Higher education institutions (HEIs) are not only potential sites of teaching environmental (un)sustainability but are essential sites to curb environmental injustices, planetary sustainability, and devastation to Nature, including humans.Footnote1 A key question is, what are the politics that support or oppose higher education’s (HE) role of critically teaching environmental sustainability for students’ praxis? Questioning also includes if this is a central role of HE. In other words, what are the influences on and from HE teaching that helps or hinders students’ critical reflexivity for acting environmentally? Criticality is essential in HE teaching because transformative actions are crucial to ending anti-environmentalism by disrupting perverted commonsense that falsely justifies acts of socio-environmental injustices and planetary unsustainability (Gadotti Citation2008a, Citation2008b; Misiaszek Citation2020b; Misiaszek et al. Citation2011; Misiaszek and Rodrigues Citation2023; Misiaszek and Torres Citation2019). Directly or indirectly, teaching environmental (un)sustainability is tethered to local-to-global politics of HE’s other roles, such as sites of knowledge production and legitimization, economics, labor, and activism.

We argue that problematizing the complex and often contesting roles of HE teaching as helping or hindering environmentally sustainable praxis is essential for disrupting Nature’s demise, including our own as humans. This includes teaching to actively counter the politics upon and from HEIs and unlearn anti-environmental commonsense. To respond to this need for HE teaching worldwide, we have this Special Issue (SI) within Teaching in Higher Education (TiHE) entitled ‘Higher Education Teaching of Environmentally Just Sustainability.’

The SI was constructed rather uniquely by asking the authors to ‘dialogue’ with the questions we posed in our TiHE Points of Departure (PoD) article entitled ‘Six critical questions for teaching justice-based environmental sustainability (JBES) in higher education’ (Misiaszek and Rodrigues Citation2023).Footnote2 In the PoD, we provided key groundings for JBES but emphasized that contextualizing JBES’s definitions and framings is essential within HE teaching and research. The six questions revolve around problematizing the following themes: the ideologies of ‘development’ and ‘sustainability’ taught in HE, the politics and responsibilities of teaching JBES in HE, and the epistemological groundings of HE teaching JBES, as well as asking what epistemologies are frequently absent (e.g. epistemologies of the South, Indigenous knowledges). This last theme includes questioning if prominent epistemologies instill anthropocentrism.Footnote3 or not. In addition, SI authors dialogued with each other’s work by sharing several versions of their abstracts and manuscript versions between them.Footnote4 In addition to normal review activities as the SI editors, we also suggested possible specific connections with other papers to support dialogues between the authors. This dialogical process as an ‘assemblage’ methodology used in this SI has been a pattern used in The Journal of Environmental Education for SIs since 2016 (Payne Citation2016, Citation2018; Rodrigues and Lowan-Trudeau Citation2021; Rodrigues et al. Citation2020). It ‘aims to potentialize constructive dialogue and cross-referencing among authors in order to create a coherent and generative unity that is, indeed, a “special” issue’ (Rodrigues and Lowan-Trudeau Citation2021, 301).

This editorial’s structure is quite unique too, by focusing on the dialectic assemblage – how authors interacted with one another’s work, the (dis)connections between their arguments, and their responses to our six questions. In the first part, we map their articles within three main themes, the articles’ cross-citing within this SI, and give ten topics when cross-citing occurred. The second part goes through each of the PoD’s six questions to describe how the authors responded to them directly. We hope that this SI’s dialectic assemblage and this editorial will help guide reading across the SI while encouraging reading it holistically. The conclusion poses the need for readers to determine the SI’s silences – what is missing or unvoiced?

Mapping dialogue between SI authors

The SI’s call for critical writings on teaching JBES in HE has brought together a SI comprising of articles with diverse topics, pedagogical approaches, theoretical and epistemological groundings, and geographic and environmental contexts. An important acceptance criterion for the rather large amount of submitted abstracts was considering this diversity. Determining themes and separating articles under them was neither simple, as they were very interconnective, nor does the SI represent a single ‘best’ organization for the SI. The following three themes emerged from our readings of their work: (1) Essential Transformation for HE Teaching; (2) Disrupting (Settler) (Neo-)Coloniality and Northern Supremacy; and (3) Problematizing ‘Development,’ ‘Sustainability,’ and ‘Justice.’

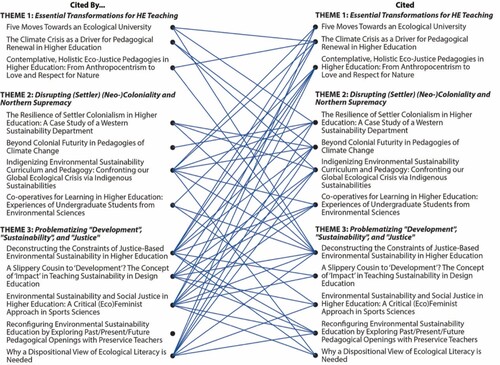

To varying degrees, the SI authors made numerous connections between their work and others in the SI, as seen in . The visual messiness and rather hard-to-link lines between the articles illustrate this with a simple glance. Almost all authors cross-referenced across the SI’s three themes, indicating the intersectionality of the themes, theories, and contextualities in which the authors wrote upon. Please note that Tracy Charlotte Young and Karen Malone (Citation2023) did not receive other SI authors’ manuscripts due to technical constraints and an error on the part of the SI editors, which explains the lack of cross-referencing in their article ‘Reconfiguring environmental sustainability education by exploring past/present/future pedagogical openings with preservice teachers.’

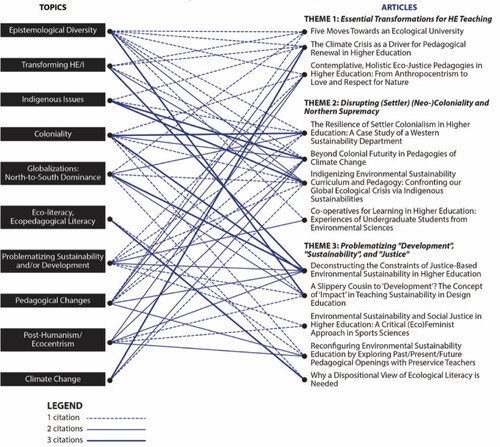

indicates the following ten topics that emerged from our analysis of the cross-referencing: epistemological diversity, transforming HE/Is, Indigenous issues, coloniality, globalizations: North-to-South dominance, eco-literacy & ecopedagogical literacy, problematizing sustainability and/or development, pedagogical changes, posthumanism and ecocentrism, and climate change issues. Determining the topics was also particularly difficult because of the complex intersectionalities of the ten themes we chose, as well as numerous other possible topics not chosen.

