ABSTRACT

There has been a lack of coherent spatial thinking in policymaking in the UK due to political and economic considerations. This discussion, based on a spatial planning perspective, explains how the UK government’s often aspatial approach to policymaking and hiding behind the façade of market-led ideology does not stand the test when examining the R&D regional expenditure patterns. It also illustrates that complex layers of administrative boundaries have created a confusing governance structure and closed development possibilities. It finally sheds light on the experience of being a critical friend of the policy community to engender mutual learning.

Introduction

The dialogue about the relationship between geography and public policy is not new and there are both external and internal factors that drive the debate. There has been increasing external pressure on academics to demonstrate the societal impact of their research through routine assessments of engagement and impact, with Australia, Hong Kong and the UK as some examples (e.g. Given et al., Citation2014; Penfield et al., Citation2014). Research co-production and co-creation with government and policy partners is encouraged and used as assessment criteria by research funding bodies across Europe. There has also been introspective reflection among social scientists as engagement in policy projects could be seen as compromising scientific integrity (Berger & Kellner, Citation1981). This was echoed in the early 2000s debate over the ‘policy turn’ in geography (see Imrie, Citation2004). Both the sceptics and the advocates of this policy turn have good reasons for their views. I would like to join the debate as a spatial planner, more akin to the applied geographical perspective (Boyle et al., Citation2020), to look at the relationship between spatial thinking and policymaking.

While geographers such as Sheppard (Citation2015) have provided more nuanced and philosophical meaning of ‘thinking geographically’ from different ontological, epistemological and methodological perspectives, spatial thinking in planning terms is simply about the process to explore, understand, interpret, and express patterns of spatial distribution and relationships and to articulate the spatial configuration of such relationships in maps and plans. The emphasis on understanding the spatially-articulated processes and relationships very much follows the Geddesian tradition of regional thinking (Geddes, Citation1915) and echoes the notion of ‘relative space’ in geography literature (see Van Meeteren, Citation2021). Spatial planning can be seen as ‘more centrally concerned with the problem of coordination or integration of the spatial dimension of sectoral policies through a territorially based strategy’ (Cullingworth & Nadin, Citation2006, pp. 91–92).

The discussion here, based on a spatial planning perspective, aims to explain how the UK government’s aspatial approach to policymaking, often hiding behind the façade of market-led ideology (Marshall, Citation2011), does not stand the test when examining the R&D regional expenditure patterns. It then highlights how the complex layers of administrative boundaries and the confusing governance structures have closed development possibilities. Finally, the paper shares my own experience as a critical friend of the policy community to engender mutual learning through the Map for England initiative (Wong et al., Citation2012) with the Royal Town Planning Institute.

Space blind policy alleyway: the market argument

Many UK government policies and programmes, such as the National Transport Investment Strategy (DoT, Citation2017), have strong spatial expression or, more importantly, significant spatial consequences. Yet, these expressions and consequences could potentially be hidden given that the spatial information is often scattered throughout different sectoral policy documents and are contained within a range of formats. They also aim to set out general policies to be translated into local and regional policies and initiatives. The reason for a centralised government shying away from articulating spatial thinking involves both political and economic considerations. Central government is keen to steer away from local catfights and, by deliberately adopting a non-spatial approach, it can desensitize the political nature of its decisions such as major infrastructure investment projects (Wong & Webb, Citation2014). This is further reinforced by the entrenched belief that ‘London is the goose that lays the golden eggs’ (Mulholland, Citation2010). Such an attitude sadly transcends political parties and any suggestions to upset the spatial status quo is taboo. The normal defence is that the market is responsible for the buoyant economy in London and its wider hinterland (Marshall, Citation2011). This London-centric spatial landscape is then reinforced by the Treasury Green Book, as its project evaluation methodology tends to ignore the regional economic context and discount longer-term benefits (UK2070 Commission, Citation2020).

