ABSTRACT

We turn a critical lens to ethical research practices in the context of ‘insider’ higher education research. Tensions arise due to the risks involved in navigating academic identity and teacher-researcher authenticity. We offer two case studies where ethical tensions surfaced methodological concerns for researchers and participants. Case study one describes hesitation precipitated by the risk of academic participant self-disclosure. Hesitation in case study two arose through the secondary use of student evaluation data for research purposes and possible reputational risk of teaching academics. We offer a reflective analytical process to map researchers and participants within the research to describe ethical complexity. We drew on three feminist principles useful in higher education research to mitigate ethical tensions, for example, the concept of a ‘culture of care’, a recognition of emotional labour, and negotiated roles to mitigate against improper power imbalances. We advocate for adopting a dynamic approach to ethical practices in higher education research thereby reframing the insider role.

Introduction

Undertaking research requires transparent compliance with national ethical standards to ensure study participant interests are prioritised and addressed at the outset of each research project. We present an inherently reflective investigation that explores ethical challenges experienced in higher education ‘insider’ research (Trowler Citation2012; Clegg, Stevenson, and Burke Citation2016) where academic colleagues and students are study participants. We offer due consideration to our national context (i.e. Australia) where the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC Citation2023) set ethical standards and protocols and directs practices to consider participant vulnerabilities within research spaces as ethical spaces of engagement.

We turn a critical lens to learning and teaching practices and processes within the higher education research frame that expose researchers, academic staff participants and institutional vulnerabilities. We offer two case studies from our own research practices where the complexities of the relationships between researcher and study participants presented ethical challenges, which evoked the need to expend emotional labour (Bartos and Ives Citation2019; Tunguz Citation2016). Using an analytical process of reflection common in qualitative ethnographic approaches, we identified researcher and participant tensions expressed as vulnerabilities and risks. To resolve expressed tensions we adopted the notion of ‘a culture of care’ into our research practices as advocated by Gabrielle King (Citation2023), and by extension, we considered the expenditure of emotion labour required to manage study participant and researcher vulnerabilities. Principles of power and identity drawn from feminist research practice (Hesse–Biber Citation2013) were adopted to analyse and transform our highly relational ‘insider' research spaces towards a better understanding of the ethical spaces of ‘insider' research through a heightened ‘culture of care’.

Research from the inside perspective

Qualitative, reflexive, ‘insider’ research methodologies are often termed ‘close-up’ as the ‘insider’ performs a style of ethnography ‘to get relatively close to the meanings, ideas, discursive and/or social processes of a group of people’ (Alvesson Citation2023, 168). Such closeness in the research space and across a community of participants aims to open ways to deeply observe phenomena rich in culture, context, time, and space and offers the means to explore the intersections of identity, lived experiences, and the working environment (Faulkner and Thompson Citation2023).

In the context of research into higher education, participants include students and staff (professional and academic), and it is not unusual for the researcher and the participants to be inside the same institution. Research focused on academics researching their peers has been described as ‘insider’ with considerable discourse about the tensions that arise through identity threats to self, participants, and the research location (Trowler Citation2012; Clegg, Stevenson, and Burke Citation2016). The term ‘insider’ research is used less often when our students are the subjects of research. A subset of research in higher education is termed the ‘scholarship of teaching and learning’ which has its own specific theoretical frameworks and methodologies. Like all scholarship, there are human and social ethical requirements (Healey et al. Citation2013) due to the relational and reflective nature of researching one’s own practice in a cultural and social context.

The research ‘tales' constructed from those participating on the inside of an institution or community aim to reveal first-hand experiences. An ethically bound research tale offers authenticity and originality through a process of consent, respect and reciprocity akin to an agreement between all parties. Where the researcher has been afforded an ‘insider’ status for conducting close-up research, the researcher is also in the research space and within research relationships. Protecting participant identities whilst remaining true to the ethics of the data can lead to a crisis of authentic representation (Flaherty et al. Citation2002). A common practice in educational research is to use pseudonyms to protect the real identity of participants to mitigate risks of potential harm or retributions to study participants.

