Health Affairs 41, no. 2: 171–8. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2021.01394

- Breen, R.L. 2006. A practical guide to focus-group research. Journal of Geography in Higher Education 30, no. 3: 463–75. doi:10.1080/03098260600927575

- Briggs, A.R., J. Clark, and I. Hall. 2012. Building bridges: Understanding student transition to university. Quality in Higher Education 18, no. 1: 3–21. doi:10.1080/13538322.2011.614468

- Bunce, L., A. Baird, and S.E. Jones. 2017. The student-as-consumer approach in higher education and its effects on academic performance. Studies in Higher Education 42, no. 11: 1958–78. doi:10.1080/03075079.2015.1127908

- Bunce, L., N. King, S. Saran, and N. Talib. 2021. Experiences of black and minority ethnic (BME) students in higher education: Applying self-determination theory to understand the BME attainment gap. Studies in Higher Education 46, no. 3: 534–47. doi:10.1080/03075079.2019.1643305

- Burns, D., N. Dagnall, and M. Holt. 2020. Assessing the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on student wellbeing at universities in the United Kingdom: A conceptual analysis. Frontiers in Education 5. doi:10.3389/feduc.2020.582882

- Butler, D.L., and P.H. Winne. 1995. Feedback and self-regulated learning: A theoretical synthesis. Review of Educational Research 65, no. 3: 245–81. doi:10.3102/00346543065003245

- Cabrera, A.F., J.L. Crissman, E.M. Bernal, A. Nora, P.T. Terenzini, and E.T. Pascarella. 2002. Collaborative learning: Its impact on college students’ development and diversity. Journal of College Student Development 43, no. 1: 20–34.

- Cayanus, J.L. 2004. Effective instructional practice: Using teacher self-disclosure as an instructional tool. Communication Teacher 18, no. 1: 6–9. doi:10.1080/1740462032000142095

- Cayanus, J.L., and M.M. Martin. 2008. Teacher self-disclosure: Amount, relevance, and negativity. Communication Quarterly 56, no. 3: 325–41. doi:10.1080/01463370802241492

- Christian, D.D., D.L. McCarty, and C.L. Brown. 2021. Experiential education during the COVID-19 pandemic: A reflective process. Journal of Constructivist Psychology 34, no. 3: 264–77. doi:10.1080/10720537.2020.1813666

- Claxton, G. 2006. Learning to learn – the fourth generation: Making sense of personalised learning. Bristol: TLO Limited.

- Coldridge, L., and P. Mickelborough. 2003. Who’s counting? Access to UK counsellor training: A demographic profile of trainees on four courses. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research 3, no. 1: 72–5. doi:10.1080/14733140312331384668

- Cole, M. 2021. Understanding critical whiteness studies: Harmful or helpful in the struggle for racial equity in the academy? In Doing equity and diversity for success in higher education: Redressing structural inequalities in the academy, eds. D.S.P. Thomas, and J. Arday, 277–98. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Conchar, C., and J. Repper. 2014. “Walking wounded or wounded healer?” Does personal experience of mental health problems help or hinder mental health practice? A review of the literature. Mental Health and Social Inclusion 18, no. 1: 35–44. doi:10.1108/MHSI-02-2014-0003

- Cooper, M. 2023. Psychology at the heart of social change: Developing a progressive vision for society. Bristol, UK: Policy Press.

- Cooper, M., and J. McLeod. 2010. Pluralism: Towards a new paradigm for therapy. Therapy Today 21, no. 9: 10–14.

- Cooper, M., J.C. Norcross, B. Raymond-Barker, and T.P. Hogan. 2019. Psychotherapy preferences of laypersons and mental health professionals: Whose therapy is it? Psychotherapy 56, no. 2: 205–16. doi:10.1037/pst0000226

- Cotton, D., T. Nash, and P. Kneale. 2017. Supporting the retention of non-traditional students in Higher Education using a resilience framework. European Educational Research Journal 16, no. 1: 62–79. doi:10.1177/1474904116652629

- Dee, T., and S. Gershenson. 2017. Unconscious bias in the classroom: Evidence and opportunities, 1–23. Stanford, USA: Institute of Educational Sciences (ERIC). https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED579284

- Derounian, J. 2017. Inspirational teaching in higher education: What does it look, sound and feel like? International Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning 11, no. 1: 9. doi:10.20429/ijsotl.2017.110109

- Elen, J., G. Clarebout, R. Léonard, and J.J. Lowyck. 2007. Student-centred and teacher-centred learning environments: What students think. Teaching in Higher Education 12, no. 1: 105–17. doi:10.1080/13562510601102339

- Etherington, K. 2017. Personal experience and critical reflexivity in counselling and psychotherapy research. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research 17, no. 2: 85–94. doi:10.1002/capr.12080

- Feltham, C. 2010. Critical thinking in counselling and psychotherapy. London: Sage Publications Ltd.

