ABSTRACT

This article is concerned with the historical evolution of the mining industry in Canada since 1859. The focus is directed on changes that occurred in the industry and allows for the identification of four distinct mining regimes. These regimes are defined using the Regulation Theory, which connects conditions of production, technical progress, financial structures, and social relations. The identification of regimes gives a portrait of continuity and change in the industry. Continuity is present in the active role of the state, the legal framework based on Free Mining Principle and persistent speculation in the industry. Change is illustrated in price cycle, labour share and technological innovation. Interestingly, through time, price cycles have very different outcomes in financial and real economic terms. The most recent upswing in the late 1990s resulted in a punctual increase of financial assets but no significant increase in employment. Through this discussion, it becomes evident that the mechanisms underlying continuity and change have implications on the nature of state intervention and on the distribution of power between the corporate and regional actors like the workers and indigenous communities.

Introduction

Across the world, mining economies are both fundamentally localised at mineral deposit sites and remarkably global with price setting international markets. Local and global levels operate with different internal logics. Globally, the prices of mineral fluctuate greatly driven by changes in demand such as Second World War or Chinese development. Locally, mining regions are often mono-industrial with few other drivers of local labour markets and industrial activities. Thus, global mineral prices are unstable whereas local mining communities are highly dependent on the industry.

This puzzling relation calls for a simultaneous analysis of the financial and real economic spheres. This article provides such analysis for Canada. Regarding the financial sphere, I explore the historical importance of price cycles, capital flows and international trade notably foreign investments in Canada. I then analyse how this financial sphere intrinsically connects to real economic indicators such as the labour share, corporatist arrangements and state intervention.

I introduce a novel periodisation of the Canadian mining industry from the start of mineral extraction at scale until present times. Based on the regime concept from Regulation Theory, I identify four distinct regimes since 1859. Five institutional forms characterise regimes according to Boyer (Citation1986): wage relation, international economic relation, state intervention, monetary regime and forms of competition. I explore how these institutional forms shape continuity and change in the Canadian mining industry.

I argue that the diverse institutional forms from the regulation theory enables a fuller analysis of the Canadian mining industry. I complement the extensive political economy literature on natural resources in Canada (Innis Citation1930, Watkins Citation1963) and provide the longest evidence-based periodisation of the industry. I uncover how the mining sector has been shaped by the primacy of mining companies’ rights to extract and by high speculation. I also point to the failure of a mining-based state-led development strategy and constant need for re-legitimisation in the industry. The institutional lock-in, the falling labour share and the high financialization of the industry provide analytical lenses for further critical analysis of the emerging sustainable mining discourse. These elements are identified through an extensive empirically survey of the industry where both qualitative archives and quantitative data are used to depict the core historical trends and mechanisms within the mining. The proposed methodology illustrates the relevance of the Regulation Theory as a tool for economic history analysis of industries. It also provides a guide on how to operationalise the theory into observable variables.

The paper is structured as follows: the first section reviews the wealth of knowledge on the political economy of natural resources in Canada. Second, I define the regime concept and my methodology. Third, I examine the four Canadian mining regimes by analysing each in detail. Finally, I highlight the main implications of the historical changes and avenues for further research.

Literature review

The literature on natural resources is characterised by an abundance of theories. Theories focused on extractivism highlight the unequal power relation existing between resource-rich regions and countries or regions that finance, transform and use the resources (Gudynas Citation2019). Core–periphery relationships are observed in Canada between regions and at the global scale notably between the financial political nexus of Toronto and Ottawa and the northern resources regions and between Canada and Latin America and African countries where Canadian diplomacy and private interest operates (Deneault and Sacher Citation2012). Many authors have identified and the define extractivism in relation to the economic relation connecting Latin American to developed countries (Frank Citation1966 Citation1966). Gudynas (Citation2019) defines extractivism as a volatile development model prioritising natural resources extraction and export over the interest of local communities and the environment.

The resource curse consists of another important theoretical stream. It is based on long-run empirics showing that resource-rich regions or countries tend to underperform economically. Causal explanations include rent-seeking behaviours, corruption, and lack of economic diversification (Auty Citation1993, Sachs and Warner Citation1995).

Few historical reviews highlight periods and turning points in Canadian mining. Focused on Quebec, Vallieres (Citation2012) argues that technological advancement and the development of knowledge drive changes in the provincial mining sector with support by government subsidies and services throughout its development. These advancements move resource exploitation further north. Empirics on mineral production show support for a similar pattern occurring throughout the country (Cranstone Citation2002, Brandley and Sharpe Citation2009). Gendron and Sanders (Citation2019) identify a period of resource nationalism in the mid-twentieth century, concentrated in energy-generating natural resources such as hydropower.

Interested in the institutional, political and economic aspect of resource economies, the staple thesis developed by Harold Innis (Citation1930) and later theorised by Watkins (Citation1963), Drache (Citation1982) and Neill (Citation1972) foregrounds many analyses of Canadian economy. The thesis defines institutions and the natural resource economy as intertwined and identify an over-specialisation in resource extraction in Canada with a systematic disinvestment from other domestic industries. Resource regimes entail ‘a set of stable institutions at the sectoral level, which regulates the main parameters of the construction of public policies (relations between the State and social actors, ideas and rules) with regards to the exploitation of a particular resource’ (free translation from Fournis and Fortin Citation2015, p. 3). The staple thesis proposes stages of development: (1) frontier staple state seeing economies emerge based on resource extraction followed by a rapidly (2) expanding staple state (3) a subsequent mature staple state sees growth rates slow and a subsequent disequilibrium leads to a (4) new-staple state, with a transition toward new resource activities (Howlett and Brownsey Citation2008). For Canada, the historiography of staple stages varies according to the resources, notably mining, forestry and hydroelectric (Dumarcher and Fournis Citation2018).

Hutton (Citation1994) proposes an alternative fourth stage, the post-staples; theorising industrial diversification as the ultimate phase of development, notably with the service sector and a marginalisation of resource abundant territories. In 1994, he observed the province of British Columbia at a crossroad between a mature export-led staple and a post-staples economy (Hutton Citation1994). Others debate this occurrence and criticised the linearity of the phases in the staple thesis (Fournis and Fortin Citation2015) and documents a renewed resource-dependence in Canada (Stanford Citation2008). Indeed, the oil and gas boom at the turn of the century renewed Canada's dependence on natural resources after a period of diversification into manufacturing. Scholars (Stanford Citation2008, Haley Citation2011, Fast Citation2014) qualify this as the staple trap or carbon trap.

