ABSTRACT

The aim of this paper is to contribute to advancing the academic debate on dependent financialisation through a focus on East-Central Europe. In doing so, the paper identifies the role of Europeanisation as a driver of dependent financialisation using the Baltic States of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania as case studies.

The paper makes two main contributions to the literature on dependent financialisation. First, it argues that, through the establishment of ‘financial chains’, dependent financialisation creates asymmetric co-dependencies and bilateral risks between the ‘dependent’ economies in the (semi-)periphery and the financial actors in core countries. While the (semi-)peripheral economies become dependent on capital flows from the core countries, the profits of financial actors in the core become increasingly dependent on their operations in the (semi-)periphery. In turn, the growing instability created by the process of dependent financialisation in the (semi-)periphery creates a source of risk for financial actors in core countries, which can spread to the rest of the economy. Second, the paper suggests that dependent financialisation is a dynamic phenomenon that displays strong pro-cyclical features. Thus, the cycles of expansion and retreat of dependent financialisation in (semi-)peripheral countries are linked to their economic performance, as well as to the conditions in international financial markets.

Introduction

The aim of this paper is to contribute to advancing the academic debate on dependent financialisation through a focus on East-Central Europe (ECE). In recent years, research has shown that financialisation in peripheral and semi-peripheral contexts is dependent on that of developed economies (Becker et al. Citation2010, Becker and Jager Citation2012, Gabor Citation2013, Lapavitsas and Powell Citation2013, Bortz and Kaltebrunner Citation2017, Kaltenbrunner and Painceira Citation2018, Fernandez and Aalbers Citation2020, Socoloff Citation2020). However, despite the growing interest in this phenomenon, to date, many aspects remain unaddressed, in particular, in relation to the durability and evolution of the linkages of dependent financialisation and the bilateral exposure to risk, both in the ‘dependent’ and the ‘dominant’ economies.

Therefore, this article analyses the rise, characteristics and cycles of dependent financialisation in East-Central Europe, using the Baltic states of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania as case studies.Footnote1 These countries are considered the most paradigmatic examples of dependent financialisation in ECE. They are small and very open economies with the highest rates of foreign penetration in the banking sector worldwide, thus, they are extremely sensitive to external financial factors (Epstein Citation2013, Citation2017, Spendzharova and Bayram Citation2016, Pataccini et al. Citation2019). After regaining independence from the USSR in 1991, the three countries began a determined process of convergence with the European Union (EU). In this framework, since early 2000 the Baltic countries have experienced the most marked boom–bust cycle in ECE, driven by capital inflows and (foreign) bank credit (Bohle and Greskovits Citation2012). Likewise, during the Global Financial Crisis (GFC), they were the most affected economies in ECE (and some of the most affected economies in the world), due to their high level of dependence on liquidity conditions in international financial markets, which also affected their recovery in the post-crisis years (Bohle Citation2018a). Therefore, these countries represent excellent examples to understand the dynamics and features of dependent financialisation in ECE.

At the theoretical level, the paper aims to explore the way in which the concept of ‘financial chains’ (Sokol Citation2017a, Citation2017b) can be mobilised to understand the patterns and dynamics of dependent financialisation in the Baltic Sea region and beyond. Financial chains are defined as ‘channels of value transfer (between people and places) and social relations that shape socio-economic processes and attendant economic geographies’ (Sokol Citation2017a, p. 679). In brief, the financial chains approach contends that in financialised economies, economic and social actors are interconnected through a myriad of linkages that operate as stable circuits of value transfer between actors across time and space, shaping the (re)production of social and geographic inequalities, while creating conditions for crises (Sokol Citation2017a, Citation2017b). Thus, it is argued that the financial chains approach can shed light on the complex web of flows of value and power relations characteristic of dependent financialisation.

This paper makes two main contributions to the literature on dependent financialisation. First, within the scholarship of critical political economy, the phenomenon of dependency is mostly approached as a one-way street. However, this paper argues that dependent financialisation creates asymmetric co-dependencies and bilateral risks between the ‘dependent’ economies in the (semi-)periphery and the financial actors in core countries. While the (semi-)peripheral economies become dependent on capital flows from the core countries, the profits of financial actors in the core become increasingly dependent on their operations in the (semi-)periphery. In turn, the growing instability created by the process of dependent financialisation in the (semi-)periphery creates a source of risk for financial actors in core countries, which can spread to the rest of the economy. Second, the paper suggests that dependent financialisation is a dynamic phenomenon that displays strong pro-cyclical features. Thus, the cycles of expansion and retreat of dependent financialisation in (semi-)peripheral countries are linked to their economic performance, as well as to the conditions in international financial markets.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows: Section 2 discusses the theoretical aspects of dependent financialisation; Section 3 analyses the rise of dependent financialisation in the Baltic States driven by the role of Europeanisation and applies the concept of financial chains; Section 4 discusses the changing dynamics in cross-border banking after the GFC; finally, section 5 presents the main conclusions.

Dependent financialisation

Over the last decades, the rise of financialisation has been widely documented and interpreted from a variety of perspectives (see van der Zwan Citation2014, Mader et al. Citation2020). More recently, especially after the GFC, the scholarship on financialisation has delved into the ‘varied’ or ‘variegated’ nature of this phenomenon (e.g. Lapavitsas and Powell Citation2013, Brown et al. Citation2015, Citation2017, Aalbers Citation2017, Ward et al. Citation2019, Fernadez and Aalbers, Citation2020). In particular, it has been shown that financialisation in peripheral and semi-peripheral contexts not only differs but is also derived from that of developed economies (Bonizzi Citation2013, Karwowski and Stockhammer Citation2017, Bonizzi et al. Citation2020, Karwowski Citation2020). In this way, financialisation in the (semi-)periphery is dependent on (and subordinated to) that of the core (Becker et al. Citation2010, Becker and Jager Citation2012, Rodrigues et al. Citation2016, Kaltenbrunner and Painceira Citation2018, Santos et al. Citation2018, Choi Citation2020, Lapavitsas and Soydan Citation2020, Alami et al. Citation2021, Bonizzi et al Citation2021).

Regarding the specific drivers and features of dependent financialisation, Becker et al. (Citation2010) point out that financialisation in the periphery has been dependent on ‘over-liquidity’ in the centre, while domestic financial groups pushed for reforms favouring this process. In this account, high interest rates in peripheral economies attracted (short-term) financial capital, leading to overvalued real exchange rates and providing incentives to the residents in these countries to become (highly) indebted in foreign currency, which in turn, promoted financial instability. Similarly, Lapavitsas and Powell (Citation2013) argue that financialisation in developing countries has been driven by the opening of capital accounts, the import of foreign capital, the accumulation of foreign exchange reserves and the increasing establishment of foreign banks.

Some authors have pointed out the role of asymmetric integration into international financial markets as a key driver of dependent financialisation (Correa et al. Citation2012, Girón and Solorza Citation2015, Kaltenbrunner and Painceira Citation2018), while recent contributions contend that the subordinated position of peripheral and semi-peripheral economies in the international monetary system moulds the features of financialisation in these countries (Bortz and Kaltebrunner Citation2017, Kaltenbrunner and Painceira Citation2018, Fernandez and Aalbers Citation2020, Socoloff Citation2020). The latter strand of research stresses that the lower position of the (semi-)peripheral economies in the international monetary hierarchy makes them dependent on the liquidity conditions of the central countries, because they can only borrow and accumulate reserves in foreign currency, generating currency mismatches.

Within the broad literature on dependent financialisation, some authors have focused on its peculiarities in East-Central Europe. Becker and Jager (Citation2012) stated that the mechanisms of EU integration have led to peculiar features of financialisation in the European peripheries. In turn, a growing body of research shows that foreign-owned banks and non-resident investors have played a key role in the rise of financialisation in the former centrally planned economies, favouring large capital inflows which fuelled massive household debt, current account deficits and real estate bubbles (Raviv Citation2008, Gabor Citation2010a, Sokol Citation2013, Sokol Citation2017a, Bohle Citation2018a, Citation2018b, Büdenbender and Aalbers Citation2019, Pataccini CitationForthcoming, see also Pataccini Citation2020). Finally, building on the concept of Dependent Market Economies introduced by Nölke and Vliegenthart (Citation2009) (see also Schedelik et al. Citation2020), Gabor (Citation2013) uses the term ‘dependent financialisation’ to refer to the case of Romania, where transnational financial actors channelled capital and liquidity to create new modes of profit generation.

