ABSTRACT

The UK’s 2016 EU referendum and its aftermath have seen the eruption back into mainstream political and media discourse of spatial language and representations. As commentators, politicians and citizens have sought to make sense of the splintering and convulsion occasioned by the referendum, a spatial imaginary and lexicon has emerged – for example, referencing ‘left behind places’ populated by ‘left behind’ citizens, and contrasting these with ‘metropolitan cores’ and ‘metropolitan elites’. Informed by this the present paper identifies and unpacks some of the spatial imaginaries foregrounded in the UK’s ‘European debate’ and the aftermath of the 2016 EU referendum.

‘Qu’est-ce qu’une idéologie sans un espace auquel elle se réfère, qu’elle décrit, dont elle utilise le vocabulaire et les connexions, dont elle contient le code?’

‘Today, we stand on the verge of an unprecedented ability to liberate global trade for the benefit of our whole planet with technological advances dissolving away the barriers of time and distance… It is potentially the beginning of what I might call ‘post geography trading world’ where we are much less restricted in having to find partners who are physically close to us’.

Introduction

A striking feature of the UK’s 2016 EU referendum and its aftermath is the eruption back into mainstream political and media discourse of spatial language and representations. As commentators, politicians and citizens have sought to make sense of the national splintering and convulsion unleashed by the referendum, a potent spatial imaginary and lexicon has emerged – epitomized, for example, by references to ‘left behind’ places and ‘metropolitan cores’. The referendum also had disruptive scalar effects, with a forceful reassertion of the nation state and imaginary as the primary legitimate scale of representation and belonging, often in combination with nativist and exclusionary (re)interpretations of citizenship (Bachmann & Sidaway, Citation2016). Conceptions of geography have also been prominent in situating the process within a wider global context, notably within debates surrounding the economic consequences of remaining in, or leaving the EU. Some ‘hyperglobalist’ supporters of the UK’s so-called ‘Brexit’ from the EU have thus advanced arguments that the importance of physical proximity and distance is being eroded and that we stand on the threshold of a ‘post geography trading world’ (Fox, Citation2016). Such imaginings are often powerfully affective. As Siles-Brügge (Citation2018, p. 3, 1) notes, for some advocates of ‘hard’ Brexit notions of ‘Global Britain’ are wrapped up with an ‘emotive spatial imaginary’ of ‘bringing the UK, and its (in this imaginary) overly regulated economy, closer to its “kith and kin” in the Anglosphere’.

Against the context outlined above, this paper seeks to reflect on some of the spatial imaginaries which have been associated with the UK’s ‘European debate’Footnote1 and the 2016 EU referendum and its aftermath. Its central contention is that an appreciation of: different geographical interpretations and representations; the ‘performative’ agency they have attained; and, their relationships with material spaces, places and practices, is crucial in seeking to understand the causalities and consequences of these intertwined historical processes.

Spatial imaginaries

There is a growing body of work on spatial imaginaries, which are defined by Davoudi (Citation2018, p. 101) as: ‘deeply held, collective understandings of socio-spatial relations that are performed by, give sense to, make possible and change collective socio-spatial practices. They are produced through political struggles over the conceptions, perceptions and lived experiences of place. They are circulated and propagated through images, stories, texts, data, algorithms and performances. They are infused by relations of power in which contestation and resistance are ever-present’.

Yet despite its popularity in writing within geography and other disciplines, systematic reviews of the field and the different interpretations and uses of the term are arguably rather rare. For Watkins (Citation2015, p. 508, 512) ‘spatial imaginaries’ has become an ‘umbrella term’ that potentially obscures the fact that there are at least ‘three different types of spatial imaginaries’: (1) Places such as the Orient, Detroit, or Russia; (2) Idealized spaces such as the ghetto, developed country, or global city; and (3) Spatial transformations such as globalization, gentrification, or deindustrialization (Watkins, Citation2015, p. 508, 512). He observes too that spatial imaginaries have been documented at numerous ‘scales’, or ‘conceptions of spatial orderings’ ().

Table 1. Scales of spatial imaginary (adapted from Watkins, Citation2015, p. 511).

In addition to addressing definitional issues, work on spatial imaginaries has also increasingly sought to explore the performative as well as ‘simply’ representational properties of imaginaries, and to explore their relationships with material spaces, places and practices.

The attention to performativity is a response to the fact that existing works ‘predominantly describe spatial imaginaries as representational discourses about places and spaces’ (Citation2015, p. 508), and there are only a few treatments which define imaginaries as performative. Davoudi argues that this latter dimension deserves more attention because imaginaries ‘Constructed and circulated through images, discourses and practices, … generate far reaching claims on our social and political lives’ (Citation2018, p. 97). The appreciation of spatial imaginaries as vehicles through which power is rationalized and mobilized is neatly captured by Crawford’s (Citation2018) notion of their ‘conscription’ to different power agendas. This chimes well with the emphasis placed on the ideological and mobilizing properties of socially-constructed representations of space and territory, for example, in French geographical tradition (Lefebvre, Citation1974; Santamaria & Elissalde, Citation2018).

Consideration of the performativity of spatial imaginaries may open avenues to ‘more direct analysis of material practices, and considerations of how material practices directly form and modify spatial imaginaries’ (Watkins, Citation2015, p. 519). Echoing this Davoudi (Citation2018, p. 97) calls for more attention to be paid to the ‘role of space and place in the construction of social imaginaries’.

It will be argued below that such current themes of analysis around the performativity of spatial imaginaries and their articulation with, and through, material spaces, places, and practices, offer opportunities to develop our interpretations of the role of imagined and material space in the UK’s European debate.

Finally, though much work on imaginaries adopts a discursive mode of analysis there have been some useful contributions in recent years which provide tools to structure a more systematic form of evaluation. For example, drawing on the work of Healey (Citation2007), Crawford (Citation2017, p. 20) proposes a set of questions to be used as a framework in analysing spatial imaginaries (Box 1).

1. How is the spatial imaginary bounded and what are its scales?

2. What are the key descriptive concepts, categories and measures?

3. How is the spatial imaginary positioned in relation to other spatial entities? What are its connectivities and how are these produced?

4. Who or what is ‘in focus’? Who is present? How are non-present issues and people brought ‘to the front’? Who/what is ‘in shadow’

or in ‘back regions’?

5. How is the connection between past, present and future established?

6. Whose viewpoint and whose perceived and lived space is being privileged?

Identifying spatial imaginaries of the UK’s ‘European debate’

The rest of this paper reflects on what a spatial imaginaries perspective might bring to interpretations of the UK’s relationship with Europe, and in particular the 2016 EU referendum campaign and its aftermath. In order to do this we have tentatively identified some key imaginaries. This is an inevitably subjective and selective task and we do not claim to offer a comprehensive treatment. Some of the labels used to described imaginaries may be recognizable from public discourse on the EU referendum and its aftermath – for example, that of ‘Left Behind Britain’. In other cases we have created labels which seek to capture the essence of the socio-spatial relations represented and performed through certain imaginaries.

Where relevant, the discussion refers to the definitional and analytical themes outlined in the previous section regarding the scale (), ‘type’, performativity and materiality of imaginaries. The paper’s development was also informed by some of the recently proposed approaches to conducting more systematic analysis of imaginaries (Box 1), but attempting to present all the imaginaries below using such frameworks became unwieldly due to space constraints and they are instead presented more discursively. Similarly, there is not the space to fully rehearse the wider debates on the 2016 EU referendum campaign and its aftermath, but where appropriate, references are made to themes within this – for example, those pertaining to Empire, nationalism and uneven development, and social fragmentation along relational-territorial divides, identified by Bachmann and Sidaway (Citation2016) and others (Jessop, Citation2018; Rosamond, Citation2018).

Some imaginaries of the UK’s ‘European debate’ and 2016 EU referendum campaign

British Eurosceptics, in the years before and during the 2016 UK EU referendum (‘the referendum’), are generally seen as having been very successful in articulating and dominating the linguistic parameters and terms of the debate on the UK’s place in Europe (Goodwin, Citation2017). The very ‘naming and framing’ of the whole notion of the UK leaving the EU as a ‘Brexit’ (‘British Exit’), meant that even those of a more pro-European sensibility have found that they have to discuss the European issue in the ‘dream language’ of the sceptics. During the 2016 referendum the Leave CampaignFootnote2 was able to build on this base and deploy powerful slogans like ‘Take Back Control’. The contention below is that the Eurosceptics not only managed to dominate the referendum campaign linguistically, but also succeeded in articulating and ‘conscripting’ (Crawford, Citation2018) to their cause (through text and image) the most striking spatial imaginaries.

