ABSTRACT

This paper analyses how the exploitation of tenants in Spain is boosting income for banks, hedge funds and pension funds. It does so by tracing the origins of the money invested in a Tres Cantos housing project in Madrid. The paper makes the following claims: First, the exploitation taking place in households -referred in this paper as secondary- is increasingly related to worker exploitation, and thus this particular type of exploitation is increasingly relevant to the dynamics of capital accumulation. Second, the key role of secondary exploitation of tenants in the revenue-making strategies of pension funds, hedge funds and banks is augmented and mediated by a myriad of regulations being implemented at the national and supranational scales. Theoretically, the paper contests the Marxian claim that household exploitation is ‘secondary’ to the exploitation taking place in the production process.

Introduction

One of the main features of the post-crisis housing political economy is the appetite of financial investors for rental housing and an increase in tenant displacement (Fields and Uffer Citation2016, Fields Citation2018, Wijburg et al. Citation2018). As Soederberg (Citation2018, p. 286) has pointed out, ‘the act of expelling tenants from rental property has become one of the most pressing social issues in contemporary capitalism’. Indeed, secondary exploitation -referred here as the exploitation taking place when a tenant (or a homeowner) becomes an inhabitant of a specific home- in the current post-crisis context is not only engineered through homeowner reliance on mortgages but also through tenant payments to landlords (Fields Citation2018, Soederberg Citation2018).

Secondary exploitation of tenants has become a key aspect of the Spanish housing market, as illustrated by the fact that evictions from rental properties have been more numerous than evictions from owned properties since at least 2013 (CGPJ Citation2018). Elaborating on the above insights, I engage with the post-crisis rental housing question by inquiring as to the nature of the ‘exploitation’ tenants are facing as their houses are acquired by hedge funds. Related to that, what has been the role of regulations in enabling such secondary ‘exploitation’ by hedge funds? I seek to respond to this question by tracing the origins of one financial corporation’s (Blackstone’s) investments into a housing project in Tres Cantos (Madrid, Spain) as well as the role post-crisis regulations have played in investment processes such as the one in Tres Cantos.

The paper thus analyses the multilayered economic processes and regulatory shifts which have boosted a large-scale process of rental housing stock acquisition by financial corporations and increased pressure on tenants to leave their homes. The article is therefore framed within literature focused on the political economy of housing, and particularly, on the blossoming literature on housing financialisation (Aalbers Citation2012, Citation2019, Fernandez and Aalbers Citation2016).

Within the literature on rental housing financialisation, the article makes one empirical and one theoretical contribution. First, it aims to contribute to the long-standing discussion about the ways through which the ‘exploitation’ of households takes place (Engels Citation1872, Pahl Citation1975, Aalbers and Christophers Citation2014). The article’s contribution is to prove that the secondary ‘exploitation’ taking place in the household is increasingly interrelated, if not dependent on the exploitation of labour when selling the ability to work to corporations. At the same time, it also proves that the exploitation in the wage-labour sphere is increasingly dependent on secondary exploitation. Second, it contributes to the literature on the role of the state in the financialisation of housing (Aalbers et al. Citation2011, Fernandez and Aalbers Citation2016, Yrigoy Citation2019) by dissecting the role of monetary easing from central banks in strengthening the link between the exploitation happening at the household level and the wider economic processes.

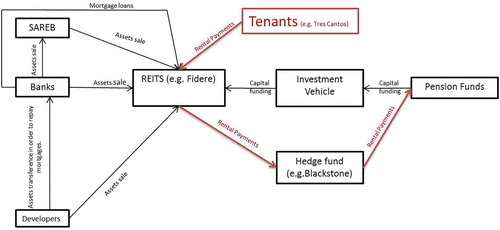

This study has adopted a mixed case study design. On the one hand, quantitative data from the Bank of Spain and the Land Registry statistical service regarding evolution of mortgage loans and the share of salaries used to pay mortgage loans has been used to grasp the post-crisis transition from a secondary exploitation model based on extracting wages via mortgage loans to a post-crisis secondary exploitation relying on rental payments. On the other hand, a combination of Newspaper articles, policy documents and specially, corporate annual reports have been analysed to explore the practices of hedge funds in the Spanish rental market, and particularly, of Blackstone and its subsidiary Fidere in Tres Cantos project. Blackstone and Fidere have been chosen because they are respectively the largest investor in Spanish housing (Blackstone) and Fidere is one of Blacktone’s spin-off that has all its financial reports publicly available. The information obtained by financial reports and new feeds has been complemented by two databases. First, Aura Real Estate database containing the main real estate transactions in Spain has been used to track down the type of assets traded by hedge funds, and specifically, Blackstone and Fidere. Moreover, SABI database, which contains all the key economic information of all corporations registered in Spain, has been used to verify and complement Fidere’s information regarding its profits and debts. The Tres Cantos project is used in the article as the example to explain post-crisis secondary exploitation taking place in Spain for a very pragmatic reason: it is Blackstone’s project in Spain which has raised more interest in different media outlets, and thus, more secondary information is available. Information regarding post-crisis regulations and pension funds has been obtained from secondary sources and particularly from official reports mainly by the European Central bank and specialised media outlets such as The PEW Charitable Trust.

The paper is structured as follows: The first section discusses the nature of the secondary ‘exploitation’ faced by tenants and the relation between such exploitation and broader labour exploitation. It also discusses the role of regulations, and therefore, state actors in boosting and linking different forms of exploitation. Focusing on the Spanish case, the second section explains the recent shifts from a mortgage-based to a rental payment based type of secondary exploitation. Moreover, it argues that secondary exploitation in rental tenancy is rooted in the need for banks to deleverage from real estate assets, using a Tres Cantos housing project in Madrid as a case example. The third section analyses how post-crisis regulations have forced banks to deleverage from housing assets while boosting their profits by allowing banks to issue mortgages to new landlords buying housing stock from the banks themselves. It argues that secondary exploitation suffered by tenants is also in the best interest of banks, as borrowers’ (landlords) risk decreases as the rents (and exploitation) from housing increases. The fourth section explores the relation between tenant and worker exploitation by tracing the monetary origins of Spanish rental housing investments and the relation between hedge and pension funds. It is claimed that in order for pension funds to accelerate their yields and therefore allow employers to continue employing and exploiting workers, pension funds are investing in companies that ultimately exploit tenants. It is further argued that the increasing reliance of pension funds in hedge funds, and therefore rental housing, is rooted in the quantitative easing policy of central banks. The fifth section concludes by claiming that the increasing relation between different types of exploitations is mediated by post-crisis regulations.

Linking Tenant ‘Exploitation’ with Labour Exploitation and the Neoliberal State

Exploitation and the Political Economy of Housing

Rental housing has become, in the post-crisis context, a ‘frontier’ for capital accumulation, and particularly for financial investors (Fernandez and Aalbers Citation2016, Fields Citation2018, Soederberg Citation2018, Wijburg et al. Citation2018). The absorption of capital in housing is, in Fernandez and Aalbers (Citation2016, p. 72) words, ‘one of the defining characteristics of the current age of financialization’. The literature on housing financialisation has focused on two main issues related to the post-crisis evolution of rental housing. On the one hand, fine-grained analyses of how financial corporations have acquired rental housing stock in cities such as Berlin, Madrid or New York have been provided (Teresa Citation2016, Fields Citation2018, Janoschka et al. Citation2019, Soederberg Citation2018). On the other hand, explanations about the rise in rental tenancy to the detriment of homeownership have also been made available (Kemp Citation2015, for example). Particularly insightful in the context of this paper is an article by Byrne (Citation2019), who claims that, in the context of crisis within the economies of Ireland, Spain and the United Kingdom, rental tenancy is increasing credit provision has diminished. It has also been pointed out how this decrease in available credit is related to the roll out of macroprudential regulations and ordoliberal ideology, which has greatly reduced the availability of banks to issue credit (Forrest and Hirayama Citation2015, Yrigoy Citation2019).

