ABSTRACT

This paper focuses on the potential, challenges, and limits of participatory, narrative and multimodal research methods as contributions to decolonising research on understanding student experiences of teaching and learning in higher education. Drawing on Fraser’s social justice concepts of participatory parity, redistribution, recognition, and representation, we argue that methodologies and methods for researching students’ experiences need to redress power imbalances implicit in many existing approaches. We suggest how participatory methodologies can be combined with narrative inquiry and multimodal methods where students research their own lives and contexts. We critically reflect on an international study based in South Africa with South African and UK partners involving 65 undergraduate students from rural backgrounds who participated as co-researchers over 12 months. We highlight decolonial debates in relation to participatory research, before outlining our methodological approach and interrogating the potential, limitations, and future possibilities of co-researcher methodologies for decolonising student-focused research in higher education

Introduction

This paper focuses on the potential, challenges, and limits of participatory, narrative and multimodal research methods as contributions to decolonising research on student experiences of teaching and learning in higher education. Much higher education research is concerned with social justice and the eradication of inequalities, including addressing colonial legacies and the need to dehegemonise colonial knowledge in general, and understandings of students’ experiences of teaching and learning more specifically (Leibowitz Citation2017b). This has resulted in calls for decolonising approaches to generating knowledge on student experiences of teaching, learning and assessment, as well as the wider university culture and context (Mbembe Citation2016; Connell Citation2017). Developing new approaches to researching higher education issues, especially those that focus on students’ experiences of teaching and learning, is a critical, emerging element of the decolonisation agenda (Martinez-Vargas Citation2020; Hayes, Luckett, and Misiaszek Citation2021). In this paper, we argue that research methodologies and methods for investigating our understandings of students’ experiences of teaching and learning are especially critical in contexts where many research methodological approaches often seek to extract and appropriate knowledge from indigenous communities, thereby creating implicit power imbalances (Smith Citation2012).

Drawing on an extensive methodological review, Tight (Citation2013; Citation2018) argues that higher education researchers have historically tended towards reliance on standard methods such as interviews, surveys, and documentary analyses. More recently, there has been more methodological diversification and innovation, especially in relation to teaching and learning (see for example Briffett Aktaş Citation2021; Timmis and Muñoz-Chereau Citation2022; Trahar Citation2011) as our paper will show, even though participatory methodologies have been employed in many disciplines (see for example Reason Citation1994), they continue to be less prevalent in higher education. Action research and participatory action research (PAR) both have their roots in co-operative inquiry, where research is undertaken ‘with people, not on them or about them’ (Heron Citation1996, 19), thus seeking to ‘redress power inequalities inherent in knowledge production’ within traditional research approaches (Gubrium and Harper Citation2013, 30). Whilst PAR approaches are common in educational research (for example Brydon-Miller and Maguire Citation2009), a frequent critique is that they tend to focus on the voices of professionals in practice and do not engage the voices and perspectives of others, including students (Kemmis Citation2006). However, participatory methods are becoming increasingly common in the Social Sciences, indeed according to some journal editors we are now experiencing a ‘participatory turn’ and call for more critical consideration of the wider challenges of adopting co-production approaches (Henwood, Dicks, and Housley Citation2019).

Narrative inquiry offers a related methodological approach. The term ‘narrative’ is often used generically to refer to accounts of experience collected from people, usually by means of interviews. Narrative inquiry, however, distinguishes itself as a methodology by acknowledging that, while storytelling may be a universal practice, the ways in which stories are told and heard are contextually dependent. Thus, the historical and cultural context of the research is critical to make sense of the narrative and needs to be richly described and accounted for (Daiute Citation2014; Trahar Citation2013). As Riessman (Citation2008, 105) reminds us stories ‘are composed and received in contexts – interactional, historical, institutional and discursive’. While we concede that narrative inquiry is not always related to a participatory research approach, we argue that their emphasis on the importance of contextualised, personal accounts and the plurality of subjectivities establishes a connection. Narrative inquiry foregrounds the interactions between researcher and research participants and fostering reciprocity in research relationships (Akoto Citation2013). In addition, methods must be culturally sensitive. Lee (Citation2009), for example, identifying as an ‘indigenous researcher’ describes how she reconceptualised Pūrākau, a term describing Māori myths and legends, as ‘a culturally responsive construct for narrative inquiry’ (Lee Citation2009, 1) in order to use this methodology in her research with Māori teachers. Indigenous-led research methodologies offer related approaches, emphasising the personal through testimonies, storytelling, claiming histories and celebrations of survival as methods (Smith Citation2012, 144–147).

Participatory research approaches have been argued to work within a ‘decolonising mode’ through attempts to avoid a deficit positioning of under-represented and/or marginalised participants, or communities, and seeking alternative forms of representation and participation (Bozalek and Biersteker Citation2010; Marovah and Mutanga Citation2023; Seppälä, Sarantou, and Miettinen Citation2021). As we show later, multimodal research methods such as drawing, mapping, and digital storytelling can give rise to alternative, rich data sources (Gubrium and Harper Citation2013), offering less reliance on text and traditional language practices and can be particularly helpful for participants who are not using their first language and may not be confident in an additional language, thus offering increased opportunities for equitable participation (Rohleder and Thesen Citation2012; Leibowitz et al. Citation2019).

Our approach aimed to combine these different methodological starting points by working alongside undergraduate students as co-researchers in an international study based in South Africa. The methodology was developed from previous participatory, multimodal and narrative inquiry work pioneered by several of the UK and South African authors (Timmis and Williams Citation2013; Timmis and Muñoz-Chereau Citation2022; Rohleder et al. Citation2008; Trahar Citation2011). It was designed to foreground our shared values, commitment to social justice, and to ‘work towards the advancement of decoloniality as a way of pluralising our research processes’ (Martinez-Vargas Citation2020, 124).

We now discuss our underpinning decolonial position and its relationship to research methodologies. We then introduce Nancy Fraser’s (Citation2009) multiple concepts related to participatory parity as part of her social justice framework and its relevance to the critique of participatory methodologies and approaches. The paper then introduces the SARiHE study conducted in South Africa and sets out its methodological principles and methods, and our critical reflections on the strengths and limitations of the co-researcher approach adopted. We then explore the potential of co-researcher methodologies to contribute to decolonising research methodologies and methods that can generate understandings of student experience of higher education, drawing on Fraser’s (Citation2009) three principles of participatory parity: re-distribution, recognition, and representation. Finally, we suggest ways in which co-researcher methodologies might address some of the challenges outlined and move further towards participatory parity and to decolonising researching students’ experiences of teaching and learning in the future.

