ABSTRACT

This paper investigates the growth of new forms of personal finance used in purchasing motor vehicles – a development which it characterises as ‘financialisation’. It focusses on the case of the rise of the personal contract purchase (PCP) in the United Kingdom market, and seeks to account for its growing popularity, and potential implications. It is found that the rise of PCPs is best understood as a form of financial innovation designed to help car manufacturers overcome long-term profit realisation problems produced by market saturation in mature markets. The way PCPs are structured lowers consumers’ monthly finance payments, allowing them to access to higher value vehicles, and encourages more frequent purchases of new vehicles, all of which allows greater manufacturer profit realisation. However, it does so in a way which increases financial risk, to consumers, car manufacturers, and financial investors. On the other hand, manufacturers’ risk exposure is limited by how the consumers’ car dependency lowers expected default rates. PCPs threaten financial stability, as well as sustaining social and environmentally unsustainable consumption practices.

Introduction

This article considers the material culture of financialisation in relation to the consumption of private motor vehicles. There has been significant innovation in the methods by which finance is provided to car consumers, which has increased the extent and scope of private finance in consumption, a characteristic which I identify as ‘financialisation’. At the forefront of innovation has been the ‘personal contract purchase’ (PCP), which has become a very popular form of car consumer finance in many parts of the world.Footnote1 This article asks what accounts for the rise of PCPs, and what the implications for the cultures of car consumption could be.

The way PCPs are structured means that few consumers keep hold of the car that the agreement is attached to. Instead, they tend to take advantage of the fact that the financing mechanism allows them to return the vehicle, and take out a new PCP deal for a new car, without financial loss. As will be shown, this has resulted in the acceleration of the rate at which new cars are consumed.

Common accounts for the rise of PCPs associate their increasing popularity with overall trends in consumption habits, especially a throwaway culture and desire for the new. In contrast, this article argues that understanding the causes and effects of the rise of PCP requires appreciating changing dynamics between production, retail and consumption as ‘system of provision’ specific to cars. It does so by interrogating the limited car industry financial data publicly available, alongside credit ratings agency reports, company accounts, and reports in the trade press.

This article focusses on the United Kingdom (UK) market, because it has been at the forefront of the rise of PCPs internationally. It shows that PCPs have arisen primarily as a response to long-running economic contradictions inherent in car manufacturing, which necessitate the maintenance of a certain level of production amid flatlining demand for new vehicles in ‘mature markets’ such as the UK. By allowing manufacturers to extend greater quantities of credit to consumers, PCPs help car manufacturers maintain and increase the pool of high spending consumers. This helps them overcome the limitations created by their core business model, albeit in ways that increase financial risks for the industry and consumers, as well as to wider society.

This article is novel in that it takes consumer car finance as an object of investigation in political economy. The paper will briefly situate the rise of PCPs in the history of consumer car finance, before discussing PCPs’ imbrication into international financial systems. The main body of the paper is reserved for a discussion on the material cultures the financialisation of car consumption gives rise to, connecting the agencies of consumers, producers and retailers in the system of provision.

Background

‘Mass motoring’ has long been considered problematic for several reasons. Firstly, motorisation requires a large scale built infrastructure which precludes the use of land for other purposes, not least the space required for other, more sustainable, forms of transport. Increased demand for car use necessitated the expansion of road capacity for motor vehicles, which helped create more demand for car use, and so on (Hymel et al. Citation2010). The deleterious social impacts of ever greater car use is widely recognised, including on the safety of other road users, noise and air pollution, carbon emissions and community severance, and the disproportionate effects of these problems on the poorest (Jeekel Citation2016, Mattioli Citation2021).

Despite these downsides, a culture of ‘car dependency’ dominates, which rests on the convenience of driving relative to alternatives. It shapes not only individual consumer travel choices but also government policymaking, which tends to prioritise investment in car-based infrastructure over alternative transport modes, and which subsidises production and consumption in various ways (Mattioli et al. Citation2020). Encouraging mass motoring has been central to elites’ construction of what Gramsci (Citation1985) termed ‘political and cultural hegemony’ (p. 258). As Fraser (Citation2022) notes, cars are an ‘icon of consumerist freedom’ (p. 100) – more than just a means of transport, but also an aspirational form of conspicuous consumption which continually reproduces the social competition capitalism rests upon. Political support for motorisation is strong, and forms a barrier to both reducing car dependency and enabling wider progressive change.

The UK, like other nations with wealthier populations, has a particularly high degree of ‘motorisation’.Footnote2 There are 33.2 million cars in the UK and 78 per cent of households have access to one, and they are by far the most popular form of passenger transport, accounting for 87 per cent of journeys.Footnote3 Almost all cars are purchased through the use of consumer finance,Footnote4 and car finance is the third highest sector of consumer borrowing,Footnote5 representing around £40 billion a year in new credit advanced.Footnote6

Despite the importance of car finance to the economy, and in stark contrast with a vast proliferation of studies of financialisation in other key areas of personal consumption,Footnote7 academic studies of developments in car consumer finance are extremely rare. As this paper will argue, the financialisation of car consumption creates new financial risks for consumers, car manufacturers and their financial backers, and the economy at large, and threatens efforts to transition to a more ecologically sustainable transport system, suggesting that a much greater appreciation of the implications of it is required.

Financialisation in practice

Space does not allow for an historical overview of the development of car consumer finance, except to briefly indicate that the lending of money to consumers to finance car consumption is not new, and was crucial to the development of the car industry, because few consumers have the available cash to buy vehicles outright. For example, General Motors in the United States created a separate consumer finance arm as early as 1919 (Calder Citation1999, p. 192).

The great post-war boom in car ownership was principally financed by ‘hire purchase’ (HP) arrangements, in the UK as elsewhere. HP involves consumers repaying the balance of the sales price plus interest over a set period, attaining full ownership at the end of the contract.

A new form of consumer car finance came to prominence in the late 2000s – the PCP.Footnote8 PCPs differ from HPs in important ways. Rather than repaying the entirety of the original purchase price of the vehicle over the course of the contract, consumers repay only a proportion. At the end of the contract, which, like HP contracts tends to be around three to four years, instead of owning the vehicle outright, consumers are confronted with an ‘optional lump sum’, which represents the unpaid balance of the finance deal. The sum is based on an estimation of what the residual (or ‘used’) value of the vehicle will be at the end of the contract term, which is guaranteed by the financing party and is known as the ‘guaranteed minimum future value’. This is typically a very significant amount, often between a third and a half of the sales price.Footnote9 The consumer can then choose to attain ownership of the car by paying the optional lump sum, returning the car to the retailer, or entering into a new PCP deal for another car. Attaining ownership by paying the lump sum is very unlikely, thanks to the high cost. PCPs are thus structured to incentivise consumers to swap their vehicle for a new one at contract termination – something much less likely to happen at the termination of HP contracts, which end with no further payments needed to retain the vehicle.

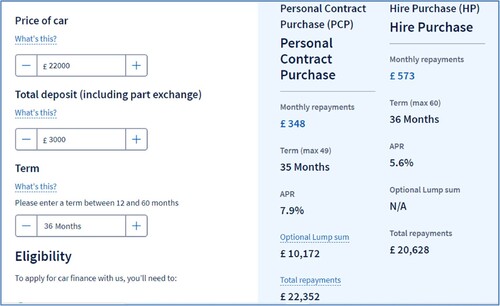

PCPs have taken over from HPs as by far the most popular form of consumer car finance in the UK, despite the continuing widespread availability of the latter. The optional lump sum mechanism creates an increase in the illusion of affordability relative to HP financing. This is best demonstrated by way of an example, comparing an HP with a PCP quote for a £22, 000 car, financed for around 3 years. As can be seen in , below, to finance the same vehicle over a similar length of time, consumers are asked to make monthly payments of only £348 in a PCP deal, compared to £573 under HP – a saving of 39 per cent a month. That is because, in the case of PCPs, much of the value of the vehicle is tied-up in the optional lump sum – in this case £10, 172. It is that difference in monthly cost that allows consumers to access higher value vehicles than was previously the case. For those on lower incomes, that can mean being able to access new vehicles for the first time.

