ABSTRACT

Self-assessment involves students making judgements about their own learning. Self-assessment is promoted widely due to its benefits for lifelong learning. However, students often find self-assessment mechanical, useless and redundant – indeed inauthentic. This may partly result from understanding self-assessment as an instrumental and acontextual practice. We take an alternative approach by focusing on the authenticity of self-assessment. We bring together two research areas that have rarely intersected: self-assessment and authentic assessment. How has research conceptualised authenticity with respect to self-assessment? What could we learn from earlier studies to consider authenticity more meaningfully in self-assessment design? To answer these questions, we conduct an integrative review of 40 studies. We formulate an organising framework that outlines the various dimensions of authenticity in self-assessment. We argue that authenticity is a powerful idea that may bring self-assessment from the margins of higher education to its very centre.

Introduction: self-assessment might be helpful, but is it authentic?

In its broad definition, student self-assessment (hereafter self-assessment) refers to educational practices during which students provide judgements about their own work, products and learning processes. Self-assessment is promoted as a useful practice in higher education policies and curriculum documents globally. There is a long-term consensus that self-assessment, particularly as seen as a part of formative assessment, is beneficial for student learning, metacognition, self-regulation and lifelong learning (e.g. Blanch-Hartigan Citation2011; Falchikov and Boud Citation1989; Yan Citation2022). Indeed, creating self-aware graduates – capable of critically examining their own beliefs and performance – is often considered a core goal of higher education.

Despite this widespread consensus on the importance of self-assessment and decades of research on its value, self-assessment remains a marginal part of current higher education systems. It is often a secondary rather than central feature of teaching and assessment cultures. While self-assessment supposedly centres students – the selves of self-assessment – it is often reported that students find this practice mechanical, meaningless, redundant and not about their ‘self’ (Lew, Alwis, and Schmidt Citation2010; Nulty Citation2011; Yan et al. Citation2023a). As Mann (Citation2010) aptly phrased it, self-assessment is vulnerable to ‘becoming ritualized and meaningless, and a matter of jumping through hoops’ (310). Consequently, students and teachers have been shown to resist particular forms of self-assessment (e.g. Harris, Brown, and Dargusch Citation2018; Nieminen and Tuohilampi Citation2020). Students can be neither honest nor authentic in their self-assessments or reflections but instead produce these strategically for their teachers (De la Croix and Veen Citation2018). Instead, students learn how to perform a certain kind of self-assessment. The reason for this may lie in how ‘good practices’ in self-assessment are currently understood. Self-assessment design questions revolve around technical matters, such as whether students are accurate in their self-assessments (Brown, Andrade, and Chen Citation2015). Current self-assessment practices, no matter how formative or sustainable, are often driven and implemented by teachers rather than being owned by students. As Kasanen and Räty (Citation2002) phrased it, the message of self-assessment for students may be: ‘You can assess yourself as long as you assess the right things in the right way.’ (327)

In the spirit of self-reflection, we showcase one of our own earlier projects as an example of how self-assessment design may be helpful for student learning and metacognition but still be inauthentic. In a quasi-experimental study, students were asked to engage in formative self-assessment tasks, practice calibrating one’s self-assessments over time, and ultimately award their grades. A well-designed, detailed rubric guided this process. The students were provided with various sources of feedback information and were prompted to engage with this to develop their self-assessment skills. All these steps were guided by up-to-date knowledge of educational psychology, and indeed, various desirable student outcomes were identified due to the intervention (Nieminen, Asikainen, and Rämö Citation2021). It seemed that the self-assessment activities supported the learning processes of the study participants. Nevertheless, a subsequent interview study with the same participants revealed that while the students found self-assessment useful, it was also deemed technical and synthetic (Nieminen and Tuohilampi Citation2020). Many students could not always take what they learned about self-assessment in this course context and use it elsewhere: in their other courses or in life outside of university. In other words, self-assessment proved itself helpful but not authentic.

Herein lies the conundrum we tackle in this article. We challenge the conventional idea of self-assessment as a technical assessment practice – unilaterally imposed by teachers – that should promote immediately desirable outcomes such as improved performance or self-regulation. This approach sees self-assessment as a disembedded practice that is not rooted in any particular context but can travel across time, space and contexts (following Giddens Citation1990). While there is no shortage of alternative views that see self-assessment as a social, cultural and political practice, these viewpoints tend to remain in the margins of self-assessment literature; the mainstream approach to self-assessment follows the idea of disembeddedness. In this paper, we wish to contribute to the theory of self-assessment by ‘embedding’ this practice in its context through viewing it through the lens of authenticity. In doing so, we necessarily widen the conventional conceptualisation of what self-assessment is and could be.

Authentic assessment literature has long connected assessment with the ‘authentic’ worlds of work and society, calling for meaningful assessment practices that better prepare students for their futures and reflect what they would find there (Ajjawi et al. Citation2023; Gulikers et al. Citation2008; McArthur Citation2023). However, the research areas of self-assessment and authentic assessment have rarely intersected. In this paper, we ask: What might authenticity mean with regard to self-assessment? Who judges whether a self-assessment activity is authentic? We see these questions as essential to push self-assessment research and practice beyond endless discussions of accuracy and whether students’ judgements echo those of teachers. Being asked to self-assess is far from an authentic act as it shifts agency from the learner to an external agent, the teacher, whereas self-assessment in everyday life more commonly falls within the agency of the learner who engages in it at their own volition for their own benefit. We thus advance the research agenda of understanding authenticity in higher education courses (Ajjawi et al. Citation2023) in the particular context of student self-assessment.

Research objective

Our research objective is to contribute to the theory of student self-assessment by reconceptualising this practice from the viewpoint of authenticity. We pursue this objective by conducting an integrative literature review to examine how authenticity is represented in the literature on self-assessment. This way, we synthesise the fragmented evidence regarding self-assessment and authenticity. As two scholars working with self-assessment, we knew that authentic assessment literature infrequently centres the practice of self-assessment; this is exemplified by earlier review studies on authentic assessment that have barely mentioned self-assessment (e.g. Gulikers et al. Citation2008; Nieminen and Yang Citation2023; Sokhanvar et al. Citation2021). Likewise, as discussed, conventional self-assessment research has not centred authenticity in self-assessment design. However, we anticipated that authenticity might be discussed in greater depth in related literature, such as in self-reflection and reflective practice studies (see the next section). This is why we chose to broaden our definition of self-assessment and incorporate studies on these topics in our review as well. We ask:

How has earlier higher education research conceptualised authenticity with respect to self-assessment?

Overall, this paper sets the agenda of understanding student self-assessment from the perspective of authenticity. In the process, we seek to transcend typical discourses of self-assessment that see student learning and metacognition as central to discussions to focus on how self-assessment can provide authentic learning experiences. We particularly shed light on the ontology of self-assessment by noting how, through self-assessment, students could develop their authentic selves.

Conceptual remarks

In this section, we explore the various conceptualisations of self-assessment. In educational policy, practice and research, student self-assessment is conventionally understood as an assessment practice that asks students to provide judgements about their own work, products and learning processes (Panadero, Brown, and Strijbos Citation2016). Such practices are commonly promoted in curriculum documents and may align with formal assessment and grading practices. In doing so, this standard view places agency in the hands of the person doing the asking and connects self-assessment with the world of assessment, which may explain the focus of self-assessment work on the questions of validity and reliability.

