ABSTRACT

This Special Issue (SI) of Space and Polity profiles the varied contributions of geographical inquiry to scholarly debates on the causes, meaning and implications of the UKs decision to Brexit from the EU. By way of framing the SI, this Introduction develops the argument that insofar as it is confronting, complicating and challenging geographical ideas and debates, Brexit recursively is intruding on and perhaps even implicating itself in the structuration of geographic thought and practice, most immediately in the UK and in European states particularly impacted (not least Ireland) and especially with respect to political geographical research. We develop this argument through five provocations, questioning the ways in which Brexit exists as a troubling reality for: a) critical policy studies; b) the project of decolonizing geography; c) historiographies of human territorialization and sovereignty; d) the status of evidence-based public policy in a post-political and post-truth age, and; e) the management of risk, hazards, and disasters. A completing/completed Brexit we conclude, may bequeath a tradition of ‘Brexit Geographies’ and therein leave an enduring signature on the history of Anglo-European geographic thought.

Introduction

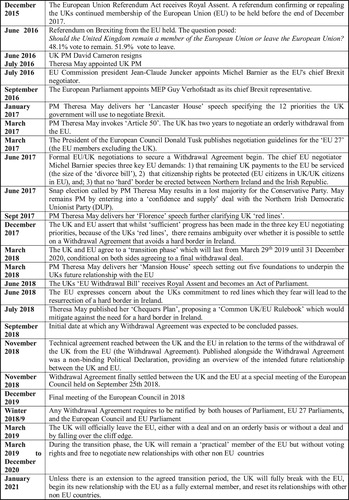

The United Kingdom (UK) joined the European Economic Community (EEC) on 1 January 1973 and remained a committed member of this community for 43 subsequent years as it broadened (incrementally to 28 member states) and deepened (morphed into the world's most sophisticated supra-national political union, ‘the European Union’ (EU)). On June 23rd 2016, the UK held a plebiscite on the status of its ongoing membership: with a turnout of 72.2%, 51.9% voted to ‘Leave the EU’. On March 29th 2017, UK Prime Minister Theresa May invoked ‘Article 50’ of the Treaty on European Union, announcing the UKs intention to exit the EU in an orderly fashion; firstly by entering into a two-year withdrawal negotiation and secondly on successful conclusion of this negotiation by brokering a new relationship with the EU as a fully external but ‘special’ non-member state. On November 14th 2018, a technical agreement was reached between the UK and the EU with regard to the terms of withdrawal. Subject to ratification of this Withdrawal Agreement, the UK will officially/legally leave the EU on March 29th 2019, following an expected twenty-one month transition period will practically/materially leave on 31 December 2020, and from 1 January 2021 will (it hopes) begin a new bespoke relationship with the bloc. But failure to conclude this agreement could yet precipitate a ‘no deal’ outcome and trigger a disorderly ‘Brexit’ (British exit from the EU), a possibility which fills every party (with the exception of committed Brexiteers) with deep foreboding (see ).

Our motive for convening this SI is to interrogate the ways in which Brexit presents as an object of analysis for human geographers. Brexit is proving to be immediately traumatic for res publica, impinging upon the polity in multiple, and sometimes unpredictable, ways. Whatever form it will eventually take, it is clear that the series of secession challenges it embodies and in turn has triggered will have profound long-term territorial ramifications for both the EU and the UK, a multi-nation, yet highly centralized state (Paddison & Rae, Citation2017; Jessop, Citation2017, Citation2018). Evidently, even if the preferred outcome in any future ‘people's vote’, there can be no return to the status quo. The papers offered here do not pretend to provide a comprehensive panoramic snapshot of geographical writings on Brexit; what they do offer, however, is an indication of the emergent multiplicity of Brexit's geographical dimensions, including its origins, its social, economic, political and cultural impacts, and its potential legacies. Contributors ruminate on topics as diverse as the aetiology of Brexit in a gradual exhaustion of consent for the neoliberal political economic mainstream in English regions (MacLeod and Jones); the spatial grammars, lexicons and imaginaries which have been deployed to render Brexit intelligible (but which more often obfuscate, Sykes); the extent (or not) to which Brexit signals a fundamental recalibration in the UKs two party electoral hegemony (Johnston et al.), the impact of Brexit on the Irish border and the Irish border on Brexit (papers by Hayward and Anderson), the new politics of hospitality, estrangement and belonging wrought by Brexit in both the UK (Cassidy et al.) and in Ireland (Wood and Gilmartin), the much neglected gender politics of Brexit (MacLeavy) and the differential implications of Brexit for rural and agricultural communities in different locations (Maye et al.).

