ABSTRACT

The fate of British finance following the Brexit referendum revolves around the ‘resilience or relocation’ debate: will the City of London continue to thrive as the world’s leading financial centre or will the bulk of its activity move to rival hubs after departure from EU trading arrangements? Despite extensive commentary, there remains no systematic analysis of this question since the Leave vote. This paper addresses that lacuna by evaluating the empirical evidence concerning jobs, investments, and share of key trading markets. Contrary to widely-held expectations, the evidence suggests that the City has been remarkably resilient. Brexit has had no significant impact on jobs and London has consolidated its position as the chief location for financial FDI, FinTech funding, and attracting new firms. Most unexpectedly, the City has increased its dominance in major infrastructure markets such as over-the-counter clearing of (euro-denominated) derivatives and foreign exchange—although it has lost out in the handling of repurchase agreements and share trading. Based upon this evidence, the paper argues that London’s resilience is mainly a function of its status as a crucial ‘agglomeration peak’ of global finance which shelters its unique ecosystem from the typical pressures of capital flight.

Introduction

Resilience or relocation is the dominant frame of discussion concerning the potential impact of Brexit on the City of London.Footnote1 The argument for relocation is straightforward: as the City loses passporting rights to EU member states (henceforth, EU27), it will not only lose lucrative business, but also be diminished in its relative competitiveness and standing as the world premiere financial hub. Indeed, for a majority of analysts, the die is already cast, as firms and investors have been preparing since the Leave vote for ‘day one’ of the UK’s Single Market exit. Journalistic commentary in this vein is abundant and garners support from a growing range of policymaking and academic analyses, while dissenting voices are scarce.

The discussion revolves around a cluster of core questions: how many jobs have moved since the June 2016 referendum and how many more will follow? What firms are expanding EU27 operations, and how has the vote impacted financial Foreign Direct Investment (FDI)? In particular, what are the calculations of major (especially, US) investment banks who use London as their primary base of activity? Furthermore, what will be the fate of London’s celebrated infrastructure markets involving the clearing of over-the-counter (OTC) derivatives and currency trading? How much of this business will be lured to, for example, Euronext Paris or Deutsche Börse/Eurex in Frankfurt?

A major deficiency in these discussions, however, is that they often occur at the level of anecdote. This is particularly the case throughout the business press as reports highlight isolated instances of transfer and relate this back to (unsubstantiated) claims that relocation is inevitable. Even when sophisticated analyses appear, they overwhelmingly focus on one direction of travel, from the City to the continent, rather than transfers going the opposite way. The same applies to the multiple professional impact assessments (discussed below) that made stark claims concerning the amount of jobs and investment that would immediately flee following a vote to Leave. In short, what is lacking is a more systematic analysis of the empirical evidence for relocation that has (or has not) occurred since the referendum. That is a central purpose of this paper.

Through a detailed analysis of recent market trends across jobs, investment, and share of key trading markets, this study serves to recalibrate the ‘relocation vs. resilience’ debate, challenging some core assumptions and expectations. Specifically, the paper demonstrates that the widespread claim of London being significantly damaged in the years following the referendum is false. Rather, in jobs, there has been no noticeable effect; in investments, the City remains exceptionally robust in FDI, Fintech funding, and in attracting financial firms; and in the share of trading markets, the City has dramatically increased its dominance across several of the most important transactions.

Through analysis of the areas in which the City has been most successful, I contend that the resilience of UK financial services is best explained through two theoretical frameworks. First, the perspective of London as a knowledge-based ‘big city agglomeration peak’ which offers investors unique advantages such as compressed transaction costs, strong legal protections, superior technical expertise, and other positive network externalities. Crucially, it is extremely challenging for EU27 hubs to replicate, and for market participants to replace, this unique ecosystem, thus providing the City a significant measure of immunity from the typical constraints of capital flight. Second, the evidence suggests that a key aspect of London’s durability is further explained by its close ties to the US financial sector—in particular, the ongoing commitment of major Wall Street investment banks to maintain their City-based headquarters and operations, but also the willingness of US-based investors to continue providing outsized levels of FDI and FinTech funding.

In conducting this analysis, the paper acknowledges that Brexit has set in motion a range of financial transformations that will only be possible to fully comprehend with the benefit of hindsight over the coming years and decades. In this respect, the analysis offers no prediction as to what kind of damage will or will not happen to the City (or conversely, EU27 centres) going forward. Indeed, the deeply political nature of Brexit renders the situation inherently unpredictable, while much remains to be resolved in ongoing negotiations—for finance in particular, equivalence determinations.Footnote2 Nevertheless, as both future scholarship and policy choices are unavoidably premised upon prior investigation, this study does serve to temper some of the more pessimistic expectations regarding the future prospects of London.

The paper proceeds in six parts. The first section gives an overview of the resilience vs. relocation debate, followed by three sections that assess the empirical evidence sequentially across jobs, investments, and trading markets over the past five years. The fifth section elaborates on several theoretical frames that best account for the durability in London’s financial prominence—most importantly, London’s special status as a knowledge-based ‘agglomeration peak’ that EU27 hubs are unable to replicate. It also highlights the relevance of long-standing Anglo-American ties that bolster London’s global prominence in financial services. The conclusion indicates several directions for future research.

The prospects of relocation

The central theme concerning Brexit and finance is the prospect of a relocation of services from the City to mainland European hubs. The conventional wisdom is that, in the aftermath of the 2016 vote, not only are firms preparing to relocate in order to continue servicing EU27 clients (Pesendorfer Citation2020, pp. 193–245) but national and regional authorities are making proactive efforts to help their respective centres in luring business from London (Cassis & Wójcik Citation2018, Howarth and Quaglia Citation2018). In a typical rendition of this argument, Lavery et al. (Citation2019, p. 1516) conclude that European financial centres are ‘set to benefit’ from the impending UK-EU decoupling, despite the likelihood that overall transaction costs will increase for businesses, states, and households.

This perspective is supported by most policymaking commentary. In the ominously titled ‘When the banks leave’, financial markets specialist Nicholas Verón (Citation2017) declares that ‘harm is now unavoidable’ for the City which will ‘suffer relative both to its competitors and to how it would have performed without Brexit and probably in absolute terms as well’. While London may succeed in retaining domestic business, the author predicts at best a ‘permanent loss of most of the City’s EU27-related business’, and at worst, a loss of its international activities also. Further pessimistic assessments are abundant across expert commentary, with one report after another expecting significant damage to London’s standing (PwC Citation2016, Schoenmaker Citation2017, Wright et al. Citation2019a). This narrative is also ubiquitous within journalistic reporting, as a plethora of articles anticipate and track the transfer of jobs and investment from London to rival centres (e.g. Jenkins and Morris Citation2018).

Another factor considered damaging to the City’s interests is the UK’s particularly weak negotiating position. Unlike the EU’s purported consistency in financial aims, the conflicted (and heavily constrained) preferences of Britain’s main players—the government, regulators, and private finance—are perceived as undermining the UK’s bargaining influence. As a result, James & Quaglia argue that ‘the costs of no agreement remain significantly higher for the UK than for the EU, and have increased steadily over the course of the Brexit negotiations’ (Citation2018, p. 566).

In light of these claims, observers often present Brexit in terms of national self-sabotage (Toporowski Citation2017) and infer that the political influence of the financial sector has waned. It is claimed, for instance, that several policymaking contingencies—e.g. party management, institutional reorganisation, sectoral factionalism—has overwhelmed the structural power of British finance, and led to the pursuit of a harder Brexit than the City hoped (James and Quaglia Citation2019a). Others see Brexit as a critical juncture that, in combination with the reputational damage from the 2007/08 crash, marks a fundamental decline in the policymaking influence of City-based elites (Thompson Citation2017, Rosamond Citation2019).

Finally, taking stock of these perspectives, several leading authors have contemplated more broadly the potential decline or restructuring of the distinctive UK growth model, based as it is so prominently on the existence of a thriving financial services sector (See Hay and Bailey Citation2019).

