ABSTRACT

This article analyses an overlooked financial instrument in political economy, despite its institutionalisation having immense ramifications for European financial markets: the covered bond. Following decades of cross-continental bank lobbying led by German mortgage banks, covered bonds transformed from a ‘little-understood corner of the German bond market’ in the mid-1990s into a global multi-trillion dollar market in the years prior to the Global Financial Crisis. This article highlights that covered bonds, on the one hand, stabilise and de-risk financialised capitalism by providing credit institutions with a stable means of bank financing and collateral while providing investors with safe investment opportunities, including during periods of crisis. In addition, the expansion of covered bond markets has marginalised mortgage securitisation in much of Europe. On the other hand, covered bonds fuel household indebtedness by increasing the credit supply available for mortgage lending, which is the primary activity of contemporary banking in general and covered bond issuers in particular. The instrument can therefore be perceived as a more simple, stable and efficient instrument for household financialisation compared to the more crisis-prone residential mortgage-backed derivative.

Introduction

Following the crisis of the Fordist mode of regulation, contemporary European capitalism has increasingly financialised. Albeit with different intensity, the political fertilisation of financial markets through deregulation, harmonisation, lowered capital taxation, marketisation of corporate control and the rise of international institutional capital as well as shareholder value ideology has taken place across Europe since the 1970s (Van Apeldoorn and Horn Citation2007, Nölke et al. Citation2013, Durand and Keucheyan Citation2015). While the EU has tried to emulate North American financial systems and institutions (Bieling Citation2003), one major difference stands out between the two continents’ financial markets – why did Europe securitise to a far lesser extent than North America (Stockhammer et al. Citation2016, p. 1812; Metz Citation2018)? And what explains the extensive rise in mortgage lending in much of Europe, despite the absence of securitisation?

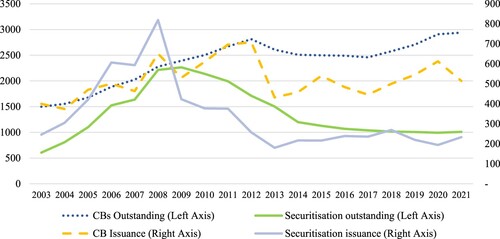

This article elaborates on these questions by critically analysing the spread of covered bonds (henceforth referred to as CBs). In a decade prior to the Global Financial Crisis (GFC), CBs went from a ‘little-understood corner of the German bond market’ (McLannahan Citation2007) to a multi-trillion dollar market and became the second largest debt market instrument after government bonds (Lassen Citation2005). By the mid-2000s, CBs had evolved into a ‘global asset class’, an ‘unparallel bull-market’ that was ‘too big to ignore’ for investors and credit institutions alike (McLannahan Citation2007). Financial institutions with mediocre credit ratings could issue triple-A rated CBs that became a popular investment category among central banks, supranational agencies, pension funds and insurers, as well as among banks themselves, as CBs were perceived almost as safe as government bonds but with a higher yield. Between 15 and 25 per cent of all mortgage loans in the EU have been refinanced by CBs since 2003 (ECBC Citation2020), a larger number than that of Residential Mortgage-Backed Securities (RMBSs) (Wainwright Citation2015, pp. 1648–1649). A transparent and regulated alternative to securitisation, CBs are subject to special supervision by public authorities. From an investor point-a-view, the instrument is associated with safety as a pool of assets are ringfenced by the issuer that are guaranteed for bondholders in case of insolvency (Avesani et al. Citation2007), making it a cheaper funding alternative than unsecured conventional bonds. While harmonised CB legislation refers to CBs that are compliant with UCITS (Undertakings for the Collective Investment in Transferable Securities, the common European regulatory framework for investment funds), securitisation refers to RMBSs that are used for mortgage-financing and likewise is the most common type of securitisation in Europe (ibid) ().

Table 1. Some characteristics of CBs and RMBSs.

Opposing the neoclassical assumption that markets are ahistorical, technical institutions detached from the political sphere, the article highlights that CB institutionalisation has been a lengthy political, ideological and transnational process, as CBs have been pushed for and mediated by mortgage banks and EU technocrats for decades. The article argues that CBs have contradictory and paradoxical effects on financialisation. On the one hand, CBs stabilise and de-risk financial markets by providing financial systems with relatively safe assets (cf. Gabor and Vestergaard Citation2018); provide lenders with a stable funding source during financial distress; and partly ‘crowd out’ securitisation, a more unstable and arguably less effective instrument for household lendingthan CBs (H1). On the other hand, by providing highly leveraged financial institutions the ability to issue triple-A rated credit instruments, CBs improve banks’ refinancing opportunities and thereby increase the credit supply available for mortgage lending (Riksbank Citation2014; C3; H1). In the words of the European Commission (Citation2018), ‘ … covered bonds allow banks to lend not only more, but also more safely’. Being ‘typically designed for mortgage lending’ (ECBC Citation2020), CBs accelerate household indebtedness which have significant economic and social implications. Nevertheless, CBs are a relatively ignored topic in financialisation studies (cf. Aalbers Citation2019), which is surprising considering the instrument’s large trading volumes along with its complex implications for financialisation.

In order to scrutinise CBs’ multifaceted impact on European financial markets, the following research questions are examined: Why and how did CBs spread the last decades? How have CBs coevolved with RMBSs? How do CBs contribute to financialisation?

The next chapter provides an overview on housing finance, the technical and regulatory aspects of CBs, and the instrument’s complex impacts on European financial markets. The ensuing chapter brings up methodological considerations, which is followed by a chapter that discusses the political economy of EU financial market regulation. The subsequent chapter provides an empirical overview of CB market evolution in Europe by backgrounding events taking place in the late post-war period and foregrounding financial integration in Europe during the 1990s and onwards. The article closes with a concluding discussion.

Housing finance in European neoliberal capitalism

Financialisation, an increasingly important feature of contemporary capitalism since the termination of Bretton Woods, the crisis of Fordism and the liberalisation of financial markets (Epstein Citation2005, Bieling Citation2013, Nölke et al. Citation2013), is broadly indicated by ‘the rising volume of financial assets and claims vis-à-vis non-financial actors such as companies, private households or state agencies’ (Bieling and Guntrum Citation2020). This article focuses on household financialisation as an informal macroeconomic stimulus by which financial markets grow parallel with rising household debt (Crouch Citation2009, Karwowski et al. Citation2020, p. 969). The article argues that securitisation has been overemphasised as a universal driver of financialisation, arguably due to its central role during the GFC as well as in the globally important US financial system more generally. While scholars of European financialisation have shown interest in securitisation (e.g. Wainwright Citation2015, Aalbers Citation2019), it is not a key feature of financialisation in most European economies (Stockhammer et al. Citation2016, p. 1812), largely due to CBs (Diaz-Granados Citation1996, pp. 20–21, ECB Citation2011, p. 16, ABN AMRO Citation2012, p. 4, DNB Citation2021; C1; FI; H1).

