ABSTRACT

The original Maastricht regime designed the Eurozone’s fiscal segment in a way that sought to keep member states’ treasury budgets balanced by disciplining them through market forces, reducing the overall volume of public indebtedness, prohibiting monetary financing, and avoiding that Eurozone treasuries bail each other out. In this article, we analyse how these ‘neoliberal’ rules for fiscal governance have been gradually superseded by an alternative approach that we call ‘governing through off-balance-sheet fiscal agencies’ (OBFAs). OBFAs are special purpose vehicles that complement treasuries in supporting public investment, offering solvency insurance for banks, providing capital insurance of last resort for other treasuries, and expanding the stock of safe assets. By sponsoring OBFAs, treasuries can substitute ‘actual’ liabilities on their balance sheets, which are potentially in conflict with the EU’s neoliberal fiscal rules, with ‘contingent’ liabilities – guarantees that do not appear on-balance-sheet. Together, national and supra-national treasuries and OBFAs form a ‘fiscal ecosystem’ in which neoliberal fiscal rules get re-emphasised but in practice are increasingly mitigated. This new mode of Eurozone fiscal governance is reflected not only in multiple policies implemented since 2010 – the Recovery and Resilience Facility for example – but also represents the main strategy in many Eurozone reform proposals.

Introduction

The Coronavirus pandemic saw the Eurozone mobilising unprecedented sums of money to deal with its fallout. National treasuries dabbled in innovative policy responses, from bailouts of big companies and no-questions-asked grants and guarantees to smaller firms, to various forms of payroll retention schemes, temporary benefit top-ups, and even a universal basic income experiment in Spain. When the European Commission announced it would create a Recovery and Resilience Facility to issue €672.5bn of mutualised debt to be used as grants and loans to pandemic-stricken EU member states (Brunsden et al. Citation2020), the German finance minister Olaf Scholz read the event as a Hamiltonian moment (Dausend and Schieritz Citation2020) that may profoundly alter the course of the European integration project (Guttenberg et al. Citation2021).

These developments seem to stand in sharp contrast to the ‘neoliberal’ rules of fiscal governance that have been described as dominating Eurozone policies beforehand (Parker and Pye Citation2018, Ojala Citation2020). Indeed, the post-crisis scholarship on the fiscal arm of the state has underlined the reinforcement of these rules via austerity measures that have acted like a straitjacket on the fiscal capacities of many states (Blyth Citation2013, Matthijs and McNamara Citation2015, Stockhammer Citation2016, Perez and Matsaganis Citation2018, Crespy Citation2020). The massive bailouts and vast stimulus programmes unleashed to prevent economies from collapsing led to the swelling of national debt across countries. Increasing risk premia on sovereign debt, falling investor confidence, deteriorating credit ratings, and the discovery of a seeming debt threshold beyond which countries became insolvent (Reinhart and Rogoff Citation2010; later debunked, see Herndon et al. Citation2014) led to the development of what has been called the ‘consolidation state’ (Streeck Citation2014), a set of policies designed above all to restructure public finances and reduce governments’ deficit ratios below the growth rate. In order to consolidate treasury balance sheets, austerity measures of various types, self-imposed or dished out as conditionalities for sovereign bailouts, became the default policy to accomplish this. Furthermore, a flurry of new regulations – for instance, the ‘Six Pack’ and the ‘Fiscal Compact’ – designed to increase fiscal surveillance and strengthen the grip of EU’s institutions on national budgets came into force in the aftermath of the Eurocrisis (Laffan and Schlosser Citation2016).

However, behind this very visible battle fought through lengthy political deliberations, negotiations, and even referenda that froze or retrenched fiscal capacities in targeted countries and at the European level, other developments were in fact taking place that were supplementing or replacing treasury functions through technocratic means and largely by stealth. Making them apparent can be facilitated by adopting the conceptual framework of ‘critical macro-finance’ (CMF) and thinking of the Eurozone’s fiscal segment as a web of interlocking balance sheets (Gabor and Vestergaard Citation2018, Dutta et al. Citation2020, Gabor Citation2020). This analytical approach, fostered by the work of the Bank for International Settlements (Tooze Citation2018), is driven by the conviction that institutional reality in the monetary and financial system is best understood if we portray money and debt as entries on balance sheets that exist in between different institutions and individuals in line with the rules of double-entry bookkeeping (Mehrling Citation2011, Murau and Pforr Citation2020).

Drawing on the CMF framework, we argue in this article that, even though the basic tenets of the the ‘neoliberal’ rules for European fiscal governance are still in place and have been re-emphasised repeatedly (e.g. via the 2010 European Semester and the 2012 Fiscal Compact as political responses to the 2009–12 Eurocrisis), the Eurozone has increasingly developed a workaround. This is based on the continuously expanding use of what we call ‘off-balance-sheet fiscal agencies’ (OBFAs), which by now has reached a systemic level and can justifiably be called a new ‘mode’ of Eurozone fiscal governance. Governing through OBFAs implies that activities which treasuries are not allowed or able to carry out by law, agreement, or political compromise increasingly get outsourced to balance sheets that are less restricted legally and politically – in some cases, they are even registered under a different jurisdiction. This process resembles in many respects the dynamics that lay at the core of shadow banking, which emerged in the 1970s to circumvent bank regulation (Nesvetailova and Guter-Sandu Citation2015). It particularly mirrors the use of Government Sponsored Enterprises in the US as a tool of statecraft to pursue policy objectives while circumventing budgetary constraints (Quinn Citation2017).

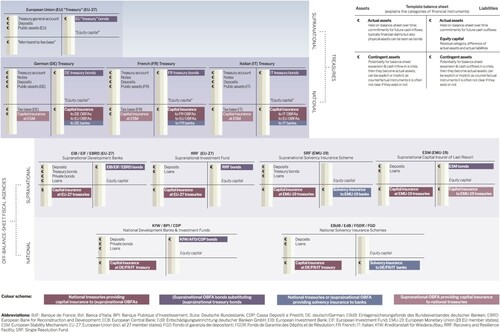

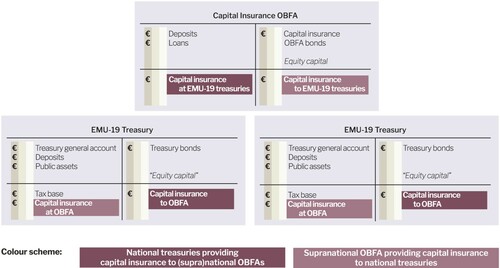

The first step to understand how governing through OBFAs works is to acknowledge that, taken together, the balance sheets of treasuries and OBFAs in the Eurozone form a ‘fiscal ecosystem’ – a somewhat opaque medley of treasuries and OBFAs on a European and a national level that has developed a specific division of labour given numerous constraints, many of them self-inflicted by the neoliberal fiscal governance logic. depicts the setup of the Eurozone’s fiscal ecosystem as a web of interlocking balance sheets. For sake of simplicity, we focus on three countries – Germany, France, and Italy – as representations of Eurozone countries with current and financial accounts that are in surplus, balanced, and deficit, respectively; still, the model could easily be extended to all Eurozone countries (EMU-19). On the one hand, the model shows the national and supranational treasury balance sheets – i.e. the German, French, and Italian national treasuries, which have the right to raise taxes and issue bonds, as well as the EU ‘Treasury’ which we write in quotation marks as it does not have full rights to taxation and bond issuance. On the other hand, the model depicts a number of OBFAs, which complement and support the work of treasuries. On a European level, we can find the European Investment Bank (EIB), the European Investment Fund (EIF) and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) as well as the new Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF) as investment agencies; the Single Resolution Fund (SRF) as solvency insurance for systemically important banks; and the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) to provide capital insurance of last resort. On the national level, the model shows German, French, and Italian national development banks (the Kreditanstalt für Wiederaufbau, KfW, the Banque Publique d’Investissement, BPI, and the Cassa Depositi e Prestiti, CDP); as well as national deposit insurance schemes (the Einlagensicherungsfonds des Bundesverbandes deutscher Banken, EbdB, the Entschädigungseinrichtung deutscher Banken GmbH, the Fonds de Garantie des Dépôts et de Résolution, FGDR, and the Fondo di Garanzia dei Depositanti, FGD).

