ABSTRACT

This paper opens a special issue (SI) commemorating the contributions of Ronan Paddison (1945–2019), founder and original Editor-in-Chief of Space and Polity. It outlines Paddison’s academic accomplishments before introducing the pieces that follow. It narrates Paddison as scholar, teacher, theorist and critic based on reading a student geographical magazine, the Drumlin, ‘published’ annually 1955–2009. This medium allows glimpses of Paddison as a ‘radical geographer’ nourishing eclectic versions of political and urban geography. The paper raises signposts for many of the concerns, to do with Paddison’s conceptualizing, practising and instructing about ‘space and polity’, covered by the SI as a whole.

Introducing this special issue (SI)

This special issue (SI) of Space and Polity offers an academic commemoration of Ronan Paddison (1945–2019), the founder and long-time Editor-in-Chief of this journal, who died on 8 July 2019 (see ). Ronan held an intense, far-sighted grasp of the disciplinary subfield of political geography and, more broadly, of human geography whenever it touched upon matters of politics or abutted any domains comprising what sometimes gets called ‘political science’ (including political sociology, political anthropology, political theory, and more).Footnote1 He held the conviction that a specialist journal should be born with the express purpose of exploring how space – in all its guises socially produced through places, landscapes, environments, locations, territories, boundaries, settlements, and more – and politics – in all its dimensions folded into states, governments, governance, elections, constitutions, ideologies, nationalisms, regionalisms, localisms, and more – become inextricably scrumpled up together. And thus was born Space and Polity, shaped unequivocally by Ronan, as Mark Boyle discusses in his piece that follows (Boyle, Citation2020).

Figure 1. Ronan Paddison, c.1972, when first appointed Lecturer in Geography at the University of Glasgow (Source: courtesy of Lesley Paddison).

Ronan was an exemplary academic: an active researcher, a critical scholar and a committed educator, as well as being someone who believed that high-quality academic work could make a difference to processes and people in the ‘real’ world. He made numerous leading contributions to the overall field of human geography, being internationally renowned for his work in the disciplinary subfields of political geography (reaching across towards political science) and urban geography (reaching across into the interdisciplinary field of urban studies). He made specific interventions in a range of conceptual, methodological and substantive domains, shifting perspectives and prompting debates. He was passionate in his teaching and supervising, whether introducing undergraduates to the complexities of urban assemblages and political systems, or thoughtfully mentoring postgraduates through to successful PhD completion (on an impressive range of subjects). He was a wonderful colleague, as I know personally, always ready to take the strain of high teaching loads or laborious administrative responsibilities, as well as being central to the strategic directions taken by Geography as a subject area at the University of Glasgow over many years.

The present SI is designed to put flesh on the bones of this appraisal, and in so doing to provide a sustained retrospective and evaluation of an overall academic life. With honourable exceptions such as the Geographers Biobibliographic Studies series (Bloomsbury Collections, CitationVarious years), too rarely do we – academics in our various intellectual and institutional hidey-holes – stop properly to take stock of individual academic lives: of their contributions, published and otherwise, and wider textures of engagement, enablement and exchange. Too little do we reflect upon what exactly someone has accomplished in terms of: adding to extant funds of knowledge, theory and practice; guiding, encouraging and inspiring others; leading, supporting or enhancing initiatives within the academy; or reaching out into worlds beyond the academy to shape policies, debates and activisms. Too infrequently do we inventory and assess the research and the scholarship, the writing and the presenting, the lecturing and the teaching, the administering and the ‘politiking’, the editing and the refereeing, or the mentoring, the supervising, the guiding and the sympathetic ear. Too unattuned are we, notwithstanding recent attention to the ‘geographies of science’ (e.g. Livingstone, Citation2003; Naylor, Citation2005a, Citation2005b), to the multiple spaces in, through and across which these many features of an academic life get played out: countless worldly ‘fields’ of inquiry, computer laboratories, conference halls, lecture theatres, meeting suites, staff offices, common rooms, corridors, coffee-shops and public squares or bars.

The challenge for this SI is to overcome these lacunae in the specific case of Ronan Paddison. An initial move in this direction occurred at an event, called ‘A Commemoration of His Academic Life’ held on 22 November 2019 in the School of Geographical and Earth Sciences, University of Glasgow, the department and institution that Ronan served with such distinction for much of his salaried career (1972–2010).Footnote2 By invitation, various of the contributions to this event, ranging from full presentations through to off-the-cuff reminiscences, have now been reworked for this SI.Footnote3 The upshot is to provide what we, the editors of this SI, hope will be regarded as a satisfying encounter with what we call ‘Paddison geographies’: an encounter precisely not meant to be hagiographic, elevating Ronan to academic sainthood, deserved as that might be, but rather an encounter supposed to look beneath surfaces, to delve beyond platitudes, and thereby to venture exegesis, evaluation and even, where appropriate, critique.

Briefly to encompass the overall shape of this SI, then, it commences with this introduction, offering what I acknowledge might be construed as a somewhat ‘oblique’ opening up of certain aspects of Ronan the academic, as well as appending both a selective timeline of Ronan’s life and academic career () and a consolidated list of Ronan’s publications (Appendix 2). The SI then proceeds into a weightier assessment by Boyle (Citation2020) of Ronan’s contributions to political geography, political science and the establishment, and indeed to the very spirit and purpose, of this journal Space and Polity. To underline a point already hinted, this assessment should be run alongside an appreciation of Ronan’s contributions to urban geography, urban studies and his long-term involvement with the journal Urban Studies, ones acknowledged in greater detail elsewhere (Cumbers & Philo, Citation2019). A pertinent but related aside is that Ronan was also actively involved in encouraging the foundation and then co-editing of another journal, the Romania-based Journal of Urban and Regional Analysis, as recounted in another tribute (Ianos, Citation2019). What might be added in this respect, as other contributions to this SI make abundantly plain, is the extent to which Ronan simultaneously urbanized the political and politicized the urban, meaning that it is somewhat arbitrary ever to tug the two – the political and the urban – apart when discussing Ronan’s oeuvre. His particularly distinctive niche was to fashion versions of urban-political or political-urban geography, always drawing at one and the same time inspiration from the wider fields of political science, urban studies and their myriad philosophical, methodological and empirical articulations.

The next seven pieces in the SI alight upon more focussed conceptual and substantive manoeuvres within Ronan's oeuvre: Gordon MacLeod on perhaps Ronan's most distinctive offering, with complex philosophical and empirical twists, in the shape of ‘the fragmented state' (MacLeod, Citation2020); Charles Pattie on Ronan’s dabbling with both fiscal and electoral geography, the latter deploying statistical methods to expose the grubby politics of constituency ‘redistricting' (Pattie, Citation2020); Steven Miles on Ronan's early recognition of the need to interrogate and critique ‘culture-led urban regeneration’ (Miles, Citation2020); Vee Pollock on how the culture-cities axis morphed for Ronan into concerns about public art and urban politics (Pollock, Citation2020); John McKendrick on Ronan's brush with attempts to measure, map, interpret and draw inferences from the construct ‘quality of life’ (McKendrick, Citation2020); Lazaros Karaliotas on Ronan's remarkably prescient late work on post-politics and ‘the post-political city’ (Karaliotas, Citation2020); and Emma Laurie and Chris Philo on the relatively marginal but intriguing early statements by Ronan (and co-authors) about ‘the Arab city' or even ‘the post-colonial city' (Laurie & Philo, Citation2020). Some features of Ronan’s scholarship are admittedly not touched upon at all directly, notably geographies of planning, governance, public administration, retailing, education and housing. What all these contributions nonetheless underscore is the dazzling range of political and urban contexts across the globe with which Ronan was familiar, spanning far beyond his beloved Glasgow, even as this great deindustrialising, old-‘socialist’ city remained a touchstone never too distant from his thoughts. To be sure, Ronan was no ‘parochial’ political or urban geographer: the wider world was way too enticing for that to be the case.

The two pieces that then follow concentrate on the more subtle or intangible textures of Ronan’s academic life, taking us beyond the ‘staged’ interventions of publication and presentation – the spaces of written text and conference venue – towards what Ronan added in a more behind-the-scenes capacity. Kirsi Kallio teases out something of the copious, incisive and generous editorial labour that Ronan undertook unstintingly throughout his career (Kallio, Citation2020), while John Briggs digs into the many, often selfless, ways in which Ronan served his department in Glasgow as educator – teaching many courses, classes and fieldclasses – and as leader, manager and administrator striving always to haul Geography at Glasgow, never himself, into the most favourable of positions (Briggs, Citation2020).

