ABSTRACT

State-region relations involve negotiations over the power to (re)-constitute local spaces. While in federal states, power-sharing ostensibly gives regions a role over many space-making decisions, power asymmetries affect this role. Where centralization trends may erode regional agency, law can provide an important tool by which regions can assert influence. We examine a case where, in response to a proposed Russian federal law highly unpopular with a regional population, the region's government sought to ameliorate its potential impacts by using opportunities to co-produce the law, amending regional legislation, and strategically implementing other federal and regional laws to protect its territory.

Introduction

Central and persistent to State-region relations are the struggles and negotiations over the power to (re-)constitute local spaces/places. Differences often result from different spatial imaginaries for the same territory and asymmetric power interactions that enable the state/centre to unilaterally impose its will to re-make places according to its visions. In federal states, power-sharing ostensibly gives regions a role over many space/place-making decisions and activities, including over the making of laws that remake space. In reality that role varies.

The Russian Federation, after undergoing significant decentralization and devolution of power to its 80-plus constituent ‘federal subjects’ or ‘regions’ (the term we use in this paper) in the 1990s, has in this millennium increasingly centralized power, including through numerous legislative reforms that constrain regional autonomy. Nevertheless, law has also provided niches of agency for regions to assert some power in the remaking of their spaces.

In this paper, our goals and intended contributions are three-fold:

While focusing thematically on the core of legal geography – the ‘legal fabrication of geographical phenomena’ (Delaney, Citation2015, p. 98), to examine the process of space/place-making in an area under-represented and ‘other-than-familiar’ in the ‘Western’ (English-language) legal geography literature (cf. Braverman, Blomely, Delaney, & Kedar, Citation2014; Delaney, Citation2017).

To challenge the limited agency that ‘Western’ literature recurrently credits to regional actors in its common representation of the Russian Federation as a monolithic state (cf. Russell, Citation2015). While acknowledging the asymmetry of centre-region power relations, we identify ‘niches of agency’ that its federal structure of sharing power over law-making provides its regions;

Through a detailed description of one case, to explore how regional actors can enlarge these niches to contest the centre's spatial visions for their territory, not in resistance to, but rather under the aegis of, the state. This in-depth account may provide the basis for comparative works across legal systems, which are currently scarce (Kedar, Citation2014).

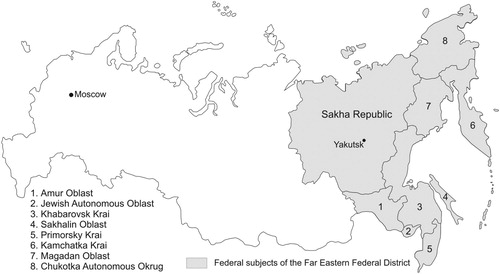

Thus, this paper explores the multi-faced responses of one region of the Russian Federation, the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia) (henceforth RS(Ya)) to a proposed federal law, that on the Far East Hectare (FEH). While the law applies to all nine regions that constituted the Far East Federal District (FEFD) at the writing of this paper,Footnote1 RS(Ya) stands out in several ways. It is territorially the largest region (comprising 50% of the FEFD); its vast richness of natural resources makes it economically critical for the Russian Federation; a non-Russian ethnic group, the Sakha (Yakuts), form the plurality of its population, and predominate among the regional elite holding political power; it has passed legislation on indigenous rights that significantly exceeds the protections offered by federal law (Fondahl, Lazebnik, & Poelzer, Citation2000; Ivanova & Stammler, Citation2017); and it has a track record of pursuing a higher level of self-determination more vigorously than most other regions (Balzer, Citation2016). Regions exert different pressures on the centre, using a variety of tactics, from armed insurrection to working within the system. We demonstrate through this article what is possible for a region of the Russian Federation to achieve by working within the system, in terms of influencing ‘the legal fabrication of geographical space’ (Delaney, Citation2015, p. 98) in ways it desires when its visions for its space/territory differ from central visions. Regions within Russia are not only both the object of federal law-making and the subject of their own law-making; they can exert a level of autonomy within the safe haven of the ‘dictatorship of law’ that legitimates their efforts.

Methods

This article is based on a reading of draft laws, commentaries regarding those laws (primarily those published on the RS(Ya)'s State Assembly website), analysis of policies and government programmes, and discussion in the mass media. As well, numerous semi-structured interviews were conducted with local administrators, indigenous leaders at the federal, republican and local levels, individuals involved in providing expertise during the law-making process, and (mostly indigenous) residents of the southern areas of RS(Ya), during fieldwork carried out in 2016, 2017 and 2018. In August 2016, 40 semi-structured interviews were carried out in Yakutsk, Olekminsk, and Tyanya and environs; in February 2017, six discussions were held in Moscow; in May 2017, 39 semi-structured interviews were carried out in Yakutsk, Neryungri, Iengra, Aldan and Khatystyr. The majority of these touched on the FEH programme, although at different levels of detail. The focus of our research was on indigenous territorial rights; as explained in more detail below, the issue of the FEH repeatedly came up due to its connection to these rights. Numerous informal discussions with law-makers and political activists over the same period (2016–2018) further informed this work.

The Far East Hectare Law

The ‘Far East Hectare Law’ – formally, Russian Federal Law No 199-F3,

On the specifics of granting to citizens land plots in state or municipal ownership, located in the territories of the constituent entities of the Russian Federation within the Far East Federal District, and on the introduction of changes to individual legal acts of the Russian Federation. (Russian Federation, Citation2016)

Coming into effect on 1 June 2016 (and running until 1 January 2035), the FEH programme is one of a whole set of measures adopted by the Russian government to strengthen Russian sovereignty in the Far East (Kuhrt, Citation2012), in the wake of the massive outflow of population from this area in the post-Soviet period, a trend not halted by economic stabilization in the 2000s (Heleniak, Citation2010). The demographic decline in this periphery is seen to pose geopolitical and security challenges. Apprehensive about the growing Chinese influence in the FEFD (Billé, Delaplace, & Humphrey, Citation2012; Laruelle, Citation2015; Lo, Citation2009), the Russian government assessed that intervention was needed to encourage (re)settlement and economic development (Shcherbakov, Citation2018). It established a specific ministry to deal with development in this sensitive geopolitical region, the Ministry of Development of the Far East.

