ABSTRACT

The regulatory state has provided a useful framework for conceptualizing the nature of the EU and its role in policy making. Although it is widely accepted that the conditions of European integration have dramatically changed since the 1990s, when this approach was formulated, few scholars have sought to theorize the EU ‘beyond’ the regulatory state. To fill this gap, this article puts forward the concept of the catalytic state, tracing its emergence within the field of climate and energy. The article proposes an initial theorization of the EU’s role as a catalytic state, situating it between the direct approach of the positive state and the indirect one of the regulatory state. On that basis, it provides a detailed mapping of catalytic state capacities in the climate and energy sector. Rather than replacing existing regulatory capacities, the paper argues, these new capacities have expanded the scope of EU action, following the logic of policy layering. To what extent this has indeed increased the ability of the EU to achieve its declared policy targets remains an open question, however. The paper concludes with a discussion of further research questions regarding the effectiveness, accountability and scope of the EU as a catalytic state.

1. Introduction

Since the seminal works of Giandomenico Majone (Citation1994, Citation1996, Citation1997) the regulatory state model has widely influenced studies on European integration and European Union (EU) policy making. The ‘standard view’ in EU scholarship still revolves around the idea that the EU is basically a ‘regulatory polity’ that mainly focuses on market regulation (Genschel and Jachtenfuchs Citation2014). Scholars of international political economy alike have recurred to this conceptualization to explain the EU stance in global affairs. According to this perspective – unlike traditional international actors such as the US or China – the EU stands as a ‘regulatory power’ that relies on its regulatory state identity (and capacity) for pursuing its goals in economic statecraft (e.g. Bradford Citation2016, Citation2020; see also Goldthau and Sitter Citation2015a, Citation2015b).

The internal and external conditions of European economic governance, however, have dramatically changed since the 1990s, when the regulatory state approach was formulated. Yet, only recently scholars have started to offer new perspectives on the EU. Genschel and Jachtenfuchs (Citation2014, Citation2016) have pointed out that European integration has moved towards ‘core state powers’, while Mertens and Thiemann (Citation2018, Citation2019) identify the emergence of a ‘hidden investment state’ in the EU. This contrasts with the indirect approach to economic governance assumed by the regulatory state perspective. Building on this incipient discussion, this article argues that the EU is indeed developing new, more interventionist instruments and governance arrangements. These aim at augmenting the EU’s state capacities in the face of new global and domestic challenges. These include the economic consequences of the global financial crisis coupled with the erosion of the Western dominated liberal order, the foundation of EU regulatory power. Instead, the EU is confronting the forceful return of geoeconomic and geopolitical competition (e.g. Buzan and Lawson Citation2014; Dannreuther Citation2015; Vakulchuk, Overland and Scholten Citation2020), while simultaneously seeking to accelerate the decarbonization of key economic sectors to fight a mounting climate crisis.

To further a better understanding of how EU governance is indeed changing in the face of these pressures, the article elaborates the concept of the catalytic state (Prontera Citation2019). The concept draws on recent comparative and international political economy literature on state activism in a globalized economic environment, bridging it with EU scholarship. Rather than debunking the literature on the EU as a regulatory state, the concept serves to augment this relatively narrow lens in tandem with the changing realities on the ground. In doing so, we do not attempt to provide a comprehensive account of the research agenda on the regulatory state (e.g. Levi-Faur Citation2013). Rather, we take its main elements as a starting point for our exploration of the evolving role of the EU as a state actor. We propose a set of ‘catalytic’ state capacities, which enhance the traditional core of the EU regulatory state without returning to the direct interventions of the traditional, positive state. Instead, a catalytic state is characterized by interventions aimed at leveraging the resources of non-state actors in pursuit of its policy goals.

To illustrate the development of these new capacities, we focus on the sector of climate and energy. Increasing energy security challenges related to Russia’s evolving geopolitical agenda combined with the mounting threat of climate change have exposed this policy area to particularly strong pressures. In this vein, the article only represents a first step in a broader assessment of the EU as a state actor within the global political economy. It focuses on how a catalytic state is beginning to take shape in this rapidly changing policy field, inducing changes that may not play out in the same way in other policy areas (for similar approaches see Majone Citation1996, Citation1997; Eberlein and Grande Citation2005; Bach et al. Citation2006).

In doing so, the article follows the original approach of Majone who focused his analysis on economic governance aimed at ‘large-scale modernization issues’ (Lodge Citation2008: 284). Then and now, the energy sector represents an important arena for this. In the 1990s, it was heavily influenced by market-oriented approaches aimed at the liberalization of the sector, and multiple scholars have analysed the sector from a regulatory state perspective (e.g. Eberlein and Grande Citation2005; Coen and Thatcher Citation2008; Jordan et al. Citation2011; Rayner and Jordan Citation2013; Goldthau and Sitter Citation2015a, Citation2015b). Since the late-2000s, the sector has become increasingly shaped by questions of energy security and climate change. Combined with broader changes outside the sector, these energy policy challenges have driven a layering process, in which more direct forms of public intervention were successively added to the EU’s regulatory agenda. In this article, we explore these changes using the catalytic state lens.

The remainder of the article is organized as follows. In Section 2 (‘From the regulatory state to a catalytic state’) the model of the catalytic state – as a distinctive mode of economic governance and policy making – is illustrated by contrasting it with the model of the positive and the regulatory state. Section 3 (‘The rise of the catalytic state in Europe’) illustrates the main drivers that explain the recent emergence of an EU catalytic state, highlighting the role of climate and energy policy in the shift towards more interventionist modes of EU governance. Section 4 (‘Theorising the EU catalytic state’) discusses the tools and resources at the disposal of the EU, conceptualizing within the catalytic state perspective. Building on these concepts, section 5 (‘Mapping the EU catalytic state in climate and energy governance’) maps empirically the emergence and consolidation of the EU catalytic state in climate and energy governance. Finally, Section 6 concludes with suggestions for expanding the research agenda on the EU as a catalytic state. This research agenda seems particularly timely as the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic crisis has opened a further window of opportunity for a more interventionist EU approach to economic governance.