Finally, this SI carries a composite piece gathering together shorter reflections authored by individuals who were supervised by Ronan for their doctoral studies – David Beel, John Crotty, Iain Docherty, Jim McCormick, Norman Rae and Derek Stewart – that all, in one way or another, evoke the deep significance of Ronan’s example, his learning, his wisdom and his humanity, empowering them to feel that they did have a ‘place’ in the hallways of academe, a voice worth hearing, with an ever-constant support, Ronan himself, to hold them up or push them forward (Beel et al., Citation2020). Additonally, their accounts do tell about places – stone staircases, cluttered offices, restaurants and bars, off-campus meeting-places – and their centrality to the entwined academic and personal histories that they all shared with Ronan.

Ronan from the pages of Drumlin

What I propose to offer for the remainder of my own contribution is a ‘sideways’ introduction to Ronan the academic – as scholar, researcher, educator, supervisor and inspiration, aspects of which are unpacked more fully in the contributions that follow below – born of my familiarity with a ‘journal’ called Drumlin, in which Ronan regularly featured in one guise or another from the early-1970s to the late-2000s. The Drumlin – or The Drumlin as it was initially known, on account of the main University of Glasgow campus being build atop a sizeable drumlin in the city’s West End – was a student-led geographical ‘journal’ produced annually by undergraduate students studying in the (variously titled) Department of Geography at Glasgow from 1955 through, almost but not quite continuously, to 2009, the Department’s Centenary Year.Footnote4 Elsewhere, I have reflected at length on Drumlin as this fascinating archive – perhaps unique in both its longevity, lasting over 50 years, and sheer volume of student writings, drawings, photographs and more – which I cast as disclosing a hybrid or ‘middle-level’ form of geographical knowledge production where ‘official’ academic geography (represented by teaching staff and the wider canon of geographical literature) is refracted through its reception, re-interpretation and occasional repudiation by undergraduate students (Bruinsma, Citation2020; Philo, Citation1998a). Glasgow staff provided Drumlin student editors with financial support and encouraged students to get involved or to author articles; staff occasionally contributed their own writings in the shape of mini-academic papers, notices about retiring colleagues (e.g. Paddison, Citation2001 [on retirement of Alastair Morrison]), reminiscences about the department in past eras, and the like; while student offerings frequently listed, mentioned or (gently) lampooned staff members, as well as caricaturing them in pen portraits, cartoons, collages or ‘doctored’ photographs. From the viewpoint of 2020, the humour in some earlier editions of Drumlin may strike as awkward, lapsing occasionally into caricatures and even stereotypes that might now raise objections for displaying casual classism, sexism, ethnocentricism and even ‘racism’.Footnote5

Ronan, fact and fiction in Drumlin

Unsurprisingly, Ronan was a not uncommon presence in the pages of Drumlin, as himself a contributor and, on rather more occasions, as someone discussed or drawn by students. In fact, so frequently did he appear that a whole article was dedicated to ‘Paddison thru’ the pages’, a review in 1998 (when Ronan was appointed Head of Department) of past issues ‘where Ronan’s name appears with alarming regularity’ (Drumlin, Citation1998, p. 26). Initially, sightings of Ronan in Drumlin were merely factual: ‘We welcome Dr. Paddison to the staff at Glasgow’ (Drumlin, Citation1973, p. 72), intoned one entry in a list of department news from 1973; ‘‘Social & Political Geography’ option – which ran for the first time in 1974–75 under Dr. R. Paddison’ (Drumlin, Citation1975, n.p.) was the next time he troubled the editors; and ‘Dr. Paddison returned in February 1977 from Central University, Caracus, Venezeula, where he was Visiting Lecturer’ (Drumlin, Citation1976a, n.p.) the next. This 1976–1977 issue also saw the first glimpse of what Ronan was beginning to bring to Glasgow Geography: positioned in the ‘Jogsok Top Ten’ (as in musical ‘chart hits’), ‘Ronan and the Hot Rods’ were performing ‘You’re More than a Number’ (Drumlin, Citation1976b, n.p.: ‘Jogsok’ being the Student Geographical Society), the likely implication being that Ronan was emphasising to students the deficiencies of a purely quantitative approach to geographical study, notwithstanding his own statistical capacities as reported in this issue by Pattie (Citation2020). Subsequently, as I will show, sightings of Ronan in Drumlin tended to be fuller and open to much more ‘interpretation’, such as in the article ‘Focus on Ronan Paddison’ (Drumlin, Citation1983, n.p.) where, alluding to his political geography teaching, his full name was recorded as ‘Ronan Ratzel-Paddison’ (although Ronan himself was well-aware of, and taught about, the deeply problematic legacy left by Friedrich Ratzel for academic human geography and in justifying mid-twentieth-century German expansionism).

Ronan was pictorially represented numerous times, making it on to the cover of Drumlin in 1993, as a leading band member of ‘Doctor Briggs Lonley Hearts Club Band’ (original spelling),Footnote6 with apologies to The Beatles, and then again in 2003 as a character from the U.S. satirical TV series South Park. On these covers he was merely one member of a collective ensemble, but on the cover of Drumlin, Citation1998 he took pride of place as a dashing James Bond figure above the film title caption ‘Geography Never Dies’. Two images from different issues then hint at student perceptions of what might be termed ‘the imagined geographies of Ronan’s past’, both positioning him as a ‘hippy’ at Woodstock embracing the spirit of what was once described in the pages of another important geographical magazine, Antipode, as ‘humanistic (lovin’) geography’ (Antipode, Citation1970, p. 3).

What might equally be termed ‘the mythological geographies of Ronan’ appeared, with one article entitled ‘The epic adventures of Ronan the Barbarian’, in which – echoing the then popular film character Conan the Barbarian – Ronan led an expedition ‘designed to unite the legendary, but long forgotten Fragmented State’ (Drumlin, Citation1986, p. 27). The latter reference was of course to Ronan’s pioneering book The Fragmented State (Paddison, Citation1983), the contents of which are subjected to sustained critical review in this collection (esp. MacLeod, Citation2020). ‘A tribute to Ronan’ on his standing-down from being Head of Department in 2002 added a further mythological layer, describing ‘[our] very own Russell Crowe look-like, Professor Ronan Paddison’ (Drumlin, Citation2002, p. 11), complete with an image of Ronan as Roman gladiator above the film title ‘Paddimus Maximus MCMXCVIII-MMII’. More poignantly perhaps, and hinting at student appreciation of his wider contribution, the same article declared that ‘Ronan has sacrificed his time, effort and mental health to help make the department the success it is’ (Drumlin, Citation2002, p. 11). As a general remark, Ronan was consistently depicted in Drumlin by the students in an appreciative and even affectionate manner, there indeed being this sense that students recognized both the efforts made by him on their behalf and the tenor of his wider intellectual contributions.

Glimpsing Ronan as radical geographer

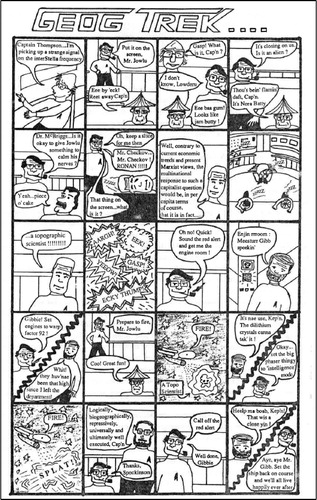

Student responses to staff teaching occasionally appeared in Drumlin, a notable example being a piece from 1989 based on a detailed student-led survey of the Honours cohorts. By this time Ronan was teaching two Honours options, ‘Political Geography’ and ‘Urban Geography’, and what are probably verbatim – and disarmingly honest – student comments on these options included such gems as: ‘The lectures were either really, really good or totally boring’; ‘Introduction and concluding lectures seemed out of place’; and ‘Dr. Paddison is quite difficult to take notes from’ (Lee, Citation1989, n.p.). Intriguingly, with reference to the ‘Political’ option and offering a clue as to the perspective that Ronan took here, one that could be cast as cleaving to what became known as a radical geography line, one remark stated ‘The class is full of restless capitalist haters – be prepared to be intimidated’ (Lee, Citation1989, n.p.). Elsewhere, in a cleverly conceived cartoon satire on the then popular TV series Star Trek, reworked here as ‘Geog Trek’, Ronan was rendered as ‘Mr Chechov’, the Russian ‘helmsman’ of the original, and given the lines ‘Well, contrary to current economic trends and present Marxist views, the multinational response to such a capitalist question would be … ’ (Moyes, Citation1991, n.p.: see ). The triple aligning of Ronan with Mr Chechov, Russia and Marxist views is intriguing, admittedly with an element of national stereotyping on show,Footnote7 but for present purposes what matters is the further indication that Ronan was bringing radical, even Marxist, theoretical insights into the classroom. The fact that Ronan’s Marxist disquisition then sent everyone else on the ‘bridge’ of the Starship Enterprise to sleep should, I feel, only be taken as the most gentle of jokes.

