ABSTRACT

In the aftermath of recent populist upheavals in Europe, nationalist economic policies challenge the overly positive view on economic integration and the reduction of trade barriers established by standard economic theory. For quite a long time the great majority of economists supported trade liberalisation policies, at least those actively engaged in policy advice or public debates. In this paper, we examine the elite economics discourse on trade policies during the last 20 years regarding specific characteristics of authors, affiliations, citation patterns, the overall attitude towards trade, as well as the methodological approach applied in these papers. Our analysis yields the following results: First, the hierarchical structure of economics also manifests in the debate about trade. Second, while we found some indications of a shift towards more empirically oriented work, quite often empirical data is solely used to calibrate models rather than to challenge potentially biased theoretical assumptions. Third, top economic discourses on trade are predominantly characterised by a normative bias in favour of trade-liberalisation-policies. Forth, we found that other-than-economic impacts and implications of trade policies (political, social and cultural as well as environmental issues) to a great extent either remain unmentioned or are rationalised by means of pure economic criteria.

It has long been an unspoken rule of public engagement for economists that they should champion trade and not dwell too much on the fine print. (Rodrik Citation2018)

Introduction

In the course of recent populist upheavals, it has become obvious that trade policy as well as its political and social consequences and its impact on the world economy are controversial issues. Although trade liberalisation so far has been on the agenda of trade policy agreements during the neoliberal era in the last decades, there remain serious doubts among active policy-makers regarding the benefits of trade liberalisation policies. Whereas the strongest and most longstanding criticism of trade liberalisation comes from a (critical) developmental perspective, recently the most powerful nation in the world signalised its willingness to restrict its free-trade policy to protect the U.S. economy particularly from cheap Chinese imports. The new opponents of free-trade argue in favour of trade-barriers to protect (US) economic interests against ‘unfair’ treatment. The proponents of trade liberalisation policies in turn emphasise a win-win situation that supposedly arises from trade liberalisation as well as the inefficiency and overall welfare losses linked to protectionism. While this debate is strongly driven by political (and ideological) interests, our paper aims to explore the current debate in economic science. What is the current state of economic theory and research regarding the politically contested issue of trade policies? What kind of arguments are brought forward in favour of trade liberalisation and to what extent are negative consequences (social, political and environmental impacts) of trade liberalisation addressed? To what extent can we see an ‘empirical turn’ during the last 20 years? Furthermore, who are the dominant actors and institutions in elite economics trade debates and are there any indications for shifts in the debate in the course of the last two decades?

To answer these questions we analyse trade-related research articles published in the ‘top-five’ journals in economics (Card and DellaVigna Citation2013, Heckman and Moktan Citation2020) as well as highly cited articles published in other outlets. In doing so we follow a two-fold methodological approach: In a first step we apply bibliometric methods to inspect the overall structure of this debate regarding authorships, affiliations and cited references. In a second step, we conduct a quantitative and qualitative text analysis of the abstracts and partly the whole papers to examine the overall evaluation of trade and the methodology applied in the papers. Furthermore, we also inspect whether and to what extent economic, political, social and environmental implications of trade are being addressed in the papers. Hence, we will be able to develop a better understanding of how trade and implications of trade policies are referenced in the economics elite debate and show whether these are reflecting current political debates. Furthermore, we also aim to sketch recent trends by highlighting the relative importance of different impacts and implications as well as the overall normative evaluation of trade liberalisation policies over time. The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. Section 2 offers an overview of the economic trade debate and the specific role of ‘top-five’ journals in economics. In doing so, we aim to provide a rationale for analysing trade-related research in these specific outlets. In section 3 we introduce our twofold analytical framework. In section 4 we discuss the main results of our empirical analysis comprising descriptive statistics and a thematic analysis of the elite economics trade debate in our sample. Section 5 offers a summary of our main results and some concluding remarks.

Trade Debates in Top Economic Journals

On Trade Debate(S) in the Economics Profession

Issues of free trade and related policies are heatedly debated in the public and among politicians of all stripes. Against this background, current IPE debates revolve around topics such as the multifaceted impacts of non-trade-issues in trade agreements (e.g. Lechner Citation2016, Haggart Citation2017) or the impact of cultural (Skonieczny Citation2018, Siles-Brügge Citation2019) as well as country-specific (institutional) peculiarities (Maher Citation2015, Solís and Katada Citation2015, Weatherall Citation2015). In contrast to these debates, economists engaging in political debates on trade quite often seem to speak with one voice (Rodrik Citation2018). For instance, Alan Blinder – presumably one of the most publicly visible U.S. economists – is quoted in the Wall Street Journal with the statement: ‘Like 99 per cent of economists since the days of Adam Smith, I am a free trader down to my toes’ (Wessel and Davis Citation2007). Declaration like this lead Wilkinson (Citation2017, p. 36) to conclude that ‘we should bear in mind that even the best (…) accounts of the genesis of multilateral trade offers a partisan narrative’.

On the level of academic economics, however, the debate is more controversial: On the one hand, there is the longstanding but largely marginalised camp of critical voices originating from economic heterodoxy which includes scholars stressing negative effects of trade from social (Kapeller et al. Citation2016, Crouch Citation2018), developmental (Shaikh Citation2007, Chang Citation2009, Aroche Reyes and Ugarteche Galarza Citation2018) or environmental perspectives (Newell Citation2012, Krausmann and Langthaler Citation2019). On the other hand, there is the longstanding tradition in mainstream economists to mainly argue in favour of free trade and related policies (Irwin Citation2015, Krugman et al. Citation2015), notwithstanding the existence of theoretical results that indicate potentially negative consequences of increasing integration (e.g. Stolper and Samuelson Citation1941, Egger and Kreickemeier Citation2012).

In a review of economists’ role in public debates on free-trade Driskill (Citation2012) deconstructs the main arguments posed by ‘free-trade-advocates’ and thus criticises short-sight reference to the Pareto criterion in international trade and the still dominant heuristic of Ricardo’s theory of comparative advantages. In doing so, he claims that economists should be ‘forthright about the epistemological basis of their policy advocacy of free trade’ (Driskill Citation2012, p. 28).

