ABSTRACT

City-centric planning in Sweden has led to the dominance of stereotyped visions for both urban and rural areas within policy and planning practice. To challenge such a limited understanding, this study conceptualizes the rurban void. The aim of this article is to operationalize the rurban void as an analytical framework that extends beyond the urban and rural conceptual divide and can clarify how a neoliberal and city-centric planning practice in Sweden de-politicizes the urban and rural outside. The article discusses the potentials of a perspective that challenges urban privilege and opens up opportunities for the re-politicisation of spatial transformation.

Introduction

During the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, Sweden underwent several waves of migration from the countryside to towns and cities. Up to the mid-1980s, these were mainly explained in relation to automation and rationalization in agriculture, forestry, and mining. Demographic changes were seen as the natural results of industrialization and the expansion of the modern welfare society (Enflo, Citation2016). Since then, other explanations have been added, such as the importance of the creative attractiveness of cities and the contrasting lack of culture, commercial activities, and public services in the countryside (Rönnblom, Citation2014; SOU, Citation2017, p. 1).

The consequences of this city-centric focus in planning policy and the domination of the urban have been critically discussed over the past few years within both planning practice and the international research community. For example, the homogenization of spatial transformation and city-centric perspectives on sustainable development (Angelo & Wachsmuth, Citation2020; Lefebvre, Citation2014; Robinson, Citation2013), the uneven distribution of resources caused by the spatial reconfiguration of planetary urbanization (Brenner, Citation2013; Citation2019; Schmid et al., Citation2018), the regionalization of urban governance and differentiated socio-spatial processes of regional urbanization (Jonas and Moisio, Citation2018; Keil et al., Citation2016; Pike et al., Citation2023), the exploitation and capitalization of natural resources (Johansen et al., Citation2015; Walker & Moore, Citation2019), the industrialization of the rural landscape (Scott et al., Citation2019), and new hybrid spatial conditions (Addie and Keil, Citation2015; Barraclough, Citation2013; Sieverts, Citation2003; Soja, Citation2000; Qviström, Citation2013; Waldheim, Citation2016).

But, despite the rich conceptualization of urban–rural spatial production and territorial inequalities, both practice and policy still tend to be locked within a conceptual, political, and academic dichotomy of urban and rural that risks reproducing stereotyped imaginaries of both the city and the countryside (Jazeel, Citation2018; Robinson & Roy, Citation2016). The current strong political focus on the urban middle classes produces imaginaries of a successful and sustainable society based on the city as the centre of a service-based economy, where economic growth is realized and cooperation can limit environmental impact (Brenner, Citation2015; Hult, Citation2017; Marsden, Citation2013; Tunström, Citation2009). These visions for the city are further enhanced by planning and design practices that promote attractivity for what Florida (Citation2002) describes as the ‘creative class’’ The urban is envisioned as a mixture of small-scale activities, cultural institutions, education, innovation, and entertainment (Fabian & Samson, Citation2016; Holgersson & Thörn, Citation2014). Simultaneously, the countryside is envisioned as attractive for an urban (and creative) class, with a small-scale cultural and agricultural landscape, organic food production, nature conservation and recreation (Johansen et al., Citation2015; Shucksmith, Citation2018). This city-centric perspective has been described in a Scandinavian context as an urban norm or urban privilege. The urban condition is seen as the norm, while ‘other places’, such as suburban and rural areas, are described as problematic and as representing the past (see for example Fredriksson, Citation2014; Rönnblom, Citation2014).

Overall, the city-centric urban privilege creates a romantic, elitist, and stereotypical reproduction of both the city and the countryside. On the other hand, it exposes a fragmented landscape of spatial conditions that do not correspond to the stereotyped imaginaries within planning practice and policy for urban and rural areas. With the ambition of challenging this binary understanding, we introduce the concept of the rurban void as an outsider position in relation to both the urban and the rural. At the same time, it is important not to see this void as physically empty, but rather as a discursive void and a territory of everyday spatial practices that are often neglected by policymakers and planning practices. By presenting an analytical framework for spatial production that extends beyond a binary simplification of city and countryside, and where the production of the rurban void is catalysed by the policies and practices of Sweden as a neoliberal welfare state, our objective is to encourage scholars and practitioners to highlight spatial conditions that lie outside of current urban and rural stereotypes. While recognizing existing conceptualizations and research, we hope to make visible the political consequences of the rurban void and to analyse the spatial articulations of urbanization from an outsider position (Robinson & Roy, Citation2016). Relations between the urban and rural, as well as what is conceived and communicated as being both urban and rural, can thus be challenged. Such challenges contribute to new knowledge about the ongoing reproduction of spatial inequalities and the acceleration of uneven geographical development. This is not to define the concept of rurban as a new spatial category, but rather to investigate and operationalize its analytical potential to reveal the dynamics of intersecting spatial power relations and contemporary spatial transformations.

Consequently, the aim of this article is to operationalize an analytical framework that can clarify and differentiate how neoliberal and city-centric planning practices in Sweden create a discursive void that de-politicizes the urban and rural outside, and how this makes it a frontline for economic and political exploitation. We also want to discuss the potential of a perspective that sees beyond the current industrialized and capitalized rationality and growth agenda. The following three questions guide our analysis: (1) What are the characteristics of the restructuring of the rurban void in-between urban and rural stereotypes? (2) What are the de-politicizing effects of these characteristics? (3) What are the potential openings for re-politicizing the rurban void?

We have chosen three municipalities in the western part of Sweden (Mariestad, Vänersborg, and Herrljunga) as our empirical examples. These allow us to demonstrate how the implementation of neoliberal governance models at national, regional, and municipal levels, geographical competition, and the use of economic trickle-down theory produce stereotyped urban imaginaries of large cities and regional centres on the one hand and the rural idyll on the other. In the next section, we present our theoretical framework on the politics of rurban spatial production, followed by a section on methods and the operationalization of the rurban void by describing our three empirical examples. The paper ends with two sections that illustrate how neoliberal urban privilege plays out in local practices and discuss how the rurban void can be re-politicized.