As the template balance sheet in the top right of explains, for each of those institutions represented as balance sheets, we list different instruments they issue as liabilities and hold as assets. The left-hand side of the balance sheets indicates assets, the right-hand side liabilities. We follow the Minskian idea which informs CMF that assets are financial devices promising a future cash inflow, whereas liabilities lead to future cash outflows (Minsky Citation1986). Note that while we abstract here from actual physical assets such as buildings and roads, this perspective allows us to think of them as a form of bonds which yield future cash inflows.Footnote1 The crucial cash-outflow-commitments are the sovereign bonds issued by treasuries or different forms of OBFA bonds. Importantly, our model distinguishes between ‘actual assets and liabilities’ in the upper row of each balance sheet and ‘contingent assets and liabilities’ in the lower row. Actual assets and liabilities can in principle be recorded on-balance-sheet at a particular point in time; the difference between both is the institution’s ‘equity capital’. However, an adequate analysis of the Eurozone’s fiscal ecosystem must pay similar attention to contingent assets and liabilities. Those are implicit or explicit guarantees by higher-ranking balance sheets to create emergency liquidity in a crisis, which are not accounted on-balance-sheet in absence of a crisis – they may also be called insurances or backstops. Fiscal governance through OBFAs, in its essence, replaces actual liabilities on treasuries’ balance sheets with contingent ones.Footnote2

The colour scheme in shows how within the Eurozone’s fiscal ecosystem, the neoliberal rules for fiscal governance are increasingly mitigated by the spreading mode of ‘fiscal governance through OBFAs’ – arguably to an extent that they are prevalent in name only. On the one hand, national and supranational OBFAs in the Eurozone’s fiscal ecosystem have taken over tasks that could normally be carried out by treasuries but are prevented by the neoliberal rules of fiscal governance: the issuance of bonds, the provision of solvency insurance to banks, and the provision of capital insurance to other treasuries. On the other hand, these OBFAs receive a capital insurance from Eurozone national treasuries. This describes the explicit or implicit guarantee to recapitalise or bail out the OBFA in case of negative ‘equity capital’ (Haldane and Alessandri Citation2009). While explicit guarantees often have a quantitative limit, it stands to reason to believe that these will be adjusted if necessary and are therefore typically unlimited. We represent this as contingent liabilities for national treasuries and contingent assets for OBFAs, which are not subject to compulsory reporting on balance sheet. In sum, OBFAs – like shadow bank special purpose vehicles – create actual assets and liabilities that are guaranteed by treasuries but do not appear themselves on treasury balance sheets, only in the form of implicit contingent assets and liabilities.

The remainder of this article will flesh out our argument in greater detail. The second section provides a historically informed analysis of how fiscal coordination was envisaged in official EU policymaking circles and conceptualises the ‘neoliberal’ rules of fiscal governance. The third section theorises the mode of governance through OBFAs and shows with the help of balance sheet examples how it mitigates the neoliberal rules in four different activities that treasuries usually carry out: OBFAs support public investment, offer solvency insurance for banks, provide capital insurance of last resort for other treasuries, and expand the stock of safe assets. This applies both to policies that have already been implemented and policies that are currently being processed or discussed. The fourth section concludes.

The Neoliberal Rules for Eurozone Fiscal Governance

In the wake of the Eurozone crisis, a new buzzword appeared in the discourse of European and national officials. Although long-debated within academic circles, the notion of ‘governance’ acquired a new function within the Eurozone policy realm, being adopted widely (and differently) as a discursive platform to legitimize and advance specific visions of Eurozone reform (Jabko Citation2019). Improving economic governance throughout the EU was seen as a sure-fire way to avoid political contention and mobilise the electorate. In a broad sense, economic governance might encompass the entire set of institutions and procedures used to pursue economic policy objectives, with what is now called ‘monetary’ and ‘fiscal’ policy traditionally conducted in a coordinated manner. In the EU, however, the latter, due to evolving ideational and institutional idiosyncrasies, ended up operating differently. In this section, we provide an analysis of how the conceptualisations of monetary and fiscal governance in the EU have historically developed in connection with the design of the Eurozone’s fiscal ecosystem.

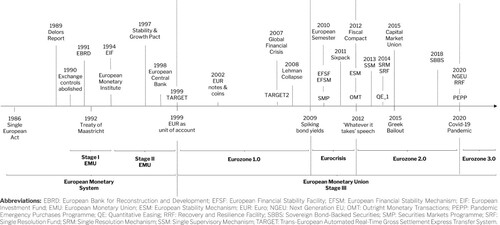

provides an overview on the steps of European monetary integration, starting with the 1986 Single European Act during the European Monetary System. After years of preparation, European Monetary Union (EMU) became effective as Stage III in 1999 when the Euro was introduced as unit of account and the TARGET system was put in place in between National Central Banks (NCBs) within the Eurosystem. In our periodisation, the first decade from 1999 to 2009 can be referred to as the ‘Eurozone 1.0’. The phase from spiking sovereign bond yields in 2009 until ECB President Mario Draghi’s famous ‘Whatever it takes’ speech in 2012 are the years of the ‘Eurocrisis’. From 2012 onwards – marked by institutional innovations set up during the crisis and two large scale reform projects, Banking Union and Capital Market Union – we witnessed the phase of the ‘Eurozone 2.0’. The year 2020 arguably marks the beginning of a new ‘Eurozone 3.0’, in which the Covid-19 induced global economic and financial crash has led to the emergence of new tools and policies the scope and implications of which we are only beginning to grasp.

The evolution of economic governance in the EU follows this periodisation closely. In the early days of the European Economic Community (EEC), the debate about economic governance was dominated by competing ideas about the most efficient way to improve economic integration and coordination. The so-called ‘monetarists’ or adherents to ‘locomotive theory’ argued for transferring monetary policy to the supranational level first and deeper economic integration would follow, whereas the ‘economists’ or adherents to ‘coronation theory’ argued for the reverse (Verdun Citation2013). In the 1970s, the Werner Report saw scope for a ‘Centre of Decision for Economic Policy’ that would reside at the supranational level and would oversee, among others, the coordination of national fiscal policies (Werner Citation1970). Lacking support, the plan never came to fruition, and the 1980s saw the discussion move forward to the topics of the European Monetary System and the Single European Act.

Towards the end of the decade, the Delors Report introduced a starker distinction between monetary and fiscal policy, with the former under the purview of a proposed supranational body, the European System of Central Banks, and the latter more firmly embedded in the national context (Delors Citation1989). Driven by commitments to their independence from national governments and political cycles, monetary technocrats found it much easier to delegate sovereignty to an independent authority endowed with a straightforward mandate (in this case, preserving ‘sound money’) than did finance or economic ministers, which had responsibility over a much wider mandate and entertained more widely diverging ideas about how to exercise it (McNamara Citation1998). At the same time, although most levers of macroeconomic governance would remain under the prerogative of national governments, a compromise was struck that saw a role for ‘binding rules for budgetary policies’ (Delors Citation1989, p. 16).

Indeed, the Delors Report, which would feed into the 1992 Treaty of Maastricht and would inform the 1997 Stability and Growth Pact, announced the creation of a version of a Eurozone that would envisage a tight coupling of national treasury balance sheets with ex ante rules. These determined how treasuries are allowed to use their ‘elasticity space’ (Murau Citation2020), i.e. the extent to which their balance sheet can be extended through the issuance of sovereign debt. Eurozone 1.0 would be bound particularly by two indicators: the ratio of government deficit to GDP and the ratio of government debt to GDP, which should not exceed the reference values of 3 and 60 per cent respectively (currently Art. 126 TFEU). This form of fiscal governing at a distance (Rose and Miller Citation1992) did not directly control national treasuries’ balance sheets but subjected them increasingly to quantitative targets. This ensured that despite the leeway afforded to national treasuries they are still constrained by a supranational disciplinary logic that would forestall monetary instability at the European level induced by budgetary imbalances. Moreover, in the Eurozone 1.0, this logic was meant to be reinforced by an automated mechanism discussed in the Delors Report: the ‘disciplinary influence’ of ‘market forces’ on public finances, which would ‘penalise deviations from commonly agreed budgetary guidelines or wage settlements, and thus exert pressure for sounder policies’ (Delors Citation1989, p. 20). Although the Report acknowledges that this mechanism could be ‘too slow and weak’ or ‘too sudden and disruptive’, it nonetheless suggests that there is scope for market forces to supplement the binding rules emanating from the supranational level.

