?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Corporations increasingly engage in innovative ‘tax planning strategies’ by shifting profits between jurisdictions. In response, states try to curtail such profit shifting activities while at the same time attempting to retain and attract multinational corporations. We aim to open up this dichotomy between states and corporations and argue that a wealth defence industry of professional service firms plays a crucial role as facilitators. We investigate the subsidiary structure of 27,000 MNCs and show that clients of the Big Four accountancy firms show systematically higher levels of aggressive tax planning strategies than clients of smaller accountancy firms. We specify this effect for three distinct strategies and also uncover marked differences across countries. As such we provide empirical evidence for the systematic involvement of auditors as facilitators in corporate wealth defence.

Introduction

The growth of financial markets, ongoing financialization, and increasing financial fluidity enables corporations to shift profits, assets and costs from one region to another (Clausing Citation2016, Seabrooke and Wigan Citation2017, Tørsløv et al. Citation2018). This gives multinational corporations (MNCs) an advantage over states, and triggers tax competition among those states eager to retain and attract MNCs (Genschel, Kemmerling and Seils Citation2011). The consequences of this dynamic are difficult to ignore: the amount of profits shifted to low tax countries is 600–1100 billion US$ every year according to some of the latest studies (See e.g. Clausing Citation2016, OECD Citation2015, Janský and Palanský Citation2017, Tørsløv et al. Citation2018). The tax losses for states due to corporate profit shifting activities are increasingly seen as problematic as they lead to diminishing state capacities and to a distortion of fair competition mechanisms, as claimed by the European Commission (Citation2015, Citation2016) and the OECD (Citation2015).

The growing literature on tax avoidance has had a keen eye for both innovative corporate ‘tax planning’ strategies (Lanz and Miroudot Citation2011, DeBacker et al. Citation2015, Wagener and Watrin Citation2014, Beer and Loeprick Citation2015) as well as for the regulatory role of states to counteract such strategies or mitigate its effects (Palan Citation1998, Genschel and Schwarz Citation2011, Rixen Citation2013, Haberly and Wójcik Citation2015, Genschel and Seelkopf Citation2016, Jones and Temouri Citation2016). But this is not the complete picture. There is a third key player in this game of tax avoidance and competition. We call this the wealth defence industry, formed by the professional service firms that provide tax services and the technical knowledge which companies need to develop their profit allocation strategies. According to the UK House of Commons the provision of tax services to companies and wealthy individuals forms an industry, ‘worth almost £2 billion each year in the UK, and £25 billion globally’ (Citation2013, p. 7). And while ‘some tax advice results in transactions or restructuring that are undertaken for commercial reasons and are neutral, much of the advice is aimed at minimising the tax that wealthy individuals or corporations pay’ (UK House of Commons Citation2013).

Suppliers of wealth defence services need to be able to trace legislative changes across countries, design and promote legal, accounting and financial vehicles to overcome national boundaries by carefully placing assets and liabilities in specific jurisdictions (Suddaby et al. Citation2007, Wójcik Citation2013). Accountancy firms stand out in the wealth defence industry as they are able to deliver on these requirements. Since the 1980s, the field of accountancy has undergone profound changes (Sikka and Willmott Citation1995, Teck-Heang and Ali Citation2008). Traditionally, the core business of accountancy firms was to provide financial accounting and auditing, thereby disclosing reliable information to investors, and contributing to financial stability (Arnold Citation2009). As a response to commercial pressures however, accountancy firms developed into lucrative business opportunities, expanding in particular towards consulting and tax services. With this reorientation, the profession changed from a predominantly domestic, relatively neutral expert guild into a high-fee-earning, multifaceted broker in the global economy.

A series of mergers amongst the largest firms led to a high market concentration with the so-called Big Four accountancy firms dominating the market today. In addition to their advantage in terms of size, Deloitte, PricewaterhouseCoopers, E&Y and KPMG are multi-jurisdictional and cross-disciplinary, bringing together accounting, law, tax and supply chain management (see also Strange Citation1996). Several authors attribute a proactive role to accountancy firms in profit shifting (Strange Citation1996, Sikka and Mitchell Citation2011, Sikka and Willmott Citation2013). PwC, for example, developed innovative tax schemes for a multinational in the beverage sector, SABMiller, which led to large tax losses in several African countries (Sikka and Willmott Citation2013). Recently, the Paradise Papers leaked confidential documents which showed how Deloitte and PwC provided tax advice for their client Blackstone, a private equity group. They carefully outlined each step that Blackstone should follow to minimise various types of tax liabilities in multiple countries (www.icij.org). After these revelations, the Council of the European Union urged tax planners to provide more transparency about their activities (Citation2018).

We respond to the growing call for more insight into the role of suppliers in tax innovation by introducing the wealth defence industry as a key player and ask a simple yet pertinent question: how and to what extent do accountancy firms influence the wealth defence strategies of their corporate clients? Our investigation is informed by previous insights on this matter, gained mainly through journalistic investigations, leaks and in-depth case studies. Our objective is to provide a systematic analysis across a large number of firms and jurisdictions.

We are particularly interested in how firms use their subsidiary network as tools for their wealth defence. Jones et al. (Citation2018) give an excellent example of work that establishes a systematic understanding of the extent to which accountancy firms are involved in the wealth defence business. Investigating 6,000 multinational companies, they showed that clients of the Big Four have a higher presence in offshore jurisdictions than other companies. We build on this research approach and conduct a large-scale analysis of subsidiary structure-related tax planning strategies for about 27,000 multinationals and ask how these strategies are related to the auditors of the companies. By applying mixed multivariate regression models, we are able to differentiate between the influence of the Big Four auditors and the influence of other firm level and country level variables. In particular we study how Big Four presence at MNCs relate to three types of strategies that reflect the tax aggressiveness of corporations: those aimed at utilising the benefits of Offshore Financial Centres (OFC); those aimed at using particular corporate forms (holding or management entities) to reduce tax burdens; and those that use particular complex corporate ownership structures to increase the coordination efforts of tax authorities.

As one of the first large scale empirical investigations into the wealth defence industry, our work is necessarily of an exploratory nature. We offer a novel analysis on tax planning strategies by multinational corporations using the largest dataset available today; we add to previous work by taking into account the multidimensionality of wealth defence and therefore consider not one but three tax planning strategies; we expand previous work on the use of offshore financial centres by MNCs by considering the role of both sink and conduit OFCs (Garcia-Bernardo et al. Citation2017); and finally we are able to show how the influence of accountancy firms on corporate wealth defence structures varies across countries. We find that being audited by the Big Four accountancy firms indeed increases the use of OFC subsidiaries as well as holding and management subsidiaries for firms with a large international exposure, and that clients of the Big Four have a higher subsidiary network complexity if measured in terms of depth and entropy. Our findings underscore the important role of the wealth defence in the fundamental political economic struggle between states and corporations.