Thereby, in broad terms, dependent (or subordinate) financialisation is defined as a process led by external drivers that establish an asymmetric relationship in which peripheral and semi-peripheral economies are dependent on capital flows, financial conditions and financial actors from core economies. Yet, these external factors interact with the local configurations, leading to specific country trajectories. In this framework, the present paper intends to address two main gaps in the academic literature. First, the paper highlights how the process of Europeanisation has driven and shaped dependent financialisation in the ECE before and after the GFC. While some papers have analysed the asymmetric effects of EU integration on the Eastern European periphery (e.g. Nolke and Vliegenhart Citation2009, Bohle and Greskovits Citation2012, Myant and Drahokoupil Citation2012, Stockhammer et al. Citation2016, Bohle Citation2018a) it is still not well understood how the linkages of dependent financialisation evolved in this region after the GFC, particularly in relation to the role of the banking sector. For instance, Epstein (Citation2013, Citation2014, Citation2017) argues that after the crisis foreign banks in ECE didn’t ‘cut and run’ because they considered the region their second home markets and, in turn, they helped to stabilise the situation, while Nelson (Citation2020) contends that, in the context of financialisation, the heavy presence of foreign-owned banks amplified the regional effects of the global credit crunch in 2008 and the post-crisis years. For their part, Ban and Bohle (Citation2020) claim that the changes in the financial and banking sectors in ECE after the crisis are explained by the particular growth model of each country rather than the origin of financial actors, and that state capacity has been a driver of de-financialisation after the crisis.

Second, within the literature on dependent financialisation, dependency and risk are analysed as unidirectional phenomena. Thereby, (semi-)peripheral economies are dependent on financial actors, financial conditions and capital flows from the core and, in turn, this dependency increases their financial instability (Bonizzi Citation2013, Karwowski and Stockhammer Citation2017, Bonizzi et al. Citation2020, Karwowski Citation2020, inter alia). However, to date, it is not fully understood how, through cross-border ‘financial chains’, foreign financial actors can become dependent on their operations in the periphery and how the increased financial vulnerability in the periphery can feedback instability in the core.

The rise of dependent financialisation in the Baltic states

Since the beginning of the transition, the EU has been a dominant force in shaping capitalism in the ECE (Vaduchova Citation2005, Grabbe Citation2006, Jacoby Citation2010, Citation2014, Bruszt and Vukov Citation2017, Bohle Citation2018a). In particular, the mechanisms of Europeanisation, which refer to the processes of harmonisation of domestic norms, rules, regulations and procedures in compliance with those of the EU (see Radaelli Citation2003), have been a fundamental factor in the ‘external governance’ of the transformation in ECE countries (Schimmelfennig and Sedelmeier Citation2004).

In the case of the Baltic states, EU influence has been a key factor due to their strong commitment to join the continental bloc since the restoration of independence (Abdelal Citation2001, Lane Citation2001, Pridham Citation2005). Thus, in alignment with the strong pro-market orientation of the EU (Bellofiore et al. Citation2010, Pataccini Citation2017), since the beginning of the transition, the Baltic states implemented a set of profound the reforms based on the so-called Washington Consensus, aimed at introducing market economy mechanisms as soon as possible and qualify for EU accession (Kattel Citation2009). Yet, all three countries experienced severe transitional recessions in 1990–1994/5, with GDP declines ranging from 35 per cent (Estonia) to 50 per cent (Latvia and Lithuania) (Svejnar Citation2002). Moreover, the effects of the transitional recession were aggravated by several banking crises (Fleming et al. Citation1997) and the impact of the Russian Financial Crisis in 1998 (Adahl Citation2002). Thus, at the end of 1998, the success of the economic reforms had been severely hampered by successive crises and the banking system was extremely weakened.

In this context, the Baltic governments turned to the Nordic banking groups as strategic investors for the restructuring and consolidation of their domestic banking systems (Sheridan et al., Citation2004, Bohle Citation2018a). This initiative was supported by the EU in the light of their possible accession, as it was considered that foreign banks would help to establish a sound banking system (Pistor Citation2012, Bohle Citation2018a). Additionally, it was expected that their presence would provide international credibility to the domestic financial sectors (Grittersova Citation2017). Thereby, in late 1998 the Baltic banking sector began a process of intensive regional consolidation dominated by two Swedish groups: Swedbank AB and SEB Group (Roolaht and Varblane Citation2009). By 2001, these two groups owned more than two-thirds of the total banking sector assets in Estonia and Lithuania and a substantial share in Latvia, while the overall foreign ownership exceeded 95 per cent in Estonia, 85 per cent in Lithuania and 70 per cent in Latvia (Adahl Citation2002). Almost simultaneously, the Baltic countries were invited to open accession negotiations to join the EU.Footnote2

The history of the boom-and-bust cycle in the Baltic countries in the early 2000s is already well known (Deroose et al. Citation2010, Hübner Citation2011, Kattel and Raudla Citation2013, Sommers and Woolfson Citation2014, among others). Fundamentally, strong inflows of FDI and the expansion of banking credit promoted a rapid economic growth, which accelerated after the simultaneous EU accession, in 2004 (Bohle and Greskovits Citation2012). Thereby, the average annual growth rates of the Baltic republics between 2004 and 2007 reached 10.3 per cent in Latvia, 8.5 per cent in Estonia and 8.2 per cent in Lithuania (Kattel and Raudla Citation2013).

Regarding the role of Europeanisation in the economic boom, Cameron (Citation2009) and Jacoby (Citation2014) show that the liberalisation policies promoted by the EU and the integration into the Single Market, as well as the large liquidity available for new EU members, had a strong pro-cyclical effect. As Medve-Balint (Citation2014) has demonstrated, the EU has been a key player in opening ECE countries to foreign investors. This was done through the financing of national investment promotion agencies and the Commissiońs reports on countries’ progress towards accession, which openly advocated privatisation in the banking sector and the promotion of FDI. Moreover, Jacoby (Citation2010) and Bohle (Citation2018a) assert that the compliance with the European rules and regulations not only opened these economies for capital flows, but also provided legal security for investors, and Ross (Citation2013) argues that harmonisation of the Baltic banking sector rules with EU regulations led to a procyclical relaxation of previously stricter national regulations. In this way, integration with the EU played a crucial role for the rapid foreignisation and expansion of the Baltic banking sector before the crisis.

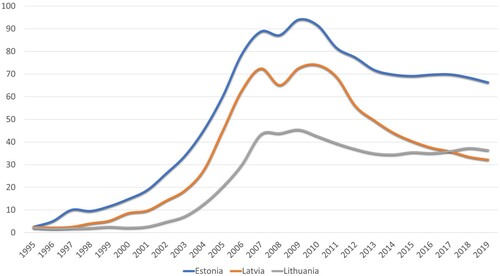

Since their arrival, foreign banks aimed to develop the credit markets, particularly lending to households (Bohle Citation2014, Citation2018b). In the pre-crisis years, annual credit growth to the private sector increased at a rate of 50–70 per cent in Estonia and Latvia, and 40–60 per cent in Lithuania, tripling the ECE average (Herzberg Citation2010). In absolute terms, in 2000–2007, the consolidated debt of the private sector increased by more than 5 times in Lithuania, 6 times in Estonia and 8 times in Latvia. This helps to explain the exponential increase in the debt-to-income ratio of households ().

Figure 1. Gross debt-to-income ratio of Households, 1995–2019 (as per cent). Source: Author’s elaboration based on Eurostat Database. Available online at: http://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/show.do?dataset=tec00104&lang=en.

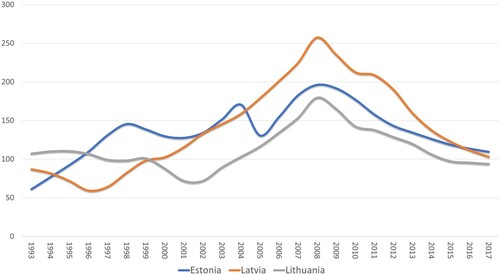

Initially, banking credit in the Baltic countries was funded with deposits from the public. However, since the early 2000s, parent banks began to borrow euros on international capital markets at very low interest rates and to lend this capital to the Baltic subsidiaries (Aarma and Dubauskas Citation2012). This can be seen in the loan-to-deposit ratio of the Baltic countries during this period (). These operations entailed substantial profits for foreign banks, as the returns on Baltic assets were substantially higher than those of Sweden (Kandell Citation2009). In other words, during the boom years foreign banks conducted massive carry trade operations with local households and firms (Kattel Citation2010, Gabor Citation2010a).

Figure 2. Loan-to-deposit ratio, 1993-2017. Source: Author’s elaboration based on World Bank, Global Financial Development Database. Available online at: https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators.