Given this double disciplinary bind, the rules for fiscal governance implemented in the Eurozone 1.0 have often been referred to as ‘neoliberal’.Footnote3 In this understanding, the main aspects of the neoliberal thrust of Eurozone governance are a restrained or downscaled role for the state in economic affairs and an emphasis on (free) markets as the ultimate arbiter of public policies (Gill Citation1998, Van Apeldoorn Citation2009, Dutta Citation2020, Ojala Citation2020). In broad terms, we agree with this description, but we want to take the analysis further and spell out what this would mean for the governance of the Eurozone fiscal segment.

In our framing, we narrow down the often contested label of ‘neoliberalism’ to four rules of fiscal governance, which have been implemented in Eurozone 1.0 (Arestis and Sawyer Citation2007). They mainly pertain to national Eurozone treasuries and present an idea of how fiscal governance can be carried out in a monetary union without political union. Following CMF, we express them in balance sheet terms. First, the main objective of treasuries is to keep the budget balanced while, second, reducing the overall debt burden, i.e. lowering the volume of treasury bonds outstanding relative to GDP. These ideas are reflected in the Stability and Growth Pact (Art. 121 and 126 TFEU) and predicated on the assumption that private financial markets are by and large efficient and can exert a disciplining function on public balance sheets (Rommerskirchen Citation2015). Expressed in balance sheet terms, these rules seek to minimise the issuance of treasury bonds as actual liabilities and keep the treasury balance sheets as downscaled as possible. Third, monetary policy is supposed to be kept separate from fiscal policy. Therefore, monetary financing is strictly prohibited (Art. 123 TFEU). In our CMF framework, this implies that treasuries cannot have central bank guarantees as contingent assets, but rather must be fully dependent on private banks – often called ‘markets’ – to buy them. Fourth, treasuries of Eurozone member states must not take over the responsibilities for each other’s public debt (no-bailout clause, Art. 125 TFEU). On-balance-sheet, this means that it should be impossible to shift treasury bonds from one national treasury to another or that treasuries could have their bonds as contingent assets on other treasuries’ balance sheets.

The 2009–12 Eurocrisis uncovered the shortcomings of these neoliberal rules of fiscal governance and represented a blow to all of its four dimensions. Instead of disciplining treasuries and reducing their budget deficit, the private balance sheets of banks and non-bank financial institutions contracted sharply and had to be bailed out by European treasuries, which had to activate the implicit capital insurance for their national banks and take on new debts for the bailouts (Pisani-Ferry Citation2011). The ensuing public debt crisis led to a collapse of all efforts to reduce overall indebtedness. Central banks’ emergency interventions and new policy tools such as Quantitative Easing further blurred the lines between monetary and fiscal policy, whilst a number of Eurozone deficit countries which were at the brink of sovereign default had to be supported by surplus countries in ways not foreseen by the Treaties (Jones et al. Citation2016).

Nevertheless, the official reaction from EU policymakers was to double down on the neoliberal rules of fiscal governance. The measures for the Eurozone 2.0 strengthened the capacity for fiscal surveillance of treasuries and the enforceability of the rules-based coordination regime (Laffan and Schlosser Citation2016). The Stability and Growth Pact was bolstered by the so-called ‘Six Pack’ which made it harder, for instance, to undo corrective measures. A new treaty dubbed the ‘Fiscal Compact’ sought to ensure compliance with the rules which included allowing the European Court of Justice to impose monetary sanctions on member states. The ‘Two Pack’ centralised powers further in the hands of the European Commission, which was now allowed to enhance its surveillance capacity of Member States’ budgetary plans. All in all, the fiscal governance rules ensuing the Eurocrisis tightened the constrains on domestic budgetary powers, reviving the accusations that the Eurozone is ‘incomplete’, lacks sufficient fiscal firepower or a fiscal union, or cannot function efficiently because it is not an ‘optimal currency area’ (Hallerberg et al. Citation2009, Harold Citation2012, Krugman Citation2012, De Grauwe Citation2013).

However, while the doctrine of the neoliberal rules of fiscal governance was maintained and affirmed on a declaratory level, the actual practice has developed workarounds. Starting with the immediate reaction to the Eurocrisis, new OBFAs emerged to bypass fiscal rules and budgetary politics. A similar process has been noted in the literature on national public investment banks and developmental banks (Mertens and Thiemann Citation2018), while other research has confirmed that contentious budgetary politics can trigger organisational innovations that act as fiscal policy placeholders (Park Citation2011, Quinn Citation2017). But what transpires here is that OBFAs are in fact a wider phenomenon suggestive of a deeper transformation in the Eurozone’s fiscal governance. Effectively, the neoliberal rules of fiscal governance, while alive and well in European treaties, are increasingly mitigated by what we call governing through OBFAs.

Eurozone Fiscal Governance Through Off-Balance-Sheet Fiscal Agencies

The Eurozone’s mode of fiscal governance through OBFAs gives policymakers more leeway to pursue public policy goals. It affects four different dimensions to treasuries’ operations: OBFAs can support public investment, offer solvency insurance for banks, provide capital insurance of last resort for other treasuries, and expand the stock of safe assets. This section looks at those four aspects and traces the shift towards using OBFAs – both with regard to policies that have already been implemented and policies that are currently being processed or discussed. In line with the CMF framework, we use balance sheets to explain theoretically how OBFAs complement treasuries in those activities and show how fiscal governance through OBFAs mitigates the four rules of neoliberal fiscal governance.

Supporting Public Investments

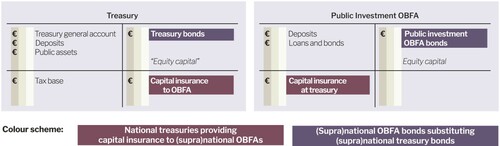

A first activity that national and supranational OBFAs undertake within the Eurozone’s fiscal ecosystem is complementing treasuries in financing and carrying out public investment. indicates how this works. Public investment OBFAs issue bonds as their liabilities to raise deposits which are then used to finance public investment. These bonds are functionally equivalent to when a treasury issues treasury bonds to finance public investments but do not appear as part of the overall state indebtedness. Therefore, treasuries can circumvent restrictions posed on their ability to issue sovereign bonds as an actual liability by sponsoring a public investment OBFA and just have a contingent liability as it issues a capital insurance that is not formally reported on-balance-sheet. This contingent liability allows the OBFA to essentially operate as a quasi-autonomous arm of the treasury, extending its activities, but without being constrained by the same regulations governing the treasury.

The primary public investment OBFAs in the Eurozone have traditionally been state banks or state development banks.Footnote4 They have a long history as special purpose vehicles (SPVs) to support large-scale investment. The Italian CPD dates back to 1850 and received a boom in its relevance after the unification of Italy. The French BPI was founded in 2013, but its roots extend back to the creation of Caisse des dépôts et consignations, a public investment institution founded in 1816 and absorbed together with a number of other financial entities by the BPI. The German KfW was created in 1948 to help finance the reconstruction after the war. The EIB was conceived with the 1957 Treaty of Rome to support the creation of the European Single Market, and the EBRD dates back to 1991 when it was set up to support the economic transition in Eastern Europe after the fall of the Iron Curtain (Mertens et al. Citation2021).

