ABSTRACT

What ethical and political considerations does zine-making raise in teaching and learning across knowledge systems and artful expression? This question guides the critical dialogue about a research project on teaching sustainability through traditional proverbs from Malaysia and Kazakhstan within a zine-making workshop in a UK university. Merging our reflections with that of students and their zine artworks alongside traditional proverbs, we dialogue across two tensions associated with the challenges of proverbial learning as decolonial connections or appropriation, and the politics and pedagogy of zine-making. Through these tensions which reveal the messy, ambivalent, and unsettled practices within the neoliberal university, we offer some reflections for researchers and teachers engaging in decolonial and arts-based praxis.

Apakah pertimbangan etika dan politik yang dibangkitkan oleh pembuatan zine dalam pengajaran dan pembelajaran merentas sistem pengetahuan dan ekspresi kesenian? Persoalan ini membimbing dialog kritikal seputar satu projek penyelidikan tentang pengajaran kelestarian menerusi peribahasa tradisional dari Malaysia dan Kazakhstan dalam bengkel pembuatan zine di sebuah universiti di UK. Berdasarkan gabungan renungan kami dan para pelajar, beserta karya seni zine mereka dan peribahasa tradisional, kami berdialog merentas dua tegangan berkaitan cabaran pembelajaran berasaskan peribahasa sebagai pertalian atau pencedokan nyahkolonial, serta politik dan pedagogi pembuatan zine. Menerusi tegangan-tegangan ini yang mendedahkan amalan-amalan yang berserabut, ambivalen dan masih belum selesai di universiti neoliberal, kami menawarkan beberapa renungan untuk penyelidik dan pendidik yang terlibat dalam praksis nyahkolonial dan berasaskan seni.

Introduction

I think it [is] a really creative and interesting way to look [at] different subjects especially sustainability … it gives it a sense of being a grassroots type of connection.

I thought that it was a really wonderful way to connect the environment and culture, as throughout human social development these have historically been entwined.

The workshop was part of a collaborative year-long research project to identify local ways of knowing about sustainability through the transmission of traditional proverbs in Malaysia and Kazakhstan. The research design of the project included two phases. In the first phase, proverbs published in Malay and Kazakh languages were analysed and thematically coded in relation to the economic, social and environmental dimensions of sustainability. In the second phase, using the proverbs as inspiration, a zine-making workshop on the theme of sustainability was developed. Proverbs, as traditional sayings, philosophies and aphorisms, have historically been integral to local epistemic ecosystems in these countries (Matyzhanov Citation2020; Salleh Citation2020). They demonstrate how contextualised worldviews about sustainable development are already present across generations, shaped and rooted in community and everyday life around the world. Yet, even in these contexts, existing studies on sustainability in higher education rarely engage with this knowledge (Chankseliani, Qoraboyev, and Gimranova Citation2021; Saleem et al. Citation2023). Anglophone higher education scholarship focuses on the Western sustainability definitions used by international organisations such as the United Nations. However, one might find such definitions of sustainability which are not grounded in rich contextual knowledge systems of the Global South exclusive, limiting and narrow.

Meanwhile, the use of zines as a creative, arts-based approach is rooted in the independent publishing spirit of both popular and alternative cultures, including the history of resisting dominant practices through punk, feminist and anti-racist movements (Duncombe Citation1997). A long-time zine artist and educator, Scheper (Citation2023, 21) describes zines as ‘small, hand-made, analog, low-cost, low-circulation publications … expressions of music fandom, others are more like confessional diaries, and still others are small manifestos filled with poetry, homemade comics, quotes, clippings, and photographs’. Historically there have been diverse types of zines focusing on personal identity and sexuality (perzines), art zines with drawings and creative text, fanzines dedicated to a particular music genre, band, or literary work, to name a few (Boellstorff Citation2004; Thomas Citation2009; Weida Citation2020). Whilst complete analysis of the history and typologies of zines as an art form is outside the scope of this article, we recognise the richness of the scholarship on zines which informs this study. For instance, Capous Desyllas and Sinclair (Citation2014, 299) highlighted the pedagogical usefulness of zines as they promote learning in a dialogic manner, awareness of power imbalances in a society and ‘an opportunity to teach our students that their voice has as much validity, legitimacy and power as a well known author.’

As part of the workshop for this project, zines presented a non-conventional approach to engaging students in reflecting on the traditional proverbs as collaborators in producing artful interpretations associated with sustainability. At one university in the United Kingdom, the workshop was held outside of the formal curriculum and positioned as a one-off wellbeing opportunity for interested undergraduate and postgraduate students during the semester. The pedagogical aim of the workshop was to trial an approach of learning and communicating about sustainability through traditional proverbs and zine-making, with the hopes of eventually integrating the approach into relevant modules at the university in areas such as sustainability, international education and communication. During the workshop, participants were provided with a set of Malay and Kazakh proverbs related to sustainability as prompts, organised under the broad themes of environment, society and economy, though we have found the proverbs offer rich overlaps between these themes. The participants then produced interpretations of their selected proverbs in the form of drawings, collages, and textual reflections, guided by us and the zine artist Dr. Molly Drummond who supported our workshop design and zine production. Before, during and after the workshop, we also recorded our own reflections about the project in the ethnographic tradition of acknowledging our insider role, focusing on the workshop development and implementation, how to engage participants in creative interpretations, as well as our experiences facilitating the process.