As pointed out in Bortz and Kaltenbrunner (Citation2017), the reduced liquidity premium of currencies at lower ranks of the international monetary hierarchy (such as those of the Baltic states) means that they have to offer higher interest rates to maintain demand. Because of this, Baltic borrowers opted for loans denominated in foreign currency, mainly euros, which had lower interest rates than loans in local currencies. Thus, in 2008, foreign currency loans reached 88 per cent of total credit in Latvia, 85 per cent in Estonia and 64 per cent in Lithuania (EC Citation2010). Additionally, during this period the Baltic governments adopted currency pegs to meet the Euro convergence criteria (Staehr Citation2015), while the economic boom boosted a marked rise in inflation. This combination caused the appreciation of real exchange rates, making interest rates in foreign currency loans even negative in some cases. Meanwhile, lenders considered euro loans riskless due to pegged exchange rates and continued to expand the credit supply (Becker and Jäger Citation2012). All in all, this behaviour fuelled a real estate bubble while favoured non-tradable sectors, leading to the accumulation of massive external liabilities (Kattel and Raudla Citation2013).

Nevertheless, by late 2007 the Baltic economies were showing clear signs of overheating. In response to this situation, as well as the negative global financial outlook posed by the outbreak of the subprime mortgage crisis in the US, foreign banks decided to reduce the credit supply and began to tighten credit conditions (Deroose et al. Citation2010). The situation was aggravated by the bankruptcy of the Lehman Brothers bank in September, which dramatically worsened the international economic environment as well as consumers’ and investors’ confidence. As a consequence of these circumstances, the Baltic states slipped into recession in 2008. The situation was worse in Latvia, where the exposure of the domestic banking sector led to a fiscal crisis, which soon turned into a balance of payments crisis (Pataccini and Eamets Citation2019).

Unlike Estonia and Lithuania, since the beginning of the transition Latvia developed a significant domestic banking sector specialised in non-resident customers (Adahl Citation2002, OECD Citation2016, Pataccini CitationForthcoming). During the GFC, Parex Banka, the second largest bank in the country and the largest non-foreign bank in the Baltics, was doubly exposed to the crisis. On the one hand, like foreign banks, during the boom years Parex relied on European wholesale markets to finance the expansion of credit (Epstein and Rhodes Citation2019). On the other hand, Parex Bank also attracted a significant amount of non-resident depositors. Thus, in the months following the collapse of Lehman Brothers, Parex lost 25 per cent of its deposits, while it had to face the repayment of syndicated loans, equivalent of 4.6 per cent of Latvian GDP (Aslund and Dombrovskis Citation2011). Due to its potential systemic impact, the government decided to nationalise the bank in November (ibid.). Because of that, in February 2009 the government agreed a ‘bailout’ loan with the IMF, the EU and other international actors equivalent to almost 40 per cent of Latvia's GDP.

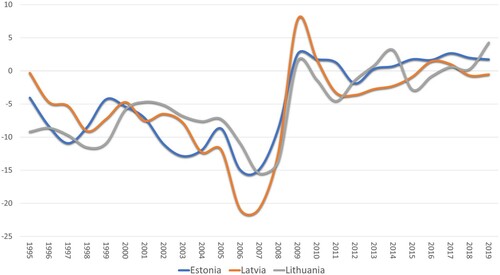

`In order to cope with the crisis, all three Baltic republics opted for austerity and internal devaluation strategies (see Sommers and Woolfson Citation2014). Due to the procyclical nature of the policies applied, the accumulated GDP contraction during the GFC amounted to 17 per cent in Lithuania, 20 per cent in Estonia and 25 per cent in Latvia (Kattel and Raudla Citation2013). The reasons given by governments to justify the choice of internal devaluation strategy are various (see Purfield and Rosenberg Citation2010, Aslund and Dombrovskis Citation2011, Raudla and Kattel Citation2011, Hudson Citation2014). Yet, it is important to mention that initially the IMF advocated for an orthodox external devaluation, while the internal devaluation strategy was mainly promoted by the EU (Lütz and Kranke Citation2014). Above all, the EU was concerned that the devaluation of the Baltic currencies would wreak havoc on the regional financial markets, causing spill-over effects and inducing capital flight from other ECE countries (Aslund Citation2010, Kuokstis and Vilpisauskas Citation2010). This aspect highlights the importance of the regional financial interlinkages, which can be conceptualised through the financial chains approach.

Financial chains and dependent financialisation

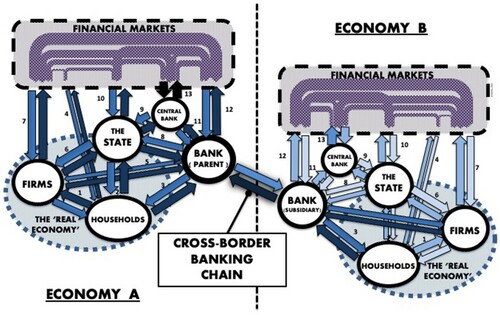

To understand how the concept of financial chains (Sokol Citation2017a, Citation2017b) can provide valuable insights to understand the dynamics of dependent financialization, represents a simplified illustration of abstract financialised economies. The main economic actors intertwined in the financial chains are characterised as households (workers and consumers), firms (productive enterprises), banks (commercial banks and other credit institutions), the state, the central bank and the ‘financial markets’.Footnote3 Two distinctive features of financial markets in financialised economies need to be emphasised. First, they are interconnected with all economic actors. In the past, banks often acted as the main intermediaries between the real economy and financial markets. However, due to the processes of financialisation, financial markets have penetrated all sectors of the economy, transforming the behaviour, practices and activities of all actors (Aalbers Citation2016). Second, due to their enormous expansion, financial markets have achieved a significant influence over the evolution of the overall economy. As many authors argue (Krippner Citation2005, Pettifor Citation2014, among others), this expansion of the financial sector has occurred at the expense of the ´real economý. In this way, financialised economies have become dependent on the performance of the financial sector rather than the real economy, while this has increased their vulnerability. This dependency is exponentially deepened in the case of peripheral and semi-peripheral countries, whose performance becomes dependent on the financial sector, financial actors and financial conditions of central economies.

Figure 3. Financial chains and cross-border banking chains. Source: Courtesy of Martin Sokol - adapted from Sokol (Citation2020); Sokol and Pataccini (Citation2020).

However, ‘financial chains’ are not only established within but also between national economies. One key example of that are the cross-border banking chains. These involve institutions from at least two different countries that have value-transfer links with each other and that may be related, such as parent bank, subsidiaries and branches, or that may be completely independent of each other. Cross-border bank lending is a clear example of cross-border banking chains, as it involves value transfers (e.g. loans-repayments) between the parties involved. In the Baltics like in the rest of ECE, the bulk of cross-border banking is conducted via a parent-subsidiary model, with parent banks being Western European banking groups (Sokol Citation2017b).

The process of Europeanisation has been a key factor in the establishment of financial chains in the Baltic economies. With the aim to qualify for EU membership, the Baltic countries established a set of highly deregulated and lax linkages, especially those that constitute the core of the real economy, such as chain 1 (labour relations and consumption between households and firms), chain 2 (households and state relations based on the exchange of personal taxes and welfare payments) and chain 6 (between firms and the state). The fragility and instability of these linkages have been an obstacle to economic growth during the first decade of the transition, as the economic interaction between domestic actors was ineffective. In turn, the early banking crises were key to liquidating the resources of households (chain 3) and companies (chain 5) deposited in the failing institutions, while they also implied significant stabilisation costs for states (chain 8) and central banks (chain 11). During this period, the involvement of external financial markets was extremely limited, with the exception of Estonia, where foreign investors became involved in the privatisation process of public companies (chains 7 and 10)Footnote4 (see Bohle and Greskovits Citation2012). However, the destruction of value caused by the transitional recession, the banking crises and the Russian financial crisis, added to the limitations inherent in small economies with scarce resources. Thereby, transfers of value through the financial chains were limited and with them, economic growth.

Subsequently, EU support for the arrival of Western institutions in the banking sector produced a substantial change in the economic dynamics of the Baltic countries. Above all, it created cross-border banking chains that involved transfers of value between states, sectors and actors, amplifying the preceding circuits of capital and their volumes. Once these cross-border chains came into operation, they began to transfer resources through lending directly to local actors, mainly households (chain 3) but also to firms (chain 5), which later transformed it into consumption (chain 1) and taxes (chains 2 and 6), creating a virtuous circle of growth that attracted FDI (chain 7) and was fed back by higher rates of employment (chain 1) and expansionary fiscal policies (chains 2 and 6), while in the context of convergence with the euro, the role of central banks guaranteed monetary stability (chains 9 and 11). This dynamic shows that an inflow of credit through cross-border banking channels can contribute to promoting economic growth in the host economy. However, it is also important to note that in the context of dependent financialisation cross-border banking chains have significant implications, both for the ‘dependent’ and the ‘dominant’ economies.