But despite the contraction of credit issuance for mortgage markets, a record amount of money is being invested in housing, resulting in the increasing dispossession and displacement of tenants (Purser Citation2016, Soederberg Citation2018, Espinoza and Plat Citation2019, Janoschka et al. Citation2019). In this particular context, Proudhon’s (quoted in Engels Citation1872) notorious statement ‘as the wage worker in relation to the capitalist, so is the tenant in relation to the house owner’ strongly correlates to what seems to be happening in the post-crisis rental housing market. Indeed, in order to theoretically and empirically grasp how it is possible that major investments are happening in post-crisis housing despite a reduction in mortgages, as well as understand the nature of the secondary ‘exploitation’ faced by tenants, two key interrelated issues must be taken into account: First, the different understandings of the concept of exploitation, and how the different forms of exploitation are increasingly related. Second, the role of state action (through regulations, policies and institutions) in articulating the relation between both types of exploitation.

Primary and Secondary Forms of Exploitation

Proudhon as well as the more Marxian-inclined literature on financialisation have illustrated how exploitation not only happens within the production process but also how it takes place as a large amount of households cannot afford an increase in rental prices and are displaced as a result (Fields Citation2015, Purser Citation2016, Soederberg Citation2018, Wijburg et al. Citation2018). Is this Proudhonian conceptualisation of ‘exploitation’ correct? From a Marxian theoretical point, Proudhon conceptualisation of tenant ‘exploitation’ is wrong: The working class needs to sell its ability to work – the labour force – to capitalists in exchange for a salary, and the very act of being forced to sell the ability to work is what, in Marxian thought, is considered exploitation (Harvey Citation1982). This process of selling the ability to work occurs not just in the production process but also in the civil sector (for example, individuals sell their ability to work as teachers, policemen, and so on). I refer to this form of exploitation as primary exploitation. Following Marxian reasoning, a tenant (or any other household inhabitant) cannot be exploited through the acquisition of housing, since the latter is a commodity bought – via sale or rental agreement – as with any other commodity. As Engels (Citation1872, p. 13) pointed out,

The tenant – even if he is a worker – appears as a man with money; he must already have sold his own particular commodity, his labour power, in order to appear with the proceeds as the buyer of the use of a dwelling.

However, as the next sections will illustrate, there is an increasing reliance on secondary exploitation in order to successfully carry out primary exploitation. The argument is as follows: pension benefits are a key component of an attractive job position, and thus, are an important element that predisposes labour to sell its ability to work to an employer, and thus to be exploited (Webber Citation2018). However, in the current post-crisis context, US public pension funds yields’ are decreasing, and thus pension funds have channelled their idle money (money coming from workers’ wages) into hedge funds, as the latter have the ability to find profitable niches in the current post-crisis scenario (Rajkumar and Dorfman Citation2010, McIntosh Citation2013, Elias et al. Citation2016, Webber Citation2018). Amongst other niches, hedge funds are investing pension funds’ money and providing returns to pension funds by buying rental housing and increasing rental prices (Fields Citation2018, Soederberg Citation2018). Rental housing therefore provide returns for pension funds both to secure pension benefits payments to their former workers; to keep the working conditions of the current workers, and to keep job positions attractive to workers by maintaining the pension benefit schemes.

In the case of those rental units owned by hedge funds, the very origin of land rentiers money invested in rental housing is ultimately the salaries labourers obtain as they sell their ability to work; as the money used by hedge funds comes predominately from hedge funds (Mcintosh Citation2013). Without a waged labour force being exploited, not only is value not produced but ultimately land rents are not extracted from rental housing either. Therefore, tenants living on hedge funds’ owned housing are exploited because of a previous exploitation of workers in broader economic processes.

The State’s Role in the Dialectical Relation between Exploitation(s)

The aforementioned relation between primary and secondary exploitation is enabled by the post-crisis regulations and monetary policies of state institutions. In other words, the progressive exploitation of tenants as rental housing has become financialised cannot possibly be grasped if state policies are not taken into account (Fernandez and Aalbers Citation2016, Waldron Citation2018). Indeed, pension funds are currently investing in rental housing stocks and not in other commodities because of a specific set of post-crisis economic policies which have actively pushed hedge funds and other institutional investors into the buy-to-let housing market (Fernandez and Aalbers Citation2016, Yrigoy Citation2019).

Note here how this post-crisis role of the state redefines the Marxian understanding of the state as an instrument of class domination (Harvey Citation1978). State regulations are developed in order to actually enforce exploitation in the production process (Harvey Citation1978). More recently, there have been debates about the power relations between state and corporate actors, with regulations redefined as ‘cognitive closure’, whereby corporate actors ‘seduce’ the state and therefore influence regulatory frameworks (Aalbers et al. Citation2011), or ‘regulatory capture’, when corporate actors infiltrate state power and therefore dictate regulations from within the state (Young Citation2012).

But what the post-crisis scenario vividly illustrates is how the state brings together primary and secondary exploitation. As the empirical sections will show, the monetary policy of central banks in the post-crisis scenario push pension funds to invest in hedge funds who locate these investments in rental housing. In the post-crisis context, workers’ wages have been channelled into pension funds, which, due to specific regulations, are massively investing in hedge funds, who also decide to invest in housing assets due to other specific regulations (Dixon and Monk Citation2014, Yrigoy Citation2019).

This dynamic illustrates that the state should not only be conceptualised as a structure which enforces the class power of dominant actors (Harvey Citation1978), but also as both a constitutive actor in wage-labour relations (Cartelier Citation1982) and, to no lesser a degree, a constitutive actor which links the exploitation occurring in different spheres of the economy. As the next section will show, in order to understand why rental tenancy has been targeted by post-crisis regulations, it is essential to recognise the failure of mortgage-based forms of secondary exploitation as the 2008 crisis exploded in Spain.

Secondary Exploitation in Spain: From Mortgage to Rentals

Crisis-ridden Shifts in Housing Tenancy and Secondary Exploitation in Spain

The relevance of rental tenancy is a new phenomenon in the Spanish context since homeownership has been promoted as the form of tenancy since the 1960s (García-Lamarca and Kaika Citation2016). At the time, around eight million Spaniards emigrated from rural to urban areas, and this population cohort was progressively politicised once they reached urban environments (López and Rodríguez Citation2010, pp. 271–309). Given such a context, promoting homeownership was a way to deactivate any potential contestation to the regime (Naredo Citation2004, López and Rodríguez Citation2010). Secondary exploitation via mortgage payments was reinforced in the 1980s through legislative changes which ended with the possibility of having indefinite rental agreements, thus furthering homeownership and contracting rental tenancy (López and Rodríguez Citation2010, Charnock et al. Citation2014).

