ABSTRACT

In times of crisis, governments can resort to tax rises and emergency taxation schemes to finance extraordinary needs. These schemes often generate tensions in the fiscal contract between the state and society, as they affect basic definitions regarding who is taxed, for how much, and what for. In the context of developing economies, where available sources of extraordinary rents are limited, dealing with these tensions can be problematic as it involves reconciling questions of fiscal legitimacy with the interests of influential economic sectors. This article analyses these tensions by exploring the case of Argentina in the aftermath of the 2001 debt default crisis, when emergency taxes on agricultural exports were implemented and then expanded under Kirchnerist administrations pursuing a ‘post-neoliberal’ developmental agenda. However, we argue that the government failed in legitimating this fiscal agreement, resulting in a tax rebellion by the rural sector in 2008 followed by the growing polarisation of the policy in partisan terms. By bringing to the fore the challenges and conflicts involved in legitimating tax collection, the article illuminates an overlooked aspect of the political economy of developmental states, particularly those seeking to enhance state autonomy while pursuing redistributive goals.

Introduction

This article engages with an under-examined aspect both in the politics of taxation of developmental states and the political economy of developmental governance in Latin America, examining the legitimacy of tax collection schemes within post-neoliberal regimes seeking to increase state autonomy while combining growth, fiscal stability, and ‘some moderate forms of income redistribution within the context of capitalist economies’ (Grugel and Riggirozzi Citation2018, p. 551). Thus, while an extensive literature has noted how left-turn administrations during the 2000s increased taxes and redirected fiscal revenues to social welfare and state-building purposes, until recently the collection side of these agendas, and the conflicts associated with the capture and redistribution of fiscal revenues, has been left rather unattended (Weyland Citation2009, Mazzuca Citation2013, Mangonnet and Murillo Citation2020). Instead, this article extends assessments about the sustainability of these agendas by drawing insight from the field of fiscal sociology, where ‘tax policy stands as an index of social, political, and economic change’ (Martin et al. Citation2009, p. 26), and where a causal link is postulated between tax legitimacy, forms of state-society relations, and the capacity of the state (Moore Citation2004, Brautigam Citation2008, Levi et al. Citation2009).

To do so, the article engages with the case of agricultural export taxes in Argentina, known locally as retenciones impositivas (tax withholdings), which were implemented as part of an emergency fiscal package following the 2001 debt default crisis. These taxes were maintained and expanded under the left-wing governments of Néstor Kirchner (2003–07) and his wife Cristina Fernández de Kirchner (2007–15), referred to as CFK from here onwards, even after the country returned to pre-crisis economic levels by 2007. As a representative of the Latin American ‘pink tide’, these administrations saw these taxes as an integral part of a state-centric neo-developmentalist agenda aimed at strengthening the autonomy of the state in relation to global economic forces and local elites, by combining commodity exports and industrial promotion with welfare provision and political inclusion (Grugel and Riggirozzi Citation2012, Citation2018, Gezmiş Citation2018, Silva and Rossi Citation2018, Wylde Citation2018). However, this post-neoliberal conception of the relationship between state autonomy and export taxes suffered a substantive blow in 2008, when a new tax hike project culminated in a rural revolt that included a four month long lock-out of Buenos Aires city, the spread of mass protests from the countryside to urban centres, and a critical legislative defeat (Hora Citation2010).

Our argument is that the conflict around export taxes in Argentina can be explored in light of the structural difficulties faced by many developmental states when trying to legitimise collection schemes where fiscal pressure falls on a limited set of actors with surplus revenue to be captured (Evans Citation1995, Nem Singh Citation2018). In particular, we demonstrate that as Kirchnerist administrations shifted the logic of taxation from one of crisis and emergency to a more ambitious and long-term ‘hegemonic’ project aimed at ‘reclaiming the state’ (Grugel and Riggirozzi Citation2012, p. 6), which politically excluded rural representatives and favoured other social and economic actors, the scheme became subject to accusations of excessiveness and unfairness, first by representatives of the targeted agrarian sector, and later on by the political opposition. This resulted in the partisan polarisation of the tax policy and to its treatment by opposition groups as a policy serving the interests of the ruling party, and contributed to block the ambition of Kichnerismo of making agricultural export taxes into a lasting feature of the Argentine developmental state – as most were swiftly removed when the conservative administration of Mauricio Macri (2015–19) came to power.Footnote1

This argument is developed in three sections. In the first two, we outline ideas of tax legitimacy and the challenge of tax legitimation in developing economies. The first section reviews conceptual arguments in the historical sociology of taxation where tax compliance is treated as measure of trust in the fiscal contract between public authorities and citizens, understood in terms of both vertical reciprocity and horizontal solidarity. Having done so, we examine how structural limitations regarding the availability of taxable resources in developing economies can make the legitimation of new fiscal models difficult and discuss alternative ways by which these developmental states may attempt to manage these problems. The third more substantive section unpacks the Argentine case, tracing in a qualitative and chronological manner the evolution of emergency taxation from the 2001 debt crisis to the aftermath of the agrarian revolt of 2008, with attention to the evolving context of application of agricultural export taxes, to the arguments wielded by government actors to justify their function and level, and to the evolution of discontent by rural and opposition actors.

This case is of scholarly relevance not only as Argentina has been under an emergency tax regime for almost two decades – with the new Alberto Fernández administration sanctioning a new Law of Economic Emergency upon assumption in December 2019 – but because taxes on agricultural exports are a central element of dispute between inward- and outward-looking strategies of development (Taylor Citation2018, Hora Citation2020). Moreover, the Argentine case allows us to study the renegotiation of a fiscal scheme in a context of crisis, which provides a convenient opportunity to study the ebbs and flows of fiscal legitimation. This is because crisis periods constitute critical junctures when governments enjoy a wider decision-making space, as citizens and interest groups may be better predisposed to accept exceptional measures, but also because post-crisis environments offer a test to evaluate the longer-term legitimacy attained by these measures. In this sense, as will be explained, this article not only contributes to expand arguments about the fiscal challenges faced by developmental states, both in the region and beyond, but brings attention to conflicts surrounding the sudden renegotiation of fiscal agreements, something of relevance in the context of the current COVID-19 pandemic as crisis support schemes will likely result in governments asking for extraordinary tax efforts.

Methodologically, the article triangulates qualitative and quantitative data from several sources to trace this process over time, including: secondary comparative politics and development literature of state-society relations in Argentina and Latin America during the left turn, literature on the economic history and political economy of taxation and public spending in Argentina, macro-economic and fiscal indicators extracted from government sources, international organisations, and universities, reports in the Argentine press and social media sources covering both government and opposition actors, and data from 36 semi-structured interviews with former government officials, tax experts, and representatives of rural organisations (some of which were anonymised upon request). The interviews were conducted by one of the authors during a period of three months in Buenos Aires during 2019, both in English and Spanish, and revolved around the logic, impacts, and challenges of emergency and extraordinary taxation during the 2003–15 period. Relevantly, we note that economic indicators of Argentina have to be considered with care, particularly after the national statistics institute INDEC was intervened by the government in 2007 (resulting in the first ever Declaration of Censure by the IMF due to data manipulation in 2013), with important variations existing between official, academic, and third-party publications. For this reason, certain key figures such as inflation and poverty were contrasted against unofficial estimates by reputable local entities.