Analytical framework and methodology

According to the Regulation Theory, the concept of regime works as a tool to map context-specific and historically-grounded dialectical configuration of capitalist economies and comprehend their phases of stability and crisis. Specific configuration of production conditions, technical progress, distribution of profit and social composition of aggregate demand characterise regimes (Boyer Citation1986, Jessop Citation1997).

Following Boyer (Citation1986), five institutional forms define regimes:

Forms of competition concern the competitive systems shaping relations between companies linked to market structure and profit margins. They are influenced by technological and organisational determinants of production processes (Petit and Tahar Citation1985). For mining, this entails technological improvements, capacity to discover new deposits, regulation of extraction and concentration of production.

Monetary regime refers to changes in financial innovations, stability of price and financial channels (money, banking and credit systems) shaped by monetary policies, international monetary arrangements, and monetary circuits (Hein et al. Citation2014, Guttmann Citation2022). For mining, speculation, international capital flows and mineral price fluctuations determine monetary regimes.

State interventions point to economic policies linked to social welfare and redistribution and to macroeconomic stability. Intrinsically linked to other forms, the state functions as a transversal component (Becker Citation2002). In Canada, the state actively supports mining companies through provision of infrastructures and services and via legal and fiscal incentives (Handal Citation2010, Vallieres Citation2012).

Wage (or capital-labour) relation refers to the determinants of labour conditions (wage, recruitment, organisation of work, unionisation, services and benefits) (Boyer Citation1986). For mining, it entails unionisation, labour market tightness, health and safety and labour-substituting technology.

International economic relations highlight (inter)national connections with global-level dynamics. It connects to export of raw minerals and ownership of mineral companies.

For each regime, one institutional form dominates; other forms consolidate or align to stabilise the regime. This hierarchy of institutional forms brings stability to social relations that enable economic activities (Guttmann Citation2022). Inherent contradictions of social groups’ conflicting claims drive crises, which can stabilise over a limited period (Becker et al. Citation2010, Hein et al. Citation2014). As such, regimes can be understood as periods of stability intertwined by crisis.

As such, the Regulation Theory facilitates in-depth analyses of capitalist development. The concept of regime generally describes macroeconomic phenomena. However, it has been applied to productive processes (Becker Citation2002), mesoeconomic level (du Tertre Citation2002, Lamarche et al. Citation2015), industry-specific analysis (metallurgy by Durand Citation2004) and industrial policy in different phases of regionalism (Eder Citation2022). Existing scholarship applies Regulation Theory to study the Canadian economy (Jenson Citation1989, Boismenu et al. Citation1995, Jaeger and Leubolt Citation2014, Klassen Citation2023) or the role of commodities in shaping growth regime (Jaeger and Leubolt Citation2014, Schedelik et al. Citation2023); my study is the first to combine both. Schedelik et al. (Citation2023) propose commodity-based export-led growth regime under which the volatility and cyclicity of commodity prices generate a crisis tendency in resource-dependent nations identifying a financial-commodity nexus as a source of crisis, capital flows and exchange rate fluctuations. Boismenu et al. (Citation1995) formalise the regimes of change in Canada fordism through cointegration analysis and simultaneous equation model. Jenson (Citation1989) defines the specificities of Canadian fordism, qualified of permeable fordism in reference to its dependence on exogenous effects and its institutions defined by federalism.

The regime concept allows for a long-term periodisation of the industry. I operationalise it through a four-step methodology. First, I identify proxy variables for the institutional forms by exploring variables within regulationist literature (Stockhammer Citation2008, Guttmann Citation2022) and assessing their relevance in the industry's history. I select a limited number of observable variables to make the analysis pragmatically feasible. presents the resulting three to five core variables associated with each institutional form.

Table 1. Variables representing the five institutional forms.

Second, I collect and compile quantitative and qualitative historical data to measure these variables (listed in Supplementary Material). Longitudinal quantitative evidence captures trends; qualitative historical accounts capture contextual and relational information. I rely on multiple datasets to cover the full period.

Third, I identify trend changes of which I present the most significant in this article. The in-depth investigation of sources from Step 2 identifies historical changes and ensured their concordance among the different variables. This drafts the preliminary definition of regimes and underlying structural transformations.

Fourth, I cross-validate the significance of these regimes with a review of the academic literature on Canadian natural resources to confirm changes in the institutional forms and temporality of regimes. This also enables me to identify mechanisms leading to regime shifts and the hierarchy of institutional forms.

Four mining regimes of Canada

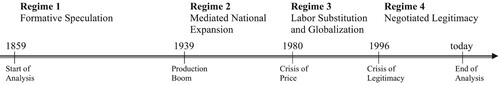

This section outlines the four mining regimes and their core characteristics. This paper focuses on the main institutional form of each regime. The exact border dates remain debatable, but the institutional forms define their nature and map their internal logic. Regimes differ in timespans () reflecting changing velocity over time. This result aligns with Becker et al. (Citation2010) that financialised regimes are crisis prone and with Bowman (Citation2018) that financialisation exacerbates the cyclical volatility of extractive industries.

The analysis starts in 1859 with the first appearance of the Free Mining Principle in the Canadian legal system. Lobbied for by American interest, this establishes a legal framework to the development of the industry in Canada. Marking the regime border at 1859 embodies the main institutional form of the period: international economic relations. The law gives primacy to (foreign) companies and prospectors by guaranteeing extraction rights and still shape contemporary Canadian mining. Regime 1 ends at the start of WWII in 1939, with an important reconfiguration of institutional form.

Alongside rising demand for minerals associated with the war, a new form of competition inaugurates Regime 2. Access to novel technologies positions some producers as important industrialists. Production concentrates supported by international demand and state support. Herein, Canada bases its development policy on resource extraction mainly mining and forestry.

A decline in the industry's employment beginning in 1980 signals the end of mining as a national development strategy. Despite profitable production, mining employment shrunk. Here, a new wage relation determines Regime 3 as the industry cut costs through labour substitution. Alongside the rise of indigenous and environmental conflicts, the change in wage relation weakens social acceptance of mining in Canada. This changed the belief that mining-based development is desirable and that it benefits workers.

Regime 4 starts in 1996 with the upward trend in mineral prices. The core institutional form is monetary regime as price upswing the high financial stakes of new mining project will be structuring elements to the corporate discourse, the strengthening of a new corporate responsibility discourse and the relation to labour. No precise date is selected for the end of the last regime as historical distance is needed to determine the end border and some of its features are still prevalent today like the sustainable mining discourse.

sums key characteristics of each regime, to be detailed in the subsequent sections.

Table 2. Characteristics of the four Canadian mining regimes.

First regime. Formative speculation (1859–1939)

Regime 1 entails the establishment of legal and governmental institutions to accompany the establishment of the mining industry. The large inflow of US workers and speculators around the Gold Rushes creates a need to regulate mining activities. Two core institutional features influence the trajectories of the subsequent mining regimes. First, the Free Mining Principle gives primacy to companies through far-reaching extractive rights. Second, the prevalence of speculative activities features early financialisation of the industry.

