ABSTRACT

This article explains independent Uzbekistan’s transformation starting from its integration into the global economy as a primary commodity exporter. It argues that, in line with other resource-rich countries of the Global South, this transformation exhibited two enduring and interlinked features, namely rent-subsidised ‘backward’ industrialisation and the rise of a vast relative surplus population (RSP). First, the end of collective agriculture expropriated most of the Uzbek rural population from the land, so rents from cotton exports could subsidise ‘backward’ industries manufacturing for the domestic market. Second, as these industries could only absorb a minority of the population due to their limited (largely domestic) scale of production, the majority was turned into a vast RSP that struggles in the informal sector, including as labour migrants. Third, cotton’s replacement by gold and natural gas as the main export commodities laid the basis for the current liberalisation. Still, Uzbekistan endures as a raw material exporter, hence as a ‘backward’ industrialiser and reservoir of RSP. As such, the paper problematises the transition literature’s framing of Uzbekistan as an example of failed reform or successful developmentalism, showing instead how these enduring features of its development paralleled similar dynamics in other raw-material-exporting countries of the Global South.

Introduction

Since attaining independence in 1991, Uzbekistan has undergone a major transformation from a largely agricultural economy to a country with a significant industrial base, particularly in new sectors such as the car industry with the participation of Multinational Corporations (MNCs). In parallel, the working class suffered a collapse in living standards, from full employment and low migration rates during Soviet times to today’s mass informalisation of economic activity, including the migration of millions to find seasonal employment especially in Russia. In trying to explain this transformation, the literature on transition from the Soviet command economy to capitalism largely followed the orthodox-heterodox binary found in the literature on development.

On the one hand, orthodox scholars asserted that, during the Karimov presidency (1991–2016), Uzbekistan used the income accrued from its rich resource endowment to avoid the transition to free-market capitalism (Blackmon Citation2005, Citation2011, Pomfret Citation2019). In this perspective, the liberalisation of the cotton sector and foreign exchange initiated under current President Mirziyoyev (2016–present) represents either the potential start of genuine reform (Tsereteli Citation2018) or a case of authoritarian upgrading to preserve the same authoritarian system (Anceschi Citation2019). On the other hand, while admitting that more needs to be done to develop labour-intensive industries to absorb workers especially from rural areas (Cornia Citation2003), heterodox scholars retorted that the government of Uzbekistan (GoU) invested primary commodity rents to engineer the country’s industrialisation, as evident in the creation of enterprises including in high-tech production such as cars. In this view, the current liberalisation is building on the achievements of the Uzbek developmental state to continue this process of ‘upgrading’ along the industrial value chain, in the hope of emulating the success of other late-industrialising countries in East Asia (Lombardozzi Citation2019, Citation2021). Despite their differences, however, orthodox and heterodox transition scholars share the view that the key challenge in Uzbekistan derives from the ‘underdevelopment’ of capitalism in the country, evident in the prevalence of raw material exports, (at least so far still largely) uncompetitive industries, and mass informality and migration. As such, methodologically, the focus has been on whether the state has thus far failed (orthodox) or managed (heterodox) to start addressing this challenge by mustering the transformative potential of the world market, which, in turn, has been framed as the external context of a state’s development.

In contrast to the transition literature’s methodological nationalism (Pradella Citation2014), I deploy Iñigo Carrera’s (Citation2013, Citation2016, Citation2017) original interpretation of Marx that explains the common dynamics of transformation in resource-rich countries in the past decades – ‘backward’ import-substitution industrialisation (ISI) including with MNC participation and the rise of vast relative surplus populations (RSPs) – as specific national forms within the global process of capital accumulation, commonly referred to in the political-economy literature as ‘globalisation’ (Fine Citation2013). Fundamentally, for resource-rich countries this transformation has been linked to changes to land use in order to produce raw materials for export, whose rents (ground-rent) have gone to subsidise technologically ‘backward’ manufacturing for the domestic market. In turn, due to their limited (largely domestic) scale, these ‘backward’ industries could only absorb a minority of the population expropriated from the land for the production of primary commodities, giving rise to vast RSPs.Footnote1 As such, this paper shows how the insights gained from the analysis of the relatively understudied case of Uzbekistan can contribute to our understanding of similar dynamics in other countries integrated into the global economy as raw materials exporters (‘resource-rich’ countries).

The rest of the paper is organised as follows. Section 1 reviews the literature on transition in Uzbekistan along the orthodox-heterodox binary. Section 2 introduces an alternative framework pioneered by Iñigo Carrera to analyse Latin America, which enables the theorisation of the dynamics of change in resource-rich countries in the past decades – ‘backward’ ISI and the rise of vast RSPs – as specific national forms within the process of capital accumulation on a global scale (‘globalisation’). Section 3 then shows how, in contrast to the transition literature, this framework can account for the enduring features of transformation in independent Uzbekistan, as a raw material exporter to the world market hence a ‘backward’ industrialiser with a vast RSP. The conclusion summarises the article’s main findings.

The literature on transition in Uzbekistan: failed reform or successful developmentalism?

The boom in primary commodity prices during the 2000s and 2010s in the wake of China’s meteoric industrialisation gave rise to a lively debate in the development literature on the use of income accrued from the export of primary commodities to finance late industrialisation in the Global South (Singh and Ovadia Citation2018, Jepson Citation2020, Lebdioui Citation2022). As with previous discussions on the rise of East Asia as an industrial hub in recent decades, orthodox economists continued cautioning against industrial policy as market distortions, more often than not, result in rent-seeking rather than development (Rodrik Citation2009, p. 8), thus wasting any windfall from high commodity prices. For their part, heterodox economists argued in favour of ‘state intervention as a policy strategy to maximise rents and to pursue structural transformation’ in order to achieve resource-based industrial development (Singh and Ovadia Citation2018, p. 1046), building on the previous success of South Korea and other ‘developmental’ states in Asia. As such, ‘industrial policy through natural resources can generate the big push for African and Latin American countries to capture more value in the global supply chain’ (Singh and Ovadia Citation2018, p. 1046).

The literature on the transition from the command to the market economy in Uzbekistan replicates this orthodox-heterodox split, particularly as the commodity supercycle witnessed a significant uptick in industrial production and investment in the country. Orthodox scholars viewed the policies introduced under the so-called ‘Uzbek model’ during the presidency of Islam Karimov (1991–2016) as Soviet-style distortionary subsidies for industries, which ran counter to the (trade and price) liberalisation and privatisation deemed vital to spur growth and development. It was the presence of ‘mobile’ raw materials that explained reform failure in Uzbekistan, as cotton and, to a lesser but still significant extent, gold could be readily shifted from the Soviet to the international market in exchange for hard currency, securing enough rents for the government to avoid or delay reform (Blackmon Citation2005, pp. 395–6, Pomfret Citation2019, pp. 57, 117). At the heart of the Uzbek model lay the cotton sector, which both epitomised and guaranteed Soviet continuity after independence. ‘In theory, Uzbekistan has been gradually liberalising the Soviet-era cotton industry structure, breaking up state and collective farms and demonopolising the buying process. In practice, almost nothing has changed for the average farmer since the Soviet period’ (ICG Citation2005, p. 3, emphasis added, Blackmon Citation2011, pp. 29, 95–6).

Instead of the price mechanism allocating resources efficiently to foster economic diversification, the Central Bank (CBU) and the state-owned National Bank (NBU) of Uzbekistan used a complex system of multiple exchange rates to subsidise the development of import-substitution industrial sectors, such as car manufacturing, within a protected domestic market (Trushin Citation2018). These distortionary policies created fertile ground for corruption that benefitted the elites to the detriment of the population and the country’s overall development, as evident in the lack of international competitiveness of Uzbek industry (Blackmon Citation2011, Hoen and Irnazarov Citation2012). Likewise, the spread of informality and mass rural outmigration have been the ‘most striking symptom’ of policy ‘failure’ (Pomfret Citation2019, p. 115). Equally wasteful was the attempt to divert land from cotton to wheat cultivation in order to achieve grain self-sufficiency (Pomfret Citation2019, pp. 98–9). Once President Shavkat Mirziyoyev (2016–present) came to power after his predecessor’s death in 2016, orthodox scholars averred that the liberalisation of the cotton sector and the exchange rate regime represented either the potential start of genuine, if long-delayed, reforms (Tsereteli Citation2018), or ‘the leadership’s preferred measure to carry out an extensive process of authoritarian modernisation’ (Anceschi Citation2019, p. 117). Either way, the key challenge for Uzbekistan continues to be the ‘underdevelopment’ of capitalism in the country evident in the lack of economic diversification away from raw material exports, uncompetitive industries, and mass informality and migration, which, whether genuinely or simply in order to preserve the same authoritarian system, the GoU is only now starting to address.

