ABSTRACT

In the context of the debate surrounding and following the Brexit referendum in June 2016, credentialed economic expertise did not enjoy a privileged position within the political and policy debate. Using the contrasting cases of the Office for Budget Responsibility and Economists for Brexit/Free Trade, this paper explores the mobilisation of economic expertise within the discursive politics of Brexit under conditions of pervasive radical uncertainty. It argues that politicisation is an important factor in side-lining technocratic influence over policy choice, but that the particular type of politicisation in play (plebiscitary) meant that the input of technocratic experts was downgraded. It is a politics conducted in another register to the reasoned, evidence-based vernacular of accredited experts and the policy discourses that they work with and through. We also argue that the basic unknowability of the post-Brexit economy further impaired expert input. These limitations were acknowledged by accredited experts themselves, reducing their traction within the policy debate. This unknowability was exploited by forms of counter-expertise mobilised by the Leave campaign. The radical uncertainties of Brexit allowed in heterodox assumptions and approaches to compete on a level playing field with an approximation of what could be presented as prudent best practice.

Introduction

This article explores the discursive politics of Brexit against a wider backdrop of politicisation and depoliticisation dynamics shaping the politics of contemporary economic policy in advanced economies. By ‘discursive politics’ we mean the role of advocacy claim and counter claim in policy-oriented deliberation. Claims and counter claims are forms of communicative discourse that seek to speak to and mobilise support among particular audiences. These claims themselves are situated within broader discursive formations. The paper grapples with the puzzle that, in the context of the debate surrounding and following the Brexit referendum in Britain in June 2016, credentialed economic expertise did not enjoy a privileged position within the political and policy debate. On the face of it, this contrasts markedly with previous practice over recent decades where public policy choices were typically made within tightly circumscribed economistic parameters. The Brexit case is thus striking because it seems to represent an extraordinary instance of politics ‘escaping’ the technocratic iron cage supplied by orthodox forms of economic policy knowledge.

The literature on ‘depoliticisation’ tells a convincing story about how, in recent decades, advanced democratic states have been complicit in delegating economic policy choices away from arena of democratic contestation to non-majoritarian sites of governance (Burnham Citation2014). Depoliticisation, which – as Montague Norman’s desire to ‘knave-proof’ the inter-war Bank of England (Peden Citation2000) indicates – is in fact an inherent and long-standing feature of democratic economic governance in advanced economies (see ), is thus associated with two phenomena: (a) the assertion of executive control over governance under the guise of the application of technocratic reason to policy-making and (b) the naturalisation of a particular worldview through the institutionalisation (within e.g. central banks or fiscal councils) of otherwise contestable causal ideas and normative beliefs about the economy. The net effect of depoliticisation has been the increasing importance of economic expertise in the shaping of policy thinking. The UK is typically understood as providing a vivid illustration of these dynamics. Yet, in the single most important decision for the UK economy in a generation, one subject to extensive and vociferous public debate, credentialed economic expertise and technocratic economic governance institutions were largely side-lined. To grapple with this puzzle, we explore the idea that appeals to technocratic reason and deference to sites of expert authority work most effectively under conditions of depoliticisation. When the issue at hand is subject to political contestation (politicisation), we might expect that expert claims would struggle for traction. In part, this is because technocratic voice is, by definition, no longer privileged and protected. We also suggest that this is because the register and grammar of expertise is ill-suited to the vernacular that is typical of politicised contexts.

We thus identify a broader pathology within the politics of economic management in contemporary democratic societies, namely a tension faced by economic policy-makers between technocratic compulsions and legitimacy pressures. In the context of the Brexit referendum, these tensions were increased and exploited by the unleashing of a populist discourse informed by a plebiscitary logic, which was at odds with appeals to technocratic reason and expertise.

Our animating research question asks how economic knowledge and expertise were mobilised within the political and public debate over Brexit? We are interested in how far, within the discursive politics of Brexit, the political debate has been informed by economic expertise, and what forms of economic expertise gained traction and why.

To address this question, the empirical focus of the article homes in on two sources of economic knowledge regarding the likely impacts of Brexit on British capitalism. The first is the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR), the UK Fiscal Council set up in 2010 by the newly elected Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition to provide both independent scrutiny of the UK’s public finances and regular forecasts of the economy’s trajectory. The OBR is the prime example of the institutionalisation and privileging of economic expertise within national public life. The OBR is selected as an exemplar of and a vector for mainstream expert economic institutions forecasting the effects of Brexit. The OBR both draws on, and presents its findings within, a range of views of established expert economic bodies. OBR assessments tend to be situated in the middle ground of this assemblage of received economic wisdom (Clift Citation2023). As such, it crystallises and reflects the expert economic policy consensus on Brexit’s likely effects.

In contrast, we also examine the work undertaken by Economists for Brexit (later Economists for Free Trade), an explicitly pro-Brexit group that sought to make a positive case for leaving the EU and, eventually, the case for so-called ‘hard Brexit’. EfB/EfFT was notable for its penetration of broadcast media debate around Brexit and especially within pro-Brexit newspapers (Rosamond Citation2020). It was also responsible for providing economic forecasts of Brexit effects on the UK economy. This work, undertaken by Professor Patrick Minford and colleagues, was very much an outlier amongst bodies providing prognoses of Brexit’s economic impact (see ; Tetlow and Stojanovic Citation2018). The EfB/EfFT models worked from extremely unorthodox assumptions, and were notable for their dissenting conclusions that foresaw a positive Brexit effect on GDP growth.

Figure 2. Comparing expert assessments of Brexit’s likely economic effects on UK GDP (source Tetlow and Stojanovic Citation2018, p. 4).

Our research design involves close reading of primary documents produced by expert forecasting groups, which we have used to excavate the assumptions underlying their forecasting practices, and glean their discursive strategies. This was complemented with interviews with selected experts with first-hand experience of Brexit forecasting.

Both the OBR and EfB/EfFT can be considered as producers of economic knowledge. Each developed economic forecasts projecting how Brexit would affect the future trajectory of UK capitalism. EfFT defined themselves in opposition to an ‘establishment’ expert consensus that the OBR reflected and represented. Minford and colleagues presented themselves as anti-protectionist peoples’ champions, channelling the spirit of Cobden and Bright in their opposition to the Corn Laws over a century and a half earlier (EFB Citation2016, p. 11).