Figure 2. ‘Geog Trek’, with Ronan as Mr. Checkov and other staff members as other classic Star Trek characters (Source: Moyes, Citation1991).

A more direct signal of Ronan’s interest in radical or Marxist geography appeared as early as 1979 in a superficially quite playful piece where he offered ‘Thoughts from the front of the bus’ (Paddison, Citation1979) about what it meant to be a staff member leading student field trips (or field classes, as we now call them). Concluding that they allowed him the luxury of ‘brushing up on my knowledge of the regional geography of beer’ (Paddison, Citation1979, p. 12), he also ruminated on how the post-War tendency towards increasing specialization – with geographers now ceasing to be generalists and more likely becoming specialists in particular subdisciplinary fields – militated against staff members who could easily provide field teaching on all aspects of a landscape before them. Yet, he was reluctant to give up on field teaching – and see also some contributions below (Briggs, Citation2020) – and one reason for not do doing, he claimed, lay with a reinvention of field-based encounters by radical or Marxist geographers:

Interestingly enough, the reaction to the quantification, etc., of the 1960s was crusaded by the ‘new revolutionaries’, radicals and Marxist geographers, establishing field outposts of academia in downtown Detroit or Toronto. (Paddison, Citation1979, p. 12)

The allusion here was to William Bunge’s experiment circa 1968–1971 (Bunge, Citation1971) with creating a ‘geographical expedition’ to the black inner-city of Detroit, a move loosely replicated in Toronto circa 1972-1975, a now iconic – if, in retrospect, far from unproblematic – episode in the gestation of a radical, sometimes Marxist, geography (e.g. Peake, Citation2019; Warren et al., Citation2019).Footnote8

Ronan was cautiously inspired by this experiment and its offshoots, and I think it possible to read quite a lot into how he smuggled Bunge's example into an ostensibly light musing on the relatively mundane task of field-teaching. In fact, writing three decades later in the ‘Glasgow Geography Centenary’ SI of the Scottish Geographical Journal, Ronan explicitly returned to the same muse when pondering how, in theory, it might have been possible in the early-1980sFootnote9 to conduct field-teaching in Glasgow itself:

Ideally, a course should have been structured along similar lines to the Geographical Expedition set up as part of the student curriculum in North American cities and pioneered in Detroit. The predicament of Glasgow in the early-1980s – essentially problems of poverty and of inadequate housing that peaked in inner-city areas of the East End such as Bridgeton and Dalmarnock, but that were beginning to emerge in the then relatively recent peripheral estates of the city – matched the conditions documented in Bill Bunge’s influential study of the predominantly black inner-city neighbourhood of Fitzgerald in Detroit. (Bunge, Citation1971; Paddison, Citation2009, p. 341)

Ronan then explained why differences between the educational structures of degree programmes in Britain and the USA would have prohibited such a course in Glasgow, before describing his alternative teaching practice of ‘urban walks’ through which students could encounter the ‘micro-spaces’ of ‘the other Glasgow’ (notably the informal street-trading district known as Paddy’s MarketFootnote10).

Tellingly, Ronan wanted students – who, in the early-1980s, ‘continued to be drawn principally from the city region’ (Paddison, Citation2009, p. 340), but very rarely from the city’s ‘dangerous places’ (after Campbell, Citation1993) – to gain some acquaintance with the city beyond its more polite facades. He wanted them to be aware of the city’s ‘uneven development’ as an outcome of capitalist urban dynamics and the grubby politics of power: ‘in a city such as Glasgow there is an onus on the academic urban political geographer to raise a critical awareness of the conflicts surrounding urban change that become played out in its different quarters’ (Paddison, Citation2009, p. 340).Footnote11 As the testimonies appearing later in this SI demonstrate, moreover, Ronan created a safe but adventurous ‘space’ in which students, ones perhaps already possessed of a dimly formulated political sensibility critical of inequality and injustice, were able to ‘recognize’ themselves as aspiring radical geographers. Ronan’s own readiness to learn from Glasgow, a deindustrializing city striated by huge wealth disparities as a crucible for thinking through the pitted urban politics of inequality and injustice, clearly also permeated this enabling ‘space’ for student learning and study. As such, Ronan, his students and the city of Glasgow could be a footnote to the remarkable retelling of radical geography’s ‘spatial histories’ found in the recent volume edited by Barnes and Sheppard (Citation2019a), even a minor variant on the ‘truth spot’ comprised by David Harvey, his co-workers and the city of Baltimore (Sheppard & Barnes, Citation2019a).

The Peet-Paddison exchange

Ronan generously contributed his own writings to Drumlin, adding to the journal’s pages what the 1998 review nicely referenced as his ‘sensible article[s]’ (Drumlin, Citation1998, p. 26 & 27). Five such relatively weighty pieces are worth mention, four of which had substantive foci: one in 1986 about the passing of the Greater London Council (GLC) (Paddison, Citation1986); one in 1988 about the UK Poll Tax (Paddison, Citation1988); one in 1990 about the political-geographical restructuring of Eastern Europe with the Fall of the Berlin Wall (Paddison, Citation1990); and one in 2002 about the position of universities in what he termed here ‘the global-local nexus’ (Paddison, Citation2002). The latter piece appeared alongside the aforementioned ‘A tribute’ when Ronan demitted the Headship, and my suspicion is that the student editors that year would have asked him to pen some reflections on his time as Head, but that instead – typically shunning any centralizing of himself – he elected to offer broader reflections on the current university sector (but still, notably, with a political-geographical alertness to the interplay of global forces and local attachments in the restructuring of that sector). I can detect a similar move elsewhere in Ronan’s oeuvre, as I will revisit when concluding.

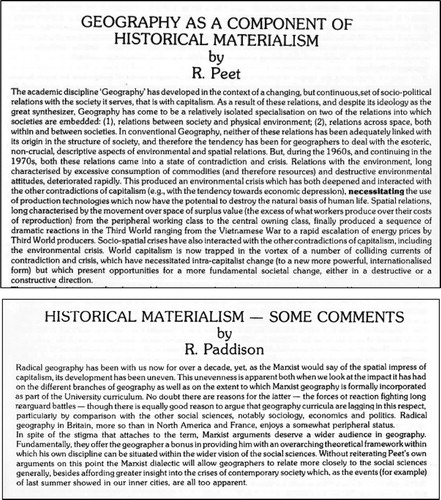

It is a fifth piece on which I wish to dwell in closing this section on Ronan in Drumlin. In 1982, the student editors contacted Richard Peet, one of the founders and doyens of radical geography, based at Clark University in the USA, to see if he might write something for the journal.Footnote12 Surprisingly perhaps, at least from the vantage-point of 2020, Peet agreed and offered a short paper entitled ‘Geography as a component of historical materialism’ (Peet, Citation1982) which forwarded a characteristically trenchant, red-in-tooth-and-claw Marxist-dialectical account of a discipline, academic geography, that needed to stop ‘serving’ the relations of capitalist society. Ronan then offered a short response, ‘Historical materialism – some comments’ (Paddison, Citation1982), that revealed the depth, and indeed sophistication, of his own engagement with Marxist-radical geography and its possible theoretical underpinnings (see ). His opening gambit here was crucial: ‘Radical geography has been with us now for over a decade, yet, as the Marxist would say of the spatial impress of capitalism, its development has been uneven’ (Paddison, Citation1982, p. 14).Footnote13 Immediately, therefore, he showed an alertness to difference, to variability in what Marxism entails for geographers and how it has been developed across the discipline, an alertness to which I will return shortly. I want to pull out five statements from Ronan’s response, briefly elaborating on why each of them discloses something significant. I would like to keep in mind the fact that these words were drafted in 1982, still very much in the early days of incarnating something called Marxist geography and before sophisticated treatments of its potentials and limits had become at all common in the organs of the discipline. The first statement ran as follows:

This is not the place to argue the merits or otherwise of Marxist forms of analysis – and to complicate matters for the student there are a sizeable and growing number of these – though it would be amiss to point out that Peet, in striving to write an assimilable account, tends to oversimplify the issues at stake. (Paddison, Citation1982, p. 15)

Figure 3. Collage of first pages of Drumlin papers by R. Peet and R. Paddison (Source: Paddison, Citation1982; Peet, Citation1982).