In parallel to the commodity price boom, a minority of heterodox scholars started framing Uzbekistan as a developmental state, which allocated rents from the sale of cotton on international markets in order to engineer economic modernisation via late industrialisation, especially in higher value-added manufacturing. As such, market-distorting state intervention was precisely the reason for the success of the Uzbek model, which managed to transform Uzbekistan into Central Asia’s most diversified economy (Spechler Citation2010). While some of these scholars acknowledged the social dislocations occurring in the country, such as mass informalisation of economic activity and labour migration particularly from rural areas, the key would be further diversification into ‘sectors that are resource-, skilled labour- and semiskilled labour-intensive’ to absorb this vast workforce (Cornia Citation2003, p. 107). Still, the state already provided ‘decent levels of welfare’ for the population, including the subsidised production of wheat and derivative products (Lombardozzi Citation2019, p. 64).

With high commodity prices translating into sustained growth and rising investments in industrialisation, increasingly from the export of gold and natural gas, by the 2010s some heterodox scholars began speaking of an Uzbek ‘miracle’. Uzbekistan’s performance was ‘truly exceptional for the post-Soviet space’, with industrialisation figuring at the centre of this ‘economic success story’ (Popov Citation2013, p. 5). Despite largely remaining an exporter of raw materials, the country managed to increase ‘the share of industry in GDP and the share of machinery and equipment in the total industrial output, and export’, especially with the creation of ‘a competitive export-oriented auto industry from the ground up’ and some diversification of the domestic economy (Popov and Chowdhury Citation2016, p. 5). In other words, in line with developmental state theory, export orientation remained both the key aim and the litmus test of successful late industrialisation, a point largely shared by the GoU (CER Citation2013).

Therefore, the current liberalisation under President Mirziyoyev is building on the previous achievements of the Uzbek model to accelerate the process of economic upgrading, in the hope of emulating the experience of other developmental states in East Asia such as South Korea (Lombardozzi Citation2019, Citation2021, p. 951). Again, for heterodox transition scholars, ‘underdevelopment’ continues to be the key challenge for Uzbekistan, whose leadership needs to keep pursing the upgrading of the country’s industrial base in order to realise the promise of late industrialisation, namely a move away from raw material to manufactured good exports and a general improvement in living standards.

In effect, while rightly acknowledging the centrality of raw materials to Uzbekistan’s political economy, the transition literature fails to connect this form of production for export to the specific ways in which the country was transformed during the past three decades. Instead, orthodox and heterodox scholars alike mistake the establishment of rent-subsidised import-substitution industries largely manufacturing for the domestic market and the rise of a vast RSP that works informally including as labour migrants as deficiencies in an essentially national process of accumulation in Uzbekistan, which the state is now starting (orthodox) or continuing (heterodox) to address. The next section introduces a different theoretical approach that, I argue, can elucidate the crucial connection between Uzbekistan’s participation in the global economy as a raw material exporter and the enduring, interconnected features of its transformation evident in ‘backward’ industrialisation and the presence of a vast RSP, making the insights gleaned from this understudied case relevant for other resource-rich countries of the Global South in the past decades.

The political-economy of transformation in resource-rich countries: ‘backward' industrialisation and relative surplus populations

The issue with the literature on transition in Uzbekistan is that, methodologically, it regards the process of capital accumulation (‘development’) as essentially national, with state policies independently determining domestic economic outcomes. Since in the world market all countries are assumed to ‘face the same external environment’ (Gore Citation1996, p. 81), state policies become the key focus for any analysis of success or failure in national development, as is the case for the orthodox and heterodox literature on Uzbekistan. However, the process of capital accumulation is national in form, but global in content (Burnham Citation1994, Bonefeld Citation2014). As such, rather than being independent variables, state policies mediate the ongoing process of integration of the world market, which appears in the formation of an International Division of Labour (IDL) between countries according to their participation in the process of capital accumulation on a global scale (‘globalisation’), in line with the specific characteristics of their working class or the relatively favourable natural conditions for the production of raw materials within their territories (Grinberg Citation2013).

Historically, the IDL appeared in the polarisation of the world economy between an industrialised Global North, on the one hand, and a Global South ‘confined to the role of supplier of raw materials and staple foods’, on the other (Charnock and Starosta Citation2016, p. 3). In the past decades, one of the most significant changes to this ‘classical’ IDL has been the relocation of specific tasks in large-scale industrial production from the Global North to East Asia including, initially, South Korea and Taiwan, then Thailand, Malaysia and Indonesia, and more recently China, whose meteoric industrialisation resulted in its share of total world export soaring from 4 per cent in 2000 to a staggering 14.7 per cent 20 years later (Nicita and Razo Citation2021). Assessments of this transformation in the literature are also largely split along the orthodox-heterodox binary. The orthodox literature generally argues that the East Asian governments made good use of international markets to engineer the late industrialisation of their economies (World Bank Citation1995). For their part, heterodox scholars retort that a strong interventionist (‘developmental’) state was instead central to this process (Wade Citation2014). Still, despite this diversity of opinions, there is general agreement that the availability of a cheap and pliant, hence highly productive, labour force was a crucial ‘comparative advantage’ for the region, which allowed it to become an industrial powerhouse in the space of only a few decades (World Bank Citation1993a, Chan and Nadvi Citation2014, Beeson Citation2017).

One of the most obvious manifestations of this globalisation of industrial production has been the rise and proliferation of MNCs and their global productions networks (Grinberg Citation2013, p. 182), which have driven the demand for energy and raw materials to meet the requirements of their constantly expanding scale of production and, as a result, contributed to the staggering growth in material throughput in the global economy (Conti et al. Citation2016, OECD Citation2019). Most of the primary commodities used in these ‘global factories’ come from resource-rich countries in the Global South which, contrary to fast-industrialising East Asia, continued to be, or upon independence have been, integrated into the IDL as producers of raw materials for export, on the basis of the relatively favourable natural conditions for the production of primary commodities found in their territories, as has been the case of Uzbekistan. The originality of Iñigo Carrera’s (Citation2013, Citation2016) argument lies in identifying how this form of incorporation into the IDL defined the process of accumulation within resource-rich countries, such as those in Latin America. These were turned into sources of appropriation of ground-rent (more on this below), hence into the locus of rent-subsidised ‘backward’ industries largely manufacturing for the domestic market and, consequently, into reservoirs of relative surplus populations (RSPs) that could not be incorporated into these industries due to their limited (largely domestic) scale of production. As such, ‘backward’ industrialisation and the presence of vast RSPs are the interlinked and enduring features of the transformation of resource-rich countries in the world market in the past decades, rather than the outcome of ‘underdevelopment’ in these raw-material-exporting states.

Therefore, as explained, rather than independently setting their development ‘paths’, the national state in resource-rich countries mediated the global process of capital accumulation via specific policies that guaranteed the latter’s continuous reproduction and expansion. While under ‘normal’ conditions of production, it is the best (that is, most competitive) capitals that set the general prices of commodities, the international prices of raw materials are established instead within ‘marginal’ conditions due to the centrality of land in their production. This simply means that primary commodity prices must rise to incorporate a ground (that is, land) rent for the landlord of the worst (‘marginal’) lands that need to be put into production to meet global solvent demand, as no landowner – even of these least-productive lands – would allow their plots to be used for production without being paid a rent (Iñigo Carrera Citation2017). In developing countries particularly in Africa and Asia, but also in Latin America in regard to mines and oil and gas wells, often it is the state that holds legal ownership of the land and, as such, is the landlord (Moyo Citation2012). As a result, and depending on global solvent demand, the (landlord) state in resource-rich countries accrues a fluctuating magnitude of ground-rent from the sale of primary commodities on the world market due to its absolute monopoly on the differentially favourable natural conditions (fertility, location) of production on its lands.Footnote2 In turn, the state mediates its integration into the IDL as a raw material exporter via specific policies that directly and indirectly allocate this ground-rent to subsidise the process of production and consumption – that is, capital accumulation – within its borders (Iñigo Carrera Citation2017).