2. From the regulatory state to a catalytic state

While the regulatory state represents an indirect approach to economic governance, the positive (or interventionist) state pursues government objectives by directly intervening in the economy. The catalytic state can be conceptually located in a middle ground between these two extremes. The notion of the catalytic state was introduced by Michael Lind at the beginning of the 1990s (Lind Citation1992). Despite the neoliberal turn, Lind (Citation1992) argued that states retained a key role in economic governance, albeit with evolving functions and strategies. According to Lind, a catalytic state is one that pursues its objectives less by relying on its own resources than by acting as a dominant element in multi-actor coalitions, while retaining its distinct identity and its own goals (Lind Citation1992: 3). It prefers to ‘move the world with a lever, not a club’ (ibid.). According to this perspective, governments try to augment their resources through complex, ad hoc consortiums composed of other states, multinational institutions, banks, corporations and other types of non-state actors. Central to this process is the idea that ‘the most important type of state institution of the catalytic state is a partnership of government with non-state entities’ (Lind Citation1992: 5; see also Cerny Citation1997, Citation2000). These partnerships help the governments of advanced economies to achieve their policy goals owing to the structural changes in the world economy triggered by globalization.

Similarly, Weiss (Citation1998, Citation2010) has challenged the narrow notion of a diminished neoliberal state. She recognizes the retreat of many traditional instruments for controlling economic activities in the post-Keynesian era, such as state-owned companies or financial institutions. However, she has also stressed that states have become more than simple promoters of efficient and competitive markets through their rule-making, rule monitoring and rule-enforcing activities, as suggested in the literature on regulatory state and regulatory capitalism (e.g. Majone Citation1996, Citation1997; Levi-Faur Citation2013, Citation2017). Rather, contemporary states have developed new strategies to pursue their goals actively. These include novel governance arrangements to promote cooperation between governmental agents and market actors, tools to leverage financial resources, and the establishment of national (or transnational) public-private partnerships and consortia for policy implementation (Weiss Citation1998, 2010). In more recent work on US industrial governance, Weiss (Citation2014) highlights the ‘catalytic role’ that governmental agents can play through the use of a diverse set of resources and non-regulatory instruments, including informational tools, funding and networking. In particular, she highlights the use of hybridized governance arrangements, like government-sponsored enterprises, government-sponsored venture capital funds, public interest corporations and consortia, to expand state capacity (see also Thurbon and Weiss Citation2021; Block Citation2008; Block and Keller Citation2011). Moreover, Weiss notes that ‘hybridisation’, though a general trend, assumes specific features, depending on the ideational and institutional context both at the national and sectoral levels (Weiss Citation2014). Moreover, it is distinct from privatization or outsourcing of state functions and so-called ‘regulatory hybrids’. The latter refers to new governance arrangements for carrying out regulatory activities, such as industry self-regulation or the use of private standards and third-party certification (Levi-Faur Citation2009). Similar to the notion of the ‘entrepreneurial state’, championed by Mazzucato (Citation2015), Weiss (Citation2006) calls for a nuanced appreciation of the varieties of resources, tools and arrangements that governmental agents can deploy to upgrade industrial production and foster modernization projects.

Within the varieties of capitalism literature, Schmidt (Citation2009) has championed the idea that states act as facilitators (or enablers) of market actors – rather than simply shaping the institutional and legal framework – to realize their policy goals (Schmidt Citation2009). Liberalization and privatization do not necessarily imply a linear shift from direct government action (faire) to forms of faire-faire, with private actors taking on the state’s former responsibilities and public authorities relegated to setting guidelines and incentives for market actions. Rather, states have begun to engage in faire-avec policies by collaborating with market actors to pursue their policy objectives (Schmidt Citation2009; Colli, Mariotti and Piscitello Citation2014).

The various perspectives contrast with the prevailing focus on regulations as key institutions, resources and preferred tools of government in the regulatory state tradition (Majone Citation1996, Citation1997; Hood et al. Citation1999; Levi-Faur Citation2013) and related perspectives, such as the Vogel’s marketcraft conception (Vogel Citation2018). While the latter acknowledges the important role of government even in so-called liberal market economies, it remains focused on the creation and enforcement of laws and regulations as vehicles of state intervention (Vogel 2108: 9). However, these new forms of governance also differ from the interventionist measures of the positive state. The differences in particular concern: (a) the guiding principles, or policy frames, that orient governmental agents’ understanding of policy problems and suggest remedies to address them; (b) their role in fostering large modernization projects; (c) the key governance structures for managing economic activities at the sectoral level and (d) the main policy tools deployed by governmental agents. Based on these basic categories, provides a characterization of the positive state, the regulatory state and the emergent catalytic state.

Table 1. Forms of state and modes of economic governance and policy making.

The different ‘forms of state’ and their corresponding characteristics, as summarized in , do not represent mutually exclusive or absolute categories. Rather, they represent ideal-typical characterizations of emergent processes of transformation (Clift Citation2014: 172) and corresponding modes of governance and policy making that illustrate specific patterns of interactions between governmental agents and market actors (Scott Citation2005). In this article, they serve as means for distinguishing the relative importance of different types of state intervention during different time periods in the selected policy field.Footnote1 In the words of Caporaso, we consider them as ‘something to be accented rather than something to sort into categories’ (Caporaso Citation1996: 31). These modes of governance and policy making can be depicted at the national level as well as at the EU supranational level. In this we follow a consolidated tradition that has applied the forms of state concept to the EU as an international structure of governance – or as ‘an international state’ (Caporaso Citation1996: 33) – in order to allow comparative and historical analysis and underscore the role, resources and strategies of EU governmental agents in policy making (e.g. Begg Citation1996; Caporaso Citation1996; Majone Citation1996; McGowan and Wallace Citation1996).

3. The rise of the catalytic state in Europe

Majone (Citation1997) explained the rise of the regulatory state in Europe as a result of the concomitant strategy of liberalization, privatization and market-building policies enacted since the end of the 1980s. Majone, in particular, argued that the process of European integration, especially since the launch of the 1987 Single European Act, was largely supported by the new market-oriented strategy, and hence the EU was emerging as a regulatory state (Majone Citation1996, Citation1997). Because of its budget constraints and its lack of an independent power to tax and spend, the EU had no alternative but to develop as ‘an almost pure type of regulatory state’ (Majone Citation1999: 2).

Lodge (Citation2008: 283-85) illustrated three crucial mechanisms that drove the rise of the regulatory state in Europe: disappointment, strategic choice given structural constraints, and habitat changes. These mechanisms, combined with the role of the European Commission as an entrepreneurial actor, remain useful for understanding changes in European governance and ongoing shifts in the development of the EU as an international state. The rise of the catalytic state at the EU level mirrors a shift in the EU strategy away from the previous more ‘liberal’ position and was initiated (approximately) in the late 2000s.