Despite this general consensus, a handful of authors question these claims. Ringe argues that while Brexit appears damaging, experience of EU law-making suggests that it will turn out to be an ‘irrelevance’ due to the mutual interest of both British and EU policymakers in preserving open financial relations. As such, ‘creative solutions’ that formally satisfy the withdrawal procedure will, in substance, keep London closely connected to EU markets (Citation2018, p. 22). Offering empirical support for this proposition, Kalaitzake (Citation2021) documents how a wide range of financial contingency arrangements were designed by UK and EU policymakers when threatened with the prospect of a ‘disorderly’ no-deal Brexit in early 2019—many of which remain in place after the UK’s final exit in January 2021. Leveraging a concept of ‘structural interdependence’, Kalaitzake argues that the prospect of mutual economic harm persuades policymakers to avoid severing the most deep-rooted ties between London and EU corporates.

More broadly, Talani (Citation2019) maintains that the combination of London’s unique competitive strengths with a favourable set of government interventions and supports, will allow the City to prosper globally through a strategy of ‘pragmatic adaptation’. In addition, Lysandrou et al. outline the huge advantage of scale in liquidity that London holds over its EU27 competitors, rendering it ‘unlikely that … relocation [from London] will occur any time soon’ (Citation2017, p. 173). This view is supported by a minority of policy commentators who show that future equivalence decisions can substantially mitigate the most serious damage to the City’s commercial interests (Scarpetta and Booth Citation2016), and indeed, is a better strategic goal for the UK government, rather than becoming a straight ‘rule taker’ of post-Brexit EU regulations (Armour Citation2017).

Largely missing from these discussions, however, is a systematic empirical analysis of how the City of London is actually faring since the referendum. That is to ask, how much ‘relocation’ has actually occurred thus far, and how is London holding up compared to continental rivals? Of course, there is an unspecified time-lag in any movement of business across jurisdictions, especially as the UK’s formal exit from the Single Market was only fully completed in January 2021. Nevertheless, the five years since the UK’s decision to leave offers a substantial period of time to identify prominent trends within financial sub-sectors and track relocation across several domains of market activity.Footnote3

Crucially, analysts warned that the transfer of services would begin immediately after the referendum and continue throughout the negotiation process. This is because companies had to plan in advance for ‘day one’ of business with the City outside of the EU27 bloc. Such urgency was exacerbated by EU authorities pressurising firms to implement contingency preparations as soon as possible and warning them to not rely on policy interventions that might allow them to continue operating as normal after the transition period (European Banking Authority Citation2018). Moreover, many commentators contended that the uncertainty arising from drawn-out negotiations resulted in major damage to the City’s financial standing (Wright et al. Citation2019b).

In short, if the thesis of relocation is correct, one would expect the data to illustrate that, at a minimum, there has been a distinctive movement (if not a full-blown flight) of financial activity from London to the EU mainland as businesses implement their post-settlement preparations. In evaluating this expectation, then, the following section examines the rationale and evidence for relocation across three areas: jobs, investment, and trading markets share. Each area is a key discussion point of those warning of relocation and the damaging impact of Brexit of the future of London.

Jobs

Within commentary on relocation, jobs are the most commonly used proxy for analysing the future fate of the City. lists several prominent reports that have projected the amount of financial sector job losses that will result from Brexit, displaying a general trend downwards in expected losses as time passes.

Table 1. Estimated job losses in prominent impact assessments

The most widely circulated estimate of job losses came from a PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC) report published in April 2016, and is consistently cited within both academic and non-academic academic literature (PwC Citation2016). The report estimated that, under a Leave scenario, 70,000-100,000 financial jobs would be lost by the year 2020. Crucially, this figure was presented a near term prediction, with long term labour market adjustments mitigating that loss by 10,000-30,000 by the year 2030.Footnote4

Soon after the referendum, an Oliver Wyman (Citation2016) assessment estimated that, with a retention of full passporting rights,Footnote5 the UK could limit job losses to a negligible 3,500. However, under a scenario more aligned to how negotiations have actually developed—whereby the UK becomes a third country but (potentially) gains EU27 access through equivalence, delegation,Footnote6 and/or bilateral agreements—the report projects employment losses of 31-35,000.Footnote7 By the end of 2016, an Ernst & Young (EY) report—circulated widely among government officials—envisaged losses closer to the PwC tally. Focusing on the prized euro-denominated clearing market, the report speculated that within eight years, 30,000 jobs would flow from the UK to alternative ‘core intermediary’ positions abroad. In addition, losses of 15,000 in wealth management and similar numbers in both related professional and technology roles would bring the cost to 83,000. As a driving sector of the UK economy, these job losses are expected to produce a domino effect, ultimately costing 232,000 jobs across the entire UK economy by 2024 (Stafford Citation2016).

Throughout 2017, estimates began to moderate. In February, Bruegel declared that ‘30,000 people might relocate from London to the EU27’ with 10,000 losses in wholesale banking and the remainder connected to supportive professional roles (law, auditing, technology) (Batsaikhan et al. Citation2017). Later in the year, EY’s new Brexit ‘job tracker’ predicted that 10,500 jobs would be lost on ‘day one’ (Treanor Citation2017). However, estimates continued to be pared back when it became clear that the expected levels of relocation were not occurring and officials such as Ian McCafferty (a senior BoE economist) were publicly taken to task for groundless claims of an ‘exodus’ of workers from the City to Europe (McCafferty Citation2018). In July 2018, the City of London Corporation lowered their expectations to between 5000-13,000 positions migrating before the exit date of March 2019 (BBC Citation2018) while the BoE stated their revised view that approximately 5000 jobs would relocate before the UK’s departure (Jones Citation2018a).

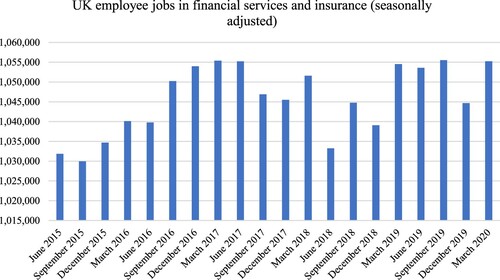

As illustrates, the referendum aftermath has caused no significant harm to overall employment levels in the UK financial sector. In the four quarters directly after the Leave vote, job levels in financial services proper (i.e. exclusive of related professional services) increased considerably to reach an overall employment level of 1,055,000—approximately 15,000 jobs more than at the time of the referendum in June 2016. While employment levels did take a noticeable drop in the summer of 2018, they quickly recovered to previous peak levels again in early 2019. As such, current levels of employment are substantially higher than they were before the referendum.

Figure 1. UK employment in financial services post-Brexit referendum. Source: NOMIS official labour market statistics.

Confirmation of the stability in UK financial sector employment also comes indirectly from tax receipts generated by the sector. According to annual reports by the City of London Corporation, the overall tax contribution from finance to the UK government has experienced a steady yearly increase since 2010 and hit a record of £75.5bn in 2019. This compares with a tax intake of £66bn during 2015, or rather, an increase of 14% since around the time of the Brexit referendum. Particularly revealing is the fact that the largest component of this intake comes from employment taxes, constituting £34.5bn (or 46%) of total financial sector tax receipts. As UK financial employees represent only 3.2% of the total workforce, yet consistently make up approximately 11% of overall government receipts, the latest Corporation report declares the financial sector to be a ‘significant and stable contributor to the UK’s tax take’ (City of London Corporation Citation2019).

Crucial to the resilience of UK financial sector employment is that fact that major financial firms—in particular, large City-based investment banks—substantially revised their initial plans to move jobs to the continent. As reported by Bloomberg in 2019, virtually all of the major investment banks dramatically scaled back their level of employees flagged for relocation. For instance, the three banks that indicated the largest level of Brexit transfers (JP Morgan, Deutsche Bank, and UBS) lowered their combined transfers from 9,500 employees to just 1,100 (Finch et al. Citation2019). Moreover, these reduced figures constituted planned relocations, meaning that many of them may well not materialise. Indeed, a persistent fear of EU regulators is that financial firms are establishing ‘empty shell’ operations within their jurisdictions while keeping the bulk of their employees within the UK (Morris and Brunsden Citation2019).

Verification of the broad non-relocation of these jobs comes from the EY Brexit tracker which showed that, by September 2019, a mere 1000 positions had been transferred by the major UK-based investment banks—movements characterised as a ‘trickle’ rather than the expected ‘exodus’ (Brush Citation2019). As such, EY again revised their predictions downwards to indicate that only 7000 jobs would relocate ‘in the near future’—the most commonly accepted estimate at present (Jones Citation2019). Moreover, this did not account for the considerable number of jobs that seemed likely to migrate into London as a result of EU27 firms seeking assured access to the City, post-Brexit (p. 7 below).