The remainder is structured as follows: First, we introduce the concept of the wealth defence industry. Second, we zoom in on the historic context for accountancy firms as key players in this wealth defence industry. This allows us to develop propositions on the role of accountancy firms for aggressive tax planning strategies of MNCs. Subsequently, we introduce our research design and dataset, followed by the empirical results regarding auditor involvement in wealth defence strategies. Finally, we discuss the insights gained through this study as well as the limitations we still face.

A Wealth Defence Industry in Global Wealth Chains

Internationally active MNCs challenge the boundaries of national regulatory structures. The monopoly of states in defining market relations are challenged by professional groups (Suddaby et al. Citation2007). In the field of tax avoidance, we call these professionals ‘the wealth defence industry’: legal, consulting and accountancy firms, characterised by their capacity to supply knowledge and expertise to corporations regarding aggressive tax planning strategies, while mitigating regulatory threats from governments. The emerging Global Wealth Chains literature is instructive in this matter since it helps to better understand the decoupling of physical and financial production, which is key for tax optimisation.

Drawing the parallel to the Global Value Chains theory (Gereffi et al. Citation2005), Seabrooke and Wigan (Citation2017, p. 2) suggest studying Global Wealth Chains (GWC), which can be defined as ‘transacted forms of capital operating multi-jurisdictionally for the purposes of wealth creation and protection’. MNCs manage wealth across multiple countries, whereby they separate financial production, such as the response to fiscal claims, legal obligations, or regulatory oversight, from physical production, such as the manufacturing and management of services and goods. This is possible because fiscal rules are territorially fixed while capital flows have a high mobility. Although the definition is left ambiguous by the authors, ‘wealth’, in this perspective, refers to intra-company resources such as profits or assets, and therefore contrasts the common conceptions of wealth as an individual resource. Importantly, ‘wealth chains hide, obscure and relocate wealth to the extent that they break loose from the location of value creation and heighten inequality’ (Seabrooke and Wigan Citation2014, p. 257). They lead to a process of legal and financial disaggregation of activities within corporations.

Understanding wealth management and protection as a production process is helpful, not in the least because it asks pertinent questions such as: what are the products? and: who are the suppliers? Wealth chains can be differentiated along three lines: (I) ‘the complexity of information and knowledge transfer’, which can vary from off-the-shelf products to complex financial innovations, (II) ‘the regulatory liability involved in transactions and the ease of multi-jurisdictional regulatory intervention’, which addresses the power of the regulator in overseeing the production, and (III) ‘the capabilities of suppliers to create solutions to mitigate challenges to the status of the product or service by regulators’ (Seabrooke and Wigan Citation2017, p. 13). This third and last point directly addresses the role of the wealth defence industry, as we term it. In sum, the GWC framework provides a perspective which treats taxation issues, regulatory arbitrage opportunities and corporate complexity as a system which is enabled and maintained through professional networks.

The design of wealth defence schemes requires extensive expertise on international law, accounting, and tax regulation. The Big Four accountancy firms (PwC, Deloitte, EY and KPMG), which dominate the accountancy market, are better positioned to deliver these services than their smaller competitors. First, their size enables them to reach a higher level of knowledge intensity (Von Nordenflycht Citation2010). This is rewarded by companies, which rely on expertise regarding corporate structures, international law and taxation. Second, the widespread geographic presence of the Big Four auditors enhances their knowledge about strategies which span multiple countries. It strengthens their capacity to get access to authorities in advantageous jurisdictions and moreover enables the spread of new products across a large network of offices to clients.

During the nineteenth century, audit firms established themselves as a professional group around the business of audit provision. The professional orientation of these auditors started to change from the 1970s onwards, when the previously nationally oriented business underwent a process of internationalisation (Strange Citation1996). They started to diversify into more lucrative business opportunities and changed from pure audit firms to accountancy firms with multiple fields of expertise. In 1990, the revenue from auditing services accounted for a full 53 per cent of the total revenue of accountancy firms (Murphy and Stausholm Citation2017). Currently, only 36 per cent of income of the largest accountancy firms is earned through audit services. The largest share of income stem from tax services (23 per cent) and from other consulting services (41 per cent) (Murphy and Stausholm Citation2017). For auditing services, the accountant has to ensure that the financial reports give a ‘full and fair view’ of the company’s financial statement while guaranteeing independence from the subject matter (Strange Citation1996). This activity is in line with the initial idea of accounting as an activity in favour of market stabilisation. In contrast, tax services include the filing of tax returns as well as the provision of information concerning certain tax treatments and consulting – the activity with the highest margins – entails the restructuration of organisations, ‘shifting income across jurisdictions or time, or reclassifying the tax treatment of transactions’ (Maydew and Shackelford Citation2005, p. 9). Besides the diversification into higher fee-paying business activities, accountancy firms increased in size and power over the years. Through a series of mergers and later through the collapse of Arthur Andersen, the market leaders shrank from the Big Eight to the Big Four. In 2016, the total revenue of all Big Four auditors amounted to €120bn (Murphy and Stausholm Citation2017). The four largest law firms, in comparison, made €11.4bn in total revenue in 2018 (Investopedia Citation2019).

The relationship of accountancy firms to corporations is peculiar because accountancy firms can use auditing as the ‘foot in the door’ (Stenger Citation2017). As auditors, accountancy firms accumulate a high level of knowledge about their clients. When checking financial statements, they have direct access to a broad range of information concerning organisational, financial and operating activities of the corporation under audit. Due to the high complexity of information in the development of wealth defence strategies and the limited reach of regulatory actors, there is room for ‘creative accounting’ and legal innovation. Sikka and Mitchell (Citation2011) attribute strong agency to the big accountancy firms in pushing the wealth defence business, claiming that certain schemes are ‘produced off-the-shelf’ and ‘mass marketed’. Employees, they find in a case study on KPMG, receive training in selling the tax products to clients and are rewarded by success rate.

The Country Specific Nature of Wealth Defence

While ‘creative accounting’ has been discussed by various authors (Sikka and Mitchell Citation2011, Sikka and Willmott Citation2013), the capacity of accountants to facilitate deal making with tax authorities in different countries has received less attention. As proposed by the GWC framework, wealth defence is shaped through the ‘capabilities of suppliers’ to develop tax products, which, and this is important, ‘will not be contested by local regulatory instances’ (Seabrooke and Wigan Citation2017, p. 13). Wealth chains only flourish because states ‘bifurcate’ their laws, applying different rules to domestic than to internationally mobile actors (Fichtner Citation2016, Seabrooke and Wigan Citation2017). We put forward that the provision of successful advice on tax avoidance schemes is therefore country specific: it depends on the jurisdiction in which the client is located.