Although we do not delve into specific analysis on connections these figures illustrate, we hope they help guide readers on specific issues of HE teaching for JBES across the SI. Alternatively, we also see them displaying the benefits of reading the SI holistically to critically understand better the needs, trends, challenges, and possibilities of teaching for JBES that leads to globally all-inclusive social-environmental justice and planetary sustainability. Lastly, we view the figures and the interactions with our PoD’s six questions as successful dialogue within SIs, in which often connections are only made between articles within editorials. We are not stating that there were not various challenges and concerns, including problematizing if ‘dialogic(al)’ is the best term, some of which we hope to unpack in future publications.

The six questions and responses

In the PoD article, we argued that our six questions are:

essential for unpacking if JBSE should be a focus in HE and to what degree; what are the aspects of HE, including the more deep-seated, hidden ones, that hinder teaching for JBSE; and what are the politics behind all of this? We purposely do not explicitly define ‘justice’ because we want readers’ responses to our question to (in)directly define this pluralistic term themselves. (Misiaszek and Rodrigues Citation2023, 211)

[H]ow do HE instructors teach to define, frame, question, measure, and (de)prioritize ‘sustainability?’

… asking these same aspects in HE teaching of ‘development’ is our second question

[W]hat are the politics of, and upon, HE that effect teaching of/for JBES?

What should be the responsibilities of teaching for JBES praxis in HE?

What are the dominant epistemological groundings of HE teaching that align with or oppose JBES?

What are the anthropocentric influences on HE teaching JBES?

The following six sections analyze the authors’ responses to these questions with very brief summaries given when an SI article is initially referenced. This analysis is on how SI authors have directly answered our questions with specific citations of our PoD in their articles. The analysis is far from all-inclusive, with direct responses to our six questions throughout most of the articles. For example, five articles listed the questions overall, with a few not citing the PoD again directly but giving responses throughout their writing.

Articles within this latter group were Sandra Ajaps’ (Citation2023) and Sharon Stein et. al. (Citation2023). Deconstructing what constrains HE teaching from leading to transformative praxis with socio-environmental justice and sustainability outcomes is Ajaps’ focus. (Neo)coloniality within HE (teaching) is a critical constraint that Ajaps unpacks as it entrenches ‘epistemic inequity, globalisation, neoliberalism, pedagogical incompatibility, anthropocentrism, and social inequality’ (2023, 1024). Sharon Stein et al. (Citation2023) problematize how HE teaching and HEI structures most frequently have the following two competing, conflictive aspects: ‘recognizing a growing gap between the world their education was designed to prepare them for, and the world they will inherit’ (2023, 987; citing (Hickman et al. Citation2021)). They propose pedagogies of climate education otherwise, named to emphasize needed imaginaries for teaching to

develop the stamina and the intellectual, affective, and relational capacities that will enable them to respond to the CNE [(climate and nature emergency)] and other wicked challenges with justice-oriented coordinated action that is appropriate and relevant to each context they will face. (2023, 988)

The essentialness of decolonizing HE towards students critically imagining possible futures is argued throughout their article.Footnote5

Due to the same constraints and editorial error as previously mentioned, Young and Malone (Citation2023) did not reference the six-question PoD. Their article is on problematizing HE teaching for preservice educators to not challenge the Anthropocene by over-prioritizing humanistic groundings to entrench anthropocentrism rather than disrupting it with planetarism. In Malone’s (Citation2018) book entitled Children in the Anthropocene, she utilizes Crutzen and Stoermer’s (Citation2000) defining of the Anthropocene as

considering … growing impacts of human activities on earth and atmosphere … it seems to us more than appropriate to emphasize the central role of mankind in geology and ecology by proposing the term “Anthropocene” for the current geological epoch. (Citation2000, 17)

Before continuing to the authors’ direct responses to the PoD’s six questions, it is important to note that this editorial does not have the space to unpack the connections between the questions, which are largely inseparable. We discuss some specific examples of this, but this is far from fully addressing the messiness between the questions and our mapping of the authors’ responses that follows. However, we ‘actively celebrate the messiness of our knowledge making’ (Turnbull Citation2000, 227; cited in McClam and Flores-Scott Citation2012) as illustrated by the messy overlapping between our questions, responses from SI authors, and the previously discussed themes we found to emerge from the SI articles. We hope you will also read the PoD, which discusses this messiness between the six questions, among other vital aspects. (McClam and Flores-Scott Citation2012)

(1) What is sustainability?; (2) Development?

‘Environmental sustainability’ in this SI refers to achieving globally all-inclusive socio-environmental justice with planetary sustainability that includes, and is also beyond, the anthroposphere (i.e. all of Nature) (Gadotti Citation2008a, Citation2008b; Gutiérrez and Prado Citation1989; Misiaszek Citation2020a). The focus on socio-environmental justice includes acknowledging that environmental and social violence are inseparable spheres/scapes. Within this context, ‘development’ is acknowledged as innately essential in HE teaching (environmental) sustainability, as the term ‘sustainable development’ is abundantly touted as a universal goal; however, these terms are too infrequently read critically to deconstruct the underlying and too-often systematically hidden goals (Misiaszek Citation2020b). HE teaching of these concepts calls for numerous questions to be problematized. Does our teaching instill the prioritizing of certain populations’ development aligning with sociohistorical oppressions (e.g. racism, (neo)coloniality, patriarchy, heteronormativity)? Or, opposingly, counter notions of development on the backs of the othered’s de-development, oppressions, and unsustainability? If development is grounded in economics, is it taught through neoliberalism or through economic justice, labor justice, and/or environmental sustainability framings, among others? Crucial non-anthropocentric interrogation asks what are the metrics and benchmarks of development primarily being taught and how do they speak to the question of ‘what is in it for Nature’ (Rodrigues and Lowan-Trudeau Citation2021).