Further corroboration of London’s job resilience emerges from a recent survey of top banks and asset management firms conducted by the Financial Times for their ‘Future of the City’ series in December 2020 (Noonan et al. Citation2020). In this analysis, the majority of firms surveyed had actually increased their UK headcount since the 2016 referendum (e.g. Goldman Sachs, BNP Paribas, UBS) while the few that reduced numbers did so primarily because of group-wide restructurings (e.g. Credit Suisse and Deutsche Bank).

Most striking, however, are the figures reported by asset management firms, nine out of twelve of which were found to have ‘ramped up hiring’ since the referendum and increased their combined employment level by a startling thirty-five per cent. This included major players such as PIMCO—the world’s leading bond fund—as well as Vanguard—the world’s second largest asset manager.Footnote8 These developments are all the more remarkable considering that, in 2017, a similar survey of fund investors and mangers showed that they expected the UK to lose approximately twenty per cent of its asset management jobs by the year 2020 (Flood Citation2017).

In short, there is no compelling evidence to date that the Leave decision, or for that matter, the persistent uncertainty surrounding Brexit negotiations, has had any significant impact on UK financial sector employment levels. Instead, raw numbers of financial sector employment are unambiguously higher, tax receipts for financial services have maintained a steady climb, and targeted surveys reveal that a preponderance of top firms have actually increased their overall employee headcount within the UK.

Investments

On investments, analysts stress that financial firms have flagged approximately £1 trillion of assets for relocation from London to the continent—albeit, again, mostly referring to planned rather than actualised transfers. Using these intentions as a baseline expectation, however, commentators have looked beyond jobs to assess the gradual transfer of firms’ operations and activities which could serve as the ‘building blocks’ to more permanent business on the continent (Brush Citation2019). Once more, the actions of large investment banks are a central focus and there has been a constant stream of reporting on banks expanding operations and buying office space in alternative EU centres, as well as speculation over which city is the main beneficiary of Brexit. For instance, Morgan Stanley’s application for a German license spurred the contention that Frankfurt would be the firm’s new post-Brexit hub, as did the intention by Barclays, Lloyds, and Citigroup to increase operations there. Alternatively, the discussion turns to Paris due to its similar post-Brexit attraction of big names such as Bank of America, Goldman Sachs, and HSBC, and its status as a major world metropolis (unlike Frankfurt) that can attract global talent (Jenkins and Morris Citation2018).

More detailed industry reports, however, indicate that smaller European centres are coming out on top. According to a widely publicised New Financial assessment, Dublin is the ‘clear winner’ based on a comprehensive analysis of the 332 UK-based firms who have either relocated a part of their business or flagged their intention to set up new EU27 entity (Wright et al. Citation2019a, Citation2019b). Between 2016-2019, Dublin had 115 firms choose it as their destiny (constituting 28% of all actions), while Luxemburg came in second place with 71 firms. Paris and Frankfurt were third and fourth (69 and 45 firms respectively), and Amsterdam fifth (40 firms). A key reason for the success of Dublin and Luxemburg is the fact that they attract asset management firms—entities that are relatively more mobile and have been the most active in advancing cross-border preparations since the referendum.Footnote9 By contrast, Frankfurt attracts the most banking-orientated firms, Amsterdam is a particular draw for exchanges and broking firms, while Paris attracts a mixture of firm types. Based on this activity, the report predicts that these locations will ‘gradually chip away at the UK’s influence in the banking and finance industry not just in Europe but around the world’ (Citation2019a, p. 3).

However, the chief deficiency of such studies is that they significantly underestimate potential investments coming into the United Kingdom as a result of Brexit. This has been highlighted in stark fashion by a research investigation by the financial consultancy, Bovill. Based upon a Freedom of Information request, the consultancy shows that the UK’s Temporary Permissions Regime (TPR)—a transition scheme allowing firms to continue inbound passporting to the UK after Brexit, and until they receive full authorisation from British regulators—attracted an extraordinary 1,441 applications from financial firms. Crucially, more than one thousand (83%) of these firms currently use the EU passporting mechanism to offer services within the UK, meaning that these applications express the intention to set up some form of physical presence in the UK after the exit date. As noted by a partner at Bovill, ‘in practical terms … European firms will be buying office space, hiring staff and engaging legal and professional advisers in the UK’ (Bovill Citation2020). Moreover, the TPR has attracted firms operating across the full gamut financial subsectors and within every EU27 country—though, in particular, asset managers, payment service providers, and insurance/insurer intermediaries, and with over a third of firms hailing from Ireland, France, and Germany combined.Footnote10

Another counter to the investment relocation claim comes from EY’s yearly attractiveness surveys, which offer an assessment of UK FDI performance relative to other countries in Europe (EY Citation2019a, EY Citation2019b). Comparing data from 2017 and 2018, while the UK economy as a whole lost significant ground in total FDI attraction—declining 13% in FDI projects compared to a fall of just 4% in Europe—finance was a major outlier. Within financial services, UK FDI projects registered an exceptional 44% increase over the previous year by attracting 112 projects—the most ever recorded in the annual survey—and increasing the UK’s pan-European share of financial sector FDI to 27% (). Noteworthy, however, is the fact that this occurred in the context of a simultaneous rise in outward FDI by UK-based financial firms to continental Europe—albeit at a considerably more modest rate of 16%. What this suggests is that, while financial firms are certainly expanding their EU27 operations, it is not at the expense of overall investment going to the City.

Table 2. Total UK and EU27 FDI projects and % change, 2017-2018

Furthermore, the UK report’s concomitant survey of investors exhibits positive sentiment for the City with 22% of respondents believing that financial services will ‘drive the UK’s growth in the coming years’, compared to a score of just 13% for the digital economy and for 12% business services, coming in second and third place, respectively (EY Citation2019a, p. 36).

EY’s latest attractiveness survey (released in May 2020) confirms a similar picture, with the UK’s overall share of pan-European financial FDI inflows holding stable at 27%, this time attracting 99 projects—more than double the number of Germany in second place with 43. Moreover, London again registered as the top performing European city, accounting for 67 of all UK projects, compared to just 29 projects for second-placed Paris (Luttig Citation2020, EY Citation2020a, EY Citation2020b). As noted by EY’s Managing Partner for Financial Services, Omar Ali, the UK’s 2019 financial FDI levels were ‘the third strongest this decade and the UK has extended its lead over the rest of Europe despite Brexit, which is impressive.’ (Quoted in Luttig Citation2020).

While the resilience of investment into the UK financial sector involves a complex range of factors, at least two aspects deserve special attention: first, the ongoing commitment of large investment banks, and second, tech-related investment.

While there is an inordinate level of focus on large banks seeking to expand EU27 operations, significantly less attention is given to actions that link their future to the City, irrespective of Brexit. The most important of these come from the top US investment banks. In 2019, Goldman Sachs unveiled their new European HQ right in the centre of the City’s square mile—a £1.2bn, ten-storey state-of-the-art complex that now houses London’s largest trading floor and brings 6,500 employees under one roof. Similarly, despite leasing extra space in Paris in 2017, in February 2018, Bank of America extended their London HQ lease for another 10 years (until 2032). When queried on the firm’s reasoning in the context of Brexit, CEO Brian Moynihan replied: ‘I think it [Brexit] is a negative, but I don’t think it is a strong negative’ (Sidders Citation2018).

The same applies to JP Morgan, who recently purchased a new office in Paris to ‘continue to serve European-based clients seamlessly’. Nevertheless, the bank’s Chairman for French operations stressed that ‘London will still be number one’—a statement verified by the fact that, while JP Morgan has approximately 12,000 employees in London (and 19,000 across the UK), it has just 260 employees in Paris, with room for only 450 more at the new location (Morris and Pooler Citation2020). These moves indicate that, while major banks are willing to use their substantial resources to expand EU27 operations and retain commercial flexibility, this should not be taken to mean that they have any intention of severing their ties with London.