Fiscal Legitimacy and State Embeddedness

The fundamental role of taxation in state-building has long attracted scholarly attention in the historical and fiscal sociology literatures, with Margaret Levi (Citation1988, p. 1) stating that ‘the history of state revenue production is the history of the evolution of the state’. At the same time, tax compliance, understood as the ability of the state to persuade or coerce citizens to comply with taxation, is widely seen as a measure of state capacity, a core link within a positive cycle where tax is needed to increase state autonomy – the state’s ability to pursue its own policy agenda independently of intra-national interests, especially of the dominant classes but also of partisan preferences – and chances of survival, and states need strong bureaucracies and agencies to have the capacity to collect tax (Skocpol Citation1979, Citation1985, Mann Citation1984, Tilly Citation1985, Acemoglu et al. Citation2015). Taxation emerges then as a principal metric of what the state can do, so that

A state’s means of raising and deploying financial resources tell us more than could any other single factor about its existing (and immediately potential) capacities to create or strengthen state organisations, to employ personnel, to co-opt political support, to subsidise economic enterprises, and to fund social programs. (Skocpol Citation1985, p. 17)

In general terms, theories of tax compliance can be distinguished between contractual or vertical ‘fiscal exchange’ models, and horizontal ‘political community’ ones (Von Haldenwang Citation2010, D’Arcy Citation2011). The former pose that taxpayer compliance increases when these expect the state to deliver certain services and public goods in return for revenue. A classic argument here is that representative government emerged as part of the democratic legitimation of the fiscal contract, which allowed the state to appear as ‘fairer’ vis-à-vis its citizens and collect more from more people (Levi Citation1988). At the same time, democracies are expected to tax more efficiently because they trade taxation for more inclusive forms of representation (Ross Citation2004, Bräutigam Citation2008). However, a caveat that follows from this argument is that ‘the more the state asks citizens to pay in taxes, the more that citizens will expect from government’, meaning that the state is expected to be more responsive to those sectors from whom it collects the more (Timmons and Garfias Citation2015, p. 14). This means that sectors controlling relevant resources also would expect to receive concessions and privileges in exchange for additional contributions, or, if these sectors see themselves shorthanded in the new fiscal arrangement, they could be expected to become less responsive and oppositional, something particularly problematic if they are influential and organised.

The second model poses that the willingness of citizens to pay taxes responds not only to the level of trust in the state or government, but on the level of horizontal solidarity existing among ‘tax citizens’. Accordingly, taxpayers would be willing to accept a higher tax burden if considering taxes benefits ‘in-groups’ in the political community, and tax systems that strengthen social cohesion and equality would be expected to enjoy higher levels of legitimacy (Lieberman Citation2001, D’Arcy Citation2011). This notion decants into what is known as the ‘solidarity hypothesis’ in relation to welfare states, which considers that social heterogeneity strains political possibilities in terms of redistribution policies, as it requires extending sympathy to outsider welfare recipients – something observed in Scandinavian countries, where the high trust characterising these highly ethnically-homogenous societies is often not extended to migrant communities and requires active policies from the state (Ervasti and Hjerm Citation2012).

Considered in combination, we can draw two analytical challenges regarding fiscal legitimacy to be expected when emergency fiscal needs result in governments targeting certain sectors or groups. First, the idea of fiscal reciprocity poses that legitimacy and subsequent compliance follow from a high degree of negotiation with potential taxpayers, with the state gaining their trust and achieving consensus on what constitutes a ‘fair’ revenue production policy (Sánchez Román Citation2012). This means that if a new tax production policy was to be implemented suddenly and without an explicit renegotiation of the fiscal constitution, the fairness of the tax would be less consolidated and more open to contestation by the affected sectors. These challenges are to be anticipated around emergency taxes, which are often implemented with limited consultation and through executive action, while routine fiscal policy tends to be the preserve of the legislative branch. Second, while some aspects of tax compliance may improve during an economic crisis (as a reduction in income may lower some people’s incentives to evade), in general sectors more impacted by the crisis are expected to have an incentive to lower compliance (Brondolo Citation2009). This can trigger problems of horizontal solidarity across society, as generalised perceptions of higher evasion would stimulate a higher sense of unfairness between ‘contributing’ sectors that comply and those free-riding the system.

Here is where the argument by Evans (Citation1995) regarding how newly industrialising states gain autonomy to engage in high-quality economic transformation is still of relevance. Evans claimed that these states need to generate strong ‘internal loyalties’ with influential economic actors and elite groups that share their transformative agenda in order to guarantee its continuation, seeking to ‘embed’ themselves by crafting ‘institutionalised channels for the continual negotiation and re-negotiation of goals and policies’ (Evans Citation1995, p. 59). The absence of these negotiating channels is what distinguishes developmental states that achieve some form of embedded autonomy in society, from predatory ones, like some African rentier states, which extract resources through undisciplined internal structures and clientelist exchange relations, promoting a disorganised civil society ‘incapable of resisting predation’ (Ibid., p. 72).Footnote2 At play in this is how state elites can better assure the continuity of a particular developmental project or policy line and achieve certain ‘socially desirable’ public goods, decoupling this continuity from short-term interests, such as partisan or interest group preferences, but also circumstantial increases in government’s political power or changing external economic conditions (Cingolani et al. Citation2015). Legitimacy emerges then as a major mechanism to achieve state autonomy, albeit states can build legitimacy upon different foundations, for example, by adhering to certain constitutional principles, promoting particular ideological doctrines, or delivering certain fundamental public goods, such as economic wealth or territorial defence (Yang and Zhao Citation2015).

A relevant theoretical and methodological clarification is needed at this point. In line with new fiscal sociology ideas, our model approaches fiscal legitimacy and compliance as a relational and societal outcome reflecting not only institutional configurations and the interests of social and economic actors, but the effect of ‘informal social institutions’ on actors perceptions and judgements – such as patterns of public trust, cleavages of political conflict, and cultural expectations in terms of work, consumption, political performance, or procedural justice, among other issues – and how these articulate, often contentiously, in specific national contexts and historical moments (Levi et al. Citation2009, Martin et al. Citation2009, p. 13). As such, our approach differs from both more classical historical sociology approaches where taxation is associated with military competition and the development of war- and market-making capacities (Mazzuca Citation2021), but also from Marxian analyses considering the conditions of capital accumulation and appropriation of different types of agrarian ‘rents’ by industrial and landowning sectors.Footnote3

As explained ahead, while much of the literature covering the political economy of left-wing Latin American governments during the 2000s made similar arguments regarding enhanced state autonomy and social embeddedness, questions about the legitimacy of fiscal arrangements from the perspective of those targeted by them were largely left unattended. This resulted in redistributive and political tensions associated with growing fiscal burdens being underplayed, particularly when these were accompanied by improving social indicators and high electoral popularity. The section ahead briefly examines these arguments in relation to the fiscal contract tensions to be expected in Latin American economies.

The Challenge of Tax Legitimacy in Latin America

The notion of post-neoliberal governance framed the agendas of Latin American left-wing administrations in the 2000s as one of balancing the ‘social responsibilities of the state while remaining responsive to the demands of “positioning” national economies in a rapidly changing global economy’ (Arditi Citation2008, Rovira Kaltwasser Citation2011, Sandbrook Citation2011, Grugel and Riggirozzi Citation2012, p. 4, Nem Singh Citation2014, Stoessel Citation2014, Wylde Citation2016). With their specific particularities, projects in countries like Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Ecuador, Venezuela, and others, were seen as pursuing higher forms of social embeddedness and inclusive development, simultaneously expanding the state’s developmental role by channelling rents from the exports of primary commodities – benefiting from the global commodity boom of the early 2000s when the expansion of large emerging market economies like China and India drove the increase in prices of oil, metals, and agricultural products (Nem Singh Citation2014, Balakrishnan and Toscani Citation2018).Footnote4 However, whilst this literature recognised that ‘social spending was paid for by taxation’ (Grugel and Riggirozzi Citation2018, p. 53), the emphasis of most of these analyses remained on the redistribution of this public spending to welfare and poverty reduction, and on the sustainability of these projects given their reliance on exporting a small portfolio of natural resources to volatile global markets (Grugel and Riggirozzi Citation2012, p. 13, Silva Citation2018, p. 324).