Essential to achieve planetary sustainability is HE teaching to critically read how humans’ actions align, or not, with the well-being for all that makes up Earth. Questioning how HE teaching of sustainability, with or without ‘development,’ views Nature-human, world-Earth relations is critical. This includes questioning how ideological teaching of Nature and development in HE leads to praxis of students’ (un)sustainable actions. Unpacking how theory-practice gaps (or ‘chasms’ – see, for example, Payne Citation2020) persist in HE teaching is essential to better understand the challenges and possibilities of environmental praxis due, in part, from HE classrooms.

All the SI articles both directly and indirectly critically deconstructed and often reconstructed the definitions and framings of ‘development’ and ‘sustainability’ that are taught in HEIs. An example of two authors directly unpacking this issue are Haven Bills and Sonja Klinsky (Citation2023), who focused on settler colonialism while interviewing educators at Arizona State University’s School of Sustainability in a qualitative research project. In his article ‘The Resilience of Settler Colonialism in Higher Education: A Case Study of a Western Sustainability Department,’ he found that ‘multiple faculty identified how they themselves are products of Western education and linked this to the sustainability challenges they attempt to understand and address’ (Bills and Klinsky Citation2023, 973). Bills calls for pedagogically ‘deepen discussions of how faculty define, frame, and engage with sustainability and topics of sustainable development’ (Bills and Klinsky Citation2023, 980; citing (Misiaszek and Rodrigues Citation2023)) in HE in order to surpass individual and systematic barriers to achieve JBES potentially.

Jing Lin et al. (Citation2023) argue in their article ‘Contemplative, Holistic Eco-Justice Pedagogies in Higher Education: From Anthropocentrism to Love and Respect for Nature’ that JBSE must normalize the interconnections between humans and the rest of Nature in creative ways of teaching what is development and associated (un)sustainability, delving into larger ontological questions they pose. This is especially related to Anti-Anthropocentric and Eco-Justice pedagogies, as termed by them. Their arguments are (partially) based on empirical data from a course taught by Jing Lin, the article’s first author, in a graduate-level course entitled Global Climate Change and Education at the University of Maryland, College Park.

Ian Kinchin (Citation2023) discusses possibilities for a shift in HE from the current industrial model infused with neoliberal ideology towards an ‘ecological’ model with goals to achieve greater levels of social justice within the university, links neoliberalism with HE in problematizing the framings taught in HEIs. His article, ‘Five Moves Towards an Ecological University,’ provides five crucial steps for successful HE teaching of JBES. These arguments align closely with Deanna Meth, Claire Brophy, and Sheona Thomson’s (Citation2023) article ‘A slippery cousin to “development”? The concept of “impact” in teaching sustainability in design education.’ They argue that HE teaching must be saturated with ‘radical sustainability discourses that attempt to challenge the “industrial growth paradigm”’ (1040). Their article critically problematizes the neoliberalization of the term ‘impact’ with ideologies of development in teaching design courses that can systematically deprioritize socio-environmental justice and planetary sustainability. Meth et al. (Citation2023) are informed by analyzing undergraduate teaching by asking what is necessary to both disrupt neoliberal education and to teach to unlearn false commonsense of neoliberal ‘impact’ as grounding development goals.

Dennis Koyama and Takehiro Watanabe (Citation2023), and Tristan McCowan (Citation2023) discuss how learning about climate change and its associated values, knowledge systems, and societal structures serve a broader purpose to drive positive transformation in the university (curricula). Both articles stress the need for diverse, critical local-to-global perspectives with deepened planetary understandings of development and sustainability. McCowan (Citation2023), in ‘The climate crisis as a driver for pedagogical renewal in higher education,’ argues that the injustices and planetary unsustainability that will result from untethered climate change must be a catalyst for radically transforming higher education teaching through ontological (human and rest of Nature interdependence), epistemological diversity, and axiological (‘the values that underpin what we do in our lives, the good and the just (Bhaskar Citation2013)’ (p. 935)). The SI PoD article ‘Why a Dispositional View of Ecological Literacy is Needed’ by Dennis Koyama and Takehiro Watanabe (Citation2023) unpacks the need for HE teaching to critically read (anti-)environmentalism for leading to praxis. They utilize various models and goals of ecological literacies, including ecopedagogical literacy, framed by Misiaszek (see Citation2020b).

(3) Politics of teaching JBES in HE

Politics of, and from, HE teaching of JBES is discussed throughout all of the SI articles. Specifically, we asked what are the ‘politics effecting JBES teaching in classrooms both within HE and wider societal politics upon HEIs’ (Misiaszek and Rodrigues Citation2023, 214). Along with the direct mentions of HE/I’s politics, aspects of coloniality and Indigenous-related oppressions can also be read as directly responding to this question. It is especially true as we look at the many authors who wrote on how intensifying processes of globalization coincide with neoliberalism in HE teaching worldwide.

When the authors addressed our PoD’s six questions directly, the term ‘politics’ included the entrenching of neoliberalism and anthropocentrism (Lin et al., Citation2023; Koyama and Watanabe Citation2023; Meth, Brophy and Thomson Citation2023) and ‘development’ (Meth, Brophy and Thomson Citation2023), solutionist pedagogies with human intervention as focused upon, rather than living with, the rest of Nature (Koyama and Watanabe Citation2023), SI cross-referencing (Stein et al. Citation2023 & Young and Malone Citation2023),Footnote6 pedagogical and epistemological dominance guided by coloniality and settler coloniality (Koyama and Watanabe Citation2023), SI cross-referencing (Bills and Klinsky Citation2023), globalizations that are akin to neocoloniality (Meth, Brophy and Thomson, Citation2023; Koyama and Watanabe Citation2023), and distancing of environmental violence (Koyama and Watanabe Citation2023).Footnote7 Delving more into the politics of (neo)coloniality and utilizing theories on resilience, Bills and Klinsky (Citation2023) argues the need for more active disrupting of settler colonialism within HE teaching, research on how faculty are attempting such disruptions, and calling for training for anti-colonial JBES education. In advocating for the integration of Indigenous perspectives in course offerings, campus management, and scholarly production of HEIs, Jeremy Jimenez and Peter Kabachnik (Citation2023) stress the need for ‘Indigenous sustainabilities’ by, in part, disrupting the politics of dominant Northern/Western (mis)lessons of sustainability and the politics of misguided sole-legitimacy. Their article is named ‘Indigenizing Environmental Sustainability Curriculum and Pedagogy: Confronting Our Global Ecological Crisis Via Indigenous Sustainabilities.’ They critique the disproportionate focus of sustainability on climate change, resulting in a debate that reinforces ‘business-as-usual’ industrial growth. Alternatively, they argue that a curricular and pedagogical focus on Indigenous sustainabilities in HE could be the basis for a paradigm shift to discussing long-term sustainability.