Figure 1. Illustrative comparison between PCP and HP financing.Footnote10

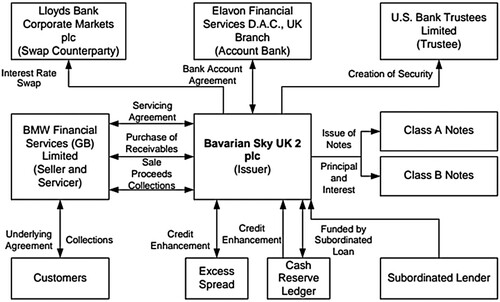

There is little public information regarding how PCPs interact with the wider financial system. A partial exception to this is a limited amount of data published by credit rating agencies, often hidden behind paywalls. One such example is the reports published by the Fitch agency on BMW’s PCP offerings, represented in , below. These can be used to indicate the typical structure of PCPs and how they connect consumer payments into international financial markets.

Figure 2. Transaction and legal structure of Bavarian Sky UK 2.Footnote11

BMW Financial Services is a subsidiary of the BMW AG group – the manufacturers. It arranges PCP deals with consumers, through franchised dealerships. It does so on behalf of Bavarian Sky UK 2 plc, a ‘special purpose company incorporated for the securitisation of a portfolio of auto loans’.Footnote12 The structure is designed to transform PCP ‘receivables’ – the monthly payments PCP consumers make to maintain access to their car – into ‘asset-backed securities’. These securities are in the form of ‘notes’, which investors can purchase and which generate an expected rate of return over and above the purchase price over a set period. Such securities are valuable collateral for financial investors, creating a reliable income stream to bolster the credit worthiness of financial institutions. These securities are traded and blended in international financial markets (Lessambo Citation2021). PCP securitisation typically divides receivables into batches, with lending to consumers deemed to be at less risk of default pooled into Note A offerings, and those deemed more at risk into Note Bs.Footnote13

Although Bavarian Sky UK 2’s parent company Bavarian Sky UK Holdings was created for the sole purpose of securitising BMW AG’s PCP receivables, it is not owned by BMW AG, by instead by Wilmington Trust Sp Services (London) Limited (WTSS) – a company that specialises in hosting ‘special purpose vehicles’ for securitisation purposes. As company accounts state, BMW has ‘no direct ownership interest’ in WTSS’.Footnote14 As a credit report makes clear, this arrangement allows Bavarian Sky UK 2 plc to be legally constituted as ‘bankruptcy-remote company with limited liability under the laws of England and Wales’ (Fitch Citation2018, p. 3). The ownership structure allows BMW AG to isolate financial risks associated with PCP lending to some degree, allowing it to take a higher risk approach to lending to consumers, while limiting the impact on the group’s overall credit profile.

also makes clear the imbrication of the international banking system in the securitisation of PCPs. For example, US Bank Trustees assists with the security creation process, and Elavon Financial Services DAC provides a bank account agreement. Both companies are ultimately owned by US Bank (US Bancorp). In addition, Lloyds Bank subsidiary Llodys Bank Corporate Markets plc provides interest rate swap facilities.

The rise of PCPs is a significant development the in financing of car consumption. Qualitatively, it represents a new form of financial engineering, which allows car manufacturers to tap into an appetite in international financial markets for asset-backed securities to create new forms of consumer car finance, while protecting their own credit worthiness. Quantitatively, as will be explored in greater detail in the remainder of this paper, it has considerably grown the amount of debt held by consumers. In short, the rise of PCPs represents a considerable financialisaton of car consumption.Footnote15

Material cultures of car consumption financialisation

There has been limited discussion on how PCPs relate to the cultures of car consumption. However, it is apparent to many observers that the rise of PCPs has been associated with new car consumption practices, especially a tendency for consumers to replace their current car with a new model at a faster rate than was the case with previous forms of finance such as HPs (Masson Citation2019, Windridge Citation2020, Bryant Citation2023, Cottle Citation2023).

This commentary tends to view the rise of PCPs as demand-led, often referring to changed cultural norms surrounding consumption practices of consumer durables in general. A popular referent, across a range of accounts in the trade and popular press, is mobile phone finance contracts, which are associated with a tendency for frequent replacement of devices by consumers.Footnote16 Louise Wallis from the Retail Motor Industry Federation epitomises this view: ‘Everybody’s got used to paying a monthly payment for a mobile phone. At two years you get an upgrade … The same psyche is beginning to happen with cars. It’s just on a bigger scale’ (cited in Milligan Citation2017).

Frequent comparisons to mobile phone consumption practices suggest a widespread assumption that changing patterns of provision in consumer car finance are a logical market response to changing consumer preferences, derived from broader cultural shifts related to consumption. Fine and Bayliss (Citation2021) criticise such ‘horizontal’ framings of the culture of consumption, because they do not adequately take into account the specificities of the relationship between consumption and production unique to each commodity. By contrast, they advocate the adoption of a ‘vertical’ analysis framework known as ‘systems of provision’ (SoP, hereafter). This is based on the idea that consumption needs to be ‘understood more closely in relation to its attachment to production’ and to be placed ‘on the broader terrain of provisioning, where it belongs’ (Fine et al. Citation2018, p. 29, p. 39).

This raises questions of scope. As Bayliss and Fine (Citation2020) – the originators of the approach – recognise, ‘SoP analyses require taking into account an extensive range of factors [and] not every element of each component in the chain of provisioning … can be thoroughly investigated’ (p. 42). While there are many potentially important developments in car consumption financing, this article limits itself to the PCP phenomenon in the new car market. Firstly, while the used market is around 4.5 times the size of the new car market (Statista Citation2022), it is in the new car market where PCPs have arisen first and with greatest broader impacts (although, as we shall see, new PCPs’ financial value rest on the stability of the used market). Secondly, while other new forms of finance are emerging, none are on the scale of PCP for personal purchases.Footnote17 Finally, around half of all new vehicles purchased are ‘company cars’, these are subject to different financing mechanisms to PCPs, and are therefore outside this article’s scope.Footnote18

Adopting the SoP approach leads me to frame changing patterns of car finance in relation to the dynamics of car production. In doing so, I will make selective use of the ‘10Cs’ framework (following Bayliss Citation2017), which characterises the core features of the material cultures surrounding the financialisaton of consumption as: Constructed, Construed, Conforming, Commodified, Contextual, Contradictory, Closed, Contested, Collective and Chaotic.

Car manufacturers

Car production rests on large economies of scale. The development of the mass production of cars, pioneered in the 1920s, was underpinned by the advent of the all-steel ‘unibody’. The unibody greatly streamlined production, requiring high levels of capital investment in high volume plants, which created high barriers to market entry and exit. Manufacturers became forced to recoup expensive investments in plants and machinery over long timescales. Large economies of scale and capital intensity means that plants must maintain high levels of production in order for manufacturers to recoup productions costs, ‘at about 85 percent capacity utilization’ (Wells Citation2010, p. 146).

Intense competition incentivised manufacturers to reduce production costs (Nieuwenhuis Citation2015). This was achieved by adopting ‘lean production’, which focusses on increasing productivity by creating efficiencies in the utilisation of labour (Smith Citation2000).

Improvements in productivity have not provoked an overall decline in employment levels (Baily et al. Citation2005), but instead to ever increasing output by manufacturers. This has created significant overcapacity in the global car market, which cannot match vicissitudes in demand without writing-off large quantities of fixed capital investment. Overcapacity in production has made profit realisation increasingly difficult. Despite the sectoral increase in productivity that has arisen as a result of lean working, overall profit margins have steadily declined, decreasing from around 20-30 per cent in the 1920s to somewhere between 3.5 per cent and 5 per cent by the 2010s (Niewenhuis and Wells Citation2003), pp. 101–11, Wells Citation2010, p. 126, Martinuzz et al. Citation2011, p. 8).