There are at least two mechanisms which could enhance or hinder the effectiveness of accountancy firms’ tax advice provision across countries. A first mechanism is linked to the size of the professional service sector in a specific jurisdiction (Murphy and Stausholm Citation2017): a higher workforce is likely to generate a higher knowledge intensity about the tax laws and the loopholes it creates, but also about the ways in which tax authorities enact the laws in practice. Murphy and Stausholm (Citation2017) show that in relative terms, the Big Four have the highest presence in Bonaire, the British Virgin Islands, Gibraltar (UK), Monaco, Cayman Islands, Greenland, Iceland, Guernsey and Bermuda. Many of those jurisdictions in which the Big Four have a disproportionately high presence relative to the host country's GDP are sink offshore jurisdictions. A second mechanism is linked to the range of regulations which directly target accountancy firms themselves. Kanagaretnam et al. (Citation2016), who are among the first to study the link between accountancy firms and tax aggressiveness in an international context, find variation in the influence of accountancy firms according to the audit environment of the countries they study.

How Do Accountancy Firms Facilitate Aggressive Tax Planning?

While most evidence for the practice of accountancy firms to market innovation and tax schemes across their network is based on qualitative case studies and journalistic revelations, some studies explored the issue systematically. Jones et al. (Citation2018) arguably provide the first large-scale analysis which places the involvement of accountancy firms in the wealth defence business at its core. The authors adopt a perspective focusing on the internationalisation strategies of firms. Refining the classical ‘internationalisation theory’, which provides a framework for understanding the decisions of companies to build entities abroad, they add specific hypotheses at the country and firm level on the expansion into jurisdictions with favourable tax environments. They find that corporations which take on a Big Four auditor have more subsidiaries in tax havens than companies with a smaller auditor and they have a significantly higher growth rate of tax haven-based subsidiaries than firms with another auditor (Jones et al. Citation2018).

Although our theoretical perspective is different from that of Jones et al. (Citation2018), our research design is comparable. We extend their approach by increasing the sample size of the panel data fourfold to about 27k MNCs, and by diversifying the corporate structures we investigate. After all, wealth defence is not solely about locating subsidiaries in favourable tax jurisdictions. The relatively new literature on corporate structures and tax optimisation shows that from a companies’ perspective, particular organisational forms, such as holding entities and management entities, play an important role in tax optimisation (Reurink and Garcia-Bernardo Citation2020). Additionally, the general structure of corporate networks and ownership complexity can be advantageous for companies’ tax planning (Unctad Citation2016). More complex ownership structures enhance the difficulties for state authorities to keep track of companies’ tax liabilities and of other regulatory requirements. Besides offshorisation strategies, wealth defence plans thus also entail the use of particular organisational forms and attempts to render ownership relations hard to trace. By including multiple corporate structures in our research design, we therefore improve the robustness of the study developed by Jones et al. (Citation2018). Also, the diversification of features that we study prepares the ground for future research which could compare the activities of accountancy firms to those of other service professionals in the wealth defence industry such as law firms or consulting companies.

The following section discusses the details of the three wealth defence strategies we consider: 1/ localisation strategies, in particular the use of Offshore Financial Centers, considering both conduit and sink OFCs; 2/ organisational forms, in particular the use of holding subsidiaries and management entities; and 3/ the complexity of corporate structures, measured by the depth, width and entropy of the subsidiary network. All three strategies relate to the protection of economic resources, in that they allow corporations to reduce tax liabilities in the territory where productive economic activity takes place. While the literature establishes that diverse types of corporate structures have an influence on tax planning, not much is known about the involvement of accountancy firms in setting them up. We therefore expect that clients of the Big Four have a higher prevalence of all of those three features. In addition, we expect that accountancy firms provide more efficient solutions for bigger clients than for smaller clients, as the difference in economic resources (value added) and capacities to exploit international regulatory advantages are unequally distributed among small and large companies and act strongly in favour of large MNCs. Finally, we are the first to explore how the influence of auditors on tax-related structures varies between countries. We assume that the Big Four have a strong effect on their clients’ tax avoidance structures in the jurisdictions where they have a disproportionately high presence – namely in sink offshore jurisdictions, such as the Cayman Islands or Bermuda.

Methods

Dependent, Independent and Control Variables

The main independent variable in our model describes whether the firm’s auditor is one of the Big Four or a smaller auditor. While our data contains information about the link between auditors and businesses, it does not contain information on the fee structure. In other words, we do not know to what extent the audit client also receives tax and consulting services from the same accountancy firm. However, as advanced by Jones et al. (Citation2018, p. 4), ‘an auditor has to sign off on a firm’s accounts, thereby giving credibility to an MNC’s corporate structure’. Even though the Sarbanes Oxley Act in the US increased regulatory restrictions, corporations are still able to use the same accountancy firm for both tax and audit purposes: ‘It is up to firms to self-regulate themselves via the audit committee to ensure there is no conflict of interest’. How well firms implement these regulations is largely unknown (Jones et al. Citation2018, p. 15). This implies that the efforts to restrict the simultaneous offer of audit and tax services did not curb this dual role in practice.

Our dependent variables relate to three strategies of wealth defence. First, we study the effect of the Big Four on the usage of sink and conduit offshore financial centres. Sink jurisdictions attract and retain foreign capital through low corporate taxes. Examples are the Cayman Islands or Bermuda. Conduit jurisdictions such as the Netherlands and Ireland are destinations which route investments from one country to another through interest payments, royalties, dividends or profit repatriation (Garcia-Bernardo et al. Citation2017). Investments are effectuated in conduit jurisdictions because they enable a low to zero tax capital transfer (classification following Garcia-Bernardo et al. Citation2017 in Appendix A1).

Second, in terms of organisational forms, we investigate the effect on the use of holding companies and management entities. The former are subsidiaries which hold equity or debt stakes or important wealth-creation assets such as intellectual property. Palan et al. (Citation2010) as well as the world investment report (Unctad Citation2016) identified the use of holding companies as a common strategy to shift profits to low-tax jurisdictions. Alongside multiple other functions, holding companies collect dividend income from the operating subsidiaries and transfer it on to the parent company. By choosing a favourable location, taxation on the transfer of dividends can be circumvented (Reurink and Garcia-Bernardo Citation2020). We consider holding companies those with a controlling shareholder and fully owning a subsidiary. This approach is preferable over the sector of the entity, since the later is self-reported. We did, however, run a robustness check using the self-reported sector, finding consistent results. With regards to management entities, 17 per cent of the companies set up a shared service centre with the objective of reducing their tax burden, for example by charging entities in other countries, shifting the profit to the low-tax jurisdiction (Deloitte’s 2015 Global Shared Services Survey). We operationalise shared service centres using the sectors ‘Legal and accounting activities’ (NACE 69), ‘Scientific research and development’ (NACE 72), ‘Other professional, scientific and technical activities’ (NACE 74), ‘Advertising and market research’ (NACE 73) and ‘Office administrative, office support and other business support activities’ (NACE 82).