Decoloniality and methodology

In higher education, longstanding drives to foster undergraduate research initiatives can contribute to curricular and pedagogical decision making (Brew Citation2013; Healey and Jenkins Citation2009). Similarly, a long history of initiatives has encouraged students to become active partners in rethinking the university more radically, such as through the ‘Students as Producers’ programme (see Neary et al. Citation2014). More recently, this has involved working with (or consulting) students on ways to decolonise universities, including the curriculum (Motala, Sayed, and de Kock Citation2021; Meda Citation2020; Laing Citation2021). However, Mercer-Mapstone et al. caution that ‘decolonisation efforts tend to be predominantly led by marginalised groups’ and ‘It is no marginalised group’s responsibility to produce the solutions for the systemic oppression they face’ (Mercer-Mapstone, Islam, and Reid Citation2021, 239). Such words reflect Arday, Belluigi and Thomas’s belief that ‘involvement of white allies in the decolonisation project is essential’ (Citation2021, 309) but, at the same time, we need to be aware that this concept of ‘white allyship’ is contested (Andrews Citation2018). Navigating these complexities was an intrinsic element of our methodological approach, as we explain later.

Calls to decolonise higher education have been particularly urgent in South Africa since the ‘#fees must fall’ student protests, targeting traditional and formerly ‘white’ universities in particular (Luescher, Loader, and Mugume Citation2017). Students demanded an end to the colonialist grip on higher education, its curricula, pedagogies, and an end to extractive research practices (Hodes Citation2017; Chinguno et al. Citation2017).

As researchers on an international, externally funded project intent on adopting a decolonial approach, we needed to pay attention to such calls, particularly from those voices in South Africa and the global South. The argument that colonial power has never left South Africa is one of the drivers for the focus on the term decoloniality as opposed to decolonisation. Decoloniality focuses on confronting and undoing the privileging of European worldviews, western methodologies, and languages of the colonisers in such institutions as schools and universities. It advocates dealing resolutely with the continuing and visible presence of coloniality in knowledge hegemony, by foregrounding indigenous epistemic frameworks and bringing different knowledges into dialogue (de Sousa Santos Citation2014; Ndlovu-Gatsheni Citation2014).

Recently, participatory approaches that aim to be decolonising research are more visible, discussing potential pitfalls, for example power hierarchies, ethical tensions, representation, and dialogue (Seppälä, Sarantou, and Miettinen Citation2021; Marovah and Mutanga Citation2023). Leibowitz et al. (Citation2019) also argue that to adopt a decolonising mode, agency needs to be central to how the research is conducted, together with an emphasis on the interaction between the subjects and the environment. Both are critical to any investigation committed to avoiding extractive knowledge generation (Connell Citation2017; de Sousa Santos Citation2014).

It is on the basis of this body of work that in our research, decoloniality was at the heart of methodology that sought to be decolonising as well as participative and thereby contribute to social justice. However, social justice principles should not be conflated with decoloniality, they are distinct, coming from different traditions, although they can be aligned, as we show. We now turn to social justice, participatory parity and related concepts and show how these framings work together.

Social justice in research – Fraser’s participatory parity

Social justice theories have moved from initially a sole focus on redistribution, towards more emphasis on recognitive and representational justice and one of the key contributors has been Nancy Fraser (Adam Citation2020). Fraser, a feminist philosopher, began developing her theory of justice focusing on gender inequalities and between 2003 and 2009 developed this further into a ‘three dimensional, multi-level theory which offers a ‘significant contribution to critical theorising and transformative practice for examining higher education’” (Hölscher and Bozalek Citation2020, 8). Initially Fraser outlined two conditions or dimensions, firstly, the economic re-distribution of material resources is to ensure participants’ independence and voice (Re-distribution) and secondly, a cultural dimension – institutionalised patterns of cultural value conferring equal respect on all participants and equal opportunity for achieving social esteem (Recognition). She argued that both are necessary to address and remedy injustice. Whilst she subscribed to views held by Marxists and social democrats in terms of justice and the need for redistribution of rights and resources, she also shared the views of ‘feminist, anti-racist and decolonial movements, that identity matters to questions of justice as much as economic concerns’ (Hölscher and Bozalek Citation2020, 9). Fraser's later work augmented these ideas by adding a political dimension, through the additional concept of Representation, focusing on power, voice, transnational injustices, and globalised sites of struggle (Fraser Citation2009). Fraser argued that this was required to address the complexities of globalisation and neoliberalism and to highlight the extent to which community members are given ‘equal voice in public deliberations and fair representation in public decision-making’ (Fraser Citation2009, 18). She also emphasised examining who is being excluded or silenced and how global and local institutions and procedures enact this through frame-setting decisions, referred to as ‘misframing’ (Bozalek and Boughey Citation2020; Fraser Citation2009). Fraser’s normative framework sets out, the necessary conditions for peers to fully participate and interact equally and meaningfully in all three dimensions, through the concept of ‘participatory parity’ as the enactment of ‘social arrangements that permit all members of society to interact with one another as peers’ (Citation2003, 36). Fraser further suggests ‘overcoming injustice means dismantling institutionalised obstacles that prevent some people from participating on a par with others, as full partners in social interaction’ (Fraser Citation2009, 16). Her emphasis on overcoming injustice through social interaction is reminiscent of Fricker’s (Citation2007) work on epistemic injustice where she argues for ‘epistemic reciprocity’ between communicators or knowers. It also links to the decolonial principles of bringing multiple knowledges into dialogue, and seeking to avoid misrecognition or silencing, particularly of those who are marginalised or without a voice in society (Mgqwashu et al. Citation2020; Naidoo et al. Citation2020).