Compared to many proposed laws, the FEH Law's rapid adoption was attributed by some to President Vladimir Putin's immediate support for the concept and request for its quick drafting. The idea was reportedly conceived and communicated to Putin in mid-January 2015 by Yuri Trutnev, Vice Chair of the Russian Government and President's Envoy to the Far East Federal District (Dal’nevostochnyy, Citation2016b, Citation2016c). The executive branch of federal government was immediately tasked with developing a proposal for such a law, and within a week a working group under the federal Ministry of Development of the Far East had been established to accomplish this (Dal’nevostochnyy, Citation2016c; Prokop’ev, Citation2017). The Russian government approved the draft law in mid-November 2015, and sent it to the State Duma (the lower legislative house of the Federal Assembly or parliament) in early December 2015. President Putin appealed to the Duma deputies to promptly review it, and the Duma accepted the draft law at its first reading on 18 December 2015. It set a period of 30 days for comment and suggested amendments (Dal’nevostochnyy, Citation2016c). Following revisions based on the input provided during that period, the law was adopted by the Duma on 22 April 2016, by the Federation Council (upper legislative house) on 27 April, and signed into law by President Putin on 1 May 2016.

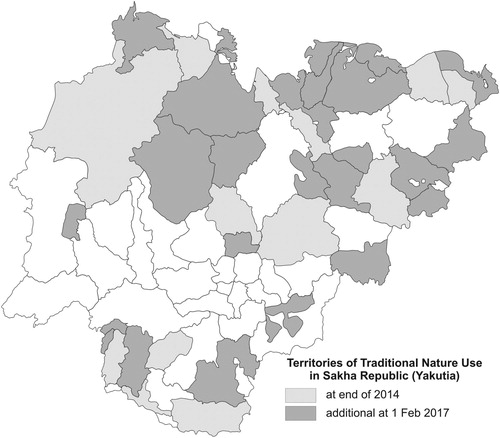

Within the Far East Federal District, not all lands are available for allocation of FEHs. Land categorized as Specially Protected Natural Territories (e.g. parks, nature reserves) and lands designated as ‘Territories of Traditional Nature Use’ (see Section 3.3 below) are excluded from selection, as are lands containing mineral wealth and those sites containing objects of historical or cultural importance. FEHs also cannot be allocated within buffer zones around cities, the size of which depends on the city's population. Lands already legally owned or allocated to users are exempt while their tenure persists (Russian Federation, Citation2016).

The various regions of Russia's Far East Federal District reacted to the centrally directed re-territorializing project proposed by this law in a variety of ways. As we recount below, RS(Ya)'s government took a particularly active approach, through the process of the law-making and implementation, in order to shape this re-territorializing project more the benefit of its populace, as well as to assert its authority in the development of its territory.

Republic of Sakha (Yakutia): government responses to the Far East Hectare Law

RS(Ya) is the largest of over 80 regions (republics, territories, provinces, etc.) that constitute the Russian Federation (). Its territory, close to the size of India, covers 18% of Russia, although its population is less than one million persons. The Sakha or Yakut people, of Turkic origin, comprised 49% of the population at the last census (2010), while Russians made up 38%. RS(Ya) is also home to five ‘Indigenous Numerically Small Peoples of the North’ (henceforth ‘Indigenous peoples’), who together constitute about 4% of the population. Russian law provides for certain protections of these peoples (each numbering less than 50,000 individuals) (Kryazhkov, Citation2013), while not covering the Sakha. The majority of Sakha people historically practiced transhumant horse and cattle husbandry; the Indigenous peoples mostly pursued reindeer herding and hunting. All these activities require extensive land use, and those peoples practicing them have close connections to the land (Crate, Citation2006; Takakura, Citation2015; Vitebsky, Citation2006). The sedentary logic of the FEH law, typical of ‘nation-states’, involves exclusive access and control over clearly circumscribed territories (Gilbert, Citation2007). This contradicts the traditional land governance systems and territorial needs of the Sakha and Indigenous peoples: nomadic peoples’ governance principles involve flexible relations with neighbours in using the resources of territories too large to be defended for permanent control (Stammler, Citation2005).

Russia's regions enact their own laws, which, while required to not contradict federal laws, can diverge from them. RS(Ya) had an early history in the post-Soviet period of asserting its sovereignty vis a vis the centre (Moscow) (Argounova-Low, Citation2004; Balzer & Vinokurova, Citation1996; Tichotsky, Citation2000). Its approach, based on the division of powers between centre and region outlined in the Russian Constitution (Russian Federation, Citation1993), has been one of using the legal system rather than pursuing separatism. The republic's own progressive and flexible legal approaches to protecting the rights of Indigenous peoples and their ‘traditional’ activities, and providing them with greater territorial rights, have given it a reputation for leadership in this area, as has the fact that much of its legislation regarding Indigenous rights predated federal legislation and surpassed its (eventual) protections (Fondahl et al., Citation2000; Fondahl, Lazebnik, Poelzer, & Robbek, Citation2001; Kryazhkov, Citation2010). RS(Ya)'s local variants of laws and legal practices, as well as providing for geographically relevant adaptations, have served to resist erosion of RS(Ya)'s authority vis a vis Moscow (Ivanova & Stammler, Citation2017; Stammler & Ivanova, Citation2016).

The proposed FEH law raised significant concerns among both RS(Ya)'s politicians and the public. Declared ‘perhaps the most discussed legislative act’ among both the citizenry and governmental officials of Yakutia (Il Tumen, Citation2016), it incited large public demonstrations and protests, letter writing campaigns, and editorials (Miting, Citation2016). One official observed that the overwhelming reaction to the FEH programme was negative, estimating that ‘95% of those expressing an opinion were against it in Yakutia’ (Interview, Yakutsk, 7 August 2016). Indigenous leaders expressed their grave concerns about the alienation of indigenous lands via FEHs (Interview, Yakutsk, 7 August 2016). Public protesters articulated fears of ‘outsiders grabbing land’ for the speculative development of RS(Ya)'s natural resources, causing environmental degradation due to their lack of knowledge of the area's geographical specificities (e.g. permafrost), and eroding the ability of those pursuing ‘traditional activities’ to continue to do so. Governmental concerns also focused on the level at which key decisions regarding land allocation would be located. What controls would RS(Ya) exert over the lands within its boundaries in the face of the FEH law?