However, as recent studies on the public policy views of prominent economists showed that the support for trade liberalisation to increase potential economic welfare is a rather consensus position among economists (e.g Gordon and Dahl Citation2013, Beyer and Puehringer Citation2019). Hence only about 5 per cent of the respondents of a survey among economists disagreed with the statement that ‘tariffs and import quotas usually reduce general welfare’ (Fuller and Geide-Stevenson Citation2014, p. 134). While this negative stance against tariffs is quite stable over the last three decades, there is also broad professional consensus among the members of the IGM economic expert panel that import tariffs are even more costly than they would have been 25 years ago (IGM Forum Citation2018).Footnote1 In a similar vein, Krugman et al. in their textbook on international trade assert:

Most economists, while acknowledging the effects of international trade on income distribution, believe it is more important to stress the overall potential gains from trade than the possible losses to some groups in a country. (Krugman et al. Citation2015, p. 100)

In short, had economists gone public with the caveats, uncertainties, and skepticism of the seminar room, they might have become better defenders of the world economy. Unfortunately, their zeal to defend trade from its enemies has backfired. If the demagogues making nonsensical claims about trade are now getting a hearing—and actually winning power—it is trade’s academic boosters who deserve at least part of the blame. (Rodrik Citation2018, p. xii)

As Rodrik further argues, when celebrating professional consensus economists make two central errors: errors of omission prevent economists from seeing the blind spots emanating from, e.g. a one-sided focus on trade models which assume away real-world complications. Errors of commission then result in a next step by administering policies which can be derived from such models.Footnote3 While the latter clearly relates to the public engagement of economists (policy advise), the former (errors of omission) rather seem to happen within the discipline. So, if Rodrik’s argument holds, the observed public one-sidedness of the trade debate held by economists is to some extent reflecting an internal one-sidedness of the debate, which is rooted deeply in the discipline.

Nevertheless, it should be stressed that, depending on the audience they aim to address, economists may take different rhetorical postures Goodwin (Citation1989): They may act as philosophers in academic debates, where they aim to persuade their counterparts with a rather technical language. They may also act as priests, when they aim to convince politicians of policy implications of economic theories. Finally, economists may also act as hired guns when they make use of their academic prestige to defend the interest of a specific group. Drawing on Goodwin’s classification, in this paper we are not focusing on the political and societal impact of economists and economic knowledgeFootnote4 but aim to develop a better understanding of common narratives in the philosopher’s discourse of economists. However, these three postures are often interrelated and individual economists act in several roles at the same time (see e.g. Mata and Medema Citation2013, Hirschman and Berman Citation2014, Maesse et al. Citation2020). Prestige in the philosopher’s discourse quite often yet enable economists to be influential ‘priests’ (see also the next section). This way, we argue that economic knowledge developed in academic discourse, offers common core narratives or framings for economists, when talking to a non-academic audience (Reay Citation2012, Wilkinson Citation2017). Thus, by focusing on the elite debate in economics, we do not only aim to empirically clarify the extent of an internal academic one-sidedness but also aim to analyse a strong foundation for economists’ discursive heterogeneity.

On the Institutional Peculiarities of Economics: The Power of the ‘Top-Five’

Compared to other social sciences, modern (mainstream) economics shows greater signs of stratification among various dimensions: For instance, in the context of women and ethnic minority groups (Bayer and Rouse Citation2016), editor- and authorships in top-journals (Hodgson and Rothman Citation1999), the marginalisation of alternative theoretical, ‘heterodox’ approaches (Dobusch and Kapeller Citation2009, Lee and Elsner Citation2011), or the recruitment of officials in academic associations (Fourcade et al. Citation2015), economics is coined by stark internal differentiations and hierarchies.

An archetypical example, where this stratification in particular has crystallised, are the disciplines most prominent outlets, the so-called ‘top-five’ in economics (Card and DellaVigna Citation2013): For decades now, the American Economic Review, Journal of Political Economy, Quarterly Journal of Economics, Econometrica, and Review of Economic Studies serve as a powerful proxy for scientific quality and reputation within the discipline. Due to its popularity and gate-keeping power, these five outlets significantly influence tenure decisions at top economics departments (Heckman and Moktan Citation2020). Seen from a scientometric perspective, the ‘top-five’ are responsible for a remarkable amount of concentration. For instance, in analysing a large-scale sample of publications in economics, Gloetzl and Aigner (Citation2019) found, that the ‘top-five’ account for nearly 30 per cent of all citations within the economics discipline. Moreover, almost 60 per cent of the 1000 most-cited articles are published in ‘top-five’ journals (see also Laband (Citation2013)). It is also remarkable, that – measured in terms of cited references – the discourse within the ‘top-five’ journals is also highly concentrated: On average, one out of four citations made in a ‘top-five’ journal either stem from the same journal (self-citation) or from its four ‘best buddies’ (Aistleitner et al. Citation2019).

In sum, this evidence on the ‘superiority of economists’ (Fourcade et al. Citation2015) in both institutional and scientometric terms strongly suggests, that economic research published in the ‘top-five’ captures significant parts of the discipline’s elite discourse. This research gains not only disproportionate high attention within the discipline (see, Arrow et al. (Citation2011) for instance).Furthermore, a bibliographic analysis reveals a strong relationship between economists’ public engagement in policy-making and publishing in these outlets in the U.S.: On average, one out of five journal articles (21.7 per cent) authored by members of the Council of Economic Advisers (CEA) and the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) are published in a ‘top-five’ journal.Footnote5 This indicates that, while ‘[e]conomists do not, however, often have the deciding voice in economic policy, especially when conflicting interests are at stake’ (Krugman et al. Citation2015, p. 100), economic research published in these outlets may still be of significant relevance for the overall policy-making process.

Methodology and Data

Our analysis of the debate in top economic journals on trade and trade policies in this paper is based on a mixed-method approach combining quantitative (bibliographic, textual and citation analysis) and qualitative methods (qualitative content analysis). Due to the typically very technical language of economic papers we decided to base our two-level analysis of the trade debate in economic-elite discourse mainly on the abstracts of the papers.Footnote6 However, we used the full texts of the papers for the classification of paper types and in cases of disagreement on the coding of papers.Footnote7 Although this approach obviously reduces our text corpus, we argue that (extended) abstracts are a reliable source for our analyses for at least three reasons: First, the definition of a scientific abstract implies that it should clarify (i) why the research was conducted, (ii) what the paper is about and what are the main conclusions of the research and (iii), how and based on which specific methodology the authors arrived at their conclusions. Thus an abstract aims to call attention to the most important information of a paper (Ermakova et al. Citation2018). Second, abstracts serve as essential screening devices and are in fact the section of a paper, which is read by a broader audience (Bondi Citation2014). Third, due to its role of communicating research results to a an extended disciplinary community within the economics profession and beyond (Sala Citation2014), abstracts ought to be and in most cases are written in rather plain language, which in turn enables us to apply qualitative analytical methods in the first place.