Neoliberal politics and spatial production of the rurban void

The neoliberal shift and geographical competition

The transformations in Sweden from the late 1960s onwards have been characterized by different strategies related to geographical differences and spatial transformation across the whole country (Björling, Citation2022). On the one hand, structural changes in the industrial and agricultural sectors during the late 1960s and early 1970s resulted in national politics focused on the lack of labour in the larger cities, and thus encouraged people to move from more remote and rural areas, while simultaneously ensuring that there were opportunities for living a good life in smaller rural communities (Enflo, Citation2016; Tidholm, Citation2014). The municipal reforms implemented after World War II and finalized during the 1970s can be seen as a manifestation of a political strategy that tried to rationalize welfare production in all parts of Sweden and smooth out the historical differences between urban and rural areas in order to create equal opportunities across the whole country (Boverket, Citation1994). The formal use of the terms ‘cities’ and ‘towns’ was replaced by the word ‘tätort’ for all densely populated settlements with more than 200 inhabitants. The number of municipalities was reduced from more than 2000 to approximately 290 and the articulated political ambition was to create opportunities for a good life for the entire population, not just for either urban or rural communities (Andersson, Citation2018). Similar ambitions could be found at that time in regional policies, where regions that had lost inhabitants, especially in the north, were compensated with initiatives from the state. Thus, different parts of the country were articulated as having different identities and were all part of the agenda for the political parties. Different places mattered when the Swedish welfare state expanded, and it was intended that the promises of the welfare state would be extended to all citizens, regardless of where in the country they lived (Tidholm, Citation2014).

But after the reforms of the 1970s and 1980s, there was a shift in policy during the 1990s, from regional support policies towards what political scientist Jörgen Johansson (Citation2013) calls a ‘regional competition policy’. Increasingly, each region, municipality, city, town, village, and country area was responsible for finding its own identity and competitive advantages and using them to make its territory a successful (and, later on, a sustainable) place. This shift, in turn, resulted in new public–private collaborations and territorial partnerships (Harvey, Citation1989). For example, the public sector may subsidize private investment by extending infrastructure and services (Cupers et al., Citation2020), or the increased privatization of the public sector is seen as a rationalization and a more efficient form of welfare production. Today, Sweden is one of the most extreme examples of a country where public activities have been passed into the hands of private business. Neoliberal forms of governing have entered the public sector, and through different forms of new public management – mainly through marketization and corporatization – the organization of the Swedish welfare state has been transformed (Öjehag & Granberg, Citation2019).

De-politicization of the public and the emergence of the rurban void

The consequences of these shifts towards a neoliberal form of governance are further analysed and explained by political theorists like Wendy Brown and Chantal Mouffe, who both discuss the ‘meltdown’ of political rationalities and market rationalities in terms of the de-politicization of the public. In her book, Undoing the Demos, Brown (Citation2015) examines the normative and constitutive power of governance, through devolution, responsibilization, and best practice. Brown (Citation2015, p. 126) argues that:

Governance replaces the opposition or tension between government and the private sector (sovereign and market relations) with collaboration and complementarity.

The strong national, regional, and municipal focus on economic development in Sweden is producing the city as more desirable than the countryside through a discourse of centralization and regionalization, geographical competition, clusters for innovation, and economic trickle-down logics (Fredriksson, Citation2014; Rönnblom, Citation2014). This focus on the city in turn catalyses the imaginaries of an urban renaissance and enhances an urban gaze within both regional and urban planning and design practice and policy. Visions and nostalgic interpretations of the dense, connected, and vivid urban lifestyle and the European historical city thus tend to be given a naturalized position as the successful and sustainable spatial target (Robinson, Citation2013; Tunström, Citation2009). This is true in both cities and towns, but also in the countryside, where the urban gaze promotes the landscape as being for recreational use, the preservation of natural and cultural values and the sustainable production of resources and goods for the urban middle class (Scott et al., Citation2019).

This privileging of the city and the urban elite further concentrates the focus of planning practices and politics on metropolitan areas as economic cores for economic and cultural growth, and on the rural idyll as a scenic landscape of recreation for the middle class (Shucksmith, Citation2018). The dichotomizing of urban and rural produces a poorly defined in-between void of plural spatial situations without articulated alternative imaginaries. The urban and rural are thereby enhanced as binary concepts alongside a stereotyped imaginary of both the city and the countryside. Overall, this reproduces dichotomies that tend to exclude a broader spectrum of spatial situations that do not correspond to the current political imaginaries of either the urban or the rural. This leads to a non-urban and non-rural heterogeneous and fragmented landscape that risks being played out as less valuable, unwanted, unsustainable, and problematic (Björling, Citation2016).

Emerging in the early twentieth century, the concept of the rurban has evolved through several definitions and has been used to describe areas that combine rural and urban characteristics (Galpin, Citation1918; Sorokin & Zimmerman, Citation1929). The concept is also used in different disciplines to define a rural–urban continuum (Dewey, Citation1960), peri-urban and ex-urban conditions (Gallent et al., Citation2009), fringe areas (Qviström, Citation2013), edge phenomena between urban and rural areas, and sociological hybrids of urban policy in agricultural areas (Marsden, Citation2013; Rattner, Citation1983). To further understand how gaps in between the binary spatial conceptualization are used for territorial processes, placemaking and potential spatial struggles, we find the rurban void to be a useful concept for creating a new position and the possibility of including a broader spectrum of practices and rationalities of governance and spatial production.

Spatial production and relational sense-making

During the last few decades, the domination of the urban perspective and the limitations of the urban–rural conceptual divide have been constructively discussed within the theoretical framework of planetary urbanization (Brenner, Citation2013). Building on the work of Lefebvre (Citation2003a), planetary urbanization conceptualizes the ways in which urbanization results in both concentrating and extending city-centric logics and thereby have a planetary impact on spatial transformation. According to Lefebvre (Citation1996, pp. 120–123), urban domination is the result of industrialization and urbanization. The socio-cultural opposition between urbanity and rurality is thus accentuated and the spatial opposition between town and country are lessened. But, in his work on the right to spatial production, Lefebvre (Citation1996, p. 120) also uses the rurban to name the confusion that appears when urban and rural life merge and differences in urban and rural production and consumption dissolve.

This is an interesting analytical lens on the perspective of the Swedish state which, during the second part of the twentieth century, actually tried to dissolve the differences between urban and rural through the expansion of the welfare state and the promotion of industrial development in order to ensure equal access to public services throughout the whole country (Bengtsson, Citation2020). The result today, of the historical transformation of Sweden since the sixteenth century, is a multifaceted and fragmented landscape of hybrid urban and rural conditions. The spatial transformation of cities, towns, and countryside, despite an urban domination and stereotyped visions of the dense and vivid future, is characterized by an industrial rationality in both urban and rural areas (Björling, Citation2022). In other words, urbanity as the eminent, and rurality as backward are articulated in national, regional, and municipal planning policy. Meanwhile, the spatial differences between the built environment in towns and in the country are lessened due to the mixing of urbanization and industrialization.