Due to financial regulation, capital controls, and foreign investors’ limited knowledge about variegated national mortgage markets, housing finance was largely a domestic issue in post-war economies. Following financial liberalisation and integration, the vast accumulated capital held by international institutional investors has supplied immense quantities of capital to banks the last three decades (Lysandrou and Nesvetailova Citation2015). The increase in household wealth can to a large part be explained by house price inflation that in turn corresponds to accumulated mortgage debt in basically all advanced economies, albeit with different intensity (Blackwell and Kohl Citation2018, Kohl Citation2020). Policy in the domains of financial regulation, lending regulations such as loan-to-value ratios, housing construction subsidies, interest deductions and property taxes have wide implications for house prices and household indebtedness (Dam et al. Citation2011, Fuller Citation2015, Johnston et al. Citation2021). However, many argue that the enlarged credit supply of the last three decades has been crucial for these developments. Justiniano et al. (Citation2019) at the Federal Reserve claim that an increase in the credit supply in the US following securitisation in the late 1990s was the main driver of rising household debt, falling mortgage interest rates and increasing house prices. In similar fashion, Mian and Sufi (Citation2018, p. 40) argue that ‘credit supply expansion induced by an institutional change’ resulted in a boom in household debt and subsequent economic downturn following the GFC slump in several European economies. ‘The weight of the empirical evidence suggests that house prices are more likely to be a response to credit supply expansion rather than a cause’ (ibid). Following increased credit provision, house prices have risen faster in countries with more inelastic housing supplies (Favara and Imbs Citation2015).

Financial innovations have further improved the channelling of capital to banks. These easily spread over borders as economic and political actors alike look for innovations to cope with uncertainty originating from competitive global markets. Disseminated through a combination of learning, competition and coercion (Dobbin et al. Citation2007), financial innovations often travel through inter-scalar linkages and transnational industry expert groups that promote learning among technocrats and private sector agents (Wainwright Citation2015, Nunn Citation2020). Local implementors usually translate, incrementally modify and sometimes transform external innovations in order to overcome legitimacy problems, match new policies with local institutions and satisfy the preferences of incumbents. Financial innovations, including harmonised CBs, thus typically mutate rather than disseminate homogeneously when they spread to new environments (McCann and Ward Citation2013).

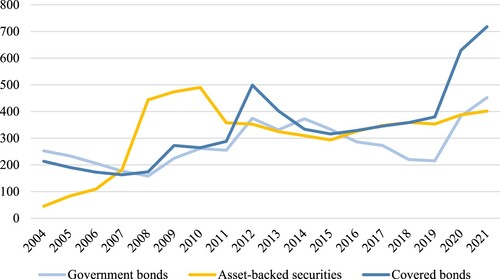

While banks create credit money endogenously (Lavoie Citation2009, pp. 54–55), they need to finance and retain ‘regulatory capital’ (i.e. ‘capital requirement’ or ‘capital adequacy’) on the asset-side of their balance sheets as required by regulators (European Commission Citation2015a, p. 21). In the words of a former bank CEO, all banks ‘that expanded had problems with the capital adequacy’ (C2). At the most general level, all bank financing means (such as deposits, conventional uncovered bonds, securitisation, and CBs) enable extended lending. CBs allow for cheaper and larger quantities of mortgage loans (Riksbank Citation2014, European Commission Citation2018; C3; H1) and thereby comprise a potential motor of financialisation, especially if it coevolves with other financialisation-driving mechanisms, such as low interest rates and housing shortages. As some financial means are more unstable and crisis-prone than others, CBs contribute to stabilising financialised economies, firstly by providing financial systems in general and banks in particular with relatively safe assets, or ‘fantastic quality collateral’ (Metz Citation2018:115; see ), and secondly by providing issuers with a reliable funding instrument in normal times as well as during times of crisis. As according to one banker:

You can basically issue it constantly … it’s a triple-A instrument, the market is very big in terms of the investors, so it’s really the instrument that you know in the worst times of financial stress that you can count on […] it is very easy to activate and the time to market is very short so it definitely improves the funding and liquidity profile of banks and reduce systemic risks. (H1)

Figure 1. Use of collateral in the Eurosystem. Source: ECB (Citation2022a).

In a contradictory fashion, CBs both ameliorate crisis tendencies due to the aforementioned reasons, while making economies more crisis prone by contributing to debt accumulation among households and credit institutions.

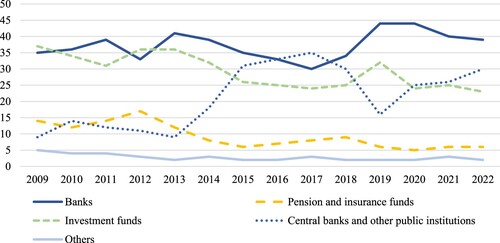

On a technical level, CBs usually satisfy four components defined in the UCITS Article 52(4): issued by an EU credit institution; subject to special supervision by the issuer’s domestic public authority; ring-fenced cover assets are provided for investors in case of bankruptcy; and dual recourse, implying that investors have preferential rights over the cover assets and the issuer’s other assets in case of bankruptcy (Avesani et al. Citation2007, EBA, Citation2016). EU officials have been ‘extremely friendly towards covered bonds’ (EBA Citation2016, p. 85), which is mirrored in CBs’ advantageous stature in solvency and liquidity regulations (ECBC Citation2020, pp. 136–137). CBs moreover received a low risk-weighting of 10 per cent in the late 1990s, compared to 20 per cent for conventional uncovered bank bonds, making CBs highly attractive investment opportunities for banks who subsequently have been the instrument’s largest investor category the last two decades (EBA Citation2016; ). Due to favourable capital adequacy frameworks, the more a bank invests in another bank’s CBs (retaining CBs on the balance sheet’s asset side), the less equity it has to retain in comparison to most other assets, which in turn enables further lending (Riksbank Citation2014, pp. 29, 33–34).

