ABSTRACT

This paper examines how students’ employability develops during undergraduate studies at a Dutch liberal arts college compared to a conventional bachelor’s programme in law at the same university. Drawing on the graduate capital model, the study focuses on six skills that enhance employability: creativity, lifelong learning, career decidedness, self-efficacy, resilience, and personal initiative. To measure employability growth, a cross-sectional pseudo-cohort research design is adopted, comparing first-, second-, and third-year student cohorts. The results show that liberal arts students make significant progress in five out of the six examined employability-related skills. Compared to the conventional programme, the gains in creativity and personal initiative particularly stand out, reflecting the differences between interdisciplinary and monodisciplinary learning, and self-tailored and fixed curriculum structures. This refutes the stereotype that a liberal arts degree does not prepare students for the labour market and points to the relevance of programme-specific features for employability development in higher education.

1. Introduction

The changing nature of work and employment in the twenty-first century is imposing new challenges on higher education institutions (HEIs). In light of the widespread labour market uncertainty and expansion of higher education (HE), the topic of graduate employability has become a central concern shared by universities, students, employers, governments, and society at large (Tomlinson Citation2012). While the expectation placed on universities to produce employable graduates may be ubiquitous, the understanding of the role played by different pedagogies and HE features in this process is still limited (Humburg and van der Velden Citation2017).

HE systems and institutions have developed different responses to the growing demands for improving graduate employability. In some countries, this resulted in increasing curricular specialisation and a greater emphasis on professional skillsFootnote1, internships and work placements; in others, it lead to the incorporation of general skills such as communication, problem solving, IT literacy, entrepreneurship, as well as labour market training, into university programmes (Clarke Citation2018; Teichler Citation2013).

In the European context, a novel approach concerns the resurgence of liberal arts education (LAE), a model for general undergraduate studies most commonly associated with the United States. The reintroduction of LAE has been particularly pronounced in the Netherlands, where ten university colleges have been established since the late 1990s. Developed as internationally oriented, publicly funded institutions offering three-year liberal arts and science bachelor’s degrees, Dutch university colleges represent an exception from conventional university programmes (van der Wende Citation2011). In broad terms, this distinctiveness concerns the fact that university colleges provide a general academic education rather than aiming to prepare students for a specific profession. More explicitly, the distinctive nature of university colleges stems from several shared principles related to their self-tailored, interdisciplinary curricula, student-centred pedagogy, and selective admission.

The most prominent feature of LAE programmes is the open curriculum, which includes three key aspects: curricular breadth, interdisciplinarity, and freedom of choice. Unlike most conventional undergraduate programmes, which are narrow and monodisciplinary, university colleges have a broad, radically open curriculum that promotes interdisciplinary learning through a diverse range of subjects spanning the humanities, social sciences, and natural sciences. Moreover, LAE programmes are based on students’ freedom of choice, allowing them to build a self-tailored academic profile. Another salient feature of university colleges is related to their distinctive pedagogy that emphasises small-scale and intensive education. The student-teacher ratio is low, allowing for a more interactive learning experience compared to conventional programmes, which often lack individual attention due to large class sizes. Finally, what distinguishes Dutch university colleges from other bachelor’s programmes also concerns their selective admission, which includes the assessment of the candidates’ prior academic performance and personal motivation (Cooper Citation2018; Dekker Citation2017; UCDN Citation2017).

Dutch university colleges have been lauded for their commitment to academic excellence, but also criticised for the alleged impracticality of their degrees. While the proponents of LAE stress its ability to provide an optimal response to the demands associated with the contemporary workplace, little is known as to how the distinctive characteristics of LAE programmes relate to enhancing their students’ employability. The current paper addresses this research gap. Its main goal is twofold. Firstly, it seeks to propose an alternative, developmental approach to assessing the contribution of undergraduate programmes to fostering employability. Secondly, it aims to determine how a university college performs in this regard compared to a conventional bachelor’s programme. It does so by applying the graduate capital model, a well-established employability framework proposed by Michael Tomlinson (Citation2017), and using it to answer the following research question: How does employability develop in university college students during the course of their studies compared to their peers from a conventional programme? It shows that attending a LAE undergraduate programme leads to visible progression in a range of career-relevant skills.

The paper proceeds as follows. Section 2 discusses the concept of employability and the drawbacks of using employment outcomes to evaluate its development in HE. Section 3 introduces the adapted graduate capital framework for assessing employability gains from HE. It explains the employability components and skills included in the study and hypothesises the impact of LAE on their development. Section 4 presents the method and data used in the empirical analysis, the results of which are reported in Section 5. Section 6 discusses the findings and concludes the paper.

2. Employability and higher education: the problem of employment-based measures

The most widely used definition of employability is that proposed by Yorke (Citation2006, 8), who described it as ‘a set of achievements—skills, understandings and personal attributes—that makes graduates more likely to gain employment and be successful in their chosen occupations’. Given the variety of definitions in circulation, which often confuse employability with employment, it is important to distinguish between the two terms. In this regard, it should be stressed that employability is not an empirical, but rather a relational concept (Holmes Citation2017, 362–63). As such, it can only be measured indirectly. Most commonly, this involves using employment outcomes such as labour force status and income as valid, empirically observable indicators of employability. Despite being connected, however, employability and employment are not interchangeable concepts, as the former denotes the capacity to perform a job, while the latter implies its actual acquisition, which is determined not only by individual skills, but also by supply and demand dynamics of the labour market, as well as discriminatory practices in recruitment related to age, ethnicity, gender, and social class. In other words, employability is a necessary but insufficient condition for gaining employment (Yorke Citation2006; Wilton Citation2011; Harvey Citation2001).

In the HE context, the overreliance on employment-based indicators leads to a problem of having an unclear understanding of what universities produce in terms of employability and work-readiness of their graduates. Approaches relying on post-graduation employment statistics as measures of employability development evaluate universities based on outcomes that are beyond their control (Harvey Citation2001). Thereby, such indicators and rankings also fail to account for the role of distinct pedagogies and HE features, leading to a situation where the actual contribution of HEIs to employability remains a ‘black box’ (Teichler Citation2013). This is even more problematic at the undergraduate level, given the fact that an increasing proportion of graduates complete a master’s degree before entering the labour market.