Vital geographies which speak to the grand challenges of the day are by their very nature risky and precarious. What needs emphasizing is that the papers included in this SI, as also this Introduction, have been written while Brexit has been unfolding. Ours is a restless, dynamic, and incomplete subject matter; our stocktaking, interpretations and commentaries are necessarily tentative, provisional and at times conjectural. Clearly acute problems attend to the analysis of such a dynamic process; the importance of Brexit, however, dictates that such analysis is undertaken, even at the peril of being overtaken by events and quickly rendered obsolete. Nearly half a century ago, in a themed intervention published in the Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers (TIBG) and titled, Geography and public policy: challenges, opportunities and implications, Terry Coppock questioned the adequacy of the contribution of geographers to public policy, whether that be at the point of policy conception, prototyping, piloting, enactment or evaluation. ‘If we do not seek to demonstrate our skills more actively’ he warned, ‘we shall increasingly find that the opportunities are no longer open to us and that other disciplines will fill the roles which we are well qualified to fill’ (Coppock, Citation1974, p. 15). Whilst we are all too conscious of the maxim – only fools rush in – we also note that Coppock’s warning has catalyzed a generation of debate and lost none of its bite.

In pursuit of ‘Brexit Geographies’

In his 1984 ‘historical materialist manifesto’ for the study of the ‘history and present condition of Geography’, David Harvey famously argued that all geographical knowledge is produced within history (Harvey, Citation1984). The story of the history of Geography could not be told apart from the story of the history of European exploration, racism, empire and science, western global politico-economic hegemony, and the changing needs of mercantile, industrial, and finance capital. In The Geographical Tradition, David Livingstone (Citation1992) commented upon the particular challenges which attend to writing contextualist histories of still live, fledgling and yet to be fully formed geographical traditions. Yet, historians of Geography are already alert to the imprint of western civilization's twentieth and early twenty-first century existential crises and melancholic malaise on geographical thought (Harvey, Citation1989). In time, these histories will surely come to register the particular significance of globalization, the legacy of tenacious imperial thought structures, uneven geographic development, the current dislocate between popular sovereignty and representative democracy, and the surge, albeit uneven, throughout the advanced capitalist world of political populism and consequential ‘earthquake’ elections and referenda which have shocked the body politic. Whilst the Right has shown itself to be particularly adept at seizing the moment (Trump, Farage, Hofer, Wilders, Kurz, Orban Le Pen, Bolsonaro), Left populisms too have entered the fray (for example Syriza, Podemos, Costa, Sanderson, Corbyn). This age of chaos and turbulence is undoubtedly exerting influence on our discipline by working as a disruptive force, provoking introspection, reflexivity, and new conceptual and methodological orientations.

By way of framing the SI, this Introduction develops the argument that insofar as it is confronting, complicating and challenging existing geographical ideas and debates, Brexit is already recursively intruding on and perhaps even implicating itself in the structuration of geographic thought and practice, at least in countries most impacted and especially with respect to political geographical research. A completing/completed Brexit we suggest may bequeath a tradition of ‘Brexit Geographies’ and end up leaving a lasting signature on the stratigraphic record of Anglo-European geographic thought. We delimit the geographical scope of our claim with care; only metropolitan arrogance would presume that Brexit is of world historical import and it is likely that its signal will fail to leave much of a trace in geographical traditions elsewhere and particularly in the Global South. We now develop our argument through five provocations, questioning the ways in which Brexit exists as a troubling reality for: a) critical policy studies; b) the project of decolonizing geography; c) historiographies of human territorialization and sovereignty; d) the status of evidence-based public policy in a post-political and post-truth age, and; e) scholarship on hazards, risk, disasters and resilience. By presenting itself as an anomalous protrusion in these arenas of geographical enquiry, Brexit may result in each case in new foci, fresh concepts, revised understandings, recalibrated priorities, and altered methodologies.

Brexit Geographies: five provocations

Why did the British public vote for Brexit? Political scientists and electoral geographers have pored over the details of both the Leave and Remain votes and reached a number of shared conclusions (see Johnston et al. in this collection – and Becker, Fetzer, & Novy, Citation2017; Lee, Morris, & Kemeny, Citation2018; Leslie & Arı, Citation2018; Manley, Jones, & Johnston, Citation2017; Zhang, Citation2018). In the welter of analyses, distinctions need to be made between the associated, as opposed to the causal, factors linked to the Leave vote.

Invariably, and notwithstanding the fact that the Leave campaign attracted affluent rural voters, Brexit came to be associated with the politics of the urban ‘left behinds’. In this sense the vote to Leave has been characterized as a ‘revolt of the rustbelt’ (see MacLeod and Jones in this collection – and Bromley-Davenport, MacLeavy, & Manley, Citation2018; Calhoun, Citation2016; Dorling, Citation2016; Ford & Goodwin, Citation2017; Goodwin & Heath, Citation2016; Gordon, Citation2018; Hazeldine, Citation2017; Hobolt, Citation2016; Jensen & Snaith, Citation2016). Globalization, neoliberalism, inequalities, the global financial crash and austerity have combined, it seems, to effect a growing dissonance between representative democracy and popular sovereignty (Jessop, Citation2018). Counterposed to the ‘globalists’ and hypermobile ‘anywheres’, the left behinds constitute the ‘somewheres’ (Goodhart, Citation2017), marked by particular class, education and age profiles, and anchored in places often rendered redundant by global capital, abandoned it seems to managed decline, and reeling from a decade of austerity (see MacLeod and Jones in this collection, Picketty, Citation2013). In the UK and more specifically England it is supposed, this historical dynamic has played itself out in the form of the accelerated growth of London and the South-East and comparative lack of prosperity and opportunity in other regions, in particular Northern regions, a growing sense in the latter of limited futures and alienation, and a vote to Brexit from the EU (Brakman, Garretsen, & Kohl, Citation2018; Daly & Kelly, 2015; Hobolt, Citation2016; Jessop, Citation2017; McCann, Citation2018; Parkinson 2016; North, Citation2017).

