ABSTRACT

This paper investigates the role of national policies in the process of metropolization and metropolitan region building in Budapest. In the long term, the example of Budapest clearly shows the twists and turns of national policy-making between concentration to increase competitiveness and equal distribution designed to enhance social integration. The geographical and geopolitical position of Budapest has altered significantly since the collapse of communism. From the periphery of Moscow, the city and its hinterland became a political, economic and cultural centre of Central Europe. Therefore, it is an intriguing question if national policies actively build on the role of Budapest as engine of economic restructuring and a gateway to the global flows of capital and innovation. The paper provides a critical analysis of current policies with special attention to the process of metropolitan region building. As research findings show, policy-making in Hungary has not focused on metropolisation and metropolitan region building in the last two decades. Policy-making has had a clear follow-up character and decision-makers from the administrative side could not efficiently contribute to metropolisation and enhance the competitiveness of the metropolitan region.

Introduction

The processes of ‘metropolization’ and metropolitan region building have been gaining increasing attention in the literature (Gaussier, Lacour, and Puissant Citation2003; Elissalde Citation2004; De Lotto Citation2008; Lang Citation2012). This is not least because large cities and their hinterlands concentrate an ever-growing share of production, money and people in an utterly globalized world. Discussing the role of metropolization and metropolitan growth in socio-economic development, authors put the emphasis on different aspects of the phenomenon. Some consider it as the result of the mutually reinforcing processes of spatial concentration of (new) economic functions, advanced infrastructures, inward investment and population having an effect on the growth and spatial extension of metropolises (Friedmann Citation1986, Citation2002; Geyer Citation2002; Brenner Citation2004). Others interpret the phenomenon as the development of nodes of global networks of material and immaterial flows exercising command and control functions with excellent connectivity among them (Keeling Citation1995). Again others emphasize the allocation of specific functions as driving forces of economic and demographic development within the city or increasingly within a polycentric metropolitan region (Kunzmann Citation1996; Sassen Citation2002). The growing body of literature on metropolization and metropolitan region building is still lacking relevant contributions from the post-socialist countries of Central and Eastern Europe. One of the reasons may be the controversial attitude of politics and the rapidly shifting objectives of policies towards this aspect of territorial development in these countries before and after the collapse of communism.

The main aim of this paper is to enrich the literature with the analysis of the territorial development of Budapest and its metropolitan region building with special emphasis on the post-communist period and the role of national policies. Metropolization is considered here as a specific form of urban restructuring, an increasing concentration of metropolitan functions, as well as the agglomeration of economy and population within the wider national urban system, leading to territorial growth and spatial extension. In this respect, metropolization also means growing territorial disparities between core urban regions and peripheral regions (Brenner Citation2004; Lang Citation2012, Citation2015) what is exactly the central question of this theme issue. National policies in Europe targeting regional/metropolitan development have been based basically on two competing paradigms: concentration vs. equal distribution. The concept of concentration tends to appear in periods of rapid modernization and restructuring, when the main objective of national policies focuses on economic development and competitiveness. However, if the emphasis lies on social integration and territorial cohesion, the equal distribution of resources often tends to come to the fore. This paper aims to highlight the role of these competing paradigms in national policies in Hungary with a historical perspective and with special emphasis on the metropolitan region of Budapest.

Budapest is the symbolic heart of Hungary as far as its political, economic, administrative and cultural functions are concerned. More than one-third of the national GDP is produced in the city, and nearly half of the foreign direct investment arriving into the country after 1989 was realized here. All global companies settling in Hungary have their headquarters in Budapest, all the main national institutions have their seat in the city which serves as the main economic pole and transport hub for Hungary, and beyond. The relative geographical position of Budapest and its metropolitan region has altered significantly since the dismantling of Iron Curtain. From the periphery of Moscow, the city and its hinterland became one of the new political, economic and cultural centres of the European Union. Being part of a Central European development axis which connects the city with Vienna, Prague, Dresden and Berlin, as well as Cracow and Warsaw, Budapest is a significant location in this secondary European urban network, because it lies in the conjunction of different development zones (Tosics Citation2005).

The paper is structured as follows: first, we discuss briefly the relevant literature focusing on metropolization, and then we turn towards Budapest and discuss the pre-1989 epochs of metropolization with an attention on the role of national policies. In the analytical part of the paper, the legal framework of metropolization in post-socialism, as well as the most important features of territorial development in Budapest are discussed. This is followed by a critical analysis of current policies with special attention to the process of metropolitan region building. At the end of the paper, we come to the conclusions and reflect upon the theoretical context.

Theoretical contexts of metropolization and metropolitan governance

The process of metropolization means both functionally and morphologically a spatial development being increasingly centred on large cities (Leroy Citation2000; Elissalde Citation2004). From a functional point of view, metropolization is often seen as the result of (new) economic, command and control functions increasingly concentrating in certain metropolitan regions (Friedmann Citation2002; Geyer Citation2002). Metropolization in this regard is a specific form of urban restructuring, a new type of urban growth due to the altered political and technological conditions, the globalization of economic activities, the de-industrialization of cities and the establishment of new economic functions in metropolises, which become the new economic centres of growth (Lang Citation2012). Most recently these highly metropolitized urban regions are also characterized by a strong economic restructuring towards creative economy and innovation (Krätke and Borst Citation2007; Musterd et al. Citation2007). From a morphological point of view, these new functions tend to appear more and more in sub-centres around major cities, as metropolitan development goes far beyond the city limits resulting in a polycentric pattern (Kunzmann Citation1996; Leroy Citation2000; Sassen Citation2002).

Metropolitan regions tend to become more and more important nodes in global networks. According to Camagni (Citation2009), these networks are important in economic specialization and exchange of goods, persons and information, and in the improvement of corresponding infrastructure systems enabling metropolitan networking and strengthening tangible or intangible assets and potentials. Regarding competitiveness international accessibility and connectivity, business embeddedness, skilled labour force as well as good environmental and living conditions for residents and visitors are in fact the most important competitive assets of European metropolises (Kresl and Ietri Citation2014).