The OBR’s authority rests upon a statutory footing, but also on the expertise, widely recognised in the economics profession, of its leading ‘Budget Responsibility Committee’ members such as Professor Steven Nickell and Professor Sir Charles Bean (each of whom had held senior positions at the Bank of England before joining the OBR). Its modelling and forecasting methodologies are considered examples of mainstream best practice, and – in this case – its forecasting record appears to have out-performed its rivals (Giles Citation2019, Wren-Lewis Citation2019). None of these things is true of EfB/EfFT. We are left then with a fascinating puzzle, not only about the role of (economic) experts in the specific case of Brexit, but also related to the politics of economic ideas in conditions of politicisation more generally.

We explore the mobilisation of economic expertise within the discursive politics of Brexit under conditions of pervasive radical uncertainty. The unprecedented nature of Brexit reduced even further than normal the limited knowability and legibility of the economy which is always a background condition of economic forecasting (D’Amico and Orphanides Citation2008, Bloom Citation2014).

We argue that politicisation is an important factor in side-lining technocratic influence over policy choice, but that the particular type of politicisation (plebiscitary) meant that the input of technocratic experts was downgraded. Plebiscitary politics is conducted in another register to the fact, evidence and reason which characterises the vernacular of accredited experts and the policy discourses that they work with and through. Furthermore, the basic unknowability of the post-Brexit economy meant that expert input was further problematised. This was acknowledged by accredited experts themselves (OBR Citation2016a; Citation2018), limiting their traction in the policy debate. This radically uncertain context was exploited by the forms of counter-expertise mobilised by the Leave campaign,Footnote1 allowing radically heterodox assumptions and approaches to compete on a level playing field with an approximation of what could be presented as cautious best practice.

The plebiscitary and technocratic discursive politics of Brexit

Our suggestion is that the highly politicised conditions associated with the run-up to and the aftermath of the referendum did not necessarily banish economic consideration and speculation from the arena of public debate. However, we argue that under certain conditions (a) the advantages normally enjoyed by certain types of economic knowledge producers (credentialed technocratic bodies such as fiscal councils) are diminished and (b) the authority of the resultant claims that such bodies generate is radically reduced. In depoliticised conditions, mainstream forms of knowledge delivered by credentialed experts carry a form of authority that is hard to contest (O’Dwyer Citation2019), at least in policy-making contexts. Politicisation lessens that inherent protection around such policy knowledge and exposes it to the risk of counter-claim. Furthermore, we maintain that the Brexit process involved a particular type of politicisation, associated with a plebiscitary mode of politics (see also Dudley and Gamble Citation2023).

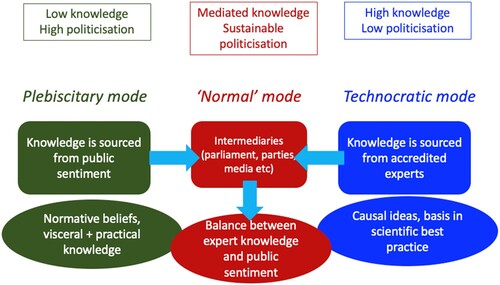

To illustrate the thrust of our argument, offers a stylised presentation of how expert knowledge sits within three ideal-typical modes of politics within democracies. The key point is firstly that expert knowledge producers find it hard to secure discursive and policy traction under conditions of high politicisation. Furthermore, the drift to a highly politicised context where the mode of politics is best described as ‘plebiscitary’ places expert knowledge in direct opposition to, and certainly exterior to the parameters of, the prevailing political-discursive style. points to some key features of Brexit. The backstory of Brexit involved Eurosceptic actors pushing for a referendum in the 2000s/2010s partly motivated by a desire to bypass ‘normal’ politics characterised by a pro-EU membership consensus. Despite that, deliberation about the consequences of the UK’s mooted departure from the EU involved extensive economic conjecture undertaken as if the technocratic default of economic policy-making was still operational.

Speaking normatively, it would have been more appropriate (as with all significant choices about the future of the UK economy) to ensure that the debate about the economic consequences of Brexit was conducted within what calls the ‘normal’ mode of politics. Here, the input of credentialed experts would have been part of the deliberative process. This existential policy choice would have been conducted within representative democratic arena of competition, involving consideration of the distributive implications of (a) ‘leave’ or ‘remain’ more generally and (b) the multiple imaginable forms of Brexit more specifically.

One helpful way of thinking about the discursive politics of Brexit is through the prism of the opposition that emerged between the plebiscitary and the normal (representative) modes as alternatives to enacting the referendum result. Put simply, between 23 June 2016 and the 2019 General Election, the political struggle over the referendum result (how to interpret it and how and whether to enact it) was organised around the drive to enact the ‘will of the people’ at all costs against the rear-guard attempt to resolve the Brexit question through standard parliamentary procedures. The peculiarly precarious party-political balance in the House of Commons increased the salience of this struggle, especially after the snap General Election of 2017. It revealed two very different conceptions of democracy, with very different understandings of the role of credentialed economic expertise in democratic policy processes. For example, under the chairmanship of Labour MP Hillary Benn, the Select Committee on the Future Relationship with the European Union became an intra-parliamentary site for the assertion of expert-sourced evidence about the implications of Brexit and as such sought to counter the plebiscitary rush to ‘hard Brexit’ favoured by the executive (Lynch et al. Citation2019). Yet this form of expert knowledge struggled for traction within the public debate because the register of Brexit discussion meant that the emotive, intuitive and moralising increasingly eclipsed the rational, dispassionate and supposedly ‘scientific’.

implies that this analysis of the discursive politics of Brexit might carry general lessons for analysing the role of economic expertise in democratic politics. For one thing, Brexit highlights the paradox of high politicisation in a low knowledge environment, and is in important respects unlike ‘classic’ depoliticisation cases. The Brexit debate entailed the mobilisation of visceral, deeply normative and often half-formed beliefs which expunged all role for causal reasoning. At the same time, the prohibition of non-compliant rationalities in the name of the overarching trumpFootnote2 card of the ‘will of the people’ actually resembles classic depoliticisation in one important respect. It entails the valorisation and normalisation of particular ways of thinking about the world and the suppression of valid grounds for contestation.