This shift in strategy was driven, first of all, by disappointment, both within the Commission and the member states. The Commission led by Barroso clearly recognized that ‘business as usual’ in the area of economic governance would consign Europe to ‘a gradual decline, to the second rank of the new global order’.Footnote2 A perception of failure and the inability of the existing regulatory approach to cope with the problems triggered by the 2007–08 economic crisis in a changing global environment increased endogenous pressures for change. The beginning of the new century opened with the 2000 Lisbon Strategy, which was still characterized by a faire-faire approach (as it was its 2005 revision). However, in November 2008, with the proposal for the European Economic Recovery Plan (EERP), the Commission embraced a more interventionist stance that deviated from the previous focus on regulatory measures. As stated by Commission President Barroso ‘exceptional times call for exceptional measures’. The EERP aimed at boosting investments, in particular in the fields of energy infrastructure and low-carbon technologies. Also, the EEPR foresaw a growing involvement of the EU public banks (the EIB and the EBRD) in modernization projects in member states, a refocus of the EU structural funds on climate and energy projects, and innovative proposals for partnerships between the public and private sectors.

The Commission had already launched similar ideas at the European Council’s Essen summit in 1994. However, a coalition of centre-right member states blocked more ambitious proposals coming from the Commission (and centre-left national governments) (Hix and Lord Citation1997: 192-94). Although the guidelines for the so-called Trans-European-Energy Networks (TEN-E) were laid down in 1996, the EU financial support for these projects remained marginal until the late 2000s (see further details below). Then the financial crisis opened a window of opportunity for change, which led to adoption of the investment-oriented agenda of the EERP. To be sure, the traditional regulatory measures and market-based instruments would not be replaced by these new tools. Rather, the more interventionist stance foreseen by the EERP was considered part of a ‘smart’ policy mix, which combined conventional regulatory measures with more activist tools (European Commission Citation2008).

This nucleus of the EU catalytic state would be incrementally expanded and strengthened in the following years. In response to the slow recovery after the crisis, the Juncker Commission established the Investment Plan for Europe and the European Fund for Strategic Investments (EFSI) in 2014/2015. These new vehicles significantly increased the ambition of the EU’s investment agenda, while expanding the use of new forms of financial support. While the EERP focused on €5 billion in direct spending on additional infrastructure and an additional €15 billion in EIB funding, the so-called Juncker Plan aimed to leverage €315 billion in investment, mainly through the strongly expanded use of guarantees and blending. Later, in 2018, the Juncker Commission launched the InvestEU programme to further expand the Investment Plan, bringing the investment target to €500 billion, and to create a single governance framework for the EFSI and several other (13) financial instruments.

These initiatives retained their strong focus on energy and climate action, an area of increasing pressure. In the field of energy security, especially Eastern European member states were disappointed with the results of previous market-based approaches. Following the Crimea crisis, Donald Tusk – Polish Prime Minister at the time – proposed the idea of an Energy Union. The European Commission seized the momentum of this initiative to formulate a more comprehensive energy and climate agenda for the EU. Building on the recent success of the Paris Climate Agreement, it merged the Energy Union’s energy security focus with a low-carbon industrial policy agenda. Secondly, it brought together the goal of further deepening European energy market integration with a more activist, investment-oriented approach to common infrastructure development (Szulecki et al. Citation2016).

Despite these advances, the means at the disposal of the EU to promote investment are very different from that of an interventionist state of the old Keynesian type. Indeed, the EU budget has been further reduced in recent decades: from roughly 1.2% of EU gross national income in the 1990s to roughly 1% in 2020.Footnote3 Hence, the EU’s uses of various financial instruments and arrangements – often involving EU public banks like the EIB – represent strategic choices given these structural constraints to achieve a greater impact than the size of its limited budget and scope of its competences would normally allow (Mertens and Thiemann Citation2018, Citation2019). The expanded EU-level investment agenda also reflects limitations at the member state level. The financial crisis had left key countries, like Spain or Italy, with severely constrained public budgets and poor sovereign credit ratings. This has limited their ability to support domestic investment, increasing pressure to accept an expansion of EU-level instruments.

Finally, these changes have been enabled by ideological and material challenges to the Western-dominated neoliberal order. These habitat changes were initiated in the early 2000s and intensified with the 2008 financial crisis. At the ideational level, public involvement in economic governance has regained legitimacy. As mentioned, the Commission’s more interventionist proposals that were halted in the mid-1990s were embraced after the crisis. These changes were favoured by concomitant international developments. Since the turn of the century, multilateral regimes have been increasingly challenged by regionalization, a resurgence of bilateral trade deals, protectionist measures and new competitive dynamics between blocs and countries (e.g. Buzan and Lawson Citation2014).

Again, habitat changes are particularly evident in the field of climate and energy. The ideational and material shift from the neoliberal energy order of the 1980s to the more interventionist and confrontational state-capitalist order of the early 2000s has been widely discussed (e.g. Dannreuther Citation2015; Van de Graaf et al. Citation2016). The Russia-Ukraine gas crisis and the Russian annexation of Crimea further aggravated the perception of a more hostile geopolitical environment for EU energy security, leading to Tusk’s Energy Union initiative.

Energy security coupled with climate change concerns have also driven interventions in energy markets to promote renewables at the member state level. Moreover, low-carbon energy technologies are increasingly perceived as strategic assets in the forthcoming geo-economic and geopolitical competition for economic development and security (Vakulchuk, Overland and Scholten Citation2020). At the same time, interventions in support of domestic industry at the member state level are not only limited by market size but also by the rules governing the single market. With the launch of the European Green Deal by the von der Leyen Commission, the idea that the EU should take a more interventionist stance to upgrade its transformative capacity while promoting European industry in green and climate-related sectors has been proposed as the new ‘core identity’ of the bloc.

To this end, the European Green Deal combines more traditional market-based and regulatory instruments, like the Emission Trading System (ETS), with a strong emphasis on investment support and public-private cooperation for the promotion of new infrastructures and technologies (e.g. with the Green Deal Investment Plan, GDIP). This approach was confirmed in early 2020 with the new EU industrial strategy (‘A New Industrial Strategy for Europe’), which places a special focus on low-carbon technologies. Moreover, it reiterates the importance of new EU financial instruments, leveraging, public-private partnerships and industrial alliances in order to reinforce ‘Europe’s industrial and strategic autonomy’ in the wake of an increasing geoeconomic competition and challenges to the rules-based international system (European Commission Citation2020: 13).