Echoing his open gambit, here Ronan emphasized the existence of many Marxisms, and by implication many possible renderings of Marxist geography, and made plain his sense that Peet’s version of Marxist (or historical-geographical) geography was indeed ‘over-simplifying’ issues. To an extent Ronan excused Peet on the grounds of the latter striving to give an account ‘assimilable’ by students, but Ronan’s objections ran deeper than merely matters of presentation:

… [Peet’s] argument that the capitalist mode of production necessitates a powerful state which will assure the maintenance of the system, particularly through accumulation and reproduction, skates over the arguments of Poulantzas, Milliband and others that the state in capitalist societies acts in a ‘relatively autonomous’ fashion. That is, the state is not exclusively the guardian of capitalist interests – though over the longer term it acts to maintain the status quo. (Paddison, Citation1982, p. 15)

Lightly acknowledging the depth of his own reading, notably of French urbanists in the Marxist tradition or of ‘Anglo’ political scientists reworking Marxist influences, this passage saw Ronan stressing the complexity of the state under capitalism. No essentialist picturing of the state as the ‘executive’ of the ruling class, nor even of capturing it through more nuanced capital-logic theorizing, Ronan signalled his own thinking-in-process about the state as ‘relatively autonomous’, not always in hock with capitalist interests, even if still tending ‘to ensure the overall cohesiveness of the social formation, providing a stable framework within which capitalism will be fostered’ (Paddison, Citation1983, p. 7). Not elaborated here, although perhaps implied by his wish to retain something of academic geography’s older regional focus, is how much Ronan’s interest in the ‘local state’ – and the different ‘levels’ of the state below its national presence – served further to complicate and enhance his own theorizing of the differentiated agencies, apparatuses, practices and spatialities of ‘the’ state.Footnote14 Such was arguably the key message to fall from The Fragmented State (MacLeod, Citation2020; Paddison, Citation1983), appearing a year after his Drumlin reply to Peet.

More specifically with reference to what Peet said about needing completely to transform the discipline, Ronan reflected:

A radical approach … is highly critical of the traditions of geography – regional descriptions, the over-emphasis on the geometry of spatial relations, positivism and so on – and no doubt many geographers would find it difficult to stomach that [quoting from Peet’s paper] ‘it is little use continuing with, or merely modifying conventional Geography, arming it with additional mathematical or behavioural tools, or linking Geographers with a vague moral humanism, or losing oneself in the intricacies of human experience’. These debates are well-known and Marxists in geography have been accused of a certain intellectual blindness or possibly arrogance. (Paddison, Citation1982, p. 15)

A host of theoretical-historiographic considerations permeate this passage, demonstrating Ronan’s familiarity with older disciplinary approaches: regional description, locational analysis (identified here, with great acuity, as ‘the geometry of social relations’) and engaging Peet’s own rejection of quantitative geography, behavioural geography, humanistic geography (enmired in ‘the intricacies of human experience’) and also the ‘liberal’ or ‘welfare geography’ tradition closely associated in the UK with David M. Smith (the target, I suggest, when Peet was attacking ‘vague moral humanism’: see Smith, Citation1977, Citation1979). Ronan’s reflection has a tone that suggested his distaste for such crude dismissals of other, non-Marxist endeavours, past and present, and – as in the quote below – he confessed his own training in behaviouralism (and note the behavioural bent to a political geography textbook that Ronan co-authored: Muir & Paddison, Citation1981) as well as quantification (see also Pattie, Citation2020). He noted how Marxist geography set up camp in opposition to behaviouralism – ‘one of the bète-noirs of the radical’ (Paddison, Citation1982, p. 15) – and also to humanistic geography, yet Ronan supposed that these more human-facing positions should still be valued for ‘the understanding they give of man [humanity] in space’ (Paddison, Citation1982, p. 15). In sum, he left his audience in little doubt that he wished to retain conceptual and methodological eclecticism, arguably in line with the eclectic origins of radical geography, as in the early issues of Antipode, prior to it becoming more narrowly closed around a Marxist analytics in ‘classical’ or structural guises (Barnes & Sheppard, Citation2019b, p. 22; Huber et al., Citation2019, esp.96; Philo, Citation1998b; Sheppard & Barnes, Citation2019b, p. 372).

That said, Ronan was far from being a Marxist refusenik:

Geographers, however, are not (nor should they be) recluses. Marxist forms of analyses – as the work of the French urban school admirably shows – offer the geographer a theoretical framework with which to grapple with the crises and contradictions of contemporary capitalist societies. (Paddison, Citation1982, p. 15)

Marxism had undoubtedly become a central departure-point for Ronan, precisely of course why he was able to craft a reply to Peet, and he praised Marxism for its offering of a ‘theoretical framework’ while accenting his borrowing from ‘the French urban school’ in this connection. Finally, though, he admitted the challenge posed for the likes of himself, trained in older and other species of the geographical project:

Intellectually, the radical road is not an easy one for the geographer. For one thing, many of us have been trained in the positivist/behaviouralist mould in which space is basically seen as a regulator or conditioner of action. Marxists argue very differently – space is a record of social relations. (Paddison, Citation1982, p. 15)

In barely a handful of words here, Ronan alluded to a vast expanse of high-level debate – much of it yet to happen – about the many, often fractious ways in which socio-spatial relations might be conceptualized. Obviously detecting fault in previous disciplinary conceptions wherein space acquired a far too simplistic, deterministic role, he turned instead to a Marxist vision of ‘space [as] a record of social relations’, itself arguably leaning too far in the other direction wherein space becomes a passive realm merely awaiting social inscription (c.f. Gregory & Urry, Citation1985; Soja, Citation2000). Thus, while this particular formulation might be contested – and indeed it sits ill with the semi-autonomy that Ronan consistently lent to the local state, ‘banal spaces’ in the city (Paddison & Sharp, Citation2007), civic spaces and public artworks, and so on – the key take-home is that Ronan was well-aware of both the need for careful theoretical (and political) work to be conducted around the problematic of ‘society and space’ and for Marxism to be pivotal to such work.

I am not about to suggest that these five statements encapsulate all the richness of Ronan’s academic thought, but I would argue that the sensibility on display – a scholarly and worldly attuning to difference, multiplicity, alternatives, even eclecticism – characterizes not only Ronan’s words here, in this riposte to Peet, but also all his contributions to the academy and its applications. The contributions throughout this SI, but particularly those scissoring into Ronan’s theorizing and publications, amply evidence such a claim, to which I might append the further proposal that Ronan was really a poststructuralist avant la lettre: a poststructural political and urban geographer before the term had properly been coined and circulated in the discipline. Always hesitant before any forms of reductionist or foundationalist thinking; always alive to the limitations of ‘big’ structuralist analysis for which the complications of detail, context, time and space are anathema; always plotting paths away from the paralysis of despairing structural critique to the energies of resistant local (urban-political) power;Footnote15 always open to and generous about methodological plurality; always (com)passionate about what might be found around the corner intellectually, politically and ethically; but never for a moment abandoning the radical or critical impulse in his inquiries, his teaching or his community practice: for me, these are the critical hallmarks of what we have named, for the purposes of this SI, ‘Paddison geographies’.Footnote16

Final thoughts

I have sought in this paper to introduce this academic commemoration of Ronan Paddison (1945–2019: see ), partly by describing what follows in this SI, but chiefly by offering some views of Ronan as an academic from the somewhat oblique vantage-point of a student-led geographical journal, Drumlin. Such views start to open up, however incompletely, aspects of: Ronan as a leading scholar, a thinker well-versed in radical theory and seeped in the history, traditions, theories and methods of academic geography; Ronan as an educator, an inspirer, a quiet but effective practitioner of critical pedagogy; Ronan as a placed but global ‘urban political geographer’, researching, learning from and bringing learning to his beloved (but oft-critiqued) Glasgow; and Ronan as a humorous, respected and indeed warmly-regarded member and sometime leader of the Glasgow Geography community. Other contributions to this SI will of course elaborate on different of these aspects.

Figure 4. Ronan Paddison, June 2017, when he was on a visiting position at the University of Trento, Italy (Source: courtesy of Lesley Paddison).

It might finally be noted that Ronan was rarely one to centralize himself, to ‘big himself up’, to display those worst traits of some academics for whom self comes before world. For Ronan, it was always the reverse. Hence, as mentioned, when invited by the editors of Drumlin to reflect upon his Headship of the department at Glasgow, he chose instead to discuss the global-local geographies of the university sector. Similarly, when invited to contribute to a series of ‘Recollections and reflections’ for that 2009 ‘Glasgow Geography Centenary’ SI also referenced earlier, he said very little specifically about himself but rather used the opportunity for a broader disquisition about what is entailed in ‘teaching a city’ (Paddison, Citation2009). It hence occurs to me that, as Editor-in-Chief of Space and Polity, he would probably have turned down any proposal to devote an entire SI to assessing his own academic contributions and legacies. On this occasion, however, there are abundant reasons, copiously exampled throughout what follows, for reaching a different decision.