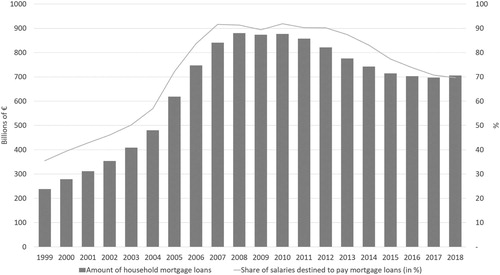

Secondary exploitation via mortgage payments was accelerated in the 1995–2007 period as larger amounts of household income became destined for mortgage-loan payments even though salaries decreased by ten per cent in that period; by 2006, 58.22 per cent of Spanish salaries were destined to pay off mortgage loans (Rodríguez and López Citation2010, p. 44, Colegio de Registradores Citation2018). Such an increase in the amount of household resources directed to pay mortgage loans went hand in hand with an expansion in the amount of mortgage debts held by households; whereas in 1999 Spanish households paid €238 billion for mortgage loans, by 2007 they paid €840 billion for mortgage loans (Bank of Spain Citation2018). This illustrates how secondary forms of exploitation occurred prior to 2008: By relentlessly increasing the share of salaries appropriated by rentiers.

However, mobilising such a large amount of household income towards mortgages was unsustainable in the long run: At some point, the appropriation of salaries by rentiers could not be further increased as a minimum share of salaries is imperiously required to cover other basic human needs. In fact, official data claims that up to 91.5 per cent of gross disposable income (available income after paying taxes) in Spanish households was being used in 2007 to pay mortgages and other debts (Bank of Spain Citation2018). To put it simply, household resources were simply not enough to cope with the ever-increasing rise in housing prices, and thus, Spanish households had difficulties in repaying loans. As a result, the share of non-performing loans increased in Spain from a record low of 0.7 per cent in 2006 to a maximum of 9.38 per cent in 2013 (Statista Citation2018).

Not surprisingly, the moment the secondary form of exploitation via expansion of mortgage markets could not be further increased was the moment the global financial crisis erupted. Without the ability to expand secondary exploitation through mortgage loans, the rate of homeownership started to (slightly) decrease in Spain – from a historical peak of 80.1 per cent of homeownership in 2007 to 76.7 per cent one decade later (INE Citation2018). At the same time, the amount of issued mortgage loans diminished as Spanish bank liquidity dried up (see ) (Charnock et al. Citation2014). As the possibility of exploitation via mortgage payments continues to disappear, rental tenancy has been increasingly regarded as a locus for secondary exploitation. Arguably the most prominent symptom of such an increasing role for rental payments as a central mechanism of secondary exploitation, is that for the first time in Spanish history there are currently more people being evicted from rental housing than from owned housing (CGPJ Citation2018). Indeed, by the end of 2018, those people evicted due to rent arrears represented 65.1 per cent of cases, whereas those evicted due to non-payment of mortgages represented 29.5 per cent of the total (CGPJ Citation2018).

Figure 1. Amount of household mortgage loans and share of household rents used to pay mortgage loans. Source: Bank of Spain Citation2018, Colegio de Registradores Citation2018.

Post-crisis, Rental-based Exploitation and the Banks’ Need to Deleverage: The Case of Fidere-Blackstone in Tres Cantos, Madrid

The positioning of rental housing as the main source of secondary exploitation has taken place as global financial corporations have massively acquired real estate portfolios across a variety of countries in the West such as the United States, United Kingdom, Ireland, Greece and, to no lesser extent, Spain (Alexandri and Janoschka Citation2018, Wijburg et al. Citation2018, Yrigoy Citation2018, Janoschka et al. Citation2019).

Between 2012 and 2018, €147 billion in non-performing loans (NPLs) backed by real estate assets, as well as real estate assets themselves, were acquired by hedge funds (Auraree Citation2018). Within the financial corporations acquiring housing assets, one company stands out: Blackstone. By 2018, Blackstone had acquired 100,000 rental housing units in Spain, becoming the largest landlord in the country (Arroyo Citation2018). The sellers of these assets were first and foremost Spanish banks in need of deleveraging from NPLs and/or real estate assets in order to cope with post-crisis financial regulations and pay off debts to its European lenders (Yrigoy Citation2018, Citation2019). Hedge funds have also obtained a large amount of NPLs from SAREB; a semi-public asset manager created in 2012 which acquired NPLs and real estate assets worth €51 billion belonging to the Spanish banks (Byrne Citation2015, Yrigoy Citation2018). There is, however, a third important niche in which hedge funds have secured large stocks of rental housing: The acquisition of social rental housing owned by real estate developers. Hedge funds target these projects because they are sold at bargain prices, as many of the owning companies were bankrupt real estate developers which had also been involved in large development projects remaining unsold on the housing market (López and Rodríguez Citation2010). Hedge funds are aware that social housing has controlled prices which last several years – between three and seven depending on the region – but after this period passes, landlords are able to either sell the house or increase the rental prices at their discretion.

What happens then once hedge funds have obtained rental housing? Technically, global financial corporations acquire and manage rental housing stock under real estate investment trust (from now on REIT) schemes. REITs are publicly listed companies whose main activities are the management of income-producing real estate assets such as rental housing (Waldron Citation2018, p. 209). The primary advantage of REITs vis-à-vis other investment vehicles in Spain is an exemption on corporate tax, an exemption on rented properties tax and an average 95 per cent discount on an average assets’ transference tax (Yrigoy Citation2018, p. 607). Moreover, in the Spanish context, REITs are meant to be an instrument particularly fitted to rental housing since REITs are subjected to the so-called 80/80/80 rule. That is, 80 per cent of an REIT’s revenues must come from rented real estate assets; 80 per cent of assets held on an REIT’s balance must be rented real estate assets and 80 percent of the income must be distributed to REIT’s shareholders (Fidere Citation2018). As a result of this state-enforced regulation, REITs have mushroomed all over the country, becoming the managers of hundreds of thousands of housing assets to be placed on the rental market.

The case of the housing project in Tres Cantos illustrates how the shifts in housing ownership have taken place and the consequences of these shifts for tenants. Madrid’s regional government and the city council of Tres Cantos decided in 2005 to develop a social housing project on a plot of land owned by FCC, one of the largest real estate developers in Spain (Azcárate Citation2018). In March 2007, a thousand newly finished houses were raffled to four thousand young adults under the age of 35 (Serrato Citation2018). Even though the project was promoted by the regional government of Madrid, the building, promotion and rental payments were carried out by FCC (Azcárate Citation2018). Social housing rental agreements in the Madrid region are signed for seven years with the option of purchasing the house once the agreement has ended (Azcárate Citation2018). In December 2013 FCC sold a thousand Tres Cantos social houses to Fidere, a REIT wholly owned by Blackstone. For five consecutive years after Fidere/Blackstone acquired this housing project the rents which could be extracted from these housing assets could not be increased as the project was considered social housing, and thus, the form of tenancy and rental prices could not be changed. Yet the classification of the Tres Cantos projects as social housing ended in December 2018. This means that as of January 2019 onwards, Fidere has been able to increase the rental prices or sell the housing units at its sees fit (Chiarroni Citation2018, Simón Ruiz Citation2019). Fidere has given the tenants three options: First, tenants have the option to continue the rental agreements with an ‘update’ on the prices. Average rental prices in the project will gradually increase from the current €560/month to €700/month in January 2019 and to €800/month by 2021. According to Fidere, however, the price increase will not reach free market prices, estimated to stand at €900/month (Chiarroni Citation2018). Second, Fidere provides the option of selling the houses for €180,000 each, the same dwellings which were bought by Fidere in 2013 for an average €72,000 (Chiarroni Citation2018). Last but not least, Fidere allows the tenants to leave the house once the contract ends in December 2018 (Fidere Citation2018). The Tres Cantos case of accelerated secondary exploitation is by no means unique; similar processes have actually taken place in several other housing projects across Spain.