These policies include the purchase of primary commodities at fixed lower prices in the domestic market for resale at international prices in the world market – as has been the case for cotton, gold and natural gas in Uzbekistan (Section 3 ‘Uzbekistan as a resource-rich country in the International Division of Labour: from the “Uzbek Model” to “Liberalisation”’) – which allows the state to appropriate the difference (that is, ground-rent) and redistribute it via state-owned and other domestic banks as credit to firms at low or negative interest rates. Equally, the overvaluation of the national currency including via a multiple exchange rate system enables enterprises operating on the domestic market – be they national or multinational corporations, or joint-ventures (JVs) between them – to import inputs such as parts, components, and industrial machinery at subsidised prices. As such, MNCs could import machinery obsolete for world market production to put it to use in the domestic market instead (Grinberg Citation2016, Iñigo Carrera Citation2016), as in the case of the Uzbek car industry in JV with Korean Daewoo and American General Motors (Section 3 ‘Uzbekistan as a resource-rich country in the International Division of Labour: from the “Uzbek Model” to “Liberalisation”’). Moreover, the sale of inputs, including utilities, produced from locally-sourced raw materials by State-Owned Enterprises (SOEs) at subsidised rates further supports industrial capitals in resource-rich countries. Finally, as long as the provision of subsidised utilities is also extended to the general population, along with the supply of subsidised food staples it contributes to lowering the cost of labour for manufacturing enterprises, which can pay a proportionately lower wage for workers in view of these consumption-based subsidies (Grinberg Citation2016, Iñigo Carrera Citation2016). Subsidised inputs and utilities in Uzbekistan, as well as subsidised electricity and wheat for the general population, all contributed to industrial manufacturing in the country (Section 3 ‘Uzbekistan as a resource-rich country in the International Division of Labour: from the “Uzbek Model” to “Liberalisation”’).

The combination of these different mechanisms of direct and indirect subsidisation established specific conditions for the reproduction of manufacturing capitals in resource-rich countries, which could only benefit from these subsidies by operating and selling their commodities mostly within the protected domestic market or, at best, in equally protected regional markets via free trade agreements (FTAs). As such, all these manufacturing capitals – national, multinational, JVs – have been ‘small’ and technologically ‘backward’ by world market norms, producing relatively obsolete goods largely for domestic consumption, a process that Iñigo Carrera (Citation2016) defines as ‘backward’ (import-substitution) industrialisation. As a result, this ‘backward’ industrial production has been ‘structurally dependent on the evolution of the magnitude of ground-rent available for appropriation’ in the domestic economy, so manufacturing output has fluctuated upward or downward in line with the changing international prices of a country’s raw materials (Grinberg and Starosta Citation2009, p. 770). In this perspective, rather than a qualitative change, rising output during a commodity supercycle simply reflects a quantitative increase in the magnitude of ground-rent available in the national market to subsidise ‘backward’ manufacturing, as has been the case of the Uzbek car industry from the early 2000s to the mid-2010s (Section 3 ‘Uzbekistan as a resource-rich country in the International Division of Labour: from the “Uzbek Model” to “Liberalisation”’).

Moreover, resource-rich countries mediated their integration into the IDL as exporters of raw materials via changes to land use that allowed more lands to be put to the production of primary commodities, in order to meet rising solvent demand particularly from ‘global factories’. As a result, first, intensive cash crop production for export has been altering the relatively favourable natural conditions of production on the land, evident in land degradation and collapsing soil fertility worldwide but especially in resource-rich countries (Secretariat of the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification Citation2017). In Uzbekistan, this helps to account for flattening cotton yields in the past decades relative to other cotton producing countries such as China, hence for the decrease in the sector’s importance to Uzbekistan’s export basket and its ensuing liberalisation (Section 3 ‘Uzbekistan as a resource-rich country in the International Division of Labour: from the “Uzbek Model” to “Liberalisation”’). Second, whether under the rubric of Structural Adjustment Programmes (SAPs), decollectivisation as in the former Soviet Union after 1991, or the more recent ‘global land grabs’ (Davis Citation2006, Federici Citation2012, Wolford et al. Citation2013), these land use changes consistently entailed ‘the expropriation of the mass of the people from the soil’ (Marx Citation1867/1976, p. 934), that is, a process of primitive accumulation that led to mass peasant dispossession and rural displacement across the Global South.

Therefore, the majority of the people expropriated from these lands were turned into vast RSPs that struggle to survive amid informality and migration, as only a small percentage thereof could be absorbed by ‘backward’ manufacturing industries due to their limited (largely domestic) scale of production. This resulted in ‘the massive growth of informal economies in the cities’ (Connell and Dados Citation2014, p. 133), to which these populations migrate, both domestically and internationally.Footnote3 As a consequence, by 2018, more than 60 per cent of the world’s active population – or 2 billion people – were working informally, with ‘the share of informal employment in total employment rang[ing] from 50.4 per cent to more than 98 per cent’ in developing and emerging countries (ILO Citation2018, p. 48). Equally, rising international migratory flows account for the huge growth in remittances that migrant workers send back to their families in their countries of origin. In low- and middle-income countries, remittances are now ‘more than three times the size of official development assistance (ODA)’ and ‘significantly larger than FDI flows’ (KNOMAD and World Bank Citation2019, pp. 1, 3). All these developments have been apparent in independent Uzbekistan during the past three decades (Section 3 ‘Uzbekistan as a resource-rich country in the International Division of Labour: from the “Uzbek Model” to “Liberalisation”’).

In sum, resource-rich countries turned into sources of appropriation of ground-rent, hence loci of ‘backward’ industrialisation and reservoirs of RSPs. Contrary to the transition literature, however, these dynamics are not the result of the ‘underdevelopment’ of capitalism in Uzbekistan, which the country’s government may now start (orthodox) or continue (heterodox) to address. Rather, they are the specific, enduring, and interrelated features of national transformation in resource-rich countries of the Global South, which partake in the global process of capital accumulation as producers of primary commodities for export (Iñigo Carrera Citation2013, Citation2016). The next section illustrates how this theoretical framework accounts for the transformation of independent Uzbekistan in the past three decades, providing valuable insights for the study of similar dynamics in other resource-rich countries of the Global South.

Uzbekistan as a resource-rich country in the International Division of Labour: from the ‘Uzbek Model' to ‘Liberalisation'

Historically, Central Asia presented relatively favourable natural conditions for the production of cotton, in light of the region’s abundant water resources and dry, hot climate. While cotton cultivation markedly increased in the nineteenth century under Tsarist Russia’s colonial rule, it experienced a veritable boom during Soviet times. Crucial to it was the building of a monumental canal infrastructure for irrigation, as well as the introduction of significant price incentives for cotton, which, despite significant variations through time, also entailed the purchasing of the crop by Moscow at procurement prices higher than international prices for decades, resulting in the huge expansion of the land under cotton production and rapidly increasing yields (Khan and Ghai Citation1979, Tarr and Trushin Citation2004, Spoor Citation2005, Khan Citation2007, Penati Citation2013). The Uzbek Soviet Socialist Republic (UzSSR) was at the epicentre of this transformation. By the mid-1980s, the UzSSR’s ‘cotton sector produced more than 65 percent of its gross output, consumed 60 percent of all production inputs, and employed approximately 40 percent of the labor force. It also accounted for about two-thirds of all cotton produced in the Soviet Union’ (Ilkhamov Citation2004, p. 165), as well as ‘25 percent of world cotton trade in the 1970s and 1980s’, with yields per hectare ‘among the highest in the world’ (MacDonald Citation2012, p. 2).

