ABSTRACT

The financial crisis that hit the Eurozone in 2010 drove a number of its members request assistance from their EU partners. The reaction to these requests at the European level came in coordination with the IMF, but not necessarily in a uniform manner. This article compares the adjustment programmes of Ireland and Cyprus. Despite their similarity on the independent variable (local economic conditions), the design of the Irish and Cypriot programmes (the dependent variable) differed fundamentally, not least because of the introduction of the bail-in clause in Cyprus, involving direct loses for depositors. This article seeks to explain how this key policy departure came to be and what were the conditions that made its introduction possible by examining the temporal evolution of the crisis response and focusing in particular on four explanatory themes: (i) time as a negotiating (dis)advantage; (ii) time as a platform for policy learning; (iii) time as a justifier of past policy choices (path dependency) and (iv) time as a signifier of future policy choices (path setting).

Introduction

The economic rescue packages agreed in the context of the Eurozone (EZ) crisis have been some of the most hotly contested episodes in the recent history of European integration. Naturally, the scholarly attention they have received has been vast and multi-disciplinary (e.g. Hall Citation2014), involving normative (e.g. Schmidt Citation2013, Vaara Citation2014) and policy interpretations (e.g. Pisani-Ferry Citation2011, Drezner Citation2014, Henning Citation2017) as well as accounts of its main protagonists (e.g. Van Rompuy Citation2014, Papaconstantinou Citation2016, Dijsselbloem Citation2018). The literature on the interaction of individual recipient countries with their creditors has also been substantial, albeit disproportionately focused on Greece, as the most emblematic test case of the crisis (e.g. Featherstone Citation2011, Pelagidis and Mitsopoulos Citation2014). By contrast, comparative work on the crisis has been more limited (though see Moury Citation2021, Morlino and Sottilotta Citation2019), as indeed have ‘longitudinal’ studies that traced policy developments from the outset of the crisis until its ‘formal’ ending in July 2018 with the conclusion of Greece’s third programme (Riddervold et al. Citation2020).

The mosaic of the current bailout literature is the product of the extraordinary complexity, duration and murti-dimensionality of the crisis. The elaboration and execution of bailout programmes were not simply self-contained, time specific, episodes of intensive negotiation between lenders and borrowers couched simply on national specificities. Throughout its duration, the crisis involved four ‘formal’ recipients (Greece, Ireland, Portugal and Cyprus), six different programmes (Greece having signed three), a Financial Sector Adjustment Programme for Spain targeting the recapitalisation and restructuring of the country’s financial sector and substantial interventions in Italy which did not involve a formal ‘programme’, but required a specific set of mutual obligations. The audience addressed by these bailout programmes went well beyond those ‘rescued’. It involved the financial markets, member governments of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and, crucially, other members of the EZ who had high stakes in the crisis, either as contributors of finance or as potential recipients of bailout support if the crisis worsened.

In this context the management of the crisis is best understood as a set of iterated games (Axelrod Citation1981, Citation1990), building on existing policy legacies (either from the very first Greek bailout or previous interventions of the IMF around the world), an acute current predicament (evident by money ‘running out’ in debtor countries) and a need to avoid (or at least be better prepared for) a future iteration of the crisis. Policy learning by those managing the crisis was another key component of the story. It is a well-established fact that the outbreak of the crisis caught the EU unprepared both in terms of its financing instruments and its institutional capability to oversee the conditionalities attached to the programmes. The very make-up of the Troika (the International Monetary Fund, the European Central Bank and the European Commission) was a reflection of these deficiencies. As the initial shock of Greece’s financial implosion gave way to contagion and a more systemic crisis threatening the survival of the Euro, the need to reassure and lead policy development became critical. In this environment of ‘learning by doing’ against a rapidly changing landscape, time became a crucial resource.

In this article we seek to articulate the importance of time as a determinant of crisis response in two cases, Ireland and Cyprus, focusing, in particular, on the design of their respective programmes (from the Irish ‘bailout’ to the Cypriot ‘bail in’). Ireland became the second EZ member to sign a programme when it did so in November 2010, whereas Cyprus was the last when it concluded the EZ’s penultimate deal in March 2013. Although we relate ‘time’ to the way in which both recipient countries developed their negotiating strategies, the focus of our analysis rests primarily on how the iterated nature of the bailout game(s) affected ideational shifts and policy learning on the side of key creditors. In doing so, we build on an extensive corpus of primary and secondary literature on the EZ crisis, including a number of semi structured interviews with Irish, Cypriot and EU policy makers in Brussels and Nicosia (Appendix A).

The selection of case studies is based on a ‘most similar case’ design. Indeed, the political economy outlook of both countries shared many similarities, broadly corresponding to that of a Liberal Market Economy (LME) (Hall and Soskice Citation2001). Notwithstanding the idiosyncrasies of the two case studies (e.g. Chari and Bernhagen Citation2011 and Pegasiou Citation2013) and the boarder critique of Varieties of Capitalism as a comparative frame (e.g. Hay Citation2020), Ireland and Cyprus shared a similar trajectory of economic development in the run-up to the crisis, based on an oversized financial sector (Sepos Citation2008, Donovan and Murphy Citation2013, Interview No. 5). The same is also true of the way in which the crisis ‘hit home’, primarily as a banking collapse which then fuelled a deterioration of state finances.