Resisting the colonialist spatial imagining of Russia's periphery as underutilized (and under-governed?) (Billé et al., Citation2012), that informed the drafting of the FEH law, the RS(Ya) government responded to the proposed law in several ways. It suggested amendments and modifications to the draft federal law(sFootnote2), at opportunities provided during the legislative process, that aimed to privilege the populace of RS(Ya), as well as to limit the territory in which FEHs could be allocated. It supported its residents to take advantage of the staged introduction of the law, which provided for their earlier access to FEHs, after having successfully proposed the introduction of such stages as amendments to the draft law. It harnessed another set of laws, federal and republican, to further reduce the area of RS(Ya) available for allocation as FEHs. It amended republican law to increase the territory that certain residents of RS(Ya) could receive (thus making these unavailable to outsiders). Each of these responses is explored below.

Response 1: shape the federal law in ways more beneficial to RS(Ya)populace

One initial reaction to the draft law was to petition the federal government to remove RS(Ya) from the proposed law's territory. Former republican president Mikhail Nikolaev, advised this exclusion (along with Chukotka and Magadan) (Severnyy, Citation2016). ‘Sir’ (meaning ‘land’ in Sakha), a public movement within RS(Ya), repeatedly appealed to the republican government for exclusion, staging several demonstrations (Sir, Citation2016). The protest reached the level of the UN's Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues in 2016, with a presentation noting that ‘the Sakha people were against the giving away of their ancestral land’ (Gavrileva, Citation2016).

However, government officials in RS(Ya) worked under the assumption that the federal law's acceptance was inevitable, given Putin's strong support for it, and that RS(Ya) would be included under the FEH Law, but also that there was a real opportunity to try to shape the federal law. One Indigenous leader characterized this approach as pragmatic: ‘they never even considered [the law] not passing – rather the realistic option was to work for changes and additions’ (Interview, Yakutsk, 7 August 2016). This response continued RS(Ya)'s longstanding approach of finding a space within ‘the system’ to pursue a level of sovereignty, rather than confronting the centre (Argounova-Low, Citation2004). Understanding law as a significant site for the (re)production of territory, the RS(Ya)'s government submitted amendments and modifications to the draft federal law at several points, starting almost immediately after the plan to draft such federal legislation became public.

On 26 January 2015, Alexander Zhirkov, Chairman of RS(Ya)'s State Assembly, established an Interdepartmental Working Group to respond to the proposed FEH law. which began to discuss desired modifications (the same day that the federal Ministry of Development of the Far East established its working group) (Dalnevostochnyy, Citation2016a, Citation2016c). That is, RS(Ya) immediately began to exercise its right to co-produce, with the federal government, the FEH law. Recognizing the potential impact of the FEH law on the space within its boundaries, it challenged the federal government to amend its approaches in cases where these would likely constrain opportunities for RS(Ya) residents.

The draft law was approved by the Government of the Russian Federation in mid-October 2015, and immediately introduced to the Duma. It was reviewed and approved on 1 December 2015 at a ‘null reading’ by the Duma's Civic Chamber, the body that, inter alia, reviews draft legislation.Footnote3 During discussion period Deputy Elena Golomarëva from RS(Ya), a staunch defender of indigenous rights,Footnote4 represented the view of many Sakha residents and politicians, in requesting that lands that were used by Indigenous peoples, including native administrative territorial formations (i.e. native counties and townships) and Indigenous villages, as well as lands categorized as ‘Territories of Traditional Nature Use’ be exempted from allocation as FEHs (V obshchetvennoy, Citation2015; see section ‘Response 3’, below). Other participants supported such protections, and the chair of the Ministry of Development of the Far East struck a group of experts to provide the appropriate wording for the draft law.

On 17 December 2015, RS(Ya)'s State Assembly confirmed the feedback that it would provide, if the draft law was accepted by the Duma on 18 December. The submission asserted that the draft federal law, as it stood, failed to fully take into account the interests of the Far East Federal District's population. The Duma accepted the draft law on 18 December at its first reading, and opened the 30-day period for proposing amendments and corrections. RS(Ya) immediately submitted 11 desired amendments (). These amendments included introducing a staged approach to implementing the law.Footnote5 From 1 October 2016 to 31 January 2017 only residents of the Federal Far Eastern District could request a FEH, and only within their region of residence.Footnote6 The programme opened to all Russia citizens on 1 February 2017. RS(Ya) also requested that those receiving a FEH be required to take up residence on the FEH if they wanted to retain that land after the five-year trial period. It questioned the justice of using a web-based process to allocate land, given the limited access to the Internet in many parts of the Far East Federal District. It proposed that certain types of land be exempt from allocation of FEHs: forest plantation lands and Territories of Traditional Nature Use. For other land categories, such as ‘places of traditional residence of indigenous peoples’Footnote7 and lands containing mineral deposits, it suggested other limitations and protections. Of the eleven amendments, eight were adopted in the revisions to the federal law.

Table 1. Initial amendments made by RS(Ya) to Draft Law on the Far East Hectare.

Meanwhile, the Civic Chamber of RS(Ya) provided a platform for further discussion, holding a public hearing in Yakutsk on 12 February 2016. More than 100 people attended. Based on the input received, RS(Ya)'s Civic Chamber prepared recommendations for a further amendment to the next version of the law, mostly to restrict the allocation of FEHs on lands designated for hunting (and important Indigenous activity) (Sakha Republic, Citation2016).Footnote8

RS(Ya) also prepared a contingency plan, should its proposals for amendments to the draft law not be accepted to a degree with which it was satisfied, identifying ways of scuttling or at least delaying the adoption of the law. Zhirkov noted that the FEFD had no constitutional basis: thus, the FEH law could be challenged on this account. The law's legitimacy in allowing the annexation of the lands of Indigenous peoples could also be questioned if necessary (Dal’nevostochnyy, Citation2016a). However, adoption into the FEH law of most of RS(Ya)'s proposed amendments obviated the need for such confrontational actions.

