?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

We build upon the Minskyan concepts of ‘thwarting mechanisms’ and ‘supercycles’ to develop a framework for analysing the dynamic evolutionary interactions between macrofinancial, institutional and political processes. Thwarting mechanisms are institutional structures that aim to stabilise the macrofinancial system. The effectiveness of these structures changes over time as a result of profit-seeking innovations and long-run destabilising processes. New institutional structures emerge in response, influenced by political and ideological conflicts. This generates a secular cyclical pattern in capitalism, the ‘supercycle’, with a longer duration than standard business and financial cycles. To illustrate this, we develop a macrofinancial stability index which we use to identify two supercycles in the G7 countries in the post-war period. We label these the industrial capitalism supercycle and the financial globalisation supercycle. For each, we apply a four-phase classification system, based on the effectiveness of institutions, customs and political structures for stabilising the macrofinancial system. The supercycles framework can be used to explain and anticipate macro financial and thus political developments, and moves beyond approaches in which these developments are treated as exogenous shocks.

Introduction

Institutional change is a central feature of capitalism. Recent decades have seen growing interest in the study of institutions (Williamson Citation1998, Hall and Soskice Citation2001, Blyth Citation2002, Acemoglu et al. Citation2005, Hodgson Citation2015, North Citation2018), but a comprehensive theory of institutional change in contemporary capitalism remains elusive. Economics and related disciplines have largely focused on unidirectional accounts in which particular institutional formations promote growth and stability. Yet institutional structure is also driven by economic events. Turbulent macroeconomic and financial processes drive changes in labour market institutions, systems of macroeconomic management and financial regulation. Financial globalisation leaves governments increasingly beholden to international forces (Rey Citation2015). Institutional change alters the balance of power between labour, capital and rentiers which, in turn, influences macroeconomic outcomes (Kalecki Citation1943, Baccaro and Pontusson Citation2016).

With notable exceptions (Aglietta Citation1979, Boyer Citation2000, Jessop and Sum Citation2006, Gabor Citation2020), the political economy literature tends to treat institutional change as if it were driven by exogenous macroeconomic or financial shocks, such as shifts in inflation or the policy interest rate. Conversely, macrofinancial developments are typically explained as arising from exogenous institutional change, such as alterations to financial regulation or labour market legislation.

In this paper, we develop an evolutionary framework that connects both macroeconomic and financial processes with institutional change. Following Palley (Citation2011) and extensions in the Regulation School tradition (Guttmann Citation2016), we use two largely overlooked concepts in Minsky’s analysis of financial capitalism to explain cyclical historical patterns of institutional effectiveness and macrofinancial stability. The first, ‘thwarting mechanisms’, reflects Minsky’s insight that although capitalism is inherently unstable, this instability rarely becomes explosive because of the existence of ‘customs, institutions or policy interventions’ that tame destabilising forces (Ferri and Minsky Citation1992, p. 84). Thwarting mechanisms counteract the inherent instability of capitalism, allowing for long periods of high economic activity and social and financial stability.

However, the effectiveness of thwarting mechanisms varies over time and is weakened by the profit-seeking actions of economic agents. This endogenous erosion introduces new sources of long-run instability and crisis, which, in turn, lead to the development of new thwarting mechanisms. The rise and fall of thwarting mechanisms generates a secular cycle in macrofinancial stability. This ‘supercycle’ is the second concept we borrow from Minsky and Palley.

Building upon these Minskyan concepts we (i) develop a novel classification of institutions based on their stabilisation capacities, (ii) explicitly introduce long-run cycle phases into a periodisation of capitalism, (iii) develop an index that captures macrofinancial stability and (iv) analyse the dynamic macroeconomic role of shadow banking using a critical macro-finance approach (Gabor Citation2020).

We proceed as follows. We first introduce our theoretical supercycles framework and present an index of macrofinancial stability that we apply to G7 countries for the post-World War II period. We then describe the main features, thwarting mechanisms and phases of each of what we label the industrial capitalism supercycle and the financial globalisation supercycle respectively.

The supercycles framework

Minsky is best known for his analysis of financial business cycles, driven by the interactions between expectations, fixed capital assets, and the financing of those assets (Wray and Tymoigne Citation2009, Nikolaidi Citation2017). However, Minsky’s writings also contain less well-known insights about the interactions between macrofinancial processes and institutional change. Palley (Citation2011) develops these insights, drawing a distinction between Minskyan ‘basic cycles’ and supercycles.Footnote1 In our framework, the basic cycle includes all short-run and medium-run economic fluctuations generated by the interactions between financial and real factors both domestically and globally: in addition to the corporate balance sheet-bank nexus of Minsky (see e.g. the findings in Stockhammer et al. Citation2019), this also includes cyclical dynamics generated by accumulation of household debt, shifts in income distribution, and shifting patterns of global demand, trade and portfolio investment.Footnote2 Basic cycles thus capture both business cycles and (domestic and global) financial cycles.Footnote3

Why do basic cycles rarely become explosive? The answer lies in Minsky’s concept of thwarting mechanisms: ‘customs, institutions or policy interventions that make observed values of macroeconomic variables different from what they would have been if each economic agent pursued “only his own gain”’ (Ferri and Minsky Citation1992, p. 84). Thwarting mechanisms reduce the amplitude of basic cycles, constraining instability by imposing ceilings and floors on the dynamic path of the economic system.

We distinguish between floor and ceiling thwarting mechanisms. Floor mechanisms aim to ensure a minimum level of aggregate demand, either through deliberate policy interventions (e.g. activist fiscal policy) or as a side effect of other developments (e.g. expansion of household debt to maintain consumption spending). Conversely, ceiling mechanisms impose upper limits on economic expansion by restricting activities that may enhance growth but also generate instability. Examples of ceiling mechanisms include inflation targeting, financial regulation aimed at reducing procyclicality and leverage, and capital controls which restrict speculative financial inflows.

The supercycle is a long-run institutional and political cycle over which the effectiveness of a particular configuration of thwarting mechanisms first increases and then declines. We postulate that macrofinancial stability is primarily driven by the effectiveness of thwarting mechanisms. We therefore define four phases of the supercycle: expansion, maturity, crisis and genesis. During the expansion phase, newly introduced thwarting mechanisms are effective, leading to economic expansion and broad social and financial stability: economic and financial activity is disrupted by the recessions of the basic cycles, but thwarting mechanisms prevent a systemic crisis.

Economic agents adapt to the new institutional environment, innovating to preserve or increase profits, and thereby reducing the effectiveness of thwarting mechanisms. Mechanisms introduced to reduce one source of instability may over the long run become destabilising: a mechanism that stabilises economic activity might simultaneously generate inflationary pressures or lead to rising private indebtedness. Once the effectiveness of thwarting mechanisms starts to decline, the cycle enters the maturity phase, during which economic expansion continues but macrofinancial stability is decreasing.

This ultimately leads to crisis when the institutional framework is no longer sufficient to constrain the dynamics of the basic cycle. At this point, a basic-cycle recession leads to deep economic, political and social instability, and institutional restructuring. While government intervention may stabilise the economy, broad-based recovery is impossible: the institutional structure no longer ensures macrofinancial stability. The ensuing genesis phase sees attempts to establish a new configuration of thwarting mechanisms. The next supercycle will begin when – or if – effective new mechanisms are introduced. In the case that – for political, social or technological reasons – such mechanisms cannot be introduced, the crisis phase will be prolonged, accompanied by political and social turmoil, as new institutional structures emerge.