Cross-border banking chains involve asymmetric relationships between parent banks (economy A) and subsidiaries (economy B). In ECE, financial flows between the parent banks and their subsidiaries have been mediated through complex ‘internal capital markets’ (de Haas and Naaborg Citation2006), where the parent companies imposed the conditions on the subsidiaries (e.g. interest rates) and obtained higher profitability than in their home markets. In other words, the extraction of benefits implies that the transfer of value that flows from economy B (‘dependent’) to economy A (‘dominant’) is greater than that flowing in the opposite direction. Additionally, this lending is mostly denominated in foreign currency since (semi-)peripheral economies cannot borrow in their own currency (Gabor Citation2010b, Kaltenbrunner and Painceira Citation2018, Sokol and Pataccini, Citation2020). In the long term this creates a currency mismatch in the host economy that can only be covered with more external funds, either through more credits, FDI or exports. In the case of the Baltic states, the strategy chosen by the governments to resolve this mismatch was to pursue integration with the Eurozone, even at an extremely high social cost (see Woolfson and Sommers Citation2016).

While the Baltic economies became dependent on the capital inflows channelled by foreign banks, one should not underestimate the importance of the Baltic markets for Swedish banking groups. According to Kandell (Citation2009), from 2002 to 2007, the Baltic countries were the main drivers of growth for Swedbank and SEB. As of 2007, profits from the operations in the Baltic countries accounted for over a third of total profits of Swedbank, the main bank operating in the Baltics (Dabušinskas and Randveer Citation2011), and 19 per cent of SEB’s total operating profit (SEB Citation2008). Thus, the case of the Baltic countries shows that dependent financialisation can create asymmetric co-dependencies between (semi-)peripheral economies and financial actors in the core. In other words, given the dominant position and great market power developed by financial actors from the core in the dependent economies, the profitability obtained in the periphery is higher than in their home markets. In this way, total profits for core financial actors become increasingly dependent on their operations in the (semi-)periphery. Importantly, these co-dependencies also have significant implications in terms of bilateral risks.

During the boom years, parent banks borrowed in wholesale capital markets (chain 12) in order to lend to subsidiaries, which then lent to households (chain 3) and firms (chain 5). In this way, while foreign banks were making profits directly from Baltic households and firms, they were ‘chaining’ them to the risks of international financial markets. Consequently, the outbreak of the subprime mortgage crisis and the bankruptcy of the Lehman Brothers bank had a direct impact on the Baltic economies. However, as stated by Lapavitsas and Powell (Citation2013), inter alia, (dependent) financialisation is also shaped by country-specific characteristics and processes. Thus, within their common dynamics, one can also find distinctive trajectories among the Baltic states. In the case of Estonia and Lithuania, which practically didn’t have a domestic banking sector, the only transfer channel for the crisis was through foreign subsidiaries (cross-border banking chain). Moreover, when the crisis hit, the stabilisation costs were borne by parent banks, with assistance from the central banks and the states. On the contrary, in the case of Latvia, the economy was also exposed through domestic banks (chain 12), both via syndicated loans and deposits from non-residents. Therefore, the disruption of this chain caused by the crisis triggered a situation that required direct assistance from the state (chain 8) and the central bank (chain 11) to bail out the domestic banking system, even requiring external assistance (chains 10 and 13).

All in all, the Baltic crisis shows that cross-border banking chains have implications for parent banks and subsidiaries, but also beyond. During the GFC, 60 per cent of Swedbank's losses and 75 per cent of SEB's total losses came from the Baltic subsidiaries (Ingves Citation2010). Due to the heavy exposure of these banks and the strong interconnectedness of the Swedish banking sector (see below), the Baltic crisis posed a threat to the stability of the Swedish financial sector and the whole Swedish economy. Consequently, in 2008 the Central Bank of Sweden, the Riksbank, became directly involved in the management of the crisis in the Baltics and, particularly, in Latvia, in order to contain the potential spill-over effects. The Riksbank extended a €500 million swap line to Latvia and provided bridging loans and liquidity to the Latvian financial system while the country negotiated a rescue loan with the IMF and the EU, and it was prepared to provide liquidity to the larger Baltic region to ensure regional financial stability (Spendzharova and Bayram Citation2016).

In short, the process of Europeanisation of the Baltic countries was key to establishing a complex network of financial chains that had a decisive influence on the performance of their economies. This example shows that while cross-border banking chains can drive economic growth in host countries, they can also create asymmetric co-dependencies between the (semi-)peripheral economies and the financial actors in the core and act as transmission channels for instability and crises in both directions. In the next section, the paper will turn to the analysis of the events after the GFC.

The ‘great retrenchment’ in cross-border banking: changes and continuities in the Baltic states

In the years preceding the GFC, there was a substantial expansion of cross-border banking activities on a global scale (Bremus and Fratzscher Citation2015). However, the crisis triggered a rapid reversal of this trend (Forbes et al. Citation2016). This phenomenon is referred to by many authors as the ‘Great Retrenchment’ in international cross-border banking (Milesi-Ferretti and Tille Citation2011, Emter et al. Citation2019, among others). Accordingly, Lane (Citation2013), Cerutti and Claessens (Citation2017) and Claessens (Citation2017) argue that cross-border banking credit was more affected than other financial capital flows during the GFC. For their part, Bremus and Fratzscher (Citation2015) contend that many banks responded to the GFC by withdrawing from foreign markets, which caused a significant decrease in total cross-border bank claims, and they have maintained lower volumes of cross-border activities since then.

McCauley et al. (Citation2017) argue that the decrease in cross-border banking is mainly a European phenomenon and should be interpreted as a cyclical deleveraging of unsustainably risky bank balance sheets. As shown by Emter et al. (Citation2019), since the end of the GFC and the subsequent euro area sovereign debt crisis, EU banks have reduced their cross-border claims by approximately 25 per cent, while reducing their cross-border loans by approximately 40 per cent, far more than the rest of the world. Additionally, many authors contend that the retrenchment of cross-border banking has been accompanied by an increasing concentration, both at the national and international level (BIS Citation2018, Aldasoro and Ehlers Citation2019).

In short, empirical evidence shows that cross-border banking experienced a significant retrenchment after the GFC, especially in relation to EU banks, while the concentration in the sector has deepened. The effect of this phenomenon in the Baltic countries will be analysed below.

Cross-border banking in the Baltics after the crisis

In line with the transformations that were taking place at the EU level, ECE countries also underwent a series of substantial changes in cross-border banking and capital flow dynamics during and after the GFC. After the Lehman Brother’s collapse, several countries in the region experienced sudden stops and reversal of capital flows (Gros and Alcidi Citation2015). Foreign banks in the Baltic states followed the EU trends and reduced cross-border operations, curtailed loans, and shed assets in their efforts to reduce risk exposure and restore their capital ratios (BIS, Citation2018). Moreover, one of the main changes was that they committed to financing their operations mainly with local deposits rather than parents’ funding (Lahnsteiner Citation2020).

In addition to these aspects, it is important to note that after the GFC, banks also faced tighter regulations. At the EU level, the European Systemic Risk Board (ESRB) was created in 2010, which is responsible for the macroprudential oversight of the EU financial system and the prevention of systemic risk.Footnote5 At the sub-regional level, in 2011, the Nordic-Baltic Macroprudential Forum (NBMF) was established, which involves both the governors of the central banks and the heads of supervisory authorities, and aims to promote cooperation in the conduct of macroprudential policies at the regional level (Farelius and Billborn Citation2016).

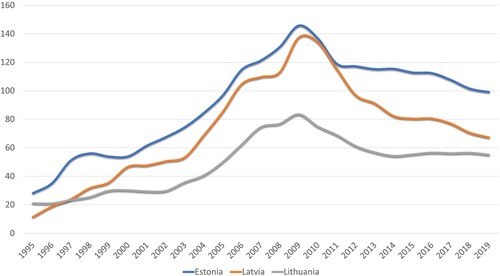

All in all, the new banking policies and tighter supervision after the GFC have promoted significant changes in the financial indicators of the Baltic countries. As external financing declined, locally operating banks were forced to balance loans with deposits. This can be seen in the marked decrease in the loan-to-deposit ratios from 2008–2009 onwards (). Likewise, the reduction in credit supply also drove a decline in the private sector's debt-to-GDP ratios ().

Figure 4. Consolidated private debt to GDP, 1995–2019 (as per cent). Source: Author’s elaboration based on Eurostat database. Available online at: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/tgm/table.do?tab=table&init=1&plugin=1&language=en&pcode=tipspd20.