Based on the artistic contributions produced during the workshop, we assembled an art zine called Telaga Zher. A fusion of the Malay word ‘Telaga’ (well or water spring) and the Kazakh word ‘Zher’ (soil) captures the essence of the zine as a ‘source of nourishment and creative energy, rootedness and earthiness, digging and crafting with our hands collectively.’ In addition to the workshop contributions, the zine also provides details of the project, interactive activities on how readers can produce their own artworks and mini-zines, a list of references for the proverbs from Kazakhstan and Malaysia, as well as blank spaces for self-reflection. Telaga Zher was printed in colour, with a total of 35 pages and in A5 size. Following its publication, physical and digital copies of the zine were distributed among the participants as well as peers in our research and artistic networks. The first author has also used the zines in a workshop for a new undergraduate module on educational developments around the world. Based on the suggestion of our collaborator Molly, copies of the zine were donated to an arts organisation in the vicinity of the university to add to their archive. We also donated some copies to TOKOSUE, an independent bookstore in Malaysia, and shared it online with environmental activists and scholars in Kazakhstan, United States and the United Kingdom. Copies of the Telaga Zher was also shared with Kazakhstan’s science and higher education ministry officials, the minister himself, business leaders and educators. Telaga Zher continues to find new life as it is circulated in artistic and pedagogic spaces.

In this article, we enact a critical dialogue to reflect on the twists and turns of this project across its various stages. In the next section, we elaborate on the dialogic approach to this article, before presenting the tensions from this project. We conclude with a set of reflections for teachers and researchers at the intersection of decolonial and arts-based praxis.

Critical dialogue as meta-method

We attempt to dialogue through the following question: What ethical and political considerations does zine-making raise in teaching and learning across knowledge systems and artful expression? We foreground the dialogue form as a meta-method for reflexively understanding how we sought to make knowledge about teaching sustainability through traditional proverbs and zine-making. We draw primary inspiration for the structure of our dialogue from the interactive, conversational example of bell hooks and Ron Scapp in Teaching to Transgress: Education as a Practice of Freedom (hooks Citation1994). In their dialogue, the two scholars traversed the various dimensions of their teaching practice by weaving in teaching experiences, anecdotes of encounters with students and references to key thinkers as a means of creating a teaching community. In a similar fashion, we eschew the conventional tone and structure of a typical academic article by presenting a dialogue here characterised by moments of doubt, ambivalence, surprise and wonder. Doing so enables us to unveil the intimate, messy, contingent, ambivalent, back-and-forth work of method in this research process (Law Citation2004). Within the context of decolonising higher education research, adopting a dialogue form also enables us to fruitfully engage with multiple stories rooted in our identities and commitments, interacting around common and divergent themes in a shared landscape, thereby highlighting the possibilities of various ways of making knowledge (Montgomery and Trahar Citation2023).

Echoing the claim by Wegerif et al. (Citation2009, 184), presenting this article in the form of a dialogue requires a necessarily tentative and open-ended stance in our desire to offer the readers opportunity to participate, self-reflect, refute, debate and extend the insights of this dialogue, rather than present ‘an authoritative synthesis on the state of knowledge’ where we position ourselves as experts with universalised insights. Though we strive to lay bare our commitment on certain issues discussed as part of the tensions in this project – such as the question of knowledge and methodological appropriation – we do not always provide concrete prescriptions universally applicable across all teaching and learning contexts in higher education. Instead, we leave room for uncertainty, contingency and humility in this dialogue. This itself is a decolonial posture in that we resist the strand of academic knowledge production premised on ‘the idea of the universal within European thought [that] is based on a claim to universality at the same time as it elides its own particularity’ (Bhambra Citation2014, 120). We address the point on particularity when we discuss our positionality below.

Additionally, through a decolonial stance, we foreground the knowledges and proverbial wisdom from Kazakhstan and Malaysia on sustainability. The dialogue form, though here presented textually, seeks to pay homage to the traditionally oral transmission of such proverbs, later recorded in textual form for documentation. We also embrace an artistic approach as a means of acknowledging that the ‘relationship between research and art can be one of epistemological respect and reciprocity rather than epistemological assimilation or colonization’ (Tuck and Yang Citation2014, 237). Hence, throughout this article, we weave our reflexive dialogue with our reflections recorded before, during and after the workshop, alongside selected proverbs, zine artworks, and students’ reflections from the workshop. Such a collage of materials – an artistic technique common in zine-making – that make up the body of the article follows a similar practice by scholars/artists in their intervention utilising zines within the context of the neoliberal university (Bagelman and Bagelman Citation2016; Capous Desyllas and Sinclair Citation2014; Scheper Citation2023). The empirical components (students’ questionnaire responses and artworks) integrated into this dialogue were based on a study that received ethical approval from the Keele University Research Ethics Committee on 9 May 2023 (REC Project Reference: 0542).

