ABSTRACT

This article examines the development of the World Bank’s agricultural credit programming between 1960 and 1990. I show how these projects constituted key sites where neoliberal development governance was initially articulated, negotiated, and contested. Agricultural credit was a key point of emphasis for the Bank during its ‘Assault on Poverty’ era in the 1970s. Agricultural programming in this era reflected a strong emphasis on agricultural development through marketisation and commercialisation, yet also very clearly demonstrated clear points of ambivalence around the role of credit in relation to agricultural markets. Agricultural credit projects increasingly included implicit or explicit conditionalities linked to the marketisation of interest rates, the commercialisation of state-owned agricultural lenders, and the marketisation of wider financial sectors into the 1980s. But these efforts to marketize and commercialise agricultural credit through these projects often reflected mundane operational challenges as much as ideological shifts, and themselves largely failed even on their own terms. Looking at the evolution of agricultural credit projects thus shows how broadly neoliberal positions were arrived at in part through trial and error adjustments to operational concerns, as well as how fraught the promotion of market-based financial systems was in practice even in the structural adjustment era.

Introduction

Structural adjustment had devastating effects on agriculture in the global south (Bernstein Citation1990, Gibbon et al. Citation1993; Woodhouse Citation2003). It has been common, as a result, to read structural adjustment as a kind of ground-clearing exercise for new rounds of primitive accumulation across the global south (e.g. Sassen Citation2010). It’s ironic, then, that structural adjustment was justified by its advocates precisely as a solution to declining agricultural productivity and rural poverty. The manipulation of prices and interest rates by governments were widely blamed for problems in agriculture in postcolonial settings. Giving free play to ‘market forces’ was thus, for neoliberal economists, embraced at least in part as a means of fostering agricultural prosperity (e.g. McKinnon Citation1973, Shaw Citation1973, Lal Citation2002). This is true of policy articulations of neoliberalism too. The World Bank’s infamous ‘Berg Report’, Accelerated Development in sub-Saharan Africa, identified improving the productivity of smallholder agriculture through liberalisation as a crucial means of restoring economic growth (World Bank Citation1980, pp. 50–51). Yet, this emphasis in the Berg report on the marketisation of agriculture did not dramatically mark it out from the Bank’s work in agriculture in the preceding decades.

In short, debates around agricultural policy in and around the era of structural adjustment bear a closer look as formative debates and as key sites of contradiction in the articulation of neoliberal development governance. This article contributes to this task through an examination of agricultural credit programmes at the World Bank from 1960 to 1990. Agricultural credit projects, broadly, were loans made by the World Bank for on-lending to farmers, whether through state-owned development banks or more complex structures of intermediation set up to encourage the participation of commercial banks.

I argue that these projects were a crucial field of activity where neoliberal approaches to development were negotiated and articulated. They are thus particularly revealing of some of the complexities and contradictions of neoliberal politics in practice. Neoliberalism is understood here, following Brenner et al., as a series of variegated ‘neoliberalising processes’, dating roughly to the 1970s, which have ‘facilitated marketisation and commodification while simultaneously intensifying the uneven development of regulatory forms across places, territories and scales’ (Brenner et al. Citation2010, p. 184; emphasis in the original). This analysis shows just how vital, and how fraught in practice, were the questions of what is to be subject to ‘market’ organisation, and what organisation on ‘market’ lines actually entailed. Seen from this angle, the rise of neoliberalism in global development was less ‘counter-revolution’ (per Toye Citation1993) or revenge of finance capital (per Harvey Citation2004, Fine and Saad-Filho Citation2017), and more a troublesome and failure-prone working out of a longer-run project of agricultural transformation. This history is revealing, in short, of the centrality of the uncertain and contested objects of marketisation to the historical development of neoliberalism.

The Bank articulated agricultural problems in terms emphasising the commercialisation and marketisation of agriculture as necessary steps to raising productivity and alleviating rural poverty as far back as the 1950s. By ‘marketisation’, I’m referring to efforts to establish ‘market’ mechanisms for pricing and distribution of agricultural products and outputs. By ‘commercialisation’, I mean related efforts to reform particular institutions (e.g. agricultural banks, marketing agencies) to operate like private for-profit firms, either by privatising them outright or, more often, by reforming their operations to emulate private firms more closely. Access to credit was understood as a vital means of facilitating the marketisation and commercialisation of agriculture more generally, but there was considerable uncertainty around whether agricultural credit itself could be delivered on market terms, and how this might be achieved. There was a growing effort at the Bank to ensure that the provision of finance itself was marketised and commercialised from the late 1970s onward. Agricultural credit projects were increasingly conditional on the removal of restrictions of interest rates, the commercialisation of state-owned agricultural lenders, and the marketisation of wider financial sectors. However, this turn was tentative and contested at all points. Efforts to marketize and commercialise agricultural credit through these projects themselves largely failed even on their own terms, and were abandoned by the early 1990s.

I develop this argument through a systematic analysis of documentary evidence related to the Bank’s agricultural credit programming from 1960 to 1990. I trace the scope and development of agricultural credit projects over time, and of contemporary debates within and around the Bank about agricultural credit. The analysis that follows is primarily focused on debates around, and the evolution of policy towards, agricultural credit within the Bank. In important respects the programmes I discuss were negotiated outcomes between the Bank and borrowing governments, and in shaping the actual contents of any particular project local political-economic dynamics were essential. Nonetheless, a detailed analysis of these dynamics is beyond the scope of the present article, and the debates within the Bank are more directly relevant to the task of working out the internal contradictions implicit in the rise articulation of a neoliberalising project in global development.

The first section below situates debates about agricultural credit in relation to existing research about neoliberalism and marketisation in global development. The second section discusses the research methods employed here and presents a brief picture of the scope and evolution of agricultural credit programming at the World Bank. The third and fourth sections explore particular unfolding controversies around credit pricing and interest rates and efforts to incentivize wider financial policy reforms, respectively.

In making these arguments, this article contributes to a pair of related literatures. First, in empirical terms, I contribute to recent efforts to interrogate the historical development of neoliberalism (e.g. Knafo et al. Citation2019, Best Citation2020), including the contradictory origins of neoliberalism in global development (Bair Citation2009, Plehwe Citation2009, Soederberg Citation2017, Van Waeyenberge Citation2018). While failure and troubleshooting of the kinds highlighted here are integral aspects of this history (see Best Citation2013; Citation2016; Harrison Citation2010; Peck Citation2010), the extent to which they are also vital to its origins is perhaps under-appreciated (though see Best Citation2020). Second, theoretically the emphasis on the contested and uncertain objects of marketisation contributes to a growing literature on processes of marketisation (e.g. Boeckler and Berndt Citation2013, Christophers Citation2014, Neyland et al. Citation2019, Nik-Khah and Mirowski Citation2019). Much of this literature has emphasised the contingent and performative character of markets and marketisation. The developments traced below show a range of subtle forms of contestation, limits, and political challenges underlying these processes, including basic questions of what is to be rendered subject to the market and how.