We wish to expand this view. In this paper, we refer to self-assessment by focusing on the design of educational activities during which students provide judgements about their own learning and the authenticity herein. While there is no uniform definition for self-assessment design, many ‘best practices’ are shared widely in research and practice communities. There is a broad consensus that self-assessment provides the most significant educational benefits when seen as a formative rather than a summative practice. Self-assessment has been portrayed as a formative assessment process through which students can calibrate their own learning processes, ideally backed up by a set of criteria and standards and adequate feedback processes (e.g. Panadero, Brown, and Strijbos Citation2016; Yan and Carless Citation2022). These standards and criteria may derive from curricular goals or from students’ own goals and aspirations. Self-assessment has also been framed as a sustainable assessment practice (Boud and Soler Citation2016) that reaches beyond imminent course learning outcomes and develops students’ lifelong learning capabilities (e.g. Tan Citation2008; Yan Citation2022). We acknowledge these varying definitions and note that each conceptualisation of self-assessment – whether summative, formative or sustainable – could learn from the idea of authenticity.

We note that focusing on self-assessment design differs from seeing self-assessment as a capability, skill or competence (cf. Brown and Harris Citation2014). While various skills can be developed through self-assessment designs, our main focus here lies on the authenticity of self-assessment practice. We are interested in both the authenticity of the objects to which self-assessment is applied and the processes of self-assessment in which students engage.

While our emphasis is on self-assessment, various other ideas similarly focus on students’ awareness and reflectivity regarding their learning. These share similar practices in, for example, noticing one’s own practice, utilising inputs and analysing experiences. These other practices often use a discourse of authenticity in their accounts. Some examples of similar ideas are evaluative judgement, reflective practice and self-reflection – all widely discussed in the higher education literature. While we acknowledge that these have been seen as separate fields of work, there is considerable overlap between them and self-assessment. We suggest that we can learn from these close fields and communities of practice even though terminologies and how they are operationalised may differ significantly.

To provide examples of the intertwining of connected ideas in this field, we briefly note the overlaps and differences between ‘self-assessment’ and ‘reflective practices’. Boud (Citation1999) characterised differences between student self-assessment and reflection by noting that reflection ‘occupies a wider territory than self-assessment’ as it ‘involves learners processing their experience in a wide range of ways, exploring their understanding of what they are doing, why they are doing it, and the impact it has on themselves and others (123). Reflection does not always ask students to use existing quality markers or explicit criteria to provide judgements of their work. Even then, research on the authenticity of reflective practices may teach us about what self-assessment design could consider to strive for authenticity. On the other hand, many self-assessment frameworks and models include the idea of reflection (e.g. Yan and Carless Citation2022). This view sees reflection as a subset of a broader self-assessment process. To make matters even more complicated, many studies on reflective practice make use of assessment criteria (e.g. rubrics) and feedback processes in ways that closely remind us about conceptualisations of self-assessment (e.g. Alsina et al. Citation2017). Focusing only on literature using the term ‘self-assessment’ might thus be limiting for a study interested in practices that ask students to provide judgements of their own learning.

Methods

Integrative review

To understand how authenticity could be understood in self-assessment, we conducted an integrative review. The integrative review tradition provides us with the tools to synthesise knowledge from various fields of literature and different disciplines. This is particularly important for our research agenda to consider studies from the various fields of research on self-assessment, self-reflection, reflective practice, and so forth, and integrate these ideas under the banners of ‘self-assessment’ and ‘authenticity’. Our integrative review thus ‘build[s] bridges across communities of practice in the field and uncover[s] connections to other related disciplines.’ (Cronin and George Citation2023, 175) Importantly, integrative reviews synthesise knowledge from both primary and secondary studies (e.g. conceptual studies). We follow the five stages of integrative reviews by Whittemore and Knafl (Citation2005): problem identification, literature search, data evaluation, data analysis and presentation. These steps ensure that our study includes a rigorous literature search phase, separating it from mere conceptual studies.

Literature search

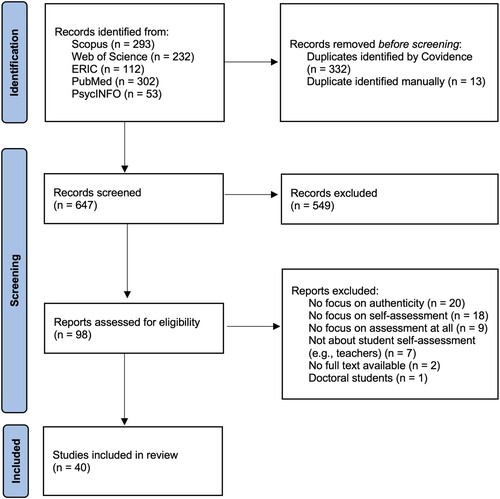

The literature search was conducted using educational databases. It was facilitated in Covidence (www.covidence.org), an online platform for managing literature reviews. Our search protocol did not aim to identify every potential source (cf. systematic reviews) but instead provided us with a meaningful data corpus to address our research question. We used five databases: Scopus, Web of Science (WoS), ERIC (via EBSCOhost), PubMed and PsycINFO (via ProQuest). By using these databases, we aimed to identify sources from many fields of higher education research, such as educational psychology (PsycINFO) and medical education (PubMed), considering that we anticipated the literature being scattered among many differing fields and disciplines. There was no time limitation in the search. The search terms are given in .

Table 1. The search terms (the three search strings were connected with an AND operator).

The inclusion and exclusion criteria for the search process are listed in . Notably, we focused on authentic, naturalistic settings in higher education rather than laboratory-based studies to ensure our synthesis considered self-assessment scenarios in usual course settings.

Table 2. Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Both authors took part in the literature search process () and contributed to screening the titles and abstracts to determine which records should be assessed for full eligibility. In the full-text review, all unclear cases were discussed. Finally, 40 studies were chosen for the final analysis.

Data extraction and analysis

To address our research objective, data extraction and analysis considered earlier literature on authentic assessment to apply this knowledge in the particular context of self-assessment. First, we constructed a data extraction table based on this literature. We extracted basic information about the studies (e.g. year of publication, research objectives, methods and findings), information about the self-assessment design (e.g. whether and how scaffolding, feedback and iteration were used in the reported design), and information about how the study conceptualised authenticity (both implicit and explicit definition, based on our interpretation). Finally, we summarised the contribution of the studies by asking: what kind of novel knowledge did the studies produce about the authenticity of self-assessment? We extracted this contribution open-endedly, using the following deductive categories:

Authentic to the present and future field of work (Ashford-Rowe, Herrington, and Brown Citation2014)

Authentic to knowledge (Nieminen and Lahdenperä Citation2021)

Authentic to the digital world (Nieminen, Bearman, and Ajjawi Citation2023)

Authentic to the self (Ajjawi et al. Citation2023)

Psychological authenticity (Ajjawi et al. Citation2023)

Anything else? Inductive category

The first author extracted 75% of the studies and the second author 25%, with all discrepancies and unclarities being resolved in research meetings. While we kept the analysis sensitive for inductive, new categories, these did not emerge during the analytical process.

The data was then analysed by following Cronin and George’s (Citation2023) formulation of redirection as a way of data synthesis in integrative reviews. Redirection ‘organizes domain knowledge by structuring it in such a way that insights that promote new kinds of research emerge’ (Cronin and George Citation2023, 171). Our theory-driven extraction table enabled us to determine the ‘silos’ of research in this area: where knowledge is thick and where it is thin. Our analysis inductively considered what all the studies under each category revealed about the authenticity of the given self-assessment design. In doing so, it aimed to redirect self-assessment research towards understanding the nuances of authenticity.

Findings

Here, we provide a brief overview of our dataset. We then present five different dimensions of the authenticity of self-assessment as discussed in our data corpus. Finally, we discuss how these studies considered the critical questions of whether self-assessment is experienced as authentic; and who determines what exactly counts as ‘authentic’.