Building on the work of Lefebvre (Citation1996, pp. 118–121), we argue that the rurban void, employed as an analytical lens, can shift the critical discussion on the right to spatial production towards an analysis of ongoing spatial struggles in the fragmented, mosaic, and hybrid conditions of the rurban void in its own right (Barraclough, Citation2013). It is thus possible to further clarify the specific characteristics of spatial production outside of the few areas that fulfil the stereotyped visions of dense urban development and a recreational rural idyll.

In turn, it is useful to address Lefebvre’s (Citation1996) critique of the rurban confusion from the perspective of a relational approach to spatial production. Here, spatial sense-making and the formation of spatial identity is produced through spatial practices, structural hierarchies, and assemblages of material and discursive relations (see for example Brenner, Citation2019; Lefebvre, Citation2003b; McFarlane, Citation2011). The rurban void is thus to be seen as a nested spatial concept of different scales and a series of sites, territories, landscapes, and networks. Hence, we seek to render a dynamic position whereby a specific (rurban) spatial condition is not fixed in time and space, but rather is seen as a starting point for a deeper investigation of how material and discursive internal and external relations interact.

To expand our relational understanding of space, David Harvey (Citation2006, p. 124) emphasizes the need for both a material approach to spatial boundaries and characteristics and the dynamic sense-making aspects of space by adding relative interpretations and relational discursive frameworks. Furthermore, according to Doreen Massey (Citation2005), spatial sense-making depends on which spatial interpretation and narrative is prioritized. It is therefore problematic, according to Massey (Citation2005, p. 10), to plan and develop from just a few geographical centralities and a few sense-making perspectives and prerogatives, such as stereotyped visions of the urban and rural. For example, the rurban void risks being seen as meaningless, problematic, and unsustainable from a position situated within urban privilege (Björling, Citation2016, p. 83).

To summarize, here we are using the concept of the rurban void to define a point of departure for an open and dynamic assemblage of spatial relations that extend in both time and space. The rurban void as an analytical lens is thus nested between a broad spectrum of geographical territories, discursive articulations, interpretations, and spatial conditions. This approach makes visible how different processes both politicize and de-politicize the rurban void, depending on how it is subsumed into specific assemblages. The relational perspective is also central to understanding how the rurban void is not fixed, but is rather an ongoing process of sense-making, and how a politics of the rurban void is thus continuously unfolding and being negotiated.

In turn, this dynamic and productive approach to the rurban void opens up opportunities for new perspectives that can reveal the spatial conflicts and negotiations occurring in places and landscapes that we characterize as rurban, which is further discussed in the next section. Thus, we use the rurban void to highlight the potentials in hybrid situations of industrialized rural and urban logics for spatial production and everyday life (Lefebvre, Citation1996, Citation2003b). This implies a need to both critically clarify the discursive and material effects and implications of giving limited (stereotyped) spatial practices and imaginaries privilege, status, and interpretative prerogatives for the whole of society; and discuss the possibilities of re-politicizing spatial production in the rurban void. To do so, according to Lefebvre (Citation1996, p. 121), we need innovations of new urban and rural forms, inclusion, participation, and centralities free from degradation.

Operationalizing the rurban void through three examples

The exemplary method applied in Västra Götalandsregionen

The rurban void enables a discussion about spatial production beyond the dichotomies of urban and rural stereotypes, starting instead from an in-between socio-spatial peripheral position (Jazeel, Citation2018). Thus, in our analysis, we attempt to transgress the limitations of urban privilege and the hegemony of the middle class. To elaborate upon how the rurban void is used by actors and practices, and how the rurban void is produced and filled with meaning, we have applied what social theorist Brian Massumi (Citation2002, p. 17) calls the ‘exemplary method’. An example, according to Massumi, is neither general nor particular, but singular in that it belongs to itself. It is simultaneously possible to extend it to other examples with which it might be connected. Massumi furthermore stresses the need for detail, arguing that it is the details which together make up the example, create its singularity. We have chosen to use the exemplary method because we find it useful to test our analytical framework in relation to specific local situations – and to further develop our theoretical understanding through contextualizing our arguments in relation to local–regional spatial practices.

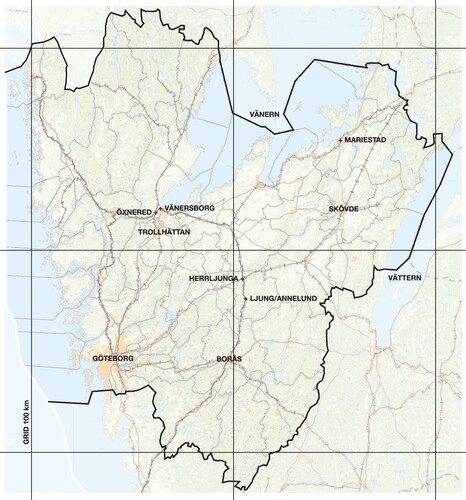

The three examples of Mariestad, Öxnered, and Ljung-Annelund in Västra Götalandsregionen in Sweden showcase different aspects of ongoing territorial processes, placemaking, and spatial conditions. The Västra Götaland region is Sweden’s largest region in terms of population, with just over 1.7 million inhabitants. It consists of 49 municipalities and was formed in 1998 through the merging of the former counties of Bohuslän, Älvsborgs län and Skaraborgs län (). The ambition of this new organization was to establish a more efficient regional administration. Gothenburg, Sweden’s second largest city (580 000 inhabitants in the municipality), worked actively to become more central within its own administrative region (Business Region Göteborg, undated report).

Figure 1. The West Sweden region (Västra Götalandsregionen) and the location of the three examples: Mariestad, Öxnered and Ljung-Annelund.

The material for the examples we have used was gathered through an analysis of policy documents, interviews, and workshops connected to four different projects: (1) The sub-regional planning process in Skaraborg Federation of Municipalities (2014–2016); (2) Participation in the comprehensive planning processes in the municipality of Mariestad (2016–2019); (3) The regional and municipal infrastructural planning along two railway lines in the Västra Götaland region (2017–2021); and (4) The urban transformation of Älvstaden in Gothenburg (2018–2020).