Yet, for all the similarity on the independent variable (local economic conditions), the design of their respective programmes (our dependent variable) differed in one fundamental way. Whereas in the Irish case the cost of recapitalising failing banks was borne by the state, the Cypriot one introduced the principle of ‘bail in’, whereby the cost of bank failure hit depositors and private investors as well. In the analysis that follows we seek to explain how this key policy departure came to be and what were the conditions that made its introduction possible. We are primarily concerned with the temporal evolution of the EZ crisis response, focusing in particular on four explanatory themes: (i) time as a negotiating (dis)advantage; (ii) time as a platform for policy learning; (iii) time as a justifier of past policy choices (‘path dependency’) and (iv) time as a signifier of future policy choices (‘path setting’). Our focus on temporality should not be seen as a competing interpretation to approaches focusing on actor interests, overarching crisis management narratives or the institutional mediation of the bailout negotiations. Instead, we posit that temporality can offer a conceptual anchor upon which such interpretations can be better contextualised and understood.

The article proceeds as follows: the first section reviews the theoretical literature on temporality and path dependency in public policy. The second section recounts the trajectory of the Irish and Cypriot recourse to their creditors and reviews the key provisions of their respective programmes. The third section elaborates on the temporal dimensions that facilitated the introduction of the ‘bail in’ clause in the Cypriot programme. Finally, the conclusion returns to the key contribution of the article and identifies further research agendas for a more fulsome understanding of the events that shook the system of economic and monetary management within the EZ.

Setting the frame: temporality, policy learning and path dependency

The negotiation of the bailout programmes entailed the inherent power asymmetry in the relationship between creditor and debtor states. This asymmetry was further accentuated by the fact that all bailout recipients were medium or small size economies, albeit with a potential to contaminate larger sections of the EZ economy (Dyson Citation2010, Donnelly Citation2014, Armingeon and Cranmer Citation2018). Naturally, the EZ was at its most vulnerable at the very beginning of the crisis when it lacked the institutional tools and financial instruments to respond to the crisis and when the fear of contagion was most widespread. Yet, these vulnerabilities could have only been exploited in the context of a ‘suicide bomber’s’ strategy whereby damage to the EZ could only be threatened by debtor nations at the expense of economic self-inhalation. Since such a strategy was explicitly dismissed by all debtor nations (expect by the Tsipras government in Greece in 2015), the ‘lock in’ of this power asymmetry must be treated as a common feature in the negotiation of both the Irish and the Cypriot programme.

In this context, the instrumentalisation of time as an advantage in the hands of bailout negotiators forms an important part of the EZ crisis management. More relevant for our analysis here is the effect of time on the articulation of policy problems and associated solutions. At a very basic level the impact of time on policy development can be understood within a bipolar of theoretical expectations: on the one hand the Historical Institutionalist tradition, with its emphasis on ‘stickiness’ and path dependence (Steinmo et al. Citation1992, Thelen Citation1999, Pierson Citation2004) and on the other, theoretical frames highlighting learning and opportunity structures that encourage policy recalibration and innovation (Dunlop and Radaelli Citation2013, Kingdon Citation1984). Although we recognise that the underlying logic of each approach is distinct, we maintain that their relevance in explaining policy choices in a rapidly evolving crisis should not be seen as mutually exclusive, not least in the context of the inductive inquiry pursued in this article.

Indeed, the temporal dimension in public policy research has been highlighted in the work of Pierson (Citation2000, Citation2004) who warned of the dangers of viewing policy development through a series of static snapshots. In his view, the key to analytical rigour rests on the examination of 'not just what happened, but when it happened too’ (Pierson Citation2000). In a similar vein, Pralle (Citation2006) argued that our understanding of ‘events’, ‘policy venues’ and ‘external shocks’ in their temporal dimension may be as important as identifying them in the first place. In sum, settings where event A precedes event B will generate different outcomes than ones where the ordering is reversed.

For Pierson (Citation2004), ‘timing’ and ‘sequencing’ create the essential connectivity between actions that helps us explain why certain forms of policy change happen at a particular time and place. The two terms are not mutually exclusive, but work in a complementary fashion. ‘Timing’ focuses on conjunctures which refer to the effects of interaction between distinct causal sequences that become joined at particular points in time and the results may be different than when these sequences are temporally separated. Similarly, Kingdon (Citation1984) refers to policy windows where policy change may come about when three independent streams – problems, politics, and policies – connect. The problem stream refers essentially to policy problems that require government/state action to be resolved, the policy stream pertains to the conceptualisation and proposal of policy solutions that originate with communities of policy makers, experts and lobby groups; and the politics stream refers to factors that are of a political nature (such as changes in government, legislative turnover and fluctuations in public opinion) and may initiate a momentum to induce change.

Policy windows resemble what Bulmer and Burch (Citation2001) termed critical moments. These are conjunctures in time which provide space for a radical departure of policy paradigms, creating new path dependencies (Capoccia and Kelemen Citation2007). Under conditions of acute crisis such path dependencies can become an important resource for establishing ‘credibility’ and mitigating uncertainty. Conversely, moments of crisis shake the status quo and may lead policy makers to take corrective action on existing policy paths or seek to create new ones which, they regard, as better suited to fight future iterations of the crisis.

Inherent in this logic of change is the concept of policy learning and lesson drawing. Dunlop and Radaelli (Citation2013, p. 599) define learning as ‘the updating of beliefs based on lived or witnessed experiences, analysis or social interaction’ and its subsequent instrumentalisation by policy actors. Rose (Citation1991, p. 7) defines lesson-drawing as instructive knowledge and an action-oriented conclusion about a programme in a different location and/or time. Importantly, lesson-drawing may occur though both positive and negative evaluation of policy performance, steering future choices in a way in which to avoid failure or replicate success (Rose Citation1991, Pierson Citation2000). Dolowitz and Marsh (Citation2000) remind us that the way in which knowledge and lesson drawing find their way into international policy transfer is not always easily detectable. Neither is it an entirely voluntary exercise on behalf of the ‘recipient’. The temporality of how such policy learning was acquired by EZ policy makers and the way in which it was transferred to debtor countries (through a mix of cooperation and coercion) form an important part of our analysis of how the design of the Irish and Cypriot programmes came to be decided.