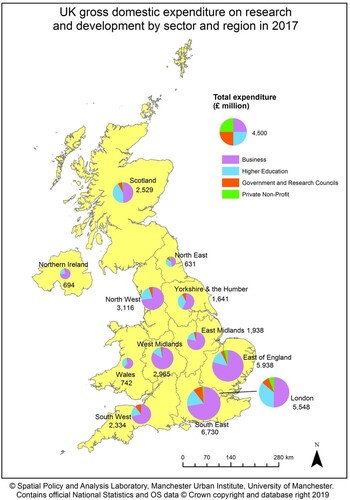

To verify this ‘market’ argument, the spatial patterns of the UK Research and Development (R&D) expenditure can be analysed (see Wong et al., Citation2019). As measured by gross expenditure on research and development (GERD), the UK spent £34.8 billion in 2017, accounting for 1.69% of GDP, which was below the European Union’s 2.07%. There are major variations in R&D expenditure across UK’s four constituent countries, with a spatial bias in the South East (19.34%), East of England (17.06%) and London (15.94%) accounting for over half of total expenditure (£18.2 billion); whereas the North East (1.81%), Northern Ireland (1.99%), and Wales (2.13%) together spent under 6% of the total. Of the three regions with most GERD spending, the business sector () dominates the East of England (78.76%) and the South East (72.21%), which contrasts sharply with London’s 50.4%. It is the government’s own R&D spending, as well as a large share of higher education spending, helps to boost the South East and London’s GERD.

As Forth (Citation2018) pointed out, the lack of government investment in lagging-behind regions outside London and the South East where significant business investment in R&D was found partly explained the move of AstraZeneca from Cheshire to East Anglia. This un/intended spatial bias of government funding, running against its market-led argument, is not a new trend. There was a major outcry in 2000 when the Labour government decided to base a £500m Diamond Synchrotron project at the Rutherford Appleton laboratory in Oxfordshire rather than at the Daresbury Laboratory in Cheshire which was then home to Britain’s only synchrotron (Radford & Watt, Citation2000). In 2008, there was another well-publicised row over the funding of a new light source facility between the Daresbury scientists (from Manchester and Liverpool Universities) and leading institutes in the golden triangle (Gilbert, Citation2008). This contrasts sharply with the spatial thinking articulated in the French National Research Strategy that regional funding allocations have to address scientific, technological, environmental and societal challenges, while maintaining a high level of basic research (Bitard & Zacharewicz, Citation2016).

Web of institutions and governance space: closing possibilities

The spatial co-ordination of land use and other development tends to occur at the lower tiers of the spatial hierarchy. There has been continuous shifting of the spatial scale of governance over the last twenty years, swinging from regional to local and then to the city-region. These administrative boundaries, nonetheless, do not define functional entities. The incongruence between accountable geographies of administrative areas and functional geographies (Solis et al., Citation2017) means that there is uncertainty over the actual spatial contextual effects on individual behaviours and outcomes.

Local Enterprise Partnerships (LEPs) are voluntary partnerships between local authorities and local businesses and have responsibility for a significant amount of central government funding. Although they are supposed to follow functional economic market areas, the reality is far more complex with some local authorities belonging to two LEPs, some LEPs over-lapping with each other and some just criss-crossing various travel-to-work-areas (Wong et al., Citation2019). Of course, the issue of LEPs is not just about geography, but a fragmented and shifting landscape of economic development governance (Pike et al., Citation2015). The under-performance of LEPs and government concerns over their problematic geographies (Ward, Citation2019) have triggered a review in 2021 with an uncertain future (Hill, Citation2021).

Besides LEPs, the formation of combined authorities with elected mayors has been seen by the government as a mechanism to stimulate economic growth outside London. The government again pins its hope that these new bodies should cover functional economic areas to develop robust strategy and policy (HM Government, Citation2018). However, out of ten combined authorities, only West Yorkshire and Sheffield have a good fit with their travel-to-work-areas (Wong et al., Citation2019). The most extreme example is the West Midlands Combined Authority, which has a poor fit with a number of travel-to-work-areas and involves 18 local authorities and 4 LEPs with different levels of voting right. This overly complex structure is confusing and is likely to cause duplications of effort over the development of economic and industrial strategies.

Both LEPs and combined authorities tend to be under-bounded spatial units that fail to fully capture or optimize the economic impact and synergy of the functional hinterland area (Robson et al., Citation2000; Wong et al., Citation2019). These under-bounded spatial units become an artificial barrier to policy delivery and run against the dynamic forces of spatial agglomeration which the government desires. Even with the spatial imaginaries of the Northern Powerhouse and the Midlands Engine, they are infrastructure-driven and project-led without any underpinning analysis of spatial connectivity nor long-term spatial planning to align with other policies and local concerns. This verifies the pertinent point made by Sheppard (Citation2015, p. 1118) that geographical thinking ‘must be open to a potentially unbounded multiplicity of spatialities, to be deployed in relation to, and intersecting with, one another’. Clearly, rigid administrative boundaries do not sit comfortability with the dynamic interactive understanding of spatial relationships.

How to be a critical friend?