The supercycle shares similarities with the ‘mode of regulation’ in the Regulation School: both concepts provide a periodisation of capitalism based on norms, institutions and organisational patterns that temporarily stabilise capitalism over a specific period (Boyer Citation2005, Jessop and Sum Citation2006, Guttmann Citation2016). There are important differences, however. First, in the Regulation School, the mode of regulation is assumed to accompany a specific ‘accumulation regime’: this emphasises the specifics of productive processes on the supply side. In contrast, our supercycle emphasises the links between aggregate demand, the financial system and institutional change, reflecting the critical macro-finance concern with the co-evolution of financial structure and macroeconomic policy institutions (Gabor Citation2020). Second, our institutional supercycle relies on an explicit four-phase classification system that makes clear how cyclical patterns emerge. Although the modes of regulation imply a cyclicality as well, the exact drivers of this cyclicality are less clear-cut in the Regulation School.

The supercycles framework also builds upon the concept of macro-regimes in Blyth and Matthijs (Citation2017), wherein the growth regime is defined by the choice of target of macroeconomic policy, which in turn reflects the balance of power between social classes: a full employment target reflects strong labour, while inflation targets reflect a powerful financial sector. We extend the concept of macro-regimes in two ways. First, we postulate that political conflict and the distribution of power influences not only target selection but also the specific architecture of thwarting mechanisms aimed at maintaining broader macrofinancial stability and avoiding political instability. Second, in our framework, the process by which thwarting mechanisms are eroded is specific to each supercycle: the strength of labour in the 1970s undermined the wage-price consensus, giving rise to inflationary pressure, while the strength of finance in the 2000s constrained the effectiveness of financial regulation.

The supercycles framework shares some features with the recent literature that attempts a synthesis between comparative political economy and post-Keynesian growth models (Baccaro and Pontusson Citation2016, Stockhammer Citation2022). Growth models are the result of thwarting mechanisms: a wage-led growth model, for example, reflects thwarting mechanisms that keep wage-driven consumption spending strong enough to maintain aggregate demand and economic growth. The supercycles framework highlights that such mechanisms – and thus any given growth model – will ultimately lose effectiveness because of endogenous institutional erosion.

Macrofinancial stability and the two supercycles

To quantitatively capture the evolution of macrofinancial stability in G7 countries, we develop the Macrofinancial Stability Index (MSI). The MSI is constructed using a number of ‘floor’, ‘ceiling’ and ‘corridor’ macroeconomic and financial variables. To ensure macrofinancial stability, these variables should either be prevented from decreasing without limit (e.g. economic growth, employment rate), increasing without limit (e.g. credit-to-GDP ratios), or both (e.g. inflation).

Let (i) be n floor variables and

and

their maximum and minimum values over the entire period under investigation, (ii)

be m ceiling variables and

and

their maximum and minimum values and (iii)

be q corridor variables and

,

and

their maximum, minimum and median values. Let also

and

be the weights of floor, ceiling and corridor variables, respectively. The MSI is calculated as one minus a weighted average of the normalised distances of floor, ceiling and corridor variables from their maximum, minimum and median values respectively:

The MSI thus takes values between 0 (minimum stability) and 1 (maximum stability).Footnote4

We calculate the MSI for the G7 countries since the 1960s/1970s (the starting year differs for each country depending on data availability). We use economic growth and the employment rate as floor variables, the credit-to-GDP ratio, the bank leverage ratio and current account deficit-to-GDP ratio as ceiling variables and the inflation rate and the house price growth rate as corridor variables.Footnote5 The variables and the data used for construction of the index are described in .Footnote6 In our calculations, floor, ceiling and corridor variables are weighted equally (i.e. ).

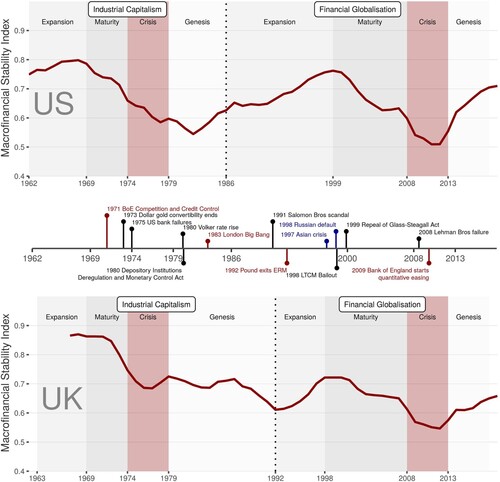

shows the MSI for the US (top pane) and the UK (bottom pane) alongside a timeline of key events and institutional developments. The figure also highlights the phases of the two post-war supercycles (see following sections).

Figure 1. Macrofinancial Stability Index (MSI) and supercycles, US (1962-2019) and UK (1967-2019).

Note: The figure depicts the 5-year moving average of the MSI. The data sources are reported in Table A1.

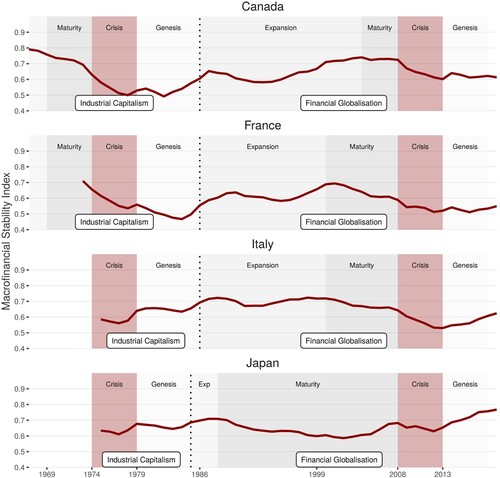

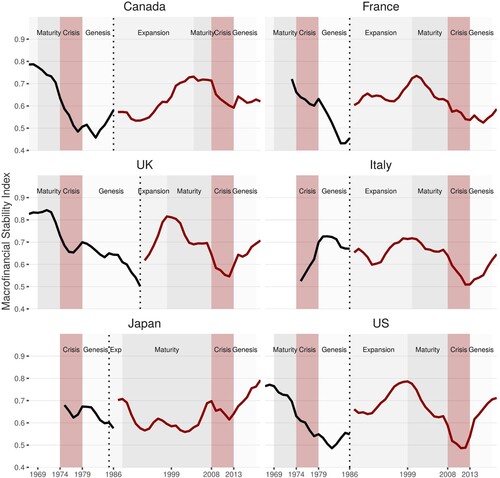

Macrofinancial stability in the US exhibits a cyclical pattern with peaks in the late 1960s and late 1990s, and troughs in the early 1980s and following the crisis of 2008. During 2012–2019, macrofinancial stability increased. A similar pattern is observed in the UK, with the exception that there was a decline in stability in the years preceding the UK’s exit from the European Exchange Rate Mechanism, followed by a recovery. The MSI for the other G7 countries behaves in a similar way (see Figure A1 in the Appendix), with the exceptions of Germany and Japan. In Germany, stability deteriorated in the 1990s and improved in the 2000s, due to specific factors such as reunification and the increase in export demand resulting from adoption of the euro.Footnote7 In Japan, the early onset of stagnation led to stability declining in the 1990s. Despite these differences, it is clear that G7 countries experienced common secular cyclical movements in their macrofinancial stability in the post-World War II period.Footnote8

We use the four-phase classification system of the supercycles framework to explain these common cyclical movements. We postulate a positive relationship between the MSI and the effectiveness of thwarting mechanisms: the MSI increases during the expansion and genesis phases and declines during the maturity and crisis phases. The phases shown in are identified based on this postulated relationship in conjunction with our analysis of the evolution of the architecture of thwarting mechanisms. We therefore identify two post-war supercycles: the industrial capitalism (IC) supercycle and the financial globalisation (FG) supercycle.Footnote9 summarises the main features of each supercycle, along with the drivers of basic cycles, the main thwarting mechanisms and the causes of erosion of these mechanisms. In the subsequent sections we provide a detailed account of the institutional architecture and thwarting mechanisms that prevailed during each of the two supercycles, and the outcomes for macrofinancial stability.Footnote10 Our analysis covers the G7 countries, with a particular focus on the US since the main institutional changes that drove the supercycles took place there and affected the rest of the G7 economies.