In order to obtain representative data of the elite discourse in economics related to trade, we draw our sample from two different data sources. Each sub-sample is based on different data bases and selection criteria. The first sample is compiled from the EconLit database and is restricted to papers published in the ‘top-five’ journals in economics (hereafter TOP5) between 1997 and 2017. We selected those papers which contain at least one JEL code listed in EconLit that relates to trade in a broad sense.Footnote8

In this paper, we focus on economic research addressing economic, political, social, environmental or cultural impacts of trade in general or trade-specific policies (e.g. trade agreements, tariffs) from a theoretical or empirical perspective.Footnote9 Thus, in a next step we manually excluded those papers containing JEL codes related to trade but engage with topics other than international trade such as financial integration or monetary policy. We also excluded paper types such as notes, short comments, replies, corrigenda and errata since we found that such papers did not contain sufficient data for our analysis.

The second sample is obtained from the Web of Science database and draws on a set of 1000 top cited papers (by the end of 2017) published between 1957 and 2017 (hereafter TOPCITED). These papers include ‘trade’ either in the title, the abstract (if available) or in the keywords (if available). In order to capture the more recent debate on economic integration we restricted our TOPCITED sample to papers published in the TOP5 period (1997–2017) instead of calculating the annual citation rate per year (total citations divided by years since publication).Footnote10 After screening for papers not relevant to international trade (e.g. ‘trade(-)off’, ‘trade(ers)’ and as described above), we selected the 100 most cited papers.

In sum, both sub-samples together consist of 422 unique papers dealing with issues related to trade and thus represent a comprehensive picture of the current trade debate in (mainstream) economics (see Appendix A2 for a detailed list). provides an overview and summary statistics of the total sample.

Table 1. Sample summary statistics.

Results & Discussion

The results section is divided into three parts and basically mirrors our mixed-methods approach. The first part provides some descriptive statistics on the properties of our sample with regard to the distributions of authors and affiliations involved in the elite debate. In the second part we take a closer look at the methodology applied in the papers. In doing so, we contribute to the debate whether and to what extent there can be identified an ‘empirical’ (Angrist et al. Citation2017) or an ‘applied’ (Backhouse and Cherrier Citation2014) turn in economics during the last two decades. The third part illustrates our results on the overall trade discourse and divides into three sub-sections: a quantitative analysis of word frequencies and cited references, qualitative coding of abstracts according to their reference to trade implications, and the explicit and implicit normative evaluations of trade.

Authors and Affiliations

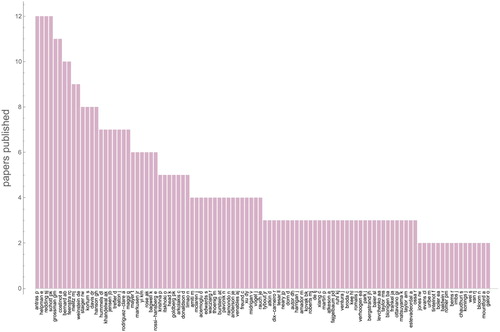

Analysing the authors and their institutional affiliations obtained from our sample strongly confirms previous results on the high stratification and concentration of the discipline in general (see above). In our sample, we identified 873 authorships distributed across 462 unique authors. shows the distribution across the 100 most common authors. Measured in terms of publication output, the top-30 authors account for 240 (27.5 per cent) of total authorships. In turn, more than the half (51 per cent) of all authorships is spread across 378 authors with only one or two publications.

Figure 1. The ‘top 100’ authors in the elite trade debate (unweighted authorships). Authors’ own calculation based on data from EconLit database.

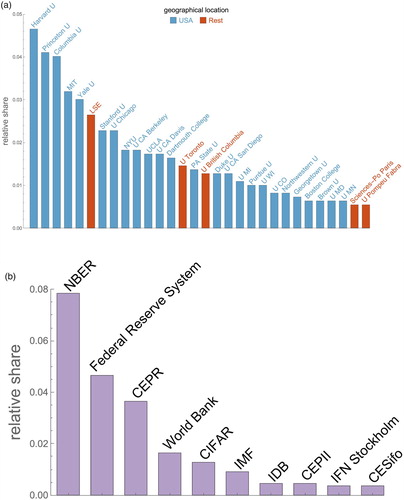

The levels of concentration are similar high when looking at the institutional composition. In our analysis, we distinguished between university (a) and non-university affiliations (b). The top-30 university affiliations account for the half (50.7 per cent) of the 1096 affiliations listed in our overall sample. Rather unsurprisingly, the top institutions are also highly renowned universities such as five of the eight ‘Ivy League’-universitiesFootnote11 the MIT, the University of Chicago or the LSE. Moreover, a very high degree of geographical concentration becomes visible. 25 of the top-30 institutions are from the US, which also means that the elite scientific discourse in trade is dominated by US-based (elite) institutions. Also remarkable is the high share of a small group of non-university affiliations (b). Five out of the top-10 institutions listed are economic (policy) think tanks or banking institutions.

Figure 2. (a) The ‘top 30’ university affiliations in the elite trade debate. Authors’ own calculation based on data from EconLit database. (b) The ‘top 10’ non-university affiliations in the elite trade debate. Authors’ own calculation based on data from EconLit database.

The National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) is ranked first place (and is, almost always, listed as a secondary affiliation). Given its reputation as a platform in disseminating ‘[economic] research findings among academics, public policy makers, and business professionals’ (NBER Citation2019) the high number of NBER affiliations indicate that the elite discourse on trade is (or at least should be) able to spill over into the sphere of economic policy makers. The same holds also for the Federal Reserve System (ranked second place), followed by the UK-based non-partisan Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR).Footnote12 Taken together, these institutions either aim to provide policy-relevant research and information for the public with regard to major policy debates or are actively engaged in economic policy-making. Thus, economists affiliated to these institutions presumably have special opportunities to influence public policy debates (Hirschman and Berman Citation2014, Lepers Citation2018).