Hence, if the goal is to look at the contribution of HEIs to employability, a different approach is required. As Lawton (Citation2019, 55) notes, the assessment of teaching quality and employability gains from HE should be based upon ‘what goes on in the classroom’ and whether students make good progress and develop relevant skills. The approach adopted in this paper intends to achieve exactly this, measuring the extent to which students from two different types of undergraduate programmes have developed important skills that enhance employability. Yet, this opens another complex question: which skills are the most relevant determinants of employability? This issue is addressed in the following section, which sets out a framework for assessing the employability contribution of HEIs.

3. Assessing employability gains from higher education: the developmental approach

The literature on employability is marked by a lack of consensus on what it entails, particularly with regard to the skills that HEIs should provide. Owing to the multiplicity of perspectives from which employability can be approached and the various dimensions it encompasses, multiple theoretical frameworks and models have been developed. The most widely used and empirically supported employability frameworks are built around the notion of ‘capital’ or ‘resources’. Fugate, Kinicki, and Ashforth (Citation2004) defined employability as a person-centred construct encompassing three dimensions: social and human capital, career identity, and personal adaptability. Hirschi’s (Citation2012) career resources model includes nearly identical elements: human capital, social, psychological, and identity resources. Drawing on these frameworks, Tomlinson (Citation2017) developed a model comprising five forms of ‘graduate capital’—human, social, cultural, identity, and psychological capital—each consisting of resources acquired through HE that can be utilised in the labour market.

This paper builds on Tomlinson’s (Citation2017) graduate capital model, adapting it to fit the study’s purpose. This model has been chosen for two main reasons. Firstly, it is one of the few employability frameworks that refers specifically to the HE context. Secondly, although this model has not yet been applied in quantitative studies, it is largely based on the work of Fugate, Kinicki, and Ashforth (Citation2004), which has received considerable empirical verification (see, for example, McArdle et al. (Citation2007)).

While the graduate capital model provides a useful conceptual framework for understanding employability in the HE context, its practical application bears several difficulties. A major obstacle stems from taxonomic fuzziness. By and large, the framework is imprecise when it comes to identifying the elements included in each category. A further problem concerns the overlooked effect of different educational models. The framework provides a conception of what constitutes graduate employability, but it does not consider the role various HE features and pedagogies can play in helping students to develop it. To overcome these issues, the graduate capital model has been adjusted by means of excluding certain aspects, along with specifying the factors that each of the capital dimensions entails. This has been done to ensure that the framework is compatible with the study’s purpose and coherent enough for quantitative empirical analysis. The framework adjustment has been guided by four main considerations.

Firstly, if employability is analysed as an outcome of higher education, the focus should be on graduate skills that can be attained or strengthened through university studies. This implies the exclusion of fixed traits and constructs that cannot be further developed. Furthermore, universities may not be the most appropriate place to develop certain skills. For example, entrepreneurial skills might be more efficiently acquired through work experience or employment-based training (Humburg and van der Velden Citation2017).

With this in mind, secondly, particular attention should be placed on the role of the HE learning environment. As Knight and Yorke (Citation2003) pointed out, employability development is rooted in good student learning, which is bound up with the entire educational environment. For this reason, employability should be viewed as being integral to whole undergraduate programmes and institutions, rather than an additive that is provided by means of various modules and one-off trainings.

The emphasis on learning environments leads to the third point, which concerns the specificities of LAE. If ‘the student learning that makes for strong claims to employability comes from years, not semesters; through programmes, not modules; and in environments, not classes’ (Knight and Yorke Citation2003, 4), the analysis should concentrate on employability factors reflecting the distinctive features of different university programmes. Within the many employability constituents developed through HE, this study is particularly interested in the ones that are most profoundly related to the curriculum and learning environment of LAE.

As a final point, the inclusion of factors is also based on practical choices related to measurability and comparability.

The adaptation of the graduate capital model is discussed in the following subsection. It examines the three forms of graduate capital included in the study, defines the individual factors comprising them, and theorises how LAE contributes to their development.

3.1. The employability contribution of LAE: adapting the graduate capital framework

The graduate capital model includes five dimensions: human, social, cultural, identity, and psychological capital. These are defined as ‘key resources that confer benefits and advantages onto graduates’ (Tomlinson Citation2017, 339). Two of these aspects—social and cultural capital—will be excluded from the analysis because, although being relevant for employability, social and cultural capital are rather difficult to measure and compare. Additionally, the COVID-19 pandemic has reduced the university experience to online classes, considerably limiting opportunities for growth in these areas. Hence, this subsection focuses on the three other dimensions—human capital, identity capital, and psychological capital—and the more specific elements they entail.

3.1.1. Human capital: creativity and lifelong learning

According to human capital theory (Becker Citation1964), there is a direct link between the skills people acquire through education and their subsequent job productivity and labour market outcomes. In Tomlinson’s (Citation2017) framework, the human capital component of employability pertains to the skills that graduates obtain during the course of their studies. This includes both specialised, subject-specific skills, and ones that are of a more general or transferable nature.

The category of generic skills appears in nearly all employability models as a major component of human capital. As the graduate capital model does not include a list of generic skills, in this study, they are referred to in line with Binkley et al.’s (Citation2012) classificationFootnote2, focusing on two skills from the ‘ways of thinking’ category: creativity and lifelong learning. Creativity is understood as divergent thinking—a form of creative cognition that produces new and original ideas (Runco Citation2011), while lifelong learning denotes an individual’s ability and readiness to deliberately engage in learning over the longer term (Knapper and Cropley Citation2000). The selection of these skills is based on the expected impact of LAE on their development and the availability of viable measures.