- Fuertes, J.N., and E. Nutt Williams. 2017. Client-focused psychotherapy research. Journal of Counseling Psychology 64, no. 4: 369–75. doi:10.1037/cou0000214

- Galikyan, I., and W. Admiraal. 2019. Students’ engagement in asynchronous online discussion: The relationship between cognitive presence, learner prominence, and academic performance. The Internet and Higher Education 43: 100692. doi:10.1016/j.iheduc.2019.100692

- Gay, G. 2018. Culturally responsive teaching: Theory, research, and practice. 3rd ed. New York: Teachers College Press.

- Henretty, J.R., and H.M. Levitt. 2010. The role of therapist self-disclosure in psychotherapy: A qualitative review. Clinical Psychology Review 30, no. 1: 63–77. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2009.09.004

- Henry, A., and C. Thorsen. 2021. Teachers’ self-disclosures and influences on students’ motivation: A relational perspective. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 24, no. 1: 1–15. doi:10.1080/13670050.2018.1441261

- HESA. 2022. Non-continuation summary: UK Performance Indicators. https://www.hesa.ac.uk/data-and-analysis/performance-indicators/non-continuation-summary.

- Holley, L. C., and S. Steiner. 2005. “Safe Space: Student perspectives on classroom environment.” Journal of Social Work Education 41 (1): 49–64. doi:10.5175/JSWE.2005.200300343

- Hydén, L.C., and P.H. Bülow. 2003. Who’s talking: Drawing conclusions from focus groups—some methodological considerations. International Journal of Social Research Methodology 6, no. 4: 305–21. doi:10.1080/13645570210124865

- Iszatt-White, M., S. Kempster, and B. Carroll. 2017. An educator’s perspective on reflexive pedagogy: Identity undoing and issues of power. Management Learning 48, no. 5: 582–96. doi:10.1177/1350507617718256

- Kelly, U., and R. Kelly. 2020. Becoming vulnerable in the era of climate change: Questions and dilemmas for a pedagogy on vulnerability. In Pedagogy of vulnerability, eds. E. J. Brantmeier, and M. K. McKenna, 177–202. Charlotte: Information Age Publishing, Incorporated.

- Kolb, A.Y., and D.A. Kolb. 2006. Learning styles and learning spaces: A review of the multidisciplinary application of experiential learning theory in higher education. In Learning styles and learning: A key to meeting the accountability demands in education, eds. R. R. Sims, and S. J. Sims, 45–91. New York: Nova Science Publishers.

- Krueger, R.A., and M.A. Casey. 2015. Focus groups: A practical guide for applied research. 5th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Ltd.

- Lipson, S.K., and D. Eisenberg. 2018. Mental health and academic attitudes and expectations in university populations: Results from the healthy minds study. Journal of Mental Health 27, no. 3: 205–13. doi:10.1080/09638237.2017.1417567

- Lochtie, D., E. McIntosh, A. Stork, and B. Walker. 2018. Effective personal tutoring in higher education. Nantwich: Critical Publishing.

- Lomas, L. 2007. Are students customers? Perceptions of academic staff Quality in Higher Education 13, no. 1: 31–44. doi:10.1080/13538320701272714

- Mann, K., J. Gordon, and A. MacLeod. 2009. Reflection and reflective practice in health professions education: A systematic review. Advances in Health Sciences Education 14, no. 4: 595–621. doi:10.1007/s10459-007-9090-2

- McCarthy, J. 2017. Enhancing feedback in higher education: Students’ attitudes towards online and in-class formative assessment feedback models. Active Learning in Higher Education 18, no. 2: 127–41. doi:10.1177/1469787417707615

- McDonnell, L., P. Stratton, S. Butler, and N. Cape. 2012. Developing research-informed practitioners – an organisational perspective. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research 12, no. 3: 167–77. doi:10.1080/14733145.2012.682594

- McLeod, J. 2000. The contribution of qualitative research to evidence-based counselling and psychotherapy. In Evidence based counselling and psychological therapies: Research and applications, eds. N. Rowland, and S. Goss, 111–26. London: Routledge.

- McLeod, J., and J. McLeod. 2014. Personal and professional development for counsellors, psychotherapists and mental health practitioners. Maidenhead: McGraw-Hill Education (UK).

- Meyers, S., K. Rowell, M. Wells, and B.C. Smith. 2019. Teacher empathy: A model of empathy for teaching for student success. College Teaching 67, no. 3: 160–8. doi:10.1080/87567555.2019.1579699

- Mezirow, J. 1997. Transformative learning: Theory to practice. New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education 1997, no. 74: 5–12. doi:10.1002/ace.7401

- Miller, J.P., K. Nigh, M.J. Binder, B. Novak, and S. Crowell. 2018. International handbook of holistic education. 1st ed. New York: Routledge.

- Morley, L. 2003. Quality and power in higher education. Maidenhead, UK: McGraw-Hill Education.

- Murphy, D. 2011. Unprecedented times in the professionalisation and state regulation of counselling and psychotherapy: The role of the Higher Education Institute. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling 39, no. 3: 227–37. doi:10.1080/03069885.2011.552601

- Nicol, D.J., and D. Macfarlane-Dick. 2006. Formative assessment and self-regulated learning: A model and seven principles of good feedback practice. Studies in Higher Education 31, no. 2: 199–218. doi:10.1080/03075070600572090

- Petrie, K., and N. Keohane. 2017. On course for success? Student retention at university. London: Social Market Foundation.