Methodological Approaches

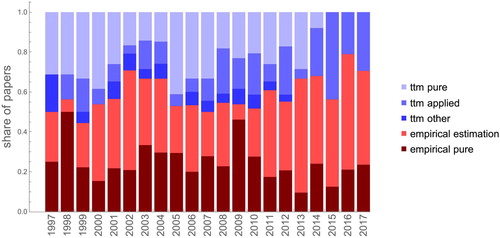

In a second step, we analysed the principal methodological design applied in addressing issues of trade. Therefore, we analysed the full papers in our sample and classified them according to two main categories of paper types: (1) empirical studies and (2) theoretical/technical/methodological (ttm) studies. Overall, our classification scheme assumes a continuum of methodological approaches from pure theoretical models with far-reaching assumptions to pure empirical papers, directly referring to real economic data and phenomena.

The empirical studies are classified into two sub-categories: papers that aim to explore empirical relationships by focusing on real-world data in the first place (and then e.g. use statistical analytical tools) labelled as ‘empirical pure’ (1a); and papers that introduce an (empirical) economic model and then use real-world data to estimate the model parameters, labelled as ‘model estimation’ (1b). The ttm studies can be classified into two sub-categories: papers that introduce (theoretical) economic models and then use real-world data to calibrate and/or simulate the performance of these models, labelled as ‘ttm applied’ (2a) and papers that solely focus on the theoretical analysis of economic models (including the use of fictitious data), labelled as ‘ttm pure’ (2b). Finally, all, remaining papers which cannot be assigned to either of the other sub-categories such as trade-related meta-studies or review papers are classified as ‘other’.

shows some revealing developments over time. First, we found an increase of empirical papers and conversely a decline of papers addressing trade-issues from a pure theoretical point. This trend is in line with a general ‘empirical turn’ (Angrist et al. Citation2017, Angrist et al. Citation2020) in economics and also aligns well with our word frequency analysis presented below (see ). Second, the economics trade discourse seems to have been undergone an even stronger ‘empirical turn’ compared to the overall economics debate (Hamermesh Citation2013), regarding the strong decline of pure theoretical papers in the last years. Third, however, among the empirical papers the share of ‘pure empirical papers’ is also decreasing over time. Contrary, the share of ‘ttm applied’ papers and to a lesser extent also the share of papers that focus on the ‘empirical estimation’ of trade models is increasing particularly during the last ten years.

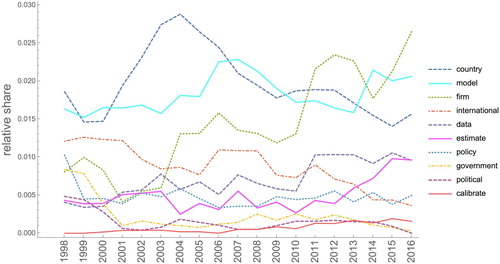

Figure 4. Word frequency development in the elite-economics discourse: a sample of selected lemmatised words. Three-years moving average.

This way, we conclude that much of the ‘empirical turn’ is not really a shift away from the application of theoretical trade models. Rather we observe a shift in the way how these models relate to empirical data (‘empirical estimation’ vs. ‘ttm applied’) with nontrivial implications in terms of both methodology and epistemology. While, model estimation primarily aims to test how well a particular model describes the data, model calibration, in turn, a priori assumes the validity of a given model (either due to its theoretical foundation and/or widespread use in the literature) (Dawkins et al. Citation2008). Consequently, if the data does not fit the model then its parameters (and not the model itself) need adjustment. Within such an approach, calibrating a model to the data – even in an optimal way – does not always imply an overall good fit. In particular, calibration alone may simply not suffice in providing explanations of the underlying mechanisms at work (Gräbner Citation2018).

Whether to apply estimation or calibration (or a combination of both) is controversially discussed even in economic mainstream (for a popular account see also Krugman Citation2011). The rationale behind calibration is that policy-relevant (and thus complex) models often preclude estimation or testing: ‘[p]olicy and other issues of the day cannot wait until the theoretical models needed to analyse them are well developed in the literature’ (Dawkins et al. Citation2008, p. 3657). However, it is precisely this fact which may be used to argue against calibration (see also Hoover Citation1995): is it acceptable to derive policy implications from models which are analytically solved instead of undergoing rigorous statistical testing? In any case, model calibration implies conducting an empirically-guided analysis which is, however, substantially limited by a particular theory.

To sum up, our analysis of the methodological approach indicates an ‘applied turn’ (Backhouse and Cherrier Citation2014, Backhouse and Cherrier Citation2017) rather than a real ‘empirical turn’, in the sense of an opening up to the empirical investigation of real economic phenomena in the economic discourse on trade.

The Structure of the Trade Debate

Following our methodological approach of a two-level analysis of the trade debate in economics elite discourse we first conducted a thematic analysis. For this purpose, we applied a mixed-method approach combining quantitative and qualitative methods. To get a first thematic overview of the debate, we looked at lemmatised word frequencies using the lemmatise analysis tool of MAXQDA. The three most important tokens in the overall trade debate are ‘countr*’, ‘model*’ and ‘firm*’. The result of this overall token analysis is unsurprising, given the fact that we analyse an economic debate on trade in goods and services. Nevertheless, we also found some evidence for changes in the trade debate during the last 20 years (see ), which also allows us to draw some careful conclusions about the overall structure of the debate. First, the token ‘firm’ increases over time and is by far the most mentioned term in the last years. In contrast the tokens ‘countr*’ and even more pronounced ‘international*’, typically stronger associated with macroeconomic approaches, decline over times. Thus, the overall token analysis indicates a trend towards microeconomic analysis in the economic trade literature during the last 20 years. Second, the steady increase of the term ‘data’ (and on a lower overall level also the tokens ‘estimate*’ and ‘calibrate*’) provides further evidence for a stronger empirical orientation in economics, albeit as we have shown this stronger empirical orientation rather signifies an ‘applied turn’. Third, social and environmental issues are hardly ever mentioned in the debate, while the relative importance of policy issues (tokens ‘polic*’, ‘political’ and ‘government*’) is declining.

In sum, our analysis of word frequencies indicates that the elite debate on trade (policy) increasingly shifts towards a ‘data’-driven albeit mainly economic analysis of the individual ‘firm’, a research agenda that aligns well with the prevailing neoliberal (trade) model: the competitive integration of firms into free and globalised markets (Shaikh Citation2007, Chang Citation2009, Crouch Citation2018).

Another quantitative exercise we conduct, is analysing the composition of cited references in our sample. As already mentioned above, measured in terms of citation flows, the overall discourse in the ‘top-five’ journals is highly concentrated (Aistleitner et al. Citation2019, Heckman and Moktan Citation2020). Referring to their results, Aistleitner et al. (Citation2019) emphasise two different ways in which citation data may be interpreted: Either as an indicator for the quality of a publication (evaluative interpretation) or as a specific form of communication (cognitive interpretation). They conclude that, depending on the interpretation, research published in the ‘top-five’ journals is either simply ‘superior’ because these outlets manage to concentrate high research quality (and thus receive many citations), or the discourse in these outlets is simply stronger self-contained and/or highly self-referential (as evidenced by receiving many citations).