Response 2: encourage and enable early applications for FEHs from residents of Sakha Republic (Yakutia)

On 8 February 2016, in anticipation of Putin signing the FEH law, the head of RS(Ya)'s government created an Interdepartmental Working Group to prepare for the implementation of the law in the republic (Gur’eva, Citation2016). The staged approach to introducing the law (suggested by RS(Ya)), enabled residents of the FEFD to apply for FEHs within their home regions before the process was opened to other citizens of Russia. Egor Borisov, then head of RS(Ya), encouraged the people of RS(Ya) to take advantage of this opportunity (Egor Borisov, Citation2016). To ensure they were equipped to do so, the republican government launched a public information campaign, publishing explanatory articles in republican and local newspapers, distributing brochures and instructional materials on how to apply. It held public meetings to advertise the programme and answer questions, and staffed regional offices to provide information and assistance to locals applying for a FEH. Microspaces of information boards, meeting halls and offices were temporarily produced for this purpose.

The web-based application potentially posed spatial challenges to those having limited technology, and/or living in places with poor internet service, ‘putting Far Easterners on unequal footing with residents of large cities’ (Il Tumen, Citation2016). The majority of settlements in the Far East Federal District had internet service too slow to allow for their residents to compete equally with those of other regions in the first-come-first-served web-based application system. Indeed, only 67% of the settlements in RS(Ya) have access to internet (429 of 641 settlements), and although 97% of the republic's population has access, much of the bandwith in the rural areas is still only 256 kb/second (Prokop’ev, Citation2017). While RS(Ya) proposed that the law be amended to only allow hardcopy applications in areas with poor connectivity, the revisions to the federal law did not go this far, but did allow paper as well as internet applications. Multi-functional Centres for the Provision of Public Services (MFCs) served as spaces where a person interested in applying for a FEH could do so by either electronic or hardcopy application, with technical assistance. However, the MFCs exist only in the county-level (rayon/ulus) centres, thus providing only a partial solution to the inequality of access to the FEH programme experienced by rural residents.

Response 3: reduce the territory available in RS(Ya) for Far East Hectare allocation

Geographer Nicholas Blomley (Citation1994), among others, suggests a need to consider how space/place influence law as well as how law produces space. Law is contextual in time and space. The space of RS(Ya) as a jurisdiction contains Indigenous peoples and Sakha, which the federal and republican governments frame as dependent on, committed to, and deserving of governmental support for, the continued practice of ‘traditional activities’. As noted above, while a suite of legislation to produce spaces for such activities has been adopted at both the federal and republican level (Russian Federation, Citation2000, Citation2001; Sakha Republic, Citation1992, Citation2006), RS(Ya) has been especially active in the implementation of that legislation, to produce such ‘indigenous’ spaces in number and areal extent not replicated elsewhere in Russia.

Indigenous groups, faced already in many areas with loss of lands to expanding industrial development, immediately raised concerns about the FEH programme posing additional threat to their lands. One indigenous leader opined:

It was important to remove Indigenous lands from the FEH selection. Not just the obshchinaFootnote9 lands, many of which are not registered, but the Territories of Traditional Nature Use lands. These lands have legal status at the republican level. (Interview, Yakutsk, 7 August 2016)

The republican government supported this approach, and in October 2015 tasked its Standing Committee on Land Relations, Natural Resources and Ecology to pursue the full registration of TTNUs (Dal’nevostochnyy, Citation2016b). It launched an aggressive programme to do so, with dedicated finances: in its 2016 budget, RS(Ya) allocated 18 million rubles for this purpose. By the end of 2016, 35 TTPS were fully surveyed and registered, at a cost of 17.3 million rubles (Gur’eva, Citation2016).

Republic power has been really helpful [in allowing for TTNUs to be created and registered to protect against the Far East Hectare] … They helped us, they gave us financial help, they helped us through the stages. Prior to this year, there were few examples of TTNUs being formed. They [the Republican government] had examples, they gave us their help. … In 2011 a TTNU was [created] in the Tyanya Township at a general meeting, but the documents were not fully formulated until this past year … (Interview, head of an Indigenous obshchina, Olekminsk, 22 August 2016)

The Far East Hectare came quickly; we needed to save our land. So registering TTNUSs became critical. The Minister of Property and Land Relations worked with us to establish these … We managed to consolidate the land, while the FEH law was still being considered – even though it went through very quickly. (Interview, Indigenous leader, Yakutsk, 25 May 2017)

Many credited the TTNUs with protecting indigenous territory from loss of land to FEHs, as a few quotes from interviews carried out in the (Indigenous) Evenki village of Khatystyr indicate:

We don't have any real problem with this (the FEH) due to creation of TTNUs. (Indigenous administrator, Khatystyr, 18 May 2017)

It [the FEH law] doesn't affect us – our land is protected by a TTNU. Which is a big plus. (Head of an indigenous obshchina, Khatystyr, 20 May 2017)

Response 4: allocate additional lands to RS(Ya) citizens (the ‘Yakut Hectare’)

RS(Ya) responded to the FEH programme in yet another way, creating through law its own parallel programme, colloquially called the ‘Yakut Hectare’. This programme further limited the land available to ‘outsiders’ by expanding allocations to RS(Ya) residents. If the sequestration of lands into TTNUs addressed the concerns of Indigenous peoples by means of formalizing and increasing a type of space legislated for the protection of these peoples’ ‘traditional’ activities, the ‘Yakut Hectare’ programme provided for the expansion of Sakha/Yakut spaces. Accessible only to residents of RS(Ya), it enables individuals pursuing livestock husbandry and agriculture to apply for free use of substantial tracts of land, including for pasturing livestock and haying. The main beneficiaries are Sakha horse and cattle pastoralists. Land is granted for six years (i.e. one more year than provided by the FEH Law) (). Originally envisioned as supported by the passage of a distinct law, the Yakut Hectare programme ultimately was accomplished by modification of RS(Ya)'s Land Codex, on 24 November 2016 (Federova, Citation2016; Sakha Republic, Citation2016).

Table 2. Attributes of the Far East Hectare and Yakut Hectare Laws.