Table 1. Two post-war supercycles.

The industrial capitalism supercycle

Main features and basic cycles

The period immediately following World War II marks the start of the expansion phase of the IC supercycle. The defining feature of this period is the relationship between the capital investment of industrial firms and macroeconomic dynamics: the basic cycle was driven by the interacting dynamics of corporate investment and financing (as in Minsky’s financial instability hypothesis; see e.g. Stockhammer et al. Citation2019 for empirical evidence), and by the interaction of functional income distribution and aggregate demand (see ).Footnote11 The financial systems of high-income capitalist nations financed the production of expensive and long-lasting capital assets: in this age of weak and immobile finance, bankers sought to ensure that the debts of corporations could be serviced without disruption to the development of the industrial capital structure. The architecture of thwarting mechanisms – from labour market institutions to the welfare state and capital controls – created a balance of power between labour and big capital (Blyth Citation2002).

Thwarting mechanisms

Over a long period during the IC supercycle, a range of mechanisms ensured – or aimed to ensure – that the growth of total expenditure kept pace with the expansion of capacity, by setting a floor under the level that total expenditures could fall to in periods of crisis and recession (see ). Wages kept pace with productivity growth, alongside a generous welfare system, so that consumption expenditures grew in line with productive capacity. In many high-income countries, investment spending was supported by bank credit, in the context of long-run relationships between industrial capitalists and banks. Counter-cyclical government spending was widely accepted as a policy tool.

The supercycle was characterised by a wage policy consensus under which it was broadly accepted that real wages should grow in line with productivity (Levy and Temin Citation2007). A range of institutional mechanisms, including support for trade union membership and incorporation of trade unions into wage bargaining processes, ensured that wages kept pace with rising productivity. Steady wage growth translated into growth in consumption, and thus demand for the rapidly increasing industrial output. This in turn ensured that profits were maintained, stimulating sustained growth in capital investment. Between 1940 and 1970, in G7 countries, government consumption spending (on health, education and so on) and transfer payments rose more rapidly than GDP, while military expenditures declined as a share of total spending. Government investment grew steadily, at roughly the same pace as GDP (Glyn et al. Citation1990).

Central banks and the commercial banking system accommodated this regime of steady growth in wages, consumption and government expenditure: banks were willing to finance long-lived capital assets because it was expected that non-financial firms would meet their debt payment commitments since (i) steady growth of aggregate demand was expected and (ii) in the presence of product market regulation and oligopolistic structures, firms would operate under mark-up pricing, meaning that money wage increases would not squeeze profit margins (Epstein and Schor Citation1990).Footnote12 As a result, both capacity utilisation and profit margins would be preserved, maintaining firms’ profitability and ensuring that debts would be repaid. In turn, it was in bankers’ interests to ensure that debt could be rolled over at affordable terms.

Throughout the 1950s and much of the 1960s, this institutional structure placed a floor under aggregate demand and investment growth, thwarting stagnationary tendencies and ensuring steadily rising productivity, incomes and living standards.

The IC supercycle was also characterised by a particular configuration of ceiling thwarting mechanisms (see ). Trade unions played a dual role; in addition to ensuring that wage growth kept pace with productivity growth, wage bargaining, particularly in the US also served to hold wage growth in check, ensuring that wages would not grow in excess of productivity, squeezing profits and lowering investment spending (Brenner Citation2006). Some countries experimented with income policies that restrained wage growth (Tomlinson Citation1987). Nonetheless, as trade union membership grew, and wartime national pay bargaining gave way to more localised factory level bargaining, wage growth in excess of productivity led to a gradual decline in the profit share in most high-income countries during the 1950s and 1960s (Glyn and Sutcliffe Citation1972).

Finance was constrained by both the international monetary and financial architecture and by national financial regulation. The Bretton Woods system of fixed-but-adjustable exchange rates eliminated both the macroeconomic volatility resulting from exchange rate movements, and the potential for speculation on such movements. Controls on cross-border financial flows, to prevent destabilising ‘hot money’ flows, were widely implemented under the Bretton Woods system (Helleiner Citation1994). Credit subsidies and ceilings on deposit and loan rates constrained retail banking, while the Glass-Stegall Act enforced the separation of investment and commercial banking activity, curtailing speculative activities by commercial banks. As a result, ‘banking crises were almost non-existent in the heyday of Bretton Woods’ (Bordo et al. Citation2001, p. 57).

Erosion of thwarting mechanisms, crisis and genesis

During the expansion phase, effective floor thwarting mechanisms kept unemployment low. Alongside expansion of the welfare state, this reduced the cost of job loss and strengthened the bargaining position of labour: as productivity growth slowed in the late 1960s, unions were able to enforce continued high real wage growth. The resulting squeeze in profits led to slowing capital investment and, as firms raised prices in an attempt to preserve profit margins, a wage-price spiral arose (Marglin Citation1990). This spiral eroded the wage policy and the wage-price consensus that served as floor and ceiling thwarting mechanisms respectively during the IC supercycle ().

At the same time, the international institutional architecture came under increasing strain. The US trade surpluses of the 1950s and 1960s, driven by post-war reconstruction in Europe and Japan, gave way to deficits by the 1970s, alongside persistent German and Japanese surpluses. The resulting downward pressure on the dollar was intensified by a private institutional innovation: the rise of the Eurodollar market (). From around 1957, there was rapid growth in dollar-denominated banking outside the US, with London at the centre. This was driven by a number of factors, including US regulatory changes such as the introduction of ‘Regulation Q’ which placed a ceiling on the rate of interest that US banks could pay on deposits; this led to competition for dollar deposits from offshore subsidiaries in London that could pay higher rates (Moffitt Citation1984, Strange Citation1986). In the 1960s, the Eurodollar markets provided a mechanism for offshore dollars to be ‘recycled’ back to the headquarters of US banks, but in the 1970s this flow went into reverse: ‘speculators borrowed dollars in the Eurodollar markets and promptly sold them for other currencies, so that foreign central banks found it necessary to buy dollars on a large scale in order to prevent the undue appreciation of their currencies’ (Tew Citation1977, p. 164).

By 1971, the scale of reserve outflows meant that a run on the gold reserves of the US was becoming inevitable; Nixon announced a ‘temporary’ suspension of dollar convertibility into gold, with the intention of forcing surplus countries to abandon their pegs to the dollar. The move was successful and marked the beginning of the end of the Bretton Woods system, and the start of the crisis phase of the IC supercycle in which rising inflation and high unemployment accompanied the disorderly transition to floating exchange rates. Oil price hikes in 1973 and 1979 destabilised the system further and helped to cement floating rates, initially intended as a temporary measure when introduced in 1973, as a permanent feature. This greatly reduced the issue of ‘dollar overhang’ – the problem of excess dollars held outside the US – because dollar FX reserves were now seen as a blessing not a burden. As a result, interest in coordinated international monetary reform waned and the position of the US – which wanted to make floating exchange rates permanent and opposed an enhanced role for IMF special drawing rights (SDRs) – was strengthened. In 1974, capital controls on dollar outflows from the US and inflows into other countries were substantially liberalised.

A run of bank failures in the US and Germany in 1974, including Bankhaus Hersatt, Franklin National and First National of San Diego, led to the founding of the Basel Committee at the end of 1974, but no further action was taken as contagion appeared limited. The economic crisis lasted through most of the 1970s, until the decisive shift in policy direction under Reagan and Thatcher marked the start of the genesis phase (see and A1), ushering in the new configuration of thwarting mechanisms that would characterise the financial globalisation (FG) supercycle (see ).