Emerging industry and the Free Mining Principle

Mineral production before the mid-nineteenth century is neither extensive nor resulting from active search. This changes in the 1870s (Cranstone Citation2002). Yet, production remains artisanal with low-technological intensity and scarce knowledge, notably on mineral deposit locations. Although few companies and individuals comprise the industry, company-towns emerge (1860–90) such as Elliot Lake, Thetford Mines and Asbestos (Robson Citation1992, Vallieres Citation2012).

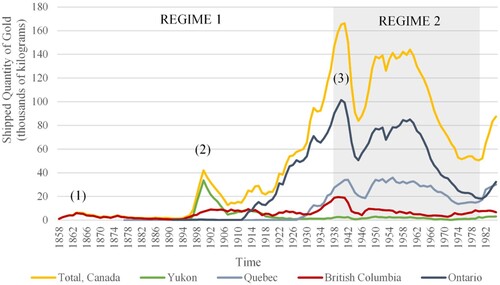

Within this landscape, the new ‘prospector-entrepreneur-speculator’ actor emerges (Vallieres Citation2012), especially in surface mining. An inflow of workers, companies and capital from the Californian Gold Rush (1848–52) propel gold mining (Barton Citation1993), one of the few minerals directed for export during a period when mineral production catered toward domestic consumption for the making of goods, roads and buildings. illustrates the booms and their location in Canada.

Figure 2. Booms in Gold Production in Canada and Selected Provinces, 1858–1985. Source: Author’s contribution from Natural Resources Canada (Citation2021).

Note: Three gold booms occur during the regime period: (1) in British Columbia, 1858–1862 (Cariboo and Frayser Canyon); (2) Klondike Gold Rush, Yukon, 1896–1899 and (3) Quebec and Northern Ontario, from the 1920s. The quantity shipped uses a proxy, as the quasi-entirety of production was exported and followed the same cycles.

The gold rushes raise concerns around the rules structuring economic activities and force the Canadian authorities to design a framework to regulate economic activities especially regarding access and ownership to deposits and increasing need for public services and royalties (Vallieres Citation2012). The legal framework based on the Free Mining Principle first appears in the Gold Fields Act (1859) in British Columbia and later adopted throughout the country and applied progressively to a variety of minerals notably asbestos and phosphate (Laforce et al. Citation2009).

Its adoption is not inevitable but rather imposed by US actors (Barton Citation1993). In Quebec's Beauce region, for instance, the initial legal framework issued in the spring 1864 faced resistance by Californian investors; a revised framework following the Free Mining Principle was adopted in June 1864 (Barton Citation1993). At a time of limited institutional capacity in Canada, the framework also limited blatant abuse and secured capital inflow from the US (Lapointe Citation2012, Vallieres Citation2012).

Originating in medieval Europe (Barton Citation1993), the Free Mining Principle provides rights for companies to: i. freely access land where resources are under public ownership, ii. resources ownership via direct purchase of mining titles and iii. exploit discovered mineral resources. It implies strong guarantees for mining companies to own and exploit natural resources and limits legal governmental capacities to intervene in mine acquisition and exploitation.

The government projects a laissez-faire attitude supporting the emergence of the mining industry and the inflow of foreign capital in this developing industry. Alongside French and British, US companies exert significant control on Canadian development. As such, the industry is from the start structured by foreign capital interest, representing a core–periphery relation. The governments not only accommodate the demands of actors in the industry; they create agencies to provide services including refined mapping of economic geology, collection of mining statistics and access to experts through partnership with governmental experts and academics. In contrast, little to no service exists to guarantee workers’ rights.

Speculation

In the 1930s, Toronto becomes the central stage for speculative activities with the listing and valuing of companies on the Toronto Stock Exchange (TSX) and later, Toronto Venture Exchange (TSX-V). Speculative activities are centred around industries of railway, forestry and mining. In 1931, the extent of these activities forces the Ontarian authorities to intervene creating the Ontario Securities Commission (Deneault and Sacher Citation2012). However, in 1939, industrial actors oppose controls based on their need for liquidity and the Commission relaxes regulations. Deneault and Sacher (Citation2012) talk about a myth of autoregulation assumed by authorities. They also identify that throughout the last century, this pattern repeats itself for instance, forcing the relocalisation of speculative activities in Calgary or by the loosening of rules shortly after their creation.

The lack of controls on speculative activities illuminates Canada's dependent position regarding foreign investments and capital inflow. Market intervention was essential to restore confidence and market a certain degree of credibility in Toronto. Furthermore, it shows a primacy of financial consideration over real employment and productivity objectives. Indeed, many projects never deliver the promised employment or profit.

In sum, these two legacies – the Free Mining Principle and the speculative nature of the industry – favour international actors and will remain key features throughout the regimes.

Second regime. Configuration of national expansion (1939–80)

Under Regime 2, the Canadian mining industry experiences its largest growth rate. The demand for minerals increases in the post-war period and mining will become a pillar of Canadian national development plan. Public investments in infrastructures notably railways and scientific services catalyse the industry's expansion. This national development plan entails an intrinsic contradiction that will raise criticism at the end of the regime. The contradiction arises from the fact that most of the companies operating in Canada are American or foreign owned. Many workers and progressive political parties demand Canadian ownership with hopes that local communities associated to the mining activities receive greater benefit from Canadian companies and that more profit remains in Canada to benefit the national economy. This sentiment opens a window of opportunity for nationalisation. While nationalisation is adopted in other natural resource sectors, the decline in mineral prices in the early 1980s halts this project for the mining industry.

The expansion of the mining sector

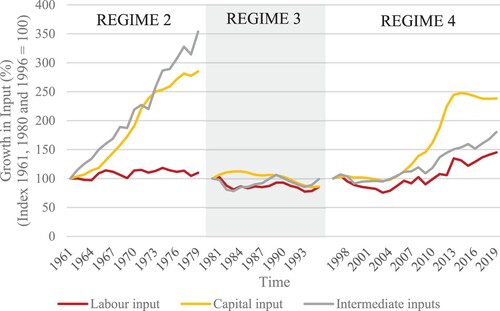

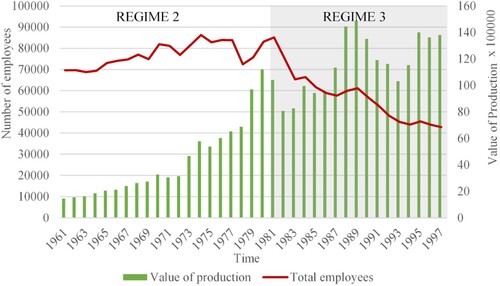

Regime 2 illustrates staple theory's phase of expansion: exploitation of the resource rises and an export-led development model ensues. shows a massive expansion of industries particularly impressive compared to the subsequent regime. shows the major growth in material, capital and intermediate inputs.