A Sceptred Isle (under siege)

Contemporary geopolitical issues such as the migrant crisis in mainland Europe may well have weighed heavily in the campaign, allowing the development of imaginings of risk and fear by elements of the leave side. However, the leave narrative was also able draw on longer term and deeply rooted spatial imaginaries which emphasized Britain’s insular and exceptional nature in comparison to a continental ‘other’. This echoed themes explored by Young (Citation1998, Citation2016) around Britain’s relationship with ‘Europe’ in general and the ‘European project’ in particular. Adopting the language of Shakespeare (King Richard II, Act 2, Scene 1), Young argued that ‘The mythology of the scepter’d isle, the demi-paradise, bit deep into the consciousness of many who addressed the [European] question’ and that ‘The sacredness of England, whether or not corrupted into Britain, became a quality setting it, in some minds, for ever apart from Europe’ (Young, Citation2016). It seems almost banal to note that the ‘Scepter’d Isle’ could be classed as an imaginary of Idealized space to use Watkins’s (Citation2015) terms. But it wasn’t just the insular physical space that was special, ‘The island people were not only different but, mercifully, separate, housed behind their moat. They were also inestimably superior, as was shown by history both ancient and modern’ (Young, Citation2016). The language used, for example in the pages of certain Eurosceptic newspapers, and the rhetoric of some leading ‘Brexiters’ over many years – and reaching a crescendo during the 2016 campaign, echoed such sentiments (e.g. ‘Britain is not like other countries’ as the leave supporter, British Conservative MP, David Davis wrote in Citation2016).

The imaginary of insular exceptionalism found its foil in the invocation of a potent ‘imagery of place’ (Watkins, Citation2015), which represented ‘Brussels’ as a shorthand for the EU project and its various elements (notably the European Commission) and its alleged failings. This imaginary of ‘Brussels’, however, did not reference/represent the material place, or its 1.2 million people, the Grote Markt/Grand-Place, or Manneken Pis Statue etc. Rather it was conscripted to capture ‘all that was wrong’ with the EU, and project an image of a remote and ‘grey’ administrative place of foreign political duplicity, anti-British foment, bloated bureaucracy and corruption. As Bachmann and Sidaway (Citation2016, p. 49) note, certain British politicians succeeded in ‘convincing a sufficient number of voters’ that austerity and decline were a product of ‘external factors – first and foremost “external rule” from Brussels’. For many voters therefore, though the EU may not always ‘have a face’ (with many being unfamiliar with, for example, their MEPs, or key EU figures), in the invocation of the imaginary of ‘Brussels’ it was always identified with an ‘other/ed’ place.

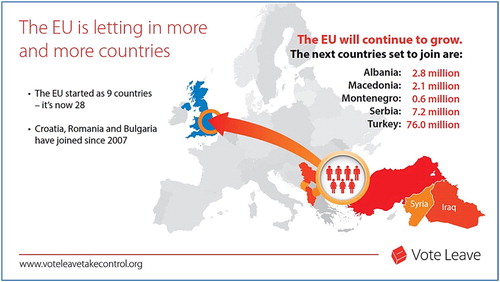

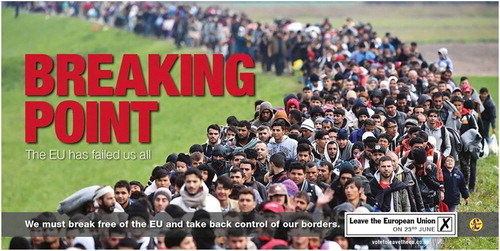

The longstanding themes of independence, and insular exceptionalism outlined above and contemporary geopolitical events – notably the migrant and financial and economic crises of the 2000s and the 2010s, fed into a new imaginary during the 2016 referendum campaign. Though quickly branding the Remain campaign’s, largely economically focused warnings of the possible effects of leaving the EU, as ‘Project Fear’, the leave campaign mounted its own version of this in which spatial representations of ‘external threat’ played a significant role. In this the ‘Sceptred Isle’ was now under siege. This imaginary was supported by a lexicon of geographical mobility and flux with references to ‘open borders’, ‘migrants’, ‘influxes’, ‘flows’ and ‘swarms’ (Elgot, Citation2016), constructing an spatial imaginary of the openness of the UK to ‘others’ from ‘other places’, and notably ‘openess to’ (in an echo of Said’s, Citation1978 pioneering work on imaginaries and western stances towards the ‘Orient’) ‘to the East’. This narrative was powerfully supported by visual representations notably Vote Leave’s ‘Countries set to join the EU’, and ‘What the EU “tourist deal” means’ posters, and UKIP’s ‘Breaking Point’ poster (–). If Britain had been created a ‘demi paradise’ and ‘a fortress built by nature for herself’ against the ‘envy of less happier lands’ (King Richard II, Act 2, Scene 1), these natural advantages it was suggested were being eroded by continued entanglement in a supranational European structure.

Global Britain v. Little Europe

Yet if Britain’s ‘scepter’d’ isle’, the ‘precious stone set in the silver sea’ (Shakespeare, King Richard II, Act 2, Scene 1) was presented as being at the mercy of the machinations of ‘foreign’ powers and their ‘Brussels-based’ bureaucrats, and assieged by flows of migrants, some leave campaigners argued that this did not mean the ‘Brexit’ project was hostile to all external political, economic, social, and spatial relations. The narrative of ‘Global Britain’ promoted by leading leave supporters sought to ‘get behind’ the arguments of remain supporting internationalists, implying that it was they who were insular in still thinking of Europe when Britain’s destiny and potential were more properly global. The fact that certain other EU states were more significant global trading powers than the UK whilst being firmly within the bloc, did not prevent the ‘Global Britain’ imaginary from playing an important role in selling the ‘Brexit’ project, attenuating some of its shaper nationalist angles and making it more palatable to a wider ‘liberal/globalist’ constituency. As Isakjee and Lorne (Citationin press, p. 7) note ‘Contrary to the notion that the new politics is about closure as opposed to openness, those opposing EU membership were happy to extol the virtues of global connections and relationships’ though as they note this was to be ‘only on “British”; terms, and in “British” interests’.

The globalist wing of the leave project thus represented an imaginary of spatial transformation (Watkins, Citation2015), which stressed the virtues and ease of global free trade. This position was typically coupled with an ultraliberal view of society and regulation which was frequently contrasted with the ‘sclerotic’, ‘sinking ship’ of the EU, with its ‘outdated’ social market economy (Hannan, Citation2011), and a belief that advances in information and transport technologies made material space and friction less of a factor in trading relations (Fox, Citation2016). This global imaginary is encapsulated by the Facebook post of one fervent leave supporter, witnessed by the author, which claimed that ‘Geography doesn’t matter anymore in a globalised world’.

The EU as neoliberal ‘superspace’

An imaginary of hyper globalist opportunity and the prospect of supercharged liberal free trade outside the EU ‘Socialist Superstate’ (or sometimes ‘EUSSR’), thus fuelled the imagination of many political and financial interests that backed leaving the EU. But those of the so called ‘Lexit’ (Left Exit) tendency seemed conversely drawn to an imaginary of the EU as a peculiarly neoliberal space. This raised interesting dimensions in scalar terms, with the EU being at once embedded in a wider liberal world and constituted ‘from below’ by member states whose political classes and populations had largely also opted for liberal political programmes over a similar same period that the UK was in the EEC/EU. Though the UK is generally regarded as the EU’s most liberally inclined large member state, the hope was that leaving the EU would provide an opportunity for counteraction of the UK’s self-liberalising tendency. Often informed by readings of authors such as Piketty (Citation2016) and Varoufakis (Citation2016) (though not necessarily adopting the same position on the specific question of whether the UK should leave the EU), ‘Lexiters’ articulated emotive imaginaries of place, in particular emphasizing the conditions experienced by peripheral and southern EU states, following the financial crisis of 2008 and the austerity decade which followed. Within this there were further embedded more discrete imaginaries of place with images of, and references to, the sites of protests against austerity in the 2010s – places like Syntagma Square in Athens, or Puerta del Sol in Madrid. Such imaginings may not have engaged clearly with scalar contexts and paradoxes of leaving the EU, or address the fact that leaving would in all probability terminate the UK’s contribution as a wealthier member state to solidarity investments in less prosperous parts of Europe. Yet in performative terms, they may have contributed to some of those who might normally have been expected to oppose a project driven primarily by nationalist, ultraliberal, and hard right agendas, aligning themselves behind the leave position.

