ABSTRACT

This paper analyses the political origins of diverse peripheral growth models in Europe, focusing on debt-based consumption-led growth model in Southern Europe and FDI-based export-led growth model in Central and Eastern Europe. Contrary to existing approaches that attribute this East-South divergence to their geographic position and systemic features of European monetary integration, the paper argues that these growth models stem from different national and EU-level policy responses to the challenge of core-periphery market integration. While the Southern states sought to protect domestic firms, allowing for, or even directly contributing to deindustrialisation in the face of competition with the European core economies, Central and East European states aimed to preserve their industrial legacy even at the expense of FDI-dependency. These policy responses were, in turn, shaped by distinct patterns of interaction and accommodation between segments of state elites and domestic economic groups, as well as by dramatically different EU strategies of governing integration. In contrast with society-centred perspectives on the politics of growth models, the paper highlights the autonomous role of the state as a key actor balancing between the demands and accommodation of domestic economic groups, and the constraints and opportunities created by regional institutions governing market integration.

Introduction

Comparative political economy has long dealt with capitalist diversity in Europe, the institutional and political origins of different models, and the possibility of their integration within the framework of a unified European market. More recent third-generation CPE scholarship tackles these questions using the growth models perspective and conceptualising capitalist diversity on the basis of different drivers of economic growth (Stockhammer et al. Citation2016, Baccaro et al. Citation2022). In contrast with other CPE approaches, growth models perspective has from its inception discussed the differences between core and peripheral capitalisms, and the distinct constraints of peripheral growth models. While export-led core economies operate with firms at the top of global value chains, peripheral export-led economies typically act as suppliers of labour or lower value-added parts of value chains. On the other hand, peripheral consumption-led growth models differ from their core counterparts in their ability to escape the balance of payments constraint, as a result of their lower position in the global financial hierarchy (Baccaro et al. Citation2022, Ban and Adascalitei Citation2022). Beyond such systemic constraints shared by all peripheral economies, the economic choices for European peripheries are considered to be further limited by EU-level institutions and actors that put weaker member states in a tight straightjacket of market pressures and macroeconomic conditions fostering export-led growth (Johnston and Regan Citation2018).

Despite such systemic limitations, peripheral economies in Europe (and in the Global South) display very different growth models, from dependent export-led models in Central and East European countries or export-led growth in Indonesia or Korea to dependent debt-driven model in the Baltics, debt-based and consumption-led growth model in the European South or consumption-led growth in Brazil or South Africa (Bohle Citation2018, Baccaro et al. Citation2022, Ban and Adascalitei Citation2022, Mertens et al. Citation2022). What explains such diversity? Is it merely the result of international economic constraints and/or strategies of the actors in the core countries, or is there scope for domestic political choices in the peripheries? Furthermore, do international constraints appear only in the form of systemic and structural pressures or do they depend on the institutional and political governance of economic integration?

This paper tackles these questions by analysing political origins of different peripheral growth models in Europe, and comparing, in particular, consumption-led growth model in Southern Europe and dependent export-led growth model in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE). Existing literature attributes this East-South diversity largely to systemic and structural features such as proximity to Germany and the expansion of German capital, which resulted in dependent export-led models in the East (Stockhammer et al. Citation2016, Bohle Citation2018, Ban and Adascalitei Citation2022) or the membership in the Eurozone which relaxed balance of payment constraints and contributed to consumption-led growth in the South (Johnston and Regan Citation2016, Baccaro et al. Citation2022). The politics of growth models is mainly discussed in order to explain national differences within peripheries, such as between Spain and Italy (Baccaro and Bulfone Citation2022) or between the Visegrad and the Baltics (Bohle Citation2018), while the East-South diversity is largely attributed to systemic factors such as geography, strategies of capital in the core countries, or monetary integration.

Contrary to such structuralist approaches, this paper argues that the diversity of peripheral capitalisms in Eastern and Southern Europe stems from the interaction of national and EU-level political choices made in the course of these countries’ integration into the European market. For both peripheries, the legacy of relative economic backwardness and lack of capital and technology represented similar challenges in the face of integration with the rich economies of the European core. Yet, their policy responses and growth strategies after democratisation were dramatically different. While the Southern states sought to protect domestic firms and strengthen national capital, allowing for or even fostering deindustrialisation, CEE states aimed to preserve their industrial legacy even at the expense of FDI-dependency. Such responses are, in turn, shaped by distinct patterns of interaction between state elites and domestic economic groups, as well as by divergent EU modes of governing integration (Bruszt and Vukov Citation2017), which left more space for the reproduction of existing coalitions and growth strategies in the South while fostering their transnationalisation in the East.

As the divergence of growth models between Visegrad and Baltic countries has been extensively analysed earlier (Bohle and Greskovits Citation2012, Bohle Citation2018), the paper focuses on a cross-regional comparison between Southern Europe (in particular Spain and Portugal) and the Visegrad countries (Poland, Hungary, Czech Republic and Slovakia). The paper combines the examination of macroeconomic drivers of growth with a comparative analysis of domestic and EU policies in the course of their European integration, tracing them from 1980s in the South and from 1990s in the East. While the focus is on the emergence of debt-based consumption-led vs. dependent export-led growth models as established and relatively stable types in South and East before 2008, the paper also discusses their most transformations after the Great Recession.

The paper makes three contributions. First, it contributes to the debates on the diversity of growth models in Europe, providing an account of the political origins of such diversity between the East and the South and thus complementing existing scholarship that focuses primarily on external and structural factors (Becker and Jäger Citation2012, Stockhammer et al. Citation2016). Secondly, the paper also adds to the discussion of the politics of growth models, which have focused primarily on social blocks, growth coalitions, or electoral politics in the case of advanced economies and European peripheries (Hall Citation2020, Baccaro et al. Citation2022, Baccaro and Bulfone Citation2022), or the autonomous role of the state in emerging market economies (Nölke Citation2020, Schedelik Citation2021, Mertens Citation2022). The analysis of Europe’s East and South, which would constitute advanced peripheries or semi-peripheries in the global economy, shows that it is the interaction and accommodation between relatively autonomous state elites on the one hand and domestic economic actors on the other that plays a key role in producing peripheral growth strategies, similar to what Bohle and Regan (Citation2021) find for Hungary and Ireland. At the same time the paper also shows that this domestic room for manoeuvre is decisively shaped by the policies and institutions at the international and particularly regional level. Contrary to the arguments that the EU primarily limits developmental options and fosters export-led growth (Johnston and Regan Citation2018), the paper shows that different EU policies and modes of governing integration create different opportunities and constraints for domestic agency and may foster both consumption-led and export-led growth models.