Agricultural Credit and the Uncertain Objects of Marketisation

It is common to date the rise of a coherent neoliberal programme in development governance to the late 1970s or early 1980s. This is often attributed to a neoliberal ‘counter-revolution’ in development economics (per Toye Citation1993), in which a number of thinkers articulated both an increasingly coherent critique of ‘dirigiste’ development planning and a ‘free market’ project in response (e.g. Lal Citation2002). The familiar story is that the collapse of the New International Economic Order (NIEO),Footnote1 and 1980s debt crisis presented an opening for the violent implementation of this counter-revolutionary programme across much of the global south.

Why focus on agricultural credit here? In the first place, agriculture (especially credit for agriculture) was a critical area of emphasis for the World Bank under the poverty agenda (see Best Citation2013, Mendes Pereira Citation2020, Rojas Citation2015). We can glean a rough indication of this from the fact that agricultural credit merited extended discussion, for instance, in both the Bank’s landmark Assault on World Poverty report in 1975 (World Bank Citation1975a), and the first World Development Report, published in 1978 (World Bank Citation1978, pp. 42–46). Credit was explicitly understood by the McNamara-era Bank as a ‘key element in the modernization of agriculture’ (World Bank Citation1974, p. 1). Indeed, the ‘assault on poverty’ deepened longstanding efforts to reform agricultural finance. Restricted access to formal credit for agriculture, especially for smallholder agriculture, and the resulting dependence on expensive and short-term credit from moneylenders or merchants had been identified as an obstacle to agricultural productivity in the global south going back to the the colonial period (e.g. Tun Wai Citation1957). But what’s critical is that agricultural credit in the Bank’s projects from the 1960s onwards was explicitly understood as a key component of the marketisation of agriculture.

Here it’s worth emphasising the fundamentally slippery character of the ‘market’ itself. Recent contributions have rightly cautioned against critiques of neoliberalism that fetishise ‘the market’ as a social form (Cahill Citation2020, Copley and Moraitis Citation2020, Knafo Citation2020). ‘Markets’, as such, are neither neutral nor natural phenomena. They are not a default setting on economic activity that can be ‘disembedded’ from (or re-embedded in) social regulation. But the efficiency of abstract ‘markets’ as mechanisms for decision-making is a core principle underlying neoliberal interventions. As Mirowski (Citation2009) and others have noted, insofar as there is a core ‘neoliberal’ belief, then, it is that ‘prices in an efficient market ‘contain all relevant information’ and therefore cannot be predicted by mere mortals’ (Citation2009, p. 435), coupled with a growing recognition that markets themselves needed to be produced and engineered into being (see Nik-Khah and Mirowski Citation2019). This latter shift is a key point of difference between neoliberalism and neoclassical economics. In practice, as Neyland et al. (Citation2019) note, political efforts to mobilise or design markets invoke different, and not always consistent, logics – variously e.g. competition, quantification, exchange, discipline. Indeed, as the discussion below indicates, projects of marketisation often entail fundamental ambivalences around the basic objects of marketisation themselves. The point here is that if we want to get to grips with the trajectory of neoliberalism as a political project in global development, we need to think in concrete and historical terms about processes of marketisation – how markets are made – and about the limits to such processes of construction.

By the 1970s, the deregulation of agricultural credit was a prominent point of emphasis for neoliberal economists. The first versions of the ‘financial repression’ thesis (McKinnon Citation1973, Shaw Citation1973) were framed in no small part around arguments about how restrictions on interest rates inhibited access to credit for small farmers. McKinnon argued ‘Usury ceilings on the interest rates charged on bank loans have emasculated the ability and willingness of commercial banks to serve small-scale borrowers of all classes’ (Citation1973, p. 73). Similar views emphasising the distortionary harms of credit subsidies were shared (and published) by some economists within the Bank as well (e.g. Von Pischke Citation1978, Von Pischke and Adams Citation1980). Yet, the Bank’s formal position reveals considerably more ambiguity. Available, affordable credit was seen as a necessary input for market-based, privatised forms of agricultural development, intimately linked to mechanisation, modernisation, and increased productivity. The Assault on World Poverty report is a case in point. It framed access to agricultural credit as a key means of alleviating poverty. This was articulated in the context of a wider emphasis on building effective markets for agricultural goods: ‘credit facilities are … an integral part of the commercialisation of the rural economy’ (Citation1975a, p. 105). Ineffective markets for credit itself were also identified as an obstacle: ‘Capital and credit markets in developing countries are imperfect in varying degrees. As a consequence, interest rates may not allocate resources among competing uses as effectively as they should’ (Citation1975a, p. 109). Critically, though, as the discussion over the next three sections shows, the Bank was at the time still uncertain about how far credit itself could be delivered on market terms.

The point here is twofold. First, agricultural credit sat at the crux of a number of formative neoliberal debates. Second, efforts to promote agricultural credit were intrinsically linked to longer-run projects of commercialisation and marketisation in third world agriculture. Looking from this wider angle is revealing of significant and persistent ambivalence around whether credit itself could or should be delivered on market terms in practice. Debates about agricultural credit thus bear a closer look not simply in their own right, but for what they can tell us about the politics of marketisation and the historical rise of neoliberalism more generally. As I show in the empirical discussion that follows, if the Bank eventually steered in the direction of explicitly pushing for the marketisation and commercialisation of agricultural finance itself, it did so in large part through a process of trial and error, driven in no small part by operational concerns and various kinds of ‘quiet failures’ (to borrow Best’s [Citation2020] phrase) of agricultural credit projects to produce expected outcomes.

Mapping the Changing Composition of Agricultural Credit Projects

To carry out the following analysis, I collected all available project documents from World Bank agricultural credit projects. For each project, this included a staff appraisal report, a Presidential report and recommendation to the Executive Directors, as well as loan agreements. In most cases this also included a completion report or audit.Footnote2 The Bank effectively ceased lending for agricultural credit projects after 1990, so I have included only projects up to that point. In total, I examined available documents from 141 agricultural credit projects, in 44 countries, launched between 1960 and 1990, to which the Bank committed a total of USD 8.36 billion in nominal terms. This total includes projects explicitly targeting ‘agricultural credit’ as well as closely related activities including ‘rural credit’ and credit for aquaculture, livestock, and fisheries. I have included all projects where the support or creation of lending facilities for agriculture, or these related activities, was the main focus of the project.Footnote3 As noted in the introduction, one consequence of this approach is that this article can reveal much more about the internal debates at the Bank rather than relationships between the Bank and borrowers.