Acknowledgements

Huge thanks to all who contributed to the 2019 Commemoration event mentioned in the text, and for the generous responses to my own presentation delivered then and now reworked here. Specific thanks to Mark Boyle for his input, two referees for their useful advice, and Trevor Barnes for his gracious remarks on a draft of the present piece. Further thanks to Lesley Paddison for her assistance with preparing the timeline in and for providing two of the photographs included here, and to Stephen Crone for by far the lion’s share of work on the publications list in Appendix 2. Final thanks of course to Ronan himself, the inspiration and prompt for everything contained herein.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes on contributor

Chris Philo has been a Professor of Geography at the University of Glasgow since 1995, following a Lectureship at the University of Wales, Lampeter, 1989–1995, and undergraduate/postgraduate/postdoctoral studies at the University of Cambridge, 1980–1988. He has engaged with many different aspects of academic Geography, specifically the historical geographies of ‘madness’ and ‘asylums’, and has long been interested in how we capture the history of human geography. One dimension of that task is taking seriously the contributions of individual geographers, both through their active research (projects and publications) and their wider, sometimes more invisible, contributions with respect to nurturing their ‘disciplines’ (through the likes of editorial work, mentoring, supervising and teaching). That task becomes more urgent for I in relation to this specific special issue of Space and Polity, addressing the many contributions made by his much-valued one-time Glasgow colleague, Ronan Paddison.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Notes

1 Throughout I will say ‘Ronan’ rather than ‘Paddison’, although I do want this paper to be read – even given the unusual vehicle for crafting its argument, a student-led geographical journal called Drumlin – as a serious engagement with Paddison the scholar.

2 This one-day event was convened by Chris Philo with assistance from Mark Boyle. It was partially sponsored by Space and Polity (or, rather, by the publishers of this journal, Taylor & Francis), with the remainder of the costs being met by the Human Geography Research Group of the School of Geographical and Earth Sciences (GES). Thanks are due to Sarah Bird (Editorial Assistant for Space and Polity) and, from GES, Dawn Bradshaw, Yvonne Finlayson, Leenah Khan and Jean McPartland, for their various roles in ensuring the smooth running of the event. The event was attended by over 40 people who had been colleagues, collaborators, doctoral (and in many cases also undergraduate) students or simply scholars who had made use of Ronan’s published work in their own endeavours. It was also attended by Lesley Paddison, Ronan’s wife, and their three sons, Alastair, Andrew and Angus.

3 All contributions to the SI have been subject to review: the longer pieces to the usual procedures of academic peer review, but the shorter pieces to a more light-touch editorial review. The overall SI has been edited by Mark Boyle with assistance from Chris Philo, and with additional external oversight of the whole ‘package’ offered by Eugene McCann (Simon Fraser University, Vancouver) and Lorna Philip (University of Aberdeen).

4 For many years it was the Department of Geography and Topographic Science, before becoming the Department of Geography and Geomatics, and then, more recently, the School of Geographical and Earth Sciences. For more on the history of Geography as researched and taught at the University of Glasgow, see the 2009 SI of the Scottish Geographical Journal celebrating the Centenary of the first formal establishment of a ‘Lecturer in Geography’ at Glasgow (esp. Philo et al., Citation2009; Lorimer & Philo, Citation2009).

5 The humour of such contributions changed considerably across the period, from very respectful and coded in the 1950s-1970s to being quite brazen, even verging on crude and insulting at times, in the 1980s–1990s, to being really quite subtle and clever in the 2000s. Suffice to say that Drumlin opens a window on past ‘departmental cultures’ that now, in a time of great anxiety about where properly to draw the lines of engagement and propriety between staff and students, seem almost unimaginable in their easy familiarity and general subversiveness.

6 ‘Dr Briggs’ was a reference to John Briggs, another very long-serving and very well-liked academic in Geography at the University of Glasgow. Appropriately, Briggs (Citation2020) provides one of the contributions to this SI, foregrounding Ronan as educator and ‘institutional’ leader.

7 There are other stereotypes coded into this cartoon, of course, some with ‘national’ elements that might now be thought problematic, notably Mr Chechov’s fellow ‘helmsman’, Mr Sulu, of Chinese origins, being portrayed as ‘Mr Jowlu’, a skit on John Jowatt, a Scottish staff member with Chinese research interests (Mr Jowlu is given a ‘Chinese’ hat and a Scottish accent). I will leave others to guess at other staff members depicted here, and the various cross-references in play, but I should note that the alien ‘enemy’, a ‘topographic scientist’, references the fact that for many years the Glasgow department supported two undergraduate degrees, Geography and Topographic Science (now what is widely known as Geomatics), between the students of which there was considerable (if mostly benign) ‘sibling’ rivalry.

8 Ronan clearly knew a lot about the Detroit Expedition: he passed on to me a number of obscure typescript ‘Field Notes’ and related documents from the Expedition. I also noticed the other day that several very early copies of Antipodes on my shelves have written on the cover ‘Return to Ronan Paddison’. Whoops, sorry Ronan. Intriguingly, in at least one issue of Antipode from the late-1970s notice is given of a forthcoming special issue on ‘Urban Political Geography' to be edited by Ronan Paddison (Antipode, Citation1979a, inside front cover), further evidencing Ronan’s early engagement with radical geography. The explicit conjoining of ‘urban' and ‘political’ is also salient for claims made in my main text (see also my Note 11 and MacLeod, Citation2020). It is unclear that such a special issue ever appeared, certainly not as planned, although mention is made by Peet (Citation1985, p.2) to a special issue of Antipode on ‘The urban problematic', edited by ‘Joe Doherty, R. Paddison and N. Smith’, contributions to which - alongside those to three other special issues from the late-1970s - he suggests “were last bursts of colour in the fall of our 1960s style radicalism”. The issue in question (Antipiode, Citation1979b) is cited in Peet's references as Vol.11, No.3, 1979. That issue does contain papers by both Doherty and Smith, but not one from Ronan, and there is no editorial indicating that it is indeed a special issue (even if several papers could readily be badged as urban-political).

9 In his 2009 piece Ronan actually took the Peet (Citation1982) Drumlin paper (discussed later in my paper) as a prompt to think about Glasgow in the early-1980s, and then to ask how Glasgow geographers at that time might have heightened student awareness of a city increasingly scarred by the ‘uneven development’ about which Peet had written: see Paddison (Citation2009, p. 340). Typically, he never mentioned his own response to Peet’s paper.

10 Contrary to some student misconceptions, Paddy’s Market was not in any way ‘owned’ by Ronan Paddison.

11 It is instructive that in this quote Ronan spoke of ‘the urban political geographer’, emphasising precisely that conjunction – of the political and the urban, of political geography and urban geography – that arguably reveals so much about the distinctiveness of his overall academic contribution.

12 ‘The editor that year wrote to [Peet], no previous contact, no ‘Dr X said’ – a purely speculative letter’ (Charles Pattie, personal communication, 22/10/2019 [Pattie was on the Drumlin Committee for this issue]). As well as Ronan’s response to Peet (discussed presently), a piece appeared in the same issue from Briggs that, when considering what Marxist perspectives might bring to studies of ‘underdevelopment’, hinted at a wider terrain of debate – engaging with the Marxist geography challenge – then exciting a few Glasgow staff members (Briggs, Citation1982).

13 A claim that could have featured at the outset of Barnes and Sheppard (Citation2019a).

14 ‘Marxist accounts of the state have tended to treat it as an undifferentiated whole, that is, they have not recognised any separate existence for local government. Also, where Marxist accounts have recognised different levels of government … , there is a tendency to see the local jurisdiction merely as an agent of central government’ (Paddison, Citation1983, p. 8).

15 Ronan once told me that his big scholarly ambition was eventually to write a book on local power. In The Fragmented State, attention is paid to ‘the competition for local power’ (Paddison, Citation1983, p. 12 [a section heading]), and my contention would be that Ronan often took heart from the extent to which this competition was not always ‘won’ by the state (local, regional or national) or, better, was not always ‘won’ by socially regressive forces (which on occasion might actually be held in check by the [local] state). The often seemingly banal battles of local urban politics were hence, for him, always key sites in which local power could be rendered ‘dominant’ or ‘resistant’ (to couple with terms/concepts from Sharp et al., Citation2000a).