Perhaps the yardstick for any purposeful political response to Brexit then might be the extent to which it addresses the plight of those communities excluded from the globalization project. But immediately, it becomes clear that Brexit constitutes an elusive object of enquiry: we might wish to speak truth to power, but this is problematic given that the ancien régime is split on Brexit. In fact, leaving the EU is as much an elite project as it is a populist one: likewise the campaign to reverse the vote to leave is being led by liberal elites but not exclusively so (See MacLeavy in this collection – and Anderson & Wilson, Citation2018). Perhaps we might conclude that whether Brexit happens or not is to an extent a diversion, what matters most is that the UK state attends to the historic inequalities which gave rise to the vote to leave in the first instance. There will be no ‘Global Britain’ without an inclusive Britain. Equally, there will no consensus to reverse Brexit unless a compelling case is made that inequalities will be most effectively addressed inside rather than outside the EU. Whether a high achieving Global Britain will eventually emerge remains to be seen; whether such a Global Britain will be pursued (by choice or coercion) through a low road strategy (a low tax and hyper liberalized open economy competing on the basis of cost and participating in the global race to the bottom) or a high road strategy (a high value added, high skill, high investment, high technology and high productivity economy) remains an open question.

But it would be a mistake to approach Brexit as a sideshow. Brexit is surely no distraction, obfuscating class politics. So profound is this disruption that its unfolding will make a material difference to the kinds of politics which are actually possible. It is difficult to escape the conclusion that critical geographical scholarship ought to have a view on the virtues and vices of Brexit, whether it occurs or not and how hard or soft it might be.

And so we reach our first provocation: some time ago, in the same themed intervention of TIBG convened by Coppock noted above, David Harvey (Citation1974) famously asked ‘What kind of Geography for what kind of public policy?’; lest their intellectual labour be appropriated, academic freedom impaired, and capacity for criticality compromised, there must exist a clear distance if not dissonance between scholars and the corporate state, construed as a ‘proto-fascist’ technocratic instrument to preserve and strengthen the status quo. Brexit demands a response from critical policy studies. But it is difficult to know what kind of geography is best placed to inform a critical policy framing of Brexit because it is difficult to know what kind of public policy Brexit is. How can one speak truth to power when it is unclear which policy option is the preserve of power? What is critical policy studies to do in an age of populism, when there is an apparent elision of interests between societal elites and ‘we the people’? The key question to ask then is; what kind of Brexit for what kind of public policy for what kind of Geography? Or alternatively; what kind of remain for what kind of public policy for what kind of Geography?

Other commentators have sought to apprehend Brexit as a post-imperial ‘nationalist spasm’, incorporating a wider set of constituencies (including middle class and rural England) failed by the decline of the British empire and the UKs diminishing political and economic significance in the world (see Sykes in this collection). Brexit is a nostalgic reflex which betrays an imperial yearning to restore Britain's lost place in the world (Bachmann & Sidaway, Citation2016; Dorling & Tomlinson, Citation2018; Picker, Murji, & Boatcă, Citation2019). In their book Rule Brittania Dorling and Tomlinson (Citation2018, p. 15) capture this line of argument succinctly: ‘in the near future the EU referendum will become widely recognized and understood as part of the last vestiges of empire working their way out of the British psyche’. And so ‘Global Britain’ invokes without effort hierarchies and thought structures still lingering from the days of the British Empire and pivots without hesitation to the British Commonwealth for trade deals. Construing the EU as an anti-democratic imperial institution, it betrays a metropolitan anxiety that a bad deal will mean it will be reduced itself to a ‘vassal’ state or colony of the EU. Displaying a bizarre colony envy, it ruminates on the possibility of creating a ‘Singapore on the Thames’.

This claim opens up fascinating new terrain for postcolonial scholarship which has sought to deconstruct ingrained colonial and metropolitan frames – orientalism and equivalents – which still run deep in European thought. In some ways Brexit endorses what post-colonial scholars have always suspected; imperial mentalities lurk deep in the dark recesses of the British mind. Only now, instead of seeking to provincialize, relativize and historicize ebbing and subsiding imperial epistemologies, postcolonial scholarship is being confronted by a resurgent reification of colonial imaginaries. Brexit gives new purpose to Postcolonial Geography. The project to decolonizing geographical thought is assuming new urgency. Unveiling the illusion that Britain remains vital in world history may yet be part of a wider move to encourage sobriety which may yet in turn save the country from itself. Psychoanalytic self-reflection and mindful meditation on crippling interior anxieties – surrounding fears both that the UK will be humbled into subservience through a soft-Brexit or unable to survive alone if cut adrift by a hard Brexit – may in time prove healing. It could enable an improved approach to international relations. It might help to address the changing atmosphere which has underpinned the politics of hospitality in the UK where Brexit has impacted upon immigrant communities (Doherty, Citation2016; Goodwin & Milazzo, Citation2017) whom have fallen prey to increased racial violence, revanchist nationalism, and reborderings of various sorts (see Wood and Gilmartin and Cassidy et al. in this collection – and Burnett, Citation2017 Gilmartin, Wood, & O’Callaghan, Citation2018; Lulle, Moroşanu, & King, Citation2018; Miller, Citation2018). It might also inform the prospects for UK expatriates dwelling in other countries amidst other cultures whose plight remains occluded (Benson, Collins, & O’Reilly, Citation2018; Higgins, Citation2018).

