ABSTRACT

This article introduces three small, European stateless nations that – invigorated by pervasive metropolitanisation phenomena – are increasingly shaping calls for devolution: Catalonia, the Basque Country and Scotland. These three nations are re-scaling their respective nation-states (Spain and the UK) in different ways: (i) being bolstered by their metropolitan hubs (Barcelona, Bilbao, and Glasgow) and (ii) generating a stateless ‘civic nationalism’ rooted in the metropolitan ‘right to decide’. Oppositional response to this ‘civic nationalism’ has re-emerged as state-centric ‘ethnic nationalism’. This article concludes that gaining or lacking metropolitan support for the ‘right to decide’ will establish the future directions of devolution debates.

Introduction: re-scaling the nation-state through metropolitanisation

Just as the world has continuously urbanized over the last several decades, it has also rapidly metropolitanised (Brenner, Citation2003; Sellers & Walks, Citation2013) by reinforcing the re-scaling of nation-states through multiple interconnected factors. In Europe, the aftermath of the referendum on Scottish independence (Calzada, Citation2014) and the UK's continued membership in the EU (Brexit) (Johnston, Manley, Pattie, & Jones, Citation2018; MacLeod & Jones, Citation2018; Rodríguez-Posé, Citation2018), as well as the political struggle in Catalonia and the resulting territorial crisis in Spain (Rodon & Guinjoan, Citation2018), are key to examining how pervasive metropolitanisation phenomena have recently triggered wider devolution debates regarding the organization and legitimation of nation-state power institutionally and territorially as well as politically and democratically (Jessop, Citation1990).

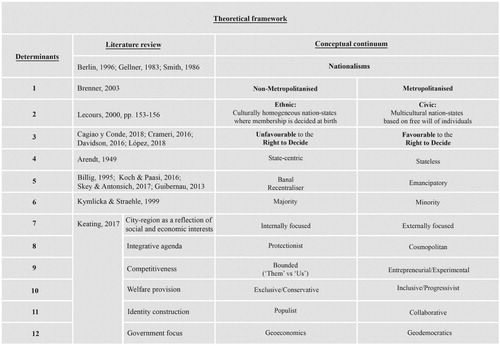

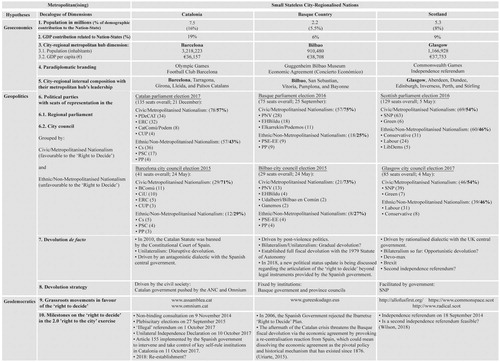

To introduce how metropolitanisation phenomena are increasingly shaping calls for devolution, this article focuses on three small European, stateless, city-regionalised nations (Ehrlich, Citation1997; Hepburn, Citation2008): Catalonia, the Basque Country, and Scotland. In these cases, the nations are re-scaling their respective nation-states (Spain and the UK), fuelled by a ‘civic nationalism’ rooted in the metropolitan ‘right to decide’ (as an updated version of the ‘right to the city’ principle) and bolstered by their metropolitan hubs (Barcelona, Bilbao, and Glasgow). However, (i) the interplay among political parties and (ii) the parties’ positions regarding the ‘right to decide’ differ considerably in each case ( and ). As a counterargument to the previous trend – and in opposition to exercising the ‘right to decide’ through referendum or consultation by defending a fixed state-territorial uniformity – state-centric ‘ethnic nationalistic’ expressions with different rationales have recently (re)emerged in Spain and the UK ().

Figure 1. Theoretical framework: Non-metropolitanised (ethnic) and metropolitanised (civic) nationalisms through the unfavourable/favourable positions regarding the ‘right to decide’.

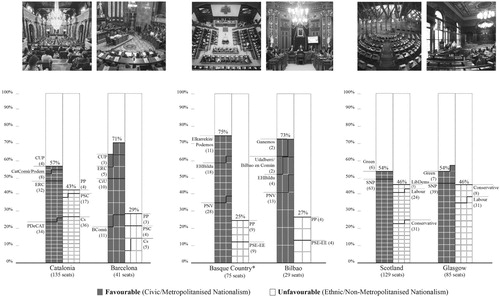

Given the timely literature on these three case studies (Cetrà & Harvey, Citation2018; Mulle & Serrano, Citation2018; Rodon & Guinjoan, Citation2018), the research question posed in this article addresses how the metropolitan phenomena in each case uniquely interact with calls for devolution while also updating our understanding of the classical division between civic and ethnic nationalism in the UK and Spain (Berlin, Citation1979; Guibernau, Citation2013; Lecours, Citation2000). Thus, this article attempts to answer the research question by exploring two main ideas: (i) metropolitanisation phenomena are responsible for invigorating the claim of the ‘right to decide’ in these three city-regionalised nations due to the official growing support being manifested through regional and city council parliamentary elections as well as the crowded grassroots demonstrations regularly occurring in Barcelona, Bilbao, and Glasgow (); and (ii) this claim challenges our perceptions and interpretations of both civic and ethnic nationalism (Lecours, Citation2000) (). Consequently, in the early contours of this article, the ‘right to decide’ is defined as the ‘right by members of the nation to defend and exercise, through referenda or consultation, their right to be recognised as a demos able to decide upon their political destiny triggered by their desire to share a common fate’ (Guibernau, Citation2013, p. 411).

Figure 2. Three small European stateless city-regionalised nations according to the three metropolitan hypotheses, presented through a decalogue of dimensions. Source: OECD, EUROSTAT and EUSTAT.

Paralleling intertwined debates on devolution through the ‘right to decide’, pervasive divides have been revealed to exist under the surface of the discursive homogeneity of democratic representation in nation-states, including the divide between (i) the ‘metropolitan’ and the ‘non-metropolitan’ (Becker, Fetzer, & Novy, Citation2016; Mulligan, Citation2013) and recently between (ii) the ‘stateless city-regionalised’ and the ‘state-centric’. Regarding the ‘metropolitan’ divide, to an extent, the Brexit referendum and growing support for populist candidates have clarified that the most potent divisions exist between the so-called ‘metropolitan elite’ and the more peripheral (provincial), rural ‘rest’ – i.e. places that ‘don't matter’ (Rodríguez-Posé, Citation2018). The ‘national’ divide may be viewed as the outcome of the perceived unevenness with which certain city-regions ‘have a stake’ in political decisions regarding nation-state development; in turn, the divide shapes those perceptions of difference when small stateless nations in Europe claim the ‘right to decide’ about their own futures. Through the connection between the ‘metropolitan’ and the ‘national’ divides analyzed in the three cases in the fourth section, this article reveals that civic nationalism can be interpreted as an emerging structural response that blends devolution claims, metropolitan inclusiveness as a social value, and a politically and socially progressivist agenda; this is shown by the programmes of the civic nationalist political parties and the rhetoric of the grassroots movements in each case () (Gillespie, Citation2016; Massetti, Citation2018; Sage, Citation2014).