Accumulated economic, social, political, cultural, physical and functional structures play an important role in the economic competitiveness and are crucial for continued stable urban and regional development. In the global competition those metropolitan regions will be able to capture eminent positions and to gain economic advantages that are strong enough to create favourable conditions for basic engines and activities of the economy (Chapain et al. Citation2009). This presumes that current conditions for economic development in the metropolitan regions across Europe are at least partly determined by their historic development paths (North Citation1990).

Metropolitan development is often regarded as the source of increasing effectivity of economy and growing competitiveness resulting from area-based advantages through growth in terms of population, jobs and traffic, through the attraction of specific and high-ranked functions and economic specialization. The growth of population and workplaces takes place not only in the core city, but also in the wider metropolitan region (Parkinson et al. Citation2004). Some authors emphasise, however, that metropolitan growth is very uneveven in space producing concentrations of activities, functions and flows, and contributing to increasing social polarization and spatial fragmentation (Gaussier, Lacour, and Puissant Citation2003).

The intervention of nation-states in urban growth and agglomeration processes has a long tradition in Europe (Nijkamp and Mills Citation1986). National policies of urban and regional development are often sources of conflicts because of the dilemma of two opposite objectives, that is to say, on the one hand, improving the capacity of city-regions in order to improve competitiveness at a global scale and, on the other hand, aiming a balanced spatial development in the whole country in order to facilitate social integration (Ache Citation2011). Productivity or equity, this has been the main challenge for actors trying to influence regional and urban development in the past (Boudreau et al. Citation2006). To resolve this conflict, some national governments (e.g. the Netherlands, or Scandinavian countries) formulated the so-called concentrated deconcentration concept from the 1960s, channelling urban growth from the largest (usually capital) cities to a selection of growth centres on the countryside (Bontje Citation2001).

Equally important issue of metropolisation is the nature and role of metropolitan governance. Since the 1990s, the scientific debate on metropolitan governance has been dominated by four strands of thoughts: the metropolitan reform tradition, the public choice concept, the concept of territorial capital and the new metropolitan governance approach (Giffinger and Wimmer Citation2005). Metropolitan reform tradition considers the existence of a large number of independent local governments as the main obstacle to efficient operation within metropolitan regions and suggests that major metropolitan areas should be governed by one political entity and administration should be organized as a single integrated system (OECD Citation2006). The public choice concept perceives local governments competing for residents as privately owned companies competing for the production or sale of goods and emphasizes that it is more efficient and democratic if localities within metropolitan areas compete for the production or sale of public services among themselves than to leave those services to one monolithic government entity (Sellers and Hoffmann-Martinot Citation2007). The concept of territorial capital emphasizes that each region has a specific territorial capital (i.e. all local, tangible and intangible, endogenous and exogenous, public and private assets enhancing the development of an area) and territorial development policies should foremost help areas to develop territorial capital (Capello Citation2016). According to De Lotto (Citation2008), the problem regarding planning and governance is that metropolization is the result of a complex set of inter-scalar phenomena that do not always have an adequate planning dimension. Therefore, new metropolitan governance has been increasingly used for describing new ways of governing metropolitan areas (Salet, Thornley, and Kreukels Citation2003), whereby ‘new’ implies a form of governance, which is more inclusive and participatory compared to the traditional hierarchical government. Regarding new metropolitan governance many experts emphasize that ‘global cities’ are regulated by global market forces (Storper Citation1997; Scott Citation2001), hence, these ‘post-modern cities’ should be interpreted as ungovernable cities (Scott and Soja Citation1996; Soja Citation2000; Dear Citation2001). Others like Le Galès criticize the ungovernability hypothesis and argue that cities are able to govern their territory and metropolitan development can be stimulated and fostered by national or regional policies (Le Galès Citation2002).

Based on the literature, we assume that Budapest as the main economic power centre of Hungary and the winner of transition (Smith and Timár Citation2010) has gone through rapid metropolization since the collapse of communism. We also think that the process of metropolization substantially altered the core–periphery relations within the country generating more pronounced regional disparities, a polarization of income and social opportunities. In the light of these assumptions our research questions are formulated as follows:

What have been the main objectives of national policies focusing on economic restructuring and territorial development in the country?

How the concepts of concentration versus territorial cohesion have been applied by national policy documents?

To what extent have national policies focused on metropolization and metropolitan governance in Hungary since 1990?

Twists and turns of metropolitan region building in Budapest: a historical perspective

Over the last one-and-a-half century, the metropolitan region of Budapest has been the target of different political aspirations. In this respect we can distinguish, on the one hand, periods when national politics considered Budapest and its metropolitan region as an engine of economic and social modernization and policy goals were set accordingly. On the other hand, there have also been periods when the political power saw a challenge in the weight and role of Budapest and its region and formulated distributive policies and strategies in order to achieve a more balanced territorial development in Hungary.

Pre-communist phase of metropolitan development

The early phase of metropolitan region building in Budapest was closely related to the attempts of Hungary to separate from Austria and form a nation-state in the second half of the nineteenth century. The main goal of Hungarian regional policy was to create a big and modern European city, expressing territorial autonomy in rivalry with Austria and Vienna.

The compromise between Austria and Hungary in 1867 created the political preconditions for the creation of Budapest in 1873 through the unification of three existing urban cores (Buda, Pest and Óbuda). At the time of the 1869 census with a total population of 280,000, the three core cities of later Budapest ranked 17th among the large cities of Europe. Through the compromise Hungary was granted a status equal to that of Austria within the Habsburg Empire. This made Budapest the twin capital of the dual monarchy and opened new opportunities for metropolization. The last third of the nineteenth century was the period of fastest urban growth and territorial expansion. Migrants were attracted primarily by the vigorous industrial and economic development. The rate of population growth was especially dynamic during the last decade of the century (45% in one decade). As a consequence, by the turn of the century the population of Budapest increased to 750,000, and the city advanced to the eighth place in Europe.