Brexit provides arguably one of the more vivid examples of the domestic politicisation of European integration. As Hooghe and Marks (Citation2009) note, the character and trajectory of domestic politicisation will vary according to the arena rules through which contestation is processed. In the case of Brexit, there were clearly two decision moments, where distinctive arena rules applied in each. The first is the referendum phase, where the arena rules were plebiscitary. The second is the parliamentary phase. In the UK-Brexit case, the key arena rule was the use of a referendum (with a very loosely formulated and vague question) to resolve the issue of EU membership, a choice that both downgraded the role of both parliamentary deliberation and political parties.

The purpose of the second phase was to process the referendum result. While the first phase involved establishing – via a crude binary referendum – ‘the will of the people’, ideal-typically at least, the second phase would give space for institutions of representative democracy to operationalise the referendum result in ways that balanced the plebiscitary impulse with forms of ‘responsible’ deliberation and scrutiny. In turn, a reasonable expectation would be that accredited expertise would play a much more prominent role in the second decision phase than the first. One caveat would be that the role of experts is likely be diminished in majoritarian parliamentary settings such as the UK, where an executive supported by a clear legislative majority could effectively bulldoze ‘the will of the people’ into a form of executive fiat, thereby weakening the role played by deliberation, scrutiny and expert advice. However, for a very significant portion of the parliamentary phase of Brexit decision-making – between the General Elections of June 2017 and December 2019 – the Conservative governments of Theresa May and Boris Johnson, while pledged to enact the ‘will of the people’ (understood as leaving both the single market and the EU customs union), were not supported by a parliamentary majority. Thus, while it is no surprise that accredited economic expertise was marginalised in the plebiscitary phase of Brexit, it is more puzzling that it seemed to have no discernible impact in terms of shaping policy choices in the parliamentary phase.

This context also raises one of the central paradoxes that this paper seeks to work with, namely the emergence of alternative forms of economic evidence, reason and claims to expertise within the Brexit debate. Our second case, EfB/EfFT, emerged as a pro-Brexit voice of ‘economists’. This raises the question of why a movement committed to undermining and displacing the input of economic expertise should seek to make quasi-technocratic claims of their own about Brexit’s impact, sourced in economic modelling of alternative Brexit scenarios (Rosamond Citation2020). This was part of a series of successful strategies from Leave campaigners and politicians seeking to neutralise technocratic economic governance voices warning of the economic harm Brexit augured.

Modelling Brexit and the limits of economic forecasting

The projections of Brexit’s economic effects by various forecasting bodies are developed using a standard counter-factual approach that constructs an artificial doppelgänger UK economy in an alternative universe where the Brexit vote never took place, or turned out differently (see ; Sampson et al. Citation2016, Tetlow and Stojanovic Citation2018). This side – steps the problem of not knowing how the economy will evolve by making conditional forecasts, trying to isolate the effects of one policy change (albeit a very major one in the shape of Brexit). As Sampson puts it,

producing conditional forecasts … What would be the effect of a given policy is, it is a much better, more tightly defined question. We can have more ability to answer with at least some degree of certainty. … to forecast ahead [to 2030] unconditionally would be a bit of a fool’s errand.Footnote3

Economic models used for forecasting are based on simplifying assumptions about the economy and policy which are both somewhat arbitrary and inherently contestable. As such, economic models are political constructs. Economic models, typically deploying sophisticated mathematical tools, are presented as powerful devices for understanding the workings of the economy and for offering rigorous and reliable forward-facing projections about economic futures (Kuorikoski et al. Citation2010). But, as critics point out, the progressive reliance on mathematical abstractions (or indeed hypothetical doppelgängers) risks detaching economic analysis (the model) from the object it purports to describe (the economy). As Watson (Citation2014) argues, the net effect is the paradoxical situation where the object of analysis – and thus ultimately of government policy – becomes the model rather than any underlying ‘real’ economy. Beyond this meta-critique sit a range of attacks on economic analysis, both in terms of the assumptions pervading mainstream neoclassical perspectives (Quiggin Citation2010) and the political (mis-)uses of cutting-edge macroeconomics (Wren-Lewis Citation2018).

The contestability of assumptions underpinning economic models, which attest to modelling’s political character, is evident even in realms where there is at first sight considerable consensus amongst most economists – for example about the benefits of freer trade. Disagreements in the debate of Brexit’s economic effects reflect, in part, dissonances regarding what ‘free trade’ means, how it should be conceived, and how to achieve it. What are the necessary, or indeed the optimal, institutional pre-conditions of free trade? Febrile political economic debate has long surrounded these questions.

For the vast majority of economists, market regulation to ensure mutual recognition of common standards and so forth, as in the regulatory infrastructure of the Single European Market (SEM), are understood as the conduit of freer trade (Vogel Citation1996, Pelkmans Citation2012). Yet on the other hand, a hyperglobal, libertarian position conceives of an absence of regulation as a manifestation of freer trade (Minford Citation2016b). Thus, in debating Brexit’s likely economic and trade effects, the different modelling assumptions underpinning various studies can reflect contested understandings of what free trade actually is.

This also points to a broader truth about economic policy commentary, prescription and projection. Economics and the economic are often presented as technical matters, abstracted from political debate and ideological argument. Yet any economic analysis is political, built on particular normative foundations and assumptions. There are limits to how far expert economic bodies are willing to acknowledge these inherently political characteristics of economic reasoning and analysis – for reasons of their own intellectual and epistemic authority. They benefit from the economics profession’s cultural cachet and its reputation as the most ‘scientific’ of the social sciences (Fourcade Citation2009).

The limited legibility and knowability of the economy establishes further bounds to the epistemic authority of economists. These limits are especially pronounced in relation to the economic effects of a Brexit phenomenon which lacked any historical precedents. It is important to avoid the trap, when counter-posing an anti-intellectual public debate with the views of credentialed economic experts, of fetishising the ‘science’ of economic models and knowledge (see Morgan Citation2012). Political economy has been pointing out the problems of the simplifying assumptions which undergird orthodox economic analysis ever since the marginalist revolution (Clarke Citation1983, Watson Citation2014).