Research governance

In many national contexts there are governing bodies that set ethical standards and guidelines to mitigate research risks where interviews, surveys, participant observation and focus groups are commonly used data collection methods when researching in the higher education sector. Describing how ethical standards will be met in a research project proposal is required where human participant data is being sought. In our national context, Australia, the NHMRC is the statutory body on ethical human research, which includes education research, and this body offers a National Statement on Ethical Conduct of Human Research that is revised regularly (NHMRC Citation2023). Ethical compliance can be viewed as meeting the NHMRC standards by protecting study participants from harm, including psychological or emotional harm. The remit of those charged with evaluating research projects for approval includes an expectation that researchers anticipate potential ethical tensions in the context of their studies when ethical guidelines are applied in practices.

Researching into the higher education workplace can be ethically complex for the ‘inside’ researcher where the notion of harm (Radloff et al. Citation2012) must be addressed in its' complexity. For example, the emergent field of ‘academic identities’ in higher education (Billot Citation2010) has legitimised examinations of insider research into the dynamism of our academic selves and our institutional ecosystems. The case studies offered below sit in this dynamic space and were explored through a reflective analytical process of identifying tensions. The nature of this research is compelling due to its relational complexity, contributions to scholarly discourses, and potentially ‘telling tales out of school’.

The ethical space of engagement

The concept of ethical space was introduced by Poole (Citation1972) who focused on the role that intention plays when people engage with each other. For example, when two sets of intentions arising from each person or party in an engagement confront each other, the ethical space is set up instantaneously. Within this space there are overt and hidden subjectivities and biases, thoughts, interests, and assumptions that will inevitably influence and animate the forms of engagement between the two people or parties (Bohm Citation1996). Jessie King (Citation2023) suggests the ethical space is where we perceive ‘what is’ about people, (their biographies and histories), and contains our respective epistemologies, ontologies, cultures, and communities.

Cree scholar Dr Willie Ermine (Citation2007), an ethicist, draws on the idea of ethical space of engagement when aiming to position Indigenous peoples and Western society to discuss Indigenous legal issues through the fragile intersection of Indigenous law and Canadian legal systems. According to Ermine,

The ethical space is formed when two societies, with disparate worldviews, are poised to engage each other. It is the thought about diverse societies and the space in between them that contributes to the development of a framework for dialogue between human communities. (Citation2007, 193)

Social science research and human ethics are conducted in the spaces between people, where beliefs, notions, values, stereotypes, biases, and even racist or discriminatory thoughts exist (Ermine Citation2007). The ethical space may be exclusive to the researcher or co-designed with participants dependent on research designs and methodology. Dhillon and Thomas (Citation2019) suggest that researchers represent differing degrees of ‘insider’-ness, which reflects the realities of multiple researcher positionalities, interpretations, and power relations.

The paradox of confidentiality

The agency and autonomy of the researcher informs decisions regarding what to disclose about study participants and what not to disclose. Such decisions point to disclosure dilemmas in the higher education academy and are particularly evident within participatory and action-oriented ‘insider’ research. At the same time, there are questions as to whether methodological protocols and ethical obligations can assure absolute confidentiality at all times and for all participants. For example, in academic identity research by academics on their self–constructed identity stories of colleagues, commonalities in experiences and earlier shared experiences influence the research space, which is where roles shift from being primarily collegial to being ‘researcher' and ‘participant’. Existing or prior relationships can pose a risk to current relationships in the research space, which may be crucial for ethnographic studies in higher education.