To keep control over the vibrant development a powerful body, called Council of Public Works, was set up in 1870. The members of the Council were delegated by both the national government and the three core cities. The ex officio chairman of the Council was the Hungarian Prime Minister (Enyedi and Szirmai Citation1992). Thus, the Hungarian government safeguarded the control and supervision of the territorial development of the young metropolis, and in this respect the Council undoubtedly expressed the centralizing efforts of the Hungarian government. It elaborated an imposing master plan which laid down the main features of spatial development, setting the direction of expansion and dividing the city into land-use zones. Infrastructural development including the rapid extension of public transport network served the overarching goal of metropolitan region building.

The First World War and the consequent dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy altered the spatial relations of Budapest. In the Versailles Peace Treaty Hungary lost 71% of its territory and 66% of its population. Budapest once the capital city of a country with 21 million inhabitants now became the primary centre of a country with 7.6 million inhabitants. Budapest with more than 1 million inhabitants became the lonely star of the Hungarian urban system. Right after the First World War 62% of the country’s industrial output, and 45% of industrial employees concentrated in the city.

The main objective of national policies in this period was the restoration of the territorial integrity of Greater Hungary. In this respect Budapest, its economic weight as well as political position (centre of the shortlived communist Councils Republic in 1919) was considered to be a challenge by politics and more attention was devoted to the development of the country-side, especially secondary urban centres. Subsequently, the development of Budapest slowed down in the inter-war period. Its population continued to grow, but at a much slower pace (Compton Citation1979).

Metropolitan development during communism

At the end of the 1940s, a new communist constitution was implemented in Hungary, land and property was nationalized and nearly all commercial functions were prohibited or severely controlled (Enyedi and Szirmai Citation1992). Urban development was interpreted as a sector of the national plan. The communist political structure and the centralized management of society and economy eliminated the possibility of local planning.

According to Act I of 1950, local governments were replaced by hand-picked councils where representatives of the communist party were in absolute majority. This act also solved the question of ‘Greater Budapest’ that is the administrative union of suburban municipalities with the core city. As part of the communist administrative reforms, 23 independent suburbs were attached to Budapest on 1 January 1950, at the same time 22 districts were created inside the city boundaries.

The post-Second World War collectivization of land as well as the forced development of industry attracted many immigrants to Budapest from the countryside which resulted in significant growth of both the number of inhabitants and industrial workers in the 1950s. However, industrialization policies of the communist state put more emphasis on the development of new towns and secondary urban centres with strong industrial profile. Consequently, despite the rapid population and industrial growth the share of Budapest within the urban population of Hungary decreased from 48.5% to 45.1% between the 1949 and 1960 censuses, and its share within industrial workers fell from 51% to 41% (Zoványi Citation1986).

From the early 1960s, in accordance with national demographic trends and the new regional development policy putting more emphasis on the balanced distribution of resources the growth of Budapest gradually slowed down again. The city entered the post-industrial phase of urban development, factory employment started to decline, at the same time rapid growth of services took place. The shrinkage of industry was also fostered by administrative measures. Between 1968 and 1981, approximately 250 industrial plants were closed down or relocated from Budapest mainly for ecological reasons, while the establishment of new industrial plants was strictly restricted (Kovács Citation1994).

In 1971, the government adopted the so-called National Settlement Network Development Concept which was the main urban development policy of the communist period and targeted a more balanced territorial development within Hungary (e.g. it designated five counterpoles to Budapest: Miskolc, Debrecen, Szeged, Pécs, Győr). The concept detailed a hierarchical, Christaller-type model of central places which were intended to bring more or less the same level of services (education, health care, public transport, etc.) within the reach of all Hungarians, moderating differences in living conditions. As a result government expenditures for public services in urban centres of the countryside and larger villages designated to become urban places increased and regional inequalities within Hungary gradually lowered.

The spatial expansion of Budapest accelerated from the 1960s due to large-scale housing development programmes. The late 1960s and 1970s were the ‘golden age’ of housing construction, when 15,000–20,000 dwellings were completed annually in Budapest. Great part of the new dwellings was built by the state mostly in the form of large housing estates. Due to site constraints, these estates were constructed predominantly on undeveloped ‘greenfield’ sites in peripheral locations. Most estates were poorly served by transport and other facilities and the organic link with the city was broken.

The state-socialist epoch also brought about major changes in the development of the suburban zone. As housing shortage prevailed in the capital city, the communist authorities introduced strict administrative restrictions to control the migration to Budapest in 1958. Only people who had worked or studied in Budapest for five years could acquire permanent residence status (Kovács Citation1994). This resulted in the rapid growth of suburban localities especially in the less prestigious south eastern sector around the city and a new pattern of commuting evolved. The communist period also brought about new policy approaches regarding the official recognition of the metropolitan region. After long debates, the official boundaries of the agglomeration of the city were set in 1971. Forty-three settlements were classified to be part of the agglomeration zone, an area which extended 1143 km2 and provided home for about 400,000 inhabitants. However, under the highly centralized communist system planning or governing competencies on the metropolitan region level remained out of question.