As the austerity debate demonstrated, just the popularity of a set economic policy ideas within policy circles is neither indicative of their accuracy nor reflective of their currency within academic Economics. A policy position may have some sophisticated modelling that undergirds it, but this may still rest on flawed or questionable assumptions. There may be reasons why the insights do not apply in particular contexts (IMF Citation2010, Blyth Citation2013, Clift Citation2018).

If caution against fetishising economics as a ‘science’ is warranted for economics in general, it is especially true of forecasting and economic projections. Economic forecasters use narrow metrics, and these are constructed in ways that potentially ignore multiple factors, as with the ‘all other things being equal’ basis of conditional forecasting. Forecasters make questionable assumptions, meaning that their work inevitably involves judgement calls rooted in contestable pre-suppositions. Economic forecasts, in short, are asked to carry more weight within the economic policy process than they can bear. The general shortcomings of economic forecasting meant that Brexit projections quickly came up against the limits of the knowability of the economy. In places, economics’ knowledge base is weaker than others, confidence surrounding posited causal connections less assured.

For reasons of space, we focus on the contestable premises of two Brexit forecasting assumptions (but there are many others). Both are core moving parts of the determination of Brexit’s long-term economic effects: whether the effects of leaving a trade agreement (for example, regarding non-tariff barriers) are symmetrical to the effects of joining one, and different views on the relationship between changes in trade openness and productivity (the static versus dynamic productivity effects question). Each is crucial for Brexit forecasting. Coming to a view on these key issues determines, to a significant degree, the scale of Brexit’s predicted economic effects.

The assumptions and judgements made on each of these issues, and fed into the model, are of cardinal importance for trajectory of the economy emerging from the modelling exercise. For example, the LSE team constructed two versions of their Brexit forecasts, one with static effects, the other using dynamics effects. The size of the ‘hit’ to the UK economy was twice as large in the latter instance (Sampson et al. Citation2016). As LSE forecaster Thomas Sampson puts it, ‘that is where the art of modelling comes into it. In that we don’t know exactly how big the changes in trade cost are. So, you have to make some sort of judgment call, based on data we do have available about how big we think these changes might be’.Footnote4

Conditional Brexit forecasting, whilst it makes its own heroic ‘all other things being equal’ assumptions, at least enables addressing a relatively tightly defined question. Yet the results of such conditional forecasts can only be as reliable as the assumptions about trade costs fed into them. Those assumptions, the key moving part in any Brexit forecast, are always subject to question. Gauging assumptions about trade costs is especially challenging when trying to forecast events which lack historical precedents, such as an advanced economy leaving a free trade agreement like the SEM.

This absence of any analogues or historical precedents for leaving freer trading arrangements proved somewhat debilitating. It denies forecasters adequate parallels which can inform judgement about the likely effects, their size and temporality; ‘The historical parallels aren’t there, so that inevitably introduces uncertainty into what we are doing, even beyond the uncertainty that any empirical estimates have’.Footnote5 In relation to Brexit, while the overwhelming majority of economists anticipated adverse effects from increasing trade frictions, the ‘jury’ of the economics profession is still out on their size and duration. This makes exact calibration of crucial determining judgements challenging – whether to assume static (one-off) vs dynamic (ongoing, and perhaps increasing over time) productivity effects from reduced trade openness; or symmetrical vs asymmetrical effects of entering/ leaving a free trade association.

Assumptions about levels of trade openness and the relation to technological change and productivity increases are vital for gauging Brexit’s effects. Yet, as Sampson points out, ‘We have not got a canonical framework for thinking about how trade openness affects technology’.Footnote6 Similarly, judgements about symmetry/asymmetry, and about the path from the current situation to the new equilibrium are vitally important. Different studies take different views, but the choice is somewhat arbitrary (OBR Citation2018, pp. 30–1; Tetlow and Stojanovic Citation2018).

The currency in which Brexit’s economic impacts are counted is output relative to a phantom rate of growth UK could have enjoyed in an alternative universe. The elusiveness of this notion has implications for the discursive politics of Brexit. It proved difficult for anti-Brexit voices to mobilise these ‘lost future growth Britain could have enjoyed’ costs politically. The plausibility of that alternative doppelgänger scenario is obviously subject to some question, especially when subsequent shocks largely unrelated to Brexit have hit the UK, European and global economy.

As Siles-Brügge points out, underplaying technical and epistemic limitations of Brexit modelling and forecasting is a ‘political phenomenon’ (Citation2019, p. 7). So questioning projections of negative Brexit effects on the UK economy are not solely about a knee-jerk ‘project fear’ response of ardent Brexiteers. They may also reflect legitimate concerns about the limits of knowability of the economy, and the limits of economic forecasting as a predictive ‘science’.

In this ideational context it was difficult for non-expert audiences to distinguish ideologically driven Brexit forecasts from more reasoned assessments. Differences between those assumptions and modelling/forecasting approaches employed by the OBR et al. on the one hand, and those from EFB/EfFT on the other – proved inaccessible to a media and public uninterested in such abstruse technicalities. EfFT exploited this lack of knowledge and understanding, basking in the imprimatur their ‘economist’ status, conferred upon them by the media.

Economists and the discursive politics of Brexit

Although economic forecasting of Brexit effects was fraught with difficulties, and despite the viscerally anti-intellectual tenor of the Brexit debate, a range of bodies sought to evaluate Brexit’s likely impacts on the UK economy, remaining operationally within conventional economistic and technocratic parameters. This indicated some ongoing intellectual authority for economic expertise, even amidst an emotive and intuitive Brexit discussion. Furthermore, alternative forms of evidence and reason were at play, with established, credentialed economic bodies challenged by renegade pro-Brexit ‘experts’ proclaiming equivalence and indeed superiority. The distinctive discursive and modelling strategies of the OBR and EfFT reveal much about the discursive politics of Brexit, and the place and role of expertise within it.