The relationship between research and policy impact is often discursive, or even serendipitous. Promising research has often been ignored because ‘political circumstances or administrative personnel have changed, or simply because it comes too late’ (Pinder, Citation1980, p. 8). In the context of a very fast-moving policy environment, policymakers tend to consult experts who can make quick responses and the efficacy of research is dependent on its timing in relation to the life cycle of a policy or an administration (WSA, Citation1999). Research conducted with high technical proficiency and bringing critical and refreshing ideas has been found to be more highly regarded by politicians in the US (Weiss & Bucuvalas, Citation1980). Given the Treasury’s strong influence in shaping government policies and expenditure in the UK, it is true that quantitative research has gained more mileage than other forms of evidence, as argued by Imrie (Citation2004). However, we should not lose sight of the policy enlightenment role of research. Research may not be immediately used, but it can help to clarify and refine policy problems (Blackman, Citation1995).

In the planning field, there is an emerging consensus that different forms of knowledge should be deployed interactively and dialectically to address different decision situations (Hajer, Citation2003). The development of public participation GIS and online decision support systems has been very effective in stimulating debate and participation (Brown & Kytta, Citation2014). The Map for England initiative (Wong et al., Citation2012), led by the Royal Town Planning Institute, is such an example. It began with an exercise that systematically scanned policy documents and websites of different UK government departments and their agencies and non-departmental public bodies, covering a total of ninety-five relevant sources. By making the spatial relationships of government policies and programmes explicit through GIS mapping overlays, the Map for England was designed to encourage policymakers to visualize and gain a better understanding of spatial synergies and conflicts of sectoral issues. For a year or so, the initiative was met with enthusiasm in policy circles (e.g. invited presentation to the UK Central Government Geographers Group) and in the media (e.g. BBC Radio 4’s ‘Today’ and ‘You & Yours’ programmes). The importance of spatial findings was drawn upon by the Business Innovation and Skills Minister, Michael Fallon, and the Shadow Planning Minister, Roberta Blackman-Woods, to illustrate their points in the Growth and Infrastructure Public Bill Committee (29 November 2012). However without continuous research funding, the momentum of this spatial policy turn has waned in a rapidly changing policy world.

One lesson learnt from the Map of England is that methodological and technical complexity should be minimized to communicate our research messages in an effective and uncomplicated style, for example, with maps or other innovative media to capture policy users’ imagination. This mapping approach can be easily applied in different spatial contexts and was very well-received by practitioners in Europe and China at various international workshops and symposiums.

Conclusion

Government policies and programmes have wide ranging spatial implications and consequences, but there is often a lack of coherent spatial thinking to articulate their rationale or to consider the spatial outcomes of sectoral policy interactions on the ground. The malleability of the policy frameworks is also highly dependent on how they interact with the variable governance capacity and complex web of institutional structure and results in very uneven outcomes. While there have been short-lived place-targeted regeneration programmes and initiatives such as Growth Funds and City Deals, the nature of the synergies and conflicts within and between different policy agendas is not always immediately clear. The mapping analysis by Wong et al. (Citation2012), for example, revealed ‘sites’ of contradiction in Teesside and Liverpool where public expenditure cuts were not ‘offset’ at all through Growth Fund allocations. Academics, therefore, have an important role to play to expose these inequitable spatial outcomes to hold the government into account and to lead public debate. It may be a coincidence, but the government has now committed to increase its investment in R&D outside the Greater South East by at least 40% by 2030 in its Levelling Up White Paper (HM Government, Citation2022, p. 170).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Cecilia Wong

Cecilia Wong is Professor of Spatial Planning and Director of the Spatial Policy and Analysis Lab of the Manchester Urban Institute at the University of Manchester.

References

- Berger, P. L., & Kellner, H. (1981). Sociology reinterpreted: An essay on method and vocation. Anchor Books.

- Bitard, P., & Zacharewicz, T. (2016). RIO country report 2015: France, EU Joint Research Centre, Seville. https://rio.jrc.ec.europa.eu/sites/default/files/riowatch_country_report/FR_CR2015.pdf

- Blackman, T. (1995). Urban policy in practice. Routledge.

- Boyle, M., Hall, T., Lin, S., Sidaway, J. D., & van Meeteren, M. (2020). Public policy and geography. In A. Kobayashi (Ed.), International encyclopedia of human geography vol. 11 (2nd ed., pp. 93–101). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-102295-5.10731-0.

- Brown, G., & Kytta, M. (2014). Key issues and research priorities for public participation GIS: A synthesis based on empirical research. Applied Geography, 46, 122–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeog.2013.11.004

- Cullingworth, B., & Nadin, V. (2006). Town and country planning in the UK. Routledge.

- Department for Transport. (2017). Transport investment strategy: moving Britain forward. Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/transport-investment-strategy

- Forth, T. (2018). Boosting R&D, March 22. https://www.tomforth.co.uk/boostingrd/

- Geddes, P. (1915). Cities in evolution: An introduction to the town planning movement and to the study of civics. Williams.