Imaginaries of remain – Europe as a ‘special area of human hope’?

If the various leave narratives seemed able to represent striking and clear spatial imaginaries and sub-imaginaries, then, we might ask, what were the spatial imaginaries conveyed by the Remain campaign? The latter sought to emphasize the virtues of trade with geographically proximate neighbouring countries, the UK’s economic, cultural, environmental ties with the rest of Europe, and the enhanced geopolitical and global influence that comes with membership of the EU. Yet it is arguable that a coherent sense of the ‘idea of Europe’ (Hoggart & Johnson, Citation1987) and an associated compelling spatial imaginary of ‘Europe’ proved elusive to the Remain campaign. To many citizens it perhaps appeared as an abstract notion and space, taking shape and relevance only at certain times (e.g. during a continental holiday; watching the news; ‘Eurovision’; or European sporting events), and not being the scale or space/place of the everyday. The communication of the idea of Europe was complexified by questions like ‘where does/will Europe/the EU end?’, or, observations like ‘Europe is not the EU’, or ‘We are leaving the EU, not Europe’.

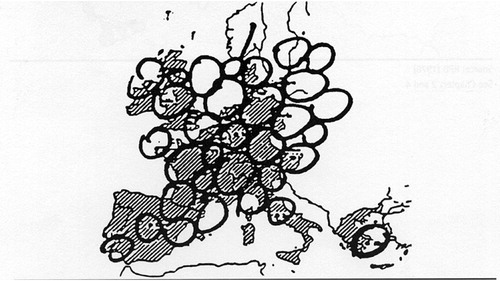

Committed pro-Europeans might well subscribe to the notion of Europe as a ‘special area of human hope’ which had figured in the Preamble to the abandoned Constitutional Treaty of the mid-2000s (Ferrara, Citation2007). This tied the space that is the EU to a system of values bound up in the work of the Council of Europe from the 1940s onwards, or the acquis communitaire of the EEC/EU developed since the 1950s. Within this, the idea of the ‘European model of society’ (Faludi, Citation2007; Nadin & Stead, Citation2008) with its attachment to ‘inclusive’, ‘sustainable’, and ‘smart’ development (European Commission, Citation2010, Citation2017) figured prominently; with this social imaginary often being contrasted with other models – notably that of north American capitalism. In spatial terms this model translates into the aspiration of greater territorial cohesion in the EU, inscribed into the Lisbon Treaty of 2007, and seen as promoting notions of a more balanced (i.e. less uneven) development of the EU (as captured by Kunzmann and Wegener’s imaginary of the ‘Bunch of Grapes’ – ); a more competitive EU; more coherent alignment of EU policies and programmes in territorial terms; and, a cleaner and greener Europe (Abrahams, Citation2013; Waterhout, Citation2007). Yet despite the UK’s role in establishing, and experience of, European regional policy (Sykes & Schulze-Bäing, Citation2017), Hague (Citation2016) – writing in the aftermath of the EU referendum, commented – ‘I doubt that the phrase “territorial cohesion” was ever uttered in the thousands of speeches and pamphlets’ during the EU referendum.

Figure 4. The ‘bunch of grapes’ – a vision of more balanced development in Europe. Source: Kunzmann and Wegener (Citation1991).

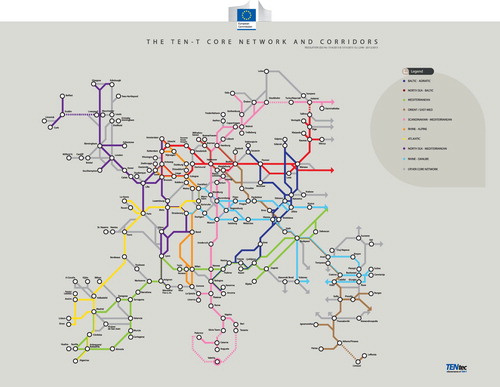

Perhaps the Remain campaign could have invoked stronger and more striking, or ‘affectively’ appealing, spatial imaginaries of ‘Europe’? For example, the images of the evolving TEN-T network () with its ambition of ‘connecting Europe’ (European Commission, Citation2018) and ‘making European space’ (a goal critiqued by some observers for promoting notions of frictionless mobility with potentially deleterious environmental impacts, Jensen & Richardson, Citation2004). Yet even when the remain messaging sought to emphasize the benefits of belonging to a wider European space it could sound negative – for example, in citing the disruptive impacts of any exit from the EU, with the potential need for people and goods to wait at less permeable borders.

Figure 5. Trans-European network map. Source: http://ec.europa.eu/transport/infrastructure/tentec/tentec-portal/site/maps_upload/metro_map2013.pdf.

There may also have been some circumspection at projecting an optimistic spatial imaginary of a Europe of freer flows and of spatial elements such as new cross border regions, for fear this might backfire in the face of an opposing campaign making much of the allegedly damaging effects of ‘open borders’ and flows of ‘others from other places’. There had been specific episodes in the past when EU initiatives such as the territorial cooperation funding programme ‘INTERREG’ had been presented by the Eurosceptic press – and indeed even government ministers as being plotted by foreign politicians and bureaucrats to undermine the territorial integrity of the UK (Owen, Citation2011; Shipman, Citation2006). And what of EU funding to support infrastructure plans? Was this not technocratic meddling from precisely the experts it was said people had had enough of (Jackson & Ormerod, Citation2017)? In such circumstances it was perhaps understandable that the Remain campaign was wary of actively seeking to invoke a positive affective and relational imaginary of Europe.

Absent imaginaries and scales?

As well as imaginaries at European, national and global levels, other scales were invoked by the campaigns. Even the domestic scale of home was addressed by claims from both sides that households would be more or less financially well-off under remain or leave scenarios. But overall the referendum campaign was a deliberation on how the space that is the UK should in future be linked and more, or less, integrated with a wider European space and this tended to emphasize and reify the UK ‘national’ scale. As a result other scales of imaginary such as those of the sub-state nation, subnational region, or city () were arguably less represented.

Perhaps unsurprisingly the leave campaign revelled in the scalar ‘nationalism’ of the campaign focussing on the ‘national’ UK scale and ‘imagined community’ (Anderson, Citation1991) and its relationships with the EU and wider world. Though certain cherished leave issues such as immigration were nevertheless communicated through sub-state, or local, imaginaries in accounts that homed in on particular places (e.g. Boston, Lincolnshire), or considered certain issues (such as the ‘housing crisis’).

There was, however, one imaginary and geopolitical framing which had previously been a staple of the political rhetoric of the neoliberal, and notably ‘Atlanticist’, forebears of the ‘Brexiters’ of 2016, but which was notable by its absence from the Leave campaign. For a variety of reasons, some historical, and others which have perhaps become more obvious since the vote (Cadwalladr & Jukes, Citation2018; Kerbaj, Wheeler, Shipman, & Harper, Citation2018; Wintour, Citation2018), the ‘traditional’, ‘othering’ and imaginary of ‘threat from the East’ was reoriented away from the northern sphere – with the Cold War era emphasis on the ‘Eastern bloc’ (and its arresting imaginary of the ‘Iron Curtain’), USSR/‘Russia’, towards a more south eastern sphere and the ‘fearing’ of refugees, migrants and ‘cultural others’ from this region (–).

The Remain campaign for its part certainly made general economic arguments about the possible impacts of leaving at the aggregate UK (or sometimes industry sector) level, but also referenced benefits that EU membership had brought to particular regions, cities, or natural spaces (e.g. EU regional cohesion funding support, or environmental protection), or specific investments (e.g. certain university, or cultural/leisure facilities). The particular impacts and risks to such progress and to industrial sectors in certain regions (e.g. the automotive industry) were also emphasized. Goodwin (Citation2017, p. 16) thus argues that typically ‘Remain focused on the internal risk of Brexit whereas Leavers were thinking far more about external threats’.