Figure 2. European CB investor categories (%). Source: ECBC, European Commission (Citation2015a), BIS, EBA (Citation2016).

Methodology

To support the article’s propositions on CBs and its complex relationships and causal links with securitisation and household financialisation, a case-centred approach (Eisenhardt and Graebner Citation2007, Alvesson and Kärreman Citation2011) was applied in order to tease out why and how CB markets have expanded since the late post-war period. The empirical analysis also dissects and evaluates the varying importance of four types of actors (domestic regulators, domestic banking groups, supranational regulators and transnational lobby organisations) during three CB institutionalisation episodes: the early days (1967–1994), accelerated institutionalisation (1995–2007), and the post-crisis period (2008 to the present). As for boundary delimitations, the analysed sources almost exclusively focus on Western Europe. As a common feature in case study methodology, a variety of methods and data (Eisenhardt and Graebner Citation2007) have been used in this article. A document analysis was undertaken where investigative documents about CBs by central banks, governments, supranational institutions, domestic banking associations, the quarterly journal Housing Finance International as well as commercial bank annual reports were examined. A systematic reading of the European Covered Bond Council’s (ECBC’s) Covered Bond Fact Book issues (2004 to 2022), an extensive annual publication that provide data and market analysis on CB markets worldwide, was also conducted. Most crucially for detecting common themes as well as dissimilarities among the institutionalisation processes in different financial spaces was the surveying of international business press articles obtained through ProQuest's ABI/INFORM business news database from the late 1990s to the late 2000s. Macroeconomic data was collected from supranational organisations such as the ECB and the European Commission and financial industry associations including the European Mortgage Federation (EMF), ECBC, the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association (SIFMA) and the Association for Financial Markets in Europe (AFME).

In addition, semi-structured interviews with ten CB experts of eight nationalities took place between 2020 to 2022 to gather further information about different countries’ legislative processes, explore perceptions held by private and public sector insiders, and triangulate interpretations from the document analysis. The CB community is open rather than secretive and interviewees were identified through tips from within the sector, through searches on financial institutions’ websites, or via the ECBC Covered Bond Fact Book. Interviewees consisted of senior bank executives, a former bank CEO, and lobbyists within the financial sector, some of which having academic background specialising in history and CB law ().

Table 2. List of interviews.

The political economy of European financial market regulation

Quaglia (Citation2012) discerns three major divisions within the literature on European financial market integration: the impact of the UK, Germany and France in shaping common EU financial regulation, as domestic regulators generally aim to craft policy beneficial to their financial sectors (Jabko Citation2006, p. 21, Mügge Citation2006); the European Commission’s role in accelerating financial integration (Posner Citation2005, Jabko Citation2006); and the instrumental and/or structural power of industry and financial sectors, including the private sector’s lobbying for financial liberalisation and integration (Bieling Citation2003, Citation2013, Van Apeldoorn and Horn Citation2007, Durand and Keucheyan Citation2015). As capitalism increasingly globalised and financialised, political power has been rescaled from domestic to supranational institutions that, in coalition with domestic and transnational elites of capital, have proceeded to ‘embed modes of regulation within other states, favourable to the interests and worldviews of dominant capitalist class fractions’ (Hameiri Citation2020). Cross-border coalition building between (financial) industry elites and sympathetic policymakers has been instrumental in these efforts (Wainwright Citation2015), as domestic embedding of transnational regulation has either been initiated by local actors aiming to benefit from such regulation or outward-looking actors striving to introduce legislation in other domiciles for their own purposes. Such mutual interests may lead to transnational coalitions (Bieling Citation2013, Durand and Keucheyan Citation2015, Raza Citation2016, Hameiri and Jones Citation2016, Chacko and Jayasuriya Citation2018, Hameiri Citation2020) that have been crucial for the spread of CBs in Europe as will be seen later in this article.

While any capitalist system requires regulation to moderate its inherent instability (Sokol Citation2022, Dafermos et al. Citation2023), growth in Europe’s mode of neoliberal capitalism has proven particularly sluggish. EU managers have thus had to reconcile conflictive objectives of economic growth, financial stability and competitiveness of European banks ( Buch-Hansen and Wigger Citation2011, Howarth and Quaglia Citation2016), including mitigating credit volatility without strangling private lending (Pape Citation2020, p. 68). While the strategic removal of risk from certain sectors has been an important political issue since the post-war period, de-risking has been an explicit objective to reallocate risk and reward between the public sector and the private sector after the GFC (Gabor Citation2021). Although CBs do not directly transfer risk from private actors to sovereigns, the instrument can nevertheless be regarded as a private sector financial innovation that is continually institutionalised by EU civil servants as to de-risk Europe’s financialised capitalism.

The evolution of harmonised covered bonds in Europe

The following section traces Pan-European discussions on CB harmonisation among mortgage banks from the late 1960s and onwards. It then surveys the spread of harmonised CB legislation on the European continent during the decade prior to the GFC. The uneven structural characteristics of country-specific financial systems, CBs’ antagonistic relationship with securitisation, and the agency of banking groups and regulators are discussed as key factors impacting the instrument’s variegated spatiotemporal institutionalisation.

The formation of the European mortgage federation

The European Commission has stimulated ‘more than 50 years of discussion on the EU-wide harmonisation of secured bonds’ (Stöcker Citation2019) by calling upon national banking associations to hold pan-European discussions on CB harmonisation, striving for financial integration in general (Jabko Citation2006), and treating CBs favourably in regulatory statutes in particular (EBA Citation2016, p. 85). On Belgian and Dutch initiatives, the European Mortgage Federation (EMF) was established in 1967 and functioned as a Europe-wide forum for mortgage bank representatives and policymakers to foster a discussion on mortgage law, national CB varieties and eventually the harmonisation of CB law (VPD Citation2020). An essential part of the background was the EEC produced report The development of a European capital market, also known as the Segré report (Segré Citation1966, Engelhard and Sattler Citation2020), which outlined the vision of an integrated Pan-European market-based financial system comparable to that of the US (Bieling Citation2003, Haerter Citation2020). Discussions on CB harmonisation were led by German bankers who have been ‘involved in almost all work on regulatory amendments across the European region regarding CBs’ and ‘cooperated with ministries, other authorities, and parliaments, as well as with banks and their associations in many countries’ (Stöcker Citation2019). German mortgage banks, who enjoyed exclusive rights to issue CBs contrary to other German credit institutions, realised that eventual cross-border investments in CBs necessitated European CB harmonisation that would enable familiarity with the instrument among international investors and European regulators. The ability of issuing CBs on a global scale could have been a matter of their survival as competition in the German financial sector accelerated in the late 1960s (Fastenrath Citation2019, pp. 184–190). The German CB version (the ‘Pfandbrief’) therefore became a benchmark for other mortgage systems during policy discussions that took place amid the relaunch of the European state project (Jabko Citation2006, Durand and Keucheyan Citation2015). Major achievements were made at a conference in Munich in 1981, which resulted in a proposal for Europewide harmonisation of CB law, while core elements of a CB directive were brought forward at a conference in Chiemsee, Germany in 1984 (Stöcker Citation2019).