We begin the dialogue below by gesturing to our respective positionalities in relation to teaching and knowledge production, thus giving rise to the conceptualisation of this project. Positionality as a decolonial exposition is crucial to stress that the (tentative) knowledge claims we make in this article are carefully situated within cultural traditions that originate from somewhere particular, placed within broader, historical geopolitics of knowledge production characterised by the tendency to universalise Western ‘canons’ at the expense of, and to the detriment of marginalised populations (Abu Moghli and Kadiwal Citation2021).

Aizuddin: I started thinking about the usefulness of Malay proverbs as a way of knowing when I realised that despite being Malaysian, much of my academic training had its roots in Western institutions, with English as the medium of instruction. It made me reflect on my identity as a Malay in the postcolonial sense, and my earlier schooling via the Malay language when I was younger. Given our shared experience of being educated at the University of Oxford, I am reminded of this striking observation by Alvares (Citation2010, 244) about Western, ‘scientific’ knowledge production that creates a class of ‘’modernizers’, whose distinguishing characteristic, following a period of schooling at Oxbridge, was a thoroughgoing alienation from the life and culture of their own people.’ In contrast, I felt that returning to Malay proverbs offered the potential to think through a different epistemic wellspring while reconnecting with my identity, and in the process countering such alienation in my positionality.

Olga: You raise interesting points about the role of formal academic training in Western institutions in shaping our understanding of what constitutes credible knowledge. I also received all my higher education in anglophone universities where no serious discussions took place about Central Asian philosophy and theories. Traditional ways of knowing were seen as too enigmatic, still are largely seen as not reliable. To me, this systematic lack of trust signals ignorance and prejudices from the Global North academic communities. Philosopher Charles Mills (Citation2007) describes such not knowing as white ignorance. Reconnecting with the proverbs is an attempt to re-engage with the orally transmitted knowledges seriously.

Aizuddin: I see what you mean. Within the context of sustainable development and education that we are both interested in, I am reminded of the way that Stein et al. (Citation2023) highlight the status quo: Western knowledge is acknowledged as correct in offering solutions for the climate emergency, whilst place-based, Indigenous knowledge are disregarded or engaged with superficially. Taking proverbs seriously within the context of sustainability contributes to the broader collective project of foregrounding the epistemic utility of traditional ways of knowing, which should not temporally be retained in a kind of ‘cold storage’ when engaging with our forward-looking desire for sustainable development.

In relation to the second element of our project, what is it about zines as an artform that interested you to merge it with proverbs?

Olga: The global academic knowledge production system is hierarchical, where publications in prestigious English language journals receive more attention, trust and engagement in higher education classrooms (Marginson and Xu Citation2023; Mills et al. Citation2023). It is impossible to discuss all injustices that take place in higher education within this dialogue, but they might range from physical barriers of representation in university teaching roles, promotion rejections, unequal access to funding based on the researcher’s gender, and race to epistemic injustices, where personal or group knowledges are subjected to stereotyping, marginalisation and exclusion (Koch Citation2020). To address the injustices, decolonisation movements take place around the world. Students are asking for more diverse knowledges in the classroom. That said, using zines creates the opportunity, big or small, to engage with the grassroot knowledges in multiple languages and artistic mediums in a creative, inclusive and healing way (Boellstorff Citation2004; Scheper Citation2023). I am delighted students described their experiences as ‘wonderful’, and relaxing. Yet, there is a danger to romanticising the past and essentialising non-Western cultures in the process of foregrounding them.

Tension 1: proverbial learning as decolonial connections or appropriation?

Olga: How do we then ensure that these proverbs from Kazakhstan and Malaysia, as local ways of knowing, are engaged with seriously and with care, as opposed to a tokenistic way in this project?

Aizuddin: You raise a crucial tension that needs to be navigated carefully when it comes to the interpretation and consumption of proverbs across languages. In the workshop, the proverbs in Malay and Kazakh languages were accompanied by literal translations into English, as well as interpretations provided through our own familiarity with the language and cultural contexts, coupled with scholarly interpretations where available.

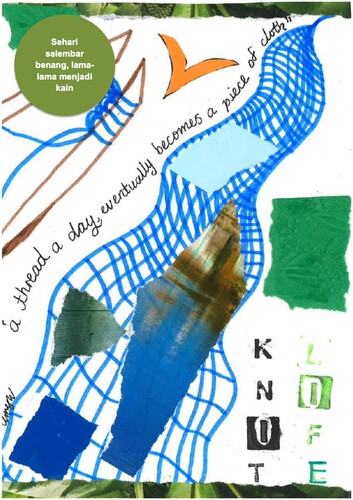

The literal translation into English and the visual nature of some proverbs perhaps provide the most accessible entry point for them to produce an artistic contribution. One of the students worked with the Malay proverb Sehari selembar benang, lama-lama menjadi kain which translates to ‘A thread a day, eventually becomes a piece of cloth’ and produced the artwork reflected in .

Olga: In the artwork above, working with the Malay proverb prompted the student to connect multiple issues with each other, that bigger systems and life itself, consist of smaller, everyday actions and one needs to thread them carefully. In the case of higher education spaces, they are not neutral, and many Global North universities excluded non-Western knowledges from the formal curriculum precisely because of their complicity in the colonial processes (Stein Citation2022).

