ABSTRACT

Ciudad Guayana was born as an industrial new town in the early 1960s, as an ambitious national effort to stimulate the regional development of Venezuela. Its planning was the fruit of a unique partnership between the Venezuelan development agency (CVG) and the Joint Center for Urban Studies from Harvard University and the MIT. Looking for answers to the rapid urbanization issues, the academic planners were willing to test the latest planning and design approaches on the field, implementing several experimental projects. Ciudad Guayana became a useful urban laboratory that provided important urban lessons. Based on literature research, archival research at MIT and Harvard, and interviews with planners working on both teams, this paper presents how the two teams approached, debated and clashed about four significant challenges of building the new town. Ciudad Guayana provided important urban lessons, useful for similar kind of new towns and satellite cities, as the ones currently emerging in Asia, Africa and the Middle East.

1. Introduction

In the history of Latin American urban planning, Ciudad Guayana stands as one of the most visible examples of a new town built by means of centralized planning approaches (Angotti Citation2001). Planned and built during the early 1960s by the government of Venezuela as an industrial driver of national development, Ciudad Guyana was the fruit of a visionary planning process in order to achieve the developmentalist goals of this emerging country. Venezuela’s oil-driven economy had provided its government with sufficient means to give shape and to realize this ambitious regional development plan. In the same way as the production and export of crude oil had rapidly modernized Caracas, it was expected that Ciudad Guayana, would become the next episode in Venezuela’s road to progress and modernity (Irazábal Citation2004, 29).

The active involvement of prestigious international planners – from the Joint Center for Urban Studies based at Harvard University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) – was able to transfer forward-thinking planning concepts and strategies into Ciudad Guayana’s singular planning process. The Joint Centre academics worked together with local professionals from the Venezuelan government, sharing the assumption that rational and comprehensive planning approaches could provide solutions to the social and economic problems experienced by cities of developing countries.

The context of this unusual collaboration was an especially intense period for the Latin American region. Demographic growth, economic growth due to industrialization by import substitutions, and rapid urbanization processes were changing the face of the Latin American society. This produced a huge demand for jobs and shelter, which led to the rapid emergence of informal processes in the whole region. Ciudad Guayana’s plan was then a significant attempt to engender a more inclusive type of urban development in Latin America (Angotti Citation2001). The planning concepts embraced by the Joint Center planners – based on the Modern Movement democratic ideals; advocating a welfare state; attempting to shift away from top-down functional planning into participatory planning; promoting the integration of the needs of low-income groups in the plans – crashed against the views of the local counterpart and the realities of urban development in highly unequal societies. This illustrates the gap between the high planning ambitions of modern new towns and the inescapable reality of urbanization in the Global South. In such way, Ciudad Guayana can be considered as an urban laboratory that would test the main ideas of international planning to fight informality during the early 1960s.

The main aim of this study is to identify the planning concepts and strategies followed by the planners and professional teams involved in the origins of Ciudad Guayana, as well as the dilemmas that they had to deal with during the planning and implementation processes of this new town.

The examination of Ciudad Guayana’s singular planning process can provide significant insights and directions for transnational learning, useful to reflect on the planning and design of the new towns that are currently emerging within the context of the rapid urbanization processes at global level. It may be especially useful to inform planners and designers about issues of informality and ordinary city development, and planning for inclusive cities. Indeed,

after having been out of fashion for many decades (modernist new town building) is making a return in the urban planning practices of Asia, the Middle East and most recently Africa. However, the post-colonial utopian ideas of social justice have made way for the more elitist and privatised type of new city. (Van Noorloos and Kloosterboer Citation2018, 1225)

The main data sources for this analysis were the archives of the Joint Center at MIT and Harvard and the numerous publications that have appeared on the planning and development of Ciudad Guayana. Interviews with members of both the Joint Center and the local team were held to understand the motives behind the planning approaches and visits to the site were made in 2009 and 2011.

The next section explains the urban planning and development ideas in the early 1960s at international and Latin American level, explaining the context in which the local and American planners worked in Venezuela. The third section presents the origins of Ciudad Guayana as product of ideas about regional planning in that period. The several dilemmas and debates during the planning process of Ciudad Guayana – based on very different views about social inclusiveness and welfare principles – are analysed in the fourth section. The next section presents the main features of the master plan, followed by a discussion about the main lessons and findings. The last section presents the conclusions.

2. Urban planning and development ideas in the early 1960s

Latin American society was thoroughly transformed during the twentieth century, due to two important processes: the demographic transition and the process of industrialization by import substitutions. These combined processes induced the rapid transformation of the region, from a rural into an urban society. In the case of Venezuela, this was heightened by the revenues from the oil extraction – discovered in the 1920s – which accelerated the rapid urbanization of the country and turned it into the most urbanized country of Latin America in few decades.

At global level, the early 1960s were a period of great economic dynamics and change, as cities were growing fast due to the baby boom in the countries of the North and to rapid urbanization in developing countries. It was precisely during this period, when urban planning theory experienced a major shift which moved it from an urban design exercise, into a more social science-oriented discipline (Taylor Citation1999), in an effort to become more effective by paying attention to social, economic and cultural processes. This new approach also implied to consider the different scale levels and time frames, namely the strategic long-term and local short term. Urban settlements were seen as part of a system of inter-related activities, which included the social, cultural and economic aspects of city life. Planning became more comprehensive and complex, for which multidisciplinary teams of experts were considered necessary.

This new planning paradigm was fully embraced by the North American academics of the Joint Center for Urban Studies, established in 1959 by Harvard University and the MIT to study social, economic and demographic changes with effect on urban life. World-known academics and professionals like Lisa Peattie, Donald Appleyard, John Friedman, Anthony Penfold, Kevin Lynch, Charles Abrahams, John Turner and William Porter became part of the team that worked and assessed the plans for Ciudad Guayana.