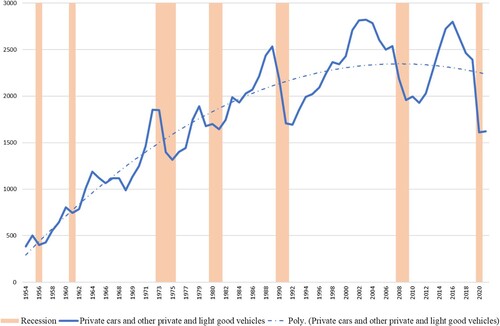

While, to significant extent, increased supply of vehicles has been met by increased demand in emerging economies, demand has tended to dampen in the ‘mature’, wealthier markets of the Global North (Martinuzzi et al. Citation2011, Wells Citation2015, pp. 20-1). This has created a situation of ‘market saturation’. As Metz (Citation2013) observed, by 2012 car and van ownership had stabilised at around 75 per cent of households in the UK, and by that point, the market was overwhelmingly to provide replacement vehicles, as opposed to serving consumers who did not previously have access to a car. This tallies with new car registration data.Footnote19 As can be seen in , below, the number of new cars registered every year is sensitive to the health of the overall economy, but extracting from that indicates a long-term trend of stagnation of annual registration rates from the early 2000s.

Figure 3. Private cars and other private and light goods vehicles registrations per year in Britain (thousands).Footnote20

Market saturation has led to manufacturers seeking to entice consumption with a proliferation of models, body styles and variants (Wells Citation2010, Citation2013). This required investment in design and a reorganisation of production. To mitigate the loss of economies of scale that product differentiation would otherwise entail, manufacturers have concentrated on producing a small number of multipurpose ‘platforms’, which consist of the core technological components, such as the floorplan (the foundation of the chassis), axles, steering, and the power chain components (Mattioli et al. Citation2020). Product differentiation allowed manufacturers to increase the sales prices of new cars. One survey found that in the decade leading up to 2021, average new car prices in the UK had increased from £27, 675 to £38, 585 – a 15 per cent increase in real terms. Another reported a 17 per cent real terms increase between 2008 and 2018.Footnote21 In other words, manufacturers were able to compensate for flatlining sales by increasing prices.

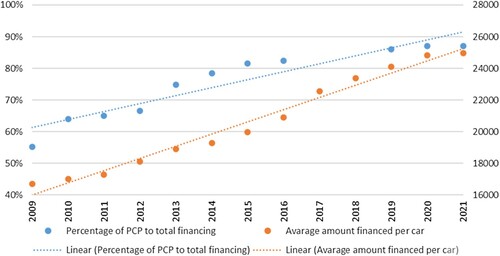

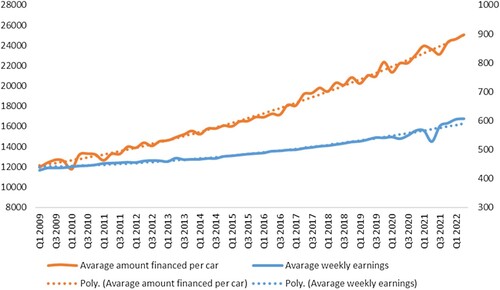

This article argues that increasing sales prices has is inextricably linked to the rise in PCPs, because PCPs allow consumers access to greater amounts of credit with which to finance more expensive vehicle purchases. , below, shows the relationship between the increased prevalence of PCPs as a method of financing new car purchases, and the average value of new car finance deals. As can be seen, between 2009 and 2021, the proportion of PCP deals to total consumer car financing for new cars increased from 55 per cent of the market to 87 per cent. In the same period, the average amount financed per new car rose from £16692 to £24978 (at constant 2022 prices).

Figure 4. Proportion of PCP to total consumer financing (PCP + HP) for new car sales (left axis) and average amount financed per new car (£, inflation adjusted) (right axis).Footnote22

Furthermore, the rise in PCPs has been associated with a boom in consumer car finance, as , below, illustrates. Between 2008 and 2019, despite flat new vehicle registration volumes, total new car consumer finance transacted per annum increased an extraordinary 153 per cent, from £8.5 billion in 2008 to £21.5 billion in 2019 (at constant 2022 prices), only losing some ground during the Covid crisis.

Figure 5. Total new car finance (£millions, inflation adjusted).Footnote23

Car manufacturers have significantly expanded credit to consumers via PCPs in order to maintain new car sales at historic levels and increase unit sales prices. Considering this puts a new spin on accounts of the financialisation of the car manufacturing industry itself, which are based on the observable fact that car manufacturers are increasingly reliant on profits made by their financing arms, in contrast to a lack of profitability arising from manufacturing.Footnote24 But, as we have seen, PCPs have been rolled-out in order to sustain the profitability of production. The location where profit shows up in the accounts of the manufacturing group’s corporate subsidiaries is largely immaterial. As the next section will discuss, the rollout of PCPs to sustain manufacturers’ profitability rests crucially on the agency of dealerships.

Car dealerships

93 per cent of new car sales in the UK are transacted through ‘franchised’ dealerships – dealerships that have an exclusive trading relationship with manufacturers, but whose ownership is independent of them (National Franchised Dealers Association Citation2019). Franchised dealerships negotiate the retail price of the vehicle, alongside the specifications of the PCP agreement that comes with it, with each consumer. While, in theory, consumers can shop around for car finance, the vast majority use PCP packages provided by the car’s manufacturer, as promoted by the franchised dealership (Apex Insight Citation2017, p. 4, Masson Citation2023).

The Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) has investigated suspicions of unfair financial brokering practices by dealerships, in which PCPs have been at the centre of attention (FCA Citation2019, Citation2020). The FCA was not satisfied that dealerships have been performing adequate credit checks on consumers, and found that dealerships had not properly informed consumers about the financial risks PCPs entail. As the FCA (Citation2019) states, dealerships ‘must not emphasise any potential benefits of a product without also giving a fair and prominent indication of any relevant risks’ (p. 13). The lack of sufficient disclosure of consumer risk is particularly problematic when considering the problem of ‘negative equity’, described in the next section.

The FCA investigation mainly focused on the practice by dealerships offering their brokers (car salespeople) interest rate commission. Dealerships can add interest to finance deals and keep a proportion of the spread between the rate manufacturers lend and the rate the consumer pays. Consumers have little knowledge that they are paying this extra commission, which is unfair because such knowledge could impact on consumer choice, including whether to use non-manufacturer provided finance options.Footnote25 The FCA were also concerned that interest rate commission was unfairly financially disadvantaging the manufacturers by siphoning off their potential income. These investigations led to it banning interest rate commission incentives (FCA Citation2020).

While the FCA’s commission concerns may be valid, they eschew an essential point that emerges in light of the analysis so far presented in this paper: commission is used to incentivise the extension of greater amounts of credit to sell more valuable cars, and is therefore beneficial for manufacturers as well as dealers. Indeed, the fact that franchised dealerships are reliant on manufacturers for supplying both stock and finance limits the potential for dealerships to take an unfair cut of profits.Footnote26 Brokers skillfully combine car and financial expertise, using the physical space of the showroom – with display models, test drives and financial terminals in close proximity – to conduct a sales pitch which promotes high levels of borrowing to finance the consumption of more expensive vehicles. They are therefore essential agents in the financialisation of car consumption that vehicle manufacturing is reliant upon.

The drive to extend consumer borrowing also frames a recent spike in mis-selling complaints related to PCP transactions received by the Financial Ombudsman Service. Such has been the scale of complaints received (11, 452 in the 2022/23 financial year alone), there is burgeoning market of legal firms offering to complete the complaint paperwork for consumers in return for a cut of the compensation. Compensations levels are estimated at around £1, 500 per consumer, on average. This has drawn comparisons with the payment protection insurance mis-selling scandal, which has threatened to topple high street banks (Nixon Citation2023).Footnote27

Dealerships perform a necessary retailing service on behalf of manufacturers. Their role is one of synchronisation between the supply of stock, the demand from consumers, and the finance package that enables sales, the better to extend consumer debt, and manufacturer profit, as much as possible. Additionally, and as the next section will demonstrate, of vital importance to the financialisation of car consumption is the after sales management of the risk of consumer default by dealerships.

Credit ratings agencies

Already implicit in the above analysis, PCP lending practices are fraught with the ‘risk’ that consumers default on monthly repayments. Great importance is placed by financial markets on credit ratings agencies’ views on the risk of such default. Their reports are used to inform investment decisions by potential buyers of PCP securities. Much of the financial value of PCP receivables lies in their ability to provide a steady income stream to the asset holder. As with other forms of consumer credit asset-backed securities, it is the regularity and reliability of that stream that maximises its value, because it allows the asset backed security to be more easily sliced up, repackaged and sold on (Leyshon and Thrift Citation2007).