The OBR

The OBR’s engagement with Brexit highlights the awkward fit between technocratic governance and a charged and highly politicised (though decidedly ill-informed) public debate. The OBR, as noted above, epitomises credentialed economic expertise. Their mandated independent medium range forecasting role inevitably drew the OBR into debates about what Brexit would mean for the UK economy.

The OBR was a young institution which prized its ‘apolitical’ self-image and had fought hard to establish its independence from the Treasury. There were strong institutional incentives to avoid the political fray (Clift Citation2023). The Office noted before the referendum that ‘Parliament has told us to prepare our forecasts on the basis of the current policy of the current Government and not to consider alternatives. So, it is not for us to judge at this stage what the impact of “Brexit” might be on the economy and the public finances’ (Citation2016a, p. 84). Indeed, to the extent possible, the OBR remained relatively quiet on Brexit. Reflecting on why, then OBR economy expert Professor Sir Charles Bean recalls ‘some of it frankly is to avoid being sucked into particularly acrimonious territory. And the question of policy design is not our role.’Footnote7

The OBR’s normal forecasting process involves the 3 person Budget Responsibility Committee making a series of key top-down judgements (about growth, productivity, for example) which shape the overall forecast. Brexit forecasting emulated this approach, adopting a number of ‘broad brush’ assumptions about Brexit’s effects on UK potential output. Key channels of influence included migration (and skills and productivity), uncertainty effects on business investment (which would reduce productivity by decreasing ‘capital deepening’), and trade frictions and their consequences (OBR Citation2016b, Box 3.1 46). Thus the first post-referendum OBR forecast, contained in the November 2016 Economic and Fiscal Outlook, made a series ‘relatively simple overarching judgments’ (Chote Citation2016) about the medium-to-long-term impact of Brexit.

OBR judgements were guided by a consensus of other expert views on both the mechanisms through which Brexit effects would impact on UK output, and also the size of effects (see ; OBR Citation2018, Tetlow and Stojanovic Citation2018). The OBR – in relation to Brexit and the UK’s economic trajectory more broadly – is always keen to locate its assessment within the range provided by other expert forecasting bodies. Sir Charles Bean noted of the OBR approach ‘as far as possible what we want to be doing is citing existing studies for the numbers that we put in rather than making up our own numbers which then … are the OBR numbers and which are then open to attack from Brexiteers and so forth.’Footnote8

This chimes with OBR self-presentation as an apolitical and scientific purveyor of fact, reason and evidence. King describes the rationale behind the OBR’s Brexit discussion paper;

to show the way we will be thinking about it and we've engaged with both ends of the spectrum when it comes to views of how this will work … We've looked at the Economists for Free Trade as well as one group at LSE who have worked with very strong dynamic costs.Footnote9

The resort to broad brush assumptions, drawn from mid-range amongst expert projections, reflects OBR acknowledgement of the technical limits of the possible with Brexit forecasting. On top of the normal levels of uncertainty and technical challenges facing any economic forecasts, OBR forecasters were keenly aware of the manifold multiple uncertainties surrounding projecting Brexit’s effects. Key amongst these were Brexit’s unprecedented character and the profound unknowability surrounding what form UK exit would take (OBR Citation2018).

The OBR projected that the economy would be around 2.5 per cent of GDP smaller three years after the referendum compared to a hypothetical doppelgänger economy where the vote had never taken place. Longer term forecasts projected reduced trade intensity, lower import penetration and decreasing export share, reflecting higher tariffs and increasing non-tariff barriers (OBR Citation2016b). The overall effect was projected – in customarily broad-brush terms – as a roughly 4 per cent of GDP hit to the economy from an orderly exit. The costs of a disorderly exist were estimated at around 6 per cent of GDP. These projections remained the OBR’s stated view right up to the UK’s formal departure from the EU. The OBR was never presented with sufficient Brexit detail that could have informed better specified assessments. As OBR BRC member Andy King put it in late 2019, ‘for the future [our Brexit projection] is still not tied to anything specific because there is nothing specific’.Footnote10

The OBR stuck with their 2016 broad brush Brexit assessments, making more specific interventions only rarely. Their July 2018 Fiscal Sustainability Report pointedly dismissed Prime Minister May’s anticipation of a mooted ‘Brexit dividend’; ‘our provisional analysis suggests Brexit is more likely to weaken the public finances than strengthen them over the medium term, thanks to its likely effect on the economy and tax revenues’ (OBR Citation2018, p. 9, 105).

In warning of the high economic costs of a ‘no deal’ Brexit, the OBR again leveraged other sources of economic expertise by deploying IMF ‘stress test’ methodologies (OBR Citation2019, pp. 10–1, 255–78). Using conservative assumptions (static rather than dynamic trade/ productivity effects) to avoid ‘Project Fear’-type accusations, their stress test was ‘by no means a worst-case scenario under a no-deal, no-transition Brexit’. This caution notwithstanding, the OBR projected significant lowering of productivity and potential output, with long run GDP down 5.9 per cent, and borrowing £30 bn a year higher on average from 2020 to 2021 onwards (Citation2019, p. 265).

Caution and circumspection couches OBR discussion of the ‘top down’ and ‘broad brush’ assumptions needed to deal with manifold Brexit uncertainties. They underline the crucial limitations that flow from the absence of historical precedents (OBR Citation2018, p. 12, 43). Given the limits of the knowability of the economy, the OBR scrupulously avoids imparting false precision to their results. OBR discursive strategy evoked their tightly defined remit (confined to ‘announced government policy’) to avoid entreaties (for example by the Treasury select committee) to offer more detailed Brexit projections. The OBR made conservative assumptions about Brexit effects – and transparently highlighted the technical limitations of attempts to render the uncertain calculable to points within a range of probable scenarios.

Pretending Brexit forecasts accurately represent the future of the economy is a political act, and a disingenuous one (Siles-Brügge Citation2019). Unlike EfFT and the Treasury (Citation2016), the OBR never pretended to greater certainty than was plausible. In this way, the OBR sought to operate as an honest broker in the debate. They moved to counter obviously bogus claims – such as the Brexit dividend – but made relatively circumspect Brexit effect assumptions, seeking to remain below the parapet. Yet the OBR’s intellectual honesty arguably contributed to its limited traction in the Brexit debate.