The crisis of representation mentioned earlier (Flaherty et al. Citation2002) surfaces when researching legitimate stories of participant lived experiences are reported or represented under traditional ethical protocols for anonymity. Ethnographic researchers have been questioning their authoring authority in this crisis through critical self-reflexivity on researcher ethical objections and methodological frontiers (Rabinow Citation1986; Denzin and Lincoln Citation1994). Interpretive authority is one practice in qualitative social science research which uses thematic analysis, collective biography, or collective autoethnography to get around the crisis of representation. However, in the context of studies exploring the diversity of self–reported identity constructions reliant on individual lived experiences, researcher interpretive authority may not be enough, and could be ethically unsafe.

Feminist relational ethics support a culture of care

Feminist scholars have contributed to discussions on ethics and methods involved in conducting research and generating knowledge to inform teaching, learning and research into higher education. Wigginton and Lafrance (Citation2019) suggests how we engage in research flows from one’s epistemological commitments about ‘what’ and ‘how’ we know, and ‘who’ can know, which are fundamental considerations in research.

For example, feminist thought advocates for equality in research relationships (Millen Citation1997) and puts the social construction of gender at the centre of inquiry (Lather Citation1998). For the research to be empowering for participants, feminist ethics advocate for inclusive practices which support safety in participation, ways of honouring authentic voices, declaring ongoing positionality, and respecting forms of intersectionality. When mitigating power imbalances, a researcher can attempt to suspend forms of authorial, cultural or personal power in research, despite acknowledging that a researcher role signifies certain privileges. We posit that there are additional costs to the ‘insider’ researcher when establishing a culture of care for all particpants, and when expending emotional labour in reconciling tensions that may arise (Bartos and Ives Citation2019).

Case studies: ethics in practice

In the context of resolving ethical tensions outlined above, we offer two case studies based on ‘insider' research that feature emotional labour. The case studies offered here describe tensions in the ethical space of engagement between researcher and participants in the context of higher education ‘insider' research. The first case study was reliant on gathering data from academic staff, and the second one was reliant on accessing data from course surveys (or students' evaluations of teaching). Both case studies identify the sources of ethical tension and describe changes to the research process to resolve these tensions. Each case demonstrates where standard ethical principles are not without identity threats and defamation risks to individuals and/or the institution. Our analytical process involved mapping the research space and positioning the research lead and participants in relation to each other within the research space, and to define the nature of the research tension. In light of the case studies, we call for reflection and action on two points: firstly, a renewed view of ethical sensitivity (King 2023) in higher education ‘insider' research to better assure participant and researcher safety by employing the culture of care in our practices, and secondly, to debunk ‘insider’ research which can be ethically fraught and promotes binary researcher and participant roles.

Case study 1: truth-telling and telling tales

This case study is a retelling of experiences encountered in doctoral research investigating factors that shape identity formation of academic staff in higher education. A small study aimed to surface stories of lived experiences which explored the ways in which academics shaped their identities by identify with their teaching and research. Formal ethics approval supported a qualitative, ethnographic methodology with data gathered through in-depth, semi-structured interviews and particpant observation. Building on existing relationships and creating new relationships was profitable for recruitment. Within interviews, there was an emphasis on authenticity in the narratives offered.

Two prominent voices were evident in the study, the first came from the lived experience of a doctoral researcher, and the second represented the research participants and their stories. Emergent across both, was evidence of positional and personal ethical tension due to the clash between authentic stories, which in their raw state, reveal the actual identities of participants. The researcher-participant relationship is complex and, as Bell (Citation2019) suggests the ethnographic researcher enacts multiple roles to build relationships and deploy procedural ethics in practice.

Tensions between ethics and methods

The context of a small-scale study within a single faculty at the same institution required an adjustment to the ethics and methods due to:

positioning of the researcher as a student and employee at the university which was the study site; and

closeness due to the nature of the study on academic identities from an ethnographic approach where lived experience narratives were based on trusting research relationships. Relational strain was experienced by the researcher when challenged to uphold participant anonymity.