Fraser’s work has been utilised extensively in higher education to examine and interrogate inequalities and injustice (for example Shefer, Clowes, and Ngabaza Citation2020; Burke Citation2013; Bozalek and Boughey Citation2020). However, it has been used less frequently as a lens for interrogating research methodological approaches, despite Burke's (Citation2013) assertion that adopting a methodological approach to researching inequities should be commensurate with the values and ethical positions being advocated. Moving towards greater parity in research suggests rethinking, not just what we research, but how that research is conducted and how social justice principles are enacted within the research process.

In this paper we employ Fraser’s concepts of redistribution, recognition, representation, misframing and participatory parity to assist us in interrogating research methodologies and methods (including our own) that might claim to be decolonising and/or participatory in terms of how those participating are positioned and represented, and how the research is conducted, including contextual issues surrounding internationally funded research which also shaped and limited possibilities.

Whilst some may question the inclusion of social justice theory that draws (partially) on Marxism and Western scholarly traditions and suggest this might be incompatible with decolonial values and positions, Raza and Ali (Citation2024) reviewing the work of Walter Rodney, a Guyanese decolonial Marxist scholar who worked in the Caribbean and Africa refer to ‘worldly Marxism’ as ‘neither Eurocentric nor simply postcolonial, worldly Marxism represents a Marxism undergoing constant reinvention as it exceeds its origins in Europe to extend across settler colonies, (post)colonies, and metropoles – a Marxism that acquires universal significance precisely through its attention to particular contexts’(Raza and Ali Citation2024, np). A focus on context resonates clearly with decolonial emphases on place and history (Ndlovu-Gatsheni Citation2014). Equally they point out how higher education institutions’ adoption of decolonisation thinking, and processes has not sufficiently considered issues of power (Raza and Ali Citation2024). It is worth noting furthermore, that social justice and decoloniality are bound together in the context of South African higher education as Adam notes ‘Post 2015, social justice discourses in South Africa took a decolonial turn (…), which called to the forefront epistemic injustices and more ground-up conceptualisations and theorisations of issues of justice in South Africa’(Adam Citation2020, 2). Therefore, whilst we acknowledge the different histories and bodies of scholarship, and the Western roots to Fraser’s work, in addressing injustice, we suggest these are complementary to and help interrogate the decolonial values and positionings as outlined above.

The following section gives an overview of the study before outlining the methodological approach we adopted and the methods employed.

Sarihe project overview

This paper builds on our experiences of an international study known as SARiHE based in South Africa involving three South African and two UK partners (2016–2019) (Timmis et al. Citation2022). The research investigated the experiences of students from rural areas – one of the groups most marginalised and affected by apartheid in South Africa – in accessing higher education. The study focused on how students negotiate the transition to university, the support that they need once there and how inclusive teaching and learning practices can be developed to challenge the continuing coloniality of higher education curricula. A core aim was to foreground the social and cultural capital of students in rural contexts and how they are shaped by their home, school, and community.

The research was conducted at three universities: UrbanFootnote1 (an urban ‘comprehensive’ university with a balanced focus on research, teaching, and technology), Town (a rural, research-led and ‘previously advantaged’ university) and Local (a rural, teaching-led, ‘previously disadvantaged’ university). 24 second year undergraduates, all from rural backgrounds were recruited as co-researchers in each university, with a balance between Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM) and Humanities programmes. A very low attrition rate meant that 65 (out of 72) co-researchers were still participating at the end of the project. From April 2017 to April 2018, they participated and researched their own lives through a series of data collection and analysis activities, workshops, dissemination, and publishing activities. Senior leaders and academics from each university were also interviewed in a further stage of the project.

Sampling

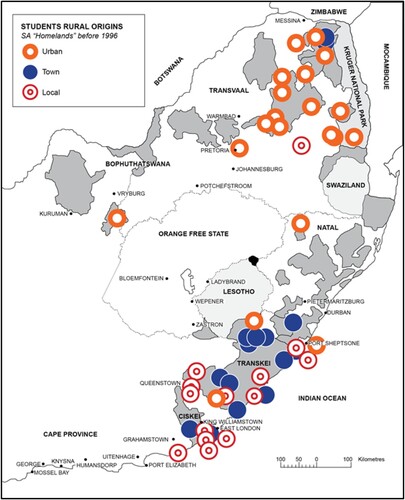

The three institutions were purposefully sampled to represent the different institutional types in South Africa and varied in size, institutional histories, and resources. All three universities have students from rural areas amongst their undergraduate populations. English is employed as the language of instruction at all three institutions. Second-year undergraduates with rural backgrounds from STEM and Humanities (including Education) programmes as co-researchers at the three institutions were recruited through volunteer and snowball sampling methods. To be included in the sample, students had to have lived and attended school in a rural area in South Africa for at least the first sixteen years of their lives. The map () shows the places where student co-researchers grew up and went to school – the majority were from communities that were formerly part of the apartheid homeland areas (Bantustans). Urban student co-researchers' places of origin are depicted in orange, Town in blue and Local in red.

Developing a co-researcher methodology

The co-researcher methodology was developed from previous research in the UK with medical students (Timmis and Williams Citation2013) and under-represented undergraduates (Timmis and Muñoz-Chereau Citation2022). It also drew on participatory action learning and cognitive mapping approaches (Leibowitz et al. Citation2012), narrative inquiry principles and methods (Trahar Citation2013; Citation2011) and multimodal and place-based approaches (Leibowitz et al. Citation2019; Rohleder and Thesen Citation2012). This approach was intended to foreground how the identities of study participants were shaped by their interactions, histories, and experiences. It was also intended to have some pedagogical benefits for students to learn about and apply social science research methods and methodologies in an authentic setting.

Reason (Citation1994, 41–42) emphasises.

… all those involved in the research are both co-researchers, who generate ideas about its focus, design and manage it, and draw conclusions from it; and also co-subjects, participating with awareness in the activity that is being researched.

Each student co-researcher was given an iPadFootnote2 which they could keep at the end of the project as a ‘thank-you’ and acknowledgement of their contributions. Using their iPads, in conjunction with an application called Evernote (or Google docs), student co-researchers created longitudinal, personal, multimodal accounts and representations of everyday practices in their rural communities and their university academic and social lives by collecting and curating a series of digital artefacts. A common critique of participatory research is that co-researchers are often only involved in data collection and therefore can only respond to and produce data for a pre-figured set of aims and methods. Yet Park (Citation2006) highlights the importance of seeing participatory research as ‘action-oriented’ so that it should be judged in terms of the decision making and agency of co-researchers. In our study, whilst overall aims and processes were pre-set, we were mindful of this and ensured student-co-researchers chose how to represent their own experience and which topics or stories to focus on. They could also decide which artefacts to collect, what to exclude and how to record stories or accounts. The variety of these were testament to the creativity and agency of student co-researchers. They included diary entries, poetry, audio recordings, drawings, photographs (sometimes annotated) and videos. This decision making and data control, we argue, are critical in seeking to shift the balance of power in participatory research (Braye and McDonnell Citation2013).