Similar problems, different solutions?

From boom to bust

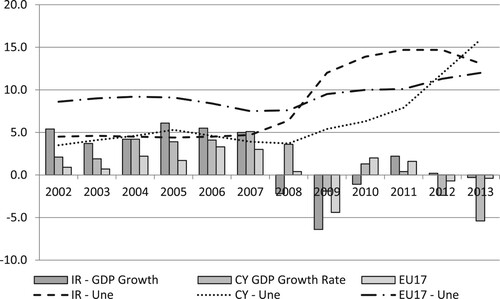

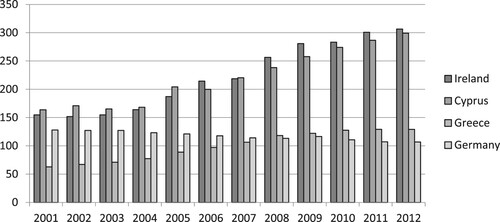

The economic success of both Ireland and Cyprus in the years preceding the crisis has been inextricably linked to their EU membership, allowing them to emerge as major international financial centres in the EZ, sustaining much higher growth rates (and lower unemployment) than their EU partners (). Both countries experienced a substantial credit boom in the aftermath of their membership of the EZ (Dellepiane-Avellaneda et al. Citation2022). For Ireland, this manifested in the rapid expansion of the construction industry and soaring property prices (Chari and Bernhagen Citation2011, Whelan Citation2014, Interviews 6 and 7). In Cyprus, the previously government-controlled financial sector liberalised rapidly, but without sufficient regulatory oversight (ICFCBS Citation2013, p. 22, Interview No. 10). In this context, local banks built up reserves from the non-resident segment of depositors, allowing the financial sector to double in size during the pre-euro accession phase, ultimately becoming disproportionately large compared to other European countries (European Commission (EC) Citation2013, p. 11) ().

Table 1. Size of banking sector: Total assets of credit institutions as percentage to GDP (2009).

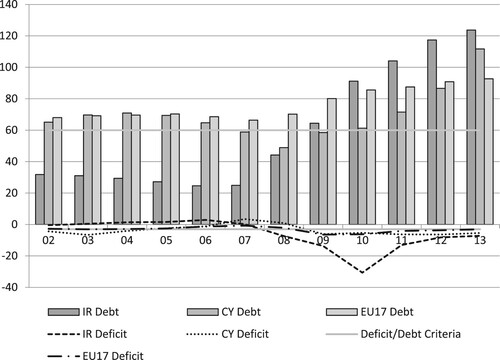

Although neither Cyprus, nor Ireland experienced significant levels of public debt or budget deficit in the run up to the crisis, both countries witnessed a ballooning of private debt, which almost doubled in the preceding decade ( and )

In search of rescue

According to the EC (Citation2011), from late 2007, investor confidence in Ireland’s property sector was shaking in response to an oversupply and a price bubble that was set to burst. A significant fall in cyclical construction-related revenues and losses in the domestic banking system were aggravated by global developments and events unfolding in the US. Although not directly exposed to the US subprime mortgage market collapse, Irish banks began to experience acute liquidity constraints and difficulties in acquiring external funding. The resulting financial unrest triggered an outflow of deposits leading the Irish government, on 30 September 2008, to issue a two-year guarantee against all bank liabilities, covered bonds, senior debt and dated subordinated debt (lower tier II), so as to restore stability in the banking sector (Government of Ireland Citation2008). The scope of the guarantee was exceptionally broad with a potential cost of 400 billion euro (close to three times the country’s GDP), casting doubts over the ability of the government to honour such a commitment. Private creditors were essentially insulated from incurring any losses through a ‘forced’ contribution to the recapitalisation of banks, thus shifting the burden exclusively on the government’s finances (Whelan Citation2014, ).

Table 2. From Bailout to Bail In: a timeline of events.

As the situation worsened, the Irish government was ultimately forced to initiate the nationalisation of its banking sector. In January 2009, the Anglo-Irish Bank (the country’s 3rd largest lender) was the first to be nationalised at a cost close to €100bn and subsequently the cost of recapitalising Irish banks grew beyond all expectations, reaching some 46bn (29 per cent of GDP) over the period 2009–2010 (EC Citation2011, p. 13). This had a detrimental effect on the state’s finances and in 2010 the budget deficit of Ireland reached extraordinarily high levels, exceeding 30 per cent of GDP ().

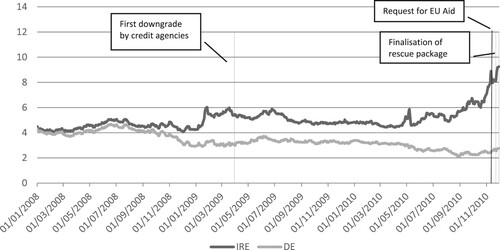

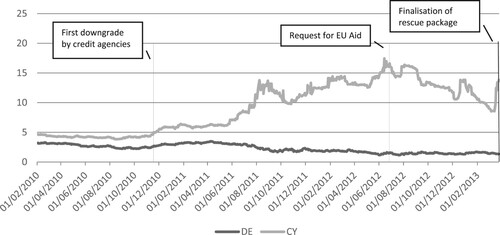

As financial markets remained unconvinced about the Greek rescue package agreed in April 2010, confidence in the Irish economy began to deplete further. In addition, the Deauville Declaration of 18 October 2010, agreed between Germany and France, essentially allowed for losses to be imposed on private creditors in any future rescue of a EZ country or a financial institution. However, with the EU lacking the means to carry out such a radical plan, the immediate effect of Deauville was the dramatic increase of bond yields on sovereign debt () (Djankov Citation2014). Furthermore, as the Irish economy continued to contract () a sharp rise of non-performing loans was recorded (), initiating a vicious circle between national and private debt.