Third, we investigate the effect of auditors on the complexity of corporate structures, namely the depth, the width and the general complexity of the subsidiary network (see Appendix A2 for details). Ownership complexity renders activities opaque, as stated by Wagener and Watrin (Citation2014, p. 10): ‘The more complex a transaction is structured, the more difficulties a tax authority has to understand the whole structure and the more jurisdictions have to work together to detect illegal practices’.

To separate the expected relations from other influences, we consider several confounders. First, we include three measures of MNC size. We control for the total number of subsidiaries of each company’s network. A larger subsidiary network is likely to result in a higher number of all features under study. To avoid endogeneity problems, the total number of subsidiaries is calculated as the total number of subsidiaries minus the subsidiaries in the feature under study. We control for the squared term of the total number of subsidiaries to account for the fact that larger companies are more likely to be audited by one of the Big Four auditors. And we control for the operating revenue of the MNC. The operating revenue was measured as the revenue generated from the primary business activities of the firm, taking the average over the years 2012–2017. Second, we assume that the auditor effect varies from one country to another. We introduce random intercepts and random slopes for the country of incorporation, to show how the auditor effect on the three features changes from one country to another. Previous studies (Kanagaretnam et al. Citation2016) established that the institutional characteristics of different countries have an impact on auditor influence; however, they did not present the concrete country variations. We expect that (I) the auditor effect depends on the regulatory environment which enables or restricts the provision of certain tax advice services by auditors and that (II) auditors are more influential in sink jurisdictions, because their overproportionate presence in those areas suggests that they have a higher knowledge intensity on the tax regulation and the practices of the local tax authorities. Third, we control for industry differences to account for sector-specific variation in income mobility. Wagener and Watrin (Citation2014) point out that income-mobile sectors such as the pharmaceutical, high-tech and service industries could be more prone to pursue tax avoidance strategies and develop complex ownership structures. Finally, we control for firm age, which could be influential with regards to the depth of the ownership chains. This is the case if the development of subsidiary networks follows a logic of ‘the historical accident’, where the acquisition of lower level subsidiaries accumulates over time (Lewellen and Robinson Citation2013, Unctad Citation2016, p. 136). and present the main descriptive statistics of the variables included in the models (.

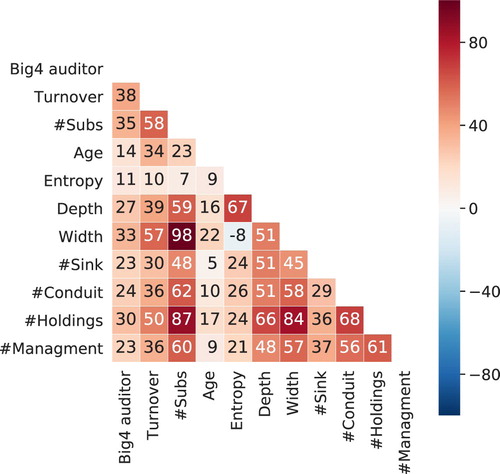

Figure 1. Heatmap of variables used in the models. Red indicates a positive correlation, blue a negative correlation. The darker the colour, the stronger the correlation.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of variables used in the models.

Data

We extracted our data from Orbis, a database covering a large variety of information on over 200 million corporate entities around the globe (Bureau van Dijk Citation2016). The company records stem from regulatory reports by public institutions. We retrieved information on ownership chains for each MNC that is a global ultimate owner (GUO) by finding all direct subsidiaries (where we set an ownership threshold of 50 per cent). Then we continued by finding all direct subsidiaries of the subsidiaries, and in this way finding the size of each layer (width), and the number of layers (depth). From the corporate structure, we measured the number of subsidiaries placed in sink and conduit OFCs. MNCs that are GUOs do not have controlling shareholders themselves, but do have at least one subsidiary they own by over 50 per cent. We only included companies in the sample with at least one subsidiary in a foreign country; with auditor information available; with an active status; and with information on their location, sector and date of incorporation. Additionally, companies which have multiple auditors that include both Big Four auditors and other auditors were excluded from the sample. The resulting datasets, based on longitudinal data for the years 2007–2017, contained 27.168 MNCs and 41.036 observations.

Analytical framework

To study the influence of auditors on their clients’ corporate structures, we ran models in a stepwise procedure. Model (A) is a mixed effects model with company random effects and all the control variables. In Model (B) we added an interaction term between the auditor and the size of the company. In Model (C) we added a random intercept for the country of the MNC to the model. Companies are now nested within countries and each country to has its own intercept. This accounts for the idea that the observations are nested in countries and that initial levels of corporate features vary for companies located in different countries. In Model (D) we added a random slope effect for the country. This accounts for the variation in auditor influence according to the country in which the MNC is located. Model (D) was built as follows: is the value of y for unit (company) i in cluster (country) j.

is the overall mean of the intercept. The intercept is allowed to vary randomly across clusters (countries), where

is the intercept residual.

is the overall mean of the slope.

is the slope residual and

is the unit level.

is the unit residual.

Robustness Checks

The analysis of the data were carried out in two phases. In the first one, we collected the data from 2015 and created the statistical models based on these data. In the second phase, we expanded the dataset, taking a longitudinal sample. Such a research design allows us to reduce biases by providing a quasi-replication of our original results. For an additional robustness check we applied propensity score matching. The matching allowed us to create a comparable sample (see Appendix A3), matching 5983 corporations audited by the Big Four to 1482 corporations not audited by the Big Four. We then ran the regression on the matched sample, finding comparable results.

Data Restrictions

Unfortunately, the quality of the information on auditors in Orbis does not allow us to run a longitudinal fixed-effects model to test how the change from one type of auditor to another affects wealth defence strategies. Our database contains 4.5 million auditors. Of those, we have information on appointment date on 2.5 million auditors, and the resignation date on 2.3 million of them. However, the vast majority of the resignations are recorded in 2017 which suggests that a longitudinal analysis is not adequate.

Empirical Results

In total, 53.3 per cent of the companies in our sample are audited by one of the Big Four, while 44.6 per cent are audited by any other accountancy firm. Appendix A4 shows the number of clients by auditor for each country. The figure highlights that the percentage of large clients audited by the Big Four is overall higher in OFCs. shows the logged frequency of features related to wealth defense by auditor. A decreasing line implies that there are more companies which have a lower number than there are companies with a high number of those characteristics. Taking ‘subsidiaries in sink OFCs’ (#Sink) as an example, we see that most companies have a small number of their subsidiaries located in countries such as the Bermudas, the British Virgin Islands or Luxembourg. In relative terms, few companies locate a large count of subsidiaries in sink OFCs.