As a result, in its third section, this article suggests three hypotheses that may currently be determining those ‘metropolitan’ and ‘national’ divides: (i) socio-economics (geoeconomic hypothesis), (ii) identity and sense of belonging to a stateless nation (geopolitical hypothesis), and (iii) democratic demand for the ‘right to decide’ (geodemocratic hypothesis) (). To a point, such hypotheses might indicate a shift in the fixed territorial interpretation of national politics due to a wide range of preferences for territorial decentralization. Accordingly, self-government and devolution accommodation regimes provided by nation-states to city-regions continue to be perceived as insufficient by civic nationalist movements, resulting in further tensions among territorial statehood, spaces of historical identity, and future secessionist aspirations (Mulle & Serrano, Citation2018). One means by which nation-states can address this tension is to seek outright independence to reconcile small nations’ spaces of identity and statehood through referenda, as occurred in Scotland in 2014 (Sanghera, Botterill, Hopkins, & Arshad, Citation2018). However, Cetrà and Harvey (Citation2018, p. 1) predict that ‘independence referendums will continue to be rare events’ (Qvortrup, Citation2014). Conservatives in the UK have recently adopted a more restrictive position on the ‘right to decide’, and unfavourable conditions for the ‘right to decide’ will likely remain in Spain despite attempts by the newly appointed government led by the Social-Democrats (Partido Socialista Obrero Español, PSOE) to unravel plurinational and federal dilemmas.

Such hindrances raise major questions about basic democratic principles that are based on the ‘right to decide’ and the provision of egality of representation in the tripartite combination of citizenship, government, and existing nation-states such as the UK and Spain (Cagiao y Conde & Ferraiuolo, Citation2016; Crameri, Citation2016; Davidson, Citation2016; López, Citation2018). However, the UK and Spain provide very diverse political contexts that are embedded in different conceptions of the nation-state and constitutional designs; these conceptions are primarily mononational in Spain and primarily plurinational in the UK, but they are multiple and contested in both cases. The four constituent nations of the UK exhibited centrally orchestrated regional devolution in 1997 under the new Labour government. Since the Franco years in Spain, the central government has continuously insisted on re-centralization to resist efforts promoting a devolved allocation of powers, as observed in the intervention into Catalan autonomy via the state control of Catalan institutions – a response to the ‘illegal referendum’ that occurred on 1 October 2017; that ‘referendum’ was a clear turning point in the acceleration of this confrontation (Cetrà & Harvey, Citation2018; Cetrà, Casanas-Adam, & Tàrrega, Citation2018). Since then, that confrontation has provoked the (re)emergence of a state-centric banal (and majority) nationalism characterized by responding through the recentralisation of hegemonic ethnic patterns (Bieber, Citation2018).

This article is structured as follows. The next section examines the (re)emergence of two opposing versions of nationalism – stateless civic nationalism and state-centric ethnic nationalism as a response to the former – in the UK and in Spain through a theoretical framework. The third section presents the three aforementioned hypotheses of civic nationalism in detail; the fourth section analyses the three cases. The final section concludes that the metropolitan-driven demand for the ‘right to decide’ may provoke and determine new unique waves and scenarios regarding devolution debates in each case. However, a heterogenous ‘transformative alliance’ around civic nationalist patterns will likely continue gathering a wide range of ‘progressivist’ political parties, social movements, and civic groups rooted in the metropolitan realm. These entities are likely to be self-organised in a novel communitarian amalgamation, creating deep fissures in the contemporary nation-states of Spain and the UK. Therefore, for all intents and purposes, this article attempts to prescribe no certain outcome that resulted in the metropolitan playground for the three analyzed cases. Instead, this article targets reflecting subtle – and sometimes less visible – ongoing trends in the devolution debate that are not generalizable and do not ignore patterns that could transcend particular cases.

Theoretical framework: the emergence of ‘civic/metropolitanised nationalism’ in small stateless city-regionalised nations

In 1979, Berlin noted that ‘nationalism seems the strongest force in the world’ (p. 349). However, he also anticipated the potential link between civic nationalism and the emancipatory role of cities through the claims of the ‘right to decide’, stating ‘nationalism springs, as often as not, from a wounded or outraged sense of human dignity, the desire for recognition’ (Citation1996, p. 252). In 2000, Lecours elucidated that ‘the distinction between ethnic and civic nationalism is firmly rooted in a conception of development that rests on the dichotomy between traditional and modern societies’ (p. 153). However, he also acknowledged significant criticisms of the ethnic–civic distinction due to its Manichean character (Brown, Citation1999). In response to this observation, this article has re-conceptualised the ethnic and civic categories of nationalism as ideal-types at two ends of a continuum with the ‘right to decide’ as the determinant, as most nationalist movements are not purely ethnic or purely civic. Despite these criticisms, the ethnic–civic distinction is widely used and is considered a useful analytical tool, but accepting it as a theoretical framework may remain problematic (Maxwell, Citation2018). Far from rejecting this distinction, this article attempts to foster a discussion that should lead to further research that will improve theoretical frameworks and analytical tools; such research should lead to better empirical examinations of the emergent and timely correlation among metropolitanisation, the ‘right to decide’, devolution, and the types of nationalism.

Thus, two opposing versions of nationalism have (re)emerged alongside the aforementioned metropolitanisation phenomena in recent years: (i) an ethnically based, non-metropolitanised, state-centric, exclusive, and right-wing populist nationalism, also known as ‘Banal Nationalism’ (Billig, Citation1995; Koch & Paasi, Citation2016), and (ii) a civic, more inclusive, metropolitan-based stateless nationalism that embraces ethnic diversity and articulates a more progressivist and emancipatory social democratic nationalism. Thus, the presence of a more inclusive and metropolitan-influenced image of ‘nation’ and belonging differentiates both types of nationalism. In accordance with a recent analysis (Keating, Citation2017), this article argues that a divide may emerge between these two conceptualisations of nationalism in Europe (see ), ethnic vs civic, with civicness acting as an integrationist mechanism. Civic/metropolitanised nationalism flourishes by merging the agendas of emancipatory nationalism with urban and metropolitan interests and civicness, as evidenced by devolution being articulated and operationalized as a political agenda (Mulle & Serrano, Citation2018).

Nationalism can be very divisive, as demonstrated by ethnic nationalism. This divisiveness can be illustrated by the discourse propagated in the UK by the UK Independence Party (UKIP). That discourse uses European continental citizens in the UK as explicit ‘others’. Such divisiveness in Spain can (possibly) also be perceived not only in the discourse of the Citizens’ Party (Ciudadanos, the Cs) but also more explicitly in the new emerging far-right Vox Party's recent events in the southern region of Andalusia. Both parties oppose Catalan independence and reinforce Spanish territorial integrity by ‘seeing only Spanish nationals’ and treating Catalonia as another standard Spanish region being subtly re-centralised by the central government. On the other hand, civic nationalism, as a metropolitan updated version of the ‘right to the city’, appeals to universal values such as freedom and equality that underpin the ‘right to decide’ one's own future. This attitude is rooted in a long history of cities’ political empowerment and in the rights of their citizens (Arendt, Citation1949; Purcell, Citation2013). The distinction of a civic, metropolitanised nationalism suggests that now may be the time to adapt the specific expression ‘metropolitanised nationalism’ to the right to self-determination claimed by small stateless city-regionalised nations that possess strong and dominant metropolitan centres in Europe with leading international connections. In contrast, ethnic nationalism appears as an aggressively exclusive and nostalgic narrative drawing on racism or (reinterpreted) historic precedence to set one nation apart from others. The UKIP and the Cs argue for maintaining or even reinforcing the territorial integrity of their existing states in the UK and Spain; their rhetoric fundamentally advocates state-national uniformity and thus internal cultural homogeneity within the state. This phenomenon is remarkable for the Basque Country, as the Cs – with no political representation in the regional parliament thus far – have been constantly attacking the economic agreement with the nation-state (concierto económico; Uriarte, Citation2015); this is the broadly supported pillar of devolution in the city-region. However, while the UKIP vehemently seeks to set England (and the entire UK) apart from the rest of the EU, the Cs reinforces its state-centric position by advocating for the re-centralization of the entire Spanish nation-state.