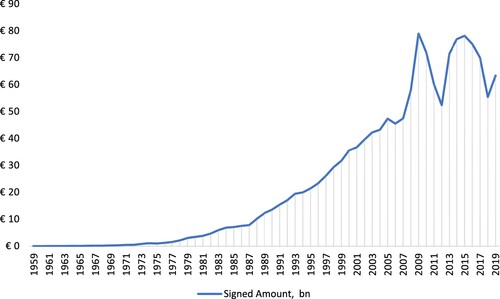

Hence, when EMU became effective in 1999, all those institutions were already part of the Eurozone’s fiscal ecosystem. During the Eurozone 1.0, however, they received little attention as the private financial system was attributed a successful role in providing investment. This changed considerably after the Eurocrisis when the EIB substantially expanded its lending volume (see ) and shifted again to the centre of scholarly attention (see e.g. Clifton et al. Citation2018, Liebe and Howarth Citation2019).

Figure 4. EIB lending volume and projects financed, 1960–2019. Source: European Investment Bank data portal.

This revival of public investment OBFAs in the Eurozone should be seen in light of the neoliberal rules of fiscal governance. The Stability and Growth Pact was introduced to put the balance sheet developments of different Eurozone treasuries in tune. At the same time, it introduced artificial restrictions on treasuries’ elasticity space. These restrictions were asymmetric in the sense that they were less binding in expansionary phases but decisive in contractionary phases. As the Eurozone 1.0 was by and large expansionary, OBFAs played less of a role. However, when the Eurocrisis hit, the associated bailouts and the setting in of the bank-sovereign doom loop heralded a contractionary phase that was even further reinforced by the Fiscal Compact and the European Semester. In these circumstances, an increase in lending stemming from public investment OBFAs like the EIB served as a mitigating factor for expanding elasticity space in an environment of austerity and depressed investment coming from national treasuries. This was more so the case in the context of the EU ‘Treasury’ not being able issue its own bonds for funding EU projects. Some exceptions to this notwithstanding, the EU ‘Treasury’ balance sheet is indeed highly inelastic and dependent on the multiannual households negotiated by the EU member states. The EIB and its subsidiary, the EIF created in 1994, therefore, may not have substituted all functions of fully-fledged treasuries, but they have come in as OBFAs that mitigate some of those restrictions and are pivotal to building a ‘hidden investment state’ (Mertens and Thiemann Citation2019) at the heart of the EU.

The year 2020, which arguably marks the beginning of a Eurozone 3.0, augured a further proliferation of public investment OBFAs. For instance, in March, the EIB announced it would mobilise up to EUR 40 billion additional lending (EIB and EIF Citation2020). In July, with treasury balance sheets pushed to the limits due to the Covid-19 response, the European Council voted for a Covid-19 relief package known as NextGenerationEU (NGEU) that not only grants extended rights to the EU ‘Treasury’ to issue bonds up to a limit of EUR 750 billion until the year 2026 but also sets up the RRF as a new OBFA to finance public investment (European Council Citation2020). This ties in with recent developments for national treasuries in countries that used to be at the forefront for advocating fiscal restraint. For instance, in September, the Dutch ministry of finance launched the EUR 20 billion National Growth Fund (Rijksoverheid Citation2020). Not long before that, two leading German economic think tanks representing both employers and unions had jointly called for a EUR 450 billion national investment fund (Bardt et al. Citation2019).

In sum, governing through OBFAs for the purpose of fostering public investment has a long tradition in Europe. OBFAs became part of the Eurozone, even though they are not specific EMU-19 institutions but cater to the entire EU. With reduced relevance during the Eurozone 1.0, public investment OBFAs witnessed a revival in the Eurozone 2.0 and seem to be among the primary governance choices to tackle the issues of the Eurozone 3.0.

Offering Solvency Insurance for Banks

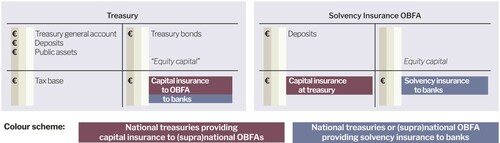

A second activity in which OBFAs support national and supranational treasuries in the Eurozone fiscal governance regime is in providing solvency insurance for the banking system. Solvency insurance implies that depositors in a bank have their deposits refunded in case the bank goes bankrupt.Footnote5 Historically, deposit insurance schemes have been introduced ad hoc by treasuries. Most prominently, this happened during the Roosevelt administration in 1933 to halt the cascading bank failures of the Great Depression (Silber Citation2009). With the creation of the US Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) in 1935, this function was delegated to OBFAs (Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation Citation1984). Since then, this practice has become commonplace internationally. Solvency insurance OBFAs accumulate deposits ex ante via contributions of member banks. However, as they administer emergency liquidity only up to a certain limit, they still have a capital insurance from treasuries on whose behalf they are acting. Any such ex ante limit may be too low in case of a deep systemic crisis and may necessitate that national treasuries use their elasticity space and issue new treasury bonds to raise new deposits and stock up the insurance vehicles. Therefore, these vehicles have a treasury guarantee as implicit contingent asset, which makes them de facto OBFAs. shows the connection between treasuries and solvency insurance OBFAs to provide solvency insurance for the banking system.

In the Eurozone 1.0, solvency insurance mechanisms had remained entirely national and were not harmonised. Moreover, the prohibition to monetise public debt incorporated in the Eurozone’s mode of fiscal governance (Art. 123 TFEU) hampered national treasuries’ ability to provide solvency insurance to their domestic banking system as it implied that they could only issue new sovereign bonds on the secondary market where they would be bought by private banks, and not sell them on the primary market to central banks. The disciplining effect of market forces inscribed in the neoliberal rules of fiscal governance were supposed to prevent national treasuries from overissuing sovereign debt and instead incentivise them to keep their budget balanced. Prohibiting the ECB and NCBs from buying treasuries on the primary market was a stark change from other monetary architectures in which this is a normal and legitimate practice (Ryan-Collins and van Lerven Citation2018).

The Eurocrisis turned the logic of these rules upside down. Instead of exhibiting stabilising behaviour as expected by the efficient markets hypothesis, the shadow banking system collapsed in the 2007–9 Financial Crisis and spilled over to European banking systems (Nesvetailova Citation2010, Copelovitch et al. Citation2016). From 2009 onwards, banking systems did not deliver on their intended role to induce discipline and control European treasuries to exhibit fiscal prudence. By contrast, treasuries had to forego prudence and take on masses of new sovereign debt to bail out national banks at the brink of bankruptcy. Hence, the Eurocrisis showed the inherent flaws of the neoliberal fiscal governance rules which were a fair-weather construct in so far as it did not foresee the inherent instability of finance and the possibility of endogenous default (Minsky Citation1986).

The main response to the banking crisis for the Eurozone 1.0 was the introduction of the Banking Union – a project announced via the Four Presidents’ Report in 2012 (Van Rompuy et al. Citation2012). Even though the actual meaning and policies of the Banking Union have changed repeatedly, it has three main pillars (Howarth and Quaglia Citation2016): First, the supervision of large Eurozone banks would no longer be carried out by national supervisors but would be organised supranationally at the ECB (through the so-called ‘Single Supervisory Mechanism’, SSM). Second, a Eurozone-wide resolution mechanism would be put in place to make it possible that systemically important banks enter bankruptcy while maintaining their systemic function during the crisis (the so-called ‘Single Resolution Mechanism’, SRM). Third, all Eurozone banks would become subject to standardised regulations for deposit insurance (the ‘European Deposit Insurance Scheme’, EDIS). While the SSM and SRM were quickly put into force between 2013 and 2016, the EDIS plans have stalled due to fierce objections by some member states (cf. European Commission Citation2020).

While these mechanisms primarily target the banking and central banking segments of the Eurozone architecture, they have implications for the Eurozone’s fiscal governance regime which further points to the mode of governing through OBFAs. On the one hand, the Single Resolution Fund (SRF) is an OBFA that was introduced via the Regulation (EU) No 806/2014 (SRM Regulation). From 2016 to 2023, systemically important Eurozone banks have to pay in contributions until they reach the target level of at least 1 per cent of total deposits covered. These contributions should be available in the next crisis to provide emergency liquidity while the resolution plans for systemically important banks are being carried out (Single Resolution Board Citation2020). However, there is no guarantee that the full sum will be enough. Instead, implicit guarantees have been put in place by national treasuries to supply more funds. Due to the contingent nature of these assets and liabilities, the SRF should best be understood as an OBFA.