Mariestad – planning for the large company

Mariestad is located in the north-eastern part of Västra Götalandsregionen and has approximately 24 000 inhabitants in the municipality, of whom 16 000 live in the central town. The local economy has mainly developed around a handful of large industries. The relocation of production to other regions of Sweden and to other countries in Europe has caused the local economy to shrink and slowed population growth during the last few decades. Mariestad was also the former capital of the county of Skaraborg, and since 1998 it has tried to rebuild its common identity and initiate an industrial renewal based, among other things, on the production of hydrogen (Björling, Citation2016). The shifts in administrative regions and new centralities in the labour market due to regionalization and centralization, as in the majority of Swedish municipalities, has led to a stagnation in population and forecasts of the need for a more efficient production of welfare services. Population growth, in relation to the Swedish system of tax distribution, is seen as key to improving the balance of the local economy and municipal budget (Mariestad, Citation2018).

Statistical analysis for Mariestad forecasts a population growth of around 600 new inhabitants by 2030 (Mariestad, Citation2018). But the political ambition described in the municipal comprehensive plan is to enable around 2000 new housing units and a population growth of around 4000 inhabitants. This local political goal is calculated from the prognosis of the need to build 700 000 new housing units in total in Sweden (Boverket, Citation2017). The difference between 600 and 4000 new inhabitants is addressed as a future of uncertainty in the comprehensive plan. It also showcases how the focus on growth is pushing the municipality to actively facilitate the attracting of external investment from the private sector (Mariestad, Citation2018).

One example of how the municipality is working actively with industrial renewal and to attract external investment is the process around the establishment of a new battery cell factory in Europe in 2017. In March 2017, the company Northvolt announced a competition and ‘site selection process’ for a new facility. Mariestad and nearby Skövde municipality (55 000 inhabitants) joined forces to present a common application in which they highlighted the sub-regional scale of Skaraborg to fulfil the technical and qualitative demands. The regional mosaic of towns and countryside was used to answer to requirements such as the distribution of (clean) energy and access to clean water, technical partnerships (recycling and sustainable processes), and customer and supply perspectives with, for example, the car and mining industries (Business Region Skaraborg, Citation2021). The agricultural landscape was used to illustrate the availability of sufficient land to build the factories, and the cultural and natural landscape of the rural idyll was used to showcase attractive areas for housing (). For example, the characteristic table mountains in the region and the lakes Vänern and Vättern, together with the commercial services, shopping, and cultural institutions available in the towns were used to communicate the local and sub-regional attraction. The regional geography and landscape were presented as a place with the capacity to attract the highly qualified personnel needed for the investment. This regional imaginary was used to showcase the need for political investment from the surrounding municipalities, the region and the state to balance national economic development (Business Region Skaraborg, Citation2021).

Figure 2. An example of the images presented by Mariestad Municipality to illustrate the potential for external investment (Illustration: Mariestad Municipality, (Mariestad, Citation2017)).

After the first round of the qualification process, eight municipalities were selected in 2017, and the people responsible for the factory went on tour to see where the most attractive bids were being presented. In this way, the municipalities opened up the local–regional landscape as a playing field for this large company. This enabled private interests to play the municipalities against each other, clarify, and limit restrictions and choose the most attractive offer. Large private actors could thus make use of the fragile situation of a stagnating population and increasing costs of welfare provision. The ‘need’ to communicate attractiveness and promote the local situation as the most attractive one for external investment leaves limited room for a more critical analysis of the structural changes behind stagnation and de-growth. The private initiatives and the large company can dictate the rules of the public planning process. For example, private investors can influence the municipal plan for industrial land-use, despite conflicts with regional sustainability goals and environmental protection. To simplify exploitation and potential communication, the site of the new battery cell factory was proposed for agricultural land and forests along the major road E20 (Mariestad, Citation2018).

According to Northvolt, Mariestad, as the ‘countryside’, was generally interesting as a site for exploitation because there was no competition from other companies, and Mariestad in particular was seen as an example of a town that has managed structural transformation before (interview in Falköpings tidning 18 May 2017). After the second round of the site selection process, during the summer of 2017, Northvolt finally chose Västerås and Skellefteå as the two sites for its factories in Europe. Thus, the process in Mariestad is an example of how the municipalities are responsive to private interests. The strategic capacity shifts from the public to the private sector. Thus, the main paragraph in Swedish planning legislation, that equal consideration should be given to both communal and private interests (PBL, Citation2011) is limited, and private investments are instead seen as common interests because they may create new job opportunities and local economic growth, leading to population increase.Footnote1

Öxnered – Planning for the big city

The second example, Öxnered, is a residential area to the west of the town Vänersborg in the north-western part of Västra Götalandsregionen. Vänersborg is also a former capital of the county (Älvsborg) and, similarly to Mariestad, has developed strategies for its new identity since the establishment of Västra Götalandsregionen in 1998. The settlements in and around Öxnered have around 700 inhabitants, and 39 000 people live in the municipality of Vänersborg. The settlement in Öxnered has developed around the railway station, established in 1860 at the junction of two railway lines, and is located along the shores of the small lake Vassbotten. According to the municipality, the plan for new development in Öxnered is related to potential created by recent investments in the railway to Gothenburg (Vänersborg, Citation2016). The railway as a connection to the big city and its labour market is seen as having the potential to fulfil the municipal vision of population growth to 50 000 inhabitants by the year 2030.

Achieving these goals requires, among other things, conscious investment in housing in such attractive locations that few can compete with Vänersborg. (Vänersborg, Citation2006)

One of the prioritized corridors for investment is the valley along the Göta River (GR-kom, Citation2008). Roads and railways in the river valley connect Gothenburg with a string of smaller settlements, as well as the towns of Trollhättan (60 000 inhabitants) and Vänersborg. Further afield, the railway extends into both Norway and the region of Värmland. The link between Gothenburg and Trollhättan/Vänersborg has been promoted for a long time, with the arguments of regional economic development and the need to enlarge the local-regional labour markets. However, this development did not take off until the American car manufacturer GM clarified that its plans for one mid-sized European car factory was evaluating the SAAB factory in Trollhättan and the Opel factory in Rüsselheim in Germany. The competition called for national action, and in 2004 the Swedish state initiated a national ‘rescue programme’ for the car manufacturer SAAB in Trollhättan (Jonsson, Citation2008).

The new rail and infrastructural investments benefitted several smaller towns and stations between Vänersborg and Gothenburg, among them Öxnered (Björling & Capitao-Patrao, Citation2021). The initiatives taken by the state, the region and the city of Gothenburg increased the number of trains and highlighted Öxnered as a commuting town, where the stations were seen as the gateway to urban society (GR-kom, Citation2008). The station, and the access it provided to the labour market and commercial services in Gothenburg, in combination with the town’s countryside location beside the lake, are seen by the municipality as a way to attract new residents, and therefore a central part of marketing Vänersborg and the municipal plan for future growth (Vänersborg, Citation2017).