This leads us to our second provocation: that the conjunction between Post-Colonial geography and the lingering vestiges of small Britannia, given new life in and through Brexit, has the potential to give new purpose and substantive subject matter to the project of decolonizing geographical categories and modalities of analysis.

As we complete this Introduction, (November 2018), the UK and the EU have it seems managed in the end to secure a Withdrawal Agreement. But much uncertainty persists. Brexit remains up for grabs. Whether the politicians who brokered the agreement can survive, and whether this agreement can survive parliamentary scrutiny in the UK and the remaining EU27 states remains in question (Anthony, Citation2017; Dougan, Citation2017; Hayward & Murphy, Citation2018). Published alongside the Withdrawal Agreement was a non-binding Political Declaration, providing an overview of the intended future relationship between the UK and EU. This too remains a work in progress (Dougan, Citation2018). If ‘nothing can be agreed until everything is agreed’, what use is a Withdrawal Agreement if a Political Declaration does not follow and secure binding consent? There persists a risk that the UK might exit the EU without a deal, recast its relationship with the EU in terms of less favourable World Trade Organisation rules, and do the unthinkable, fall off the much feared cliff edge. Meanwhile, the Democratic Unionist Party in Northern Ireland continues to agitate for greater parity of treatment with the rest of the UK, whilst Scotland, London, and other countries and regions who voted Remain seek differentiation, special dispensations and opt out clauses. All the while, unless their concerns are heeded by the political class, the country's urban ‘left behinds’ increasingly display a proclivity towards regressive senses of place making and claiming and demarcating, inevitably sometimes through violent means, who has a right to belong in British cities and neighbourhoods.

In his book The Birth of Territory, Stuart Elden (Citation2013) argues that it is important to approach the idea of human territoriality conceptually and historically. For Elden human territorialization – understood as a ‘bundle of technologies’ used to stake a claim on a bounded territory – has been much longer in germination than Westphalia; key supporting concepts were developed from as early as the classic period (by the Greeks and Romans), evolved throughout the medieval dark ages and came to fruition in the West during the Renaissance and Age of Reason. Our third provocation then, is that Brexit constitutes an important chapter in the history of human territorialization in that it has proven midwife to a new ‘bundle of technologies’ centred upon state building after the era of the supra-national state, the difficulties of maintaining the territorial integrity of the state when the interests of nations and regions dislocate, and new bordering strategies and tactics in UK cities which house ethnic minority populations. There is a need to explore the forms of both hard power and soft power which are being deployed by and in the EU and the UK to create and discipline European and British political and cultural subjectivities, to claim space, to build real and imagined walls, and to invoke and defend turf (see Cassidy et al. in this collection). Brexit we might surmise, is both reproducing and developing historically new technes of spatial control and regulation (see Hayward, Wood and Gilmartin, and Anderson in this SI).

The Brexit debate is riddled with many of the maladies and inflictions which characterise our post-political and post-truth present. Rarely has the public square been perverted by such hostile thought policing and such a scale of tactical inaccuracies, exaggerations and partialities. This diminution in public discourse is playing itself out in the politics of the academy. Right critics, of course, lament the left-liberal capture of the university, the ‘closing of the American mind’ and the putative lack of tolerance and criticality within critical scholarship, embodied in the science wars, and the ‘Sokal’ and ‘grievance studies’ hoaxes. Informed by these critics, some prominent Leave campaigners have dismissed much academic research as little more than anti-Brexit propaganda. But equally, unquestionably, the corporate state which David Harvey foresaw in 1974 has mutated and deepened. Whether it be cast in terms of impact, civic engagement, useful learning, knowledge exchange, technology readiness levels, co-creation or more profoundly the enlargement of the intellect and ‘ennoblement’ of the citizenry, universities are once again placing under heightened scrutiny the reach of their research beyond the walls of the academy. This turn to impact has great potential; but it is also freighted with great risk. Left and left-liberal critics lament the imposition of anti-democratic neoliberal and neoconservative forces on scholarship and question whether the ascendance of neoliberal governmentalities and the academic entrepreneur and consequent reconfiguration and privatization of the heretofore public university have crushed the safe spaces so necessary if pursuit of truth is to prosper.