On the other hand, the plans for a Eurozone-wide deposit insurance scheme would foresee the creation of a European Deposit Insurance Fund (EDIF) as a new Eurozone-wide OBFAs next to the SRF. So far, national deposit insurance schemes operate with OBFAs such as the EbdB, the EdB, the FGDR and the FGD. According to the draft regulation of the European Commission finalised in 2015, the EDIF ‘should be financed by direct contributions from banks’ while still receiving implicit fiscal backstops from national treasuries as ‘only extraordinary public financial support should be considered to be an impingement on the budgetary sovereignty and fiscal responsibilities of the Member States’ (European Commission Citation2015, p. 23). While the process has been stalled for several years, the widely held expectation is that the plan will sooner or later be realised.

In sum, we can see that the project of Banking Union, insofar as it involves institution-building on a European level, also follows the logic of governing through OBFAs. This is partly a consequence of the disciplining stipulations for the behaviour of treasuries and the Eurosystem built in the original Eurozone architecture along the lines of the neoliberal rules of fiscal governance.

Providing Capital Insurance of Last Resorts for Other Treasuries

Third, OBFAs support treasuries in acting as capital insurers of last resort for other treasuries.Footnote6 Once a crisis hits, treasuries are the ultimate backstops in a monetary architecture to provide emergency elasticity by providing loans or transfers to other balance sheets while taking on new debt themselves. Whether Eurozone treasuries should also grant such support to each other has always been an intricate question – the big conflict line of ‘monetary solidarity’ (Schelkle Citation2017, Hübner Citation2019) – and was ruled out in the Maastricht Treaty via the no-bailout clause (Brunnermeier et al. Citation2016). However, as indicates, capital insurance OBFAs are a way of circumventing this Treaty level norm. Instead of having treasuries directly provide capital insurance to each other, capital insurance OBFAs act as an intermediary. Treasuries jointly sponsor such OBFA by directly paying in some basic funds while endowing it with a capital insurance as contingent liability. A crisis-ridden Eurozone treasury may request capital support from the OBFA, which it would not be allowed to get from another treasury. Instead of shifting actual liabilities in between treasury balance sheets, this mechanism operates with contingent liabilities of non-crisis treasuries which enable the capital insurance OBFA to increase its liquid funds through OBFA bond issuance, if necessary.

The need for treasuries providing capital insurance for each other can be seen in the differences of refinancing costs. provides an overview of the sovereign bond spreads of Germany, Spain, Greece, Italy, and Portugal from 1994 to 2015. During EMU Stage II, the interest rates converged to the German basic level and remained there throughout the Eurozone 1.0. Contrary to the desire of surplus countries, markets’ outside perception may very well have been that an implicit capital insurance from Germany for those other treasuries was in place as ex ante treaty regulations cannot overrule financial necessities in a monetary union, and that by introducing the single currency, all European sovereign bonds would face the same credit risk as the German ones. In the Eurocrisis, interest rate differentials on sovereign bonds for Greece, Italy, Portugal, and Spain skyrocketed. With the sudden rise in refinancing costs, the debt levels those countries had attained during the Eurozone 1.0 became untenable. The group of countries hit hardest by the crisis were facing bankruptcy, defined as a default on their promises to pay back their maturing sovereign debt, unless help to service their debt was extended despite the no-bailout clause.

Figure 7. Interest rates of German, Spanish, Greek, Italian and Portuguese bonds, 1994–2015. Source: ECB Statistical Data Warehouse.

In 2010, during the peak phase of the Eurocrisis, two temporary emergency OBFAs were set up: the European Financial Stability Facility (EFSF) and the European Financial Stability Mechanism (EFSM). The EFSF was sponsored by Eurozone treasuries as a SPV under Luxemburg law and was authorised to issue bonds on private capital markets with an eventual borrowing limit of EUR 780 billion. The EFSM is a similar SPV that is partly guaranteed by the EU Commission using the EU budget as collateral. It has the authority to raise up to EUR 60 billion through bond issuance. Between 2011 and 2015, both the EFSF and the EFSM gave loans to the Irish, Portuguese, and Greek treasuries against conditionalities to prevent their sovereign default.

In 2012, those temporary OBFAs were replaced by the European Stability Mechanism (ESM). In contrast to the EFSF and the EFSM, the ESM is a permanent OBFA based on an international treaty. It has an authorised capital of EUR 700 billion of which EUR 80 billion have been paid-in ex ante and EUR 620 billion are callable (ESM Treaty). A Eurozone country is only allowed to make use of the ESM after signing the Fiscal Compact, which makes the introduction of a national debt break and the commitment to the amended Stability and Growth Pact mandatory. In effect, a Eurozone country that wants to request support from the ESM has to rhetorically submit to the neoliberal rules of fiscal governance to then be partly relieved from them by creating elasticity on an OBFA.

During the Eurozone 2.0 years, Brussels think tanks repeatedly launched the idea of transforming the ESM further into a European Monetary Fund (EMF). Sapir and Schoenmaker (Citation2017) proposed that a hypothetical EMF would build on the existing structures of the ESM but offer an orderly procedure to deal with sovereign default. As it would no longer be bound by the unanimity rule, it could act more proactively and function as proper counterpoint to the ECB in matters of financial stability. It would thus provide a version of the long debated ‘fiscal union’, though not by committing to a unified EU Treasury but by going for the ‘governance through OBFA’ mode all the way and politicising a newly created OBFA on a European level, endowed with a greater amount of competencies. Even though the EMF proposal is currently on hold, it may be pulled out of the hat once the next sovereign debt crisis hits.

In sum, Eurozone fiscal governance at the beginning of the Eurozone 3.0 is in a situation where the no-bailout clause as a key neoliberal rule of fiscal governance is still in place on paper but alleviated by workarounds based on capital insurance OBFAs. These provide a solution that neither the creditor nor the debtor countries are fully happy with. Where populist voices in creditor countries bemoan the fact that taxpayer money is allegedly used to pay for deficit countries debt, the debtor countries receive only just-enough emergency loans to keep them alive while having to face conditionalities that they perceive both as humiliating and restricting their policy space. Governance through OBFAs defines the current modus operandi in a conflict about sharing responsibilities over the issuance and service of public debt that has been looming on the continent for generations.

Expanding the Stock of Safe Assets

Fourth, OBFAs may be used to increase the amount of safe assets for the financial system. In the United States, Government Sponsored Enterprises (GSEs) such as Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac are OBFAs that support the treasury in supplying safe assets (Gorton et al. Citation2012). While the Eurozone does not presently have comparable vehicles, serious preparations are under way to introduce such an OBFA in the context of the Banking Union and Capital Market Union initiatives, including a draft regulation by European Commission (Citation2018).

In economists’ parlance, a safe asset is a ‘simple debt instrument that is expected to preserve its value during adverse systemic events’, as it is ‘information insensitive’ and has ‘special value during economic crises’ (Caballero et al. Citation2017, pp. 26–7). The most common safe assets are treasury bonds. Holding them allows all other balance sheets such as banks, non-bank financial institutions, and households to ‘store wealth’ even in times of crisis, i.e. maintain a given level of balance sheet expansion over time. From this point of view, treasury bonds are themselves a public good that is in high demand and constant undersupply. The contemporary financial system has come to rely heavily on safe assets as collateral for repo markets and monetary policy implementation. Moreover, the Basel regulations require banks to maintain a certain amount of safe assets in relation to their equity capital (Brunnermeier et al. Citation2012, pp. 1–2).