(4) HE responsibilities in JBES (Teaching)

The theme of HE teaching’s responsibility for environmental justice and planetary sustainability is discussed throughout the SI articles, especially emphasizing the crucial roles of HE in public spheres. Responses to this fourth question mainly focus on needing holistic approaches to JBES teaching across HEIs (e.g. teaching across disciplines, HEI structures, activities, and communities). Finding HE’s barriers needing to be breached for holistic approaches was widely focused upon throughout the SI. This coincides very closely with the authors’ responses to the previous question three on the politics of non-JBES teaching. Lin et al. (Citation2023) emphasize the ‘insurmountable’ feeling of changing long established norms/politics of HEIs by ‘Anti-Anthropocentric’ norms; Ian Kinchin (Citation2023) discusses how faculty feel sometimes academically assaulted by questioning long-held theoretical and disciplinary epistemological groundings by post-abyssal thinking (see Santos Citation2014; Santos Citation2018); and McCowan (Citation2023) emphasizing that without active, purposeful disruption, an anti-environmental linked ‘societal organisation that does not extinguish itself’ (947).

All these aspects can be seen as coinciding with Boaventura de Sousa Santos’ (Citation2018) emphasis that teaching students through reflexivity through diverse ecologies of knowledges for unlearning ideologies rooted in injustices and unsustainably (i.e. coloniality, patriarchy, and capitalism as grounding Epistemologies of the North) is a key HE responsibility. Koyama and Watanabe (Citation2023) give vignettes on the responsibilities and essence of teaching ecological, ecopedagogical literacies for true JBES, including disrupting ‘anthropocentric curricula plaguing education worldwide’ (1108). The need for HE to be responsible for global initiatives, specially the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), is another crucial aspect discussed by L. Fernando Martínez Muñoz et al. (Cuenca-Soto et al., Citation2023) in their article ‘Environmental Sustainability and Social Justice in Higher Education: A Critical (Eco)Feminist Approach in Sports Sciences.’ Through ecopedagogical and ecofeminist lenses, Muñoz et al. analyze learning of socio-environmental justice and sustainability awareness in a critical, feminist service-learning program. They also critically unpack the limitations of their and similar pedagogical programs to provide a rich analysis of the successes, failures, and challenges of such HE teaching.

(5) Epistemologies in JBES teaching in HE

Crucial limits/challenges are set by epistemologies in HE teaching of JBES. For example, what epistemological groundings are frequently present or absent in HE teaching (un)sustainability for ‘development’? This coincides, in part, with Santos’ (Citation2018) arguments that education rooted in epistemologies of the North form disciplinary, theoretical, and pedagogical absences that do not allow for praxis for JBES to emerge from (HE) pedagogies. Beyond (or alongside) North–South issues in HE teaching epistemologies (see Payne and Rodrigues Citation2012), teaching through planetary lenses (e.g. humans as part of, rather than separate from, Nature), and/or anthropocentric lenses (further unpacked in the responses of the next question) calls into probing, in a more general sense, what epistemology(ies) is sustainability being taught through, or not, in HE settings.

Deconstructing Epistemologies of the North to disrupt their dominance is seen as essential within Southern Theories (Assié-Lumumba Citation2017; Santos Citation2018; Takayama et al. Citation2017) and necessary in environmental pedagogies (Misiaszek Citation2020a; Santos Citation2018), as well as essential in HE teaching for JBES (Misiaszek Citation2020b; Misiaszek and Rodrigues Citation2023). Santos (Citation2018) argues that the pedagogical goals of Epistemologies of the South are not to replace Epistemologies of the North’s hegemony, but to teach through diverse ecologies of knowledges to, in part, disrupt their groundings of coloniality, patriarchy, and capitalism which only further entrenches injustices, unsustainability, and anthropocentrism. This not only includes (HE) curricula but also the disciplinary cannons they are built upon, as Santos (Citation2018) stresses the need to determine and deconstruct the absences (i.e. sociology of absences) to meaningfully include needed, and too-often delegitimized, emergences (i.e. sociology of emergences) essential for JBES teaching and praxis. This includes unlearning of knowing through Northern hegemony, including disciplines and theories grounded upon them (Santos Citation2018). The essence of these arguments can be read throughout all the articles with and without utilizing these terms directly. Some instances have already been discussed in our analysis of how SI authors have answered the previous four questions.

Bills and Klinsky (Citation2023) argues that these crucial epistemological aspects are ‘muted’ within JBES scholarship, specially delegitimizing teaching of, and through, Indigenous knowledges and settler colonialism. Several articles directly called for HE to focus on tearing down the barriers formed by (settler) (neo)coloniality that prevents from knowing beyond settler/Northern/Western epistemologies (Bills and Klinsky Citation2023, Jimenez and Kabachnik Citation2023, Lin et al., Citation2023, McCowan 2023, Kinchin Citation2023). As previously discussed, the need for Indigenous sustainabilities is how Jimenez and Kabachnik (Citation2023) respond to how true JBES can be achieved. Kinchin (Citation2023) argues for this need within HEIs but acknowledges the difficulties achieving it due to the suggestion of ‘“epistemological pluralism” … caus[ing] a nervous “shudder” (sensu Charteris Citation2014) among many academics’ (Kinchin Citation2023, 924). Addressing this strong reluctance of many HEIs, McCowan (Citation2023) comments that ‘this [epistemological paradigm] shift is unlikely to take place overnight, at least not in mainstream institutions’ (McCowan Citation2023, 945). He also emphasizes the need for transdisciplinary approaches, along with the epistemological re/deconstruction of disciplines themselves (McCowan Citation2023). Disrupting anthropocentrism within HE teaching was also the focus of epistemological discussions by Meth et al. (Citation2023), which will be the focus of our analysis in the sixth and final question. All these arguments coincide closely with Tierney’s (Citation2018) argument for needing HE teaching for global meaning-making that ‘represents a turn to a global politic involving cross-cultural research and pedagogical engagements that acknowledge and capitalize upon cultural understandings and ways of knowing’ (p. 397).