During Soviet times, cotton production was organised in state and collective farms via a centralised quota system setting each year’s targets. Rather than being just production units, however, these institutions of collective agriculture provided the infrastructure of rural life, including hospitals, schools, and kindergartens, as well as collective access to the land and the use of inputs to grow the food and animal feed that guaranteed the reproduction of the rural population (Kandiyoti Citation2003). Clearly, as the recurrent issue of society-wide mobilisation including via forced (and child) labour during the autumn cotton harvest demonstrates (Spoor Citation2005), living conditions in the rural areas of the UzSSR were far from ideal or idyllic. Still, since the Soviet state ensured full employment, welfare, and collective access to the land for the rural population in exchange for cotton production (Trevisani Citation2010), the UzSSR exhibited some of the lowest rates of rural-urban migration within the Soviet Union (Craumer Citation1992, Khan Citation2007). Moreover, albeit limited (Zettelmeyer Citation1998, p. 31), the UzSSR’s industrial base was heavily biassed towards agriculture in general and the cotton sector in particular, with the manufacturing of gasoline and fertilisers for farmers, as well as tractors and cotton harvesters dominating the sector (Pomfret Citation2002, Rustemova Citation2012, p. 139).Footnote4

The ‘Uzbek model’: ‘backward’ industrialisation and relative surplus population

As a result, by the time the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, cotton dominated the economy of newly-independent Uzbekistan. As such, state intervention under the so-called Uzbek model during the Karimov presidency continued to guarantee, inter alia, the manufacturing of inputs (fuel, fertilisers) necessary to ‘maintain a persistent supply of raw cotton to secure [the] government’s export revenues’ (World Bank and IAMO Citation2019, p. 38). However, the Uzbek model did not determine the transition; rather, it mediated it within the material conditions of capital accumulation prevalent in the world market in the 1990s. Only demand for raw materials from Uzbekistan, particularly cotton, remained solvent, due to the relatively favourable natural conditions for the crop’s production, which, albeit depleted – as evident in the ongoing desiccation of the Aral Sea – still constituted the country’s main ‘factor endowment’ for its participation in the International Division of Labour. No such demand existed for Uzbek manufacturers, such as tractors and cotton harvesters, which largely disintegrated along with supply chains in the face of foreign competition and the collapse of the Soviet state (World Bank Citation1993b, CER Citation2004). This explains why continuing to grow cotton ‘made sense’ for the GoU, as the only way to secure the process of production and consumption – that is, capital accumulation – on the territory of newly-independent Uzbekistan that, in turn, guaranteed the viability of statehood.

Therefore, the Uzbek model mediated Uzbekistan’s integration into the IDL as a resource-rich country, which, as a result, turned into a source of ground-rent for ‘backward’ ISI and a reservoir of RSP. Central to this mediation was the purchase of raw materials, especially cotton but also gold and copper, at state-fixed prices on the domestic market in order to sell them at a higher price on the international market and pocket the difference (World Bank Citation1993b, Connolly Citation1997, IMF Citation1998, pp. 48–9), that is, ground-rent.Footnote5 In the cotton sector, the Agricultural Fund of the Ministry of Finance set the procurement price for raw cotton artificially low, while the state sold the annual cotton production on the international market via GoU-controlled trading companies (Muradov and Ilkhamov Citation2014). On top of the state-fixed cut-off price, the CBU also introduced an overvalued ‘official’ exchange rate for the soum, the national currency, to the compulsory surrender of hard currency earned from the sale of raw materials, especially cotton and gold (World Bank Citation2013).

The ground-rent thus appropriated by the Uzbek (landlord) state was used to finance energy and other inputs for cotton production, as well as industrial manufacturing in the form of ‘backward’ ISI, particularly in specific priority sectors of the economy such as the car industry, which received subsidised credits at low or negative interest rates from state-owned and commercial banks (IMF Citation1998). Specifically, both the CBU and the NBU granted preferential credits to state enterprises including via commercial banks (World Bank Citation1993b, IMF Citation1998). Not only did investments in the Uzbekneftegaz (UNG) energy SOE result in a ‘large rise in oil and gas production’ after independence (EIU Citation1997, p. 29), but also UNG’s natural gas extraction provided the feedstock necessary to produce chemical fertilisers for agriculture in cooperation with chemical SOE UzKhimProm (World Bank Citation2013). SOEs guaranteed the production of other cheap inputs for all firms, including small-and-medium enterprises, a crucial form of ground-rent subsidisation that sustained the growth of ‘backward’ ISI manufacturing industries (World Bank Citation2013, p. 16, Trushin Citation2018, p. 16). For example, apart from fertilisers, UzKhimProm’s provision of cheap ammonia helped to develop the domestic production of home cleaning products (Ministry of Trade and UNDP Citationn.d.), while the supply of copper at the Almalyk and Navoi Mining and Metallurgical Companies – the largest mining SOEs in the country – contributed to the manufacturing of industrially-produced wires and inputs for home appliances such as washing machines and fridges (OECD Citation2017, p. 31, Galdini Citation2023).

Along with SOE-produced cheap inputs, UNG’s provision of subsidised gas and ‘gas-fired’ electricity (Pirani Citation2012, p. 58) across the Uzbek economy contributed both to ‘backward’ industrialisation and to lowering the cost of living of the general population, hence the cost of labour for capital (IMF Citation1998). This was reduced further as the GoU switched significant hectarage from cotton to wheat cultivation, which was sold at lower-than-international prices on the domestic market along with derivative products, such as flour and bread produced at state-owned mills and bakeries (Mirkasimov and Parpiev Citation2017). As such, the circulation of gas- and wheat-based products at subsidised prices represents a consumption-based form of ground-rent subsidisation for manufacturing capital, rather than yet another item in the list of the country’s reform failures to be now addressed (orthodox literature) or developmental successes on which the current reforms can continue building (heterodox literature).

The Uzbek car industry epitomises this ‘backward’ form of industrialisation, as well as the fact that all manufacturing capitals in resource-rich Uzbekistan could only stay in business via ground-rent subsidisation, which has been the main incentive for MNCs to invest in the Uzbek market. This was the case of Korean Daewoo Motor Company (DMC) that entered into a JV with UzAvtoSanoat – Uzbekistan’s automotive SOE – to form UzDaewooAvto in the early 1990s. First, at 200 million USD, the JV’s initial capital was small by the industry’s multi-billion-USD international standards (Galdini Citation2023). Second, the JV benefitted from subsidised credit, inputs, and utility provision behind the calibrated protection of the domestic market via high customs duties on the import of finished goods such as cars (UNCTAD Citation1999). Instead, machinery, equipment, and technology were subjected to ‘very low tariffs and individual enterprises [were] often granted tariff exemptions’ (IMF Citation1998, p. 119). Equally, the overvaluation of the national currency provided an implicit subsidy for firms operating on the domestic market to import capital goods such as machinery and other inputs for industrialisation (IMF Citation1998).

In this way, DMC could import tax-free to Uzbekistan ‘machines manufactured by or dismantled from Daewoo’s subsidiaries in Korea’ (Jeong Citation2004, p. 148) that had become obsolete for world market production, in order to manufacture old Daewoo models for the Uzbek market instead. This was the case of the LeMan, for instance, which had been introduced in Korea in 1986 and, a decade later, started production in Uzbekistan under the Nexia brand (Galdini Citation2023). Finally, since its inception in 1996, overall production closely followed the price fluctuations of the country’s raw materials, that is, the magnitude of ground-rent available on the Uzbek market, where most of the manufactured cars were purchased (IMF Citation1998). After surpassing the 50–60 thousand units between 1997 and 1999, on the back of relatively high cotton prices (CER Citation2013, p. 15), at the turn of the millennium car production decreased along with ‘gold and cotton prices, two of Uzbekistan’s principal export earners’ (EIU Citation2001, p. 4), falling far behind the then-total ‘capacity production’ of 200,000 cars per year (EIU Citation2002, p. 24).

For the bulk of ground-rent to be channelled to subsidise capital accumulation in Uzbekistan, however, the Soviet social contract of full employment and welfare provision, including through the use of price incentives for the crop’s purchase, in the context of guaranteed access to the land for the rural population, had to be voided. The dismantlement of the institutions of Soviet collective agriculture via land decollectivisation served this purpose. While the process was uneven, protracted, and included several changes to farm size, it entailed the systematic expropriation of the rural population from the land, which was divided up between small commercial farms via long-term leases for the production of cotton and wheat according to state orders and quotas (Kandiyoti Citation2003, Tresivani Citation2010).Footnote6

Again, as the Uzbek (landlord) state mediated its integration into the IDL as a cotton producer, it guaranteed production and consumption – that is, capital accumulation – within its territory. First, state ownership of the land allowed the state to continue purchasing cotton and wheat from small commercial farmers at below-market prices – contra past Soviet practice for cotton – to sell the former on the international market for hard currency to subsidise ISI, while guaranteeing the circulation of the latter and derivative products at subsidised prices in the domestic market. As such, ground-rent subsidised the production of industrial goods such as cars and, in parallel, lowered the cost of labour for capital on the Uzbek domestic market. Second, with decollectivisation/primitive accumulation, the majority of the rural population was turned into landless peasants available to work for small private farmers (Veldwisch and Bock Citation2011), who used this abundant labour force to produce and profit from the sale of other crops ‘such as maize, rice, vegetables, and potatoes’ cultivated in parallel to cotton or after the wheat harvest (World Bank and IAMO Citation2019, p. 20). Third, as only a minority of these landless peasants could find permanent employment in small private farms, or be absorbed by the country’s domestically-oriented ‘backward’ industries, the majority swelled the ranks of a growing RSP struggling to survive amid informality and migration. By 2006, the number of temporary, casual and seasonal workers in Uzbekistan had surpassed 5.6 million, or more than half of the total workforce (Maksakova Citation2008, pp. 65–8, IMF Citation2008, pp. 27–8). While many moved to the outskirts of the capital Tashkent and its satellite cities in search for work, millions started migrating to Russia and, to a lesser extent, Kazakhstan to find seasonal employment there in construction, trade, and agriculture, as rising oil prices from the 2000s onward fuelled an economic boom in Uzbekistan’s energy-rich northern neighbours (UNDP Citation2018). As a consequence, international migrant workers’ remittances to Uzbekistan grew exponentially, reaching 6.7 billion USD, or 12 per cent of GDP, in 2013 (UNDP Citation2018, p. 113) and dwarfing both ODA and FDIs in line with dynamics in other resource-rich countries (World Bank Citation2018, p. 137).