The Eurozone fiscal ecosystem, as is widely argued (Hill Citation2019), faces a safe asset shortage. Eurozone balance sheets do not create a sufficient volume of ‘information insensitive’ debt to satisfy the demand for it. The neoliberal rules of Eurozone fiscal governance, which have a one-dimensional understanding of sovereign debt and are geared towards reducing the overall volume of treasury bonds issued, certainly contribute to this safe asset shortage. While there is ample supply of ‘deficit’ country treasury bonds, markets do not perceive them as safe assets. The main safe asset, German treasury bonds, by contrast are so much sought after that they continuously have negative interest rates – investors pay the German treasury money in order to be able to store their wealth with them. To satisfy their demand for safe assets, European banks and non-bank financial institutions routinely turn to US treasury bonds as safe assets (Pozsar Citation2020).

The first-best solution to address the Eurozone safe asset shortage would be to create a European treasury that issues EU or Eurozone sovereign bond (‘Eurobonds’), backed by the treasuries of all member states. But this is not only highly contested among Eurozone member states but also clashes with the no-bailout clause in the TFEU. To nevertheless provide a Eurozone-wide safe asset that helps overcome the segregation of Eurozone banking systems, a number of second-best proposals have been developed (Claeys Citation2018, Gabor and Vestergaard Citation2018, Leandro and Zettelmeyer Citation2019).

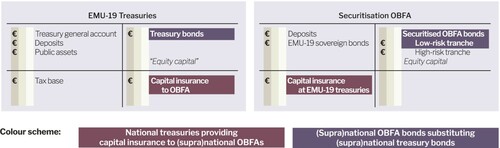

Many of those proposals seek to mitigate the problem through the creation of an OBFA that buys up sovereign bonds and securitises them by packaging and then slicing them up into tranches with different risk profiles. This idea dates back to a proposal of the Euro-nomics group (Brunnermeier et al. Citation2012) for the introduction of European Safe Bonds (ESBies) issued by a public European Debt Agency (EDA). The European Systemic Risk Board (ESRB) adopted the suggestion by van Riet (Citation2017) who brings up the possibility that the ESM could take over the role on the proposed EDA. In 2018, the European Commission presented a draft regulation for ‘Sovereign Bond-Backed Securities’ (SBBS) which would be issued by a private sector OBFA. As demonstrates, this Securitisation OBFA would issue ESBies as their low-risk tranche. While the draft regulation seeks to rule out that Eurozone treasuries provide a capital insurance (European Commission Citation2018, p. 2), such claim is hardly credible. The Securitisation OBFA could only fulfil its purpose if there were a widely held believe that the Eurozone treasuries would support the OBFA in a systemic crisis. This point is reinforced by a report of the S&P rating agency which states that a securitisation OBFA with insufficient explicit capital insurance would be rated only in the lower half of investment grade (S&P Global Ratings Citation2017). Hence, if ever the SBBS proposal should be implemented, it would require at least that there were a widely held expectation about an implicit capital insurance.

In sum, the current official strategy to tackle the perceived safe-asset shortage in the Eurozone through a supranational securitisation vehicle is similarly indicative of the new mode of governance through OBFAs, whereby off-balance-sheet instruments are created to overcome the issue of shortage of safe assets and to mitigate the no-bailout clause inscribed in the neoliberal rules of fiscal governance.

Conclusion

This article has analysed how the neoliberal rules of Eurozone fiscal governance embedded in the original Maastricht regime are mitigated by fiscal governance through OBFAs. By applying a critical macro-finance framework to the fiscal segment of the Eurozone, we show how the budgetary straitjacket inscribed in the Maastricht Treaty and the logic of market discipline led policymakers wrestling with crises to devise creative ways of expanding the Eurozone fiscal ecosystem so that instruments that are normally under the purview of treasuries are still available but off-balance-sheet. We thus contribute to research showing how fiscal constraints spur imaginative ways of pursuing policy goals through off-balance-sheet channels. In the case of the Eurozone, our analysis has shown that fiscal off-balance-sheet policymaking is not a limited practice, but may very well be a wider governance mode in its own right.

Indeed, there is now a profusion of national and supranational OBFAs, while the introduction of more such vehicles is being discussed. They are used to increase the scope for public investment and expand the stock of safe assets to support a growing economy, all the while providing solvency insurance for banks and capital insurance for treasuries as mechanisms that shelter the economy in case of distress. In fulfilling these functions, they circumvent the neoliberal rules that have been conceived for the Eurozone with the release of the Delors Report in 1989, implemented in the Eurozone 1.0 in 1999, and reinforced in the wake of the Eurocrisis: keeping treasury budgets balanced, reducing the overall volume of public indebtedness, prohibiting monetary financing, and avoiding that Eurozone treasuries bail out each other.

What we have called Eurozone 3.0 – the new institutional and ideational set-up ushered in by the Covid-19 crisis – seems to follow this trend. Even though the issuance of hitherto sacrilegious common debt has been hailed as a Hamiltonian moment by some, there are reasons to doubt it augurs a fiscal union. That said, the fact that the main recovery instrument, NextGenerationEU, is constructed around the RRF, is an indication of a potential unspoken but growing consensus that governing through OBFAs is a legitimate and effective way of pursuing European public policy objectives in an environment of formal fiscal restraint. This certainly seems to be the case, at least given the OBFAs we have analysed above. These, linked as they are through a web of contingent assets and liabilities, extend the fiscal firepower of the Eurozone together with its governance capacity and explain, to an extent, why the lack of a fiscal union has not been a complete dealbreaker for the functioning of the Eurozone. And yet, it remains to be explored by further research to what extent this new form of governance is a good substitute for a traditional national – or in the case of the EU, supranational – treasury that is at arm’s length from the government and is responsive to political cycles.

Acknowledgements

We have presented earlier versions of this article at the 26th Annual Conference on Alternative Economic Policy in Europe (EuroMemo) in September 2020 and at the research seminar of the Department of International Politics at City, University of London in October 2020. For comments on this article at various stages, we wish to thank Yannis Eustathopoulos, Trevor Evans, Armin Haas, Marina Hübner, Roland Kulke, Elizaveta Kuznetsova, Perry Mehrling, Andrea Mennicken, Anastasia Nesvetailova, Fabian Pape, Stefano Pagliari, Dominique Plihon, Mathis Richtmann, Jamal Saadaoui, Etienne Schneider, Stefano Sgambati, Jens van ‘t Klooster as well as the anonymous reviewers.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Andrei Guter-Sandu

Andrei Guter-Sandu is an Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) Postdoctoral Fellow at the Centre for Analysis of Risk and Regulation and the Department of Accounting at the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE). His research interests include social and sustainable finance, central banking, and public governance of grand challenges.

Steffen Murau

Steffen Murau is a postdoctoral fellow at the Global Development Policy (GDP) Center of Boston University, City Political Economy Research Centre (CITYPERC) of City, University of London, and Institute for Advanced Sustainability Studies (IASS) in Potsdam. His research interests include monetary theory, shadow banking, the international monetary system, and the European Monetary Union.

Notes

1 It is important to stress that the balance sheets in this model are idealised economic balance sheets, not the actually reported balance sheets. A particular difficulty with treasuries as institutions is that they often do not even publish official balance sheets. In Germany, for example, the Ministry of Finance only operates with a cameralistic accounting methodology that registers cash inflows and outflows but does not compile actual balance sheets that would list everything the state owns and owes. The particular difficulty lies in assessing the value of public assets such as roads which cannot be resold and therefore do not have a market price. By consequence, this makes it close to impossible to come up with a statement about a state’s ‘equity capital’. Finally, it is always difficult to put a treasury’s most important ‘asset’ on-balance-sheet: the tax base. The right of a treasury to tax its citizens is the main source of future cash inflows but can hardly be treated as an accounting item in a meaningful way. In our methodology, we treat the tax base as a contingent asset.

2 Our way of depicting the Eurozone fiscal ecosystem as a hierarchical web of interlocking balance sheets in applies the methodology developed in Murau (Citation2020), which presents a full model of the Eurozone architecture that comprises four different segments: central banking, commercial banking, non-bank financial institutions and shadow banking, as well as the fiscal ecosystem.

