ABSTRACT

Demand for land planning and surveying services has increased significantly over the years in Tanzania and as a result, the public sector has not been able to cope. Private firms have therefore emerged to provide land use planning and surveying services for landholders in peri-urban areas, most of whom have accessed land through the informal sector. This paper explores the experiences of private firms in delivering land use planning and surveying services in peri-urban areas of Dar es Salaam City. Using a case study approach involving in-depth interviews, focus group discussions and document analysis, the study reveals that private firms face legal, policy and technical obstacles in land service delivery. Despite these challenges, private firms have been instrumental in facilitating the regularisation of informally accessed land. Supportive policies and other institutional reforms are deemed necessary to improve the delivery of land services and strengthen the participation of private firms.

1. Introduction

Land services such as land use planning and surveying are crucial for land development and sustainable city growth. These services are in great demand in African cities due to rapid urbanization (Mweti Citation2013; Jones, Cummings, and Nixon Citation2014; Transparency International Citation2017; Smit Citation2018). Although it is the responsibility of the state to deliver public services, the private sector also supplements government efforts (Birner Citation2007; Transparency International Citation2017). Through public–private partnerships, governments in Africa have enabled the private sector to participate in the delivery of municipal services because of insufficient state capacity to meet citizens’ needs (Nyadimo Citation2006; Kalabamu and Lyamuya Citation2017; Van Noorloos and Kloosterboer Citation2018). Smit (Citation2018) acknowledges that in most African cities the private sector plays a big role in urban governance, transforming cities by investing in land development projects. However, this sector is faced by various governance challenges such as inadequate enforcement of laws, skills shortage and unfriendly labour regulations (Altenburg and von Drachenfels Citation2008). These challenges differ not only in terms of extent, but also from one country to another, or from sector to sector.

Like most developing countries, Tanzania is facing rapid urbanization due to high birth rates and sustained rural–urban migration (Kombe Citation2001; Mkalawa and Haixiao Citation2014; Wenban-Smith Citation2015; Farrell Citation2017; Nuhu Citation2018). This affects the development and transformation of cities significantly. Dar es Salaam, is the largest commercial city in Tanzania (Mkalawa and Haixiao Citation2014; Stina, Amelia, and Joshua Citation2018). It is estimated that the city has more than 6 million people which is one of the highest in Sub-Saharan Africa (World Population Review Citation2020). Partly as a result of limited public resources, urban land use planning capacity has been incommensurate with peri-urban growth: current demand for planned and surveyed plots outstrips the city authorities’ ability to deliver land services (UN-Habitat Citation2016; Kasala and Burra Citation2016; Makundi Citation2017). This has led to widespread modes of informal land access that attempt to fill gaps created by shortfalls in the formal land delivery system. The situation is likely to get more serious, given the projected annual population growth rates of about 8 percent and over 9 percent for 2020 and 2025 respectively (URT Citation2012; Agwanda and Amani Citation2014).

In an attempt to address the problem of high unmet demand for planned and surveyed land in Dar es Salaam, the Tanzanian government has, over the years, initiated various projects. In the 1970s and 1980s, it established the Sites and Services Schemes with support from the World Bank (Kironde Citation1997; Hossain, Scholz, and Baumgart Citation2015). Project costs amounted to USD 7000 million, with 59 and 41 percent from the World Bank and the government respectively (Abwe Citation2009). The project was implemented by the Ministry of Lands, Housing and Human Settlements Development (MLHHSD), in partnership with the World Bank. The World Bank also funded another project from 1977 to 1981 for surveying and servicing 3000 plots in peri-urban areas of Dar es Salaam, with the aim of helping low income earners to access land (Abwe Citation2009; Hossain, Scholz, and Baumgart Citation2015). In 2003, MLHHSD initiated the 20,000 Plots Project aimed at reducing the shortage of planned and surveyed urban plots, controlling the proliferation of informal settlements and improving urban land governance in the city (Kironde Citation2015).

Studies reveal that these initiatives have not only failed to cope with the increasing demand for planned and surveyed plots, but they have also benefited mainly the middle and high income households (Kironde Citation2015; Kulaba Citation2019). In most of these projects, private sector actors were not effectively involved, despite the fact that there were supportive policies in place at the time. Section 5 of the National Land Policy of 1995 provides that certified private planners and surveyors (private firms) can participate in delivering planning and surveying services. The National Human Settlements Policy (URT Citation2000), Section 3, also emphasizes the participation of the private sector in human settlement development, as the public sector does not have capacity to meet the growing demand. In practice, however, the government seems to have undervalued the contribution of private firms in delivering land use planning and surveying services in spite of the supportive legal and policy environment.