How Spanish Banks Have Benefited through Post-crisis Regulations from Primary and Secondary Exploitation

Post-crisis Bank Regulations and the Role of REITs in Banking Deleverage

Why such urgency from banks to sell hundreds of thousands of housing assets to global financial corporations even if the rents (and therefore the exploitation of tenants) extracted from housing is increasing? The need of banks to deleverage, and the representation of these assets as highly devalued, is rooted in the introduction of post-crisis regulations, which blamed the economic crisis largely on banking systems (Ertürk Citation2015, Langley Citation2015). Indeed, one of the first consensuses reached after the 2008 economic meltdown was the need for tighter regulations on financial actors such as private banks in order to decrease its (failure) risk (Ertürk Citation2015, Langley Citation2015, Christophers Citation2016). This momentum for tighter regulation was crystallised in the Basel III and IFRS 9 agreements, through which the assets held on the banks’ balance sheets are weighted according to their default risk (Chorafas Citation2012, García Montalvo Citation2018).

Basel III is a regulatory framework concerning banks, agreed upon by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) in 2010, and it has been introduced by national regulators since then. The key principle of the agreement is that the assets a bank has on balance are classified according to its default risk. Each bank is obliged to reach a minimum threshold of high-quality assets and not surpass a maximum threshold of risky assets (Langley Citation2015, García Montalvo Citation2018). As Langley (Citation2015, p. 90) has explained, with Basel III

probabilistic calculations of the default risks of different asset classes were placed within risk-weighting categories. So, for instance, all government bonds held on the asset side of a bank’s balance sheet were given a zero percent risk-weighting, and corporate loans came with a 100 percent risk-weighting.

In principle, there is no way for banks to avoid such tight regulations: If banks do not accomplish the asset risk-weighting imposed through IFRS 9 and the BCBS, the possibilities of getting funded via the European Central Bank (ECB), the interbank loan market or other secondary markets is closed (Yrigoy Citation2018, Citation2019). But such regulatory control on banks and their involvement in housing markets was watered down with the emergence of REITs and the subsequent involvement of banks in the former. Interestingly enough, banks’ awarding of mortgage loans to REITs and acquiring REITs shares is not in contradiction with the IFRS 9 and Basel III regulatory frameworks as the main criteria in ascertaining the risk level of banks’ assets is to look at the chances of converting these assets into liquid money (Chorafas Citation2012). Even if REITs are holding on balance the same type of assets considered extremely risky when on the balance of banks, banks are not penalised for having shares in REITs or issuing mortgages to REITs (Chorafas Citation2012). This is because REIT-rooted assets, even if they are distressed housing assets, are ultimately backed by large pools of liquidity managed by global financial corporations such as Blackstone; thus, REITs are considered to be non-risky corporations.

Where do these hedge funds’ ‘pools of liquidity’ come from? Mainly from workers’ savings, which are invested into hedge funds via pension funds (McIntosh Citation2013, Agrawal and Lim Citation2020, The PEW Charitable Trust Citation2017). Note here how banks are benefiting from exploitation taking place in the production process: The larger the amount of wages placed into pension funds and subsequently placed into hedge funds, the more power hedge funds have to invest in REITs, and the more opportunities banks have to be involved in housing markets via issuing mortgages or purchasing minor shares in REITs (Cinco Días Citation2017). However, banks are not only taking advantage of the pension fund strategy to invest in hedge funds, they are also benefiting from the increasing secondary exploitation carried out by REITs in the Spanish housing rental market.

Secondary Exploitation as a Method of Boosting Bank Performance through REITs

By 2018, the estimated amount of mortgage lending from Spanish banks to REITs had escalated to €20 billion, with around 20 per cent of the real estate acquisitions carried out by Spanish REITs being funded by Spanish banks (Salces and Simón Citation2018, Valencia Plaza Citation2018). Furthermore, even if Spanish REITS are largely controlled by global financial corporations, Spanish banks also have minority stakes in these REITs (Cinco Días Citation2017, Casillas Citation2018). If SAREB is an instrument envisaged to encourage more deleveraging of toxic assets on the part of banks and thus cope with post-crisis global regulations (Yrigoy Citation2018), the roll out of REIT regulation in Spain has been conceived to create demand for the assets that banks have had to sell due to the implementation of Basel III. Indeed, only after REITs were established was the transference of distressed assets from banks to hedge funds made considerably easier (Alexandri and Janoschka Citation2018, Yrigoy Citation2018). Thus, it is in the banks’ own interest to award mortgages to REITs as it facilitates the transaction of distressed assets from banks to REITs. As stated above, whether REITs have acquired rental housing assets through banks, SAREB or heavily indebted developers (such as, for instance, FCC, the former owner of the Tres Cantos housing project), banks have been the primary beneficiaries of such transactions since they have been able to rid themselves of toxic assets and therefore conform to post-crisis regulations (Yrigoy Citation2018).

But the blossoming of REITs has a complementary advantage for banks in which secondary exploitation of tenants is of key relevance. Indeed, secondary exploitation leads to a low debt-to-income ratio for REITs, which ensures that REITs are able to maintain access to credit and thus allow banks not only to strengthen their credit issuance but also maintain and disguise their influence (and revenues) in regard to housing markets, bypassing global regulations hampering them from doing so (Yrigoy Citation2018, Citation2019). The case of Fidere (the REIT owning the abovementioned Tres Cantos project) can better illustrate the point: As Fidere increased the number of housing assets purchased via mortgage loans, its amount of debts increased from €80 million in 2014 to more than €467 million in 2018 (Fidere Citation2018). But despite the increase in Fidere’s debt, its debt ratios vis-à-vis income has rapidly decreased as mechanisms of secondary exploitation in spots such as Tres Cantos have been pushed forward: If in 2014 Fidere’s debt-income ratio was 18:1, the same ratio had decreased to 8:1 by 2017 (Fidere Citation2018). From the point of view of banks, it is critical to lend to companies which are not heavily indebted, as bank asset (such as issued credit) risk is weighted by post-crisis regulations, such as Basel III or IFRS 9, dependent on variables such as borrowers’ debt (Langley Citation2015). There is, therefore, a close relation between bank deleveraging and the issuance of credit for REITs: Not only have Spanish banks sold as many housing assets as they could to REITs as a way to clear their balance sheet, but at the same time they have awarded REITs the necessary mortgages to buy the distressed real estate assets sold by banks. Secondary exploitation in this context ensures that the mortgages banks award REITs are accepted as non-risky assets by post-crisis regulations.

In sum, global regulations have pushed banks to get rid of assets while national regulations regarding REITs have guaranteed the continuation of the link between banks and housing markets as banks are now, as before the crisis erupted, the main lenders to landlords.

From Hedge Funds to Pension Fund: Linking Primary and Secondary Exploitation

The Origins of the Money Underlying REITs and Hedge Funds: Linking Tenant and Worker Exploitation

Beyond substantially helping to improve bank balance sheets and thus invigorate mortgage markets (Fernandez and Aalbers Citation2016), REIT regulations allows pension funds and, no less so, hedge funds to reach rental housing, one of the few profitable investment niches available in a context of low interest rates (Byrne Citation2015, Fernandez and Aalbers Citation2016, Waldron Citation2018). As REITs help pension funds to reach rental housing, they are one key state-sponsored device which helps to link primary and secondary forms of exploitation.

In the case of Fidere, its ability to pay mortgage payments and dividends ultimately relies on Blackstone’s economic strength. Indeed, in 2018 Blackstone reached an agreement with a ‘foreign financial actor’ to inject into Fidere the necessary amount of money to pay back its mortgages, carry out refurbishments, and award Fidere’s shareholders a €120 million dividend (Ugalde Citation2018).