Following the fall of the Berlin wall, intensive German lobbying took place throughout the continent, including in Central and Eastern Europe (Euromoney Citation1994, Citation1995). A former bank CEO that participated in EMF meetings in the early 1990s recalls ‘lively discussions … [in which] the Germans aggressively marketed their [covered bond] system […] The government’s motive [for legislation] was that CBs was a better means for bank financing […] That, and the pressure from the EU and Germany was crucial’ (C2). Another participant in a neighbouring country claimed that ‘Obviously the Germans tried to push their product … they were very eager to have covered bond markets to develop in other countries as well. And when we started our market in [country] of course we consulted the German pfandbrief association in relation to that’ (E1). Many Central and Eastern European economies became early implementors of harmonised CB legislation, essentially ‘carbon copies of the German laws’ (Brown Citation2004) rather than implementing securitisation-friendly legislation in the 1990s (Stöcker Citation2001, Citation2019). However, despite early CB legislation, the region’s relatively undeveloped financial markets contributed to low or essentially zero issuance.

Taking cover – the rapid spread in 1995 to 2007

Against this background, German banks issued the first ‘Jumbo Pfandbreife’ CBs (Dm1 billion/$720 million) designed to attract foreign capital in 1995. Jumbo issuances soon became ‘one of the most intriguing developments in international capital markets’ (Walker Citation1999) prompting many legislatures to investigate harmonised legislation. A further impetus for the instrument’s Europewide attention was its beneficial regulatory treatment. According to Avesani et al. (Citation2007), ‘the rapid growth of European covered bonds has to a large extent been fostered by a favourable European law’, specifically the amended Article 22(4) (later revised as Article 52(4)) in UCITS, which was implemented in 1988 and significantly favoured CB legislation. The amendment, lobbied by Danish mortgage banks, let investment funds invest up to 25 per cent of its assets in CBs of a single issuer. In the late 1990s, the Bundesbank defined CBs as highly safe Tier 1 capital within the Lombard eligibility framework which made CBs eligible as collateral when borrowing from the ECB in its early existence (Arndt Citation1999). CBs also became a key staple in ECB’s monetary policies and the second most important instrument for collateral after government bonds during the first years of ECB’s existence (). Meanwhile, European technocrats started an aggressive push for European financial integration, including the Financial Services Action Plan (FSAP) launched in 1999 (Bieling Citation2003, pp. 211–212), the introduction of the single currency, and the Lamfalussy process that pooled financial regulation in Brussels, although much regulation was retained at the domestic level (Mügge Citation2013, p. 640). With the emergence of Jumbo Pfandbreife and regulatory privileges, banks’ preference for CBs incrementally grew relative to securitisation throughout Europe, with some time-lags, since the mid-1990s (The Banker Citation2005). As one former bank CEO explains:

[Our bank] was not fond of CBs initially and thought that securitisation was more in vogue and provided more latitude. But eventually we ran into problems with securitisation. The technique required lot of work, and we were hit hard by the Tiger economic crisis 97-98, which meant that we had to put down all [securitisation] plans. In this way, covered bonds were better. It is not so prone to financial market fluctuations. (C2)

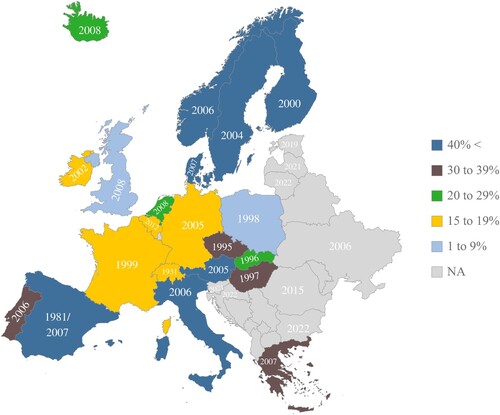

First out to institute harmonised CB law in Western Europe were the French authorities, where ‘The success of the German Pfandbriefe market has inspired new legislation in France on mortgage-backed bonds’ as ‘The absence of a significant mortgage-backed securities market [has been seen as] a significant brake on the development of the French financial markets … ’ (Smallhoover and Cano Citation1999). Spain had introduced domestic CB legislation already in 1981 following a banking crisis, and demand for harmonised Spanish CBs increased by the turn of the Millennium as a response to the Jumbo Pfandbrief. The country was a hotbed for credit growth in the early 2000s due to high GDP and wage growth, mortgage subsidies, and low central bank interest rates, and Spain became the continent’s second largest CB issuer by the mid-2000s. Utilising securitisation methods, some UK and Dutch banks began to issue ‘synthetic’ CBs in the mid-2000s, that nevertheless received worse risk weighting in the absence of domestic CB regulation. UK authorities gave the green light to CB law in 2006, and legislation was in place in 2008 in both the UK and the Netherlands to provide banks with a level playing field with other issuers throughout Europe (Gaffney Citation2007). The instrument’s superb credit rating enlarged new issuers’ investor bases, both geographically and by investor type. Banks interested in issuing CBs thus sought new investors and to reduce borrowing costs; investors were in turn attracted to new CB domiciles for diversification purposes. Economies therefore tended to show strong capital inflows when the required legislation was in place (Euroweek Citation2006) ().

Figure 3. CBs as % of residential mortgage loans in 2021. Years imply introduction of harmonised CB law or of important regulatory amendments. Deposit financing remains the dominant bank financing means in Germany, France and Eastern Europe, which explains the limited issuance in these countries. Regulatory issues also play a role – until recently, Belgian authorities did not allow banks to issue new CBs if cover pool assets exceed 8% of a bank’s total assets. Source: EMF, ECBC.