Overview of the studies

Out of the 40 studies, 31 were original, empirical studies, whereas the remaining 10 studies were conceptual in nature. The methods in the 31 empirical studies were primarily qualitative, with six studies introducing quantitative data and analysis processes. The disciplinary contexts varied, with medical education (including nursing) being the most commonly discussed context (19 studies). The studies were predominantly conducted in the Global North, with the exceptions of South Africa (three studies), Chile (one study) and Colombia (one study). The studies were published between 1997 and 2023.

Notably, the studies in our dataset mostly concerned reflection or reflective practices (31 studies). Of the remaining studies, seven explicitly referred to self-assessment, and two used the terminology of evaluative judgement.

Authentic to present and future work (33/40 studies)

Framed through this dimension, self-assessment is portrayed as a practice that should follow the procedures, tools and norms of professional practice. These studies acknowledge that self-assessment needs to equip students with skills for current practice, as well as for emerging practice, while restricting the notion of authenticity to work practices. According to this view, when self-assessment is authentic to students’ potential future work, it develops those skills and competencies needed in future practice, such as lifelong learning skills and evaluative judgement (e.g. Wingrove and Turner Citation2015). This dimension represents the common focus of authentic assessment literature on replicating work contexts and situations (McArthur Citation2023; Ajjawi et al. Citation2023), tying self-assessment to the same tradition.

Many studies discussed self-assessment of authentic work-life skills (Cooke and Matarasso Citation2005; Fergusson et al. Citation2022; Matshaka Citation2021). In these studies, the design of the self-assessment process itself was not considered ‘authentic’. For example, Bußenius and Harendza (Citation2023) developed a quantitative instrument for medical students to accurately self-assess their competence in patient-centred care (for similar self-assessment instrument development studies, see Droege Citation2003; Salminen et al. Citation2014). Here, it was not the process of students answering a survey that was ‘authentic’ but the skills that the survey was targeting. Another frequent example is using an e-portfolio to enable students to self-assess their authentic work-life skills, yet not exactly in ‘authentic’ ways. This was seen in the context of teacher education; while teachers may rarely use e-portfolios as a vehicle to self-assess their skills in authentic work settings, nevertheless, this practice was repeatedly portrayed as an authentic practice (e.g. Espinoza and Medina Citation2021; Southcott and Crawford Citation2018).

However, many studies proposed that self-assessment should reflect authentic work-life practices (Burton Citation2016). This idea challenges the prevalent use of self-assessment forms and sheets in higher education; not because such practices might not meet immediate learning needs but because they could be seen as inauthentic from the viewpoint of authentic work settings. These issues are particularly pertinent in professional degrees, as Lewis et al. (Citation2011) discuss. For example, in a series of conceptual and empirical studies in teacher education, Kearney examined authentic self-assessment that has ‘a direct correlation or relevance to the students’ professional world’ (Kearney and Perkins Citation2014, 3) and thus ‘provide[s] an authentic assessment experience for students that has workplace ready relevance’ (Kearney, Perkins, and Kennedy-Clark Citation2016, 11; Kearney Citation2019). Likewise, Tweed, Purdie, and Wilkinson (Citation2017) pondered that self-assessment design must replicate the reflection-in-action that is authentic in the work of medical practitioners, given that ‘realistic’ and daily self-assessment practices at the workplace are often neither static nor formal (see also Bradley and Schofield Citation2014). Of course, some self-assessment practices in workplace settings are quite formal, such as in the cases of portfolios and performance reviews. Authentic self-assessment tasks could model these practices and scaffold students towards facing them after their graduation. For example, in the study by Stupans, March, and Owen (Citation2013), pharmacy students were asked to keep a reflective journal during their placement in a way that replicated good reflective practice in healthcare settings.

Many studies pondered the limits and boundaries of authenticity in self-assessment. How authentic should self-assessment be? For example, Boshrabadia and Hosseinib (Citation2021) discussed how self-assessment should be practised not in real, authentic settings but via simulations that are ‘replicas or analogies of what they are required to perform within the physical and social contexts of their profession after the point of graduation’ (917). They argue that complex real-world contexts are not easy to replicate and that self-assessment in higher education must always involve limited representations of the complexity of authenticity in order that students not to be distracted by extraneous features. Nevertheless, many scholars argued that self-assessment design must challenge students to prepare for complex workplace situations (see Tremblay et al. Citation2019). Sometimes, such real-world contexts push the ethical boundaries of self-assessment, such as asking students to reflect upon their competencies in a simulated patient death situation (Kim et al. Citation2016). Likewise, Hargreaves (Citation1997) wrote about whether reflective practices in medical education should make use of real patient cases. Hargreaves noted that sometimes, reflective practices in higher education should start as less authentic and scaffold students carefully towards more authentic reflection.

Authentic to the self (13/40 studies)

13 studies portrayed authenticity in self-assessment in relation to their affordances for supporting students’ professional identity development (see Nieminen and Yang Citation2023). Used in this way, self-assessment was not only connected with the immediate learning objectives (e.g. at the course/unit level) but provided students with a vehicle through which to understand their own longer-term processes of identity formation. Vu and Dall’Alba (Citation2014) addressed a similar idea (without writing specifically about self-assessment):

‘Assessment … is not an end in itself. Rather, it is an opportunity for students to learn and reflect on their learning for their personal and career development, in a way that nurtures the spirit of striving for authenticity.’ (788)

Many of these studies considered how self-assessment could provide students with the means of developing their authentic selves (see e.g. Ross Citation2011, Citation2014). In other words, self-assessment was used as a practice through which students developed their personal and professional identities. For example, Nguyen (Citation2013) reframed e-portfolios – a common practice to foster student learning – as a medium for being and becoming: ‘Assessment shifted to an ontological, internal guide to living authentically.’ (145) By constructing their e-portfolio, students narrated the ‘academic, professional, or personal aspects of their lives’ (139), thus reflecting upon the intersections of these various identities (see also Leijenaar, Eijkelboom, and Milota Citation2023). Nguyen illustrates student perceptions of such self-assessment via portfolios:

A freshman engineering major … firmly felt that the ePortfolio ‘really conveys the person that you really are.’ Another freshman mechanical engineering major noted, ‘It’s very clearly me.’ A first-year student explained the ePortfolio process as ‘finding your center point. Grounding yourself in who you really are and who you are with other people.’ These comments all point to how the ePortfolio presents an authentic identity that students may then present to others. (Nguyen Citation2013, 139–140)

Authenticity attained through self-reflection also allows the student nurse to provide care and offer their true self to the patient with genuineness, uniqueness, and congruence (…). When student nurses are authentic, they can build authentic connections with patients, and this will lead to an effective student nurse-patient relationship. (Matshaka Citation2021, 3)

While it is difficult to conclusively prove shifts in critical consciousness and active citizenship, reflection allowed students to make sense of what they had learned and communicate how they perceived their development process, as the literature suggests (…). Their reflections provided indications they had deepened their understanding of a complex and worrying local issue while also demonstrating traits of active citizenship, which resonates with the purpose of critical reflection (…). (Keogh and Corrales Citation2023, 9)

As one student confirmed, ‘autoethnography is so helpful; it validates your own personal experience [and] has provided me with greater links to my past, and stronger foundations for my future practice’. Through this assessment we hoped to facilitate students’ sense of agency in their construction of present and future self as teacher. (Southcott and Crawford Citation2018, 105)

Authentic to the digital world (6/40 studies)

Whereas most of the 40 studies involved some sort of digital enablement of assessment, only a handful of them focused explicitly on authenticity from the viewpoint of the demands of the digital world. Seven studies discussed how the digital could be designed into self-assessment in authentic ways. Here, we have organised these studies loosely based on the literature by Nieminen, Bearman, and Ajjawi (Citation2023) review on digitally mediated authentic assessment.