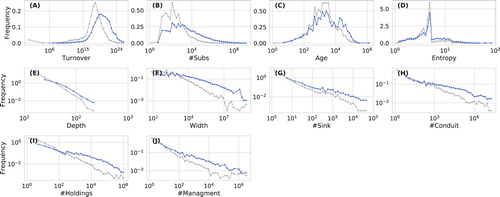

Figure 2. Frequency distribution of all variables by auditor. The colour of the lines indicates the auditors: in blue are companies audited by the Big Four, in grey are companies audited by any smaller accountancy firm. The x-axis is a standardised measure for number of the feature, the y-axis is the frequency of companies in our sample.

shows that a higher share of large companies in terms of revenue (Turnover) and in terms of total number of subsidiaries (#Subs) are audited by one of the Big Four auditors. Most interestingly, shows that companies audited by the Big Four have higher levels for all the features that we study. However, the figures equally show that there are companies that are audited by smaller auditors which have a high use of wealth defence-related features. The descriptive approach taken here does not allow us to disentangle the size effect from the auditor effect however. The difference could be a mere reflection of the bias in the size of the companies. Stated differently: if Big Four auditors are responsible for a higher number of large clients than other auditors, then the higher number of any feature, such as the use of OFC subsidiaries, could be a result of the size distribution of their clients. In our sample 88 per cent of the companies have less than 100 subsidiaries. Of the largest 10 per cent of firms, 8815 are audited by the Big Four and 976 are audited by any other auditor. To control for this, we conduct regression analyses in a next step.

Auditor Influence on Wealth Defence Strategies

Our regression results lend support to most, but not all of our expectations. First, they show that having a Big Four auditor is positively related to the use of sink OFCs, conduit OFCs, holdings and management entities as well as to entropy and depth of the subsidiary network. The models do not show a positive relationship between the Big Four auditors and the width of their clients’ subsidiary network (a measure of network complexity). The analyses of the interplay between MNC size (number of subsidiaries) and auditor influence showed that there is an interaction effect between those two variables for most of the features that we study.

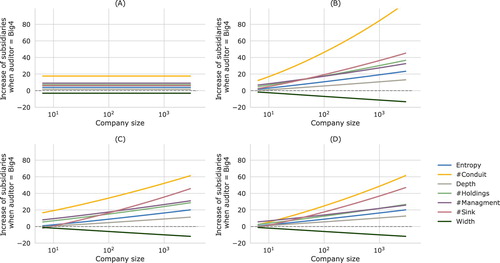

shows the outcome of the regression models. The lines present the proportional difference of the level of a feature between companies that are audited by a Big Four auditor and other companies for a given size of the company. The x-axis is the size of the company and the y-axis is the proportional difference in the level of a feature (such as the use of sink OFCs). We ran the models in multiple steps. Model (A) is the baseline model. In Model (B) we added an interaction effect between the auditor and the size of the client company, the line can therefore increase or decrease with the size of the company. In Model (C) we added random intercepts for the country effect and in Model (D) we added random slopes for the country effects. For readability, the figures do not indicate the confidence intervals (for significance levels see Appendix A5).

Figure 3. Proportional difference in levels of wealth defence-related features by auditor. (A) fixed effects model, (B) model with interaction term between company size and auditor, (C) random intercepts at the country level, (D) random slopes at the country level. The figures indicate the proportional difference between companies audited by the Big Four versus companies audited by any other accountancy firm in relation to the size of the company. As an example, if the yellow line crosses the point where the y-axis is at 20, this indicates that clients of the Big Four have a 20% larger use of conduit subsidiaries than other companies of the same size.

In the following we interpret the findings of Model (D). Keeping all other variables constant, companies with around 100 subsidiaries which are audited by a Big Four auditor have on average 17.9 per cent more subsidiaries located in sink jurisdictions (p = 0.00 auditor effect, p = 0.00 interaction effect). Larger companies, with a network counting 1000 subsidiaries have on average 37.2 per cent more daughter companies placed in sink OFCs if they are audited by a Big Four. Those are jurisdictions such as Luxembourg, Hong Kong, the British Virgin Islands and Bermuda, in which value gets withdrawn from the economic system (Garcia-Bernardo et al. Citation2017). Companies with 100 subsidiaries have on average 25 per cent more subsidiaries located in a conduit OFC if they are audited by one of the Big Four (p = 0.00 auditor effect, p = 0.00 interaction effect). With 1000 subsidiaries they have on average 48.2 per cent more subsidiaries in countries such as the Netherlands, the United Kingdom or Switzerland. These countries are attractive for companies to channel their value to sink countries.

Furthermore, companies with 100 subsidiaries which are audited by the Big Four have on average 14.3 per cent more management entities and 12.4 per cent more holding entities than companies which are audited by any other auditor (p = 0.85/p = 0.18 auditor effect, p = 0.00/p = 0.00 interaction effect). Holding companies can be used to reduce the tax liabilities on interest and dividend payments from subsidiaries to parent companies or to channel royalty payments to other countries in tax efficient ways (Reurink and Garcia-Bernardo 2018). Management entities partly respond to the objective to reduce tax liabilities, for example through transfer pricing.

The auditor effect on complexity measures is less strong. There is a significant positive relationship between Big Four auditors and entropy (9.1 per cent difference, p = 0.00 fauditor effect, p = 0.00 interaction effect) and between the Big Four and the depth of their clients network (5.7 per cent difference, p = 0.00 auditor effect, p = 0.00 interaction effect). The effect on the width of the subsidiary network is negative (5 per cent difference, p = 0.06 auditor effect and p = 0.00 interaction effect).

Thus, companies which are audited by Deloitte, KPMG, EY or PwC have a higher use of tax-related localisation strategies and strategies concerning organisational forms (holding and management entities) than companies audited by smaller accountancy firms such as Grant Thornton or Baker Tilly. There is equally an effect on the general complexity of their clients’ subsidiary network if measured in terms of entropy or in terms of the depth. However, there is no positive relationship between Big Four auditors and their clients’ subsidiary network complexity if measured in terms of width.