Mariona Espinet et al. (Citation2023) call for incorporating co-operative universities for epistemological diversity for teaching sustainability through ‘non-hegemonic sustainability perspectives [that] share similar values such as empowerment of marginalized communities, participatory governance, equity and justice, or interdependence and connectedness’ (p. 1009). As can be read in their article’s title ‘Co-operatives for Learning in Higher Education: Experiences of Undergraduate Students from Environmental Sciences’ (Espinet et al., Citation2023), they argue for restructuring universities based on co-operative movements in which ‘an autonomous association of persons united voluntarily to meet their common economic, social, and cultural needs and aspirations through a jointly-owned and democratically-controlled enterprise’ (ICA (International Cooperative Alliance) Citation1995, cited in Espinet et al., Citation2023, 1007). Overall, they unpack and analyze service learning and co-operative pedagogies to counter hegemony by disrupting neoliberal commodification of work, othering, and anthropocentrism. Their context is a public university in Catalonia (Spain) teaching courses for environmental degrees. They argue that critical, collective, dialectical pedagogies are essential for students to construct possible solutions to end injustices and unsustainability from neoliberal priorities.

(6) (Anti-)Anthropocentrism in HE?

The last question was how HE teaching must, as Misiaszek (Citation2020b) stated, disrupt world-Earth distancing that has humans (making up the world) as separate from Earth/Nature. In these arguments, the ‘world’ is all humans and human societies, while Earth is all of Nature, including the world. In slightly different terminologies, all the SI Authors emphasize needing HE teaching to focus on world-Earth de-distancing. In our PoD (Misiaszek and Rodrigues Citation2023), we discussed the reason why we include within teaching for JBES both socio-environmental justice and planetary sustainability. This is due to some scholarship viewing justice as needing to be reciprocal and only accomplished by humans. Such academic arguments include ecofeminist ones by Karen Warren (Citation2000). Such arguments do not devalue the rest of Nature but identify humans as having unique abilities of self-reflexivity, having histories, and the ability for praxis, as can be unpacked from Paulo Freire’s work on ecopedagogy too (see Freire Citation2004; Gadotti and Torres Citation2009; Misiaszek and Torres Citation2019). However, there are many counter-arguments that our PoD does not include. For example, the conceptualization of ecophenomenology, including the possibility of the non-human world having intentionality and being susceptible to transcendence, standing critical to how classical phenomenology reinforces the theoretical structures of anthropocentrism as it qualifies such categories as distinctively human (Rodrigues Citation2018). Other examples include the agency of plants (Carvalho et al. Citation2020) and animals (Iared and Hofstatter Citation2022) as teachers embracing possibilities of human-nonhuman shared histories and inter-connected praxis. Although TiHE focuses on criticality with the journal’s subtitle ‘Critical Perspectives’, we would argue that this criticality includes reinventions through theories of postcriticalism and posthumanism as several scholars have argued (James Citation2017; Le Grange Citation2018; Nakagawa and Payne Citation2019; Rodrigues et al. Citation2020; Ulmer Citation2017). This is essential for disrupting anthropocentrism in HE teaching and all aspects of HE overall.

SI authors tackled anti-anthropocentrism in various ways, some of which we have already given. Disrupting settler colonial epistemologies that commodify Nature as property within capitalism’s foundations was focused upon by Bills (Citation2023). Lin et al. (Citation2023) call for creative and innovative ways to radically re-teach what development in non-anthropocentric ways is and richly discussed the possibilities of pedagogical storytelling by ‘integrating the powerful fields of contemplative inquiry – especially meditation and deep reflexivity – and Anti-Anthropocentrism as a guiding light’ (Lin et al., Citation2023, 965). The essence of needing counterstories within HE teaching is ‘a method of telling the stories of those people whose experiences are not often told (i.e. those on the margins of society)’ (Solórzano and Yosso Citation2002, 32). Disrupting anthropocentrism by teaching to unlearn knowing the world-Earth solely through the Epistemologies of the North, as argued by Santos (Citation2018), is called for by Meth et al. (Citation2023). Koyama and Watanabe (Citation2023) unpacked the needs of anti-anthropocentric literacies by ‘rethink[ing] ecological literacies through aspects of critical literacies of development, sustainability, and sustainable development (Misiaszek Citation2020b); global citizenship (Davies Citation2006; Misiaszek Citation2020a), and ecopedagogies (Misiaszek Citation2018, Citation2020a, Citation2020b)’ (p. 1107).

Conclusion: remaining silences

Continuously de/reconstructing HE teaching that leads to praxis grounded upon goals of JBES globally and planetarily is crucial for disrupting acts of unsustainable environmental violence. HE forms contested terrains of disrupting false ideologies that justify such violence but also, unfortunately, sustains and intensifies such false ideologies within teaching and its roles of public pedagogy, knowledge production, and cultural reproduction outside of HEIs (Misiaszek Citation2020b, Citation2022b). The foundational question problematized throughout this SI is how HE teaching can aid in reaching towards the former aim of unlearning and disrupting ways of knowing that justify unsustainable environmental violence. The articles making up this SI provide a diverse, interconnective array of themes and topics on teaching for JBES in higher education through varied contexts. However, as with any collection of writings, no matter the length, there will undoubtedly be certain theorizing, pedagogies, voices, artifacts, and contexts, among other aspects, left unexplored and unsaid. This is not to devalue this SI and the authors’ work, but for pedagogical scholars to critically further the arguments within and between the articles, arguing with and against their words and finding the limitations, or silences, to build upon.