A defining feature of the early Reagan and Thatcher years was the drive to curtail inflation by sharply reducing the bargaining power of labour, in many cases in direct confrontation with workers’ organisations. Under successive governments in the US and the UK, legal frameworks protecting workers’ rights and collective bargaining were progressively dismantled (Silvers and Slavkin Citation2009). In the US, the minimum wage, introduced as part of the New Deal in the 1930s, no longer increased in line with prices and productivity. The project of dismantling the post-war welfare state was initiated (Stedman Jones Citation2014). Tax structures became steadily less progressive (Piketty and Saez Citation2007). Instead of full employment, the stated objective of macroeconomic policy shifted to control of inflation, to be achieved by constraining the growth of the money supply.

The resulting recession and mass unemployment proved effective in constraining wage demands, but came at the cost of weakening aggregate demand. As wage growth stagnated, and protection of those on lower incomes was removed, spending could not keep pace with productivity. New thwarting mechanisms were required to sustain demand. At the national level, the expansion of private debt substituted, at least partially, for lost purchasing power. Internationally, the possibility of sustained current account imbalances in the post-Bretton woods system allowed some countries to rely on exports to supplement domestic demand (the promise that flexible rates would eliminate such imbalances was oversold). But debt expansion required further changes; the new national and international institutional structure provided the environment for the emergence of the so-called shadow banking system, facilitating an expansion of private debt and financial system leverage to hitherto unseen scales of magnitude and complexity.

Flexible exchange rates did not eliminate the cross-border imbalances that ultimately overpowered the Bretton Woods system: the total surpluses of creditor nations such as Japan and Germany doubled between 1973 and 1979 (Strange Citation1986, p. 8). Neither did the adoption of floating exchange rates eliminate exchange rate volatility – on the contrary, volatility increased along with the volume of trading on foreign exchange markets. With central banks no longer committed to intervention in these markets, private actors needed to hedge exchange rate risks: this was achieved by purchasing forward contracts, while investing funds short term. Strange argues that this is the reason for the concurrent growth in both derivatives and money markets: ‘this is the link that connects the foreign exchange market with the short-term credit market, exchange rates with interest rates’ (Strange Citation1986, p. 12).

From the 1980s onwards, the system of financial regulation put in place in the US, as part of the New Deal, including the Glass-Steagall act, separating commercial banking and investment banking activities, began to be unwound. The loosening of regulations on banks and mortgage lenders, and on inter-state mergers and acquisitions activities, paved the way for the boom in mortgage lending. In 1968, Fannie Mae was converted from a government agency into a ‘government-sponsored private institution’: a ‘profit-seeking, shareholder owned company, tasked with creating a secondary market for mortgages made to low- and moderate-income borrowers’ (Silvers and Slavkin Citation2009, p. 325). The nascent mortgage-backed securities (MBS) market of the 1970s led to the development of the ‘agency passthrough’ market in the 1980s, in which securities issued by institutions owned or sponsored by the government were traded. In 1982, regulatory changes facilitated the issuance of mortgage-backed securities by financial institutions without government sponsorship, and in 1984 legislation was introduced allowing private investors to hold MBS (Thompson Citation2009, Berliner et al. Citation2016). By 1993, 60% of mortgages were securitised, and, in 2004, private, non-government sponsored firms’ issuance of MBS surpassed issuance by Fannie May for the first time (Silvers and Slavkin Citation2009).

In the US, the Depository Institutions Deregulation and Monetary Control Act of 1980 (DIDMCA) removed caps on deposit interest rates, allowed mortgage lenders to issue checking deposits, and encouraged competition among bank and non-bank financial institutions. Retail depositors shifted to higher-interest money market funds, while firms replaced bank credit with the issuance of commercial paper. Similar changes had arrived earlier in the UK, with the introduction of Competition and Credit Control by the Bank of England in 1971 (Goodhart Citation2014). In London, the Big Bang of 1983 abolished the distinction between stockbroking and market-making and proprietary trading activity. Banks bought out stockbroking firms, and moved into investment banking activity (Chick Citation2013). Light touch regulation attracted foreign banks, which joined those involved in Eurodollar lending. Regulators in other jurisdictions came under increasing pressure to maintain competitiveness by following suit and deregulating their financial systems. The stage was set for the financial globalisation supercycle.

The financial globalisation supercycle

Main features and basic cycles

The election of Reagan and Thatcher cemented the foundations of the financial globalisation supercycle. The dynamics of the basic cycle shifted as large corporations turned to capital markets and banks to mortgage borrowers. Cyclical dynamics driven by mortgage lending and household consumption expenditure replaced the interaction between bank lending and corporate investment of the industrial capital supercycle, altering the nature of the monetary circuit (Michell Citation2017). This household credit-driven process required greater systemic leverage than a circuit driven by corporate borrowing for capital investment. Shadow banking made this possible: it allowed banks to avoid Basel capital requirements, using securitisation to move assets off balance sheets while simultaneously generating a flow of assets that would provide the collateral needed to satisfy the growing demands of owners and managers of wealth. Growing concentrations of wealth (and liquidity in the form of corporate cash pools and official FX reserves) led to rising demand for financial securities (see ).

The emergence of a securities-based credit system alongside the dismantling of capital controls fundamentally transformed the role and nature of finance, giving rise to a new type of actor: the neorentier. Neorentiers are (mostly global) financial institutions whose activities are oriented towards the production and collateral-based financing of new asset classes. They include market-based banks, global institutional investors and asset managers. Neorentier profitability is substantially influenced by daily changes in asset prices via mark-to-market balance sheet effects, driving cycles of liquidity and leverage (Adrian and Shin Citation2010, Lindo Citation2013, Peer Citation2016, Gabor Citation2018, Gabor and Vestergaard Citation2016, Citation2018). Neorentiers evolved into global actors capable of influencing institutional and regulatory change, and therefore the architecture of thwarting mechanisms (Hardie and Howarth Citation2013). Minsky used the term ‘money manager capitalism’ to capture neorentiers’ increasing influence on the financial system and the economy (Minsky and Whalen Citation1996, Wray Citation2011, Whalen Citation2012).

We thus update the concept of the rentier to reflect evolutionary changes during the FG supercycle. The financialisation literature defines rentiers as the recipients of income from financial activities, focusing primarily on traditional financial assets such as stocks and bonds (Epstein and Jayadev Citation2007, Stockhammer Citation2008, van Treeck Citation2009, Hein Citation2015). This does not accurately reflect the transformation of the global financial system since the 1970s. Neorentiers are a distinct type of rentiers. They differ from traditional rentiers in that their profits primarily come from shadow banking activities, such as derivatives trading, repo transactions and pooling and tranching of risk. Neorentiers alter the functions of traditional financial assets, and thus the role of rentiers. Securitisation allows banks to escape the limits to loan expansion set by capital requirements and to disconnect loan defaults with on-balance sheet risks. Developments in repo markets influence system-wide leverage and the liquidity of the financial system, affecting the demand for securities and thus the cost of (securities) financing for firms and governments (Adrian and Shin Citation2010, Gabor Citation2016).

The erosion of the IC thwarting mechanisms facilitated the rise of shadow banking. The rollback of public welfare provision, the switch from ‘pay as you go’ to ‘funded’ pension schemes and wealth concentration arising from higher income inequality and states’ weaker ability to tax multinationals and wealthy individuals gave rise to large-scale institutional asset management such as insurance and pension schemes (Toporowski Citation2000, Haldane Citation2014, Lysandrou Citation2016). Neorentiers successfully pressured for open capital accounts and the re-organisation of local financial systems around collateral-based finance (Gabor Citation2018), often through international financial institutions (Kentikelenis and Babb Citation2019). Hedge funds targeted higher returns through repo-based leverage. Broker dealers, often part of global banking groups, deployed their balance sheets to connect neorentiers seeking leverage to those seeking safety in money market deposits via collateral-intensive relationships (Pozsar Citation2014). Banks transformed their business models towards market-based finance, under pressure from the loss of corporate customers and depositors chasing higher returns via shadow banking (Liikanen Citation2012). Traditional rentiers became increasingly dependent on the actions of neorentiers.