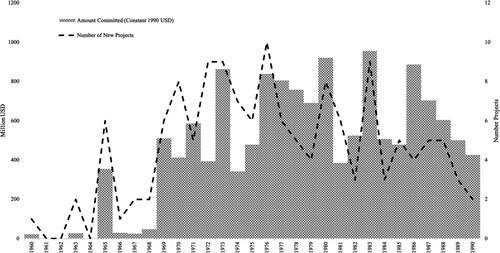

shows the number of projects annually and new funds committed in constant 1990 USD from 1960 to 1990. The Bank’s first agricultural credit projects were actually launched in the decade prior – with loans to finance the import of agricultural capital goods to Peru in 1954 and 1957 – but the expansion of agricultural credit programmes elsewhere began in earnest in the mid-1960s, so I have focused on post-1960 projects in the following analysis. Here, as well as in the following sections, the analysis focuses on new commitments in a given year, rather than actual disbursements (the latter were normally spread over several years and hence would have been somewhat smoother than the chart below). This is simply because the aim is to track the development of the Bank’s policy, and most relevant policy measures were generally agreed during appraisal and negotiations.

Figure 1. Number of new World Bank agricultural credit projects, and new funds committed, in constant 1990 USD (millions), 1960–1990; source: author.

There were important changes over time in the scope and definition of these projects. The earliest projects were primarily focused on providing credit to large commercial farmers. Into the 1970s, as the Bank increasingly focused on poverty, projects started to include targets around lending to small farmers (World Bank Citation1976a: s2). But projects also shifted in significant ways with respect to how credit was priced and distributed. In the following two sections, I explore these shifts through an analysis of the credit pricing and distribution mechanisms embedded in these projects, as well as a close reading of the way these conditions were framed, especially how problems were identified and responded to. In what follows, I show how these shifts were negotiated and rationalised. Through these shifts, we can start to see how the Bank’s turn to ‘ground-clearing’ neoliberalism in the 1980s and 1990s was both a continuation by other means, and ran alongside, these longer processes of agricultural marketisation and commercialisation.

Fixing Interest Rates

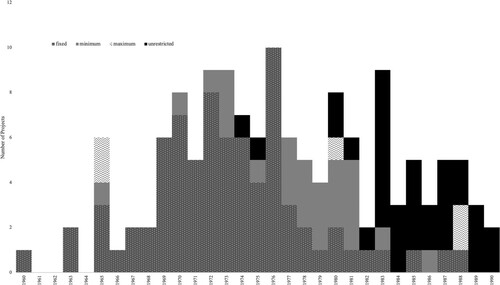

Interest rates, as noted above, were a key emphasis of neoliberal economists, and also an increasingly fraught practical question for the World Bank. shows how the borrowing conditions for farmers attached to the Bank’s agricultural credit projects changed over time. The categories used in the figure are outlined in – the terminology is my own as the Bank never adopted a consistent one. Projects with ‘fixed’ interest rates had specific rates of interest for final borrowers set in project documents. ‘Maximum’ rates refer to ceilings on the rates of interest that could be charged. ‘Minimum’ rates to projects fixed floors below which rates were not allowed to drop, but permitted raising rates. ‘Unrestricted’ interest rates included no limits on how high or low rates could fluctuate. In most of these cases, rates indexed to a specified variable. These differed from minimum rates in including specified criteria by which rates were to be adjusted, generally dependent on factors external to the project (typically commercial banks’ average cost of funds or various measures of inflation). In many cases these conditions reflected interest rate conditions prevailing in law or regulation in the country in question, but as will be seen further below, even from the earliest projects the Bank often tried to use agricultural credit projects to encourage reforms.

Table 1. Definitions of credit pricing categories; source: author.

We can make out a clear trend away from fixed interest rates over time. Up to 1976, the vast majority of projects included fixed rates – 63 of 74 total projects (see ). Frequently the Bank, concerned about the financial viability of project partners, did seek to encourage project partners to increase rates for farmers in these projects. In negotiations around a 1968 project in Pakistan, for instance, the Pakistani Agricultural Development Bank (ADBP) agreed to bring rates on long-term loans in line with rates for short- and medium-term loans at 7 percent annually, ‘to help improve the financial operations’ of the ADBP (World Bank Citation1968, p. 8). The Bank’s formal sectoral policy on Agriculture, published in 1972, reflected some initial concerns about subsidised interest rates, noting in particular that interest rate subsidies, particularly in conjunction with stringent collateral requirements, would predominantly benefit larger farmers with ready access to formal credit (World Bank Citation1972, p. 43). In 1974, the Bank published an official policy on agricultural credit, concluding that ‘the Bank should be working towards a long run objective of positive interest rates reflecting costs of lending; an intermediate objective might be to cover at least the opportunity cost of capital’ (World Bank Citation1974, p. 9). This was echoed in the Bank’s policy paper on rural development the following year (World Bank Citation1975b, p. 30). Critically, in this formulation fixed rates were still the norm, and insofar as this policy envisioned debates during project negotiations about interest rates, the emphasis was on what rates should be specified.

Figure 2. World Bank agricultural credit projects by interest rate conditions, 1960–1990, see for category definitions; source: author.

This started to change as the results of earlier projects showed a recurrent problem with fixed interest rates that turned out to be negative in real terms because of high inflation in project countries. It was a question of growing concern for Bank officials that a number of projects seriously strained the finances of project participants, especially when these were agricultural development banks which were generally meant to be self-financing. In Gujarat, India, for instance, a project evaluation concluded that, because the rate of inflation exceeded the rate of interest on project loans, the project had enabled borrowers, mostly large farmers with access to commercial credit elsewhere, to gain access to very cheap credit, while heavily decapitalizing the project partner. The latter had ‘thus subsidized them, at the expense of its own balance sheet’ (World Bank Citation1976b, p. 9). A major review of agricultural credit projects completed in 1976 likewise concluded that across most of the projects examined ‘the structure of interest rates imposed by the programme and by the financial system in which it operates not only subsidises the farmer but threatens the viability of the channel and forces it to act in a manner contradictory to the purposes of the project’ (World Bank Citation1976a, p. 70). The review, notably, was explicit in emphasising, not so much the effect of subsidies on borrowers or the credit-allocation effects of subsidies, ‘but the effect the interest rate and cost structure has on the participating institutions.’ (Citation1976a, p. 70).