The cultivation of creativity is commonly ascribed to LAE, largely on the grounds of its interdisciplinary character and the students’ associated ability to approach problems from multiple perspectives (Dekker Citation2017; van Damme Citation2016). The link between LAE and lifelong learning is also frequently stressed. Both the theoretical and empirical literature suggest that the teaching practices and intellectual climate of LAE institutions greatly support the development of attitudes and abilities associated with lifelong learning (Seifert et al. Citation2008; Jessup-Anger Citation2012; Kovačević Citation2022). Active, student-centred pedagogies were found to be linked to the development of creativity and lifelong learning-related skills, as well as a range of other generic, higher-order thinking skills. Likewise, traditional forms of university teaching, such as lecturing, were shown to inhibit the learning of creativity (Virtanen and Tynjälä Citation2019; Kember, Leung, and Ma Citation2007).

The second component of human capital concerns specialist, subject-specific skills. Although subject-specific skills constitute an essential aspect of employability, they will not be considered in the current analysis, as they do not contribute to a useful comparison of skill development in two different fields of study.

3.1.2. Identity capital: career decidedness

Tomlinson (Citation2017) defines identity capital as a graduate’s capacity to develop an emerging career identity and shape it into a cohesive professional narrative. Given our focus on undergraduate students whose identities are still in formation, this paper will analyse identity capital through the closely related concept of career decidedness. According to Fearon et al. (Citation2018, 269), career decidedness refers to ‘the extent to which students are certain about intended career paths they would like to pursue and develop after leaving university’. As noted by Tomlinson (Citation2017), identity capital is strongly influenced by the HE learning environment. As such, professional identity development is an area where the differences between general and specialised programmes, as well as fixed and flexible curricula, can strongly come into play (Trede, Macklin, and Bridges Citation2012).

Regarding both aspects, the LAE open curriculum bears important consequences for the development of career decidedness. On the one hand, curricular breadth and freedom of choice can be seen as useful vehicles for fostering career decidedness, allowing students to try different courses before determining what subjects match their interests and future goals (Dekker Citation2021). On the other hand, it has also been pointed out that forming a strong career identity is more challenging in programmes that do not prepare students for a particular profession (Lairio, Puukari, and Kouvo Citation2013).

3.1.3. Psychological capital: the capacity to deal with change

Tomlinson’s (Citation2017) conception of psychological capital relates to the graduates’ capacity for navigating a changing job market, withstanding career setbacks, and dealing with job pressures and other employment-related challenges. It includes two main psychological resources: proactive career adaptability and resilience. The author also stresses the role of self-efficacy and locus of control but doesn’t provide a clear-cut classification. To avoid confusion with cognitive skills caused by the broad connotation of the term, this study will consider psychological capital as the capacity to deal with change, encompassing the following non-cognitive skills:

Self-efficacy, which refers to ‘beliefs in one’s capabilities to organise and execute the courses of action required to manage prospective situations’ (Bandura Citation1995, 2);

Resilience, which is generally defined as ‘the capacity to rebound or bounce back from adversity, conflict, failure, or even positive events, progress, and increased responsibility’ (Luthans, Youssef-Morgan, and Avolio Citation2015, 144–45);

Personal initiative, a work behaviour that is ‘characterised by its self-starting nature, its proactive approach, and by being persistent in overcoming difficulties that arise in the pursuit of a goal’ (Frese and Fay Citation2001, 134).

Considering current economic uncertainties and unpredictable university-to-work transition, HEIs should be able to foster the development of these psychological resources, or at least raise awareness of their importance (Tomlinson Citation2017). As noted by Kautz et al. (Citation2014), such non-cognitive skills are equally strong predictors of later-life outcomes as measures of cognition. Most importantly, these capacities are not fixed traits determined solely by genes, but abilities that can be learned and improved. In fact, compared to cognitive skills, ‘non-cognitive skills are more malleable at later ages’ (Kautz et al. Citation2014, 2). In that respect, research has shown that self-efficacy, resilience, and personal initiative can be developed in HE (van Dinther, Dochy, and Segers Citation2011; Tymon and Batistic Citation2016; Holdsworth, Turner, and Scott-Young Citation2018).

The inherent self-directedness of LAE can be seen as highly relevant to the development of their students’ self-efficacy, resilience, and proactive behaviour. In contrast to conventional undergraduate programmes, which are tightly structured, at a university college, students (with the help of academic advisors) are responsible for organising and structuring their own educational path. Hence, a self-tailored curriculum requires constant self-awareness (Claus, Meckel, and Pätz Citation2018), enabling LAE students to develop a strong sense of initiative and self-responsibility. The same can be said of the active pedagogy that involves intense learning in small groups and diverse assessment methods, requiring students to continuously read, discuss, write, problem-solve, and collaborate. In other words, the demanding nature of the programme presupposes a capacity to cope with difficulties and accomplish diverse academic tasks set at high standards.

An overview of the adjusted graduate capital model is shown in . This framework will be applied in the empirical analysis to assess the employability gains of LAE undergraduates and compare them to those of their peers in a conventional, subject-specific bachelor’s programme. In view of the preceding theoretical discussion, several basic assumptions can be made to guide the analysis.

Table 1. Measuring employability gains through the adapted graduate capital framework.

With regard to human and psychological capital, it can be expected that LAE students experience significant growth as they progress through their studies. Given that these employability constituents are closely related to LAE, one can also assume that the gains of LAE students would be greater than or comparable to those of their peers from a conventional programme. Finally, due to the selectiveness of university colleges, it can be expected that LAE students enter university with a higher level of most skills, with the exception of career decidedness. As being unsure about a career path is one of the main reasons for enrolling in a LAE programme, it is expected that first-year LAE students will be less decided than their counterparts attending a subject-specific programme. The following sections test these general assumptions.

4. Method

In line with Hoareau McGrath et al. (Citation2015), employability growth is considered from the perspective of ‘distance travelled’, or the difference in the level of skills identified over a period of time. As an alternative to monitoring a single cohort of students at two timepoints, this study follows Flowers et al. (Citation2001) in using a cross-sectional pseudo-cohort research design, simultaneously looking at multiple cohorts in different years of their study. More precisely, employability development is assessed by comparing first-, second-, and third-year cohorts at a LAE programme and a conventional undergraduate programme. The major advantage of this approach is that it accounts for differential selection into programmes, as it focuses on the development of skills across year groups within each programme. This basically resembles a Difference-in-Difference (DiD) approach, accounting for unobserved heterogeneity. However, it assumes that the characteristics of the year cohorts do not change over time.