On the other hand, the Baltic economies also underwent some significant changes. Following the implementation of the internal devaluations, all three Baltic republics succeeded in adopting the euro after the GFC. However, they did not do so simultaneously: Estonia joined the eurozone on 1 January 2011; Latvia on 1 January 2014; and Lithuania on 1 January 2015. Likewise, after the crisis economic growth became more export-oriented (Dunhaupt and Hein Citation2019): as of 2019, exports of goods and services as a percentage of GDP amounted to 72.6 per cent in Estonia, 60 per cent in Latvia, and 78 per cent in Lithuania.Footnote6 These changes have contributed to keep foreign trade close to balance (). Furthermore, during these years Baltic states’ public debt-to-GDP ratios remained among the lowest in the EU.Footnote7 However, the increase in exports failed to offset the fall in capital inflows. As a result, the economic recovery was uneven and slow: Lithuania returned to its pre-crisis level in 2013, Estonia in 2016 and Latvia in 2017.

Figure 5. Current account balance as per cent of GDP, 1995-2019. Source: Author’s elaboration based on International Monetary Fund, World Economic Outlook Database, April 2018. Available online at: https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2020/01/weodata/index.aspx.

As can be seen, during the last decade there have been notable changes in the Baltic economies. Foreign banks have applied more conservative policies, bringing down debt ratios and the Baltic countries have also managed to improve some of their main macroeconomic imbalances and succeeded in adopting the Euro, eliminating foreign exchange risk within the EU. However, despite the reversal of some key indicators, it is important to note that the features of dependent financialisation have not disappeared. On the contrary, in the context of in the international financial retrenchment, the banking structure of the Baltic states has deepened its preceding trends. Many national banks sank during and after the GFC because they were unable to overcome the effects of the crisis and the aftermath. These include the above-mentioned Parex Bank, but also Latvijas Krājbanka, Trasta Komercbanka, PNB Banka (Latvia), Snoras Bankas, Ukio Bankas (Lithuania) and Versobank (Estonia), among others. Additionally, in March 2020 Handelsbanken (Sweden) ceased operations in the Baltics due to low profitability and high costs (Reuters Citation2020). The sector also went through a phase of consolidation led by foreign institutions. Thereby, in 2013 Swedbank acquired the Baltic operations of UniCredit Bank (Italy) and in October 2017, Nordea and DNB combined their Baltic businesses to create Luminor Bank AS (Luminor Citation2017). Finally, due to money laundering investigations (see below), in 2018 ABLV (Latvia) started the process of voluntary liquidation and the branch of Danske bank in Estonia was forced to close in 2019 (Sorensen Citation2019). Thus, the collapses, mergers and acquisitions occurred during and after the GFC led to an increasing concentration in the Baltic banking sector. In this way, by the end of 2019, the three main foreign banks in the Baltics have increased their market shares to approximately 85 per cent of total bank assets in Estonia (Finantsinspektsioon Citation2019) and Lithuania (Lietuvos Bankas Citation2020), and over 60 per cent in Latvia (FLA Citation2019).

In turn, the evolution of bank lending in the Baltic states should also be seen in the light of the unconventional monetary policies conducted by central banks of the core economies, as well as their effects in other peripheral and semi-peripheral economies. In response to the GFC, the US Federal Reserve, the Bank of England, the ECB, the Swedish Risksbank and other central banks around the world started buying assets from commercial banks with the aim of creating money in the banking system and promoting economic growth. This policy is usually known as Quantitative Easing (QE). However, by keeping interest rates extremely low within the Eurozone, ECB´s QE policies also affected the profitability of banks operating in the Eurozone and their incentives to extend loans to customers. As stated by Demertzis and Wolf (Citation2016) ‘QE reduces long-term yields and thereby reduces term spreads. With this, the lending-deposit ratio spread falls, making it harder for banks to generate net interest income on new loans’. Instead, a substantial share of the liquidity generated by QE policies was geared towards assets in (semi-)peripheral economies, in search of higher rates of profit, mostly through carry trade operations (Fernandez and Aalbers Citation2020). However, it is worth noting that while the Baltic states were experiencing a drastic reduction in private debt levels, the Global South economies were accumulating the ‘largest, fastest, and most broad-based’ debt wave in half a century (World Bank Citation2019, Ayhan Kose et al. Citation2020). This phenomenon highlights the variegated dynamics of dependent financialisation in each particular context.

In sum, the evolution of private loans in the Baltic states shows that the dynamics of dependent financialisation can be strongly pro-cyclical. Foreign financial actors took advantage of the opportunities offered by fast-growing economies, but they curtailed their operations significantly when the growth rate and profitability declined, deepening the economic downturn. In turn, it is important to note that the decline in foreign credit in the Baltics was simultaneous to a substantial increase in foreign lending in the Global South. This dynamic suggests that the cycles of expansion and retreat of dependent financialisation in particular (semi-)peripheral countries can be linked to their economic performance, but also to the conditions in international financial markets, such as those generated by the QE policies.

Financial vulnerabilities in the face of COVID-19 pandemic and beyond

The outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic in early 2020 has posed new threats and challenges for the Baltic economies. During the first year of the pandemic, a major crisis was averted through massive interventions by central banks and stimulus packages by national governments (see Sokol Citation2020, Sokol and Pataccini Citation2020). However, due to the persistent characteristics of dependent financialisation, there are still several potential sources of instability. In particular, since the two main banks operating in the Baltics are Swedish subsidiaries, events in this country have direct implications for their economies.

In recent years the Swedish banking sector has accumulated various imbalances, while displaying strong features of financialisation (Belfrage and Kallifatides Citation2018). For instance, more than 50 percent of the financial needs of Swedish banks are covered in international markets (Stenfors Citation2014). Meanwhile, Sweden has experienced a credit boom: in 2020 private debt amounted to almost 310 per cent of GDP, which in turn has fuelled a housing bubble (Johnson Citation2019).Footnote8 Also, Swedish banks are closely interconnected, as they buy a significant part of each other's covered bonds. According to the Swedish central bank, the combined holdings of the securities of each of the four major Swedish banks over three years average approximately SEK 150 billion (approximately EUR 13 billion), corresponding to approximately 25 per cent of their Common Equity Tier 1 (CET1) (Sveriges Riksbank Citation2019).

Thus, a fall in economic activity and national income would soon transfer the problem to banks, which will find increasing difficulties to collect their credits. In turn, a recession can also burst the housing bubble, which would reduce the value of the collateral and private wealth. Second, given the high level of interconnectedness of Swedish banks, the problems of one bank can quickly spread to others. Furthermore, it is important to remember that Sweden does not belong to the Eurozone, therefore, banks take credits in foreign currency -mainly USD- (Stenfors Citation2014), adding exchange risk to the equation.

Additionally, in recent years, several Scandinavian banks have been involved in public scandals related to money laundering activities (see Milne and Winter Citation2018). In this context, in March 2020, the Swedish Financial Supervisory Authority imposed a record fine of SEK 4 billion (approximately € 360 million) on Swedbank, and in June 2020, the Swedish financial supervisory authority fined SEB bank 1 billion SEK (€ 96 million) for ‘deficiencies in its work to combat anti-money laundering in the Baltics’ (LSM Citation2020). However, criminal investigations in the Baltics and the United States continue. Thus, if Swedish groups face new fines, this may reduce banks’ capital and eventually lead to parent banks taking steps involving their operations in the Baltic countries to cope with the costs of money laundering investigations.

Consequently, the Swedish economic imbalances, the high level of leverage in foreign currency and the interconnectedness of Swedish banks and the ongoing investigations on money laundering activities have direct implications for the Baltic economies. If parent banks face difficulties, they can pass the problem on to their Baltic subsidiaries through three main channels a) a decrease in cross-border lending; b) an increase in funding costs for subsidiaries; and c) greater volatility of deposits due to growing concern of depositors and lack of confidence. All these risks seem aggravated by the uncertainties created by the COVID-19 pandemic.

In turn, even after the crisis the Baltic states represented a significant source of profit for Swedish banks. In 2019 more than 20 per cent of Swedbank's revenue (Swedbank Citation2020) and 13 per cent of SEB's revenue (SEB Citation2020) came from these countries, while profitability in the Baltic banking sector has been well above the EU average since the end of the GFC (Jociene Citation2015, EBF Citation2019). In this context, the withdrawal of support from Central Banks and States in the post-pandemic scenario could trigger a domino effect with severe implications on the whole Baltic Sea region. For now, a year seems too short a time to identify the real impact of the COVID-19 crisis on the banking sector and financial chains in the Baltic Sea region. However, this situation should be closely scrutinised in the near future. While a turmoil in the Swedish banking sector would have a direct impact on the Baltic economies, instability in the Baltic banking sector could also have significant effects on the Swedish banking groups, which can rapidly spread to the wider sector and the overall economy.