Media archives highlight lobbying activities in favour of CB law in most parts of Europe. Eventually also Dutch and UK banks started to push for legislation (Farnham Citation2005, Chambers and Wookey Citation2007). Proponents often built the instrument’s legitimacy by pointing to its presence in other jurisdictions and arguing that competitiveness would deteriorate in the absence of CB legislation (MoF Citation1997, Dagens Industri Citation2001, Euroweek Citation2006, SFI Citation2006). According to a Scandinavian bank official, ‘the Bankers’ Association and the [financial] sector have worked for this for a long time. It is a competitive disadvantage that we cannot offer this type of bond’ (Dagens Industri Citation2001). Another banker said that ‘A lot has happened since 1997. At that time, in principle, only Germany and Denmark offered covered bonds. The system is now available throughout Europe and is becoming the standard for borrowing’ (Dagens Industri Citation2001).

The relative strength and preferences of banking groups and civil servants also explain the timing of initiated CB institutionalisation processes and why CBs were more difficult to implement in some domiciles. Sweden provides one example, where the Swedish Bankers’ Association started to lobby for CBs since the early 1990s (MoF Citation1997, p. 189). While a social democratic government started to investigate CBs in 1996, Riksbank regulators, instead preferring banks to develop a sophisticated securitisation industry, as well as the non-financial industry lobby that was sceptical about CBs, managed to temporarily halt the CB legislation process in 1998 (Riksbank Citation1998). However, when CBs spread throughout Europe, heavy bank lobbying (Euroweek Citation2006) and the Ministry of Finance managed to convince veto players that CBs were a necessity on competitive grounds, and legislation was eventually in place in 2004. Italian regulators were likewise reluctant to implement legislation, despite lengthy lobbying efforts by Italian credit institutions (SFI Citation2006).

Akin to the notion of financial markets’ ‘infrastructural power’ (Braun Citation2020), the European Commission (Jabko Citation2006) and ECB (Citation1998) technocrats perceived mortgage markets and CBs as crucial components for financial integration, monetary policy effectiveness and financial stability (ECB Citation2005). In addition, CBs would also improve the Eurosystem’s collateral policy as government bond issuance was shrinking amid fiscal consolidation (ECB Citation1999, Citation2022a; ). EMF’s creation of ECBC in 2004 as the new primary CB lobby organisation was therefore hailed by the ECB as an important initiative to foster European capital market integration. In the words of an ECB board member, ‘ … we are willing to engage in an open dialogue with the [ECBC and the CB] industry on the most efficient and effective ways to overcome existing hurdles to further integration of the European mortgage markets’ (ECB Citation2004).

Further issuance and harmonisation during and after the GFC

It was early perceived that CBs benefited from an implicit state guarantee (Riksbank Citation1998, Boesel et al. Citation2018), which contributed to the instrument’s rapid expansion in the 2000s. In 2004, Barclays Capital argued that mortgage banks had obtained too-big-to-fail status as ‘no European government can afford to let a licensed mortgage bank go under due to the reputational risk to both the banking system and the economy’ (Euroweek Citation2005). One banker claimed that much investor appetite for CBs was based ‘purely on the basis of triple-A ratings … that will become increasingly dangerous as spreads grind closer to government bonds’ (ibid). Well into the financial turmoil during the GFC, CBs captured the financial world’s attention as the instrument performed comparatively well in terms of issuance (), market liquidity and change in interest spreads, prompting US Treasury secretary Hank Paulson and billionaire investor George Soros to call for the instrument’s implementation in the US. A contributing factor to the instrument’s performance was the ECB’s €60 billion CB purchase programme (CBPP1), executed on both primary and secondary markets in May 2009 to June 2010. CBs have since become the main pillar of the Eurosystem’s quantitative easing measures (CBPP2 and CBPP3), as the ECB owned more than a third of the outstanding benchmark market in 2016 (EBA Citation2016). Being highly appreciated by regulators after the crisis, CBs also received favourable treatment under the Solvency II Directive, the EU liquidity coverage ratio (LCR) framework, and BASEL III rules, while being exempted from bail-in under EU’s Bank Recovery and Resolution Directive (EBA Citation2016, ECBC Citation2020), all of which favour usage of CBs. When regulators imposed stricter capital ratios during and after the GFC, essentially forcing banks to deleverage, CBs remained an attractive investment opportunity for banks due to its superb risk weightings.

Figure 4. CB and securitisation issuance and outstanding in Europe, billions of Euros. Source: ECB, AFME and SIFMA.

Evidently, the GFC further increased the attractiveness of CBs vis-à-vis securitisation. According to the ECB (Citation2011, p. 16), ‘As regards demand for securitised products, covered bonds are potentially an important competitor, especially for RMBSs’ while the Dutch central bank claims that the ‘long-term downward trend [of Dutch securitisation] is linked, among other things, to … the issuance of covered bonds’ (DNB Citation2021; see also ABN AMRO Citation2012, p. 4). The crisis moreover accelerated CB institutionalisation in Canada, Australia and New Zealand, while a dozen Asian, Latin American and African countries have either instituted or are exploring legislation, as non-European markets accounted for 22 per cent of outstanding CBs in 2021. Housing over 120 member organisations across 30 jurisdictions that account for most of global CB issuance, while providing investors and regulators with data, legal counselling, market intelligence and information on national CB models, the ECBC has by no means been unimportant in the instrument's spread outside of Europe (ECBC Citation2020, pp. 27; 25–26; C1).

As any significant degree of financial sector reform was staved off in the aftermath of the GFC (Quaglia Citation2012, Mügge Citation2013), politically supported proliferation of financial markets and accelerated financial integration eventually became a neoliberal crisis solution to Europe’s uneven development and chronic demand-side deficits (Hübner Citation2016). This culminated in the European Commission’s (Citation2015b) presentation of its green paper on building a Capital Markets Union (Braun et al. Citation2018) that briefly hails CB markets as a ‘success’ and that ‘a more integrated European covered bond market could contribute to cost-effective funding of banks and provide investors with a wider range of investment opportunities’, while the European Parliament and the Council of the European Union approved an EU-wide covered bond harmonisation package in 2019. The Covered Bond Directive, that is currently being implemented throughout Europe, is expected to make national CB variations more homogenous, strengthen supervisory institutions, increase the transparency of CB frameworks and fortify CB investor protection mechanisms (European Commission Citation2015a, p. 23; European Commission Citation2018; Chesini and Giaretta Citation2020, pp. 63–69).