Figure 3. Growth and Composition of Inputs in the Industry of Mining, Canada, 1961–2019. Source: Author’s contribution from Statistics Canada (Citation2024).

Technological improvements allow access to and identification of more deposits. The resource frontier expands with production moving northward, for example in Sudbury, Ontario and Abitibi, Quebec. Technologies include the sensitive scintillometer allowing discovery of uranium and the airborne magnetometer facilitating mineral detection (Cranstone Citation2002). These advances in the 1950s mark a turning point in the maturation of the industry by upgrading exploration that increases discovery of deposits in the following decennia (Cranstone Citation2002).

Some companies owning the new technologies gain preferential access to the market and in the production of certain mineral types. New historical data (Dallaire-Fortier Citation2024) shows the important market share of Noranda, Hudson Bay Mining and Cominco Ltd. Moreover, senior companies like INCO and Falconbridge bolster their position on the market through financial means to prospect and identify new deposits. It leads to a significantly concentration of profit and market power in the hand of a few companies that will remain characteristic until today and intensify with mergers and acquisition after the 1980s (Dallaire-Fortier Citation2024).

Foreign capital, national strategy

The industry becomes politically more central in state development strategy. This occurs amidst many Western countries including the US valorising the role of the state via Keynesian ideas, the New Deal and other post-war government-led projects. For instance, Prime Minister Diefenbaker (1957–63) leads Road to Resources, a transportation infrastructure project facilitating mineral extraction in northern Canada (Isard Citation2010). Additionally, mining corporations receive large and multifaceted financial support (at federal and provincial levels) targeting productions, research and development, financial subsidies, and equity participation (Hutton Citation1994, Gendron and Sanders Citation2019).

The capital necessary for expansion mainly comes from across the border. In 1960, 47.4 percent of capital investments in Canada (all sectors confounded) originate from the US (Deneault and Sacher Citation2012). The same year, mining companies constitute 40 percent of the industrial category on the Toronto Stock Exchange and 76 percent of mining transactions made in Canada in 1962 are made in Toronto (Deneault and Sacher Citation2012).

Contradicting the idea that national resource-based development benefits everyone in the country, foreign ownership of most mines means that profits and minerals are exported to the US, with low value-added within Canadian borders. Many see this as paradoxical, arguing against a national development project depending on foreign capital. Sharing this sentiment, the labour force is sceptical that US companies will properly support them during the phasing down of mines (Keeling and Sandlos Citation2017).

Rising criticism

The Carter Report of 1962 produces the first critical analysis of the Quebecois economy's vulnerability to price fluctuation and external interests controlling the market. It also critiques the concentration of ownership in foreign interest and export-induced losses with low value-added transformation of resources. As such, raw-export structure diminishes economic potential. The report emphasises tension between dependence and support (financial incentives and publicly built infrastructure) showing that foreign companies benefit from governmental support in the province (Vallieres Citation2012). In 1972, the Gray Report (Citation1972) similarly highlights the large share of US-owned capital and companies operating in Canada. Academics such as Watkins (Citation1963) or Levitt (Citation1970) similarly critique the dependence on foreign capital and structural underdevelopment in Canada implied by lack of diversification and transformation of natural resources.

The Carter report spurs policy recommendations for the mining sector and support for state intervention toward economic nationalism (Vallieres Citation2012). A ‘window of opportunity’ for another development process emerges. Indeed, the mid-twentieth century was a period of resource nationalism concentrated in energy, forestry and fisheries (Gendron and Sanders Citation2019). Yet while various groups support nationalising mining production, this does not become an alternative industrial model. Indeed, national ownership was rarer in the mining sector only exceptions being Eldorado Resource (uranium, 1943–88), Potash Corporation of Saskatchewan (1975–89) and Saskatchewan Mineral Inc (1947–88). Some initiatives for enterprises in exploration and exploitation during the 1960s and 1970s emerge but they concentrate in energy, forestry and fisheries. This is partially explained by declining prices of minerals in the 1980s.

In sum, during Regime 2, the prospect of mining as a vector of development for Canada sees rapid expansion as well as growing criticisms, which point to the paradox of basing national strategy on foreign interests.

Third regime. Globalisation and labour substitution (1980–96)

This regime shift begins with a decline in mineral commodity prices. In real economic terms, the labour force experiences the greater effect of this. Workers in the mining industry face both the closure of plants linked to the price contraction and the substitution of their work by new technologies. Following the second regime's shivering discourse on national development, the industry faces an important crisis of legitimacy. Environmental, civic and indigenous actors formulate strong critiques of the extractive process linked to environmental costs and scarce long-term benefits for local communities. Declining employment further decreases the legitimacy of the companies to operate and the value of production increases.

Price shock and capital flow

After increased production of iron ore, coal, copper, platinum and zinc in the 1960s, the position of the sector is the Canadian economy is challenged. The regime begins in 1981 with declining mineral prices severely pressuring the Canadian economy. To face the decline in price, mining companies undertake two distinct strategies: (1) relocate production and investment in the Global South and (2) cost reduction though the substitution of labour by technology. Many factors cumulate during Regime 3 to decrease mining employment in Canada: intertwined globalisation, price cycle, technology and labour substitution.

Given the underlying financial flow, the decline in price of minerals implies fewer foreign investments in Canada. However, Canadian mining companies increasingly invest abroad. Canadian foreign direct investment in the Americas (excluding USA and Mexico) grew six-fold in the decennia of 1990s, making it the largest investor in the region (Gordon and Webber Citation2008). In 1996, the stocks of foreign direct investment (FDI) owned by Canadian companies abroad surpass the FDI with foreign ownership in Canada. This also came with novel strategies from the Canadian multinational mining corporation in the region: massive expenses in exploration, tax evasion, and changes in legal practices leading to human rights abuses and environmental degradation (Deneault and Sacher Citation2012, Imai et al. Citation2017). Canadian direct investment in Latin America became one of the largest investors in the region and strategically gain control of some of the richest deposits (Gordon and Webber Citation2008).

