ABSTRACT

We develop a state capacity framework to account for different national responses to Covid-19. Our starting point is the influential idea that neoliberalism has a major role to play in state failure to control the pandemic. By implementing neoliberal reforms, states have ostensibly rendered themselves incapable of preventing or mitigating the viral outbreak. A focus on the British experience lends weight to this perspective. But when viewed in a comparative light, the picture is less straightforward. By comparing the British and Australian cases, we see a similar embrace of neoliberal reforms across the whole of government, yet with strikingly divergent outcomes. How can we account for this dramatic difference? To answer this question, we offer an enhanced state capacity framework to improve our understanding of diverse national responses to Covid-19. Our larger objective is to enrich the existing state capacity literature in two ways. First, we extend the existing state capacity framework by introducing a new category – salutary capacity – to encapsulate a state's ability to correct and counteract the course of a national health emergency. Second, we introduce the idea of political choice to emphasise the importance of agency in offsetting the institutional weaknesses associated with neoliberal reform.

Introduction

As many have observed, the Covid-19 pandemic has thrown up stark differences in national responses. Compare the highly effective early responses of Australia with the more faltering actions of the UK to stem the viral spread. Surprisingly, however, there are few systematic efforts to make sense of national differences. What we do have are many country-level observations that seek to explain poor performance by highlighting the absence of particular factors, such as trust (Fukuyama Citation2020), effective leadership (Tourish Citation2020), social cohesion (Lofredo Citation2020), and public sector capacity (Mazzucato and Kattel Citation2020). And in many national stories of poor performance, neoliberal state transformation is believed to play the central role. As a way of describing regulatory reforms since the 1980s (notably privatisation, outsourcing, deregulation) neoliberalism has emerged as the preferred way of accounting for governments’ missteps and failure to control the viral spread (Andrew et al. Citation2020, Bartholomeusz Citation2020, Denniss Citation2020, Hil Citation2020, Monbiot Citation2020, Petersen Citation2020, Rogers Citation2020). Through the lens of neoliberal state transformation (NST), commentators have sought to make sense of the UK's bungled efforts to contain the virus and its disastrous death toll (for example, McCormack and Jones Citation2020, Jones and Hameiri Citation2021).

According to the NST thesis, to explain Britain's poor response to the pandemic, one need look no further than the neoliberal regime of fragmented governance that has prevailed since the early 1980s:

The Covid-19 pandemic is not simply a public health crisis … more importantly, it is a crisis of a whole way of governing society. The shift to regulatory statehood and transnational governance has hollowed out the practical capacities needed to respond meaningfully to genuine threats to public welfare. (McCormack and Jones Citation2020, n.p.)

As a stand-alone case, the British experience appears, in part, to support the NST account. However, when examined in a comparative light, as a convincing explanation for the spread of Covid-19, the NST thesis falls short. To rigorously test this hypothesis, the choice of a comparative case study is all-important. If X is neoliberalism, the absence or limited nature of X in one case cannot prove its causal role in a case with X. Methodologically, therefore, it will not do to compare a neoliberally transformed state (for example Britain) with one that has only flirted with regulatory reforms (for example South Korea, Taiwan, Japan) – especially where there are compelling reasons to expect divergent performance (for example prior experience of SARS). Obviously, if the starting points are very different, one would anticipate different outcomes. By comparing Britain with South Korea for example, one could only reinforce rather than test one's preferred explanation. For an illustration of this problematic approach, see the recent study by Jones and Hameiri (Citation2021), which we discuss in more detail as our analysis proceeds. We agree that it is important to explore the ways in which neoliberal reforms might be implicated in pandemic performance. But to do this with any rigour would demand comparison between two neoliberal regimes. An effective test would be to compare states where neoliberal governance is well established, but where outcomes diverge – for example Britain and Australia.

This brings us to the first major weakness in the NST account of Covid-19: it is unable to explain variations between neoliberal regimes. Consider that, like many OECD countries, both the UK and Australia have wholeheartedly embraced neoliberal reforms. Yet Australia has done very well in containing the virus when compared with the UK, and indeed most other ‘neoliberal states’, not least the United States (US). Infection and death counts per capita, as at 12 July 2021, convey the picture: whereas the US recorded 104,305 infections and 1870 deaths per million population, and the UK 75,035 and 1882 respectively, the Australian tally was comparatively modest at 1205 and 35 (Worldometer Citation2021). Some attribute Australia's superior performance to its island status and ‘sparsely populated' territory (Jones and Hameiri Citation2021). However, as the British case reveals, not all islands exploit their natural advantage. Consider also that roughly half of Australia's approximately 26 million inhabitants (about the same as Taiwan) is clustered into three major cities, providing ample opportunity for viral spread. Indeed, historically, Australia has fared quite badly in epidemic control, tallying an estimated 15,000 deaths from the 1918 Spanish Flu, which infected 40 per cent of the population. Closer to our time, a 2014 pandemic preparedness plan projected that even with the most effective planning, Australia could expect more than 500,000 infections and 6500 deaths from a severe (that is, 1918-style) influenza outbreak (DOH Citation2014). More generally, we should be wary of assumptions that unquestioningly link population density and geography to pandemic performance (Hsu Citation2020).

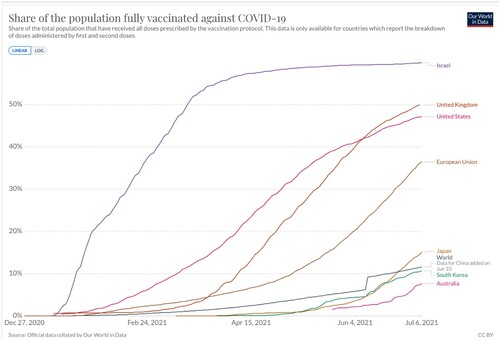

This brings us to the second major shortcoming of the approach in question. By positing a broad hollowing out and enfeeblement of the state's capacities, the NST account cannot make sense of a state's shifting performance over time.Footnote1 To wit, the highly effective vaccine rollout in Britain versus the woeful vaccine ‘strollout’ in Australia. As at 8 July 2021, the percentage of the British population fully vaccinated was 50.64, compared with a meagre 8.3 in Australia (Worldometer Citation2021).