Consumers’ ability to maintain loan repayments is explicitly tied to the overall state of the economy, as measured in projected gross domestic product growth, in ratings analysis.Footnote28 The implication is that a healthy economy provides consumers with an income stream with which to meet their PCP payment commitments comfortably. Indeed, there is evidence that current economic stagnation is reducing investor appetite for PCP receivables somewhat (Kirlew Citation2022).

Investors also need reassurance that there is a high degree of disciplinary apparatus available to the lender throughout the period of the finance agreement to maintain consumers’ monthly payments. Once again, the importance of the agency of dealerships looms large. This is highlighted by the considerable detail provided to credit ratings agencies by lenders regarding the disciplinary procedures in place. This is a small excerpt of an example of a much longer accounting provided to credit markets.

The borrowers pay a fixed monthly instalment under the loan contracts and are contractually obligated to pay by [monthly] direct debit (DD). Customers in arrears are managed locally within the branch and each branch has its own Collections team.

The arrears management process starts at a very early stage. After day two, and once it has been confirmed that the DD has been rejected, early arrears activity is initiated. Automated letters [are sent] and outgoing telephone contact [is made] to encourage the borrower to keep up the payments. [The lender] also offers a range of options including reduced payment for helping customers through periods of financial difficulty. However, no restructuring of agreements is permitted.

The collection strategy progresses quickly to one of loss mitigation if no suitable arrangements have been promptly made. If there is no expectation the customer will be able to pay, with a notice of default typically being issued on day 10 in arrears and the contract being terminated at around 70–80 days in arrears. (Fitch Citation2016, p. 10)

The termination of the contract would lead to repossession of the associated vehicle. Investor reports do not need to spell out the power this threat has over car consumers: that is provided by pervasiveness of the culture of car dependency in society. To illustrate the point, car finance is considered by the UK Government’s Money and Pensions service to be a ‘priority debt’, alongside, for example, mortgage payments and utilities bills, which must be paid in order to avoid losing something essential. As it observes, finance ‘payments for a car might be a priority debt if you need the car to commute to work’ (Money Helper Citation2022, p. 10), for example.

This prioritisation of payments by consumers is galvanised by a scarcity of consumer protection and regulation in consumer car finance. By contrast, missed mortgage payments must go through a foreclosure or repossession procedure, under which the borrower has certain rights, not least to request a delay in eviction. No such provision pertains to car finance, and vehicle repossession can happen quickly. There is also a strong (although not necessarily easy to untangle) relationship between car dependence, income level and exposure to consumer car debt. Walks (Citation2018), in a case study of Canadian cities, found that in most locations there ‘was a strong relationship between automobile dependence and the burden of automobile loans among lower-income households’ (p. 148). PCP lending expands using consumers’ fear of the risk of losing access to a car, in an increasingly car dependent society, as leverage.

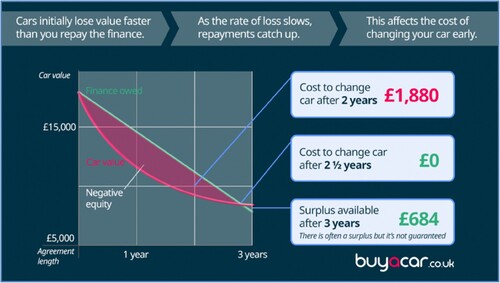

PCPs also create extra financial risks for consumers related to depreciation that are not present in HP deals. Whereas homeowners can reasonably expect their property to increase in value over time, cars are almost certain to depreciate in value – the fastest depreciation occurs immediately after the car is purchased. Despite this, PCP deals are structured ‘as if’ straight line depreciation existed. This is illustrated well in , below. The difference between the straight line finance repayments and uneven real depreciation creates mid-contract ‘negative equity’, where the value of the car has declined faster than the consumer has paid off their loan.

Figure 6. Illustration of negative equity formation in an example of a PCP deal.Footnote29

Once again, the nature of the PCP structure is to load consumers with as much debt as possible. If repayments were to track the resale value of vehicles more accurately, this would necessitate higher up-front costs to the consumer, making the consumption of higher priced vehicles more off-putting.

Should the consumer no longer be able to service their loan, they must repay the negative equity immediately. In this situation, dealerships often encourage consumers to ‘roll over’ their debt into a new financing deal. This loads the unpaid element of the existing deal, including negative equity, onto a new deal, refinancing the original debt. Of course, the risk of this dynamic leading to a personal debt spiral is high (Money Advice Trust Citation2018, Masson Citation2020). Debt compounds as the consumer borrows extra money to pay off existing debt, causing the need for further borrowing, and so on. While this also creates extra financial risks for manufacturers, it has the advantage of retaining a sufficient pool of consumers for their vehicles, and keeps monthly payments flowing to the holders of PCP receivables.

The overall effect of the rise of PCPs can be appreciated in macro indicators, which show a growing spread between amounts borrowed and consumers’ income, as can be seen in , below. As industry news organisation CarExpert comments, ‘The current risk is that car finance debt has grown so much over the last decade that increasing financial pressures on a large number of borrowers could lead to widespread defaulting, which could collapse the whole house of cards’ (Masson Citation2022).

Figure 7. Average amount financed per new car (£, left axis) and average weekly earnings (£, right axis). Nominal figures.Footnote30

Indeed, the increasing debt taken on by households from PCPs has been the subject of concern to the Bank of England, whose job it is to evaluate ‘systemic risk’. Its Prudential Regulation Authority (PRA) notes that the rise of PCPs is associated with car finance becoming the fastest expanding sector of consumer finance, which they found to be an increasing risk both to lenders themselves and to overall financial stability (Citation2017).

However, and as the PRA indicates, consumer default is only one of two primary risks to lenders in PCPs. The other is the ‘residual value’ of vehicles at the end of the contract term. If this is below the guaranteed minimum future value estimated at the signing of the contract, because of quicker than expected depreciation, then the lending party loses money. Therefore the financial health of lenders depends considerably on the value of used cars. The Covid crisis has heavily disrupted the long, highly synchronised supply chains that car manufacturing relies on, and severely reduced the supply of new vehicles. While this has caused significant financial problems for car manufacturers, a fortunate side-effect is that it has inflated used car demand, and, therefore, used car prices, creating a positive spread between projected and actual values in PCP contracts (Barrett Citation2020, Sharpe Citation2022). But this is likely to be a temporary phenomenon; the preceding analysis of industry economics would suggest that the industry needs to return to scale to avoid crisis, thus increasing the throughput of new vehicles. This highlights a key contradiction of PCPs as a mechanism to sustain manufacturers’ profit margins: the main advantage of PCPs to manufacturers is that they help create the conditions for sustaining historically high levels of new car production, but those new cars quickly add to the pool of high quality, nearly new used cars available on the market, undermining the financial value of all existing PCP receivables attached to new vehicles. In the long run PCP financing undermines itself.

One response to this problem has been the emergence of PCP loans for used cars (Haynes Citation2022). This increases the demand for used cars, thus inflating the value of new car finance securities. This is good example of financialisaton’s runaway effects. With a limited number of potential consumers, it is not possible to inflate demand in both the new and used car markets in perpetuity.

This section has discussed the diffusion of financial risks associated with the rise of PCPs. Returning to the 10Cs, it has demonstrated a complex extension of risks between car manufacturers and consumers. PCPs create additional financial risks for consumers, in the sense that they encourage consumers to borrow more money to finance their car consumption, relative to their earnings, than was previously the case. Although, in theory, these risks are reduced thanks to the consumer being able to hand back their car to the manufacturer at contract termination to walk away from further financial responsibility for the vehicle, they are at additional risk if the contract becomes unaffordable mid-term due the existence of (temporary) negative equity. This fact, alongside others such as the availability of non-manufacturer supplied finance options, is often closed to consumers during sales transactions. Dealerships perform an important role in constructing PCP deals by matching consumers with vehicles, driven by commission models which load consumers with as much debt as possible. By doing so, they help to conform car consumption habits to the economic priorities of producers, which must maintain new car sales at historic rates to avoid significant capital write-off. The qualitative leap in the extension of credit to consumers that PCPs create is predicated on a construal of consumers’ potential default levels, which is predicated upon a harsh regime for dealing with missed payments, and which understands that default risk is depressed by the dependence of consumers on their vehicles.