The GDIP has also further raised the scale of the EU-level investment agenda. Initially, it aimed to unlock €1 trillion in sustainable investments over the following decade. To achieve this, the Commission proposed to combine €503 billion in EU funding over that period with guarantees to enable the EIB and other partners to channel funds into climate-friendly investments. In the wake of the Covid-19 crisis, these trends have been further enhanced. Building on the GDIP, the Commission quickly created the further expanded NextGenerationEU stimulus package with the Recovery and Resilience Facility as its centrepiece. The facility will provide €672,5 billion in support of investments in member states, of which 37 percent is earmarked for climate-related investments. Crucially, the bloc also agreed to finance these investments with large-scale EU-level borrowing to be repaid with corresponding revenue raising capabilities. To be developed by the European Commission over the coming decade, this signals a further step towards the expansion of EU-level investment capacities.

4. Theorizing the EU catalytic state

Conceptually, the regulatory state perspective mainly emphasises so-called authority-based instruments in EU policy making, most importantly the Commission’s authority over the EU’s single marketFootnote4 (e.g. Versluis, Van Keulen and Stephenson Citation2010). The catalytic state perspective highlights those tools of government that, according to a classification developed by Hood, rely on nodality- and treasury-based resources (Hood Citation1983). With regards to treasury, it is important to consider not only the EU’s (limited) budget and direct spending but also the financial techniques and arrangements used to leverage wider financial support from public and private actors and involving European public banks, like the EIB. As suggested, these efforts differ from the modes of financial backing granted under the interventionist–Keynesian state model (e.g. Mertens and Thiemann Citation2019). With regard to nodality, it is important to consider its procedural elements, which are related to the government’s ability to form networks (e.g. Eliadis, Hill and Howlett Citation2005). Nodal actors shape the institutional context in which policy processes take place. Moreover, they have a ‘strategic advantage’ in negotiating with other actors due to their central position and their information and knowledge resources (e.g. McNutt and Rayner Citation2010). That is to say, EU governmental agents can exploit their nodal position to promote the structuration of networks of actors, and they can use their information and knowledge resources to promote their objectives within these networks.

Overall, in terms of Hood’s NATO formula (Nodality, Authority, Treasure and Organization), the main focus of the positive state was on organizational-based resources, as the direct provision of goods and services and public enterprises were key elements of its mode of governance and policy making. The regulatory state tradition (EUreg) focuses on authority (A) as the EU’s central resource, while the catalytic state perspective (EUcat) emphasises the role of nodality (N) and treasury (T) in the EU policy mix (see ).

Figure 1. Regulatory vs. Catalytic state: a different emphasis on EU policy instruments. Source: Prontera Citation2019.

Taken together, nodality and treasury involve the ability of EU governmental agents to connect actors, preside over networks and mobilize scattered (organizational and financial) resources to achieve their objectives. Nodality and treasury-based tools are designed to facilitate policy implementation and foster coalition building and public–private partnerships. By combining these tools, the EU governmental agents can play a ‘catalytic role’, upgrade industrial production and trigger transformative modernization projects.

This emphasis on nodality and treasury-based tools has been accompanied by the structuration of novel governance arrangements. A key feature of these arrangements is the hybridized institutional form they frequently take. These forms are essential to augment the resources of a catalytic state and achieve its goals. As suggested by Lind (Citation1992: 5), the ‘partnership of government with non-state entities’ is the ‘most important’ type of institution for the catalytic state. However, unlike traditional nation states the EU cannot develop ‘EU-owned enterprises’ nor mixed ones. Instead, the EU has deployed a variety of governance arrangements (e.g. multi-stakeholder platforms, steering groups, alliances) and public-private partnerships involving EU agencies, member states and private actors, frequently combining these with a mix of financial instruments. Moreover, financing itself is increasingly taking on hybrid forms. Non-traditional financial instruments, offered directly by the EIB or by the Commission, like blending, guarantees, subordinated debt or equity are deployed to leverage private sector investment and close the identified investment gap in infrastructure and industrial development.

5. Mapping the EU catalytic state in climate and energy governance

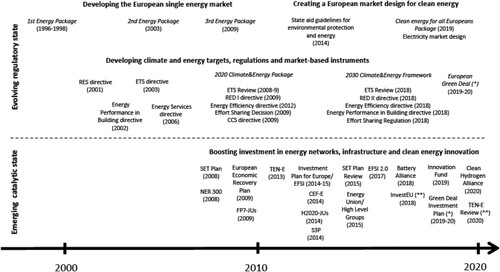

Until the late 2000s, the EU climate and energy governance was guided by the regulatory state approach with a strong focus on establishing liberalized and integrated energy markets in Europe (e.g. Eberlein and Grande Citation2005; Coen and Thatcher Citation2008; Buchan 2011). This was especially manifested in the three legislative packages (1996, 2003, 2009) for the development of the single energy market. This was complemented by a set of regulatory and market-based measures enacted in support of renewables, energy efficiency and the reduction of GHG emissions (Jordan et al. Citation2011; Rayner and Jordan Citation2013). At the heart of this was the introduction of the European Emission Trading Scheme (ETS). This approach has continued in 2010s, though with an added focus on creating a market design for clean energy. In parallel, the nucleus of the EU catalytic state began emerging in the late 2000s. As illustrated, this resulted from the Commission’s efforts to boost investment in networks and infrastructure and clean energy innovation. An additional layer of programmes and plans – as operational schemes for the new policy goals (Capano Citation2019: 596) – was added to the evolving core of the EU regulatory state (see for an overview of key initiatives since the mid-1990s).

Figure 2. From regulating European energy markets to catalysing climate and energy investment. Source: authors’ elaboration. Notes: (*) = as of December 2020 several proposals of the European Green Deal (e.g. ETS revision, EU Climate Law) are still under discussion; (**) = the InvestEU programme will be operative by 2021 (^) = the Green Deal Investment Plan will be supported by the InvestEU programme; (^^) = the 2020 Commission proposal for the revision of the 2013 TEN-E guidelines prioritizes electricity grids, offshore energy and hydrogen infrastructure (while natural gas infrastructure will no longer be eligible for EU support).