Our results show that the incentives to provide wealth defence strategies increase with growing size of the company, measured by number of corporate entities. Significant interaction effects between auditor and the size of the company suggest that the effect of the Big Four versus any other auditor increases with the size of the company for certain features. This relationship holds for the number of sink OFCs, conduit OFCs, holdings, management entities – as well as for the entropy and the depth of clients’ subsidiary networks, as shown in . Although small companies also have a higher use of those features if they are audited by one of the Big Four rather than by a smaller auditor, the difference of the auditor effect is stronger for large companies. Among all features, this interaction effect is strongest for the number of subsidiaries in conduit OFCs. Overall, our results provide evidence for the influence of the Big Four auditors on their clients’ localisation strategies, on the share of holding and management entities in their network of subsidiaries and on certain measures of network complexity. This influence increases with the size of their clients. We therefore show that clients of the Big Four do not solely have a higher use of ‘tax havens’ (Jones et al. Citation2018), but for the first time we also establish that their clients distinguish themselves from other corporations through tax avoidance-related legal forms and corporate complexity. This relationship holds when controlling for various potential confounders and suggests that accountancy firms have an impact on the ways in which their clients structure and develop their wealth defence strategies.

Country Effects

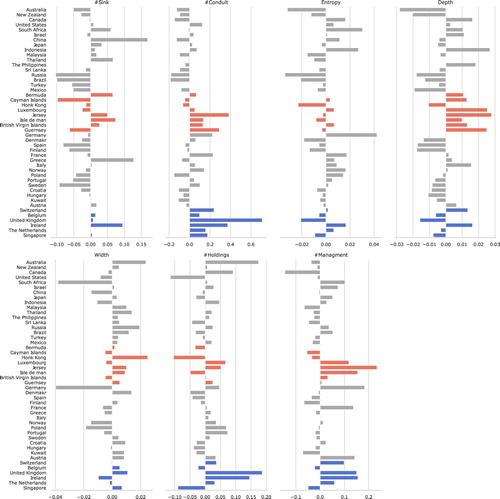

The hierarchical nature of the regression models allows us to study the variation between the countries of client location. Through random intercepts at the country level we can show that there is considerable variation in the average use of the features under study from one country to another (Figure A6 in Appendix A6). In Model D we added random slopes for the countries. The random slope model shows the effect of an auditor on the use of features (such as sink OFCs in the network) if the parent company is located in a particular jurisdiction. shows the slope effects for each country. Based on the expectation that the knowledge intensity of accountancy firms is higher in countries where they have a high presence, we proposed that the effect of accountancy firms on their clients’ corporate structures would be stronger in sink countries. The analyses show, however, that other mechanisms are at play. Regarding the use of conduit jurisdictions, the effect of the auditor is comparatively strong on MNCs incorporated in a conduit OFC (Switzerland, Belgium, Great Britain, Ireland, the Netherlands and Singapore). In addition, accountancy firms have a strong effect on the use of conduit jurisdictions in the subsidiary network for companies located in Germany and France as well as in Guernsey and Jersey. For the use of management companies, we observe a similar pattern. With regard to the use of holding entities and the corporate complexity measured as depth and width of a corporate network we do not find any consistent geographic pattern of auditor influence.

Figure 4. Cross-country differences in auditor effect. The x-axis show the slope effects from Model (D). To the right, the effect is positive, to the left, the effect is negative. The longer the bar, the stronger the effect. In red are sink OFCs and in blue are countries categorised as conduit OFCs. Only countries with over 100 companies are shown.

In addition to our main findings, the sector control variable provides interesting insights. Comparing with the manufacturing sector, companies within mining have a higher presence in sink offshore jurisdictions and a different pattern than most other sectors in the general complexity measures (Appendix A7).

Discussion

We examined the role of accountancy firms as part of the wealth defense industry. A mixed-level regression applied to a large-scale dataset revealed significant differences in the tax planning strategies between MNCs audited by the Big Four of Deloitte, KPMG, EY or PwC and those MNCs audited by smaller accountancy firms such as Grant Thornton, BDO or Baker Tilly. Looking at three types of corporate strategies which relate to tax optimisation – namely localisation strategies, organisational forms and corporate complexity – we find that these strategies occur more frequently in the corporate network of clients which are audited by one of the Big Four. We show that clients of the Big Four have a higher number of subsidiaries placed in jurisdictions which provide secrecy and low corporate taxes – so-called sink OFCs – and that they have higher presence in conduit jurisdictions which offer legal certainty, stability and advantageous tax conditions on the transfer of economic resources. We show that corporate tax optimisation plans do not solely consist of placing subsidiaries in jurisdictions with favourable tax regimes (sink OFCs) – rather they comprise an intertwined set of approaches. Accounting for the multidimensionality of wealth defence strategies, we show that the Big Four enhance the use of holding and management entities and that clients of the Big Four have more complex corporate networks if measured in terms of entropy and depth than other corporations. These results suggest that Big Four accountancy firms do indeed have an important influence on organisational and corporate restructurings of their clients – restructurings which potentially drive international tax avoidance.

To disentangle corporate structures with a focus on the legal-financial logics marks a turn in theories of the corporation (Seabrooke and Wigan Citation2014, Bryan et al. Citation2017, Seabrooke and Wigan Citation2017, Reurink and Garcia-Bernardo Citation2020). Previous accounts, developed by the Global Value Chains literature (Gereffi et al. Citation2005), mainly discussed governance aspects and the flows of goods and services to theorise the corporation. By studying the fiscal logics of complex corporate structures, this study advances insights in the fundaments of the ‘great fragmentation of the firm’ (Reurink and Garcia-Bernardo Citation2020). In a legal-financial perspective, financial disaggregation is an important force structuring corporations’ geographical expansion and the progressing subsidiarisation of the corporate form and, moreover, it is key in understanding global tax games.

Furthermore, the study showed that the influence of the Big Four is stronger for MNCs with many subsidiaries than on MNCs with a small subsidiary network. The higher occurrence of wealth defense features among larger clients may be explained by higher fee opportunities for accountancy firms. This finding is important considering the fact that a large share of corporate wealth worldwide is concentrated in the hands of a very few large companies. Whether or not large companies are enabled to decouple financial production from physical production thus has a considerable impact on global tax revenues.

Another contribution of our study is to highlight international variation in accountancy firm’s influence on their clients’ tax planning. We are among the first to show how the influence of accountancy firms on corporate structures varies across countries. The hypothesis that the auditor effect would be strongest in those countries in which accountancy firms have an overproportionate presence, namely in sink countries, did not hold for those wealth defence strategies that we studied. We find that the effect of the Big Four on the use of subsidiaries in conduit jurisdictions and on the use of holding entities is higher for clients which are incorporated in Switzerland, Belgium, Great Britain, Ireland, the Netherlands and Singapore. It would be interesting for further research to examine whether the patterns that we find is linked to logic proposed by Kanagaretnam et al. (Citation2016), who claim that the influence of accountancy firms on tax aggressiveness depends on the regulations that directly target accountancy firms such as the auditor litigation risk and the audit environment. Such a next step would benefit from the observation that ‘in the study of international politics, we need to consider corporations as a social force analytically equivalent to states’ (Babic et al. Citation2017, p. 39).