Linking production, consumption and consumer finance as an integrated system of provision reveals that PCPs have benefitted the car industry by encouraging consumers to share in the increased financial risk that the industry is taking on to sustain sales volumes, and increase sales values, in mature markets. But rather than resolving the economic contradictions inherent in production, this has simply displaced them onto a wider sphere, and extended the scope of the potential fallout far beyond the industry itself. Loading consumers with ever increasing quantities of debt, spurred-on by questionable retailing practices, risks widespread default. Significant changes in consumers’ ability to repay, or in used vehicle values, or a continuing shift to higher central bank interest rates, could necessitate extensive bailouts of car manufacturers and their financial backers. In other words, as with the subprime mortgage crisis and PPI scandal, there is a significant chance that the externalisation of the car industries’ contradictions leads to much more extensively collectivised problems, calling on significant state intervention.

Conclusion

This article has used the SoP approach, combined with selective use of the 10Cs, to understand the dynamics and implications of the financialisation of car consumption, using the rise of PCPs in the UK as an illustrative case study.

Its findings should be treated with some caution: public access to car industry economic data is extremely limited. The financialisation of car consumption is therefore largely closed, except for a limited range of indicators sporadically published by industry associations. It can therefore be of little surprise that this is the first academic article which seeks to understand it, despite the breadth of its implications across fundamental areas of public policy, and therefore the potential for democratic contestation and debate is currently extremely limited.

This article has demonstrated that the context of the whole system of provision is important to grasp when seeking to account for the material cultures surrounding the financialisation of consumption. Car manufacturers have promoted PCPs to solve long-running problems in their business model related to the need to maintain a certain level of ongoing new car consumption to conform with path-dependent patterns of production. In doing so, they have partly exported their own financial risk onto consumers, leveraging what is widely construed as consumers’ material dependency on their vehicles for transport to do so. At the same time, they have left themselves more vulnerable to the chaos of uncontrollable economic factors, such as consumers’ income levels, used car values, and central bank interest rates. Given the size of the debt PCPs create, the personal and industry financial risks can also be seen as implying potential systemic financial risk, with significant collective impacts.Footnote31

This analysis suggests a number of implications, which could be elaborated with further research. Firstly, given the prevalence of PCPs, and their associated economic risks, there is an urgent need to make public the fundamental financial data underpinning them. This could help create a debate around the appropriate levels of regulation, which is not currently possible to have.

Secondly, the financial structure of PCPs depends on consumers’ car dependency, as well as reinforcing it. This underlines the importance of the provision of both alternative models of vehicle access (such as share clubs) and alternatives to car use (such public transport and active travel), to allow consumers to ‘climb down’ from the financial risk car consumption creates for them. Provided at scale, this would fundamentally challenge the economics of car manufacturers. This would mean a significant repositioning of state priorities from propping up the car industry to managing its decline.

Thirdly, private motor vehicles collectively form one of the largest emitting sectors in advanced economies – some 19 per cent of territorial greenhouse gas emissions in the UK, for example.Footnote32 ‘De-motorisation’ is therefore a necessary comportment of any serious decarbonisation strategy.Footnote33 Yet efforts to tackle car dependency (such a new charges and reductions in motor vehicle road space) are frequently subject to popular opposition,Footnote34 because they challenge the culture of motorisation, which itself inseparable from elite political strategy to foster a cultural hegemony in support of capitalism around private consumption. Heightened public understanding of the nefarious ways in which new forms of consumer car finance increase consumers’ financial risk could modestly contribute towards building support for what Fraser (Citation2022) refers to as a potential and necessary ‘counterhegmonic project for eco-societal transformation’ (p. 112).

Eschewing such political bravery, the UK government (like many others) posits an increased uptake of electric vehicles (EVs) as the primary method to reduce transport carbon emissions, rather than a reduction of movement or a significant shift to public transport (Marsden Citation2023). Yet relying on electrification risks under-playing the carbon-intensive nature of electric vehicle construction, aside from the other negative social consequences of mass motoring.

Moreover the EV ‘revolution’ has coincided with a significant increase in vehicle weight and size, which can be seen on any high street as a proliferation of large sports utility vehicles (SUVs), often replacing smaller family cars. This development has been a boon for manufacturers (Keil and Steinberger Citation2023), who are able to charge much higher prices for these vehicles, despite similar production costs to smaller cars.Footnote35 SUVs, like other cars, are increasingly engineered to be (part) electrified. This means that any cost savings from fuel that electrification brings is likely being used by consumers to fund an increase in vehicle mass, thus severely reducing the already limited carbon emission reduction potential of electrification (Anable et al. Citation2019; International Energy Agency Citation2019, pp. 147–55, Galvin Citation2022). Further research is needed into how PCPs have helped shape consumer preferences for larger and more polluting vehicles, how that has interacted with electrification, and what the consequences are for decarbonisation.Footnote36

While much commentary poses new forms of car consumer finance as conforming to changing consumer preferences, this article suggests that demand has been shaped as a result of a need by car manufacturers to address profit realisation problems created by the nature of car production. Rather than characterising a fleet footedness in meeting rapidly changing consumer expectations, the rise of PCPs reflect a considerable inflexibility in the car industry, which has struggled to overcome the economic limitations imposed by its own success, and which is increasingly battling political demands for change.

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to thank the following people for their help and advice during the research and writing process: Ben Fine, Kate Hardy, Mike Haynes, A. Katharina Keil, Greg Marsden, Giulio Mattioli, Paul Nieuwenhuis, Cameron Roberts, and Julia Steinberger. The usual disclaimer applies.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Tom Haines-Doran

Tom Haines-Doran is a political economist, specialising in social infrastructure, financialisation, social movement practices and the application of political economy to inform public policy. He currently works at the University of Leeds Business School, leading on economic research impact work, alongside regional public authority partners, as part of the Yorkshire & Humber Policy Engagement & Research Network. He previously worked at the Living Well Within Limits project at the University of Leeds, and has published a monograph on the political economy of rail privatisation, based on his PhD research at SOAS, University of London.

Notes

1 PCP deals are also available in Italy, the Netherlands, South Africa and Russia and ‘similar deals centred on monthly repayment of depreciation’ can be found in ‘in Australia, Canada, China, Switzerland and Germany’ (McElvaney et al., Citation2018, p. 230). Sherman et al. (Citation2018) also list France and Ireland as significant PCP markets.

2 For in an illustration of the UK’s motorisation rate compared to other countries, see Our world in data (Citationno date).

3 Taken from Department for Transport [DfT] (Citation2023). Note that statistics are for ‘cars, vans and taxis’.

4 The Finance and Leasing association (FLA) estimates that 84% of new cars are purchased using consumer finance at dealerships. Masson (Citation2023) suggests the figure could be higher, as alternative financing arrangements are not included. For example, ‘subscription’ models are becoming more popular, and are beginning to question the role of ‘ownership’ altogether (Cottle Citation2023).

5 Bank of England data reproduced in Treanor (Citation2017).

6 According to FLA data reported in Masson (Citation2023). This figure includes finance for used vehicles.

7 For example, the financialisation of household consumption has been a long running theme in New Political Economy, including in water (Bayliss Citation2017), the media (Happer Citation2017), welfare services (Donoghue Citation2022; Dowling Citation2017; Spies-Butcher and Bryant Citation2018), housing (Montgomerie and Büdenbender Citation2015; Robertson Citation2017) and pensions (Langley Citation2004).

8 Lock (Citation2003, p. 8) suggests PCPs were conceived in the 1990s to serve what was presumably an initially niche market.

9 Based on searches by the author for PCP deals for new cars across a range of price categories for current car prices and finance deals in June 2023 at Lookers.com, one of the largest UK new car dealership chains, and based on a range of examples in the trade press.