Third, the NST account disregards the significance of agency (qua political choice), thus forgoing the opportunity to understand its remedial possibilities. A somewhat extreme expression of this disregard is the implication that NST operates as a decision-making ‘straitjacket' (Andrew et al. Citation2020), which means that ‘the system’ shapes policy decisions and outcomes, and agency is of little consequence. The words of Jones and Hameiri (Citation2021) exemplify this position:

(T)he British state failed spectacularly in 2020. This was not … simply a consequence of ministerial or prime ministerial incompetence, nor a function of the specific party in control at the time - the Conservatives … even if the Labour Party had won the 2019 elections, it would have inherited a regulatory state apparatus … (Jones and Hameiri Citation2021, p. 14)

It is hard to ignore the vastly different political choices which helped to produce starkly divergent outcomes among the neoliberal regimes of the UK, US, Australia, and New Zealand (NZ). On early border closure for example, the UK was an outlier, refusing to restrict entry until deep into the pandemic (Clark et al. Citation2020). It thereby forfeited the ‘island' advantage that Australian (and NZ) leaders exploited. In the US, President Trump chose to dispute the very existence of the virus while ridiculing and rejecting social distancing as infection and death rates soared. By contrast, the Australian and New Zealand leadership took heed of the unfolding tragedy and acted quickly to try to contain or (in NZ's case) to eliminate the virus.

In sum, the NST thesis has merit insofar as it highlights the ways in which regulatory reforms can weaken state capacities and expose a country to crisis. But its explanatory value is severely limited by its blindness to the different performance outcomes of neoliberally transformed states – and their shifting responses over time.

While we agree that states can be weakened by neoliberal reforms, and that weak state capacity can then be part of the story, we need a sharper instrument than the idea of NST to explain national variation in pandemic performance. Our framework provides an enhanced understanding of state capacity. It specifies the different aspects of capacity that matter to pandemic performance and explains how they may reinforce each other. It also clarifies the performance-shaping contribution of political choice and how it intersects with state capacity.

An Extended State Capacity Framework

To account for divergent national responses to the pandemic, it is productive to look beyond regime type (neoliberal or otherwise) and to start with the infrastructural power of the state, namely, the state's capacity to mobilise resources (whether human or material) on the basis of consent (see Mann Citation1984). When a community is faced with life and death issues – be it the threat of foreign invasion or a pandemic – the state's infrastructural power or capacity is critical. A state with infrastructural power has the capacity to mobilise people within its territory for a common project. Rather than a top-down exercise, state capacity is always enacted through, rather than over, society, by means of negotiation and consent. It exists independently of regime type and cannot be taken for granted – even in advanced democracies (Weiss and Thurbon Citation2018).

In normal times, state capacity can function fairly routinely through institutional arrangements that enable, at the very least, the extraction and (re-)distribution of resources. But in extraordinary times such as a pandemic, the capacity to respond to unforeseen challenges may not be forthcoming in the absence of goal-directed agency. Goal-directed agency opens a window onto the importance of political choice and its interaction with state capacity.

Our analysis enriches the existing body of work on state capacity in two ways. First, we extend the standard state capacity framework with the introduction of a fresh category – salutary capacity – to encapsulate a state's ability to counteract the course of a national health emergency. Second, we reaffirm the importance of political agency in state capacity analysis – in the tradition of agent-centred historical institutionalism (see for example Weiss and Thurbon Citation2004, Bell Citation2005, Citation2011, Bell and Feng Citation2014, Weiss Citation2014, Thurbon Citation2016a). Third, we identify three distinct ways in which political choice can intersect with state capacity to bolster weakened capacities in neoliberally transformed environments.

Pandemic Preparedness: Three Faces of State Capacity

In general, all modern states are endowed with a modicum of infrastructural power (see Mann Citation1984). However, their capacities for acting in different policy arenas are by no means similar. In recent decades, for example, America's prowess in radical innovation to preserve military superiority (Weiss Citation2014) has to be set against its dismal track record in providing for the nation's health (for example Dickman et al. Citation2017). By contrast, Australia has performed well in health provision (Our World in Data Citationn.d.) but scored poorly in promoting the nation's techno-industrial transformation (Thurbon Citation2016b).

So, as we would anticipate that, faced with the present health emergency, some countries would prove much better than others in managing the three related challenges of the pandemic: preventing/ suppressing or containing the viral spread; providing economic resources to support livelihoods during lockdown; and mobilising the domestic supply of medical equipment. Vaccinating the population is a critical chapter in this story, one we reserve for later discussion. While some countries appear to have performed well in meeting one or more of these challenges, notably Taiwan, Denmark, Germany, South Korea, Australia, and New Zealand, others have struggled on all three fronts, especially the US, UK, Italy, and Spain (see Thurbon and Weiss Citation2020).

In order to make sense of such different outcomes, we must start with two well-established sources of state capacity – extractive-distributive and transformative. Extractive-distributive capacity involves the ability of the state to mobilise economic resources for redistribution. Important in times of relative economic stability, this capacity becomes critical in times of crisis, when the threat of unemployment and bankruptcies would make lockdowns less socially viable. Transformative capacity refers to the ability of governing authorities to mobilise the business sector to foster industry and innovation in a way that promotes a country's shift up the industrial-technology ladder of development. In a pandemic, the dire shortages of everything from masks to ventilators in many jurisdictions can make this (transformative) capacity in the economic arena a matter of life and death.

Our previous research has had much to say about transformative and extractive capacity across a variety of national settings (Weiss and Hobson Citation1995, Weiss Citation1998, Weiss and Thurbon Citation2018). Current developments in the health arena, however, invite us to coin a new term – salutary capacity – to encompass the range of responses we currently observe cross-nationally. Consider that Taiwan, although living cheek by jowl with mainland China, has mobilised its pandemic preparedness in a way that has effectively contained the viral spread (Yeh and Cheng Citation2020). By contrast, and in spite of its massive wealth and technical sophistication, the US has struggled and failed to cope with the pandemic threat – at least until the vaccine rollout.

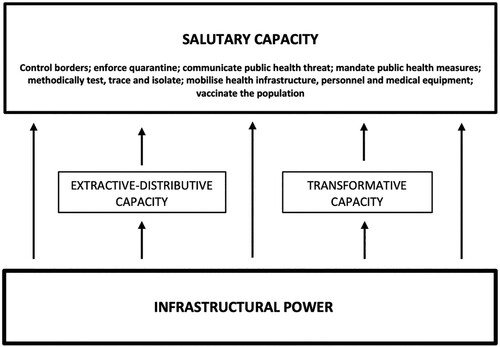

By salutary capacity, we refer to the state's ability to correct and counteract the course of a national health emergency. With reference to Covid-19, specific measures of salutary capacity include the ability to control national borders, to enforce quarantine, communicate a public health threat, mandate public health measures, methodically test, trace, and isolate, mobilise health infrastructure, personnel and medical equipment, and ultimately to vaccinate the population.

It must be emphasised that salutary capacity is not sui generis. In part, it depends on the state's prior extractive-distributive and transformative capacities. For example, the capacity to mobilise and distribute resources has proven essential to enable extended lockdowns that are critical to controlling the viral spread. Similarly, salutary capacity relies to some degree on the extent and sophistication of the nation's techno-industrial base. Although nonobvious, the ability to mobilise economic actors – transformative capacity – will have significant bearing on whether the country is faced with desperate shortages or greater self-sufficiency in medical supplies.