We claim, however, that the viability of the post-neoliberal fiscal contract needs also to be discussed from the perspective of tax legitimacy on the collection side, and in light of the political barriers and conflicts that emerge due to the particular tax structure of many Latin American economies.Footnote5 In line with Von Haldenwang (Citation2008, p. 2), we therefore see three structural factors shaping fiscal legitimation tensions in Argentina and the region. First, as mentioned before, compared to OECD countries taxation in this region is concentrated on a narrow pool of individuals and sectors with excess income to be captured. Thus, while developed economies draw fiscal revenues from the income of their citizens and businesses, Latin American countries put a heavier burden on consumption and economic activity, representing half of their fiscal take in comparison to a third in the OECD (OECD Citation2020, pp. 47–48). For this reason, taxes on international trade, which in Latin America provided 10.9 per cent of tax revenues in 2001 (and 17.6 per cent a decade earlier) are marginal in OEDC economies (Gómez Sabaíni et al. Citation2016, p. 207). Second, the quality of what contributors’ ‘purchase’ with their taxes in developed economies in terms of public goods and services is higher, and the ‘government waste’ and negative externalities (i.e. corruption, bureaucracy) is lower. Latin American countries, on the other hand, are characterised by low collection efficiency and high evasion, and have productive structures with less added value. This, on the one hand, justifies a greater use of indirect taxes levied on goods and services. On the other, this situation means that despite a higher tax burden on products and services, the revenue gained by Latin American countries as percentage of GDP is similar to the one of OECD countries (11.4 per cent vs 10.9 per cent respectively in 2017) (OECD Citation2020, p. 47). In other words, Latin American countries need to tax a smaller set of economic actors more, to get the same. Third, systemic governance in OECD countries is more transparent and more grounded in procedural legality, while in Latin America political authority is more vertical, and often heavily centralised in the executive branch – with most constitutional arrangements granting presidents significant emergency and decree powers, even over taxation matters (Malloy Citation1993, Cheibub et al. Citation2011).

These features create potential deficits in terms of vertical reciprocity and horizontal solidarity, a lower ‘tax morale’ (Daude and Melguizo Citation2010) that can be expected to translate into different cleavages of conflict during the operationalisation of new tax schemes, particularly when promoted by left-wing governments pursuing wealth redistribution. This is because these governments may seek to extract and/or redirect additional fiscal revenues while trying to minimise the risk of capture by powerful economic interests or granting them significant concessions. Additionally, these governments may be forced to confront concentrated economic sectors that do not naturally share their ideological orientation, and that may not trust that their efforts will be reciprocated, as it is often the case in a region where distributional matters have been historically contentious and where the fiscal contract between contributors and beneficiaries – establishing who is taxed, for how much, and what for – is insufficiently institutionalised and can be subjected to significant renegotiation ‘from above’ (Sachs Citation1989, Collier and Collier Citation2002, Bulmer-Thomas Citation2003, Haggard and Kaufman Citation2008).

In these conditions, and following the argument in the previous section, the pathways available to Latin American governments to resolve problems of fiscal legitimacy without exchanging benefits or access to the targeted sectors, are limited. In line with Evans’s argument, one alternative would be to adopt quasi-predatory strategies over those sectors, for example, through the expropriation of monopolistic industries, as it often happens in relation to oil production, mining, and steel, or through the political exclusion of the targeted sectors. Giraudo (Citation2021) moves close to this idea, arguing that the low political embeddedness of rural elites, and the centralisation of the Argentine federal system, is what allowed the central government to capture significant revenues from the soybean sector at the expense of rural actors and provinces (contrary to Brazil, where these actors could negotiate favourable concessions). The alternative to predatory or exclusionary approaches would be to develop forms of state embeddedness that grant sufficient social legitimacy for an asymmetric tax production policy. This latter possibility is explored in recent analyses. Mazzuca (Citation2013), for example, sees rentier populism and the ‘expropriation temptation’ to be regulated by the trade-off between the size of potential revenues, reputational costs in international capital markets, and the resistance of domestic political forces. Accordingly, governments in countries with a track record of foreign investment (i.e. Chile, Colombia, Peru) were less likely to assume rentier behaviours, than countries where ‘party deinstitutionalisation under the pressure of economic collapse (Argentina and Venezuela) or stagnation (Bolivia and Ecuador)’ enabled presidents to claim the plebiscitarian ratification of their fiscal agendas (Mazzuca Citation2013, p. 117). Wylde (Citation2018) arrives to a somewhat similar argument, claiming that certain Latin American developmental states sought to complement the absence of sufficiently embedded relations with elites by drawing on the legitimacy of a hegemonic project that bridged the interests of important segments of civil society, as has been historically the case with nationalism. This ‘embeddedness via hegemony’, as we call it, is what in principle granted governments in Argentina or Bolivia, for example, enough autonomy to break from neoliberal policies and attempt to ‘forge an alternative social contract that sought an inclusive, state-growth model’ (Ibid., p. 1119).

By exploring the case of agricultural export taxes in Argentina under the Kirchner administrations this article will argue that this second strategy not only was insufficient to counter the legitimacy deficits of a fiscal production policy that economically targeted but politically excluded rural sectors, but actually undermined its long-term legitimacy and survival, as it attached the policy to the electoral success of Kirchnerist candidates.

Argentina’s Fiscal Contract Under Crisis

As the pattern of industrialisation and integration of Argentina (and the region) into the global economy proceeded through the export of primary commodities, the appropriation of rural revenues has been a key factor structuring the fiscal relationship linking the rural sector (referred in Argentina simply as el campo or ‘the countryside’), the state, and other social and economic actors (Hora Citation2001, Bulmer-Thomas Citation2003, Chudnovsky and López Citation2007).Footnote6 This role has put the Argentine agrarian sector in a salient but uncomfortable position: accepted in the public imaginary as the principal competitive advantage of the country, and its natural engine for any vision of development and progress, but also marking it a recurrent objective for taxation and fiscal extraction schemes (Katz and Kosacoff Citation2000, Sánchez Román Citation2012). Hence, during much of the twentieth century Argentine governments sought to capture agrarian profits through the taxation of agricultural exports or the use of differential exchange rates, as part of projects of import-substitution-industrialisation (ISI) seeking precisely to break Argentina’s dependence on agricultural production and promote both industrial modernisation and economic autarky (Bruton Citation1998, De Paiva Abreu Citation2006). The rise of Peronism carried with it a marked industrialist and workerist vision of the state, which would lastingly redefine the social and political position of the countryside, as the Perón government (1946–55) not only consolidated an antagonistic political discourse in opposition to el campo and ‘oligarchic’ landowning elites, but moved to institutionalise its subordinated contribution to the developmental needs of the state and welfare needs of the urban working classes (Lewis Citation1975, Hora Citation2001, Citation2020, Romero Citation2002, Peralta Ramos Citation2019).Footnote7 This was done by monopolising foreign trade and redirecting agrarian wealth towards the urban economy, mainly through the IAPI (Instituto Argentino de Promoción del Intercambio), an institution that set prices to producers and arbitrated the real exchange rate (Sourrouille and Ramos Citation2013). Moreover, through policies such as the freezing of tenant leases and stronger rural labour laws, the Perón government contributed to expand the small land-tenant universe, weakening the countryside as a collective actor, and reducing the influence of large landowners. This subordinated role of the sector continued throughout the next few decades, as the rural economy shrank and the country losing two thirds of its participation in foreign markets by 1960 (Hora Citation2020, p. 287).Footnote8 Notwithstanding, governments of different orientation returned to export taxes to deal with the recurrent balance-of-payment crises, and associated distributive conflicts, Argentina experienced during its stop-and-go period, contributing between five and 20 per cent of total public expenses between the 1960s and 1990s – with the exception of the last dictatorship period (1976–83) and a brief period between 1987 and 1989 (Chudnovsky and López Citation2007, Castro and Díaz Frers Citation2008, Gerchunoff and Rapetti Citation2016).Footnote9