Conclusions

This paper has aimed to contribute to the academic debate on dependent financialisation. This is a phenomenon characterised by the asymmetric relationship between peripheral and semi-peripheral economies, on the one hand, and core economies, on the other, in which the former depend on capital flows, financial conditions and the financial actors of the latter. For this, the research has used the Baltic countries as case studies, since they represent paradigmatic examples of dependent financialisation. The paper’s findings could be summarised as follows:

First, the paper shows that Europeanisation has been a key driver of dependent financialisation in ECE. The process of economic and financial integration, as well as the harmonisation with the institutional framework of the EU, has promoted the establishment of asymmetric relations between the developed economies of the centre and the new member states of the Eastern periphery, in which banking groups were the main actors.

Second, the case of the Baltic countries shows that dependent financialisation can create asymmetric co-dependencies between (semi-)peripheral economies and core financial actors, which can act -via financial chains- as transmission channels of instability and crisis in both directions. While during the boom years the Baltic economies became dependent on the capital flows channelled by foreign banks’ subsidiaries, a substantial share of the Swedish groups’ profit was generated in the Baltic economies, whose conditions offered much higher profitability than in their home markets. However, the GFC showed that foreign banking groups were heavily exposed to risks stemming from their subsidiaries and they could spread the turmoil to the Swedish financial sector and the wider economy. The bilateral nature of exposure to risk in dependent financialisation is confirmed by the direct involvement of the Riksbank in the management of the Baltic crises in order to contain the spillover effects.

Third, the article suggests that dependent financialisation is a changing phenomenon that has a markedly pro-cyclical nature. Likewise, it is important to note that the main features of dependent financialisation in the Baltics, namely the high levels of concentration and foreign ownership of their banking sectors, have deepened in the years following the GFC. This situation generates various sources of risk, while it leaves the door open to potentially new boom-and-bust cycles, with the same or worse consequences than in 2008–2010.

Based on these findings, the paper raises two main questions for future research. First, it is still too early to assess the real effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, in the coming years it will be necessary to study whether and how the pandemic reconfigures the asymmetric links of dependent financialisation. Second, until now, studies of dependent financialisation have focused on the links between dependent and dominant economies. However, it is not yet understood how dependent economies are linked to each other and what their interrelationships are. Thus, it is considered that addressing these lines of research is critical for a deeper understanding of dependent financialisation and its implications.

Acknowledgements

This research has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) Consolidator Grant under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (Grant agreement No. 683197) via GEOFIN project (www.geofinresearch.eu), and from the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) via PostDocLatvia, project agreement Nr. 1.1.1.2/VIAA/3/19/491.

Additionally, the author wishes to thank GEOFIN’s Principal Investigator, Dr. Martin Sokol, and GEOFIN colleagues for their valuable contributions and support, as well and the journal editors and the two blind reviewers for their excellent comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Throughout this paper, the terms ‘Baltic states’, ‘Baltic Republics’, ‘Baltic countries’ and ‘Baltics’ are used interchangeably.

2 Estonia was invited to open accession negotiations in 1997, while Latvia and Lithuania, in 1999.

3 The term ‘financial markets’ is used to refer to a broad range of financial actors other than commercial banks, including investment banks, pension funds, sovereign welfare funds, insurers, mutual funds, hedge funds, private equity firms, asset managers, etc.

4 For the sake of simplicity, in this analysis FDI is attributed to ´financial markets’, although in reality it is carried out by a broad range of foreign actors.

5 European Systemic Risk Board, ‘Mission & establishment’. Available online at: https://www.esrb.europa.eu/about/background/html/index.en.html.

6 World Bank, World Development Indicators Database ‘Exports of goods and services (% of GDP). Available online at: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NE.EXP.GNFS.ZS

7 Even Latvia, after requesting a sizeable bailout loan, managed to repay the loan ahead of schedule and keep public debt low (Eglitis Citation2013).

8 OECD, ‘Financial Indicators – Stocks; Private sector debt, as a percentage of GDP’. Available online at: https://stats.oecd.org/index.aspx?queryid=34814.

References

- Aalbers, M.B., 2016. The financialization of housing: a political economy approach. London: Routledge.

- Aalbers, M.B., 2017. The variegated financialization of housing. International journal of urban and regional research, 41, 542–554. doi:10.1111/1468-2427.12522.

- Aarma, A. and Dubauskas, Gediminas, 2012. The foreign commercial banks in the Baltic states: aspects of the financial crisis internationalization. European journal of business and economics, 5, 1–71.

- Abdelal, R., 2001. National purpose in the World economy: Post-Soviet states in comparative perspective. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Adahl, M. 2002. Banking in the Baltics-The Development of the Banking Systems of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania since Independence. The Internationalization of Baltic Banking (1998-2002). Focus on Transition, Oesterreichische Nationalbank. http://www.oenb.at/de/img/adahl_ftr_2 02_tcm14-10384.pdf.

- Alami, I., et al. 2021. International financial subordination: a critical research agenda. Greenwich Papers in Political Economy GPERC 85.

- Aldasoro, I. and Ehlers, T. 2019. Concentration in cross-border banking, BIS Quarterly Review, Bank for International Settlements, June. Available online at: https://www.bis.org/publ/qtrpdf/r_qt1906b.pdf.

- Aslund, A., 2010. The last shall be the first. The East European financial crisis. Washington, DC: Peterson Institute for International Economics.

- Aslund, A. and Dombrovskis, V., 2011. How Latvia came through the financial crisis. Washington DC: Peterson Institute for International Economics.

- Ayhan Kose, M., et al., 2020. Global waves of debt: causes and consequences. advance edition. Washington, DC: International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank.

- Ban, C. and Bohle, D., 2020. Definancialization, financial repression and policy continuity in East-Central Europe. Review of international political economy, doi:10.1080/09692290.2020.1799841.

- Becker, J., et al., 2010. Peripheral financialization and vulnerability to crisis: a regulationist perspective. Competition & change, 14 (3–4), 225–247.

- Becker, J. and Jäger, J., 2012. Integration in crisis: a regulationist perspective on the interaction of European varieties of capitalism. Competition and change, 16 (3), 169–87.

- Belfrage, C. and Kallifatides, M., 2018. Financialisation and the new Swedish model. Cambridge journal of economics, 42, 875–899.

- Bellofiore, R., Garibaldo, F., and Halevi, J., 2010. The global crisis and the crisis of neomercantilism. In: L. Panitch, G. Albo, and V. Chibber, eds. Socialist register 2011: the crisis this time. London: Merlin, 120–146.

- BIS - Bank for International Settlements. 2018. Structural changes in banking after the crisis. Committee on the Global Financial System Papers, 60, January 2018.

- Bohle, D., 2014. Post-Socialist housing meets transnational finance: foreign banks, mortgage lending, and the privatization of welfare in Hungary and Estonia. Review of international political economy, 21 (4), 913–48.

- Bohle, D., 2018a. European integration, capitalist diversity and crises trajectories on Europe’s Eastern periphery. New political economy, 23 (2), 239–253.

- Bohle, D., 2018b. Mortgaging Europe’s periphery. Studies in comparative international development, 53, 196–217.

- Bohle, D. and Greskovits, B., 2012. Capitalist diversity on Europe’s periphery. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Bonizzi, B., 2013. Financialization in developing and emerging countries. International journal of political economy, 42 (4), 83–107.

- Bonizzi, B., Kaltenbrunner, A., and Powell, J., 2020. Subordinate financialization in emerging capitalist economies. In: P. Mader, D. Mertens, and N. van der Zwan, eds. The Routledge international handbook of financialization. London: Routledge, 177–187.

- Bonizzi, B., Kaltenbrunner, A., and Powell, J. 2021. Financialised capitalism and the subordination of emerging capitalist economies. Greenwich Papers in Political Economy GPERC 84.

- Bortz, P.G. and Kaltenbrunner, A., 2017. The international dimension of financialization in developing and emerging economies. Development and change, 49 (2), 375–393.

- Bremus, F. and Fratzscher, M., 2015. Drivers of structural change in cross-border banking since the global financial crisis. Journal of international money and finance, 52, 32–59.

- Brown, A., Passarella, M.V., and Spencer, D.A. 2015. The Nature and Variegation of Financialisation: A Cross-country Comparison. FESSUD Working Paper Series, No.127.

- Brown, A., Spencer, D.A., and Passarella, M.V., 2017. The extent and variegation of financialisation in Europe: a preliminary analysis. Revista de Economia Mundial, 46, 49–69.

- Bruszt, L. and Vukov, V., 2017. Making states for the single market: european integration and the reshaping of economic states in the southern and Eastern peripheries of Europe. West European politics, 40 (4), 663–87.

- Büdenbender, M. and Aalbers, M., 2019. How subordinate financialization shapes Urban development: the rise and fall of Warsaw's Służewiec Business district. International journal of urban and regional research, 434, 666–684.

- Cameron, D., 2009. Creating market economies after communism: the impact of the European Union. Post-Soviet affairs, 25 (1), 1–38.