The paper proceeds as follows: after this introduction, the next section presents the diversity of peripheral growth models in Europe. The following two sections then discuss the politics of these growth models by linking them with different domestic approaches to the challenges of integration with the core, as well as with the specific forms of regional development governance in the EU. The final section concludes.

Peripheral diversity in Europe

Contrary to the supply-side institutions examined in the varieties of capitalism literature, growth models approach focuses primarily on the demand side and examines macroeconomic drivers of growth as the main aspect of capitalist diversity (Hassel and Palier Citation2021, Baccaro et al. Citation2022). Inspired by Kaleckian macroeconomics and regulation school, Baccaro et al. (Citation2022) argue that different countries found different solutions to the crisis of Fordism and the collapse of its wage-led growth, developing export-led, consumption-led, or balanced growth model, or alternatively failing to grow altogether.

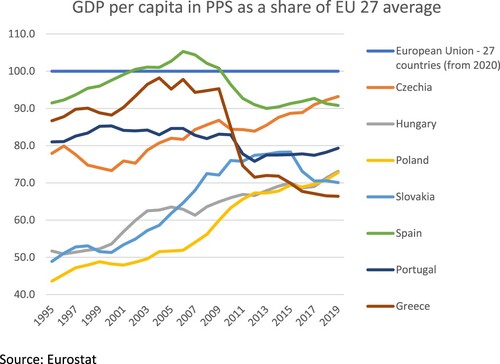

Southern Europe (Spain, Portugal, Greece) and CEE countries (Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland and Slovakia) in this framework present two very different growth models. Looking at their income levels in terms of GDP per capita (in PPS), it seems that they confirm the early prediction of Adam Przeworski: the East has become the South (Przeworski Citation1991). Starting from much lower income levels – at around 50 per cent of the EU-27 average in the mid-1990s – the East has today converged with the South at around 70–90 per cent of the EU-27 average income. The earlier Southern convergence towards the EU average has, on the other hand, been entirely erased by the Eurozone crisis ().

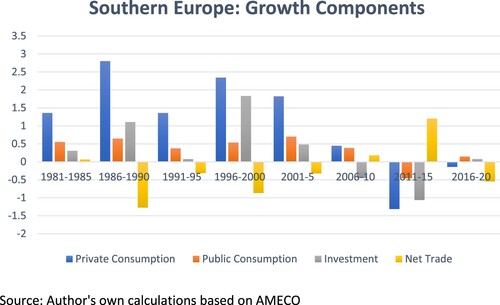

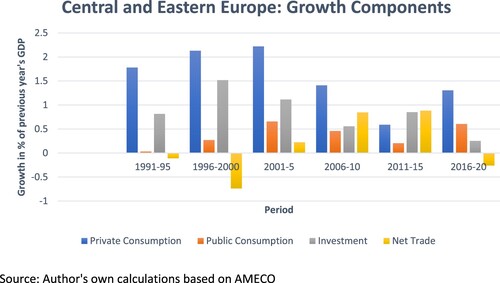

Despite this convergence in income levels, the drivers of economic growth in the East and the South have been dramatically different ().

Southern growth has been driven primarily by private consumption, with net trade having consistently negative contributions from the early 1980s till the Great Recession. This confirms the existing descriptions of the Southern consumption-led growth model (Hassel and Palier Citation2021, Baccaro et al. Citation2022). Yet, in contrast with the arguments attributing this model to monetary integration, it is evident that consumption-led growth emerges already with European market integration. The contribution of consumption to growth is actually stronger in the years immediately after the entry into the Single Market than it is upon the EMU entry. Following the Eurozone crisis, this tendency was briefly reversed with net trade turning positive due to the collapse of domestic demand. Yet it remains to be seen whether the shift from demand-led towards export-led or balanced growth in the South represents a more stable development.

Central and Eastern Europe on the other hand started with a similar consumption-led growth; yet from 2000s onwards they turned towards export-led growth ().

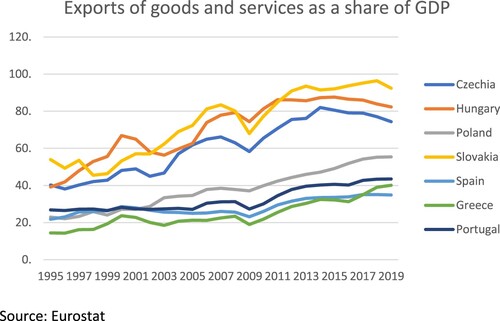

The contribution of exports to growth in this region is indeed positive and comparable to Germany, a paradigmatic case of export-led growth (see also Ban and Adascalitei Citation2022). As already noted in the literature, in comparison with Germany, private consumption plays a more important role in the East than it does in ‘high-quality manufacturing export-led regime’ (Hassel and Palier Citation2021). Nevertheless, when compared with Southern Europe, CEE exhibits much stronger export orientation. This is also confirmed by the data on the share of exports in GDP ().

An important feature that differentiates Eastern and Southern growth models from their counterparts in the core economies is their dependence on capital inflows from abroad. The two peripheries, however, exhibit dependence on different kinds of capital inflows: credit in the South and FDI in the East. Except for Hungary at the peak of the crisis, net external debt in the Visegrad never reached 40 per cent of GDP. In the South on the other hand, net debt before the crisis surpassed 50 per cent of GDP, only to skyrocket to above 90 per cent after the crisis. At the same time, CEE economies before the crisis displayed higher dependence on FDI inflows, with FDI stock surpassing 50 per cent of GDP in all of them except for Poland, and with all of them still having much higher shares of FDI than external debt in GDP. Spain and Portugal on the other hand caught up with such high levels of FDI only after the crisis, but they still rely more on net debt than FDI, whereas Greece continues to exhibit very low FDI dependence ().

Table 1. Capital inflows in Europe’s peripheries.

Overall, while income levels between the East and the South converged over time, their growth models have been markedly different: debt-based and consumption-led in the South until 2008, with varying levels of adjustment after the crisis, and FDI-dependent export-led growth model in the East. What explains this divergence? We turn to this in the following section.

The politics of growth strategies in the South and the East

In both Eastern and Southern Europe, democratic transition and European integration coincided with the collapse of their previous development models: import substitution industrialisation (ISI) in the South and socialist state-led industrialisation in the East. While different in many important features, in particular the lack of private property in the East, the two share many commonalities. They both emerged as a result of industrialisation efforts of authoritarian regimes, and they both relied on state involvement and protection of relatively closed inward-oriented economies, less developed and less competitive in comparison with the West.