Ethics and methods are known to come together within the data interpretation stage in qualitative, ethnographic research where lived experiences reside within a context, time, and place. Analysing qualitative interviews involved a reflexive review process (Ploder Citation2022) of sifting through researcher notes and relistening to audio recordings to identify the commonalities across stories, and the points of individual distinction. For the researcher, an objective distancing from the participants and their data during analysis honors ethical arrangements of upholding anonymity. At the same time, closeness in this study became risky when ensuring the relationships developed with participants when collecting and analysing data were left undamaged.

Questioning interpretative authority on the part of the researcher has been illustrated by Borland (Citation1991) who claimed that in narrative oral history research the researchers are faced with a data handling contradiction. Do you maintain the originality of a narrative, or iterate when retelling a story, or interpret the data into themes through a schema? In this case study, the data was amplified to locate indicative patterns of self-reported identity constructions within each participants’ data set and across participant stories. Ethical sensitivities arose regarding upholding the originality of the narratives (which can be anonymized, but true tales contain potentially revealing data) and/or interpreting the stories for a public audience (which can also be anonymised but risks fabricating the data into ‘telling tales’).

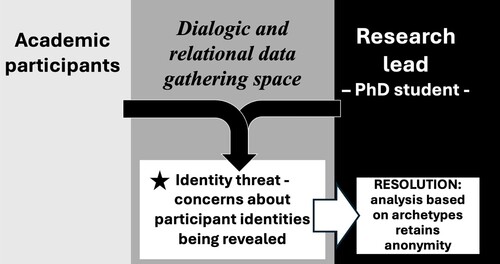

Resolution: finding voice through narrative ethics

Despite institutional ethics in hand, responding to these ethical and authoring sensitivities was required to proceed with due diligence and safety. A caring research protocol was introduced where all participants, their voices and stories felt safe and the data was safely handled with respect. Maintaining authentic relationships with people and their data may not be straightforward and requires interpretive skills to find suitable modalities to share research findings. below visually depicts the highly relational ‘insider’ research space felt by this ‘insider’ researcher in higher education. Strategies to progress the project included (re)building trust and addressing identity threat through two actions:

Applying Jung’s (Citation2014) schema as a semi-fictionalised interpretative approach to surface identity constructions through archetypes while retaining anonymity. Examples were The Sage, Trickster, and Carer (Lewis and Quinnell Citation2022).

Declaring the ‘inside’ researcher’s lived experiences and actions through critically reflexive auto-ethnographic writing as data.

Figure 1. Case study 1 describes an ‘insider’ research scenario where the research lead, a PhD student (dark grey), creates a dialogic data gather space (dotted) and invites academic study participants, many of whom were senior academic staff (light grey), to join her (arrows) to gather participant perceptions (data) of how research and teaching are enacted in a large research-intensive university. Ethical discord surfaced with concerns that the highly individual nature of a subset of participant data (white box, bottom middle) would expose study participants (black star). This led to a period of inertia as the research lead contemplated and reflected on how to proceed with data analysis. Data analysis employed archetypes to represent participants which allowed participant identities to remain hidden/obscured and the research to progress (white box, bottom right side).

Case study 2: teacher agency in student evaluation and education research

This case study focuses on the contentious nature of analysing student evaluation response data from (secondary) research purposes. There is no doubt that student response data are rich sources of information. The introduction of learning and teaching evaluation systems are not only meant to improve university teaching practices and learning experiences, but to elevate the value and status of teaching within research-intensive institutions. Repurposing these data for research purposes which will be available publicly raises ethical concerns.

Student evaluation instruments were designed to gather information from students on how a course could be improved. In the context of this case study, the survey instrument offered statements focused on how students were learning (e.g. learning activities focused on critical thinking, fostering effective learning communities), that is, their perceptions of course elements (resources, assessments, activities). The survey also included statements focused on the teachers and their teaching, responses to which are intended to encourage reflection of teaching practice by individual educators. These kinds of evaluations are often referred to as course evaluations or student evaluation of teaching with SET being the usual abbreviation in the literature. Student response data takes the form of open-ended responses and level of agreement to these statements (Likert-scale). Inference can be drawn from analysing student responses to assess the strength of constructive curriculum alignment between learning objectives, learning activities, assessment, and approaches to teaching (Biggs Citation1996). The systematic employment of SET data to continuously improve curricula has become foundational to scholarly teaching and learning practice.