The transformation of Budapest metropolitan region after 1990

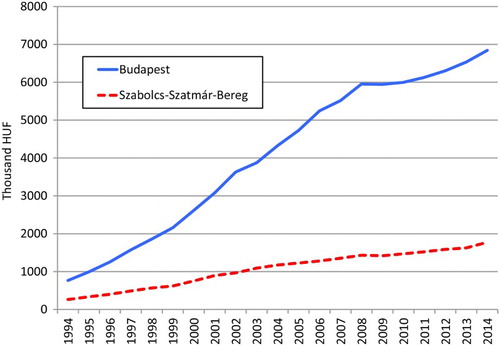

Despite the lack of clear metropolization policy and metropolitan governance, the role of Budapest, and its economic and functional dominance within Hungary, has not changed after the collapse of communism. The capital city has even strengthened its position in the settlement network of Hungary (). Budapest and its agglomeration has been the main target of foreign capital investment and technology transfer, the development of creative and knowledge-intensive industries, including R&D and higher education turned increasingly towards the city. Consequently, territorial disparities within Hungary have clearly increased since the change of regime ().

Figure 1. Per capita GDP in Budapest and the least developed Hungarian county.

Table 1. Indicators on the relative position of Budapest in the national context.

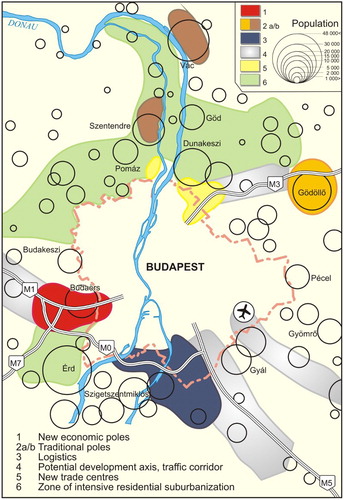

The change of political regime launched a fundamental transformation in the public administration and planning system in Hungary. As Act 65/1990 re-established self-governance local councils were replaced by democratically elected local governments. According to this law, municipalities enjoy equal rights in Hungary independently from their size or legal status. ‘Municipality’ as such became understood in Budapest at two levels: city and district, thus, a two-tier administrative system was introduced where the 22 (since 1994 already 23) districts of the city enjoyed equal rights with the City Government of Budapest (Tosics Citation2006). At the metropolitan level 89/1997 Government Decree identified Budapest Agglomeration with 78 independent settlements and Budapest. Thus, in 1997 there were 102 independent self-governed units in the metropolitan region comprising Budapest, 23 city districts and 78 agglomeration settlements (due to separations their number grew to 80 in 2004) ().

Figure 2. The structure of the metropolitan region of Budapest.

In spite of the fact that in the 1990s, the cooperation, interdependence as well as physical infrastructural linkages between Budapest and its agglomeration were further intensified the metropolitan zone of Budapest remained only a statistical but not an administrative (not even a real planning) unit. Right from the beginning of the 1990s, it became extremely difficult to harmonize interests and development plans within Budapest and its metropolitan region. Conflicts arose over the clashing interests of the districts and the City Government on the one hand, and between Budapest and the suburban municipalities on the other. The major disadvantages of the two-tier administrative system were rooted in the overlapping spheres of responsibility and the conflicting political interests. In some respects Budapest remained centralized (strategic development of the infrastructure, public transportation) while in others such as the distribution of resources the city followed a decentralized model (Enyedi and Pálné Kovács Citation2008).

Municipalities lying in the agglomeration zone of Budapest had also different interests from the rest of Pest County where they administratively belonged to. It was only after 1996 with the acceptance of the Act on Regional Development and Physical Planning that the Development Board of the Budapest Agglomeration was established which was intended to integrate representatives from the public, private and the non-profit spheres. The Development Plan (Concept) of the Budapest Agglomeration was also the product of this period (1998–1999). The Concept was, however, never put into practice lacking the governmental assent. The Board finally was abolished by the government when the Development Board of the Central Hungary (NUTSII) Region was established in 1999.

The change of political system and the return to market economy resulted in substantial spatial restructuring in the city and its metropolitan region after 1990. Given the highly decentralized neoliberal planning regime the development potentials of the different functional urban zones were re-evaluated by the property market. Market-led development processes brought about the up- and downgrading of different urban zones changing their position within the metropolitan region. Undoubtedly, the greatest winner of metropolitan restructuring was the zone of agglomeration. During the last two decades urban sprawl has become one of the most significant urban phenomena in Budapest (Kovács and Tosics Citation2014).

Regarding its population Budapest has lost nearly 300,000 residents between 1990 and 2010. This sharp population loss has been caused by a combination of natural decrease (accounting for about two-thirds of the population decline) and an outflow of people to the suburbs. The loss of population became most pronounced by the late 1990s early 2000s, reaching a net loss of 18,000 residents per year. This trend was gradually turned back and since 2008 Budapest has been recording a migration surplus again. In the zone of agglomeration, on the other hand, a slight natural decrease in population has been offset by the massive outflow of people from the urban core. Consequently, the population of the agglomeration zone grew by 44% since 1990, crossing the 800,000 thresholds in 2010.

The main destination of suburban migration has been predominantly rural communities in the hilly areas north and west of the city, which offer high-quality residential environments in attractive natural settings (Kok and Kovács Citation1999). The majority of these new developments have been concentrated inside existing suburban settlements (in the form of infill on available plots) or at their fringes (typically on greenfield sites). The suburbanization of industry and services started somewhat later in the late 1990s. It was fuelled primarily by the establishment of new industries and businesses, large-scale office developments and other commercial investments at major transport hubs of the metropolitan periphery (Dövényi and Kovács Citation2006). Due to the growth of individual car use, the settlement network of the agglomeration started to produce an expansive and spontaneous territorial development driven by the free market and local interests.

As a consequence, economic and spatial changes of the metropolitan region were most intense on the periphery. Not only did the existing functional areas change in the process of transition but new areas of economic growth with novel functional specializations emerged (Dövényi and Kovács Citation2006). According to empirical evidences several new economic poles arose as a result of the restructuring process ().

Figure 3. Development poles in the Budapest Metropolitan Region.