In the UK, it can be assumed that one's political decisions are based on one's metropolitan circumstances. Research findings on the Brexit vote have revealed that ‘Brexiters’ have similar ‘age and education profiles as well as the historical importance of manufacturing employment, low income and high unemployment’ (Becker et al., Citation2016, p. 1). The profile of ‘Brexiters’ resonates with the non-metropolitan conditions of these ‘left behind’ voters, a situation that has resulted in a growing sense of disempowerment and alienation among those who are not ‘part of the system’. For a large portion of this population, the Brexit vote became a proxy for their sense of political detachment from the political establishment (the ‘elite’) as well as for underlying societal, economic, and geographic divisions; only after the vote did many people actually engage with the facts regarding leaving the EU instead of focusing on populist claims regarding EU membership (Patberg, Citation2018). The Brexit issue illustrates that identities and related political agendas are no longer being expressed in territorially homogeneous units demarcated by boundaries or borders (Beel, Jones, & Jones, Citation2018; MacLeod & Jones, Citation2018). Instead, identities – and thus, perceptions of belonging – develop a more explicit metropolitan versus non-metropolitan dichotomy, and both groups hold different views of the world, especially the threats/benefits of globalization. While the metropolitan perspective (civic nationalism) more readily sees opportunities for inclusiveness and considers a broader notion of identity as a multi-scalar construct, the non-metropolitan view (ethnic nationalism) examines the threats and uncertainties of metropolitan areas, perceiving the metropolitan population as part of the threat (Winlow, Hall, & Treadwell, Citation2017).

In Spain, the path out of the current Catalan crisis, namely, the state-to-nation identity nexus threatening the very integrity of the nation-state, appears to be less clear (Serrano, Citation2013). This crisis is rooted in the difficulty confronting the state-centric Spanish political vision as it attempts to democratically accommodate quests for greater self-determination to prevent potential challenges to the existing integrity of statehood. However, this lack of accommodation has resulted in just that: an increasingly more confrontational and centrifugal dynamic that undermines the very state that is supposed to be protected by the constitutional status quo.

Hence, in the aftermath of the Catalan crisis in Spain, certain state-centric political parties, such as the UKIP in the UK as well as the Cs, Vox, and the former Spanish ruling party, the Popular Party (Partido Popular, PP), have utilized this sense of disconnect and turned it into populist – often conservative – discourses and agendas. This type of discourse advocates a fixed state-territorial uniformity that can be presented as an effectively sacred legal arrangement, as in the current case in Spain.

Against the backdrop of these contexts, the emergence of civic/metropolitanised nationalism may be explained through three intertwined processes. These processes stem from the same nature of the role of metropolitanisation, occurring in parallel – though in a unique fashion as shown in – in the three analyzed city-regions:

a growing urban/metropolitan awareness of and assertiveness in pursuing self-interests;

an awakening of more explicit regional identities defined around particular civic characteristics, especially where distinct historical and/or cultural identities (nationhood) exist, resulting in a push to define and pursue self-interest more explicitly within an existing nation-state system; and

a new metropolitanised city-regional identity based on the combination of processes i and ii. In cases where processes 1 and 2 combine, the metropolitan and (small) national imaginations, discourses, and political devolution agendas may overlap, intertwine, and fuse through the metropolitan lens into an image of nationhood. This image of nationhood may be based on identity, the perception of belonging, an active claim to civilian rights, and an explicit strategy for becoming an international actor with its own voice in the EU.

Hence, in the three analyzed cases in this paper, the role of metropolitanisation is embodied through the intersection of the three processes explained above by allowing Barcelona, Bilbao, and Glasgow to accomplish three leading political functions in their particular city-regional realm: first, to strategise strong external outreach through the city-region's international connections; second, to articulate a tailored city-regional internal composition with their aforementioned metropolitan hubs’ leadership (5th dimension in ); and ultimately, to spark devolution debates by provoking controversies and tensions in the metropolitan playground among those in favour and in opposition to the ‘right to decide’ ().

Figure 3. Favourable/unfavourable proportion (%) regarding the exercise of the ‘right to decide’ via seats of representation in the regional governments and city councils (MPs) of the three European small stateless city-regionalised nations. (Elaborated by the author from electoral summaries).

These processes are evident in the three small stateless city-regionalised nations where urban values merge with a nationalistic discourse of citizenship, community, identity, and political autonomy. As nation-states might no longer be able to manage the increasing complexity of their cities and regions in the pursuit of cohesion, stateless small city-regionalised nations have sought to develop greater independence and a stronger presence on the global stage through their internationally visible (and engaged) city-regions (Calzada, Citation2015). The on-going evolution of strategies among stateless nationalist parties highlights an increasing presence and prevalence of city-ness and a metropolitan-driven approach to their policies (Massetti & Schakel, Citation2017) (). Fundamentally, these parties have found it more relevant to base their aspirations on merging democratic and civic arguments with culturally and historically unique identities that extend out in a broader European political sense (Massetti, Citation2018). However, this approach contrasts with populist right-wing protectionist choices, suggesting the co-existence of diverse nationalistic approaches. For instance, Keating (Citation2005) has extensively researched nationalistic responses to devolution in the UK, concluding that ‘Scotland is more committed than England to the traditional public sector model, emphasizing egalitarianism and cooperation with the public service professionals. This contrasts with the English emphasis on consumer choice and competition’ (p. 453).

Thus, civic/metropolitanised nationalism appears to be a novel and currently emerging paradigm, as these new, peaceful democratic movements represent the ‘right to decide’ within the democratic framework constructed by the EU. As this article attempts to illustrate, these phenomena suggest another potential interpretation of a civic nationalistic perspective, one that argues that metropolitan city-regions actually breed civic nationalism. Thus, the small stateless city-regionalised nations presented here are defined as internally structured and externally projected geopolitical networks capable of conforming to nation-state dynamics. These metropolitanisation phenomena paradoxically go hand-in-hand with the international growth of metropolitan economic dominance and with the increasingly loud political voices advocating small stateless city-regionalised nations. Metropolitan hubs seek more power to decide on their own policies, thus triggering strong support for devolution and the ‘right to decide’ and inevitably re-scaling and transforming – not eroding – nation-states (Brenner, Citation2003).