EfFT

Economists for Brexit (EfB) was founded in April 2016. As a pro-leave, pro-‘hard Brexit’ lobby group situated within a dense web of Conservative and libertarian think tanks, EfB (later Economists for Free Trade – EfFT) worked on behalf of a sharply defined political agenda, in stark contrast to the OBR’s self-disciplined form of technocracy. EfB/EfFT sits oddly in the context of the Leave campaign and ‘Brexitism’ more generally. Whereas the latter recurrently mobilised signature populist anti-establishment tropes in which expertise was presented as part of the problem (Brusenbauch Meislová Citation2021), EfB/EfFT presented itself as an assemblage of heterodox experts, whose legitimacy to articulate a position in debates about the UK economy’s future trajectory is based precisely on the assertion of their credentials as ‘economists’ (Rosamond Citation2020). This combination of credentialization and heterodoxy became central to the group’s self-representation. For example, EFB/EfFT directly equated themselves with Cobden and Bright fighting for repeal of the Corn Laws, pitted against the Treasury and its ‘establishment supporters’ who constitute a ‘latter day Corn Tariff apologia’ (see EFB Citation2016, pp. 1–2; Minford Citation2016a, pp. 1–3).

The EFB’s renegade analytical strategy equates their unusual conception of pure unfettered competition on ‘world prices’ as ‘free trade’ and anything that departs from it as protectionism. This view portrays the EU as a purely protectionist cabal which exists to artificially raise prices. That ‘EU protection raises consumer prices’ is a matter of prior assumption (EFB Citation2016, p. 8); ‘it is clear … a customs union, like the EU, will inflict damage on you’ (EFB Citation2016, p. 3). Thus ‘the gains from leaving the EU are principally due to effects on trade and regulation of the Single Market’ (EFB Citation2016, p. 7). This explains the EfFT’s outlier assessment of a 4 per cent boost to GDP in a hard Brexit scenario (see ). What Minford (Citation2016a, p. 14) calls ‘full free trade’ involves the UK leaving both the EU and WTO, dropping all tariffs on incoming goods and services, regardless of whether tariffs were imposed on UK exports. Minford et al. envisage elysian fields – Britain freed from the yoke of EU protectionism and restrictive practices. The sclerotic grip holding back Britain’s economic dynamism loosened, Brexit becomes a moment of welcome creative destruction.

EFB/EfFT thus interprets the single market purely as a barrier to its distinctive conception of free trade, and hence were the UK to ‘abandon all EU regulation’ this would bring ‘gains to GDP’ (EFB Citation2016, p. 8). Minford’s claim that Brexit will raise the UK’s GDP by 4 per cent as a result of increased trade stems from this (Minford Citation2015, Citation2016a). No acknowledgement is given to the trade facilitation effects of the SEM, mutual recognition and shared standards.

Confronted with early and sharp critiques of its assumptions and approach (Sampson et al. Citation2016, Van Reenan et l. Citation2016, Winters Citation2017, Citation2020), the EfB/EfFT opted for methodological attack rather than defence. Minford derides ‘modern technical “voodoo” in economics’, and its ‘clever sophisticated tricks’, presenting those questioning EfB/EfFT methods and findings as pitted against free trade and propping up EU protectionism (Citation2016a, p. 3; EFB Citation2016).

Minford and EFB/EfFT object to the Treasury’s ‘waffly claims about rigour and world-class methods’ (EFB Citation2016, p. 20). They make a series of scattered and often vague methodological critiques, notably ‘the Treasury study of Brexit options uses methods that have no foundation in economic theory’ (EFB Citation2016, p. 8). In rejecting Treasury understandings of key inter-relationships between trade openness, FDI and productivity, EFB/EfFT assert ‘what we have here again are equations that are not causal relationships but mere associations’ (Citation2016, p. 6). EFB note acerbically, ‘what marks out the gravity model is that it is a set of reduced equations masquerading as a ‘structural’ model of trade’ (Citation2016, p. 15; see also Blake Citation2016, p. 19). Minford derides the Treasury’s ‘technical tricks’ and their gravity equation approach, comparing it unfavourably to EfFT’s ‘standard trade model’, characterised as ‘a proper, underlying, structural, model’ (EFB Citation2016, p. 9; Minford Citation2016a, p. 3, 7–8).

Despite serried ranks of trade economists fundamentally questioning their approach and assumptions (see e.g. Sampson et al. Citation2016, OBR Citation2018, pp. 77–8, Tetlow and Stojanovic Citation2018), EFB/EfFT disparage what they portray as the methodological shortcomings of other approaches, asserting their superior scientific rigour (Blake Citation2016, EFB Citation2016, Minford Citation2016a). The trade costs assumptions underpinning EfFT forecasts reflect their prior ideological assumptions – in particular a stark and especially negative view of EU (and SEM regulation) trade effects. EfFT build their world view into their modelling via a bold a priori assumption about leaving the EU increasing UK trade and economic growth. Their ‘findings’ indicate that Brexit would boost GDP, perhaps by 4 per cent (for a critique see Sampson et al. Citation2016).

The real world of mutual recognition and standard setting and widespread non-tariff barriers (NTBs) formed no part of the EfFT vision of what free trade really means or looked like. ‘Health warnings’ should be attached to all Brexit forecasting exercises, and transparency regarding what assumptions they are based on is paramount (see Tetlow and Stojanovic Citation2018, pp. 5–6, 10–1, 21–3, 25–36; Siles-Brügge Citation2019, p. 8). In omitting these, EfFT claimed higher levels of rigour and reliability than their forecasting exercise could, in fact, attain. Notwithstanding EfFT assertions to the contrary, departure from the SEM increased NTBs and trade frictions, thereby increasing the costs of trade. These costs are the key input into trade models. This explains the significant adverse economic effects from Brexit anticipated in most expert forecasts (see ; OBR Citation2018, Tetlow and Stojanovic Citation2018, p. 4). Yet the unrealistic character of their projections did not undermine EfFT’s ability to present themselves and be taken seriously in the media, as economic experts informing the Brexit debate.