New wage relation

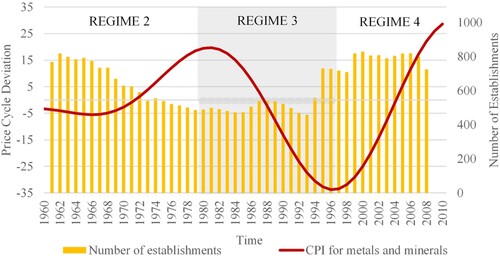

Following this turning point, a major wave of plants and mine closures occurs in the industry. The number of closures during 1990 nearly doubles that of openings (McAllister Citation2007). Beyond the trends illustrated in , most of the year's closures happen in mines employing large numbers of workers and one third in Northern Ontario (DEMR Citation1968). The greatest job losses occur at Denison Mines Limited and Rio Algom Ltd's uranium mining operations at Elliot Lake (2150 lost), Dofasco Inc's Adams and Sherman iron mines in Ontario (689 lost), and Brenda Mines Ltd. British Columbia copper mine (400 lost). Meanwhile, new operations tend to employ fewer people.

Figure 4. Commodity Price Cycle in Metals and other Minerals, 1960–2010. Source: Macdonald (Citation2017) and Statistics Canada (Citation2011).

Note: The value of production increases while the total employment decreases during the third regime.

Production becomes increasingly technologically intensive changing the demand for labour. This emerging trend represents a new technical division of labour wherein technology plays a role in the decline of wages (not only labour substitution) (Clement Citation1981). illustrates the steep and cumulative impact on labour where the value of production and employment numbers follow opposing trends. This cumulates in a dissolution of the labour-capital accord that continues through Regime 4.

Figure 5. Value of Production and Labour Force of Canadian Mines, 1961–2000. Source: Author’s contribution Statistics Canada (Citation2006).

Numerous labour conflicts occur between 1966 and 1987. Yet, as the number of closures increases and the labour force shrinks, workers’ capacity to mobilise declines (Vallieres Citation2012). Workers claims were constrained as they felt powerlessness in face of the global price downswing, see for example the case of the copper-ore mine Britannia Beach, British Columbia (Rollwagen Citation2007). From 1980 to 1998, the largest unionisation decline across Canadian sectors occurs in forestry and mining by 19.7 percent (Morissette et al. Citation2005).

A changing national strategy and loss in legitimacy

The decline in mineral price and employment restructures Canadian economy. Expansion of manufacturing notably the automotive industry leads to a post-staple economy (Howlett and Brownsey Citation2008) wherein the national economy depends less on natural resource extraction for employment and growth. The national economy is less vulnerable to fluctuating resource prices and develops its knowledge economy and urban core (Hutton Citation1994). The division of responsibility in governance of natural resources in Canada also changes in 1982. Whereas the Constitution Act of 1867 give exclusive authority to the federal government with respect to mining, amendments in 1982 (section 92A) transfer responsibilities to the provinces and territories giving them power to levy taxes and royalties.

In addition to these industrial and institutional changes, rising mobilisation against mining projects affects the legitimacy of mining companies. During this period, indigenous struggles intensify over the ownership of their territories. Successes include cases of the Taku River Tlingit First Nation, Haida Nation and Mikisew Cree First Nation at the supreme court of Canada (Savard Citation2016). The struggles seek self-government (e.g. Alberta Federation of Metis Settlements Associations in 1990), actively mobilise around social justice issues (e.g. Manitoba Metis Federation in the 1970s) and directly oppose the industry (e.g. Matawa First Nations against pollution from the Eagle's Nest Nickel Mine, Victor Diamond Mine and Musslewhite Gold Mine in Ontario and Yellowknives Dene First Nation against arsenic contamination from Giant Mine in Northwest Territories).

Diverse indigenous nations become essential actors in the political arena around extraction in Canada. Indeed, risks of indigenous opposition delaying and preventing projects become palpable for mining companies and the government. In some case, it leads to new governance structures with indigenous nations such as Societe de developpement de la Baie-James initially connected to hydroelectricity; the Corporation for the Mitigation of Mackenzie Gas Project Impacts linked to a natural gas pipeline and the Nechako-Kitamaat Development Fund Society linked to an aluminium smelter and hydroelectric powerhouse. As indigenous nations, civil society and environmental organisations exercise increased pressure, they challenge the legitimacy of the mining industry. The next regime details how relegitimisation operates for companies to benefit from rising costs.

Fourth regime. Negotiated legitimacy for extraction (1996–)

Regime 4 is intrinsically linked to expansion of the mining sector going hand-to-hand with governmental support and roots its legitimacy in a sustainable mining discourse. A price upswing for minerals, oil and gas entails changes in the national regime of Canada. Capital inflow and its induced sectoral restructuring renew Canada's dependence on natural resources as a primary mode of accumulation and the state (federal and provincial) facilitates the rise of the mining industry with extensive and pivotal support through tax and subsidies. These companies are risk averse as mining development in the twenty-first century is a capital-intensive activity with high sunk costs at the start of projects. Government invests taxpayers’ money in the industry while the labour share shrinks dramatically; total sector employees compose a negligible share of Canadian labour force (around 1 percent). After the slowdown in price in mid-2000s, the presence of sustainable mining discourse and the state-corporate relation are sustained.

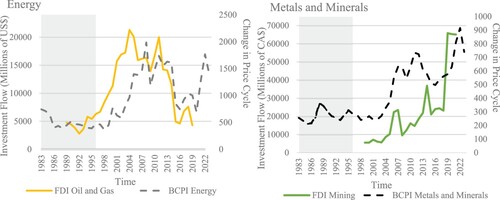

Renewed expansion

Regime 4 begins with a pendulum swing: a favourable price increase starts in 1996. The rise in price of mineral is largely attributed to China, considered as the core driver of the acceleration of the increase in global commodity prices since the late twentieth century (Garnaut Citation2012, Stuermer Citation2018). The subsequent drop in demand and investment in 2014 will lead to a sharp decrease in extractive capital toward Africa and Latin America, ensuing in crises notably in Brazil (Gudynas Citation2019). These have implications many companies in these regions are Canadian, but also nationally. illustrates the price increase after 1997 and the inflow of US FDI to Canadian energy and metallic mineral sectors. The Canadian mining industry renews its national reliance on foreign ownership. In mining and quarrying, foreign ownership moves from 11.2 in 1999 to 32.8 percent in 2010, whereas the total for all industries remains relatively constant during that period (around 20 percent) (Fast Citation2014). Foreign asset owners hold the most profitable mining operations. Ownership of revenues grows sharply from 16.6 in 1999 to 64.9 percent in 2010 (Fast Citation2014).

Figure 6. Capital Inflow from the United States in the Sectors of Energy and Mineral, 1972–2022. Source: Author’s contribution from Bank of Canada (Citation2024), Statistics Canada (Citation2023) and U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis (Citation2024).

Note: BCIP refers to the Annual Bank of Canada commodity price index for Energy and Metals and Minerals, respectively. The flow of direct investment from the United States are larger and increase before in Energy than Minerals.