The drivers of the basic cycle thus shifted from corporate lending and capital investment to mortgage lending, housing investment and bond financing in an increasingly internationalised and market-based financial system. The activities of neorentiers started driving the fluctuations in the availability and cost of credit, either directly (e.g. through the effects of repo markets and mortgage-backed securities on bond yields and mortgage lending) or indirectly via the effects of shadow banking on the fragility of balance sheets across the financial system. This shift took place alongside the transition to a new architecture of thwarting mechanisms.

Thwarting mechanisms

In many high-income countries, most notably the US, wage growth declined from the high rates of the 1960s more sharply than productivity growth (Glyn Citation2007). From the 1990s onwards, increasing concentration led to higher corporate mark-ups, particularly in the US, and a falling wage share in national income. Pay restraint and the growing importance of high ‘value added’ and high mark-up sectors, such as technology and finance, eased the profit squeeze from the IC supercycle – at least at the aggregate level. While corporate earnings recovered, shifts in income distribution also brought stagnationary tendencies: weak or even negative income growth for lower income households constrained consumption spending, while business investment remained weak for much of the period, even as profits recovered.

The ideological shift on macroeconomic management brought independent inflation targeting central banks alongside increasingly market-financed fiscal deficits.Footnote13 Mass privatisation reduced the state’s economic footprint, while previous gains on employment protection and unemployment benefits were substantially rolled back (Glyn Citation2007). Growth increasingly relied on rapid expansion of leverage and increasing financial activity.

New financial institutional structures were required to enable leverage to expand beyond traditional constraints. During the expansionary phase of the FG supercycle (see , and A1), shadow banking expanded significantly, absorbing the flow of assets resulting from the continued expansion of credit. Securitisation and the originate-to-distribute model allowed banks to transform illiquid assets such as mortgage loans into marketable securities. These securities were financed with short-term liabilities such as repos and asset-backed commercial paper (ABCP) (Krishnamurthy et al. Citation2014).

Collateral became critical for funding neorentier balance sheets. Neorentiers issue short-term repo deposits secured by bond collateral (analysed as shadow money by Gabor and Vestergaard Citation2016, Citation2018), borrowing from institutional cash pools who acquire legal ownership of collateral, and can liquidate if borrowers default (Pozsar Citation2014). Repo borrowing translates rising asset prices into increasing leverage capacity because collateral is marked to market (Adrian and Shin Citation2010).Footnote14 While the turn to collateral reflects faith in ‘market liquidity’ as an effective substitute for regulatory oversight (Bini Smaghi Citation2010, Sissoko Citation2019), liquidity is not guaranteed: sudden declines in collateral prices can lead to margin calls, liquidity spirals and fire-sales of collateral securities, amplifying asset price deflation and exacerbating liquidity shortages (Brunnermeier and Pedersen Citation2009, Adrian and Shin Citation2010).

The rise of collateral-based finance changed the relationships between central banks, governments and the financial markets. In the 1990s, central banks in high-income countries collectively sanctioned neorentiers’ turn to money-market funding by deregulating repo markets and introducing regular auctions facilitated by primary dealers in the sovereign bond markets (Gabor Citation2016).

These reforms intended to develop liquid government bond markets, a pre-requisite for achieving low borrowing costs for governments and the smooth transmission of monetary policy. But reforms also entrenched the ‘infrastructural power’ of finance (Braun Citation2020): by becoming critical in the achievement of fiscal and monetary policy targets, neorentiers enhanced their ability to oppose unwanted policy interventions or tighter regulatory measures (Gabor Citation2016). The rising power of neorentiers thus served to discipline states and central banks, curbing the effectiveness of fiscal, monetary and regulatory thwarting mechanisms.

Easy credit conditions allowed sustained expansion of private debt, enabling aggregate demand to keep up with productive capacity in the face of weak income growth and government retrenchment. Savings ratios fell throughout the 1980s and 1990s in Anglo-Saxon economies. Credit-financed consumption took over from capital investment and wage-led consumption as the driver of growth in many countries, placing a floor under aggregate demand (Glyn Citation1990, Baccaro and Pontusson Citation2016).

Not all G7 countries relied on debt-financed consumption expenditure: some, such as Germany, relied instead on export demand to maintain growth. High export demand was, however, possible due to debt-financed imports of other countries. Thus, the debt-financed consumption expenditures of Anglo-Saxon economies provided a floor to both domestic and global aggregate demand; at the same time, financial activity became increasingly cross-border, as neorentiers looked to global bond markets to fill their portfolios. Basic cycles became increasingly synchronised across borders, shaped by the global financial cycle (Rey Citation2015).

The FG thwarting mechanisms could not match the performance of the IG supercycle: growth in income per capita and productivity was lower than in the expansion and maturity phase of the previous supercycle. Despite anti-inflation rhetoric, the period was characterised by progressively looser credit conditions, resulting from both financial system expansion, and progressively lower policy interest rates. Volatility in asset prices increased, forcing central banks to extend lender of last resort (LOLR) support, for instance with the secondary bank crisis in the UK or the Continental Illinois and Savings and Loans crises in the US.Footnote15 But the effectiveness of this thwarting mechanism would come under pressure in a supercycle increasingly reliant on collateral-based liquidity provision.

Erosion of thwarting mechanisms, crisis and genesis

The FG supercycle relies on two main ceiling thwarting mechanisms: bank capital regulation and inflation targeting (see ). Neither proved effective. The microprudential focus of Basel regulations effectively ignored shadow banking and cross-border market-based financial activity. The apparent success of inflation targeting in generating the so-called ‘great moderation’ – in reality the result of forces largely outside of central bank control – drove the hubristic belief that ‘macroeconomics [had] succeeded’ (Lucas Citation2003, p. 1). When confronted with the possibility that low policy rates encourage leverage, central banks decided that it was more expedient to clean up after asset bubbles than lean against them. The shift to monetarism and then inflation targeting thus encouraged shadow banking and cemented the infrastructural power of neorentiers.

While shadow banking initially facilitated debt-led economic expansion, it rendered this expansion progressively more fragile due to rising systemic leverage and collateral-based interconnectedness. This became apparent with the failure of Long-Term Capital Management (LTCM) in 1998, the first episode of global volatility triggered by repo-financed leveraged positions in securities. Following the Asian financial crisis of 1997 and the Russian crisis the following year, LTCM saw increasingly large margin calls on these liabilities and was eventually rescued by its largest counterparties to avoid fire sales of collateral securities (Rubin et al. Citation1999). Central banks in the BIS Committee on the Global Financial System described LTCM as the first global crisis of collateral (Gabor Citation2016).

The collapse of LTCM marked the start of the maturity phase of the FG supercycle in most G7 countries (see and A1): shadow banking began eroding the thwarting mechanisms of the supercycle in a system with two key vulnerabilities. First, the floor imposed by credit expansion turned out to be weak and reliant on repeated loosening of monetary conditions in order to support asset prices. Second, neorentiers’ increasing reliance on daily mark-to-market across repo and derivatives contracts introduced new pro-cyclical financial mechanisms, reinforcing movements in asset prices, market liquidity and leverage and thus credit conditions.