As described here, the primary analysis of student response data is undertaken by individual subject coordinators. However, subsequent evaluations are undertaken by line-supervisors of teaching staff and by those within institutions who are charged with providing reports for governments audits. What was once a system to facilitate reflective teaching practices has become, (1) the means to manage individual staff within the institution, and (2) for government, the means to manage institutions. This drift of intent to staff management uncouples specific contexts of teaching spaces from the data and unless the teacher is party to any on-going discussion, this practice can diminish the agency of the teacher. Diminished agency is of particular importance for women and those in marginalised groups due to prejudice and bias that plays out as lower student evaluation scores (Boring, Ottoboni, and Stark, Citation2016; Heffernan Citation2022; Uttl and Smibert Citation2017) and because of this there is strong opposition to using SET data to manage staff. Gender, race, and class not only play into how students offer their SET Likert scores but women and those in marginalised groups are subjected to higher levels of abusive comments in the open-ended response data (Heffernan Citation2023).

Tensions between evaluation versus research

Within the context of the case study, there are several tensions. The first surfaced when considering the tension between data when categorised as ‘evaluation’, and data categorised as ‘research’, noting that even if the data sets in question are identical, there is a difference in who is telling the tale when the purpose is evaluation compared with who is telling the tale when the purpose is research.

A key difference between evaluation and research is who picks up the story post-data collection, the degree of the analyses being tied to hypotheses, and who the teller is speaking to. Evaluations are largely ‘ahypothetical’ investigations (Booth Citation2009) and are ‘important for determining the extent to which a policy has met or is meeting its objectives and that those intended to benefit have done so’ (UK National Audit Office Citation2001, 14).

In this case study students participating offer their data anonymously and voluntarily. The timing of data collection is close to the end of semester, and the data are released back to unit coordinators after final marks are released so that there is no chance of teacher retribution for students’ negative scores and comments. It is unclear if students would respond differently to surveys if they knew their data were used for both evaluation and research, however there is some commentary that students are aware that data are used for promotion purposes and that offering comments is a means to enact retribution on teachers (Brown Citation2008). Suffice to say, that the veil of anonymity is a means for students to retain their agency either way. There is no mechanism for continued discourse with participants, however, there may be options for unit coordinators to offer a general statement back to students as to what changes their comments have initiated.

With respect to evaluation, whilst unit coordinators may undertake robust analyses to compare data across years as part of reflective practice, the audience for these analyses is small and sits inside the institution. Conversely, for formal audits to comply with government funding obligations, the audience for audit reports based on highly aggregated data sets across multiple courses is large and covers both those within and outside of the organisation. Within the institution, comparisons of trends across annual data sets, and across faculties feature. Although statistical analysis may be undertaken, rarely are statistical analysis offered to support inferences when data are being reported back to teachers within the institution.

The audience for research is members of the broad scholarly community with the researchers on the project doing the telling. Along with the scholarly framing of the project, methodological approaches, data collection, and subsequent analyses are expected to be robust and accepted by peers, and ethical practice is a consideration of peers charged with reviewing manuscripts for publication. The SET survey instrument contains items to assess students’ perceptions of their learning and of teaching quality. As described above, when analysed by researchers, the data generated by student evaluation data sets is very useful to reveal levels of bias towards teachers who are women and members of marginalised groups. If it were not for the damaging comments in the open-ended response fields that render teachers in marginalised groups more vulnerable to reputational risks, offering these data sets for further scholarly interrogation would likely tell us more about the challenges of working in higher education.

The sticking points were identified as:

potentially exposing teaching staff to reputational risk through unethical sharing of open-ended response data, and

the lack of teacher agency in determining how student response data is interpreted.