This article does not deny that the literature often argues that cities are global and cosmopolitan with no linkage to nationalisms. However, the article does argue that civic/metropolitanised nationalism certainly connects with the concept of ‘cosmopolitan nationalism’ because, from a normative perspective, Guibernau (Citation2013, p. 413) envisions civic, metropolitanised, and emancipatory nationalism as a tool with which to construct an urban democratic society that defends social justice, deliberative democracy, and individual freedom in Europe. This perspective contrasts with that of non-democratic and manipulative forms of nationalism related to populists ‘over splitting popular sovereignty’, as some authors have previously examined (Cagiao y Conde, Citation2018; Kymlicka & Straehle, Citation1999; Patberg, Citation2018). As recently confirmed by a BBC survey conducted by Curtice (Citation2018), ‘What nationalism means in England and Scotland differ considerably’. Thus, it is important to distinguish between nationalism in terms of the ethnic nationalist arguments presented by UKIP and civic nationalist claims by the Scottish National Party (SNP; Sage, Citation2014) in the UK. The same state-centric and ethnic identification could be established in Spain based on the winner (in votes) of the 2017 regional elections in Catalonia, the Cs, and the former ruling party in Spain, the PP (Convery & Lundberg, Citation2017). Objectively, both embrace recentralisation and a liberal agenda while also being extremely confrontational towards the Catalan civic nationalist movement – an approach that intensified after 1 October 2017 – even when they represent the minority block (Cetrà et al., Citation2018). It should be noted that this anti-‘right to decide’ block (Cs, the PP, and the PSC) presently represents 43% and 29% of the regional parliaments of Catalonia and the city council of Barcelona, respectively ().

Thus, in Spain and the UK, the following political parties officially advocate the ‘right to decide’: (i) in Catalonia, the Republican Left of Catalonia (Esquerra Republicana de Catalunya, ERC), the Catalan European Democratic Party (Partit Demòcrata Europeu Català, PDeCAT) and the Popular Unity Candidacy (Candidatura d’Unitat Popular, CUP); (ii) in the Basque Country, Basque Country United (Euskal Herria Bildu, EH Bildu) and the Basque Nationalist Party (Partido Nacionalista Vasco, PNV); and (iii) in Scotland, post-Brexit negotiations and the UK Prime Minister's statement that ‘now is not the time for a second independence referendum’ made it clear that the SNP and the Green party might be the only two parties advocating for the ‘right to decide’ and chasing a second independence referendum ( and ).

Consequently, this article has made the difficult methodological decision to classify the political parties on one side of the civic–ethnic nationalism continuum in a manner consistent with this article's research question, i.e. based solely on their favourable or unfavourable positions regarding the ‘right to decide’ (3rd determinant in ). To avoid a normative and subjective ideological position while being equally conscious that a methodological selection must be made, two main contextual criteria have been considered (): (i) each political party's official position on the exercise of the ‘right to decide’ as validated through the number of MPs in the regional parliament and city council (6th dimension) and (ii) the intensity of grassroot demonstrations in the three main metropolitan hubs (9th dimension). Nonetheless, this article acknowledges the not-insignificant implications of several political parties, revealing subtle ambiguities regarding their positions on the ‘right to decide’. For instance, the PSOE and the Socialists’ Party of Catalonia (Partit dels Socialistes de Catalunya, PSC; Tatham & Mbaye, Citation2018, p. 659) which is the Catalan branch – despite being clear instigators of the early ‘Catalanist’ movement – as well as the Socialist Party of the Basque Country-Basque Country Left (Partido Socialista de Euskadi-Euskadiko Ezkerra, PSE-EE), which is the Basque branch, have regularly manifested an official position contrary to the ‘right to decide’. With subtle ambiguities, the positions of those branches differ substantially and discursively from the positive attitude of Podemos-related branches in Catalonia and the Basque Country, that is, the branches known as CatComú/Podem and Elkarrekin/Podemos, respectively.

Three hypotheses of civic/metropolitanised nationalism: geoeconomics, geopolitics and geodemocratics

This article's main hypothesis is that diverse city-region-based political strategies articulated by political parties are determined by metropolitan or non-metropolitan modi vivendi and operandi, respectively, which inform the understanding and framing of the nature of nationalism and its territorial manifestations as either ethnically exclusive or civically inclusive. Discursively, ethnic nationalism derives its rationale from a reimagined historic past with old nation-state references driven by populism, whereas civic nationalism establishes a new set of values around ‘metropolitan’ complex dynamism.

Metropolitan pressures on a state's territorial manifestation differ. Small stateless nations, as with distinct and dominant city-regions, increasingly appear to combine local metropolitan agendas with democratic and governance experimentation, shaping their own versions of a ‘right to decide’ their futures beyond the ‘given’ frameworks of their respective nation-states. Similarly, when confronting these increasingly trans-scalar engagements, metropolitan governance has been capable of re-scaling nation-states by questioning and altering the discursive dominance of territorial competitiveness (geoeconomic hypothesis; Harrison, Citation2007). Consequently, attention and initiatives move towards articulating quests for a greater political scope of self-determination (geopolitical hypothesis; Jonas & Wilson, Citation2018). However, this trend does not necessarily require redrawing territorial boundaries and strengthening borders as in the conventional notion of self-determination. Instead, these quests focus on the increased scope of and potential interest from the bottom-up grassroots movements with regard to democratic engagement, representation, deliberation, and, ultimately, experimentation (geodemocratic hypothesis; Crameri, Citation2016; Harvey, Citation2008). In turn, by articulating the three hypotheses of civic/metropolitanised nationalism, the outlook of the interest in democratic engagement influences political agendas, arrangements for governance, and the pursuit of a city-region's own priorities as part of the ‘right to decide’ on its futures:

The geoeconomic hypothesis refers to cities that have more cooperation with other cities and regions or that coordinate their local policies at the city-regional level. These cities are more likely to favour the ‘right to the city’ and to cooperatively defend their own socio-economic interests. However, growing tensions between nation-states and ‘their’ city-regions have resulted in either political re-scaling of the state through pervasive devolution or resistance to such centrifugal pressures. The financial crisis of 2008 led to questions regarding the suitability of a ‘one-size-fits-all’ orchestration of state territoriality through hierarchical, top-down managed, asymmetric relationships between centres and sub-ordinate, peripheral spaces, as these relationships are particularly pertinent in unitary states. Does this imply the political dissolution of nation-states per se? To some, particularly those in conventional ‘realist’ international relations debates, this hypothesis is heresy because states are fixed and whole geographic entities, mirroring overly narrow notions of geographic ‘containers’ to enact institutionalized politics. However, the growing focus on the economic dimension of statehood and its territorial and institutional manifestation questions the validity of such familiar assumptions as overly simplistic, especially in relation to the growing complexity of the interdependent metropolitan world.