There has never been a more important moment to revive and reaffirm the importance of evidence-based public policy. This paves the way for our fourth provocation – that Brexit serves to heighten awareness of the intensified post-political and post-truth public realm which now imperils democracy and threatens to engulf the academy and has created space for a reaffirmation of rigorous evidence based public policy.

What does rigorous social science tell us about the likely impacts of Brexit? Of course, the uncertainties surrounding Brexit mean that we cannot say for sure what its likely impacts will be. There is simply too much contingency, even for contingency planning. But, in reality, there are precious few reasons to prefer optimism over pessimism. With few exceptions most social scientific economic impact assessments conclude that Brexit, whether ‘soft’ or ‘hard’, will depress and damage the UK economy and result in slower growth in the UKs’ city-regions than would otherwise be the case (Brakman et al., Citation2018; Pollard, Citation2018).

Six conclusions are garnering favour in the research community: first. Brexit is already impacting negatively on the UK economy (a claim affirmed periodically and surely by Governor of the Bank of England Mark Carney); second, Brexit is likely to depress the UK economy into the foreseeable future (Dhingra et al. Citation2016); third, the harder the Brexit the more damaging its effects will be (Greater London Authority, Citation2018); fourth, it will be difficult for good trade deals with other countries to mitigate losses incurred by reduced trade with the EU in the short and medium term (Colantone & Stanig, Citation2018; Dhingra, Ottaviano, Rappoport, Sampson, & Thomas, Citation2018); fifth, city-regions in the UK will be more impacted than those in the rest of the EU, with the exception of the Republic of Ireland (Chen et al., Citation2018; Lai & Pan, Citation2018; Lavery, McDaniel, & Schmid, Citation2018); sixth, Brexit will have different consequences for different UK city-regions (and also rural areas – see Maye in this collection, and social and demographic groups – see MacLeavy in this SI), ironically impacting most negatively those northern city-regions and rustbelt blue collar towns who voted for it (Di Cataldo, Citation2017; Dhingra, Machin, & Overman, Citation2017a; Dhingra, Ottaviano, & Sampson Dörry, Citation2017b; Greater London Authority Report, Citation2018; Hall & Wójcik, Citation2018; Los, McCann, Springford, & Thissen, Citation2017; McCann, Citation2018; North, Citation2017).

These problems have been magnified by the UK government's poor level of preparedness for Brexit. Even if a Political Declaration can be agreed and developed into a legal Treaty, it is unlikely that the British Civil Service will be in a position to implement any such Declaration given projected timelines (Owen, Rutter, & Lloyd, Citation2018). In every sense, Brexit risks failing what Tom Megs (Chief Executive of the Government's Infrastructure and Projects Authority) has called the ‘Valley of Death’ test – the gap between developing policy and putting it into practice. According to Megs, Brexit has succumbed to the six ‘sins of project failure’: lack of clarity around project objectives; lack of alignment among stakeholders, unclear governance and accountability, insufficient resources, whether people or money, inexperienced project leadership and; overambitious schedule and cost. The risks which attend to this lack of capacity to implement Brexit at the level of the national state are amplified by the general unpreparedness of business, big and small, regional and local government and the third sector.

And so this leads us to our fifth provocation; whilst there exists a vast array of conceptual and policy tools addressing risk, shock, resilience and how institutional capacity might be built to withstand disruption, these have been insufficiently applied and the UK appears to be generally unprepared to manage Brexit as a significant political hazard.

Gilbert White once famously declared ‘floods are caused by god, natural disasters by man’ (sic) (Hinshaw, Citation2006) an observation given expression in the equation R(isk) = H(azard) × V(ulnerability). In turn, vulnerability we might say comprises three component parts: susceptibility (degree of susceptibility to hazards or likelihood of suffering harm), coping (capacity to cope with hazards or capacity to mitigate the impact of hazards when they do occur), and adaptation (ability to plan ahead to adapt to natural extremes or ability to minimize the degree to which exposure to hazards is increased by prior poor human decision making). Social, economic, cultural, and political processes determine a society nation/region/community's degree of susceptibility, coping capacity, and ability to adapt – creating uneven geographies of vulnerability. From our analysis above, we understand Brexit at root to be a cri-de-coeur from left behind people, places and communities rendered redundant by globalization, deindustrialization and neoliberal policy and most recently a decade of austerity. Whilst tending to vote in favour of Brexit, we also understand that these places suffer from greater susceptibility (likelihood of suffering harm), weaker coping capacities (are less able to withstand the shock), and weaker adaptation capacities (ability to put in place Brexit mitigation strategies). And so we ask, how might these places deal better with Brexit risks which in some cases they have brought upon themselves?

In his 2011 Adaptation to Climate Change: From Resilience to Transformation British geographer Mark Pelling cautions against promoting resilience as always and everywhere the goal of disaster management (Pelling, Citation2011). Pelling calls for more attention to be given to the ways in which hazards play into the politics that prevail in countries. He deploys the term ‘disaster politics’ to refer to the ways in which hazards interact with the existing political order, consolidating, destabilizing, and transforming this order in different circumstances. Societies that frame comprehensive disaster management in terms of the pursuit of greater resilience need to recognize that in so doing they are making a political choice about the kind of future they want. Thinking in terms of resilience implies prioritizing bounce-back (to return to the status quo). In fact, disasters provide opportunities to bounce forward (to establish a new and better equilibrium state). According to Pelling, natural hazards can lead to ‘resilience,’ but also there can be ‘transition’ (institutional evolution and strengthening) and ‘transformation’ (institutional deep reform) outcomes.