4.1. Data collection

Data was collected from students enrolled in two undergraduate programmes at a Dutch research university: a LAE bachelor, and a bachelor in EU and international law (henceforth referred to as Law). The Law programme was chosen as a reference group to ensure comparability in terms of student profiles and programme characteristics. Both programmes have a broad scope, an international orientation, and are taught in English. Since all study programmes at the given university employ problem-based learning, there is also a high degree of similarity with regard to educational methods, although the LAE programme has more contact hours and teaching is generally conducted in smaller groups.

There are three key differences between the programmes. The first relates to the structure of their curricula—specifically, the degree of freedom in choosing and combining courses. The LAE programme has an open curriculum. Its mandatory, ‘core’ component and bachelor’s thesis account for 50 ECTS credits, while 130 credits are earned through electives. Students can choose from over 150 courses, projects, and skills trainings, which can be combined in countless ways. As a result, no two students follow the exact same trajectory. On the other hand, the Law programme has a more fixed curriculum, consisting of 120 credits of compulsory courses and 60 credits in electives. Thus, Law students have fewer choices to make with respect to course selection and combination. The second crucial difference between the programmes is related to what they teach, or the content of their curricula. While the Law programme is monodisciplinary, with a focus on legal studies, the LAE programme is highly interdisciplinary, offering courses across a wide range of fields and requiring students to take courses outside of their major. Hence, while the two programmes are fairly similar in terms of teaching methods (both use problem-based learning), what they teach is substantially different. Finally, the programmes also differ in their admission criteria: Law has a non-selective admission policy, while the LAE programme has a selective admission process.

Students were asked to take an online survey lasting approximately 20 minutes. Participants were recruited through flyers, student portal announcements, social media posts, and during tutorials and lectures. Incentives for participation included a personal feedback report and a charity donation of €200 for every 100 responses from a study year. Prior to taking the survey, participants were presented with an informed consent statement and freely gave their consent. The survey ran between September 20 and December 19, 2021.

Following the removal of incomplete and duplicate responses, ineligible participants from other programmes, students over the age of 30, and those who were in their eighth semester or higher, a total of 558 responses were included in the final sample. 308 respondents were LAE students and 250 were studying Law, respectively accounting for approximately 39% and 23% of the total number of students enrolled in these two programmes. At the time of the survey, most participants were in the first semester of their first, second, or third year. A few respondents, who started their studies in February, were in their second, fourth, and sixth semester. Some third-year students were in their seventh semester. A full overview of study respondents is provided in .

Table 2. Study sample per programme, semester, and study year.

4.2. Measures

Guilford’s (Citation1967) Alternate Uses Task (AUT) was used to assess creativity. The AUT measures divergent thinking ability by asking participants to list as many different possible uses for an everyday object within a fixed amount of time. The objects used in this study were a newspaper and an umbrella. The allotted time was 2 minutes per object. The AUT was scored based on fluency—the number of acceptable uses. Grading was conducted by the first author.

Lifelong learning was assessed using Wielkiewicz and Meuwissen’s (Citation2014) Lifelong Learning Scale (WielkLLS). The WielkLLS measures an individual’s tendency to engage in behaviours and activities related to lifelong learning. It comprises 16 items rated on a 5-point scale. Cronbach’s alpha in this study was 0.88.

Career decidedness was measured on a scale developed by Lounsbury, Hutchens, and Loveland (Citation2005). The scale has 6 items with responses made on a 5-point Likert scale. Alpha was 0.84.

Self-efficacy was assessed via the General Self-Efficacy Scale (Schwarzer and Jerusalem Citation1995). It contains 10 items rated on a 4-point Likert-type scale. Alpha was 0.82.

The brief resilience scale (BRS) was used to measure resilience. This unidimensional scale was created by Smith et al. (Citation2008) for assessing the general ability to bounce back or recover from stress. It consists of 6 items rated on a 5-point Likert scale. Alpha was 0.78. As suggested by Fisher and Law (Citation2021), outcome-focused measures of resilience are best suited for developmental evaluation purposes.

Personal initiative was measured using the situational judgement test (SJT-PI) developed by Bledow and Frese (Citation2009). Instead of the original 12-item test, this study used a shorter version with 6 items, which were selected to best fit the research context (test items 1, 4, 6, 8, 9, and 12 were included). The SJT-PI presents respondents with work-related scenarios, asking them to choose the response options they would be most and least likely to perform. Each response is graded as +1, 0 or −1, with each question’s score ranging from −2 to +2. As noted by the SJT-PI authors, Cronbach’s alpha is not an appropriate reliability measure for this kind of test, and high internal consistency is not to be expected. However, past research has established satisfactory test-retest reliability of the SJT-PI (Bledow and Frese Citation2009).

These six employability constituents were used as the dependent variables of this study. AUT fluency was measured as the total number of acceptable uses across both objects. Scores in lifelong learning, career decidedness, self-efficacy, resilience, and personal initiative were calculated as the mean of items comprising each measure. The study programme (1 = LAE; 0 = Law) and study year served as the main independent variables.

In order to account for possible compositional differences between the cohorts, several controls for student background characteristics have been collected. These control variables include:

age;

gender (1 = male; 0 = female and other);

type of secondary education (1 = academic; 0 = non-academic general or vocational/technical);

high school GPA ranking compared to other students in graduating class (on a 5-point scale, ranging from 1 = much lower than the average to 5 = much higher than the average);

gap year after high school (1 = yes; 0 = no);

first-generation university student (1 = yes; 0 = no);

non-study-related work experience before higher education (1 = one month or more; 0 = less than one month);

non-study-related work experience during higher education (1 = one month or more; 0 = less than one month);

country (group) of high school graduation.

A detailed overview of descriptive statistics is presented in Table S1 in the supplementary material.

4.3. Analysis

Following the theoretical arguments, the primary goal of the analysis was to assess the employability development of LAE students and compare it to that of their peers in the Law programme. To do so, the study employed a DiD approach, looking at the differences in the development students make within a programme.