The previous hypothesis leads to the geopolitical hypothesis, which discusses cities that have a more self-conscious sense of metropolitan belonging in connection with their region (hinterland). These cities are more likely to negotiate and permanently update city-regional devolution regimes in relation to the nation-state. For these city-regions, this perspective has provoked a more explicit and self-conscious sense of metropolitan belonging and has renewed the idea of the ‘right to the city’ as the ‘individual liberty to access urban resources’ (Harvey, Citation2008, p. 23). The ‘right to the city’ is an idea and slogan first proposed by Henri Lefebvre in 1968 that has been reclaimed in recent decades by grassroots movements to illustrate the city as a co-produced space. The notion of the ‘right to the city’ has gained international recognition in recent years, as observed in the United Nations Habitat III process and the New Urban Agenda's recognition of this concept as the vision of ‘cities for all’. This hypothesis is particularly evident and timely in Barcelona, where an alternative metropolitanised narrative contrasts with the current hegemonic neoliberal urban model (Islar & Irgil, Citation2018). Populist accusations of the ‘metropolitan elite’ abandoning the ‘rest’ of a territory while furthering their own interests highlights a re-arrangement of the relationship among economic spaces, political agency, and democratic representation. With an increasing number of cities and city-regions seemingly seeking to ‘go it alone’, they have effectively embraced the ‘right to decide’ and acted more autonomously as de facto devolved authorities.

Geodemocratics is the foundation of the third hypothesis, which refers to cities that transparently articulate and co-produce more decision-making processes in cooperation with their citizens. These cities are more likely to nurture a deeper democratic citizenship within the city-region through well-informed consultations and referenda. This condition challenges established structures that deliver state power and control, as nation-states must respond to forms of spatialisation other than a fixed territory. This situation clears a path for new geodemocratics, i.e. the representation of popular will in trans-scalar terms through deliberative bottom-up experimentation with consultations and referenda (Qvortrup, Citation2014). As a result, the project of a national society of citizens, especially liberalism's twentieth-century version, appears increasingly exhausted and discredited. Instead, this development offers new avenues by which to propagate, justify, and construct the ‘right to decide’ (Davidson, Citation2016) as a wider, more urban, and outward-looking range of descriptors of ‘nation’, in contrast to those offered by the non-metropolitanised version that conventionally emphasises separating ‘inside’ from ‘outside’ as a populist and ethnic expression of ‘nationalism’. In this context, the ‘right to decide’ does not mean seceding as a matter of course; rather, it refers to the ability to decide whether to secede or perhaps only to decide on the degree of devolution, while also allowing full independence (Guibernau, Citation2013). The ‘right to decide’ may be a new version of a metropolitan-based ‘right to the city’ (Harvey, Citation2008; Lefebvre, Citation1968; Purcell, Citation2013), in which the civic quest for political-democratic ownership of the city is extended to citizenship. State territoriality, with its particular metropolitan mode de vivre, is less of a descriptor and more a sense of voluntary place-based belonging. Thus, a demos-driven ‘self-determination 2.0’, empowered by a wider range of political ideologies around a civic nationalist movement facilitates a bottom-up and inclusive city-regional political response through ‘metropolitanised’ political parties and grassroots movements (). Referring to this dynamic, Harvey (Citation2008, p. 40) confirms that ‘Lefebvre was right to insist that the revolution has to be urban, in the broadest sense of that term’. Therefore, it remains to be seen whether metropolitan standing and capacity will provide extra agency to small stateless city-regionalised nations on the basis that ‘their’ respective metropolitan centres are of dominant relevance. This basis allows the strategic civic nationalistic ambitions of the three cases presented below to be considered an updated – or expanded – version of a metropolitan-based ‘right to the city’.

Analysis of the metropolitan moment in Catalonia, the Basque Country, and Scotland: From the ‘right to the city’ to the ‘right to decide’ in Barcelona, Bilbao, and Glasgow

These cases are selected because they fulfil the following five criteria. All cases (i) are binary city and regional networked configurations called ‘city-regions’, defined as ‘widely recognized as pivotal socio-economic formations that are key to national and international competitiveness as well as rebalancing the political restructuring processes into nation-states, even changing the geoeconomic, geopolitical, and geodemocratic dynamics beyond and between them’; (ii) are uniquely driven by devolution; (iii) are particularly bolstered by a strong post-industrial and internationalized metropolitan hub (Barcelona, Bilbao, and Glasgow); (iv) claim the ‘right to decide’ their own political status within the nation-state; and ultimately (v) fit into the taxonomy of small, stateless nations in Europe (Calzada, Citation2015) ().

Catalonia (Barcelona, Tarragona, Lleida, Girona, and Països Catalans)

The Basque Country (Bilbao, Pamplona, San Sebastian, Vitoria, and Bayonne)

Scotland (Glasgow, Edinburgh, Aberdeen, Dundee, Inverness, Perth, and Stirling)

The metropolitan moment in each case depends on the geoeconomic context; the geopolitical and geodemocratic hypotheses of national identity, the sense of cohesiveness, and the democratic ownership shape the devolution agendas differently in Spain and the UK. Failure to achieve the ‘right’ mix of structure and political agency may weaken the chances of attaining a mutually satisfactory balance between the claims of respective sovereignties at the level of the territorial states and that of their constituent city-regions. The outcome may lead to unresolved devolution conflicts by forcing two contradictory extremes: insisting on the territorial integrity of the state through the homogeneous re-centralization advocated by a state-centric ethnic nationalistic approach while also threatening that integrity through attempts to force independence (right to secede).

Catalonia (Barcelona)

Although it is on Spain's periphery, Catalonia has often held a central position in Spanish politics (Ehrlich, Citation1997). During XIX and the most of the XX centuries, Barcelona was the most advanced and modern city in Spain. Barcelona's success furthered the prestige of the ‘Catalanist’ movement, which was initially exclusively federalist but in recent years has become more pro-secessionist (Guibernau, Citation2013). The historical goal of mainstream ‘Catalanism’ consisted of securing accommodations within Spain combined with direct participation in the EU. However, this accommodation has resulted in an unstable equilibrium, which includes recentralising policies originating from the Spanish central government. Similarly, the expectation of a ‘Europe of Regions’ (Hepburn, Citation2008) is far from fulfilled, reinforcing Catalonia's perception that the only means to participate in the EU is by having a state of its own. Thus, currently, the main claim articulated by civic nationalism is the ‘right to decide’, which previously requested slight federal reforms and national recognition within the nation-state but now opts for requesting full independence due to the impossibility of attaining its former goals.

Compared with federalism and polycentricism, traditions of centralism and unitarism provide different circumstances and different political-institutional consciousnesses of power and representation. For instance, according to the Spanish Constitution, Spain is a single ‘demos’ formed by ‘all Spaniards’, including the Catalans and Basques. Consequently, any attempt to hold a referendum on self-determination is deemed illegal and an attack on the very state that is representative of the whole demos. However, the 1.5 million people who demonstrated in Barcelona in favour of self-determination on 11 September 2012 – and on many occasions thereafter – illustrate the strength of the civic/metropolitanised nationalistic movement (Serrano, Citation2013) that favours dissolving the concept of a single ‘demos’ by overcoming the ethnic nature of citizenship, thus blending the Spanish and Catalan identities with the opportunity to vote democratically in favour of or against independence. In turn, these events question the validity of the single-state-equals-single-demos doctrine. Legal arguments (‘Empire of Law’) no longer suffice. Much of this confrontation appears to be related to the political inability of the Spanish nation-state to contemplate alternatives, such as a shift from unitary to more federal structures; instead, the nation-state insists that the constitutional provisions for centralism are non-negotiable. Demonstrating the two roles of such a metropolis, Barcelona, as Spain's primary international city, is an internationally oriented, recognized, and successful metropolis, although much of the outside world simply views it as ‘Spanish’; however, Barcelona also serves as the main platform for the expression and representation of Catalan identity.