As such, ‘backward’ industrialisation and the rise of a vast RSP have been the specific and interrelated national forms mediating the global process of capital accumulation in resource-rich Uzbekistan, as a raw material exporter in the IDL. While intensive cotton production continued depleting the relatively favourable natural conditions for the crop’s production in the country, the commodity supercycle that began in the early 2000s changed the weight of gold and natural gas in its export basket, creating the material conditions for the current ‘liberalisation’. It is to this that I now turn.

From the ‘Uzbek model’ to ‘Liberalisation’: different forms, same content

At the turn of the new millennium, international prices for primary commodities began rising in order for production to expand to worst (‘marginal’) lands and satisfy soaring solvent demand, especially from a fast-industrialising China. This was particularly true for energy and metals, whose prices ‘increased much more than those of agricultural’ goods (UNCTAD Citation2019, p. 7). As a result, investments in Uzbekistan’s hydrocarbons and gold sectors significantly grew to contribute to meeting this demand. Whereas during the 1990s low oil and gas prices translated into Uzbekistan’s energy sector being unattractive to foreign investors (EIU Citation1998, p. 30), in the new millennium joint investments between UNG and a number of foreign companies, SOEs, and development banks, particularly from Russia and Asia, picked up speed (EIU Citation2008, p. 36, Pirani Citation2012, pp. 32–5), surging from 190 million USD in 2000 to 16.3 billion USD in 2016 in parallel with the rise in energy prices (UNG Citation2018). This included the construction of the Surgil Natural Gas Chemicals Project in the western Ustyurt Plateau to ‘produce gas for commercial use and for conversion into chemical intermediates used in the plastics and textiles industries’ (ADB Citation2012), providing more subsidised inputs for ‘backward’ manufacturing. Likewise, in September 2012 Uzbekistan started exporting natural gas to China via the Central Asia-China Gas pipeline (EIU Citation2013, p. 18), which has since become a major export market for Uzbek gas, as well as Central Asia’s.

Moreover, ‘as continued loose monetary policy in many economies [enhanced] gold’s attractiveness as a hedge against inflation’ (EIU Citation2013, p. 7), the ensuing rise in gold prices translated into increased investments in exploration and production facilities in Uzbekistan (Safirova Citation2015) both to amass national reserves in gold for financial sterilisation, as well as to export the precious metal for hard currency. Eventually, by 2013, gold and natural gas consistently surpassed raw cotton as the country’s main export commodities, with the former combined accounting for 46.9 per cent of all exports in 2018, or approximately 5 billion USD, against the latter’s 2.14 per cent, or 225 million USD (Observatory of Economic Complexity data). On the back of the commodity price bonanza Uzbekistan’s national reserves almost doubled between 2010 and 2017 from 14.2 to 27.7 billion USD (Central Bank of the Republic of Uzbekistan data), including from the difference between the domestic cut-off prices and the international prices of commodities such as gold and natural gas, that is, ground-rent. These reserves were held in the CBU, the NBU, and the Fund for Reconstruction and Development of Uzbekistan (UFRD), a sovereign wealth fund created in 2006 specifically to reinvest these resources into the Uzbek economy, particularly in energy and mining in JV with foreign investors (Shaismatov Citation2018).

Consequently, ‘backward’ industrial production fluctuated steeply upward during this period along with the mass of ground-rent inflowing into Uzbekistan, whose redistribution the GoU continued mediating largely via the same specific state policies such as the overvaluation of the national currency. It is during this commodity supercycle that car production markedly grew now under the American General Motors (GM) brand, which had acquired DMC after the latter’s bankruptcy in 2000 and entered the Uzbek market in 2007 to form GM Uzbekistan in JV with UzAvtoSanoat. Again, at 266.7 million USD, the enterprise’s total capital paled in comparison to the industry’s multi-billion-USD average, yet it could benefit from a barrage of subsidies and exemptions as other ‘small’ manufacturing capitals in resource-rich Uzbekistan in order to stay in business and turn a profit (Galdini Citation2023). Crucially, the overvalued official exchange rate allowed GM to import obsolete machinery and equipment at subsidised prices to start production in the Uzbek market, while all inputs such as parts and components were exempted from import tariffs and excise taxes. So, for example, between 2007 and 2009 GM imported the J200 technological platform to Uzbekistan to start production of the Lacetti J200 in the country in 2008–9, that is, in parallel to the introduction on international markets of the new generation Lacetti J300 (Galdini Citation2023). As a consequence, as the GoU recently acknowledged, the industry’s ‘current range of car models are outdated [by an] average of 10–11 years’ and uncompetitive on the world market (PP-4087 Citation2019).

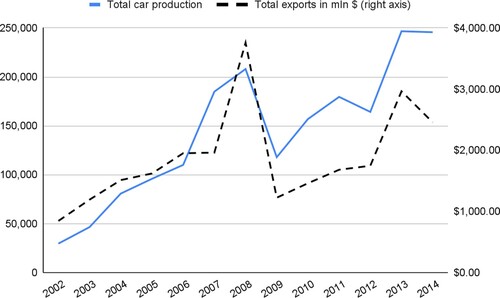

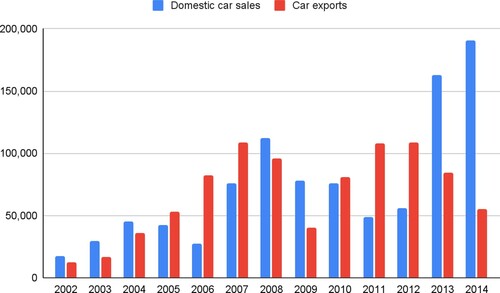

As such, it was the rise in the magnitude of ground-rent available in the Uzbek market that caused the appreciable growth in car production during the commodity supercycle (), rather than the creation of ‘a competitive export-oriented auto industry from the ground up’ (Popov and Chowdhury Citation2016, p. 5), as heterodox scholars would have it. In other words, this was a quantitative rise rather than a qualitative shift. Instead, the Uzbek car industry continued epitomising the ‘backward’ form of ground-rent-subsidised industrialisation in the country in JV with a leading MNC, which manufactures old models largely for the Uzbek domestic market. First, despite expanding, exports remained concentrated in Russia and, to a lesser degree, Kazakhstan, whose markets are also protected against the import of finished products (Barone and Bendini Citation2015) but with which Uzbekistan enjoys long-standing FTAs (UN ESCAP Citation2018). Second, even in the 2002–14 growth period, exports surpassed domestic sales only in a limited number of years and, even then, only in 2006, 2011, and 2012 significantly so. Put differently, most Uzbek-manufactured cars continued to be sold on the domestic market, rather than exported (). Third, and crucially, raw materials rather than finished industrial goods remained central to Uzbekistan’s export basket, still accounting for 77 per cent of the total in 2018 (Trushin Citation2019, p. 7).

Figure 1. Uzbekistan’s car industry production vis-à-vis total exports of cotton, gold, and natural gas in mln $ 2002–14 (source: own elaboration based on CER Citation2013, International Organization of Motor Vehicle Manufacturers data, and Atlas of Economic Complexity data).

Figure 2. Uzbekistan’s car industry: Domestic car sales vs car exports, 2002–14. Domestic car sales = total car production minus car exports (source: own elaboration based on CER Citation2013 and International Organization of Motor Vehicle Manufactures data).