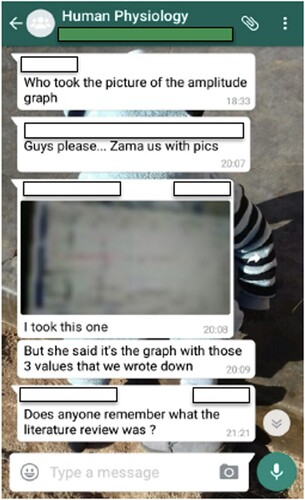

and show two examples from co-researcher images of their lives at university:

Figure 3. Student co-researcher image of a WhatsApp study conversation from a lab group (reproduced with permission).

This co-researcher’s commentary accompanying the image reads ‘This is a room I share with my roommate at res. It reminds me of home because I also share a room with my little sister’ (Urban, 24 August 2017).

We also aimed to support co-researchers methodologically, in reflecting on and sharing their experiences and becoming familiar with storytelling, multimodal and narrative methods. Seven workshops were staged over several months and themes included co-developing ethical principles, understandings of rurality, learning in rural areas in diverse settings (e.g. family, school, church, traditional cultural activities, using technology), transitions to higher education, learning at university, personal values. Using digital technologies such as iPads presented some challenges and it was critical therefore to offer support for using the technologies and systems and to enable the development of further skills for student co-researchers.

For workshop seven, student co-researchers were invited to produce and share a short documentary, combining previously collected digital artefacts. This enabled a first opportunity for representation of their stories to their peers, and associated discussion on the common experiences they shared (or did not) and the beginnings of a shift in the power balance, where the student co-researchers were able to control the narrative and offer their own interpretations (Smith Citation2012).

This was further developed through a final two-day workshop where student co-researchers from the three universities and the co-investigators came together for joint analysis and discussion sessions, where co-researchers offered their own interpretations of data and challenged misconceptions. At this event, they also began to ask searching questions and challenge the co-investigatorsFootnote3 on how they (co-researchers) would be acknowledged in the research outputs. In response to this discussion, the student co-researchers decided they wanted to produce their own publication (see section below).

Publications, recognition and agency

There were several ways in which the student co-researchers were able to gain visibility and recognition of their contributions throughout the project but particularly towards the end. A series of dissemination events were held and student co-researchers were involved in these events as speakers, representing their own interpretations of the findings and experience on the project. Events were attended by different stakeholders: NGOs, policymakers and academics. Student co-researchers also presented at our final academic conference and in one case through a radio interview. We also invited co-researchers to contribute blog postings to our website.Footnote4 These were useful opportunities but they were initiated by the co-investigators and not the co-researchers themselves.

However, as outlined in section above, following our final joint workshop, the co-researchers went further and, a group from all three research sites initiated a publishing project because they wanted to create a publication to go back to their rural communities. They wanted this to be in their own voices, highlighting their experiences and translated in all the official languages to make it accessible to all rural communities. They co-designed and co-wrote a booklet entitled ‘Going to university: stories from rural students’. The printed booklet was disseminated by the co-researchers to their own communities in rural areas, and for which they were fully acknowledged as authors (All 64 student co-researchers were named). Additional project funding supported co-researchers’ endeavours and enabled publishing in all eleven official languages of South Africa in printed form and online.Footnote5 Whilst we acknowledge that this initiative does not equate to inclusion in peer reviewed academic publications (we return to this issue later), which might be seen by some as stronger evidence of participatory parity, we would argue that in terms of impact on communities, the initiative brought in by the student co-researchers offers more potential for material and social change and certainly involved a change in positioning for the co-researchers. Co-researchers showed commitment to the aims and values of the project, as well as a willingness to challenge research norms and hierarchies, suggesting a change in the power dynamics with the project (Park Citation2006; Braye and McDonnell Citation2013).

Ethical principles and approaches

Formal ethical clearances, ethical principles and actions that formed part of the project are now outlined.

Ethical clearances

As an international project, funded by three linked inter/national funders (NRF – National Research Fund in South Africa, ESRC in UK, under the auspices of the Newton FundFootnote6), ethical clearance was prioritised after securing funding. Ethical clearance was first granted by the ethics committee at the lead institution in South Africa, (Clearance Number: 2016-103, 1 February 2017). This was followed by the remaining two institutions in South Africa: (270710-028-RA Level 1, 30 May 2017) and (Ethics clearance,20 February 2017, no ref number). UK institutions involved in the study were not required to submit an ethics application, as all data was collected in South Africa.

Ethical principles in action

Ethical thinking and ethical mindfulness were central in our approach, particularly in relation to rights and responsibilities of all members of the team, including the student co-researchers. Students who were considering becoming co-researchers were briefed on the aims and objectives of the study, their roles as student co-researchers and asked to sign a consent agreement covering all aspects of the role including data collection, participation in workshops and in dissemination activities. They were asked to give consent that their data, individual and group insights and digital artefacts could be used in the study and in publications. Consent forms and information sheets were also provided to senior leaders and academics in Phase 2.

During the first workshop, ethical issues were discussed and a set of ethical principles were jointly negotiated with student co-researchers. These then guided the study, and everyone received a copy (for details see Timmis et al. Citation2022, 56). Key aspects were to ensure that students were able to make choices over participation and to be in control of their own data. Issues of confidentiality, privacy, and respect for all participants, even if values were not shared, were discussed and agreed on with the student co-researchers. Topics that came up in the discussions such as gender relations and sexuality had to be treated confidentially and in the workshops such discussions had to be conducted with sensitivity and respect for everyone in the group and their different views and experiences.