Also less prominent overall, though significant in their respective territories, were the sub-state interests and imaginaries of the UK’s Celtic nations. Here the European issue melded with issues of devolution, autonomous government, or independence, and the competing UK ‘national’ imaginary. In such territories the view that collaborative governance and subsidiarity should apply across the scales of multi-level governance from the EU to the subnational scales was held by many, who feared that ‘Brexit’ could be a cloak allowing a ‘power grab’ recentralisation of the British polity, or exacerbate old geopolitical issues and tensions. Yet the ‘Scottish’ question (assumed by some to have been settled for a generation by the 2014 referendum on Scottish independence) and the complexities which would arise at the Ireland – UK border on the island of Ireland if the UK left the EU, did not gain much traction in the UK-wide debate, seriously challenge the more dominant imaginaries detailed above, or appear to be issues that unduly troubled those advocating the leave option.

Imaginaries of an aftermath

Manley, Jones, and Johnston (Citation2017, p. 183) note how ‘Most of the analysis before the 2016 referendum’ was ‘based on opinion polling which focused on which groups were more likely to support each of the two options, with less attention to the geography of that support’. In contrast since the referendum this situation has arguably been reversed with the territorial explicans becoming the dominant account of the result. Indeed one of the most striking features of the post referendum period is how prominent geographical analyses and spatial imaginaries have been within commentaries on the outcome of the vote and debates about the likely distribution of the impacts of leaving the EU.

Left Behind Britain (‘Brexitland 1’)

The dominant spatial imaginary of ‘Brexit’ has become that of the revolt of ‘Left Behind Britain’. Here the vote to leave the EU is presented as an outcome, or almost the ‘wages’, of the uneven geographical changes produced from the economic structuring and ‘Anglo-liberal’ growth model’ (Hay, Citation2011; Rosamond, Citation2018) since the latter decades of the twentieth century, in which ‘towns and cities suffered from the loss of manufacturing jobs’ whereas ‘well-paid service sector jobs have largely been concentrated in London, the South East and financial centres in larger British cities’ (Isakjee & Lorne, Citationin press). The result of the referendum is thus presented as a cri de coeur expressing discontent with the territorially uneven outcomes of processes of ‘globalisation’ and related/nested processes such as European integration. This argument sees the pattern of the pro-leave vote reflecting the geographical concentration of such sentiment, and produces an imaginary of a ‘Left Behind Britain’ contrasted with the main metropolitan centres – in particular London, and the prosperous shires of lowland England. This overarching imaginary of ‘Left Behind Britain’ is also punctuated with discrete strong imaginaries of place (Watkins, Citation2015), which have cast places like Sunderland and Stoke on Trent (Domokos, Citation2018), as the emblematic sites of a ‘revolt’ against the ‘establishment’ and globalization; sometimes rendered as ‘Brexitland’ in media and social media accounts.

The leave lobby and the proto-Brexit state, quickly sought to conscript the imaginary of ‘Left Behind Britain’; apparently adopting its cause in a struggle against globalization and Europeanisation. Theresa May’s speech at the 2016 Conservative Party conference, thus argued that:

… today, too many people in positions of power behave as though they have more in common with international elites than with the people down the road, the people they employ, the people they pass in the street.

But if you believe you’re a citizen of the world, you’re a citizen of nowhere. You don’t understand what the very word ‘citizenship’ means. Theresa May (2016) (added emphases)

‘Remainia’

The tensions and unhealed divisions of the referendum campaign have also surfaced in evolving language and imaginaries. The spatial imaginaries of the result outlined above, have become overlaid with terms used to characterise/caricature the residents of the different islands of ‘Brexit Britain’. The phrase ‘liberal metropolitan elite’ has been commonly used to describe those living in the remain voting core cities and prosperous areas and towns of lowland England. They have also been more pointedly stereotyped by sections of the press, politicians and some commentators as ‘remoaners’, ‘snowflakes’, ‘traitors’ and ‘saboteurs’. Here we have labelled this imaginary of the remain voting areas ‘Remainia’. In some interpretations this imaginary has developed into a view that only London, Scotland and Northern Ireland voted to remain. This is well illustrated by a rather reductionist graphic from CNN () which simply shows the overall result in each region of England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland aggregated using a ‘first past the post in each in region’ logic. This both misses the point that the referendum was in fact a UK wide poll and the granularity of the voting patterns at lower spatial scales.

Figure 6. An imaginary of ‘Brexitland’ and ‘Remainia’. Source: CNN 2016 https://edition.cnn.com/2016/06/24/europe/eu-referendum-britain-divided/index.html.

This Sceptic Isle? (‘Brexitland 2’?)

In response to cariactures developed of remain voters and areas by the leave supporting press and politicians, the denizens and pundits of Remainia have gradually evolved their own characterizations and imaginaries of ‘Brexit’ places and people. A cover from an edition of the New European newspaper founded in the weeks following the referendum () illustrates this well. This mimicked a well-known railway poster of the 1930s–1950s for the seaside resort of Skegness in Lincolnshire, seen as characteristic of the ‘left behind coastal communities’ (Goodwin, Citation2017, p. 15) which had voted to leave the EU. In it the cheerful original ‘Skegness is SO Bracing’ poster was instead rather grimacingly rendered as ‘Skegness is SO Brexit’.

Figure 7. Skegness from ‘Bracing’ to ‘Brexit’. Sources: Left: Hassall, J. (1868 – died 1948) (artist) for London and North Eastern Railway (issuer); Right: The New European/cartoon by Martin Rowson. https://www.theneweuropean.co.uk/top-stories/this-is-why-skegness-is-the-seaside-town-brexit-could-close-down-1-4977081.

In the face of phenomena such as the documented rise in hate crime (Devine, Citation2018) and xenophobia during and after the EU referendum, and the rise of pejorative language to describe those who did not subscribe to the ‘Brexit project’, Britain in such imaginaries had perhaps become not so much the ‘Sceptred Isle’ as a ‘Sceptic Isle’ – hostile to foreigners, the educated, the liberally minded, and even its own younger generations.

‘Comfortable Britain’ (‘Blimp and Boomer Land’?)

The dominant antithetical imaginaries of ‘Left Behind Britain/Brexitland’ and ‘Liberal Metropolitan/Remainia’, however, tended to ‘shorthand’ the geographical complexity of the vote and its consequences. Crucially, whilst it is true that in many less prosperous areas a majority of those who actually voted opted to leave, as Dorling notes:

Contrary to popular belief, 52% of people who voted Leave in the EU referendum lived in the southern half of England, and 59% were in the middle classes, while the proportion of Leave voters in the lowest two social classes was just 24% (Dorling, Citation2016).

For Isakjee and Lorne it is thus clear that ‘that a solely economic analysis of Brexit is insufficient in either explaining the vote or in the interpretation of disillusionment or what it means to feel “left behind”’ (Citationin press, p. 3). There are those too who argue that much analysis of the results has overemphasized geographical versus value-based explanations of why certain individuals may have voted to leave the EU (Kaufmann, Citation2016). It seems therefore that ‘Brexit politics is at least as much about identity’ and values as socio-economic condition(s) and that ‘The calls to “leave Europe” do not merely appeal to those feeling left behind economically, but they exploit feelings of cultural alienation and actively appeal to racist sentiments, too’ (Isakjee & Lorne, Citationin press, p. 3). Immigration and ‘theoretical’ sovereignty were certainly key concerns of voters from far beyond ‘Left Behind Britain’ (Goodwin, Citation2017), notably (though not solely) across older more affluent and socially conservative demographics, evoking an imaginary perhaps of ‘Comfortable Britain’, or perhaps ‘Blimp and Boomer land’.Footnote3

‘Poor Britannia’

Immediately following the referendum and over the subsequent period, many observers pointed to a territorial contradiction in the results. Many areas that have not only been the key UK beneficiaries of EU regional funding, but which – even more significantly, have economies that are more integrated with the rest of the EU than those of London and the South East, had voted strongly to leave the EU (McCann, Citation2016, Citation2018; Semple, Citation2017). To some observers, perhaps viewing regions and places as abstract economic containers, this appeared illogical – regardless of the power of socio-spatial imaginaries and Eurosceptic propaganda, how, they wondered, could people in some places be persuaded to vote against their own apparent material interests (i.e. in light of potential economic impacts)? A number of articles used the analogy of ‘foot shooting’ to describe this apparently pyrrhic choice (Wyn Jones, Citation2016).