In parallel to the rise in gold and natural gas production, Uzbekistan’s ongoing transformation was increasingly affecting cotton output in both absolute and relative terms. As explained, significant land hectarage was transferred from cotton to wheat to subsidise consumption for the general population which, in turn, contributed to lowering the cost of labour for capital. Moreover, the continuation of intensive cotton cultivation further depleted the relatively favourable natural conditions to grow the crop, as evident in the collapse in soil fertility including due to increasing salinisation (Muradov and Ilkhamov Citation2014, p. 45). Decollectivisation and the creation of private farms contributed to declining cotton yields by, inter alia, ‘delinking crop from livestock production. Cotton areas were left without organic manure from cattle, while wheat replaced fodder crops after harvesting cotton, [a Soviet management practice to restore soil nutrients,] leading to soil depletion and thereby cotton yield reduction’ (World Bank and IAMO Citation2019, p. 24). As a consequence, Uzbek cotton yields went from ‘exceeding U.S. yields by 74 percent during the first half of the 1970s’ (MacDonald Citation2012, p. 2) to lagging behind China’s by 1995 and the US’s by 2003–4 (Muradov and Ilkhamov Citation2014, p. 45). These radical changes led to total cotton production plunging by more than half between 1991 and 2018 (IndexMundi data), while the country’s share of total world cotton exports dropped from 10.7 per cent in 1990–91 to 3.9 per cent in 2014–15 (Ethridge Citation2016, p. 16). This explains why cotton declined from 57.3 per cent of the country’s total exports in 1996 to 2.14 per cent in 2018 (Observatory of Economic Complexity data).

With cotton ceding pride of place to gold and natural gas in Uzbekistan’s export basket, as well as due to the significant accumulation of international reserves in gold and hard currency on the back of the commodity supercycle, the conditions for the current liberalisation of the cotton sector and the currency regime under President Mirziyoyev were laid. First, by 2016, cotton rents had become so marginal to the country’s export balance sheet that the sector could be privatised with no significant consequences for the process of capital accumulation, as ground-rent has been increasingly accrued through the export of other commodities, particularly gold and natural gas. In this context, a series of presidential decrees and resolutions started liberalising the cotton sector, introducing vertically-integrated clusters with the participation of local and international investors to organise the production and processing of the crop (Trushin Citation2019). Second, with Uzbekistan enjoying a solid financial position in virtue of significant gold and hard currency reserves, amassed especially during the commodity supercycle, the multiple exchange rate system was eliminated in September 2017. However, the purchase of raw materials such as gold and natural gas at domestic cut-off prices to be sold at international prices abroad – a key form of ground-rent appropriation – has remained in place. In turn, a large share of this wealth keeps being funnelled in the form of credit to firms ‘through policy-based lending operations and shifting deposits to banks … on preferential terms’ by the CBU, NBU, and UFRD (IMF Citation2019). Equally, government monopolies and SOEs continue to provide cheap inputs and subsidised utilities to enterprises, with the latter including the general population and corresponding to 7.4 per cent of GDP, or 4.4 billion USD, in 2019 alone (IEA Citation2019).

Third, the number of Free Economic Zones (FEZs) has been expanded from three to 21, including turning the entire central region of Navoi into a FEZ, while creating 143 small industrial zones throughout the country, effectively generalising the various direct and indirect subsidies, preferences, and exemptions – all forms of ground-rent subsidisation – for any investor, national or international, willing to start a business in the country (Unified Portal of Free Economic Zones and Small Industrial Zones of the Republic of Uzbekistan website). Again, the introduction of these new enterprises and projects has been on the same domestically-oriented ‘backward’ basis since, according to the Ministry of Investments and Foreign Trade of the Republic of Uzbekistan, in 2020 total exports from all FEZs amounted to a mere 257,6 million USD (MIFT Citation2020). By comparison, gold exports for the same year accrued 6.52 billion USD (Observatory of Economic Complexity data). In turn, fourth, ‘backward’ manufacturing industries continue to absorb only a fraction of the active population, whose majority remains in the condition of relative surplus for the requirements of capital. As the World Bank (Citation2022, pp. 36, 97) recently put it, in Uzbekistan ‘most work is informal; and a large share of the working-age population is out of the labor force’, while millions continue engaging in seasonal migration to find work mostly in Russia and Kazakhstan. In 2021, their remittances amounted to 11.7 per cent of the country’s GDP (World Bank data).

Conclusion

In this paper, I explained the transformation of independent Uzbekistan starting from its integration into the global economy as a raw material exporter. In the past decades, while some parts of Asia including China underwent a meteoric process of industrialisation due to their relatively cheap and pliant (hence highly productive) labour forces, most countries of the Global South remained or, upon independence, became integrated into the International Division of Labour as producers of primary commodities for export in view of the relatively favourable natural conditions for this form of production within their territories. As the state mediated this process via specific policies that allocated ground-rent from the international sale of primary commodities to guarantee the continuous reproduction and expansion of capital accumulation, resource-rich countries were turned into the loci of rent-subsidised ‘backward’ industrialisation catering for the domestic market, as well as reservoirs of relative surplus populations.

As a cotton and, increasingly, gold and natural gas exporter, Uzbekistan’s development helps to illustrate empirically these enduring and interrelated dynamics of change in resource-rich countries in the past decades. The Uzbek model under President Karimov mediated the newly-independent country’s integration into the IDL as a cotton exporter via land decollectivisation, which, while uneven and protracted, consistently resulted in the mass expropriation of the rural population from the land through privatisation of access thereto (primitive accumulation). In parallel, multiple exchange rates, preferential credit, and subsidised inputs in/directly channelled cotton rents towards ‘backward’ ISI as in the car industry, with the overvalued national currency enabling the subsidised international procurement of parts and components for enterprises, as well as the import of obsolete machinery for domestic production by MNCs. Moreover, subsidised energy and wheat-based products contributed to lowering the cost of labour for ‘backward’ manufacturing firms.

Declining relative soil fertility (hence cotton yields) due to decades of cotton production, along with the commodity supercycle beginning at the turn of the millennium especially for energy and metals, laid the basis for the current ‘liberalisation’ of the cotton sector and the exchange rate regime under President Mirziyoyev. By now, gold and natural gas had substituted cotton as the main raw materials, whose sales accrued the rents necessary for the continuation of capital accumulation on the territory of Uzbekistan, while the physical gold and hard currency accumulated especially during the commodity supercycle enabled the elimination of the multiple exchange rate system. It is during this supercycle that car manufacturing experienced a significant uptick due to the increasing magnitude of ground-rent available in the Uzbek market to subsidise industrial production. Still, this was a quantitative rise rather than a qualitative shift, as the country remains integrated into the global economy as a producer of primary commodities for export, hence as a ‘backward’ industrialiser with a vast reservoir of RSP. As the latter could not be absorbed by the country’s ‘backward’ industries due to their limited (domestic) scale of production, it continues to struggle amid informal employment and mass migration to the cities and third countries.

These have been the enduring and interlinked features of transformation in independent Uzbekistan, which the orthodox and heterodox literature on transition mistake for the result of capitalism’s ‘underdevelopment’ in the country. Instead, the paper shows how the approach first developed by Iñigo Carrera starting from Marx’s critique of political economy provides key theoretical insights to account for the country’s transformation in view of its integration into the global economy as an exporter of primary commodities. As such, it is hoped that this analysis of the relatively understudied case of Uzbekistan can contribute to future research on similar dynamics of change in resource-rich countries of the Global South during the past decades.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Greig Charnock, Ilias Alami, Guido Starosta, and Gastón Caligaris for insightful comments on different drafts of this article. All the usual provisos apply.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Franco Galdini

Franco Galdini is an ESRC postdoctoral fellow in the Politics Department of The University of Manchester.

Notes

1 As will become clear in the rest of the paper, the qualifier ‘backward’ simply refers to the fact that, by world-market norms, industrial capitals in resource-rich countries are small in size and use obsolete technology to manufacture goods mostly for the domestic market. As such, the term comes in inverted commas.

2 While the various types of absolute and differential rents, as well as their different social origins, cannot be presented here due to space constraints, see Iñigo Carrera (Citation2017) for an in-depth discussion.

3 These processes translated into cycles of fierce resistance by peasant populations and repression by the state. This is beyond the scope of this article, but see, for example, Greco (Citation2022).