Other large US and non-US firms have made comparable long-term, post-referendum investments in the City: Citigroup bought a 45-floor skyscraper at Canary Wharf for £1.2bn, Wells Fargo purchased a new site to function as their main base for future EMEA (Europe, Middle East, and Africa) operations, and Sumitomo (Japan’s second largest bank) agreed a new 20-year lease for their London HQ (Blackman Citation2018, Burke Citation2018, Spink Citation2019). Even the major banks in Germany and France (Deutsche Bank, BNP Paribas, Société Générale, Credit Agricole) have all confirmed that London will continue to be a central plank of their post-Brexit operations (Evans Citation2017, Landauro Citation2018).

In tech-related investment, there is no question that, despite Brexit, London continues to thrive as the leading European hub for FinTech development—assumed to be the main driver of financial innovation over coming decades. In a 2019 EY census report (comparing 2019 with 2017 data) the report shows that UK FinTech companies increased their average investment by a third over those two years (EY Citation2019c). Growth prospects were also found to be exceptionally strong with over a fifth of companies projecting growth of 200% over the next year and a third of firms expecting an IPO over the next five years. Similarly, Brexit did not disrupt London’s superior production of Fintech ‘unicorns’—start-up firms that achieve a valuation greater than $1bn. Between 2016-2019, the UK witnessed the development of nine FinTech unicorns, including major online challenger banks such as Revolut and Monzo. By contrast, Germany produced three, while France produced none.Footnote11

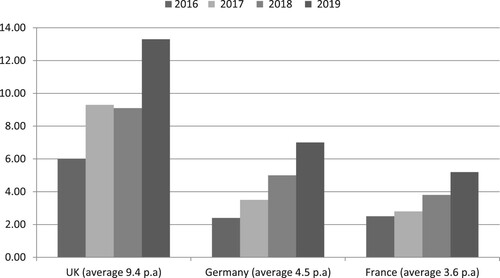

FinTech is undoubtedly the spearhead of London’s ability to attract investment into technology more generally. According to a comprehensive analysis of venture capital investment data over the last six years, the UK has consistently increased its lead over its core European rivals, driven primarily by longstanding links with the US investment community (Tech Nation Citation2019, p. 5). On average, between 2016-2019, the UK secured $9.4bn annually in venture capital investment, compared to just $4.5bn in Germany and $3.6bn in France (). In FinTech specifically—designated as one of the three ‘key tech sub-sectors’ along with AI and cleantech—the UK saw an enormous 96% increase in its venture capital investments from 2018-2019, compared to a 73% and 61% rise in Germany and France, respectively (Tech Nation Citation2020).

Figure 2. Venture capital investment 2016-2019, including averages, in UK, Germany, France (billions of US dollars). Source: Tech Nation Citation2020.

Overall, then, there is a slightly more nuanced story in the area of investment compared to jobs. On the one hand, it is definitely true that some UK-based firms—in particular, mobile asset management firms and large banks—have made multiple relocations to ensure continuity in operational capacities across EU27 jurisdictions. However, this has not negatively impacted UK financial FDI levels which remain exceptionally robust and clearly show that the UK is not losing ground relative to their continental rivals. On the contrary, UK investment in key areas like FinTech continues to outstrip that of its EU27 competitors by a considerable margin, while the number of firms looking to establish a presence in the UK after Brexit appears to match or exceed those moving in the opposite direction. Similarly, the continuing operational expansion of global investment banks in their UK headquarters is a key marker of the long-term confidence placed in the City.

Trading markets share

One of the most frequently cited threats facing the City is the prospect of losing market share in the lucrative ‘market infrastructure’ business in which London holds a dominant international position. In particular, this relates to the high proportion of derivatives trading and foreign exchange (FX) currency activities handled by the City’s major dealers and central counterparties (CCPs). Even more specifically, it refers to the vast number of euro-denominated transactions managed and cleared by London, and which would fall outside the EU’s supervisory purview after Brexit.

In terms of London’s dominant position, note that, at the time of the 2016 referendum, UK dealers handled 78% of all FX trading executed within the EU, including 43% of (global) euro foreign transactions and 69% of EU-based euro currency trading (ECB Citation2017, p. 29). Overall, this meant London traded approximately twice the number of euros than all of the Eurozone countries combined. Similarly, UK CCPs cleared 82% of all EU-traded Interest Rate Derivatives (IRDs)—by far the most commonly used derivative by corporates and investors—and 75% of euro-denominated IRD’s (PwC Citation2018, p. 7). More generally, UK markets cleared 70% of all euro-denominated over-the-counter (OTC) derivatives compared with French clearing of 11% and German clearing of 7% (European Parliament Citation2017, p. 47).

Nevertheless, damage to London’s position is often considered an inevitability. Schoenmaker, for instance, specifies euro-denominated clearing in derivatives as the market segment that will face the ‘greatest impact’, speculating that up to half of the City’s OTC IRD transactions ‘could move to continental Europe after Brexit’ (2017, pp. 10–11). Similarly, Charlie Bean (deputy BoE governor, 2008-2014) stated soon after the referendum that he had ‘absolutely no doubt at all’ that euro-denominated IRD clearing would shift to EU27 jurisdictions (Pratley Citation2016).

Indeed, several post-referendum developments indicate that the relocation of various instruments is a distinct possibility. One such development is the considerable shift in repurchase agreements (repos). In 2018, London Clearing House (LCH) announced that it would increase provision of clearing in these instruments at its Paris-based subsidiary. LCH made this decision on the basis that EU27 firms could simultaneously ‘net’ their bond transactions with the ECB at the same location (Stafford Citation2017a). In this respect, the move is actually part of a larger LCH efficiency strategy initiated before the Brexit referendum, but nonetheless given further impetus by an impending UK exit (Jones Citation2018b).

Other limited business transfers have occurred both on the provider and client side, often as a result of explicit poaching tactics. Eurex—the clearing platform owned by Deutsche Börse—has been particularly aggressive in this regard. In 2017, it recruited over twenty investment banks onto their new profit-sharing incentive scheme as a means to boost trading volumes (Stafford Citation2017b). Similarly, in 2019, Dekabank—a key intermediary for German savings banks—took a significant share of their derivatives booking business to the Eurex platform in order to avail of a 100% fee discount for relocating customers (Vaghela Citation2019).

Despite these developments, however, official data by the BIS provides a powerful counter to the notion that Brexit might loosen London’s grip on key trading markets. By good fortune, the BIS Central Bank Survey tracks dealing and clearing in FX and OTC derivatives markets on a triennial basis, with the most recent reports released in 2016 and 2019. As such, these surveys are perfectly placed to capture post-referendum market shifts.

Beginning with the prized OTC IRD market (), in April 2019, the UK recorded an average daily turnover in IRD’s of $3.7 trillion, representing an 11% increase from three years earlier. As such, approximately half of the world IRD’s are now handled in the UK. Crucially, this increased capture of global trading holds specifically in relation to euro-denominated contracts, as UK-based dealers registered a likewise 11% increase, taking their share of the euro-denominated IRD’s from 75% in 2016, to a whopping 86% in 2019. These results are devastating from the perspective of those that see Brexit as an opportunity to grow their domestic centres: for instance, France (the second largest EU27 trader) saw their already meagre level of IRD turnover fall from $141bn to just $120bn, or from 4.6% of total global IRD’s in 2016 to 1.6% in 2019. Moreover—and contrary to the alternative hypothesis that OTC business may relocate from London to non-European centres such as New York—the UK also increased its share of dollar-denominated IRD contracts by an extraordinary 19%.

Table 3. Total IRD’s and euro-denominated IRD’s in UK, France, and Germany: 2016 and 2019 (Daily averages, in millions of US dollars)

A similar story emerges in relation to the FX market (). In this segment, the UK consolidated its position as the number one trading location, increasing its share of the global market by 6% and becoming responsible for 43.1% ($3,576bn) of total FX activity. This compared with a decrease in both French (2.8% to 2%) and German (1.8% to 1.5%) FX activity. Once again, in the most relevant sub-category of euro-related transactions, the UK increased its share of these trades by 4.5%, now handling 47.8% of all global euro FX dealings. Meanwhile, France and Germany registered increases of 1.3% and 0.1% respectively, bringing their combined share of total euro FX transactions to just 8.3% (5% in France; 3.3% in Germany).