Canada experiences a major boom in its oil and gas sector in Alberta returning to economic dependency on natural resources. Stanford (Citation2008, p. 7) point to ‘the laissez-faire stance of neoliberal economic policy in Canada, the reinforcing role of free trade agreements (…) and the daunting political influence of Canadian resource elites’. In 1994, the NAFTA assigns Canada as an energy supplier. This prompts arguments for the return of the stable trap or structural underdevelopment of the Canadian economy (Stanford Citation2008, Haley Citation2011, Fast Citation2014). This structural change induced mainly by the oil and gas industry echoes into regulatory changes and new attitudes from the government that impact the mining industry. It induces changes in the structural composition of the country: a classic case of Dutch Disease, where real appreciation of the currency due to capital inflows and commodity revenues increases the prices of nontradable goods and redirects capital and labour into the mining sector. The Canadian dollar appreciates by 60 percent between 2002 and 2008 relative to the US dollar. As a result of changing terms of trade, manufacturing decreases from 23 to 13 percent, 1997 to 2021 in the provincial economies of Quebec and Ontario. While the prices of energy, metals and minerals will drop again after 2008 (see ), the staple-dependent institutions will persist in time, notably the state-corporation relation.

State-corporate relation

The state makes large investments, subsidies and other supports to mining companies operating in Canada. Handal (Citation2010) notes a significant increase in public investments and tax relief to the mining industry with programmes like the ‘super flow through’ at provincial levels financing tax credit for investors. Additionally, the 1990–2000s features declining share of corporate income tax and corporate profit and differential tax treatment of extractive sector (Fast Citation2014).

At the provincial level, Newfoundland, Saskatchewan and Alberta exemplify the new attitude. Since the commodity boom in 1998 until it plateaus in 2008, corporations in these three extractive provinces pay on average just over half as much tax as the national average rate of taxes paid on profits of 9.9 percent (Fast Citation2014). The divergence between statutory provincial corporate tax rates and the actual amount that corporations pay in the extractive provinces is largely attributable to the differential tax treatment afforded to the extractive sectors (Handal Citation2010, Deneault and Sacher Citation2012). As government support increases mineral production profitability, socialised risks rest on public money and mining companies reap the benefits.

Sustainable mining discourse

A narrative with concepts of sustainable mining and multi-stakeholders’ agreements emerges to legitimise the mining companies and guarantee that they can profit from the upswing in mineral prices starting in 1996. Federal and provincial governments actively shape a new discourse on corporate responsibility, one of the first examples being a 1995 Natural Resource Canada report (Cameron and Levitan Citation2014). Government initiatives follow CORE and Environmental Mining Council (both in British Columbia) as do nongovernmental initiatives like Whitehorse Mining Initiative in 1993 and MiningWatch Canada in 1992 (McAllister Citation2007).

The creation of Impact and Benefit Agreements (IBAs) becomes a key component of mining discourse and project implementation. Yet critiques suggest that adoption of IBAs merely reduce risks of public opposition suggesting IBAs fail to make fundamental changes. Principle of Free Mining still characterises contemporary Canadian regimes and prevents state and indigenous nations from blocking or redefining projects (Campbell Citation2004, Lapointe Citation2012). Even in cases of environmental risks, the Free Mining principle stipulates the government pays a fine to mining companies if a project does not take place. Additionally, whereas some multi-shareholder agreements include quotas for indigenous hiring, most indigenous workforce receive lower-skilled positions (Cameron and Levitan Citation2014).

While IBAs provide indigenous and local communities with a ‘right to negotiate’, they neglect power inequalities structuring capital-labour and local population relations (Horowitz et al. Citation2018). Local stakeholders lack veto rights, power and information and creation of agreements function under strict timelines (Horowitz et al. Citation2018).

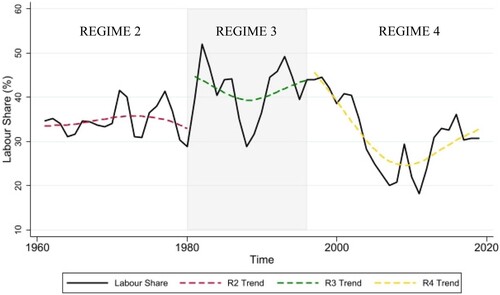

Distribution of profits

A fuller picture of Regime 4 emerges around profit distributions. illustrates a historical decline of labour share (the part of mining income allocated to wages). Between 2001 and 2008, the labour share drops from 41.52 to 20.97 percent (Statistics Canada Citation2024). These conclusions stand distinct from the regulationist assessment of the Fordist era, as I show that wage relation in the mining industry did not benefit from favourable economic conditions. This highlights the weak power of labour induced by their substitution by technologies in the Regime 3. shows a large drop in the labour share until the early 200s followed by a moderate increase until 2019.

Figure 7. Changes in the Labour Share in the Mining Industry, Canada, 1961–2019. Source: Author’s calculation from Statistics Canada (Citation2024).

Note: Industry based on North American Industry Classification System (NAICS). Trends calculated using Christiano and Fitzgerald (Citation2003) time series.

In sum, the resource boom at the turn of the century fails to result in a positive change of real economic conditions like increased employment. Nonetheless, it punctually increases corporate rent and profit (Stanford Citation2008). While driven by the oil boom in the province of Alberta, the trend holds for mining. As indicates, labour share sharply decreases in the mining industry. While new tax structure favouring mining companies, increased mineral prices are not accompanied by a fair distribution of profit nor an increase in employment.

Conclusion

The natural resource sector has shaped and reshaped Canada's political economy since the nation's constitution. A few highlights stand out. First, the interrelation between capital (flow and price cycle), labour and structural composition facilitates understanding of the different regimes of mining in Canada. This relation is illustrated by the pendulum swing in sectoral composition and presence of foreign capital in Canada. The presence of this interrelation supports the relevance of the Regulation Theory's regime concept to appreciate historical changes at the sectoral level. Second, the Free Mining Principle and speculative activities of the first regime create path dependence since the mid-nineteenth century. Financial constraints (for example, firm obligations toward shareholders) and the legal framework prioritise companies under the Free Mining Principle limiting advancement of environmental and indigenous interests. Third, while the mid-twentieth century mining-led development strategy comprises contradictions that make it unstable, it opens a window of opportunity for reports and critiques that encourage an alternative development model. Fourth, considering the reconfiguration of the capital-labour relation during the downturn from 1980 to 1996, it stands out that even during the upswing in mineral production, labour scarcely benefited from the activities of the industry. Finally, the revival of the industry at the turn of the twenty-first century requires a redefinition of legitimacy. Currently, financialisation makes the industry risk averse and furthers the importance of social acceptance and governmental support.