EfB/EfFT’s purpose was clearly not to engage in an ‘in the weeds’ argument about the propriety of rival assumptions and forecasting models. By offering an alternative project, built around its modelling of a UK economy freed from EU customs union membership and SEM regulation, it was able to offer up a dissenting view. This could be re-presented (via appearances in TV studios and through newspaper articles in pro-Brexit newspapers) as indicative of economists disagreeing about Brexit’s economic effects. The fact that the EfB/EfFT’s projection of a 4 per cent boost to GDP was (a) a huge outlier and (b) an artefact of deeply contestable modelling assumptions was of no significance in the public debate. Indeed, the very thing that cautioned the OBR (and similar organisations) in the direction of prudence – the fundamental unknowability of the UK’s post-Brexit economic future – gave crucial space and, outside of circles of professional economists, credence to the altogether more positive Brexit vision that EfFT proffered.

Conclusions

While this paper is obviously limited by its focus on the single (and potentially peculiar) case of Brexit, we offer three main conclusions that might simulate further research embracing additional cases. First, as anticipated, expert authority is seriously challenged in politicised contexts such as that provided by Brexit. But it is worth noting that the discursive politics of Brexit were situated a context where politicisation took a plebiscitary form, which further marginalised the epistemic authority of expert economic forecasting. Second, in spite of this, the Brexit experience suggests that the label ‘economist’ remains a conduit to gain a legitimate voice in the debate. Third, our case demonstrates the importance of unknowability as both a constraint on credentialed knowledge producers and a window of opportunity for those purveying heterodoxy. Indeed, as ‘reputable’ forecasters readily acknowledge, although the assumptive foundations of mainstream forecasters are carefully calibrated, all forecasts rely on assumptions which are somewhat arbitrary, debatable and contested.

The mode of political deliberation central to the discursive politics of Brexit unleashed plebiscitary modes that gave little space for expert deliberation. One intriguing aspect of the whole episode is that the ‘leave’ side felt moved to construct Brexit models at all. This points to an enduring legitimacy of technocratic knowledge, and ongoing imprimatur for economic expertise – even in inhospitable environments where populist modes of politics largely dominate the debate. Despite the visceral anti-intellectualism of Vote Leave, assorted Brexiteers, and successive Conservative Governments since the Brexit vote, it is striking that Leave/‘hard Brexit’ advocacy featured input from self-identified ‘economists’ (a few of whom were actually academic economists) who (a) went to the trouble of critique standard modelling assumptions and (b) produced alternative counterfactual projections for the post-Brexit UK economy based upon their own modelling assumptions.

This suggests the residual symbolic authority of the nomenclature ‘economist’ (a notable presence in sympathetic newspaper headlines reporting EfB/EfFT interventions in the debate – Rosamond Citation2020) and the continuing legitimacy of the idea of the economy being modelled with rigour. EfB/EfFT’s added confidence in their own approach was presumably bolstered by the fact that each side were equally hamstrung by the problems associated with modelling something that’s never happened before. The unknowability of the economy in relation to Brexit could be mobilised to present EfB/EfFT modelling and forecasting as no more or less ‘respectable’ than anyone else’s.

The OBR presented itself as an honest broker – countering bogus claims of a Brexit dividend, or unjustifiable assumptions about zero NTBs. Its due diligence in consistently pointing out the uncertainty surrounding its projections also perhaps took the sting out of their forecasts of lost growth. EfFT, by contrast, occluded the limitations of their forecasting practice when claiming their methodological superiority, and that economic benefits would accrue from Brexit.

Differences between ideologically driven as opposed to more reasoned trade cost assumptions were obscured within the discursive politics of a Brexit process riddled with radical uncertainties. EfFT’s critique may have lacked credibility within informed academic economics circles, yet it was pursued safe in the knowledge that no one in the media or public debate was going to be able to adjudicate between rival forecasts. Minford et al. were able to defend their technical authority, going on the offensive about Treasury forecasting assumptions to deflect attention from EfFT’s own shaky foundations (Minford Citation2016a). EfFT presented themselves as one side of a live debate within economics where expert opinion was genuinely divided.

EFB/EfFT can be understood as a wrecking operation, designed to neutralise the epistemic authority of credentialed economic experts projecting significant adverse economic effects from Brexit. EFB/EfFT deployed themselves in the media and within the public debate to give the impression that the upshot of varied respected economists’ opinion and wisdom on likely Brexit effects was an expert judgement score draw.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Similar dynamics were at play during the 44-day Truss premiership, Minford was brought in to an informal brains trust of unorthodox Economists in support of Truss’s attempt to overthrow the Establishment orthodoxy by sacking top Treasury Civil Servant Tom Scholar, and rejecting OBR offers of fiscal oversight of the ‘mini-Budget’.

2 Pun intended.

3 Interview with Dr Thomas Sampson at LSE, 26 June 2019.

4 Interview with Dr Thomas Sampson at LSE, 26 June 2019.

5 Interview with Dr Thomas Sampson at LSE, 26 June 2019.

6 Interview with Dr Thomas Sampson at LSE, 26 June 2019.

7 Interview with Charles Bean, 21 May 2019.

8 Interview with Prof Sir Charles Bean, 21 May 2019.

9 Interview with Andy King, OBR, 20 November 2019.

10 Interview with Andy King, OBR, 20 November 2019.

References

- Blake, D. 2016. Measurement without theory: on the extraordinary abuse of economic models in the EU Referendum debate. Available from: http://www.cass.city.ac.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0007/320758/BlakeReviewsTreasuryModels.pdf.

- Bloom, N., 2014. Fluctuations in uncertainty. Journal of economic perspectives, 28 (2), 153–76.

- Blyth, M., 2013. Austerity: the history of a dangerous idea. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Brusenbauch Meislová, M., 2021. The EU as a choice: populist and technocratic narratives of the EU in the Brexit referendum campaign. Journal of contemporary European research, 17 (2), 166–85.

- Burnham, P., 2014. Depoliticisation: economic crisis and political management. Policy & politics, 42 (2), 189–206.

- Chote, R. 2016. Evidence to the Treasury Select Committee: Autumn Statement 2016. UK Parliament website. Available from: http://data.parliament.uk/writtenevidence/committeeevidence.svc/evidencedocument/treasury-committee/autumn-statement-2016/oral/43955.html.