Projects in the latter part of the 1970s initially either sought to resolve this issue in one of two ways: by setting minimum interest rates, or by linking fixed rates directly to projected rates of inflation over the term of the project. In practice, these policies did not often have the desired impact. Simply establishing fixed rates based on projected inflation dependended on predictions which often turned out wrong in unstable macroeconomic conditions. Interest rates on a project in Ecuador in 1977, for instance, had been set at 11 percent per annum for ‘small farmers’, and 14 percent for other end-borrowers, levels explicitly justified because they were seen as ‘likely to be positive over the long term if, as expected, the anti-inflationary policies adopted since 1975 continue to be successful’ (World Bank Citation1977, p. 12). The evaluation of the completed project would note that project funds were used up because the legal documents around the loans had made no provisions for adjusting interest rates once faced with higher-than-expected inflation (World Bank Citation1988a: v).

The other initial response to this problem was setting minimum rates. For a brief period between 1977 and 1981, the majority of new projects (16 of 29) employed minimum rates (see ). In practice, without specific criteria for when or how rates should be raised, resistance to raising rates from governments worried about the potential political consequences often prevented credit prices being raised above the floors set in project documents. In a project in Pakistan launched in 1979, the Bank raised concerns during negotiations that interest rates were both too close to the rate of inflation and set at a level that gave the ADBP an insufficient spread over its own cost of funds to build up reserves. Minimum rates set at prevailing rates (then 11 percent annually) were a compromise agreed by the Bank when the Pakistani government refused to consider higher rates (World Bank Citation1979a, p. 14). Indeed, it’s a sign that the Bank’s priorities here had more to do with the balance sheet of project partner banks than with allowing the market to work that the compromise Bank officials subsequently required from the Government was to cut the rate it charged the ADBP, allowing the ADBP a profitable spread.

In this context, the increasing turn to various kinds of unrestricted ‘market’ based pricing mechanisms in the latter part of the 1980s, reflected in , was in no small part a reaction to the failures of projections aimed at achieving positive real rates, or minimum rates adopted in the absence of clear procedures for raising rates. Yet, the politically sensitive nature of interest rates to farmers could derail efforts to implement ‘market’-based rates as well. For instance, in Peru a 1983 project included an agreement to align interest rates to an average of commercial bank rates, as well as ensure that rates were indexed to inflation – this agreement was broken in practice after a change of government in 1985, and the project was eventually cancelled with about a third of project funds undisbursed (World Bank Citation1990a: ii).

Figure 3. Credit distribution structures of World Bank agricultural credit projects, 1960–1990; source: author.

It’s important to note that the move to unrestricted interest rates was driven as much by pragmatic concerns as by any ideological preference for ‘market’ rates. India is a useful counter-example in this respect. Projects in India did not follow the general trend toward unrestricted rates, but the Bank generally kept lending as long as the project partner, the Agriculture Rediscount and Development Corporation (ARDC) remained in good financial shape. Apart from the Gujarati project discussed above, low inflation had broadly kept project interest rates positive through a series of projects in the 1970s and early 1980s and the Bank did not pressure the government to alter its system for setting rates in agricultural credit. As inflation rose in the late 1980s, though, the Bank tried unsuccessfully to pressure the Indian government to raise rates: ‘The situation changed [in the late 1980s], when inflation rates reached double digits for the first time (in those two decades) and Government refused to raise interest rates to the extent needed to compensate for the inflationary effect’ (World Bank Citation1993a, pp. 2–3).

By the late 1980s, the Bank's pre-occupation with interest rates itself started to come in for criticism in project evaluations. In Thailand, the evaluation of a 1980 project noted that the Bank’s strong emphasis on raising rates as a way of ensuring the financial sustainability and expanded lending capacity of the partner bank had ‘reduced any incentives’ to either government on the Thai Bank for Agriculture and Agricultural Credit ‘to encourage growth in domestic deposits’ (Citation1988b, p. 13) as well as inhibiting wider financial sector reforms. In Zimbabwe, the evaluation of a 1982 project for small farmers, which had included provisions indexing interest rates directly to prime commercial rates, but also allowed the government to guarantee losses made by the Agricultural Finance Corporation, likewise noted that ‘The principle of not subsidizing farmers’ interest rates so as to provide them with the right cost signals, as well as to provide the credit institution with sufficient independent revenue, seems inconsistent with then demolishing the earnestness of the business relationship between farmer and credit institution by providing that government will pick up any bad debts and operating costs’ (World Bank Citation1990b: vi). As demonstrated further in the following section, the Bank’s conception of the marketisation of credit began to embrace a wider range of concerns reaching beyond marketising the pricing of credit itself, stretching into the commercialisation of agricultural financial institutions, and the introduction of more competition in rural lending.

The point here is that ongoing controversies around interest rates reflect both the growing turn to ‘market’ finance mechanisms and the ambivalent and politically contested character of that shift. Negative real interest rates, or simply rates that weren’t high enough to cover lending costs, were a common operational problem in agricultural credit projects. The Bank increasingly sought to raise rates or introduce more flexible systems. Initial efforts to build in more flexibility by prescribing minimum rates often failed because they lacked clear mechanisms for raising rates above the minimum. The move to more explicitly ‘market-based’ rates – whether negotiated between lenders and borrowers or indexed to inflation or cost of funds – reflected as much these operational concerns as it did an ideological preference for markets. By 1989 Bank economists were arguing that, on subsidised credit to farmers ‘the record … is quite dismal’ (Braverman and Guasch Citation1989, p. 1). It was not always consistently followed through in practice by governments with competing political imperatives, which contributed to the Bank’s growing emphasis through the decade on wider forms of commercialisation and marketisation. In the first instance, then, the turn to ‘market’-like forms of credit pricing – while it took place alongside the broader period of structural adjustment – was tentative, contested, and driven by longstanding practical concerns as much as any broader ideological shift.

Reforming Agricultural Finance

Beyond pricing, we can also point to a series of shifts in the structures of credit distribution and intermediation adopted in the Bank’s agricultural credit projects. Here again the Bank’s agenda on agricultural credit dovetailed with the broader push for financial de-regulation in the 1980s, but shows how the latter both fit into a longer-standing project of marketisation and commercialisation of agriculture, and represented a series of practical trial and error interventions.