3 Or sometimes ‘ordoliberal’, which, although technically different, indicates a similar mechanism of governing at a distance and of market discipline (Feld et al. Citation2015, Nedergaard and Snaith Citation2015, Ryner Citation2015, Schäfer Citation2016, Bonefeld Citation2017).

4 Calling them banks is a misnomer in so far as they are not actually in the business of issuing deposits as their liabilities and hence creating ‘money’.

5 In line with Haldane and Alessandri (Citation2009), we distinguish between solvency insurance where a treasury or OBFA targets banks’ deposits to the benefit of its counterparty, typically households or firms, and capital insurance where the treasury or OBFA targets the equity capital of a bank or another balance sheet to the benefit of that very institution.

6 In the context of the Eurozone literature, what we call ‘capital insurance of last resort’ is often referred to as a ‘lender of last resort’ function (see e.g. Schmidt Citation2020). We find this label somewhat misleading as it conflicts with the traditional role that central banks play when they expand their balance sheet and create reserves to provide emergency liquidity for banks through the discount window – an activity that lies at the heart of monetary policy.

References

- Arestis, Philip and Sawyer, Malcolm, 2007. Can the Euro area play a stabilizing role in balancing global imbalances?. In: Jörg Bibow and Andrea Terzi, eds. In: Euroland and the world economy. Global player or global drag? Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 53–71.

- Bardt, Hubertus, et al., 2019. Für Eine Solide Finanzpolitik. Investitionen Ermöglichen! Cologne: Institut der Deutschen Wirtschaft and Institut für Makroökonomie und Konjunkturforschung, IW-Policy Paper 10/19.

- Blyth, Mark, 2013. Austerity: the history of a dangerous idea. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Bonefeld, Werner, 2017. Authoritarian liberalism: from Schmitt via Ordoliberalism to the Euro. Critical sociology, 43 (4–5), 747–61. Available from: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0896920516662695.

- Brunnermeier, Markus, et al., 2012. European safe bonds (ESBies). The Euro-nomics Group.

- Brunnermeier, Markus, James, Harold, and Landau, Jean-Pierre, 2016. The Euro and the battle of ideas. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Brunsden, Jim, Khan, Mehreen, and Fleming, Sam, 2020. EU leaders strike deal on €750bn recovery fund after marathon summit. Financial Times, 21 July. Available from: https://www.ft.com/content/713be467-ed19-4663-95ff-66f775af55cc.

- Caballero, Ricardo J., Farhi, Emmanuel, and Gourinchas, Pierre-Olivier, 2017. The safe assets shortage conondrum. Journal of economic perspectives, 31 (3), 29–46.

- Claeys, Grégory, 2018. Are SBBS realley the safe asset the Euro area is looking for? Brussels: Bruegel, Blog, 28 May.

- Clifton, Judith, Díaz-Fuentes, Daniel, and Gómez, Ana Lara, 2018. The European Investment Bank: development, integration, investment? Journal of common market studies, 56 (4), 733–50. Available from: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12614.

- Copelovitch, Mark, Frieden, Jeffry A., and Walter, Stefanie, 2016. The political economy of the Euro crisis. Comparative political studies, 49 (7), 811–40.

- Crespy, Amandine, 2020. The EU’s socioeconomic governance 10 years after the crisis: muddling through and the revolt against austerity. Journal of common market studies. Available from: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.13083.

- Dausend, Peter and Schieritz, Mark, 2020. Olaf Scholz: “Schulden auf europäischer Ebene sollten kein Tabu sein”. Die Zeit, 19 May, sec. Politik. Available from: https://www.zeit.de/2020/22/olaf-scholz-europaeische-union-reform-vereinigte-staaten?utm_referrer=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.google.com.

- De Grauwe, Paul, 2013. Design failures in the Eurozone: can they be fixed? Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network, SSRN Scholarly Paper ID 2215762. Available from: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2215762.

- Delors, Jacques, 1989. Report on Economic and Monetary Union in the European community. Report to the European Council 17 April 1989. Committe for the Study of Economic and Monetary Union.

- Dutta, Sahil Jai, et al., 2020. Critical macro-finance: an introduction. Finance and society, 6 (1), 34–44. Available from: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2218/finsoc.v6i1.4407.

- Dutta, Sahil Jai, 2020. Sovereign debt management and the transformation from Keynesian to neoliberal monetary governance in Britain. New political economy, 25 (4), 675–90. Available from: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2019.1680961.

- EIB and EIF, 2020. The European Investment bank’s response to Covid-19. Fact sheet. Luxemburg: European Investment Bank and European Investment Fund. Available from: https://www.eif.org/attachments/covid19-eib-group-response-factsheet-en.pdf.

- European Commission, 2015. Proposal for a regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council amending regulation (EU) 806/2014 in order to establish a European deposit insurance scheme. Brussels: European Commission, COM(2015) 586 final. Available from: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52015PC0586&from=EN.

- European Commission, 2018. Proposal for a regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on sovereign bond-backed securities. Brussels: European Commission, COM(2018)339.

- European Commission, 2020. European deposit insurance scheme. Brussels: European Commission. Available from: https://ec.europa.eu/info/business-economy-euro/banking-and-finance/banking-union/european-deposit-insurance-scheme_en.

- European Council, 2020. Conclusions of the special meeting of the European Council, 17–21 July 2020. Brussels: European Council, EUCO 10/20.

- Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, 1984. The first fifty years. A history of the FDIC 1933–1983. Washington, DC: Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation.

- Feld, Lars P., Köhler, Ekkehard A., and Nientiedt, Daniel, 2015. Ordoliberalism, pragmatism and the Eurozone crisis: how the German tradition shaped economic policy in Europe. European review of international studies, 2 (3), 48–61. Available from: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3224/eris.v2i3.23448.

- Gabor, Daniela, 2020. Critical macro-finance: a theoretical lens. Finance and society, 6 (1), 45–55. Available from: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2218/finsoc.v6i1.4408.

- Gabor, Daniela and Vestergaard, Jakob, 2018. Chasing unicorns. The European single safe asset project. Competition and change, 22 (1), 139–64.

- Gill, Stephen, 1998. European governance and new constitutionalism: Economic and Monetary Union and alternatives to disciplinary neoliberalism in Europe. New political economy, 3 (1), 5–26. Available from: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13563469808406330.

- Gorton, Gary B., Lewellen, Stefan, and Metrick, Andrew, 2012. The safe-asset share. National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper 17777. Working Paper Series. Available from: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3386/w17777.

- Guttenberg, Lucas, Hemker, Johannes, and Tordoir, Sander, 2021. Alles Wird Anders – Wie Die Pandemie Die EU-Finanzarchitektur Verändert. Wirtschaftsdienst, 101 (2), 90–4.

- Haldane, Andrew and Alessandri, Piergiorgio, 2009. Banking on the state. Chicago, IL: Bank of England.

- Hallerberg, Mark, Strauch, Rolf Rainer, and von Hagen, Jürgen, 2009. Fiscal governance in Europe. Cambridge studies in comparative politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Available from: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511759505.

- Harold, James, 2012. Making the European Monetary Union. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Available from: https://www.hup.harvard.edu/catalog.php?isbn=9780674416802.

- Herndon, Thomas, Ash, Michael, and Pollin, Robert, 2014. Does high public debt consistently stifle economic growth? A critique of Reinhart and Rogoff. Cambridge journal of economics, 38 (2), 257–79. Available from: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/cje/bet075.

- Hill, Andy, 2019. The search for a Euro safe asset. London: International Capital Markets Association (ICMA).

- Howarth, David and Quaglia, Lucia, 2016. The political economy of European Banking Union. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hübner, Marina, 2019. Wenn Der Markt Regiert. Die Politische Ökonomie Der Europäischen Kapitalmarktunion. Frankfurt am Main: Campus Verlag.

- Jabko, Nicolas, 2019. Contested governance: the new repertoire of the Eurozone crisis. Governance, 32 (3), 493–509. Available from: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/gove.12389.