After the enactment of the Urban Planning Act of 2007, the government of Tanzania encouraged more avidly the participation of the private sector in delivering land services. These services include planning and surveying to meet the increasing demand in peri-urban areas (Kasala and Burra Citation2016; Stina, Amelia, and Joshua Citation2018). Private firms are also actively participating in regularization and formalization of properties in informal areas. The major roles which private firms have played include: mobilizing resources especially finance, equipment and man power; identifying potential land for planning and purchasing; preparing land use layouts; carrying out cadastral surveys; and selling land (Magigi Citation2013; Kasala and Burra Citation2016; Makundi Citation2017; Babere and Ramadhani Citation2018; Stina, Amelia, and Joshua Citation2018). However, the process of delivering serviced land often encounters challenges such as an unregulated land market, politicization of land delivery, sporadic land use patterns especially in peri-urban areas, and inappropriate standard procedures for land use planning and surveying (Kironde Citation2009; Babere and Ramadhani Citation2018). There are also disputes between landholders and private planning firms (Babere and Ramadhani Citation2018).

For the purposes of this paper, the term ‘peri-urban’ refers to areas located beyond the consolidated urban areas. They are positioned between rural and consolidated urban areas, and are in the process of transitioning from rural to urban settings; they thus exhibit rapid growth emanating from sporadic parcelling of land. In most of these areas, more than 70 percent of the residents’ access land informally (Kombe Citation2005; Adam Citation2014; Nuhu Citation2018). Ongoing land development does not adhere to urban land use planning standards and regulations. Most of these peri-urban areas are hotspots where speculators and affluent seekers of land for housing are buying land through informal land markets (Kombe Citation2005, Citation2010; Nuhu Citation2018). In order to reserve land for essential public infrastructure services and boost the supply of planned and surveyed plots in these areas, both central and local governments have increasingly, over the last two decades, called upon the private sector to engage in land use planning activities. This paper explores the experiences of private firms in delivering land planning and surveying services in peri-urban areas in Dar es Salaam. Its findings can contribute to an understanding of the contribution of such firms in the land sector, and can inform efforts by the responsible authorities to improve land governance not only in Tanzania, but also in other countries in Sub-Saharan Africa with similar land access service systems.

The following section presents a brief review of literature regarding private sector engagement in delivering land services in Sub-Saharan Africa. The policy environment in which the private sector operates is then analysed in Section 3, while the methodological approaches adopted in the study are explained in Section 4. This is followed by a presentation of findings (see Section 5) and a discussion (see Section 6). The paper closes (see Section 7) with some conclusions and recommendations derived from the study.

2. Land governance and private sector participation in Sub-Saharan Africa

Urban land governance in Sub-Saharan African cities has been a dominant topic for both researchers and practitioners (e.g. Kironde Citation2000; Wehrmann Citation2008; El-hadj, Faye, and Geh Citation2018; Adam Citation2014, Citation2020). Cities and municipalities in this region are urbanizing rapidly and public land access processes are not meeting the demand for land services (Lwasa Citation2010; El-hadj, Faye, and Geh Citation2018; Adam Citation2020). Land markets in Sub-Saharan Africa are characterized by two parallel land supply systems; formal and informal (Gough and Yankson Citation2000; Nuhu Citation2018, Citation2019; Adam Citation2020). The formal land market is part of the statutory system, in which the state is responsible for providing rights to access and to develop land (Kombe and Kreibich Citation2006; Kombe Citation2010). As noted, this type of land market is less dominant in peri-urban areas, since it has failed to meet the ever-increasing demand there, leaving the informal land market to prevail in peri-urban areas. Informal land markets are driven by willing sellers and buyers (Gough and Yankson Citation2000; Kironde Citation2000; Wehrmann Citation2008). This willingness, together with constraints emanating from the formal government mechanisms, are driving forces for land markets to operate outside governmental authorities (Kironde Citation2000). Current land market trends are therefore dominated by the two alternative land markets (Nuhu Citation2018, Citation2019; Adam Citation2020), which are run by different actors and in different ways. In the formal system, actors are regulated and operate systematically in the provision of land services; actors in the informal system are not regulated and while they may operate systematically, their actions are often more haphazard. Moreover, informal systems are still developing, since they were not inherent in the traditional land access systems.