Six OLS regression models were estimated—one for each dependent variable. All analyses were conducted in Stata 17, using the command regress with robust standard errors. To determine whether the scores significantly differ between first-, second-, and third-year cohorts in each of the programmes, an interaction term was included between the study year and study programme variables. This interaction term was then dissected by using the margins and contrast commands.

5. Results

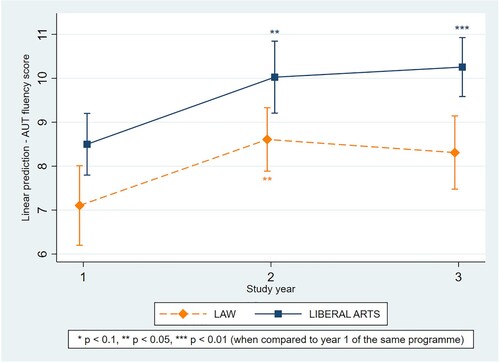

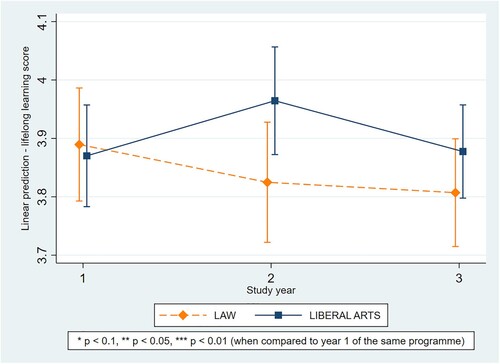

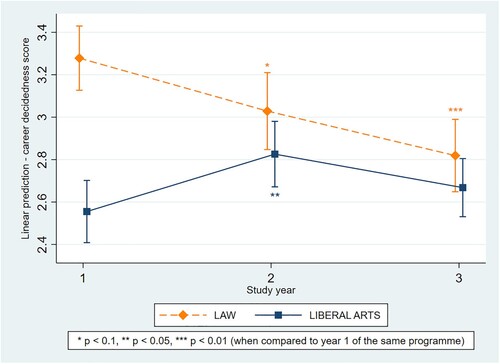

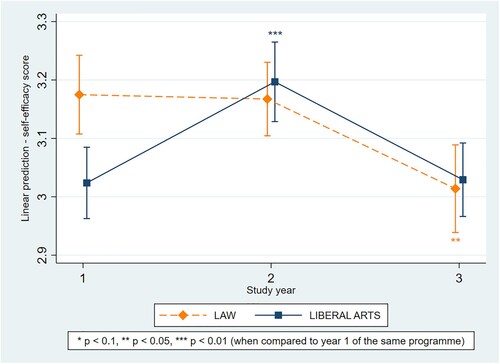

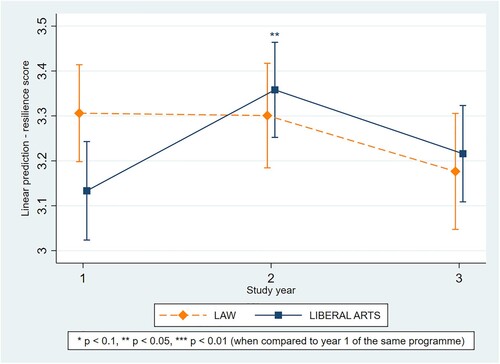

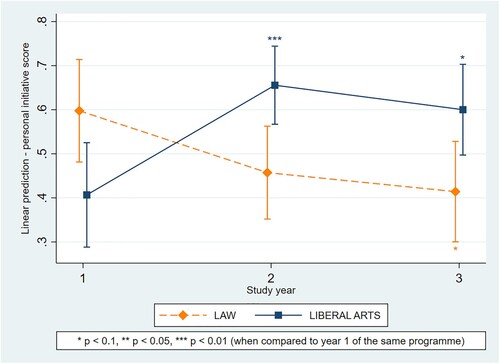

The full regression results are presented in Table S2. illustrates how second- and third-year cohorts compare to the base category of first-year students in the LAE and Law programmes. The comparisons are visualised by means of marginsplot graphs, which show the adjusted means of outcome variables by study programme and study year with 90% confidence intervals. The asterisks in the graphs indicate statistically significant differences as presented in (i.e. comparing second- and third-years’ scores to year one within the same programme).

Table 3. Simple effects of the second and third year (vs first year) by study programme.

5.1. Creativity

AUT fluency scores are presented in . Compared to freshmen, second- and third-year LAE students were able to generate a significantly higher number of acceptable answers. Second- and third-year Law students also provided more acceptable answers than freshmen. However, the effect of being a third-year versus a first-year Law student proved statistically insignificant at the 10% level. Overall, all three LAE cohorts achieved higher scores.

5.2. Lifelong learning

As shown in , the effects of study programme and study year on lifelong learning scores were found statistically insignificant in all cases. When it comes to lifelong learning, in other words, the scores of first-, second-, and third-year LAE and Law cohorts do not significantly differ.

5.3. Career decidedness

Career decidedness scores (illustrated in ) reveal very different patterns in LAE and Law cohorts. Although first-year Law students showed considerably higher levels of decidedness than their LAE counterparts, a continuous decline in scores is visible in the second-year and third-year cohorts. LAE students have a lower starting point, but follow an upward trajectory, displaying significantly higher scores in year two, then somewhat slipping back in year three to a level that is higher yet statistically insignificant compared to year one.

5.4. Self-efficacy

As can be seen from , the major difference in self-efficacy scores pertains to the significantly higher starting point of Law students. The scores of second-year and third-year cohorts were quite similar across programmes. In comparison with their respective first-year cohorts, however, second-year LAE students scored significantly higher, while third-year Law students achieved significantly lower scores. In the case of second-year Law and third-year LAE cohorts, the differences in scores were statistically insignificant.

5.5. Resilience

Resilience scores (illustrated in ) show patterns that are similar to those of self-efficacy. The scores of second- and third-year LAE students were higher than those of freshmen, but the difference was found statistically significant only in year two. Law freshmen scored higher than their LAE peers, but there were no statistically significant differences in scores between first-, second-, and third-year Law students.