Following the regime change, integration with the EEC / EU was in both regions seen as a way not only to consolidate their democratisation but also to overcome their economic backwardness. While the Southern states sought membership in the EEC already in the 1970s, to join in the 1980s, returning to Europe has been one of the main slogans of post-socialist transformations since the fall of the Berlin Wall. Beyond these broad goals, however, the key dilemma for policymakers in both regions has been how to survive integration with much richer and more developed economies of Northern / Western Europe. Outdated industrial structures and lack of capital and technology were among the key legacies of authoritarian modernisation. In the South, this was in some cases flanked with the presence of MNCs that established their operations already during dictatorship, whereas in the East technology was imported through licensing agreements and other forms of cooperation with Western firms (Pula Citation2018). Nevertheless, integrating into the Single Market with some of the most developed economies on Earth represented a great challenge for both regions, as entire firms and sectors could easily be wiped out when exposed to such competition.

Despite these similarities, their growth strategies after democratisation were dramatically different. Whereas the East adopted FDI-oriented policies as the key to their export-based growth strategy, the South opted for strengthening national firms in sectors providing services in the domestic market, while allowing for deindustrialisation and/or industrial stagnation. Below we outline the main features of these divergent strategies, focusing on Spain and Portugal in the South and the four Visegrad countries in the East. The countries are selected based on the diverse case method of case selection (Seawright and Gerring Citation2008), with the aim to represent typical cases within two peripheral growth models: consumption-led and dependent export-led model. Spain and Portugal represent consumption-led growth model that emerged after the transition from authoritarian ISI strategy (unlike Italy). At the same time, the two economies have not relied extensively on public debt and public consumption, in contrast with Greece, which is in the literature on the South usually depicted as exceptional in terms of its public debt and wage rises before the crisis (Perez Citation2019). The Visegrad countries are selected as typical representatives of dependent export-led growth model, which is how the literature consistently classifies them (Bohle Citation2018, Hassel and Palier Citation2021) although more recently Bulgaria and Romania are considered to belong to the same type (Ban and Adascalitei Citation2022).

Protecting domestic firms: selective liberalisation in the South

The policies of Southern states in the face of European integration represent a mix of liberalism and protectionism. While in Spain, such mix was apparent in different sets of policies towards different sectors, Portuguese strategy involved less sectoral differentiation and was rather based on more limited liberalisation across the board.

Spanish economic policies in the 1980s and 1990s could be described as unfettered liberalisation and closures in manufacturing sector, coupled with protectionism and strengthening of the financial sector, energy and utilities (Etchemendy Citation2011). Following the 1982 elections, the Spanish Partido Socialista Obrero Español (PSOE) embraced market liberalisation, and responsible monetary and fiscal policy as a key to Spanish adaptation to globalisation and European integration. The government engaged in industrial reconversion programme for its large tradable sectors, such as steel, shipbuilding or electronics. The programme involved mergers among domestic companies (private and public), followed by fast market liberalisation (Rand-Smith Citation1998, Etchemendy Citation2011). While restructuring involved deals with MNCs in the automotive industry, mergers and reorganisation of other sectors were linked with substantive capacity reduction rather than efforts at attracting foreign investors. As a result, state-led restructuring in Spain produced substantive deindustrialisation, with former industrial workers compensated primarily through generous welfare state programmes (Etchemendy Citation2011).

At the same time, Spanish policy towards banks, energy and telecommunications involved only limited liberalisation, with the protection of key domestic firms. The Spanish state engaged in activist industrial policy to turn domestic banks and utilities into European champions. It promoted sheltered consolidation among domestic firms, engaged in privatisation of state-owned companies oriented towards large domestic banks and used diplomatic channels to favour the internationalisation of Spanish firms both in Europe and in Latin America (Bulfone Citation2017). Liberalisation of the financial sector was only limited, protecting domestic banks (Perez Citation1997). Whereas in the negotiations for the EC entry Spain accepted fast liberalisation in industry with e.g. automotive industry receiving only three years to abandon all import restrictions, financial sector got seven years interim period in which the government could limit the entry of foreign banks (Perez Citation1997). Similarly, privatisation of energy and telecommunications resulted in large private monopolies with the state aiming to actively prevent foreign takeovers (Arocena Citation2004).

Furthermore, Spain engaged in large infrastructural projects boosting construction sector. Between 1995 and 2016, Spanish central and regional governments spent more than 80 billion EUR on infrastructure projects that were abandoned or underutilised (Romero Citation2018). Construction and real-estate boom were further strengthened by the transfer of control over savings banks (cajas) to the regional level in 1985, as well as the elimination of limitations on their operations in 1992. Together with the reforms of the urban planning during the PP government in the late 1990s, the reforms in the financial sector created a vicious circle in which cajas were encouraged to lend for real-estate projects and mortgages and to dramatically expand their operations. The regional governments responsible for their supervision engaged in political appointments of caja managers, resulting in dense corruption networks among banks, political elites and real-estate developers and fuelling real-estate bubble (Fernandez-Villaverde et al. Citation2013).

Overall, Spanish policies both under PSOE and under PP governments clearly favoured financial sector, construction, energy and utilities, while being much more uncompromising towards the manufacturing sector. The ground for the decline of tradable industries has thus been set before the EMU entry, with deindustrialisation in Spain starting already in the 1970s. While the shift from industry to services occurred throughout Europe in that period, deindustrialisation in Spain was also coupled with the dramatic rise of employment in construction, which increased by 40 per cent between mid-1970s and 2000 (Toharia Citation2000). As is documented in the literature, entry into the EMU exacerbated the problem by providing liquidity that fuelled construction and real-estate boom (Baccaro and Bulfone Citation2022). Nevertheless, the weakening of tradable industry and the strengthening of sectors focused on domestic demand started much earlier and were linked with specific policies of Spanish governments.

Such policies were in turn shaped by distinct ideas and policy goals of the Spanish state elites and their patterns of interaction with politically powerful economic groups. Within the state, the central intellectual role of the research service of the Central Bank, and the policy networks connecting the central bank and the government ensured the dominance of neoliberalism in Spanish economic policies (Ban Citation2016). More developmentalist or interventionist voices were side-lined already in the 1970s and even more so in the 1980s, with neoliberal orientation within PSOE (Perez Citation1997; Gillespie Citation1989). The government presiding over industrial restructuring saw large state-owned holdings as the remnants of authoritarian regime, in dire need of modernisation and liberalisation, and some of the leading policymakers were opposed to the idea of active state support for redeployment of resources from low to high value-added sectors (Rand-Smith Citation1998; Solchaga Citation1997). Domestic industrial bourgeoisie was very weak, and the policy of industrial reconversion did not encounter strong opposition from economic elites, while labour resistance was of little effect and mainly pacified through generous welfare programmes (Etchemendy Citation2011). In contrast with the weak industrial bourgeoisie, the power and political links of the banking and energy sectors are a long-standing feature of Spanish society, stemming already from the authoritarian regime. Such links were further secured through banks’ lending to political parties (Chari Citation1998), as well as through the interlocking directorates of large Spanish firms and the ‘revolving doors’ between public and private sectors. In addition to the finance and energy, from the early 1990s construction firms also became more prominent in interlocking directorates, by 2010 becoming the central sector (i.e. the one with the highest number of relationships with other sectors) in the network (Rubio-Mondejar and Garrues Irurzun Citation2016).