The imposition by the International Monetary Fund and World Bank of Structural Adjustment Programs in the 1980s and 1990s led most countries in Sub-Saharan Africa to adopt a market economy (Briggs and Mwamfupe Citation2000). Increasing populations also had an impact on land markets, leading many countries to undertake institutional changes to address the emerging challenges (Wehrmann Citation2008; Holden and Otsuka Citation2014; World Bank Citation2015). Institutional changes focused on participatory urban planning in order to provide opportunities for the engagement of other (groups of) actors in delivering land services, including the private sector and civil society. In Tanzania, for instance, the private sector was encouraged to complement government efforts in delivering land services (URT Citation1995, Citation2007). In Botswana, the government adopted a strategy for private sector participation in land servicing in 2014 (Kalabamu and Lyamuya Citation2017), while in Uganda, the national land policy of 2013 called for public–private partnerships to enhance tenure security in order to curb the growth of slums and informal settlements (UG Citation2013). Through such policy changes, the private sector was given a key role in facilitating urban land governance and city growth in Sub-Saharan Africa (El-hadj, Faye, and Geh Citation2018; Smit Citation2018; Adam Citation2020).

Various countries in this region have involved private agencies in urban land development (World Bank Citation2015). Kalabamu and Lyamuya (Citation2017), for instance, report that through participation of the private sector in Gaborone, the government of Botswana has delivered houses for rent and sale. In the Mathare 4A slum in Nairobi, public–private partnerships managed to upgrade and deliver basic services in the informal settlements through a pooling of resources (Otiso Citation2003). Land adjudication in some parts of Kenya was also done through partnerships with the private sector, reducing the backload of the state (Nyadimo Citation2006). In Rwanda, the private sector has been instrumental in the establishment of the cadastral system and slum upgrading through Entreprises de Construction et Aménagement Divers (El-hadj, Faye, and Geh Citation2018). Kasala and Burra (Citation2016) reveal that in Tanzania, the private sector has participated in delivering planned and serviced land, and has thus contributed to land development. These efforts from various countries indicate that the contribution of the private sector in urban land markets and governance in general is one that should not be underestimated.

Despite improvements and successes in providing planned and serviced land, public–private partnership arrangements raise a myriad of challenges including problems of profit maximization by the private sector, lack of common interests between the public and the private sector, as well as inadequate awareness and experience of local communities (Otiso Citation2003; Magigi Citation2013; Kasala and Burra Citation2016; Kalabamu and Lyamuya Citation2017; Mallik Citation2018). Regardless of the organizational and institutional challenges faced by private sector participation in the land sector, the partnership phenomenon has been spreading globally (UN Citation2008). The challenges faced by the private sector are however, not homogeneous: as a result, the private firms involved in facilitating the regularization of informally accessed land, and their response to varying situations, differ widely. In this context, understanding the regulatory and policy institutions that guide the implementation of activities of private firms offering land services is vital.

3. Legislative frameworks and private firms’ activities

The global context of regularization of informally accessed land includes the United Nations Conference on Human Settlement in Istanbul on the recognition of insecurity of tenure and poor infrastructure in unplanned areas, and the subsequent declaration on access to land and security of tenure as a condition for sustainable shelter and urban development (UN Citation1996). In 2016, the United National Assembly adopted resolution 71/256 of the New Urban Agenda. Among other things, the agenda calls for improvement of slums, tenure security and informal settlements through regularization (UN Citation2017). The Sustainable Development Goal target 11.3 calls for enhanced inclusive and sustainable urbanization and capacity for participatory integrated and sustainable human settlement planning and management in all countries by 2030 (UN Citation2015). The Agenda 2063 for Africa also underlines this ambition (Africa Union Commission Citation2015). This specific goal and commitment calls for the international community to address the chronic problem of insecure land tenure and property rights, particularly in the informal settlements of developing countries (UN Citation2015). In response to these global proclamations, Tanzania has put in place various policies to promote urban land use planning and surveying, with the support of the private sector. The participation of private firms in land use planning and surveying is underlined in the National Human Settlements Policy of 2000. Section 3 of the policy emphasizes the engagement of private sector actors and civil society organizations in planning, development and management of human settlements. The Urban Planning Act of 2007 designates three major actors in land use planning and surveying, namely, MLHHSD, the Regional Secretariat (RS) and the Local Government Authorities (LGAs) (URT Citation2007; Msale-Kweka Citation2017). Section 23 (2) of the Urban Planning Act (2007) provides that experts drawn from private firms or other professionals can be instructed to prepare land use planning schemes. However, in order to ensure adherence to planning regulations and standards, private firms have to be supervised by the respective planning authorities such as LGAs.