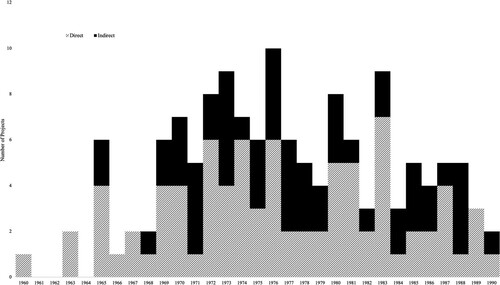

The breakdown of credit structures and project partners over time is reflected in . I divide projects into ‘direct’ and ‘indirect’ distribution structures. In the former case, the Bank lent money to a state-owned agriculture or development bank, which lent funds directly to participating farmers. In the latter, the bank lent money – most often to a central bank – to set up a fund which could be relent to commercial banks or used to rediscount eligible loans made by commercial banks. Virtually all projects did one or the other, although in a few rare instances the Bank funded projects that included elements of both. Over the entire period in question, 83 projects (or 58.8 percent of the total) were structured using direct on-lending, and 56 (39.7 percent) were indirect. In general, the choice of project structure was dictated at least in part by the agricultural lending institutions already in existence of the country in question. As shown in , this breakdown remained relatively consistent over time. The Bank nonetheless demonstrated somewhat of a growing preference for indirect structures after about 1980. A few national projects were re-structured at renewal to give a greater emphasis on re-lending through commercial partners, or to study the possibility of doing so, rather than directly to farmers.

Nonetheless, the Bank’s growing emphasis on commercialising agricultural financial institutions and marketizing financial systems is clearer when we look in more qualitative terms at specific project contents – including (1) an increasingly prevalent concern with reforming project partner banks along explicitly commercial lines, as well as (2) increasing emphasis on agricultural credit projects as vehicles for wider sectoral reforms. I take each of these dynamics up in turn in the next two sub-sections. As with the adoption of unrestricted interest rates on most projects, (1) the incorporation of institutional reforms into agricultural credit projects was driven by operational concerns as much as by any ideological programme, and (2) the Bank’s efforts to encourage institutional reforms were piecemeal and proceeded through trial and error, often revolving around efforts to identify both the relevant objects of marketisation and viable means of engineering markets.

Reforming Intermediaries

An explicit objective of many direct lending programmes from the mid-1970s onwards was the reform of agricultural credit institutions along more explicitly commercial lines. Given that state-backed agricultural banks were often established to provide forms of credit that commercial banks were generally not interested in providing, there was always some degree of tension here. Critically, this was a long-unfolding concern, and the intensification of efforts to commercialise agricultural bank operations after about 1980 was a reflection of long-running trends as much as a sudden conversion to neoliberalism. Here again, operational concerns and ‘quiet failures’, particularly around the growing pressure put on partner institutions by arrears and overdues across a number of projects, were important drivers. Perhaps the most dramatic example here is from Pakistan. After a backing three projects with the ADBP in 1965, 1968, and 1969, the Bank refused to consider multiple proposals for a fourth project for ten years after the ADBP fell into serious difficulties with overdue loans. The Bank’s diagnosis of these problems, as elsewhere, focused on perceived political interference with ADBP lending, particularly the Government of Pakistan’s reliance on ‘emergency lending’ through ADBP to respond to droughts and natural disasters:

In part, these problems have stemmed from the fact that ADBP has been used from time to time as an instrument for implementing welfare-type programs on behalf of GOP. These activities, particularly so-called “emergency lending,” have generally been incompatible with sound banking practice … ADBP's record of recoveries from emergency loans has been poor and such lending has tended to reduce credit discipline, impair staff motivation, and generally to affect ADBP's financial position adversely (World Bank Citation1979b, p. 10)

Efforts at institutional reform nonetheless sat awkwardly, at times, with objectives linked to agricultural productivity. This proved to be an especially controversial problem because the latter goals were often much more concrete, immediate, and of considerably more salient concern to borrowing governments. An audit of a 1972 programme in Kenya, was typical of this reckoning in noting that: ‘Targets for the institutional development of the intermediary tend not to be stated in terms which may be precisely quantified for purposes of financial analysis, although the general objective is to ensure that such intermediaries operate on a self-supporting basis according to normal commercial standards’ (World Bank Citation1979c, p. 4). Equally, the Bank started to recognise that there was relatively limited leverage that could be exercised through standalone agricultural credit projects with respect to political interference with the lending objectives and interest rates of state-backed banks and cooperatives agencies. In Senegal, a 1981 audit (notably, conducted shortly after the first structural adjustment loans in the country) of a 1973 project would concede that ‘with a single agricultural credit project as its only lever, it was not able to make more than a slight dent in this enormous institutional problem, which had been grossly underestimated at appraisal time’ (World Bank Citation1981a, p. 6). Redoubled efforts at reforming intermediaries were thus, in no small part, also responses to failures to revise interest rate structures in the previous decade.

Institutional reforms to state-backed lenders, to increase their operational autonomy and reform operations along explicitly commercial lines, were thus increasingly a major component of most ‘direct’ lending projects adopted after about 1980 in particular. Sometimes this took the form of support for developing the mundane infrastructures of banking activity. Some projects included funds for, among other things, staff training, computer systems, accounting software, vehicles, and upgrades to headquarters or branch buildings. More often, projects introduced conditionalities related to loan recoveries and amendments to loan appraisal procedures in an effort to improve recovery rates. The reforms to interest rates above, aimed at ensuring credit to small farmers was made on profitable terms, were also closely related. By the 1980s these direct lending projects were often understood, sometimes explicitly so, as stepping stones towards the development of project structures that would involve commercial banks, or the independent development of private financial markets – a 1983 project in Thailand, based around direct on-lending by the state-owned Bank for Agriculture and Agricultural Cooperatives, for instance, was explicitly described as an ‘interim step’ towards the development of a rediscount facility at the Central Bank which would support wider commercial lending for agriculture (World Bank Citation1983a, p. 12)