However, salutary capacity is not reducible to a state's extractive-distributive and transformative capacities. It refers to a cluster of capabilities that allow a country to correct and counteract the course of a health emergency (see ). Like transformative and extractive-distributive capacities, salutary capacity represents an outgrowth of a state's infrastructural power (see Weiss Citation2006, pp. 168–169). Even states with underdeveloped capacities in the extractive and transformative arenas can effectively develop some critical elements of salutary capacity – such as protecting borders, establishing testing and tracing regimes – when faced with a health emergency (think Vietnam, see Willoughby Citation2021) ().

Table 1: Three Faces of State Capacity for Pandemic Preparedness

We call attention to these three strands of state capacity in order to understand the divergent state responses that shape different outcomes for lives and livelihoods during a pandemic. However, state capacity is a necessary but not sufficient explanation for why some countries in the Anglosphere have fared better than others during the pandemic. Political choice, we contend, is a core element of the national responsiveness story. We use the term ‘political choice' as a proxy for the decisions of state agents, be they elected leaders, bureaucrats, or politically appointed advisors or programme leaders. Through a comparison of the British and Australian cases, we show how political choice matters to state capacity. First, the decisions of state agents can render institutional weaknesses less important than they might otherwise have been. Second, political decisions can help compensate for weaknesses by seeking out creative solutions to pressing problems. Third, political choice can enable dormant capacities to be activated. Fourth and finally, the decisions of political leaders can completely undermine an otherwise effective strategy and lead to a reversal of fortune.

Political Choice and State Capacity

Political choice can render institutional weaknesses more or less important

If there is a single act that can halt or hasten the spread of Covid-19, it is the early decision to close or leave open national borders. Early border closure is significant because it can minimise the spread of infection, limit the need for lockdowns, and give countries a buffer to get their contact tracing and testing systems in place. Border closure in Australia did not entirely prevent outbreaks or the need for a lockdown. Its major benefit was to contain the viral spread sufficiently to make tracing and testing effective (Duckett and Stobart Citation2020). Early action on borders also had enormous consequences for salutary capacity because it helped to curtail the viral spread and prevented the resource-constrained hospital system from being overwhelmed.

In both Australia and the UK, decades of neoliberal reform have significantly weakened their public health systems, potentially exposing them to the severest test of coping with a viral pandemic. In the UK, those weaknesses were starkly revealed when demand on the National Health System (NHS) threatened to overwhelm the capacity of health workers to properly treat the infected. Arguably the system only avoided being overwhelmed because non-Covid ‘patients deferred seeking help, in response to pleas to “protect the NHS”’ (Scobie Citation2021, see also Wingfield and Taegtmeyer Citation2021). In Australia, weakened capacities in the hospital system never took centre stage because of decisions taken in the initial phase of the global outbreak. Australia's institutional weaknesses in the healthcare sector were thereby rendered less important than they might otherwise have been.

So how do we account for these different choices? Is neoliberalism implicated, as the NST account insists?

The UK's failure to impose border (and quarantine) restrictions in a timely fashion has been attributed to a neoliberal system of governance in which critical decisions are ‘outsourced' to ‘unaccountable' scientific advisors who were following a neoliberally-inspired pandemic plan (McCormack and Jones Citation2020, n.p., Jones and Hameiri Citation2021, pp. 13–14). On this reading, the UK's 2011 Influenza Pandemic Preparedness Strategy is proferred as an instance of neoliberal regulatory governance that privileges the economy over lives. The Strategy, it is claimed, eschews border closure and other social restrictions during a pandemic in order to prioritise economic ‘business as usual’, regardless of the human cost. Moreover, by indicating that it is ‘appropriate’ for authorities to prepare logistically for a large death toll and the ethical rationing of medical resources, the Strategy is assumed to reflect a neoliberal ideology that puts the economy's health before people's (see Jones and Hameiri Citation2021, pp. 13–14).

A major flaw in this argument stems from its reliance on deductive logic rather than inductive theorising. This defect is manifest in two ways. First, there is scant evidence to support a neoliberal interpretation of the pandemic plan, whereas there is ample evidence to justify the counter argument elaborated here. So, if we look with two eyes rather than one, it is clear that Britain's influenza pandemic strategy was less a reflection of neoliberal ideology than of the prevailing scientific understanding of the efficacy of border closures for influenza pandemics. The 2011 Strategy document draws directly on international modelling of previous influenza outbreaks (DOH Citation2011). The findings, published in Nature, show that major border restrictions (say, 90 per cent) on international travel ‘are unlikely to delay spread by more than 2–3 weeks’ (Ferguson et al. Citation2006, p. 448).

It is telling that even Boris Johnson's fiercest critic and former advisor concedes in his 2021 testimony to the House of Commons that at the very critical stage when border decisions were first being taken and would have huge consequences (January–March 2020), economic concerns did not factor in the decision to keep the borders open:

It would not be fair to blame the Prime Minister for what happened before March [2020] … he was definitely not prioritising tourism … I heard him say specifically to the science advisors and the Department of Health, “Hang on, aren't a lot of people going to think we are mad for not closing the borders?” The Prime Minister did push on that in January/February, and it would be wrong and unfair to say that he prioritised the economy at that point. (Cummings in House of Commons Citation2021, Q1092)

In sum, we find little evidence to support the claim that Britain's 2011 Pandemic Preparedness Plan ‘prioritises economic ‘business as usual’’ (Jones and Hameiri, Citation2021, p. 14, emphasis added). Indeed, the Plan typically applies the term ‘business as usual’ to a variety of non-economic activities, and acts as a proxy for ‘going about one's normal daily life’. This is precisely how the term is deployed in the Plan on page 57, (rather than the exclusively economic connotation incorrectly attributed by Jones and Hameiri).

Moreover, even if we were to accept the NST claim that modern-day pandemic plans prioritise livelihoods over lives, it does not follow that leaders in neoliberal regimes must or will blindly follow them. This brings us to the third and final problem with the NST thesis: its deterministic reasoning. Its central assumption is that in a neoliberal regime, neither the competence of the leadership nor the nature of the party in power matter to the outcomes because the key choices are effectively determined by the regulatory state apparatus (‘the system’) (Jones and Hameiri Citation2021, p. 14).

It is here that a comparative analysis brings much-needed perspective. For in contrast to Britain, Australia's leaders took a decision completely ‘out of kilter with conventional wisdom’ that border closure was futile (B. Murphy cited in K. Murphy Citation2020). In the words of Australia's then Chief Medical Officer (CMO), Brendan Murphy:

The public health mantra, and the WHO has always said this … you don't ever close borders, that's not a helpful thing to do in a pandemic. When we took border measures, some of our colleagues in other countries questioned the value or the merit of doing it. It was out of kilter with conventional wisdom … We just decided whatever the public health mantra, we're not going to stick with it. (B. Murphy cited in K. Murphy Citation2020)

So to reiterate, these early decisions and actions taken on border closure have had large and significant impacts. Britain paid a heavy price for its delay in allowing a massive viral spread that rendered early testing and tracing impossible. While Britain's infection and death rates ballooned, Australia managed to contain the viral spread, giving it precious time to introduce an effective test and trace regime. This prevented system meltdown and largely concealed the institutional weaknesses in its own health sector that had been wrought by decades of neoliberal reform. In essence, Australia's hospital system was never tested like Britain's.