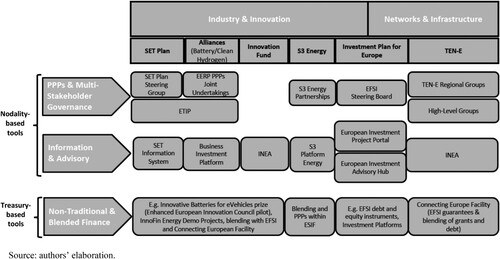

Drawing on the concepts introduced above, this section provides a map of the key elements of the EU catalytic state distinguishing between the spheres of energy infrastructure and networks, on the one hand, and low-carbon innovation and industrial development, on the other. For each area, we highlight the emergent nodality and treasury-based tools, and the related governance structures, which characterize this new layer of EU governance and policy making (for an overview see ). This part of the article does not consider the most recent developments related to the post-COVID recovery, but rather focuses on elements that were in place already before this latest turning point in the evolution of EU governance capacities.

Figure 3. Mapping the EU catalytic state in the climate and energy sector. Source: authors’ elaboration.

5.1. Energy networks and infrastructure

With regard to energy networks and infrastructure, the European Energy Programme for Recovery marked a departure from the previous regulatory approach focused on promoting competitive and liberalized markets (Prontera Citation2019). The programme granted targeted financial assistance to natural gas and electricity networks that contributed to improving connectivity and energy security. While the Commission had already fully recognized the limits of the previous market-oriented and regulatory approach in the 2000s, this innovation marked an important step towards realizing a more active role as a ‘facilitator’ and coalition-builder for energy projects (European Commission Citation2010a, Citation2010b). Building on the already existing TEN-E program, the financing mechanism of the European Energy Programme for Recovery evolved into a much more prominent feature of the EU policy mix. Before 2009, the EU’s financial contribution for the TEN-E projects was mainly intended for feasibility studies and rarely amounted to more than 0.01–1% of the total costs (European Commission Citation2010a). Now, however, under the European Energy Programme for Recovery, EU funds could support not only feasibility studies but also construction works, with contributions of up to 50 per cent of total costs. This trend was institutionalized and further diversified in 2013–14 with the launch of the new TEN-E scheme (Regulation 347/2013) and the Connecting Europe Facility for Energy (CEF-E). CEF-E was intended to leverage the EU treasury-based resources by offering support to projects through innovative financial instruments such as guarantees and project bonds.

These treasury-based instruments are complemented by the facilitating role the Commission plays within the planning system created for the so-called Projects of Common Interest (PCIs), established with the 2013 TEN-E scheme. This system is organized around the regional (gas and electricity) groups mandated by Regulation 347/2013. Drawing on the Commission’s nodality-based resources, the Commission convenes these multi-stakeholder governance platforms to bring together member states and company representatives. Under the Energy Union Strategy this system has further evolved with the launch of a set of regional High-Level Groups in 2015. These High-Level Groups are ad-hoc governance arrangements – outside EU regulations – coordinated by the Commission and with the participation of the member states and the private sector. Via these platforms, the Commission creates and structures networks and promotes cooperation among public and private actors to facilitate the realization of high-priority investment projects in each region of the EU energy market. Moreover, the management of CEF-E was put in the hands of the Innovation and Networks Executive Agency (INEA). Established in 2014, it was tasked with the implementation of the CEF-E projects, providing expertise, information and advice to projects promoters.

5.2. Low-carbon innovation and industrial development

Similarly, the Commission has deployed its nodality and treasury-based tools to promote and shape low-carbon innovation and industrial development. A first step in this direction was the launch of the Strategic Energy Technology Plan (SET-Plan) and the NER 300 programme to support low-carbon innovations with dedicated financial assistance and multi-stakeholder platforms. A key aim of the SET-Plan – improved in 2015 within the context of the Energy Union Strategy – was the coordination of actors in a set of technology-specific innovation systems. To do so, the Commission established the SET-Plan Steering group, composed of the Commission and representatives from the member states, as well as the European Technology and Innovation Platform (ETIP) for stakeholders from industry and the research community. This has been further complemented by a system for information sharing among stakeholders (SET Information System). In the same period the Commission established public-private partnerships for low-carbon innovations, both under the EERP (e.g. ‘Energy-efficient Buildings’, ‘European Green Cars Initiative’) and under the Seventh Framework Programme (FP7). Under FP7, public-private partnerships between the Commission and industry, the so-called Joint Undertakings (JUs), were launched in five strategic low-carbon technology fields. Under Horizon 2020, the JUs were further developed and expanded, adding three new JUs.

Finally, under the EU regional policy, the Commission launched the so-called Smart Specialization Platforms. These platforms support regional authorities in the design and implementation of so-called placed-based innovation strategies in close cooperation with local stakeholders. More than two-thirds of such strategies have chosen energy-related topics and are supported by S3P Energy, the thematic platform on energy. This helps build capacity, facilitates the uptake of European Structural and Investment Funds (ESIF) and promotes inter-regional partnerships. Overall, climate-change-related actions represented about the 25% of total ESIF budget between 2014 and 2020, almost double the amount of the previous period and slightly over the 20 percent committed by the Commission (DG-IPO Citation2017). Moreover, the Common Provisions Regulation, which sets the rules for the disbursement of ESIF resources, was amended in 2013 with the aim to increase the use of blending within PPP arrangements for implementation of projects within this context (EPEC Citation2016).

This aligns with the increasing role of non-traditional financing instruments in EU-level climate and energy financing more generally. Since its launch, the EFSI was also intended to support investment projects to help achieve the 2030 EU climate objectives. The revision of the EFSI (EFSI 2.0) stated that at least 40% of EFSI financing under the infrastructure and innovation window (provided by debt and equity instruments) should target climate projects in line with the COP21 commitments. The EFSI also provided for the establishment of the so-called ‘investment platforms’: public-private co-investment arrangements structured with a view to catalysing investments in a portfolio of projects combining EFSI, ESIF and other public and private funding.Footnote5 In 2019, the EU established the Innovation Fund (an upgraded version of the NER300 programme) to promote innovative, low-carbon technologies (e.g. carbon capture and storage, CCS) and renewable energy generation. This new fund is financed with emission allowances from the ETS. It is implemented by the INEA and it can contribute to blended operations under EFSI and CEF-E. It is considered a key ‘instrument for delivering the EU’s economy-wide commitments under the Paris Agreement’ and supporting ‘the European Commission’s strategic vision of a climate neutral Europe by 2050’.Footnote6

Moreover, the Commission and EIB have developed a series of targeted financing schemes to catalyse investment in low-carbon energy technologies, including the InnovFin Energy Demo Projects, the Enhanced European Innovation Council Pilot, and Private Finance for Energy Efficiency. Recently established financial instruments are supported by additional tools aimed at facilitating investments through the provision of information and advisory services, such as the European Investment Project Portal and the European Investment Advisory Hub. Both operate within the framework of the Investment Plan for Europe as partnerships between the Commission and EIB. Scholars of climate finance have highlighted that ‘nonfinancial and informational modalities are just as important as financial mechanisms’ (Bowman Citation2017: 8) for mobilizing private capital and enhancing the implementation of climate-friendly projects. These nodality-based tools – also known as ‘facilitative modalities’ – complement the hard financial mechanisms. They are not merely intended to solve market failures, such as asymmetries or the lack of information; rather, they help governmental agents guide private actors and create networks and coalitions around common projects and priorities.