During the two Menem presidencies (1989–99), however, as part of a markedly neoliberal agenda abandoning ISI and state interventionism in the economy, exports taxes were lifted and the IAPI was dismantled, with its fiscal role compensated through FDI flows and foreign debt. Interestingly, this period already provides certain evidence of the discussed link between tax legitimacy and political inclusion. This is because for much of the decade, the Convertibility regime, which pegged the peso to the dollar, effectively functioned as a tax on exports, transferring income from exporting sectors to local industry and labour, for example, by lowering the costs of wage goods and imported supplies (Grinberg Citation2013, p. 456) – calculated by Rodríguez and Arceo (Citation2006, p. 14) to be equivalent to an average 35 per cent tax on agricultural exports through the decade. However, the rural sector remained largely in favour of the currency regime. Manzetti (Citation1992, p. 615) provides valuable clues why this may have been so, arguing sectoral acquiescence followed the ‘fiscal pact’ the Menem government negotiated with rural peak organisations, where the former committed to remove export taxes, promote agricultural exports to Brazil, and lobby against US and European subsidies, while the latter would push ‘their members to pay the new value-added tax, property and income taxes, and called for an increase in production’. Moreover, the government granted the sector influence in policy, setting joint commissions to discuss new taxes and credits, while upgrading Agriculture from Under-Secretariat to Secretariat. This already aligns well with the expectations derived from our fiscal legitimation model, as this fiscal arrangement shows an explicit vertical exchange component, trading fiscal compliance for influence, as well as a horizontal solidarity one, as while export taxes explicitly target specific sectors, fiscal appropriation through currency overvaluation is less discriminatory, affecting all exporters and economic actors.Footnote10

Before moving ahead it is also important to note that the combination of low international prices existing and currency overvaluation of the nineties impacted in the composition of the rural sector as it led to a race for productivity and economies of scale that benefited actors with the financial capacity to invest, favouring concentration on medium-to-large producers, the entry of large foreign players, and the expansion of the agricultural frontier to new territories (for example, through the use of genetically-modified soy) (Gras and Hernández Citation2009). This supported two related transformations relevant to understand developments in the following decade. First, the disarticulation of the sector as a coherent political actor continued, as traditional landowners and family businesses share the field with foreign agribusiness, farming pools, trust companies, and professionalised tenants (Gras and Hernández Citation2016, Hora Citation2020). Second, while this process of concentration involved the expulsion of labour, this did not involve the disappearance of rural communities and/or of the rural sectoral identity, but rather their transformation. Thus, during the nineties the rural space became more heterogenous in its composition, with the type of capitalist roles associated with agricultural production diversifying to include contractors, service providers, local machinery and chemical producers, transporters, consultants, etc., most of whom no longer lived ‘on’ the land but in nearby small towns and cities ‘strongly linked to their surrounding environment’ (Craviotti Citation2008, p. 9, Gras and Hernández Citation2016).

Both this neoliberal regime and fiscal pact came to an abrupt end in December 2001, when a mass social and political crisis culminated in the collapse of the centrist Alianza government (Levitsky and Murillo Citation2003, Malamud Citation2015). It was then under a declared state of emergency, excluded from global financial markets and with a real risk of democratic failure, that the transitional (Peronist) Duhalde administration (2002–03) turned again to emergency export taxes to balance state accounts, compensate collapsing tax income, and fund urgent social assistance, as poverty reached 57 per cent of the population (see ). These export taxes were applied to a range of products, such as raw materials, oil and gas, dairy products, regional commodities, and some manufactures. However, given that vegetable and food products represent around 40 per cent of Argentina’s exports (WITS Citation2020), the fiscal package targeted the main agricultural commodities; soy, sunflower, maize, and wheat, and some of its derivatives. As shown in below, export taxes on these products were hiked twice in 2002, with the emergency package representing 4.1 per cent of GDP and export taxes over ten per cent of the total fiscal revenue by the end of the year.

Table 1. Evolution of agricultural export taxes.

Crisis, Taxes, and Re-Financing the State

When these taxes exports were rolled out, the context of unprecedented social and political turmoil meant that the logic of emergency superseded any disagreements over fiscal redistribution, granting legitimacy to the government’s use of extraordinary taxes and contributing to its smooth implementation (interview Gómez Sabaini, Buenos Aires, 18/03/2019, interview Artana, FIEL, Buenos Aires, 27/03/2019). Organised around four peak associations, Sociedad Rural Argentina (SRA), Confederaciones Rurales Argentinas (CRA), Confederación Intercooperativa Agropecuaria (CONINAGRO) and Federación Agraria Argentina (FAA), countryside representatives raised some complaints, particularly as in January 2002 President Duhalde had promised not to raise taxes, but ultimately the scheme was accepted as being a necessary but temporal measure. Thus, the Treasury Secretary at the time, Oscar Lamberto, admitted that export taxes were a ‘bad tax’ but were needed to help with the fiscal deficit. At the same time, a FAA representative commented that even ‘if the sector can’t get the country out of the crisis alone’, sacrifices were needed (RN Citation2002a, Citation2002b), while in a recent interview, the then Economy Minister Jorge Remes Lenicov commented that prior to the implementation of the taxes, the SRA approached him to voluntarily offer five per cent of its revenues to the government (Perochena et al. Citation2020).

Upon assumption in March 2003, President Kirchner maintained this emergency discourse, underlining the need for the state to recover lost capacity and become ‘an active economic actor’ – promoting public investment, domestic consumption, and the growth of industry, employment and salaries – while rejecting neoliberal austerity and dependence on foreign debt (Kirchner Citation2003, Levitsky and Murillo Citation2008). Three months later, during a rare presentation at the SRA headquarters, the President and his ministers reaffirmed that export taxes were a necessary measure to finance social assistance programmes but ‘not a state policy that had arrived to stay’, recognising that it affected the profits of a sector coming out of a long period of high costs and low prices (Varise Citation2003).Footnote11 Again, with caveats, this emergency logic was accepted by rural actors: the SRA’s chairman, Luciano Miguens, indicated that export taxes were only justifiable if they addressed ‘exceptional Argentine problems’, such as hunger, although warned against viewing the sector as a lifeguard rather than as economic advantage to exploit (LA NACION Citation2003), while in 2004, the leader of the CRA highlighted that although they conceptually opposed export taxes, removing them was ‘impossible’ given the serious problems still faced by the country (Infobae Citation2004).

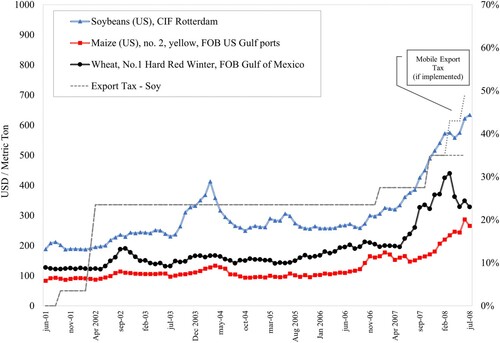

This emergency consensus would remain in place until 2006. According to Fairfield (Citation2015), this was a product of the lack of structural and ‘instrumental’ power by rural peak organisations, on two grounds. One, the institutional fragmentation and limited political influence of the sector, as will be commented ahead. Second, sectoral complacence given the dramatic increase in rural profits following the post-default devaluation of the peso, which went from one to three pesos/US$ between December 2001 and March 2002 (Rodríguez and Arceo Citation2006). Therefore, rural organisations continued questioning the taxes and even engaged in minor protest actions, with the CRA launching a four-day strike in July 2006 to protest against export restrictions on beef and export taxes on dairy products (Hora Citation2010), but overall a certain fiscal peace prevailed: the Kirchner government did not touch the tax rates set in 2002, whilst the exchange rate remained stable and international prices showed a moderate yet positive trend, as shown in below.Footnote12

Figure 1. Agricultural commodity prices (2001–08). Source: World Bank Commodity Price Data. Graph by the authors.