The possibilities for a future (middle-class) population to live close to both the water and access to Gothenburg is part of how Öxnered is discussed by the municipality as a sustainable urban development. The investment in the railway can be seen as a regional ‘wedge’ in the local context between Vänersborg and Trollhättan because the focus is directed towards commuting to Gothenburg, rather than the two smaller towns (Björling & Capitao-Patrao, Citation2021). The regional policymaking and national infrastructural investments can be seen as dominated by the prerogatives of Gothenburg and the urban visions of a sustainable and successful development, but at the same time with a focus on the idyllic rural living environment along the lake in Öxnered. The development is also based on an industrial rationality, whereby competitiveness is created by enlarging the labour market and scaling up production and consumption. In this way, the spatial transformation builds on a fragmented landscape of infrastructure, settlements, agricultural heritage, lakes, and natural reserves.

The infrastructure development process that started at the beginning of the 1990s has gradually shifted from a technocratic proposal for infrastructural investments based on prognosis and political decisions about the distribution of investment to the different regions to political arguments in favour of regional enlargement and economic growth (Jonsson, Citation2008). This political and administrative negotiation is catalysed by the new regional body of Västra Götaland and NGOs in Gothenburg that emphasize the development of the city as the regional core and ‘growth engine’ for West Sweden (GR-kom, Citation2008). Gothenburg is using the regional scale to strengthen its hierarchical position, but equal terms are not available for Vänersborg or Trollhättan, and especially not for Öxnered, which is being enhanced as a periphery of the regional labour market, rather than positioned at the centre of its own regional context.

Ljung-Annelund – pleasing the urban

The third example, Ljung-Annelund, consists of small twin towns with 1200 inhabitants in the municipality of Herrljunga (9500 inhabitants) in the central part of Västra Götalandsregionen. The municipality has a decreasing population due to ageing and migration to metropolitan areas in Sweden (Ekonomifakta, Citation2021). To turn this decline around, the municipality is trying to make use of its ‘central’ regional location in ongoing planning (Herrljunga, Citation2017). Ljung-Annelund, together with the main town of Herrljunga (4000 inhabitants), are seen by the municipality as strategic locations due to their railway stations and accessibility to Borås (110 000 inhabitants), one of the larger cities in Västra Götalandsregionen.

The twin towns of Ljung-Annelund are characterized by a mature manufacturing industry and the towns receive incoming commuters from the surrounding area to three large workplaces. There is childcare and a primary school, a fire station, dental health, a municipal library, and a senior citizens’ home in the twin towns. Public transport is by bus and train. Commercial services are limited to a grocery store, a pizzeria, a petrol station, a paint store, and a store selling products for the agricultural sector.

The municipality sees potential in Ljung-Annelund due to the significant number of employees in its larger companies. However, there is weak demand for new housing, and it is difficult to get loans to finance new houses and buildings because the prices of existing houses are low. The situation is more positive in Herrljunga, the central town in the municipality, and here the planning process is more active and municipal initiatives are prioritized. However, the comprehensive plan still outlines a potential for 100 new housing units in Ljung-Annelund. The plan is to make it possible to have a denser development around the railway station to increase commuting using public transport and to enable more commercial activities, thereby creating a more attractive living environment (Herrljunga, Citation2017).

The overall municipal objectives are to strengthen efficiency in transportation, technical infrastructure, education, and healthcare by trying to concentrate the population (Herrljunga, Citation2017, p. 12). This vision has been inspired by spatial strategies developed for the densification of suburban areas in the metropolitan region, such as transit-oriented development (Björling & Capitao-Patrao, Citation2021). But the lack of pressure for new investment and uncertainties about real-estate exploitation make municipal planning strategies and initiatives abstract. The imitation of urban planning strategies and slow spatial transformation creates a gap between the visions presented in planning documents and concrete implementation and physical transformation (Björling & Capitao-Patrao, Citation2021).

Public transport services are also concentrated around the larger towns and metropolitan areas in the region to increase efficiency in public investment. These processes of market-driven centralization of the public welfare system create a local sense in Ljung-Annelund of being abandoned by the public sector, despite the comparatively strong local economy with its manufacturing industry (Björling & Capitao-Patrao, Citation2021). Places like Ljung-Annelund, which are located outside of clear distinctions between urban and rural areas, are displaced to a peripheral position in regional planning. Thus, Ljung-Annelund can be seen as an example of how qualified visions for the rurban void are lacking in municipal and regional planning. Ljung-Annelund does not fit into the stereotyped visions of either urban or rural sustainable and attractive development, and the area is thus located in an in-between gap in planning policy and practice. The municipal planning tries to solve the perceived problem of lack of attractiveness by adding new houses or infrastructure. At the same time, regulations for agricultural land and nature reserves restrict physical development (Björling & Capitao-Patrao, Citation2021). The planning process thus risks being limited by stereotyped and homogenizing visions of a sustainable development that renders the local situation into a non-urban and non-rural ‘outside’. This misses the opportunity to build on existing resources, practices, and potential spatial struggles that could enable a politicization of alternative goals and strategies for how the local labour market, services, or local communities can be maintained and strengthened. It can be seen as a situation in which no public institution is interested in governing the politics of place, thus leaving the rurban void open for ‘other’ actors.

De-politicization of the rurban void

What we see today in Sweden at an overall level is a divergence between the political visions of an attractive, dense, inclusive, and productive urban space and recreational rural idyll on the one hand and the economic rationality of spatial production on the other. Taken together, we argue that, although, to a certain extent, our three examples are meeting different challenges and have taken on different strategies, it is possible to discern three common effects of how neoliberal planning and urban privilege are restructuring the rurban void. These are principles that together form the logics of: (a) adjustment for others, (b) flexibility for others, and (c) the imitation of urban and rural stereotypes.

Adjustment for others

Let us start with adjustment for others. In Mariestad, there is constant adjustment to fulfil the requirements of external actors, especially potential future investments by the large company. The fragile situation that follows from population stagnation, within a Swedish planning framework that was established to regulate population growth, forces local planning to establish the best conditions for external actors and thereby limits the opportunities for improving the situation for local citizens or local companies.

In Öxnered, the adjustment is mainly focused on developing the right infrastructure and making use of the new topological relationship to become a place within the regional context of Gothenburg that is easy to leave – and easy to come back to. Building new housing close to the railway station and the lake is a strategy for promoting access to infrastructure and creating flexibility for the inhabitants to commute to work in an urban area, and hopefully also to attract new citizens.