New modes of combining nodality and treasury-based tools also target novel sectoral initiatives, such as the European Battery Alliance. This initiative, launched in 2017 and linked to ETIP and the SET-Plan, combines the Business Investment Platform – an advisory body gathering the Commission, interested member states, the EIB and companies – with targeted financial assistance (e.g. the Battery for eVehicles prize under Enhanced European Innovation Council pilot). It aims at fostering industrial consortia and public-private partnerships. It illustrates how specific forms of hybridizations have emerged in order to expand the capacities of the EU in response to perceived challenges. As highlighted by the Commission, batteries represent ‘as a strategic value chain’, where the EU ‘must step up’ to ‘prevent a technological dependence’ on its ‘competitors’ (European Commission Citation2019: 1-2). In 2020, the Commission has proposed to extend this approach launching a European Clean Hydrogen Alliance – as an upgrading of the JU on hydrogen – and further initiatives for low-carbon industries (European Commission Citation2020).

6. Conclusions

The resilience of the regulatory state model in EU studies has been impressive. Scholarly debate has only recently begun to reconsider to what extent it still reflects the nature of EU governance. Clearly, regulatory instruments continue to represent a crucial asset for the EU institutions. However, in this article we contend that the EU has developed tools and resources well beyond those expected by the regulatory state perspective. We show that conditions that initially gave rise to the regulatory state – such as disappointment with existing policy approaches and a shifting ideational and material landscape – are now shaping the emergence of new governance approaches. Mediated by remaining structural constraints of EU policy making, these new approaches form the nucleus of what we refer to as a catalytic state.

These new capacities are not replacing the pre-existing regulatory model of governance, but rather expanding the EU’s portfolio of policy instruments in the sphere of climate and energy. The Commission has seized on an evolving ideological and (geo)economic context to gradually add new instruments and competences to its portfolio, while retaining the core tenets of the single market. Following the logic of policy layering (Streeck and Thelen Citation2005; Capano Citation2019), new instruments, such as the TEN-E program, started as policy innovations with a very limited financial scope. They were then scaled-up and further developed in times of extreme pressure in the wake of the financial crisis. Over time, these new instruments have grown into established elements of EU governance. A growing emphasis on nodality and treasury-based tools has been evident since the early 2010s. A faire-avec approach has emerged and consolidated with the EU governmental agents that have changed their role from ‘regulators’ to ‘facilitators’. New governance arrangements, financial instruments and hybrid forms for promoting coalition-building, public-private partnerships and investment projects have been established. Their overall result has been a more interventionist stance of the EU. Nevertheless, they are clearly distinct from the forms of intervention captured in the positive state model.

It might also be noted that EU-level regulations governing the single market represent an important barrier to the implementation of more interventionist measures at the national level. By constraining member states, this has added pressure to expand competences at the EU-level. So, rather than challenging the regulatory state, the catalytic state is indeed partly its product. Moreover, developments following the COVID-19 crisis seem to indicate that continued expansion of the EU’s investment-oriented competences may ultimately lead to the further development of more traditional state capacities, i.e. the EU’s revenue-raising capabilities. That said, it is far from clear whether this trend will continue over the medium- and long-term.

These findings raise a number of important questions for future research. First, how effective are these new forms of interventions? And how effective is the interplay between the regulatory and catalytic state in furthering the goals of the EU? As suggested, in the energy sector the EU catalytic state has been instrumental in promoting infrastructure and energy security. In this area, the new forms of intervention have positively complemented the regulatory measures of the single energy market increasing the overall effectiveness of the EU action (Prontera Citation2019; Prontera and Plenta Citation2020). Similarly, in their study of multi-level climate governance in the EU, Jänicke and Quitzow (Citation2017 ) highlight the importance of EU-level interventions in supporting actors at various levels of governance and enabling dynamic processes of ‘multi-level reinforcement’. Other scholars have been more critical. In their study on the SET-Plan implementation, Eikeland and Skjærseth (2020) argue that the low level of coordination with the EU’s regulatory agenda in the area of climate and energy has negatively affected the Commission efforts to promote low-carbon technologies. Layering increases institutional complexity in a given policy field, as new elements are added to the existing ones (Capano Citation2019). The degree of (in)coherence among the regulatory and non-regulatory components of the EU policy mixes hence emerges has an important topic for analysis.

Second, the findings of this article highlight the need to broaden the study of EU governance structures beyond its traditional focus on regulatory agencies and European networks of regulators (e.g. Levi-Faur Citation2011; Blauberger and Rittberger Citation2015). As noted above, hybridized forms with a strong element of non-traditional financing have emerged as an instrument to leverage the EU’s governance capacities. The literature on ‘collaborative capacity’ and ‘collaborative arrangements’ offers a possible starting point to consider how the EU catalytic state can mobilize external resources to achieve its objectives and enhance its transformative power (for a review of this literature, see Kekez, Howlett and Ramesh Citation2018). Moreover, the catalytic state perspective offers an entry-point for rethinking how these new governance arrangements influence the locus of power over decision-making in the EU system of governance. The new emphasis on hybridization and innovative financial instruments can have wider implications in terms of democratic accountability and political steering in the overall EU’s institutional architecture. These questions have further relevance against the background of the large-scale EU-level stimulus package in response to the COVID crisis. Although the EU stopped short of issuing so-called Eurobonds, the large-scale borrowing combined with corresponding revenue-raising capabilities represents another major step towards expanding the role of the EU in supporting and reorienting investment. For now, it remains an open question how much power the Commission and the European Parliament will gain over public spending in member states and whether these expanded competences will prove temporary – as demanded by critical observers like Bundesbank President Weidmann – or not. Examining these developments offers important entry-points for future research, both empirically and conceptually.