5.6. Personal initiative

Personal initiative scores are shown in . While LAE freshmen scored lower than their Law counterparts, second- and third-year LAE cohorts showed higher levels of personal initiative. Second-year and third-year LAE students both scored significantly higher than freshmen. In the Law programme, on the other hand, second- and third-year cohorts achieved lower scores than freshmen.

6. Discussion and conclusion

The empirical analysis revealed several important findings regarding the effectiveness of LAE in fostering employability development. Firstly, the results suggest that LAE students make notable progress in a range of employability-relevant skills. This is especially the case with regard to creativity and personal initiative, in which second- and third-year LAE students both scored significantly higher than freshmen. As for career decidedness, self-efficacy, and resilience, significant gains were found for second-year LAE cohorts. Lifelong learning scores revealed no significant differences between the three study years. Still, considering the overall high average scores in lifelong learning, it may well be that the students already entered university with a strongly positive attitude towards learning, maintaining this mindset over the course of their studies.

Secondly, the comparison between the two programmes points to the relevance of LAE-specific features for the development of certain skills. Most notably, this concerns the greater creativity and personal initiative gains of LAE students, which seem to be stemming from the two most distinctive characteristics of LAE. With regard to fostering creativity, the profoundly interdisciplinary character of LAE and the students’ associated ability to approach problems from a plurality of perspectives might have played a crucial role. Likewise, the higher growth in personal initiative can be seen as resulting from the LAE open curriculum, which pushes the students to be proactive and take charge of their own educational journey. Hence, it can be inferred that the discrepancy in creativity and personal initiative gains of LAE and Law students reflects the differences between interdisciplinary and monodisciplinary learning, as well as self-tailored and fixed curriculum structures.

The opposite seems to be true for self-efficacy and resilience. The highly similar scores of second- and third-year LAE and Law students in these skills suggest that their development is not unique to LAE, in the sense that it does not stem from the open curriculum and interdisciplinary learning. Still, this might also mean that self-efficacy and resilience are more related to LAE features that are shared by Law, such as the student-centred pedagogical approach and demanding workload.

Another notable difference revealed by the comparison concerns the opposite career decidedness trajectories of Law and LAE students. It appears that Law students experience a considerable decline in career decidedness, possibly because their initial perception of the study field changes over time, leading to doubts about what kind of career they wish to pursue. On the other hand, the increasing career decidedness of LAE students can be interpreted as resulting from the open curriculum, which gives students the possibility to explore a broad spectrum of academic disciplines before deciding what they want to focus on. In that respect, this study has shown that curricular freedom of choice can be useful in facilitating the formation and development of career identity.

One concern might be whether the findings truly reflect the different characteristics of the two programmes, rather than their disparate student populations. However, by using the DiD design, the analysis mainly focused on differential skill development within both groups, thus effectively controlling for unobserved heterogeneity. Moreover, one can see that the groups are rather similar in terms of student composition, and comparability was further enhanced by controlling for observed student characteristics. Thus, the DiD design strongly suggests that the differences in skill gains between LAE and Law students are determined by programme-specific features.

Two of the findings were surprising. Firstly, one may wonder why third-year students slipped back in some of the skills, scoring lower than second-year cohorts. As to career decidedness, self-efficacy, and resilience, this setback was evident in both groups. While nonlinear skill development is not unusual (Arts, Gijselaers, and Boshuizen Citation2006), in this particular case, the observed setback may have to do with the subjective measurement of non-cognitive skills and their dependence on situational factors. For example, one’s self-efficacy beliefs are known to decrease in the presence of negative feelings such as anxiety (van Dinther, Dochy, and Segers Citation2011). In that sense, the beginning of the third year is a period that confronts students with new challenges and important decisions about their future, introducing more uncertainty into their lives, which may have lowered their perception of career decidedness, self-efficacy, and resilience.

Secondly, the comparatively lower scores of LAE freshmen in self-efficacy, resilience, and personal initiative contradicted the expectation that they would start off at a higher level as a result of the selection process. While surprising, this does not necessarily imply that selectivity did not affect the first-years students’ scores in these non-cognitive skills; rather, it could be that it manifested itself differently than anticipated. When students are asked to self-assess their skills, their evaluation can be influenced by the group to which they compare themselves. This is known as the big-fish-little-pond effect (Marsh Citation1987). In a non-selective programme such as Law, the first-year cohort is comprised of individuals with more variation in skills, with ‘filtering’ in year one. At a university college, on the other hand, the selection process is done beforehand, and first-year dropout rates are considerably lower (van der Wende Citation2011). Hence, the higher scores of Law first-year students may be an overestimation caused by a less selective comparison group. However, one would still expect that Law students who made it to year two would have higher levels of self-efficacy, resilience and personal initiative than freshmen, which was not the case. Considering the importance of non-cognitive skills for the labour market and later life success, the potential for and extent of their development in HE is a topic that deserves more research.

These two unexpected findings point to the main limitation of this study—its reliance on self-reported data. While its subjectivity is related to several problems, self-assessment is still the most feasible way to simultaneously examine a wider range of skills (Allen and van der Velden Citation2005), especially in cases when objective data cannot be easily obtained. Another drawback of this study concerns its cross-sectional design. One should keep this in mind when interpreting the results in the context of student development. To measure individual growth over time, a longitudinal research design would be required. Such a study could provide more insight into students’ individual skill development trajectories between enrolment and graduation. Lastly, the scope of this study’s findings is also limited by its exclusion of social and cultural capital. Further research is needed to look deeper into the role of these factors in shaping individual outcomes, and to develop measures that can capture their complexity.

Overall, this paper has shown that a seemingly impractical LAE undergraduate degree provides students with a range of career-relevant skills. This points to two wider conclusions. First of all, it refutes the stereotype that LAE has no economic value. As they transition into the labour market, nonetheless, LAE graduates are still likely to face barriers stemming from the inability to showcase the full range of their skills to employers, since many (including the ones analysed in the present study) are not formally assessed in HE. Coupled with the relative newness and unconventionality of LAE degrees in the European context, this may hamper the employment prospects of LAE graduates. In addition to making sure their students develop relevant skills, therefore, LAE institutions should put further effort into making these skills—as well as the LAE model in general—more visible to employers.