Borrowing from two SI editorials we have done separately revolving on silences, Rodrigues’ (Citation2020) SI deconstructs aspects of research and theorizing that are labeled as ‘new’/‘post’ in environmental education research. Rodrigues (Citation2020) discusses how:

… these silences or absences highlight that which is an underrepresented and, therefore, [are] highly relevant discussion’ (Citation2020, 177). … Returning to the shade of the oak tree (or mango tree, or any other), these silences are presented as an invitation for passing along the talking stick. The spiral/rhizomatic nature of the proposed research agenda/methodological framework is dynamic, and the key themes are generative. The presented ‘samples’ are valuable, but ‘starters’ only, as the experienced authors were humble in participating in the slow and dialogical assemblage of this SI, and courageous in openly (ex)posing possibilities and limitations. (p. 181)

Misiaszek (Citation2022a) analyzed the work done with Paulo Freire’s work since his book Pedagogy of the Oppressed (Citation1970) and his centennial birthday in 2021, with the editorial focusing on his constructs of needing continuous reinvention of educational work. This includes Freire’s own self-reflexive silences (Au and Apple Citation2007; Torres Citation2022), including environmentalism, which he stressed was missing in his writings but was working on ecopedagogy to be the focus for his next publication, unfortunately, unfinished due to his untimely death (Gadotti and Torres Citation2009; Misiaszek and Torres Citation2019). All academic work has limitations, from teaching to researching to writing and beyond. Unrecognizing limitations by falsely claiming any work as complete without any absences or silences is inherently problematic. This argument emerges, in part, from Freire’s (Citation1970) concept that all humans are unfinished beings (and societies) and, in turn, counters fatalistic notions of a single environmentally oppressed future. Also included is that our work, pedagogical and other scholarship, is finished without needing reinvention. Recognizing the environmental silences of Freire allows us to reinvent his work, for example, into ecopedagogy (also constantly being reinvented – Ivo Citation2022) and through theories of postcriticalism and posthumanism, as well as Freire reinventing his own work by recognizing his own silence of environmentalism (see Freire Citation2004). Another example includes his significant revisions of Pedagogy of the Oppressed after reading Franz Fanon’s Wretched of the Earth (Citation1963) by recognizing his silence of decoloniality before the book went to print.

Freirean reinvention includes denouncing teaching for instilling false consciousness of oppressions and unsustainability to announce teaching saturated with possibilities for a better, sustainable world-Earth (Morrow Citation2019; Morrow and Torres Citation2019). Critically reading this SI includes not only acknowledging the generative potential of what is proposed by the assemblage of papers with careful transference (not generalization) to other ‘places’ and their specific ethos, but also deconstructing remaining silences to further successful JBES teaching in higher education in different geo-epistemological (see Canaparo, Citation2009) contexts. Hopefully, we will see the discussion continued in future publications on the topic in TiHE and other loci of shared knowledge.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Notes

1 Aligning with principles of ecolinguistics, Nature will be upper-cased throughout this article, and the term ‘the earth’ will not be used to de-objectify Earth with the article term ‘the’ and the 'E' will be uppercased. Additionally, ‘rest of’ is written before ‘Nature’ to indicate that humans and the human-world overall are part of Nature.

2 We distributed our PoD drafts to all the SI authors shortly after we accepted their proposed manuscripts at the abstract stage. In this email, we described the overall dialogical assemblage process, firstly with their interaction with the six questions of the PoD and eventually with the sharing drafts of the manuscripts among SI authors.

3 Anthropocentrism views humans as having superior distinctiveness in relation to the rest of Nature. Thus humans are outside nature (lowercased to emphasize the deprioritization and separateness of nature from humans).

4 After asking potential authors to write up <700-word abstracts and/or extended <1500-word abstracts, we shared the accepted ones between the authors once we received approval for sharing their work. Once the first drafts of the full papers (around 6000 words) were reviewed, we shared the anonymous versions among all the perspective SI authors. In the email on the PoD’s six questions, we included the note to write us if there were any hesitation in distributing draft versions of manuscripts – none of the authors wrote back on this aspect. This sharing was with the stipulation that there were possibilities that not all the proposed abstracts would fully be successful through the editorial blind-review processes.

5 Futures is plural to counter ideologies that a single, predestined, and often fatalistic future is undeniable, and teaching that entrenches such ideologies.

6 The ‘cross-referencing’ label in the citations indicates a direct response to one of our six PoD questions which also included SI cross-referencing in their responses.

7 ‘[World-Earth] distancing that is beyond physical distancing to include also othering of people by teaching and research through theoretical lens focusing on class, race (ecoracism), gender (ecofeminism), religion (liberation theologies), colonialization, Indigenous communities, and other theoretical framings that help to understand structural and historical socio-environmental oppressions. But what about teaching that focuses on non-human environmental issues that are problematized beyond effects on humans– biocentric framing beyond humans’ “interests?”' (Misiaszek Citation2018, 134). ‘Teaching towards such de-distancing can be accomplished through rich dialogue on problem-posing how do people understand the parts of Earth, as well as holistically, to result in all-Earth inclusive caring that leads to praxis' (Misiaszek Citation2018, 136).

References

- Ajaps, S. 2023. Deconstructing the constraints of justice-based environmental sustainability in higher Education. Teaching in Higher Education 28, no. 5: 1024–38. doi:10.1080/13562517.2023.2198639.

- Assié-Lumumba, N.D.T. 2017. The Ubuntu Paradigm and comparative and international education: Epistemological challenges and opportunities in our field. Comparative Education Review 61, no. 1: 1–21. doi:10.1086/689922.

- Au, W.W., and M.W. Apple. 2007. Reviewing policy: Freire, critical education, and the environmental crisis. Educational Policy 21, no. 3: 457–70. doi:10.1177/0895904806289265.

- Bhaskar, R. 2013. Theorising ontology. In Contributions to social ontology, eds. C. Lawson, J. S. Latsis, and N. M. Ornelas Martins, 206–18. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Bills, H., and S. Klinsky. 2023. The resilience of settler colonialism in higher education: A case study of a western sustainability department. Teaching in Higher Education 28, no. 5: 969–86. doi:10.1080/13562517.2023.2197111.

- Canaparo, C. 2009. Geo-epistemology: Latin America and the location of knowledge. Oxford: Peter Lang.