- Clarke, S., 1983. Marx, marginalism and modern sociology. London: Macmillan.

- Clift, B., 2018. The IMF and the politics of austerity in the wake of the global financial crisis. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Clift, B., 2023. The office for budget responsibility and the politics of technocratic economic governance. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- D’Amico, S., and Orphanides, A. 2008. Uncertainty and disagreement in economic forecasting. Federal Reserve Finance and Economics Discussion Series 2008-56. Available from: https://www.federalreserve.gov/pubs/feds/2008/200856/200856pap.pdf.

- Dudley, G., and Gamble, A., 2023. Brexit and UK policy-making: an overview. Journal of European public policy, 30 (11), 2573–2597.

- Economists for Brexit. 2016. Economists for Brexit - The Treasury Report on Brexit: a critique, 10 May 2016. Available from: https://issuu.com/efbkl/docs/economists_for_brexit_-_the_treasur/10 [Accessed 28 January 2023].

- Fourcade, M., 2009. Economists and societies: discipline and profession in the United States, Britain and France, 1890s-1990s. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Giles, C. 2019. Politics is failing on Brexit, but economics has been on the money. Financial Times, 14 March. Available at Available from: https://www.ft.com/content/534e108a-4651-11e9-b168-96a37d002cd3 [Accessed 18 March 2019].

- HM Treasury. 2016. HM Treasury analysis: the immediate economic impact of leaving the EU. UK Government website. Available from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/524967/hm_treasury_analysis_the_immediate_economic_impact_of_leaving_the_eu_web.pdf.

- Hooghe, L., and Marks, G., 2009. A postfunctionalist theory of European integration: from permissive consensus to constraining dissensus. British journal of political science, 39 (1), 1–23.

- IMF, 2010. World economic outlook October. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund.

- Kuorikoski, J., Lehtinen, A., and Marchionni, C., 2010. Economic modelling and robustness analysis. British journal of the philosophy of science, 61 (3), 541–67.

- Lynch, P., Whitaker, R., and Cygan, A., 2019. Brexit and the UK parliament: challenges and opportunities. In: T. Christiansen and D. Fromage, eds. Brexit and democracy. The role of parliaments in the UK and the European Union. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 51–79.

- Minford, P. 2015. ‘Evaluating European trading arrangements’ Cardiff Economics Working Papers No. E2015/17 November 2015.

- Minford, P. 2016a. Flawed forecast: The treasury, the EU and Britain’s future. Politeia: A Forum for Social and Economic Thinking. Available from: http://www.politeia.co.uk/wp-content/Politeia%20Documents/2016/June%20-%20Flawed%20Forecasts/'Flawed%20Forecasts'%20June%202016.pdf.

- Minford, P. 2016b. No need to queue. The benefits of free trade without trade agreements. Institute of Economic Affairs. Current Controversies Paper No. 51. Available from: https://iea.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/CC51_No%20need%20to%20queue_3.pdf.

- Morgan, M.S., 2012. The world in the model: How economists work and think. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- OBR. 2016a. Economic and fiscal outlook - March 2016. OBR website. Available from: https://obr.uk/efo/economic-fiscal-outlook-march-2016/.

- OBR. 2016b. Economic and fiscal outlook - November 2016. OBR website.

- OBR. 2018. Discussion paper No. 3: Brexit and the OBR’s forecasts. OBR website. Available from: https://obr.uk/brexit-and-our-forecasts/.

- OBR. 2019. Fiscal risks report - July 2019. OBR website. Available from: https://obr.uk/frr/fiscal-risks-report-july-2019/.

- O’Dwyer, M., 2019. Expertise in European economic governance: a feminist analysis. Journal of contemporary European research, 15 (2), 162–78.

- Peden, G.E., 2000. The treasury and British public policy, 1906-1959. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Pelkmans, J. 2012. Mutual Recognition: economic and regulatory logic in goods and services. Bruges European Economic Research Paper 24, June. Available from: http://aei.pitt.edu/58617/1/beer15_(24).pdf.

- Quiggin, J., 2010. Zombie economics. How dead ideas still walk among us. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Rosamond, B., 2020. European integration and the politics of economic ideas: economics, economists and market contestation in the Brexit debate. Journal of common market studies, 58 (5), 1085–106.

- Sampson, T., et al. 2016. Economists for Brexit: a critique. LSE website. Available from: https://cep.lse.ac.uk/pubs/download/brexit06.pdf.

- Siles-Brügge, G., 2019. Bound by gravity or living in a “post geography trading world”? Expert knowledge and affective spatial imaginaries in the construction of the UK’s post- Brexit trade policy. New political economy, 24 (3), 422–39.

- Tetlow, G., and Stojanovic, A. 2018. Understanding the economic impact of Brexit. Institute for Government, 2–76.

- Van Reenan, J., et al. 2016. How “Economists for Brexit” manage to defy the laws of gravity. VoxEU/CEPR. Available from: https://cepr.org/voxeu/columns/how-economists-brexit-manage-defy-laws-gravity.

- Vogel, S., 1996. Freer markets, more rules? Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Watson, M., 2014. Uneconomic economics and the crisis of the model world. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Winters, A. 2017. Will Eliminating UK Tariffs Boost UK GDP by 4 Percent? Even “Economists for Free Trade” Don't Believe It!. Blog post, UK Trade Policy Observatory, 19 April. Available from: https://blogs.sussex.ac.uk/uktpo/2017/04/19/will-eliminating-uk-tariffs-boost-uk-gdp-by-4-percent/#_ftn2.

- Winters, A. 2020. Brexit and covid: experts – who needs ‘em?’ UK in a Changing Europe. Available from: https://ukandeu.ac.uk/long-read/brexit-and-covid-experts-who-needs-em/.

- Wren-Lewis, S., 2018. The lies we were told. politics, economics, austerity and Brexit. Bristol: Bristol University Press.

- Wren-Lewis, S. 2019. Brexiters are stopping Brexit because they need to believe in the fantasy of Global Britain. Blog post, mainly macro, 19 March. Available at Available from: https://mainlymacro.blogspot.com/2019/03/brexiters-are-stopping-brexit-because.html (accessed 19 March 2019).