Indeed, corporations and states are increasingly active and juxtaposed actors. Reflecting on the three strategies that we distinguished in this study, the localisation strategy is perhaps the most clear cut example of playing out states against each other, where small jurisdictions with relatively little domestic production cater to the need of low taxation, lenient regulation and very high secrecy at the expense of jurisdictions with large productive economies. Through the three tax strategies corporations ‘play out’ the states against each other in order to reduce their tax liabilities. Offshore Financial Centres for one commercialise their sovereignty at the expense of ‘onshore’ states. And corporations exploit these opportunities aided by a wealth defense industry that liaisons between the corporations and the state.

Conversely, the third strategy of setting up complex corporate structures plays out states versus corporations as the corporations are able to render their activities opaque and obscures them from state scrutiny. In a very different manner, it is a well-known strategy used by criminal organisation across the globe. Tackling this strategy requires significant state investment and, perhaps even more important, requires the state to have intimate knowledge of the most recent and most complex tax evasion strategies. This reminds us of the fundamental problem of financial oversight and regulation, where states and state regulators have to compete in a somewhat unfair battle with financial corporations to hire ‘the best and the brightest’ in order to regulate financial innovation. It’s a game where states usually loose out.

The causal direction of the relationship between demand and offer of profit shifting services remains left open by our study. It is possible that accountancy firms hold a rather passive position and exclusively supply tax and legal advice on behalf of requests by aggressive multinational companies. The image of neutrality which is perpetuated by the profession and the amplification of legal restrictions over the last decade support this vision. However, the insights into the activities of the Big Four through leaks and case-based investigations suggest that accountancy firms are proactive agents in the profit shifting business. The increasing pressures for commercialisation, as well as the capacity of accountancy firms to collect and manage knowledge through ‘centres of excellence’ support an agentic version of accountancy firms’ involvement in wealth defence. While for us, the second scenario is more likely, in either of the two, accountancy firms play a decisive role in the wealth defence business: either as active or as passive suppliers of financial and corporate innovation.

Ideally, we would have made use of data on fees, indicating the income generated for tax, consulting and audit services for each accountancy firm separatly. There are a handful of studies which do make use of fee level data. Following the Enron scandal, the U.S. authorities requested the publication of financial information for accountancy firms (Maydew and Shackelford Citation2005, Hogan and Noga Citation2012). However, for more recent years and for most regions of the world, this type of data is not available. Ultimately, considering that there is a positive relations between auditor and tax-related corporate structures, it is likely that companies still receive considerable support in tax and organisational planning from the accountancy firm that is their official auditor.

We see our contribution as a starting point for further work, and therefore exploratory in nature. We believe our work makes relevant contributions to an ongoing issue of societal and economic relevance. Accountancy firms uphold an image of neutrality and perpetuate their representation as an independent supervisory organ which contributes to economic stability. In the last decades, journalistic revelations and several case studies came to question this flawless image. By looking at a database covering most companies worldwide, this study provided quantitative evidence that the involvement of auditors in the development of wealth defence strategies is not just the exception. It is a relationship which has a systematic component and holds across all of the Big Four auditors. Based on the findings of this study, we argue that not only the academic focus, but also the policy considerations about wealth defence, international tax avoidance and regulatory competition should pay more attention to the role of accountancy firms as crucial intermediaries. With the most recent proposal on transparency of intermediaries, the European commission is moving in this direction. Estimating that tax avoidance practices cost public budgets for the EU around €50–70 billion (Dover et al. Citation2015), the commission requested intermediaries to report on the provision of services which are related to wealth defence strategies. Additionally, following Murphy and Saisholm (2017), we suggest that the wealth defense industry should move towards higher transparency levels with regard to their activities; making public where they are located, how many people they employ and how their organisational and functional structure is set up.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (1.2 MB)Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Luc Fransen, Milan Babic, Diliara Valeeva, Frank Takes, Arjan Reurink, Jouke Huijzer and Vladeta Ajdacic for their comments on earlier versions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Lena Ajdacic

Lena Ajdacic holds a research master degree in Social Sciences, with a specialisation in political economy and quantitative research methods from the University of Amsterdam. She is doing her PhD in the FNS project ‘The Rise of the Financial Elite – Access, Integration and Spread of Power’ at the University of Lausanne.

Eelke M. Heemskerk

Eelke M. Heemskerk is Associate Professor at the Political Science department, University of Amsterdam. He is Principal Investigator of the CORPNET research group at the Amsterdam School for Social Science Research, where he investigates global networks of corporate control. His research focusses on networked elements of corporate governance and corporate control, such as board networks, complex structures in corporate ownership, the rise of index capitalism, and the transnational activities of state-owned enterprises.

Javier Garcia-Bernardo

Javier Garcia-Bernardo received his PhD in Political Science. He did his M.Sc. in Computer Science at the University of Vermont (USA), specialising in Complex Systems. Javier’s work at the CORPNET project uses computational methods to analyse the effects of tax avoidance. He is interested in understanding how multinational corporations organise across countries in order to minimise tax payments, and how jurisdictions provide opportunities for it.

References

- Arnold, P.J., 2009. Global financial crisis: the challenge to accounting research. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 34 (6-7), 803–9. doi: 10.1016/j.aos.2009.04.004

- Babic, M., Fichtner, J., and Heemskerk, E.M., 2017. States versus corporations: rethinking the power of business in international politics. The International Spectator, 52 (4), 20–43. doi: 10.1080/03932729.2017.1389151

- Beer, S. and Loeprick, J., 2015. Profit shifting: drivers of transfer (mis) pricing and the potential of countermeasures. International Tax and Public Finance, 22 (3), 426–51. doi: 10.1007/s10797-014-9323-2

- Bryan, D., Rafferty, M., and Wigan, D., 2017. Capital unchained: finance, intangible assets and the double life of capital in the offshore world. Review of International Political Economy, 24 (1), 56–86. doi: 10.1080/09692290.2016.1262446

- Bureau van Dijk, 2016. Orbis database. Available from: https://www.bvdinfo.com.

- Clausing, K.A., 2016. The effect of profit shifting on the corporate tax base in the United States and beyond. Available at SSRN 2685442.

- Council of the European Union, 2018. Press release: ‘corporate tax avoidance: transparency rules adopted for tax intermediaries’.

- DeBacker, J., Heim, B.T., and Tran, A., 2015. Importing corruption culture from overseas: evidence from corporate tax evasion in the United States. Journal of Financial Economics, 117 (1), 122–38. doi: 10.1016/j.jfineco.2012.11.009

- Dover, R., et al., 2015. Bringing transparency, coordination and convergence to corporate tax policies in the European Union. European Parliamentary Research Service.

- European Commission, 2015. A fair and efficient corporate tax system in the European Union: 5 Key Areas for Action. COM(2015) 302 final.