Yet the Bank nonetheless remained ambivalent about how far, precisely, agricultural credit – especially longer-term credit for mechanisation or land development, rather than seasonal loans for inputs – could be delivered on purely market terms. Efforts to expand direct onlending projects to include commercial banks had mixed impacts and often failed. The Bank’s tentative efforts to involve commercial banks directly in the revived Pakistani project in 1979, for instance, were abandoned in the follow-up project explicitly because commercial banks remained ‘mainly focussed on short-term lending’ (1983b: 19). A 1983 project in Peru was meant to include a study on how to set up a rediscount facility accessible to commercial lenders to accompany lending through the national agricultural bank, but the study was simply never completed (World Bank Citation1990a). In Kenya, officials concluded in 1991 that although previous projects had been unsatisfactory and the Bank would not plan any follow-up loans, ‘There is really no alternative to [the government-owned Agricultural Finance Company], for the foreseeable future … Privatisation is a futile proposition, given Government's rejection and in light of the indifference of the commercial banks to replacing AFC’ (Citation1991b, p. 24 [Kenya Audit]). There were equally growing concerns that support for state-backed lenders, even if geared to promote the commercialisation of those institutions, might inhibit the development of competitive private credit markets. In Morocco, an audit in 1992 suggested that:

there is little indication that the World Bank Group is actively encouraging greater participation by financial institutions other than [Caisse Nationale de Credit Agricôle (CNCA)] in rural finance. The Bank could, for example, encourage commercial banks to compete for CNCA's most creditworthy clients by ensuring that CNCA does not offer below-market rates to these clients, and by supporting technical assistance for commercial banks to increase their expertise in agricultural lending or encouraging their use of CNCA training. (World Bank Citation1992a, p. 24)

Conditional Agricultural Lending and Structural Reforms

Agricultural credit projects continued to be negotiated alongside structural adjustment loans, and were framed as means of supporting, or driving wider sectoral reforms in many instances. The usefulness of these projects as means of compelling policy adjustments was, however, limited in practice. The Bank increasingly viewed narrow sectoral projects, particularly those focused on a single institution, as less efficient instruments for prompting policy reforms. Whether this assessment was accurate is perhaps somewhat doubtful given that structural adjustment packages were in general typically only partially implemented (see Woods Citation2006), but it nonetheless strongly shaped the Bank’s eventual abandonment of agricultural credit lending. This was, to some extent, a concern with a longer pedigree dating to earlier efforts to reform intermediaries. The Senegalese evaluation noted above is one example (World Bank Citation1981a). Similarly, a report on a series of projects in Costa Rica in the early 1970s, for instance, noted that the scale of lending had simply been too small in relation to overall agricultural lending in the country to compel the desired reforms to the loan appraisal procedures adopted by participating banks (Citation1981b, p. 6). But the concerns about whether agricultural credit projects had sufficient scope and scale to affect reforms was intensified as the Bank increasingly sought wider policy reforms alongside institutional commercialisation.

Project evaluations conducted by the late 1980s and early 1990s virtually all concluded that directed credit programmes were not effective instruments for compelling policy reforms. The evaluation of a 1989 project in Honduras would note that, ‘a sector-specific credit project, like this one for agricultural credit, is a weak instrument for addressing problems of financial intermediation in a subsector when the overall banking system is unsound’ (World Bank Citation1995a: v). Much the same was concluded of the much larger series of projects in India – the evaluation of the fourth loan to the ARDC would note that ‘The main lessons under ARDC IV (and indeed previous ARDC projects) has been that [ARDC] alone cannot bring about sustained or permanent improvements in policy and institutional environment for agriculture credit through its powers to sanction refinance facility’ (Citation1989a: vi). The point here is that, while agricultural credit projects had increasingly come to be seen as a means of reforming financial systems, the truncated progress of actual reforms was interpreted as a sign that targeted programmes were ineffective means of compelling reforms. In Yugoslavia it was concluded that a long-running ‘dialogue on interest rate policy in the context of these specific agricultural sector projects was ineffective and only started to become more effective when it was taken up under the structural adjustment discussion’ (World Bank Citation1988c: vii). The Bank equally worried that targeted credit interventions might in fact be forestalling the development of rural financial markets. The evaluation of a 1983 project in Honduras noted that: ‘Targeting credit operations to specific types of beneficiaries, at different rediscount and on-lending rates, has contributed to accentuating the existing rural financial market imperfections and segmentation’ (Citation1990c: v). There were also concerns that agricultural specialists, both within the Bank and national governments, were probably not the appropriate people to drive wider financial sector reforms. The 1988 audit of a Thai project made this explicit: ‘divisions whose primary focus is agricultural production, may not bring to bear on such operations the broader institutional and financial skills required to manage interventions in the financial sector properly’ (World Bank Citation1988d, p. 15).

One of the final agricultural credit projects run by the Bank is telling. After making six previous loans directly to the ADBP, the Bank shifted its approach to agricultural credit in Pakistan in a final project in 1990. The 1990 loan was made to the Pakistani government, rather than ADBP as in previous loans, and open for on-lending to farmers both by the ADBP and commercial banks (at the time, nationalised). It was explicitly intended to promote greater competition and the development of a self-sustaining market, and explicitly designed in conjunction with wider structural adjustment programming in Pakistan:

The proposed project aims at transforming the development of the agricultural credit system into a viable system that can meet the expanding needs of the agriculture sector and increase its productivity. Through further financial sector liberalization and progress in increasing competition among banks, the project would support the consolidation of the gains already made in strengthening agricultural credit. (World Bank Citation1990d, p. 3)

By the early 1990s, the Bank had decisively rejected agricultural credit projects. There is some irony here in that by the time the Bank had actually decisively abandoned the kind of targeted lending projects typical of the Assault on Poverty era in favour of broad-based policy-conditional lending, the broader rethinking of structural adjustment both within and outside the Bank was well underway. The ‘ground clearing’ of structural adjustment, in Sassen’s (Citation2010) terms, emerged out of, and was accompanied by, simultaneous but fraught efforts to engineer marketisation and commercialisation. Indeed, the Bank’s efforts to reckon with the failures of structural adjustment on its own terms in Africa, From Crisis to Sustainable Growth (World Bank Citation1989b) and Adjustment in Africa (World Bank Citation1994) were published alongside the more skeptical assessment of directed credit cited here. The prevailing diagnosis of the shortcomings of structural adjustment here largely emphasised failures to implement reforms and questions of governance. At the same time, the Bank’s response to the failures of structural adjustment also entailed a renewed emphasis on poverty reduction (see Best Citation2013).

It’s notable in this latter respect that the Bank had already started to embrace microcredit as a means of delivering wider access to credit for small and landless farmers by the late 1980s. There was some overlap with the last few agricultural credit projects here. In Malawi, a 1987 project included a pilot scheme explicitly modelled on the Grameen Bank in Bangladesh (World Bank Citation1987, p. 17). The Bank included a quite positive discussion of Grameen Bank in the 1989 World Development Report. This embrace of Grameen was explicitly a response to the recurrent concerns about agricultural credit programming, particularly around interest rates and repayment performance. The fact that Grameen Bank charged profitable interest rates and had loan recovery rates nominally as high as 97–99 percent, was strongly emphasised (World Bank Citation1989c, p. 117). There was never, in short, a period of time where structural adjustment was unambiguously embraced as the central means of promoting neoliberal development models in general, or where there was complete agreement on what exactly marketisation and commercialisation entailed in practice or how to bring them about.