Table 4. FX total, FX euros, FX dollar swaps: 2016 and 2019 (Daily averages, in millions of US dollars)

Also instructive is the FX market for US dollars, specifically as it relates to FX swaps. Given the specific importance of these derivatives for major corporations’ liquidity and risk management (Lysandrou et al. Citation2017: 170-171), it might be expected that some of this business will migrate to the continent in anticipation of EU27 firms losing unfettered access to the City. Again, however, the BIS data shows London tightening its grip, capturing approximately 2.1% more of this rapidly growing market, while France and Germany decreased their share by 2.8% and 0.6% respectively. Overall, London’s extensive dealer-clearing networks presently manage 39.2% of the global FX swaps market, compared to only 1.8% in Germany and 1.3% in France.

Also notable is London’s growing dominance in FX transactions of emerging market currencies over the past five years. This is significant because, if the City continues to loosen commercial relations with the EU over time, it is clear that rapidly developing financial markets within these economies (particularly across Asia) offer the best chance for the City to maintain its global position.

Unsurprisingly, it is China that leads the pack in terms of growth opportunities, especially given the explosion in offshore Renminbi (RMB) trading in recent years, and in which the City is soaring ahead of EU27 competitors. From 2016-2018, London more than doubled its 2016 volume of RMB transactions, controlling a full 36% of the market, compared to just 6% by its closest EU27 rival, Paris. In 2019, this figure grew to 43.9% (Szalay Citation2019a, Citation2019b). By contrast, hubs like Frankfurt have hardly made any progress in this market, while even in New York daily trading volumes are four times less than those in the City. A similar story is playing out with regards to the currencies of India, Russia, Brazil, and South Korea—all of which the City has grabbed a greater share of compared to its rivals over the four year period from October 2016 to October 2020 (Gokoluck and Quinn Citation2021).

One final development that should be mentioned—and one that runs contrary to these trends—is the recent relocation of share-trading, which occurred soon after the UK’s full exit from the EU on January 1st 2021. In the absence of an equivalence deal on equity markets, approximately €6.5bn worth of trading in EU shares moved from London to Amsterdam, making the continental hub the largest trader in that market (Stafford Citation2021a). Although the shift was widely expected and prepared for by traders, the rapid movement of business provides an indicative warning of how relocations can suddenly threaten the long-standing dominance of incumbents in specific financial markets.

Nevertheless, several caveats must also be recognised. First, share-trading is a relatively low-margin business, the loss of which is minimal compared to relinquishing, for instance, control over much larger OTC clearing and FX markets. More importantly, however, the shift constitutes no loss for the City in terms of employment. This is because, while the new trades are formally booked through equities exchanges within Amsterdam, the traders making those transactions are still based in London, with no need for staff to relocate to the EU27 bloc. As pointed out by financial markets specialist Gerard Lyons, ‘the value in the trade for an economy remains in London’ with ‘activities such as settlement, clearing, and risk management’ still being carried out by UK-based employees (Lyons Citation2021). Moreover, given that share trading taxes are not paid on individual trades, but rather, the overall revenues reported by trading venues, the loss is not expected to impact the tax receipts generated by UK financial services (Stafford et al. Citation2021).

Finally, despite the loss of EU shares, the UK actually regained its spot as the single largest share trading centre in Europe just a few month later in July 2021. This is down in part to the relocation of Swiss shares into the UK market as a result of a bilateral financial services deal, but more importantly, a huge increase in capital raisings by the London Stock Exchange during the first half of the year, and driven by London’s abiding attraction of internet-based technology firms (Stafford Citation2021b).

Overall, then, it is clear from the data that conventional expectations regarding the UK’s position in key infrastructure markets have, thus far, proven to be incorrect. Against all expectations, the City has actually strengthened its dominance over some of the most vital services—in particular, the clearing of OTC derivatives, as well as FX transactions in dollars, euros, and a range of key emerging market currencies. Such developments have rendered financial end users, and indeed, end users of euro-denominated products, more dependent than ever on continued access to London. Two exceptions to this are repos and share trading, a significant amount of which have migrated to EU27 jurisdictions due to efficiency benefits and regulatory requirements. Nevertheless, the substantive value of EU share trading activities are still carried out by City-based firms and their employees.

Theorising resilience

Taken as a whole, the evidence on relocation shows that, in the five years since the 2016 referendum, the City of London has largely maintained—and in key instances advanced—its competitive lead over EU27 hubs. This is a confounding result for the majority of commentary that anticipated Brexit causing irreparable harm to the UK’s most prized economic sector. How then, should this broad-based resilience of the City to date be interpreted and understood?

While space constraints prevent a comprehensive assessment of that question, this section highlights two analytical frames that potentially speak to London’s ability to withstand a major financial disruption and provides a theoretical foundation for future research.

One framework that appears especially relevant revolves around the concept of a ‘big-city agglomerative peak’, recently advanced by Iversen and Soskice (Citation2019, p. 188). The core claim is that the ICT-revolution has ushered in a period of growth whereby the specialised knowledge competencies and resources of leading economic sectors are geographically embedded within a small number of major cities throughout the world. This contention emphasises the stubborn ‘immobility’ of critical knowledge-based clusters within the modern economy and challenges the common belief that capital can easily move (or ‘relocate’) throughout the globe, as firms must retain close ties with these key production nodes.

London’s financial ecosystem stands out as a prototypical example of such a peak. As is well documented, the highly concentrated spatial interaction of complementary financial firms and workers within London produces (and re-produces) positive spillover and network effects (See Cook et al. Citation2007; also Lysandrou et al. Citation2017). Firms and their employees across discrete financial sub-sectors create enduring relations of commercial trust and dependency, knowledge diffusion, and the capacity to dramatically compress costs compared to rival locations; closely related sectors such as law, accountancy, consultancy, technology, among others, blossom around these clusters due to market incentives, skill overlaps, and the need for specialist suppliers; higher-education institutions develop programs to produce the graduates and training required for future advancement; successful clustering fosters the creation of trailblazing new technologies and advanced infrastructure.

Several aspects of the data discussed above align with this perspective. A key example is the market for OTC derivatives clearing—a primary target of relocation claims, yet, an area in which City-based CCPs have advanced their control. At the core of London’s prominence are so-called ‘margin pool’ (or ‘netting’) benefits derived from UK CCP’s handling of multicurrency trades across diverse instruments, which allows them to significantly compress collateral requirements by offsetting different payment positions among customers. By contrast, French and German CCP’s are far too small in scale to engage similar portfolio efficiencies, and thus, any relocation of these trades would push up the costs of risk management for firms (both financial and non-financial) substantially (European Parliament Citation2017, pp. 46–48). According to a widely circulated report by Clarus Technology, the movement of LCH’s share of clearing business alone to Eurozone-based CCPs would result in a doubling of the initial margin requirement for traders, from $83bn to $161bn (Government Actuary's Department Citation2017). In this context, it is little surprise that the EU has consistently been forced to make exceptions and provide for the continuation of cross-border clearing between the City and EU27-based firms (European Securities and Markets Authority Citation2020).

London’s advantages flow from more than sheer liquidity concentration, however. Also relevant is the fact that traders rely heavily on the protections provided exclusively by English law and which facilitate multiple steps in the chain of these complex transactions (Scarpetta and Booth Citation2016, p. 53). Similarly, the dealer-networks (centred mainly among UK and US investment banks) available within the City make London uniquely equipped to provide highly customised OTC derivatives. This is a major draw for the largest institutional investors that require products tailored to their specific risk profile, concealed from public disclosure, and the capacity to handle enormous counterparty exposures (Lysandrou et al. Citation2017, p. 171–172). Thus, it is not only London’s substantial liquidity advantages, but also the existence of a supportive infrastructure and long-cultivated knowledge networks, that make it such a challenging ecosystem for alternative hubs to replicate, and for market actors to replace.

The agglomeration thesis also finds support from a senior analyst of the BIS derivatives survey (Philip Wooldridge) discussed above, who argues that the significant ‘geographical concentration’ of the OTC clearing market over recent years is a direct result of the positive ‘network externalities’ offered by London-based CCPs, especially in cost-cutting, but also the technical and legal knowledge required to process these trades (Woolridge Citation2019, p. 16).