In its origins, urban planning was more a design-oriented exercise, represented in visionary ‘blueprints’ plans, focused on the physical-spatial aspects of cities and urban areas. Architects and engineers worked out the plans, which generally had a vision of city beautification, enforced through land-use controls, and the opening of broad avenues, streets and parks. Gradually, the architectural and urban planning ideas of the Modern Movement – publicized through the CIAM congresses and Le Corbusier writings – became dominant. The modernist planning doctrine established zoning, or the organization of cities in separated areas for the main urban functions as a key aspect of planning, which would determine ‘both the internal order and overall shape of the CIAM city’ (Holston Citation1989, 32).

The CIAM doctrine also had an important political component, more specifically through its strong welfare orientation and egalitarian recommendations. According to the CIAM, the uncontrolled power of the private sector in the urban field, with the exclusive interest of accumulation of wealth, was the main cause of the urban crises (Holston Citation1989). Furthermore, private property was considered ‘the primary impediment to comprehensive planning’ (Citation1989, 43). One of the most famous publications regarding the CIAM ideas on urban planning, the Charter of Athens, even recommends mobilizing private property as a fundamental condition for effective planning.

In Latin America, the modernist urban ideas were dominant almost since the beginnings of urban planning in the region, something that was enhanced during the 1940s thanks to the visits of CIAM personalities, who in many cases were hired as advisers of the new planning institutions (Almandoz Citation2010). CIAM urban ideas were still very dominant in the early 1960s, as Holston (Citation1989) has explained, defining the plan for Brasilia as a ‘blueprint utopia’ that fully embodied the dictates of the CIAM manifestos. However, if for (Brazilian) architects and planners, the revolutionary aspects of the modernist ideas were present, for most others, the development of modern architecture and planning in Latin America was framed within ideas about the modernization and progress of the respective countries. This was related to the collective belief in industrialization, rationalization and technique as a way to modernization, progress and development, characteristic of the 1960s.

During that period, modernist architecture had a significant role to play in the nation building processes of many Third World nations, and as such it was closely related to state patronage (Lu Citation2011). The strong connection between architectural modernism and modernization was sought for by Latin American national governments. The former was considered an effective way of showing the accomplishments of rapid modernization to the general public, as a product of their governments’ economic ‘developmentalism’ approaches (Almandoz Citation2010). The US also embarked on important efforts to ‘modernize’ Latin American countries by means of modern architecture. More specifically, the State Department sponsored the visits of several CIAM leading figure heads to Latin America, to encourage the use of modern architecture and planning for modernization goals (Kahatt Citation2011). The assumption behind modernization theory was that traditional societies would achieve economic and social development (‘modernization’) through stages, if they incorporate similar social and economic systems as the ones in advanced economies; something which implied the adherence to the US values and the American way of life (Holston Citation1989; Irazábal Citation2004).

Modernization ideas, which included the practice of national planning, were also exported through the links between Latin American national governments and the US. In the context of the Cold War, these links were tightened through the provision of funds and knowledge to improve social and economic conditions of the Latin American region. Rapid urbanization was producing massive illegal land occupations in Latin American cities, considered by the US as a possible focus of communist insurgence. National economic planning and the provision of affordable housing for low-income residents were considered as key to improve the existing social and economic conditions. These links were consolidated in the Conference of Punta del Este, in 1961, which was the birth of the Alliance for Progress. The latter conditioned the provision of US funds to the preparation of comprehensive plans for national development; produced a remarkable surge of housing loans in most countries of the Latin American region; and consolidated US dominance on policy matters. Processes of national economic growth were considered closely intertwined with North American technological expertise (Angotti Citation2001).

3. Regional planning and the origins of Ciudad Guayana

The oil-driven ‘great urban revolution of Venezuela’ (Friedman Citation1966) rapidly transformed Caracas in few decades, attracting new residents. The modernization of the capital was most visible during the Pérez-Jiménez period (1952–1958). Caracas used to be considered an unimportant Latin American capital during the first decades of the twentieth century. But the huge revenues coming from the oil trade produced an intense urban growth that completely transformed the city’s built environment, providing it with a new and modern face, crossed by wide motorways without comparison in Latin America (Almandoz Citation2012).

But while most Latin American capitals prospered in this period of economic growth, the interior regions did not follow the same development path. Consequently, during the 1950s and 1960s, most countries made efforts to stimulate the development of their regions, still suffering from poverty, high unemployment, low levels of education, and scarcity of services and infrastructure. The most important mechanisms for a more balanced spatial distribution of development implemented in Latin America were: (1) regionalization processes, or the division of the country into geo-economic regions; (2) creation of autonomous regional agencies; (3) establishment of transfer mechanisms; (4) creation of growth poles; and (5) creation of metropolitan agencies (Neyra Citation1974).

Regional development ideas were closely related to the ideas industrial development and economic developmentalism embraced by the governments of the time. Industrialization through regional planning was part of the modernization theory, which included growth poles as a way to realize such objectives. The concept of growth poles assumed that national and regional spatial equilibrium required concentrated investments to promote industrialization processes in less developed places (Irazábal Citation2004). The concept became very popular during the late 1950s, claiming that such poles could modify their regional environment and, if they were powerful enough, they could transform the whole national economy. Important examples in Latin America include Monterrey in Mexico, Concepción in Chile, Recóncavo Baiano in Brazil and Ciudad Guayana in Venezuela (Neyra Citation1974). Friedman (Citation1966) published about the topic with Venezuela as case-study.

Among the Anglo Saxon CIAM academics that frequently travelled to Latin America, regional planning was becoming increasingly important too. Regional planning was viewed as a new technique, more able to promote the much-needed economic development. This widening of the territorial scope of the planning profession, from cities into regions, produced a change in the urban terminology. The term ‘urbanismo’ – with an emphasis on physical planning and mostly relying on urban design – was gradually replaced by the term planificación (planning) – with an emphasis on planning procedures and mostly considering social, economic and cultural aspects. This transition from urbanismo into planificación coincided with the transition from the European cultural and technological dominance into the United States dominance (Almandoz Citation2010).