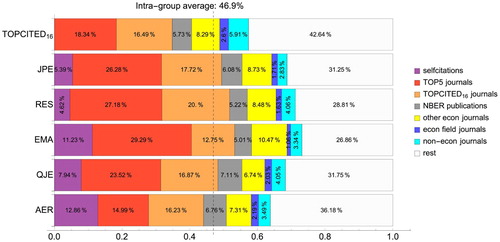

Given that both interpretations will eventually lead to different (research policy) implications, we therefore ask whether and to what extent this concentration within the ‘top-five’ journals is reflected in the particular debate on trade. Furthermore, we analyse the overall composition of cited journal references in our sample with regard to specific sub-fields in economics and other disciplines. The cited references data were obtained from Web of Science. We excluded books and monographies as well as unpublished material and working papers (with the notable exception of NBER literature). shows the results of these exercise by analysing the intra-group citation flows between the TOP5 journals in our sample plus the remaining 16 TOPCITED journals (treated as an aggregated journal (TOPCITED16)).

Figure 5. Citation networks in the elite trade debate. Authors’ own calculation based on data from Clarivate Analytics’ (Web of Science) database. Note: The category ‘rest’ includes non-journal references (monographs, book series), working papers, unpublished material and data sources.

In terms of (journal) citations, the discourse in the trade debate is highly concentrated: On average, almost half (46.9 per cent) of all citations remain within the same group of 21 (elite) journals. Furthermore, we found a substantial share of references to NBER publications (grey-shaded bars in ). In contrast, we found a relatively minor share of references made to journals outside the discipline as well as specific ‘field’ journals (see Appendix C for a detailed list). Given the possibility of two competing interpretations to citation data, as outlined above, one can conclude, that the high level of concentration provides evidence either (a) for the excellent quality (evaluative interpretation) or (b) for the high degree of self-referentiality (cognitive interpretation) of this debate.

However, at least in the case of the specific (elite) discourse on trade, we challenge Angrist et al. (Citation2020), who argue that the increase of empirical papers also leads to a higher receptivity to findings from other social sciences.

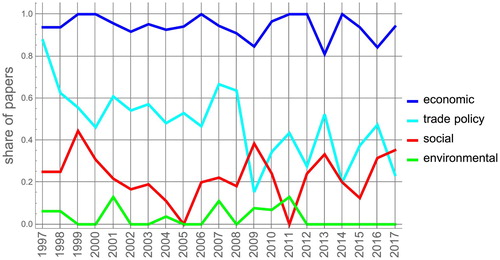

Much of the critical literature on trade liberalisation and globalisation particularly raises social and ecological concerns on an increase in trade in goods and to a lesser extent services. Economists, in turn are often blamed to ignore other-than-economic consequences of globalisation and solely focus on the economic gains of trade (Rodrik Citation2018). Hence, we secondly also coded the papers in our sample according to whether the authors refer to different levels of implications of trade. In doing so, we distinguished between the four codes ‘economic’, ‘policy’, ‘social and cultural’ as well as ‘environmental’ implications. Unsurprisingly we found that nearly all papers (94.3 per cent) even in their abstracts referred to the economic impacts and implications of trade. The code ‘economic’ implications includes various topics such as relative price developments, changes in exports and imports, economic efficiency and productivity of firms and sectors, changes in market structures or transport costs. The category ‘policy impact’ comprises tariffs, custom unions, international and bilateral trade agreements or references to issues such as policy institutions, liberalisation and protectionism, trade barriers or government interventions in general.

We found that quite often policy changes are modelled as quasi-natural experiments to examine a set of economic consequences of changes in openness to trade. This means that many papers interpret political decisions as exogenous shocks and thus do not assess the interplay between economic and political developments by deliberately ignoring the economic, social or political causes for a distinct decision or policy change. In a similar vein, many papers take an open economy perspective (OEP) when dealing with political developments or changes in the institutional structure of trade (e.g. Grossman and Helpman Citation2005). However, from a critical IPE perspective, the OEP paradigm has been criticised for its reductionist approach to structural power issues and its lack of engagement with international macro processes (Lake Citation2009, Oatley Citation2011, Citation2017).

Overall, about half of the papers (47.2 per cent) referred to policy impacts of trade, while the social and cultural (21.8 per cent) as well as environmental impacts of international economic integration (3.3 per cent) play a minor role in the economics elite discourse on trade .

Most of the papers, which address social and cultural impacts of trade are concerned with changes in employment or income, rising unemployment or the living- and working-conditions of (low-income) workers or workers in distinct countries or sectors. A few papers furthermore also address different implications for workers of different gender, ethnicity and/or cultural background.

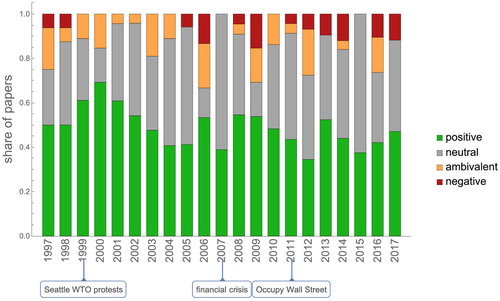

In a last step we took a closer look at the content of the papers in our sample and followed a two-fold approach. First, we examined the overall evaluation of trade in the abstracts and distinguished between the four categories ‘positive’, ‘negative’, ‘neutral’ and ‘ambivalent’, the latter being a mixed evaluation, where positive and negative consequences of trade are addressed.Footnote13 A positive evaluation of trade typically includes references to efficiency gains, welfare, productivity or product quality increases or the theory of comparative advantages of trade. Negative evaluations in turn stress issues such as increases in unemployment, negative distributional or environmental effects of trade increases. The category ‘neutral’ applies for papers without any kind of at least implicit normative evaluation of trade.