- Gilbert, N. (2008). Should the golden triangle get all the research cash? The Guardian, May 20. https://www.theguardian.com/education/2008/may/20/highereducation.research

- Given, L. M., Winkler, D., & Willson, R. (2014). Qualitative research practice: Implications for the design and implementation of a Research Impact Assessment Exercise in Australia. Research Institute for Professional Practice, Learning and Education, Charles Sturt University.

- Hajer, M. (2003). Policy without policy? Policy analysis and the institutional void. Policy Science, 36(2), 175–195. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1024834510939

- Hill, J. (2021). Revealed: Government thinking on the future role of LEPs. Local Government Chronicle, June 14. https://www.lgcplus.com/politics/devolution-and-economic-growth/revealed-government-thinking-on-future-role-of-leps-14-06-2021/

- HM Government. (2018). Strengthened local enterprise partnerships. Ministry of Housing, Communities & Local Government. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/strengthened-local-enterprise-partnerships

- HM Government. (2022). Levelling up the United Kingdom, Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1052706/Levelling_Up_WP_HRES.pdf

- Imrie, R. (2004). Urban geography, relevance, and resistance to the “policy turn”. Urban Geography, 25(8), 697–708. https://doi.org/10.2747/0272-3638.25.8.697

- Marshall, T. (2011). Reforming the process for infrastructure planning in the UK/England 1990–2010. Town Planning Review, 82(4), 441–467. https://doi.org/10.3828/tpr.2011.26

- Mulholland, H. (2010). Boris Johnson urges David Cameron to shelter London from cuts. The Guardian, May 10. https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2010/may/10/boris-johnson-david-cameron-cuts

- Penfield, T., Baker, M. J., Scoble, R., & Wykes, M. C. (2014). Assessment, evaluations, and definitions of research impact: A review. Research Evaluation, 23(1), 21–32. https://doi.org/10.1093/reseval/rvt021

- Pike, A., Marlow, D., McCarthy, A., O'Brien, P., & Tomaney, J. (2015). Local institutions and local economic development: The Local Enterprise Partnerships in England, 2010. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 8(2), 185–204. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsu030

- Pinder, J. (1980). Policy and research II. Policy Studies, 1(1), 8–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/01442878008423297

- Radford, T., & Watt, N. (2000). Labour heartlands row as south gets hi-tech. The Guardian, March 14. https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2000/mar/14/uk.politicalnews1

- Robson, B., Parkinson, M., Boddy, M., & Maclennan, D. (2000). The state of English cities. Department for Environment, Transport & the Regions.

- Sheppard, E. (2015). Thinking geographically: Globalizing capitalism and beyond. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 105(6), 1113–1134. https://doi.org/10.1080/00045608.2015.1064513

- Solis, P., Vanos, J. K., & ForbisJr.R. E. (2017). The decision-making/accountability spatial incongruence problem for research linking environmental science and policy. Geographical Review, 107(4), 680–704. https://doi.org/10.1111/gere.12240

- UK2070 Commission. (2020). Make no little plans – acting at scale for a fairer and stronger future. http://uk2070.org.uk/publications/

- Van Meeteren, M. (2021). About being in the middle: Conceptions, models and theories of centrality in urban studies. In Z. P. Neal, & C. Rozenblat (Eds.), Handbook of cities and networks (pp. 252–271). Cheltenham.

- Ward, M. (2019). Local Enterprise Partnerships. House of Commons Library Briefing Paper No. 5651, March 28. https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/sn05651/

- Weiss, C. H., & Bucuvalas, M. (1980). Social science research & decision-making. Columbia University Press.

- Wong, C., Baker, M., Hincks, S., Schultz-Baing, A., & Webb, B. (2012). A map for England: spatial expression of government policies and programmes. Royal Town Planning Institute. http://www.sed.manchester.ac.uk/research/cups/map_for_england_final_report.pdf

- Wong, C., & Webb, B. (2014). Planning for infrastructure: Challenges to northern England. Town Planning Review, 85(6), 683–707. https://doi.org/10.3828/tpr.2014.42

- Wong, C., Zheng, W., Schulze Baing, A., Koksal, C., & Baker, M. (2019). Industrial strategy and industry 4.0: structure, people and place. Spatial Policy & Analysis Lab, University of Manchester. https://drive.google.com/file/d/1VYBNyyrOR_vP-W_BJIT6NLAObDgpMJ0F/view

- WSA. (1999). Review of the Local Government Research Programme. William Solesbury & Associates Research Management Consultancy.