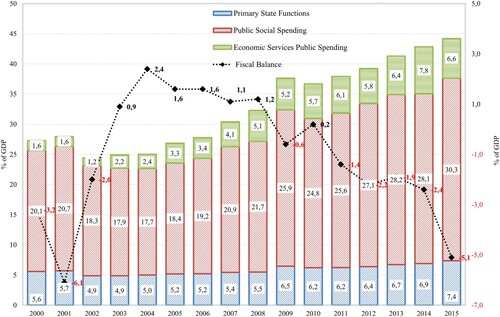

However, with commodity prices surging since late-2006, the government announced two tax rises in January and November 2007, increasing the rate for soy 12.5 per cent and for sunflower and wheat around eight per cent. However, the context in which these hikes took place had changed substantially vis-à-vis 2002. As shown in , by 2007 the country had grown at around eight-nine per cent for several years and surpassed its pre-crisis GDP, while poverty and unemployment levels halved – granting President Kirchner approval ratings above 50 per cent towards the end of his term and assuring the smooth electoral victory of his wife in October 2007 (Bergman and Gray Citation2007, Kosacoff Citation2007). Moreover, debt-restructuring had lowered the burden of interest payments – from 22 per cent of the fiscal intake in 2001 to nine per cent in 2007 – and the government had enjoyed several years of ‘twin surpluses’ in both its fiscal and current accounts, allowing the constant expansion of public spending (see ) – which grew 25 per cent in GDP terms since 2002, with major increases in subsidies to energy and transport, education and science, and social assistance programmes, among others (Filc Citation2008).Footnote13 Already prior to the hikes, emergency taxes provided 17.6 per cent of the total tax intake, and the recovery of the economy had reinforced the fiscal position of the government, resulting in a record-level tax burden of 25.1 per cent.

Figure 2. Government spending and fiscal balance (2000–15). Source: https://www.argentina.gob.ar/economia. Graph by the authors.

Table 2. Key economic and social indicators.

In this context, the government no longer emphasised the crisis to justify the increases but rather pointed to ‘problems of growth’ and the need to control the impact of inflation, which was 12.5 per cent in 2005 and by early-2007 had accelerated to a 20 per cent annualised rate – albeit the government-intervened INDEC reported 8.5 per cent (Gerchunoff and Kacef Citation2016).Footnote14 Top officials, like Chief of Staff Alberto Fernández and the economy minister Miguel Peirano, thus declared that the hikes did not pursue a fiscal goal but were rather needed to moderate the effect of rising international prices over the purchasing power of citizens, while also underlining the intent ‘to preserve adequate levels of profitability’ among rural producers (Cufré Citation2007, EFE Citation2007).

This argument was more readily opposed by rural and opposition actors, who qualified the export taxes as ‘confiscatory’ and aimed at compensating over-spending during an electoral year. Indeed, much of the rise in public spending, including cash transfer programmes, transport and energy subsides, housing projects, additional rises in salaries – with real wages estimated to have increased around 70 per cent since 2002 – benefited the government’ support base (Etchemendy and Collier Citation2007, Richardson Citation2009, Gómez Sabaini Citation2019). Elisa Carrió, presidential challenger and leading opposition figure, claimed the government was trying to finance its ‘fiscal disorder’, in light of the lack of foreign investment and external financing sources (P12 Citation2007, Perfil Citation2007a). The SRA stated that the government was following short-term interests rather than the long-term promotion of production and investment, indicating that some specific rural sectors were in crisis due to the export taxes (Perfil Citation2007b), while the CRA and FAA not only promoted minor protests but evaluated judicial measures due to the impact the hike would have on smaller producers, with lower productivity and margins (Bertoli interview, Buenos Aires, 26/03/2019, Cufré Citation2007).Footnote15 After 2004, these sectors were affected by the appreciation of the real exchange rate due to inflationary pressures, though the rise of international prices since late 2006 (see ) would somehow compensate the impact on profit margins (Fairfield Citation2011, p. 432, Damill et al. Citation2015, p. 5).

In this sense, both the government and rural sectors acknowledged the changing status of export taxes. As observed by Dborkin and Feldman (Citation2008, p. 234), and as shown in above, by 2007 the contribution of emergency taxes (4.7 per cent of GDP) was higher than the fiscal surplus. This meant that the fiscal contract between the state and rural sectors could no longer be assumed as temporary, with export taxes standing as a fundamental pillar in the long-term viability of the government’s economic model.Footnote16 Following Cantamutto et al. (Citation2016), in the neo-desarrollismo advanced the Kirchners these taxes were necessary for two purposes: an inward-facing fiscal one, allowing to subsidise public services and support industrial activity and disadvantaged sectors, and an outward-facing financial one, granting autonomy to the Argentine state by lowering dependence of foreign financial markets and providing hard-currency reserves to buffer external shocks. However, as claimed ahead, this switch from short to long-term arguments would reveal major deficits in the legitimacy and embeddedness of the fiscal agreement, which will manifest with the protests of 2008 and the political conflict that followed.

Political Exclusion, Tax Rebellions, and Partisan Polarisation

While the 2007 hikes did not crystallise sufficient resistance to create a coherent response from the rural sector that deterred the government, they served to consolidate the perception among sectoral representatives that the government sought to normalise an unfair fiscal scheme that excluded them and offered little benefits (Fairfield Citation2015). Indeed, while until 2006 there have been some limited instances, in 2007 the government manoeuvred to side-line the rural sector and minimise any interference from the opposition. Regarding the latter, the government continued the long-established practice in Argentina of using ‘Emergency and Urgency’ Decrees to waive and limit legislative control (with president Kirchner sanctioning 270 during his mandate) and relied on the Law of Economic Emergency sanctioned in 2002 to extend export taxes without consultation, and expedite policies in other sensitive areas such as budgetary changes, debt negotiations, and the regulation of tariffs (Cabot Citation2007, Cetrángolo and Gómez Sabaini Citation2010, Rose-Ackerman et al. Citation2011). Moreover, the government wielded fiscal centralisation to enforce party discipline among legislators and governors in agrarian provinces, seeking to deprive rural and opposition actors of influence and allies (Levitsky and Murillo Citation2008, Fairfield Citation2015) – this being another common grievance mentioned by rural sectors, highlighting that taxes did not return to provinces and municipalities from where they were collected but were redistributed to other areas by the federal government (Streb interview, UCEMA, Buenos Aires, 15/03/Citation2019).Footnote17

Regarding the former, the government exploited the fragmentation and institutionally weakness of the rural sector to marginalise it even further. Some peak associations, such as the SRA and FAA, had trouble working with each other, and had relations historically marked by mutual competition and suspicion, while contrary to other countries, the rural sector lacked a strong grounding among political parties, and suffered from lasting difficulties to establish coalitions with urban actors. Furthermore, with the arrival of Kirchnerism, the sector lost even more informal and personalised forms of access, enjoying from few connections with influential officials in the Ministry of Economy or the Secretary of Agriculture (Hora Citation2010, Freytes and O’Farrell Citation2017). Moreover, the government announced the second 2007 hike when CFK was president-elect, with a former government minister admitting that ‘Producers were furious at the timing of the rise and they felt powerless to complain as there was no official government in place. As the price of soy was increasing [to them] this amounted to a rent-seeking strategy’ (Anonymised interview A, Buenos Aires, 16/04/2019).Footnote18 In light of this, rural associations accepted that direct action would be of little value, and put some hopes on CFK’s campaign promise to improve relations (LA NACION Citation2007, Fairfield Citation2015).

This situation makes evident certain problems regarding the level of vertical and horizontal legitimation export taxes enjoyed. On the one hand, a highly centralised and exclusionary political process hampered the manufacturing of consensus regarding the policy production process, both at the sectoral and partisan level, while the strong redistributive use of export taxes away from agriculture affected perceptions of vertical fiscal reciprocity, as the sector saw limited returns in their higher contributions. At the same time, the redistributive use of export taxes created problems in terms of horizontal solidarity. Local industry, represented by the Unión Industrial Argentina (UIA), had remained a strong supporter of the Kirchners’ model, given that a high exchange rate, a protected economy, and subsidies on energy and fuel supported domestic consumption (Coviello Citation2014). This asymmetric treatment reactivated the ‘industry vs countryside’ divide that Peronism historically promoted, where a strong ‘national industry’ stood as the pinnacle of state autonomy and development, and rural elites represented export-oriented profiteering. This tension was captured by a rural federation leader who expressed at the time of the hikes that ‘the countryside is not servile, while industry lives under the shadow of the scheme put together by the government’ (quoted in Agrofy Citation2007). Furthermore, hopes for a more consensual embedding of the fiscal contract were rapidly abandoned, as already upon her assumption speech President CFK outlined the role the countryside had to play in national development, stating that while she ‘would like to live in a country where the main revenues are generated by industry’, to achieve this it was necessary to ‘agree on the deepening of this model [the government’s] that has allowed us to improve substantially the lives of Argentines’ (Fernández Citation2007).Footnote19 At the same time, the new CFK administration not only advanced policy projects that required increased public spending, such as pension reforms, the nationalisation of key firms, and the augmentation in scope and level of cash transfer programmes (Manzetti Citation2016, Wylde Citation2016), but had to deal with the negative effects inflation was having on tax collection and an worrisome drain of foreign-currency reserves due to energy imports – which, fuelled by growing consumption and subsidised prices, had multiplied by eight in dollar terms between 2003 and 2008 (SGE Citation2019).