Considering the overall evaluation of trade in top economic journals discourse over the last 20 years we found that about half of the papers in our sample (48.1 per cent) primarily refer to positive implications of trade. In contrast, 4.7 per cent report mainly negative implications of trade, while 38.2 per cent take a rather neutral stance on this issue. Furthermore, 9.0 per cent are coded as ambivalent, as they report positive as well as negative implications of trade. Beside this general assessment of the issue of trade in the economics elite discourse, we furthermore examined changes in the evaluation of trade over the last 20 years. indicates a slight increase of rather critical contributions and a slight decrease of papers offering a primary positive perspective on trade. Interestingly, the period which experience a strong decrease of positive evaluations (2001–2004) could be interpreted as a reaction to the anti-globalisation protests around the WTO ministerial conference in Seattle in 1999 (‘the battle of Seattle’) and the G8 Summit in Genoa in 2001.

Conclusion

Research in IPE and related fields often stress the influential role of political institutions such as NGOs (e.g. Holmes Citation2011, Nega and Schneider Citation2014), IGOs (e.g. Mortensen Citation2012, Farnsworth and Irving Citation2018) or domestic policy elites (e.g. Kaltenthaler and Mora Citation2002, Brennan Citation2013) in deepening international economic integration as part of a neoliberal agenda. Yet, the transmission of economic knowledge to public policy is very complex and closely related to specific formal governance structures of specific policy institutions (e.g. Chwieroth Citation2010, Wilkinson Citation2017). With this paper, however, we point out another important aspect relevant in shaping the public opinion on international trade and trade liberalisation: the scientific debate on trade within (mainstream) economics itself and, in particular, the research published in its most prestigious outlets.

More specifically, we combine quantitative and qualitative methods in order to examine the specific characteristics of the debate in high impact papers dealing with trade and trade-policy issues.

To sum up, we characterise the trade (policy) discourse in top economics journals by means of three different aspects: the institutional origin, the methodological orientation and the topical structure of the discourse. Regarding the institutional origin, our results correspond with recent literature claiming a strong degree of hierarchy and concentration in terms of academic institutions, citations and journals. In a nutshell, the economic elite trade debate is significantly dominated by a small group of (predominantly male) economists mostly affiliated with a small group of US-based elite universities and the NBER. Regarding the methodological orientation of the debate, we found that the ‘empirical turn’ in the discipline remains limited to a modelling context. Thus, real-world data is rather used to develop, estimate and in recent years particularly calibrate economic trade models. This way, what we observe should be rather dubbed as ‘applied turn’, informed by the availability of new data and more sophisticated analytical tools than by broader (interdisciplinary) theoretical and empirical findings.

And finally, the topical structure of the discourse reveals a remarkable lack of diversity which manifests in several ways. First, we found a considerable ignorance towards other-than-economic consequences and implications of trade and trade liberalisation. Furthermore, a great majority of papers lack any critical engagement with the respective political or social contexts and causes of trade policies (see also: Watson Citation2017). The argument of a predominance of a rather narrow, pure economic approach to trade is also supported by the fact that only 4 per cent of all citations in our sample of elite economic discourse goes to non-economic journals.

Second, concerning the qualitative results of our paper, we found a clear bias towards a positive evaluation of trade or trade-enhancing policies in our sample (for a more detailed analysis see also Aistleitner and Puehringer Citation2020) . This in turn, suggests that the predominant trade narrative in economic elite discourse constitutes a fairly lopsided support for trade liberalisation.

However, our results could also point toward a self-selection effect within the profession: Economists could be aware of the fact, that when engaging in the academic elite discourse on trade, they are obliged to follow the distinct rules of this debate. In this case, we would provide empirical support for the existence of a rule, that one should not be too critical when it comes to the evaluation of trade. Regardless of whether there is a self-selection effect or not, given the dominant role of the ‘top-five’ in economics, we argue that its lopsided stance towards trade paves the way for further institutionalising the pro-trade liberalisation bias within the economics profession.

It remains open however, whether this bias is caused by an explicit focus on gains from trade or simply by what was termed a theory-ladenness of observation and measurement (Kuhn Citation1970) in economic theorising on trade. Yet, a broader conceptualisation of the complex implications and impacts of trade liberalisation would not only lead to a comprehensive understanding of this issue, it would also result in a more differentiated view on economic integration. This, in turn, would also improve the recently tarnished reputation of economic expertise.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interests

Appendix_C.docx

Download MS Word (14.5 KB)Appendix_B.docx

Download MS Word (26.2 KB)Appendix_A-rev.docx

Download MS Word (69.6 KB)Acknowledgements

We want to thank Claudius Gräbner and Jakob Kapeller as well as the participants of the 2nd Vienna Conference on Pluralism in Economics in April 2019 for their comments on an earlier version of this paper as well as Ernest Aigner, who has provided us with bibliometric data. We also want to thank Dominik Kronberger for excellent research assistance.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Matthias Aistleitner

Matthias Aistleitner is a research associate and doctoral student at the Institute for Comprehensive Analysis of the Economy. His main research interests include path-dependency effects in mainstream economics, Political Economy and Social Studies of Economics.

Stephan Puehringer

Stephan Puehringer currently works at the Institute for Comprehensive Analysis of the Economy (ICAE) at the University of Linz. His main research interests include Political Economy, the Performativity of Economic Thought and Economic Teaching as well as Power structures in Economics. In his work he is applying Discourse and Social Network Analysis of economics and economists as well as bibliometric methods and is hence contributing to the field of Social Studies of Economics.

Notes

1 In fact 94% of the IGM forum at the Chicago Booth School agreed or strongly agreed with the following statement: ‘Trade Disruptions: Because global supply chains are more important now, import tariffs are likely substantially more costly than they would have been 25 years ago’. While 6% were uncertain, nobody disagreed.

2 Newbery and Stiglitz (Citation1984) represent a noteworthy exception of an earlier balanced ‘mainstream’ position on the gains and challenges of trade liberalisation.

3 The reliance on empirical models in the field of trade policies could even be more concerning, since Linsi and Mügge (Citation2019) have recently shown that official trade statistics are much less accurate then often assumed in research as well as public debates.

4 In the field of trade policy see e.g. Chwieroth (Citation2010) on the IMF or Wilkinson (Citation2014) on the WTO.

5 We analysed the publication history of 65 CBO members (2001–2019) and 30 CEA members (since 2000) listed in the EconLit database (in total 4689 journal articles). Correcting for overlapping members, we found that only 21% of the members have no publication in ‘top-five’ journals (within the CEA members only two have no publication). The average value is 11.3 ‘top-five’ publications per author, the median value is 8.5 publications.

6 It should be noted, that about 6% of the papers which enter our final analysis do not contain an abstract (see next section). In this case we compiled ‘pseudo-abstracts’ and analysed those first paragraphs (and if necessary, the conclusion) of a paper until we were able answer the three questions which define an abstract discussed above (i-iii).