At the same time, the state did not merely respond to the interests of such actors but actively shaped their power and sought to reconcile their demands with its own policy goals. The state played an important role in reorganising the banking sector to prepare it for competition in the European market, as well as in preventing foreign entry, sometimes against the wishes of individual banks (Perez Citation1997). It was also instrumental in creating national champions in energy and telecommunication and helping their international expansion (Bulfone Citation2017). Furthermore, while early EMU entry benefitted domestic banks and construction sector, it was also seen as a strategic goal and a key part of the Spanish ‘return to Europe’ (Ban Citation2016). It was thus alliance and accommodation between politically powerful economic sectors such as finance and construction on the one hand, and neoliberal state elites and policy networks linked with the Central Bank on the other hand that produced a consumption-centred growth strategy.

In contrast with Spain, consumption-led growth in Portugal took the form of early boom followed by relatively slow growth from the early 2000s on. While this was accompanied by a reorientation of economic activity from tradable to non-tradable sectors (Lagoa Citation2013), the Portuguese path was not based on a real-estate bubble. Rather it was marked by stagnation of its manufacturing industry and declining total factor productivity associated with deteriorating current account balances. Already in 2000 current account deficit stood at 10 per cent of GDP. Many analysts attribute this to the combination of high capital inflows associated with the Eurozone, as well as the reluctance of domestic political elites to engage in ‘structural reforms’ (Fernandez-Villaverde et al. Citation2013). Yet, decline in total factor productivity growth occurred already since the 1973, driven by fall in industrial productivity (Lains Citation2002). The share of low-technology industries such as foodstuffs and textile increased, in particular between 1980 and 1990, while the share of more capital-intensive sectors declined.

In contrast with Spain, Portuguese strategy of adapting to integration with the EEC involved less sectoral differentiation and was rather based on a more limited liberalisation across the board. After nationalisations in the 1970s, Portuguese governments in the 1980s and 1990s engaged in large-scale privatisation of previously nationalised banks and industries, including energy, telecommunications and construction. Such privatisation was designed in a way to benefit domestic economic groups, with the explicit goal to create domestic capitalist class. In the words of Prime Minister Cavaco Silva: ‘We shall have to foster economic groups in Portugal. These were destroyed at the time of the revolution with nationalisation. We need them, as otherwise foreigners will come in and take over our enterprises and economic strategy will be determined from abroad. Thus we are supporting the new entrepreneurs in industry and agriculture.’ (Barrett Citation1988). The state thus invited previous owners and members of exiled Portuguese bourgeoisie to participate in privatisations (Nunes and Montanheiro Citation1997). Furthermore, liberalisation was limited and proceeded with generous compensation and guaranteed market shares to domestic incumbents (Marques Citation2015). The latter included strong local bourgeoisie with cross-sectoral industrial and financial holdings concentrated in a small number of families. Contrary to the Spanish state-led restructuring, which promoted redundancies and firm closures, Portuguese strategy involved more coordination with domestic business groups that were compensated primarily through protecting their market shares (Etchemendy Citation2011).

Like in Spain, low-interest rates associated with the Eurozone membership translated into easy borrowing for public and private actors. In Portugal, however, this resulted primarily in rising non-financial firms’ debt rather than household debt. While in 1995 total debt of non-financial firms amounted to 58 per cent of GDP and was within the range of the Euro average, by 2010, it represented 137.2 per cent of GDP, much higher than the EU average of 85 per cent (Lagoa Citation2013, p. 90). Such debt was further fuelled by the rise of public-private partnerships in infrastructure, or transport sectors, whereby the state was guaranteeing future payments while private firms were taking on debt against future income (Mortágua Citation2019). Once the crisis hit, non-performing loans rose particularly high in the non-financial firms’ sector, with construction and real estate particularly hard hit (Lagoa Citation2013).

The particular features of the Portuguese model marked by slow growth and declining productivity can be traced back to domestic coalitions and the interactions between state elites and dominant economic groups restored from the ISI period (Evans et al. Citation2019, Mortágua Citation2019). In contrast with strong state ownership in Spain, in Portugal ISI meant primarily the consolidation of the local industrial bourgeoisie, ‘the seven families’ with strong connections to the state, which extended their activity both in finance and in the industry (Etchemendy Citation2011). Each of them operated several manufacturing branches, controlled one or more banks and insurance companies, and was present in other service sectors, such as tourism and consultancy. While their power was curbed by the nationalisations following democratic transition in the mid-1970s, liberalisation and privatisation in the 1980s enabled these families to re-establish their position in the Portuguese economy (Weeks Citation2019). Fearing that integration with the EEC could lead to large foreign takeovers, the state explicitly aimed to create large domestic economic groups that could prevent such takeovers and that could compete in the European market.

Like Spain, Portuguese economic elite also showed signs of a tightly knit business community with close relations with politics and the prevalence of ‘revolving doors’ between government and business (Evans et al. Citation2019, Mortágua Citation2019). Furthermore, their operations were fundamentally dependent on different forms of protection by the government, such as for instance limiting the number of mobile providers or high energy prices (Marques Citation2015). Yet, in contrast with Spain, such business community displayed less sectoral specialisation, instead including cross-sectoral holdings. Their demands for protection were thus not focused on specific sectors and could instead be served by limited liberalisation across the board, allowing for industrial stagnation increasingly financed by foreign debt.

Both Spain and Portugal were hard hit by the 2008 financial crisis and forced to reconsider their growth strategies. With the bursting of the real-estate bubble and the collapse of domestic demand, the Spanish governments adopted reindustrialisation plans, with the aim to bring industry to 20 per cent of GDP. Both states also invested more resources in promoting tourism as an important source of growth and exports (Burgisser and Di Carlo Citation2023). Nevertheless, between 2016 and 2020 growth was still driven by other components: public consumption in Spain and a combination of private consumption and investments in Portugal.