As a sign of its growing empowerment, in 1998, Barcelona approved the Municipal Charter, which provided the framework for a devolution of institutional powers in local policy-making coupled with greater financial resources to cover those responsibilities. Thus, as Serrano (Citation2013, p. 541) argues, ‘opposition by the Spanish central government to delivering greater fiscal powers to Catalonia as a region has effectively been bypassed’. In its metropolitan form, the scenario of independence has been gaining ‘realness’ and more general political acceptability to the point where the Catalan government started the process of unilateral disconnection from Spain. Unsurprisingly, Catalonia's elected parliament felt sufficiently emboldened after its successes in the 2015 and 2017 regional elections to challenge Madrid's insistence on continued centralization and the territorial integrity of the state. The new radical-left mayor of Barcelona, Ada Colau (BComú), appears ‘cautiously ambivalent’ in confronting this situation, while Barcelona remains trapped in the city-regional/metropolitan territory. Colau supports the popular referendum to implement the ‘right to decide’ while also taking no clear position on Catalan independence. This attitude illustrates how metropolitan interests embrace the implementation of experimental democratic practices, such as consultations and referenda, while leaving open the choice of each citizen to ‘decide or not’ regarding independence from Spain.

Basque Country (Bilbao)

A similar conflict also appears within the complex and multi-faceted nature of the Basque Country: The Basque Autonomous Community (BAC) and the Chartered Community of Navarre (CCN) exist on the Spanish side, whereas the Northern French Basque Country (NFBC) exist on the French side of the Basque Country. Bilbao is the primary metropolitan centre that projects Basqueness internationally. However, this paradiplomatic role produces a Bilbaoese city-regional version, as the city also has its own metropolitan agenda that seeks to step out of the Spanish-Basque context and into the international arena in search of recognition as a place of new-found post-industrial economic competence and success. Bilbao has extended beyond the Basque context by combining metropolitan international ambitions, traditions, and modus operandi with underlying Basqueness. As in Glasgow and Barcelona, intertwined urban and metropolitan innovative policies provided Bilbao international with recognition, confidence, and political ambition, which projected the city's success onto the hinterland and beyond. This stance produces a particular ‘brand’ of identity by using the Basque Country to depict a small, unique, manufacturing-based, resilient, financially self-governed territorial nation in Europe. Since the organization known as Basque Country and Freedom (Euskadi Ta Askatasuna, ETA) announced its dissolution on 2 May 2018, the city-region, which is spatially configured as a polycentric city-network, has been making strong progress towards improving both its external image, as evidenced by tourism, and its internally conditions. This city-region has done this by amalgamating – in a unified and peaceful setting – the metropolitan manifestations of Basqueness in the main cities with those of the non-metropolitan or rural hinterland from the Spanish and French sides of the border.

The Basque regional government decides local and regional policies via a complex province-council-driven confederal system. Bilbao combines strong metropolitan political leadership with an existing entrepreneurial urban culture. The latest developments in defining Basque nationality include active engagement by a new government representing CCN, which is driven by its capital city, Pamplona, and a mobilization of the Northern French Basque Country (NFBC; Pays Basque). This engagement is also driven through the provision of a new institutional setting entitled the ‘Single Commonwealth’, which was voted into existence by the region's constitutive municipalities as the backdrop for a unified and historically Basque metropolitanised nation.

Scotland (Glasgow)

In the case of Scotland, the self-government demands that have been formulated since the early 1970s under the banner of ‘devolution’ of powers to the city-region are built on a much longer history of institutional and administrative autonomy. Since the 1970s, Glasgow has retained a strong political agenda and voice of its own within those debates by advocating the economic case of Scottish independence through the exponential growth of the SNP in the city; in 1995, the SNP won just one seat, while in 2017, it won 39 (Elias, Citation2018; Wilson, Citation2018). This result led to a strong showing in favour of independence at the referendum, with 194,779 ‘yes’ votes over 169,347 ‘no’ votes, contrasting with the overall win of the ‘no’ votes across Scotland (STV, Citation2014). This apparent ‘metropolitan moment’ of casting votes suggests the fusion of a nationalist, independence-minded discourse with distinct metropolitan perspectives, experiences, and values that also include a sense of ‘own’. Because of their relative ‘weight’, small nations with large metropolitan areas are – as political-economic foci – disproportionately prone to the effects of the ‘metropolitan factor’. Through their independently built network relations that extend beyond the immediate national context, dominant city-regions are moving to the foreground of articulating and utilizing their growing international visibility and connectivity to promote a particular (metropolitan) version of a nationalist agenda as part of the wider quest for nation-based independent statehood based on internationalism. This development requires fusing internationalism, social progressiveness, inclusiveness, and likely political-economic entrepreneurialism.

At present, the role of metropolitanisation allows Glasgow to articulate in parallel a diverse set of complex strategies – sometimes even antagonistic – by tailoring city-regional internal compositions through collaborative urban networks: on the one hand, the British Core Cities, and on the other hand, the Scottish Cities Alliance. Both positions are important vehicles used to formulate goals, exercise power, and lobby political influence in aspiring small stateless nations and existing nation-states as a whole. Specific metropolitan interests are illustrated by the fact that Glasgow, now SNP-controlled, is a member in both, which reveals the remarkable function that Glasgow plays in embracing a wide range of political strategies. Whereas the British Core Cities group (Citation2018) currently lobbies the UK government through the articulation of an urban network composed of its ten primary metropolitan hubs (Birmingham, Bristol, Cardiff, Glasgow, Leeds, Liverpool, Manchester, Newcastle, Nottingham, and Sheffield), the Scottish Cities Alliance (Citation2018) was formed by the Scottish Government in 2011 and is a founding member of the Eurocities network in the EU. This latter alliance depicts a regionally cohesive composition encompassing large (Glasgow and Edinburgh), medium (Aberdeen and Dundee), and small (Inverness, Perth, and Stirling) urban hubs that contribute via specific projects to the city-regional network configuration, while simultaneously being strongly in favour of Scottish independence. In effect, for the Scottish Cities Alliance, nationality (independence arguments) and metropolitan interests (geodemocratics) reinforce each other and blend to create a new congruent synthesis as an expression of a civic or metropolitanised nationalism.