It is important to highlight that methodological approaches such as this, demand a high level of reflexivity from everyone, both the student-co-researchers in their activities within the project and the funded co-investigators. From the outset of the project, as an investigative team, we engaged in articulating and sharing our own beliefs, experiences and values. In addition, those of us who are ‘White race scholars’ (Mehdi and Jameela Citation2021, 152) were wary of falling into the trap of misappropriating, misapplying and misusing the concepts of decolonisation and decoloniality (Mehdi and Jameela Citation2021). ‘Bringing different knowledges into dialogue’ (Timmis et al. Citation2022, 155) was, therefore, a critical element of our interactions as was allowing for the ‘incompleteness of knowledge’ (de Sousa Santos Citation2016, 22).

Participatory parity in co-researcher methodologies

We now discuss the value of co-researcher methodologies for research in higher education, reflecting on the strengths and limitations of such approaches in relation to Fraser’s (Citation2003; Citation2009) principles of redistribution, recognition, representation and participatory parity and the extent to which such a co-researcher methodology can contribute to decolonial practices in higher education.

The methodological approach and methods we developed enabled students to research and narrate their own lives and life histories and to tell the stories that mattered to them, their peers and communities, conferring cultural value on their experiences and the process of research. As Smith argues ‘ the story and the storyteller both serve to connect the past to the future, one generation to another, the land with the people, and the people with the story’ (Smith Citation2012, 146). This also meant that student co-researchers had greater control over their own data, which data was chosen and how their personal narratives were represented and interpreted than they would in a more conventional study where they may be positioned as solely data providers. As highlighted earlier this suggests a shift in the power dynamics within the project and evidence of the recognition and representation dimensions to participatory parity and ‘action-oriented’ change (Fraser Citation2009; Park Citation2006). We argue that such changes contribute to decolonial approaches to research through the agency and representation of student co-researchers, from marginalised backgrounds, in our case, rural communities in Post-Apartheid South Africa (Leibowitz et al. Citation2019).

Furthermore, as co-investigators, working alongside student co-researchers we were not only gaining insights from our student colleagues and were being challenged to reflect on and interrogate our own beliefs and values. Not only were we supporting them in the process, they were provoking us to question ourselves, thus suggesting epistemic reciprocity and some parity of participation (Fricker Citation2007; de Sousa Santos Citation2014). Nonetheless, we acknowledge that in a study initiated by academics as part of an international funding scheme, being an unfunded student co-researcher can never be equated to being a salaried university employee conducting research. Students were able to keep the iPad if they continued to the end of the research as some recompense and an acknowledgement of their contributions and travel and other expenses were reimbursed, but the disparity in status and capitals between student co-researchers and salaried co-investigators is a significant limitation on participatory parity within funded research projects. Thus, the principle of redistribution is much more challenging to fulfil in participatory research in higher education. Full compensation for student co-researchers would need to be argued for in the research proposal at the outset of the project, but this is another challenge for funders whose sympathies towards participatory research methodologies may conflict with other pressures (Grimes and McNulty Citation2016).

Kovach (Citation2021) argues that storytelling is both method and meaning and by creating and curating digital artefacts and sharing their stories, co-researchers were able to exercise agency and to foreground issues that they felt were most critical to learning and their lived experience. Leibowitz (Citation2017a) has warned against conceptualising marginalised people as lacking in agency. As highlighted earlier, student co-researchers exercised agency in different ways during their time in the project and participated in decision making about which stories were important and how best to share and represent them and especially in bringing forth new ideas such as the booklet they produced for rural communities. Thus offering evidence of both recognition and representation (Fraser Citation2009). Moreover, in their reflections on the process of being a co-researcher, both in blog postings and final narratives, many of them attested to the agency they experienced. Importantly it appeared to help enhance reflexivity and critical thinking abilities – as shown in this extract from one co-researcher’s testimony:

The SARiHE program has helped me in so many ways that I can see [myself] as a better student now. My public speaking confidence has improved, my doubt has decreased and I am more courageous now. I have learned to listen a bit more than complain a lot about how the inequalities are in the country. SARiHE has made me a better person besides the school aspects of it. I have gained some knowledge of how to do research and how to deal with people better. (…) When people ask what the SARiHE project is about, I tell them to think of it as a very informative session with a psychologist that knows and feels everything you are about. (…) I always say to them that they should start participating in research groups on campus and when they ask me, I always [say] like SARiHE is a good starting point to embrace who you are whilst learning research basics.

(SARiHE student co-researcher - 29/10/18)

We continually sought ways for student co-researchers to participate in all stages of the research, however, in-depth analysis and peer reviewed publications are very long processes and although student co-researchers were involved to an extent, it was not possible to maintain their participation beyond the life of the project and because their lives moved on to new and different challenges. Therefore, whilst we have sought participatory parity with co-researchers in most aspects of the research, one limitation is in academic publications, where they have not been included as authors, although, for example on this paper, all 65 student co-researchers are named in the acknowledgements.

A particular feature of participatory research is that the research should involve shifts in power (Braye and McDonnell Citation2013). These shifts in power need to operate both within the research project itself, where the aim should be for democratic peer to peer relationships and secondly, possible power shifts between project participants and their broader social context should be facilitated (Braye and McDonnell Citation2013). From this perspective, our research can be understood as ‘a social practice that helps marginalised people attain a degree of emancipation’ (Park Citation2006, 83) and an attempt to ‘reframe’ the research context in terms of power (Fraser Citation2009).

We have also reflected on the wider constraints on participatory methods and the extent to which anyone can claim to be adopting participatory parity within research projects where there are pre-determined research questions, especially in funded research with high levels of specificity and requirements. Our project was funded by three different funding bodies, with predetermined themes and a requirement to specify methodology and methods very precisely. Even though the Newton fund co-designs funding calls with Southern partners and actively encourages participatory designs, the pre-determined design and methodology cannot be fundamentally altered. In our case, this led to constraints in our initial discussions with academic partners and offered less opportunities for student co-researchers to shape the timing or direction of the research once they became involved. Brown and colleagues (Citation2023), writing about their experiences of the MEMPAZ project in Colombia, also funded by the Newton Fund, highlight many of the same issues, as well as the impacts of UK institutional risk strategies and bureaucracies that betray underlying deficit assumptions of Southern universities and actively constrained partnerships and the conduct of co-produced research. We experienced similar kinds of ‘misframing’ (Fraser Citation2009; Bozalek and Boughey Citation2020) of our Southern university partners, where institutional contexts were oversimplified and pre-judged.