The administrative fragmentation described earlier has significantly undermined any efforts of growth management and planning in the city-region of Budapest. The two-tier system of government within the city (with weak municipal powers and fairly autonomous city districts) and the complete lack of metropolitan governance did not allow for efficient citywide coordination of development and investment decisions (Tosics Citation2006). As a result of the extreme decentralization of political and administrative power, the City of Budapest had even less planning authority beyond its administrative boundaries. While, on the one hand, suburban governments actively enticed new businesses and residents, on the other hand, the City of Budapest did not have a clear strategy about how to stop the loss of population and economic assets for a long time (Kovács and Tosics Citation2014).

Policies on metropolization and urban development in Hungary after 1990

Based on previous findings of Szemző and Tosics (Citation2005), we can distinguish five periods in Hungary since the change of regime regarding the objectives of national policies focusing on territorial development: (i) ‘development policy for smaller settlements’ (1990–1994); (ii) ‘starting re-centralization’ (1994–1998); (iii) ‘continuing re-centralization, coupled with strong countryside development policy’ (1998–2002); (iv) ‘emerging decentralization by developing larger cities within the country’ (2002–2010) and (v) since 2010 ‘strong centralization’. This reflects clearly that twists and turns in policy orientation became more frequent in the post-socialist democratic era than ever before.

The legal framework of current regional and urban policy was laid out in Act XXI of 1996 on Regional Development and Physical Planning and standardized on the eve of EU accession in 2004. The act created a new ‘regional level’ of territorial administration. With this law Hungary was the first among the accession countries to create a legal framework for regional development according to the spatial development criteria of EU. However, distribution of the responsibilities and power sharing between the new regional bodies and existing government institutions was unclear (Horvath Citation2008).

The framework for current urban policies and strategies is set by the National Spatial Development Concept (NSDC) that was approved by the Parliament in 1998 and was subsequently reviewed in 2005. The concept summarized the general objectives of urban development in Hungary, focusing on the issues of spatial competitiveness and sustainable development, territorial cohesion and the integration of Hungarian urban system into the European network. Regarding the role of Budapest, the concept set the medium-term goal of a ‘competitive metropolitan region of Budapest’ to be achieved by:

strengthening the international business functions and European relations of Budapest as a gateway city to South Eastern Europe and the Balkan;

utilizing the advantages of high-tech industries, knowledge-based economic activities and highly qualified labour of the city;

strengthening the international tourist hub function of the city;

developing a liveable city through comprehensive environmental management and the revitalization of brownfield sites;

rehabilitating the crisis areas and extending the green spaces;

developing a balanced and well-functioning agglomeration around Budapest, through the prevention of urban sprawl, improvement of transport links and strengthening the role of sub-centres and

strengthening the inter-municipal cooperation among Budapest, towns and villages within its agglomeration through joint institutions.

The most important development policy on national level for the previous programming period was the New Hungary Development Plan (2007–2013). The plan designated seven development poles (including Budapest) within the country according to the concept of ‘concentrated deconcentration’ in order to increase the international competitiveness of Hungary. The six poles on the countryside coincided with the five ‘counterpoles’ of Budapest set by the communist National Settlement Network Development Concept (1971), only two county seats Székesfehérvár and Veszprém as new NUTSII twin-centres were newcomers.

The programming period of 2007–2013 has brought about also a new situation, because regions (NUTSII) had the chance to work out their own Operational Programmes in order to finance regional strategies and programmes. The most important development strategy on regional level regarding Budapest was the Central Hungary Operational Programme. The vision of the programme was to create a creative and innovative region in the hearth of the country. One of the main objectives of the programme was, on the one hand, to strengthen the role of Budapest as a key development pole and as an international economic centre. On the other hand, equally important objective was to establish a conurbation system operating in a harmonious and sustainable manner by developing sub-centres around Budapest forming a more balanced spatial structure. In spite of the regional development and rural development policies and initiatives launched by the central government, income differences between Budapest and the peripheral areas of Pest County have increased, and the decline of peripheral rural areas has worsened over the past 10 years. Therefore, it was aimed to reduce socio-economic differences within the region by providing development assistance for the depressed peripheral micro-regions.

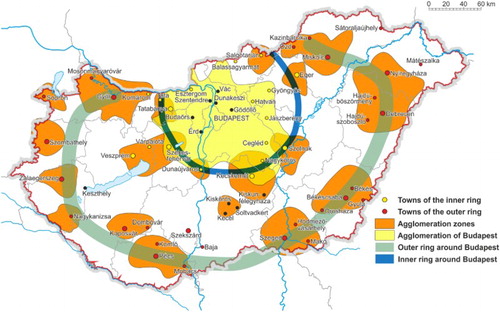

Another important policy document of the post-1990 era was the Spatial Development Concept and Strategic Programme for the Budapest Agglomeration (2005). The concept had a specific functional interpretation on urban catchment areas in general, namely as a metropolitan mosaic of partly overlapping employment zones that are also part of an extensive commuter area around Budapest. The concept distinguished a three-tier system of sub-centres in the wider metropolitan area. On the lowest level the so-called partner centres, at middle level intermediary centres (e.g. Gödöllő, Vác, Monor) and at the top level the so-called bearing-cities, that is, larger centres in the distance of 60–80 km from Budapest, with substantial manufacturing industries and services (e.g. Esztergom, Tatabánya, Székesfehérvár, Kecskemét, Gyöngyös) were distinguished.

Another decisive local policy document was the Medium-term Urban Development Programme for Budapest. This so-called Podmaniczky Programme formulated the targets of urban development for the programming period of 2007–2013. The Podmaniczky Programme gave clear orientation and set the priorities of urban development, defined the goals of development planning, as well as goals for local authority sector-based planning. This document can be considered the most important policy of the post-socialist period that provided orientation for the metropolisation process in Budapest. In order to achieve a ‘liveable city’, the document envisaged the rehabilitation of residential, public and brownfield areas, the development of environmentally-friendly public transport system, the expansion of green areas within Budapest, and increasing cooperation between the core city and its agglomeration.