Who is the mysterious ‘foreign financial actor’ helping Fidere to pay mortgages and dividends? From where do hedge funds such as Blackstone acquire the money required to run REITs such as Fidere? Blackstone and similar global financial corporations usually create ad hoc fundraising vehicles in order to fund asset acquisition (see ) (Kaplan and Strömberg Citation2009). For instance, Fidere’s owner is Blackstone Real Estate Partners Europe IV L.P, a fundraising institution owned by Blackstone which raised $8.2 billion to invest in distressed real estate assets across Europe (Blackstone Citation2015). All the publicly known investors are US-based pension funds, such as Pennsylvania’s Public School Employees’ Retirement System (which invested $100 million in the fundraising vehicle), North Carolina’s Department of State Treasurer (which invested $150 million), the New York City Police Pension Fund and the Texas Permanent School Fund of the Texas Education Agency (with a $75 million investment) (Glodfelter Citation2013, Pennsylvania School Retirement System Citation2013, Texas Education Agency Citation2014, NYC Police Pension Fund Citation2018).

Not only is tenant exploitation in places such as Tres Cantos dependent, and therefore ‘secondary’ (In Engel’s jargon), on worker exploitation in the US economy, but the exploitation which policemen, firemen and teachers across the eastern and southern US coasts are facing is increasingly dependent on the exploitation of tenants in spots such as Tres Cantos. In this regard, good job conditions –which amongst other aspects, encompasses pension benefits-, are of paramount importance to maintain current workers and to recruit new workers into the public sector. It is therefore vital to maintain pension benefits to have workers willing to sell their ability to work to the public sector, and secondary exploitation of tenants has become one of the main ways by which pension funds obtain revenues, and thus can maintain their benefits for workers (Webber Citation2018).

Indeed, finding attractive yields for pension funds in the context of low – or even negative – interest rates is not an easy task (Sender Citation2018). Traditional investment niches, such as bonds or stocks, are decreasing, whereas alternative investments by hedge funds are increasing their yields (The PEW Charitable Trust Citation2017, Dizard Citation2019). In such a context, Hedge funds are the players who can obtain for pension funds the necessary yields which allow the later actors to keep paying benefits to workers and thus to maintain the mechanisms of primary exploitation.

The next section explains why pension funds find rental housing – and not other traditional investment niches (for pension funds) such as government bonds – particularly worth investing.

Quantitative Easing: The Monetary Policy that Links Primary and Secondary Exploitation

Pension funds have always channelled idle money into niches worth investing (Clark Citation2000). Yet the amount of liquid money amassed by all types of financial corporations (including pension funds) in the post-crisis years and its focus on real estate has happened at an unprecedented scale. Indeed, global financial corporations raised $453 billion in 2017, eclipsing the $414 billion raised in 2007 (Summerfield Citation2018). Investors have such a large amount of money available to invest because the anti-crisis policies of central banks in the European Union, United States, United Kingdom and Japan have focused on creating new money – so-called quantitative easing – which has ultimately trickled down to pension funds first and hedge funds after. This is why, nowadays, and despite the economic crisis, there is ‘too much cash chasing too few deals’ (Garret Citation2018).

Indeed, by means of the so-called quantitative easing policy, it is estimated that more than $12 trillion in new money has been created by central banks across the globe (Cox Citation2016). In the Eurozone alone, the ECB has created €2.6 trillion which has been spent buying up government debt, asset-backed securities and covered bonds (Carvalho et al. Citation2018). In the early stages of the economic crisis, governments issued bonds in order to deal with the crisis situation and bailout banks (Bank of Spain Citation2017). These bonds were sold at high interest rates – 7 per cent in the Spanish case – as governments badly needed extra sources of funding to carry out its own anti-crisis policies (Langley Citation2015, p. 43). At the same time, such high yields made government bonds an attractive asset worth investing in for pension funds, who massively acquired those bonds (Langley Citation2015).

But since 2015, quantitative easing policies have shifted in their approach, focusing instead on the acquisition by central banks of the government bonds held by pension funds, insurance companies and other holders, instead of acquiring mortgage-backed securities issued by banks (Claeys et al. Citation2016, Positive Money Citation2019). As a result, the yields of new bonds issued by governments sharply decreased (Positive Money Citation2019). As Hudson (Citation2012, p. 352) pointed out, ‘The federal reserve is flooding the banking system with so much liquidity that Treasury bills now yield less than 1 per cent’. As a result of this acquisition, the income of pension funds, and the workers benefiting from pension fund plans, has decreased together with the decline in government bond yields; thus, cities and/or states, which themselves have deficit problems, have increased their contributions to the pension funds (Dizard Citation2019). Moreover, government officials in the United States have been attempting to reduce pension benefits to workers in order to alleviate public budget contributions to public pension funds (Dizard Citation2019).

Unleashing quantitative easing means that pension funds have had an enormous amount of liquid money which must be invested somewhere in order to continue extracting rents. In a context whereby the budgets of public bodies are restrained and bonds have decreasing yields, real estate, and particularly housing, has emerged again as an asset worth investing in for pension funds. But how could pension funds or insurance companies possibly utilise real estate assets? It has been made possible primarily through the existence of hedge funds, which have fixed the idle money coming from pension funds into profitable assets such as rental housing (Invest Europe Citation2018). At the same time, as quantitative easing has reduced government bond yields, it has increased housing yields by fuelling a price increase (Jenkins Citation2018). As Jenkins (Citation2018) has argued,

The biggest inflationary driver [of housing prices] has been the programme of quantitative easing [which has] held back yields available on government bonds and other high-quality debt, pushing investors en masse into riskier asset classes. Real estate has been a natural focus.

Greater investment in equities and alternatives can provide higher financial returns but also bring heightened volatility and risk of shortfalls. The volatility inherent in public funds’ investment strategies can be seen in more recent results as well, with large funds posting fiscal year gains of over 12 percent in 2013 and 17 percent in 2014, but only 2 percent in 2012, 4 percent in 2015, and 1 percent in 2016.

Such a quantitative easing policy cannot last forever as there is a high risk of inflation (Claeys et al. Citation2016, Rogoff Citation2017). In fact, the risk of inflation has for the moment been restrained due to the low interest rate policy which has gone hand in hand with quantitative easing policies (Sibbert Citation2010, Claeys et al. Citation2016). But two important limits appear here: First, inflation can hardly be controlled even if interest rates are at a record low (Claeys et al. Citation2016). Second, increases in rental prices cannot be increased indefinitely; so far, rental increases have multiplied evictions in rental tenancy and the average salary amount destined to pay housing rentals among Spanish families is 42.1 per cent, which is well above the EU average of 26.1 per cent (CGPJ Citation2018, Eurostat Citation2019). If this rise continues to increase, it will soon reach the same threshold of salaries used before the crisis to pay mortgages loans, thresholds which proved to be unbearable for households and therefore for the whole economy. Hedge funds are fully aware of such limits and ready to keep profiting once rental payments cannot be further increased. Blackstone is very clear that once the rents in rental housing cannot be increased anymore it will aim to sell its housing stock in Spain to other landlords, as it has done in the United States and the United Kingdom (Wijburg et al. Citation2018, Williams Citation2018, Simón Ruiz Citation2019).