- Cerutti, E. and Claessens, S., 2017. The great cross-border bank deleveraging: supply constraints and intra-group frictions. Review of finance, 2017, 201–236.

- Choi, C., 2020. Subordinate financialization and financial subsumption in South Korea. Regional studies, 54 (2), 209–218.

- Claessens, S., 2017. Global banking: recent developments and insights from research. Review of finance, 21 (4), 1513–55.

- Correa, E., Vidal, G., and Marshall, W., 2012. Financialization in Mexico: trajectory and limits. Journal of post Keynesian economics, 35 (2), 255–75.

- Dabušinskas, A. and Randveer, M. (2011). The financial crisis and the Baltic countries. In: M. Beblavý, D. Cobham, and L. Ódor (eds.), The Euro area and the financial crisis (pp. 97–128). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9781139044554.008

- De Haas, R. and Naaborg, I., 2006. Foreign banks in transition countries: to whom do they lend and how are they financed? Financial markets, institutions, and instruments, 15 (4), 159–199.

- Demertzis, M. and Wolff, G. B, 2016. The effectiveness of the European Central Bank’s Asset Purchase Programme. Bruegel Policy Contribution 2016/10.

- Deroose, S., et al. 2010. The Tale of the Baltics: Experiences, Challenges Ahead and Main Lessons. ECFIN Economic Brief 10. Available from: http://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/publications/economic_briefs/2010/pdf/eb10_en.pdf.

- Dünhaupt, P., and Hein, E., 2019. Financialization, distribution, and macroeconomic regimes before and after the crisis: a post-Keynesian view on Denmark, Estonia, and Latvia. Journal of baltic studies, 50 (4), 435–465.

- EBF - European Banking Federation. 2019. Facts and figures – Banking sector performance. Available online from: https://www.ebf.eu/facts-and-figures/banking-sector-performance/.

- EC - European Commission. 2010. Cross Country Study: Economic Policy Challenges in the Baltics. Occasional Papers 58. Available online from: http://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/publications/occasional_paper/2010/pdf/ocp58_en.pdf.

- Eglitis, A. 2013. Latvian austerity fervor outstrips IMF after loan payback. Bloomberg January 3, 2013. Available online from: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2013-01-02/latvian-austerity-fervor-outstrips-imf-after-early-loan-payback.

- Emter, L., Schmitz, M., and Tirpák, M., 2019. Cross-border banking in the EU since the crisis: what is driving the great retrenchment? Review of world economics, 155, 287–326.

- Epstein, R., 2013. Central and East European bank responses to the financial ‘crisis’: do domestic banks perform better in a crisis than their foreign-owned counterparts? Europe-Asia studies, 65 (3), 528–547.

- Epstein, R., 2014. When do foreign banks ‘Cut and run’? Evidence from West European bailouts and East European markets. Review of international political economy, 21 (4), 847–77.

- Epstein, R.A., 2017. Banking on markets: The transformation of bank-state ties in Europe and beyond. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Epstein, R. and Rhodes, M., 2019. Good and bad banking on Europe’s periphery: pathways to catching up and falling behind. West European Politics, 42 (5), 965–988.

- Farelius, D. and Billborn, J., 2016. Macroprudential Policy in the Nordic-Baltic Countries. Sveriges riksbank economic review, 1, 129–142.

- Fernandez, R. and Aalbers, M., 2020. Housing financialization in the global South: in search of a comparative framework. Housing Policy Debate, 30 (4), 680–701.

- Finance Latvia Association – FLA. 2019. Operating results of Latvian commercial banks 4th quarter 2019. Available online from: https://www.financelatvia.eu/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Detailed-results-of-Latvian-commercial-banks-4th-quarter-2019.pdf.

- Finantsinspektsioon. 2019. Overview of the Estonian financial market 2019. Available online from: https://www.fi.ee/sites/default/files/fi_finantsturg_2019_eng.pdf.

- Fleming, A., Chu, L., and Bakker, M., 1997. Banking crises in the Baltics. Finance and development, March 1997, 42–45.

- Forbes, K., Reinhardt, D., and Wieladek, T. 2016. The spillovers, interactions, and (un) intended consequences of monetary and regulatory policies, National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper No. 22307. Available online from: https://www.nber.org/papers/w22307.

- Gabor, D., 2010a. Central banking and financialization: a romanian account of how Eastern Europe became subprime. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer.

- Gabor, D., 2010b. (De)Financialization and crisis in Eastern Europe. Competition & change, 14 (3–4), 248–270.

- Gabor, D. 2013. The Romanian financial system: from central bank-led to dependent financialization. FESSUD, Studies in Financial Systems No. 5.

- Girón, A. and Solorza, M., 2015. Déjà vu” history: the European crisis and lessons from Latin America through the glass of financialization and Austerity measures. International journal of political economy, 44 (1), 32–50.

- Grabbe, H., 2006. The EU’s transformative power. Europeanization through conditionality in Central and Eastern Europe. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Grittersova, J., 2017. Borrowing credibility: global banks and monetary regimes. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

- Gros, D. and Alcidi, C., 2015. Country adjustment to a ‘sudden stop’: does the euro make a difference? International economics and economic policy, 12 (1), 5–20.

- Herzberg, V. 2010. Assessing the Risk of Private Sector Debt Overhang in the Baltic Republics. IMF Working Paper WP/10/250. Available online at: http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2010/wp10250.pdf, accessed 6 August 2012.

- Hübner, K., 2011. Baltic tigers: the limits of unfettered liberalization. Journal of baltic studies, 42 (1), 81–90.

- Hudson, M., 2014. Stockholm syndrome in the Baltics: Latvia’s Neoliberal War against labor and industry. In: J. Sommers, and C. Woolfson, eds. The contradictions of Austerity: the socio-economic costs of the Neoliberal Baltic model. London: Routledge, 17–43.

- Ingves, S. 2010. The Crisis in the Baltic - the Riksbank’s Measures, Assessments and Lessons Learned. Sveriges Riksbank. Available online from: https://www.riksbank.se/contentassets/6e8e91c80a6247b5b51bb303a3143f22/tal_100202e.pdf.

- Jacoby, W., 2010. Managing globalization by managing Central and Eastern Europe: The EU’s backyard as threat and opportunity. Journal of european public policy, 17 (3), 416–432.

- Jacoby, W., 2014. The EU factor in fat times and in lean: did the EU amplify the boom and soften the bust? Journal of Common Market Studies, 52 (1), 52–70.

- Jociene, A., 2015. Scandinavian bank subsidiaries in the Baltics: have they all behaved in a similar way? Intellectual Economics, 9 (1), 43–54.

- Johnson, S. 2019. Sweden grapples with housing market reform as risks mount. Reuters December 18, 2019. Available online from: https://www.reuters.com/article/sweden-economy-housing/sweden-grapples-with-housing-market-reform-as-risks-mount-idUSL8N28L43A.

- Kaltenbrunner, A. and Painceira, J.P., 2018. Subordinated financial integration and financialisation in emerging capitalist economies: the Brazilian experience. New Political Economy, 23 (3), 290–313.

- Kandell, J. 2009. Swedish Banks Suffer Baltic Losses. Institutional investor May 4, 2020. Available online from: https://www.institutionalinvestor.com/article/b150q9whgpvv8z/swedish-banks-suffer-baltic-losses.

- Karwowski, E., 2020. Economic development and variegated financialization in emerging economies. In: P. Mader, D. Mertens, and N van der Zwan, eds. The Routledge international handbook of financialization. London: Routledge, 162–176.

- Karwowski, E. and Stockhammer, E., 2017. Financialisation in emerging economies: a systematic overview and comparison with Anglo-Saxon economies. Economic and political studies, 5 (1), 60–86.

- Kattel, R., 2009. The rise and fall of the Baltic republics. Development and transition, 13, 11–13.

- Kattel, R., 2010. Financial and Economic crisis in Eastern Europe. Journal of post-Keynesian economics, 33 (1), 41–60.

- Kattel, R. and Raudla, R., 2013. The Baltic Republics and the crisis of 2008–2011. Europe-Asia studies, 65 (3), 426–449.

- Krippner, G., 2005. The financialization of the American economy. Socio-Economic review, 3, 173–208.

- Kuokstis, V. and Vilpisauskas, R. 2010. Economic adjustment to the crisis in the Baltic Republics in comparative perspective, Paper presented at the 7th Pan-European International Relations Conference, September, Stockholm.

- Lahnsteiner, M. 2020. The refinancing of CESEE banking sectors: What has changed since the global financial crisis? Focus on European Economic Integration. Oesterreichische Nationalbank (Austrian Central Bank), issue Q1/20, 6-19.

- Lane, T., 2001. The Baltic states: Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. London and New York: Routledge.