Response 1, Round 2: continued work to shape related federal legal initiatives to benefit RS(Ya)

Work on changes to the Federal Law 119-F3 (on FEHs) began almost immediately upon its passage. Again, RS(Ya) played an active role. On 17 June 2016, a half-month after the FEH law came into effect, RS(Ya)'s State Assembly sent a request for changes to the Duma (Zhirkov, Citation2016) Key changes sought included:

confirming the right of regions to establish the rules and conditions for allocating more than one hectare of land to an applicant, in accordance with regional law (thus ensuring RS(Ya)'s right to pursue the development of its ‘Yakut Hectare’ programme);

confirming the right of the legal (representative) body, rather than executive body, of regions to determine lands unavailable for FEH allocation near settlements, and removing the provision that this must be done in consultation with federal authorities;

requiring the applicant to live (i.e. register residency) on the allocated FEH for a minimum of five year in order to be eligible to apply prolongation of the rights to that allotment (an amendment it had previously proposed that had not been accepted);

limiting the authority of lower levels of power to allocate forest lands (while maintaining these for other lands);

expanding some time limits stated in the original law to favour those living in remote places who might be otherwise caught unware about provisions that could diminish their rights (Zhirkov, Citation2016).

RS(Ya) also adjusted its own legal code to cohere with the federal law. For instance, once the amendment was adopted on locating the right to exclude territory from FEH allocation with the region, the RS(Ya) drafted its own law ‘On the territories of the Republic, within whose boundaries land plots cannot be provided for free use’ (Narodnoe, Citation2018; Sakha Republic, Citation2018). The republican government has continued to oppose suggestions made by the federal Ministry of Eastern Development to open up hunting lands for allocation, in order to increase the territory available for FEHs (Prokop’ev, Citation2017).

Discussion

Representatives of the government of RS(Ya) for the most part viewed the passage of the FEH law as inevitable. While RS(Ya)'s populace appeared to be overwhelmingly opposed to the introduction of this federal law, the RS(Ya) government early indicated its general support. However, averse to accept a federal law that in its early form threatened the territorial interests of the populace in many ways and provoked their strong protest, RS(Ya)'s government actively worked to shape the federal law to better suit its geography and population's needs and desires. It did so in multiple ways that we outlined above as responses, which demonstrate the region's agency in using the niches provided by federal law to its optimum, and in enlarging those niches for the advantage of the own populace where possible. It proposed amendments to ensure the interests of its populace in both receiving FEHs themselves and in being protected from the allocation of FEHs on their territories to ‘outsiders’, when such would likely erode their ability to pursue their livelihoods. Due mostly to RS(Ya)'s proposals, the grounds for refusing a citizen an FEH expanded from 10 (at first reading) to 25 (Prokop’ev, Citation2017). RS(Ya) also sought changes to where key decisions regarding lands would be made, fighting for regions’ authority to identify pilot areas for the FEH law, to determine what lands would be unavailable for allocation, and to have the authority to allocate FEHs outside of forest lands. RS(Ya) also adapted its own law to enable its residents to more fully benefit from the land allocation and to simultaneously remove lands from allocation to outsiders (via the Yakut hectare). And it implemented existing federal and republican law on TTNUs to remove significant territories of the republic from the FEH programme.

Conclusion

In this example, we see an on-going navigation of centre-region relations in the Russian Federation over the governance of territory, as negotiated through the drafting and implementation of federal and regional law. Democratization of the legislative process, if constrained, has enabled the regions of Russia to assert greater agency in pursuing their sometimes diverging agendas in producing the spaces of their territories. According to the Russian Constitution all regions have such an option. While such agency is partial, we suggest it is greater than often recognized in Anglophone literature, a literature indeed that pays sparse attention to Russia's legal geographies. Niches within which to influence the production of space in the Russian Federation include opportunities for active involvement in the co-production of federal laws that may (re)produce space, as well as in the interpretation and implementation of these laws at the local level. Some regions of Russia, such as RS(Ya), actively use the legislative and legislated spaces, not to oppose federal policies and programmes, but to mould them to local conditions, and thus to assert a level of autonomy within the Federation. Opting for the approach of modifying federal programmes from within through the use of law rather than opposing these programmes has facilitated this region's success in its negotiation of state-region relations. We have demonstrated how the region followed a strategy of making use of niches of agency wherever the federal law allowed, and also, through navigating diverse legislative spaces, of enlarging those niches to its own advantage. Such an approach allows both the centre and the region to retain their reputations as powerful agents among their populace: the centre demonstrates control over its entire territory, while the region shows that it is able to influence central policies, within a legitimated system of co-producing and implementing laws, to the benefit of its own population.

Acknowledgements

We thank the many people who agreed to spend time with us, answering our questions and discussing the unfolding situation regarding land rights and issues in Sakha Republic (Yakutia). We greatly appreciate the constructive comments provided by Professor Mark Boyle and one anonymous reviewer on the initial draft of this paper. This research was supported by SSRHC grant 435-2016-0702, NORRUS grant 257644/H30, RFBR grant 18-59-11011 and AKA grant 314471. The usual disclaimers apply.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes on contributors

Gail Fondahl is a cultural and legal geographer. Her research focuses on indigenous territorial rights in the Russian North. Fondahl has carried out fieldwork in Eastern Siberia since the early 1990s.

Viktoriya Filippova is Senior Researcher at the Arctic Researches Department, with interests in the settlement and demography of Indigenous peoples, their traditional use of natural resource, as well as historical geography, GIS technologies and climate change.

Antonina Savvinova is an Associate Professor with research interests in GIS, remote sensing, natural resourses management of Indigenous peoples of the North, and sustainable development of the Northern territories.

Aytalina Ivanova specializes in Arctic and Indigenous peoples’ legislation, with a focus on legal anthropology. She has worked and published on the relations between extractive industries and indigenous and local populations in various regions of the Russian Arctic and Norway.

Florian Stammler has worked for 20 years in the Russian Arctic with local and indigenous people, and more recently in Finland and Norway. His publications focus on the encounter between extractive industries and local livelihoods, human-animal relations, youth wellbeing and oral history. He is the author of ‘Reindeer Nomads Meet the Market’, the last ethnography of nomads on the Siberian Yamal Peninsula before the advent of large-scale gas industry.