Aizuddin: This reminds me of instances when non-Western knowledges are included, but they can be tokenistic. For instance, proverbs can be presented as fringe alternatives as add-ons compared to the universalised, superior Western knowledge about sustainability. The other risk is when proverbs are appropriated as quaint abstractions from the contexts in which they are generated. What we sought to do in this workshop is to suggest that learning can be generative when traditional proverbs and their contexts are foregrounded as worthy of serious engagement too in the ecosystem of knowledge about sustainability.

Olga: Remedying ongoing epistemic injustices while avoiding tokenistic inclusive initiatives is not an easy task. So, how do we remain vigilant of the negotiation between the desire for intercultural learning and questions of extraction and appropriation in our project?

Aizuddin: This reminds me of Jefferess’ (Citation2016, 89) argument that ‘taking up other’s ideas in the interest of intercultural understanding or social justice can be just as exploitative as the commodification with which cultural appropriation is associated.’ While I acknowledge this point, I think there is a possibility of engaging with ideas across cultures in ways that are ethical and careful. Otherwise, various spaces of learning become insular, and the possibility of a common set of concerns and understanding is impeded. In terms of how we sought to avoid appropriation, I suppose we paid self-reflexive attention to the identities, histories, and cultural proximities we both bring in relation to the proverbs used in this project. This is to say that we were mindful that these proverbs are rooted in particular contexts, and we aimed to utilise them as part of the pedagogical effort of ‘exchange and repair’ that gestures toward what we can think of as collective learning to forge decolonial connections across the Global North and South, reflected in the zine Telaga Zher:

We are living in a world with challenges associated with climate change, widening inequality, the curtailing of democracy, and social isolation despite increased connectivity … Across the Global North and South, the possibilities of exchange and repair remain. Together, how can we learn from traditional proverbs to (re)imagine ways of tackling such contemporary problems, in hopes to live more sustainably on this planet?

Olga: There is always a risk, but I do think students themselves did an excellent job at developing very nuanced and considerate interpretations of the proverbs. This is not to say this process was easy. One student in the post-workshop survey shared that engaging with the proverbs was ‘difficult but rewarding.’ The fact that they stayed with the difficulty, conversed with other participants and after all enjoyed the activity was a testament to this useful learning experience. Mediated by the proverbs, students have not only learned about other cultures but also developed a cross-cultural decolonial connection around the environment and sustainability, which is a counterpoint to appropriation:

Using proverbs reminded me about the connection humans have had with the land for thousands of years, and how this has been central to our survival. When our lives were so directly and visibly connected to the environment we used proverbs about the environment to explain the world around us. Recently, I’ve heard our minds explained through technological terminology … To me, this shows our increasing disconnection from the environment; however, uncovering proverbs and wisdoms shows that we can relearn some of these connections by again focusing on sustainability and our connection to the environment.

Olga: Whilst I agree that our positionalities informed the considerate engagement with the proverbs, in my view, in order to avoid exploitation and cultural appropriation in a classroom or in wider learning spaces, we need to focus on developing capacities to hear different sides of the argument, being open to changing one’s preconceived beliefs in response to new knowledge rather that primarily focusing on engaging with some issues based on one’s identity or belonging to the group whose culture is discussed.

Aizuddin: Yes I agree, these are important self-reflexive considerations too. What else have you observed in terms of the impact of encountering the proverbs among the participants?

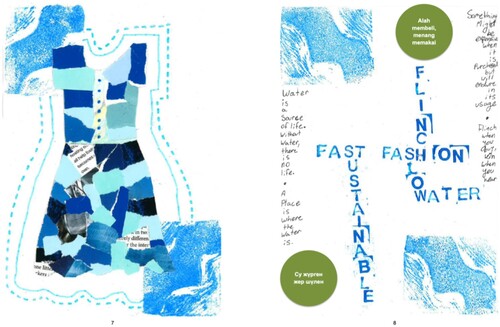

Olga: What is significant about students’ learnings through our workshop is that engaging with the proverbs specifically on the topic of sustainability helped them to consider the intersection of various issues. For instance, in the student combined the interpretations of the two proverbs in one image, that in the human desires to look beautiful, fast fashion companies misuse water, so visually the river is interrupted.

Aizuddin: Yes, I found it to be such a powerful, multi-layered depiction of a sustainability issue captured through the combination of visual and textual elements. There is the word play element in the crosswords – fast, sustainable, flinch, fashion, slow, water – that perhaps show the kind of contradictory crossroads we are at in terms of our consumption patterns and treatment of the environment. The patchy, collage element in the dress may suggest the various sources that come together from different geographies and components of the supply chain. To me, this reflects how the proverbs are taken seriously as decolonial knowledge that provide insights on contemporary challenges of sustainability, enabling the formation of connections across various issues.

Olga: I agree. The student’s artwork inspired by the proverbs also reflects important themes discussed by decolonial thinkers as well on the issue of systematic neglect of peoples and cultures outside the North American and European contexts by the dominant world economies that extract the natural and human resources in the Global South in the pursuit of nationalist economic gains. Mignolo (Citation2012, 97) observes that ‘an economy of accumulation and growth, based on exploitation, land appropriation and poisoning of the planet and of people, cannot by its very nature allow or support de-colonial cosmopolitan projects and/or decolonial dialogue among civilizations.’