7 Overall the inter-coder-reliability for the coding of overall trade evaluation, trade implications and paper type ranged around 95%.

8 For a detailed list of the relevant JEL Codes see Appendix A1.

9 Recently, Lechner (Citation2016) stressed the increasing importance of non-trade issues (NTI) in bilateral trade agreements as well as the huge variation in terms of precision, obligation and delegation of these issues. However, in the economics debate NTIs are mainly only referred to as non-tariff trade barriers.

10 However, in either case the problem of missing upcoming top cited papers remains. Since citations also need time to accumulate, in our research setting we are not able to screen for potential high-impact papers published towards the end of the period.

11 These are Princeton, Harvard, Columbia, Yale and Dartmouth.

12 It is important to note, that in the case of multiple affiliations, EconLit does not always lists all affiliations of an author (as listed in the paper). Wherever we found such inconsistencies, we complemented this information manually.

13 Although we basically used the abstracts for the coding of the papers, we included the full papers in cases where we could not decide about a coding on the basis of an abstract; in particular when the abstracts were very short. To increase reliability, we both classified the papers separately and developed a common coding system after an initial pre-test, where we discussed uncertain cases. The overall inter-coder-reliability ranged between 95% and 99% for different categories. In cases of different classification of overall trade evaluation, we assigned the respective papers to the category ‘neutral’ or ‘ambivalent’, respectively.

References

- Aistleitner, M., and Puehringer, S., 2020. Exploring the trade (policy) narratives in economic elite discourse. SPACE Working Paper Series, No. 1.

- Aistleitner, M., Kapeller, J., and Steinerberger, S., 2019. Citation patterns in economics and beyond. Science in Context, 32 (4), 361–380.

- Angrist, J., et al., 2017. Economic research evolves: fields and styles. American Economic Review, 107 (5), 293–297.

- Angrist, J., et al., 2020. Inside job or deep impact? Extramural citations and the influence of economic scholarship. Journal of Economic Literature, 58 (1), 3–52.

- Aroche Reyes, F., and Ugarteche Galarza, O., 2018. The death of development theory: from Friedrich von Hayek to the Washington consensus. Journal of Post Keynesian Economics, 41 (4), 509–525.

- Arrow, K.J., et al., 2011. 100 years of the “American economic Review": the top 20 articles. American Economic Review, 101 (1), 1–8.

- Backhouse, R. and Cherrier, B., 2014. Becoming applied: the transformation of economics after 1970. The Center for the History of Political Economy Working Paper Series, No. 2014-15. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2526274

- Backhouse, R. and Cherrier, B., 2017. The age of the applied economist. History of Political Economy, 49 (Supplement), 1–33.

- Bayer, A., and Rouse, C.E., 2016. Diversity in the economics profession: a new attack on an old problem. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 30 (4), 221–242.

- Beyer, K., and Puehringer, S., 2019. Divided we stand? Professional consensus and political conflict in academic economics. ICAE Working Paper Series, No. 94.

- Bondi, M., 2014. Changing voices: authorial voice in abstracts. In: M. Bondi, and R. Lorés Sanz, ed. Abstracts in academic discourse: variation and change. Bern: Peter Lang, 243–270.

- Brennan, J., 2013. The power Underpinnings, and some distributional consequences, of trade and Investment liberalisation in Canada. New Political Economy, 18 (5), 715–747.

- Card, D. and DellaVigna, S., 2013. Nine facts about top journals in economics. Journal of Economic Literature, 51 (1), 144–161.

- Chang, H.-J., 2009. Bad samaritans: the myth of free trade and the secret history of capitalism. New York, NY: Bloomsbury Press.

- Chwieroth, J.M., 2010. Capital ideas: the IMF and the rise of financial liberalization. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Crouch, C., 2018. The globalization backlash. Newark: Polity Press.

- Dawkins, C., Srinivasan, T.N., and Whalley, J., 2008. Calibration. In: J.J. Heckman, ed. Handbook of econometrics. Amsterdam: Elsevier, 3653–3703.

- Dobusch, L., and Kapeller, J., 2009. Why is economics not an evolutionary science?: new answers to Veblen's old question. Journal of Economic Issues, 43 (4), 867–898.

- Driskill, R., 2012. Deconstructing the argument for free trade: a case study of the role of economists in policy debates. Economics and Philosophy, 28 (1), 1–30.

- Egger, H., and Kreickemeier, U., 2012. Fairness, trade, and inequality. Journal of International Economics, 86 (2), 184–196.

- Ermakova, L., et al., 2018. Is the abstract a Mere Teaser? Evaluating generosity of article abstracts in the environmental sciences. Frontiers in Research Metrics and Analytics, 3, 636.

- Farnsworth, K., and Irving, Z., 2018. Deciphering the international monetary fund’s (IMFs) position on austerity: incapacity, incoherence and instrumentality. Global Social Policy, 18 (2), 119–142.

- Fourcade, M., Ollion, E., and Algan, Y., 2015. The superiority of economists. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 29 (1), 89–114.

- Fuller, D., and Geide-Stevenson, D., 2014. Consensus among economists—an update. The Journal of Economic Education, 45 (2), 131–146.

- Gloetzl, F., and Aigner, E., 2019. Six dimensions of concentration in economics: evidence from a large-scale data Set. Science in Context, 32 (4), 381–410.

- Goodwin, C.D., 1989. The heterogeneity of the economists’ discourse: philosopher, priest, and hired gun. In: A. Klamer, ed. The consequences of economic rhetoric. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, 207–220.

- Gordon, R., and Dahl, G.B., 2013. Views among economists: professional consensus or point-counterpoint? American Economic Review, 103 (3), 629–635.

- Gräbner, C., 2018. How to relate models to reality? An epistemological framework for the validation and verification of computational models. Journal of Artificial Societies and Social Simulation, 21, 3.

- Grossman, G.M., and Helpman, E., 2005. A protectionist bias in majoritarian politics. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 120 (4), 1239–1282.

- Haggart, B., 2017. Incorporating the Study of Knowledge into the IPE Mainstream, or, When Does a Trade Agreement Stop Being a Trade Agreement? Journal of Information Policy, 7, 176-203.

- Hamermesh, D.S., 2013. Six decades of top economics publishing: who and how? Journal of Economic Literature, 51 (1), 162–172.