16 For me, these were also the key principles and sensibilities that Ronan brought to the (poststructuralist-inflected) Entanglements of Power book co-edited by Jo Sharp, Paul Routledge, myself and Ronan (Sharp et al., Citation2000a), and more particularly to a section in our lengthy opening chapter entitled ‘Orthodox accounts I: power equals domination’. Thanks to Ronan, and notwithstanding the section title, the text here offered a remarkably sinuous interfacing of Marx, Foucault, ideas from political science (about decision-making and game theory) and concerns for differentiated state apparatuses, agencies, practices, levels and spatialities. It concluded as follows, a ringing Paddisonian vision: ‘Writers increasingly recognise the different forms of power exercised by the state, as well as the different interests that might work through these varied forms, and such difference, together with the spatial complexities of territoriality, insert new threads into thinking about the entangled geography of state power’ (Sharp et al., Citation2000b, p. 8).

References

- Antipode. (1970). Call for papers: Alternative proceedings, 1971: Studies in survival and radical geography. Antipode: A Radical Journal of Geography, 2(1), 3. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.147678330.1970.th00468x

- Antipode (1979a). Inside Front Cover material. Antipode: A Radical Journal of Geography, 11(2).

- Antipode (1979b). Special issue on ‘The urban problematic’ [?]. Antipode: A Radical Journal of Geography, 11(3).

- Barnes, T. J., & Sheppard, E. (Eds.). (2019a). Spatial histories of radical geography: North America and beyond. John Wiley.

- Barnes, T. J., & Sheppard, E. (2019b). Introduction. In T. J. Barnes & E. Sheppard (Eds.), Spatial histories of radical geography: North America and beyond (pp. 1–36). John Wiley.

- Beel, D., Crotty, J., Doherty, I., McCormick, J., & Stewart, D. (2020).

- Bloomsbury Collections. (Various years). Geographers: Biobliographical studies. https://www.bloomsburycollections.com/search?newSearch&browse&product=geographersBiobibliographicalStudies)

- Boyle, M. (2020). States of Power: Ronan Paddison, Space and Polity. Space and Polity, 24(2), doi: 10.1080/13562576.2020.1793616

- Briggs, J. A. (2020). Ronan as educator: teacher and academic leader. Space and Polity, 24(2), doi: 10.1080/13562576.2020.1788931

- Briggs, J. (1982). Geography and underdevelopment in Africa. Drumlin, Issue 27, 4–6.

- Bruinsma, M. (2020). The geographers in the cupboard: Narrating the history of geography using undergraduate dissertations. Area. forthcoming.

- Bunge, W. (1971). Fitzgerald: Geography of a revolution. Shenkman.

- Campbell, B. (1993). Goliath: Britain’s dangerous places. Methuen.

- Cumbers, A., & Philo, C. (2019). Ronan Paddison (1945–2019): An appreciation of an academic life. Urban Studies, 56(13), 2011–2015. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098019874587

- Drumlin. (1973). Departmental news. Drumlin, Issue 1972–1973 (p. 72).

- Drumlin. (1975). Departmental news. Drumlin, Issue 1974–1975.

- Drumlin. (1976a). Departmental news. Drumlin, Issue 1976–1977.

- Drumlin. (1976b). Jogsok Top Ten. Drumlin, Issue 1976–1977.

- Drumlin. (1983). Focus on Ronan Paddison. Drumlin, Issue 1982–1983.

- Drumlin. (1986). The epic adventures of Ronan the Barbarian. Drumlin, Issue 1985–1986 (pp. 27 & 30).

- Drumlin. (1990). Quotes from Geog-Thought. Drumlin, Issue 1989–1990.

- Drumlin. (1998). Paddison thru’ the pages. Drumlin, Issue 1997–1998 (pp. 26–27).

- Drumlin. (2002). A tribute to Ronan. Drumlin, Issue 2001–2002 (p. 11).

- Gregory, D., & Urry, J. (Eds.). (1985). Social relations and spatial structures. Macmillan.

- Huber, M. T., Knudson, C., & Tapp, R. (2019). The making of Antipode at Clark University. In T. J. Barnes & E. Sheppard (Eds.), Spatial histories of radical geography: North America and beyond (pp. 87–116). John Wiley.

- Ianos, I. (2019). A life for science: Ronan Paddison (1945–2019). Journal of Urban and Regional Analysis, XI, 109–111. http://www.jurareview.ro/resources/pdf/volume_11_issue_2_2019_file_pdf

- Kallio, K. (2020). Lessons in the art of scientific editing, Space and Polity, 24(2), DOI:10.1080/13562576.2020.1787134

- Karaliotas, L. (2020). Ronan Paddison on public space and the post-political, Space and Polity, 24(2), DOI:10.1080/13562576.2020.1787136

- Laurie, E., & Philo, C. (2020). The Post(-)colonial Arab City, Space and Polity, 24(2), DOI:10.1080/13562576.2020.1787135

- Lee, K. (1989). Which option should I choose? Drumlin, Issue 1988–1989.

- Livingstone, D. N. (2003). Putting science in its place: Geographies of scientific knowledge. Chicago University Press.

- Lorimer, H., & Philo, C. (2009). Disorderly archives and orderly accounts: Reflections on the occasion of Glasgow’s geographical century. Scottish Geographical Journal, 125(3–4), 227–255. https://doi.org/10.1080/14702540903364278

- MacLeod, G. (2020). Intensifying fragmentation? states, places, and dissonant struggles over the political geographies of power, Space and Polity, 24(2), DOI:10.1080/13562576.2020.1775574

- McKendrick, J. (2020). Of a time and place: Glasgow and its quality of life geographies, Space and Polity, 24(2), DOI:10.1080/13562576.2020.1790351

- Miles, S. (2020). Consuming culture-led regeneration: the rise and fall of the democratic urban experience, Space and Polity, DOI:10.1080/13562576.2020.1775573

- Moyes, G. (1991). Geog Trek [cartoon]. Drumlin, Issue 1990–1991.

- Muir, R. E., & Paddison, R. (1981). Politics, geography and behaviour. Methuen.

- Naylor, S. (2005a). Introduction: Historical geographies of science – Places, contexts, cartographies. British Journal for the History of Science, 30(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007087404006430

- Naylor, S. (2005b). Historical geography: Knowledge in place and on the move. Progress in Human Geography, 29(5), 626–634. https://doi.org/10.1191/0309132505ph573pr

- Paddison, R. (1979). Thoughts from the front of the bus. Drumlin, Issue 1978–1979 (pp. 10–12).

- Paddison, R. (1982). Historical materialism – Some comments. Drumlin, Issue 1981–1982 (pp. 14–15).

- Paddison, R. (1983). The fragmented state: The political geography of power. Basil Blackwell.

- Paddison, R. (1986). Some thoughts on the passing of the GLC. Drumlin, Issue 1985–1986 (pp. 28–29).

- Paddison, R. (1988). The Poll Tax: How different is Britain? Drumlin, Issue 1987–1988 (pp. 48–52).

- Paddison, R. (1990). What is happening in Eastern Europe? The uncollected thoughts of a political geographer. Drumlin, Issue 1989–1990.

- Paddison, R. (2001). Retiral of Alastair Morrison – An appreciation. Drumlin, Issue 2000–2001 (pp. 20–21).

- Paddison, R. (2002). Thoughts on universities in the global-local nexus. Drumlin, Issue 2001–2002 (pp. 8–9).

- Paddison, R. (2009). The other Glasgow: Reflections on teaching a city. Scottish Geographical Journal, 125, 339–343. http://doi.org/10.1080/14702540503364351

- Paddison, R., & Sharp, J. (2007). Questioning the end of public space: Reclaiming the use of local banal space. Scottish Geographical Journal, 123(2), 87–106. https://doi.org/10.1080/14702540701615236

- Pattie, C. (2020). Paddison Electoral and Fiscal Geographies, Space and Polity, 24(2); DOI:10.1080/13562576.2020.1773779

- Peake, L. (2019). The life and times of the union of socialist geographers. In T. J. Barnes & E. Sheppard (Eds.), Spatial histories of radical geography: North America and beyond (pp. 149–182). John Wiley.

- Peet, R. (1982). Geography as a component of historical materialism. Drumlin, Issue 1981–1982 (pp. 11–14).

- Peet, R. (1985). Radical geography in the United States: a personal history. Antipode 17, 1–7.

- Philo, C. (1998a). Eclectic original geographies: Revisiting the early Antipodes. Unpublished typescript. [email protected]/116527/

- Philo, C. (1998b). Reading Drumlin: Academic geography and a student geographical magazine. Progress in Human Geography, 22(3), 344–367. https://doi.org/10.1191/030913298666735462

- Philo, C., Lorimer, H., & Hoey, T. (2009). Guest editorial. Scottish Geographical Journal, 125(3-4), 221–226. https://doi.org/10.1080/14702540903364260

- Pollock, V. (2020). Exploring Ronan's conceptual, methodological and substantive innovations. Ronan on Public Art, Space and Polity, 24(2), DOI:10.1080/13562576.2020.1766354

- Sharp, J. P., Routledge, R., Philo, C., & Paddison, R. (2000a). Entanglements of power: Geographies of domination/resistance. Routledge.