Table 3. Bank non-performing loans to total gross loans (%).

Despite implementing spending cuts worth €14.6 billion (equivalent to 9 per cent of GDP) in 2008 and 2009, the Irish government began to run out of options by late 2010 (EC Citation2015, p. 63). In November that year, in a secret letter by ECB President Jean-Claude Trichet to the then finance minister Brian Lenihan, it was made clear that the ECB would only agree to continue its €140 billion (equivalent to 85 per cent of Irish GDP) of Emergency Liquidity Assistance (ELA) to Irish banks, if it received ‘a commitment in writing’ that the Irish government would immediately apply for a bailout.Footnote1 Faced with no alternative, the main political parties in Ireland backed the government’s request for an external rescue on 21 November 2010 and within days the final agreement between Troika representatives and state officials was concluded (Hardiman Citation2019, Donovan and Murphy Citation2013, p. 239, Interviews No. 1, 7 and 8).

Although Cyprus was the last EZ member to ask for a bailout in 2013, its financial predicament had been evident long before, when consecutive downgrades by international credit rating agencies cut off the country from the markets since May 2011. Greece’s harsh treatment in the hands of its creditors casted a heavy shadow on policy makers in Nicosia. Against this backdrop, a bilateral €2.5 billion loan from Russia was finalised in December 2011, as an alternative to applying for financial help to the Troika. The deal gave the government in Nicosia some breathing space, but not for long. The Private Sector Involvement (PSI), agreed as part of the second Greek rescue plan in October 2011 and finalised in February 2012, inflicted massive losses on the country’s largest banks, Laiki and the Bank of Cyprus.

By late June 2012, Fitch became the last of the major credit agencies to downgrade Cyprus to junk status and, subsequently, Cypriot government bonds ceased to be accepted as collateral by the ECB for monetary policy operations. In this context, the Cypriot Central Bank Governor impressed upon the President of the Republic that if the government did not apply for a bailout, the ECB would not be able to supply ELA to Laiki and plans for recapitalisation of the entire banking sector would be left in limbo (Demetriades Citation2017, p. 46). Faced with the imminent collapse of the country’s second largest bank, Laiki, President Christofias made an official request for Troika support on 25 June 2012, allowing his government to recapitalise Laiki to the tune of €1.8 billion.

Ahead of concluding the terms of its bailout with the creditors, the Cypriot government had already taken steps on fiscal consolidation, equivalent to 7 per cent of GDP for 2012–2014 (EC Citation2019, p. 40). Yet, negotiations on the adjustment programme progressed at a very slow pace and were eventually caught up in the presidential election campaign of February 2013. The Cypriot MoU was finally signed in March 2013 (), amidst huge EU pressure on the newly-elected Cypriot President, Nicos Anastasides (leader of centre-right DISY) and a toxic political climate both at home and in Brussels.

The greatest innovation introduced in the Cypriot programme was undoubtedly the ‘bail in’ principle. While prior to the presidential election, Anastasiades had publicly committed to never agree to such a principle, when in office he was forced into a U-turn. Again, the role of the ECB in bringing things to an end was decisive since its officials threatened to cut off ELA to Cypriot banks if a ‘deposit haircut’ was not accepted (Demetriades Citation2017, pp. 33–4, Interview No. 3). The ECB Governing Council set a deadline of 25 March 2013 for the deal to be concluded, declaring that ‘thereafter, ELA could only be considered if an EU/IMF programme was in place that would ensure the solvency of the concerned banks’ (Engelen Citation2013, p. 76). At the time, ELA had reached €9.1 billion for Laiki Bank compared to €300 million in September 2011 (Zenios Citation2016).

As part of the deal, deposits above €100,000 at Laiki Bank were confiscated while, additionally, for the Bank of Cyprus, the nation’s biggest lender, the final percentage of eligible deposits converted to equity was 47.5 per cent. Laiki was dissolved into a bad bank, with its main assets (including its ELA commitments) being transferred to the Bank of Cyprus. The downsizing of the banking sector also included the disposal of banking operations of the Cypriot banks in Greece (as a buffer to contagion between the two economies). This was accompanied by restrictive capital measures, to prevent an outflow of remaining deposits.

With the apparent exception of the ‘bail-in’ provision, the terms of the Irish and Cypriot bailout programmes were rather similar. They included a strict fiscal consolidation timetable (bringing the budget deficit under 3 per cent of GDP); a 2.5 per cent increase of corporate tax for Cyprus to reach parity with the Irish rate of 12.5 per cent; and a set of structural measures targeting both the public and the banking sectors ().

Table 4. Irish and Cypriot Programmes: a snapshot of the key provisions.