Aizuddin: Another significant benefit of foregrounding proverbs in the workshop is that it enabled students to draw on the proverbs as practical, grounded resources on sustainability. For instance, one of the students reflected: ‘I think the proverbs gave substance to big intangible ideas and gave me a practical way to think about sustainability.’ A proverb like Alah membeli menang memakai (Flinch when you buy, win when you wear) says so much about avoiding the pattern of wasteful consumption. Something might be more expensive to buy at first, but will endure in its usage over a long period. Pedagogically speaking, it is important that students found proverbs helpful in answering the how question, as in how to learn and think about sustainable living in terms of its economic and social possibilities. However, I do still have a concern about appropriation, but this time in relation to the incorporation of the tradition of zine-making as pedagogy within the university.

Tension 2: zine-making politics and pedagogy

Olga: Could you elaborate on what do you mean by the appropriation of zines?

Aizuddin: Duncombe (Citation1997, 135) provides the case of how zines as an erstwhile marginal form attracted the attention of mainstream marketers in the age of consumer culture due to the allure of ‘authenticity’ in zines, referring to ‘primary connection between individuals and their lives, passions and desires; home-grown, do-it-yourself authenticity’. Within the context of higher education, the appropriation of zines would refer to its absorption into a conventional, elite space of knowledge-making, thereby muffling its radical politics. Universities, as neoliberal sites governed by the grammars of intellectual property, competition, quantification, commodification, authorisation, prerequisites, specialised training, and professionalism, appear antithetical to the autonomous, amateur and anarchist spirit of zine-making.

It seems to me the challenge of appropriation of zines cannot be separated from the problematics of hierarchies in knowledge production in neoliberal higher education. The incessant need for quantification, for instance, may position students’ textual academic output as being more valued, serious and legible compared to say, an artwork in a zine. The latter, a slow, contemplative endeavour could be read as lazy work, a waste of time. One might ask if that time could be better spent writing 1,000 words for an essay, a quantified effort? I’m thinking here of what Shahjahan (Citation2015, 490–491), in tracing the colonial technology of linear time, observed: ‘Eurocentric notions of time were used to sort individuals into opposing categories such as intelligent/slow, lazy/industrious’. Today, this manifests as neoliberal tendencies experienced in higher education as the intensification of time as a commodity that affects both students and academics.

I suppose to acknowledge and foreground the artistic quality of zine-making, and the staging of its attendant spaces of care and slow time for informal learning; these amount to a politics of resisting the neoliberal impulse of the university (Bagelman and Bagelman Citation2016). To put this in another way, to ‘appropriate’ zine pedagogy into higher education, despite all its dilemmas, may contribute to the strategic, political bulwark against intense neoliberal tendencies shaping students’ learning experiences. However, I hesitate to be too optimistic about this. For instance, grading students on their zine contributions – ascribing some form of aesthetic or representative judgement – may run counter to the ethos of zines as modes of radical expression that defies guidelines and seek to defray power imbalance and hierarchies (Capous Desyllas and Sinclair Citation2014). When absorbed into the neoliberal university, I wonder what becomes of the counter-culture spirit of zines as a mode of pedagogy?

Olga: It seems there are tensions and contradictions as to what pedagogical role zines might play and to what extent their revolutionary roots can be honoured. Some see them as fleeting reflections, whilst Du Laney, Maakestad, and Maher (Citation2022) conceptualise zines as relationship building tools within and between the communities of learners. Zines can be used as activist tools in addressing environmental racism issues (Velasco, Faria, and Walenta Citation2020). Sharing your concerns on misappropriation of the radical potential of the zines by the neoliberal higher education system, there are ways to minimise the risks, I think. For instance, by centring the inclusive co-production processes.

It is not only the final zine that matters to me but also how it was developed. That is why I liked that during the workshops we could play contemporary Kazakh music and the intercultural exchange sparked by the initial interest in the proverbs extended into wider areas of cultural learning. Also, whilst students were working on their artistic contributions, the workshop – which was held outside of a formal module – provided the space for listening, pausing, resting. These reflections were echoed by one participant: ‘I thought that it was a wonderful break from the assignments that I had been writing, but as intellectually stimulating and educational as I was practicing what I was theoretically writing about in my assignments.’ I agree with Les Back here that in contemporary societies there is such an emphasis on speaking up, that the act of listening in building inclusive multicultural societies is at times overlooked (Back Citation2007). Also, in an age of individualised assessments, it almost seems as if spending time on a joyful collective learning experience is an act of resistance in itself.

Aizuddin: I agree, the kind of collective setting of zine-making enabled the creation of a kind of sanctuary for students in the neoliberal university, which is an important intervention. One student remarked that it was ‘a stressful day for me when I passed by the workshop’. Also, the student’s feedback you referred to before suggests that zine-making provided a kind of relief from the drudgery of conventional modes of teaching and assessment. By participating in the zine workshop as a mode of informal learning in this case, perhaps the students are engaging in zine-making as a means of ‘repurposed productivity’, in the words of Scheper (Citation2023). Students were able to take charge of how they used their learning time and space outside of the way they are mostly valued, which is time in formal education, timetabled down to the days and hours.