Whereas growth strategy based on tourism was temporarily interrupted by the Covid-19 pandemic, the EU’s response to the pandemic has simultaneously opened up new opportunities for Southern states to re-shape their economic strategy through recovery and resilience plans (RRP). The plans indeed suggest a possible recalibration of earlier models and reorientation towards more complex and technology-intensive export-oriented sectors. The Spanish RRP, for instance, includes a public–private partnership with Volkswagen for the creation of a new battery factory and boosting of electric mobility (Feas and Steinberg Citation2021), while Portugal devotes 23 per cent of funds to smart and sustainable growth with the most important projects including alliances for business innovation and the creation of the national development bank (Corti Citation2022). Nevertheless, in both countries, the plans are likely to benefit primarily the sectors that were parts of previous growth alliances. The largest share of the Spanish RRP focuses on renewable energy sources and energy-efficient residential renovations, thus benefitting primarily energy and construction sectors. In Portugal, on the other hand, the largest share is devoted to the increase of the housing stock, with construction taking up 20 per cent of the allocated funds (Corti Citation2022). Thus, while both plans have the potential to increase the share of exports and go beyond tourism, such a change is nevertheless undertaken in a way that accommodates the interests of strong domestic groups.

Dependent reindustrialisation in the East

In contrast with the South, growth strategy in the Visegrad group relied strongly on reindustrialisation through manufacturing FDI, contributing to the emergence of dependent export-led growth (Ban and Adascalitei Citation2022). This strategy was not determined simply by their favourable socialist industrial legacies and the proximity to the German market. Instead, it emerged as a result of political conflict and contestation among different approaches to post-socialist development (Bohle and Greskovits Citation2012). With the exception of Hungary which opted for FDI early on, all the other Visegrad states initially attempted to build national capitalism and create a domestic capitalist class (Bohle and Greskovits Citation2012). To some extent, this mirrors the strategy of the Portuguese government, though with the important caveat that the domestic capitalist class in the East had to be created anew. Yet, by the end of the 1990s such attempts failed.

In the Czech Republic and Slovakia, the shift towards FDI attraction represented a policy U-turn at the background of economic crisis in the late 1990s, triggered by a combination of domestic weaknesses and the Asian and Russian financial crises. Despite important differences in the privatisation methods, newly created domestic capitalist class in both countries failed to restructure and upgrade existing enterprises (Gould Citation2011). In combination with increased trade integration with the EU, this resulted in high current account deficits and currency crises due to the balance of payments constraint. Thus both of them turned to FDI attraction as the main strategy to increase competitiveness (Vukov Citation2013). In Poland, on the other hand, FDI attraction emerged as a more gradual development whereby both state bureaucrats and domestic managers and trade unions increasingly perceived partnership with foreign investors as the best way to gain technology and maintain competitiveness (Ost Citation2005; Drahokoupil Citation2008; Markiewicz Citation2020).

What they all had in common – and in contrast with both Southern Europe and the Baltics – was a strong emphasis on maintaining and upgrading existing industrial legacies as a key aspect of their growth strategies (Bohle and Greskovits Citation2012). Similar to their Baltic counterparts, the Spanish state in the 1980s also perceived industrial legacies as the remnants of authoritarian regime that needed thorough downsizing. Portugal for its part largely left it in the hands of its powerful families to seek investment opportunities within their cross-sectoral ownership as they saw fit. Faced with increased competition in low-tech manufacturing on the one hand, and new opportunities in sheltered sectors such as infrastructure, construction and real estate, where they could rely on state support on the other hand, they opted for the latter (Mortágua Citation2019). The Visegrad states however prioritised maintaining and upgrading their manufacturing sectors. Once it became clear that the choice was between selling or simply letting go of domestic industrial capacities, their governments converged on the policy of selling ‘family silver’ to MNCs. They also actively engaged in attracting further, greenfield FDI in complex manufacturing sectors.

Such FDI attraction did not involve only the implementation of ‘structural reforms’, such as product or labour market liberalisation, or rationalisation of public administration, which were so often advocated as the solution to the problems of the Southern Europe. Instead, the Visegrad states created active industrial policies aimed at luring MNCs in complex manufacturing, including targeted investment incentives in the form of land and cash grants, tax credits and other forms of horizontal state aid (Bohle and Greskovits Citation2012). Whereas in 2007 such horizontal state aid in Poland or Czech Republic amounted to more than 0.70 per cent of GDP and in Hungary more than 1 per cent, the respective figures in Spain and Portugal were only 0.32 and 0.15 per cent of GDP (Vukov Citation2016). As a result, FDI in the East went primarily to complex manufacturing, such as automotive, or ICT, leading to export-led growth, unlike the South were most FDI went to the construction and real-estate sector.

The shift from national capitalisms to FDI-oriented policy appeared as a result of interaction between the state, domestic economic actors and multinational corporations (MNCs), and represented a deep reconfiguration of earlier political coalitions. In comparison with the South such coalitions were in Eastern Europe much more in flux, due to the weakness of domestic capital preceding the regime change. Nevertheless, in the first post-socialist years different countries created different winners from the first privatisation rounds. While in Hungary, this involved MNCs early on, in Poland privatisation further strengthened managers and employees of previously state-owned enterprises. Czech Republic and Slovakia were even more keen on building national capitalism, with Czech privatisation strengthening state-owned banks and a class of new entrepreneurs, and with Slovakia creating domestic capitalist class consisting of regime allies (Gould Citation2011). At the end of the 1990s, however, most of these domestic winners were side-lined and states engaged primarily in the creation of developmental alliances with transnational corporations. In Poland, bureaucrats in the Ministry of Economy identified strategic sectors that should receive foreign investment and cooperated with local management and labour in managing the insertion and upgrading of such sectors in the global market through FDI (Markiewicz Citation2020). In the Czech Republic the growth strategy based on attracting FDI in complex manufacturing emerged as a result of the rise of previously marginalised developmental institutions, including the investment promotion agency, as well as economists with more industrialist and neo-Keynesian approach (Vukov Citation2013).

While capitalists were thus largely state-made in the early 1990s, previous regime left the legacy of a large industrial working class. In contrast with the Baltics, Visegrad states could not simply neutralise labour’s demands through ethnic politics and disenfranchisement (Bohle and Greskovits Citation2012). Instead, they engaged in various forms of compensation. Similar to the South, this was partly done through various welfare state programmes (Bohle and Greskovits Citation2012). However, in contrast with the South, the main goal of the CEE states in the 1990s was keeping the enterprises or sectors alive rather than engaging in state-led consolidation and capacity reduction. Support for industry and firm restructuring were also among chief demands of trade unions in the 1990s (Ekiert and Kubik Citation2001). FDI attraction thus appeared a key way to save domestic industrial legacy, and to reduce the threat of even higher unemployment. In some countries, representatives of labour were directly involved in agreements with MNCs. In Poland, Solidarity participated in privatisation decisions, preventing privatisation to former communists and in many cases preferring foreign investors instead (Shields Citation2004). Stakeholders at the enterprise level, including both domestic management and trade unions also often sided with foreign investors (Ost Citation2005; Sznajder Lee Citation2016). In other countries, such as the Czech Republic, trade unions had less institutionalised voice at the national level; nevertheless they supported social democrats’ strategy of bringing in MNCs in complex industrial sectors (Vukov Citation2013). At the enterprise level, unions in firms such as Skoda or Slovak Volkswagen entered ‘productivity coalitions’, exchanging wage moderation in return for continuous future investments (Scepanovic Citation2013).