After 2010, development strategies and policies have been either substantially revised or abolished by the newly elected conservative government. At the same time, policy-making and strategy-building processes as well as the financing of urban development programmes became extremely centralized. Part of the centralizing efforts was the amendment of the Act on Local Governments in 2011 (Act CLXXXIX/2011). This meant that the composition of Budapest General Assembly was radically changed by course of law. Since 2014, breaking with the past practice, the assembly has 33 members, and only the mayor is elected directly. Members are the mayors of the 23 districts and other 9 representatives from the compensation party lists. With this amendment, the government could ensure the majority of the conservative members in the local authority.

In 2012, the national government started to elaborate the new National Development and Territorial Development Concept for the period of 2014–2020. The new development concept was passed in 2014. Regarding urbanization the concept emphasizes the importance of liveable and sustainable cities where urban development is based on creative, innovative and competitive economy and accessibility. Urban areas appear as fundamental units of spatial development in this new approach. The concept recognises that cities cannot be interpreted as independent entities any more and they should be handled together with their catchment areas. The concept foresees the development of a multi-centred settlement system with decentralized and network-based spatial structure decreasing the excessive weight of Budapest. The connections between a city and the surrounding area can be coordinated by multi-level governance: the framework, rules and institutions of territorial organization must be defined centrally, coordination at the medium level, that is by counties, will support territorial organization, but local level must also be involved in territorial organization in order to achieve functioning development territories.

Another innovative feature of the concept is networking of urban areas around the metropolitan region of Budapest in two rings (). The economic co-operation between Budapest and the inner and outer ring of cities open new perspectives for metropolization and the development of the so-called Budapest Business Region. After a long time of ignorance planning together appears as a need for co-operation. Taking into consideration the intermediate position of Budapest between the Eastern and Western parts of Europe, this extended metropolitan area could function as a hub for European networks and interregional economy. Not only Budapest, but also the most competitive urban centres of the country should be integrated into the European urban network through enhanced collaboration and cooperation. Especially cross-border location and cooperation could play a significant role in this process.

Figure 4. The inner and outer urban rings around Budapest according to official policy documents.

It seems that the current administrative situation and the state-controlled development policy inhibit the chance of effective metropolitan governance and block the establishment of an institutionalized metropolitan government for a long time. In the metropolitan region, the resource allocation of the state extremely strengthened and, as a result of this, the patterns of uneven spatial development exacerbated. Like other post-socialist metropolitan regions, spatial processes are not determined only by socialist legacies or path dependencies, but they are transformed by intertwining neoliberal state and capital (Golubchikov, Badyina, and Makhrova Citation2014). In Hungary, it can also be observed that transformation of space depends largely on personal relationships between local leaders and the governmental decision-makers, and political embeddedness and stability of local governments play important roles as well. In addition, due to high level of corruption, the allocation of development resources does not really take into account the actual needs (Jancsics Citation2013; Fazekas, Lukács, and Tóth Citation2015). This background induces random investments and unpredictable spatial changes in the Budapest metropolitan area.

The national policy is interested in the administrative fragmentation which prevents the development of well-functioning metropolitan governance. Typically, national government supported Pest county (i.e. the county around Budapest) to form an independent NUTSII region after 2020 and the Government Decree of 29 December 2015 (No. 2013/2015) set up the rules for the process of separation. According to the GDP per capita, Pest county might be able to obtain more financial resources from the EU structural and cohesion funds after the split. Nevertheless, due to the state-controlled development policy and resource allocation, the new regional system can deepen the uneven development and support the seemingly spontaneous and sporadic investments which are, however, based on the common interests of nation-state and corporates.

In the absence of metropolitan governance and regulation, the rules of the growth-oriented state and the interests of capital together shape the metropolitan region. The weakening of the jurisdiction and control rights of local governments with the transfer of authority to government offices in 2013 not only signalized centralization, but these steps clearly showed that the national policy promotes the further expansion of private property. The new rules lead to an increase in the number of unmanageable environmental, infrastructural and social conflicts, which already concern seriously the suburban region.

Discussion and conclusions

The twists and turns of national policies regarding metropolization and metropolitan region building in Budapest shows the conflicts of two competing policy objectives, competitiveness via concentration versus social integration via equal distribution. In the second half of the nineteenth century during the period of nation-state building, Hungarian politicians considered Budapest as an engine of capitalist industrialization and national modernization. The unification of the three urban nuclei, the strong planning control of development, and the rapid modernization of urban infrastructure adjoining with robust metropolization all served the creation of a modern metropolis, a national capital. However, when Hungary was desintegrated after the First World War and the weight of Budapest became disproportionately large in the national context policy responses were more focused on territorial equilibrium. The communist regime acknowledged the territorial expansion and metropolitan growth of Budapest with creating Greater Budapest in 1950; however, it also considered the overweight of Budapest and regional disparities in productivity and income as a challenge. 1971 has brought about the first attempts in policy-making to resolve the conflicts of concentration versus deconcentration in Hungary with the application of the ‘concentrated deconcentration’ concept (Bontje Citation2001). These efforts resulted only temporal solutions and regional disparities started to grow again rapidly under neoliberal policy-making and globalization after the collapse of communism.

The twenty-first century has brought about an ever-sharpening competition between different regions of the world. Regional competitiveness is basically determined by cities, and this is why competition between the regions involves a bitter and growing contest among big cities (Musterd and Kovács Citation2013). A region or a country will be successful if its cities are successful and cities will flourish if the wider region flourishes. In the global competition those city-regions will be able to capture eminent positions and to gain economic advantages that are strong enough to create favourable conditions for the above-mentioned basic engines. In this respect economic, political, social, cultural and functional structures accumulated throughout the history play an important role. Multi-layered cities with diversified economic and functional profile enjoy advantages in the current global competition of city-regions.