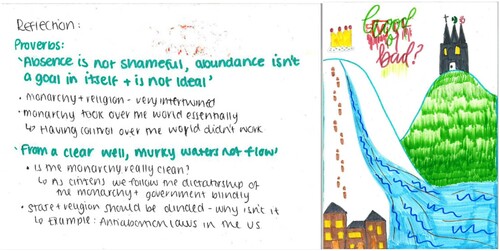

But to return to the question of politics, I do believe that the artistic articulation by students in the zine Telaga Zher does gesture to some of their concerns associated with sustainability. Students produced artworks that gesture towards individual agency, authoritarian tendencies through monarchy and religion, as well as fast fashion. This is not surprising given zines have long enabled political expression, critique and oppositional stances within marginalised social and artistic spaces (Zobl Citation2009). As an excellent representation of such expression, shows one student's artwork and accompanying reflection based on the English translation of Kazakh and Malay proverbs as follows:

Figure 3. A student's artwork and reflection critiquing monarchy and religion inspired by two proverbs.

Kazakh proverb: Жоқтық ұят емес, Тоқтық мұрат емес (literal translation: Absence is not shameful, abundance isn’t a goal in itself and is not ideal)

Malay proverb: Dari telaga yang jernih, tak akan mengalir air yang keruh (literal translation: From a clear well, murky waters do not flow)

What else about the politics and pedagogy of zine-making have you observed through this project?

Olga: Given the multifaceted aspect of the climate crisis, how do we build communities that would engage with the activists, researchers, administrators, staff in general? Zine-making workshops provide spaces to foster such dialogues, and the proverbs used as prompts served as intergenerational cultural bridges. Even in our workshop, members of staff of the university participated too. Students are able to see that lifelong learning is important. Many critical pedagogies exist but I think arts-based methods open the spaces for reflections on one’s positionality and the serious issues in a somewhat therapeutic way. There is a rich scholarship on art, self-esteem building, and cultural citizenship among children (Thomson and Hall Citation2023). In it, it is frequently noted that engaging with arts is helpful for alleviating stress and even building political skills and knowledge. However, art and play seem to diminish at the higher education level and our project shows the usefulness of reclaiming the place of arts through zine-making in the neoliberal university. Perhaps this is also a political move to centre the importance of zine-making as a pedagogical approach to support students so they can mobilise around the important issues of climate change and sustainability.

Concluding reflections

Aizuddin: In this dialogue, we have navigated the tightrope of two tensions in reflecting on the methodology of our project on traditional proverbs and zine-making in sustainability. We discussed the care and concern around working with culturally rooted traditional proverbs that may lose their specificity during intercultural learning, guided by serious consideration of positionalities. The politics associated with zine-making led us to consider the potential of the workshop space and the eventual zine in forging a kind of critique, however tentative, of and beyond the neoliberal university. The ethical concern of appropriation of proverbs and zine-making in the project of knowledge production in higher education has also animated our dialogue. Recently, a scholar observed that these tensions which surfaced in our project reflect a ‘stretching’ of what counts as knowledge that is deemed valuable in the academy. I think it is useful to frame these tensions within the nexus of decolonisation and pluriversity in higher education. In this way, proverbs and zines become crucial tools in a project where Ndlovu-Gatsheni (Citation2021, 78) calls for

the necessity of the concepts of intercultural translation of knowledge, mosaic epistemology/epistemology of conviviality, and ecologies of knowledges [and] the importance of a decolonised pluriversal higher education freed from instrumental market-informed imperatives of commercialisation, commodification of knowledge, and profit accumulation.

Both of my proverbs seemed quite literal, so it was tricky not to just directly portray what the proverb said. Later, I realised that people were drawing different connections and interpretations of my work which helped me to see the worth and multiple interpretations … It reminded me that part of the beauty of art is sharing it, as the discussion can be what is truly beautiful.

Aizuddin: Considering these tensions, how might we then offer some reflections for researchers and teachers engaging in decolonial and arts-based praxis? Your point about epistemic injustice is an important one.

Olga: Here, Brust and Taylor (Citation2023, 570) offer useful pointers for what researchers and teachers can do, which I think is also applicable in relation to the context of our project:

Educators committed to resisting epistemic injustice may seek to expand their own knowledge and understanding in order to counter the risks of ignorance and bias they might bring into their faculty roles. They can build connections with other faculty to share pedagogical strategies and to create or strengthen coalitional efforts to push for structural changes. Within their classrooms, they can establish norms for discourse that are rooted in recognition of the situatedness of individual knowers and of learning as a collaborative, collective practice.

Aizuddin: One student told us ‘This was a transformative experience for me, and I was treated with such kindness from the moment I said hello. This made it a safe space for creativity and intellectual thought’. Without creating that space where students may feel a sense of belonging, play, and community – important affective considerations – it would be more challenging to render an understanding of ‘the theory behind this work and the power of it in practice’, in the follow-up words of the student above. In this way, I am reminded of Bhattacharya’s (Citation2019, 123) stance, which we can pass on to other researchers and teachers engaging in decolonial work and arts-based praxis, a call to centre ‘our own forms of absurd practice that are intentionally nonsensical, imaginative, playful, and creative, thereby opening a portal for inner journeying or even journeying to other realms of being and knowing’.