Another key example of agglomeration relates to the UK’s continued outstripping of EU27 rivals in the area of FinTech development and investment. Crucial here is London’s fortunate interaction of a world-leading financial and digital sector, which creates a unique opportunity for cross-sectoral partnerships, employee/skill migration, and innovation. Indeed, this potent fusion of industries was the driving motivation behind the UK government’s 2010 ‘Tech City’ scheme, aimed at making London a leading global centre for knowledge-based start-ups. The initiative succeeded by incentivising those who had lost their jobs in finance as a result of the 2008 crash to migrate into projects that leverage technology in the delivery of financial services. The result is a dense clustering of creative-digital-finance firms based at the so-called ‘Silicon Roundabout’ vicinity in East London—a location that now reigns as Europe’s premiere FinTech hub, and ranked second in the world behind only San Francisco (Irrera Citation2021).

The core implication of all this with regards to resilience is that financial firms are not ‘footloose’ in the sense that they can easily turn their back on the City’s unique ecosystem (Iversen and Soskice Citation2019, p. 159). Exiting prematurely would not only diminish their capacity to leverage these benefits, but also put them at an immediate disadvantage vis-à-vis their competitors. Furthermore, even the most determined drive by rival centres to replicate the City’s co-location clustering and knowledge agglomeration—a task severely impeded by the limits of EU27 financial integration—would take many years, perhaps decades, to bear fruit. Hence, it should not come as a surprise that firms are hesitant to relocate, adopting instead a ‘wait-and-see’ approach before making any rash decisions. As observed in the data, even those companies deciding to expand operations across EU27 hubs have been sure to maintain the bulk of their business within London.

In short, London’s unrivalled ‘agglomeration peak’ gives the UK government a crucial first mover advantage, and with that, a substantial degree of autonomy in financial policymaking. This perspective of business dependence on London’s ecosystem runs in direct opposition to the conventional political economy understanding of finance as a thoroughly mobile form of investment, liberated from spatial commitments, and capable of kowtowing policymakers through the threat of exit.

A second explanatory framework—by no means in conflict with the agglomeration outlook—conceives of the City as one half of a broader ‘Anglo-American’ dominance in global finance. As evidenced by the overwhelming presence of Wall Street institutions, London is deeply entwined with the world’s other leading financial centre, New York, and as such, its competitive position is substantially related to the ongoing primacy of the US in international affairs (Wójcik Citation2013, Fichtner Citation2017). This ‘joint dominance’ of ‘NY-LON’ is consolidated by a close regulatory and legal alignment among supervisors, and is, in turn, promoted as a best-practise benchmark for the industry as a whole through supranational regulatory fora (Helleiner and Pagliari Citation2010).

One clear example of how this partnership bolsters the position of London can be demonstrated through its continuing supremacy in FX dollar trading, discussed previously. As the world’s reserve currency, the dollar is an indispensable resource for global trading, commercial funding, and the management of states’ economic stability. Yet, a full 44% of the total global US dollar market share is situated with the UK. By facilitating one of the largest markets for dollars and dollar-denominated assets in the world, then, the City effectively functions as a crucial foreign offshoot of US hegemony, and benefits considerably from EU corporations’ (and state agencies’) pressing need to engage with dollar trading. The importance of this market to London is underscored by a recent BoE report on FX transactions which reveals that a full 90% of UK-based FX trades involve the dollar, while trading of the dollar-euro currency pair in particular accounts for 28% of overall turnover (BoE Citation2019).

Moreover, as the data reveals, Brexit did not diminish the UK presence of the ‘big five’ US investment banks who are, by now, responsible for more than half of European capital market provision, the majority of which is routed through their headquarters in London (Goodhart and Schoenmaker Citation2016, Clarke Citation2020). In fact, it is these US investment firms who are most responsible for the relative absence of capital flight post-Brexit: first, by significantly scaling back their EU27 relocation plans that were indicated directly after the referendum; second, by making strong future commitments with regards to their London headquarters; and third, by engaging aggressively with market workarounds to ensure their majority of staff and operations remain based in the City (Arnold Citation2017). Indeed, the same can be said of another set of prominent capital market actors—namely, the ‘big three’ US Credit Rating Agencies (Fitch, Moody’s, and Standard & Poor’s). These firms now rely upon an obscure ‘endorsement’ mechanism as a means to ensure continuing recognition of their ratings across the EU27 jurisdiction, despite keeping their staff and decision-making processes located within London (Binham Citation2018, European Securities and Markets Authority Citation2019).

Finally, the UK’s continued ability to attract a higher proportion of FDI and FinTech capital funding compared to EU27 hubs is primarily a result of US-derived financial flows. For example, in maintaining the top spot for finance-related FDI investment across Europe in EY’s 2020 survey, a full third of that FDI came from the US (Luttig Citation2020). Meanwhile, North American investors are responsible for the majority of UK FinTech venture capital on a consistent annual basis, with more than 60% coming from funding rounds involving at least one US investor in 2020 (Carrick Citation2020). This prominence of US investment is not only a function of the UK’s intrinsic competitiveness with regards to financial services, but also due to the cultural familiarity of North American investors with UK markets and their abiding confidence in the Anglo-American based legal structure.

In short, while Brexit represents a significant exogenous shock to London’s EU-centred exporting potential, it has done little to undermine its core connections to its North American counterpart: e.g. City-based headquarters, the disproportionate flow of capital, the primacy of London-based FX dealers, and the close legal and regulatory alignment between US-UK jurisdictions. Unless the Brexit fallout begins to corrode these and other Anglo-American entanglements, it is difficult to see the City being displaced as a global financial centre of gravity.

Of course, this is not to say that such an outcome is impossible, especially over a longer timeframe. In fact, it could be argued that the future actions of large US investment banks will play a key role in London’s fate, given that they feature prominently at the intersection of agglomeration dynamics and the enduring NY-LON relationship. And though it is unlikely that any single EU27 hub can take over London’s role, the same cannot be said about New York, which is well placed to draw EU27 financial business away from its outsized dependence on the City. For instance, several months after the UK’s full exit, New York picked up a substantial portion of derivative transactions from EU firms—approximately £2.3 trillion notional value in monthly trades that could not be served by UK-based platforms due to regulatory constraints (Jones Citation2021). However, as New York maintains multiple equivalence agreements with the EU—agreements still to be negotiated by UK-EU officials—this allowed Manhattan-based venues to pick up more of this business than any single EU27 rival.

If these and similar kinds of transactions started to gradually shift across the Atlantic, that might encourage large City-based US investments firms to rethink their presence in London, rather than consolidation within their home state—especially since most of their UK business is based upon the servicing of EU firms and investors. This, in turn, could instigate a negative feedback loop for London, whereby the loss of access to EU markets eventually begins to chip away at both of the key competitive advantages identified here: ecosystem agglomeration effects and longstanding financial ties with the US. Such a scenario is highly speculative, however, and, as evidenced by the empirical data on market trends since 2016, does not correspond with the robust performance of UK financial services to date.

Conclusion

The broad-based resilience of UK financial services over the last five years poses an important challenge to political economy scholarship. In particular, it indicates the need to re-evaluate some core assumptions regarding the process of relocation and to sharpen our understanding of the competitive motivations that underlie potential transfers.

At present, the relocation thesis rests upon a much too simplistic and undifferentiated notion of capital flight and firm/investor behaviour. Undoubtedly, Brexit has forced firms to deliberate over costly commercial preparations under highly uncertain circumstances. However, not all financial actors face the same jurisdictional barriers and/or organisational reconfigurations, resulting in divergent perspectives on the need for relocation. Rather than leveraging the vague assumption that firms will simply relocate in order to retain existing EU27 business, then, analysts should seek to provide a more fine-grained analysis of the costs, benefits, and alternative strategies being weighed by actors within discrete areas of finance. This would advance a more investor-centred perspective on post-Brexit decisions and yield a more variegated picture of how firms interpret their options.

Moreover, and as suggested by the big-city agglomerative peak perspective, researchers need to develop a deeper understanding of the various factors that make the City endure as an indispensable hub for global financial transactions. Key topics in this strain of research would include the benefits that derive from the system of English law and the commercial protection this offers investors compared to alternative financial centres. Another candidate is London’s highly advanced (physical) technological infrastructure—a competitive edge that is consistently overlooked within the literature. For example, the transatlantic submarine cables that transmit FX data from US markets to the City in milliseconds, as well as numerous state-of-the-art data centres dotted around London that give investors direct access to key price matching engines and data providers (Stafford Citation2017c). These technologies substantially power the City’s overwhelming dominance in trading markets which are perhaps the most striking illustration of London’s post-referendum vitality. A specific focus might also be trained on the City’s uniquely enabling FinTech environment that continues to outflank continental rivals in terms of investment attraction and innovation. These and other distinctive ecosystem advantages appear to reside at the heart of London’s relative sheltering from the typical pressures of capital flight.