Rather than stronger financial regulation, the technocratic response to LTCM’s collapse was to use collateral as a ‘disciplinary’ thwarting mechanism: neorentiers were to value collateral to market daily and improve their risk management regimes (Rubin et al. Citation1999), so that the prospect of falling collateral prices and the thus funding pressures for collateral-based liabilities would keep leverage in check. To encourage this shift, central banks adopted neorentier practices of collateral-based liquidity provision: by 2000, central banks in high-income countries replaced outright interventions in government bond markets, whether for monetary policy implementation or lender of last resort support, with repo lending (Gabor and Ban Citation2016). Central banks promoted government bonds as safe assets for collateral-based finance (CGFS Citation1999), downplaying the possibility that inadequate volumes of public debt would induce shadow banking innovation to increase the supply of ‘safe assets’ via securitisation (Coeuré Citation2016, Gabor Citation2016, Gabor and Vestergaard Citation2018).

The discipline of collateral proved illusory. Following Lehman’s collapse, neorentiers turned away from private collateral, triggering liquidity and haircut spirals on previously ‘safe’ assets (Gorton and Metrick Citation2012). This called into question the effectiveness of central banks’ lender of last resort function: the classic LOLR function was premised on restoring trust in banks not collateral. As trust shifts from banks to collateral, ensuring the liquidity of markets for collateral securities becomes a key condition to maintain resilience of neorentiers’ liabilities. LOLR repo loans are ill-equipped to deal with declining collateral market liquidity (Dooley Citation2014): if central banks make emergency loans against collateral securities that fall in price, they have to call margin on those loans, thus reinforcing falling prices and worsening funding liquidity conditions for borrowers (Mehrling et al. Citation2013, Gabor and Ban Citation2016, Barthélemy et al. Citation2018). If dealer-brokers become unwilling to make markets in securities, the only way to maintain the liquidity of a securities-based credit system in the face of sustained selling is for the ultimate provider of liquidity—the central bank—to absorb a flow of securities onto its own balance sheet as they are sold, stabilising the price.

In response to the erosion of the traditional LOLR mechanism, central banks introduced two innovations: first, an expansion of the LOLR framework to include new types of collateral and collateral swaps and, second, a securities market maker of last resort (MMLR) function. The former has enabled banks to access emergency liquidity against a broader set of assets on their balance sheets, and dealers to obtain the collateral needed to fund market-making activity. But this may not be sufficient to stabilise systemic neorentier balance sheets if banks and dealers remain unwilling to purchase securities on the scale required to restore market liquidity. Some central banks therefore adopted a formal MMLR facility. MMLR targets collateral market liquidity instead of banks’ funding liquidity: central banks step in to purchase securities when no one else will, placing a floor on the prices of securities used as collateral by neorentiers (Gabor Citation2016, Citation2020). Despite some overlap, MMLR is functionally different to quantitative easing (QE), which involves purchases that raise the prices of both public and privately-issued securities, making liabilities collateralised with these securities cheaper. Notably, the Bank of England was the first central bank to adopt QE in 2009, and before the COVID-19 pandemic, the only one to formalise MMLR in 2015 (Carney Citation2015).

While crisis-era innovations succeeded in preventing financial system collapse and depression, sustained growth has not returned. Key features of the institutional architecture of the FG supercycle persist: weak and ‘flexible’ labour, high inequality and government retrenchment. Without a change in this architecture, it is difficult to identify a likely source of sustained demand growth other than a return to credit expansion. But for a period of sustained credit expansion there must be demand for credit, lenders must perceive borrowers as creditworthy, and the banking and financial system must have spare capacity. In a securities-based credit system, both loan originators and the buyers and funders of securitised loans must perceive loans as sufficiently safe. In the post-GFC period, high debt stocks, low growth, weak investment, fiscal retrenchment and the persistence of inequalities have limited the perceived creditworthiness of much of the private sector while the most creditworthy sector, large corporations, has direct access to the bond markets. Further, banks and financial institutions are now subject to stricter regulation and scrutiny due to Basel III. Liquidity and capital requirements impose constraints on credit expansion, both for institutions that lend directly (as loan originators) or indirectly (as buyers of securities).

While institutional changes improved the effectiveness of stabilising mechanisms in the period prior to the pandemic, the ongoing push for asset-based welfare (Finlayson Citation2009) reinforces the structural drivers of neorentier capitalism without delivering a new source of stability. When the pandemic struck, a new configuration of thwarting mechanisms that could foster stability and expansion had not yet emerged. If successful, the ongoing genesis period will generate thwarting mechanisms that will reflect the rapid institutional change that has occurred as a result of the pandemic and greater awareness of the potential for future pandemics. Inevitably, the thwarting mechanisms of a potential next supercycle will also be driven by the even greater climate crisis.

Conclusion

Drawing on Minsky, this paper develops a framework for the analysis of ‘institutional supercycles’ in capitalism. We develop an index that demonstrates secular cyclical macrofinancial stability in G7 countries in postwar capitalism. We explain this as resulting from the emergence and erosion of thwarting mechanisms over two post-war supercycles.

Our approach opens possibilities for a wider research programme in macroeconomics, political economy and evolutionary finance. Further research is needed on the links between macrofinancial stability and thwarting mechanisms, and on the links between technological developments and institutional supercycles. Most urgently required, given the pandemic and climate crises, is a detailed understanding of the current genesis phase and the prospects for thwarting mechanisms that could underpin a new ‘green’ supercycle.

Acknowledgements

This paper is part of the project ‘Managing supercycles: globalisation and institutional change’ funded by Rebuilding Macroeconomics, Economic and Social Research Council (Grant reference: ES/R00787X/1). We are grateful to Angus Armstrong, Dirk Bezemer, Stephen Kinsella, Costas Lapavitsas, Carolyn Sissoko and two anonymous reviewers for useful comments. Previous versions of the paper were presented at the Bank of England (London, July 2019), the Rebuilding Macroeconomics conference (Edinburgh, September 2019), the FMM conference (Berlin, October 2019), the EAEPE conference (September 2020) and SOAS University of London (London, November 2019 and February 2021).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Ryoo (Citation2010) has developed a dual cycle framework based on Minsky, which however does not incorporate endogenous institutional change. Institutional change has been analysed within other Minskyan accounts (e.g. Whalen Citation2012, Argitis Citation2017) but without the explicit use of a cyclical framework, as in Palley (Citation2011).

2 This broader approach aligns with the formal Minskyan literature (Nikolaidi Citation2017, Nikolaidi and Stockhammer Citation2017) which has shown that Minskyan dynamics can be combined, for example, with endogenous changes in income distribution (Goodwin-Minsky models), consumption norms-led household debt (Minsky-Veblen models) and housing prices (real estate price Minsky models).

3 Domestic financial cycles typically exhibit a lower frequency than traditional business cycles (Borio Citation2014, Aldasoro et al. Citation2020) and are closely related to medium-term fluctuations in GDP (ECB Citation2018, Stockhammer et al. Citation2019). Global financial cycles seem to have a shorter duration than domestic financial cycles (Aldasoro et al., Citation2020).

4 An implication of the index construction method is that the value taken by the index depends on the period selected, because index values are calculated relative to historical country-specific minima, maxima and median values. The index is therefore primarily of use for analysing relative changes in a single economy, rather than making direct cross-country comparisons.

5 The evolution of the index remains almost the same when house price growth is removed as a corridor variable and/or share price growth is included as a floor variable.

6 The R code for compiling the MSI and Figures 1, A1 and A2 is available at: https://github.com/jomichell/supercycles-msi

7 The MSI for Germany is not reported in Figure A1, but is available at: https://github.com/jomichell/supercycles-msi

8 Figure A2 in the Appendix depicts the MSI when maximum, minimum and median values are calculated separately for each supercycle instead of using the entire period under investigation. The fluctuations in the MSI are similar to those in Figures 1 and A1, with one main difference: in Figure A2 the MSI values during the FG supercycle are, on average, closer to the MSI values during the IC supercycle. This difference is explained by the better overall macrrofinancial performance during the IC supercycle relative to the FG supercycle.

9 The time frame of these two supercycles corresponds approximately to the Fordist and the post-Fordist regimes in the Regulation School (see Friedman Citation2000).