Time, strategy and policy outcomes

In the analysis that follows we frame time as an ‘enabler’ of policy learning, as a series of ‘windows of opportunity’ for policy change and a strategic resource in the hands of the negotiators on both sides. We focus, in particular, on four key dimensions:

Time as a negotiating (dis)advantage

This dimension is of direct relevance to the delaying tactics of the Cypriot government in requesting and agreeing a rescue package with its creditors. The country’s close financial connections with Greece (whose own banking system was also under severe pressure) and its effective cutting off from the international markets since mid-2011, had created a strong expectation that Cyprus had no other option but to turn to the Troika for support. The hesitation of President Christofias to do so became the subject of much criticism by the country’s financial establishment (Demetriades Citation2017, p. 90), but also frustrated Cyprus’s EU partners (Dijsselbloem Citation2018, Interviews 2 and 3).

These delays affected the negotiating position of the Cypriot government in three fundamental ways. Firstly, the intervening period between mid-2011 and March 2013, saw a rapid deterioration of the country’s economic outlook, as state finances worsened significantly (). Secondly, the Cypriot banking system was caught up in the massive write-down of privately held Greek debt (the so-called PSI) agreed as a condition of the second Greek bailout programme. The exercise, the largest of its type in history, was evidence that the EU had developed both the means and the confidence to see through the threat it had made at Deauville eighteen months earlier. The PSI affected bonds issued by Greece worth €206bn, with private investors incurring losses of up to 74 per cent of their initial investment (EC Citation2013). Cypriot banks in particular, faced losses equivalent to 25 per cent of the Cypriot GDP, adding further pressure on the Cypriot government to recapitalise them.

Thirdly, the lack of progress in the negotiations between the Cypriot government and its would-be creditors, dragged the Cypriot economic predicament into the 2013 German federal election campaign, where leading politicians reacted angrily to the prospect of EZ taxpayers’ money been used to protect deposits of Russian oligarchs on the island (Interview No. 2). The assessment of the Cypriot business model by Sigmar Gabriel, the SPD floor leader, as being one 'based on Russian oligarchs, Serbian mafias and tax evaders’ was reflective of this climate (Engelen Citation2013, p. 51).

German sensitivities on this issue inevitably restricted any room for manoeuvre by senior EZ officials and provided significant impetus to the idea of a ‘bail in’, involving losses by depositors (both local and foreign) in Cypriot banks (Van Rompuy Citation2014, p. 129, Dijsselbloem Citation2018, Demetriades Citation2017). Such an option was further facilitated by the fact that, in comparison to Ireland, major EZ banks had limited exposure to Cyprus and the fear of contagion from a potential policy experimentation in the Cypriot case (in the form of a ‘bail in’) was very limited.

Time as a platform for policy learning

The intervening period between the first Greek programme (May 2010) and the Cypriot one (March 2013) had been an intense learning curve for EZ and IMF policy makers, accompanied by rapid institutional building (e.g. the launch of the European Stability Mechanism, ESM) and major new policy initiatives on banking supervision (see below) and macroeconomic monitoring (e.g. the launch of the European semester). Pervious ‘taboos’ in the management of the EZ crisis were also revisited. The most emblematic development in this regard was the ‘Whatever it Takes’ speech of the ECB President, Mario Draghi, in July 2012, which, in sharp contrast with his predecessor, inaugurated the ECB’s activism in the secondary sovereign bond market, a move which despite its critics within the Eurosystem, was widely regarded as a turning point in the trajectory of the crisis (Interview 9, Henning Citation2017, p. 142, Van Rompuy Citation2014, pp. 22–3).

The severe difficulties facing the first Greek programme also forced the IMF to rethink its strategy. The issue of debt sustainability was critical in this regard. Repeated efforts to convince the markets that the first Greek programme was on track, hit a brick wall when it came to the sustainability of Greece’s debt. By 2013 the IMF had publicly acknowledged that the programme did not meet the underlying condition of all IMF interventions on the ‘high probability that the member’s debt [being] sustainable in the medium term’ (IMF Citation2013). Indeed, stiff opposition from both the ECB and key creditor countries (most notably, Germany) in 2010 had forced the IMF technocrats to accept a watered-down version of the ‘high probability’ principle if the programme was to mitigate ‘high risk of international systemic spillovers effects’ (IMF Citation2010, p. 20). This was a rhetorical ‘exit strategy’ for the creditors, pushing the contentious can of Greece’s debt restructuring further down the road.

This policy legacy put the IMF in a very awkward position when the Cypriot rescue package was discussed. Given the size of the Cypriot banking sector relative to the country’s GDP (), the assumption of all banking recapitalisation liabilities by the state would have rocketed the Cypriot sovereign debt, making uncomfortable comparisons with the situation in Greece. Against this background, the IMF proposed a strict limit to the aid that would be provided to the government of Cyprus (Interview No. 3) and offered two options for the additional funds required: either the ESM would recapitalise the banks directly and up front (in relative terms a small fraction of the ESM’s total capacity would suffice), or the cost of recapitalisation would be covered by a bail-in of depositors and other private creditors of the banks (Henning Citation2017, pp. 195–8). The first option was championed by the Cypriot government, but a number of EZ countries (e.g. Germany, Netherlands and Finland) resisted the idea, not least because of its apparent leniency on Russian money in the island (see above). This opposition aligned with the IMF’s own sensitivities on saddling the cost of recapitalisation on state finances, thus opening a window of opportunity for the ‘bail in’ option to gain traction.