Such planning ideas circulated in Venezuela in the 1940s and especially the 1950s, influenced by Jose Luis Sert, Robert Moses, Francis Violich and Maurice Rotival, who became advisers of the National Planning Commission, established during the Pérez-Jiménez administration (Almandoz Citation2010). In this context, President Betancourt, elected in 1959, initiated a national economic development plan to decentralize Venezuela and to strengthen its economy, to make it less dependent on the oil trade, whose price began to decrease at that time. Regional planning became an important tool for the development of the Guayana, a region rich in natural resources, which would provide an important economic impulse to national development, encouraging ‘urban development in the south and reliev(ing) growth pressures in the north’ (Angotti Citation2001, 333). Guayana’s privileged location at the confluence of the Orinoco and Caroní rivers, provided good transportation facilities for export (see ). The Guayana area also was remarkably rich in resources which potentially could support many different new industries within the area (Snyder Citation1963).

In 1960, the Venezuelan government created two mechanisms to promote the development of the Guayana region: an autonomous regional agency, the Corporación Venezolana de Guayana (CVG) with ample powers and funds; and Ciudad Guayana, as a new town and growth pole that would stimulate industrial development. The new town was supposed to become the industrial capital of the country, and a comparison was easily made with the recently built Brasilia (Almandoz Citation2016). As a strategic element in the scheme of national economic development through import substitution industrialization, Ciudad Guayana would lay the foundation for a more diverse economy in Venezuela. These ideas and assumptions were features of the developmentalist agenda of the post-war period, in which Latin America governments had a leading role in nation building taking advantage of the benefits of economic growth and social progress (Angotti Citation2001). For the national government, Ciudad Guayana was essentially an economic endeavour (Peattie Citation1987; Angotti Citation2001; Irazábal Citation2004), which brought about high expectations: the new city would have a pivotal role in the compositional and geographical restructuring of the Venezuelan economy.

As responsible for the development of Ciudad Guyana, the CVG bought large extensions of land around the future new town, from private owners and by transfer from other government agencies (Angotti Citation2001). The CVG would also build important infrastructural projects: a steel plant of considerable dimensions in Mantanzas; two hydroelectric plants that would be able to meet the energy needs of half the country – the Macagua hydroelectric dam to be built on the Caroní falls and the Guri Dam, built a few kilometres further on the Caroní river – and an aluminium plant (Neyra Citation1974).

4. The planning process: planning dilemmas of an urban laboratory

An urban planner (Snyder Citation1963) writing about Ciudad Guayana during its planning process mentioned that it could be considered a laboratory where different planning approaches would be tested during implementation. Its comprehensive orientation, both at city and regional level, would create a singular opportunity to document the experiences and experiments stemming from the planning and implementation processes. These could be later evaluated to draw lessons to tackle similar situations in other parts of the Latin American region and even of the developing world.

Indeed, the collaboration between the CVG with the Joint Center, created a situation where expertise and knowledge about urban planning and urban development could be exchanged, examined, tested and applied. Its laboratory status was enhanced by the knowledge and experience of the international network of experts involved in the planning and development of Ciudad Guayana. Specialists in economics, urban planning and design, housing, and anthropology from the network of the Joint Center were requested to share their thoughts, findings, criticism and recommendations, what led to large discussions and debate, and contributed to the planning process. In the archives of MIT and Harvard extensive correspondence can be found from these experts, such as housing experts Charles Abrams and Rafael Corrada, and urbanist Kevin Lynch. Their observations and findings reflect the search and sometimes struggle to find a suitable planning and design approach for a fast-growing new town like Ciudad Guayana.

The following subsections illustrate the debates related to four important challenges of planning Ciudad Guayana: (1) how to properly accommodate the technical staff and the poor rural migrants in the new town; (2) how to deal with welfare issues in such a segregated society; (3) how to effectively adapt the plans to the actual urban circumstances of a developing country; and (4) how to deal with the pressures of short-term urgent matters.

4.1. Inclusive versus segregated design concepts

The great differences between the CVG and the Joint Center can be clearly illustrated by the different visions held by the teams’ leaders. Lloyd Rodwin, who led the Joint Center, endorsed the role of the planner as a social reformer, which considered essential to give attention to social and economic aspects in the planning process (Peattie Citation1987). On the other hand, Alfonso Ravard was a military appointed by the national government to lead the CVG, who clearly held a technocratic planning approach to promote the economic growth of the Guayana region, expressing the views of the Venezuelan political elite at that time (Irazábal Citation2004).

Rodwin emphasized the necessity of a multidisciplinary team to be able to deal with all aspects of planning and design for an inclusive development. According to him, Ravard’s main target was merely ‘fostering the economic growth of the region and especially encouraging enterprises that could compete in international markets’ (Rodwin and Associates Citation1969, 473), a vision which he considered inadequate for inclusive urban development (Peattie Citation1987). Such differences in visions and goals led to a difficult relationship between the team members of the Joint Center and of the CVG, although opinions were always respected and dialogue was sought to find solutions (Rodwin and Associates Citation1969).

A concrete planning challenge for Ciudad Guayana was to accommodate two very distinct groups: the technical elite – necessary to lead and operate the extensive variety of manufacturing industries – and the poor and unskilled population groups – who inevitably would migrate from poor rural areas. To be able to perform its role in regional and national development, the CVG emphasised a blue-print technical planning approach to especially attract the elite of engineers and technical staff to secure the industrial development of the city (Porter Citation2011). For this goal, Ciudad Guayana had to represent physically the ideas of progress and modernity linked to the American way of life.

The Joint Center planners, on the other hand, emphasised an inclusive city by encouraging a mix of income groups throughout the city. Its proposal for urban design was directed to improve liveability and generate a sense of community in the local context of economic competition and class conflict (Peattie Citation1987). But their desires to promote some social class mixture could not be met, and they eventually gave in to the goals of the CVG to shape the image of Ciudad Guayana as a modern city, which would be able to attract the desired capital and type of people through the collaborating with the segregation of low-income people in the city (Irazábal Citation2004).