Gunhild Hoogensen Gjørv research examines tensions between perceptions of state and human security in a variety of contexts, with a particular focus on the Arctic. She has led numerous projects investigating the relationships between state, extractive industries, and northern/Arctic peoples.

ORCID

Gail Fondahl http://orcid.org/0000-0003-4287-1288

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 On 4 November 2018, two more regions were added to the FEFD.

2 The RS(Ya) government proposed changes to the draft federal law on the FEH (Response 1); it also is actively pursuing discussions of necessary amendments to a follow-up draft federal law that would introduce changes to the initial FEH law (see section ‘Response 1, Round 2’).

3 The Civic Chamber (Obshchestvennaya palata) enables representatives of professional and public organizations the opportunity to suggest modifications to a draft law during its ‘null-reading’ phase. Civic Chambers at both the national and republican level serve as a platform for dialogue, a place for negotiations and working out common solutions that take into account the opinion of the varied stake-holders. They also provide for consultation between the Government and the Parliament, prior to the formal introduction of a draft law, which can facilitate and expedite the legislative process.

4 Golomarëva chairs RS(Ya)'s Standing Committee on Issues of Indigenous Numerically Small Peoples and the Arctic, as well as serving as a member on its Standing Committee on Land Relations, Natural Resources and Ecology.

5 Initially RS(Ya) sought to defer the opening of the programme to all Russian citizens until 2018 (Gunaev, Citation2016).

6 Prior to this was a stage in which the project was ‘trialed’ in one pilot region in each of the nine regions of the FEFD.

7 A ‘List of Traditional Places of Residence and Economic Activities of Indigenous Numerically Small Peoples of the Russian Federation’ was confirmed by Order of the Government of the Russian Federation (No.631-r) on 2 May 2009 (and edited on 29 December 2017). These differ from ‘Territories of Traditional Nature Use’ (described under section ‘Response 3’, below).

8 The agency of citizens to influence the law through public engagement and actions (editorial writing, protests), and how this varies with the disposition of the regional government to pursue its agenda vis a vis the centre, deserves further exploration. The effectiveness of citizen action may correlate positively with the ‘strength’ (assertiveness) of the regions of the Russian Federation in which they reside.

9 An obshchina (‘tribal community’) is a collective of indigenous persons who carry out ‘traditional activities’, and receive (limited) usufruct rights to a territory on which to do so.

References

- Argounova-Low, T. (2004). Diamonds: A contested symbol in the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia). In E. Kasten (Ed.), Properties of culture - Culture as property: Pathways to reform in post-Soviet Siberia (pp. 257–265). Berlin: Dietrich Reimer.

- Balzer, M. (2016). Indigeneity, land and activism in Siberia. In A. C. Tidwell & B. X. Zellen (Eds.), Land, indigenous people and conflict (pp. 9–27). London: Routledge.

- Balzer, M. M., & Vinokurova, U. A. (1996). Nationalism, interethnic relations and federalism: The case of the Sakha Republic (Yakutia). Europe-Asia Studies, 48(1), 101–120. doi: 10.1080/09668139608412335

- Billé, F., Delaplace, G., & Humphrey, C. (2012). Frontier encounters: Knowledge and practice at the Russian, Chinese and Mongolian Border. Cambridge, UK: Open Book.

- Blomley, N. (1994). Law, space and the geographies of power. New York, NY: Guilford.

- Braverman, I., Blomely, N., Delaney, D., & Kedar, A. (2014). Introduction. Expanding the spaces of law. In I. Braverman, N. Blomley, D. Delaney, & A. Kedar (Eds.), The expanding spaces of law. A timely legal geography (pp. 1–29). Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Crate, S. (2006). Cows, kin and globalization. An ethnography of sustainability. Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira Press.

- Dal’nevostochnyy. (2016a, February 9). Dal’nevostochnyy gektar: chto delal Parlament Yakutii [The Far East Hectare: What the Parliament of Yakutia did]. Yakutia.info. Retrieved from http://yakutia.info/article/173834

- Dal’nevostochnyy. (2016b, February 9). ‘Dal’nevostochnyy gektar’: rabota prodolzhaentsya [‘The Far East Hectare’: Work continues]. Gosudarstvennoe sobranie (Il Tumen) Respubliki Sakha (Yakutiya). Retrieved from http://iltumen.ru/content/%C2%ABdalnevostochnyi-gektar%C2%BB-rabota-prodolzhaetsya

- Dal’nevostochnyy. (2016c, February 9). ‘Dal’nevostochnyy gektar’ v retrospective [‘The Far East Hectare’ in restropsective]. Gosudarstvennoe sobranie (Il Tumen) Respubliki Sakha (Yakutiya). Retrieved from http://iltumen.ru/content/«dalnevostochnyi-gektar»-v-retrospektive

- Delaney, D. (2015). Legal geography I: Constitutivities, complexities, and contingencies. Progress in Human Geography, 39(1), 96–102. doi: 10.1177/0309132514527035

- Delaney, D. (2017). Legal geography III: New worlds, new convergences. Progress in Human Geography, 41(5), 667–675. doi: 10.1177/0309132516650354

- Egor Borisov. (2016, October 28). Egor Borisov: Yakutyane dolzhny uspet’ poluchit’ svoi ‘dal’nevostochnyy’ gektary do 1 fevralya [Yakutians should have time to receive their ‘Far East’ Hectare before 1 February’]. YaSIA: Novost’ Yakutska i Yakutii. Retrieved from http://ysia.ru/glavnoe/egor-borisov-yakutyane-dolzhnyuspet-poluchit-svoi-dal’nevostochnyy-gektary-do-1-fevralya

- Federova, E. (2016, December 2). ‘Dal’nevostochnyy gektar’ i ‘yakutskiy gektar’ — v chem otlichie? [‘The Far East Hectare’ and the ‘Yakut Hectare’ – How do they differ?]. Ekho stolitsy No.47 (2573). Retrieved from https://222.exo-ykt.ru/articles/02/537/17097/

- Fondahl, G., Lazebnik, O., & Poelzer, G. (2000). Aboriginal territorial rights and the sovereignty of the Sakha Republic. Post-Soviet Geography and Economics, 41(6), 401–417. doi: 10.1080/10889388.2000.10641150

- Fondahl, G., Lazebnik, O., Poelzer, G., & Robbek, V. (2001). Native ‘land claims’, Russian style. The Canadian Geographer/Le Géographe Canadien, 45(4), 545–561. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0064.2001.tb01501.x

- Fondahl, G., & Poelzer, G. (2003). Aboriginal land rights in Russia at the beginning of the twenty-first century. Polar Record, 39(309), 111–122. doi: 10.1017/S0032247402002747

- Gavrileva, A. (2016). Presentation to 16th Session of UN Forum on Indigenous Issues, New York City. (Transcript in possession of corresponding author).