Time as a justifier of past policy choices (path dependency)

By contrast, the decision not to opt for a ‘bail in’ solution in the case of Ireland, point to a different temporal dimension of the EZ crisis management: that of path dependency. The Irish programme of November 2010 was the second to be agreed, just six months after the Greek one, amidst growing evidence that the EZ crisis was spreading and acquiring characteristics of a systemic threat to the European economy. Although the intensity of the Greek programme had become evident for all to see, the pace of its implementation appeared satisfactory, with the Greek government been praised for its commitment and determination to see it through (Papaconstantinou Citation2016, pp. 147–59). At this early stage, concerns about the sustainability of Greek debt were relatively muted and the full extent of the programme’s recessionary impact (and hence the political minefield it created) had not yet been fully manifested. In this context and amidst the market turbulence caused by the Deauville Declaration (October 2010), EZ policy makers were very much preoccupied with setting the track of a policy path-dependency that, they hoped, would deliver reassurance and stability to the markets. Consistency with the key policy legacies of the Greek programme was, therefore, the order of the day as a means of building credibility.

Indeed, the possibility of involving the private sector in the recapitalisation of Irish banks was discussed as a policy option during the negotiations between the Irish government and its would-be creditors. Desperate to reduce the impact of recapitalisation on state finances, the Irish Minister of Finance, Brian Lenihan, floated the idea of incorporating a bail-in clause into the programme to the then IMF’s Managing Director, Dominque Strauss-Kahn, and the President of the ECB, Jean-Claude Trichet. The idea was also supported by the IMF technocrats but was rejected by Finance ministries across Europe and in the G5 group of countries that dominated the IMF Board (Breen Citation2012). The ECB’s own concerns about the impact of such a move on the systemic stability of the banking sector within the EZ was also a key driver behind this opposition (Donovan and Murphy Citation2013).

The underlying logic of a ‘bailout’ was easier to justify in the case of Greece where the economic implosion was blamed on government profligacy. In Ireland, the absence of a ‘haircut’ for senior bondholders of Irish banks became hugely controversial, prompting complains that the programme had essentially ‘nationalised’ huge losses fuelled by private greed (Breen Citation2012). This discrepancy sat uncomfortably with the highly moralistic discourse adopted in many creditor countries in the context of the Greek crisis where biblical references to the ‘moral hazard’ and the need to punish ‘bad behaviour’ became widespread (Art Citation2015, Crespy and Schmidt Citation2014). Yet, in policy terms, the preservation of the ‘bailout’ design legacy in the Irish programme was seen as instrumental by EZ policy makers in their effort to reassure the market that they had the crisis under control, but also to avert a systemic banking crisis in Europe as a result of heavy loses (Breen Citation2012, Donovan and Murphy Citation2013, p. 106).

Time as a signifier of future policy choices (path setting)

By the time the Cypriot government submitted its request for financial assistance in the summer of 2012, confidence in the ability of EZ policy makers to handle the crisis was on the increase. Hence, a policy window had opened, allowing for policy experimentation. The successful conclusion of the PSI in Greece had averted the danger of a disorderly Greek default (see above), the ECB’s newly found activism was making inroads in the secondary bond markets and negotiations on the establishment of the ESM progressed at pace. The wider climate had become more conducive for long term planning. In this context, EZ efforts shifted towards the construction of a European banking union, seen as an essential part of restoring stability in the financial sector (Ioannou et al. Citation2015). The plan aimed at achieving more targeted regulation, promoting good corporate governance and more effective risk management within financial institutions.

As part of this process, the Commission designed a framework for the recovery and resolution of credit institutions and investment firms. The proposal on a Bank Recovery and Resolution Directive (BRRD) was tabled in early June 2012. A key component of the plan was the explicit articulation of a ‘bail-in’ clause to ‘give resolution authorities the power to write down the claims of unsecured creditors of a failing institution and to convert debt claims to equity’ (EC Citation2012, p. 13). According to this provision, shareholders and creditors would assume the cost of bank failure, thus shifting the burden of recapitalisation away from the European tax-payer.

As part of its legislative initiative the Commission held a stakeholder consultation between 5 October and 28 December 2012, a period which overlapped with the negotiations of the Cypriot programme. By that time, Cyprus was widely regarded as an isolated case of no systemic threat to the EZ. The nature of its domestic banking crisis and the negligible (in relative terms) size of its economy made it an ideal testing ground for a ‘bail-in’. More importantly, the design of the Cypriot bailout carried a strong message to the future: the cost of rectifying market failures would no longer fall exclusively on the shoulders of government, but would have to be borne by private investors too. By the time the BRRD finally entered into force on 2 July 2014, nearly four years had passed from the Deauville Declaration. If the warnings of Chancellor Merkel and President Sarkozy against private sector losses in the context of bailout programmes rung hollow back then, the introduction of the BRRD and the Banking Union were meant to provide the legal backing to make the threat credible. Similarly, if the Greek PSI of 2012 was a desperate solution for an exceptional problem, the Cypriot bailout was meant to be the setting of a new ‘path’ in the way in which the EZ was to fight financial crises in its own backyard (Engelen Citation2013).

Conclusion

In this article we have sought to explain how the ‘bail in’ clause came to be an integral part of the EZ’s crisis management arsenal. The very conception of involving private investors in the cost of recapitalising banks dated back to the Deauville Declaration of October 2010, but its implementation in the context of the Irish programme was dismissed. We have argued that the introduction of the ‘bail in’ clause in the Cypriot programme was the result of a conjuncture of developments affecting all key players of the negotiation. The procrastination of the Cypriot government in seeking out support and negotiating the programme with its creditors, placed it in a uniquely vulnerable position, particularly in the aftermath of the Greek PSI which devastated its already ailing banking system. This vulnerability was further exacerbated by its position as a major destination of Russian deposits, which incentivised EZ policy makers to shift the cost of bank recapitalisation away from their own tax-payers.