Thus, we argue that at the onset of a pandemic, it is the decisions political agents take – rather than state capacity per se – that most affect the scale and intensity of the health crisis. Consider this: If Australia had decided to follow the international (WHO) consensus at the time, there is every chance that its health system would have been completely overwhelmed – and given the state of cost-cutting in that sector, there is every chance that the NST account would then appear more plausible.

More generally, by tempering the significance of institutional weaknesses, political decisions become an important part of the pandemic performance story. In industrialised countries, those weaknesses may arise from decades of neoliberal reform. In less developed settings weak institutions may result from the long-standing lack of resources. Whatever the source of weakness, by intervening swiftly to block the viral spread, even countries with poorly resourced health systems can perform well (for example Vietnam, see Willoughby Citation2021).

Political decisions can help to compensate for institutional weaknesses by devising creative responses to pressing problems

In both Australia and the UK, governments resorted to ‘lockdowns’ as part of their pandemic management strategies – albeit for different reasons. In Australia, despite relatively few cases, the decision to lockdown was part of an early containment strategy (as it was in NZ, and most recently Taiwan [CDC Citation2021]). In the UK, the belated decision was a reaction to a runaway infection.Footnote3 Whether to prevent or remediate viral spread, lockdowns test the state's distributive capacity: people are unlikely to ‘shelter in place’ without some guarantee of income support (as the Indian case has revealed).

Both governments sought to mobilise and distribute vast sums to underpin their lockdown strategy. These economic support schemes were financed chiefly through the issue of government bonds, thus delaying the extractive challenge to a future date. In this early phase, the most pressing challenge was to find a distributive mechanism. However, decades of neoliberal reform had left the obvious distributive channel, vis-à-vis the social security system, unfit for purpose. So, when the crisis hit, these countries’ partially privatised, underfunded and understaffed social security mechanisms were unable to cope with overwhelming demand.

To stop their economies going into free fall, a wage subsidy programme was swiftly devised, drawing on the German example. Germany's hugely successful Kurzarbeit (short-work) scheme, in place since the 1920s, subsidises wages for workers furloughed due to lack of work in times of crisis (von der Leyen Citation2010). Germany's scheme, however, depends on a robust social security system, something that both the UK and Australian systems lacked. State actors in each case came up with a creative response: they sought to bypass the weakened distributive apparatus (that is, the social security system) and deliver social security payments through the much more robust extractive apparatus (the taxation system).Footnote4 In the words of the Australian PM:

We effectively privatised the social security system into corporate payrolls … That's exactly what we did. If we didn't roll out [the wage subsidy scheme through the tax office], all those people would have been on Centrelink [social security] queues within a day and the entire social security system would have collapsed under the strain. It was very important. (Morrison cited in Murphy Citation2020, p. 92)

Lest there be any confusion, we are not implying that Australia's and Britain's extractive systems are somehow exceptional. Most advanced countries have strong taxation systems. Rather, our claim is that in this time of crisis, state actors in both countries were able to compensate for the weaknesses in their distributive systems by creatively re-deploying their stronger ‘extractive’ institutions for ‘distributive’ purposes. Our broader point (made previously, and reiterated here) is that states are for the most part not unitary, being weak in some areas while strong in others.

Evidently, when faced with a crisis, political leaders in Australia and the UK have demonstrated that they can meet major distributive challenges, if they so choose. Leaders in both settings have been willing to turn on the financial spigot and have enjoyed the institutional capacity to execute their spending plans. While the state’s willingness to spend may seem inconsistent with neoliberal thinking, one might object that it is merely a temporary measure designed to deal with an emergency situation. This is precisely how the Australian government framed its income support schemes, insisting that they would ‘snap back' when the pandemic was under control (see Murphy Citation2020). Whether or not such schemes are short-lived is not the issue. The state capacity test has been met and in the distributive arena, at least, the NST idea of a state severely constrained by regulatory overhaul is found wanting.

Political choice can enable dormant capacities to be activated

Weak performance in the salutary arena increases the burden on the health system and the demand for health equipment. To the extent that global supply chains fail and local supply is limited or unavailable, the state's transformative capacity will be tested. This was the British experience. The Covid crisis created enormous demand for medical supplies, ranging from sophisticated machinery (invasive ventilators) to protective masks. The British government's tardiness in closing the borders – allowing the virus to spread unchecked – contributed to supply constraints. As the demand for ventilators soared, Whitehall realised that it would have to meet urgent demand through domestic production. But years of deindustrialisation and reliance on foreign supply chains meant that domestic producers of the needed equipment were virtually non-existent.

For some, this ‘hollowing out' of industrial capacity is another indicator of the state's neoliberal transformation (McCormack and Jones Citation2020, n.p.). From the NST perspective, any effort to plug production-related gaps is likely to fail, for three reasons. First, state actors ostensibly lack the willingness and ability to coordinate domestic firms to meet critical needs. Second, domestic industrial capacity would have withered to such a degree that there are few if any relevant firms left to mobilise for a national project. Third, the corrosion of regulatory oversight has politicised public procurement (NAO Citation2020b).

Leaving aside the procurement issue which in this context has scarce relevance for transformative capacity, we assess the extent to which Britain's ability to mobilise and coordinate the needed industrial capabilities has withered beyond repair. Their techno-industrial sophistication meant that ventilator shortages provided the most serious test of transformative capacity.

We find that state actors moved swiftly to address the impending crisis, in mid-March issuing a formal ‘call to arms’ known as the Ventilator Challenge. In a phone call with over 100 of the country's leading industrial firms and industry-related government agencies, the head of the Cabinet Office called on industry to meet the urgent demand for ventilator equipment, by either scaling up production of existing designs or creating entirely new products. This programme enjoyed some success through a consortium that focused on adapting and scaling up existing designs. It also benefited from a programme champion (CEO Dick Elsy) embedded in one of the British state's own innovation networks – the High Value Manufacturing Catapult.Footnote6 To create the consortium, Elsy drew on the network of firms already in the Catapult orbit (Excell Citation2020, n.p.), which eventually included 33 UK engineering firms spanning the aerospace, automotive, motorsport, and medical sectors. By early July, the consortium had more than doubled the stock available to the NHS. Specifically, it had: scaled-up production of the Penlon ESO 2 Emergency Ventilator device; established from scratch seven new large-scale manufacturing facilities in the UK, as well as restructuring existing sites; achieved peak production in excess of 400 devices a day; set up new parallel supply chains and acquired around 42 million parts and electronic components through a complex logistics network that saw an end-to-end supply chain in only 1.5 weeks; sourced parts from over 22 countries, despite global competition for the same; achieved full MHRA approval for the Penlon ventilator in just three weeks; recruited and trained a 3500 strong front-line assembly team; and delivered almost 13,500 ventilators to the NHS (Royal Academy of Engineering Citation2020). By the time the crisis eased in July 2020, the number of ventilators available to the NHS had climbed to 25,000 (just short of the June target of 30,000). Only 2500 of these had been sourced from overseas, while 14,000 had been produced domestically under the Ventilator Challenge. A National Audit Office review of the Challenge reported effective programme management, resulting in spare capacity should it be needed (NAO Citation2020a).Footnote7 The Ventilator Challenge UK may thus be considered at the very least a modest achievement, not the abject failure sometimes depicted in early media coverage (for example, Stone Citation2020).