Lastly, researchers should give more attention to the EU’s disproportionate level of dependence on UK financial services. At present, the focus is almost exclusively on the threat of Brexit to the City, while little analytical space is given to the potential dangers posed to EU corporates (both financial and non-financial) from losing access to UK wholesale services and the strategies they are deploying (e.g. market workarounds, alternative providers, relocation to London, etc.) to mitigate those threats. At the supranational level, scholars should consider the impact of empirical relocation trends on the strategic positioning of EU officials regarding the future involvement of the City in EU financial markets. Politics notwithstanding, the ongoing success or failure of ‘poaching’ efforts by EU27 hubs is likely to have a strong shaping effect on the future direction of EU policymaking within financial services—be it in terms of more immediate equivalence negotiations with the UK or in terms of more long-term integration efforts such as the creation of a fully-functioning capital markets union.

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to acknowledge helpful comments from Tobias Arbogast, Lucio Baccaro, Puneet Bhasin, Benjamin Braun, Fabio Bulfone, Jan Fichtner, Arjen van der Heide, Kathleen Lynch, Waltraud Schelkle, and Sidney Rothstein.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Manolis Kalaitzake

Manolis Kalaitzake ([email protected]) is Lecturer in Political Economy at the University of Edinburgh, Politics & International Relations subject area. His research focuses on finance, state-business relations, and European political economy. His research has been published in outlets such as Review of International Political Economy, Politics & Society, New Political Economy, Competition & Change, and Business & Politics.

Notes

1 I follow convention by using the term ‘City of London’ to refer the UK financial sector more broadly.

2 Equivalence offers third-country financial institutions access to EU27 countries if the regulatory standards in its home country are found to be in close alignment/compliance with the EU’s regulatory framework.

3 The majority of data analysed relates specifically to the time period of June 2016 to May 2020. However, upon reviewing the paper, I have added several pieces of data up to the present (July, 2021) due to their central importance to the topics discussed (e.g. the FT employment survey in December 2020) or to bring the reader up to date with crucial developments after the Brexit ‘transition period’ ended on January 2021 (e.g. the relocation of EU share trading). As such, the study effectively covers a little over five years since the Leave referendum.

4 The lower figure assumes a loss of passporting rights after an UK-EU agreement, while the higher figure envisages a return to WTO-terms in the event of a no-deal Brexit.

5 This would involve not only full equivalence approval across all Single Market directives, but also agreement on entirely new access arrangements where equivalence provisions are not currently available.

6 Delegation is a practise whereby funds officially domiciled within EU27 countries ‘delegate’ their business to portfolio managers based in the UK in order to access the City’s huge pools of liquidity and lower trading costs. Approximately 90% of assets under management within the EU utilise the delegation model, the majority of which diverts trading back to London (Mooney & Thompson, Citation2017).

7 Under a more damaging scenario in which no equivalence is given and other restrictions arise, job loss estimates rise to 70,000.

8 The world largest asset manager BlackRock—which employs approximately 3000 staff in the UK—declined to reveal staffing changes to the FT survey. Notably, however, in 2018, the firm announced that London would remain its EMEA headquarters, ending speculation that it was poised to relocate business to the EU27 bloc (Ricketts Citation2018).

9 As per note 6, these firms are able to secure post-Brexit access to London through the mechanism of portfolio delegation, hence requiring a base in EU27 locations for back office activities (Riding Citation2019).

10 For an updated (22nd February, 2021) list of firms broken down by firm type and a firm’s home state, see https://www.bovill.com/london-remains-financial-service-centre-of-europe-final-numbers-show/

11 Unicorn data available at: https://www.cbinsights.com/research-unicorn-companies

References

- Armour, J., 2017. Brexit and financial services. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 33 (suppl_1), S54–S69. doi:10.1093/oxrep/grx014.

- Arnold, M. 2017. Banks study loopholes to enable UK branches to sell to EU clients. Financial Times. February 2.

- Bank for International Settlements. 2016a. OTC interest rate derivatives turnover in April 2016. Triennial Central Bank Survey. Available at https://www.bis.org/.

- Bank for International Settlements. 2016b. Global foreign exchange market turnover in April 2016. Triennial Central Bank Survey. Available at https://www.bis.org/.

- Bank for International Settlements. 2019a. OTC interest rate derivatives turnover in April 2019. Triennial Central Bank Survey. Available at https://www.bis.org/.

- Bank for International Settlements. 2019b. Global foreign exchange market turnover in April 2019. Triennial Central Bank Survey. Available at https://www.bis.org/.

- Bank of England. 2019. The foreign exchange and over-the-counter interest rate derivatives market in the United Kingdom. Quarterly Bulletin, Q4, December 20. Available at: https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/.

- Batsaikhan, U., Kalcik, R., and Schoenmaker, D. 2017. Brexit and the European financial system: mapping markets, players and jobs. Bruegel. Available at https://www.bruegel.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/PC-04-2017-finance-090217-final.pdf.

- BBC. 2018. Lord Mayor says Brexit hit to City less than feared. BBC. August 1.

- Binham, C., and Jones, C. 2018. Bank watchdog rules out ‘back-to-back’ trading ban after Brexit. Financial Times. September 18.

- Blackman, A. 2018. Sumitomo Mitsui to Lease New European Headquarters in London. Bloomberg. February 13.

- Bovill. 2020. London set to remain financial services capital of Europe as over 1000 EU firms plan to open UK offices. Bovill Insights. Available at https://www.bovill.com/london-set-to-remain-financial-services-capital-of-europe-as-over-1000-eu-firms-plan-to-open-uk-offices/.

- Brush, S. 2019. Brexit has cost London just 1,000 investment bank jobs. Bloomberg. September 19.

- Burke, T. 2018. Wells Fargo completes purchase of London HQ. Financial News. January 3.

- Carrick, A. 2020. London fintechs secure billions from US investors despite virus and Brexit uncertainty. City A.M. October 16. Available at: https://www.cityam.com/london-fintechs-secure-billions-from-us-investors-despite-virus-and-brexit-uncertainty/.

- Cassis, Y., and Wójcik, D., 2018. International financial centres after the global financial crisis and brexit. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- City of London Corporation. 2019. The total tax contribution of UK financial services in 2019. 12th edition.

- Clarke, P. 2020. Wall Street banks just edged out Europeans in their one post-Lehman holdout. Financial News. June 16.

- Cook, G., et al., 2007. The role of location in knowledge creation and diffusion: evidence of centripetal and centrifugal forces in the City of London financial services agglomeration. Environment and Planning A, 39 (6), 1325–45.

- Ernst & Young. 2019a. UK Attractiveness Survey 2019. Available at https://www.ey.com/.

- Ernst & Young. 2019b. Europe Attractiveness Survey 2019. Available at https://www.ey.com/.

- Ernst & Young. 2019c. UK FinTech Census 2019: A snapshot: two years on. Available at https://www.ey.com/.

- Ernst & Young. 2020a. UK Attractiveness Survey 2020. Available at https://www.ey.com/.

- Ernst & Young. 2020b. Europe Attractiveness Survey 2020. Available at https://www.ey.com/.

- European Banking Authority. 2018. Press Release ‘EBA publishes Opinion to hasten the preparations of financial institutions for Brexit’. Available at: https://www.eba.europa.eu/.

- European Central Bank. 2017. The international role of the euro. Available at http://www.ecb.europa.eu.

- European Parliament. 2017. Implications of Brexit on EU Financial Services. Study for the Committee on Economic and Monetary Affairs. Available at https://www.europarl.europa.eu/portal/en.

- European Securities and Markets Authority. 2019. Public statement: Endorsement of credit ratings elaborated in the United Kingdom in the event of a no-deal Brexit. March 15. Available at: https://www.esma.europa.eu.