It was in this context, and with international commodity prices still in upward trajectory, that in March 2008 the CFK government sought to hike export taxes by decreeing Resolución 125, a mobile scheme where for the next four years agricultural tax rates would vary according to the evolution of international prices. As shown in , this scheme would set an actual tax rate of around 44 per cent for soy if the international price were to exceed 600 US$/Ton (and of 41 per cent for sunflower, for example) and would effectively appropriate all the marginal increase in the producers’ perceived price (Castro and Díaz Frers Citation2008). When presenting this project, the new Minister of Economy Martín Lousteau made clear that the function of these retenciones móviles was to sustain a developmental path based on low energy prices and a high and competitive exchange, as well as achieve ‘a better equilibrium within agrarian activity, a greater decoupling of international and domestic prices […] while guaranteeing domestic supply at reasonable prices for Argentine families’ (Lousteau Citation2008) – an argument President CFK repeated in subsequent speeches to underline the monetary contribution rural exports made to foreign reserves and to sustain the value of the peso (Fernández Citation2008).Footnote20

This time the response from the sector was immediate. Luciano Miguens, President of SRA stated that evening ‘we thought reason would prevail’ and considered that government had abandoned any intent to promote a social agreement, while Mario Llambías, head of CRA, declared that that the measure was an excuse to sort out the government’s cash problems while warning that ‘things will get heavy’ (Colombres Citation2008). The following day the four rural federations established a common fighting body, known as Mesa de Enlace (‘Linkage Table’), which denounced the confiscatory character of the taxes and called for a general and open-ended agrarian strike. To the surprise of all, and revealing the extent of discontent across the extended rural sector, within a few days the conflict escalated to unprecedented proportions, as self-organised actors (known as ‘autoconvocados’) – comprised of the more heterogenous group of new rural tenants, professionals, and small and medium-sized investors that proliferated since the nineties (Gras and Hernández Citation2009) – mobilised and set up roadblocks and picket lines through the country. We do not intend to trace the evolution of these protests, which have been well covered in the literature, and would include a four-month long lock-out of Buenos Aires city, the spread of contention to the main cities, the mobilisation of the partisan opposition, and the defeat of Resolution 125 in the Senate by one vote by vice-President Julio Cobos on 18 July 2008 (Barsky and Dávila Citation2008, Rzezak Citation2008, Hora Citation2010).Footnote21 Rather, we treat these protests as a milestone revealing the failure of Kirchnerist administrations to sufficiently legitimise their preferred fiscal model.

The 2008 protest laid bare the risks and limits of the government’s strategy to embed this fiscal arrangement via a hegemonic coalition capable of enveloping the rural sector, marginalising its main actors and allies, and guaranteeing its subordinated fiscal role. When interviewed, many former officials still considered that the principal problem with Resolution 125 had been poor communication from the government, as neither rural sectors nor society understood the progressiveness of a mobile mechanism where excess revenues from high-price crops (i.e. soy) would be used to subsidise other sectors in case prices plunged (Anonymised interview B, Buenos Aires, 01/04/2019, Calvo and Murillo Citation2012). However, as indicated in Giraudo (Citation2017, p. 172), by then most rural actors lacked trust that the CFK government intended to keep its side of the fiscal bargain and considered they would end up ‘sharing the profits but not the loses’, and in light of their marginalisation over the last five years, agreed on that revolting was the only avenue left to defend their interests. Comments by rural leaders also revealed a low perception of horizontal fairness and denounced the ‘ideological’ character of taxes that targeted them but ignored other groups enjoying similar levels of profit – charging against bankers and industrialists present during the announcement of the mobile tax scheme who ‘clapped that the government was taking someone else’s money’ (Infocampo Citation2008). Tax exports also aggravated this problem as they did not consider the differential level of profit enjoyed by different type of rural producers and different participants in the agrarian productive structure, which comprised a significant proportion of the autoconvocados group, and the extent to which a sectoral identity had extended to urban constituencies that considered their welfare to be linked ‘with’ the countryside (Gras and Hernández Citation2009, Mangonnet and Murillo Citation2020). Moreover, as noted in Gras and Hernández (Citation2009, p. 17), rural organisations and self-mobilised rural collectives groups put major emphasis on territorial horizontal unfairness, considering the government’s fiscal regime privileged urban development over that of the inner lands and provinces.

The protests contributed to turn the relationship between the CFK government and the rural sector openly adversarial, marked from then onwards by high distrust and minimal communication.Footnote22 Moreover, the CFK government promoted the polarisation of the conflict along deep-rooted political cleavages in Argentine society, setting the ruling party, trade unions, and its popular support base, against an emerging but disarticulated bloc composed by the rural sector, the non-Peronist opposition, and urban middle and upper-classes historically opposed to the Peronist agenda – and that also viewed themselves as tax citizens unfairly targeted by the government (Catterberg and Palanza Citation2012, Adamovsky Citation2019).Footnote23 In a salient speech, the President defined pro-rural rallies as ‘protests of abundance’ (to differentiate from those of 2001) led by selfish and oligarchic sectors refusing to share ‘the burden of development’, while considering the rural leaders and their middle-class supporters as ‘golpistas’ and anti-democratic, a vocal minority opposed to wealth redistribution and equality (Página12 Citation2008). In this sense, the 2008 protests are amply recognised in the literature as a critical turning point in the political polarisation of Argentina, consolidating a pro- and anti-Kirchnerist divide that would go to permeate all aspects of political and civil life in a manner unprecedented since the fifties (De Luca and Malamud Citation2010, Pereyra Citation2017) – with one of our interviewees declaring: ‘[Resolution] 125 reignited the grand conflict between classes in Argentina’ (Scaletta interview, P12, Mendoza, 23/04/2019).

This polarisation made the possibility of legitimising export taxes through any form of fiscal contractualism or solidarism problematic, even though the export taxes remained in place (but were not increased). As explained in Freytes and O’Farrell (Citation2017, p. 191), after 2008 the strategy of the government sought to ‘actively disarticulate the political action of agrarian interests’ in both the sectoral and electoral arenas – as 12 ‘agro-deputies’ would be elected to Congress in 2009. Sectorally, the government moved to undermine the Mesa de Enlace and recreate segmented vertical exchange linkages with small local producers and cooperatives more akin to the government’s position, and used export permits to promote a more sympathetic export chamber COPECO, formed in 2009 (Ibid., p. 193).Footnote24 Electorally, the CFK administration strengthened the cohesiveness of its congressional bloc by increasing fiscal transfers to non-agricultural provinces, less averse to export taxes, while strengthening internal party discipline, expelling from her cabinet those representative as the more ‘dialogical’ wing, including the Minister of Economy, the Secretary of Agriculture, and her Chief of Staff, Alberto Fernández.Footnote25

However, while the government managed to contain large-scale nation-wide mobilisations by the sector, favoured by the recovery and rise of international prices (which in the case of soy peaked at 684 US$/Ton in August 2012), it could not control the spill out of contention to the partisan and electoral arena.Footnote26 The increase in political polarisation that followed the rural conflict meant that export taxes were no longer a mere distributive discussion about who and in which proportion should appropriate extraordinary incomes, but became part of a broader clash between antagonistic visions of the state: between a progressive national-popular front represented by Kirchnerism, advancing state autonomy and post-neoliberal development, and those that denounce it as a rentier, populist, and authoritarian project, seeking to extend the state’s control over the economy while concentrating the government’s control over the state (Mazzuca Citation2013, Pérez Trento Citation2021). An ex-government minister summarised this, indicating that ‘[…] for many the Kirchners are associated with retenciones, Kirchnerismo was born during the tax revolt’ (Anonymised interview C, Buenos Aires, 26/04/2019).