The UK Government’s studies on the economic consequences of leaving the EU have considered three scenarios – staying in the Single Market, a trade deal with the EU, or no deal. In all these scenarios economic growth over the next 15 years is expected to be less than if the UK remains fully within the EU (Parker & Hughes, Citation2018). Yet aside from the effects at an aggregate UK level, the figures also indicate – as already suggested by academic studies (Chen et al., Citation2017; McCann, Citation2016, Citation2018), that the impacts will be varied across different parts of the UK, and that many leave voting areas will potentially be the most negatively affected economically if the UK does indeed leave the EU.

Here we seek to capture this picture of regressive distributional impacts and exacerbated uneven development by an imaginary we have termed ‘Poor Britannia’. There is a proximity to the ‘Left Behind Britain’ imaginary, but the two are not analogous as there are areas which are currently economically buoyant rather than ‘left behind’ due to the presence of certain sectors (e.g. automotive and aviation industries), but which come within the ambit of the Poor Britannia imaginary with its future orientated focus on potential economic consequences of leaving the EU.

A challenge for ‘Poor Britannia’ it that the ‘success’ of any post-EU UK is likely to be gauged mainly in economic terms and – crucially for ‘Left Behind Britain’, at the aggregate national scale. It is at this level that ‘Global Britain’ (see below) needs to be seen to ‘beat the competition’, and in keeping with past experiments in neoliberalisation it is still theoretically possible (despite the conclusions of most academic, UK government and EU studies) that aggregate growth may recover to, or exceed, the levels it would have attained if the UK had stayed in the EU. But even in such optimistic scenarios the distributional question of whether any such growth, if it occurs, trickles down to ‘Left Behind Britain’ through the natural functioning of the spatial economy, or some mild measures of redistribution, addressing the UK’s ‘national-regional economic problem’ (McCann, Citation2016) is a rather different matter. As Rosamond notes ‘The Anglo-liberal growth model arguably fell into crisis long before Brexit emerged as the dominant issue in British politics’ (2018, p. 4) and uneven development has been one of the persistent manifestations of this. The potential loss of the EEC/EU’s regional support structures, whose emergence partly reflected the needs of the ‘left behind’ parts of Britain and the UK’s own traditions (from the 1930s onwards until the end of the 1970s) of regional policy (Sykes & Schulze-Bäing, Citation2017), gives an added inflexion to such issues.

‘Global Britain’ or ‘Empire 2.0’?

The post- referendum period continues to lay bare how core spatial imaginaries of the Eurosceptic vision sit in contradiction and tension. This is unsurprising perhaps, as the ‘nativist’, ‘territorial communitarian’, ‘anti-globalist’, ‘insular’, ‘nostalgic’ narratives and spatial imaginaries articulated during, and for many years before the referendum, were mobilized in a leave campaign largely supported financially, and promoted through a media owned by, a cast of archetypal hyperglobalists (Cadwalladr, Citation2017; Coles, Citation2016). As Barber and Jones (Citation2017, p. 154) note:

In proclaiming that ‘June 23 was not the moment Britain chose to step back from the world, it was the moment we chose to build a truly Global Britain’. Theresa May was scrabbling for a new vision. But it was one at odds with an electorate which wanted to reverse the effects of globalisation

Global Britain and Empire 2.0 are also bound up in selective and hierarchical imaginaries. Links with ‘old friends’ in the ‘Anglosphere’ are emphasized, and for Siles-Brügge (Citation2018, p. 13) such ‘Talk of “kith and kin” has so far obscured deregulatory intentions and “Global Britain’s” potentially disruptive distributive impacts’. There is a notable tendency too to home in on a select number of countries in North America and Australasia. Environment Secretary, Michael Gove, for example, has invoked the notion of ‘sister countries across the globe such as Canada and New Zealand’ (Connolly, Citation2018), some of which it is stated want to ‘Help Brexit’ (note, not help Britain) (). Beyond such obvious questions as ‘Aren’t Nigeria and Zambia sister countries too?’, the representational imaginaries, of Global Britain/Empire 2.0 also have to contend with the fact that Commonwealth and other former dominions have so far given a lukewarm response to the suggestion of any form of rebooted British tutelage (Verheijen, Citation2018; Dickson, Citation2018), and countries like New Zealand and Australia are seeking trade deals with the EU (Boffey, Citation2018; Honey, Citation2018).

Figure 8. ‘New Zealand and Australia want to help Brexit’. Source: https://globalbritain.co.uk/. (accessed 22.05.18).

O wad some Pow’r the giftie gie us, to see oursels as ithers see us! (Burns, Citation1786)

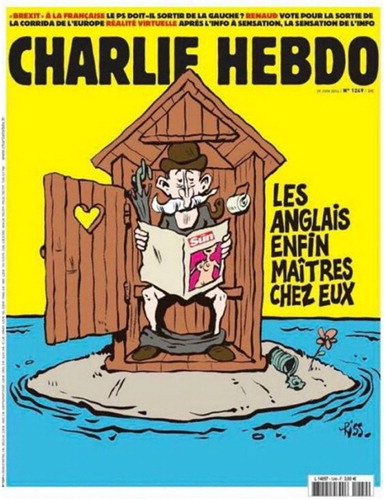

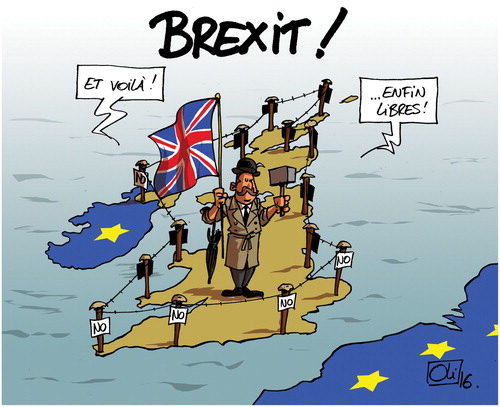

Global Britain/Empire 2.0 are revealing of how so often within ‘Brexit’ assumptions and imaginaries the external world is apparently a passive and supportive backdrop without its own materiality and/or existence autonomous to British interests and strategy. Thus for Rickett’s (Citation2017) ‘The Global Britain (or, dreadfully, Empire 2.0) rhetoric is based on an understanding of African and Commonwealth nations as junior partners who would jump at any opportunity to forge closer links with the UK’. Similarly, references to the ‘post-Brexit world’ which surface in conversations, the plans of organizations for the future, and even in some academic writing, may well be simply a turn of phrase, but if taken literally what might this imply? We might envisage a ‘post-Brexit Britain’ and a ‘post-UK EU’, but does the UK leaving the EU contain enough creative-destructive potential to generate a ‘post-Brexit world’? And if there are ‘Brexit’ imaginaries of Britain’s place in the world, then what are the ‘external’ world’s imaginaries of ‘Brexit’? There is no space here to consider these at length, but images from the French satirical newspaper Charlie Hebdo () and the Belgium cartoonist Oli (), provide views from two external observers which it is interesting to set alongside the Eurosceptic imaginary of Britain’s ‘insular exceptionalism’.

Figure 9. Les Anglais enfin maitres chez eux. Source: Artist Laurent ‘Riss’ Sourisseau. Retrieved from https://www.indy100.com/article/charlie-hebdo-gave-its-verdict-on-brexit-and-its-not-flattering--ZJf0gMYZSb.

Figure 10. Brexit! Et voila! Enfin libres! Source: Oli – Sudpresse (Belgium) 25/06/2016. http://www.humeurs.be/2016/06/brexit-good-bye-uk/sp20160624_brexit-1000/.

Conclusion

The UK’s EU referendum and its aftermath point to the importance of paying attention to the performativity of spatial imaginaries and the ‘far reaching claims’ they generate ‘on our social and political lives’ (Davoudi, Citation2018, p. 97). This requires further engagement with issues only tangentially considered above including citizenship, identity, different notions of political legitimacy, and populism, which entertain close links with representational and performative spatial imaginaries. It seems clear, for example, that the imaginaries discussed above are laced with markers of what Jessop terms a ‘wider organic crisis in the social order, reflected in contestation over “British values”, disputed national and regional identities, north–south and other regional divides, the metropolitan orientation of intellectual strata, and generational splits’ (Citation2018, pp. 1736–1737). And with similar scenes and political-spatial narratives being played out in other places – e.g. notions of ‘Main Street v. Wall Street’ in the US, or the ‘peripheral v. metropolitan France’ imaginaries of the French presidential campaign of 2017, there is potential for an international research agenda addressing questions such as ‘what work do spatial imaginaries do in agonistic political processes’, and ‘what subsequent demands do they make on policy development’?