FDI attraction thus appeared as a result of an alliance between developmental (rather than neoliberal) state elites and domestic interests seeking to maintain industrial enterprises and make them competitive in the European market, even at the price of foreign ownership. In contrast with Spain or Portugal, the strategy of increasing national competitiveness did not mean creating domestic firms large enough to compete in the European market; rather competitiveness was understood in terms of competitiveness for attracting FDI. As will be shown in the next section, the possibility for protectionism and creating national champions in the East was foreclosed by a more interventionist EU governance of economic integration.

After the accession, however, the Eastern governments gained much more space for developmental experimentation, with some states using it for recalibrating their dependent growth model. While retaining the core of the model – export-oriented manufacturing FDI – Hungarian and Polish governments started to develop strategies for reducing dependency. In Hungary, such initiatives appeared due to the discontent of domestic capital and represented primarily the strengthening of domestic groups close to the right-wing government (Bohle and Greskovits Citation2018, Scheiring Citation2021). In Poland, they came about as a result of developmental agency of domestic managers of transnational corporations, in some cases acting in coordination with state institutions (Naczyk Citation2021). Czech Republic and Slovakia deviated very little from their previous growth models (Simons Citation2021). Whereas dependent export-led growth was thus not radically transformed, some of the Visegrad states still recalibrated it, incorporating elements of economic nationalism and strengthening domestic capital in banking and in sectors oriented towards the domestic market. Such heterodox policies as well as the internal variation among the Visegrad states in their strategies for managing dependency, were enabled by the much weaker ability of the EU to influence their strategies once these countries became full-fledged members of the EU. We turn to the role of the EU in the next section.

EU integration governance and peripheral growth models

The above section has argued that peripheral growth models can be linked with specific domestic political responses to the challenge of integration with the core countries, particularly during the EEC / EU accession. Yet, the space for such domestic responses was decisively shaped by the very different opportunities and constraints associated with divergent types of EU’s governance of economic integration

The Southern integration with the Single Market and later on the EMU was based only on arms-length EU management of integration (Bruszt and Vukov Citation2017). While there were concerns about developmental differences between the European North and the South, the predominant expectation was that market opening and the external anchor of the EMU will on their own provide incentives for Southern firms to upgrade their activities and for their states to engage in reforms fostering competitiveness (Delors Report Citation1989). Besides general macroeconomic conditions linked with the EMU accession, the EU largely left to national governments to deal with the challenges of integration with the core.

Contrary to these expectations, membership in the EMU insulated the Southern economies from the pressures of the international financial markets. The creation of the Eurozone resulted in low-interest rates and convergence in government bonds’ yields, while reducing country-specific factors in the pricing of corporate bonds (Lane Citation2006). Rather than pushing the public and private actors to adjust to the Single Market, the EMU provided them with easy access to finance and additional resources to maintain the status quo (Royo Citation2009, Fernandez-Villaverde et al. Citation2013; Vukov Citation2016).

The main EU measures to deal with Southern integration were the Structural Funds and the Cohesion Fund. These indeed represented sizeable resources for the South, which received much larger transfers than the East (Bruszt and Vukov Citation2017). Yet, the funds were left at the disposition of national governments and the states could use them largely as free rents for maintaining existing political coalitions. The Structural Funds were focused primarily on infrastructure projects. When contrasted with the actual developmental needs of the Southern economies, the funds appear as mis-allocated assistance (Medve-Balint Citation2018). Excessive infrastructure spending by Spanish governments (Romero Citation2018) or large public investments in Portugal were enabled by such generous EU support. Similar to the Eurozone effect, the Structural Funds thus merely provided further liquidity for strengthening domestic coalitions and compensating for the failure to deal with competitive challenges of integration.

EU policies of governing integration were much more intrusive and direct in the East (Bruszt and Vukov Citation2017). The European Commission developed a broader and less precise type of economic conditionality. In contrast with the Maastricht criteria for the EMU, Copenhagen criteria was not associated with precise macroeconomic indicators, leaving more space for the Commission to use its assessment of progress towards accession as quasi-legal coercion instruments (Medve-Balint Citation2014). The commission’s reports typically mentioned privatisation and FDI-openness in sectors such as banking, energy or telecommunications as key aspects of meeting accession criteria, thus pushing towards FDI-dependence also in sectors where some states like Poland would have preferred national ownership (Appel and Orenstein Citation2018). Whereas the Southern states could thus build national champions and help consolidation of national capital in banking, energy or telecommunications, such an option was foreclosed by stricter EU conditionality in the East.

While foreclosing protectionist strategies, the EU nevertheless went beyond simple demands for liberalisation and privatisation. Instead, it helped build developmental state capacities (Bruszt and Vukov Citation2017; Bruszt and Langbein Citation2020). The EU promoted domestic development banks (Piroska and Mero Citation2021), financed the establishment of investment promotion agencies and regional development agencies; and strengthened state-aid institutions instrumental for luring MNCs in complex sectors such as automotive or ICT (Vukov Citation2020).

All in all, once they opted for preserving industrial legacies, Visegrad states had much less space for policy differentiation than the Southern ones, at least before the EU accession. Divergence within the East was still possible, as attested by the differences between the Visegrad and the Baltic growth strategies (Bohle Citation2018). However, such divergence entailed only differences within deeply transnationalised capitalisms, while autonomous strategies based on national champions were off the table. Nevertheless, the EU engagement during the Eastern enlargement nurtured dependent development rather than locking these countries into low-value added peripheral position (Bruszt and Langbein Citation2020).

While the EU governance was initially more interventionist in the East than in the South, it has turned exactly the opposite after the Eurozone crisis. The EU crisis management has dramatically reduced the space for policy differentiation in the South with the constitutionalisation of budgetary constraints and with stringent conditionality attached to the financial bailout packages (Fabbrini Citation2016). At the same time, the scope for policy experimentation has greatly expanded in the East, as their membership has left the EU with little further instruments of either economic or political conditionality. As discussed earlier, some of the CEE states were able to use this space for economic nationalism and policies seeking to reduce their FDI dependency. Not only does the EU have little means to prevent such strategies, its cohesion funds may even provide additional resources strengthening such domestically oriented coalitions.