Flexibility for others

Both Mariestad and Öxnered focus on external factors – either with the ambition of attracting big players like large companies or the large city, or to attract new citizens. This focus not only means adjusting to the needs and demands of others, as they are articulated or imagined, but also relates to our second principle: flexibility for others. If a large company wants land to build on, it will get land. If the large city demands improved infrastructure, it will get improved infrastructure. This means engaging in flexible neoliberal planning whose attention is focused beyond the people already in place and where public investment creates a frontline for subsidized private exploitation. The logic of the rurban void becomes building and planning for others, producing a convenient stage for external actors to use. This brings us to our third principle, imitation of urban and rural stereotypes, which is also part of both the adjustment for others and the flexibility for others.

To imitate or please

Of our three examples, Ljung-Annelund is the clearest example of the gap between visions of spatial transformation and the almost non-existent pace of implementation. This position highlights a central dilemma for the rurban void, whereby the spatial imitation of stereotypes is impossible but still desirable as a vision. Planning for urban potential and imitating urban planning also means missing what is already there. The development of local structures that are already in place, and also functioning for the inhabitants who are already there, becomes silenced in favour of a longing for the other. It also renders the people who stay on invisible, or at least uninteresting. Here, a kind of paradox is produced. The ambition is to imitate the urban, or to please its actors, at the same time as there is a need to provide something extra, something that could not previously be found there. There is an implicit demand to maintain the local small-town culture or rural idyll in order to be attractive, at the same time as there is a need for constant growth so as to be included as successful and sustainable within the modern idea of expansion.

A frontline for exploitation

The processes described in Mariestad, Öxnered, and Ljung-Annelund can be seen as a continuation of the political agenda of the Swedish welfare state: to catalyse competitiveness and safeguard the long-term opportunities to make use of national resources. Ongoing exploitation of the rurban void as a socio-economic playing field can thus be seen as an inherent logic of the Swedish regional competition policy and new public management. This approach highlights what Mouffe (Citation2013) terms pain-free politics and makes it almost impossible to politicize place-related conditions. It is a situation that, on one hand, acts in favour of the elite and strives to create attractive spaces for urban elites who can move freely between the city and countryside. On the other hand, it also favours industrial exploitation and makes the rurban void into a territory for the extraction of resources, services, and labour. This is a development that reduces the space for other imaginaries of a good society and limits the agency for places in the rurban void to set an agenda of their own and become an active space for spatial struggle. Hence, the spatial transformations that we see in the three examples showcase what Brown (Citation2015) has highlighted – that governance practices replace the political tension between public and private sectors. The ‘correct’ solutions asked for in public–private partnerships depoliticize the process by excluding alternative spatial production through framing them as naïve and inappropriate.

The rurban void is in turn established as an outside to both the urban and the rural. The fragmented and homogenized landscape of industrial agriculture, forestry, infrastructure, and settlements is not included as successful in the stereotyped visions of sustainable urban and rural transformation, but it is still part of the economy to be exploited and made use of. The rurban void exemplifies what Walker and Moore (Citation2019) describe as a cheap frontier for exploitation. To develop surplus value, the capitalist economy is constantly searching for ‘commodity and capitalization frontiers’ outside of the already-capitalized areas of production. This implies not only a need to exploit labour and nature within the realm of the economy, but also to make use of resources outside of ongoing capitalist production (Walker & Moore, Citation2019). Actors in the rurban void both try to imitate and desire to please external actors and, hence, to be included in the discourse of the successful and sustainable society. The municipal opportunity to ‘attract’ the large company, the large city, or the state, apply urban approaches, and highlight urban values tends to blind planners and politicians to the inclusion of other local resources, i.e. the participation of the populations and companies that already live and operate on the site. Instead, there is a risk of exclusion and inability, as well as limitations being placed on the use of local resources, competencies, and decision mandates for local development.

The hegemony of a binary conceptualization of, for example, centre–periphery, town–country, and urban–rural enhances an in-between void without clear articulation or spatial sensemaking. Following Walker and Moore (Citation2019), the production of dichotomies such as, for example, man and woman, white and non-white, society and nature can be seen as an internal logic of capitalism that is designed to create uneven power relations. Thus, alternative articulations of positions within the rurban void can open up opportunities for a critical discussion of spatial power relations as a set of several serialities and also enable an intersectional analysis of the urban-rural divide. Through a focus on the spatial conditions within the rurban void, alongside other power relations such as class, gender, race, and sexuality, we see the potential for an analytical strategy in which power relations intersect, and thus cannot be separated (Rönnblom, Citation2008; see also Crenshaw, Citation1991).

When pushed to the outside, by the state, the region, and the municipality, which are the public actors in the Swedish welfare state, the rurban void opens to new actors. These are, on the one hand, those who seek the opportunity to exploit the subsidized economic frontlines and actors who make use of the depoliticized rurban void and the local desire for inclusion to counteract the liberal and democratic society. On the other hand, they are actors who make use of the outside as an opportunity to develop alternative practices. Overall, this leads to a spatial transformation that makes it possible to initiate a discussion about the potential for the re-politicization of places in the rurban void.

Re-politicization of the rurban void

Analysing our three examples, the rurban can today be seen as a playing field upon which there are three categories of strong players acting – the state, the large company, and the large city. Together, this triad tends to (re)produce the prevailing, and de-politicized, neoliberal order, where ‘good solutions’ replace the political. This results in basically just two options – to imitate the urban or please urban interests. This is a competition that actors in the rurban void have difficulties in winning within the industrialized welfare state and globalized economy. But the rurban void is also in potential flux. There are actors with the potential to intervene and politicize it – for example, civil society organizations, politicians, entrepreneurs, and enterprises, as well as other aspects of the state. By articulating the rurban void, new alliances between public, private, and non-profit actors can start from a simultaneously in-between and socio-spatial peripheral position.

To make use of this situation, there is an opportunity to take advantage of the dynamics between material and discursive practices. This could serve to gradually expand and challenge the stereotypical imaginaries of city and countryside by including resources, competences, and actors from a broader spectrum of the rurban void. A productive and relational understanding of rurban place enables a reciprocal relationship between a critical operationalization of the depoliticized rurban void and the step-by-step testing and implementation of counter actions. A critical spatial practice can bring into being alternative approaches to spatial production that in turn both constrain and make possible societal change. The rurban void is a fragmented and heterogeneous landscape of diverse actors and resources that can showcase the potential of spatial production beyond stereotyped visions of the urban and rural. Its positioning outside of city-centric planning practices make it possible to think beyond an urban horizon and current processes of concentrating and extending urbanization.