In the Spanish context, it will be difficult to sell housing to local stakeholders if the mortgage market is not revitalised, something which cannot be done as long as interest rates are not increased. But, in the event that interest rates increase, a policy of quantitative easing will have to stop otherwise inflation will sky-rocket. A double movement regarding monetary policy will therefore be needed in the years to come: As the massive creation of money has the risk of ending up in an inflationist turmoil, a quantitative ‘tightening’ of the money issued by central banks will increasingly be required. Yet for the time being Blackstone and similar funds have increased their investments in the Spanish rental housing market – global financial corporations invested a historical record of €62 billion into Spanish housing acquisition in 2018 – and have kept increasing rental-based secondary exploitation, gaining as much in rents as possible while the quantitative easing policies stand.

Concluding Remarks

The article has shown how Engels (Citation1872) claim that household ‘exploitation’ is ‘secondary’ to the exploitation taking place in production must be reconsidered in light of Spain’s recent rental market patterns. Secondary ‘exploitation’ of households has become more and more relevant in boosting pension fund income and thus helps to boost workers’ exploitation. In fact, it could be the case that individuals are facing an increase in rental prices caused by the acquisition of their dwelling by an REIT ultimately backed by money from their own pension fund. The very same person would be facing shifting returns from the pension fund because their landlord is increasing the rental prices. Technically, a tenant may face displacement because of the exploitation he/she is suffering as a worker; this is the dialectical relation between primary and secondary exploitation.

Such an increasing relation between primary and secondary exploitation is taking place because of the monetary policies carried out both by the US Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank. Indeed, Quantitative easing is the state regulation which ultimately encompasses the rhythms of primary and secondary exploitation. Not only do regulations coordinate the rhythms of exploitation in the workplace and the household but there is also a dialectical relation and continuity in the regulations aiming to restructure the role of housing in the post-crisis economy and the different forms of exploitation suffered by households (see ). First, banking regulations such as Basel III aimed to deleverage banks from housing assets. As banks deleveraged, REITs were created in Spain. As hedge funds landed in the country, there has been increased pressure on tenants, exemplified in this article through the case of Tres Cantos. This is possible because quantitative easing policies have placed the idle money of institutional investors into pension funds instead of other traditional niches such as bonds or stocks (Agrawal and Lim 2017, The PEW Charitable Trusts Citation2017). Such a regulatory roll out shows not only the state role in ensuring the interests of what Harvey (Citation1978) labelled the ‘dominant class’, but it also illustrates the coordinative role of the state in directing the mechanisms of worker and tenant exploitation taking place.

Table 1. Post-crisis regulations and its impacts on exploitation.

What will be the next step once quantitative easing ends (due to the risk of inflation)? In the Spanish case, the reliance of hedge funds on rental-based secondary exploitation may change once quantitative tightening is fully implemented (JLL Citation2019). Still, as the flow of quantitative money eventually stops, the strategies of global financial corporations may possibly shift. Their short-term strategies may yet be to further toughen the mechanisms of rental-based secondary exploitation. The acquisitions of rental housing by these corporations and subsequent processes of eviction and displacement may keep increasing for a few years. But ultimately, once mortgage markets have recovered, hedge funds such as Blackstone will likely be willing to increase its extraction of rents via housing sales. In order to sell houses, hedge funds will have to first empty their housing stock via massive rental increases leading to evictions. This is the difficult balance these corporations are playing as of 2019: On the one hand, the need to maintain the rent stream from housing rentals so as to keep enlarging their housing portfolios, and on the other, the need to empty these housing units so they can be rapidly be sold when the moment comes.

Acknowledgement

I would like to thank very much Brett Christophers, Peter Jakobsen and two anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments on earlier drafts of the paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes on contributor

Ismael Yrigoy hold a Phd in Geography from the University of the Balearic Islands (2015). Ismael Yrigoy currently working as a postdoctoral researcher at the Department of Social and Economic Geography at Uppsala University and at the Department of Geography at University of Santiago de Compostela.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aalbers, M., 2012. Subprime cities. The political economy of mortgage markets. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Aalbers, M., 2019. Financial geography II: financial geographies of housing and real estate. Progress in human geography, 43 (2), 376–87. doi: 10.1177/0309132518819503

- Aalbers, M. and Christophers, B., 2014. Centring housing in political economy. Housing, theory and society, 31 (4), 373–94. doi: 10.1080/14036096.2014.947082

- Aalbers, M., Engelen, E., and Glasmacher, A., 2011. ‘Cognitive closure’ in the Netherlands: mortgage securitization in a hyrbid European political economy. Environment and planning A: economy and space, 43 (8), 1779–95. doi: 10.1068/a43321

- Agrawal, A. and Lim, Y., 2018. The dark side of hedge fund activism: evidence from employee pension plans (September 29, 2017). 29th annual conference on financial economics & accounting 2018. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3000596 [Accessed 19 September 2019].

- Agrawal, A. and Lim, Y., 2020. Where do shareholder gains in hedge fund activism come from? Evidence from employee pension plans. Available from: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3000596 [Accessed 1 February 2020].

- Alexandri, G. and Janoschka, M., 2018. Who loses and who wins in a housing crisis? Lessons from Spain and Greece for a nuanced understanding of dispossession. Housing policy debate, 28 (1), 117–34. doi: 10.1080/10511482.2017.1324891

- Arroyo, R., 4 September 2018. Blackstone crea un gigante inmobiliario de 20.000 millones en España. Available from: https://www.expansion.com/empresas/inmobiliario/2018/09/03/5b8d5fbee2704e0a9a8b4623.html [Accessed 16 September 2019].

- Auraree, 2018. Portfolio transactions- Spain. Aura Real Estate Database.

- Azcárate, A., 11 August 2018. Fidere: el fondo buitre que especula con viviendas de protección general. Available from: https://www.elsaltodiario.com/fondos-buitre/fidere-el-fondo-buitre-que-pretende-obtener-el-150-de-rentabilidad-sobre-viviendas-de-proteccion-oficial [Accessed 10 December 2018].

- Bank of Spain, 2017. Report on the financial and banking crisis in Spain, 2008–2014. Available from: https://www.bde.es/f/webbde/Secciones/Publicaciones/OtrasPublicaciones/Fich/InformeCrisis_Completo_web_en.pdf [Accessed 30 April 2019].

- Bank of Spain, 2018. Statistical bulletin. Hoseuholds and non-profit institutions serving households. Available from: https://www.bde.es/webbde/en/estadis/infoest/bolest16.html [Accessed 6 December 2018].

- Bholat, D., et al., 2017. Non-performing loans at the dawn of IFRS 9: regulatory and accounting treatment of asset quality. Journal of banking regulation, 19 (1), 33–54. doi: 10.1057/s41261-017-0058-8

- Blackstone, 2015. Blackstone has $15.8 billion final close for latest global real estate fund. Available from: https://www.blackstone.com/press-releases/blackstone-has-$15.8-billion-final-close-for-latest-global-real-estate-fund [Accessed 29 November 2019].

- Brav, A., Jiang, W., and Kim, H., 2009. Hedge fund activism: a review. Foundations and trends in finance, 4 (3), 185–246. doi: 10.1561/0500000026

- Byrne, M., 2015. Bad banks: the urban implications of asset management companies. Journal of urban research and practice, 8 (2), 255–66.

- Byrne, M., 2019. Generation rent and the financialization of housing: a comparative exploration of the growth of the private rental sector in Ireland, the UK and Spain. Housing studies. doi:10.1080/02673037.2019.1632813.