Conclusion

This article has presented the cases of three small stateless city-regional nations to provide a better understanding of how metropolitanisation and the ‘right to decide’ are increasingly invigorating the devolution-driven debate in Europe while also provoking the (re)emergence of a pattern of stateless civic/metropolitanised nationalism and its opposition in the form of an ethnic/non-metropolitanised nationalism. In the context of the secessionist movements that have re-emerged in the UK and Spain since 2014, this article's main argument is that metropolitan areas and major cities such as Barcelona, Bilbao, and Glasgow are pervasively fuelling the devolution debate according to the three hypotheses presented: geoeconomics, geopolitics, and geodemocratics. Furthermore, the findings reveal that geo-democratic manifestations are currently becoming much more essential. Paradoxically equal in the three cases, more parliamentary support in the regional governments and city councils – as well as grassroots demonstrations claiming the ‘right to decide’ – are taking place in Barcelona, Bilbao, and Glasgow. However, it appears that events such as referendums and consultations to articulate the ‘right to decide’ are less likely to occur in the future.

depicts the main conclusion of the article. In contrast to widespread perceptions, a majority of all three regional parliaments back the potential exercise of the ‘right to decide’ in the following order: 75% of MPs in the Basque parliament,Footnote1 57% of MPs in the Catalan parliament, and 54% of the MPs in the Scottish parliament. Likewise, the same occurs within the three city councils, where 73% of the representatives in the Bilbao City Council favour the ‘right to decide’; 71% of the Barcelona City Council and 54% of the Glasgow City Council also favour this right. Each case requires further examination, as the support could vary depending on political interplay. Although having political support favours exercising the ‘right to decide’, it is not sufficient to ensure that right. Another interesting avenue for research would be to find correlations between regional and municipal political dynamics in terms of the interconnected multi-level governance implications of devolution. As this article has argued from the beginning, gaining – or not gaining – metropolitan support within city-regions will determine the future directions of devolution debates.

In comparative terms, the article's empirical research assumed not only the potential ambiguity of political parties regarding the ‘right to decide’ but also the methodological dichotomy of civic and ethnic nationalisms; these assumptions were necessary to classify certain actors on the continuum. However, this article challenged the mainstream view that does not distinguish the ‘right to decide’ from full independence, and it examined how the metropolitan arguments actually influence the development of broader phenomena beyond the fixed nation-state territoriality by establishing two versions of nationalism: civic and ethnic. The (re)emergence of civic nationalism may stem from the metropolitan ethos and demos. Likewise, this article encourages further research that will improve theoretical frameworks and analytical tools (i) to better examine civic/metropolitanised nationalism empirically as a pervasive, novel, emergent and timely outcome that blends metropolitanisation phenomena, the ‘right to decide’, devolution, inclusiveness, and manifestations of nationalisms and (ii) to accurately interpret how metropolitan socio-political behaviour is forging the discursive and normative relevance of devolution.

To provide further nuanced causal explanations among the role of metropolitanisation and the emergence of civic/metropolitanised nationalism through claims of the ‘right to decide’ in devolution debates, this article has attempted to elucidate potential new research avenues without aiming to be entirely prescriptive in regards to the presented findings. Thus, the correlation among metropolitanisation, the ‘right to decide’, devolution, and types of nationalism will require in-depth interdisciplinary fieldwork research to establish solid foundations in accordance with what this article has preliminarily initiated.

To conclude, this article envisions that metropolitan-driven demand for the ‘right to decide’ might inevitably provoke and determine unique new waves and scenarios around devolution debates in each case. In such case, a ‘transformative alliance’ around civic nationalist patterns is likely to continue gathering a wide range of ‘progressivist’ political parties, social movements, and civic groups in a novel communitarian amalgamation that alters the contemporary nation-states of Spain and the UK. Parliamentary representation and grassroots movements may put pressure on the devolution debate given that the majority in all three regional and municipal parliaments back the ‘right to decide’ officially and discursively. However, gaining critical mass from the metropolitan areas will remain unpredictable, as city-regional strategic competence is a key political determinant.

Acknowledgements

I am extremely grateful to Ronan Paddison and two anonymous reviewers for their insightful commentaries on an earlier version of the paper. Conversations with Tassilo Herrschel, Andy E. Jonas, and Martin Jones also helped me in thinking through certain items.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes on contributor

Dr Igor Calzada, MBA, FeRSA, is a Lecturer, Research Fellow, and Policy Adviser in the Urban Transformations ESRC and in the Future of Cities Programmes at the University of Oxford and in the Institute for Future Cities at the University of Strathclyde in Glasgow. His research focusses on (i) benchmarking city-regions through processes of rescaling nation-states, devolution and pervasive metropolitanisation and (ii) comparing cases of smart cities in transition paying special attention to the techno-political implications of data and to the technological sovereignty. Outside academia he worked for a decade in the Mondragon Co-operative Corporation and was director of innovation in the Basque regional government in (Spain). Further information: http://www.igorcalzada.com/about.

ORCID

Igor Calzada http://orcid.org/0000-0002-4269-830X

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. We must employ the term BAC (Basque Autonomous Community), insofar as the Basque regional parliament represent only citizens of this administrative entity. The Basque Country encompasses a wider territorial dimension consisting of the BAC, CCN (Chartered Community of Navarre), and the NFBC (Northern French Basque Country) (Calzada, Citation2015).

References

- Arendt, H. (1949). The rights of man: What are they? Modern Review, 3, 4–37.

- Becker, S., Fetzer, T., & Novy, D. (2016). Who voted for Brexit? A Comprehensive district-level analysis. Warwick: University of Warwick – Centre for Competitive Advantage in the Global Economy – Department Economics.

- Beel, D., Jones, M., & Jones, I. R. (2018). Elite city-deals for economic growth? Problematizing the complexities of devolution, city-region building, and the (re)positioning of civil society. Space and Polity, 1–21. doi:10.1080/13562576.2018.1532788

- Berlin, I. (1979). Against the current: Essays in the history of ideas. London: Pimlico.

- Berlin, I. (1996). The sense of reality: Studies in ideas and their history. London: Pimlico.

- Bieber, F. (2018). Is nationalism on the rise? Assessing global trends. Ethnopolitics, 17(5), 519–540.

- Billig, M. (1995). Banal nationalism. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- Brenner, N. (2003). Metropolitan institutional reform and the rescaling of state space in contemporary Western Europe. European Urban and Regional Studies, 10(4), 297–324.

- Brown, D. (1999). Are there good and bad nationalisms? Nations and Nationalism, 5(2), 281–302.

- Cagiao y Conde, J. (2018). Micronacionalismos. ¿No seremos todos nacionalistas? Madrid: Catarata.

- Cagiao y Conde, J., & Ferraiuolo, G. (2016). El encaje constitucional del derecho a decidir: un enfoque polémico. Madrid: Catarata.

- Calzada, I. (2014). The right to decide in democracy between recentralisation and independence: Scotland, Catalonia and the Basque Country. Regions Magazine, 296(1), 7–8.

- Calzada, I. (2015). Benchmarking future city-regions beyond nation-states. Regional Studies, Regional Science, 2(1), 351–362.

- Cetrà, D., Casanas-Adam, E., & Tàrrega, M. (2018). The 2017 Catalan independence referendum: A symposium. Scottish Affairs, 27(1), 126–143.

- Cetrà, D., & Harvey, M. (2018). Explaining accommodation and resistance to demands for independence referendums in the UK and Spain. Nations and Nationalism, 1–23. doi:10.1111/nana.12417

- Convery, A., & Lundberg, T. C. (2017). Decentralization and the centre right in the UK and Spain: Central power and regional responsibility. Territory, Politics, Governance, 5(4), 388–405.