Conclusion

The broadly neoliberal thrust of global development governance, seen through the lens of the agricultural credit projects discussed in this article, appears at once older and murkier than is often assumed. The broad thrust of the Bank’s programming, including in the ‘Assault on Poverty’ era in the 1970s, was defined primarily in terms of fostering the marketisation and commercialisation of agriculture. A close look at these programmes, however, reveals considerable ambivalence about just what ‘market-based’ agricultural systems entailed and how to bring them about. If ‘the market’ was indeed central to the Bank’s approach to agricultural development, and development more broadly, the concrete objects of marketisation nonetheless remained highly uncertain throughout. The core ambiguity around credit – whether access to credit was an external support to market development or needed itself to be delivered on market terms – highlighted in these agricultural credit projects is particularly telling. In the broadest sense, we can trace a shift at the Bank away from an emphasis on expanding access to credit as a means of facilitating productivity and marketisation towards an emphasis on marketizing the delivery and pricing of credit itself. But even here, this process was gradual, and driven by operational concerns as much as ideological ones. The Bank’s economists discovered that they needed to design or engineer markets into being (per Nik-Khah and Mirowski Citation2019), but also that doing so was politically fraught and riven with practical ambivalences.

This history should cast our understandings of structural adjustment and the neoliberalization of development governance in a slightly different light. In the first instance, the broad projects of marketisation and commercialisation underlying structural adjustment were implicit even in the ‘Assault on Poverty’ years, certainly as far as agriculture was concerned (cf. Mendes Pereira Citation2020). Second, situating structural adjustment in this longer context of the projects that ran before and alongside it shows us a lot about the politics of building markets. The Bank grappled through the period in question with the ambivalent place of credit in wider logics of marketisation and commercialisation. ‘Building markets’ for development entails significant ambivalences – who and what should be subject to market governance? On what terms?

Acknowledgements

Thanks to the anonymous reviewers at New Political Economy for their very helpful comments on an earlier version of this article.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Nick Bernards

Nick Bernards is Assistant Professor of Global Sustainable Development at the University of Warwick. He is author of The Global Governance of Precarity: Primitive Accumulation and the Politics of Irregular Work (Routledge, 2018), and A Critical History of Poverty Finance: Colonial Roots and Neoliberal Failures (Pluto Press, forthcoming).

Notes

1 A frequent target of early neoliberals’ critical attention, see Bair (Citation2009).

2 As the Bank established its Independent Evaluation Group in 1973, the results of most projects launched before about 1970 were not formally evaluated ex post.

3 The vast majority of these projects were national in scope, but in some instances there were projects targeted to particular provinces (notably, in ten Indian provinces between 1970 and 1973) and in some instances different projects targeting different classes of borrowers (e.g. livestock and small farmers, respectively) were run simultaneously.

References

- Bair, J., 2009. Taking aim at the new international economic order. In: P. Mirowski, and D. Plehwe, ed. The road from mont pèlerin: The making of the neoliberal thought collective. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 348–385.

- Bernstein, H., 1990. Agricultural “modernisation” and the era of structural adjustment: observations on sub-saharan Africa. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 18 (1), 3–35.

- Best, J., 2013. Redefining risk as poverty and vulnerability: shifting strategies of liberal economic governance. Third World Quarterly, 34 (1), 109–129.

- Best, J., 2016. When crises are failures: contested metrics in international finance and development. International Political Sociology, 10 (1), 39–55.

- Best, J., 2020. The quiet failures of early neoliberalism: from rational expectations to keynesianism in reverse. Review of International Studies, 46 (5), 594–612.

- Boeckler, M., and Berndt, C., 2013. Geographies of circulation and exchange III: The great crisis and marketisation “after markets”. Progress in Human Geography, 37 (3), 424–432.

- Braverman, A., and Guasch, J.L., 1989. ‘Rural credit in developing countries: issues and evidence’, world bank policy, planning, and research working papers. Washington: World Bank Group.

- Brenner, N., Peck, J., and Theodore, N., 2010. Variegated neoliberalism: geographies, modalities, pathways. Global Networks, 10 (2), 182–222.

- Cahill, D., 2020. Market analysis beyond market fetishism. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 52 (1), 27–45.

- Christophers, B., 2014. From marx to market and back again: performing the economy. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences, 57, 12–20.

- Copley, J., and Moraitis, A., 2020. Beyond the mutual constitution of states and markets: the governance of alienation. New Political Economy. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2020.1766430.

- Fine, B., and Saad-Filho, A., 2017. Thirteen things You need to know about neoliberalism. Critical Sociology, 43 (4–5), 685–706.

- Gibbon, P., Havnevik, K.J., and Hermele, K., 1993. A blighted harvest: The world bank and african agriculture in the 1980s. London: James Currey.

- Harrison, G., 2010. Neoliberal Africa: The impact of global social engineering. London: Zed Books.

- Harvey, D., 2004. The “New” imperialism: accumulation by dispossession. Socialist Register, 40, 63–87.

- Knafo, S., et al., 2019. The managerial lineages of neoliberalism. New Political Economy, 24 (2), 235–251.

- Knafo, S., 2020. Rethinking neoliberalism after the polanyian turn. Review of Social Economy. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00346764.2020.1733644.

- Lal, D., 2002. The poverty of ‘development economics’. London: Institute for Economic Affairs.

- McKinnon, R.I., 1973. Money and capital in economic development. Washington: Brookings Institute.

- Mendes Pereira, J.M., 2020. ‘The world bank’s “assault on poverty” as a political question’. Development and Change, 51 (6), 1401–1428.

- Mirowski, P., 2009. Postface: defining neoliberalism. In: P. Mirowski, and D. Plehwe, eds. The road from mont pellerin: The making of the neoliberal thought collective. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 417–456.

- Neyland, D., Ehrenstein, V., and Milyaeva, S., 2019. On the difficulties of addressing collective concerns through markets: from market devices to accountability devices. Economy and Society, 48 (2), 243–267.

- Nik-Khah, E., and Mirowski, P., 2019. On going the market one better: economic market design and the contradictions of building markets for public purposes. Economy and Society, 48 (2), 268–294.