4.2. Economic versus social goals

Another important challenge was the different view on the idea of modernization and progress held by the engineers and economists of the CVG and the foreign planners. Consequently, the CVG and the Joint Center planners held very different approaches towards welfare aspects of Ciudad Guayana. The former were seriously committed to develop the region through the implementation of large technical projects, such as the Guri Dam, and believed that the social ideas of the planners were unrealistic and unpractical (Irazábal Citation2004).

This clash between economic and social goals can be illustrated with the example of housing. The Joint Center considered access to affordable housing an essential welfare aspect for Ciudad Guayana residents. An inclusive housing policy was considered necessary, so the team elaborated a housing programme for all income groups (Corrada Citation1965). The housing programme integrated a community and a financial programme, seeking to make housing affordable, to stimulate the community and to make the necessary financial provisions. A ‘settlement strategy’ was developed, with ‘demonstration projects’ that were conducted for all income groups as prototypes for future residential areas. Corrada (Citation1965) stated that ‘the first housing program that Ciudad Guayana required was one of reception, progressive urban development and rehabilitation’ (Citation1965, 9). For the very poor households, Abrams (Citation1964) pragmatically recommended to allocate a specific area and support them in building their homes, under the understanding that this was not the ideal solution but that such planned slums would produce better housing than unplanned ones.

The CVG understood the importance of housing but regarded it as its responsibility only if it benefited the higher goal of economic growth. Despite the high housing demand, it did not want to get directly involved in the housing sector, hoping private developers or other public agencies would take over the task, although they were willing to facilitate and assist it. The CVG supported the housing programme by providing land to build housing projects and facilitating other related housing matters. But it was ambiguous about integrating different income groups, especially in the new developments in the western part of the city, where the industries were located.

However, some interesting housing experiments were successful achieving some level of inclusiveness at neighbourhood level, as the ‘demonstration project’ El Roble Pilot Project, prepared to tackle the growing housing demand. The programme followed an aided self-help strategy, with a ‘sites and services’ model combining governmental support with self-organization and progressive development. A lay-out of plots (sites) that provided space for services was offered to lower-income households to build their houses by themselves in a progressive way. Further, the urbanization process was planned and monitored, using a planning model based on progressive urbanization principles. In contrast to many failed outcomes, this pilot programme was rather successful, and its lessons were included in the comprehensive planning of the city. From the 1000 programmed lots for this progressive urban development scheme, 886 were realized in 1964.

4.3. Planning on-site versus off-site

The workplace of the teams was another point of discussion. Most of the Joint Center team considered that besides planning and design knowledge and expertise, understanding the location and taking into account the needs and desires of its (future) inhabitants was essential for planning the city. Lynch (Citation1964) recommended that the design of Ciudad Guayana had to be site-specific, what could be best achieved by working on the site; and that planning had to be flexible for constant adjustments, to facilitate planning implementation. Lynch’s recommendations emphasised ‘on-site design’, ‘continuous design’, ‘long-run future form’ and ‘near-future form’.

On the other hand, Von Moltke (Citation1969), head of urban design of the Joint Center, believed that for the development of a master plan and a long-term strategy it was necessary to be at a distance from the location. But once this process was completed, the design-team would have to move to the location, so the plans and projects could be matched with the needs and wishes of the inhabitants and with the reality of daily life.

Nevertheless, the Guayana programme was part of the central government and therefore the CVG was located in Caracas. Although the Joint Center did not agree with this situation, its members stayed in Caracas, because of poor communication and poor facilities on the site during the initial period. At a later stage, however, it proved difficult to move to the site. Anthropologist Lisa Peattie was one of the few members of the Joint Center team that lived on the site from the start. Her role has been essential to explain and understand the planning and design process of Ciudad Guayana, as well as the role of the different stakeholders. From the start, she emphasised the importance of considering the needs and desires of the population, specifically the lower-income groups, emphasizing the need of planning on-site. And from the start one was aware of the fact that next to housing the technical elite also the lower classes needed to be accommodated, but the rapid pace of urbanization apparently surprised the Joint Center.

Peattie’s view deeply clashed with the ones of the teams in Caracas, and in particular of the CVG, which stated that the lower-income groups were a problem and they simply needed appropriate housing. Such perspective on housing was dominant within policy circles, media and public opinion during that time, which considered the precarious neighbourhoods rapidly growing in cities of the developing world as misery belts, places of delinquency and social breakdown (Hall Citation2002). However, Peattie (Citation1987) was promoting a more flexible and pro-active view on housing and urbanization, more centred on the needs of lower-income groups, and very much in line with innovative views about how to deal with (rapid) urbanization in developing countries.

At that time, new insights into the dynamics of informal urbanization was emerging in academic circles, following the pioneering work of Charles Abrams and especially of John Turner, based on his experience with barriadas in Peru. In his academic publications, Turner heavily criticized the conventional way of housing provision of existing policies, based on the ‘minimum modern standard’. He claimed that it was not suitable for low-income households living in ‘modernizing countries’ as it required too high costs, not only for them, but also for their respective governments. Instead of jeopardizing informal urbanization activities Turner advocated to support them (Turner Citation1967, Citation1968). Such shift required a new type of design and planning, much more pro-active to be able to accommodate progressive housing and urbanization processes.

4.4. Short- versus long-term planning concerns

Perhaps one of the most important challenges of the planning practice in developing countries is the pressure of short-term urgent matters versus the need to elaborate a comprehensive long-term planning strategy through a thoughtful diagnosis, something which demands time and resources hardly available. Ciudad Guayana was well provided with sufficient resources for such a planning strategy, but not with enough time. Consequently, the pressures of urgent matters began to complicate the planning process. One of the most urgent matters was the provision of housing. The housing demand has different origins. On the one hand, it was coming from people displaced from an area that would be flooded by the construction of the Guri Dam, and on the other, from employees coming to work in the new industries. Furthermore, at that moment there were 5000 ranchos (precarious homes) which lacked services, and were dangerously constructed and overcrowded. The prognoses were if no adequate housing was built, 12,000 ranchos would cover the area, or an average of 2000 new ones per year. To tackle this, a pilot project was hastily prepared in El Roble for an estimated demand of 3500 dwellings, which began in 1962 (Corrada Citation1962).