4 A detailed sectoral analysis of industrial development in the UzSSR is beyond the scope of this article, but see Ziyadullaev (Citation1984). The key point here is that, following independence, new industrial sectors such as car manufacturing were introduced in Uzbekistan, while, in parallel, the country experienced the mass informalisation of economic activity, including the rise of mass migration. These are the phenomena that, I argue, the orthodox and heterodox literature on transition mistake for deficiencies in an essentially national process of development.

5 While the state bought other raw materials such as gold and copper at a lower cut-off price for resale at international prices abroad, it was cotton that dominated the country’s export basket for approximately two decades after independence, accounting for at least a fifth of total export revenue up until the late 2000s (Observatory of Economic Complexity data).

6 Since independence, the GoU have enacted a series of agrarian reforms that attempted to increase productivity in small commercial farms, with mixed results. In general, farm sizes increased with each new round of reform with the aim of creating economies of scale, rising from an average of 15 ha in 1998–2006 to 40–60 ha in the 2008/9-2016 ‘consolidation’ period, and further expanding to 100 ha after that (World Bank and IAMO Citation2019). Still, these are small farms relative to the huge size of collectives in Soviet Uzbekistan, which averaged 1,777 ha per collective farm (1976 figure) (Khan and Ghai Citation1979, p. 97).

References

(All online sources last accessed on 23 August 2022)

- Anceschi, L., 2019. Regime-building through controlled opening: new authoritarianism in post-Karimov Uzbekistan. In: C. Frappi and F. Indeo, eds. Monitoring Central Asia and the Caspian area development policies, regional trends, and Italian interests. Venezia: edizioni Ca’ foscari, 107–119.

- Asian Development Bank (ADB). 2012. Adb to help develop Uzbekistan’s largest petrochemical plant [online]. Adb news release. Available from: https://www.adb.org/news/adb-help-develop-uzbekistans-largest-petrochemical-plant.

- Atlas of Economic Complexity (AEC) data. Available from: https://atlas.cid.harvard.edu/.

- Barone, B., and Bendini, R. 2015. Protectionism in the G20. study, policy department, European union’s directorate-general for external policies, DG EXPO/B/PolDep/Note/2015_136, Brussels: EU.

- Beeson, M., 2017. What does China’s rise mean for the developmental state paradigm? In: T. Carroll and D.S.L. Jarvis, eds. Asia after the developmental state: disembedding autonomy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 174–198.

- Blackmon, P., 2005. Back to the USSR: why the past does matter in explaining differences in the economic reform processes of Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan. Central Asian survey, 24 (4), 391–404.

- Blackmon, P., 2011. In The shadow of Russia: reform in Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan. Michigan: Michigan State University Press.

- Bonefeld, W., 2014. Critical theory and the critique of political economy: on subversion and negative reason. London and New York: Bloomsbury.

- Burnham, P., 1994. Open Marxism and vulgar international political economy. Review of international political economy, 1 (2), 221–231.

- Center for economic research (CER). 2004. The reorganization of cooperative agricultural enterprises (shirkats) into farming enterprises. Working Paper 2004/02. Tashkent: CER.

- Center for economic research (CER). 2013. Состояние и перспективы развития автомобильной промышленности Республики Узбекистан. Analytical Report no. 2013/08. Tashkent: CER. [State and prospects for the development of the automotive industry of the Republic of Uzbekistan].

- Central Bank of the Republic of Uzbekistan (CBU) data. Available from: https://cbu.uz/ru/.

- Chan, C.K., and Nadvi, K., 2014. Changing labour regulations and labour standards in China: retrospect and challenges. International labour review, 153 (4), 513–534.

- Charnock, G., and Starosta, G., 2016. Introduction: the new international division of labour and the critique of political economy today. In: G. Charnock and G. Starosta, eds. The New international division of labour: global transformation and uneven development. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1–22.

- Connell, R., and Dados, N., 2014. Where in the world does neoliberalism come from? Theory and society, 43 (2), 117–138.

- Connolly, M., 1997. Uzbekistan. In: P. Desai, ed. Going global: transition from plan to market in the world economy. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 385–412.

- Conti, J., et al., 2016. International energy outlook 2016 with projections to 2040. United States energy information administration report DOE/EIA-0484(2016). Washington, D.C.: US EIA.

- Cornia, G.A., 2003. An overall strategy for pro-poor growth. In: G. A. Cornia, ed. Growth and poverty reduction in Uzbekistan in the next decade. Tashkent: UNDP, 91–115.

- Craumer, P.R., 1992. Agricultural change, labor supply, and rural out-migration in soviet Central Asia. In: R.A. Lewis, ed. Geographic perspectives on soviet Central Asia. London and New York: Routledge, 129–176.

- Davis, M., 2006. Planet of slums. London: Verso.

- Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU). 1997. Uzbekistan: country report, 1st quarter 1997. London: EIU.

- Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU). 1998. Uzbekistan: country report, 3rd quarter 1998. London: EIU.

- Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU). 2001. Uzbekistan: country report, July 2001. London: EIU.

- Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU). 2002. Uzbekistan: country report, December 2002. London: EIU.

- Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU). 2008. Uzbekistan: country profile 2008. London: EIU.

- Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU). 2013. Uzbekistan: country report, 3rd quarter 2013. London: EIU.

- Ethridge, D. 2016. Policy-driven causes for cotton’s decreasing market share of fibres. 33rd international cotton conference, 16-18 March 2016 Bremen.

- Federici, S., 2012. Revolution at point zero: housework, reproduction, and feminist struggle. Brooklyn, NY: Autonomedia.

- Fine, B., 2013. Beyond the developmental state: An introduction. In: B. Fine, J. Saraswati, and D. Tavasci, eds. Beyond the developmental state: industrial policy into the twenty-first century. London: Pluto Press, 1–32.

- Galdini, F., 2023. Backward” industrialisation in resource-rich countries: the car industry in Uzbekistan. Competition & Change, 27 (3-4), 615–634.

- Global Knowledge Partnership on Migration and Development (KNOMAD) and World Bank, 2019. Migration and remittances: recent developments and outlook. In: Migration and development brief n. 31. Washington, D.C.: World Bank.

- Gore, C., 1996. Methodological nationalism and the misunderstanding of east Asian industrialisation. The European journal of development research, 8 (1), 77–122.

- Greco, E., 2022. Engaging with the non-human turn: a response to Büscher. Dialogues in human geography, 12 (1), 90–94.

- Grinberg, N., 2013. The political economy of Brazilian (Latin American) and Korean (east Asian) comparative development: moving beyond nation-centred approaches. New political economy, 18 (2), 171–197.

- Grinberg, N., 2016. From the financial crisis to the next eleven: limits and contradictions in the Korean process of capital accumulation. Journal of the Asia pacific economy, 21 (1), 1–25.

- Grinberg, N., and Starosta, G., 2009. The limits of studies in comparative development of east Asia and Latin America: the case of land reform and agrarian policies. Third world quarterly, 30 (4), 761–777.

- Hoen, H.W., and Irnazarov, F., 2012. Market reform and institutional change in Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan: paradoxes and prospects. In: J. Ahrens and H.W. Hoen, eds. Institutional reform in Central Asia: politico-economic challenges. London and New York: Routledge, 21–42.

- Ilkhamov, A., 2004. The limits of centralization: regional challenges in Uzbekistan. In: P. Jones Luong, ed. The transformation of central: states and societies from soviet rule to independence. New York: Cornell University Press, 159–181.

- IndexMundi data. Available from: https://www.indexmundi.com.

- Iñigo Carrera, J. 2013. El capital: Razón histórica, sujeto revolucionario y conciencia. 2nd ed. Buenos Aires: imago mundi. [Capital: Historical Reason, Revolutionary Subject and Consciousness]

- Iñigo Carrera, J., 2016. The general rate of profit and its realisation in the differentiation of industrial capitals. In: G. Charnock and G. Starosta, eds. The new international division of labour: global transformation and uneven development. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 25–54.

- Iñigo Carrera, J., 2017. La renta de la tierra: formas, fuentes y apropiación [Land Rent: Forms, Sources and Appropriation]. 1st ed. Buenos Aires: Imago Mundi.

- International Crisis Group (ICG). 2005. The Curse of Cotton: Central Asia’s Destructive Monoculture. Icg Asia report n. 93. Brussels: ICG.

- International Energy Agency (IEA). 2019. Value of fossil-fuel subsidies by fuel in the top 25 countries. Available from: https://www.iea.org/data-and-statistics/charts/value-of-fossil-fuel-subsidies-by-fuel-in-the-top-25-countries-2019.