By contrast, the EU’s own position on the outset of the negotiations with the Cypriot government was more secure relative to when negotiating with Ireland. The successful conclusion of the Greek PSI had broken a policy taboo with regards to private sector losses. In terms of its own policy development, the ECB had entered a new paradigm under Draghi, whereas the progress made with regards to the ESM and the Banking Union allowed greater scope for policy experimentation. The Cypriot request for aid was perhaps the only one that posed no systemic threat to the EZ. The IMF’s view on the adverse impact of non-sustainable national debt on the credibility of its programmes was, by then, non-negotiable. The prospect of saddling the huge cost of bank recapitalisation on Cypriot debt (under a bailout design) had lost favour among the key players on the creditors’ side, thus making the option of a ‘bail in’ an attractive alternative.

In sum, by the Summer of 2012 a window of opportunity had opened up for a new policy paradigm, which was not available at the time of the negotiation of the Irish programme. By reference to the temporality of the EZ’s crisis management, we have argued that this shift was premised on evidence of policy learning on behalf of the creditors, but also on their commitment to use the Cypriot programme as a means of setting a new ‘path’ for fighting future financial crises in which the private sector would carry a greater burden. Conversely, we have argued that in November 2010 -amidst widespread insecurity over the depth and reach of the crisis – EZ policy makers prioritised continuity (of design) between the Greek and the Irish programme as a means of establishing credibility with the markets, which, until then, had been proven elusive.

The theoretical innovation of our approach rests on our claim that policy learning and the dynamics of path dependency should not be seen as a priory incompatible explanations of policy development. At times of acute crisis management, policy makers are called to make fine judgments over the benefits of sustaining path dependent policies (carrying a premium on consistency) against the opportunities of setting new policy paths which promise increasing returns in the future. These are eminently strategic choices. The cases of Ireland and Cyprus demonstrated how the shift from ‘bailout’ to ‘bailin’ came to be. However, the instrumentalisation of time, both as accumulated learning and a strategic resource, remains relevant to the wider EZ crisis management, particularly in explaining differential modes of ‘rescue’ in larger countries in distress (e.g. Spain or Italy) or indeed the evolution of sequential bailout modalities in the case of Greece.

We recognise that our treatment of temporality in the context of the two programmes is partially incomplete, since it has focused primarily on the thinking of creditors on policy design. In that sense there is fertile ground for further research on the impact of the bailouts’ iterated nature on the thinking and strategising of debtor governments. Neither do we claim to have provided a fulsome comparison across all aspects of the Irish and Cypriot bailouts. The way in which fiscal consolidation and, crucially, tax reform (most importantly corporate taxation) was negotiated in the two programmes requires further scholarly attention. The same also holds true with regards to the legacy of the ‘bail in’ clause for the EZ’s next ‘existential’ crisis: the bust up with the Greek government over its third programme in the summer of 2015.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge the financial support received from the Post-doctoral Research Project DIDAKTOR/0609/30, co-funded by the European Regional Development Fund and the Republic of Cyprus through the Research Promotion Foundation.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Dimitris Papadimitriou

Prof. Dimitris Papadimitriou is Professor of Politics at the University of Manchester and Director of the Manchester Jean Monnet Centre of Excellence. He has previously held visiting posts at Princeton University, the London School of Economics and Yale University.

Adonis Pegasiou

Dr. Adonis Pegasiou is the Academic Director at the European Institute of Management and Finance in Cyprus. He has been the recipient of post-doctoral funding from the Research Promotion Organisation in Cyprus and has previously taught at the University of Cyprus and the European University Cyprus. He has held various professional posts in the public and private sectors.

Notes

1 The letter was made public by the ECB in 2014 only after the Irish Times managed to exclusively obtain and publish the content of this communication.

References

- Armingeon, K., and Cranmer, S., 2018. Position-taking in the Euro crisis. Journal of European Public Policy, 25 (4), 546–66.

- Art, D., 2015. The German rescue of the Eurozone: How Germany is getting the Europe it always wanted. Political Science Quarterly, 130 (2), 181–212.

- Axelrod, R., 1981. The emergence of co-operation among egoists. American Political Science Review, 75 (2), 306–18.

- Axelrod, R., 1990. The evolution of co-operation. London: Penguin Books.

- Breen, M., 2012. The international politics of Ireland's EU/IMF bailout. Irish Studies in International Affairs, 23, 75–87.

- Bulmer, S., and Burch, M., 2001. The Europeanization of central government: the UK and Germany in historical institutionalist perspective. In: G. Schneider, and M. Aspinwall, eds. The rules of integration: institutional approaches to the study of Europe. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 73–98.

- Capoccia, G., and Kelemen, R.D., 2007. The study of critical junctures: Theory, narrative, and counterfactuals in historical institutionalism. World Politics, 59 (3), 341–69.

- Chari, R., and Bernhagen, P., 2011. Financial and economic crisis: explaining the sunset over the Celtic Tiger. Irish Political Studies, 26 (4), 473–88.

- Crespy, A., and Schmidt, V.A., 2014. The clash of Titans: France, Germany and the discursive double game of EMU reform. Journal of European Public Policy, 21 (8), 1085–101.

- Dellepiane-Avellaneda, S., Hardiman, N., and Heras, J.L., 2022. Financial resource curse in the Eurozone periphery. Review of International Political Economy, 29 (4), 1287–1313.

- Demetriades, P., 2017. Diary of the Euro crisis in Cyprus. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Dijsselbloem, J., 2018. The Euro crisis: the inside story. Amsterdam: Prometheus.

- Djankov, S., 2014. Inside the euro crisis: an eyewitness account. Washington: Peterson Institute for International Economics.