- European Securities and Markets Authority. 2020. Press Release ‘ESMA to recognise three UK CCPS from 1 January 2021’. Available at: https://www.esma.europa.eu/.

- Evans, J. 2017. Deutsche Bank signs lease for new London headquarters. Financial Times. August 1.

- Fichtner, J., 2017. Perpetual decline or persistent dominance? uncovering anglo-america’s true structural power in global finance. Review of International Studies, 43 (1), 3–28.

- Finch, G., Warren, H., and Hadfield, W. 2019. The great Brexit banker exodus that wasn’t. Bloomberg. January 31.

- Flood, C. 2017. Asset managers fear UK will suffer Brexit jobs exodus. Financial Times. October 22.

- Gokoluck, S., and Quinn, A. 2021. London looks past Brexit to eclipse rivals in emerging markets. Bloomberg. June 23.

- Goodhart, C., and Schoenmaker, D. 2016. The United States Dominates Global Investment Banking: Does It Matter for Europe? Bruegel Policy Contribution 2016/06. Available at: https://www.bruegel.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/pc_2016_06-1.pdf.

- Government Actuary's Department. 2017. Monthly Bulletin from the Insurance & Investment Team. July. Available at https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/629670/Jun_2017_update.pdf.

- Hay, C., and Bailey, D., 2019. Diverging capitalisms. Cham: Springer.

- Helleiner, E., and Pagliari, S., 2010. ‘The End of self-regulation? hedge funds and derivatives in global financial governance’. In: E. Helleiner, S. Pagliari, and H Zimmermann, eds. Global finance in crisis: The Politics of International regulatory change. London: Routledge, 123–52.

- Howarth, D., and Quaglia, L., 2018. Brexit and the battle for financial services. Journal of European Public Policy, 25 (8), 1118–1136.

- Irrera, A. 2021. London fintech funding soars in first half of the year. Reuters. July 8.

- Iversen, T., and Soskice, D., 2019. Democracy and prosperity: reinventing Capitalism through a turbulent century. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- James, S., and Quaglia, L., 2018. The Brexit negotiations and financial services: A Two-level game analysis. The Political Quarterly, 89 (4), 560–567.

- James, S., and Quaglia, L., 2019a. Brexit, the city and the contingent power of finance. New Political Economy, 24 (2), 258–271.

- Jenkins, P., and Morris, S. 2018. Paris set to triumph as Europe’s post-Brexit trading hub. Financial Times. September 30.

- Jones, H. 2018a. Bank of England downplays financial job moves ahead of Brexit. Reuters. July 25.

- Jones, H. 2018b. Paris unit of LCH to overtake London in some euro clearing after Brexit. Reuters. March 22.

- Jones, C. 2019. Banks move just 1,000 jobs despite Brexit exodus fears. The Times. September 20.

- Jones, H. 2021. New York wins Brexit swaps shake-up as clearing stays in London. Reuters. May 11.

- Kalaitzake, M., 2021. Brexit for finance? Structural interdependence as a source of financial political power within UK-EU withdrawal negotiations. Review of International Political Economy, 28 (3), 479–504. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2020.1734856.

- Landauro, I. 2018. French banks scale back plans for post-Brexit staff moves. Reuters. November 23.

- Lavery, S., McDaniel, S., and Schmid, D., 2019. Finance fragmented? Frankfurt and Paris as European financial centres after brexit. Journal of European Public Policy, 26 (10), 1502–1520.

- Luttig, V. 2020. Ernst & Young Press Release ‘UK retains top spot for Financial Services investment in Europe and is expected to outperform the Continent post COVID-19’, June 22. Available at: https://www.ey.com/en_uk/newsroom.

- Lyons, G. 2021. No, Amsterdam hasn’t overtaken the City of London. The Spectator. February 11.

- Lysandrou, P., Nesvetailova, A., and Palan, R., 2017. The best of both worlds: scale economies and discriminatory policies in London's global financial centre. Economy & Society, 46 (2), 159–184.

- McCafferty, I. 2018. Interviewed by Iain Dale on LBC radio. August 7. Available at https://www.lbc.co.uk/radio/presenters/iain-dale/brexit-exodus-eu-bankers-underway-bank-of-england/.

- Mooney, A., and Thompson, J. 2017. Europe’s national regulators clash over delegation. Financial Times. October 8.

- Morris, S., and Brunsden, J. 2019. How London banks are trying to dodge Brexit. Financial Times. April 10.

- Morris, S., and Pooler, M. 2020. JPMorgan Chase buys second Paris office as post-Brexit plan accelerates. Financial Times. January 20.

- Noonan, L., et al. 2020. Finance jobs stayed in London after Brexit vote. Financial Times. December 12.

- Oliver Wyman. 2016. The Impact of the UK's Exit from the EU on the UK-based Financial Services Sector. Available at https://www.oliverwyman.com/.

- Pesendorfer, D., 2020. Financial markets (Dis) integration in a post-Brexit EU: towards a more resilient financial system in Europe. Cham, Switzerland: Springer.

- Pratley, N. 2016. Stock exchange merger is now caught in the Brexit crossfire. The Guardian. September 12.

- PricewaterhouseCoopers. 2016. Leaving the EU: Implications for the UK financial services sector. Available at http://www.pwc.com/.

- PricewaterhouseCoopers. 2018. Impact of loss of mutual market access in financial services across the EU27 and UK. Available at http://www.pwc.com/.

- Ricketts, D. 2018. Blackrock to keep European HQ in London after brexit. Financial News. October 20.

- Riding, S. 2019. EU and UK regulators agree Brexit deal for asset managers. Financial Times. January 31.

- Ringe, W.G., 2018. The irrelevance of Brexit for the European financial market. European Business Organization Law Review, 19 (1), 1–34.

- Rosamond, B., 2019. Brexit and the politics of UK growth models. New Political Economy, 24 (3), 408–421.

- Scarpetta, V., and Booth, S. 2016. How the UK’s financial services sector can continue thriving after Brexit. Available at: https://openeurope.org.uk.

- Schoenmaker, D. 2017. The UK financial sector and EU Integration after Brexit: The issue of passporting. Bruegel. Available at https://www.bruegel.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/Brexit-passport-final-2017.pdf.

- Sidders, J. 2018. Bank of America Signs Up for Another 10 Years at London HQ. Bloomberg. February 21.

- Spink, C. 2019. Citigroup splashes out on London HQ. Reuters. April 12.

- Stafford, P. 2016. Losing euro-denominated clearing would cost London 83,000 jobs. Financial Times. November 14.

- Stafford, P. 2017a. London clearing house shift heads off UK-EU regulatory battle. Financial Times. May 7.

- Stafford, P. 2017b. Deutsche Börse eyes City of London’s euro clearing crown. Financial Times. November 20.

- Stafford, P. 2017c. London’s trading infrastructure retains edge despite Brexit. Financial Times, March 22.

- Stafford, P. 2021a. Amsterdam ousts London as Europe’s top share trading hub. Financial Times. February 10.

- Stafford, P. 2021b. London reclaims top trading status from Amsterdam. Financial Times. July 2.

- Stafford, P., Hodgson, C., and Giles, C. 2021. London unlikely to regain lost EU sharing, warn City figures. Financial Times. January 6.

- Szalay, E. 2019a. How London won the race for the renminbi. Financial Times. February 8.

- Szalay, E. 2019b. London races farther ahead as renminbi trading hub. Financial Times. November 11.

- Talani, L.S., 2019. ‘Pragmatic adaptation’ and the future of the City of London: between globalisation and brexit. In: C. Hay, and D Bailey, eds. Diverging capitalisms. Cham: Springer, 43–71.

- Tech Nation. 2019. The UK has become the world’s hottest tech hub in 2019. Available at https://blog.dealroom.co/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/Capital-flows-UK-vFINAL.pdf.

- Tech Nation. 2020. 2019: A record year for VC investment in the UK. Available at https://blog.dealroom.co/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/2019-A-record-year-for-VC-investment-in-the-UK.pdf.

- Thompson, H., 2017. How the City of London lost at brexit: A historical perspective. Economy and Society, 46 (2), 211–228.

- Toporowski, J., 2017. Brexit and the discreet charm of haute finance. In: D. Bailey, and L Budd, eds. The political economy of brexit. Newcastle: Agenda Publishing, 35–44.