- Sharp, J. P., Routledge, R., Philo, C., & Paddison, R. (2000b). ‘Entanglements of power: Geographies of domination/resistance. In J. P. Sharp, R. Routledge, C. Philo, & R. Paddison (Eds.), Entanglements of power: Geographies of domination/resistance (pp. 1–42). Routledge.

- Sheppard, E., & Barnes, T. J. (2019a). Baltimore as truth spot: David Harvey, Johns Hopkins and urban activism. In T. J. Barnes & E. Sheppard (Eds.), Spatial histories of radical geography: North America and beyond (pp. 183–210). John Wiley.

- Sheppard, E., & Barnes, T. J. (2019b). Conclusion. In T. J. Barnes & E. Sheppard (Eds.), Spatial histories of radical geography: North America and beyond (pp. 371–387). John Wiley.

- Smith, D. M. (1977). Human geography: A welfare approach. Edward Arnold.

- Smith, D. M. (1979). Where the grass is greener: Living in an unequal world. Penguin Books.

- Soja, E. W. (2000). The socio-spatial dialectic. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 70(2), 207–225. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8306.1980.tb01308.x

- Warren, G. C., Katz, C., & Heynen, N. (2019). Myths, cults, memories and revisions in radical geographic history: Revisiting the Detroit geographical expedition and institute. In T. J. Barnes & E. Sheppard (Eds.), Spatial histories of radical geography: North America and beyond (pp. 59–86). John Wiley.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Timeline of Ronan Paddison’s life and academic career

(Prepared by Chris Philo with substantial input from Lesley Paddison.)

Appendix 2. Academic publications by Ronan Paddison

(Prepared by Stephen Crone and lightly edited by Chris Philo. Publications are listed in chronological (not alphabetical) order, organized into different types of publications. We have not included book reviews, short journal editorials, other academic ephemera, contributions to popular media or pieces in Drumlin (for the latter, see References above). It is hoped that this publications list contains the vast majority of Ronan Paddison’s published academic works, with correct bibliographic details, but inevitably there may be some omissions and errors. We acknowledge some missing page numbers for book chapters.)

Thesis

Paddison, R. (1969). The evolution and present structure of central-places in North-East Scotland (Unpublished PhD thesis, University of Aberdeen).

Books (authored and edited, including ‘reports’)

Paddison, R. (1978). The political geography of regionalism: The processes of regional definition and regional identity. Armidale: University of New England.

Muir, R. and Paddison, R. (1981). Politics, geography and behaviour. London: Methuen.

Paddison, R. (1983). The fragmented state: The political geography of power. Oxford: Blackwell.

Bailey, S. J. and Paddison, R. (Eds.). (1988a). The reform of local government ginance in Britain. London: Routledge.

Paddison, R. and Bailey, S. J. (Eds.). (1988b). Local government finance: International perspectives. London: Routledge.

Findlay, A. M., Paddison, R. and Dawson, J. A. (Eds.). (1990). Retailing environments in developing countries. London: Routledge.

Paddison, R. (Ed.). (2000). Handbook of Urban Studies. London: Sage.

Sharp, J. P., Routledge, P., Philo, C. and Paddison, R. (Eds.). (2000). Entanglements of power: Geographies of domination and resistance (pp. 1–45). London: Routledge.

Turok, I., Bailey, N., Atkinson, R., Bramley, G., Docherty, I., Gibb, K., Goodlad, R., Hastings, A., Kintrea, K., Kirk, K., Leibovitz, J., Lever, B., Morgan, J., Paddison, R. and Sterling, R. (2003). Twin track cities? Linking prosperity and cohesion in Glasgow and Edinburgh. Glasgow: University of Glasgow.

Paddison, R. and Miles, S. (Eds.). (2007). Culture-led urban regeneration. London: Routledge.

Paddison, R., Ostendorf, W. J. M., McNeill, D., Tiesdell, S. A. and Parnell, S. M. (Eds.). (2009). Urban studies – Society, volumes 1–4. London: Sage Urban Studies Library Series.

Paddison, R., Timberlake, M., Williams, C. C., Marcotuillo, P. and Haila, A. (Eds.). (2009). Urban studies – Economy, volumes 1–4. London: Sage Urban Studies Library Series.

Paddison, R. and McCann, E. (Eds.). (2014). Cities and social change: Encounters with contemporary urbanism. London: Sage.

Paddison, R. and Hunter, T. (Eds.). (2015). Cities and economic change: Restructuring and dislocation in the global metropolis. London: Sage.

Book chapters

Paddison, R. (1981). Identifying the local political community: A case study of Glasgow. In A. D. Burnett and P. J. Taylor (Eds.), Political studies from spatial perspectives: Anglo-American essays on political geography (pp. 341–355). Chichester: Wiley.

Paddison, R. (1983). Intergovernmental relationships and the territorial structure of federal states. In: N. Kliot and S. Waterman (Eds.), Pluralism and political geography: People, territory and state (pp. 245–258). London: Croom Helm.

Paddison, R. (1985). Local democracy in the city. In M. Pacione (Ed.), Progress in political geography (pp. 216–242). London: Routledge.

Boyle, M., Findlay, A. M., LeLievre, E. and Paddison, R. (1994). French investment and skill transfer in the United Kingdom. In W. T. S. Gould and A. M. Findlay (Eds.), Population migration and the changing world order (pp.47–65). Chichester: Wiley.

Paddison, R. (1997). The restructuring of local government in Scotland. In J. Bradbury and J. Mawson (Eds.), British regionalism and devolution. London: Jessica Kingsley.

Paddison, R. (1997). Political geography at the subnational scale: spatial implications of local and regional government. In R. D. Dikshit (Ed.), Developments in political geography: A century of progress. London: Sage.

Paddison, R. and Paddison, A. (1998). Consumption and retailing: Sameness and difference. In T. Unwin (Ed.). A European geography (pp.220–223). London: Addison, Wesley, Longman.

Paddison, R. (2000a). Communities in the city. In R. Paddison (Ed.), Handbook of Urban Studies. London: Sage.

Paddison, R. (2000b). Studying cities. In R. Paddison (Ed.), Handbook of Urban Studies. London: Sage.

Sharp, J. P., Routledge, P., Philo, C. and Paddison, R. (2000) Introduction: geographies of domination and resistance. In Sharp, J. P., Routledge, P., Philo, C. and Paddison, R. (Eds.) Entanglements of power: Geographies of domination and resistance (pp.1–45). London: Routledge.

Paddison, R. (2004). Redrawing local boundaries: Deriving the principles for politically just procedures. In J. Meligrana (Ed.), Redrawing local boundaries: An international study of politics, procedures, and decisions (pp.19–37). Vancouver: UBC Press.

Turok, I., Bailey, N., Atkinson, R., Bramley, G., Docherty, I., Gibb, K., Goodlad, R., Hastings, A., Kintrea, K., Kirk, K., Leibovitz, J., Lever, B., Morgan, J. and Paddison, R. (2004). Sources of city prosperity and cohesion: the case of Glasgow and Edinburgh. In M. Boddy and M. Parkinson (Eds.), City matters: Competitiveness, cohesion and urban governance (pp.13–31). Bristol: Bristol University Press.

Sharp, J., Pollock, V. and Paddison, R. (2007). Just art for a just city: public art and social inclusion in urban regeneration. In Paddison, R. and Miles, S. (Eds.), Culture-Led Urban Regeneration (pp.156–178). London: Sage.

Paddison, R. (2009). Public art and urban cultural regeneration: reaching to the local community. In M. Legner and D. Ponzini (Eds.), Cultural quarters and urban transformation: International perspectives (pp. 230–253). Klintehamn: Gotland University Press.

Paddison, R. (2012). Housing and neighbourhood quality. In S. J. Smith (Ed.), International encyclopaedia of housing and home (pp. 288–293). London: Elsevier.

Paddison, R. (2013a). Public spaces: on their production and consumption. In G. Young and D. Stevenson (Eds.), The Ashgate research companion to planning and culture (pp. 311–324). London: Routledge.

Paddison, R. (2013b) Ethnic diversity, public space and urban regeneration. In M. Leary and J. McCarthy (Eds.), The Routledge companion to urban regeneration (pp.263–272). London: Routledge.