- Gilbert, J. (2007). Nomadic territories: A human rights approach to nomadic peoples’ land rights. Human Rights Law Review, 7(4), 681–716. doi: 10.1093/hrlr/ngm030

- Gunaev, E. A. (2016). K probleme opredenleniya statusa ‘korennykh narodov’: pretsedent Respubliki Sakha (Yakutia). [On the problem of determining the status of ‘Indigenous peoples’: The precedent of the Sakha Republic (Yakutia)]. Vestnik Instituta komleksnykh issledovaniy aridnykh territoriy, 33(2). Retrieved from https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/k-probleme-opredeleniya-statusa-korennyh-narodov-pretsedent-respubliki-saha-yakutiya

- Gur’eva, S. M. (2016, September 22). Ob obespechenii prav na iskonnuyu sredu obitaniya, traditsionnogo obraza zhizni, khozyaystvovaniya i promysla korennnykh malochislennykh narodov Severa Respubliki Sakha (Yakutia) [On guaranteeing the right to ancestral lands, traditional way of life and economic activities and the hunt of the Indigenous numerically small peoples of the North of the Sakha Republic (Yakutia)]. Proekt. Doklad ministra po razvitiyu institutov grazhdanskogo obshchestva Respubliki Sakha (Yakutia) S.M. Gur’evoy na zasedaniya koordinatsionnogo Arkticheskogo Soveta pri Glave Respubliki Sakha (Yakutia). Retrieved from https://arktika.sakha.gov.ru/files/front/download/id/1402910

- Heleniak, T. (2010). Population change in the periphery: Changing migration patterns in the Russian North. Sibirica, 9(3), 9–40. doi: 10.3167/sib.2010.090302

- Il Tumen. (2016, December 8). Il Tumen proyavlayet initsiativu [Il Tumen takes the initiative]. AKMNS RS(Ya). Retrieved from http://yakutiakmns.org/archives/5889

- Ivanova, A., & Stammler, F. (2017). Mnogoobrazie upravlyaemosti prirodnymi resursami v Rossiyskoy Arktike [A diversity of ways of governing natural resources in the Russian Arctic]. Sibirskie Istoricheskie Issledovavniya, 4, 210–225. doi: 10.17223/2312461X/18/12

- Kedar, A. (2014). Expanding legal geographies. A call for a critical comparative approach. In I. Braverman, N. Blomley, D. Delaney, & A. Kedar (Eds.), The expanding spaces of law. A timely legal geography (pp. 95–119). Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Kryazhkov, V. A. (2010). Korennye Malochislennye Narody Severa v Rossiyskom Prave [ Indigenous numerically small peoples of the north in Russian law]. Moscow: Norma.

- Kryazhkov, V. A. (2013). Development of Russian legislation on northern indigenous peoples. Arctic Review on Law and Politics, 4(2), 140–155.

- Kuhrt, N. (2012). The Russian Far East in Russia’s Asia policy: Dual integration or double periphery? Europe-Asia Studies, 64, 471–493. doi: 10.1080/09668136.2012.661926

- Laruelle, M. (2015). Russia’s Arctic strategies and the future of the far north. London: Routledge.

- Lo, B. (2009). Axis of convenience: Moscow, Beijing, and the new geopolitics. London: Chatham House.

- Miting. (2016, March 17). Miting protiv zakona o ‘dal’nevostochnom gektare’ sobral bole tysyachi chelovek [A meeting against the law on ‘The Far East Hectare’ brought together more than a thousand persons], Yakutsk.ru. Retrieved from http://yakutsk.ru/news/society/miting_protiv_zakona_o_dalnevostochnom_gektare_sobral_bolee_tysyachi_chelovek/

- Narodnye. (2018, February 21). Narodnye deputaty prinyali tablitsy popravok v zakon ‘O territoriyakh respubliki, v granitskah kotorykh zemel’nye uchastki ne mogut byt’ predostavleny v bezvozmezdnoe pol’zovanie’ [The People’s Deputies adopted a table of amendments to the law ‘On the territories of the republic, within the boundaries of which land allotments may not be allocated for free use’]. Gosudarstvennoe sobranie (Il Tumen) Respubliki Sakha (Yakutiya). Retrieved from http://iltumen.ru/content/narodnye-deputaty-prinyali-tablitsu-popravok-v-zakon-%C2%ABo-territoriyakh-respubliki-v-granitsak

- Prokop’ev, V. M. (2017). O rabote po zakonoproektu o ‘dal’nevostochnom gektare’ i ego realizatsii na territorii Respubliki Sakha (Yakutia) [On the work on the draft law on ‘The Far East Hectare’ and its realization on the territory of the Sakha Republic (Yakutia)], Analithcheskiy Vestnik 29(685). ‘Sovremennoe sostyanie i perspektivy sotsial’no-ekonomicheskogo razvitiya Reapubliki Sakha (Yakutiya)’, pp. 43–54. Moscow: Analytical Material of the Council of the Federation.

- Russell, R. (2015). Russia’s constitutional structure. Federal in form, unitary in function. European Parliamentary Research Service. Retrieved from http://www.europarl.europa.eu/thinktank/en/document.html?reference=EPRS_IDA(2015)569035

- Russian Federation. (1993). The constitution of the Russian Federation. English translation available at http://www.constitution.ru/en/10003000-01.htm

- Russian Federation. (2000, July 20). Ob obshchikh printsipakh organizatsii obshchin korennykh malochislennykh narodov Severa, Sibiri i Dal’nego Vostoka Rossiyskoy Federatsii [On the general principles for organizing tribal communities of the indigenous numerically small peoples of the North, Siberia and Far East of the Russian Federation], Russian Federal law No104-F3.