- International labour organisation (ILO), 2018. Women and men in the informal economy: a statistical picture. 3rd ed. Geneva: ILO.

- International Monetary Fund (IMF). 1998. Republic of Uzbekistan: recent economic developments. Imf staff country report n. 98/116. Washington, D.C.: IMF.

- International Monetary Fund (IMF). 2008. Republic of Uzbekistan: poverty reduction strategy paper. Imf country report n. 08/34. Washington, D.C.: IMF.

- International monetary fund (IMF). 2019. Uzbekistan: staff concluding statement of the 2019 article IV mission, consultations under article IV of the IMF’s articles of agreement. Washington, D.C.: IMF.

- International Organization of Motor Vehicle Manufacturers (OICA) data. Available from: https://www.oica.net/.

- Jeong, S., 2004. Crisis and restructuring in east Asia: the case of the Korean chaebol and the automotive industry. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Jepson, N., 2020. In China’s wake: how the commodity boom transformed development strategies in the global south. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Kandiyoti, D., 2003. The cry for land: agrarian reform, gender and land rights in Uzbekistan. Journal of agrarian change, 3 (1-2), 225–256.

- Khan, A.R., 2007. The land system, agriculture and poverty in Uzbekistan. In: A.H. Akram-Lodhi, S.M. Borras Jr, and C. Kay, eds. Land, poverty and livelihoods in an Era of globalization: perspectives from developing and transition countries. London and New York: Routledge, 221–253.

- Khan, A.R., and Ghai, D., 1979. Collective agriculture & rural development in soviet Central Asia. London and Basingstoke: The Macmillan Press LTD.

- Lebdioui, A., 2022. The political economy of moving up in global value chains: how Malaysia added value to its natural resources through industrial policy. Review of international political economy, 29 (3), 870–903.

- Lombardozzi, L., 2019. Can distortions in agriculture support structural transformation? The case of Uzbekistan. Post-Communist economies, 31 (1), 52–74.

- Lombardozzi, L., 2021. Unpacking state-led upgrading: empirical evidence from Uzbek horticulture value chain governance. Review of international political economy, 28 (4), 947–973.

- MacDonald, S. 2012. Economic policy and cotton in Uzbekistan. A report from the economic research service, CWS-12h-01. Washington, D.C.: United States Department of Agriculture.

- Maksakova, L.P., 2008. Internal migration in Uzbekistan: sociological aspects. In: E.V. Abdullaev, ed. Labour migration in the republic of Uzbekistan: social, legal and gender aspects. Tashkent: UNDP and Gender Programme of the Swiss Embassy, 40–129.

- Marx, K., 1867/1976. Capital: A critique of political economy. London and New York: Penguin Books in association with New left review

- Ministry for foreign economic relations investments and trade of the republic of Uzbekistan (ministry of trade) And united nations development program (UNDP). n.d. invest in Uzbekistan. Tashkent: UNDP.

- Ministry of Investments and Foreign Trade of the Republic of Uzbekistan (MIFT). 2020. Free Economic Zones of Uzbekistan: results for 2020 and Development Prospects for 2021. Available from: https://mift.uz/ru/menu/svobodnye-ekonomicheskie-zony-uzbekistana-itogi-2020-goda-i-perspektivy-razvitija-na-2021-god.

- Mirkasimov, B., and Parpiev, Z., 2017. The political economy of wheat pricing in Uzbekistan, 69–82. Moscow: Eurasian Center for Food Security.

- Moyo, D., 2012. Winner take all: China’s race for resources and what It means for the world. New York: Basic Books.

- Muradov, B., and Ilkhamov, A., 2014. Uzbekistan’s cotton sector: financial flows and distribution of resources. Working paper, Open society Eurasia program. New York: Open Society Foundations.

- Nicita, A., and Razo, C. 2021. China: the rise of a trade titan. United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) News. Available from: https://unctad.org/news/china-rise-trade-titan.

- Observatory of Economic Complexity (OEC) data. Available from: https://oec.world.

- Organisation for economic Co-operation and development (OECD), 2017. Boosting SME internationalisation in Uzbekistan through better export promotion policies. Oecd Eurasia competitiveness programme. Paris: OECD.

- Organisation for economic Co-operation and development (OECD), 2019. The global material resources outlook to 2060: economic drivers and environmental consequences. Paris: OECD.

- Penati, B., 2013. The cotton boom and the land Tax in Russian Turkestan (1880s-1915). Kritika: explorations in Russian and eurasian history, 14 (4), 741–74.

- Pirani, S. 2012. Central Asian and Caspian Gas Production and the Constraints on Export. The Oxford Institute for Energy Studies (OIES) Paper NG69.

- Pomfret, R., 2002. State-Directed diffusion of technology: the mechanization of cotton harvesting in soviet Central Asia. The journal of economic history, 62 (1), 170–188.

- Pomfret, R., 2019. The central Asian economies in the twenty-first century: paving a New silk road. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

- Popov, V. 2013. Economic miracle of post-soviet space: why Uzbekistan managed to achieve what no other post-soviet state achieved. Munich personal RePEc archive (MPRA) paper n. 48723.

- Popov, V., and Chowdhury, A. 2016. What can Uzbekistan tell US about industrial policy that we did not already know? Un department of economic and social affairs (DESA) working paper n. 147 ST/ESA/2016/DWP/147.

- Pradella, L., 2014. New developmentalism and the origins of methodological nationalism. Competition & change, 18 (2), 180–93.

- President of Uzbekistan (PP-4087). 2019. Концепция развития автомобильной промышленности Республики Узбекистан до 2025 года. Resolution no. 4087. Available from: https://regulation.gov.uz/ru/document/4087. [Concept for the development of the automotive industry of the republic of Uzbekistan until 2025].

- Rodrik, D., 2009. Industrial policy: don’t Ask Why, Ask How. Middle East development journal, 1 (1), 1–29.

- Rustemova, A. 2012. Understanding authoritarian liberal regimes: governing rationales, industrialization patterns and resistance. thesis (PhD). Rutgers Graduate School-Newark, The State University of New Jersey.

- Safirova, E., 2015. The mineral industry of Uzbekistan. In: United States geological survey 2015 minerals yearbook, 50.1–50.8. Washington, D.C.: USGS.

- Secretariat of the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD), 2017. Global land outlook. 1st ed. Bonn: UNCCD.

- Shaismatov, F. 2018. Uzbekistan’s energy sector: opportunities for international cooperation. Presentation at the workshop on energy investments in Uzbekistan organised by the knowledge centre of the energy charter secretariat, 4 October 2018 Brussels.

- Singh, J.N., and Ovadia, J.S., 2018. The theory and practice of building developmental states in the global south. Third world quarterly, 39 (6), 1033–1055.

- Spechler, M.C., 2010. Uzbekistan: a successful authoritarian economy. Orient, 54 (4), 44–51.

- Spoor, M., 2005, November 3–4. Cotton in Central Asia: “curse” or “foundation for development”? In: D. Kandiyoti, ed. The cotton sector in Central Asia economic policy and development challenges. London: SOAS, 54–74.

- Tarr, D., and Trushin, E., 2004. Did the desire for cotton self-sufficiency lead to the Aral Sea environmental disaster? A case study on trade and the environment. Washington, D.C.: World Bank.

- Trevisani, T., 2010. Land and power in Khorezm. Farmers, communities and the state in Uzbekistan’s decollectivisation. Berlin: LIT Verlag.

- Trushin, E., 2018. Uzbekistan growth and job creation: an in-depth diagnostic. Washington, D.C.: World Bank.

- Trushin, E., 2019. Uzbekistan: Toward a new economy. Country Economic Update Summer 2019. Washington, D.C.: World Bank.

- Tsereteli, M., 2018. The economic modernization of Uzbekistan. In: F. Starr and S. E. Cornell, eds. Uzbekistan's New Face. London: Rowman & Littlefield, 82–114.

- Unified Portal of Free Economic Zones and Small Industrial Zones of the Republic of Uzbekistan (SEZ) website. Available from: https://sez.gov.uz/ru.

- United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). 1999. Investment policy review of Uzbekistan. UNCTAD/ITE/IIP/MISC.13. New York and Geneva: UNCTAD.

- United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). 2019. State of commodity dependence. UNCTAD/DITC/COM/2019/1. Geneva: UNCTAD.

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). 2018. Устойчивая занятость в Узбекистане: состояние, проблемы и пути их решения. Tashkent: UNDP. [Sustainable employment in Uzbekistan: current state, problems and solutions].