The new UK2070 Commission independent inquiry into city and regional inequalities in the UK hints at what is required if transition and transformation are to buffer regions against Brexit's worst effects. At one level, English devolution, the establishment of new city regions, the election of metro-mayors and further waves of city-deals which transfer meaningful powers and resources to local polities constitute an encouraging response. The UK remains one of the most centralized states in Europe, to a fault. But Brexit has arrested and occupied the attention of the UK state to the degree that devolution appears to have slowed if not stalled (or, from the perspective of the devolved nations, is a development that can for now be ignored). There exists a need to further build a political coalition in favour of devolved responsibility; in this Northern Ireland, Scotland, Wales, Greater London, and wider groupings such as the Northern Powerhouse have a vital role to play. But still, it is likely that the UK government will continue to preside over most of the state's budget. There will be a need for more spatially sensitive national policies. Is there room for a national spatial strategy? What will become of the Shared Prosperity Fund, the UKs answer to forgone EU Structure Funds? Despite protestations to be ‘place conscious’, will the UKs emerging Industrial Strategy and Infastructure Strategy support balanced regional development?

Conclusion

An orphan of the rise and reign of the West, it is only to be expected that in its concepts, methods, foci, and practices, human geography (at least as practiced in the UK and in continental Europe) will bear the imprint of the faltering of western imperial prowess, globalization, the affliction of uneven geographical development and socio-spatial inequalities, more polarized and polarizing politics, rising populist and nationalist movements, and a more inhospitable climate for those deemed ‘other’ and ‘foreign’. Brexit constitutes a particularly consequential expression of these processes as they combine into a perfect storm. In this Introduction to the SI, we have argued that a completing/completed Brexit may in the end deposit in its wake a tradition of Brexit Geographies and etch itself in the stratigraphic record of Anglo-European geographic thought, particularly political geographical thought. We have argued that Brexit presents as an anomalous protrusion in at least five key domains of geographical inquiry. We have developed five provocations, which can be summarized, along with key questions which they prompt, thus:

Brexit and Remain are at once both elite and populist political projects complicating critical policy studies’ ambition to speak truth to power. What is critical policy studies to do in an age of populism and with public policies such as Brexit?

Brexit is steeped in a lament on the demise of the British empire, melancholy and neurosis over the loss of halcyon days of yesteryear, when Brittania ruled the waves, and a penchant for nostalgia and enthusiasm to reanimate colonial mentalities and as such sits in productive tension with the postcolonial project of decolonizing geography. In what ways does Brexit furnish Postcolonial Geography with new urgency and purpose?

Construing human territorialization as historical and processual, Brexit can be understood as a further progenitor of new governing ‘technologies’ which enable old/established and novel/fresh claims to be made on space and territory. In what ways has Brexit reinforced and/or innovated particular technes of spatial control in the governmental machine of the west, and fostered new kinds of deterritorialising and reterritorializing strategies?

At a time when the public sphere is being cleansed of genuine agonistic debate and truth is in question, Brexit is at once a benefactor of and source of encouragement for our increasingly post-political and post-truth public age; but it is also a catalyst for renewed interest in evidence-based public policy, rigorous policy testing and evaluation and the application of objective data. In the present climate, how might geographers conduct rigorous evidence based assessments of the efficacy of public policies?

At a time when scholars of hazards are developing sophisticated understandings of disasters, risk, and resilience, Brexit has been accompanied by a curious failure to prepare and to plan. If Risk = Exposure (Brexit, whether soft or hard)×Vulnerability (regional susceptibility, coping capacity, adaptation strategies), who is most at risk from Brexit, where, why, and what might be done about it?

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes on contributors

Mark Boyle is Chair of Urban Studies and Director of the Heseltine Institute for Public Policy, Practice and Place at the University of Liverpool. His research examines public policy, cities, postcolonial scholarship and the history of geographic thought.

Ronan Paddison is Professor Emeritus in the School of Geographical and Earth Sciences at the University of Glasgow. His research interests are in political and urban geography.

Peter Shirlow is a Professor and Director at the University of Liverpool's Institute of Irish Studies. He has undertaken conflict transformation work in Northern Ireland and has used that knowledge in exchanges with governments, former combatants and NGOs in the former Yugoslavia, Moldova, Bahrain and Iraq.

ORCID

Mark Boyle http://orcid.org/0000-0002-9882-3907

Ronan Paddison http://orcid.org/0000-0002-4268-1487

Peter Shirlow http://orcid.org/0000-0002-7483-9859

References

- Anderson, B., & Wilson, H. F. (2018). Everyday Brexits. Area, 50(2), 291–295. doi: 10.1111/area.12385

- Anthony, G. (2017). Brexit and the Irish border: Legal and political questions. Dublin: Royal Irish Academy/British Academy Briefing.