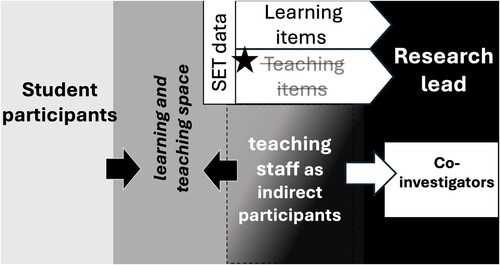

Resolution: giving voice through culture of care

In this case study, re-establishing teacher agency was the strategy use to resolve the ethical impasse of uncoupling teacher input in interpreting the data, allowing research momentum to resume. This was achieved in two ways:

those SET items aligned with assessing ‘teaching’ were to be excluded from data set available for research purposes. In this way, the primary researcher would not be privy to any damaging comments by students and so an avenue of potential reputation risk is blocked. This approach confers a level of security to teaching staff that these data have not been permeated in the research domain and focused on those specific SET items with research value. Items selected for research are offered in . All SET items were aligned with the learning objectives of the courses under examination by the project, and all student learning objectives, and unsurprisingly all were able to be covered in learning-focused subset of SET items.

inviting teachers who had taught into the course to become partner researchers on the project. This part of the solution recognises the emotional labour involved in teaching. Being able to continue the discourse within a research framework confers opportunities for teachers to extend their culture of care from the domain of teaching to include that of research. Ensuring the agency of the teacher, who is both content and context expert (i.e. they know the nuances of specific learning and teaching spaces), and then expanding this agency as a voice in the research is expected to enrichen the ways student learning response data are deciphered and told. depicts the learning and teaching space shared by teachers and students and where the SET data is generated. The two aspects of the resolution of this learning and teaching space with the research space are highlighted.

Figure 2. Case study 2 describes a scenario where curriculum evaluation data was being proposed for use as secondary research data. The space being evaluated is a learning and teaching space (grey) where students (lightest grey, left side) and teachers (darker grey, right side) come together (black arrows), making students direct study participants, and teachers indirect study participants. The research lead (dark grey, right side) resides outside of the learning and teaching space. At the end of semester, the anonymous student evaluation of teaching (SET) data are gathered. There data contains items to assess how well students perceived the course and includes items about the teaching has the potential for teacher identities to be exposed (black star) which could not only lead to reputational risk, but this impacts their agency in determining how the data about their teaching practices are used. To enable this project to proceed, two measures were employed (white box strikethrough top middle, white box bottom right): (a) only the SET data of value to the research were to be used and (b) teaching staff were to be invited to partner on the research as co-investigators.

Table 1. Student survey of evaluation of learning and teaching statements.

The power of championing agency of teachers, particularly women and those in marginalised groups in this way offers a novel partnership mechanism to affect systemic and cultural change in academia (Bayne and Dopico Citation2020).

Concluding remarks

We consider that ‘insider’ research into higher education involves a level of intimacy between the researcher and study participants and consideration needs to be employed when all are working within the same sector, the same institution, and/or be co–workers in the same organisational unit. Ethnographic research approaches adopted in higher education settings are built on trust, reciprocity, and the honouring of ‘rightful voice’ established through relational and interpersonal methods.

The interplay of ethical arrangements and research practices in social science research creates a focus on the ethical space of engagement occupied by both researchers and participants. Ethical arrangements and research protocols need to be tailored to increasingly collaborative practices, and in some cases, when seeking authentic truth-telling on lived experiences (Eaton and Robbins Citation2023). Our case studies described ethical tensions where decisions to revise ethical arrangements through a stronger culture of care in our research practices emerged.

Our analytic reflective process has brought together feminist research principles, the culture of care, and has recognised that emotional labour may be witnessed and/or experienced within the ‘insider’ role. Mapping the research space allowed for due consideration of our positionality and agency as inside researchers and that of our academic colleagues as study participants (case study one), or indirect participants (case study two). We advocate for adopting a dynamic approach to strengthening ethical practices including ongoing negotiations supporting a feminist culture of care, which is where participants have opportunities to take on the role of researcher in addition to participant, and can be achieved by:

Creating a collective, caring community of scholars where safety and equity issues when studying other people, their behaviours, and self-expressed lived experiences can occur.