McCann, E. and Paddison, R. (2014). Conclusion: engaging the urban world. In R. Paddison and E. McCann (Eds.), Cities and social change: Encounters with contemporary urbanism (pp. 211–225). London: Sage.

Paddison, R. (2015). Urban studies: overview. In J. D. Wright (Ed.), International encyclopaedia of the social and behavioural sciences (second ed., pp. 940–944). Oxford: Elsevier.

Paddison, R. (2016). The rise of urban governance. In O. Nel-lo and R. Mele (Eds.), Cities in the twenty-first century (pp. 263–269). Abingdon: Routledge.

Paddison, R. (2019a). Urban studies. In A. M. Orum (Ed.), The Wiley Blackwell encyclopaedia of urban and regional studies. London: Wiley.

Paddison, R. (2019b) Place marketing. In A. M. Orum (Ed.), The Wiley Blackwell encyclopaedia of urban and regional studies. London: Wiley.

Journal articles

Paddison, R. (1970). Reorganisation of hospital services in Ireland. Irish Geography, 6, 199–204.

Paddison, R. (1974). The revision of local electoral areas in the Republic of Ireland: Problems and possibilities. Irish Geography, 7, 116–120.

Paddison, R. (1976). Spatial bias and redistricting in proportional representation election systems: A case study of Republic of Ireland. Tijdschrift Voor Economische En Sociale Geografie, 67, 230–241.

Paddison, R. (1978). Restructuring the New South Wales planning system: The administrative basis for reforms and its implications. Planning and Administration, 5, 20–26.

Gibb, A. and Paddison, R. (1983). The rise and fall of burghal monopolies in Scotland: The case of the North East. Scottish Geographical Magazine, 99, 130–140.

Findlay, A., Findlay, A. M. and Paddison, R. (1984). Maintaining the status quo: An analysis of social space in post-colonial Rabat. Urban Studies, 21, 41–51.

Paddison, R., Abichou, H., Findlay, A. and Findlay, A. M. (1984). Restructuring the urban planning machine: A comparison of two North African cities. Third World Planning Review, 6, 283–299.

Paddison, R., Findlay, A. and Findlay, A. (1984) Shop windows as an indicator of retail modernity in the Third-World City: The Case of Tunis. Area, 16, 227–231.

Paddison, R. and Findlay, A. (1985). Radicals vs positivists and the diversification of paradigms in geography. Espace Geographique, 14, 6–8.

Findlay, A. M. and Paddison, R. (1986). Planning the Arab City: The cases of Tunis and Rabat. Progress in Planning, 26, 1–82. (also exists as a stand-alone monograph: Elmsford, NY: Pergamon).

Paddison, R. and Findlay, A. (1986). Some problems in planning the office economy in a Third-World City: The Example of Tunis. Geoforum, 17, 367–374.

Findlay, A., Rogerson, R., Paddison, R. and Morris, A. (1989). Whose quality of life? The Planner, 75, 21–22.

Paddison, R. (1989). Spatial effects of the Poll Tax: A preliminary analysis. Public Policy and Administration, 4, 10–21.

Rogerson, R., Findlay, A., Morris, A. and Paddison, R. (1989). Variations in quality of life in urban Britain. Cities, 6, 227–233.

Findlay, A. M., Rogerson, R. J., Garrick, L., Morris, A. S. and Paddison, R. (1990). Pulling rank, Geographical Magazine, 62, 42–44.

Paddison, R. (1990). Nationalism and regional development. Area, 22, 210–211.

Paddison, R. (1993a). City marketing, image reconstruction and urban regeneration. Urban Studies, 30, 339–349.

Paddison, R. (1993b). Scotland, the other and the British state, Political Geography, 12, 165–168.

Findlay, A., Lelièvre, E., Paddison, R. and Boyle, M. (1994). Skilled labour migration in the European context: Franco-British capital and skill transfers. Espace, Populations, Societes, 12, 85–94.

Boyle, M., Findlay, A., Lelievre, E. and Paddison, R. (1996). World Cities and the limits to global control: A case study of executive search firms in Europe's leading cities. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 20, 498–517.

Rogerson, R. J., Findlay, A. M., Paddison, R. and Morris, A. S. (1996) Class, consumption and quality of life. Progress in Planning, 45, 1–66.

Miles, S. and Paddison, R. (1998). Urban consumption: An historiographical note. Urban Studies, 35, 815–823.

Paddison, R. (1999). Children, families and learning: A new agenda for education. Scottish Geographical Journal, 115 (2), pp. 174–175.

Paddison, R. (1999). Decoding decentralisation: The marketing of urban local power. Urban Studies, 37, 107–119.

Kearns, A. and Paddison, R. (2000). New challenges for urban governance. Urban Studies, 37, 845–850.

Kumar, A. and Paddison, R. (2000) Trust and collaborative planning theory: The case of the Scottish Planning System. International Planning Studies, 5, 205–223.

Docherty, I., Goodlad, R. and Paddison, R. (2001). Civic culture, community and participation in contrasting neighbourhoods. Urban Studies, 38, 2225–2250.

Paddison, R. (2002). From unified local government to decentred local governance: The ‘institutional turn’ in Glasgow. Geojournal, 58, 11–21.

Paddison, R. (2003). Bill Lever: Some appreciative remarks. Urban Studies, 40, 663–664.

Miles, S. and Paddison, R. (2005). The rise and rise of culture-led urban regeneration. Urban Studies, 42, 883–839.

Sharp, J., Pollock, V. and Paddison, R. (2005). Just art for a just city: Public art and social inclusion in urban regeneration. Urban Studies, 42, 1001–1023.

Paddison, R. (2007) Contested space: Street trading, public space, and livelihoods in developing cities. Urban Studies, 44 (9), pp. 1857–1858.

Paddison, R. and Sharp, J. (2008). Questioning the end of public space: Reclaiming control of local banal spaces. Scottish Geographical Journal, 123, 87–106.

Paddison, R., Docherty, I. and Goodlad, R. (2008). Responsible participation and housing: Restoring democratic theory to the scene. Housing Studies, 23, 129–147.

Paddison, R. (2009a). Devolution and the rebordering of the UK State: Reimagining the Anglo-Scottish Border. Revista Română de Geografie Politică, 11, 29–36.

Paddison, R. (2009b). Some reflections on the limitations to public participation in the post-political city. L’Espace Politique, 8, 1–15.

Paddison, R. (2009c) The other Glasgow: Reflections on teaching a city. Scottish Geographical Journal, 125, 339–343.

Pollock, V. and Paddison, R. (2010). Embedding public art: Practice, policies and problems. Journal of Urban Design, 15, 335–356.

Paddison, R., Keenan, M. and Bond, S. (2012). Fostering inter-cultural dialogue: Visionary intentions and the realities of a dedicated public space. People, Place & Policy Online, 6, 122–132.

Pollock, V. & Paddison, R. (2014). On place-making, public art and participation: The Gorbals, Glasgow. Journal of Urbanism, 7, 85–105.

Paddison, R. and Rae, N. (2017). Brexit and Scotland: Towards a political geography perspective, SocialSpaceJournal (online): socialspacejournal.eu/13%20numer/Brexit%20and%20Scotland%20towards%20a%20political%20geography%20perspective%20-%20Paddison%20Rae.pdf

Boyle, M., Paddison, R. and Shirlow, P. (2018). Introducing ‘Brexit geographies’: Five provocations. Space and Polity, 22, 97–110.

Working papers

Abichou, H., Findlay, A., Findlay, A. and Paddison, R. (1981). The socio-professional characteristics of the residents of central Tunis. Glasgow: Department of Geography, University of Glasgow. Occasional Paper No.7.

Findlay, A. M., Findlay, A. M. and Paddison, R. (1983). Patterns of ethnicity and class in central rabat. Glasgow: Department of Geography, University of Glasgow. Occasional Paper No.12.

Findlay, A., Paddison, R. and Findlay, A. (1985). An appraisal of retail change within the cultural context of the Middle East. Stirling: University of Stirling. Occasional Paper.

Paddison, R. (1985). Some structural and spatial correlates of modern retailing in the third world city. Glasgow: Department of Geography, University of Glasgow. Occasional Paper No.16.

Paddison, R. (1988). Ideology and urban primacy in Tanzania. Glasgow: Centre for Urban and Regional Research (CURR), University of Glasgow. Occasional Paper.

Rogerson, R., Morris, A., Findlay, A. and Paddison, R. (1989). Quality of life in Britain’s intermediate cities. Glasgow: Department of Geography, University of Glasgow. Occasional Paper No.22.

Paddison, R. and Sharp, J. (2003) Towards democratic public spaces. Glasgow: Department of Geography and Geomatics, University of Glasgow. Online Paper (no longer available).