- Carvalho, I.C.d.M., C.A. Steil, and F.A. Gonzaga. 2020. Learning from a more-than-human perspective. Plants as teachers. The Journal of Environmental Education 51, no. 2: 144–55. doi:10.1080/00958964.2020.1726266.

- Charteris, J. 2014. Epistemological shudders as productive aporia: A heuristic for transformative teacher learning. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 13, no. 1: 104–21. doi:10.1177/160940691401300102.

- Crutzen, P.J., and E.F. Stoermer. 2000. The “Anthropocene”. Global Change Newsletter 41: 17–18.

- Cuenca-Soto, N., L. Fernando Martínez-Muñoz, O. Chiva-Bartoll and M. Luisa Santos-Pastor. 2023. Environmental sustainability and social justice in Higher Education: A critical (eco)feminist service-learning approach in sports sciences. Teaching in Higher Education 28, no. 5: 1057–76. doi:10.1080/13562517.2023.2197110.

- Davies, L. 2006. Global citizenship: abstraction or framework for action? Educational Review 58, no. 1: 5–25. doi:10.1080/00131910500352523.

- Espinet, M., G. Llerena, L. M. Freire dos Santos, S. Lizette Ramos de Robles and M. Massip. 2023. Co-operatives for learning in higher education: Experiences of undergraduate students from environmental sciences. Teaching in Higher Education 28, no. 5: 1005–23. doi:10.1080/13562517.2023.2210078.

- Fanon, F. 1963. The wretched of the earth. New York, NY: Grove Press.

- Freire, P. 1970. Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York, NY: Herder and Herder.

- Freire, P. 2004. Pedagogy of indignation. Boulder, CO: Paradigm Publishers.

- Gadotti, M. 2008a. Education for sustainable development: What we need to learn to save the planet. São Paulo: Instituto Paulo Freire.

- Gadotti, M. 2008b. What we need to learn to save the planet. Journal of Education for Sustainable Development 2, no. 1: 21–30. doi:10.1177/097340820800200108.

- Gadotti, M., and C.A. Torres. 2009. Paulo Freire: Education for development. Development and Change 40, no. 6: 1255–67. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7660.2009.01606.x.

- Gutiérrez, F., and C. Prado. 1989. Ecopedagogia e cidadania planetária. (Ecopedagogy and planetarian citizenship). São Paulo: Cortez.

- Hickman, C., E. Marks, P. Pihkala, S. Clayton, R.E. Lewandowski, E.E. Mayall, B. Wray, C. Mellor, and L. van Susteren. 2021. Climate anxiety in children and young people and their beliefs about government responses to climate change: A global survey. The Lancet Planetary Health 5, no. 12: e863–e873. doi:10.1016/S2542-5196(21)00278-3.

- Iared, V.G., and L.J.V. Hofstatter. 2022. Our SARS-CoV-2 teacher: Teachings of the pandemic about our relations with the more-than-human world. The Journal of Environmental Education 53, no. 2: 117–25. doi:10.1080/00958964.2022.2060174.

- ICA (International Cooperative Alliance). 1995. Cooperative identity, values & principles. Retrieved April 24, 2023 from https://www.ica.coop/en/cooperatives/cooperative-identity.

- Ivo, D. 2022. Reinventando a ecopedagogia: Patriarcado, modernidade e capitalismo. Revista Sergipana de Educação Ambiental 9, no. 1: 1–16. doi:10.47401/revisea.v9i1.18105.

- James, P. 2017. Alternative paradigms for sustainability: Decentring the human without being posthuman. In Reimagining sustainability in precarious times, 1st ed., eds. T. Gray, K. Malone, and S. Truong, 29–44. Singapore: Springer.

- Jimenez, J., and P. Kabachnik. 2023. Indigenizing environmental sustainability curriculum and pedagogy: Confronting our global ecological crisis via Indigenous sustainabilities. Teaching in Higher Education 28, no. 5: 1095–1107. doi:10.1080/13562517.2023.2193666.

- Kinchin, I.M. 2023. Five moves towards an ecological university. Teaching in Higher Education 28, no. 5: 918–32. doi:10.1080/13562517.2023.2197108.

- Koyama, D., and T. Watanabe. 2023. Why a dispositional view of ecological literacy is needed. Teaching in Higher Education 28, no. 5: 1108–17. doi:10.1080/13562517.2023.2193637.

- Le Grange, L.L.L. 2018. The notion of Ubuntu and the (Post)Humanist condition. In Indigenous philosophies of education around the world, eds. J. E. Petrovic, and R. Mitchell, 40–60. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Lin, J., A. Fiore, E. Sorensen, V. Gomes, J. Haavik, M. Malik, S.K. Joanna Mok, J. Scanlon, E. Wanjala and A. Grigoryeva. 2023. Contemplative, holistic eco-justice pedagogies in higher education: From anthropocentrism to fostering deep love and respect for nature. Teaching in Higher Education 28, no. 5: 953–68. doi:10.1080/13562517.2023.2197109.

- Malone, K. 2018. Children in the Anthropocene: Rethinking sustainability and child friendliness in cities. London, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

- McClam, S., and E.M. Flores-Scott. 2012. Transdisciplinary teaching and research: what is possible in higher education? Teaching in Higher Education 17, no. 3: 231–43. doi:10.1080/13562517.2011.611866.

- McCowan, T. 2023. The climate crisis as a driver for pedagogical renewal in higher education. Teaching in Higher Education 28, no. 5: 933–52. doi:10.1080/13562517.2023.2197113.

- Meth, D., C. Brophy, and S. Thomson. 2023. A slippery cousin to ‘development’? The concept of ‘impact’ in teaching sustainability in design education. Teaching in Higher Education 28, no. 5: 1039–56. doi:10.1080/13562517.2023.2198638.

- Misiaszek, G.W. 2018. Educating the global environmental citizen: Understanding ecopedagogy in local and global contexts. New York, NY: Routledge. https://www.routledge.com/Educating-the-Global-Environmental-Citizen-Understanding-Ecopedagogy-in/Misiaszek/p/book/9781138700895.

- Misiaszek, G.W. 2020a. Ecopedagogy: Critical environmental teaching for planetary justice and global sustainable development. London, UK: Bloomsbury. www.bloomsbury.com/uk/ecopedagogy-9781350083813.