Olga: Also, decolonial work is calling for the engagement with knowledges developed in multiple languages. In our small collective zine, so many languages interact with each other as whilst the zine focuses on two languages, during the workshop students shared the proverbs from their own cultural context as well! It is important to know that engagement with the proverbs shows that thinking about preserving nature, the fundamental roles rivers, trees, fresh air, animals play in the well-being of the planet predates the Sustainable Development Goals. Not engaging systematically with the research and knowledges in multiple languages and that was historically transmitted orally is problematic and might even be called erasure. Kazakh writer Gerold Belger (Citation2001) dedicated his career to theorising translation as a particular form of knowledge creation in postcolonial Central Asian contexts. Many of his peers wrote and spoke about the importance of multilingual research in Kazakh, Russian, and English languages – Professor Seit Kaskabassov, Amantai Akhetov, just to name a few …

Aizuddin: On that point of erasure, an important consideration for teachers interested to engage in similar work is to explicitly foreground the context when engaging in decolonial, arts-based research on pedagogies. This is a stance to avoid appropriation. What we have found in our research and dialogue is the need to respect, acknowledge and foreground the genealogy of these practices we bring into our methodology. Not only have they always been there, as you have highlighted, but they are steeped in specific histories and politics. Traditional proverbs come from somewhere particular, even when we attempt to translate and offer them for intercultural learning. Zines originated from various countercultures that resist and critique mainstream modes of communication and consumption. Attending a zine-making workshop at TOKOSUE, an independent bookstore in Malaysia reminded me of the need to learn about the (local) histories of zine-making, not just how to make zines. To insist on integrating these contextual dimensions into our contact with students is to link them to that genealogy and to hold space for the complexity and contradiction of such borrowed practices within the walls of the neoliberal academy. Perhaps in this way we are also inviting our students to inhabit the very tensions we have discussed here!

Olga: I agree. Context matters, of course, and temporal aspects. It is time-consuming and laborious to develop such project giving due credit to everyone involved, but necessary and rewarding. Also, whilst our project was small in scope, it focused on one of the most important issues of our time – climate change – and showed the creative potentials of making the education process more representative of the world we live in through a zine-making artistic activity elevating the proverbial wisdom of the peoples of Kazakhstan and Malaysia.

Aizuddin: Indeed, foregrounding traditional proverbs in the context of teaching about sustainability and sustainable development may enrich the epistemic space of universities, within the urgent context of the climate crisis and related ecopedagogies (McCowan Citation2023; Misiaszek Citation2023). We hope that coupled with zine-making, exposing students to these intercultural, creative experiences – with origins outside the academy – can support them to thoughtfully navigate the world in the pluriversal ways of conviviality, relationality, and radical interdependence (Escobar Citation2018). Our small project joins the chorus of others sharing the same concerns around sustainability and the environment in our work with students in higher education.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank our collaborator Dr. Molly Drummond for the teachings and support with zine-making in this project, as well as the students and staff at Keele University for their creative contributions to the zine Telaga Zher. We also thank the anonymous reviewers for their generous and insightful input which enriched this article tremendously.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 We acknowledge the contested nature of the term ‘Global South’. In this paper we use it without normative assumptions in relation to the degrees of perceived development of the countries discussed but to delineate the traditionally excluded and marginalized epistemic communities of Central and Southeast Asia in the global higher education research system.

References

- Abu Moghli, M., and L. Kadiwal. 2021. Decolonising the curriculum beyond the surge: conceptualisation, positionality and conduct. London Review of Education 19, no. 1: 1–16.

- Alvares, C. 2010. Science. In The development dictionary: A guide to knowledge as power, edited by W. Sachs, 243–259. London: Zed Books.

- Back, L. 2007. The art of listening. London: Bloomsbury.

- Bagelman, J., and C. Bagelman. 2016. Zines: crafting change and repurposing the neoliberal university. ACME: An International Journal for Critical Geographies 15, no. 2: 365–92.

- Belger, G. 2001. Translation studies of ilyas zhansugurov. Almaty: Galym.

- Bhambra, G.K. 2014. Postcolonial and decolonial dialogues. Postcolonial Studies 17, no. 2: 115–21.

- Bhattacharya, K. 2019. Theorizing from the streets: De/colonizing, contemplative, and creative approaches and consideration of quality in arts-based qualitative research. In Qualitative inquiry at a crossroads: political, performative, and methodological reflections, eds. N.K. Denzin, and M. D. Giardina, 109–25. London: Routledge.

- Boellstorff, T. 2004. Zines and zones of desire: mass-mediated love, national romance, and sexual citizenship in Gay Indonesia. The Journal of Asian Studies 63, no. 2: 367–402.

- Brust, C.M., and R.M. Taylor. 2023. Resisting epistemic injustice: The responsibilities of college educators at historically and predominantly white institutions. Educational Theory 73, no. 4: 551–71.

- Capous Desyllas, M., and A. Sinclair. 2014. Zine-Making as a pedagogical tool for transformative learning in social work education. Social Work Education 33, no. 3: 296–316. doi:10.1080/02615479.2013.805194.

- Chankseliani, M., I. Qoraboyev, and D. Gimranova. 2021. Higher education contributing to local, national, and global development: new empirical and conceptual insights. Higher Education 81: 109–27.