Our analysis showed that Budapest is a true multi-layered city that has successfully revitalized some of its old functions after the collapse of communism (Egedy, von Streit, and Bontje Citation2013). However, it became also clear that policy-making in Hungary has not been pro-active and supportive for the development of local economy and metropolization. Policy and strategy building has had a follow-up character and decision-makers from the administrative side could not efficiently contribute to metropolization and enhance the competitiveness of the metropolitan region. In this sense metropolisation that took place in the last two decades has been much more the result of market processes than policy interventions.

Post-socialist urban development has brought about several shortcomings in Hungary caused mainly by the lack of development coordination efforts. Suburbanization and urban sprawl have been particularly strong and have fundamentally rearranged the inter-municipal relations, especially around larger cities, and most notably around Budapest (Kovács and Tosics Citation2014). The uncoordinated, chaotic growth of urban spaces exceeds administrative boundaries and transforms their broader environment. Thus, suburbanization has left its imprint on the territorial development of Budapest more than metropolisation.

Regarding metropolitan governance none of the previous regimes has been successful and in this respect the EU accession in 2004 did not make too much difference either. After 2010 centralization efforts of the national government went against any forms of metropolitan-level planning or governance, and even the internal administrative rearrangements of the city became part of the agenda. First step in this direction was the radical reduction of the number of representatives in the city assembly in 2014. Decision-making has been further centralized and voting is based now on population size of districts. There are further plans on behalf of the national government for the administrative restructuring of the city weakening local autonomy and planning rights (e.g. reducing the number of districts or creating new administrative units – townships – on the territory of Budapest); however, according to political debates earliest measures in this field are to be expected in 2019.

As international examples imply, the future success of Budapest in the sharpening global competition depends very much on policy-making if instead of top-down solutions bottom-up initiatives and local government arrangements prevail under a harmonized planning and administrative system. Since the EU accession, the ruling Hungarian governments have failed to create such (administrative and planning) framework conditions challenging the future competitiveness of the city.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ache, P. 2011. “‘Creating Futures that Would Otherwise not be’ – Reflections on the Greater Helsinki Vision Process and the Making of Metropolitan Regions.” Progress in Planning 75 (4): 155–192. doi: 10.1016/j.progress.2011.05.002

- Bontje, M. 2001. “Dealing with Deconcentration: Population Deconcentration and Planning Response in Polynucleated Urban Regions in North-West Europe.” Urban Studies 38 (4): 769–785. doi: 10.1080/00420980120035330

- Boudreau, J., P. Hamel, B. Jouve, and R. Keil. 2006. “Comparing Metropolitan Governance: The Case of Montreal and Toronto.” Progress in Planning 66 (1): 7–59. doi: 10.1016/j.progress.2006.07.005

- Brenner, N. 2004. New State Spaces: Urban Governance and the Rescaling of Statehood. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Burdack, J., Z. Dövényi, and Z. Kovács. 2004. “Am Rand von Budapest – Die Metropolitane Peripherie zwischen nachholender Entwicklung und eigenem Weg.” Petermanns Geographische Mitteilungen 148 (3): 30–39.

- Camagni, R. 2009. “Territorial capital and regional development.” In Handbook of Regional Growth and Development Theories, edited by R. Capello and P. Nijkamp, 118–132. Northampton: Edward Elgar.

- Capello, R. 2016. Regional Economics. 2nd ed. New York: Routledge.

- Chapain, C., C. Collinge, P. Lee, and S. Musterd. 2009. “Can we Plan the Creative Knowledge City?” Built Environment 35 (2): 157–164. doi: 10.2148/benv.35.2.157

- Compton, P. 1979. “Planning and Spatial Change in Budapest.” In The Socialist City, edited by R. A. French and F. E. I. Hamilton, 461–491. New York: John Wiley.

- De Lotto, R. 2008. “Assessment of Development and Regeneration Urban Projects: Cultural and Operational Implications in Metropolization Context.” International Journal of Energy and Environment 2 (1): 25–34.

- Dear, M. 2001. The Postmodern Urban Condition. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Dövényi, Z., and Z. Kovács. 2006. “Budapest: The Post-socialist Metropolitan Periphery between ‘Catching up’ and Individual Development Path.” European Spatial Research and Policy 13 (2): 23–41.

- Egedy, T., A. von Streit, and M. Bontje. 2013. “Policies towards Multi-layerd Cities and Cluster Development.” In Place-making and Policies for Competitive Cities, edited by S. Musterd, and Z. Kovács, 35–58. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Elissalde, B. 2004. Metropolisation, Hypergeo. http://www.hypergeo.eu/article.php3?id_article=257.

- Enyedi, G., and I. Pálné Kovács. 2008. “Regional Changes in the Urban System and Governance Responses in Hungary.” Urban Research and Practice 1 (2): 149–163. doi: 10.1080/17535060802169849

- Enyedi, G., and V. Szirmai. 1992. Budapest – a Central European Capital. London: Belhaven Press.

- Fazekas, M., P. A. Lukács, and I. J. Tóth. 2015. “The Political Economy of Grand Corruption in Public Procurement in the Construction Sector of Hungary.” In Government Favouritism of Europe. The Anticorruption Report, edited by A. Mungiu-Pippidi, 53–68. Barbara: Budrich Publishers.

- Friedmann, J. 1986. “The World City Hypothesis.” Development and Change 17 (1): 69–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7660.1986.tb00231.x

- Friedmann, J. 2002. The Prospect of Cities. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Gaussier, N., C. Lacour, and S. Puissant. 2003. “Metropolitanization and Territorial Scales.” Cities 20 (4): 253–263. doi: 10.1016/S0264-2751(03)00032-5

- Geyer, H. S. 2002. International Handbook of Urban Systems. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Giffinger, R., and H. Wimmer. 2005. “Cities Between Competition and Co-Operation in Central Europe.” In Competition between Cities in Central Europe: Opportunities and Risks of Co-operation, edited by R. Giffinger, 6–19. Bratislava: Road.