- Russian Federation. (2001, May 7). O territoriyakh traditsionnogo prirodopol’zovaniya korennykh malochislennykh narodov Severa, Sibiri i Dal’nego Vostoka Rossiyskoy Federatsii [On territories of traditional nature use of the indigenous numerically small peoples of the North, Siberia and Far East of the Russian Federation], Federal Law No 49-F3.

- Russian Federation. (2016, May 1). Ob osobennostyakh predostavleniya grazhdanam zemel’nykh uchastkov, nakhodyashchikhsya v gosudarstvennoy ili munitsipal’noy sobstvennosti i raspolozhennykh na territoriyakh sub”ektov Rossiyskoy Federatsii, vkhodyahshikh v sostav Dal’nevostochnogo federal’nogo okruga, i o vnesenii izmeneniy v otdel’nye zakonodatel’nye akty Rossiyskoy Federatsii [On the specifics of granting to citizens land plots in state or municipal ownership, located in the territories of the constituent entities of the Russian Federation within the Far East Federal District, and on the introduction of changes to individual legal acts of the Russian Federation], Federal Law N o 199-F3.

- Sakha Republic. (1992, December 23). O kochevoy rodovoy obshchiny malochislennykh narodov Severa [On nomadic clan tribal communities of the numerically small peoples of the North]. Law N 1278-XII.

- Sakha Republic. (2006, July 13). O territoriyakh traditsionnogo prirodopol’zovaniya i traditsionnoy khozyaystvennoy deyatel’nosti korennykh malochislennykh narodov Severa Respubliki Sakha (Yakutiya) [On territories of traditional nature use and traditional economic activities of the indigenous numerically small peoples of the North of the Sakha Republic (Yakutia)], Law N 370-З N 755-III.

- Sakha Republic. (2016, November 24). O vnesenii izmeneniy v Zemel’nyy kodeks Respubliki Sakha (Yakutia) [On the introduction of changes to the Land Codex of Sakha Republic (Yakutia)], Law N 1757-3 N 1071-V.

- Sakha Republic. (2018, February 21). O territoriyakh respubliki, v granitskah kotorykh zemel’nye uchastki ne mogut byt’ predostavleny v bezvozmezdnoe pol’zovanie [On the territories of the republic, within the boundaries of which land allotments may not be allocated for free use], Law N 1972-3 N 1503-V.

- Severnyy. (2016, July 29). Severnyy ledovtyy okean budet pleskat’sya u Yakutii [The Arctic Ocean will splash out of Yakutia], Vesti Olekmy 31, p. 2; continued in 32, p. 6.

- Shcherbakov, D. (2018, April 8). Pyat’ voprosov k ‘dal’nevostochnomy gektaru’. [Five questions about the ‘Far East Hectare’]. Gosudarstvennoe sobranie (Il Tumen) Respubliki Sakha (Yakutiya). Retrieved from http://iltumen.ru/content/pyat-voprosov-k-%C2%ABdalnevostochnomu-gektaru%C2%BB

- Sir. (2016, June 15). ‘Sir’: y yakutskikh konevodov i olenevodov mogut otnyat’ zemli [‘Land’: Yakut horse herders and reindeer herders may take land], Yakutiya.info. Retrieved from http://yakutia.info.article.175575

- Stammler, F. (2005). Reindeer nomads meet the market. Muenster: Litverlag.

- Stammler, F., & Ivanova, A. (2016). Resources, rights and communities: Extractive mega-projects and local people in the Russian Arctic. Europe-Asia Studies, 68, 1220–1244. doi: 10.1080/09668136.2016.1222605

- Stenogramma. (2015, December 17–18). Stenograma 20 (ocherednogo) Plenarnogo zaselaniya Gosudarstvennogo Sobraniya (Il Tumen) Respubliki Sakha (Yakutia) [Transcript of the 20th (regular) Plenary Meeting of the State Assembly (Il Tumen) of the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia)]. Retrieved from http://iltumen.ru/sessions?page=1

- Takakura, H. (2015). Arctic pastoralist Sakha. Ethnography of evolution and microadaptation in Siberia. Victoria, Australia: Trans Pacific Press.

- Tichotsky, J. (2000). Russia’s diamond colony: The Republic of Sakha. Amsterdam: Harwood Academic.

- Vitebsky, P. (2006). The reindeer people: Living with animals and spirits in Siberia. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin.

- Vladimir. (2016, May 5). Vladimir Prokop’ev razyasnil osnovnye polozheniya prinyatovo zakona o ‘dal’nevostochnom getkare’ [Vladimir Prokop’ev explained the main provisions of the law on ‘The Far East Hectare’]. Gosudarstvennoe sobranie (Il Tumen) Respubliki Sakha (Yakutiya). Retrieved from http://iltumen.ru/content/vladimir-prokopev-razyasnil-osnovnye-polozheniya-prinyatogo-zakona-o-%C2%ABdalnevostochnom-gektar

- V obshchestennoy. (2015, December 2). V Obshchestennoy palate Rossiyskoy Federatsii obsudili zakonoproekt o ‘dal’nevostochnom getkare’ [The draft law on the ‘Far East Hectare’ was discussed in the Civic Chamber]. Ministry of Investment and Land and Property Policy of Khabarovskiy Territory. Retrieved from https://mizip.khabkrai.ru/events/Novosti/79

- Yakutskiy. (2016, November 1). ‘Yakutskiy” gektar: V respublike fermery smogut poluchit do 900 ga sel’khozzemel’ [The ‘Yakut’ hectare: Farmers in the Republic will be able to receive up to 900 ha of agricultural land]. YaSIA: Novost’ Yakutska i Yakutii. Retrieved from http://ysia.ru/glavnoe/yakutskij-gektar-v-respubliki-fermery-smogut-poluchit-do-900-ga selkhozzemel/

- Zhirkov, A. N. (2016). O zakonodatl’noy initsiative Gosudarstvennogo Sobraniya (Il Tumen) Respubliki Sakha (Yakutia) [On legisltative initiatives of the State Assembly (Il Tumen) of the Saha Republic (Yakutia)], Document No.1gs-2511, 17 June 2016) (Copy of letter in possession of authors).