10 In this paper we do not explicitly analyse the role of technology. However, we consider technological change to be a prerequisite for the emergence of an institutional supercycle, as per the literature on Kondratieff waves (see e.g. Grinin et al. Citation2017). Following Perez (Citation2010, Citation2016), the IC supercycle corresponds to the ‘deployment’ period of the ‘Age of Oil, Autos and Mass Production’, while the FG supercycle largely coincides with the ‘installation’ period of the ‘Age of Information and Communication Technologies’.

11 On the latter, debate persists on whether such cycles should be regarded as ‘profit-led’ with a procyclical wage share (à la Goodwin) or ‘wage-led’ with a countercyclical wage share, and whether cyclicality requires the interaction between financial and distributional factors (Blecker Citation2016, Stockhammer Citation2017). All of these possibilities are consistent with our framework.

12 Credit accommodation was not uniform across countries. Bank financing was predominant in France, Italy and Japan while credit markets were relatively underdeveloped and monetary policy was accommodative: relatively weak labour meant that greater monetary accommodation was possible without generating inflationary pressure from wage increases. In the UK, the US and Germany, with greater independence of central banks, less bank intermediation and stronger labour, monetary policy was less accommodative.

13 In reality, after the period of high interest rates at the start of the 1980s helped bring inflation under control by producing mass unemployment, monetary policy was gradually loosened as a way to maintain aggregate demand in the face of stagnationary tendencies. Fiscal deficits expanded rapidly following the oil shocks of 1974 and the breakdown of the Bretton Woods system, and persisted in Europe and the US—despite sustained efforts to limit them—until the mid-1990s.

14 Mechanically, a repo entails the sale and repurchase of collateral (financial securities) such that the difference in price implies the interest rate of the ‘loan’, while that the cash borrower retains economic ownership of collateral for the duration of the contract.

15 For a historical account of the LOLR facility, see Kindleberger (Citation1996).

References

- Acemoglu, D., Johnson, S., and Robinson, J.A., 2005. Institutions as the fundamental cause of long-run growth. In: P. Aghion, and S. Durlauf, eds. Handbook of economic growth. North Holland: Elsevier, 385–472.

- Adrian, T., and Shin, H.S., 2010. Liquidity and leverage. Journal of financial intermediation, 19 (3), 418–437.

- Aglietta, M., 1979. A theory of capitalist regulation: the US experience. London: New Left.

- Aldasoro, I., et al., 2020. Global and domestic financial cycles: variations on a theme. BIS Working Paper 864.

- Argitis, G., 2017. Evolutionary finance and central banking. Cambridge journal of economics, 41 (3), 961–976.

- Baccaro, L., and Pontusson, J., 2016. Rethinking comparative political economy. Politics & society, 44 (2), 175–207.

- Barthélemy, J., Bignon, V., and Nguyen, B. 2018. Monetary policy and collateral constraints since the European debt crisis, Banque de France Working Paper No. 669.

- Berliner, B., Quinones, A., and Battacharya, A., 2016. Mortgage loans to mortgage-backed securities. In: F.J. Fabozzi, ed. Handbook of mortgage-backed securities. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Bini Smaghi, L. 2010. Monetary policy transmission in a changing financial system – lessons from the recent past, thoughts about the future, Speech at the barclays global inflation conference, New York City, 14 June.

- Blecker, R.A., 2016. Wage-led versus profit-led demand regimes: the long and the short of it. Review of Keynesian economics, 4 (4), 373–390.

- Blyth, M., 2002. Great transformations: economic ideas and institutional change in the twentieth century. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Blyth, M., and Matthijs, M., 2017. Black swans, lame ducks, and the mystery of ipe’s missing macroeconomy. Review of international political economy, 24 (2), 203–231.

- Bordo, M., et al., 2001. Is the crisis problem growing more severe? Economic policy, 16 (32), 52–82.

- Borio, C., 2014. The financial cycle and macroeconomics: what have we learnt? Journal of banking & finance, 45, 182–198.

- Boyer, R., 2000. The political in the era of globalization and finance: focus on some regulation school research. International journal of urban and regional research, 24 (2), 274–322.

- Boyer, R., 2005. Coherence, diversity, and the evolution of capitalisms—The institutional complementarity hypothesis. Evolutionary and institutional economics review, 2 (1), 43–80.

- Braun, B., 2020. Central banking and the infrastructural power of finance: the case of ECB support for repo and securitization markets. Socio-economic review, 18 (2), 395–4. 18.

- Brenner, R., 2006. The economics of global turbulence. London and New York: Verso.

- Brunnermeier, M.K., and Pedersen, L.H., 2009. Market liquidity and funding liquidity. Review of financial studies, 22 (6), 2201–2238.

- Carney, M. 2015. Building real markets for the good of the people. speech at the lord mayor’s banquet for bankers and merchants of the city of London at the mansion house, 10 June. London.

- Chick, V., 2013. The current banking crisis in the UK: an evolutionary view. In: J. Pixley, and G.C. Harcourt, eds. Financial crises and the nature of capitalist money. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 148–161.

- Coeuré, B., 2016. Sovereign debt in the euro area: too safe or too risky? Keynote address at Harvard University, 3 November 2016.

- Committee on the global financial system (CGFS), 1999. Implications of repo markets for central banks. Basel: Bank for International Settlements.

- Dooley, M.P. 2014. Can emerging economy central banks be market-makers of last resort? BIS Paper No. 79.

- ECB. 2018. Real and financial cycles in EU countries: stylised facts and modelling implications, Occasional Paper 205.

- Epstein, G., and Jayadev, A., 2007. The rise of rentier incomes in OECD countries: financialization, central bank policy and labor solidarity. In: G.A. Epstein, ed. Financialzation and the world economy. Cheltenham, UK and Northampton, USA: Edward Elgar, 46–74.

- Epstein, G., and Schor, J., 1990. Macropolicy in the rise and fall of the golden age. In: M. Schor, ed. The golden Age of capitalism. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 126–152.

- Ferri, P., and Minsky, H., 1992. Market processes and thwarting systems. Structural change and economic dynamics, 3 (1), 79–91.

- Finlayson, A., 2009. Financialisation, financial literacy and asset-based welfare. The British journal of politics and international relations, 11 (3), 400–421.

- Friedman, A.L., 2000. Microregulation and post-Fordism: critique and development of regulation theory. New political economy, 5 (1), 59–76.

- Gabor, D., 2016. The (impossible) repo Trinity: the political economy of repo markets. Review of international political economy, 23 (6), 967–1000.

- Gabor, D., 2018. Goodbye (Chinese) shadow banking, hello market-based finance. Development and change, 49 (2), 394–419.

- Gabor, D., 2020. Critical macro-finance: a theoretical lens. Finance and society, 6 (1), 45–55.

- Gabor, D., and Ban, C., 2016. Banking on bonds: the new links between states and markets. JCMS: Journal of common market studies, 54 (3), 617–635.

- Gabor, D., and Vestergaard, J. 2016. Towards a theory of shadow money. Institute for New Economic Thinking Working Paper.

- Gabor, D., and Vestergaard, J., 2018. Chasing unicorns: the European single safe asset project. Competition & change, 22 (2), 139–164.

- Glyn, A., et al., 1990. The rise and fall of the golden age: an historical analysis of post-war capitalism in the developed market economies. In: M. Schor, ed. The golden Age of capitalism. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 39–125.

- Glyn, A., 2007. Capitalism unleashed: finance, globalization, and welfare. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Glyn, A., and Sutcliffe, R., 1972. British capitalism, workers and the profit squeeze. London: Penguin Books Ltd.

- Goodhart, C.A.E. 2014. Competition and credit control, LSE Financial Markets Group Special Paper Series No. 229.