The total population in Ciudad Guayana grew fast. In 1950 only 4000 inhabitants lived in the area and when the CVG and Joint Center started in 1961, it had grown to 42,000. The estimation was that the population would double in 1966 and this proved to be true. In 1998 Ciudad Guayana counted with 641,998 inhabitants, which grew to 877, 547 inhabitants in 2016 (UNData Citation2017)

From the beginning, it was evident that the multidisciplinary team in charge of planning Ciudad Guayana would embrace a planning strategy consistent with the rational comprehensive planning approach. This meant a coherent planning system framework and rules for measures to achieve both short and long-term objectives. However, as the growing local population demanded basic facilities such as infrastructure, sanitation, water and schools in the short-term, the corresponding projects had to begin immediately after the establishment of the planning process. Members of the Joint Center and some of the Venezuelan team refused to begin with these projects until proper knowledge of the local economic and socio-cultural aspects was obtained, to be able to prioritize the projects and link them to the main objectives. But the CVG wanted to build right away because such analyses would delay the whole process.

Rodwin and Associates (Citation1969) claimed that the risk of planning through projects – what he called adaptive planning – was that it could lead to a planning type in which the daily practice would dominate and the ad hoc results would be institutionalized. He, therefore, emphasized a planning process which could be responsive to short-term issues without neglecting planning for the long-term. However, as the external pressure to solve the short-term problems was growing, a compromise was made by the Joint Center. The result was a pragmatic planning approach that would lead to the immediate implementation of the projects ‘The most accurate answer would be a combination of comprehensive and adaptive styles’ (Rodwin Citation1969, 488). In a period of one-and-a-half years, several small-area plans were elaborated and implemented. Basic analyses were done and several experiments were initiated, which eventually would provide lessons for the planning process. After this intense period, the team was able to focus on the long-term issues carrying out thorough studies of the local context, the physical, economic and socio-cultural aspects of the region, as a first step to elaborate a comprehensive plan for Ciudad Guayana. Due to this delay, its master plan could only be adopted in 1964.

5. The planning product: the 1964 master plan

While the first experiments were executed and studies were under way, the team of planners prepared different versions of a masterplan for Ciudad Guayana, which followed the results of the debates and discussions of the teams. Eventually, the head of urban designers, Von Moltke, decided that the 1964 version should be regarded as the definitive ‘comprehensive physical plan for Ciudad Guayana’ (Von Moltke Citation1969, 138). According to the planners of the Joint Centre, the main objective of this zoning-plan was to create the conditions that would foster economic growth, while retaining a high standard of design that would serve as a model for developments elsewhere. Further, the plan had to be versatile enough to ensure the orderly distribution of future settlements and to meet the needs of the residents (Rodwin Citation1969).

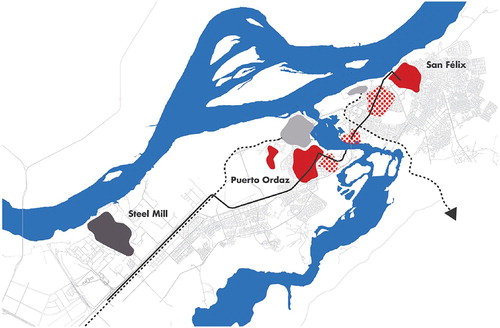

The master plan for Ciudad Guayana was the typical plan of a ‘modernist city’ such as Brasilia (Holston Citation1989), with a strict separation of functions. But there was a big difference from Brasilia: the area designated for the new town was not a tabula rasa. Nearly 30,000 people were living there at that time in two settlements separated by the Caroní river (see ). Most of them were living at San Felix, originally a fishing village located at the Orinoco riverside. The several mining projects in the region had attracted many new residents after the discovery of iron in the 1940s. Most migrants settled in San Felix, which grew in a few years from 1500–24,000 inhabitants (Appleyard Citation1976). Further, another settlement called El Roble was formed along the main road close to San Felix.

Figure 2. Location of original settlements in Ciudad Guayana. Source: Avella (Citation2017).

At the other side of the Caroní river there was Puerto Ordaz, a company town of 6000 inhabitants. This town was planned and designed by Jose Luis Sert, a prominent CIAM figure for the Orinoco Mining Company, which extracted iron from Cerro Bolivar. As a typical company town in developing countries, Puerto Ordaz had clearly segregated neighbourhoods and facilities for the North American staff – who had access to a large ‘country club’ – and the local workers.

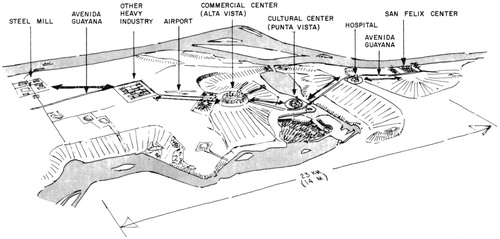

In such a geographical and physical context, a proper link between the existing settlements was a design imperative. This led to a master plan whose dominant feature was an infrastructure backbone connecting San Felix and Puerto Ordaz, which continued towards the industrial areas of the Iron Mining Company and Orinoco Mining Company located at the west. The planned residential areas and their respective commercial and cultural centres were located around the existing settlements (see ).

Figure 3. The comprehensive physical concept for the city of Ciudad Guayana, 1964. Source: Von Moltke (Citation1969, 139).

The infrastructural spine, Avenida Guayana, connected the steel mill industrial area at the west side with the airport, the Altavista commercial centre and residential areas of San Felix, the Punta Vista cultural centre, and crossing the Caroni River with the hospital and San Felix centre at the east side. The plan also envisioned residential areas adjacent to the existing settlements of Puerto Ordaz and Castillito at the west and El Roble and San Felix at the east. The Alta Vista commercial centre was located on the western plateau because of its good accessibility and its visual connection with the valleys at both sides of the river. The most beautiful natural area of the city, near the bridge and the natural parks, was chosen for the Punta Vista cultural centre (Von Moltke Citation1969).