First, three studies used authentic digital technologies and practices to facilitate self-assessment. These studies challenged the idea of written self-assessment and reflection – which is often the predominant format in higher education – and instead emphasised the affordances of digital technology for authentic self-assessment. Newcomb, Burton, and Edwards (Citation2018) reported that students engaged in reflection more easily when they could record their reflections in audio or video format. Yeo and Rowley (Citation2020) discussed the digital dimensions of authentic e-portfolios, noting that the ‘multi-modal mix of visual, aural and standard textual responses and formats’ of the e-portfolio promoted ‘authentic, creative reflection’ (18). Multimodal, digital formats of self-assessment allowed students to engage in reflection in embodied ways, which was reported by Parikh, Janson, and Singleton (Citation2012) to increase authenticity. The embodied nature of video-recorded reflections enabled students to portray their complex emotions through nonverbal cues such as facial expressions and body language. In these studies, ‘inauthenticity’ was connected to what was regarded as outdated or limited formats of self-assessment, such as writing, that did not consider how students might need to operate in the digital world.

In one study, digital, work-relevant assessment practices were used to foster students’ evaluative judgement (Boshrabadia and Hosseinib Citation2021). This conceptual study introduced an authentic assessment design framework in which students were asked to collaborate with a simulated online agent in a real-world project context and, in doing so, develop their capabilities to provide high-quality judgements in digital spaces.

Two studies by Ross (Citation2011, Citation2014) considered how digitally mediated reflection tasks can develop students’ digital selves. These studies emphasised the importance of placing the broader idea of student identity formation through self-assessment in the context of the digital world (cf. authentic to self). In a conceptual study, Ross (Citation2011) argued that in the digital world, students’ authentic self is a digital construction consisting of ‘offline’ and ‘online’ identities. In a follow-up empirical study, Ross (Citation2014) examined novel, digital forms of reflection tasks that bring together ‘speed, fragmentation and remixability (…) to offer students a more flexible and more digital way of constructing accounts of competence, learning, and experience.’ (97) Such understanding of digitally mediated reflection would, according to Ross, allow students to reflect upon their networked selves in various online and offline environments. As the professional self is networked in online and offline spaces, authentic self-assessment could capture ‘traces’ of such destabilised digital representations.

Authentic to knowledge (3/40 studies)

Three studies explicitly discussed the authenticity of self-assessment from the viewpoint of epistemology, namely, knowledge and knowing. These addressed the question of how self-assessment could align with disciplinary knowledge structures. This viewpoint emphasised that self-assessment practices may look different in, say, social and natural sciences because knowledge is structured differently in these fields. For example, self-assessment may clash with the positivist understanding of knowledge in natural sciences, leading to students perceiving it as an inauthentic practice. On the other hand, in social sciences, where knowledge is not seen to reside outside the knower, self-assessment may provide authentic experiences of knowledge and reflection (see Nieminen and Lahdenperä Citation2021; Tilakaratna and Szenes Citation2024). In other words, these studies conceptualised authentic self-assessment as an epistemic practice (see Ng et al. Citation2015). While this dimension was likely to be implicit in studies across our dataset, only three discussed this explicitly.

Two studies showcased how self-assessment aligned with the knowledge that students need in their future profession. Lalor, Lorenzi, and Justin (Citation2015) discussed how an assessment portfolio allowed student teachers to use knowledge in similar ways as teachers do. In the teaching profession, knowledge is constantly in action: teachers must continuously not only ‘know’ but apply knowledge in classroom situations. The authors argue that typical forms of reflective assessment tasks ‘rarely afford students the opportunity to apply knowledge to key professional scenarios’ in this way (Lalor, Lorenzi, and Justin Citation2015, 45). They asked students to reflect in authentic professional scenarios and, in doing so, aimed to promote ‘reflection-for-future action’ (54). As a part of the process, the students understood how practising teachers use and apply educational knowledge in authentic ways. Similarly, Gibbons (Citation2018) used reflective writing tasks in law education to train students to understand how knowledge is constructed in this discipline. As students wrote their reflective reports, they engaged with knowledge and learned how legislative knowledge is constructed by human agents. For many students, the experience was reportedly transformative as the reflection task enhanced students’ ‘engagement with powerful knowledge’ (Gibbons Citation2018, 13).

Nguyen-Truong et al. (Citation2018) took a more critical approach to the questions of self-assessment and epistemology by showing how reflective practices may not only replicate existing knowledge structures but also push and challenge them. In this study, nursing students were asked to reflect in creative ways, such as through poem-reading and cartooning. In particular, the students were allowed to demonstrate indigenous knowledge in self-assessment by using string figures (see Nguyen-Truong et al. Citation2018 for details). This approach resists the positivist idea of self-assessment as an instrumental practice that should accurately measure students’ learning outcomes. Instead, knowledge and knowing were reframed as relational ideas. The students could link Indigenous knowledge with their self-assessments:

As an innovative technique for nursing education, indigenous knowledge is a multidimensional perspective to observing, understanding, and interacting in the world that honours relationship, interconnectedness, and harmony of all things (…). Further, it accounts for the complex exchange between teaching–learning that includes intellectual, emotional, spiritual and physical domains (…). Indigenous language, for example, cannot be reduced to a process of learning how to pronounce words but requires a commitment to understanding the tribal value system of ideas, beliefs, and feelings. For students, practice of indigenous teaching–learning strategies, through story-telling and string figures, highlights that becoming a professional nurse cannot be reduced to a process of learning how to perform skills but requires a commitment to understanding clients’ stories and the professional nursing value system.

Experiences of authenticity (13/41 studies)

In addition to the above-mentioned four dimensions of authenticity in self-assessment, there was also a prevalent theme in our dataset pondering the critical issue of whether students experience self-assessment as authentic. That is, does the activity feel authentic to students? It could be argued that if students do not perceive something as authentic, in a fundamental sense, it is not authentic, even if others believe it to be so (see Ajjawi et al. Citation2023). This idea has been discussed in authentic assessment literature for a long time. For example, Gulikers et al. (Citation2008) noted that since authenticity is in the eye of the beholder, ‘it is important that assessments are developed that students perceive as being authentic’ (403). Here, we discuss similar ideas amid self-assessment literature.

Many studies explicitly reported students’ experiences of the authenticity of self-assessment. Various design elements were discussed to increase positive accounts of authenticity. For example, Parikh, Janson, and Singleton (Citation2012) reported that making reflection more multimodal through video journaling led students to report that ‘compared with the benefits of written journals, video journaling allowed for greater levels of authentic reflection.’ (40) Tremblay et al. (Citation2019) noted that complex tasks stimulated deeper self-reflection than simplistic ones.