The Land Act of 1999 and the Urban Planning Act of 2007 both provide guidelines for delivering land planning and surveying services in developed or occupied peri-urban land (URT Citation1999, Citation2007). Section 60 of the Land Act outlines procedures for planning and surveying in areas undergoing regularization. Among other things, the law requires that schemes of regularization make arrangements for survey, adjudication of plots boundaries and consideration of the interests of landholders. Schemes of regularization are initiated by local communities themselves, with the help of local community leaders. Such schemes are expected to prioritize the participation of local communities particularly landholders and local community leaders in land service projects. Compensation procedures and valuation are also covered in the schemes (URT Citation1999). Although payment of prompt and fair compensation is theoretically mandatory, this provision is often impossible to apply when communities initiate the regularization process. The government abandons its obligations in this scenario to avoid costs and places the burden on the communities themselves. The communities may not be able to afford compensation for the affected members.

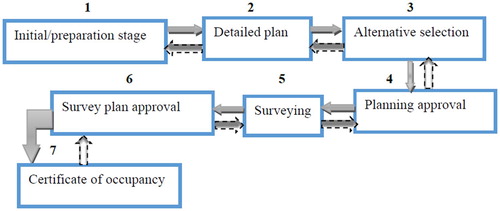

Municipal authorities have also issued directives to facilitate delivery of land use planning and surveying services by private firms. The directives support procedures provided in the Land Act of 1999 and the Urban Planning Act of 2007. As shown in , the Act and directive issued by the municipalities in land use planning and surveying provide for major activities or steps which ought to be adhered to by private firms, landholders and local community leaders involved in peri-urban land delivery activities.

The initial stage, whereby a private firm receives a letter from a local community (approved by the Ward Executive Officer [WEO]) requesting a firm to carry out a scheme of regularization in their area. The letter endorses the firm to implement land services in the area in question. The firm then prepares the draft plan of land use taking into account existing developments in the area including information on landholdings.

Stage 2: Private firms prepare detailed planning schemes using an updated base map. The plan has to show plot boundaries, plot sizes and locations, areas for public infrastructure services and other items.

Stage 3 provides for alternative selection involving the display of town planning drawings. The proposed plans (town planning drawings) are displayed at the local ward and sub-ward offices for public scrutiny or hearing. This stage offers an opportunity for landholders and local leaders to choose the best plan out of those presented.

Stage 4: The selected plan is submitted to the respective local government authorities – LGAs, RS and MLHHSD – after considering comments from the public hearing.

Step 5: The private land surveying firm conducts out a cadastral survey of the area based on the approved land use plan. The survey is done in accordance with the Land Survey Act Cap 324 of 1977 (URT, Citation1977).

Step 6 involves the submission of the survey plan for approval by the Director of Mapping and Surveys and Director of Physical Planning in MLHHSD.

Step 7 involves preparation of documents and certificates of occupancy or title deeds.

Figure 1. Land planning and surveying processes and steps involved. Source: The Urban Planning Act 2007, the Land Act 1999, Ubungo and Kinondoni Municipal directives documents.

As indicated in , the process is not linear; the dotted lines show that the processes may involve sending back the plans/drawings to an officer, or an office, which had previously submitted them if there are technical issues to be sorted out. These may include non-compliance with legal or administrative procedures.