Concluding analysis

While proponents liken CBs to ‘efficient allocation of capital and, ultimately, economic development and prosperity‘ (Thickett Citation2013), this article has highlighted the instrument’s complex, multifaceted, contradictory and paradoxical impacts on Europe’s financial system(s). CBs’ macroprudential characteristics, including low volatility, exceptionally low transaction execution risk and superb credit rating, decrease refinancing costs and limit banks’ reliance on riskier funding means and interbank markets, especially during turbulent times and crises. As the instrument transforms mortgage loans into collateral for central bank liquidity, CBs are the most important means of central bank collateral in Europe (). The instrument also diversifies investor bases, both in terms of investor types and their geographical settings. For these reasons, CBs have garnered a safe haven reputation as no CB defaulted between 1997 to 2019, although 33 credit institutions that issued CBs defaulted the same period (Moody’s Citation2020). CBs were likewise resilient during the Covid pandemic, as issuance increased in 2020 compared to the previous year (). The ECB only purchased 6 billion euros of CBs in its pandemic emergency purchases program, compared with 1644 billion euros of public sector debt and 46 billion euros of corporate debt (ECB Citation2022b). As central banks terminated pandemic liquidity facilities in the late 2021, CB issuance surged and volatility has generally been lower among CBs than on government bonds in Germany, France, Spain and Italy (ECBC Citation2020, p. 210). Primary markets have generally functioned well amid the outbreak of the war in Ukraine, and CB issuance outside of Europe saw all-time highs in 2022.

As the empirical analysis shows, the institutionalisation of harmonised CBs has been a transnational process since the formation of the EMF in the late 1960s. Although domestic regulators had authority to expedite or thwart CB dissemination, mechanisms of competition and favourable EU regulation had stimulated harmonised CB legislation throughout most of Europe by the mid-2000s. A private sector financial innovation and voluntary policy template prior to the GFC, the promotion of CB markets has lately become a mandatory de-risking pillar in EU’s capital market harmonisation policies which is mirrored in the regulatory privileges that the instrument enjoys (EBA Citation2016, p. 85, ECBC Citation2020, p. 136). Being a key component of Europe’s neoliberal mode of regulation, the proliferation of CB markets contributes to sustain financial accumulation by providing financial systems with safe collateral (Gabor and Vestergaard Citation2018) and investment opportunities, which extends issuance, both in normal times as during periods of crisis. CBs have likewise decelerated the institutionalisation and maturation of securitisation markets throughout Europe (Diaz-Granados Citation1996, pp. 20–21, ECB Citation2011, p. 16, ABN AMRO Citation2012, p. 4, DNB Citation2021, pp. C1; FI; H1) and in several jurisdictions, outcompeted them altogether (C1). However, institutions that are meant to reduce some types of instability may eventually introduce others (Ferri and Minsky Citation1992, Palley Citation2011, Skyrman Citation2022, Dafermos et al. Citation2023) and herein lays the destabilising effects of CBs. As a long-term credit instrument suitable to mortgage and real estate lending, or as the European Commission (Citation2023) puts it, ‘a key instrument to channel funds to the property market’, CBs have destabilising macrofinancial effects as they fuel economies’ credit supplies and thereby accelerate household indebtedness, as mortgage lending is the primary activity of the contemporary banking sector in general (Lapavitsas Citation2013), and CB issuers in particular. Household debt accumulation, increased mortgage costs and inevitable swings in housing prices have large implications for consumption, GDP and macroeconomic fragility (Bostic et al. Citation2009, Dam et al. Citation2011).

While ECB’s large purchases of CBs () have resulted in an undersupply of the product, near-zero returns for investors and disturbed liquidity, investor demand is increasing rapidly (C3; H1) as interest rates are normalising and central banks retreat from unconventional monetary policies – the ECB ended CBPP3 purchases in 2022, contributing to higher issuance in 2022 than in the previous year. Macrofinancial and geopolitical uncertainty is also likely to further increase investor demand in CBs, as is decreasing deposit savings amid recessions, inflation and rising energy bills, making banks dependent on alternative funding sources to depositors (H1). As CB legislation is spreading throughout the world, CBs may contribute to accelerated mortgage lending, rising housing prices, while promoting the home ownership model, which is far from beneficial to subaltern classes. Further critical research into covered bonds is therefore imperative to investigate the instrument’s implications for financial systems, household financialisation and securitisation, not least beyond Europe.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Aaron Pitluck, Markus Kallifatides, Rasmus Nykvist, Colin Hay and other editors at New Political Economy, the colleagues commenting at the 34th SASE annual conference, and not least the two anonymous reviewers that provided valuable manuscript feedback.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aalbers, M.B., 2019. Financial geography II: financial geographies of housing and real estate. Progress in human geography, 43 (2), 376–387.

- ABN AMRO. 2012. Covered bonds in the Netherlands. September 2012.

- Alvesson, M., and Kärreman, D., 2011. Qualitative research and theory development. London: Sage.

- Arndt, F.J., 1999. The German Pfandbrief and its issuers. Housing finance international, 13 (3), 14.

- Avesani, R.G., Pascual, A.G., and Ribakova, E., 2007. The use of mortgage covered bonds (No. 2007/020). Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund.

- The Banker, 2005. Spain – Spain's covered bond bonanza. Anonymous London, 155 (952), 69–70.

- Bieling, H.J., 2003. Social forces in the making of the new European economy: the case of financial market integration. New political economy, 8 (2), 203–224.

- Bieling, H.J., 2013. European financial capitalism and the politics of (de-) financialization. Competition & change, 17 (3), 283–298.

- Bieling, H.J., and Guntrum, S., 2020. European crisis management and the politics of financialization. In: S. Wöhl, et al., eds. The state of the European Union. Wiesbaden: Springer VS, 133–154.

- Blackwell, T., and Kohl, S., 2018. The origins of national housing finance systems: a comparative investigation into historical variations in mortgage finance regimes. Review of international political economy, 25 (1), 49–74.

- Boesel, N., Kool, C., and Lugo, S., 2018. Do European banks with a covered bond program issue asset-backed securities for funding? Journal of international money and finance, 81, 76–87.

- Bostic, R., Gabriel, S., and Painter, G., 2009. Housing wealth, financial wealth, and consumption: new evidence from micro data. Regional science and urban economics, 39 (1), 79–89.