10 Example using Halifax’s car finance calculator tool: https://www.halifax.co.uk/car-finance/calculator.html. To check that these results are significant across finance providers, the same search terms were used in the car dealership Lookers.com, which produced very similar results. In all cases, websites only produce comparisons showing HPs as a month longer than PCP equivalent deals.

11 Taken from Fitch (Citation2018, p. 3).

12 Bavarian Sky UK 2 plc annual report and financial statements for the year ended 31 December 2019, p. 4.

13 For a further explanation of A and B notes, see Downey (Citation2022).

14 Bavarian Sky UK 2 plc annual report and financial statements for the year ended 31 December 2019, p. 28.

15 This is predicated on Bayliss’ and Fine’s view, which characterises financialisation as the extensive and intensive expansion of interest bearing capital in economic and social reproduction. For an elaboration see Bayliss et al. (Citation2017).

16 See, for example, the anonymous FLA spokesperson cited in Evans (Citation2023), Briscoe (Citation2016), Clayton (Citation2018), Dines (Citation2019) and Partington (Citation2017).

17 See endnote 5.

18 Company cars account for 54% of new cars registered (Department for Transport and Driver and Vehicle Licensing Agency Citation2022). This is significant, with a number of potential effects on the cultures of car consumption. Company cars involve private car consumption, but provided to employees by their employers. Employers may own, lease, or hire the vehicles in question. As such, a number of financing mechanisms are in place for company car consumption (What’s the best way to finance vehicles for my business? Citation2022). There is no space here to discuss this and further research is needed.

19 Registrations do not equal new car sales to private consumers (for example, some cars are sold to car rental firms, and dealerships often ‘self-register’ vehicles), but in the absence of other data, registration volumes give a sense of long term sales trends.

20 Taken from Chart 1 in Driver and Vehicle Licensing Agency (Citation2022). Amended to display cars and light vehicles only (long run data that excludes ‘light good vehicles’ is not available, although recent data in this series suggests private car registrations account for around 80% of vehicles in this category). Recession data collated by the DfT, and released to the author via email.

21 See North (Citation2021) and Cap HPI (Citation2018). Adjusted for inflation, at 2022 prices, by author’s calculation, using treasury deflators.

22 Proportion of PCP to total financing for 2009 to 2016 calculated using data from the chart ‘Buyers have become more likely to get a car on finance’ in Peachey (Citation2017). Underlying data extracted using WebPlotDigitiser (https://apps.automeris.io/wpd/). For 2019 to 2021, PCP proportion was calculated from FLA data in McElroy (Citation2020), and FLA (Citation2020, Citation2021). No data is available to calculate PCP proportions in 2017 and 2018. Average amount financed per car derived from FLA data reproduced in Masson (Citation2022), and adjusted for inflation at 2022 prices, by the author, using Treasury deflators. Figures relate to dealership finance only, and to sales – not registrations.

23 Data from the FLA, reproduced in Masson (Citation2022), and adjusted for inflation, at 2022 prices, by the author, using Treasury deflators. Figures relate to dealership finance only, and to sales – not registrations.

24 See, for example, do Carmo et al. (Citation2021).

25 Indeed, PCP contracts are difficult to understand, thanks to their complexity (McElvaney et al. Citation2018).

26 The National Franchised Dealers Association complains about the high levels of existing control by manufacturers over dealerships through franchise agreements (National Franchised Dealers Association Citation2021).

27 See also Masson (Citation2015).

28 See, for example, Fitch (Citation2016, Citation2017a, Citation2017b, Citation2018, Citation2019).

29 Taken from BuyaCar (Citation2022).

30 Data from FLA and Office for National Statistics, as reported in Masson (Citation2022).

31 As has recently been recognised by the Bank of England (Haynes Citation2022).

32 Author’s calculations, based on data relating to 2019 – the last year with published data before Covid lockdowns obscured long-term trends – in Department fort Energy Security & Net Zero (Citation2023), Table 1.2.

33 As, for example, the UK’s Climate Change Commission (Citation2020) finds.

34 See, for example, the opposition generated to repurpose road space for bike lanes, or ‘bikelash’ (Field et al. Citation2018; Wild et al. Citation2018).

35 While data on the UK market specifically is not publicly available, automotive data analysts Jato estimate that, in the overall European market, SUVs retail at 59% higher price than hatchbacks, on average (Munoz Citation2021).

36 For example, it is perhaps too early to tell how a recent trend toward manufacturers selling directly to consumers through ‘agency’ dealerships will interact with the financialisation of consumption, although it is already becoming a more popular way for consumers to access EVs (see Walker Citation2023).

References

- Anable, J., Brand, C., and Mullen, C., 2019. Transport: Taming of the SUV? In: J. Watson, ed. Review of energy policy 2019. London: UK Energy Research Centre, 10–11. Available from: https://d2e1qxpsswcpgz.cloudfront.net/uploads/2020/03/ukerc_review_energy_policy_19.pdf [Accessed 08 Jun 2023].

- Apex Insight., 2017. UK car dealer point of sale finance: Market insight report 2017. Available from: https://www.credit-connect.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/Apex-Insight-Car-Dealer-Finance-Summary.pdf [Accessed 08 Jun 2023].

- Baily, M.N., et al. 2005. Increasing global competition and labor productivity: Lessons from the US automotive industry. Mckensie Global Institute. Available from: https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/mckinsey/business%20functions/economic%20studies%20temp/our%20insights/increasing%20global%20competition%20and%20labor%20productivity/mgi_lessons_from_auto_industry_full%20report.pdf [Accessed 08 Jun 2023].

- Bank of England Prudential Regulation Authority, 2017. PRA Statement on consumer credit. Available from: https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/prudential-regulation/publication/2017/pra-statement-on-consumer-credit [Accessed 01 Sep 2023].

- Barrett, C., 2020. PCP car loans: An accident waiting to happen? Financial Times, 24 November. Available from: https://www.ft.com/content/99302212-a59e-466e-9b59-13015cd2ab10 [Accessed 01 Sep 2023].

- Bayliss, K., 2017. Material cultures of water financialisation in England and Wales. New political economy, 22 (4), 383–97.

- Bayliss, K., and Fine, B., 2020. A guide to the systems of provision approach: Who gets what, how and why. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Bayliss, K., Fine, B., and Robertson, M., 2017. Introduction to special issue on the material cultures of financialisation. New political economy, 22 (4), 355–70.

- Briscoe, N. 2016. PCPs may leave motorists out of pocket at trade-in time, The Irish Times, 20 June. Available from: https://www.irishtimes.com/life-and-style/motors/pcps-may-leave-motorists-out-of-pocket-at-trade-in-time-1.2687302 [Accessed 08 Jun 2023].

- Bryant, C. 2023. Britons will struggle to stay on the posh car treadmill, Washington Post, 26 January. Available from: https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/britons-willstruggle-to-stay-on-the-posh-car-treadmill/2023/01/26/39e017a4-9d39-11ed-93e0-38551e88239c_story.html [Accessed 08 Jun 2023].

- BuyaCar. 2022. Selling a PCP car: your rights during, and at the end of, a finance agreement. Buyacar, 24 June. Available from: https://www.buyacar.co.uk/car-finance/838/selling-a-pcp-car-your-rights-during-and-at-the-end-of-a-finance-agreement [Accessed 08 Jun 2023].

- Calder, L., 1999. Financing the American dream a cultural history of consumer credit. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Cap HPI, 2018. New car prices rise 38% in last decade. Cap HPI, 12 March. Available from: https://web.archive.org/web/20201206085050/https://www.hpi.co.uk/content/car-valuations/new-car-prices-rise-38-last-decade/, https://web.archive.org/web/20201206085050/https://www.hpi.co.uk/content/car-valuations/new-car-prices-rise-38-last-decade/ [Accessed 08 Jun 2023].

- Clayton, J. 2018. How dealers can grow share of the used car finance market. Car Dealer Magazine, 14 May. Available from: https://cardealermagazine.co.uk/publish/sponsored-dealers-can-grow-share-used-car-finance-market/150656 [Accessed 08 Jun 2023].

- Climate Change Commission. 2020. The sixth carbon budget: Surface transport. Available from: https://www.theccc.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Sector-summary-Surface-transport.pdf [Accessed 18 Aug 2023].