- Jones, Erik, Kelemen, Daniel R., and Meunier, Sophie, 2016. Failing forward? The Euro crisis and the incomplete nature of European integration. Comparative political studies, 49 (7), 1010–34.

- Krugman, Paul, 2012. Revenge of the optimum currency area. NBER macroeconomics annual 2012, 27 (June), 439–48.

- Laffan, Brigid and Schlosser, Pierre, 2016. Public finances in Europe: fortifying EU economic governance in the shadow of the crisis. Journal of European integration, 38 (3), 237–49. Available from: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2016.1140158.

- Leandro, Álvaro and Zettelmeyer, Jeromin, 2019. The search for a Euro safe asset. Washington, DC: Peterson Institute for International Economics, Working Paper 18-3.

- Liebe, Moritz and Howarth, David, 2019. The European Investment Bank as policy entrepreneur and the promotion of public-private partnerships. New political economy. Available from: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2019.1586862.

- Matthijs, Matthias and McNamara, Kathleen, 2015. The Euro crisis’ theory effect: northern saints, southern sinners, and the demise of the Eurobond. Journal of European integration, 37 (2), 229–45. Available from: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2014.990137.

- McNamara, Kathleen R., 1998. The currency of ideas: monetary politics in the European Union. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Mehrling, Perry, 2011. The new Lombard street. How the Fed became the dealer of last resort. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Mertens, Daniel and Thiemann, Matthias, 2018. Market-based but state-led. The role of public development banks in shaping market-based finance in the European Union. Competition and change, 22 (2), 184–204.

- Mertens, Daniel and Thiemann, Matthias, 2019. Building a hidden investment state? The European Investment Bank, national development banks and European economic governance. Journal of European public policy, 26 (1), 23–43.

- Mertens, Daniel, Thiemann, Matthias, and Volberding, Peter, 2021. The reinvention of development banking in the European Union. Industrial policy in the single market and the emergence of a field. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Minsky, Hyman P, 1986. Stabilizing an unstable economy. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Murau, Steffen, 2020. A macro-financial model of the Eurozone architecture embedded in the global offshore US-dollar system. Boston, MA: Global Development Policy Center, Global Economic Governance Initiative (GEGI), Boston University, GEGI Study July 2020. Available from: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2312/iass.2020.041.

- Murau, Steffen and Pforr, Tobias, 2020. What is money in a critical macro-finance framework? Finance and Society, 6 (1), 56–66.

- Nedergaard, Peter and Snaith, Holly, 2015. “As I drifted on a river I could not control”: the unintended ordoliberal consequences of the Eurozone crisis. Journal of Common Market Studies, 53 (5), 1094–109. Available from: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12249.

- Nesvetailova, Anastasia, 2010. Financial alchemy in crisis: the great liquidity illusion. London: Pluto Press.

- Nesvetailova, Anastasia and Guter-Sandu, Andrei, 2015. The good, the bad, and the fraud: securitisation and financial crime in light of the global financial crisis. In: Nicholas Ryder, Umut Turksen, and Sabine Hassler, eds. Fighting financial crime in the global economic crisis. London: Routledge, 128–43.

- Ojala, Markus, 2020. Doing away with the sovereign: neoliberalism and the promotion of market discipline in European economic governance. New political economy, 1–13. Available from: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2020.1729714.

- Park, Gene, 2011. Spending without taxation. FILP and the politics of public finance in Japan. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Parker, Owen and Pye, Robert, 2018. Mobilising social rights in EU economic governance: a pragmatic challenge to neoliberal Europe. Comparative European politics, 16 (5), 805–24. Available from: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1057/s41295-017-0102-1.

- Perez, Sofia A. and Matsaganis, Manos, 2018. The political economy of austerity in southern Europe. New political economy, 23 (2), 192–207. Available from: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2017.1370445.

- Pisani-Ferry, Jean, 2011. The Euro crisis and its aftermath. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Pozsar, Zoltan, 2020. Lombard street and pandemics. New York: Credit Suisse, Global Money Notes #28.

- Quinn, Sarah, 2017. “The miracles of bookkeeping”: how budget politics link fiscal policies and financial markets. American journal of sociology, 123 (1), 48–85. Available from: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1086/692461.

- Reinhart, Carmen M. and Rogoff, Kenneth S., 2010. Growth in a time of debt. American economic review, 100 (2), 573–8.

- Rijksoverheid, 2020. Nationaal Groeifonds. The Hague. Available from: https://www.rijksoverheid.nl/onderwerpen/nationaal-groeifonds.

- Rommerskirchen, Charlotte, 2015. Debt and punishment. Market discipline in the Eurozone. New political economy, 20 (5), 752–82.

- Rose, Nikolas and Miller, Peter, 1992. Political power beyond the state: problematics of government. The British journal of sociology, 43 (2), 173–205. Available from: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/591464.

- Ryan-Collins, Josh and van Lerven, Frank, 2018. Bringing the helicopter to ground. A historical review of fiscal-monetary coordination to support economic growth in the 20th century. UCL Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose Working Paper Series IIPP WP 2018-08.

- Ryner, Magnus, 2015. Europe’s ordoliberal iron cage: critical political economy, the Euro area crisis and its management. Journal of European public policy, 22 (2), 275–94. Available from: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2014.995119.

- Sapir, André and Schoenmaker, Dirk, 2017. We need a European Monetary Fund, but how should it work?. Brussels: Bruegel, Blog post, 29 May. Available from: https://bruegel.org/2017/05/we-need-a-european-monetary-fund-but-how-should-it-work/.

- Schäfer, David, 2016. A banking union of ideas? The impact of Ordoliberalism and the vicious circle on the EU banking union. Journal of common market studies, 54 (4), 961–80. Available from: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12351.

- Schelkle, Waltraud, 2017. The political economy of monetary solidarity. Understanding the Euro experiment. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Schmidt, Vivien A, 2020. Europe’s crisis of legitimacy: governing by rules and ruling by numbers in the Eurozone. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Silber, William L, 2009. Why did FDR’s bank holiday succeed? FRBNY economic policy review, 15 (1), 19–30.

- Single Resolution Board, 2020. What is the single resolution fund? Brussels: Single Resolution Board. Available from: https://srb.europa.eu/en/content/single-resolution-fund.

- S&P Global Ratings, 2017. How S&P global ratings would assess European “safe” bonds (ESBies). Frankfurt am Main: Standard & Poor’s, RatingsDirect, 25 Apr.

- Stockhammer, Engelbert, 2016. Neoliberal growth models, Monetary Union and the Euro crisis. A post-Keynesian perspective. New political economy, 21 (4), 365–79. Available from: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2016.1115826.

- Streeck, Wolfgang, 2014. The politics of public debt: neoliberalism, capitalist development and the restructuring of the state. German economic review, 15 (1), 143–65. Available from: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/geer.12032.

- Tooze, Adam, 2018. Crashed. How a decade of financial crises changed the world. New York: Viking.

- Van Apeldoorn, Bastiaan, 2009. The contradictions of ‘embedded neoliberalism’and Europe’s multi-level legitimacy crisis: the European project and its limits. In: Jan Drahokoupil, Laura Horn, and Bastiaan Van Apeldoorn, eds. Contradictions and limits of neoliberal European governance. Berlin: Springer, 21–43.

- Van Riet, Ad, 2017. Addressing the safety trilemma. A safe sovereign asset for the Eurozone. Frankfurt am Main: European Systemic Risk Board, Working Paper Series No 35.

- Van Rompuy, Herman, et al., 2012. Towards a genuine Economic and Monetary Union (“Four Presidents’ report”). Brussels: European Council, Report.

- Verdun, Amy, 2013. The building of economic governance in the European Union. Transfer: European review of labour and research, 19 (1), 23–35. Available from: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1024258912469343.

- Werner, Pierre, 1970. Report to the Council and the Commission on the realization by stages of Economic and Monetary Union in the community. Luxemburg: Council – Commission of the European Communities.

- Legal Documents

- ESM Treaty: Treaty establishing the European Stability Mechanisms.

- SRM Regulation: Regulation (EU) No 806/2014.

- TFEU: Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union.