- European Commission, 2016. Anti-Tax avoidance package: next steps towards delivering effective taxation and greater tax transparency in the EU. COM(2016) 23 final.

- Fichtner, J., 2016. The anatomy of the Cayman Islands offshore financial center: Anglo-America, Japan, and the role of hedge funds. Review of International Political Economy, 23 (6), 1034–63. doi: 10.1080/09692290.2016.1243143

- Garcia-Bernardo, J., et al., 2017. Uncovering offshore financial centers: conduits and sinks in the global corporate ownership network. Scientific Reports, 7 (1), 6246. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-06322-9

- Genschel, P., Kemmerling, A., and Seils, E., 2011. Accelerating downhill: how the EU shapes corporate tax competition in the single market. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 49 (3), 585–606.

- Genschel, P. and Schwarz, P., 2011. Tax competition: a literature review. Socio-Economic Review, 9 (2), 339–70. doi: 10.1093/ser/mwr004

- Genschel, P. and Seelkopf, L., 2016. Did they learn to tax? Taxation trends outside the OECD. Review of International Political Economy, 23 (2), 316–44. doi: 10.1080/09692290.2016.1174723

- Gereffi, G., Humphrey, J., and Sturgeon, T., 2005. The governance of global value chains. Review of International Political Economy, 12 (1), 78–104. doi: 10.1080/09692290500049805

- Haberly, D. and Wójcik, D., 2015. Regional blocks and imperial legacies: Mapping the global offshore FDI network. Economic Geography, 91 (3), 251–280. doi: 10.1111/ecge.12078

- Hogan, B. and Noga, T., 2012. The association between changes in auditor provided tax services and long-term corporate tax avoidance. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1539637.

- icij.org, How Blackstone Group uses ‘Fairly Aggressive’ tactics to slash its tax bill. Available from: https://www.icij.org/investigations/paradise-papers/blackstone-group-uses-fairly-aggressive-tactics-slash-tax-bill/ [Accessed November 2018].

- Investopedia, 2019. Available from: https://www.investopedia.com/articles/personal-finance/010715/worlds-top-10-law-firms.asp [Accessed June 2019]

- Janský, P. and Palanský, M., 2017. ‘Estimating the scale of corporate profit shifting: tax revenue losses related to foreign direct investment, In Annual Congress of the IIPF, Tokyo.

- Jones, C. and Temouri, Y., 2016. The determinants of tax haven FDI. Journal of World Business, 51 (2), 237–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jwb.2015.09.001

- Jones, C., Temouri, Y., and Cobham, A., 2018. Tax haven networks and the role of the Big 4 accountancy firms. Journal of World Business, 53 (2), 177–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jwb.2017.10.004

- Kanagaretnam, K., et al., 2016. Relation between auditor quality and tax aggressiveness: implications of cross-country institutional differences. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory, 35 (4), 105–35. doi: 10.2308/ajpt-51417

- Lanz, R. and Miroudot, S., 2011. Intra-firm trade: patterns, determinants and policy implications. OECD Trade Policy Papers, No. 114, OECD Publishing, Paris.

- Lewellen, K. and Robinson, L.A., 2013. Internal ownership structures of US multinational firms. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2273553 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2273553.

- Maydew, E.L., and Shackelford, D.A., 2005. ‘The changing role of auditors in corporate tax planning,’ (No. w11504) National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Murphy, R. and Stausholm, S.N., 2017. The Big Four: a study of opacity. Cambridgeshire: GUE/NGL – European United Left/Nordic Green Left.

- OECD, 2015. Measuring and monitoring BEPS, Action 11 – 2015 final report. Paris: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

- Palan, R., 1998. Trying to have your cake and eating it: how and why the state system has created offshore. International Studies Quarterly, 42 (4), 625–43. doi: 10.1111/0020-8833.00100

- Palan, R., Murphy, R., and Chavagneux, C., 2010. Tax havens: how globalization really works. London: Cornell University Press.

- Reurink, A. and Garcia-Bernardo, J., 2020. Competing for capitals: the great fragmentation of the firm and varieties of FDI attraction profiles in the European Union. Review of International Political Economy, 1–34. doi: 10.1080/09692290.2020.1737564

- Rixen, T., 2013. Why reregulation after the crisis is feeble: shadow banking, offshore financial centers, and jurisdictional competition. Regulation & Governance, 7 (4), 435–59. doi: 10.1111/rego.12024

- Seabrooke, L. and Wigan, D., 2014. Global wealth chains in the international political economy. Review of International Political Economy, 21 (1), 257–63. doi: 10.1080/09692290.2013.872691

- Seabrooke, L. and Wigan, D., 2017. The governance of global wealth chains. Review of International Political Economy, 24 (1), 1–29. doi: 10.1080/09692290.2016.1268189

- Sikka, P. and Mitchell, A.V., 2011. The pin-stripe mafia: how accountancy firms destroy societies. Basildon: Association for Accountancy & Business Affairs.

- Sikka, P. and Willmott, H., 1995. The power of “independence”: defending and extending the jurisdiction of accounting in the United Kingdom. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 20 (6), 547–81. doi: 10.1016/0361-3682(94)00027-S

- Sikka, P. and Willmott, H., 2013. The tax avoidance industry: accountancy firms on the make. Critical Perspectives on International Business, 9 (4), 415–43. doi: 10.1108/cpoib-06-2013-0019

- Stenger, S., 2017. Au cœur des cabinets d’audit et de conseil. Paris: Puf.

- Strange, S., 1996. The retreat of the state: the diffusion of power in the world economy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Suddaby, R., Cooper, D.J., and Greenwood, R., 2007. Transnational regulation of professional services: governance dynamics of field level organizational change. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 32 (4-5), 333–62. doi: 10.1016/j.aos.2006.08.002

- Teck-Heang, L.E.E. and Ali, A.M., 2008. The evolution of auditing: an analysis of the historical development. Journal of Modern Accounting and Auditing, 4 (12), 1.

- Tørsløv, T.R., Wier, L.S., and Zucman, G., 2018. The missing profits of nations. Cambridge: National Bureau of Economic Research. (No. w24701).

- UK House of Commons, 2013. Tax avoidance: the role of large accountancy firms (HL 2012–2013). London: The Stationery Office.

- Unctad, 2016. World investment report.

- Von Nordenflycht, A., 2010. What is a professional service firm? Toward a theory and taxonomy of knowledge-intensive firms. Academy of Management Review, 35 (1), 155–74.

- Wagener, T. and Watrin, C., 2014. The relevance of complex group structures for income shifting and investors’ valuation of tax avoidance. Working paper, University of Munster.

- Websites

- Wójcik, D., 2013. Where governance fails: advanced business services and the offshore world. Progress in Human Geography, 37 (3), 330–47. doi: 10.1177/0309132512460904