Furthermore, and perhaps most importantly, this paper indicates that the dichotomy between ‘learning for learning’s sake’ and ‘learning for career preparation’, often assumed by LAE critics (Logan and Curry Citation2015, 71), is false. As Knight and Yorke (Citation2003) pointed out, even without directly aiming to advance graduate employability, a good learning environment is highly compatible with employability-enhancing policies and practices. Along these lines, it is crucial to stress that employability development in HE can only be substantially achieved at the programme level, through the creation of suitable learning environments, rather than through bolt-on activities and isolated interventions. To that end, this study’s findings suggest that the heterogeneous skill-building effects resulting from exposure to programme-specific features should not be underestimated. Future employability research should place greater emphasis on identifying which HE characteristics and practices are most strongly tied to the development of skills that are necessary for graduates in the twenty-first century.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by Maastricht University’s Ethical Research Committee for the Inner City Faculties (reference number ERCIC_279_20_08_2021).

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (30.1 KB)Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Nicole Kornet and the wonderful teaching staff of the two programmes for making the survey possible. Above all, we are grateful to all the students who participated in this research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Data availability statement

The dataset associated with this paper is available on the research data repository platform DataverseNL at https://doi.org/10.34894/MQMPTT.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The term skills will be used to refer to knowledge, skills, and attitudes.

2 Binkley et al. (Citation2012) identified ten 21st-century skills, grouping them into four categories: ways of thinking, ways of working, tools for working, and living in the world. Ways of thinking include: (a) creativity and innovation, (b) critical thinking, problem solving, decision making, and (c) learning to learn, metacognition.

References

- Allen, J., and R. van der Velden. 2005. The role of self-assessment in measuring skills. REFLEX Working Paper 2: 1–24.

- Arts, J., W. Gijselaers, and H. Boshuizen. 2006. Understanding managerial problem-solving, knowledge use and information processing: Investigating stages from school to the workplace. Contemporary Educational Psychology 31, no. 4: 387–410. doi:10.1016/j.cedpsych.2006.05.005.

- Bandura, A. 1995. Exercise of personal and collective efficacy in changing societies. In Self-Efficacy in Changing Societies, edited by Albert Bandura, 1–45. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Becker, G.S. 1964. Human capital: A theoretical and empirical analysis, with special reference to education. New York: NBER.

- Binkley, M., O. Erstad, J. Herman, S. Raizen, M. Ripley, M. Miller-Ricci, and M. Rumble. 2012. Defining twenty-first century skills. In Assessment and teaching of 21st century skills, eds. Patrick Griffin, Garry McGaw, and Esther Care, 17–66. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands.

- Bledow, R., and M. Frese. 2009. A situational judgment test of personal initiative and its relationship to performance. Personnel Psychology 62, no. 2: 229–58. doi:10.1111/j.1744-6570.2009.01137.x.

- Clarke, M. 2018. Rethinking graduate employability: The role of capital, individual attributes and context. Studies in Higher Education 43, no. 11: 1923–37. doi:10.1080/03075079.2017.1294152.

- Claus, J., T. Meckel, and F. Pätz. 2018. The new spirit of capitalism in European liberal arts programs. Educational Philosophy and Theory 50, no. 11: 1011–19. doi:10.1080/00131857.2017.1341298.

- Cooper, N. 2018. Evaluating the liberal arts model in the context of the Dutch University College. Educational Philosophy and Theory 50, no. 11: 1060–67. doi:10.1080/00131857.2017.1341299.

- Dekker, T. 2017. Liberal arts in Europe. In Encyclopedia of educational philosophy and theory, ed. Michael Peters, 1–6. Singapore: Springer Singapore.

- Dekker, T. 2021. The value of curricular choice through student eyes. The Curriculum Journal 32, no. 2: 198–214. doi:10.1002/curj.71.

- Fearon, C., S. Nachmias, H. McLaughlin, and S. Jackson. 2018. Personal values, social capital, and higher education student career decidedness: A new ‘protean’-informed model. Studies in Higher Education 43, no. 2: 269–91. doi:10.1080/03075079.2016.1162781.

- Fisher, D.M., and R.D. Law. 2021. How to choose a measure of resilience: An organizing framework for resilience measurement. Applied Psychology 70, no. 2: 643–73. doi:10.1111/apps.12243.

- Flowers, L., S.J. Osterlind, E.T. Pascarella, and C.T. Pierson. 2001. How much do students learn in college? The Journal of Higher Education 72, no. 5: 565–83. doi:10.1080/00221546.2001.11777114.

- Frese, M., and D. Fay. 2001. Personal initiative: An active performance concept for work in the 21st century. Research in Organizational Behavior 23: 133–87. doi:10.1016/S0191-3085(01)23005-6.

- Fugate, M., A.J. Kinicki, and B.E. Ashforth. 2004. Employability: A psycho-social construct, its dimensions, and applications. Journal of Vocational Behavior 65, no. 1: 14–38. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2003.10.005.

- Guilford, J.P. 1967. The nature of human intelligence. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Harvey, L. 2001. Defining and measuring employability. Quality in Higher Education 7, no. 2: 97–109. doi:10.1080/13538320120059990.

- Hirschi, A. 2012. The career resources model: An integrative framework for career counsellors. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling 40, no. 4: 369–83. doi:10.1080/03069885.2012.700506.

- Hoareau McGrath, C., B. Guerin, E. Harte, M. Frearson, and C. Manville. 2015. Learning gain in higher education. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation.

- Holdsworth, S., M. Turner, and C.M. Scott-Young. 2018. … Not drowning, waving. Resilience and university: A student perspective. Studies in Higher Education 43, no. 11: 1837–53. doi:10.1080/03075079.2017.1284193.

- Holmes, L. 2017. Graduate employability: Future directions and debate. In Graduate Employability in Context, eds. Michael Tomlinson, and Leonard Holmes, 359–69. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK.

- Humburg, M., and R. van der Velden. 2017. What is expected of higher education graduates in the twenty-first century? In The Oxford handbook of skills and training, eds. Christopher Warhurst, Ken Mayhew, David Finegold, and John Buchanan, 201–20. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Jessup-Anger, J.E. 2012. Examining how residential college environments inspire the life of the mind. The Review of Higher Education 35, no. 3: 431–62. doi:10.1353/rhe.2012.0022.