Like the UK, Australia had experienced decades of industrial decline and was almost entirely reliant upon imports of manufactured medical supplies, from the most basic to the more sophisticated.Footnote8 However, in contrast to Britain, Australia's early efforts to contain the virus meant that it never experienced a ventilator shortage. This meant that its transformative capacity was never put to the test. Nevertheless, anticipating the worst, Canberra sought to mobilise domestic firms to preempt a shortage. In April 2020, the federal government implemented the NOTUS Emergency Invasive Ventilator Program, coordinated by the Advanced Manufacturing Growth Centre. The local company, Grey Innovation, was selected to produce ventilators in collaboration with a network of local suppliers and universities. By August, the Grey consortium had delivered 2000 ventilators to the federal government, and a further 2000 to the Victorian Government, which by that stage was grappling with a second wave.

Recent government action can hardly compensate for years of industrial decline, which might lead somehow to a rebirth of industrial dynamism. Our claim is more modest. In addressing the challenges of a national health emergency by producing the ventilators needed, both the Australian and UK governments activated transformative capacities that had lain dormant.

Political choice can effect a reversal of fortune

It might seem that Australia gets a good report card while the UK gets sent to the bottom of the class when handling a pandemic. But this is an evolving story and the conclusion is some way in the future. If we pursue this metaphor, consider the most recent chapter on vaccinating the population – a core aspect of salutary capacity. At the time of writing, in this phase of the story, we see the fortunes of the UK and Australia being completely reversed. By early July 2021, the UK had fully vaccinated approximately 50 per cent of its population, compared with less than 10 per cent in Australia. Weak vaccination rates have left Australia vulnerable to newer, more infectious and dangerous strains of the virus (notably Delta). By July 2021, a long period of near-normalcy came to an abrupt halt, first with the re-institution of lockdowns in Australia's most populous state, New South Wales, followed by several lockdowns across the nation.

How do we account for Australia's recent reversal of fortune? What on the surface may appear to be a case of bad luck boils down to some very poor political decisions, notably in the two areas for which the federal government is most responsible: quarantine and vaccines.

Despite border closure, repeated breaches of quarantine have starkly illustrated the abdication of national leadership, as the PM sought to shift federal responsibility for quarantine to state authorities. Under the 2015 Biosecurity Act, Morrison as PM had the power to implement a national quarantine system. By vigorously resisting state government appeals and choosing not to exercise his power, PM Morrison sought to avoid responsibility for any leaks and viral outbreaks (Williams Citation2020). The hotel-based quarantine system that emerged to fill the void was not fit for purpose and produced regular outbreaks that escaped into the community. Prior to June 2021, state governments became adept at ‘mopping up’ outbreaks via rapid contact tracing and testing and the occasional short-term lockdown. During this period, federal abdication of responsibility mattered less. But this would change dramatically with the emergence of new viral strains like Delta. In this respect, the Australian government's decision to renounce responsibility for quarantine is now threatening to reverse the country’s hitherto strong pandemic performance. Add to this situation a largely unvaccinated population and we have a recipe for a Delta disaster ().

Figure 2. Share of Population fully vaccinated against COVID-19. Source: https://ourworldindata.org/covid-vaccinations (Accessed 8 July 2021).

In 2020, Australia made what seemed a logical decision to rely on vaccines that could be produced domestically, either under licence (AstraZeneca (AZ)) or by using an entirely home-grown technology (i.e. the University of Queensland-CSL vaccine). In December 2020, this strategy was rendered risky by a stroke of bad luck; while the UQ vaccine proved both safe and efficacious in phase one trials, it also produced an immune response that would create false positives for HIV, leading to the trial's abandonment. Despite this setback, effective suppression of the virus created the perception that there was time to wait for the local scale-up of the AZ vaccine (Kampmark Citation2021). But this strategy too was thrown into chaos with the emergence of blood clots in the under 50s; on health advice this ruled out the AZ option for large segments of the population, thus creating a major supply shortage.Footnote9 The country's dangerously low rate of vaccination was compounded by the outbreak of the Delta variant in June 2021, creating a new sense of urgency that increased the demand for vaccination.

While grossly inadequate supply has slowed the ramp-up rate of vaccination, so too has the chaotic approach to phasing, and the failure to implement a logistical system capable of delivering vaccines to the right place at the right time (Buckland et al. Citation2021, Jackson and Curran Citation2021). Instead of establishing mass vaccination centres – as called for by State governments – the federal government proposed to rely principally on the country’s network of GPs, a strategy unsustainable for mass immunisation (Duckett Citation2021). Finally, a marked lack of transparency and poor communications strategy has undermined the roll-out and fuelled vaccine hesitancy on the part of the public.

Turning to the British experience, we see what is virtually the mirror image of Australia's. In almost every aspect the choices have been starkly different. As early as May 2020, at the behest of the nation’s Chief Scientific Advisor, the UK established a vaccine task force in the Department of Business, Energy, and Industrial Strategy. Under the leadership of biotech venture capitalist Kate Bingham, the taskforce quickly moved to secure early contracts for the supply of multiple vaccines. It also worked closely with the NHS to recruit trial participants, test vaccine efficacy and progress swift vaccine approval. With supply secured, the NHS – under the leadership of Sir Simon Stevens – was charged with designing and executing the vaccine roll-out, drawing on substantial support from the army's 101 Logistics Brigade, under the command of Brigadier Phil Prosser (Baraniuk Citation2021, Bingham Citation2021, Neville and Warrell Citation2021, Sasse Citation2021).

What is especially striking about the UK's vaccine story is that these highly effective strategies took place in tandem with Britain's bungled attempts to control the viral outbreak. Since states are not unitary, the manifestation of their different strengths and weaknesses should not surprise. The broader analytical point to note is that where we see a particular strength, it is often due in no small part to the role of highly effective, goal-driven agents who take ownership of a programme and are able to manipulate existing institutional constraints in order to achieve their objectives. Most generally, we would note that the pivotal role of the NHS in the vaccine roll-out is at odds with the image of a health-system debilitated by NST reform.