- Gorton, G., and Metrick, A., 2012. Securitized banking and the run on repo. Journal of financial economics, 104 (3), 425–451.

- Grinin, L.E., Grinin, A.L., and Korotayev, A., 2017. Forthcoming Kondratieff wave, cybernetic revolution, and global ageing. Technological forecasting and social change, 115, 52–68.

- Guttmann, R., 2016. Finance-led capitalism: shadow banking, re-regulation, and the future of global markets. Basingstoke, New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Haldane, A.G., 2014. The age of asset management? Speech at the London Business School, 4 April 2014.

- Hall, P.A., and Soskice, D., 2001. Varieties of capitalism: the institutional foundations of comparative advantage. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hardie, I., and Howarth, D., 2013. Market-based banking and the international financial crisis. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Hein, E., 2015. Finance-dominated capitalism and re-distribution of income: a Kaleckian perspective. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 39 (3), 907–934.

- Helleiner, E., 1994. States and the reemergence of global finance: from Bretton Woods to the 1990s. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press.

- Hodgson, G., 2015. Conceptualising capitalism: institutions, evolution, future. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

- Jessop, B., and Sum, N.L., 2006. Beyond the regulation approach: putting capitalist economies in their place. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Jordà, Ò, et al., 2021. Bank capital redux: solvency, liquidity, and crisis. The Review of economic studies, 88 (1), 260–286.

- Jordà, Ò, Schularick, M., and Taylor, A.M., 2017. Macrofinancial history and the new business cycle facts. In: M. Eichenbaum, and J. A. Parker, eds. NBER macroeconomics annual 2016. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Kalecki, M., 1943. Political aspects of full employment. The political quarterly, 14 (4), 322–331.

- Kentikelenis, A.E., and Babb, S., 2019. The making of neoliberal globalization: norm substitution and the politics of Clandestine institutional change. American journal of sociology, 124 (6), 1720–1762.

- Kindleberger, C.P., 1996. Manias, panics, and crashes: a history of financial crises. 3rd edition. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Krishnamurthy, A., Nagel, S., and Orlov, D., 2014. Sizing up repo. The journal of finance, 69 (6), 2381–2417.

- Lavoie, M., 2012. Financialization, neo-liberalism, and securitization. Journal of post Keynesian economics, 35 (2), 215–233.

- Levy, F., and Temin, P. 2007. Inequality and institutions in 20th century America. Working Paper No. 13106, National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Liikanen, E. 2012. High-level Expert Group on reforming the structure of the EU banking sector. Final Report, Brussels.

- Lindo, D. 2013. Political economy of financial derivatives: a theoretical analysis of the evolution of banking and its role in derivatives markets, PhD dissertation, SOAS University of London.

- Lucas, R.E. Jr., 2003. Macroeconomic priorities. American economic review, 93 (1), 1–14.

- Lysandrou, P., 2016. The colonization of the future: an alternative view of financialization and its portents. Journal of post Keynesian economics, 39 (4), 444–472.

- Marglin, S.A., 1990. Lessons of the golden age: an overview. In: S.A. Marglin, and J.B. Schor, eds. The golden Age of capitalism: reinterpreting the postwar experience. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1–38.

- Mehrling, P., et al. 2013. Bagehot was a shadow banker: shadow banking, central banking, and the future of global finance, SSRN-2232016.

- Michell, J., 2017. Do shadow banks create money? ‘Financialisation’ and the monetary circuit. Metroeconomica, 68 (2), 354–377.

- Minsky, H.P., and Whalen, C.J., 1996. Economic insecurity and the institutional prerequisites for successful capitalism. Journal of post Keynesian economics, 19 (2), 155–170.

- Moffitt, 1984. The world’s money. New York: Touchstone.

- Nikolaidi, M., 2017. Three decades of modelling Minsky: what we have learned and the way forward. European journal of economics and economic policies: intervention, 14 (2), 222–237.

- Nikolaidi, M., and Stockhammer, E., 2017. Minsky models: a structured survey. Journal of economic surveys, 31 (5), 1304–1331.

- North, D., 2018. Institutional change: a framework of analysis. In: D. Braybrooke, ed. Social rules: origin; character; logic; change. London, NY: Routledge, 189–201.

- Palley, T.I., 2011. A theory of Minsky super-cycles and financial crises. Contributions to political economy, 30 (1), 31–46.

- Peer, N.O., 2016. A constitutional approach to shadow banking: the early shadow system, PhD dissertation, Harvard Law School.

- Perez, C., 2010. Technological revolutions and techno-economic paradigms. Cambridge journal of economics, 34 (1), 185–202.

- Perez, C. 2016. Capitalism, technology and a green global golden age: the role of history in helping to shape the future. BTTR Working Paper 2016-1.

- Piketty, T., and Saez, E., 2007. How progressive is the U.S. Federal tax system? A historical and international perspective. Journal of economic perspectives, 21 (1), 3–24.

- Pozsar, Z. 2014. Shadow banking: the money view. OFR Working Paper No. 14-04.

- Rey, H. 2015. Dilemma not trilemma: the global financial cycle and monetary policy independence. NBER Working Paper No. 21162.

- Rubin, R.E., et al. 1999. Hedge funds, leverage, and the lessons of long-term capital management. Report of The President’s Working Group on Financial Markets, April 1999.

- Ryoo, S., 2010. Long waves and short cycles in a model of endogenous financial fragility. Journal of economic behavior & organization, 74 (3), 163–186.

- Silvers, D., and Slavkin, H., 2009. The legacy of deregulation and the financial crisis: linkages between deregulation in labor markets, housing finance markets, and the broader financial markets. Journal of business & technology law, 4 (2), 301–347.

- Sissoko, C., 2019. Repurchase agreements and the (de)construction of financial markets. Economy and society, 48 (3), 315–341.

- Stedman Jones, D., 2014. Masters of the universe: Hayek, Friedman, and the birth of neoliberal politics. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Stockhammer, E., 2008. Some stylized facts on the finance-dominated accumulation regime. Competition & change, 12 (2), 184–202.

- Stockhammer, E., 2017. Wage-led versus profit-led demand: what have we learned? A Kaleckian–Minskyan view. Review of Keynesian economics, 5 (1), 25–42.

- Stockhammer, E., et al., 2019. Short and medium term financial-real cycles: an empirical assessment. Journal of international money and finance, 94, 81–96.

- Stockhammer, E., 2022. Post-Keynesian macroeconomic foundations for comparative political economy. Politics & society, 50 (1), 156–187.

- Strange, S., 1986. Casino capitalism. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Tew, B., 1977. The evolution of the international monetary system, 1945-77. London: Hutchinson.

- Thompson, H., 2009. The political origins of the financial crisis: the domestic and international politics of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. The political quarterly, 80 (1), 17–24.

- Tomlinson, J., 1987. Employment policy: the crucial years, 1939-1955. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Toporowski, J., 2000. The End of finance: The theory of capital market inflation, financial derivatives and pension fund capitalism. London: Routledge.

- van Treeck, T., 2009. A synthetic, stock-flow consistent macroeconomic model of 'financialisation'. Cambridge journal of economics, 33 (3), 467–493.

- Whalen, C., 2012. Money manager capitalism. In: J. Toporowski, and J. Michell, eds. The handbook of critical issues in finance. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Williamson, O.E., 1998. The institutions of governance. The American economic review, 88 (2), 75–79.

- Wray, L.R., 2011. Minsky's money manager capitalism and the global financial crisis. International journal of political economy, 40 (2), 5–20.

- Wray, L.R., and Tymoigne, E., 2009. Macroeconomics meets Hyman P. Minsky: the financial theory of investment. In: G. Fontana, and M. Setterfield, eds. Macroeconomic theory and macroeconomic pedagogy. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Appendix

Table A1. Variables and data sources used for the construction of the Macrofinancial Stability Index (MSI).