Repositioning researchers based on circumstances, which requires negotiation and self-control when operating at the edges of academic practices.

Depositioning educational researchers as a sole authority by portraying the equitable and relational nature of research into higher education.

Creating ways for additional roles to co-exist, which allows for a multiplicity of voices to be represented through adoption of auto-ethnographic methods.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Alvesson, M. 2023. Methodology for close up studies – struggling with closeness and closure. Higher Education 46: 157–93.

- Bartos, A.E., and S. Ives. 2019. 'Learning the rules of the game': Emotional labor and the gendered academic subject in the United States. Gender, place and culture: a journal of feminist geography 26, no. 6: 778–94. doi:10.1080/0966369X.2018.1553860.

- Bayne, G.U., and E. Dopico. 2020. Pedagogical challenges involving race, gender and the unwritten rules in settings of higher education. Cultural Studies of Science Education 15, no. 3: 623–37. doi:10.1007/s11422-020-09972-w.

- Bell, K. 2019. The ‘problem’ of undesigned relationality: Ethnographic fieldwork, dual roles and research ethics. Ethnography 20, no. 1: 8–26. doi:10.1177/1466138118807236.

- Biggs, J. 1996. Enhancing teaching through constructive alignment. Higher Education 32, no. 3: 347–64. doi:10.1007/bf00138871.

- Billot, J. 2010. The imagined and the real: Identifying the tensions for academic identity. Higher Education Research & Development 29, no. 6: 709–21. doi:10.1080/07294360.2010.487201.

- Bohm, David. 1996. On dialogue. Edited by L. Nichol. London: Routledge.

- Booth, A. 2009. Research or evaluation? Does it matter? Health Information & Libraries Journal 26, no. 3: 255–8.

- Boring, A., K. Ottoboni, and P.B. Stark. 2016. Student evaluations of teaching (mostly) do not measure teaching effectiveness. ScienceOpen research. doi:10.14293/S2199-1006.1.SOR-EDU.AETBZC.v1.

- Borland, K. 1991. That’s not what I said: Interpretive conflict in oral narrative research. In Women’s Words: The feminist practice of oral history, eds. S. Gluck, and D. Patai, 63–74. New York: Routledge.

- Brown, M.J. 2008. Student perceptions of teaching evaluations. Journal of Instructional Psychology 35, no. 2: 177–82.

- Clegg, S., J. Stevenson, and P.-J. Burke. 2016. Translating close-up research into action: A critical reflection. Reflective Practice 17, no. 3: 233–44.

- Denzin, N.K., and Y.S. Lincoln. 1994. Handbook of qualitative research, edited by N. K. Denzin and Y. S. Lincoln. New York: Sage Publications, Inc.

- Dhillon, J.K., and N. Thomas. 2019. Ethics of engagement and ‘insider’-outsider perspectives: Issues and dilemmas in cross-cultural interpretation. International Journal of Research & Method in Education 42, no. 4: 442–53. doi:10.1080/1743727X.2018.1533939.

- Eaton, P.W., and K. Robbins. 2023. Practicing truth-telling inquiry: Parrhesia in daily lived experiences. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 1–13. doi:10.1080/00131857.2023.2183118.

- Ermine, W. 2007. The ethical space of engagement. Indigenous Law Journal 6, no. 1: 193–203.

- Faulkner, A., and R. Thompson. 2023. Uncovering the emotional labour of involvement and co-production in mental health research. Disability & Society 38, no. 4: 537–60. doi:10.1080/09687599.2021.1930519.

- Flaherty, M.G., N.K. Denzin, P.K. Manning, and D.A. Snow. 2002. Review symposium: Crisis in representation. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography 31, no. 4: 478–516. doi:10.1177/0891241602031004004.