Hence, we encourage planners, politicians, grassroots actors, and scholars to make use of the rurban void as an analytical lens to articulate a mosaic of spatial production in its own right; to establish spatial practices that intentionally renounce control in order to include opportunities for other actors to participate and articulate alternative centralities. Hence, the rurban void can be seen as a potential landscape for the re-politicization of contemporary spatial struggles. Through articulating the rurban void, new details about the spatial restructuring of urban privilege become visible and thus possible to challenge.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Nils Björling

Nils Björling is Senior Lecturer in Urban Design and Planning at Chalmers university of Technology in Gothenburg.

Malin Rönnblom

Malin Rönnblom is Professor in Political Science at Karlstad University. Current collaboration and research focus on the ongoing industrial transformation of Sweden and the possibilities for the municipalities to make visible and balance local, municipal and regional ambitions and the interests of both private and public, national and international actors.

Notes

1 During the review process for this article, the company Volvo Trucks decided to choose Mariestad as its location for a new battery factory for trucks and buses. The preparations made by Mariestad municipality for Northvolt could be used and played out as an opportunity for another giga-factory and industrial renewal.

References

- Addie, J.D., & Keil, R. (2015). Real existing regionalism: The region between talk, territory and technology. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 39(2), 407–417. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12179

- Andersson, P. (1993). Sveriges kommunindelning 1863–1993. Draking.

- Angelo, H., & Wachsmuth, D. (2020). Why does everyone think cities can save the planet? Urban Studies, 57(11), 2201–2221. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098020919081

- Barraclough, L. (2013). Is there also a right to the countryside? Antipode, 45(5), 1047–1049.

- Bengtsson, E. (2020). Världens jämlikaste land? Arkiv förlag.

- Björling, N. (2016). Sköra stadslandskap – planeringsmetoder för att hantera urbaniseringens rumsliga inlåsningar. Diss. Göteborg: Chalmers tekniska högskola.

- Björling, N. (2020). Belysning av det svenska planeringssystemet genom jämförelse med planeringsprocessen i Älvstaden. Fusion Point.

- Björling, N. (2022). Planning for quality of life as the right to spatial production in the rurban void. In P. H. Johansen, A. Tietjen, E. Bundgård Iversen, H. Lauridsen Lolle, & J. Kaae Fisker (Eds.), Rural quality of life (pp. 215–231). Manchester University Press.

- Björling, N., & Capitao-Patrao, C. (2021). Sam-Sam – samskapande samhällsplanering för hållbara och energieffektiva stationssamhällen. Delstudierapport: Västra Götalandsregionen (Arbetspaket 1) Stockholm: KTH/Energimyndigheten.

- Blücher, G. (2013). Planning legislation in Sweden: A history of power and land-use. In J. Lundström, C. Fredriksson, & J. Witzell (Eds.), Planning and sustainable urban development in Sweden (pp. 47–57). Föreningen för Samhällsplanering.

- Boverket. (1994). Sverige 2009 – förslag till vision.

- Boverket. (2017). Beräkning av behovet av nya bostäder till 2025.

- Brenner, N. (2013). Theses on urbanization. Public Culture, 25(1), 85. https://doi.org/10.1215/08992363-1890477

- Brenner, N. (2015). Is ‘Tactical Urbanism’ an Alternative to Neoliberal Urbanism? http://post.at.moma.org Posted on March 24.

- Brenner, N. (2019). New urban spaces: Urban theory and the scale question. Oxford University Press.

- Brown, W. (2015). Undoing the demos: Neoliberalism’s stealth revolution. Zone Books.

- Business Region Göteborg. (undated report) Tillväxt i Göteborgsregionen – Ett underlag för regionens tillväxtstrategi. Göteborg: Business Region Göteborg.

- Business Region Skaraborg. (2021). www.businessregionskaraborg.se (Available 7 June 2023).

- Crenshaw, K. (1991). Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Review, 43(6), 1241–1299. https://doi.org/10.2307/1229039

- Cupers, K., Mattsson, H., & Gabrielsson, C. (2020). Neoliberalism on the ground: Architecture and transformation from the 1960s to the present. University of Pittsburgh Press.

- Dewey, R. (1960). The rural-urban continuum: Real but relatively unimportant. American Journal of Sociology, 66(1), 60–66. https://doi.org/10.1086/222824

- Ekonomifakta. (2021). www.ekonomifakta.se (Available 7 June 2023).

- Enflo, K. (2016). Regional ojämlikhet i Sverige. En historisk analys. SNS Analys nr 33.

- Fabian, L., & Samson, K. (2016). Claiming participation – a comparative analysis of DIY urbanism in Denmark. Journal of Urbanism: International Research on Placemaking and Urban Sustainability, 9(2), 166. https://doi.org/10.1080/17549175.2015.1056207

- Falköpings tidning. (2017). Jäklar anamma’ kan avgöra etableringen av batterifabriken. Falköpings tidning 18 May 2017.

- Florida, R. (2002). The rise of the creative class: And How it’s transforming work, leisure, community and everyday life. Basic Books.

- Fredriksson, J. (2014). Konstruktioner av en stadskärna: Den postindustriella stadens rumsliga maktrelationer. Diss. Göteborg: Chalmers tekniska högskola institutionen för Arkitektur.

- Gallent, N., Andersson, J., & Bianconi, M. (2009). Planning on the edge. Routledge.

- Galpin, C. J. (1918). Rural life. Century.

- Gr-kom. (2008). Strukturbild för Göteborgsregionen. Göteborgsregionens kommunalförbund.

- Harvey, D. (1989). From managerialism to entrepreneurialism: The transformation in urban governance in late capitalism. Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography, Vol. 71(1), No. 1, The Roots of Geographical Change: 1973 to the Present (1989), pp. 3–17. Blackwell. https://doi.org/10.1080/04353684.1989.11879583

- Harvey, D. (2006). Den Globala Kapitalismens rum: På väg mot en teori om ojämn geografisk utveckling. Hägersten: Tankekraft förlag.

- Herrljunga kommun. (2017). Översiktsplan för Herrljunga kommun. Herrljunga kommun.

- Holgersson, H., & Thörn, C. (2014). Gentrifiering. Studentlitteratur.

- Hult, A. (2017). Unpacking Swedish sustainability: The promotion and circulation of sustainable urbanism. KTH. Stockholm.