Yet, many studies noted that despite efforts to design authenticity into self-assessment, students often found it inauthentic. This may be due to the authenticity of the self-assessment method itself (eg. the use of simple scales for rating as discussed earlier) or because the main focus of the event was on something not perceived as authentic (eg. a task that students did not see as relevant to practice). Self-assessment tasks were often seen as a ‘hurdle to jump’ (Bradley and Schofield Citation2014, 235) rather than an authentic experience. Mann et al.’s (Citation2011) participants referred to self-reflection as a ‘meaningless game that had to be played to satisfy others’ (1124), revealing tensions between forced and spontaneous reflection. Indeed, self-assessment and reflective tasks were noted as practices that are initiated and facilitated by teachers, for the purposes of teachers. One participant in Newcomb, Burton, and Edwards’s (Citation2018) study aptly commented that ‘There’s not much content to it (reflective writing) it’s just what they want to see. It’s not authentic at all.’ (6)

One remedy for these situations was systematic training regarding the purposes and practices of self-assessment so that students could understand what it was for, how it related to future practice and how it might be done meaningfully. For example, Kennedy and Kennedy (Citation2022) reported that medical students initially felt hesitant to participate in mindfulness practices that aimed to foster self-reflection. In one of the sessions, students were asked to choose a photograph card that best resonated with them: ‘Some viewed this as an artificial approach to reflection, contributing to the hesitant start.’ (84) However, after participating in various communal and multimodal reflective practices, students warmed to the idea. Their participants reported that self-reflection felt more authentic when it was conducted in groups: ‘By verbalizing and discussing their thoughts within the group, the participants believed their reflections to be more authentic. They were less likely to reflect artificially, and suggested that more genuine reflection was elicited.’ (85)

Some studies took a more critical approach and pondered whether it was even possible to be truly authentic in self-assessment amid the prevalent policies, practices and discourses of assessment more generally. For example, Belluigi (Citation2020) explored how formal self-assessment tasks sometimes hindered the development of art students’ artistic selves when embedded in a context with policies rooted in summative assessment. McGarr and Gallchóir (Citation2020) raised the question of whether it is meaningful to posit an authentic self that could be represented in reflective writing. Moreover, they pondered whether reflective practices are designed to encourage inauthenticity as students are asked to confess matters related to their personal lives, leading to much-reported issues with performative reflection (Boud and Walker Citation1998).

Authenticity in self-assessment was also portrayed as a matter of power (McGarr and Gallchóir Citation2020). In the context of reflective writing tasks, Newcomb, Burton, and Edwards (Citation2018) noted that the ‘very act of writing for another impacts on the way in which students engage with reflective writing and can involve performativity, especially with it being assessed’ (8). In this view, required self-assessment tasks in formal education could be argued to never be truly authentic to students as they involve the portrayal of the self to potential or actual assessors. In fact, in exposing their authentic vulnerability and emotions, students risk being hurt (e.g. Newcomb, Burton, and Edwards Citation2018). Moreover, the very idea of authenticity in self-assessment and self-reflection may be rooted in a particular cultural understanding of ‘authenticity’. This was discussed by Naidu and Kumagai (Citation2016), who critically examined the universal idea of reflection in medical education, noting that ‘the uncritical export and adoption of Western concepts of reflection may be inappropriate in non-Western societies’ (317) as they value Western knowledge, marginalising other types of knowing and being.

Discussion

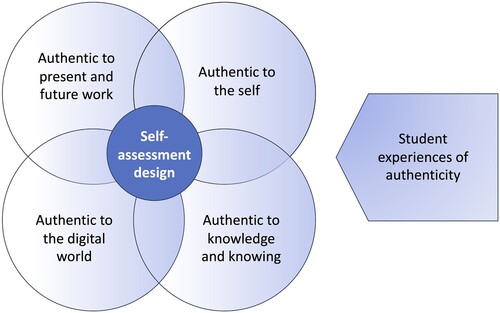

The integrative review of research on authenticity in self-assessment and similar ideas enabled us to identify four dimensions of authenticity in self-assessment: authenticity with respect to the world of work, the self, the digital world and knowledge and knowing (in the order of prevalence in our dataset). It also pointed to the importance of the dimension of whether self-assessment is experienced by students as authentic. We summarise this framework in .

Overall, the literature on self-assessment has not given much attention to authenticity in any one of its many forms. It was only by extending our reach beyond practices that were described as self-assessment that sufficient material was found to complete our review. We wish, therefore, to redirect (Cronin and George Citation2023) studies of self-assessment to a fuller understanding of authenticity in practice, design and research. Traditionally, research on educational self-assessment has drawn on a psychological assessment paradigm focusing on measurement, accuracy and learning outcomes (e.g. Brown, Andrade, and Chen Citation2015; Panadero, Brown, and Strijbos Citation2016; Yan Citation2022, Citation2022b). This means that self-assessment itself has been understood as something universal, acontextual and instrumental; as a disembedded practice that operates across time, space and contexts (Giddens Citation1990). Consequently, social, cultural, political and critical approaches have remained at the margins of self-assessment research (see Nieminen Citation2021; Pitkänen Citation2022; Taras Citation2010) We suggest authenticity is a powerful concept that can sensitise research and practice on self-assessment to its contextual underpinnings. Our review has shown that what counts as ‘authentic self-assessment’ varies greatly in different disciplinary, cultural and institutional higher education contexts. Thus, we argue that it is timely and necessary to emphasise possible varieties of authenticity in the context of self-assessment. The dimensions of authenticity we have outlined could guide future work in analysing and developing ‘authentic’ self-assessment practices.

Our review incorporated various search terms other than ‘self-assessment’, including concepts such as ‘reflection’ and ‘evaluative judgement’. This is typical for integrative reviews that aim to synthesise knowledge from various bodies of knowledge. Yet it must be noted that most of the 40 studies we analysed considered either self-reflection or reflective practices, whereas only seven used the language of student self-assessment. It is thus safe to say that authenticity has been discussed more widely in reflection literature (e.g. De la Croix and Veen Citation2018; Macfarlane and Gourlay Citation2009) than in self-assessment literature (e.g. Kearney and Perkins Citation2014; Kearney, Perkins, and Kennedy-Clark Citation2016). These two fields of literature are rather separate and often characterised by different research paradigms. We conclude that self-assessment research could learn a lot from studies on reflection and reflective practice. Self-assessment research may use the known best practices from its own research tradition (such as by promoting feedback dialogues and self-assessment training; see Yan et al. Citation2023b) and simultaneously instil authenticity in these practices.

The five dimensions identified all provide intriguing lenses for future work on self-assessment. While it is largely understood that reflective practices must echo disciplinary competencies, norms and values and, in doing so, prepare students for their professions, self-assessment research has rarely considered this aspect. Instrumental and universal self-assessment practices are unlikely to sufficiently equip students with the skills they need as future graduates. Our findings showed that research framed explicitly as self-assessment has rather rarely discussed authenticity with respect to knowledge and the digital world. Both approaches are crucially important in contemporary higher education settings. While self-assessment research has acknowledged the importance of knowledge domains (Panadero, Brown, and Strijbos Citation2016), we still know little about how self-assessment could authentically represent disciplinary knowledge structures in a given context. Here, self-assessment research and practice could learn from literature on the epistemology of reflection and reflective practice (see Ng et al. Citation2015; Tilakaratna and Szenes Citation2024). Moreover, digitally authentic practices are needed to ensure that self-assessment adequately prepares students for the increasingly ubiquitous digital future (Nieminen and Yang Citation2023). Further research and practice may consider, for example, how self-assessment with regard to digital tasks could use authentic digital technologies and how it could enable students to reflect upon their networked, digital selves (Ross Citation2011, Citation2014).