Finally, the EU as catalytic state approach offers fresh insights on the EU in global political economy. The standard account of the EU’s influence in international affairs is closely linked to its identity (and capacity) as a regulatory state – i.e. the EU as a ‘regulatory power’ (e.g. Bradford Citation2016, 2020). The catalytic state perspective suggests that this approach is no longer sufficient to capture the external impact of the EU. The innovative financial instruments and public-private partnerships of the 2017 External Investment Plan, aimed among other things at confronting China’s Belt and Road Initiative, represent a case in point with it. These and similar initiatives should be subject to further investigation, in order to both empirically map and conceptualize how the EU is evolving as an actor within a changing global landscape. Following Weiss and Thurbon (Citation2021), the rise of the EU catalytic state can be seen as an emerging form of ‘domestically-oriented economic statecraft’ driven by the EU institutions to cope with current geopolitical (e.g. Russia) and geoeconomic (e.g. China) challenges. In this vein, the catalytic state perspective provides an important entry-point for better understanding the EU as global actor and provides a basis for comparing the EU’s economic statecraft to that of other major international actors.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 This is a narrower use of the forms of state concept, which focuses on a specific policy field and a limited set of governance and policy making features. Scholars that adopt a wider use of the forms of state concept, on the other hand, tend to offer comprehensive analyses of the relations among states, markets and society within the capitalist order, including in the area of welfare, social policy and labour relations (e.g. Cerny 1995; Jessop Citation2002). This is the case also for the work on ‘regulatory capitalism’, which has been developed by expanding and reviewing the regulatory state agenda of the 1990s (e.g. Levi-Faur Citation2017). Neo-Polanyian analyses as well adopt this wider use of the forms of state concept. For a Neo-Polanyian perspective on the EU, see Caporaso and Tarrow (Citation2009).

2 See ‘Europe 2020: A strategy for smart, sustainable and inclusive growth’, available at: https://ec.europa.eu/eu2020/pdf/COMPLET%20EN%20BARROSO%20%20%20007%20-%20Europe%202020%20-%20EN%20version.pdf (accessed 6 April 2021).

3 See the data on the EU budget available at: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/sites/eco_surveys-eur-2018-3-en/index.html?items-eur-2018-3-en (accessed 2 May 2021).

4 On the emphasis on the use of authority-based instruments by the regulatory state, see also Hood et al. Citation1999.

5 Investment platforms can provide loans, guarantees and/or equity financing for implementing projects in the member states. In 2018, there were forty-one platforms operative (European Commission Citation2018). Several of them target climate and energy action, including the Marguerite II Fund, which is a pan-European equity fund.

6 See ‘Innovation Fund’, available at: https://ec.europa.eu/clima/policies/innovation-fund_en, accessed 24 April 2021.

References

- Bach, D., Newman, A.L., and Weber, S., 2006. The international implications of China’s fledgling regulatory state: from product maker to rule maker. New Political Economy, 11 (4), 499–518.

- Begg, I., 1996. Regulation in the European Union. Journal of European Public Policy, 3 (4), 525–535.

- Blauberger, M., and Rittberger, B., 2015. Conceptualizing and theorizing EU regulatory networks. Regulation & Governance, 9 (4), 367–376.

- Block, F., 2008. Swimming against the current: the rise of a hidden developmental state in the United States. Politics & Society, 36 (2), 169–206.

- Block, F., and Keller, M., eds. 2011. State of innovation. The U.S. government’s role in Technology development. London: Routledge.

- Bowman, M., 2017. Capitalising on the Juncker Fund: Mobilising Private Climate Finance for Sustainability. TLI Think 79/2017.

- Bradford, A., 2016. The EU as a regulatory power. In: M. Leonard, ed. (2016) connectivity wars: Why migration, finance and trade are the geo-economic battlegrounds of the future. London: ECFR, 133–141.

- Bradford, A., 2020. The Brussels effect: How the European Union rules the world. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Buzan, B., and Lawson, G., 2014. Capitalism and the emergent world order. International Affairs, 90 (1), 71–91.

- Capano, G., 2019. Reconceptualizing layering –from mode of institutional change to mode of institutional design: types and outputs. Public Administration, 97 (3), 590–604.

- Caporaso, J., 1996. The European Union and forms of state: westphalian, regulatory or post-modern? Journal of Common Market Studies, 34 (1), 29–52.

- Caporaso, J.A., and Tarrow, S., 2009. Polanyi in Brussels: supranational institutions and the transnational embedding of markets. International Organization, 63 (4), 593–620.

- Cerny, P.G., 1997. Paradoxes of the competition state: The dynamics of political globalization. Government and Opposition, 32 (2), 251–274.

- Cerny, P.G., 2000. Restructuring the political arena: globalization and the paradoxes of the competition state’. In: R. D. Germain, ed. Globalization and its critics. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 117–138.

- Clift, B., 2014. Comparative political economy: states, markets and global capitalism. London: Palgrave-Macmillan.

- Coen, D., and Thatcher, M., 2008. Network governance and multi-level delegation: European networks of regulatory agencies. Journal of Public Policy, 28 (1), 49–71.

- Colli, A., Mariotti, S., and Piscitello, L., 2014. Governments as strategists in designing global players: the case of European utilities. Journal of European Public Policy, 21 (4), 487–508.

- Dannreuther, R., 2015. Energy security and shifting modes of governance. International Politics, 52 (4), 466–83.

- Directorate-General for Internal Policies (DG-IPO). 2017. Research for REGI committee – cohesion policy and Paris Agreement targets. Brussels: European Parliament.

- Eberlein, B., and Grande, E., 2005. Beyond delegation: transnational regulatory regimes and the EU regulatory state. Journal of European Public Policy, 12 (1), 89–112.

- Eliadis, F. P., Hill, M. M., and Howlett, M. P., 2005. Designing government: from instruments to governance. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s Press-MQUP.

- EPEC. 2016. Blending EU Structural and Investment Funds and PPPs in the 2014-2020 Programming Period. Available from https://www.eib.org/attachments/epec/epec_blending_ue_structural_investment_funds_ppps_en.pdf

- European Commission. 2008. Memo on the European Economic Recovery Plan, Brussels, 26 November 2008. Available from https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/MEMO_08_735

- European Commission. 2010a. Report on the Implementation of the Trans-European Energy Networks in the Period 2007–2009, SEC (2010) 505 final.

- European Commission. 2010b. Energy Infrastructure Priorities for 2020 and Beyond. A Blueprint for an Integrated European Energy Network, COM (2010) 677/4.