- Golubchikov, O., A. Badyina, and A. Makhrova. 2014. “The Hybrid Spatialities of Transition: Capitalism, Legacy and Uneven Urban Economic Restructuring.” Urban Studies 51 (4): 617–633. doi: 10.1177/0042098013493022

- Horvath, Gy. 2008. “Hungary.” In EU Cohesion Policy after Enlargement, edited by M. Baun and D. Marek, 187–204. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Jancsics, D. 2013. “Petty Corruption in Central and Eastern Europe: The Client’s Perspective.” Crime, Law and Social Change 60 (3): 319–341. doi: 10.1007/s10611-013-9451-0

- Keeling, D. 1995. “Transport and the World City Paradigm.” In World Cities in a World System, edited by P. L. Knox, and P. J. Taylor, 115–131. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Kok, H., and Z. Kovács. 1999. “The Process of Suburbanization in the Agglomeration of Budapest.” Netherlands Journal of Housing and the Built Environment 14 (2): 119–141. doi: 10.1007/BF02496818

- Kovács, Z. 1994. “A City at the Crossroads: Social and Economic Transformation in Budapest.” Urban Studies 31 (7): 1081–1096. doi: 10.1080/00420989420080961

- Kovács, Z., and I. Tosics. 2014. “Urban Sprawl on the Danube: The Impacts of Suburbanization in Budapest.” In Confronting Suburbanization: Urban Decentralization in Postsocialist Central and Eastern Europe, edited by K. Stanilov and L. Sýkora, 33–64. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

- Krätke, S., and R. Borst. 2007. Metropolisierung und die Zukunft der Industrie im Stadtsystem Europas. Projektbericht: Otto Brenner Stiftung.

- Kresl, P. K., and D. Ietri. 2014. Urban Competitiveness: Theory and Practice. Oxford: Routledge.

- Kunzmann, K. 1996. “Europe-Megalopolis or Themepark Europe? Scenarios for European Spatial Development.” International Planning Studies 1 (2): 143–163. doi: 10.1080/13563479608721649

- Lang, T. 2012. “Shrinkage, Metropolization and Peripheralization in East Germany.” European Planning Studies 20 (10): 1747–1754. doi: 10.1080/09654313.2012.713336

- Lang, T. 2015. “Socio-economic and Political Responses to Regional Polarisation and Socio-spatial Peripheralisation in Central and Eastern Europe: A Research Agenda.” Hungarian Geographical Bulletin 64 (3): 171–185. doi: 10.15201/hungeobull.64.3.2

- Le Galès, P. 2002. European Cities: Social Conflicts and Governance. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Leroy, S. 2000. “Sémantiques de la métropolisation.” L'Espace géographique 29 (1): 78–86. doi: 10.3406/spgeo.2000.1969

- Musterd, S., and Z. Kovács. 2013. Place-making and Policies for Competitive Cities. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Musterd, S., M. Bontje, C. Chapain, Z. Kovács, and A. Murie. 2007. Accommodating Creative Knowledge. A Literature Review from a European Perspective, ACRE report 1. Amsterdam: AMIDSt, University of Amsterdam.

- Nijkamp, P., and E. S. Mills, eds. 1986. Handbook of Regional and Urban Economics. Amsterdam: North-Holland.

- North, D. C. 1990. Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- OECD. 2006. OECD Territorial Reviews – Competitve Cities in the Global Economy. Paris: OECD Publishing.

- Parkinson, M., M. Hutchins, J. Simmie, G. Clark, and H. Verdonk, eds. 2004. Competitive European Cities: Where Do The Core Cities Stand? London: Office of the Deputy Prime Minister.

- Salet, W., A. Thornley, and A. Kreukels, eds. 2003. Metropolitan Governance and Spatial Planning. London: Spon Press.

- Sassen, S., ed. 2002. Global Networks, Linked Cities. New York: Routledge.

- Scott, A. J. 2001. Global City-regions: Trends, Theory, Policy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Scott, A. J., and E. W. Soja, eds. 1996. The City: Los Angeles and Urban Theory at the End of the Twentieth Century. Los Angeles: University of California Press.

- Sellers, J., and V. Hoffmann-Martinot. 2007. “Metropolitan Governance. United Cities and Local Governments.” In Decentralization and Local democracy in the World, 256–284. Barcelona: UCLG.

- Smith, A., and J. Timár. 2010. “Uneven Transformations: Space, Economy and Society 20 Years after the Collapse of State Socialism.” European Urban and Regional Studies 17 (2): 115–125. doi: 10.1177/0969776409358245

- Soja, E. W., ed. 2000. Postmetropolis, Critical Studies of Cities and Regions. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Storper, M. 1997. The Regional World. Territorial Development in a Global Economy. New York: The Guilford Press.

- Szemző, H., and I. Tosics. 2005. “Hungary.” In Urban Issues and Urban Policies in the New EU Countries, edited by R. van Kempen, M. Vermeulen, and A. Baan, 37–60. Aldershot: Ashgate.

- Tosics, I. 2005. “The Post-socialist Budapest: The Invasion of Market Forces and the Attempts of Public Leadership.” In Transformation of Cities in Central and Eastern Europe: Towards Globalization, edited by F. E. I. Hamilton, K. Dimitrowska-Andrews, and N. Pichler-Milanovic, 248–280. Tokyo: United Nations University Press.

- Tosics, I. 2006. “Spatial Restructuring in Post-socialist Budapest.” In The Urban Mosaic of Post-Socialist Europe, edited by S. Tsenkova and Z. Nedović-Budić, 131–150. Heidelberg: Physica-Verlag.

- Zoványi, G. 1986. “Structural Change in a System of Urban Places: The 20th Century Evolution of Hungary’s Urban Settlement Network.” Regional Studies 20 (1): 47–71. doi: 10.1080/09595238600185051