With employment on the west side and the concentration of housing at the east side, transportation was one of the most important planning issues. A rapid-transit system was considered too expensive, so in the context of oil-rich Venezuela, it was decided that transport would be by private cars, taxis, buses and the local ‘por puestos’. This led to a car-oriented city, that functions along a transport corridor, Avenida Guayana, connecting the residential areas, the commercial and cultural centres and the industrial areas (Von Moltke Citation1969, 137–139).

One of the goals of the master plan was to provide housing for the residents closer to their work, in most cases the industry at the west end of the city. Yet most people settled near San Felix. Despite the planners attempts to create socially mixed new residential neighbourhoods, homogenous neighbourhoods arose on the Puerto Ordaz because the CVG encouraged higher and middle class to move there (Corrada Citation1962, Citation1965). In such way, the natural separation of the river became also the division between rich and poor, which is one of the main reasons why the process is generally considered as failed.

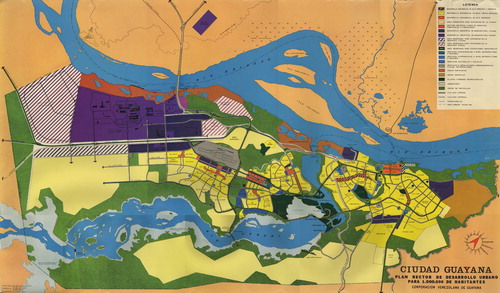

Although the basic elements of the 1964 plan were maintained for several years, it experienced important adjustments almost from the start (Peattie Citation1987). These adjustments reflected the results from the studies about the economic, social, cultural and financial issues. On the other hand, the implementation of the different area plans, demanded repeated changes and adaptations of the masterplan. shows one version of the Master Plan for Urban Development of Ciudad Guayana planned for one million inhabitants.

6. Discussion

Ciudad Guayana stands among the most important examples of planning and building a new town in Latin America, realized under the idea of progress and modernization, which clearly benefited from the abundant resources coming from the oil industry. As many academics studying Ciudad Guayana have mentioned (Peattie Citation1987; Angotti Citation2001; Irazábal Citation2004), the city was essentially an economic effort of the national government for regional development: it was planned to perform an essential role in both the regional and national industrial development of Venezuela. Ciudad Guayana was also a way to show Venezuela as a modern and powerful nation in the eyes of the world at that particular moment.

The case of Ciudad Guayana shows many similarities with some of the recently planned and built satellite cities, high-tech spaces and new towns developed in Asia, Africa and the Middle East, conceived of by the respective national governments as ambitious attempts to diversify and innovate their economies, while showing the world their country’s achievements in the current world competition. In Africa, for example, such ‘urban fantasies’ project an image of modernity and that Africa is ‘rising’, while ignoring ‘the fact that at the moment, the bulk of the population in sub-Saharan Africa cities is extremely poor and living in informal settlements’ (Watson Citation2014).

New towns, growth poles and satellite cities implicitly have a strong relation with urban planning; they existed first as an utopian idea or a vision that needed to be planned and designed to be able to be realized. Many of such spaces were built all over the world during the post-war period, a period of relative economic prosperity and high demographic growth. However, few of them have been able to meet the utopian objectives of the planners. Nevertheless, they have been valuable tools that have given useful insights regarding different planning processes such as managing land use and the right to develop land, locating industrial areas, financing urban development, comprehensive planning aspects and environmental issues (Abrams Citation1964). This has also been the case in Ciudad Guayana, which thanks to the strong academic attention it attracted and the related publications that documented the planning experiences, it could also be considered a remarkable urban laboratory (Snyder Citation1963).

Such an ambitious project as Ciudad Guayana, evidently required the best possible experts to realize the idea in both an effective and an exceptional way, for which leading academics and planning experts from the Joint Center were hired by Venezuela. Their expertise was considered the best possible to give shape to a modern industrial city to attract capital and the required technical staff, during this period of abundant money flows and strong ties between the North American and Venezuelan governments.

The Ciudad Guayana plan, placed in its historical context, was a reformist attempt to create a new type of urban development in cities of Latin America (Angotti Citation2001). But the democratic and inclusive planning concepts and strategies that the Joint Center academics and planners advocated – with an emphasis on welfare provision, mixed residential land uses and participatory arrangements – were considered impractical, utopian and idealistic by the local counterpart. Eventually, the original planning intentions did not survive the clash and the economic-driven pressures and interests of powerful stakeholders would give shape to Ciudad Guayana’s urban development. The result is that Ciudad Guayana developed into a highly segregated city, which hardly differs from other cities of the region.

Irazábal (Citation2004) has argued that the type of planning used in Ciudad Guayana promoted the existing social and spatial inequalities of the city. Indeed, master plans and procedural planning may have contributed to shape and develop western cities in the past, but have proved to be very inefficient in the rapidly growing cities of developing countries, which obviously do not share the conditions in which such type of planning originated. Places with high levels of poverty, inequality and rapid growth have much more urgent and serious challenges to tackle, with a more complex nature and timing.

Furthermore, even before Ciudad Guayana was conceived of as a one city, it already existed as two very different towns – San Felix as a squatter area and Puerto Ordaz as a company town – with very contrasting social structures and cultural values. The Joint Center soon found out that its well-intentioned planning approach was not able to overcome the large division between these two existing settlements, as well as the problems associated to the socio-cultural conflicts and economic contrasts of the Guayana region. The informal response to the promise of the new city occurred so fast that it overwhelmed the planners: ‘Some twenty thousand squatters in 1962 lived in the projected steel city of Ciudad Guayana, even when it was being planned and when the steel plant was providing only a thousand jobs’ (Abrams Citation1964, 18).