More recently, the EU’s response to the Covid-19 pandemic is likely to further amplify the scope for domestic agency and policy differentiation both in the East and in the South. While aiming to spur transformation towards green economy, Next Generation EU, at the same time, represents a new pool of resources that national governments can use either for upgrading and changing their growth strategies or for maintaining existing domestic alliances and conserving economic status quo. Which direction individual countries will take will depend primarily on their domestic political dynamics.

Conclusion

The above analysis identifies the political origins of capitalist diversity in Europe’s Eastern and Southern peripheries. In contrast with systemic and structuralist approaches, the paper shows how peripheral growth strategies emerge at the intersection of national and international / regional political dynamics. At the national level, the main mechanism behind different growth strategies lies in the patterns of interaction and accommodation between segments of state elites and domestic economic groups. Contrary to society-centred approaches that focus on growth coalitions (Baccaro et al. Citation2022, Baccaro and Bulfone Citation2022) or voters’ preferences (Hall Citation2020; Hopkin and Voss Citation2022) as the determinants of growth models in Europe, we argue that state elites in Europe’s peripheries should be seen as a relatively autonomous actor, rather than merely an executive arm of a growth coalition. While states respond to the demands of domestic economic groups, they also actively shape the power of such groups through (limited) liberalisation, the design of privatisation, or industrial policies strengthening specific segments of national capital or, alternatively, upgrading inherited industrial legacies and maintaining the pool of industrial working class. Furthermore, the state is also the key actor balancing between the demands and accommodation of domestic economic groups and the constraints and opportunities created by regional institutions governing market integration.

At the international / regional level, the main mechanism lies not simply in the market pressures on peripheral states and the depth of integration (market vs. monetary integration). As the analysis shows, consumption-led growth in the South emerged well before Eurozone membership, while Slovakia, as the only EMU-member in the Visegrad group continued its export-led growth after its Euro-entry in 2009. Instead, the key factor lies in the institutions and policies governing economic integration. In the case of Europe’s peripheries, the most important in this respect is certainly regional, i.e. EU-level institutions. Yet, contrary to the claims that the EU merely limits development options and imposes export-led growth, or that it turns peripheral states into colonies (as some politicians both in the East and in the South would claim), the EU can have very different effects, depending on the exact combinations of policies and institutions governing integration. At different points in time and in different peripheries, the EU has either narrowed down or increased space for policy experimentation, provided resources for maintaining pre-existing growth strategies, or spurred their transformation. It has also done so with varying implications for the development and upgrading in transnational value chains. Whereas such relevance of regional-level institutions is particularly pronounced in European peripheries, the study of growth models in emerging market economies could also benefit from examining not only domestic politics and international market pressures, but also the specific features of international institutions and policies governing core-periphery integration.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Appel, Hillary, and Orenstein, Mitchell A., 2018. From triumph to crisis. Neoliberal economic reform in postcommunist countries. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Arocena, P. 2004. Privatisation policy in Spain: stuck between liberalisation and the protection of nationals’ interests. CESifo Working Paper Series 1187, CESifo.

- Baccaro, L., Blyth, M., and Pontusson, J., 2022. Diminishing returns: the new politics of growth and stagnation. Oxford University Press.

- Baccaro, L., and Bulfone, F., 2022. Growth and stagnation in Southern Europe: The Italian and spanish growth models compared. In: L. Baccaro, M. Blyth, and J. Pontusson, eds. Diminishing returns: the new politics of growth and stagnation. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Ban, C. 2016. Ruling ideas: how global noeoliberalism goes local. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Ban, C., and Adascalitei, D., 2022. The FDI-led growth models of the east-central and south-eastern European periphery. In: L. Baccaro, M. Blyth, and J. Pontusson, eds. Diminishing returns: the new politics of growth and stagnation. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Barrett, M. 1988, September. Dedicated reformer. Euromoney, SS120+.

- Becker, J., and Jäger, J., 2012. Integration in crisis: a regulationist perspective on the interaction of European varieties of capitalism. Competition & Change, 16 (3), 169–87.

- Bohle, D., 2018. European integration, capitalist diversity and crises trajectories on Europe’s Eastern periphery. New Political Economy, 23 (2), 239–53.

- Bohle, D., and Greskovits, B., 2012. Capitalist diversity on Europe’s periphery. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Bohle, D., and Greskovits, B., 2018. Politicising embedded neoliberalism: continuity and change in Hungary’s development model. West European Politics. DOI:10.1080/01402382.2018.1511958.

- Bohle, D., and Regan, A., 2021. The comparative political economy of growth models: explaining the continuity of FDI-Led growth in Ireland and Hungary. Politics & Society, 49 (1), 75–106.

- Bruszt, L., and Vukov, V., 2017. Making states for the single market. European integration and the reshaping of economic states in the Southern and Eastern peripheries of Europe. West European Politics, 40 (4), 663–87.

- Bruszt, L., and Langbein, J., 2020. Manufacturing development: how transnational market integration shapes opportunities and capacities for development in Europe’s three peripheries. Review of International Political Economy, 27 (5), 996-1019

- Bulfone, F. 2017. The state strikes back: industrial policy, state power and the emergence of competitive multinational enterprises in Italy and Spain. PhD dissertation. Florence: European University Institute.

- Bürgisser, R., and Di Carlo, D., 2023. Blessing or curse? The rise of tourism-led growth in Europe's Southern Periphery. Journal of Common Market Studies, 61, 236– 258.

- Chari, R. S., 1998. Spanish socialists, privatising the right way? West European Politics, 21 (4), 163–179.

- Corti, F., et al. 2022. Comparing and assessing recovery and resilience plans. Paper RRP 7, Center for European Policy Studies. March 2022.

- Delors Report. 1989. Report on economic and monetary union in the European community. (Committee for the Study of Economic and Monetary Union). Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the EC.

- Drahokoupil, J., 2008. Globalization and the state in central and Eastern Europe: the politics of foreign direct investment. London: Routledge.

- Ekiert, G., and Kubik, J., 2001. Rebellious civil society: popular protest and democratic consolidation in Poland, 1989-1993. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Etchemendy, S., 2011. Models of economic liberalization: business, workers, and compensation in Latin America, Spain, and Portugal. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Evans, A.M., Verga Matos, P., and Santos, V., 2019. The state as a large-scale aggregator: statist neoliberalism and waste management in Portugal. Contemporary Politics, 25 (3), 353–72.

- Fabbrini, F., 2016. Economic governance in Europe: comparative paradoxes and constitutional challenges. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Feas, E., and Steinberg, F., 2021. The climate and energy transition component of the Spanish national recovery and resilience plan. Madrid: Real Institute Elcano.

- Fernandez-Villaverde, J., Garicano, L., and Tano Santos, T., 2013. Political credit cycles: the case of the eurozone. Journal of Economic Perspectives, American Economic Association, 27 (3), 145–66.