Yet, we believe the ontological dimension of ‘authentic to self’ provides the most challenging demand of self-assessment research and practice. After all, self-assessment supposedly centres the students themselves – with their hopes, learning, aspirations and experiences (Yan Citation2022). How can self-assessment be genuinely conducted when criteria for success are not only defined by others, using instruments created by others and take place with regard to subject matter that others think important? Courses are not just about students meeting the unilateral learning outcomes of others but of meeting their own desired learning outcomes, which may not be identical to these. Self-assessment is, perhaps more than any other assessment practice, at risk of compromising authenticity in the common situation in which this practice is carefully designed, initiated, implemented and monitored by teachers; and when self-assessment is not found to be ‘accurate’ (ie. the same as the teacher), interventions are conducted to ensure students become more accurate and honest in their self-assessments. We argue that a profound reconceptualisation of self-assessment is needed to tie it to the ontological dimension of authenticity (Bourke Citation2018). Namely, self-assessment should ‘increase students’ awareness of who they are becoming, as well as about what is required of them to act in defining their stand’ (Vu and Dall’Alba Citation2014, 787) The 13 studies focusing on self-assessment as the means for developing students’ authentic selves provide inspiring exemplars on how to achieve such a goal. By understanding self-assessment as an ontologically authentic practice, the judgements students make about their own learning become a part of a longer-term process of identity formation (Nieminen and Yang Citation2023).

We wish to extend the current conversations regarding self-assessment design beyond the imminent tasks and towards broader approaches regarding curriculum design and programmatic assessment. The organising framework () could be used to analyse and develop self-assessment activities in a whole curriculum. It may be infeasible that a single self-assessment activity aligns with all of the five dimensions of authenticity; yet arguably, students should be provided with experiences of all these dimensions during their studies. For example, we would not be concerned if one single self-assessment task ignores the context of the digital world. However, if during their programme, students rarely or never receive opportunities to engage with digitally authentic self-assessment activities, it could be argued that this programme does not adequately prepare graduates to critically assess their own skills in the digital world.

Finally, based on these findings, we must consider what ‘inauthenticity’ means for self-assessment. Whereas we do not consider authenticity and inauthenticity simply as a binary nor a polarisation (see Ajjawi et al. Citation2023), we see it necessary to elaborate on inauthenticity in the specific context of student self-assessment that has long been known by students themselves to be an act of ‘jumping through hoops’ set up by others. Self-assessment has conventionally been positioned as an act of assessment undertaken by the subject. There is a strong tradition in which it is taken to be analogous to other forms of assessment and thus is judged as any other assessment measure in terms of its validity and reliability, which are always taken in relation to some kind of independent measure, commonly in relation to teachers’ assessments. This is intrinsically a major source for inauthenticity – which we argue is not always ‘wrong’ but certainly something that needs to be questioned by educators. Seeing self-assessment as an act of measurement rather than as an authentic practice of evaluative judgement leads to the valorisation of accuracy, judged against an expert source, whose own reliability, validity and accuracy is taken as given, even when we know this is far from being true. It may be unsurprising that in such situations, students provide ‘zombie-like reflections’ rather than honest and accurate judgements of their own work (see De la Croix and Veen Citation2018).

Limitations

Various limitations of our study should be noted. First, we only used a database search to identify sources for our review. For example, backwards and forward snowballing processes may have enabled us to find more relevant sources. Second, the search terms were used for titles, abstracts and keywords, which means that some relevant sources may have been unidentified if they discussed the topic of authenticity in the main body of their text or if they used different terminology beyond ‘authenticity’ and ‘realism’ to discuss these ideas. Third, we only focused on studies published in English, meaning that our review has been unable to synthesise knowledge from non-English speaking communities of practice.

Conclusion

Our integrative review has gathered evidence from various communities of practice to understand authenticity in the specific context of student self-assessment. We have reframed self-assessment – commonly understood as a universal, instrumental assessment practice – as a socially embedded pedagogical practice by placing authenticity at its very heart. Our study has emphasised that to be ‘authentic’, self-assessment must consider the dimensions of present and future work, authentic self, knowledge and the digital world. Moreover, we have discussed that students also must perceive self-assessment as authentic, which is often not the case with current practices. Finally, we urge future research to continue from this initial conceptualisation to further unpack authenticity in self-assessment. While we have proposed five dimensions for authenticity, our purpose is not to dominate the conversation but to stimulate it. We argue, in parallel with Ajjawi et al. (Citation2023), that assessment and pedagogical design ‘can only encapsulate specific, pre-determined potentialities for authenticity’ (7). We hope that critical conversations about the authenticity of self-assessment may help to reposition self-assessment not as a marginal check-in practice but as an integral part of higher education.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- The references in our review are marked with an asterisk (*).

- Ajjawi, R., J. Tai, M. Dollinger, P. Dawson, D. Boud, and M. Bearman. 2023. From authentic assessment to authenticity in assessment: Broadening perspectives. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 499–510. doi:10.1080/02602938.2023.2271193.

- *Ali, G., and N. Lalani. 2020. Approaching spiritual and existential care needs in health education: Applying SOPHIE (self-exploration through ontological, phenomenological, and humanistic, ideological, and existential expressions), as practice methodology. Religions 11, no. 9: 451. doi:10.3390/rel11090451.

- Alsina, Á, S. Ayllón, J. Colomer, R. Fernandez-Peña, J. Fullana, M. Pallisera, and L. Serra. 2017. Improving and evaluating reflective narratives: A rubric for higher education students. Teaching and Teacher Education 63: 148–58. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2016.12.015.

- Ashford-Rowe, K., J. Herrington, and C. Brown. 2014. Establishing the critical elements that determine authentic assessment. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 39, no. 2: 205–22. doi:10.1080/02602938.2013.819566.

- *Belluigi, D. 2020. It’s just such a strange tension’: Discourses of authenticity in the creative arts in higher education. International Journal of Education & The Arts 21, no. 5, doi:10.26209/ijea21n5.

- Blanch-Hartigan, D. 2011. Medical students’ self-assessment of performance: Results from three meta-analyses. Patient Education and Counseling 84, no. 1: 3–9. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2010.06.037.

- Boud, D. 1999. Avoiding the traps: Seeking good practice in the use of self assessment and reflection in professional courses. Social Work Education 18, no. 2: 121–32. doi:10.1080/02615479911220131.

- Boud, D., and R. Soler. 2016. Sustainable assessment revisited. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 41, no. 3: 400–13. doi:10.1080/02602938.2015.1018133.

- Boud, D., and D. Walker. 1998. Promoting reflection in professional courses: The challenge of context. Studies in Higher Education 23, no. 2: 191–206. doi:10.1080/03075079812331380384.

- Bourke, R. 2018. Self-assessment to incite learning in higher education: Developing ontological awareness. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 43, no. 5: 827–39. doi:10.1080/02602938.2017.1411881.

- *Bradley, R., and S. Schofield. 2014. The undergraduate medical radiation science students’ perception of using the E-portfolio in their clinical practicum. Journal of Medical Imaging and Radiation Sciences 45, no. 3: 230–43. doi:10.1016/j.jmir.2014.04.004.

- Brown, G.T., H.L. Andrade, and F. Chen. 2015. Accuracy in student self-assessment: Directions and cautions for research. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice 22, no. 4: 444–57. doi:10.1080/0969594X.2014.996523.

- Brown, G., and L.R. Harris. 2014. The future of self-assessment in classroom practice: Reframing self- assessment as a core competency. Frontline Learning Research 2, no. 1: 22–30. doi:10.14786/flr.v2i1.24.

- *Burton, K. 2016. Using a reflective court report to integrate and assess reflective practice in Law. Journal of Learning Design 9, no. 2: 56–67. doi:10.5204/jld.v9i2.217.

- *Bußenius, L., and S. Harendza. 2023. Development of an instrument for medical students’ self-assessment of facets of competence for patient-centred care. Patient Education and Counseling 115: 107926. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2023.107926.