- Lane, P.R., 2013. Credit dynamics and financial globalisation. National institute economic review, 225 (1), R14–R22.

- Lapavitsas, C. and Powell, J., 2013. Financialisation varied: a comparative analysis of advanced economies. Cambridge journal of regions, economy and society, 6, 369–79.

- Lapavitsas, C. and Soydan, A. 2020. Financialisation in Developing Countries: Approaches, Concepts, and Metrics. SOAS Department of Economics, Working Paper No. 240, London: SOAS University of London.

- Lietuvos Banka. 2020. Financial Stability Review 2019. Available online from: https://www.lb.lt/en/reviews-and-publications/category.39/series.169.

- LSM. 2020. SEB bank hit with huge fine in Sweden over Baltic banking mistakes. Latvijas Sabiedriskie Mediji, June 26 2020. Available online from: https://eng.lsm.lv/article/economy/banks/seb-bank-hit-with-huge-fine-in-sweden-over-baltic-banking-mistakes.a365044/.

- Luminor. 2017. The merger of Nordea and DNB will take place on 1st of October. Available online from: https://www.luminor.lv/lv/jaunumi-lidz-2017-10-01/merger-nordea-and-dnb-will-take-place-1st-october.

- Lütz, S. and Kranke, M., 2014. The European rescue of the Washington consensus? EU and IMF lending to Central and Eastern European countries. Review of international political economy, 21 (2), 310–338. doi:10.1080/09692290.2012.747104.

- Mader, P., Mertens, D., and van der Zwan, N. (eds.) 2020. The Routledge international handbook of financialization. London: Routledge.

- McCauley, R.N., et al., 2017. Financial deglobalisation in banking? Journal of international money and finance, 94, 116–131.

- Medve-Bálint, G., 2014. The role of the EU in shaping FDI flows to East Central Europe. Journal of common market studies, 52 (1), 35–51.

- Milesi-Ferretti, G.M. and Tille, C., 2011. The great retrenchment: international capital flows during the global financial crisis. Economic policy, 26 (66), 289–346.

- Milne, R. and Winter, D. 2018. Danske: anatomy of a money laundering scandal. Financial Times, December 19, 2020. Available online at: https://www.ft.com/content/519ad6ae-bcd8-11e8-94b2-17176fbf93f5.

- Myant, M. and Drahokoupil, J., 2012. International integration, varieties of capitalism, and resilience to crisis in transition economies. Europe-Asia studies, 64 (1), 1–33.

- Nelson, S.C., 2020. Banks beyond borders: internationalization, financialization, and the behavior of foreign-owned banks during the global financial crisis. Theory and society, 49 (2), 307–327.

- Nölke, A. and Vliegenthart, A., 2009. Enlarging the varieties of capitalism: the emergence of dependent market economies in East Central Europe. World politics, 61 (4), 670–702.

- OECD, 2016. Latvia: review of the financial system. Paris: OECD. Available online from: https://www.oecd.org/finance/Latvia-financial-markets-2016.pdf.

- Pataccini, L., 2017. From “Communautaire Spirit” to the “Ghosts of Maastricht”: European integration and the rise of financialization. International journal of political economy, 46 (4), 267–293.

- Pataccini, L. 2020. Western Banks in the Baltic States: a preliminary study on transition, Europeanisation and financialisation. GEOFIN Working Paper 11. Dublin: GEOFIN research, Trinity College Dublin. Available online from: https://geofinresearch.eu/outputs/working-papers/.

- Pataccini, L. and Eamets, R., 2019., Austerity versus pragmatism: a comparison of Latvian and Polish economic policies during the great recession and their consequences Ten years later. Journal of Baltic Studies, 50 (4), 467–494.

- Pataccini, L., Forthcoming. From post-socialist transition to the COVID-19 crisis: cycles, drivers and perspectives of subordinate financialization in Latvia. Journal of Baltic Studies, (in press).

- Pataccini, L., Kattel, R., and Raudla, R., 2019. Introduction: Europeanization and financial crisis in the Baltic Sea region: implications, perceptions, and conclusions ten years after the collapse. Journal of Baltic Studies, 50 (4), 403–408.

- Pettifor, A., 2014. Just money: how society Can break the despotic power of finance. Margate: Commonwealth Publishing.

- Pistor, K., 2012. Into the void: governing finance in Central and Eastern Europe. In: G Roland, ed. Economies in transition. Studies in development economics and policy. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 134–152.

- Pridham, G., 2005. Designing democracy: EU enlargement and regime change in post-communist Europe. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Purfield, C. and Rosenberg, B. 2010. Adjustment under a Currency Peg: Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania during the Global Financial Crisis 2008-09, International Monetary Fund Working Paper 10/213. Available online from: http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2010/wp10213.pdf.

- Radaelli, C., 2003. The Europeanization of public policy. In: K. Featherstone and C. Radaelli, eds. The politics of Europeanization. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 27–56.

- Raudla, R. and Kattel, R., 2011. Why did Estonia choose fiscal retrenchment after the 2008 crisis? Journal of public policy, 31 (2), 163–86.

- Raviv, O., 2008. Central Europe: predatory finance and the financialization of the New European periphery. In: L. Robertson, ed. Power and politics after financial crises. International political economy series. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 168–186.

- Reuters. 2020. Sweden's Handelsbanken says to exit the Baltics. Reuters, May 16, 2019. Available online from: https://www.reuters.com/article/handelsbanken-baltics/swedens-handelsbanken-says-to-exit-the-baltics-idUSFWN22R1GQ.

- Rodrigues, J., Santos, A.C., and Teles, N., 2016. Semi-peripheral financialisation: the case of Portugal. Review of international political economy, 23 (3), 480–510.

- Roolaht, T. and Varblane, U., 2009. The inward-outward dynamics in the internationalization of Baltic banks. Baltic journal of management, 4 (2), 221–242.

- Ross, M., 2013. Regulatory experience in the baltics. In: K. Atanas and Z. Sanne, eds. Banking in Central and Eastern Europe and Turkey: Challenges and opportunities. Luxembourg: European Investment Bank, 73–81.

- Santos, A.C., Rodrigues, J., and Teles, N., 2018. Semi-peripheral financialisation and social reproduction: the case of Portugal. New political economy, 23 (4), 475–494.

- Schedelik, M., et al., 2020. Comparative capitalism, growth models and emerging markets: the development of the field. New political economy, 26 (4), 514–526. doi:10.1080/13563467.2020.1807487.

- Schimmelfennig, F. and Sedelmeier, U., 2004. Governance by conditionality: EU rule transfer to the candidate countries of Central and Eastern Europe. Journal of European public policy, 11 (4), 661–79.

- SEB.. 2008. Annual report 2008. Available online from: https://sebgroup.com/investor-relations/reports-and-presentations/annual-reports.

- SEB. 2020. Annual report 2019. Available online from: https://sebgroup.com/investor-relations/reports-and-presentations/annual-reports.

- Sheridan, N., et al., 2004. Capital markets and financial intermediation in the Baltics. International Monetary Fund, Occasional paper 228.

- Socoloff, I., 2020. Subordinate financialization and housing finance: the case of indexed mortgage loans’ coalition in Argentina. Housing policy debate, 30 (4), 585–605.

- Sokol, M., 2013. Towards a “newer” economic geography? injecting finance and finacialization into economic geographies. Cambridge journal of regions, economy and society, 6 (3), 501–515.

- Sokol, M., 2017a. Financialisation, financial chains and uneven geographical development: towards a research agenda. Research in international business and finance, 39, 678–685.

- Sokol, M. 2017b. Western banks in Eastern Europe: New geographies of financialisation (GEOFIN research agenda). GEOFIN Working Paper No. 1. Dublin: GEOFIN research, Trinity College Dublin. Available online from: https://geofinresearch.eu/outputs/working-papers/.

- Sokol, M. 2020. From a pandemic to a global financial meltdown? Preliminary thoughts on the economic consequences of Covid-19. GEOFIN Blog #9. Available online from: https://geofinresearch.eu/blogs/geofin-blog-9-from-a-pandemic-to-a-global-financial-meltdown-preliminary-thoughts-on-the-economic-consequences-of-covid-19-by-martin-sokol/.

- Sokol, M. and Pataccini, L., 2020. Winners and losers in coronavirus times: financialisation, financial chains and emerging economic geographies of the covid-19 pandemic. Tijdschrift voor Economische en Sociale Geografie, 111 (3), 401–415.

- Sommers, J. and Woolfson, C., (eds.) 2014. The contradictions of Austerity: the socio-economic costs of the neoliberal Baltic model. Nueva York: Routledge.

- Sorensen, M. 2019. Estonia orders Danske Bank out after money-laundering scandal. New York Times, 20 February 2019. Available online from: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/02/20/business/danske-bank-estonia-money-laundering.html.