In the context of the search for critical minerals, the identification of mining regimes holds potential to enable better understanding the historical roots of the Canadian industry. Through the ages, mining communities have changed significantly from improvised mining shacks to centralised company towns and today as a negotiation between indigenous land and long-distance commuting workers. Fiscal incentives, legal framework and monetary flows emerge as essential to understanding the potential impact of mine closures on local communities. A classical definition of deindustrialisation by Bluestone and Harrison (Citation1982) focuses on the role of investment and disinvestment in a locality, a feature that seems intrinsic to the industry. This movement of capital holds major implications for the livelihood of the inhabitants of mining towns and must be defined historically. My long-term perspective underlines multiple dimensions for livelihoods: industrial diversification that grows other sectors locally, institutional investments support redistribution, environmental protection, local participation and investments in infrastructures. These concrete components may provide building stones for a genuine conversation on sustainable mining.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (31.4 KB)Acknowledgements

I am grateful for the insightful comments offered by Julia Eder and Robert Guttmann who have guided me operationalising the Regulation Theory and Andreas Dugstad Sanders whose historical expertise greatly improved the manuscript; I also wish to thank them for their kindness.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Clara Dallaire-Fortier

Clara Dallaire-Fortier is a doctoral researcher at the Department of Economic History, Lund University. She conducted research stays at LSE, University of Lausanne and University of Massachusetts, Amherst. Her research is at the intersection of political economy and ecological economics with an interest in regional transition and the mineral sector. She has an extensive experience working in NGOs and research institutes and has been active in creating open sources teaching material inspired from economic pluralism.

References

- Auty, R.M., 1993. Sustaining development in mineral economies: The resource curse thesis. Routledge.

- Bank of Canada. 2024. Commodity price index. https://www.bankofcanada.ca/rates/price-indexes/bcpi/#data.

- Barton, B.J., 1993. Canadian law of mining. Toronto: LexisNexis.

- Becker, J., 2002. Akkumulation, regulation, territorium. Zur kritischen Rekonstruktion der französischen Regulationstheorie. Marburg: Metropolis.

- Becker, J., et al., 2010. Peripheral financialization and vulnerability to crisis: a regulationist perspective. Competition & Change, 14 (3-4), 225–47.

- Bluestone, B. and Harrison, B., 1982. Deindustrialization of America. New York: Basic Books.

- Boismenu, G., Loranger, J.-G., and Gravel, N., 1995. Régime d’accumulation et régulation fordiste: Estimation d’un modèle à équations simultanées. Revue Économique, 46 (4), 1121–43.

- Bowman, A., 2018. Financialization and the extractive industries: the case of South African platinum mining. Competition & Change, 22 (4), 388–412.

- Boyer, R., 1986. La Theorie de la regulation: une analyse critique. Paris: La Decouverte.

- Brandley, C., and Sharpe, A. 2009. A detailed analysis of the productivity performance of mining in Canada. Report no. 2009-7. Center for the Study of Living Standards.

- Cameron, E., and Levitan, T., 2014. Impact and benefit agreements and the neoliberalization of resource governance and Indigenous-state relations in Northern Canada. Studies in Political Economy, 93 (1), 25–52.

- Campbell, K., 2004. Undermining our future: how mining’s privileged access to land harms people and the environment. Vancouver: West Coast Environmental Law.

- Christiano, L.J., and Fitzgerald, T.J., 2003. The band pass filter. International Economic Review, 44, 435–65.

- Clement, W., 1981. Hard-rock mining: industrial relations and technological change. Toronto: McClelland Stewart.

- Cranstone, D.A. 2002. A history of mining and mineral exploration in Canada and outlook for the future. Report no. M37-51/2002E, Natural Resources Canada.

- Dallaire-Fortier, C, 2024. A comprehensive historical and geolocalized database of mining activities in Canada. Scientific Data, 11, 307. doi:10.1038/s41597-024-03116-3.

- Deneault, A., and Sacher, W., 2012. Paradis sous terre: Comment le Canada est devenu la plaque tournante de l’industrie miniere mondiale. Montreal: Ecosociete.

- Department of Energy, Mines and Resources (DEMR). 1968. Canadian Minerals Yearbook. Report, Mineral Resources Division, Department of Energy, Mines and Resources, Canada.

- Drache, D., 1982. Harold Innis and Canadian capitalist development. Canadian Journal of Political and Social Theory, 6 (1-2), 35–60.

- Dumarcher, A., and Fournis, Y., 2018. Canadian resource governance against territories: resource regimes and local conflicts in the Gulf of Saint Lawrence provinces. Policy Sciences, 51, 97–115.

- Durand, C., 2004. De la predation a la rente, emergence et stabilisation d’une oligarchie capitaliste dans la metallurgie russe (1991-2002). Geographie, Economie, Societe, 6, 23–42.

- du Tertre, C., 2002. Sector-based dimensions of regulation and the wage–labour nexus. In: R. Boyer, and Y Saillard, eds. Regulation theory: the state of the art. London and New York: Routledge, 204–13.

- Eder, J., 2022. Bringing industrial policy back into regionalism: Recent findings from Latin America, Eurasia, and Europe. Thesis (PhD). Johannes Kepler University, Austria.

- Fast, T., 2014. Stapled to the front door: Neoliberal extractivism in Canada. Studies in Political Economy, 94 (1), 31–60.

- Fournis, Y., and Fortin, M.J., 2015. Les regimes de ressources au Canada: Les trois crises de l’extractivisme. VertigO, 15 (2), 1–13.

- Frank, A.G., 1966. Capitalism and underdevelopment in Latin America: Historical studies of Chile and Brazil. :New York: Monthly Review Press.

- Garnaut, R., 2012. The contemporary China resources boom. Australian Journal of Agricultural and Resource Economics, 56 (2), 222–43.

- Gendron, R., and Sanders, A., 2019. Regulating natural resources in Canada: a brief historical survey. In: A. Sanders, P.R. Sandvik, and E. Storli, eds. The political economy of resource regulation: an international and comparative history, 1850–2015. UBC Press, 67–95.

- Gordon, T., and Webber, J.R., 2008. Imperialism and resistance: Canadian mining companies in Latin America. Third World Quarterly, 29 (1), 63–87.

- Gray, H., 1972. Foreign Direct Investment in Canada. Ottawa: Information Canada.

- Gudynas, E., ed., 2019. Extractivisms: politics, economy, and ecology. Halifax: Fernwood Publishing.

- Guttmann, R., 2022. Multi-polar capitalism: the end of the dollar standard. London: Palgrave Macmillan Cham.

- Haley, B., 2011. ‘From staples trap to carbon trap: Canada’s peculiar form of carbon lock-in. Studies in Political Economy, 88 (1), 97–132.