- *Cooke, M., and B. Matarasso. 2005. Promoting reflection in mental health nursing practice: A case illustration using problem-based learning. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing 14, no. 4: 243–8. doi:10.1111/j.1440-0979.2005.00388.x.

- Cronin, M.A., and E. George. 2023. The why and how of the integrative review. Organizational Research Methods 26, no. 1: 168–92. doi:10.1177/1094428120935507.

- De la Croix, A., and M. Veen. 2018. The reflective zombie: Problematizing the conceptual framework of reflection in medical education. Perspectives on Medical Education 7: 394–400. doi:10.1007/S40037-018-0479-9.

- *Droege, M. 2003. The role of reflective practice in pharmacy. Education for Health: Change in Learning & Practice 16, no. 1: 68–74.

- *Espinoza, A.Q., and S.L. Medina. 2021. Understanding in-service teachers’ learning experience while developing an electronic portfolio. Teaching English with Technology 21, no. 4: 19–34.

- Falchikov, N., and D. Boud. 1989. Student self-assessment in higher education: A meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research 59, no. 4: 395–430. doi:10.3102/00346543059004395.

- *Fergusson, L., L. van der Laan, S. Imran, and P.A. Danaher. 2022. Authentic assessment and work-based learning: The case of professional studies in a post-COVID Australia. Higher Education, Skills and Work-Based Learning 12, no. 6: 1189–210. doi:10.1108/HESWBL-03-2022-0074.

- *Ford, N.J., L.M. Gomes, and S.B. Brown. 2023. Brave spaces in nursing ethics education: Courage through pedagogy. Nursing Ethics 31, doi:10.1177/09697330231183075.

- *Gibbons, J. 2018. Exploring conceptual legal knowledge building in law students’ reflective reports using theoretical constructs from the sociology of education: What, how and why? The Law Teacher 52, no. 1: 38–52. doi:10.1080/03069400.2016.1273458.

- Giddens, A. 1990. The consequences of modernity. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Gulikers, J.T., T.J. Bastiaens, P.A. Kirschner, and L. Kester. 2008. Authenticity is in the eye of the beholder: Student and teacher perceptions of assessment authenticity. Journal of Vocational Education & Training 60, no. 4: 401–12. doi:10.1080/13636820802591830.

- *Hargreaves, J. 1997. Using patients: Exploring the ethical dimension of reflective practice in nurse education. Journal of Advanced Nursing 25, no. 2: 223–8. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2648.1997.1997025223.x.

- Harris, L.R., G.T. Brown, and J. Dargusch. 2018. Not playing the game: Student assessment resistance as a form of agency. The Australian Educational Researcher 45, no. 1: 125–40. doi:10.1007/s13384-018-0264-0.

- *Julie, H., P. Daniels, and T.A. Adonis. 2005. Service-learning in nursing: Integrating student learning and community-based service experience through reflective practice. Health SA Gesondheid 10, no. 4: 41–54.

- Kasanen, K., and H. Räty. 2002. “You be sure now to be honest in your assessment”: Teaching and learning self-assessment. Social Psychology of Education 5, no. 4: 313–328. doi:10.1023/A:1020993427849.

- *Kearney, S. 2019. Transforming the first-year experience through self and peer assessment. Journal of University Teaching and Learning Practice 16, no. 5: 20. doi:10.53761/1.16.5.3.

- *Kearney, S.P., and T. Perkins. 2014. Engaging students through assessment: The success and limitations of the ASPAL (authentic self and peer assessment for learning) model. Journal of University Teaching and Learning Practice 11, no. 3: 4. doi:10.53761/1.11.3.2.

- *Kearney, S., T. Perkins, and S. Kennedy-Clark. 2016. Using self- and peer-assessments for summative purposes: Analysing the relative validity of the AASL (authentic assessment for sustainable learning) model. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 41, no. 6: 840–53. doi:10.1080/02602938.2015.1039484.

- *Kennedy, H., and J. Kennedy. 2022. “It’s real, it’s much more real”: An exploration of values-based reflective practice© as a reflective tool. Health and Social Care Chaplaincy 10, no. 1, doi:10.1558/hscc.42191.

- *Keogh, C., and K.A. Corrales. 2023. Using reflection to demonstrate development of active citizenship and critical consciousness through authentic and locally based projects. Reflective Practice, 591–603. doi:10.1080/14623943.2023.2211534.

- *Kiersch, C., and N. Gullekson. 2021. Developing character-based leadership through guided self-reflection. The International Journal of Management Education 19, no. 3: 100573. doi:10.1016/j.ijme.2021.100573.

- *Kim, L., B.C. Hernandez, A. Lavery, and T.K. Denmark. 2016. Stimulating reflective practice using collaborative reflective training in breaking bad news simulations. Families, Systems, & Health 34, no. 2: 83–91. doi:10.1037/fsh0000195.

- *Lalor, J., F. Lorenzi, and R. Justin. 2015. Developing professional competence through assessment: Constructivist and reflective practice in teacher-training. Eurasian Journal of Educational Research 15: 45–66. doi:10.14689/ejer.2015.58.6.

- *Leijenaar, E., C. Eijkelboom, and M. Milota. 2023. “An invitation to think differently”: A narrative medicine intervention using books and films to stimulate medical students’ reflection and patient-centeredness. BMC Medical Education 23, no. 1: 568. doi:10.1186/s12909-023-04492-x.

- Lew, M.D., W.A.M. Alwis, and H.G. Schmidt. 2010. Accuracy of students’ self-assessment and their beliefs about its utility. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 35, no. 2: 135–56. doi:10.1080/02602930802687737.

- *Lewis, D., T. Virden, P.S. Hutchings, and R. Bhargava. 2011. Competence assessment integrating reflective practice in a professional psychology program. Journal of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning 11, no. 3: 86–106.

- Macfarlane, B., and L. Gourlay. 2009. The reflection game: Enacting the penitent self. Teaching in Higher Education 14, no. 4: 455–9. doi:10.1080/13562510903050244.

- *Mann, K.V. 2010. Self-assessment: The complex process of determining “how we are doing” – a perspective from medical education. Academy of Management Learning & Education 9, no. 2: 305–13. doi:10.5465/amle.9.2.zqr305.

- Mann, K., C. van der Vleuten, K. Eva, H. Armson, B. Chesluk, T. Dornan, and J. Sargeant. 2011. Tensions in informed self-assessment: How the desire for feedback and reticence to collect and use it can conflict. Academic Medicine 86, no. 9: 1120–7. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e318226abdd.

- *Matshaka, L. 2021. Self-reflection: A tool to enhance student nurses’ authenticity in caring in a clinical setting in South Africa. International Journal of Africa Nursing Sciences 15: 100324. doi:10.1016/j.ijans.2021.100324.

- McArthur, J. 2023. Rethinking authentic assessment: work, well-being, and society.Higher Education 85, no. 1: 85–101. doi:10.1007/s10734-022-00822-y.

- *McGarr, O., and CÓ Gallchóir. 2020. The futile quest for honesty in reflective writing: Recognising self-criticism as a form of self-enhancement. Teaching in Higher Education 25, no. 7: 902–8. doi:10.1080/13562517.2020.1712354.

- Mehrabi Boshrabadi, A., and M.R. Hosseini. 2021. Designing collaborative problem solving assessment tasks in engineering: an evaluative judgement perspective. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 46, no. 6: 913–927. doi:10.1080/02602938.2020.1836122.

- *Naidu, T., and A.K. Kumagai. 2016. Troubling muddy waters. Academic Medicine 91, no. 3: 317–21. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000001019.