We enter a note of caution here because Britain's reversal of fortune may be about to be reversed, yet again – this time in a less than positive direction. In July 2021, PM Johnson stated his intention to remove all COVID-based restrictions – mask-wearing, social distancing, mass-gathering limitations included – in the middle of a Delta outbreak and while half the population remain un- or under-vaccinated. This potentially self-harming action – described as ‘surrendering to COVID’ – threatens to unleash a new round of infections, hospitalisations, and ICU admissions. Should that decision play out as many now anticipate (Kleczkowski Citation2021, Mellor Citation2021), we could have no better reminder of the importance of agency in a story of institutional strengths and weaknesses.

Conclusion

We set out to understand why Australia and the UK have fared so differently during the Covid crisis. According to an influential view, NST is largely responsible for the spread of Covid because it has undermined state capacity. Why, then, despite embracing similar neoliberal reforms, has Australia performed significantly better than the UK (above all in the health arena)? To answer this question, we extend the classical state capacity framework, introducing the category of salutary capacity, and bringing state agents and their choices into the analysis. When faced with a national health emergency, we have shown that political choice matters for four reasons. First, the decisions of political agents can render institutional weaknesses less important than they might otherwise have been. Second, political decisions can help compensate for weaknesses by seeking out creative solutions to pressing problems. Third, political choice can enable dormant capacities to be activated. Fourth and finally, the decisions of political leaders can completely undermine an otherwise effective strategy and lead to a reversal of fortune.

As our analysis shows, states are not unitary. Rather than uniformly strong or weak, their capacities vary across different domains, and over time. Britain's strengths in the distributive arena were not reflected in the salutary space (though highly qualified by the effective vaccine rollout). Australia, by contrast, initially excelled in both the distributive and salutary arenas, but has since faltered badly in quarantine and vaccination. These differences should caution us against adopting a blunt instrument like NST to understand government responses to the Covid crisis. Our objective in this paper is not to draw firm conclusions about how this pandemic will play out in the UK and Australia, but rather to provide a framework for understanding diverse national responses and demonstrate how we might go about investigating the presence or absence of key aspects of state capacity.

Our argument is not that neoliberal reforms do not matter; they can and do clearly create vulnerabilities. But these vulnerabilities are not written in concrete. As our analysis shows, they can be reversed, sometimes surprisingly swiftly. We conclude that such reversal depends on political choice, which is why we see agents and their decisions as an important variable in the state capacity equation.

In sum, there is no question that cost-cutting, privatisation, and poor regulatory oversight can have dire consequences. But we find it unnecessary to invoke the abstraction of neoliberalism (‘the system’) when the failure of leadership and political choice would appear more accurate. To invoke neoliberalism too liberally as the cause of Covid woes, would be to blunt its explanatory value – and to let political leaders and decision-making authorities off the hook.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Caitlin Biddolph for her outstanding research assistance and two anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments on earlier versions of this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Linda Weiss

Linda Weiss is a Fellow of the Academy of the Social Sciences in Australia, Professor Emeritus in Government and International Relations at the University of Sydney, and Honorary Professor of Political Science at Aarhus University. She has taught and lectured widely in Europe, Asia, and the Americas. Her specialism is the comparative and international politics of high technology and economic development, with a focus on state capacity and public-private sector relations. Many of her books and articles have been published in foreign language translations.

Elizabeth Thurbon

Elizabeth Thurbon is a Scientia Fellow and Associate Professor of International Political Economy at the School of Social Sciences, UNSW Sydney and an Australia-Korea Foundation Fellow at The Asia Society. Her research specialism is the political–economy of technoindustrial development and change, with a focus on the strategic role of the state. Her recent works include Developmental Mindset: The Revival of Financial Activism in South Korea (Cornell University Press).

Notes

1 A further problem for the NST thesis is to account for varied performance within federally organised neoliberal states. Consider the Australian case: in the health arena, we find varied performance across different sub—national (read: ‘state government’) jurisdictions. In the matters of quarantine, aged care, and testing and tracing, we find strikingly different approaches and outcomes despite being subject to neoliberal regulatory reform. This is an important complication for the NST thesis that we must address in a separate study.

2 For example, a recent review of European pandemic plans revealed that 19 out of 29 nations addressed the ethical questions associated with resource rationing (Droogers et al. Citation2019).

3 Although both countries began to introduce lockdown measures at around the same time (March 23 2020), the UK did so at a much later point in its rising infection curve (i.e, at 6,600+ cases compared with Australia's approx. 1,800), hence a ‘belated’ response. The UK's decision to keep borders open and eschew meaningful quarantine also compromised the effectiveness of its lockdown.

4 While the primary purpose of the taxation system is extractive, there are cases in which the tax office can distrubiute payment as well (such as tax refunds). For details of the UK scheme see HM Treasury (Citation2020). For the Australian scheme see Australian Government Treasury (Citation2021).

5 Beyond this, recipients of social security already in the system in both countries received a temporary boost to their benefits.

6 The government's innovation agency Innovate UK had established the Catapults in 2011. The aim: to bring public and private actors together to commercialise and scale technologies in strategically important sectors. See Catapult Network (Citation2021).

7 Procurement of PPE was a different story – attempts to source from local firms turned out to be politicised and costly (Sanchez-Graells Citation2020). As a result, compared with the Ventilator Challenge, it received a very different – indeed damning – evaluation from the NAO (Citation2020b).

8 A notable exception being Australia's biopharmaceutical giant CSL, which has produced a number of world-leading pharmaceutical solutions, including a range of vaccines (AAMC Citation2016).

9 -Australia turned to the US for Pfizer but faced export blockages.

References

- Andrew, J., et al., 2020. Australia's covid-19 public budgeting response: the straitjacket of neoliberalism. Journal of public budgeting, accounting & financial management, 32 (5), 759–70.

- Australian Advanced Manufacturing Council. 2016. CSL celebrates 100 year history. Available from: https://www.aamc.org.au/csl-celebrates-100-year-history/ [Accessed 14/07/2021].

- Australian Government Treasury. 2021. Economic response to the coronavirus: supporting individuals and households. Available from: https://treasury.gov.au/coronavirus/households [Accessed 10/05/2021].

- Batholomeusz, J., 2020, May 27. The pandemic that exposed British neoliberalism. Heinrich Böll Stiftung. Available from: https://eu.boell.org/en/2020/05/27/pandemic-exposed-british-neoliberalism [Accessed 09/02/2021].

- Baraniuk, C., 2021. Covid-19: how the UK vaccine rollout delivered success so far. British medical journal, 372 (n421), Available from: https://www.bmj.com/content/372/bmj.n421 [Accessed 23/06/2021].