- Kautz, T., J. Heckman, R. Diris, B.t. Weel, and L. Borghans. 2014. Fostering and measuring skills: Improving cognitive and non-cognitive skills to promote lifetime success. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Kember, D., D.Y. Leung, and R.S. Ma. 2007. Characterizing learning environments capable of nurturing generic capabilities in higher education. Research in Higher Education 48, no. 5: 609–32. doi:10.1007/s11162-006-9037-0.

- Knapper, C., and A. Cropley. 2000. Lifelong learning in higher education. Sterling: Stylus Publishing.

- Knight, P., and M. Yorke. 2003. Employability and good learning in higher education. Teaching in Higher Education 8, no. 1: 3–16. doi:10.1080/1356251032000052294.

- Kovačević, M. 2022. The effect of a general versus narrow undergraduate curriculum on graduate specialization: The case of a Dutch liberal arts college. The Curriculum Journal 33, no. 4: 618–35. doi:10.1002/curj.158.

- Lairio, M., S. Puukari, and A. Kouvo. 2013. Studying at university as part of student life and identity construction. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research 57, no. 2: 115–31. doi:10.1080/00313831.2011.621973.

- Lawton, C. 2019. Conceptions of quality: Some critical reflections on the impact of ‘quality’ on academic practice. In Employability via higher education: Sustainability as scholarship, ed. Alice Diver, 53–65. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Logan, J., and J. Curry. 2015. A liberal arts education: Global trends and challenges. Christian Higher Education 14, no. 1-2: 66–79. doi:10.1080/15363759.2015.973344.

- Lounsbury, J.W., T. Hutchens, and J.M. Loveland. 2005. An investigation of big five personality traits and career decidedness among early and middle adolescents. Journal of Career Assessment 13, no. 1: 25–39. doi:10.1177/1069072704270272.

- Luthans, F., C.M. Youssef-Morgan, and B.J. Avolio. 2015. Psychological capital and beyond. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press.

- Marsh, H.W. 1987. The big-fish-little-pond effect on academic self-concept. Journal of Educational Psychology 79, no. 3: 280–95. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.79.3.280.

- McArdle, S., L. Waters, J.P. Briscoe, and D.T. Hall. 2007. Employability during unemployment: Adaptability, career identity and human and social capital. Journal of Vocational Behavior 71, no. 2: 247–64. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2007.06.003.

- Runco, M. 2011. Divergent thinking. In Encyclopedia of creativity, eds. Mark Runco, and Steven Pritzker, 400–403. San Diego, Palo Alto: Elsevier.

- Schwarzer, R., and M. Jerusalem. 1995. Generalized self-efficacy scale. In Measures in health psychology: A user’s portfolio. Causal and control beliefs, eds. Marie Johnston, Stephen Wright, and John Weinman, 35–37. Windsor, UK: NFER-NELSON.

- Seifert, T.A., K.M. Goodman, N. Lindsay, J.D. Jorgensen, G.C. Wolniak, E.T. Pascarella, and C. Blaich. 2008. The effects of liberal arts experiences on liberal arts outcomes. Research in Higher Education 49: 107–25. doi:10.1007/s11162-007-9070-7.

- Smith, B.W., J. Dalen, K. Wiggins, E. Tooley, P. Christopher, and J. Bernard. 2008. The brief resilience scale: Assessing the ability to bounce back. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine 15, no. 3: 194–200. doi:10.1080/10705500802222972.

- Teichler, U. 2013. Universities between the expectations to generate professional competences and academic freedom: Experiences from Europe. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 77: 421–28. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.03.097.

- Tomlinson, M. 2012. Graduate employability: A review of conceptual and empirical themes. Higher Education Policy 25, no. 4: 407–31. doi:10.1057/hep.2011.26.

- Tomlinson, M. 2017. Forms of graduate capital and their relationship to graduate employability. Education + Training 59, no. 4: 338–52. doi:10.1108/ET-05-2016-0090.

- Trede, F., R. Macklin, and D. Bridges. 2012. Professional identity development: A review of the higher education literature. Studies in Higher Education 37, no. 3: 365–84. doi:10.1080/03075079.2010.521237.

- Tymon, A., and S. Batistic. 2016. Improved academic performance and enhanced employability? The potential double benefit of proactivity for business graduates. Teaching in Higher Education 21, no. 8: 915–32. doi:10.1080/13562517.2016.1198761.

- UCDN (University College Deans Network). 2017. Statement on the role, characteristics, and cooperation of liberal arts and sciences colleges in the Netherlands. Accessed September 08, 2022. https://www.universitycolleges.info/.

- van Damme, D. 2016. Transcending boundaries: Educational trajectories, subject domains, and skills demands. In Experiences in liberal arts and science education from America, Europe, and Asia, eds. William C. Kirby, and Marijk C. van der Wende, 127–42. New York: Palgrave Macmillan US.

- van der Wende, M.C. 2011. The emergence of liberal arts and sciences education in Europe: A comparative perspective. Higher Education Policy 24, no. 2: 233–53. doi:10.1057/hep.2011.3.

- van Dinther, M., F. Dochy, and M. Segers. 2011. Factors affecting students’ self-efficacy in higher education. Educational Research Review 6, no. 2: 95–108. doi:10.1016/j.edurev.2010.10.003.

- Virtanen, A., and P. Tynjälä. 2019. Factors explaining the learning of generic skills: A study of university students’ experiences. Teaching in Higher Education 24, no. 7: 880–94. doi:10.1080/13562517.2018.1515195.

- Wielkiewicz, R.M., and A.S. Meuwissen. 2014. A lifelong learning scale for research and evaluation of teaching and curricular effectiveness. Teaching of Psychology 41, no. 3: 220–27. doi:10.1177/0098628314537971.

- Wilton, N. 2011. Do employability skills really matter in the UK graduate labour market? The case of business and management graduates. Work, Employment and Society 25, no. 1: 85–100. doi:10.1177/0950017010389244.

- Yorke, M. 2006. Employability in higher education: What it is – what it is not. York: The Higher Education Academy.