In the aftermath of the UK’s 2016 EU referendum, as Isakjee and Lorne (Citationin press, p. 1) note the ‘proposition of the “left behind”’ has become particularly prevalent, the disaffection of whom it is thought to have contributed’ to the referendum result’. It is persuasive to consider that the associated spatial imaginary of ‘Left Behind Britain’ has subsequently attained significant perfomative agency, capturing a sense of dissatisfaction with an imperfect present, which has been conscripted by the leave lobby as the problem to which the classic ‘solution in search of a problem’ of ‘Brexit’ becomes the ‘revolutionary’ answer (The Economist, Citation2017). The question of what, if any, future social settlement, equilibrium, or ‘new normal’ might look like however remains wide open and contested – the performative potential arises from the representational properties rather than material outworkings of the imaginary. The ‘left behind’ narrative and imaginary also contributes to evacuating other readings of the territoriality of the referendum vote, laying its causes firmly before the door of ‘Left Behind Britain’ – a convenient strategy of ‘forward defence’ perhaps for the Brexit elites if the journey to the sunlit uplands is less straightforward than promised. It also legitimates ‘Brexit’, short-circuiting resistance, and cleverly ‘stealing the clothes’ of progressives’ established concern with uneven development, though without so far offering anything of material substance in its place. Yet whilst we would argue that the Eurosceptic lobby has had considerable success in generating and mobilizing imaginaries and conscripting emergent imaginaries to its cause in the UK’s long running European debate and since 2016, it is clear that tensions remain within and between the spatial imaginaries through which ‘Brexit’ is being represented and performed politically – not least as regards future growth model(s) for the UK and their spatial implications (Rosamond, Citation2018). With poorer regions predicted to be the biggest economic losers of any version of ‘Brexit’ (McCann, Citation2018) these are issues of material consequence. Nor do such issues arise in an historical vacuum, for as Jessop observes, not only has the UK evolved a ‘divergent set of regional economies with marked differences in economic structure, sectoral composition and trade performance’, but ‘These problems are aggravated by the historical weakness of the British state and its inability to pursue a serious economic strategy consistently and effectively’ (Citation2018, p. 1735). The dominant ‘legitimating’ imaginary of the referendum and its aftermath ‘Left Behind Britain’, thus sits uneasily with the predictions of ‘Brexit’s negative material impacts on this geography if the UK leaves the EU – the imaginary of ‘Poor Britannia’. It also resides in tension with the ‘Brexit’ project’s nationally and externally/globally orientated imaginaries of ‘Global Britain/Empire 2.0’ which essentially seek to promulgate a nostalgia-tinged version of the neoliberal and ‘free trade’ focussed accumulation strategies partly credited with creating ‘the space for extreme populist blowback against neoliberalization’ in the first place (Jessop, Citation2018, p. 1733). Despite the proto-Brexit state’s initial apparent ‘hearing’ of the call of ‘Left Behind Britain’ in the early days following the referendum, it is the giddy hyper liberal and/or nostalgic imaginaries of Britain’s new/rediscovered place in the world that continue to excite the imagination of many of those who willed ‘Brexit’ on the nation.Footnote5 Such confrontations and contradictions may yet provide the ‘Brexit project’ with some of its biggest challenges and call for continued attention from geographers, not just to how they surface in any emergent geopolitical and economic settlements at global, regional, national and substate scales, but also to how in practice ‘Brexit surfaces across a variety of everyday scenes and situations’ (Anderson & Wilson, Citation2018). Across the scales and types of imaginary which have apparently served the Eurosceptic cause so well, the agency of physical and material geographies should also not be underestimated. The irreducible properties of physical distance and time, the logics of territorial scale, the ‘real’ mechanics of international trade, and the predicted uneven internal regional impacts of leaving the EU within the UK, may lead even some proponents of ‘Brexit’ to discover that geography still matters in enduring and novel ways, which may yet interpolate some of the ‘geographical’ imaginings that underpin their project.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes on contributor

Olivier Sykes, PhD, is a senior lecturer in the School of Environmental Sciences, and policy impact fellow of the Heseltine Institute for Public Policy and Practice, at the University of Liverpool.

Research

His PhD was completed at the University of Liverpool and examined the application of the European spatial Development Perspective (ESDP) in EU Member State planning. He followed up this work as part of the ESPON 2006 which examined the ESDP’s application across the whole of ESPON space. More recently Olivier was part of the team which conducted the ESPON EATIA project. He has also worked on other EU, UN HABITAT, and UK government funded research projects. He has published extensively across a range of themes relating to the international dimensions of spatial planning in a range of international peer-reviewed journals.

Appointments and posts

He has been a Visiting Professor at a number of universities including Paris I, Paris IV, Paris VII, Western Brittany, Valencia and Tours. He is a member of the editorial boards of Town Planning Review; Transactions of the Association of European Schools of Planning; and, Information Géographique. Olivier also has extensive experience of writing for and presenting to non-specialist audiences, notably around heritage and European issues. In recent years he has produced work for non-academic bodies such as the Centre for Labour and Social Studies and the Common Futures Network in the UK, notably surrounding the potential departure of the UK from the EU and its possible consequences. He has appeared at public inquires on controversial planning issues and been interviewed for local and national radio in the UK and France on his areas of expertise.

Selected recent publications

Sykes, O., & Fischer, T. (2017). Impact assessments? What impact assessments? Is anybody actually planning to leave the EU? Town and Country Planning.

Sykes, O., & Schulze Bäing, A. (2017). Regional and territorial development policy after the 2016 EU referendum – initial reflections and some tentative scenarios. Local Economy, 32(3), 240–256.

Sykes, O. J. (2017). Things we lost in the fire. Town and Country Planning.

Sykes, O., & Ludwig, C. (2016). Aftermath: The consequences of the result of the 2016 EU referendum for heritage conservation in the United Kingdom. Town Planning Review, 87(6), 619–625.

Sykes, O. J., & Schulze-Bäing, A. (2016). An idea of Europe? An idea of planning. Town and Country Planning. London: Town and Country Planning Association.

O Brien, P., Sykes, O., & Shaw, D. (2017). Evolving conceptions of regional policy in Europe and their influence across different territorial scales. In Territorial Policy and Governance: Alternative Paths (pp. 35–52).

O’Brien, P., Sykes, O., & Shaw, D. (2015). The evolving context for territorial development policy and governance in Europe – from shifting paradigms to new policy approaches. L’Information géographique, 79(1), 72. doi:10.3917/lig.791.0072.

Notes

1. The term ‘European debate’ is used here to refer to the decades long deliberation in UK politics about the relationship between the UK and the rest of Europe and the various versions of ‘the European project’ which have evolved since WW2. The term is deliberately used here to recognize that there is a ‘prehistory’ to the notion of a so-called ‘Brexit’ of the UK from the present European Union (EU) and that a number of the spatial imaginaries which can be identified around the 2016 EU referendum and its aftermath draw heavily upon this.

2. The ‘Leave campaign’ featured a number of different campaigns principally Vote Leave and Leave.EU. Initially seen by some as a potential weakness, the plurality of the Leave campaign may well have been one of the decisive factors in the result, allowing the Leave message to be tailored to different social groups and certain statements to be supported, or disavowed by those campaigning to leave the EU. This was notably the case surrounding the notorious ‘red bus’ claim about future funding for the National Health Service (NHS) (Merrick, Citation2017) and the varying degrees of nationalist and xenophobic rhetoric emanating from different parts of the campaign. It also allowed funding limits to be breeched through the creation of shadow groups which received significant extra resources in the last days of the campaign (Shipman & Ungoed-Thomas, Citation2018). In the remainder of this paper the term ‘Leave campaign’ will be used with specific detail of which ‘wing’ of this is being referred to being supplied where necessary.