- Heckman, J.J. and Moktan, S., 2020. Publishing and promotion in economics: the tyranny of the top five. Journal of Economic Literature, 58 (2), 419–470.

- Hirschman, D., and Berman, E.P., 2014. Do economists make policies?: on the political effects of economics. Socio-Economic Review, 12 (4), 779–811.

- Hodgson, G.M., and Rothman, H., 1999. The editors and authors of economics journals: a case of institutional Oligopoly? The Economic Journal, 109 (453), 165–186.

- Holmes, G., 2011. Conservation's Friends in high places: neoliberalism, networks, and the transnational conservation elite. Global Environmental Politics, 11 (4), 1–21.

- Hoover, K., 1995. Facts and artifacts: calibration and the empirical assessment of real-business-cycle. Oxford Economic Papers, 47 (1), 24–44.

- IGM Forum. 2018. Trade disruptions [online]. Available from: http://www.igmchicago.org/surveys/trade-disruptions [Accessed 8 November 2019].

- Irwin, D.A., 2015. Free trade under fire. 4th ed. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Kaltenthaler, K., and Mora, F.O., 2002. Explaining Latin American economic integration: the case of Mercosur. Review of International Political Economy, 9 (1), 72–97.

- Kapeller, J., Schütz, B., and Tamesberger, D., 2016. From free to civilized trade: a European perspective. Review of Social Economy, 74 (3), 320–328.

- Krausmann, F., and Langthaler, E., 2019. Food regimes and their trade links: a socio-ecological perspective. Ecological Economics, 160, 87–95.

- Krugman, P. 2011. Calibration and all that (Wonkish). The New York Times [online], 19 Oct. Available from: https://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/10/18/calibration-and-all-that-wonkish/ [Accessed 29 July 2020].

- Krugman, P.R., Obstfeld, M., and Melitz, M.J., 2015. International trade: theory and policy. 10th ed. Boston: Pearson.

- Kuhn, T.S., 1970. The structure of scientific revolutions. 2nd ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Laband, D.N., 2013. On the use and abuse of economics journal rankings. The Economic Journal, 123 (570), F223–F254.

- Lake, D.A., 2009. Open economy politics: a critical review. The Review of International Organizations, 4 (3), 219–244.

- Lechner, L., 2016. The domestic battle over the design of non-trade issues in preferential trade agreements. Review of International Political Economy, 23 (5), 840–871.

- Lee, F.S., and Elsner, W., eds. 2011. Evaluating economic research in a contested discipline; rankings, pluralism, and the future of heterodox economics. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Lepers, E., 2018. The neutrality illusion: biased economics, biased training, and biased monetary policy testing the role of ideology on FOMC voting behaviour. New Political Economy, 23 (1), 105–127.

- Linsi, L., and Mügge, D.K., 2019. Globalization and the growing defects of international economic statistics. Review of International Political Economy, 26 (3), 361–383.

- Maesse, J., Puehringer, S., Rossier, T., and Benz, P., eds. 2020. Power and influence of economists: Contributions to the social studies of economics. London: Routledge.

- Maher, D., 2015. Rooted in violence: civil war, international trade and the expansion of Palm Oil in Colombia. New Political Economy, 20 (2), 299–330.

- Mata, T., and Medema, S.G., eds. 2013. The economist as public intellectual. Durham: Duke Univ. Press.

- Mortensen, J.L., 2012. Seeing like the WTO: numbers, frames and trade law. New Political Economy, 17 (1), 77–95.

- NBER. 2019. About [online]. Available from: https://www.nber.org/info.html [Accessed 13 May 2019].

- Nega, B., and Schneider, G., 2014. NGOs, the state, and development in Africa. Review of Social Economy, 72 (4), 485–503.

- Newbery, D.M.G., and Stiglitz, J.E., 1984. Pareto inferior trade. The Review of Economic Studies, 51 (1), 1.

- Newell, P., 2012. Globalization and the environment: capitalism, ecology & power. Cambridge: Polity.

- Oatley, T., 2011. The reductionist gamble: open economy politics in the global economy. International Organization, 65 (2), 311–341.

- Oatley, T., 2017. Open economy politics and trade policy. Review of International Political Economy, 24 (4), 699–717.

- Reay, M.J., 2012. The flexible unity of economics. American Journal of Sociology, 118 (1), 45–87.

- Rodrik, D., 2018. Straight talk on trade: ideas for a sane world economy. Princeton New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

- Sala, M., 2014. Research article abstracts as Domain-specific epistemological indicators. A corpus-based study. In: M. Bondi, and R. Lorés Sanz, ed. Abstracts in academic discourse: variation and change. Bern: Peter Lang, 199–220.

- Shaikh, A., ed. 2007. Globalization and the myths of free trade: history, theory, and empirical evidence. London: Routledge.

- Siles-Brügge, G., 2019. Bound by gravity or living in a ‘post geography trading world’? expert knowledge and affective spatial imaginaries in the construction of the uk’s post-brexit trade policy. New Political Economy, 24 (3), 422–439.

- Skonieczny, A., 2018. Trading with the enemy: narrative, identity and US trade politics. Review of International Political Economy, 25 (4), 441–462.

- Solís, M., and Katada, S.N., 2015. Unlikely pivotal states in competitive free trade agreement diffusion: the effect of Japan's trans-pacific partnership participation on Asia-pacific regional integration. New Political Economy, 20 (2), 155–177.

- Stiglitz, J.E., 2017. The overselling of globalization. Business Economics, 52 (3), 129–137.

- Stolper, W.F., and Samuelson, P.A., 1941. Protection and real wages. The Review of Economic Studies, 9 (1), 58–73.

- Watson, M., 2017. Historicising Ricardo’s comparative advantage theory, challenging the normative foundations of liberal international political economy. New Political Economy, 22 (3), 257–272.

- Weatherall, K., 2015. The Australia-US free trade agreement’s impact on Australia’s copyright trade policy. Australian Journal of International Affairs, 69 (5), 538–558.

- Wessel, D., and Davis, B. 2007. Pain from free trade spurs second thoughts. Wall Street Journal [online], 28 Mar, A1. Available from: https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB117500805386350446 [Accessed 28 November 2019].

- Wilkinson, R., 2014. What''s wrong with the WTO and how to fix it. Hoboken: Wiley.

- Wilkinson, R., 2017. Talking trade: common sense knowledge in the multilateral trade regime. In: E. Hannah, J. Scott, and S. Trommer, ed. Expert knowledge in global trade. London, New York: Routledge, 21–40.