- Peck, J., 2010. Constructions of neoliberal reason. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Plehwe, D., 2009. The origins of neoliberal economic development discourse. In: P. Mirowski, and D. Plehwe, ed. The road from mont pèlerin: The making of the neoliberal thought collective. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 238–279.

- Rojas, C., 2015. The place of the social at the world bank (1949–1981): mingling race, nation and knowledge. Global Social Policy, 15 (1), 23–39.

- Sassen, S., 2010. A savage sorting of winners and losers: contemporary forms of primitive accumulation. Globalizations, 7 (1-2), 23–50.

- Shaw, E.S., 1973. Financial deepening in economic development. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Soederberg, S., 2017. Universal access to affordable housing? interrogating an elusive development goal. Globalizations, 14 (3), 343–359.

- Toye, J., 1993. Dilemmas of development: reflections on the counter-revolution in development economics. London: Blackwell.

- Tun Wai, U., 1957. Interest rates outside the organized money markets of underdeveloped countries. Staff Papers - International Monetary Fund, 6 (1), 80–142.

- Van Waeyenberge, E., 2018. Crisis? what crisis? A critical appraisal of world bank housing policy in the wake of the global financial crisis. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 50 (2), 288–309.

- Von Pischke, J.D., 1978. When is smallholder credit necessary? Development Digest, 16 (3), 6–14.

- Von Pischke, J.D., and Adams, D.W., 1980. Fungibility and the design and evaluation of agricultural credit projects. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 62 (4), 719–726.

- Woodhouse, P., 2003. African enclosures: a default mode of development. World Development, 31 (10), 1705–1720.

- Woods, N., 2006. The globalizers: The IMF, the World Bank, and their borrowers. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- World Bank, 1968. Second credit of agricultural development bank, Pakistan. Washington: World Bank Group.

- World Bank, 1972. World bank operations: sectoral programmes and policies. Washington: World Bank Group.

- World Bank, 1974. Bank policy on agricultural credit. Washington: World Bank Group.

- World Bank, 1975a. The assault on world poverty. Washington: World Bank Group.

- World Bank, 1975b. Rural development: sector policy paper. Washington: World Bank Group.

- World Bank, 1976a. Operations evaluation report: agricultural credit programmes, Vol. II, analytical report. Washington: World Bank Group.

- World Bank, 1976b. Project performance audit report: gujarat agricultural credit project (credit 191-IN). Washington: World Bank Group.

- World Bank, 1977. Report and recommendation of the president of the international bank for reconstruction and development to the executive directors on a proposed loan to the republic of Ecuador for an agricultural credit project. Washington: World Bank Group.

- World Bank, 1978. World development report, 1978. Washington: World Bank Group.

- World Bank, 1979a. Pakistan: staff appraisal report, fourth credit for the agricultural development bank. Washington: World Bank Group.

- World Bank, 1979b. Report and recommendation of the president of the international development association to the executive directors on a proposed credit to the islamic republic of Pakistan for a fourth agricultural development bank project. Washington: World Bank Group.

- World Bank, 1979c. Project performance audit report: Kenya - second smallholder agricultural credit project (credit 344-KE). Washington: World Bank Group.

- World Bank, 1980. Accelerated development in sub-saharan Africa: an agenda for action. Washington: World Bank Group.

- World Bank, 1981a. Project performance audit report: Senegal - second agricultural credit project (credit 404-SE). Washington: World Bank Group.

- World Bank, 1981b. Project performance audit report: Costa Rica - second agricultural credit project (loan 827-CR). Washington: World Bank Group.

- World Bank, 1983a. Report and recommendation of the president of the international bank for reconstruction and development to the executive directors on a proposed loan in an amount equivalent to US$ 70 million to the bank for agriculture and agriculture cooperatives with the guarantee of the kingdom of Thailand for the second agricultural credit project. Washington: World Bank Group.

- World Bank, 1987. Staff appraisal report: Malawi - smallholder agricultural credit project. Washington: World Bank Group.

- World Bank, 1988a. Project completion report: Ecuador, agricultural credit project (loan 1459-EC). Washington: World Bank Group.

- World Bank, 1988b. Project performance audit report: Thailand, agricultural credit project (loan 1816-TH). Washington: World Bank Group.

- World Bank, 1988c. Project performance audit report: yugoslavia - third agricultural credit project (loan 1801-YU). Washington: World Bank Group.

- World Bank, 1988d. Project performance audit report: Thailand - agricultural credit project (loan 1816-TH). Washington: World Bank Group.

- World Bank, 1989a. Project completion report: India - fourth agricultural refinance and development corporation project (ARDC IV) (loan 2095-IN/credit 1209-IN). Washington: World Bank Group.

- World Bank, 1989b. Sub-Saharan Africa: from crisis to sustainable growth: A long-term perspective study. Washington: World Bank.

- World Bank, 1989c. World development report 1989: financial systems and development. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- World Bank, 1990a. Project completion report: Peru, sixth agricultural credit project (loan 2302-PE). Washington: World Bank Group.

- World Bank, 1990b. Project performance audit report: Zimbabwe, small farm credit project (credit 1291-ZIM). Washington: World Bank Group.

- World Bank, 1990c. Project completion report: Honduras - third agricultural credit project (loan 2284-HO). Washington: World Bank Group.

- World Bank, 1990d. Memorandum and recommendation of the president of the international bank for reconstruction and development to the executive directors on a proposed loan in an amount equivalent to US$ 148.5 million and a proposed credit in an amount equivalent to US$ 1.5 million to the islamic republic of Pakistan for an agricultural credit project. Washington: World Bank Group.

- World Bank, 1990e. Staff appraisal report: Pakistan - agricultural credit project. Washington: World Bank Group.

- World Bank, 1991b. Project performance audit report: Kenya - fourth agricultural credit project. Washington: World Bank Group.

- World Bank, 1992a. Performance audit report: Morocco - fifth and sixth agricultural credit projects. Washington: World Bank Group.

- World Bank, 1993a. Performance audit report: India, NABARD credit project (loan 2653-IN). Washington: World Bank Group.

- World Bank, 1994. Adjustment in Africa: reforms, results, and the road ahead. Washington: World Bank Group.

- World Bank, 1995a. Project completion report: Honduras - fourth agricultural credit project (loan 2991-HO). Washington: World Bank Group.

- World Bank, 1997. Implementation completion report: Pakistan - agricultural credit project (loan 3226-PAK/credit 2153/PAK). Washington: World Bank Group.