- *Newcomb, M., J. Burton, and N. Edwards. 2018. Pretending to be authentic: Challenges for students when reflective writing about their childhood for assessment. Reflective Practice 19, no. 3: 333–44. doi:10.1080/14623943.2018.1479684.

- Ng, S.L., E.A. Kinsella, F. Friesen, and B. Hodges. 2015. Reclaiming a theoretical orientation to reflection in medical education research: A critical narrative review. Medical Education 49, no. 5: 461–75. doi:10.1111/medu.12680.

- *Nguyen-Truong, C.K.Y., A. Davis, C. Spencer, M. Rasmor, and L. Dekker. 2018. Techniques to promote reflective practice and empowered learning. Journal of Nursing Education 57, no. 2: 115–20. doi:10.3928/01484834-20180123-10.

- *Nguyen, C.F. 2013. The ePortfolio as a living portal: A medium for student learning, identity, and assessment. International Journal of EPortfolio 3, no. 2: 135–48.

- Nieminen, J.H. 2021. Beyond empowerment: Student self-assessment as a form of resistance. British Journal of Sociology of Education 42, no. 8: 1246–64. doi:10.1080/01425692.2021.1993787.

- Nieminen, J.H., H. Asikainen, and J. Rämö. 2021. Promoting deep approach to learning and self-efficacy by changing the purpose of self-assessment: A comparison of summative and formative models. Studies in Higher Education 46, no. 7: 1296–311.

- Nieminen, J.H., M. Bearman, and R. Ajjawi. 2023. Designing the digital in authentic assessment: is it fit for purpose?. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 48, no. 4: 529–543. doi:10.1080/02602938.2022.2089627.

- Nieminen, J.H., and J. Lahdenperä. 2021. Assessment and epistemic (in)justice: How assessment produces knowledge and knowers. Teaching in Higher Education, 300–17. doi:10.1080/13562517.2021.1973413.

- Nieminen, J.H., and L. Tuohilampi. 2020. ‘Finally studying for myself’ – examining student agency in summative and formative self-assessment models. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 45, no. 7: 1031–45. doi:10.1080/02602938.2020.1720595.

- Nieminen, J.H., and L. Yang. 2023. Assessment as a matter of being and becoming: Theorising student formation in assessment. Studies in Higher Education, 1–14. doi:10.1080/03075079.2023.2257740.

- Nulty, D.D. 2011. Peer and self-assessment in the first year of university. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 36, no. 5: 493–507. doi:10.1080/02602930903540983.

- Panadero, E., G.T. Brown, and J.W. Strijbos. 2016. The future of student self-assessment: A review of known unknowns and potential directions. Educational Psychology Review 28: 803–30. doi:10.1007/s10648-015-9350-2.

- *Parikh, S.B., C. Janson, and T. Singleton. 2012. Video journaling as a method of reflective practice. Counselor Education and Supervision 51, no. 1: 33–49. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6978.2012.00003.x.

- Pitkänen, H. 2022. The politics of pupil self-evaluation: A case of Finnish assessment policy discourse. Journal of Curriculum Studies 54, no. 5: 712–32. doi:10.1080/00220272.2022.2040596.

- *Ross, J. 2011. Traces of self: Online reflective practices and performances in higher education. Teaching in Higher Education 16, no. 1: 113–26. doi:10.1080/13562517.2011.530753.

- *Ross, J. 2014. Engaging with “webness” in online reflective writing practices. Computers and Composition 34: 96–109. doi:10.1016/j.compcom.2014.09.007.

- *Salminen, H., N. Zary, K. Björklund, E. Toth-Pal, and C. Leanderson. 2014. Virtual patients in primary care: Developing a reusable model that fosters reflective practice and clinical reasoning. Journal of Medical Internet Research 16, no. 1: e2616. doi:10.2196/jmir.2616.

- Sokhanvar, Z., K. Salehi, and F. Sokhanvar. 2021. Advantages of authentic assessment for improving the learning experience and employability skills of higher education students: A systematic literature review.Studies in Educational Evaluation 70: 101030. doi:10.1016/j.stueduc.2021.101030.

- *Southcott, J., and R. Crawford. 2018. Building critically reflective practice in higher education students: Employing auto-ethnography and educational connoisseurship in assessment. Australian Journal of Teacher Education 43, no. 5: 95–109.

- *Stupans, I., G. March, and S.M. Owen. 2013. Enhancing learning in clinical placements: Reflective practice, self-assessment, rubrics and scaffolding. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 38, no. 5: 507–19. doi:10.1080/02602938.2012.658017.

- Tan, K.H. 2008. Qualitatively different ways of experiencing student self-assessment. Higher Education Research & Development 27, no. 1: 15–29. doi:10.1080/07294360701658708.

- Taras, M. 2010. Student self-assessment: Processes and consequences. Teaching in Higher Education 15, no. 2: 199–209. doi:10.1080/13562511003620027.

- Tilakaratna, N., and E. Szenes. 2024. Seeing knowledge and knowers in critical reflection: Legitimation code theory. In Demystifying critical reflection, edited by Namala Tilakaratna, and Eszter Szenes, 1–17. New York: Routledge.

- *Tremblay, M.L., J. Leppink, G. Leclerc, J.J. Rethans, and D.H. Dolmans. 2019. Simulation-based education for novices: Complex learning tasks promote reflective practice. Medical Education 53, no. 4: 380–9. doi:10.1111/medu.13748.

- *Tweed, M., G. Purdie, and T. Wilkinson. 2017. Low performing students have insightfulness when they reflect-in-action. Medical Education 51, no. 3: 316–23. doi:10.1111/medu.13206.

- Vu, T.T., and G. Dall’Alba. 2014. Authentic assessment for student learning: An ontological conceptualisation. Educational Philosophy and Theory 46, no. 7: 778–91. doi:10.1080/00131857.2013.795110.

- Whittemore, R., and K. Knafl. 2005. The integrative review: Updated methodology. Journal of Advanced Nursing 52, no. 5: 546–53. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03621.x.

- *Wingrove, D., and M. Turner. 2015. Where there is a WIL there is a way: Using a critical reflective approach to enhance work readiness. Asia-Pacific Journal of Cooperative Education 16, no. 3: 211–22.

- Yan, Z. 2022. Student self-assessment as a process for learning. New York: Taylor & Francis.

- Yan, Z., and D. Carless. 2022. Self-assessment is about more than self: The enabling role of feedback literacy. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 47, no. 7: 1116–28. doi:10.1080/02602938.2021.2001431.

- Yan, Z., H. Lao, E. Panadero, B. Fernández-Castilla, L. Yang, and M. Yang. 2022. Effects of self-assessment and peer-assessment interventions on academic performance: A meta-analysis. Educational Research Review 37, doi:10.1016/j.edurev.2022.100484.

- Yan, Z., E. Panadero, X. Wang, and Y. Zhan. 2023a. A systematic review on students’ perceptions of self-assessment: Usefulness and factors influencing implementation. Educational Psychology Review 35, no. 3: 81. doi:10.1007/s10648-023-09799-1.

- Yan, Z., X. Wang, D. Boud, and H. Lao. 2023b. The effect of self-assessment on academic performance and the role of explicitness: A meta-analysis. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 48, no. 1: 1–15. doi:10.1080/02602938.2021.2012644.

- *Yeo, N., and J. Rowley. 2020. ‘Putting on a show’ non-placement WIL in the performing arts: Documenting professional rehearsal and performance using eportfolio reflections. Journal of University Teaching and Learning Practice 17, no. 4, doi:10.53761/1.17.4.5.