The principal consequence of this, perhaps unperceived at the time given the emphatic re-election of CFK in 2011 with 54 per cent of the votes, was that the survival of the tax scheme became dependent on the appeal and electoral continuity of the incumbent Kirchnerist coalition, while the Kirchnerist model became increasingly dependent on extraordinary agrarian revenues. This dual dependency relationship became increasingly strained during CFK’s second administration when public spending expanded dramatically (see ) but now in an adversarial post-crisis global context with falling commodity prices, particularly after 2012. As current and fiscal accounts went into deficit, foreign currency reserves fell (drained by the increasing weight of energy imports), growth stagnated, and social and economic indicators deteriorated, as shown in , export taxes started to play an explicit ‘financial’ role to support a model that a growing number of voices considered was failing, as the government struggled to simultaneously maintain wage increases and welfare schemes, and sustain the value of the currency (Cantamutto et al. Citation2016, p. 68). Since 2011, this led to additional distributive conflicts with trade unions and growing polarisation, particularly when the government imposed unpopular currency controls and import restrictions while blaming rural actors, transnational business, and middle-class sectors for wasting much needed dollars through capital flight, purchasing imported products, or even holidaying abroad (Tagina and Varetto Citation2013). Social discontent would eventually surge during a wave of massive anti-government protests between 2012 and 2013, which mobilised millions of citizens across the country and where economic interventionism, inflation, and political polarisation, among others, were key grievances, followed by the electoral defeat of Kirchnerism in the 2013 congressional elections, losing three million votes (Pereyra Citation2017, Gold and Peña Citation2019). This defeat, that would result in the unification of the anti-Kirchnerist opposition, opened the door to the success of Macri’s coalition in 2015, a success that recent analyses consider was enabled by the support received from the rural constituency, later rewarded with greater political access, the removal of export restrictions, and the lowering of export taxes (Lupu Citation2016, Freytes and O’Farrell Citation2017, Mangonnet et al. Citation2018).

Conclusion

By exploring legitimation struggles around agricultural export taxes in Argentina, the article calls for a new angle to discuss the viability and sustainability of developmental state projects that depend on the appropriation of extraordinary fiscal resources, claiming that the pursuit of state capacity and embeddedness has to be evaluated against both spending patterns as well as questions of collection. Moreover, the article indicates that the efficacy of the strategies available to reformist administrations to manage redistributive conflicts and legitimise new fiscal schemes is conditioned both by the structural characteristics of the sectors being targeted, and by patterns of state-society relations.

In particular, the article demonstrated that initial tax compliance with emergency export taxes in Argentina rested on a fragile consensus sustained by three contextual factors post-2001. First, the dramatic social, political, and economic crisis following the debt default, which (temporarily) aligned the interests of influential political and economic actors around the need to rebuild the state and improve social provisions. Second, the exceptional profit space resulting from the substantial devaluation of the peso in 2002 and the steady increase of international commodity prices, which made early tax hikes if not acceptable, tolerable to rural actors. And third, the political isolation of rural organisations in a context of a fragmented opposition and Peronist dominance. In this situation, it was argued, the Kirchnerist administrations placed their long-term bet on a strategy of embeddedness via hegemony, aiming to degrade the resistance of rural actors through a majoritarian front composed by those sectors more directly benefiting from their model of fiscal redistribution, local industry, and the popular classes. However, from 2007 onwards, these unstable pillars of legitimacy started to crack, generating increasing resistance among the targeted sectors, and revealing multiple legitimacy deficits at both vertical and horizontal levels. Interestingly, as proposed by Cantamutto et al. (Citation2016), after the 2008 protests the CFK government could have opted for a more radical ‘quasi-predatory’ strategy of nationalising foreign trade or parts of the agricultural supply chain, as was done under the Perón government, or pushing for major land ownership/use reforms. Instead, we argue that when considering the challenges of tax compliance from the collecting side, both these strategies were unlikely to succeed. Contrary to cases such as Venezuela, Bolivia and Ecuador, and even Chile and Brazil, where exceptional fiscal resources are extracted from enclave sectors with low embedding in civil society and/or where the state either already enjoyed direct participation or could monopolise core industries, Argentine governments are ‘forced’ to engage with an agrarian sector that even when institutionally weak, is highly privatised and diversified, geographically dispersed, and firmly rooted in local communities and the collective imaginary. Added to the resilience of certain cleavages in Argentine political culture regarding wealth redistribution, this made efforts to further disorganise, co-opt, or appropriate the agrarian sector very costly and risky. As was shown, the push for hegemony by Kirchnerist governments turned a sectoral revolt into a widespread pattern of political polarisation, leading us to think that a more predatory pathway would have likely generated even more resistance and additional extra-sectoral conflict, and required a level of political capital beyond the means of government – which despite its presidential dominance experienced legislative defeats both in 2009 and 2013. Instead, a more segmented and even consultative arrangement, as occurred in the nineties, aimed at facilitating vertical reciprocity between the state and some rural sub-sectors (such as smaller local producers and cooperatives) and the formation of horizontal cross-sectoral solidarity bonds, could have proven a more long-lasting solution, even if more laborious and compromising. The CFK government seems to have recognised this possibility after 2008, but still could not prevent the overflowing of this fiscal problem into the partisan and civil society spheres, neutralising any sectoral achievement while making the construction of political and social alliances considerably harder.

By approaching developmental governance and fiscal legitimacy arguments from a collection perspective, our argument draws out several interesting concerns and areas for future research, across different levels of analysis and fields of scholarship. At the local level, it would be relevant to trace the evolution of tax struggles in Argentina after 2015, particularly as in late 2019 a new Kirchnerist administration returned to power facing yet another context of crisis and with pressing fiscal needs, but now in an adversarial economic environment (even before the COVID-19 pandemic struck) and confronting a highly polarised society offering limited space for consensus. In this context, the relationship between the government and sectors with available surplus is turning even more problematic, with an apparent spike in attacks on rural producers’ silo-bags, aimed at forcing them to sell their grain (Cufré Citation2020), and the government implementing a one-off extraordinary tax on individuals with wealth above three million US$. On a more middle level, the article calls for greater attention to the political economy of tax compliance both in developmental and industrial policy analyses, and for a more nuanced consideration of the articulation of economic and industrial structures, fiscal visions, and models of state-society relations. In Latin America, we see the primary character of productive structures and their dependent ‘price-taker’ position in the global economy configuring a tense relationship between the state and certain economic actors, given the incentive the former has to ‘grow’ these sectors, and the level of dependence and influence that may follow. Investigating these relationships in other countries and regions, and with reference to other high-income sectors, such as technology companies or finance for example, would widen our understanding of alternative patterns of embeddedness and fiscal legitimacy.

Lastly, on a more global level, the dramatic collapse in economic activity brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic has put vertical and horizontal fiscal relations under unprecedented strain, with different economies and sectors being impacted in highly asymmetric manners. This presents an exceptional opportunity to study the process of legitimation and change of fiscal agreements comparatively and beyond the context of developing economies, and to examine the impact of different political, economic, and social variables – including models of economic governance, developmental priorities, and fiscal histories – in the renegotiation and compliance with new fiscal contracts.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank Jean Grugel and Ingrid H, Kvangraven for their helpful comments and advice on earlier versions of the article. They also would like to thank the two anonymous reviewers and the editor for their insightful feedback.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Matt Barlow

Matt Barlow is a Research Associate in the Interdisciplinary Global Development Centre (IGDC) and PhD candidate in the Department of Politics at the University of York. He researches on the political economy of taxation and the politcal economy of development in the Global South. Wider research interests include issues of emergency governance, regionalism, global health and the political economy of gender.

Alejandro Milcíades Peña

Alejandro M. Peña is Senior Lecturer in International Relations at the University of York and researches on issues of state-society relations and contentious politics, Latin American politics, and international relations.