Conclusions

A significant strength of the SARiHE project was that the methodological approach enabled co-researchers to have their voices heard in a context in which, pre-1994, they would have been silenced. Even post democracy, students from marginalised communities, especially those from rural areas, such as the co-researchers, struggle to be heard in a higher education system, dominated by a few, privileged voices. Our methodological approach emphasised not only co-research but also the importance of the context and places within which stories are told and shared (Leibowitz et al. Citation2019). Bringing co-researchers together with co-investigators in the workshops also provided opportunities not only for the imparting and sharing of stories, but also for group members to challenge those accounts that they considered to be censored in some way, thus opening up different stories. Crucially, some co-investigators were themselves from rural contexts in Southern Africa and they shared their own experiences. Such practices helped to develop co-researchers’ confidence in presenting themselves and their lives to others and, ultimately, to university leaders and policy makers. Perhaps as well as recognition and representation as co-researchers, we may be able to claim that student co-researchers achieved a degree of positive change in their lives (as the student testimony quoted above shows) and contribute to helping others in their communities access higher education, as discussed previously. However, we acknowledge that this may not amount to material redistribution, which would require a more radical research design, where projects are initiated from within the community. The extent to which this is achievable within an undergraduate student community remains a challenge.

Extrapolating from the SARiHE experience to propose how participatory methodologies might address the need for decolonising student-focused research in higher education, it seems clear that opening up space for co-researchers to research and interpret their own situated stories and histories, to take control of their data and make choices about what is significant, together with working alongside co-investigators, can address some of the extractive and knowledge appropriation approaches that decolonial methodologies have critiqued (Kovach Citation2021; Smith Citation2012; Marovah and Mutanga Citation2023). Importantly, we suggest that such approaches can also contribute to the decolonisation of learning and teaching in higher education by fostering situated knowledge production, critical thinking, reflexivity and agency amongst students and by working towards participatory parity and recognition amongst all those involved in research.

Yet, we also acknowledge the limitations in co-researcher methodologies, such as ours. These include the imbalances in roles and opportunities due to systemic disparities between salaried co-investigators and unfunded student co-researchers, which in turn suggests that the shifts in power that participatory research anticipates, were not fully possible. We have also shown how funded participatory studies, such as ours, are frequently constrained by the requirement for prescribed research designs. We suggest that funding bodies who genuinely want to support decolonising and participatory research approaches need to allow more open, unfolding research designs where new research questions and methods can be embraced and where projects can respond to emergent ideas from student co-researchers and partners. Finally we emphasised how global South/North partnerships are put at risk through university bureaucratic procedures that are underpinned by deficit assumptions and the ‘misframing’ of Southern partners. We suggest that funding agencies and universities need to consider how their own processes are constraining decolonising research including co-production and participation methodologies which they are, seemingly so keen to promote.

The ‘participatory turn’ in social science research is to be welcomed, as it invites more opportunities for participatory parity and social justice (Fraser Citation2003; Citation2009) in research, especially in higher education institutions still struggling to find practical ways to embed decolonisation (Hayes, Luckett, and Misiaszek Citation2021). Working with students as co-researchers using participatory methodologies, combined with narrative and multimodal methods could offer one possible avenue for further development. Our experiences have shown that such approaches can enable more possibilities for recognition and representation and student agency, although pre-existing power hierarchies and methodological norms still need to be resisted. Economic/material redistribution is much more challenging because it reflects the wider socio-political research funding environment. One lesson from this project and other similar projects is that if academics want to achieve participatory parity with student co-researchers in higher education research, they need to be more agential themselves and to collectively urge funders to be more flexible with proposal requirements to allow for greater methodological innovation through partnership and allow their input and priorities to shape the project once funding has been secured.

Acknowledgements

We thank the anonymous reviewers of this article for their help in improving on the original version. The Southern African Rurality in Higher Education (SARiHE) project was undertaken by Principal Investigators - Sue Timmis (University of Bristol) and Thea de Wet (University of Johannesburg) with Kibbie Naidoo (University of Johannesburg), Sheila Trahar, Lisa Lucas, Karen Desborough (University of Bristol), Emmanuel Mgqwashu (North West University), Nathi Madondo (Mangosuthu University of Technology), Patricia Muhuro (University of Fort Hare) and Gina Wisker (University of Brighton). We were accompanied on this project by 65 student co-researchers (named below) and 9 institutional researchers. We fully acknowledge their contributions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Student co-researchers

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Institutional names have been anonymised – Urban, Town and Local are pseudonyms.

2 Co-researchers were asked to sign a contract for the iPad and take responsibility for its safekeeping.

3 We use this term to distinguish salaried researchers from the student co-researchers for clarity.

5 Online versions of the booklet are available through a creative commons license – see https://sarihe.org.za/going-to-university/

6 See www.newton.ac.uk

References

- Adam, T. 2020. Between social justice and decolonisation: Exploring South African MOOC designers’ conceptualisations and approaches to addressing injustices. Journal of Interactive Media in Education 2020, no. 1: 1–11. doi:10.5334/jime.557.

- Akoto, J.S. 2013. ‘The teeth and the tongue’: A narrative inquiry journey in Ghana. In Contextualising narrative inquiry: Developing methodological approaches for local contexts, ed. Sheila Trahar, 74–88. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Andrews, K. 2018. The black studies movement in Britain: Becoming an institution not institutionalised. In Dismantling racism in higher education: Racism, whiteness and decolonising the academy, eds. Jason Arday and Heidi Mirza, 272–87. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Arday, J., D.Z. Belluigi, and D. Thomas. 2021. Attempting to break the chain: Reimaging inclusive pedagogy and decolonising the curriculum within the academy. Educational Philosophy and Theory 53, no. 3: 298–313. doi:10.1080/00131857.2020.1773257.

- Bozalek, V., and L. Biersteker. 2010. Exploring power and privilege using participatory learning and action techniques. Social Work Education. The International Journal 29, no. 5: 551–72. doi:10.1080/02615470903193785.