- Powell, R.A., C. Njoku, R. Elangovan, G. Sathyamoorthy, J. Ocloo, S. Thayil, and M. Rao. 2022. Tackling racism in UK health research. BMJ 376. doi:10.1136/bmj-2021-065574

- Race, P. 2019. The lecturer’s toolkit: A practical guide to assessment, learning and teaching. 5th ed. London: Routledge.

- Ritchie, J., J. Lewis, G. Elam, R. Tennant, and N. Rahim. 2014. Chapter 5: designing and selecting samples. In Qualitative research practice: A guide for social science students and researchers. 2nd ed., eds. J. Ritchie, and J. Lewis, 111–46. London: SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Rogers, C. 1961. On becoming a person: A therapist’s view of psychotherapy. Boston, New York: Houghton Mifflin Company.

- Schön, D.A. 1983. The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. New York: Basic Books.

- Schön, D.A. 1987. Educating the reflective practitioner: Toward a new design for teaching and learning in the professions. San Francisco, CA: Wiley.

- Starr, P. 1982. The social transformation of American medicine: The rise of a sovereign profession and the making of a vast industry. London, UK: Hachette UK.

- Stork, A., and B. Walker. 2015. Becoming an outstanding personal tutor: Supporting learners through personal tutoring and coaching. Nantwich: Critical Publishing.

- Symonds, E. 2021. Reframing power relationships between undergraduates and academics in the current university climate. British Journal of Sociology of Education 42, no. 1: 127–42. doi:10.1080/01425692.2020.1861929

- Tan, C., D. Casanova, I. Huet, and M. Alhammad. 2022. Online collaborative learning using microsoft teams in higher education amid COVID-19. International Journal of Mobile and Blended Learning 14, no. 1: 1–18. doi:10.4018/IJMBL.297976

- Tilley, E., J. McLeod, and J. McLeod. 2015. An exploratory qualitative study of values issues associated with training and practice in pluralistic counselling. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research 15, no. 3: 180–7. doi:10.1002/capr.12033

- Tilley, S., and L. Taylor. 2013. Understanding curriculum as lived: Teaching for social justice and equity goals. Race Ethnicity and Education 16, no. 3: 406–29. doi:10.1080/13613324.2011.645565

- Tribe, R., and J. Morrissey. 2020. The handbook of professional ethical and research practice for psychologists, counsellors, psychotherapists and psychiatrists. 3rd ed. Hove, UK: Taylor & Francis Group.

- Truta, C., L. Parv, and I. Topala. 2018. Academic engagement and intention to drop out: Levers for sustainability in higher education. Sustainability 10, no. 12: 4637. doi:10.3390/su10124637

- Tsai, Y.-S., C. Perrotta, and D. Gašević. 2020. Empowering learners with personalised learning approaches? Agency, equity and transparency in the context of learning analytics. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 45, no. 4: 554–67. doi:10.1080/02602938.2019.1676396

- UEL. 2020. The University of East London access and participation plan: 2020 to 2025. London, UK: University of East London.

- Vetere, A., and P. Stratton. 2016. Interacting selves: Systemic solutions for personal and professional development in counselling and psychotherapy. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.

- Watkins, C.E., and D.K. Mosher. 2020. Psychotherapy trainee humility and its impact: Conceptual and practical considerations. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy 50, no. 3: 187–95. doi:10.1007/s10879-020-09454-8

- Watt, D. 2007. On becoming a qualitative researcher: The value of reflexivity. Qualitative Report 12, no. 1: 82–101. doi:10.46743/2160-3715/2007.1645

- White, M. 2007. Maps of narrative practice. London: W.W. Norton & Company.

- Wibeck, V., M.A. Dahlgren, and G. Öberg. 2007. Learning in focus groups: An analytical dimension for enhancing focus group research. Qualitative Research 7, no. 2: 249–67. doi:10.1177/1468794107076023

- Wilcox, P., S. Winn, and M. Fyvie-Gauld. 2005. ‘It was nothing to do with the university, it was just the people’: The role of social support in the first-year experience of higher education. Studies in Higher Education 30, no. 6: 707–22. doi:10.1080/03075070500340036

- Winlow, H., D. Simm, A. Marvell, and R. Schaaf. 2013. Using focus group research to support teaching and learning. Journal of Geography in Higher Education 37, no. 2: 292–303. doi:10.1080/03098265.2012.696595

- Wosket, V. 2016. The therapeutic use of self: Counselling practice, research and supervision. London: Routledge.

- Zerubavel, N., and M. O’Dougherty Wright. 2012. The dilemma of the wounded healer. Psychotherapy 49, no. 4: 482–91. doi:10.1037/a0027824

- Zimmermann, M., C. Bledsoe, and A. Papa. 2021. Initial impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on college student mental health: A longitudinal examination of risk and protective factors. Psychiatry Research 305. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2021.114254