3. The term ‘blimpish’ emerged after the creation of the character Colonel Blimp by cartoonist David Low for the London Evening Standard in 1934. It has come to be used as shorthand for pompous persons holding reactionary views, sometimes with a nostalgic hankering after an Imperial past, perhaps with implicit undertones of xenophobia, or even racism. The term ‘Boomer’ refers to the Baby Boomer generation, a demographic which voted to leave more heavily than younger generations adding to existing feelings of intergenerational iniquity (McKernan, Citation2016; Elledge, Citation2017) and leading to a surge what some termed ‘boomer blaming’ (Bristow, Citation2017).

4. The idea of building a new Royal Yacht has been floated as a way to help boost British trade prospects (Worley, Citation2018). It was not reported, however, if this was to come pre-equipped with pith helmets.

5. Former UK Foreign Secretary Boris Johnson even called for his department to have its own plane to help boost ‘post-Brexit’ trade prospects (Stewart, Citation2018).

References

- Abrahams, G. (2013). What “is” territorial cohesion? What does it “do”?: Essentialist versus pragmatic approaches to using concepts. European Planning Studies, 2013, 1–22. doi: 10.1080/09654313.2013.819838

- Anderson, B. (1991). Imagined communities: Reflections on the origin and spread of nationalism (Revised and Extended ed.). London: Verso.

- Anderson, B., & Wilson, H. (2018). Everyday Brexits. Area, 50(2), 291–295. doi: 10.1111/area.12385

- Bachmann, V., & Sidaway, J. D. (2016). Brexit geopolitics. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences, 77, 47–50.

- Barber, S., & Jones, A. (2017). Jumping off the cliff? Local Economy, 32(3), 153–155. doi: 10.1177/0269094217706646

- Boffey, D. (2018, May 22). EU talks with Australia and New Zealand deal blow to UK free trade plans – Bloc could end up on better terms with the commonwealth nations after Brexit than UK. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2018/may/22/eu-trade-talks-australia-new-zealand-brexit-commonwealth

- Bristow, J. (2017, February 20). How did baby boomers get the blame for Brexit? LSE. Retrieved from http://blogs.lse.ac.uk/brexit/2017/02/20/how-did-baby-boomers-get-the-blame-for-brexit/

- Burns, R. (1786). To a Louse, on seeing one on a lady’s bonnet at Church. Retrieved from http://www.robertburns.org/works/97.shtml

- Cadwalladr, C. (2017, May 7). The great British Brexit robbery: How our democracy was hijacked. The Observer. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2017/may/07/the-great-british-brexit-robbery-hijacked-democracy

- Cadwalladr, C., & Jukes, P. (2018, June 9). Arron Banks ‘met with Russian officials multiple times before Brexit vote’. The Observer. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2018/jun/09/arron-banks-russia-brexit-meeting

- Chen, W., Los, B., McCann, P., Ortega-Argilés, R., Thissen, M., & van Oort, F. (2017). The continental divide? Economic exposure to Brexit in regions and countries on both sides of the channel. Papers in Regional Science, 2017, 1–30. doi: 10.1111/pirs.12334

- Coates, S. (2017, March 6). Ministers aim to build ‘empire 2.0’ with African commonwealth. The Times. Retrieved from https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/ministers-aim-to-build-empire-2-0-with-african-commonwealth-after-brexit-v9bs6f6z9

- Coles, T. J. (2016). The Great Brexit Swindle: Why the mega-rich and free market fanatics conspired to force Britain from the European Union. West Hoathly: Clairview Books.

- Connolly, S. (2018). Brexit Britain offers migrants a warmer welcome, says Gove. Metro, 22 May 2018. Retrieved from https://www.metro.news/brexit-britain-offers-migrants-a-warmer-welcome-says-gove/1067061/

- Crawford, J. (2017). Spatial imaginaries of ‘coast’: Case studies in power and place (Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation). Newcastle: University of Newcastle Upon Tyne. Retrieved from http://ethos.bl.uk/OrderDetails.do?uin=uk.bl.ethos.728338

- Crawford, J. (2018). Constructing ‘the coast’: The power of spatial imaginaries. Town Planning Review, 89(2), 108–112.

- Davis, D. (2016, May 27). Britain is not like other countries – even the EU will be forced to treat us fairly. Daily Telegraph. Retrieved from https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2016/05/27/britain-is-not-like-other-countries--even-the-sclerotic-eu-will/

- Davoudi, S. (2018). Imagination and spatial imaginaries: A conceptual framework. Town Planning Review, 89(2), 97–124. doi: 10.3828/tpr.2018.7

- Devine, D. (2018, March 19). Hate crime did spike after the referendum – even allowing for other factors. Blogs.lse.ac.uk. Retrieved from http://blogs.lse.ac.uk/brexit/2018/03/19/hate-crime-did-spike-after-the-referendum-even-allowing-for-other-factors/

- Dickson, A. (2018, February 26). Ex-colonies to UK: Forget Brexit ‘empire 2.0’. POLITICO. Retrieved from https://www.politico.eu/article/commonwealth-summit-wont-be-empire-2-0-for-brexit-uk/

- Domokos, J. (2018, January 9). Stokies strike back: The Potteries people scotching their ‘Brexit capital’ rep. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/film/2018/jan/09/made-in-stoke-on-trent-proud-potteries-people-scotching-brexit-capital-rep

- Dorling, D. (2016). Brexit: The decision of a divided country. BMJ, 354, i3697. Retrieved from www.dannydorling.org/wp-content/files/dannydorling_publication_id5564.pdf doi: 10.1136/bmj.i3697

- The Economist. (2017, April 3). Brexit: A solution in search of a problem – until the referendum, Britons were unbothered by European matters. The Economist. Retrieved from https://www.economist.com/britain/2017/04/03/brexit-a-solution-in-search-of-a-problem

- Elgot, J. (2016, January 27). How David Cameron’s language on refugees has provoked anger. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2016/jan/27/david-camerons-bunch-of-migrants-quip-is-latest-of-several-such-comments

- Elledge, J. (2017, August 1). This YouGov research on Brexit proves baby boomers hate their own children. New Statesman. Retrieved from https://www.newstatesman.com/2017/08/yougov-research-brexit-proves-baby-boomers-hate-their-own-children

- European Commission. (2010). Europe 2020 – a European strategy for smart, sustainable and inclusive growth. Brussels. Retrieved from http://europa.eu/press_room/pdf/complet_en_barroso___007_-_europe_2020_-_en_version.pdf

- European Commission. (2017). My region, my Europe, our future – seventh report on economic, social and territorial cohesion. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. Retrieved from http://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/sources/docoffic/official/reports/cohesion7/7cr.pdf

- European Commission. (2018). Connecting Europe facility. Retrieved from https://ec.europa.eu/inea/en/connecting-europe-facility

- Faludi, A. (2007). Territorial cohesion and the European model of society. Cambridge, MA: Lincoln Institute of Land Policy.

- Ferrara, A. (2007). Europe as a “special area for human hope”. Constellations, 14(3), 315–331. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8675.2007.00448.x

- Finlayson, A. (2016, June 26). Who won the referendum? Blog post. Open Democracy. Retrieved from https://www.opendemocracy.net/uk/alan-finlayson/who-won-referendum

- Fox, L. (2016). Liam Fox’s free trade speech. Delivered at Manchester Town Hall on 29 September. Retrieved from https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/liam-foxs-free-trade-speech

- Goodwin, M. J. (2017, October 16). Brexit: Causes and consequences, Royal Geographical Society, Monday Night Lectures. Retrieved from http://www.matthewjgoodwin.org/uploads/6/4/0/2/64026337/leave_vote_lecture.pdf

- Hague, C. (2016, June 24). Brexit – why and what next? Retrieved from http://www.cliffhague.com/index.php?option=com_k2&view=item&id=286:brexit-why-and-what-next&Itemid=161

- Hannan, D. (2011). Why America must not follow Europe. New York: Encounter Books.

- Hay, C. (2011). Pathology without crisis? The strange demise of the anglo-liberal growth model. Government and Opposition, 46(1), 1–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-7053.2010.01327.x

- Healey, P. (2007). Urban complexity and spatial strategies: Towards a relational planning for our time. London: Routledge.

- Hoggart, R., & Johnson, D. (1987). An idea of Europe. London: Chatto and Windus.