In the end, what happened in the case of Ciudad Guayana, was no different to what happened to Brasilia (Holston Citation1989), and many other centrally planned towns and cities in developing countries. Even if the experience has been considered by many as failed, Ciudad Guayana has provided important lessons for planning efforts elsewhere:

To avoid the problems linked to urban segregation, planning should strive for an inclusive kind of city that takes into account the needs and demands of all social groups, instead of focusing on the demands of higher-income groups. Facilitating the participation of all urban actors in planning processes, including community organizations and marginalized groups, is a key requirement to effectively improve the urban conditions. This lesson is especially relevant for the current type of privately led new town projects being built in the Global South, whose developers tend to favour privileged groups. ‘The consumptive and supply-driven character of many new city projects, their insertion into complex “rurban” spaces with even more complex land governance arrangements and their tendency to implement post-democratic, private-sector-driven governance will make them at best unsuitable for solving any of the main urban problems Africa is facing an at worst they will increase expulsions and enclosures of the poor, public funding and social spatial segregation and fragmentation’ (Van Noorloos and Kloosterboer Citation2018, 1237).

The Joint Center emphasized the importance of comprehensive planning linking economic, social and spatial concerns, and used a multi-disciplinary team for these goals. However, the clash with the economic orientation of the CVG finished in the dominance of the latter views and goals. The main lesson here is that adequate instruments – capacity development, cooperation, mobilization of financial resources, political and legal frameworks – should be used to achieve a more equitable allocation and distribution of urban facilities and services. For example, the successfully applied aided self-help policy in Ciudad Guayana, and especially the sites and services model should be revisited within the contemporary debate on new towns.

From the consequences of the planning on-site versus off-site struggle, it became evident that even the best and well-intentioned planning experts may not be sufficiently aware of the local circumstances from afar. New towns and their related urban visions cannot be developed by means of blue-prints or abstract planning models, as they are linked to distinctive local, regional and national contexts. Careful awareness of the local cultural features and of the socio-economic conditions of the population, is indispensable for effective planning.

Finally, the issues related to the urgent versus long-term planning concerns, have pointed out that a strong focus on implementation becomes highly important in the type of contexts of high complexity, rapid change, and uncertainty characteristic of cities in developing countries. New towns in contexts of high levels of complexity require adaptive and flexible instruments that are able to link the many urban actors and a wide variety of means.

The lessons coming from the original planning of Ciudad Guayana clearly coincide with the recently embraced planning guidelines of the New Urban Agenda (United Nations Citation2017), expressed in the commitments for social inclusion, urban prosperity and opportunities for all, and sustainable and resilient urban development. The Ciudad Guayana planning experience can be considered as a useful urban laboratory which helped to make clear that even progressive and thoughtful planning concepts for new towns cannot succeed without taking proper consideration of the future inhabitants and their societal circumstances, even if there are enough financial means to realize the plans. This verifies that ‘planning cannot create the preconditions for its own success’ (Wildavsky Citation1972, 508).

7. Conclusion

This paper has provided significant insights about the planning dilemmas and challenges of building a new town in a country of the Global South with enough financial resources, but with a highly unequal society. The examination of four related challenges that the planners had to deal with during the planning process has been useful to highlight the limits of the transfer of international concepts, models and strategies to develop new towns in sites of high complexity. Its lessons show that even the most knowledgeable planning experts’ intentions can produce unintended and unsuccessful planning results. The awareness of the local cultural features and of the socio-economic situation of the future population is indispensable, but not enough to produce successful new towns. To achieve a more equitable allocation and distribution of urban facilities and services planning instruments should be tailor made to include stakeholder engagement, capacity development, and a fair mobilization of financial resources.

The planning of Ciudad Guayana can be considered in a contrasting perspective. In the perception of Venezuelans, it fulfilled its role as a successful industrial growth pole in the country development (Cabello Citation2015). The impact of Ciudad Guayana in Venezuela was indeed significant, turning the Guayana region from a rather sleepy region into an important industrial hub with an active inner port (Correa Citation2016). But taking into account the socio-spatial aspects, Ciudad Guayana has often been described as a failed urban experiment. This has been attributed to a too ambitious approach based on utopian views; a design approach based on modernistic ideas of segregation of functions; priority given to road infrastructure; and an unsuccessful spatial form that promoted segregation.

The case of Ciudad Guayana is important because it has had an important place in the Latin American urban studies, as it became an important reference for national planning strategies across Latin America, exerting a significance influence across multiple scales and arenas of regional planning in South America (Correa Citation2016). One of its most positive effects was the dissemination of the disciplines of urban and regional planning as useful and innovative tools for socio-spatial change in the context of the economy-driven societies in the region during that period. ‘In those decades of US-backed developmentalism, Latin America’s transition from urbanismo into planificación and planeamento adopted techniques and ambits drawn from regional planning’ (Almandoz Citation2016, 33).

Other fruitful and inspiring elements of the planning and building of Ciudad Guayana have been the thoroughly devised housing experiments developed and implemented to test different planning approaches. El Roble Pilot Project is an illustrative example of such attempts to humanize the planning process finding ways to bring formal and informal building processes together. Ciudad Guayana promoted a more progressive attitude towards squatter settlements which led to inclusionary alternative strategies for informal settlements that still have a considerable influence in contemporary Latin American urbanism. ‘Recent successful experiments in the transformation of squatter settlements as Quinta Monroy in Iquique by Elemental have used approaches similar to those in El Roble’ (Correa Citation2016, 108).

Seen in the spirit of the time, the unique collaboration of the Joint Center and the CVG, added valuable knowledge and experience to the urban laboratory of Ciudad Guayana during a crucial turning point in the international discourse on urban planning. In

its historical context, it was a path-breaking effort, a progressive attempt to create an alternative to the impoverished, dependent metropolis then common in Latin America. The rational comprehensive planning model was a necessary accompaniment to the massive government investments in industry. Without a sizable comprehensive planning effort, these investments could have been compromised. (Angotti Citation2001, 330)

Another turning point is taking place in the current urban discourse, in which urban planning and design have acquired a fundamental role to respond to the fast-growing urbanization processes of the Global South. Ciudad Guayana is still a valuable source for useful lessons to achieve more inclusive and sustainable cities, with affordable housing for everybody.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Abrams, Charles. 1964. Man’s Struggle for Shelter in an Urbanizing World. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Almandoz, A. 2010. “From Urban to Regional Planning in Latin America, 1920–50.” Planning Perspectives 25 (1): 87–95. doi: 10.1080/02665430903515840

- Almandoz, Arturo. 2012. “Caracas, entre la ciudad guzmancista y la metrópoli revolucionaria.” In Caracas, de la metrópoli súbita a la meca roja, edited by A. Almandoz, 9–25. Quito: OLACCHI.