- Misiaszek, G.W. 2020b. Ecopedagogy: teaching critical literacies of ‘development’, ‘sustainability’, and ‘sustainable development’. Teaching in Higher Education 25, no. 5: 615–32. doi:10.1080/13562517.2019.1586668.

- Misiaszek, G.W. 2022a. Reinventing: Essence and usefulness of Freire’s work for the past and next 100 years*. Educational Philosophy and Theory 54, no. 13: 2153–59. doi:10.1080/00131857.2022.2144222.

- Misiaszek, G.W. 2022b. What cultures are being reproduced for higher education success?: A comparative education analysis for socio-environmental justice. International Journal of Educational Research 116: 102078. doi:10.1016/j.ijer.2022.102078.

- Misiaszek, G.W., L.I. Jones, and C.A. Torres. 2011. Selling out academia? Higher education, economic crises, and Freire’s generative themes. In Universities and the public sphere: Knowledge creation and state building in the era of globalization, eds. B. Pusser, K. Kempner, S. Marginson, and I. Ordorika, 179–196. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Misiaszek, G.W., and C. Rodrigues. 2023. Six critical questions for teaching justice-based environmental sustainability (JBES) in higher education. Teaching in Higher Education 28, no. 1: 211–19. doi:10.1080/13562517.2022.2114338.

- Misiaszek, G.W., and C.A. Torres. 2019. Ecopedagogy: The missing chapter of Pedagogy of the Oppressed. In Wiley handbook of paulo freire, ed. C. A. Torres, 463–88. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Morrow, R.A. 2019. Paulo Freire and the “logic of reinvention”: Power, the state, and education in the global age. In Wiley handbook of Paulo Freire, ed. C. A. Torres, 445–62. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Morrow, R.A., and C.A. Torres. 2019. Rereading Freire and Habermas: Philosophical anthropology and reframing critical pedagogy and educational research in the neoliberal anthropocene. In Wiley handbook of Paulo Freire, ed. C. A. Torres, 241–74. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Nakagawa, Y., and P.G. Payne. 2019. Postcritical knowledge ecology in the Anthropocene. Educational Philosophy and Theory 51, no. 6: 559–71. doi:10.1080/00131857.2018.1485565.

- Payne, P.G. 2016. The politics of environmental education. Critical inquiry and education for sustainable development. The Journal of Environmental Education 47, no. 2: 69–76. doi:10.1080/00958964.2015.1127200.

- Payne, P.G. 2018. The framing of ecopedagogy as/in scapes: Methodology of the issue. The Journal of Environmental Education 49, no. 2: 71–87. doi:10.1080/00958964.2017.1417227.

- Payne, P.G. 2020. Amnesia of the moment” in environmental education. The Journal of Environmental Education 51, no. 2: 113–43. doi:10.1080/00958964.2020.1726263.

- Payne, P.G., and C. Rodrigues. 2012. Environmentalizing the curriculum: A critical dialogue of south-north framings. Perspectiva 30, no. 2: 411–44. doi:10.5007/2175-795X.2012v30n2p411.

- Rodrigues, C. 2018. MovementScapes as ecomotricity in ecopedagogy. The Journal of Environmental Education 49, no. 2: 88–102. doi:10.1080/00958964.2017.1417222.

- Rodrigues, C. 2020. What’s new? Projections, prospects, limits and silences in “new” theory and “post” North-South representations. The Journal of Environmental Education 51, no. 2: 171–82. doi:10.1080/00958964.2020.1726267.

- Rodrigues, C., and G. Lowan-Trudeau. 2021. Global politics of the COVID-19 pandemic, and other current issues of environmental justice. The Journal of Environmental Education 52, no. 5: 293–302. doi:10.1080/00958964.2021.1983504.

- Rodrigues, C., P.G. Payne, L.L. Grange, I.C.M. Carvalho, C.A. Steil, H. Lotz-Sisitka, and H. Linde-Loubser. 2020. Introduction: “New” theory, “post” North-South representations, praxis. The Journal of Environmental Education 51, no. 2: 97–112. doi:10.1080/00958964.2020.1726265.

- Santos, B.d.S. 2014. Epistemologies of the South: Justice against epistemicide. Boulder, CO: Paradigm Publishers.

- Santos, B.d.S. 2018. The end of the cognitive empire: The coming of age of epistemologies of the South. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press.

- Solórzano, D.G., and T.J. Yosso. 2002. Critical race methodology: Counter-storytelling as an analytical framework for education research. Qualitative Inquiry 8, no. 1: 23–44. doi:10.1177/107780040200800103.

- Stein, S., V. Andreotti, C. Ahenakew, R. Suša, W. Valley, N. Huni Kui, M. Tremembé, et al. 2023. Beyond colonial futurities in climate education. Teaching in Higher Education 28, no. 5: 987–1004. doi:10.1080/13562517.2023.2193667.

- Takayama, K., A. Sriprakash, and R. Connell. 2017. Toward a postcolonial comparative and international education. Comparative Education Review 61, no. S1: S1–S24. doi:10.1086/690455.

- Tierney, R.J. 2018. Toward a model of global meaning making. Journal of Literacy Research 50, no. 4: 397–422. doi:10.1177/1086296X18803134.

- Torres, C.A. 2022. Paulo Freire: Voices and silences. Educational Philosophy and Theory 54, no. 13: 2169–79. doi:10.1080/00131857.2022.2117028.

- Turnbull, D. 2000. Masons, tricksters, and cartographers: Comparative studies in the sociology of scientific and indigenous knowledge. London, UK: Routledge.

- Ulmer, J.B. 2017. Posthumanism as research methodology: Inquiry in the Anthropocene. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education 30, no. 9: 832–48. doi:10.1080/09518398.2017.1336806.

- Warren, K.J. 2000. Ecofeminist philosophy: A Western perspective on what it is and why it matters. City: Rowman & Littlefield Publications.

- Young, T.C., and K. Malone. 2023. Reconfiguring environmental sustainability education by exploring past/present/future pedagogical openings with preservice teachers. Teaching in Higher Education 28, no. 5: 1077. doi:10.1080/13562517.2023.2197112.