- Bell, S., 2005. How tight are the policy constraints? The policy convergence thesis, institutionally situated actors and expansionary monetary policy in Australia. New political economy, 10 (1), 65–89.

- Bell, S., 2011. Do we really need a new ‘constructivist institutionalism' to explain institutional change? British journal of political science, 41 (4), 883–906.

- Bell, S., and Feng, H., 2014. How proximate and ‘meta-institutional' contexts shape institutional change: Explaining the rise of the people‘s bank of China. Political studies, 62 (1), 197–215.

- Bingham, K., 2021. The UK government's vaccine taskforce: strategy for protecting the UK and the world. The Lancet, 397 (10268), 68–70.

- Buckland, M., Zerbib, F., and Wherrett, C., 2021. Insights report: counting the cost of Australia's delayed vaccine roll-out. The McKell Institute. Available from: https://mckellinstitute.org.au/wp-content/uploads/McKell-The-Cost-of-Australias-Delayed-Vaccine-Rollout.pdf [Accessed 09/07/2021].

- Catapult Network. 2021. Catapult Network. Available from: https://catapult.org.uk/ [Accessed 08/06/2021].

- Centers for Disease Control Taiwan (CDC). 2021. Nationwide Level 3 epidemic alert extended to June 28; related measures remain effective to fight against COVID-19 in community. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov.tw/En/Bulletin/Detail/uIsfZpLbzqQ_uBK71xZ8Xg?typeid=158 [Accessed 14 July 2021].

- Clark, P., et al. 2020. Britain's open borders make it a global outlier in coronavirus fight. Financial Times, 17 April. Available from: https://www.ft.com/content/91dea18f-ad0e-4dcb-98c3-de836b1ba79b [Accessed 08/10/2020].

- Dennis, R. 2020. The spread of coronavirus in Australia is not the fault of individuals but a result of neoliberalism. The Guardian, 20 August. Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/aug/20/the-spread-of-coronavirus-is-not-the-fault-of-individuals-but-a-result-of-neoliberalism [Accessed 06/03/2021].

- Department of Health (DoH), 2011. UK influenza pandemic preparedness strategy 2011. London: DoH. Available from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/213717/dh_131040.pdf [Accessed 05/03/2021].

- Department of Health (DOH), 2014. Victorian health management plan for pandemic influenza. Victoria: Department of Health. Available from: https://www2.health.vic.gov.au/about/publications/policiesandguidelines/Victorian-healthmanagement-plan-for-pandemic-influenza—October-2014 [Accessed 09/08/2020].

- Dickman, S.L., Himmelstein, D.U., and Woolhandler, S., 2017. Inequality and the health-care system in the USA. The Lancet, 389 (10077), 1431–41.

- Droogers, M., et al., 2019. European pandemic influenza preparedness planning: a review of national plans. Disaster medicine and public health preparedness, 13 (3), 582–92.

- Duckett, S. 2021. 4 ways Australia's COVID vaccine rollout has been bungled. The Conversation, 1 April. Available from: https://theconversation.com/4-ways-australias-covid-vaccine-rollout-has-been-bungled-158225 [Accessed 02/06/2021].

- Duckett, S., and Stobart, A. 2020. 4 ways Australia's coronavirus response was a triumph, and 4 ways it fell short. The Conversation, 4 June. Available from: https://theconversation.com/4-ways-australias-coronavirus-response-was-a-triumph-and-4-ways-it-fell-short-139845 [Accessed 12/07/2021].

- Excell, J. 2020. Interview: Dick Elsy on leading the Ventilator Challenge UK consortium. The Engineer, 22 May. Available from: https://www.theengineer.co.uk/dick-elsy-ventilator-challenge-uk/ [Accessed 03/03/2021].

- Ferguson, N., et al., 2006. Strategies for mitigating an influenza pandemic. Nature, 442, 448–52. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1038/nature04795 [Accessed 06/07/2021].

- Fukuyama, F. 2020. The thing that determines a country's resistance to the coronavirus. The Atlantic, 30 March. Available from: https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2020/03/thing-determines-how-well-countries-respond-coronavirus/609025/ [Accessed 02/03/2021].

- Hil, R. 2020. Rewilding capitalism: Covid-19 and the rebooting of Australia's neoliberal order. Arena, 20 August. Available from: https://arena.org.au/rewilding-capitalism-Covid-19-and-the-rebooting-of-australias-neoliberal-order/ [Accessed 03/03/2021].

- HM Treasury. 2020. Chancellor extends self-employment support scheme and confirms furlough next steps. Press Release. 29 May. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/chancellor-extends-self-employment-support-scheme-and-confirms-furlough-next-steps [Accessed 06/03/2021].

- House of Commons. 2021. Oral evidence: Coronavirus: lessons learnt, HC 95. Health and Social Care Committee and Science and Technology Committee. 26 May. Available from: https://committees.parliament.uk/oralevidence/2249/html/ [Accessed: 06/06/2021].

- Hsu, J. 2020. Population density does not doom cities to pandemic dangers. Scientific American, 16 September. Available from: https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/population-density-does-not-doom-cities-to-pandemic-dangers/ [Accessed 03/03/2021].

- Institute of Medicine (IOM), 2007. Ethical and legal considerations in mitigating pandemic disease, workshop summary. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

- Jackson, E., and Curran, S. 2021. Australia's COVID vaccine rollout is well behind schedule –but don't panic. The Conversation, 16 May. Available from: https://theconversation.com/australias-covid-vaccine-rollout-is-well-behind-schedule-but-dont-panic-157048 [Accessed 07/06/2021].

- Jones, L., and Hameiri, S., 2021. COVID-19 and the failure of the neoliberal regulatory state. Review of international political economy, 1–25. doi:10.1080/09692290.2021.1892798. [Accessed 06/03/2021].

- Kampmark, B. 2021. Nimble failure: The Australian COVID-19 vaccination program. International Policy Digest, 11 April. Available from: https://intpolicydigest.org/nimble-failure-the-australian-covid-19-vaccination-program/ [Accessed 04/06/2021].

- Kelckzkowski, A. 2021. UK COVID cases have fallen dramatically – but another wave is likely. The Conversation. Available from: https://theconversation.com/uk-covid-cases-have-fallen-dramatically-but-another-wave-is-likely-165553. 17 August. [Accessed 01/09/2021].

- Kotalik, J. 2006. Ethics of planning for and responding to pandemic influenza. Swiss National Advisory Commission on Biomedical Ethics. Available from: https://www.nek-cne.admin.ch/inhalte/Externe_Gutachten/gutachten_kotalik_en.pdf [Accessed 09/06/2021].

- Lofredo, M., 2020. Social cohesion, trust and government action against pandemics. Eubios journal of Asian and international bioethics, 30 (5).

- Mann, M., 1984. The autonomous power of the state: its origins, mechanisms and results. European journal of sociology, 25 (2), 185–213.