- Du Laney, C., C. Maakestad, and M. Maher. 2022. The pedagogy of zines: collaboration, creation, and collection. In Integrating Pop culture into the academic library, eds. M. E. Johnson, T. C Weeks, and J. P. Davis, 169–86. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

- Duncombe, S. 1997. Notes from underground: zines and the politics of alternative culture. London: Verso.

- Escobar, A. 2018. Designs for the pluriverse: radical interdependence, autonomy, and the making of worlds. Durham: Duke University Press.

- hooks, b. 1994. Teaching To transgress: education as the practice of freedom. New York: Routledge.

- Jefferess, D. 2016. Cosmopolitan appropriation or learning? relation and action in global citizenship education. In Globalization and global citizenship: interdisciplinary approaches, eds. I. Langran, and T. Birk, 87–97. London: Routledge.

- Koch, S. 2020. Responsible research, inequality in science and epistemic injustice: an attempt to open up thinking about inclusiveness in the context of RI/RRI. Journal of Responsible Innovation 7, no. 3: 672–9.

- Law, J. 2004. After method: mess in social science research. New York: Routledge.

- Marginson, S., and X. Xu. 2023. Hegemony and inequality in global science: problems of the center-periphery model. Comparative Education Review 67, no. 1: 31–52.

- Matyzhanov, K. 2020. Kazakh family folklore. Almaty: Kazakh University Press.

- McCowan, T. 2023. “The climate crisis as a driver for pedagogical renewal in higher education. Teaching in Higher Education” 28, no. 5: 933–52. doi:10.1080/13562517.2023.2197113.

- Mignolo, W. 2012. De-colonial cosmopolitanism and dialogues among civilizations. In Routledge handbook of cosmopolitanism studies, ed. G. Delanty, 85–100. London: Routledge.

- Mills, C. 2007. White ignorance. In Race and epistemologies of ignorance, eds. S. Sullivan, and N. Tuana, 26–31. Albany: State University of New York Press.

- Mills, D., P. Kingori, A. Branford, S. Chatio, N. Robinson, and P. Tindana. 2023. Who counts? Ghanaian academic publishing and global science. Cape Town: African minds.

- Misiaszek, G.W. 2023. Ecopedagogy: Freirean teaching to disrupt socio-environmental injustices, anthropocentric dominance, and unsustainability of the Anthropocene. Educational Philosophy and Theory 55, no. 11: 1253–67.

- Montgomery, C., and S. Trahar. 2023. Learning to unlearn: exploring the relationship between internationalisation and decolonial agendas in higher education. Higher Education Research & Development 42, no. 5: 1057–70.

- Ndlovu-Gatsheni, S. 2021. Internationalisation of higher education for pluriversity: a decolonial reflection. Journal of the British Academy 9, no. s1: 77–98.

- Saleem, A., S. Aslam, G. Sang, P.S. Dare, and T. Zhang. 2023. Education for sustainable development and sustainability consciousness: evidence from Malaysian universities. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education 24, no. 1: 193–211.

- Salleh, M.H. 2020. Peribahasa Melayu: Pemeri Akal Budi. Pulau Pinang: Penerbit Universiti Sains Malaysia.

- Scheper, J. 2023. Zine pedagogies: students as critical makers. The Radical Teacher 125: 20–32.

- Shahjahan, R.A. 2015. Being ‘lazy’ and slowing down: toward decolonizing time, our body, and pedagogy. Educational Philosophy and Theory 47, no. 5: 488–501. doi:10.1080/00131857.2014.880645.

- Stein, S. 2022. Unsettling the university: confronting the colonial foundations of US higher education. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press.

- Stein, S., V. Andreotti, C. Ahenakew, R. Suša, W. Valley, N.H. Kui, M. Tremembé, et al. 2023. Beyond colonial futurities in climate education. Teaching in Higher Education 28, no. 5: 987–1004. doi:10.1080/13562517.2023.2193667.

- Thomas, S.E. 2009. Value and validity of Art zines as an Art form. Art Documentation 28, no. 2: 27–38.

- Thomson, P., and C. Hall. 2023. Schools and cultural citizenship: arts education for life. London: Routledge.

- Tuck, E., and K.W. Yang. 2014. R – words: refusing research. In Humanizing research: decolonizing qualitative inquiry with youth and communities, eds. D. Paris, and M. T. Winn, 223–47. London: Sage Publications.

- Velasco, G., C. Faria, and J. Walenta. 2020. Imagining environmental justice “across the street”: zine-making as creative feminist geographic method. GeoHumanities 6, no. 2: 347–70.

- Wegerif, R., P. Boero, J. Andriessen, and E. Forman. 2009. A dialogue on dialogue and its place within education. In Transformation of knowledge through classroom interaction, eds. B. Schwarz, T. Dreyfus, and R. Hershkowitz, 181–99. London: Routledge.

- Weida, C.L. 2020. Zine objects and orientations in/as arts research: documenting Art teacher practices and identities through zine creation, collection, and criticism. Studies in art Education 61, no. 3: 267–81.

- Zobl, E. 2009. Cultural production, transnational networking, and critical reflection in feminist zines. Signs 35, no. 1: 1–12.