- Bachmann, V., & Sidaway, J. D. (2016). Brexit geopolitics. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences, 77, 47–50.

- Becker, S. O., Fetzer, T., & Novy, D. (2017). Who voted for Brexit? A comprehensive district-level analysis. Economic Policy, 32(92), 601–650. doi: 10.1093/epolic/eix012

- Benson, M., Collins, K., & O’Reilly, K. (2018). What does Brexit mean for UK citizens living in the EU27? Talking about the citizens’ rights agreements with UK citizens across the EU27. London: Goldsmith.

- Brakman, S., Garretsen, H., & Kohl, T. (2018). Consequences of Brexit and options for a ‘global Britain’. Papers in Regional Science, 97(1), 55–72. doi: 10.1111/pirs.12343

- Bromley-Davenport, H., MacLeavy, J., & Manley, D. (2018). Brexit in Sunderland: The production of difference and division in the UK referendum on European Union membership. Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space. doi: 10.1177/0263774X18804225

- Burnett, J. (2017). Racial violence and the Brexit state. Race & Class, 58(4), 85–97. doi: 10.1177/0306396816686283

- Calhoun, C. (2016). Brexit is a mutiny against the cosmopolitan elite. New Perspectives Quarterly, 33(3), 50–58.

- Chen, W., Los, B., McCann, P., Ortega-Argilés, R., Thissen, M., & van Oort, F. (2018). The continental divide? Economic exposure to Brexit in regions and countries on both sides of The Channel. Papers in Regional Science, 97(1), 25–54. doi: 10.1111/pirs.12334

- Colantone, I., & Stanig, P. (2018). Global competition and Brexit. American Political Science Review, 112(2), 201–218. doi: 10.1017/S0003055417000685

- Coppock, J. T. (1974). Geography and public policy: Challenges, opportunities and implications. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 63, 1–16. doi: 10.2307/621525

- Dhingra, S., Machin, S., & Overman, H. (2017a). Local economic effects of Brexit. National Institute Economic Review, 242(1), R24–R36. doi: 10.1177/002795011724200112

- Dhingra, S., Ottaviano, G., Rappoport, V., Sampson, T., & Thomas, C. (2018). UK trade and FDI: A post-Brexit perspective. Papers in Regional Science, 97(1), 9–24. doi: 10.1111/pirs.12345

- Dhingra, S., Ottaviano, G., & Sampson, T. (2017b). A hitch-hiker’s guide to post-Brexit trade negotiations: Options and principles. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 33, S22–S30. doi: 10.1093/oxrep/grx005

- Dhingra, S., Ottaviano, G. I., Sampson, T., & Reenen, J. V. (2016). The consequences of Brexit for UK trade and living standards. LSE Occasional Papers, LSE.

- Di Cataldo, M. (2017). The impact of EU objective 1 funds on regional development: Evidence from the UK and the prospect of Brexit. Journal of Regional Science, 57(5), 814–839. doi: 10.1111/jors.12337

- Di Cataldo, M., & Monastiriotis, V. (2018). An assessment of EU Cohesion policy in the UK regions: Direct effects and the dividend of targeting (LEQS Paper No. 135/2018). Brussels: LEQS.

- Doherty, M. (2016). Through the looking glass: Brexit, free movement and the future. King’s Law Journal, 27(3), 375–386. doi: 10.1080/09615768.2016.1250463

- Dorling, D. (2016). Brexit: The decision of a divided country. BMJ, 354.

- Dorling, D., & Tomlinson, S. (2018). Rule Britannia: BREXIT and the End of empire. London: Biteback.

- Dörry, S. (2017). The geo-politics of Brexit, the euro and the City of London. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences, 85, 1–4.

- Dougan, M. (Ed.). (2017). The UK after Brexit: Legal and policy challenges. Cambridge: Intersentia.

- Dougan, M. (2018). The institutional consequences of a bespoke agreement with the UK based on a ‘close co-operation’ model. Brussels: European Parliament’s Policy Department for Citizen’s Rights and Constitutional Affairs.

- Elden, S. (2013). The Birth of territory. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Ford, R., & Goodwin, M. (2017). Britain after Brexit: A nation divided. Journal of Democracy, 28(1), 17–30. doi: 10.1353/jod.2017.0002

- Gilmartin, M., Wood, P., & O’Callaghan, C. (2018). Borders, mobility and belonging in the era of Brexit and Trump. Bristol: Policy Press.

- Goodhart, D. (2017). The road to Somewhere: The populist revolt and the future of politics. London: Hurst and Co.

- Goodwin, M., & Milazzo, C. (2017). Taking back control? Investigating the role of immigration in the 2016 vote for Brexit. The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 19(3), 450–464. doi: 10.1177/1369148117710799

- Goodwin, M. J., & Heath, O. (2016). The 2016 referendum, Brexit and the left behind: An aggregate-level analysis of the result. The Political Quarterly, 87(3), 323–332. doi: 10.1111/1467-923X.12285

- Gordon, I. R. (2018). In what sense left behind by globalisation? Looking for a less reductionist geography of the populist surge in Europe. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 11(1), 95–113. doi: 10.1093/cjres/rsx028

- Greater London Authority. (2018). Preparing for Brexit. London: Author.