- Handal, L., 2010. Le soutien a l’industrie miniere: Quels benefices pour les contribuables? Montreal: Institut de recherche et d’informations socio-economiques, April.

- Hein, E., Dodig, N., and Budyldina, N., 2014. Financial, economic and social systems: French Regulation School, Social Structures of Accumulation and Post-Keynesian approaches compared. Institute for International Political Economy Working Paper, 34.

- Horowitz, L., et al., 2018. Indigenous peoples’ relationships to large-scale mining in post/colonial contexts: Toward multidisciplinary comparative perspectives. The Extractive Industries and Society, 5 (3), 404–14.

- Howlett, M., and Brownsey, K., 2008. Canada’s resource economy in transition: the past, present, and future of Canadian staples industries. Toronto: Emond Montgomery Publications Limited.

- Hutton, T.A., 1994. Visions of a ‘post-staples’ economy: structural change and adjustment issues in British Columbia. Vancouver: Centre for Human Settlements.

- Imai, S., Gardner, L., and Weinberger, S. 2017. The ‘Canada Brand’: violence and Canadian mining companies in Latin America. Osgoode Legal Studies Research Paper, 17/2017.

- Innis, H., 1930. The fur trade in Canada: an introduction to Canadian economic history. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- Isard, P., 2010. Northern vision: northern development during the Diefenbaker era. Thesis (PhD). University of Waterloo, Canada.

- Jaeger, J., and Leubolt, B., 2014. Rohstoffe und Entwicklungsstrategien in Lateinamerika. In: A. Nölke, S. Claar, and C May, eds. Die großen Schwellenlaender. Ursachen und Folgen ihres Aufstiegs in der Weltwirtschaft. Wiesbaden: Springer VS, 175–92.

- Jenson, J., 1989. “Different” but not “exceptional”: Canada’s permeable Fordism. Canadian Review of Sociology, 26 (1), 69–94.

- Jessop, B., 1997. Survey article: the regulation approach. Journal of Political Philosophy, 5, 287–326.

- Keeling, A., and Sandlos, J., 2017. Ghost towns and zombie mines: the historical dimensions of mine abandonment, reclamation and redevelopment in the Canadian North. In: S. Bocking, and B. Martin, eds. Ice blink: Navigating northern environmental history. Calgary: University of Calgary Press, 75–96.

- Klassen, J.T. 2023. From export boom to private debt bubble: a macroeconomic policy regime assessment of Canada’s shifting growth regime in the neoliberal era. Institute for International Political Economy Working Paper, 203(2023).

- Laforce, M., Lapointe, U., and Lebuis, V., 2009. Mining sector regulation in Quebec and Canada: Is a redefinition of asymmetrical relations possible? Studies in Political Economy, 84 (1), 47–78.

- Lamarche, T., et al., 2015. Les regulations mesoeconomiques: saisir la variete des espaces de regulation. La theorie de la regulation a l’epreuve des crises. Paris, Jun 2015, Paris, France, 1-23.

- Lapointe, U., 2012. L’heritage du principe de free mining au Quebec et au Canada. Recherches amerindiennes au Quebec, 40 (3), 9–25.

- Levitt, K., 1970. Silent surrender: the multinational corporation in Canada. Toronto: Macmillan.

- Macdonald, R. 2017. A long-run version of the Bank of Canada commodity price index, 1870 to 2015. Report no. 1F0019M 399, Statistics Canada.

- McAllister, M.L., 2007. Shifting foundations in a mature staples industry: a political economic history of Canadian mineral policy. Canadian Political Science Review, 1 (1), 73–90.

- Morissette, G., Schellenberg, G., and Johnson, A., 2005. Diverging trends in unionization. Perspectives on Labour and Income, 6 (4), 5–12.

- Natural Resources Canada. 2021. Production per commodity and province, 1850–2020 [data file].

- Neill, R., 1972. A new theory of value. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- Petit, P., and Tahar, G. 1985. Relation automatisation-emploi (la) effet productivite et effet qualite. CEPREMAP Working Papers, 8520.

- Robson, R., 1992. Building resource towns: government intervention in Ontario in the 1950s. In: R.M. Bray, and A Thomson, eds. At the end of the shift: mines and single-industry towns in Northern Ontario. Toronto: Dundurn Press, 97–119.

- Rollwagen, K., 2007. When ghosts hovered: community and crisis in a Company Town, Britannia Beach, British Columbia, 1957–1965. Urban History Review / Revue d’histoire urbaine, 35 (2), 25–36.

- Sachs, J.D., and Warner, A.M. 1995. Natural resource abundance and economic growth. NBER Working Paper No. 5398.

- Savard, J.F., 2016. Réformes de la politique autochtone au Canada : le jeu du blâme donne-t-il une cohérence au discours ? Gestion et Management Public, 4 (4), 33–52.

- Schedelik, M., et al., 2023. Dependency revisited: commodities, commodity-related capital flows and growth models in emerging economies. Journal of Economics and Economic Policies: Intervention, 20 (3), 515–538.

- Stanford, J., 2008. Staples, deindustrialization, and foreign investment: Canada’s economic journey back to the future. Studies in Political Economy, 82 (1), 7–34.

- Statistics Canada, 2006. Table 38-10-0263-01. Principal statistics of the mineral industries [dataset]. Available from: doi:10.25318/3810026301-eng

- Statistics Canada, 2011. Table 38-10-0266-01 Principal statistics of mineral industries, by North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) [dataset]. Available from: doi:10.25318/3810026601-eng

- Statistics Canada, 2023. Table 36-10-0009-01. International investment position, Canadian direct investment abroad and foreign direct investment in Canada, by North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) and region, annual (x 1,000,000). [dataset]. Available from: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=3610000901.

- Statistics Canada, 2024. Table 36-10-0217-01. Multifactor productivity, gross output, value-added, capital, labour and intermediate inputs at a detailed industry level [dataset]. Available from: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=3610021701.

- Stockhammer, E., 2008. Some stylized facts on the finance-dominated accumulation regime. Competition & Change, 12 (2), 184–202.

- Stuermer, M., 2018. 150 years of boom and bust: what drives mineral commodity prices? Macroeconomic Dynamics, 22 (3), 702–17.

- U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, 2024. Balance of payments and direct investment position data, by country and industry (NAICS) (millions of dollars).

- Vallieres, M., 2012. Des mines et des hommes. Histoire de l’industrie minerale quebecoise. Des origines a aujourd’hui. Quebec: Ministere des Ressources naturelles.

- Watkins, M., 1963. A staple theory of economic growth. Canadian Journal of Economics and Political Science, 29 (2), 141–58.