- Gillespie, R., 1989. The spanish socialist party: A history of factionalism. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Gould, J. A., 2011. The politics of privatization. Wealth and power in post-communist Europe. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

- Hall, P., 2020. The electoral politics of growth regimes. Perspectives on Politics, 18 (1), 185–99.

- Hassel, A., and Palier, B., 2021. Growth and welfare in advanced capitalist economies: how have growth regimes evolved? Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hopkin, J., and Voss, D., 2022. Political parties and growth models. In: L. Baccaro, M. Blyth, and J. Pontusson, eds. Diminishing returns: the new politics of growth and stagnation. Oxford: Oxford University Press

- Johnston, A., and Regan, A., 2016. European monetary integration and the incompatibility of national varieties of capitalism. Journal of Common Market Studies, 54 (2), 318–36.

- Johnston, A., and Regan, A., 2018. Introduction: Is the European union capable of integrating diverse models of capitalism? New Political Economy, 23 (2), 145–59.

- Lagoa, S., et al. 2013. Report of the Financial System in Portugal, FESSUD Studies in Financial Systems N° 9, Leeds.

- Lains, P. 2002. ‘Why growth rates differ in the long run: capital deepening, productivity growth and structural change in Portugal, 1910-1990’ Paper presented at the Conference on ‘Desenvolvimento económico português no espaço europeu: determinantes e políticas’, Banco de Portugal, 2002.

- Lane, P., 2006. The real effects of European monetary union. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 20 (4), 47–66.

- Markiewicz, O., 2020. Stuck in second gear? EU integration and the evolution of Poland’s automotive industry. Review of International Political Economy, 27 (5), 1147-1169.

- Marques, P., 2015. Why did the Portuguese economy stop converging with the OECD? institutions, politics and innovation. Journal of Economic Geography, 15, 1009–31.

- Medve-Balint, G., 2014. The role of the EU in shaping FDI flows to east central Europe. Journal of Common Market Studies, 52 (1), 35–51.

- Medve-Balint, G., 2018. The cohesion policy on the EU’s eastern and southern periphery: misallocated funds? Studies in Comparative International Development, 53 (2), 218–38.

- Mertens, D., et al. 2022. Moving the center: adapting the toolbox of growth model research to emerging capitalist economies. Working Paper, No. 188/2022, Hochschule für Wirtschaft und Recht Berlin, Institute for International Political Economy (IPE), Berlin.

- Mortágua, M.R. 2019. Capital accumulation and stagnation: a Veblenian-Kaleckian approach to the portuguese lost decade. PhD thesis. SOAS University of London.

- Naczyk, M., 2021. Taking back control: comprador bankers and managerial developmentalism in Poland. Review of International Political Economy. DOI:10.1080/09692290.2021.1924831.

- Nölke, A., et al., 2020. State permeated capitalism in large emerging economies. London: Routledge.

- Nunes, J., and Montanheiro, L., 1997. Privatisation in Portugal: an insight into the effects of a new political strategy. Competitiveness Review, 7 (2), 59–78.

- Ost, D., 2005. The defeat of Solidarity: anger and politics in postcommunist Europe. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Perez, S., 1997. Banking on privilege: the politics of Spanish financial reform. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Perez, S., 2019. A Europe of creditor and debtor states: explaining the north/south divide in the Eurozone. West European Politics. DOI: 10.1080/01402382.2019.1573403.

- Przeworski, A., 1991. The “East” becomes the “South”? The “Autumn of the People” and the future of Eastern Europe. Political Science and Politics, 24 (1), 20–24.

- Piroska, D., and Mero, K., 2021. Managing the contradictions of development finance in the EU’s Eastern periphery development banks in Hungary and Poland. In: Mertens et al. eds. The Reinvention of development banking in the European Union. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 224-252.

- Pula, B., 2018. Globalization under and after socialism: the evolution of transnational capital in central and Eastern Europe. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Rand-Smith, W., 1998. The left’s dirty job: the politics of industrial restructuring in France and Spain. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press.

- Romero, J., et al., 2018. Aproximáción a la Geografía del despilfarro en España: balance de las últimas dos décadas. Boletín de la Asociación de Geógrafos Españoles, 77, 1–51.

- Royo, S., 2009. After the Fiesta: the Spanish economy meets the global financial crisis. South European Society and Politics, 14 (1), 19–34.

- Rubio-Mondejar, J., and Garrués-Irurzun, J., 2016. Economic and social power in Spain: corporate networks of banks, utilities and other large companies (1917–2009). Business History, 58 (6), 858–79.

- Scepanovic, V. 2013. FDI as a solution to the challenges of late development: catch-up without convergence? PhD thesis. Budapest: Central European University.

- Schedelik, M., et al., 2021. Comparative capitalism, growth models and emerging markets: the development of the field. New Political Economy, 26 (4), 514–26.

- Scheiring, G., 2021. Dependent development and authoritarian state capitalism: democratic backsliding and the rise of the accumulative state in Hungary. Geoforum, 124, 267–78.

- Seawright, J., and Gerring, J., 2008. Case selection techniques in case study research: a menu of qualitative and quantitative options. Political Research Quarterly, 61 (2), 294–308.

- Shields, S., 2004. Global restructuring and the Polish state: transition, transformation, or transnationalization? Review of International Political Economy, 11 (1), 132-154.

- Simons, J.P. 2021. Dealing with dependency differently: the political economy of policy deviations in the Visegráds. PhD Thesis. Florence: European University Institute.

- Solchaga, C., 1997. El final de la edad dorada. Madrid: Taurus.

- Stockhammer, E., Cedric, D., and List, L., 2016. European growth models and working class restructuring: an international post-Keynesian political economy perspective. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 48 (9), 1804–28.

- Sznajder Lee, A., 2016. Transnational capitalism in East Central Europés heavy industry: from flagship enterprises to subsidiaries. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Toharia, L., 2000. Employment patterns in Spain between 1970 and 2001. International Journal of Political Economy, 30 (2), 82–98.

- Vukov, V. 2013. Competition states on Europe’s periphery: race to the bottom and to the top. PhD dissertation. Florence: European University Institute.

- Vukov, V., 2016. The rise of the Competition State? Transnationalization and state transformations in Europe. Comparative European Politics 14 (5): 523–546.

- Vukov, V., 2020. More Catholic than the Pope? Europeanisation, industrial policy and transnationalised capitalism in Eastern Europe. Journal of European Public Policy, 27 (10), 1546–64.

- Weeks, S., 2019. Portugal in ruins: from ‘Europe’ to crisis and austerity. Review of Radical Political Economics, 50 (2), 246–64.