- Mazzucato, M., and Kattel, R., 2020. COVID-19 and public-sector capacity. Oxford review of economic policy, 36 (Supplement 1), S256–69. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/oxrep/article/36/Supplement_1/S256/5899016 [Accessed 04/03/2021].

- McCormack, T., and Jones, L. 2020. After Brexit #3: Covid-19 and the failed post-political state. The Full Brexit: For Popular Sovereignty, Democracy, and Economic Renewal, 17 April. Available from: https://www.thefullbrexit.com/Covid19-state-failure [Accessed: 03/03/2021].

- Mellor, Sophie. 2021. School year hangs in the balance as COVID-19 cases spike in the U.K. Fortune. 27 August https://fortune.com/2021/08/26/school-year-covid-19-cases-spike-uk-england-scotland-delta-variant/ [Accessed 01/09/21].

- Monbiot, G. 2020. Tory privatisation is at the heart of the UK's disastrous coronavirus response. The Guardian, 27 May. Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/may/27/privatisation-uk-disatrous-coronavirus-response-ppe-care-homes-corporate-power-public-policy [Accessed: 03/03/2021].

- Murphy, K., 2020. The end of certainty: scott Morrison and pandemic politics. Quarterly essay (79).

- National Audit Office (NAO). 2020a. Investigation into how government increased the number of ventilators available to the NHS in response to Covid-19. UK National Audit Office, 30 September. Available from: https://www.nao.org.uk/report/increasing-ventilator-capacity-in-response-to-Covid-19/ [Accessed 05/03/2021].

- National Audit Office (NAO). 2020b. Investigation into government procurement during the Covid-19 pandemic. UK National Audit Office, 26 November. Available from: https://www.nao.org.uk/report/government-procurement-during-the-Covid-19-pandemic/[Accessed 05/03/2021].

- Neville, S., and Warrell, H. 2021. UK vaccine rollout success built on NHS determination and military precision. Financial Times, 13 February. Available from: https://www.ft.com/content/cd66ae57-657e-4579-be19-85efcfa5d09b [Accessed 06/06/2021].

- Our World in Data. n.d. Healthcare access and quality index, 1990 to 2015. Our World in Data. Available from: https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/healthcare-access-and-quality-index?tab=chart&country=~AUS [Accessed 05/03/2021].

- Petersen, A. 2020. Covid-19: making sense of the social responses. Lens, Monash University, 19 March. Available from: https://lens.monash.edu/@politics-society/2020/03/19/1379851/making-sense-of-social-responses-to-Covid-19 [Accessed 03/03/2021].

- Rogers, P. 2020. Coronavirus could dethrone the neoliberalism that's made the UK a basket case. openDemocracy, 21 August. Available from: https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/opendemocracyuk/coronavirus-could-dethrone-the-neoliberalism-thats-made-the-uk-a-basket-case/.

- Royal Academy of Engineering. 2020. Incredible consortium's 13,400+ ventilators helped save the NHS from a shortage. Available from: https://www.raeng.org.uk/grants-prizes/prizes/prizes-and-medals/awards/presidents-special-awards-pandemic-service/consortium-ventilators [Accessed 03/03/2021].

- Sancehez-Graells, A. 2020. Procurement and commissioning during COVID-19: Reflections and (early) lessons. Northern Ireland Legal Quarterly. Available from: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3709746 [Accessed 03/03/2021].

- Sasse, T. 2021. Coronavirus vaccine rollout. Institute for Government, 18 May. Available from: https://www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/explainers/coronavirus-vaccine-rollout [Accessed: 06/07/2021].

- Scobie, S. 2021. Will the Third Covid-19 Wave Overwhelm the NHS? Nuffield Trust. 26 August. https://www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/news-item/will-the-third-covid-19-wave-overwhelm-the-nhs. [Accessed 01/09/2021].

- Stone, J. 2020. Boris Johnson's ‘ventilator challenge' delivered just 4% increase in machines before coronavirus peak. Independent, 20 May. Available from: https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/politics/boris-johnson-coronavirus-ventilator-challenge-machines-nhs-uk-cases-a9522886.html [Accessed: 06/07/2021].

- Thurbon, E., 2016a. Developmental mindset: the revival of financial activism in Taiwan. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Thurbon, E., 2016b. Trade agreements and the myth of policy constraint in Australia. Australian journal of political science, 51 (4), 636–51.

- Thurbon, E., and Weiss, L. 2020. Why some advanced countries fail to deal with Covid-19. East Asia Forum, 7 May. Available from: https://www.eastasiaforum.org/2020/05/07/why-some-advanced-countries-fail-to-deal-with-Covid-19/ [Accessed 03/03/2021].

- Tourish, D., 2020. Introduction to the special issue: why the coronavirus crisis is also a crisis of leadership. Leadership, 16 (3), doi:10.1177/1742715020929242. [Accessed 03/03/2021].

- von der Leyen, U., 2010. Keeping Germany at work. Organisation for economic cooperation and development. The OECD observer (280), 9.

- Weiss, L., 1998. Myth of the powerless state. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Weiss, L., 2006. Infrastructural power, economic transformation, and globalization. In: J.A. Hall and R. Schroeder, eds. An anatomy of power: the social theory of Michael Mann. Cambridge University Press, 167–86.

- Weiss, L., 2014. America inc.? Innovation and enterprise in the national security state. Cornell University Press.

- Weiss, L., and Hobson, J.M., 1995. States and economic development: a comparative historical analysis. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Weiss, L., and Thurbon, E., 2004. Where there's a will there's a way: governing the market in times of uncertainty. Issues and studies, 40 (1), 61–72.

- Weiss, L., and Thurbon, E., 2018. Power paradox: how the extension of US infrastructural power abroad diminishes state capacity at home. Review of international political economy, 25 (6), 779–810.

- Williams, G. 2020. PM has the upper hand on border closures. The Australian. 31 August.

- Willoughby, E. 2021. An ideal public health model? Vietnam's state-led, preventative, low-cost response to COVID-19. Brookings, 29 June. Available from: https://www.brookings.edu/blog/order-from-chaos/2021/06/29/an-ideal-public-health-model-vietnams-state-led-preventative-low-cost-response-to-covid-19/ [Accessed 12 July 2021].

- Wingfield, T., and Taegtmeyer, M. 2021. Healthcare workers and coronavirus: behind the stiff upper lip we are highly vulnerable. The Conversation. 8 April 2020. https://theconversation.com/healthcare-workers-and-coronavirus-behind-the-stiff-upper-lip-we-are-highly-vulnerable-133864 [Accessed 1 September 2021].

- Worldometer. 2021. Covid-19 coronavirus pandemic. Available from: https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/#countries [Accessed 12 July 2021].

- Yeh, M.J., and Cheng, Y., 2020. Policies tackling the COVID-19 pandemic: A sociopolitical perspective from Taiwan. Health security, 18 (6), 427–34.