Notes

1 Most export taxes were abolished in December 2015, while the tax of soy, the principal export product of Argentina, was reduced five per cent. Some were reintroduced in September 2018, in a new context of crisis and at a relatively low level, with President Macri declaring ‘we know this is a bad tax but it is an emergency’ (Agrofy Citation2018).

2 This idea relates with Mann (Citation1984)’s two meanings of state power, ‘over’ and ‘through civil society’, and his observation that capitalist democratic states are characterised by high infrastructural power and low despotic power.

3 Hence, we do not assume any legitimacy expectation from the nature or level of agrarian rents. For a discussion on the concept of ground rent both in the context of Argentina and other primary commodity-producing countries, see Ward and Aalbers (Citation2016), Grinberg and Starosta (Citation2014), and Iñigo Carrera (Citation2006).

4 For this reason, other authors used less benevolent terms to capture their accumulation models, with Mazzuca (Citation2013) talking of ‘rentier populism’ and Richardson (Citation2009) of ‘export-oriented populism’. A second strand of political economic analysis emphasises the ‘extractivist’ or ‘neo-extractivist’ logic of these political projects and their negative socio-environmental implications (Veltmeyer Citation2012, Svampa Citation2013, Burchardt and Dietz Citation2014).

5 While state capacity, understood as the institutional ability the state has to induce people and organisations to act in a desire manner, and state autonomy are usually discussed in tandem, our discussion revolves mostly around the latter, as we are not evaluating here any enhancement or decrease of institutional taxing capacities. See Cingolani et al. (Citation2015) for a detailed discussion.

6 Irrespective of using the terms ‘sector’ or ‘sectors’ we acknowledge the heterogeneity of the actors in the agricultural supply chain, with the main peak organisations representing different interests, often in conflict with each other. Thus, founded in 1866, the SRA represents large producers and landholders while the CRA is composed of regional federations, both being the more conservative market-friendly groups. The FAA and CONINAGRO instead, represent smaller local producers and service cooperatives and maintain more leftist and often pro-Peronist leanings. Interestingly, opposition to export taxes is one of the few areas where all organisations historically share a similar view. See Gras and Hernández (Citation2016).

7 The ISI model was championed by the UN’s Economic Commission for Latin America (CEPAL), led from by Argentine economist Raúl Prebisch, who was the first General Manager of Argentina’s Central Bank (Payne and Phillips Citation2010).

8 As noted in Romero (Citation2002, p. 103), legal restrictions and the scarcity of machinery (as imports were not given preferential treatment) exacerbated the decline of cultivated land and ultimately volumes available for export.

9 The relationship between these stop-and-go cycles and balance of payment crises has been explained partly due to foreign currency needs generated by an incomplete ISI process. See Fiszbein (Citation2015).

10 Pérez Trento (Citation2021) offers an alternative though not incompatible explanation, claiming that currency overvaluation generated less contention as its effects were less visible to economic actors, and so was the appropriating role of the state.

11 President Kirchner would set a trend to be continued during his administration and his wife, avoiding the annual opening ceremony of the SRA, until then commonly attended by the President and high officials.

12 In the case of soy, more rapid price increases furthered an ongoing ‘boom’, with producers expanding the planted surface and switching to this more profitable crop (Leguizamón Citation2014).

13 Energy and fuel-related spending grew 350 per cent in this period, while transport increased 200 per cent.

14 Tampering with the inflation measure had impact on GDP growth and poverty, allowing the government to show sustained improvements. See table 2.

15 As export taxes were determined by price and not by actual earnings, smaller producers and those located in less fertile regions faced higher tax per hectare (Rodríguez and Arceo Citation2006).

16 Bonvecchi and Giraudy (Citation2007) indicate that the public sector would actually been in deficit already in 2007 if it were not for the contributions of emergency taxes and transfers form the recently-reformed pension system.

17 While direct taxes belong to the provinces, export taxes and import fees fall under federal jurisdiction. Many provinces, particularly in the more impoverished north, are heavily reliant on federal fiscal transfers, a regime called ‘Coparticipación’, providing a mechanism for the government to discipline provincial actors (Cetrángolo et al. Citation1998, Bonvecchi and Lodola Citation2011).

18 President Fernández de Kirchner was elected on 28 October 2007 and was inaugurated as President on 10 December 2007.

19 It is relevant to note that CFK was defeated in Buenos Aires federal district, Córdoba and Rosario, the bigger cities, with the bulk of her vote coming from the working-class and highly dense Buenos Aires suburbs, and from impoverished provinces distant from urban centres (De Riz Citation2008).

20 The exchange rate remained stable around 3 pesos per dollar until mid-2008, when it started devaluing.

21 Julio Cobos was a member of the UCR party, and as such, a remnant of President Néstor Kirchner’s early commitment to ‘tranversalism’.

22 A soy trader interviewed by Giraudo (Citation2017, p. 173) notes his realisation, upon meeting public officials after the protests, that the officials considered agribusiness was administering wealth that did not belong to them.

23 The fiscal solidarity of urban middle classes can be accounted for, to a certain extent, on the basis of Dborkin and Feldman (Citation2008, p. 220)’s observation that despite a lower overall burden, tax rates in Argentina are often equivalent if not higher than in many developed economies, so that ‘[…] whoever pays all her taxes, faces a real tax burden much higher than the “average” resulting from the coefficient between collection and GDP’. It has to be said that not only centre and centre-right parties supported the countryside during the protests, but so did some Peronist (but not Kirchnerist) leaders, and many small radical left parties, which considered the government advanced over the interest of rural workers.

24 The Mesa de Enlace would break in March 2013, when the FAA did not join a lock out called by the other three organisations to protest against inflation, fiscal pressure, and the political use of export permits.

25 As mentioned, Alberto Fernández was elected president in 2019, with CFK as his vice-President.

26 This does not mean rural protests fully stopped, with the Mesa de Enlace and rural federations organising mobilisations and strikes from 2009 onwards, and numerous lock-outs launched by local producers, particularly in the littoral and North-eastern provinces (Krakowiak Citation2009, Mangonnet and Murillo Citation2020).

References

- Acemoglu, D., García-Jimeno, C., and Robinson, J.A., 2015. State capacity and economic development: a network approach. American economic review, 105 (8), 2364–2409.

- Adamovsky, E., 2019. La Historia de La Clase Media Argentina. Buenos Aires: Crítica.

- Agrofy, 2007. Siguen las críticas por las retenciones. Agrofy News, 12 Nov. Available from: https://news.agrofy.com.ar/noticia/72263/siguen-las-criticas-por-las-retenciones [Accessed 21 July 2020].

- Agrofy, 2018. Macri sobre retenciones: ‘Sabemos que es un impuesto malo pero es una emergencia’. Agrofy News, 3 Sep. Available from: https://news.agrofy.com.ar/noticia/177041/macri-retenciones-sabemos-que-es-impuesto-malo-pero-es-emergencia [Accessed 24 June 2020].

- Arditi, B., 2008. Arguments about the left turns in Latin America: a post-liberal politics? Latin American research review, 43 (3), 59–81.

- Artana, D. 2019. Interview.

- Balakrishnan, R., and Toscani, F., 2018. How the commodity boom helped tackle poverty and inequality in Latin America – IMF Blog. IMF Blog, 21 June. Available from: https://blogs.imf.org/2018/06/21/how-the-commodity-boom-helped-tackle-poverty-and-inequality-in-latin-america/ [Accessed 25 June 2020].

- Barsky, O., and Dávila, M. 2008. La Rebelión Del Campo. Historia Del Conflicto Agrario Argentino.

- Bergman, L., and Gray, K. 2007. Argentine first lady to run for president - Reuters.

- Bertoli, R. 2019. Interview.

- Bonvecchi, A., and Giraudy, A., 2007. Argentina: crecimiento económico y concentración del poder institucional. Revista de Ciencia Política (Santiago), 27, 29–42.

- Bonvecchi, A., and Lodola, G., 2011. The dual logic of intergovernmental transfers: presidents, governors, and the politics of coalition-building in Argentina. Publius: the journal of federalism, 41 (2), 179–206.