- Braun, B., 2020. Central banking and the infrastructural power of finance: the case of ECB support for repo and securitization markets. Socio-economic review, 18 (2), 395–418.

- Braun, B., Gabor, D., and Hübner, M., 2018. Governing through financial markets: towards a critical political economy of Capital Markets Union. Competition & change, 22 (2), 101–116.

- Brown, M., 2004. Covered bonds face an identity crisis. London: Brown, Mark Euromoney. 71–94.

- Buch-Hansen, H., and Wigger, A., 2011. The politics of European Competition regulation: a critical political economy perspective. London: Routledge.

- Chacko, P., and Jayasuriya, K., 2018. A capitalising foreign policy: regulatory geographies and transnationalised state projects. European journal of international relations, 24 (1), 82–105.

- Chambers, A., and Wookey, J., 2007. Covered bonds: call for covered bond calm in face of delay Chambers, Alex; Wookey, Jethro. London: Euromoney.

- Chesini, G., and Giaretta, E., 2020. Recent innovation in the regulation of covered bonds in Europe: who will benefit from the new legislative framework?. In: C. Cruciani, G. Gardenal, and E. Cavezzali, eds. Banking and beyond. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 49–73.

- Crouch, C., 2009. Privatised Keynesianism: an unacknowledged policy regime. The British journal of politics and international relations, 11 (3), 382–399.

- Dafermos, Y., Gabor, D., and Michell, J., 2023. Institutional supercycles: an evolutionary macro-finance approach. New political economy, 1–20.

- Dagens Industri. 2001. Börs & Finans: Blandade känslor inför ny obligation. Jul 25, 2001.

- Dam, N.A., et al., 2011. The housing bubble that burst: can house prices be explained? And can their fluctuations be dampened? Danmarks Nationalbank monetary review. 1st Quarter Part 1.

- Diaz-Granados, R., 1996. A comparative approach to securitization in the United States, Japan, Germany, and France. Willamette bulletein international law & policy, 4, 1.

- DNB. 2021. More packaged loans from buy-to-let mortgage. De Nederlandsche Bank. 31 March 2021.

- Dobbin, F., Simmons, B., and Garrett, G., 2007. The global diffusion of public policies: social construction, coercion, competition, or learning? Annual review of sociology, 33, 449–472.

- Durand, C., and Keucheyan, R., 2015. Financial hegemony and the unachieved European state. Competition & change, 19 (2), 129–144.

- EBA, 2016. Eba report on covered bonds. Recommendations on harmonisation of covered bond frameworks in the EU. Paris: European Banking Authority.

- ECB. 1998. Speech delivered by Dr. Tommaso Padoa-Schioppa, Member of the Executive Board of the European Central Bank, at the Annual General Meeting of the European Mortgage Federation on 6 November 1998 in Brussels.

- ECB. 1999. Possible effects of EMU on the EU banking systems in the medium and long term. Speech delivered by Ms Sirkka Hämäläinen, Member of the Executive Board of the European Central Bank, at the General Assembly of the European Mortgage Federation, Brussels, on 5 November 1999.

- ECB. 2004. Speech by Gertrude Tumpel-Gugerell, Member of the Executive Board of the ECB European Mortgage Federation Annual Conference “Capital Markets and Financial Integration in Europe” Genval, 23 November 2004.

- ECB. 2005. Mortgage markets and monetary policy: a central banker’s view. Speech by Otmar Issing, Member of the Executive Board of the ECB, European Mortgage Federation Annual Conference, Brussels, 23 November 2005.

- ECB. 2011. Recent developments in securitization, Discussion paper.

- ECB. 2022a. Eurosystem collateral data.

- ECB. 2022b. Pandemic emergency purchase programme (PEPP).

- ECBC. 2020. European covered bond fact book. Brussels: European Covered Bond Council.

- Eisenhardt, K.M., and Graebner, M.E., 2007. Theory building from cases: opportunities and challenges. Academy of management journal, 50 (1), 25–32.

- Engelhard, F., and Sattler, F., 2020. Epilogue: the long-term historical transformation of Pfandbriefe. Berlin: VPD, The German Pfandbrief Banks.

- Epstein, G.A., 2005. Financialization and the world economy. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Euromoney. 1994. Sponsored supplement – the German Pfandbrief. Euromoney. Issue 306, (Oct 1994): S1.

- Euromoney. 1995. Bringing the German Pfandbrief to the International Market. Issue 314, (Jun 1995): 104.

- European Commission. 2015a. Appendix. Economic analysis accompanying the consultation paper on covered bonds in the European Union. June 2015.

- European Commission. 2015b. Green paper ‘Building a Capital Markets Union’. COM(2015) 63 final, 18 February, Brussels.

- European Commission. 2018. Proposal for a Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council on the issue of covered bonds and covered bond supervision and amending Directive 2009/65/ EC and Directive 2014/59/EU, Brussels, 12 March 2018, COM (2018) 94 final.

- European Commission. 2023. Covered bonds. https://finance.ec.europa.eu/banking-and-banking-union/banking-regulation/covered-bonds_en#overview Retrieved 2023-05-4.

- Euroweek. 2005. Towards a more harmonised market? 29 April 2005.

- Euroweek. 2006. Nordea Hyp to internationalise Swedish covered bonds. 10/13/2006.

- Farnham. 2005. ABN AMRO to launch Netherlands first-ever structured covered bond programme. Banking Newslink. 30 Aug 2005.

- Fastenrath, F. 2019. The political economy of the state-finance nexus: Public Debt, Crisis and Bank Business Models (Doctoral dissertation, Universität zu Köln).

- Favara, G., and Imbs, J., 2015. Credit supply and the price of housing. American economic review, 105 (3), 958–92.

- Ferri, P., and Minsky, H.P., 1992. Market processes and thwarting systems. Structural change and economic dynamics, 3 (1), 79–91.

- Fuller, G.W., 2015. Who’s borrowing? Credit encouragement vs. credit mitigation in national financial systems. Politics & society, 43 (2), 241–268.

- Gabor, D., 2021. The wall street consensus. Development and change, 52 (3), 429–459.

- Gabor, D., and Vestergaard, J., 2018. Chasing unicorns: the European single safe asset project. Competition & change, 22 (2), 139–164.

- Gaffney, J. 2007. New Law Boosts U.K. Covered Bond Volumes: Covered bonds and SIVs are gaining considerable ground. Gaffney, Jacob. Asset Securitization Report; New York (Jul 30, 2007): 1.