- Cottle, P. 2023. How to understand the subscription approach to car finance. Institute of the Motor Industry, 16 May. Available from: https://tide.theimi.org.uk/industry-latest/motorpro/how-understand-subscription-approach-car-finance [Accessed 08 Jun 2023].

- Department for Energy Security & Net Zero. 2023. Final UK greenhouse gas emissions national statistics 1990–2021. Available from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1146751/final-greenhouse-gas-emissions-tables-2021.xlsx [Accessed 21 Aug 2023].

- Department for Transport. 2023. Modal comparisons (TSGB01). Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistical-data-sets/tsgb01-modal-comparisons [Accessed 08 Jun 2023].

- Department for Transport and Driver and Vehicle Licensing Agency., 2022. Vehicles registered for the first time by body type and keepership (private and company) (VEH1152). Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistical-data-sets/vehicle-licensing-statistics-data-tables#all-vehicles [Accessed 15 Aug 2023].

- Dines, T. 2019. Have we given up on owning cars? Investors’ Chronicle, 31 December. Available from: https://www.investorschronicle.co.uk/sector-focus/2019/12/31/have-we-given-up-on-owning-cars/ [Accessed 08 Jun 2023].

- do Carmo, M.J., Neto, M.S., and Donadone, J.C., 2021. Financialisation in the automotive industry: Capital and labour in contemporary society. London: Routledge.

- Donoghue, M., 2022. Resilience, discipline and financialisation in the UK’s liberal welfare state. New political economy, 27 (3), 504–16.

- Dowling, E., 2017. In the wake of austerity: social impact bonds and the financialisation of the welfare state in Britain. New political economy, 22 (3), 294–310.

- Downey, L. 2022. A-note, Investopedia, 23 July. Available from: https://www.investopedia.com/terms/a/a-note.asp#:~:text=This%20senior%20status%20allows%20the,a%20%E2%80%9Cclass%20A%20note.%E2%80%9D [Accessed 08 Jun 2023].

- Driver and Vehicle Licensing Agency. 2022. Vehicle licensing statistics: 2021. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/vehicle-licensing-statistics-2021/vehicle-licensing-statistics-2021 [Accessed 08 Jun 2023].

- Evans, C. 2023. PCP or HP: which car finance option makes most sense? What Car? 31 May. Available from: https://www.whatcar.com/advice/buying/pcp-or-hp-which-car-finance-option-makes-most-sense/n1163 [Accessed 08 Jun 2023].

- Field, A., et al., 2018. Encountering bikelash: Experiences and lessons from New Zealand communities. Journal of transport & health, 11, 130–40.

- Finance and Leasing Association. 2020. Motor finance statistics. Finance and Leasing Association. Available from: https://web.archive.org/web/20210613150406/https://www.fla.org.uk/research/motor-finance-key-statistics/ [Accessed 08 Jun 2023].

- Finance and Leasing Association. 2021. Motor finance statistics. Finance and Leasing Association. Available from: https://web.archive.org/web/20221221053421/https://www.fla.org.uk/research/motor-finance-key-statistics/ [Accessed 08 Jun 2023].

- Financial Conduct Authority. 2019. Our work on motor finance – Final findings. Available from: https://www.fca.org.uk/publication/multi-firm-reviews/our-work-on-motor-financefinal-findings.pdf [Accessed 08 Jun 2023].

- Financial Conduct Authority. 2020. Motor finance discretionary commission models and consumer credit commission disclosure – Feedback on CP19/28 and final rules. Policy statement PS20/8. Available from: https://www.fca.org.uk/publication/policy/ps20-8.pdf [Accessed 08 Jun 2023].

- Fine, B., and Bayliss, K., 2021. A guide to the systems of provision approach: Who gets what, how and why. Cham: Springer Nature.

- Fine, B., Bayliss, K., and Robertson, M., 2018. The systems of provision approach to understanding consumption. In: O. Kravets, ed. The SAGE handbook of consumer culture. London: Sage, 27–42.

- Fitch. 2016. Orbita Funding 2016-1 plc: New issue. Available from: www.fitchratings.com [Accessed 08 Jun 2023].

- Fitch. 2017a. Fitch: UK auto ABS resilient but PCP rise adds to value risk. Available from: www.fitchratings.com [Accessed 08 Jun 2023].

- Fitch. 2017b. Orbita Funding 2017-1 plc. Available from: www.fitchratings.com [Accessed 08 Jun 2023].

- Fitch. 2018. Bavarian Sky UK 2 plc. Available from: www.fitchratings.com [Accessed 08 Jun 2023].

- Fitch. 2019. Fitch ratings: European auto ABS index stable despite steep decline in UK used car values. Available from: www.fitchratings.com [Accessed 08 Jun 2023].

- Fraser, N., 2022. Cannibal capitalism: How our system is devouring democracy, care and the planet – and what we can do about it. London: Verso.

- Galvin, R., 2022. Are electric vehicles getting too big and heavy? Modelling future vehicle journeying demand on a decarbonized US electricity grid. Energy policy, 161, 112746.

- Gramsci, A., 1985. Selections from the prison notebooks. London: Lawrence and Wishart.

- Happer, C., 2017. Financialisation, media and social change. New political economy, 22 (4), 437–49.

- Haynes, T. 2022. Why Britain’s debt-fuelled new car addiction is coming to an end, The Telegraph, 22 October. Available from: https://www.telegraph.co.uk/money/consumer-affairs/why-britains-debt-fuelled-new-car-addiction-coming-end/ [Accessed 08 Jun 2023].

- Hymel, K.M., Small, K.A., and Van Dender, K., 2010. Induced demand and rebound effects in road transport. Transportation research part B: methodological, 44 (10), 1220–41.

- International Energy Agency, 2019. World energy outlook 2019. Available from: https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/98909c1b-aabc-4797-9926-35307b418cdb/WEO2019-free.pdf [Accessed 01 Sep 2023].

- Jeekel, H., 2016. The car-dependent society: A European perspective. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Keil, A.K., and Steinberger, J.K., 2023. Cars, capitalism and ecological crises: understanding systemic barriers to a sustainability transition in the German car industry. New political economy, https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2023.2223132.

- Kirlew, D. 2022. UK recession is shifting the goal posts for consumer car finance, AM Online. Available from: https://www.am-online.com/dealer-management/finance-and-insurance/uk-recession-is-shifting-the-goal-posts-in-consumer-car-finance [Accessed 08 Jun 2023].

- Langley, P., 2004. In the eye of the ‘perfect storm’: The final salary pensions crisis and financialisation of Anglo-American capitalism. New political economy, 9 (4), 539–58.

- Lessambo, F.I., 2021. International finance: New players and global markets. Cham: Springer Nature.

- Leyshon, A., and Thrift, N., 2007. The capitalization of almost everything: The future of finance and capitalism. Theory, culture & society, 24 (7-8), 97–115.

- Lock, V., 2003. Review of the leasing and asset-finance industry. In: C. Boobyer, ed. Leasing and asset finance: The comprehensive guide for practitioners. London: Euromoney, 1–10.

- Marsden, G. 2023. Reverse gear: The reality and implications of national transport emission reduction policies. Centre for Research into Energy Demand Solutions. Available from: https://www.creds.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/CREDS-Reverse-gear-2023.pdf [Accessed 08 Jun 2023].

- Martinuzzi, A., et al. 2011. CSR activities and impacts of the automotive sector, RIMAS Working Papers, 3/2011. Available from: https://www.sustainability.eu/pdf/csr/impact/IMPACT_Sector_Profile_AUTOMOTIVE.pdf [Accessed 08 Jun 2023].

- Masson, S. 2015. Car finance jargon confuses UK drivers. The Car Expert, 17 July. Available from: https://www.thecarexpert.co.uk/car-finance-jargon-confuses-uk-drivers/ [Accessed 08 Jun 2023].

- Masson, S. 2019. Car finance: The early upgrade myth. The Car Expert, 4 November. Available from: https://www.thecarexpert.co.uk/car-finance-the-early-upgrade-myth/ [Accessed 08 Jun 2023].