- Dolowitz, D.P., and Marsh, D., 2000. Learning from abroad: the role of policy transfer in contemporary policy-making. Governance, 13 (1), 5–23.

- Donnelly, S., 2014. Power politics and the undersupply of financial stability in Europe. Review of International Political Economy, 21 (4), 980–1005.

- Donovan, D., and Murphy, A., 2013. The fall of the Celtic Tiger: Ireland and the Euro debt crisis. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Drezner, D., 2014. The system worked: How the world stopped another great depression. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Dunlop, C.A., and Radaelli, C., 2013. Systematising policy learning: From monolith to dimensions. Political Studies, 61 (3), 599–619.

- Dyson, K., 2010. Norman's lament: The Greek and euro area crisis in historical perspective. New Political Economy, 15 (4), 597–608.

- EC. 2011. The economic adjustment programme for Ireland. European Economy Occasional Papers, p. 76.

- EC. 2012. Proposal for a Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council establishing a framework for the recovery and resolution of credit institutions and investment firms. COM, 280.

- EC. 2013. The economic adjustment programme for Cyprus. Occasional Papers, p. 149.

- EC. 2015. Ex post evaluation of the economic adjustment programme, Ireland 2010–2013. European Economy Institutional Paper, p. 004.

- EC. 2019. Ex-Post evaluation of the economic adjustment programme Cyprus, 2013–2016. European Economy Institutional Paper, p. 114.

- ECB. 2010. EU banking structures, September. Frankfurt: European Central Bank.

- Engelen, K.C., 2013. From deauville to Cyprus. The International Economy, 27 (2), 50–76.

- Featherstone, K., 2011. The JCMS annual lecture: the Greek sovereign debt crisis and EMU: a failing state in a skewed regime. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 49 (2), 193–217.

- Government of Ireland. 2008. Statutory Instrument No. 411/2008 – Credit Institutions (Financial Support) Scheme 2008.

- Hall, P., 2014. Varieties of capitalism and the Euro crisis. West European Politics, 37 (6), 1223–43.

- Hall, P., and Soskice, D., eds. 2001. Varieties of capitalism: the institutional foundations of comparative advantage. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hardiman, N., et al., 2019. Tangling with the Troika: ‘domestic ownership’ as political and administrative engagement in Greece, Ireland, and Portugal. Public Management Review, 21 (9), 1265–86.

- Hay, C., 2020. Does capitalism (still) come in varieties? Review of International Political Economy, 27 (2), 302–19.

- Henning, C., 2017. Tangled governance: international regime complexity, the Troika, and the Euro crisis. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- ICFCBS. 2013. Final report and recommendations, Nicosia.

- IMF. 2010. Greece: staff report on request for stand-By arrangement. IMF Country Report No. 10/110.

- IMF. 2013. Sovereign debt restructuring - Recent developments and implications for the fund's legal and policy framework. 26 April 2013.

- Ioannou, D., Leblond, P., and Niemann, A., 2015. European integration and the crisis: practice and theory. Journal of European Public Policy, 22 (2), 155–76.

- Kingdon, J., 1984. Agendas, alternatives, and public policies. Boston: Little, Brown and Co.

- Morlino, L., and Sottilotta, C.E.2019. The politics of the Eurozone crisis in Southern Europe: A comparative reappraisal. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Moury, C., et al., 2021. Capitalising on constraint: Bailout politics in Eurozone countries. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Papaconstantinou, G., 2016. Game over: The inside story of the Greek crisis. New York: CreateSpace Independent Publishing.

- Pegasiou, A., 2013. The Cypriot economic collapse: More than a conventional South European failure. Mediterranean Politics, 18 (3), 333–51.

- Pelagidis, T., and Mitsopoulos, M., 2014. Greece: From exit to recovery? Washington: Brookings Institution Press.

- Pierson, P., 2000. Not just what, but when: Timing and sequence in political processes. Studies in American Political Development, 14 (1), 72–92.

- Pierson, P., 2004. Politics in time: history, institutions and social analysis. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Pisani-Ferry, J., 2011. The Euro crisis and its aftermath. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Pralle, S.B., 2006. Timing and sequence in agenda-setting and policy change: a comparative study of lawn care pesticide politics in Canada and the US. Journal of European Public Policy, 13 (7), 987–1005.

- Riddervold, M., Trondal, J., and Newsome, A.2020. Handbook on EU crisis. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Rose, R., 1991. What is lesson-drawing? Journal of Public Policy, 11 (1), 3–30.

- Schmidt, V.A., 2013. Arguing about the Eurozone crisis: a discursive institutionalist analysis. Critical Policy Studies, 7 (4), 455–62.

- Sepos, A., 2008. The Europeanization of Cyprus: polity, policies and politics. Basingstroke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Steinmo, S., Thelen, K., and Longstreth, F., eds. 1992. Structuring politics: Historical institutionalism in comparative analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Thelen, K., 1999. Historical institutionalism in comparative politics. Annual Review of Political Science, 2 (1), 369–404.

- Vaara, E., 2014. Struggles over legitimacy in the Eurozone crisis: Discursive legitimation strategies and their ideological underpinnings. Discourse & Society, 25 (4), 500–18.

- Van Rompuy, H., 2014. Europe in the storm: promise and prejudice. Louvain: Davidsfonds.

- Whelan, K., 2014. Ireland’s economic crisis: the good, the bad and the ugly. Journal of Macroeconomics, 39, 424–40.

- Zenios, S., 2016. Fairness and reflexivity in the Cyprus bail-in. Empirica, 43 (3), 579-606.