- Honey, S. (2018, May 24). EU-NZ trade deal a bright spot in gloomy times. Radio New Zealand. Retrieved from https://www.radionz.co.nz/news/on-the-inside/358156/eu-nz-trade-deal-a-bright-spot-in-gloomy-times

- Isakjee, A., & Lorne, C. (in press). Bad news from nowhere: Race, class and the ‘left behind’. Environment and Planning C.

- Jackson, H., & Ormerod, P. (2017, July 14). Was Michael Gove right? Have we had enough of experts? Prospect. Retrieved from https://www.prospectmagazine.co.uk/magazine/michael-gove-right-about-experts-not-trust-them-academics-peer-review

- Jensen, O. B., & Richardson, T. (2004). Making European space: Mobility, power and territorial identity. London: Routledge.

- Jessop, B. (2018). Neoliberalization, uneven development, and Brexit: Further reflections on the organic crisis of the British state and society. European Planning Studies, 26(9), 1728–1746. doi: 10.1080/09654313.2018.1501469

- Kaufmann, E. (2016, July 7). It’s not the economy, stupid: Brexit as a story of personal values. LSE British Politics and Society. Retrieved from http://blogs.lse.ac.uk/politicsandpolicy/personal-values-brexit-vote/

- Kerbaj, R., Wheeler, C., Shipman, T., & Harper, T. (2018, June 9). Exclusive: Emails reveal Russian links of millionaire Brexit backer Arron Banks. The Sunday Times. Retrieved from https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/exclusive-emails-reveal-russian-links-of-millionaire-brexit-backer-arron-banks-6lf5xdp6h

- Kunzmann, K. R., & Wegener, M. (1991). The pattern of urbanisation in Western Europe 1960–1990. Berichte aus dem Institut für Raumplanung 28. Dortmund: Institut für Raumplanung, Fakultät Raumplanung, Universität Dortmund.

- Lefebvre, H. (1974). La production de l’espace. Paris: Editions Anthropos.

- Manley, D., Jones, K., & Johnston, R. (2017). The geography of Brexit – what geography? Modelling and predicting the outcome across 380 local authorities. Local Economy, 32(3), 183–203. doi: 10.1177/0269094217705248

- McCann, P. (2016). The UK regional–national economic problem geography, globalisation and governance. London: Routledge.

- McCann, P. (2018). 5 Provocations regarding the UK regional and urban development challenges in a post-Brexit environment – for discussion by the common futures network. Retrieved from http://commonfuturesnetwork.org/?mdocs-file=561

- McKernan, B. (2016, June 24). Now Britain is leaving the EU, people are re-sharing this quote summing up the nation’s generational divide. The Independent. Retrieved from https://www.indy100.com/article/now-britain-is-leaving-the-eu-people-are-resharing-this-quote-summing-up-the-nations-generational-divide--Z1gnlh9v24b

- Merrick, R. (2017). Brexit: Vote Leave chief who created £350m NHS claim on bus admits leaving EU could be 'an error'. The Independent, Tuesday 4 July 2017. Retrieved from https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/politics/brexit-latest-news-vote-leave-director-dominic-cummingsleave-eu-error-nhs-350-million-lie-bus-a7822386.html.

- Nadin, V., & Stead, D. (2008). European spatial planning systems, social models and learning. disP, 172(1), 35–47.

- National Centre for Social Research. (2016). Understanding the leave vote. Retrieved from http://natcen.ac.uk/our-research/research/understanding-the-leave-vote/

- Owen, G. (2011, April 30). ‘The EU are trying to wipe us off the map’: Brussels merges England and France in new Arc Manche region … with its own FLAG. Daily Mail. Retrieved from http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-1382263/The-EU-trying-wipe-map-Brussels-merges-England-France-new-Arc-Manche-region--FLAG.html#ixzz5GgvLOC00

- Parker, G., & Hughes, L. (2018, February 9). What the UK’s Brexit impact assessments say. Financial Times. Retrieved from https://www.ft.com/content/06c6ffc0-0cf9-11e8-8eb7-42f857ea9f09

- Piketty, T. (2016, June 30). Reconstructing Europe after Brexit. Le Monde (M Blog). Retrieved from http://piketty.blog.lemonde.fr/2016/06/30/reconstructing-europe-after-brexit/

- Rickett, O. (2017, March 13). Politicians are trying to rewrite history with their ‘British empire 2.0’ inglorious empire. Huck Magazine. Retrieved from http://www.huckmagazine.com/perspectives/inglorious-empire-brexit/IngloriousEmpire

- Rosamond, B. (2018). Brexit and the politics of UK growth models. New Political Economy. doi: 10.1080/13563467.2018.1484721

- Said, E. (1978). Orientalism. New York: Pantheon Books.

- Santamaria, F., & Elissalde, B. (2018). Territory as a way to move on from the aporia of soft/hard space. Town Planning Review, 89(1), 43–60. doi: 10.3828/tpr.2018.3

- Semple, B. (2017, January 30). EU trade deal must be Government’s top priority in Brexit negotiations – as new report shows EU is biggest export market for 61 of Britain’s 62 cities. Retrieved from http://www.centreforcities.org/press/eu-trade-deal-must-governments-top-priority-brexit-negotiations-new-report-shows-eu-biggest-export-market-61-britains-62-cities/

- Shipman, T. (2006, September 4). New map of Britain that makes Kent part of France … and it’s a German idea. Daily Mail. Retrieved from http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-403522/New-map-Britain-makes-Kent-France--German-idea.html#ixzz5Ggt2gUpk

- Shipman, T., & Ungoed-Thomas, J. (2018, March 25). Whistleblower: Leave lobby ‘cheated’ its way to Brexit victory. The Sunday Times. Retrieved from https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/whistleblower-leave-lobby-cheated-its-way-to-brexit-victory-3bkvh0nxp

- Siles-Brügge, G. (2018). Bound by gravity or living in a ‘post geography trading world’? Expert knowledge and affective spatial imaginaries in the construction of the UK’s post-Brexit trade policy. New Political Economy. doi: 10.1080/13563467.2018.1484722

- Stewart, H. (2018, May 22). Boris Johnson wants a plane as PM’s is rarely available – and too grey. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2018/may/22/boris-johnson-foreign-office-own-plane-voyager

- Stiglitz, J. (2017, December 5). Globalisation: time to look at historic mistakes to plot the future. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/business/2017/dec/05/globalisation-time-look-at-past-plot-the-future-joseph-stiglitz

- Sykes, O., & Schulze-Bäing, A. (2017). Regional and territorial development policy after the 2016 EU referendum – initial reflections and some tentative scenarios. Local Economy, 32, 240–256. doi: 10.1177/0269094217706456

- Varoufakis, Y. (2016). And the weak suffer what they must: Europe, austerity and the threat to global stability. London: The Bodley Head.

- Verheijen, D. (2018, May 3). Africa will turn its back on Britain. The New European. Retrieved from http://www.theneweuropean.co.uk/top-stories/danladi-verheijen-africa-will-turn-its-back-on-britain-1-5502848

- Waterhout, B. (2007). Territorial cohesion: The underlying discourses. In A. Faludi (Ed.), Territorial cohesion and the European model of society (pp. 37–59). Cambridge, MA: Lincoln Institute of Land Policy.

- Watkins, J. (2015). Spatial imaginaries research in geography: Synergies, tensions, and new directions. Geography Compass, 9(9), 508–522. doi: 10.1111/gec3.12228

- Wintour, P. (2018, January 10). Russian bid to influence Brexit vote detailed in new US Senate report. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/jan/10/russian-influence-brexit-vote-detailed-us-senate-report

- Worley, W. (2018, October 13). Brexit: Ministers try to push through plans for £100m royal yacht as EU talks remain deadlocked. The Independent. Retrieved from https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/politics/brexit-ministers-royal-yacht-plans-eu-uk-negotiations-talks-deadlock-queen-a7998021.html

- Wyn Jones, R. (2016, June 27). Brexit refletions – why did wales shoot itself in the foot in this referendum? Retrieved from http://www.centreonconstitutionalchange.ac.uk/blog/brexit-reflections-why-did-wales-shoot-itself-foot-referendum

- Young, H. (1998). This blessed plot: Britain and Europe from Churchill to Blair. London: Macmillan.

- Young, H. (2016). Hugo Young: Why Britain never sat comfortably in Europe. The Guardian, 25 June 2016. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2016/jun/25/hugo-young-why-britain-never-sat-comfortably-in-europe.