- Haerter, N., 2020. Ceci n’est pas un capital markets union: re-establishing EU-led financialization. Competition & change, 24 (3-4), 248–267.

- Hameiri, S., 2020. Institutionalism beyond methodological nationalism? The new interdependence approach and the limits of historical institutionalism. Review of international political economy, 27 (3), 637–657.

- Hameiri, S., and Jones, L., 2016. Global governance as state transformation. Political studies, 64 (4), 793–810.

- Howarth, D., and Quaglia, L., 2016. The comparative political economy of Basel III in Europe. Policy and society, 35 (3), 205–214.

- Hübner, M. 2016. Securitisation to the rescue: the European capital markets union project, the Euro crisis and the ECB as “macroeconomic stabilizer of last resort”.

- Jabko, N., 2006. Playing the market: a political strategy for uniting Europe, 1985–2005. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Johnston, A., Fuller, G.W., and Regan, A., 2021. It takes two to tango: mortgage markets, labor markets and rising household debt in Europe. Review of international political economy, 28 (4), 843–873.

- Justiniano, A., Primiceri, G.E., and Tambalotti, A., 2019. Credit supply and the housing boom. Journal of political economy, 127 (3), 1317–1350.

- Karwowski, E., Shabani, M., and Stockhammer, E., 2020. Dimensions and determinants of financialisation: comparing OECD countries since 1997. New political economy, 25 (6), 957–977.

- Kohl, S., 2020. Too much mortgage debt? The effect of housing financialization on housing supply and residential capital formation. Socio-economic review, 19 (2), 413–440.

- Lapavitsas, C., 2013. Profiting without producing: how finance exploits us all. Verso Books.

- Lassen, T., 2005. Specialization of covered bond issuers in Europe. Housing finance international, 20 (2), 3.

- Lavoie, M., 2009. Introduction to post-Keynesian economics. New York: Springer.

- Lysandrou, P., and Nesvetailova, A., 2015. The role of shadow banking entities in the financial crisis: a disaggregated view. Review of international political economy, 22 (2), 257–279.

- McCann, E., and Ward, K., 2013. A multi-disciplinary approach to policy transfer research: geographies, assemblages, mobilities and mutations. Policy studies, 34 (1), 2–18.

- McLannahan, B. 2007. Seeking cover. Ben McLannahan. Institutional Investor – International. January 11, 2007.

- Metz, C. 2018. Reviving the European securitisation market after the financial crisis? Regulation, lobbying and the public-private legitimation of finance. The University of Manchester (United Kingdom).

- Mian, A., and Sufi, A., 2018. Finance and business cycles: the credit-driven household demand channel. Journal of economic perspectives, 32 (3), 31–58.

- MoF. 1997. “SOU 1997:110 – Säkrare obligationer?” The Swedish Ministry of Finance.

- Moody’s. 2020. Research announcement: Moody's – covered bond downgrade rates lower than issuer downgrade rates.

- Mügge, D., 2006. Reordering the marketplace: competition politics in European finance. Journal of common market studies, 44 (5), 991–1022.

- Mügge, D., 2013. The political economy of Europeanized financial regulation. Journal of European public policy, 20 (3), 458–470.

- Nölke, A., Heires, M., and Bieling, H.J., 2013. The politics of financialization. Competition & Change.

- Nunn, A., 2020. Neoliberalization, fast policy transfer and the management of labor market services. Review of international political economy, 27 (4), 949–969.

- Palley, T.I., 2011. A theory of Minsky super-cycles and financial crises. Contributions to political economy, 30 (1), 31–46.

- Pape, F., 2020. Rethinking liquidity: a critical macro-finance view. Finance and society, 6 (1), 67–75.

- Posner, E., 2005. Sources of institutional change: the supranational origins of Europe's new stock markets. World politics, 58 (1), 1–40.

- Quaglia, L., 2012. The ‘old’ and ‘new’ politics of financial services regulation in the European Union. New political economy, 17 (4), 515–535.

- Raza, W., 2016. Politics of scale and strategic selectivity in the liberalisation of public services – the role of trade in services. New political economy, 21 (2), 204–219.

- Riksbank. 1998. Remiss av betänkandet Säkrare obligationer? (SOU 1997:110).

- Riksbank, 2014. From A to Z: the Swedish mortgage market and its role in the financial system. Riksbank studies, April.

- Segré, C. 1966. The development of a European capital market. Report of a Group of Experts appointed by the EEC Commission.

- SFI. 2006. Bank of Italy softens stance on covered bonds. Structured Finance International; London (Sep/Oct 2006): 1.

- Skyrman, V., 2022. Industrial restructuring, spatio-temporal fixes and the financialization of the North European forest industry. Competition & change, 0 (0). https://doi.org/10.1177/10245294221133534.

- Smallhoover, J.J., and Cano, C., 1999. France seeks to create its own Pfandbriefe market Smallhoover, Joseph J; Cano, Christian. International financial law review, 18 (8), 15–17.

- Sokol, M., 2022. Financialisation, central banks and ‘new’ state capitalism: The case of the US Federal Reserve, the European Central Bank and the Bank of England. Environment and planning A: economy and space, 0 (0). https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X221133114.

- Stöcker, O.M., 2001. The renaissance of the “Pfandbriefe” in Europe. Housing finance international, 15 (4), 30.

- Stöcker, O., 2019. Towards harmonisation of covered bonds in Europe. Housing finance international, Winter, 24–30.

- Stockhammer, E., Durand, C., and List, L., 2016. European growth models and working class restructuring: an international post-Keynesian political economy perspective. Environment and planning A: economy and space, 48 (9), 1804–1828.

- Thickett, R. 2013. Luca Bertalot: covered bonds take the centre stage. Mortgage Strategy. May 15 2013.

- Van Apeldoorn, B., and Horn, L., 2007. The marketisation of European corporate control: a critical political economy perspective. New political economy, 12 (2), 211–235.

- VPD, 2020. Milestones in the history of the Pfandbrief. Brussels: VPD, The German Pfandbrief Banks.

- Wainwright, T., 2015. Circulating financial innovation: new knowledge and securitization in Europe. Environment and planning A: economy and space, 47 (8), 1643–1660.

- Walker, M., 1999. Germany's secret gamblers: Germany's mortgage banks don't seem to care about loans to home owners any more. Euromoney, 22–29.