- Cartelier, L., 1982. The state and wage labour. Capital & class, 6 (3), 39–55. doi: 10.1177/030981688201800103

- Carvalho, R., Ranasinghe, D., and Wilkes, T., 2018. The life and times of ECB quantitative easing, 2015–18. Available from: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-eurozone-ecb-qe/the-life-and-times-of-ecb-quantitative-easing-2015-18-idUSKBN1OB1SM [Accessed 12 December 2018].

- Casillas, C., 2018. Las Socimis seducen a la banca privada. Available from: https://www.abc.es/economia/abci-socimis-seducen-banca-privada-201801300149_noticia.html [Accessed 01 February 2020].

- CGPJ, 2018. Los lanzamientos derivados del impago de alquiler aumentan un 7,9% por ciento en el tercer trimestre de 2018. Available from: http://www.poderjudicial.es/cgpj/es/Poder-Judicial/Consejo-General-del-Poder-Judicial/En-Portada/Los-lanzamientos-derivados-del-impago-de-alquiler-aumentan-un-7-9-por-ciento-en-el-tercer-trimestre-de-2018 [Accessed 10 December 2018].

- Charnock, G., Purcell, T., and Ribera-Fumaz, R., 2014. The limits to capital in Spain. Crisis and revolt in the European South. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Chiarroni, C., 26 September 2018. El ‘desahucio silencioso’ de las 1000 viviendas de Tres Cantos: “nos están echando”. Available from: https://www.20minutos.es/noticia/3449771/0/desahucio-mil-viviendas-tres-cantos/ [Accessed 11 December 2018].

- Chorafas, D., 2012. Basel III, the devil and global banking. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Christophers, B., 2016. Geographies of finance III: regulation and ‘after-crisis’ financial futures. Progress in human geography, 40 (1), 138–48. doi: 10.1177/0309132514564046

- Cinco Días, 5 April 2017. Merlin: el reto de gestionar el apalancamiento y mejorar la rentabilidad. Available from: https://cincodias.elpais.com/cincodias/2017/04/05/companias/1491389722_775328.html [Accessed 10 January 2019].

- Claeys, G., Leandro, A., and Mandra, A., 2016. European central bank quantitative easing: the detailed manual. Available from: https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/126687/1/823793087.pdf [Accessed 22 January 2019].

- Clark, G., 2000. Pension fund capitalism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Colegio de Registradores, 2018. Estadística registral immobiliaria. Available from: http://www.registradores.org/portal-estadistico-registral/estadisticas-de-propiedad/estadistica-registral-inmobiliaria/ [Accessed 18 September 2019].

- Cox, J., 13 June 2016. $12 trillion of QE and the lowest rates in 5000 years … for this? Available from: https://www.cnbc.com/2016/06/13/12-trillion-of-qe-and-the-lowest-rates-in-5000-years-for-this.html [Accessed 18 January 2019].

- Dixon, A.D. and Monk, A.H.B., 2014. Frontier finance. Annals of the association of American geographers, 104 (4), 852–68. doi: 10.1080/00045608.2014.912543

- Dizard, J., 6 September 2019. Chicago’s deficit heralds US pensions crisis. Available from: https://www.ft.com/content/1d3fd827-9372-3618-bac7-daf2d96932c1 [Accessed 6 September 2019].

- Elias, J., Goetzman, W., and Baskin, L., 2016. The role of hedge funds in institutional portfolios: Florida retirement system. New Haven: Yale School of Management.

- Engels, F., 1872. The housing question. London: Publishing Society of Foreign Workers.

- Ertürk, I., 2015. Financialization, bank business models and the limits of post-crisis bank regulation. Journal of banking regulation, 17 (1–2), 60–72. doi: 10.1057/jbr.2015.23

- Espinoza, J. and Platt, E., 27 June 2019. Private equity races to spend record $2.5tn cash pile. Available from: https://www.ft.com/content/2f777656-9854-11e9-9573-ee5cbb98ed36 [Accessed 17 September 2019].

- Eurostat, 2019. Housing cost overburden rate by tenure status. EU-SILC survey. Available from: http://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/submitViewTableAction.do [Accessed 23 January 2019].

- Fernandez, R. and Aalbers, M.B., 2016. Financialization and housing: between globalization and varieties of capitalism. Competition & change, 20 (2), 71–88. doi: 10.1177/1024529415623916

- Fidere, 2018. Tres Cantos: Preguntas y respuestas respecto final de protección. Available from: https://las1000delnuevotrescantos.files.wordpress.com/2017/11/131117_fidere-questionario-tres-cantos-completo.pdf [Accessed 17 December 2018].

- Fields, D., 2015. Contesting the financialization of urban space: community organizations ad the struggle to preserve affordable rental housing in New York City. Journal of urban affairs, 37 (2), 144–65. doi: 10.1111/juaf.12098

- Fields, D., 2018. Constructing a new asset class: property-led financial accumulation after the crisis. Economic geography, 94 (2), 118–40. doi: 10.1080/00130095.2017.1397492

- Fields, D. and Uffer, S., 2016. The financialisation of rental housing: a comparative analysis of New York city and Berlin. Urban studies, 53 (7), 1486–502. doi: 10.1177/0042098014543704

- Forrest, R. and Hirayama, Y., 2015. The financialization of the social project: embedded liberalism, neoliberalism and homeownership. Urban studies, 52 (2), 233–44. doi: 10.1177/0042098014528394

- García-Lamarca, M. and Kaika, M., 2016. ‘Mortgaged lives’: the biopolitics of debt and housing financialisation. Transactions of the institute of British geographers, 41 (3), 313–27. doi: 10.1111/tran.12126

- García Montalvo, J., 2018. Nuevas coberturas y normas contables: efectos sobre los activos problemáticos de la banca española. Cuadernos de Información económica (264), 25–35.

- Garret, J.B., 15 March 2018. The trillion-dollar question: what does record dry powder mean for PE & VC fund managers? Available from: https://pitchbook.com/news/articles/the-trillion-dollar-question-what-does-record-dry-powder-mean-for-pe-vc-fund-managers [Accessed 21 December 2018].

- Glodfelter, R., 17 December 2013. North Carolina commits $342 m to noncore real estate. Available from: https://irei.com/news/north-carolina-commits-342m-to-noncore-real-estate/ [Accessed 23 January 2019].

- Harvey, D., 1978. The Marxian theory of the state. Antipode, 8 (2), 80–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8330.1976.tb00641.x

- Harvey, D., 1982. The limits to capital. London: Verso books.

- Hudson, M., 2012. The bubble and beyond. Fictitious capital, debt deflation and the global crisis. Dresden: Islet-Verdag.

- INE, 2018. Households, by tenancy regime of the dwelling and type of household. Available from: http://www.ine.es/jaxiT3/Tabla.htm?t=4555&L=1 [Accessed 6 December 2018].

- Invest Europe, 2018. 2017 private equity activity. Statistics on Fundraising, Investments and Disinvestment. Available from: https://www.investeurope.eu/media/711867/invest-europe-2017-european-private-equity-activity.pdf [Accessed 22 January 2019].

- Janoschka, M., et al., 2019. Tracing the socio-spatial logics of transnationaal landlords’ real estate investment: Blackstone in Madrid. European urban and regional studies. doi:10.1177/0969776418822061.

- Jenkins, P., 13 April 2018. High housing prices signal a danger of reckoning to come. Available from: https://www.ft.com/content/6174a1f4-208e-11e8-8d6c-a1920d9e946f [Accessed 14 January 2019].

- JLL, 21 June 2019. Record dry powder, fund managers continue to raise capital. Available from: https://www.us.jll.com/en/trends-and-insights/investor/record-dry-powder-fund-managers-continue-to-raising-capital [Accessed 23 September 2019].