- Bozalek, V., and C. Boughey. 2020. (Mis)Framing higher education in South Africa. In Nancy Fraser and participatory parity: Reframing social justice in South African Higher Education, eds. Vivienne Bozalek, Dorothee Hölscher, and Michalinos Zembylas, 68–81. London: Routledge. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9515.2012.00863.x

- Braye, S., and L. McDonnell. 2013. Balancing powers: University researchers thinking critically about participatory research with young fathers. Qualitative Research 13, no. 3: 265–84. doi:10.1177/1468794112451012.

- Brew, A. 2013. Understanding the scope of undergraduate research: A framework for curricular and pedagogical decision-making. Higher Education 66, no. 5: 603–18. doi:10.1007/s10734-013-9624-x.

- Briffett Aktaş, C. 2021. Enhancing social justice and socially just pedagogy in higher education through participatory action research. Teaching in Higher Education 29, no. 1: 159–75. doi:10.1080/13562517.2021.1966619.

- Brown, M., A. Gómez-Suarez, D.V. Duarte, L.A. Hankin, F.L. de la Roche, J. Paulson, M.G. Gutiérrez, et al. 2023. History on the margins: Truths, struggles and the Bureaucratic Research Economy in Colombia, 2016–2023. Rethinking History 27, no. 3: 461–87. doi:10.1080/13642529.2023.2211449.

- Brydon-Miller, M., and P. Maguire. 2009. Participatory action research: Contributions to the development of practitioner inquiry in education. Educational Action Research 17, no. 1: 79–93. doi:10.1080/09650790802667469.

- Burke, P.J. 2013. The right to higher education: Beyond widening participation. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Chinguno, C., M. Kgoroba, S. Mashibini, B.N. Masilela, B. Maubane, N. Moyo, A. Mthombeni, and H. Ndlovu. 2017. “Rioting and writing: Diaries of the Wits Fallists.” Published by the Authors in Collaboration with SWOP, University of the Witwatersrand. Johannesburg. https://docs.wixstatic.com/ugd/de7bea_8ff05c74ed634e1fbf3d179284f74cd6.pdf.

- Connell, R. 2017. Southern theory and world universities. Higher Education Research and Development 36, no. 1: 4–15. doi:10.1080/07294360.2017.1252311

- Daiute, C. 2014. Narrative inquiry: A dynamic approach. Los Angeles: Sage.

- Fraser, N. 2003. Social justice in the age of identity politics: Redistribution, recognition and participation. In Redistribution or recognition? A political-philosophical exchange, edited by N. Fraser and A. Honneth, 7–88. London: Verso.

- Fraser, N. 2009. Fraser, Nancy. Scales of justice: Reimagining political space in a globalizing world. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Fricker, M. 2007. Epistemic injustice : Power and the ethics of knowing. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Grimes, R.W., and C. McNulty. 2016. The Newton Fund: Science and innovation for development and diplomacy. Science & Diplomacy 5, no. 4. https://www.sciencediplomacy.org/article/2016/newton-fund-science-and-innovation-for-development-and-diplomacy.

- Gubrium, A., and K. Harper. 2013. Participatory visual and digital methods. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press.

- Hayes, A., K. Luckett, and G. Misiaszek. 2021. Possibilities and complexities of decolonising higher education: Critical perspectives on Praxis. Teaching in Higher Education 26, no. 7–8: 887–901. doi:10.1080/13562517.2021.1971384.

- Healey, M., and A. Jenkins. 2009. “Developing undergraduate research and inquiry.” York. http://www.heacademy.ac.uk/assets/documents/research/DevelopingUndergraduateResearchandInquiry.pdf.

- Henwood, K., B. Dicks, and W. Housley. 2019. QR in reflexive mode: The participatory turn and interpretive social science. Qualitative Research 19, no. 3: 241–6.

- Heron, J. 1996. Co-operative inquiry: Research into the human condition. London: Sage.

- Hodes, R. 2017. Questioning ‘Fees must fall.’ African Affairs 116, no. 462: 140–50. doi:10.1093/afraf/adw072.

- Hölscher, D., and V. Bozalek. 2020. Nancy Fraser’s work and its relevance to higher education. In Nancy Fraser and participatory parity: Reframing social justice in South African Higher Education, eds. Vivienne Bozalek, Dorothee Hölscher, and Michalinos Zembylas, 3–19. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.

- Kemmis, S. 2006. Participatory action research and the public sphere. Educational Action Research 14, no. 4: 459–76. doi:10.1080/09650790600975593.

- Kovach, M. 2021. Indigenous methodologies: Characteristics, conversations and contexts. Second. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- Laing, A.F. 2021. Decolonising pedagogies in undergraduate Geography: Student perspectives on a decolonial movements module. Journal of Geography in Higher Education 45, no. 1: 1–19. doi:10.1080/03098265.2020.1815180.

- Lee, J. 2009. Decolonising Māori Narratives: Pūrākau as Method. MAI Review, no. Article 3: 1–12.

- Leibowitz, B. 2017a. Cognitive justice and the higher education curriculum. Journal of Education 68: 93–111.

- Leibowitz, B. 2017b. Power, knowledge and learning: Dehegomonising colonial knowledge. Alternation 24, no. 2: 99–119. Retrieved from https://journals.ukzn.ac.za/index.php/soa/article/view/1322. doi:10.29086/2519-5476/2017/v24n2a6.

- Leibowitz, B., E.M. Mgqwashu, C. Kasanda, P. Lefoka, V. Lunga, and R.K. Shalyefu. 2019. Decolonising research : The use of drawings to facilitate place-based biographic research in Southern Africa. Journal of Decolonising Disciplines. 1, no. 1: 27–46. doi:10.35293/2664-3405/2019/v1n1a3.

- Leibowitz, B., L. Swartz, V. Bozalek, R. Carolissen, L. Nicholls, and P. Rohleder. 2012. Community, self and identity: Educating South African University students for citizenship. Cape Town: HSRC press. https://repository.essex.ac.uk/25394/.

- Luescher, T., L. Loader, and T. Mugume. 2017. #FeesMustFall: An internet-age student movement in South Africa and the case of the University of the free state. Politikon 44, no. 2: 231–45. doi:10.1080/02589346.2016.1238644.

- Marovah, T., and O. Mutanga. 2023. Decolonising participatory research: Can Ubuntu Philosophy contribute something? International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 1–16. doi:10.1080/13645579.2023.2214022.