- European Commission. 2018. Investment Platforms. Available from https://ec.europa.eu/commission/sites/beta-political/files/investment_platforms_factsheet_en.pdf

- European Commission, 2019. On the implementation of the strategic action Plan on batteries: Building a strategic Battery value chain in Europe. Brussels: COM. 2019) 176 final.

- European Commission, 2020. A New Industrial Strategy for Europe. Brussels: COM. 2020) 102 final.

- Genschel, P., and Jachtenfuchs, M. eds, 2014. Beyond the regulatory polity? The European integration of core state powers. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Genschel, P., and Jachtenfuchs, M., 2016. More integration, less federation: the European integration of core state powers. Journal of European Public Policy, 23 (1), 42–59.

- Goldthau, A., and Sitter, N., 2015a. A liberal actor in a realist world: The European Union regulatory state and the global political economy of energy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Goldthau, A., and Sitter, N., 2015b. Soft power with a hard edge: EU policy tools and energy security. Review of International Political Economy, 22 (5), 941–965.

- Hix, S., and Lord, C., 1997. Political parties in the European Union. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Hood, C., 1983. The tools of government. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Hood, C., et al., 1999. Regulation inside government. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Jänicke, M. and Quitzow, R., 2017. Multi-level reinforcement in European climate and energy governance: mobilizing economic interests at the sub-national levels. Environmental Policy and Governance, 27 (2), 122–136.

- Jessop, B., 2002. The future of the capitalist state. Cambridge: Polity.

- Jordan, A.J., et al., 2011. Environmental policy: governing by multiple policy instruments? In: J.J Richardson, ed. Constructing a policy state? policy dynamics in the EU. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 104–124.

- Kekez, A., Howlett, M., and Ramesh, M., 2018. Varieties of collaboration in public service delivery. Policy Design and Practice, 1 (4), 243–252.

- Levi-Faur, D., 2009. Regulatory capitalism and the reassertion of the public interest. Policy and Society, 27 (3), 181–191.

- Levi-Faur, D., 2011. Regulatory networks and regulatory agencification: towards a Single European regulatory space. Journal of European Public Policy, 18 (6), 810–829.

- Levi-Faur, D., 2013. The odyssey of the regulatory state: from a “thin” monomorphic concept to a “thick” and polymorphic concept. Law & Policy, 35 (1-2), 29–50.

- Levi-Faur, D., 2017. Regulatory capitalism. In: P. Drahos, ed. Regulatory theory: foundations and applications. Canberra: ANU Press, 289–302.

- Lind, M., 1992. The catalytic state. The National Interest, 27 (Spring), 3–12.

- Lodge, M., 2008. Regulation, the regulatory state and European politics. West European Politics, 31 (1-2), 280–301.

- Majone, G., 1994. The rise of the regulatory state in Europe. West European Politics, 17 (3), 77–101.

- Majone, G., 1996. Regulating Europe. London: Routledge.

- Majone, G., 1997. From the positive to the regulatory state: causes and consequences of changes in the mode of governance. Journal of Public Policy, 17 (2), 139–167.

- Majone, G., 1999. The regulatory state and its legitimacy problems. West European Politics, 22 (1), 1–24.

- Mazzucato, M., 2015. The entrepreneurial state: debunking public vs. private sector myths. New York: Public Affairs.

- McGowan, F., and Wallace, H., 1996. Towards a European regulatory state. Journal of European Public Policy, 3 (4), 560–576.

- McNutt, K., and Rayner, J., 2010. Nodality in Policy Design: The Impact of Ideas in Two Policy Sectors. Paper presented at the ECPR Joint Sessions of Workshop, March 22-27, Munster, Germany

- Mertens, D., and Thiemann, M., 2018. Market-based but state-led: The role of public development banks in shaping market-based finance in the European Union. Competition & Change, 22 (2), 184–204.

- Mertens, D., and Thiemann, M., 2019. Building a hidden investment state? The European investment bank, national developments banks and European economic governance. Journal of European Public Policy, 26 (1), 23–43.

- Prontera, A, 2019. Beyond the EU Regulatory State: Energy Security and the Eurasian Gas MarketLondon: ECPR Press-Rowman and Littlefield.

- Prontera, A. and Plenta, P., 2020. Catalytic power Europe and gas infrastructural policy in the Visegrad countries. Energy Policy, 137, 111189.

- Rayner, T., and Jordan, A., 2013. The European Union: the polycentric climate policy leader? Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change, 4 (2), 75–90.

- Schmidt, V.A., 2009. Putting the political back into political economy by bringing the state back in yet again. World Politics, 61 (3), 516–546.

- Scott, C., 2005. Regulation in the age of governance: The rise of the post-regulatory state. In J. Jordana and D. Levi-Faur, eds. The politics of regulation: institutions and regulatory reforms for the age of governance. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, pp. 145–167.

- Streeck, W., and Thelen, K., 2005. Beyond continuity: institutional change in Advanced political economies. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Szulecki, K, et al., 2016. Shaping the ‘Energy Union': between national positions and governance innovation in EU energy and climate policy. Climate Policy, 16 (5), 548–567.

- Thurbon, E., and Weiss, L., 2021. Economic statecraft at the frontier: Korea’s drive for intelligent robotics. Review of International Political Economy, 28 (1), 103–127.

- Vakulchuk, R., Overland, I., and Scholten, D., 2020. Renewable energy and geopolitics: a review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 122, art. 109547.

- Van De Graaf, T, et al., 2016 The Palgrave handbook of the international political economy of energy. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Versluis, E., Van Keulen, M., and Stephenson, P., 2010. Analysing the European Union policy process. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Vogel, S.K., 2018. Marketcraft: How governments make markets work. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Weiss, L., 1998. The Myth of the Powerless state. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Weiss, L., 2006. Infrastructural power, economic transformation, and globalization. In: J. A. Hall, and R Schroeder, eds. An anatomy of power: the social theory of Michael Mann. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 167–186.

- Weiss, L., 2010. Globalization and the Myth of the Powerless state. In: G. Ritzer, and Z Ataly, eds. Readings in globalization. Key concepts and major debates. West Sussex, UK: Wiley-Blackwell, 166–175.

- Weiss, L., 2014. America Inc.? innovation and enterprise in the national security state. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Weiss, L. and Thurbon, E., 2021. Developmental state or economic statecraft? Where, why and how the difference matters. New Political Economy, 26 (3), 472–489.