- Hall, S., & Wójcik, D. (2018). ‘Ground Zero’of Brexit: London as an international financial centre. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2018.02.002

- Harvey, D. (1974). What kind of geography for what kind of policy? Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 63, 18–24. doi: 10.2307/621527

- Harvey, D. (1984). On the history and present condition of geography: An historical materialist manifesto. The Professional Geographer, 36, 1–11. doi: 10.1111/j.0033-0124.1984.00001.x

- Harvey, D. (1989). The condition of Postmodernity. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Hayward, K., & Murphy, M. C. (2018). The EU’s influence on the peace process and agreement in Northern Ireland in light of Brexit. Ethnopolitics, 17, 1–16. doi: 10.1080/17449057.2018.1472426

- Hazeldine, T. (2017). The revolt of the rustbelt. New Left Review, 105, 51–79.

- Higgins, K. W. (2018). National belonging post-referendum: Britons living in other EU member states respond to “Brexit”. Area. doi: 10.1111/area.12472

- Hinshaw, R. E. (2006). Living with nature’s extremes: The life of Gilbert Fowler White. New York: Johnson Books.

- Hobolt, S. B. (2016). The Brexit vote: A divided nation, a divided continent. Journal of European Public Policy, 23(9), 1259–1277. doi: 10.1080/13501763.2016.1225785

- Jensen, M. D., & Snaith, H. (2016). When politics prevails: The political economy of a Brexit. Journal of European Public Policy, 23(9), 1302–1310. doi: 10.1080/13501763.2016.1174531

- Jessop, B. (2017). The organic crisis of the British state: Putting Brexit in its place. Globalizations, 14(1), 133–141. doi: 10.1080/14747731.2016.1228783

- Jessop, B. (2018). Neoliberalization, uneven development, and Brexit: Further reflections on the organic crisis of the British state and society. European Planning Studies, 26(9), 1728–1746. doi: 10.1080/09654313.2018.1501469

- Lai, K. P., & Pan, F. (2018). Brexit and shifting geographies of financial centres in Asia. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2018.02.004

- Lavery, S., McDaniel, S., & Schmid, D. (2018). New geographies of European financial competition? Frankfurt, Paris and the political economy of Brexit. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2018.03.021

- Lee, N., Morris, K., & Kemeny, T. (2018). Immobility and the Brexit vote. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 11(1), 143–163. doi: 10.1093/cjres/rsx027

- Leslie, P. A., & Arı, B. (2018). Could rainfall have swung the result of the Brexit referendum? Political Geography, 65, 134–142. doi: 10.1016/j.polgeo.2018.05.009

- Livingstone, D. N. (1992). The geographical tradition: Episodes in the history of a contested enterprise. Chichester: John Wiley and Sons.

- Los, B., McCann, P., Springford, J., & Thissen, M. (2017). The mismatch between local voting and the local economic consequences of Brexit. Regional Studies, 51(5), 786–799. doi: 10.1080/00343404.2017.1287350

- Lulle, A., Moroşanu, L., & King, R. (2018). And then came Brexit: Experiences and future plans of young EU migrants in the London region. Population, Space and Place, 24(1), e2122. doi: 10.1002/psp.2122

- Manley, D., Jones, K., & Johnston, R. (2017). The geography of Brexit–what geography? Modelling and predicting the outcome across 380 local authorities. Local Economy, 32(3), 183–203. doi: 10.1177/0269094217705248

- McCann, P. (2018). The trade, geography and regional implications of Brexit. Papers in Regional Science, 97(1), 3–8. doi: 10.1111/pirs.12352

- Miller, R. G. (2018). (Un)settling home during the Brexit process. Population, Space and Place, e2203. doi: 10.1002/psp.2203

- North, P. (2017). Local economies of Brexit. Local Economy, 32(3), 204–218. doi: 10.1177/0269094217705818

- Owen, J., Rutter, J., & Lloyd, L. (2018). Preparing Brexit: How ready is Whitehall. Institute for Government, Retrieved from www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publications/preparing-brexit-how-ready-whitehall

- Paddison, R., & Rae, N. (2017). Brexit and Scotland: Towards a political geography perspective. Social Space, 13, 1–18.

- Pelling, M. (2011). Adaptation to climate Change. London: Routledge.

- Picketty, T. (2013). Capital in the twenty first century. Boston: Harvard University Press.

- Picker, G., Murji, K., & Boatcă, M. (2019). Racial urbanities: Towards a global cartography. Social Identities, 25, 1–10. doi: 10.1080/13504630.2017.1418606

- Pollard, J. S. (2018). Brexit and the wider UK economy. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2018.02.005

- Zhang, A. (2018). New findings on key factors influencing the UK’s referendum on leaving the EU. World Development, 102, 304–314. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2017.07.017