- Healey, R.L., T. Bass, J. Caulfield, A. Hoffman, M.K. McGinn, J. Miller-Young, and M. Haigh. 2013. Being ethically minded: Practising the scholarship of teaching and learning in an ethical manner. Teaching and learning inquiry 1, no. 2: 23–33.

- Heffernan, T. 2022. Sexism, racism, prejudice, and bias: A literature review and synthesis of research surrounding student evaluations of courses and teaching. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 47, no. 1: 144–54. doi:10.1080/02602938.2021.1888075.

- Heffernan, T. 2023. Abusive comments in student evaluations of courses and teaching: The attacks women and marginalised academics endure. Higher Education 85, no. 1: 225–39. doi:10.1007/s10734-022-00831-x.

- Hesse–Biber, S.N. 2013. Feminist research practices: A Primer. 2nd Ed. Los Angeles: Sage.

- Jung, C.G. 2014. Conclusion aion: Researches into the phenomenology of the self. In Collected works of C.G. Jung, ed. G. Adler and R.F.C. Hull, Vol. 9 Part 2. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- King, J. 2023. Indigeneity, positionality, and ethical space. navigating the in-between of indigenous and settler academic discourse. Papers on Postsecondary Learning and Teaching 6: 36–48.

- King, G. 2023. Towards a culture of care for ethical review: Connections and frictions in institutional and individual practices of social research ethics. Social & Cultural Geography 24, no. 1: 104–20. doi:10.1080/14649365.2021.1939122.

- Lather, P. 1998. Critical pedagogy and its complicities: A praxis of stuck places. Educational Theory 48: 487–98.

- Lewis, M., and R. Quinnell. 2022. Marginalising imposterism: An Australian case study of personal, participant and practice narratives that frame academic identities. In The Palgrave handbook of imposter syndrome in higher education, edited by Michelle Addison, Maddie Breeze, and Yvette Taylor, 91–106. Cham: Springer International Publishing..

- Millen, D. 1997. Some methodological and epistemological issues raised by doing feminist research on non-feminist women. Sociological Research On-line 2, no. 3: 114–28.

- National Health and Medical Research Council. 2023. The national statement on ethical conduct in human research 2023. In. Commonwealth of Australia. Canberra: National Health and Medical Research Council, the Australian Research Council and Universities Australia.

- Ploder, A. 2022. Strong reflexivity and vulnerable researchers. On the epistemological requirement of academic kindness. Queer-Feminist Science & Technology Studies Forum 7: 25–38.

- Poole, R. 1972. Towards deep subjectivity. London: Allen Lane the Penguin Press.

- Rabinow, P. 1986. Representations are social facts: Modernity and post-modernity in anthropology. In Writing culture: The poetics and politics of ethnography, 239., 234–61. University of California Press.

- Radloff, A., H. Coates, R. Taylor, R. James, and K.-L. Krause. 2012. 2012 university experience survey national report. In.: Department of Industry, Innovation, Science, Research and Tertiary Education.

- Trowler, P. 2012. Doing insider research into higher education. Amazon Kindle. ISBN B006JI3SGK.

- Tunguz, S. 2016. In the eye of the beholder: Emotional labor in academia varies with tenure and gender. Studies in higher education (Dorchester-on-Thames) 41, no. 1: 3–20. doi:10.1080/03075079.2014.914919.

- UK National Audit Office. 2001. Modern policy-making: Ensuring policies deliver value for money: report. In, edited by UK National Audit Office. London: UK National Audit Office.

- Uttl, B., and D. Smibert. 2017. Student evaluations of teaching: Teaching quantitative courses can be hazardous to one’s career. PeerJ 5: e3299. doi:10.7717/peerj.3299.

- Wigginton, B., and M.N. Lafrance. 2019. Learning critical feminist research: A brief introduction to feminist epistemologies and methodologies. Feminism & Psychology. doi:10.1177/0959353519866058.