- Core Cities. (2018, November 25). Retrieved from https://www.corecities.com/publications

- Crameri, K. (2016). Do Catalans have ‘the right to decide’? Secession, legitimacy and democracy in twenty-first century Europe. Global Discourse, 6(3), 423–439.

- Curtice, J. (2018, June 6). Nationalism ‘means something different’ in Scotland. Retrieved from https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-44300916

- Davidson, N. (2016). Scotland, Catalonia and the ‘right’ to self-determination: A comment suggested by Kathryn Crameri’s ‘do Catalans have the “right to decide”? Global Discourse, 6(3), 440–449.

- Ehrlich, C. E. (1997). Federalism, regionalism, nationalism: A century of Catalan political thought and its implications for Scotland in Europe. Space and Polity, 1(2), 205–224.

- Elias, A. (2018). Making the economic case for independence: The Scottish National Party’s electoral strategy in post-devolution Scotland. Regional & Federal Studies, 1–23. doi:10.1080/13597566.2018.1485017

- Gellner, E. (1983). Nations and nationalism. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

- Gillespie, R. (2016). The contrasting fortunes of pro-sovereignty currents in Basque and Catalan nationalist parties: PNV and CDC compared. Territory, Politics, Governance, 5(4), 1–19.

- Guibernau, M. (2013). Secessionism in Catalonia: A response to Goikoetxea, Blas, Roeder, and Serrano. Ethnopolitics, 12(4), 410–414.

- Harrison, J. (2007). From competitive regions to competitive city-regions: A new orthodoxy, but some old mistakes. Journal of Economic Geography, 7(3), 311–332.

- Harvey, D. (2008). The right to the city. New Left Review, 53, 1–16.

- Hepburn, E. (2008). The rise and fall of a ‘Europe of the regions’. Regional & Federal Studies, 18(5), 537–555.

- Islar, M., & Irgil, E. (2018). Grassroots practices of citizenship and politicization in the urban: The case of right to the city initiatives in Barcelona. Citizenship Studies, 22(5), 491–506.

- Jessop, B. (1990). State theory: Putting the capitalist state in its place. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Johnston, R., Manley, D., Pattie, C., & Jones, K. (2018). Geographies of Brexit and its aftermath: Voting in England at the 2016 referendum and the 2017 general election. Space and Polity, 1–26. doi:10.1080/13562576.2018.1486349

- Jonas, A. E. G., & Wilson, D. (2018). The nation-state and the city: Introduction to a debate. Urban Geography, 1–3. doi:10.1080/02723638.2018.1461991

- Keating, M. (2005). Policy convergence and divergence in Scotland under devolution. Regional Studies, 39(4), 453–463. doi: 10.1080/00343400500128481

- Keating, M. (2017). Contesting European regions. Regional Studies, 51(1), 9–18.

- Koch, N., & Paasi, A. (2016). Banal nationalism 20 years on: Re-thinking, re-formulating and re-contextualizing the concept. Political Geography, 54, 1–6.

- Kymlicka, W., & Straehle, C. (1999). Cosmopolitaniam, nation-states, and minority nationalism: A critical review of recent literature. European Journal of Philosophy, 7(1), 65–88.

- Lecours, A. (2000). Ethnic and civic nationalism: Towards a new dimension. Space and Polity, 4(2), 153–166.

- Lefebvre, H. (1968). Le droit à la ville. Paris: Anthropos.

- López, J. (2018). El derecho a decidir: la vía Catalana. Tafalla: Txalaparta.

- MacLeod, G., & Jones, M. (2018). Explaining ‘Brexit capital’: Uneven development and the austerity state. Space and Polity, 1–26. doi:10.1080/13562576.2018.1535272

- Massetti, E. (2018). Left-wing regionalist populism in the ‘Celtic’ peripheries: Plaid Cymru and the Scottish National Party’s anti-austerity challenge against the British elites. Comparative European Politics, 1–18. doi:10.1057/s41295-018-0136-z

- Massetti, E., & Schakel, A. H. (2017). Decentralisation reforms and regionalist parties’ strength: Accommodation, empowerment or both? Political Studies, 65(2), 432–451.

- Maxwell, A. (2018). Nationalism as classification: Suggestions for reformulating nationalism research. Nationalities Papers, 46(4), 539–555.

- Mulle, E. M., & Serrano, I. (2018). Between a principled and consequentialist logic: Theory and practice of secession in Catalonia and Scotland. Nations and Nationalism, 1–22. doi:10.1111/nana.12412

- Mulligan, G. F. (2013). The future of non-metropolitan areas. Regional Science Policy & Practice, 5(2), 219–224.

- Patberg, M. (2018). After the Brexit vote: What’s left of ‘split popular sovereignty? Journal of European Integration, 1–15. doi:10.1080/07036337.2018.1482290

- Purcell, M. (2013). The right to the city: The struggle for democracy in the urban public realm. Policy and Politics, 41(3), 311–327.

- Qvortrup, M. (2014). Referendums on independence, 1860–2011. The Political Quarterly, 85(1), 57–64.

- Rodon, T., & Guinjoan, M. (2018). When the context matters: Identity, secession and the spatial dimension in Catalonia. Political Geography, 63, 75–87.

- Rodríguez-Posé, A. (2018). The revenge of the places that don’t matter (and what to do about it). Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 11(1), 189–209.

- Sage, D. (2014). The Scottish National Party: Transition to power. Regional & Federal Studies, 24(4), 532–533.

- Sanghera, G., Botterill, K., Hopkins, P., & Arshad, R. (2018). ‘Living rights’, rights claims, performative citizenship and young people: The right to vote in the Scottish independence referendum. Citizenship Studies, 1–16. doi:10.1080/13621025.2018.1484076

- Scottish Cities Alliance. (2018, November 25). Scottish cities alliance investment prospectus. Retrieved from https://www.scottishcities.org.uk/media/publications

- Sellers, J. M., & Walks, A. R. (2013). Introduction: The metropolitanisation of politics. In J. M. Sellers, D. Kübler, M. Walter-Rogg, & A. R. Walks (Eds.), The political ecology of the metropolis (pp. 3–36). Colchester: ECPR Press.

- Serrano, I. (2013). Just a matter of identity? Support for independence in Catalonia. Regional & Federal Studies, 23(5), 523–545.

- Skey, M., & Antonsich, M. (2017). Everyday nationhood: Theorising culture, identity and belonging after banal nationalism. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Smith, A. D. (1986). The ethnic origins of nations. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

- STV. (2014, September 19). Dissapointment for Yes campaigners as Scottish voters back Union. Retrieved from http://stv.tv/news/politics/news/292676-disappontment-for-yes-campaigners-as-referendum-defeat-unfolds/

- Tatham, M., & Mbaye, H. A. D. (2018). Regionalization and the transformation of policies, politics, and Polities in Europe. JCMS: Journal of Commons Market Studies, 56(3), 656–671.

- Uriarte, P. L. (2015). El Concierto Económico Vasco: Una visión personal. Bilbao: Concierto Plus.

- Wilson, A. (2018). Scotland the new case of optimism: A strategy for inter-generational economic renaissance. Edinburgh: The Sustainable Growth Commission.

- Winlow, S., Hall, S., & Treadwell, J. (2017). The rise of the right: English nationalism and the transformation of working-class politics. Bristol: Policy Press.