- Kaplan, S.N. and Strömberg, P., 2009. Leveraged buyouts and private equity. Journal of economic perspectives, 23 (1), 121–46. doi: 10.1257/jep.23.1.121

- Kemp, P.A., 2015. Private renting after the global financial crisis. Housing studies, 30 (4), 601–20. doi: 10.1080/02673037.2015.1027671

- Langley, P., 2015. Liquidity lost. The governance of the global financial crisis. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- López, I. and Rodríguez, E., 2010. Fin de ciclo: financiarización, territorio y sociedad de propietarios en la onda larga del capitalismo hispano, 1959–2010. Madrid: Traficantes de Sueños.

- McIntosh, B., 2013. Pension fund investors: how hedge funds are adapting to attract allocations. Available from: https://thehedgefundjournal.com/pension-fund-investors/ [Accessed 20 November 2019].

- Naredo, J.M., 2004. Perspectivas de la vivienda. Información Comercial Española, 815, 143–54.

- Novotny-Farkas, 2016. The interaction of the IFRS 9 expected loss approach with supervisoty rules and the implications for financial stability. Accounting in Europe, 13 (2), 197–227. doi: 10.1080/17449480.2016.1210180

- NYC Police Pension Fund, 2018. Monthly performance review, January 2018. Available from: https://comptroller.nyc.gov/wp-content/uploads/documents/Monthly-Performance-Review_03-2018-POLICE.pdf [Accessed 23 January 2019].

- Pahl, R.E., 1975. Whose ciry? And other essays on sociology and planning. London: Longman.

- Pennsylvania School Retirement System, 2013. Opportunistic real estate fund commitment. Available from: https://www.psers.pa.gov/About/Board/Resolutions/Documents/2013/res51_tab9.pdf [Accessed 23 January 2019].

- The PEW Charitable Trusts, 2017. State public pension funds increase use of complex investments. Available from: https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/reports/2017/04/state-public-pension-funds-increase-use-of-complex-investments [Accessed 23 September 2019].

- Positive Money, 2019. How quantitative easing works. Available from: https://positivemoney.org/how-money-works/advanced/how-quantitative-easing-works/ [Accessed 11 January 2019].

- Purser, G., 2016. The circle of dispossession: evicting the urban poor in Baltimore. Critical sociology, 42 (3), 393–415. doi: 10.1177/0896920514524606

- Rajkumar, S. and Dorfman, M.C., 2010. Governance and investment of public pension assets. Washington, DC: The World Bank. Available from: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/856261468175789789/pdf/613130PUB00Pub18344B009780821384701.pdf [Accessed 20 November 2019].

- Rodríguez, E. and López, I., 2010. Fin de ciclo. Financiarización, territorio y sociedad de propietarios en la onda larga del capitalismo hispano (1959–2010) [End of cycle. Financialization, land and homeownership society in the long wave of Hispanic capitalism (1959–2010)]. Madrid: Traficantes de sueños.

- Rogoff, K., 2017. Dealing with monetary paralysis at the zero bound. Journal of economic perspectives, 31 (3), 47–66. doi: 10.1257/jep.31.3.47

- Salces, L. and Simón, A., 19 September 2018. Los expertos alertan de fuga de inversiones si se modifica el régimen de las Socimis. Available from: https://cincodias.elpais.com/cincodias/2018/09/18/mercados/1537292363_414725.html [Accessed 10 January 2019].

- Sender, H., 2 March 2018. Blackstone chief’s 2017 payout shows health of private equity. Available from: https://www.ft.com/content/4ee00662-1dcf-11e8-956a-43db76e69936 [Accessed 21 December 2018].

- Serrato, F., 27 August 2018. Mil familias contra un fondo de inversión. Los vecinos de 14 bloques de Tres Cantos denuncian los precios abusivos que Fidere pone a sus viviendas protegidas. Available from: https://elpais.com/ccaa/2018/08/25/madrid/1535220469_241839.html [Accessed 10 December 2018].

- Sibbert, A., 2010. Quantitative easing and Currency wars. Directorate general for internal policies. Economic and Monetary affairs. European Parliament. Available from: http://eprints.bbk.ac.uk/9647/1/quantitive%20easing%20and%20currency%20wars.pdf [Accessed 22 January 2019].

- Simón Ruiz, A., 24 April 2019. Blackstone abre la Puerta a la venta de pisos sociales comprados en Madrid. Available from: https://cincodias.elpais.com/cincodias/2019/04/23/companias/1556045344_333951.html [Accessed 30 April 2019].

- Soederberg, S., 2018. The rental housing question: exploitation, eviction and erasures. Geoforum, 89, 114–23. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2017.01.007

- Statista, 2018. Bank non-performing loans (NPL) to gross loans ratio in Spain from 2005 to 2017. Available from: https://www.statista.com/statistics/460913/non-performing-bank-loans-in-spain/ [Accessed 6 December 2018].

- Summerfield, R., 2018. PE sets fundraising record in 2017. Available from: https://www.financierworldwide.com/pe-sets-fundraising-record-in-2017/#.XBDbK9tKjmF [Accessed 12 December 2018].

- Teresa, B., 2016. Managing fictitious capital: the legal geography of investment and political struggle in rental housing in New York city. Environment and planning A: economy and space, 48 (3), 465–84. doi: 10.1177/0308518X15598322

- Texas Education Agency, 2014. July 2014 committee on school finance permanent school fund item 9. Available from: https://tea.texas.gov/About_TEA/Leadership/State_Board_of_Education/2014/July/July_2014_Committee_on_School_Finance_Permanent_School_Fund_Item_9/ [Accessed 23 January 2019].

- Ugalde, R., 23 April 2018. Blackstone endeuda a Fidere con 543 millones para un dividendo millonario. Available from: https://www.elconfidencial.com/empresas/2018-04-23/blackstone-refinancia-543m-fidere-dividendo-millonario_1552971/ [Accessed 13 December 2018].

- Valencia Plaza, 7 November 2018. Las socimis no son un riesgo para la banca española por su “limitada” exposición. Available from: https://valenciaplaza.com/las-socimis-no-son-un-riesgo-para-la-banca-espanola-por-su-limitada-exposicion [Accessed 10 January 2019].

- Waldron, R., 2018. Capitalizing on the state: the political economy of real estate investment trusts and the ‘resolution’ of the crisis. Geoforum, 90, 206–18. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2018.02.014

- Webber, D., 2018. The rise of the working-class shareholder: labor’s last best weapon. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Wijburg, F., Aalbers, M., and Heeg, S., 2018. The financialisation of rental housing 2.0: releasing housingo into the privatised mainstream of capital accumulation. Antipode, 50 (4), 1098–119. doi: 10.1111/anti.12382

- Williams, A., 11 May 2018. Blackstone under fire over push into UK social housing. Available from: https://www.ft.com/content/6a68b7c8-4ec9-11e8-9471-a083af05aea7 [Accessed 23 January 2019].

- Young, K., 2012. Transnational regulatory capture? An empirical examination of the transnational lobbying of the Basel committee on banking supervision. Review of international political economy, 19 (4), 663–88. doi: 10.1080/09692290.2011.624976

- Yrigoy, I., 2018. State-led financial regulation and representations of spatial fixity: the example of the Spanish real estate sector. International journal of urban and regional research, 42 (4), 594–611. doi: 10.1111/1468-2427.12650

- Yrigoy, I., 2019. The role of regulations in the Spanish housing dispossession crisis: towards dispossession by regulations? Antipode. doi:10.1002/anti.12577.