- Masson, S. 2020. Car finance: Negative equity and why it’s a problem. The Car Expert, 8 August. Available from: https://www.thecarexpert.co.uk/car-finance-negative-equity/ [Accessed 08 Jun 2023].

- Masson, S. 2022. Endless growth in car finance threatens household budgets. The Car Expert, 12 October. Available from: https://www.thecarexpert.co.uk/endless-growth-in-car-finance-threatens-household-budgets/ [Accessed 08 Jun 2023].

- Masson, S. 2023. Car finance debt continued growing in 2022. The Car Expert, 23 February. Available from: https://www.thecarexpert.co.uk/car-finance-debt-continued-growing-in-2022/ [Accessed 08 Jun 2023].

- Mattioli, G., et al., 2020. The political economy of car dependence: A systems of provision approach. Energy research & social science, 66, 101486.

- Mattioli, G., 2021. Transport poverty and car dependence: A European perspective. In: R. Pereira, and G. Boisjoly, eds. Social issues in transport planning. Cambridge, MA: Academic Press, 101–33.

- McElroy, C. 2020. Crisis looms for motor finance industry as coronavirus threatens lease payments, S&P Global Market Intelligence, 30 April. Available from: https://www.spglobal.com/marketintelligence/en/news-insights/latest-news-headlines/crisis-looms-for-motor-finance-industry-as-coronavirus-threatens-lease-payments-58297617 [Accessed 08 Jun 2023].

- McElvaney, T.J., Lunn, P.D., and McGowan, F.P., 2018. Do consumers understand PCP car finance? An experimental investigation. Journal of consumer policy, 41, 229–55.

- Metz, D., 2013. Peak car and beyond: The fourth era of travel. Transport reviews, 33 (3), 255–70.

- Milligan, B. 2017. Car finance deals: Do they spell trouble? BBC News, 21 April. Available from: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-39666802 [Accessed 08 Jun 2023].

- Money Advice Trust. 2018. A decade in debt: How the UK’s debt landscape has changed from 2008 to 2018, as seen at National Debtline. Available from: https://www.moneyadvicetrust.org/media/documents/Money_Advice_Trust_A_decade_in_debt_September_2018.pdf? [Accessed 08 Jun 2023].

- Money Helper. 2022. Help with the cost of living. Available from: https://www.moneyhelper.org.uk/content/dam/maps/en/money-troubles/help-with-cost-of-living.pdf [Accessed 08 Jun 2023].

- Montgomerie, J., and Büdenbender, M., 2015. Round the houses: Homeownership and failures of asset-based welfare in the United Kingdom. New political economy, 20 (3), 386–405.

- Munoz, F. 2021. OEMs are selling more SUVs but are they selling more vehicles? JATO Blog, 19 October. Available from: https://www.jato.com/oems-are-selling-more-suvs-but-are-they-selling-more-vehicles/ [Accessed 08 Jun 2023].

- National Franchised Dealers Association. 2019. Strong online presence is vital, but role of dealership remains key. National Franchised Dealers Association, 23 October. Available from: https://www.nfda-uk.co.uk/press-room/press-releases/strong-online-presence-is-vital-but-role-of-dealership-remains-key [Accessed 08 Jun 2023].

- National Franchised Dealers Association. 2021. Competition and markets authority: Retained vertical agreements block exemption regulation consultation. Position paper and consultation response. National Franchised Dealers Association, July. Available from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1030686/NFDA_Response.pdf [Accessed 08 Jun 2023].

- Nieuwenhuis, P., 2015. Car manufacturing. In: P. Nieuwenhuis, and P. Wells, eds. The global automotive industry. Chichester: Wiley, 41–51.

- Nieuwenhuis, P. and Wells, P., 2003. The automotive industry and the environment. Cambridge: Woodhead Publishing.

- Nixon, G. 2023. The next mis-selling scandal is brewing: It could be your car loan. The Times, 8 April. Available from https://advance.lexis.com/ [Accessed 08 Jun 2023].

- North, J. 2021. New car prices rise five times faster than UK wages. Daily Record, 29 June. Available from: https://www.dailyrecord.co.uk/lifestyle/money/price-new-car-rising-almost-24419624 [Accessed 08 Jun 2023].

- Our world in data, no date. Registered vehicles per 1,000 people. 2017. Available from: https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/registered-vehicles-per-1000-people [Accessed 08 Jun 2023].

- Partington, R. 2017. Car finance: The fast lane to debt? The Guardian, 19 September. Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/money/2017/sep/19/car-finance-debt-dealers-consumer-credit [Accessed 08 Jun 2023].

- Peachey, K. 2017. Young and in the red: Personal debt in five charts. BBC News, 16 October. Available from: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-41609311 [Accessed 08 Jun 2023].

- Robertson, M., 2017. (De) constructing the financialised culture of owner-occupation in the UK, with the aid of the 10Cs. New political economy, 22 (4), 398–409.

- Sharpe, T., 2022. Is a 'happy accident' keeping motor finance from blowing up?. AM Online, 24 November. Available from: https://www.am-online.com/news/finance/2022/11/24/is-a-happy-accident-keeping-motor-finance-from-blowing-up [Accessed 01 Sep 2023].

- Sherman, M., Heffernan, T., and Cullen, B. 2018. An overview of the Irish PCP market (revised data). Central Bank of Ireland Economic Letter Series. Available from: https://www.centralbank.ie/docs/default-source/publications/economic-letters/vol-2018-no.2—an-overview-of-the-irish-pcp-market-(sherman-heffernan-and-cullen)-revised-september-2018.pdf [Accessed 08 Jun 2023].

- Smith, T., 2000. Technology and capital in the age of lean production: A Marxian critique of the ‘New Economy’. Albany, NY: SUNY Press.

- Spies-Butcher, B., and Bryant, G., 2018. Accounting for income-contingent loans as a policy hybrid: Politics of discretion and discipline in financialising welfare states. New political economy, 23 (6), 768–85.

- Statista. 2022. New and used car sales in the United Kingdom between 2004 and 2021. Available from: https://www.statista.com/statistics/299841/market-volumes-of-new-and-used-cars-in-the-united-kingdom/ [Accessed 17 August 2023].

- Treanor, J. 2017. Bank of England warns a consumer debt crisis could cost banks £30bn. The Guardian, 27 June. Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/business/2017/sep/25/bank-of-england-warns-a-consumer-debt-crisis-could-cost-banks-30bn [Accessed 08 Jun 2023].

- Walker, S. 2023. Agency model: It’s coming to UK car dealers but what does it mean for buyers? Auto Express, 22 July. Available from: https://www.autoexpress.co.uk/buying-car/357915/agency-model-its-coming-uk-car-dealers-what-does-it-mean-buyers#:~:text=The%20agency%20model%20is%20the,customer%20data%20in%20the%20process.&text=It%20means%20that%20everyone%20will,you%20got%20the%20best%20deal. [Accessed 18 Aug 2023].

- Walks, A., 2018. Driving the poor into debt? Automobile loans, transport disadvantage, and automobile dependence. Transport Policy, 65, 137–149. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranpol.2017.01.001.

- Wells, P., 2010. The automotive industry in an era of eco-austerity. Cheltenham: Elgar.

- Wells, P., 2013. Sustainable business models and the automotive industry: A commentary. IIMB management review, 25 (4), 228–39.

- Wells, P., 2015. The market for new cars. In: P. Nieuwenhuis, and P. Wells, eds. The global automotive industry. Chichester: Wiley, 19–28.

- What’s The Best Way To Finance Vehicles for My Business? 2022. Your finance team, 14 Feb. Available from: https://www.yourfinanceteam.co.uk/2022/02/14/whats-the-best-way-to-finance-vehicles-for-my-business/ [Accessed 18 Aug 2023].

- Wild, K., et al., 2018. Beyond ‘bikelash’: Engaging with community opposition to cycle lanes. Mobilities, 13 (4), 505–19.

- Windridge, M. 2020. Are automotive PCP (lease) schemes at odds with climate ambitions? Forbes, 14 December. Available from: https://www.forbes.com/sites/melaniewindridge/2020/12/14/are-automotive-pcp-lease-schemes-at-odds-with-climate-ambitions/ [Accessed 08 Jun 2023].