- Almandoz, Arturo. 2016. “Towards Brasilia and Ciudad Guayana: Development, Urban Design and Regional Planning in Latin America 1940–1960.” Planning Perspectives 31 (1): 31–53. doi: 10.1080/02665433.2015.1006664

- Angotti, Thomas. 2001. “Ciudad Guayana from Growth Pole to Metropolis.” Central Planning to Participation. Journal of Planning Education and Research 20 (3): 329–338. doi: 10.1177/0739456X0102000305

- Appleyard, Donald. 1976. Planning a Pluralist City: Conflicting Realities in Ciudad Guayana. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Avella, Ricardo. 2017. https://www.academia.edu/39780480/Ciudad_Guayana_a_planned_growth_pole_on_the_Orinoco._A_critical_assessment_on_the_role_of_spatial_planning.

- Cabello, Maria de los Angeles. 2015. Ciudad Guayana: de milagro de planificación a ejemplo de destrucción. July 3. http://elestimulo.com/climax/ciudad-guayana-milagro-de-planificacion-a-ejemplo-de-destruccion/.

- Corrada, Rafael. 1962. EL Roble Pilot Project, Division of Studies, Planning and Investigation. Archives Joint Center for Urban Studies at MIT, Records of the Guayana Project, 1961–1969, Archival Collection–AC 292, file B-43.

- Corrada, Rafael. 1965. A Housing Policy for Ciudad Guayana, Stafworking Paper, CVG, Division of Studies, Planning and Investigation, from Frances Loeb Library at the Special Collection Department of Harvard Graduate School of Design, file F-56.

- Correa, Felipe. 2016. Beyond the City, Resource Attraction Urbanism in South America. Austin: The University of Texas Press.

- Friedman, John. 1966. Regional Development Policy: A Case Study of Venezuela . Vol. 279. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Hall, Peter. 2002. Cities of Tomorrow: An Intellectual History of Urban Planning and Design in the Twentieth Century. 3rd ed. London: Blackwell Publishing.

- Holston, James. 1989. The Modernist City: An Anthropological Critique of Brasilia. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

- Irazábal, Clara. 2004. “A Planned City Comes of Age, Rethinking Ciudad Guayana Today.” Journal of Latin American Geography 3 (1): 22–51. doi: 10.1353/lag.2005.0006

- Kahatt, Sharif S. 2011. “Agrupación Espacio and the CIAM Peru Group: Architecture and the City in the Peruvian Modern Project.” In Third World Modernism: Architecture, Development and Identity, edited by D. Lu, 85–110. New York: Routledge.

- Lu, Duanfang. 2011. “Introduction: Architecture, Modernity and Identity in the Third World.” In Third World Modernism: Architecture, Development and Identity, edited by D. Lu, 1–28. New York: Routledge.

- Lynch, Kevin. 1964. Some Notes on the Design of Ciudad Guayana. Archives Joint Center for Urban Studies at MIT, Records of the Guayana Project, 1961–1969, Archival Collection–AC 292.

- Neyra, Eduardo. 1974. Las Políticas de Desarrollo regional en América Latina. Document for the International Seminar on Urban and Regional Planning, Viña del Mar, 17–22 April 1972.

- Peattie, Lisa. 1987. Planning: Rethinking Ciudad Guayana. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Porter, William L. 2011. Professional Transformations. https://issuu.com/wlymanporter/docs/porter-duttachapter.

- Rodwin, Lloyd. 1969. “Reflections on Collaborative Planning.” In Planning Urban Growth and Regional Development: The Experience of the Guayana Program of Venezuela, edited by Lloyd Rodwin, 467–491. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Rodwin, Lloyd, and Associates. 1969. Planning Urban Growth and Regional Development: The Experience of the Guayana Program of Venezuela. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Snyder, David E. 1963. “Ciudad Guayana: A Planned Metropolis on the Orinoco.” Journal of Inter-American Studies 5 (3): 405–412. doi: 10.2307/165135

- Taylor, Nigel. 1999. “Anglo-American Town Planning Theory Since 1945: Three Significant Developments but No Paradigm Shifts.” Planning Perspectives 14 (4): 327–345. doi: 10.1080/026654399364166

- Turner, John C. 1967. “Barriers and Channels for Housing Development in Modernizing Countries.” Journal of the American Institute of Planners 33 (3): 167–181. doi: 10.1080/01944366708977912

- Turner, John, F. C. 1968. “Housing Priorities, Settlement Patterns and Urban Development in Modernizing Countries.” Journal of the American Planning Association 34 (6): 354–363.

- UNData. 2017. UNData. A World of Information. http://data.un.org/.

- United Nations. 2017. New Urban Agenda. Habitat III Secretariat.

- Van Noorloos, Femke, and Marjan Kloosterboer. 2018. “Africa’s New Cities: The Contested Future of Urbanisation.” Urban Studies 55 (6): 1223–1241. doi: 10.1177/0042098017700574

- Von Moltke, Willo. 1969. “The Evolution of the Linear Form.” In Planning Urban Growth and Regional Development. The Experience of the Guayana Program of Venezuela, edited by Loyd Rodwin, 126–146. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Watson, Vanessa. 2014. “African Urban Fantasies: Dreams or Nightmares?” Environment and Urbanization 26 (1): 215–231. doi: 10.1177/0956247813513705

- Wildavsky, Aaron. 1972. “Why Planning Fails in Nepal.” Administrative Science Quarterly 17, 508–528. doi: 10.2307/2393830

- Interview with Victor Artis, member of the CVG team, May 20, 2009.

- Interview with William Porter, member of the Joint Center team, September 14, 2011.