- Jazeel, T. (2018). Urban theory with an outside. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 36(3), 405–419. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263775817707968

- Johansen, P. H., Fisker, J. K., & Thuesen, A. A. (2021). ‘We live in nature all the time’: Spatial justice, outdoor recreation, and the refrains of rural rhythm. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences, 120, 132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2021.01.025

- Johansson, J. (2013). Regionalpolitikens utveckling: Mellan politisk kamp och ekonomisk nytta. In T. Mitander, L. Säll, & A. Öjehag-Pettersson (Eds.), Det regionala samhällsbyggandets praktiker. Tiden, makten, rummet (pp. 51–72). Bokförlaget Daidalos.

- Johansson, J., Rönnblom, M., & Öjehag, A. (2021). Democratic institutions without democratic content?-New regionalism and democratic backsliding in regional reforms in sweden. Frontiers in Political Science, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2021.711185

- Jonas, A.E.G., & Moisio, S. (2018). City regionalism as geopolitical processes. Progress in Human Geography, 42(3), 350–370. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132516679897

- Jonsson, J. (2008). Trollhättepaketet – En studie av beslutsprocessen för ett infrastrukturprojekt i samband med en industripolitisk kris. Magisteruppsats (CD 30 hp) i Statsvetenskap. Göteborg: Göteborgs Universitet Statsvetenskapliga institutionen.

- Keil, R., Hamel, P., Boudreau, J.-A., & Kipfer, S. (2016). Governing cities through regions: Canadian and European perspectives. Wilfrid Laurier University Press.

- Lefebvre, H. (1996). Writings on cities. Blackwell.

- Lefebvre, H. (2003a/1970). The urban revolution. University of Minnesota Press.

- Lefebvre, H. (2003b/1974). The production of space. Blackwell.

- Lefebvre, H. (2014). Dissolving city, planetary metamorphosis. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 32(2), 203–205. https://doi.org/10.1068/d3202tra

- Mariestad. (2017). www.mariestad.se (Available 7 June 2023).

- Mariestad. (2018). Översiktsplan 2030, Mariestads kommun 2018. Mariestads kommun.

- Marsden, T. (2013). Sustainable place-making for sustainability science: The contested case of agri-food and urban–rural relations. Sustainability Science, 8(2), 213–226. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-012-0186-0

- Massey, D. (2005). For space. Sage.

- Massumi, B. (2002). Parables for the virtual: Movement, affect, sensation (1st ed.). Duke University Press.

- McFarlane, C. (2011). The city as assemblage: Dwelling and urban space. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 29(4), 649–671. https://doi.org/10.1068/d4710

- Mouffe, C. (2013). Agonistics: Thinking the world politically. Verso.

- Öjehag, A., & Granberg, M. (2019). Public procurement as marketisation: Impacts on civil servants and public administration in Sweden. Scandinavian Journal of Public Administration, 23(3/4), 43–59. doi:10.58235/sjpa.v23i3/4.8635

- PBL. (2011). Plan och bygglagen (PBL) 2011:900. Sveriges riksdag.

- Pike, A., Béal, V., Cauchi-Duval, N., Franklin, R., Kinossian, N., Lang, T., Leibert, T., MacKinnon, D., Rousseau, M., Royer, J., Servillo, L., Tomaney, J., & Velthuis, S. (2023). ‘Left behind places’: A geographical etymology. Regional Studies. DOI: 10.1080/00343404.2023.2167972

- Qviström, M. (2013). Searching for an open future: Planning history as a means of peri-urban landscape analysis. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 56(10), 1549–1569. https://doi.org/10.1080/09640568.2012.734251

- Ranhagen, U., & Gustafsson, A. (2020). Det Urbana stationssamhället - vägen mot ett resurssnålt resande. Mistra Urban Futures Report, 2020, 3.

- Rattner, H. (1983). Rurban (rural–urban) communities: An appropriate technology for the settlement of migrants and slum-area dwellers in Brazil. In P. Fleissner (Ed.), Systems approach to appropriate technology transfer, pergamon, pp. 83–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-029979-2.50016-2

- Robinson, J. (2013). The urban now: Theorising cities beyond the new. European Journal of Cultural Studies, 16(6), 659–677. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367549413497696

- Robinson, J., & Roy, A. (2016). Debate on global urbanisms and the nature of urban theory. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 40, 181. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12272

- Rönnblom, M. (2008). How is it done? On the road to an intersectional methodology in feminist policy analysis. In GEXcel work in progress report, Vol. IV, Linköping University.

- Rönnblom, M. (2014). Ett urbant tolkningsföreträde? En studie av hur landsbygd skapas i nationell policy. Umeå universitet.

- Schmid, C., Karaman, O., Hanakata, N. C., Kallenberger, P., Kockelkorn, A., Sawyer, L., Streule, M., & Wong, K. P. (2018). Towards a new vocabulary of urbanisation processes: A comparative approach. Urban Studies, 55(1), 19–52. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098017739750

- Scott, M., Gallent, N., & Gkartzios, M. (2019). The routledge companion to rural planning. Routledge.

- Shucksmith, M. (2018). Re-imagining the rural: From rural idyll to good countryside. Journal of Rural Studies, 59, 163–172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2016.07.019

- Sieverts, T. (2003). Cities without cities: An interpretation of the zwischenstadt. Routledge.

- Soja, E. W. (2000). Postmetropolis: Critical studies of cities and regions. Blackwell.

- Sorokin, P., & Zimmerman, C. (1929). Principles of rural–urban sociology. Henry Holt & Co.

- SOU. (2017). 1, För Sveriges landsbygder – en sammanhållen politik för arbete, hållbar tillväxt och välfärd, Slutbetänkande av den parlamentariska landsbygdskommittén.

- Tidholm, P. (2014). Norrland. Teg.

- Tunström, M. (2009). På spaning efter den goda staden: om konstruktioner av ideal och problem i svensk stadsbyggnadsdiskussion (Diss). Örebro Universitet.

- Vänersborg. (2006). Översiktsplan. Vänersborg: Vänersborgs kommun.

- Vänersborg. (2016). Planprogram för Skaven och delar av Öxnered. Vänersborg: Vänersborgs kommun.

- Vänersborg. (2017). Översiktsplan 2017: Vänersborgs kommun.

- Waldheim C. (2016). Landscape as urbanism: A general theory. Princeton University Press.

- Walker, R., & Moore, J. W. (2019). Value, nature, and the vortex of accumulation. In H. Ernstson, & E. Swyngedouw (Eds.), Urban political ecology in the anthropo-obscene: Interruptions and possibilities (pp. 48–68). Routledge.