- Martinez-Vargas, C. 2020. Decolonising higher education research: From a Uni-Versity to a Pluri-Versity of approaches. South African Journal of Higher Education 34, no. 2: 112–8. doi:10.20853/34-2-3530.

- Mbembe, A.J. 2016. Decolonizing the University: New directions. Arts and Humanities in Higher Education 15, no. 1: 29–45. doi:10.1177/1474022215618513.

- Meda, L. 2020. Decolonising the curriculum: Students’ perspectives. Africa Education Review 17, no. 2: 88–103. doi:10.1080/18146627.2018.1519372.

- Mehdi, N., and M. Jameela. 2021. On the Fallacy of decolonisation in our Higher Education Institutions (HEIs). In Doing equity and diversity for success in higher education: Redressing structural inequalities in the academy, eds. S.P. Thomas Dave and Jason Arday, 151–60. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Mercer-Mapstone, L., M. Islam, and T. Reid. 2021. Are we just engaging ‘the Usual Suspects’? Challenges in and practical strategies for supporting equity and diversity in student–staff partnership initiatives. Teaching in Higher Education 26, no. 2: 227–45. doi:10.1080/13562517.2019.1655396.

- Mgqwashu, E.M., S. Timmis, T. de Wet, and N. Emmanuel Madondo. 2020. Transitions from rural contexts to and through higher education in South Africa: Negotiating misrecognition. Compare 50, no. 7: 943–60. doi:10.1080/03057925.2020.1763165.

- Motala, S., Y. Sayed, and T. de Kock. 2021. Epistemic decolonisation in reconstituting higher education pedagogy in South Africa: The student perspective. Teaching in Higher Education 26, no. 7–8: 1002–18. doi:10.1080/13562517.2021.1947225.

- Naidoo, K., S. Trahar, L. Lucas, P. Muhuro, and G. Wisker. 2020. ‘You have to change, the curriculum stays the same’: Decoloniality and curricular justice in South African Higher Education. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education 50: 961–97. doi:10.1080/03057920902850143.

- Ndlovu-Gatsheni, S.J. 2014. Global coloniality and the challenges of creating African Futures. Strategic Review for Southern Africa 36, no. 2: 181–202.

- Neary, M., G. Saunders, A. Hagyard, and D. Derricott. 2014. Student as producer: Research-engaged teaching, an institutional strategy. York: Higher Education Academy.

- Neary, M., and J. Winn. 2009. The student as producer: Reinventing the student experience in higher education. In The future of higher education: Policy, pedagogy and the student experience, eds. L Bell, H Stevenson, and M Neary, 192–210. London: Continuum.

- Park, P. 2006. Knowledge and participatory research. In Handbook of action research: Participative inquiry and practice, eds. Peter Reason and Hilary Bradbury, 83–93. London: Sage.

- Raza, S., and N. G. Ali. 2024. “Walter Rodney’s Radical Legacy.” Boston Review, 2024. https://www.bostonreview.net/articles/walter-rodneys-radical-legacy/.

- Reason, P. 1994. Human inquiry as discipline and practice. In Participation in human inquiry, ed. P Reason, 40–56. London: Sage.

- Riessman, C.K. 2008. Narrative methods for the human sciences. Thousand Oaks, C.A: Sage.

- Rohleder, P., L. Swartz, V. Bozalek, R. Carolissen, and B. Leibowitz. 2008. Community, self and identity: Participatory action research and the creation of a virtual community across Two South African Universities. Teaching in Higher Education 13, no. 2: 131–43. doi:10.1080/13562510801923187.

- Rohleder, P., and L. Thesen. 2012. Interpreting drawings: Reading the racialised politics of space. In Community, self and identity: Educating South African University students for citizenship, eds. Brenda Leibowitz, Leslie Swartz, Vivienne Bozalek, Ronelle Carolissen, Lindsey Nicholls, and Poul Rohleder, 87–96. Cape Town: HRC Press.

- Seppälä, T., M. Sarantou, and S. Miettinen. 2021. Introduction: Arts-based methods for decolonising participatory research. In Arts-based methods for decolonising participatory research, edited by Tiina Seppälä, Melanie Sarantou, and Satu Miettinen, 1–18. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Shefer, T., L. Clowes, and S. Ngabaza. 2020. Student experience: A participatory parity lens on social (in)justice in higher education. In Nancy Fraser and participatory parity: Reframing social justice in South African higher education, eds. Vivienne Bozalek, Dorothee Hölscher, and Michalinos Zembylas, 84–97. London: Routledge.

- Smith, L.T. 2012. Decolonizing methodologies: Research and indigenous peoples, (2nd ed.). London: Zed Books. doi:10.2307/2653993

- Sousa Santos, B.d. 2014. Epistemologies of the south: Justice against epistemicide. London: Routledge.

- Sousa Santos, B.d. 2016. Epistemologies of the south and the future. From the European South 1: 17–29. http://europeansouth.postcolonialitalia.it.

- Tight, M. 2013. Discipline and methodology in higher education research. Higher Education Research & Development 32, no. 1: 136–51. doi:10.1080/07294360.2012.750275

- Tight, M. 2018. Higher education research: The developing field. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Timmis, S., T. de Wet, K. Naidoo, S. Trahar, L. Lucas, E.M. Mgqwashu, P. Muhuro, and G. Wisker. 2022. Rural transitions to higher education in South Africa: Decolonial perspectives. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Timmis, S., and B. Muñoz-Chereau. 2022. Under-represented students’ university trajectories: Building alternative identities and forms of capital through digital improvisations. Teaching in Higher Education 27, no. 1: 1–17. doi:10.1080/13562517.2019.1696295.

- Timmis, S., and J. Williams. 2013. Students as co-researchers: A collaborative, community-based approach to the research and practice of technology enhanced learning. In The student engagement handbook, practice in higher education, eds. E Dunne and D Owen, 509–25. Emerald: Bingley.

- Trahar, S. 2011. Developing cultural capability in international higher education: A narrative inquiry. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Trahar, S. 2013. Contextualising narrative inquiry: Preface. In Contextualising narrative inquiry: developing methodological approaches for local contexts, ed. Sheila Trahar, xi–xxi. Abingdon: Routledge.