4. Methods and materials

A case study approach was used to analyse the process of delivering land services – essentially planning and surveying by private firms in peri-urban areas in Dar es Salaam. The study focused on: (i) areas with high demand for planned and surveyed plots; (ii) areas which exhibit rapid consolidation or growth of informal land access; (iii) areas where unregulated land transactions, parcelling and development are increasing; and (iv) areas where land disputes have increased due to insecure tenure and property rights. The initial data were collected in the first quarter of 2018 and the second phase of data collection was conducted in September 2019, to provide additional information. Fourteen (14) face-to-face in-depth interviews were held with officials from the public and private sector bodies, as well as landholders. Officials were selected purposively taking into account their roles, responsibilities and experience in delivering land services. Interview questions focused on collecting information and opinions regarding the challenges encountered by private firms, the opportunities for exploitation by private firms, existing policies and the legal framework that guides private firms in delivering land (planning and surveying) services, and the level of community participation.

In order to understand the private firms’ role and operations in land service delivery, a list of thirty-eight (38) profiled firms was accessed from the MLHHSD. Three (3) private firms were purposively selected. The selected firms either had many years of experience in land service delivery, or were conducting ongoing land service activities in the community. From each private firm, one (1) official responsible for networking with communities and the government on land activities was interviewed. The MLHHSD official in charge of the master plan for Dar es Salaam city, was also interviewed. Two (2) officials from LGAs were interviewed because they are responsible for supervision of private firms’ activities in the community. A total of six (6) local leaders at ward and sub-ward levels, where private firms are delivering land services were also interviewed. These leaders are responsible for raising awareness on community participation in land planning activities and mobilization of communities’ fees for land service, and they sometimes engage in land transactions. Two (2) landholders were selected from community members who had been bypassed during the land use planning and surveying process in the area, in order to explore the circumstances surrounding their exclusion from the activity.

Three (3) focus group discussions (FGDs) with five (5) participants in each group were conducted, comprising individuals who had engaged in the formalization process of their land. These discussions stimulated the expression and sharing of opinions in a safe environment for community members, but also added to the information gathered from interviews. Document analysis was also applied in the study to understand the legal and institutional framework guiding the operations of private firms. Documents reviewed included the National Land Policy of 1995, the Land Act of 1999, the National Human Settlement Policy of 2000, the Urban Planning Act of 2007, the National Public–Private Partnership (PPPs) Policy of 2009 and other relevant documents. Data gathered were analysed through content analysis. Categorization and coding were applied to identify sub-themes, and related sub-themes which were combined to form major themes as explained and discussed in the subsequent sections.

5. Findings

This section presents the findings of the study with regard to the challenges faced by private firms which (may) hinder their smooth engagement. The significance of the participation of private firms in land service provision in peri-urban areas of Dar es Salaam is also highlighted.

5.1 Challenges for private firms in delivering land services

5.1.1 Procedural complexities

Land planning and surveying services in Tanzania are guided and regulated by several legal and policy frameworks as explained in Section 3. Participants from private firms reported that the procedures and processes they had to go through in order to meet the legal and policy requirements were tedious and time-consuming. The various steps and processes often entail physical visits to different public departments and offices, while decision making is sporadic; one cannot tell when decisions on certain issues or steps will be made. The process begins at sub-ward and ward levels, proceeds to municipal, regional office (RO) and finally to MLHHSD level. In some of these offices, several units or departments are involved. At MLHHSD, for instance, the approval process and preparation of a certificate of occupancy are handled by three different departments – Land Administration, Town and Rural Planning, and Surveys and Mapping. Within these departments, documents, paperwork and decisions are handled by different units. Similarly, titling and registration are normally initiated at the Municipal Land Office; the draft title is then submitted to the Commission of Lands for endorsement, after which it is sent to the office of the registrar for registration and issuance. After registration, it is sent back to the Municipal Land Office, where the client is required to collect the title. With so many different actors and sub-stages involved, officials from private firms complained that completing the process is costly in terms of both time and money; the problem is exacerbated when corrupt officials misuse their positions to get ‘incentives’ (in form of cash) from clients. Distrust can also be generated between firms and clients when expected services seem to be unduly delayed, or not efficiently delivered. Reflecting on this situation, an officer from one private firm stated:

Acquiring a permit from LGAs is a hectic process because of existing procedures … this has created conflicts between our firm and the communities because they expect their areas to be planned and surveyed in time. When this is not realised, mistrust between the community and the private firm ensues.

Responding to this, a local government official argued that the processes and laws must be adhered to, regardless of pressure from customers – although informants from private firms suggested that public officials themselves often do not systematically follow the laws. In principle, each step in the processes of land planning and surveying is allocated an appropriate timeframe for accomplishment. One professional from a private firm, for instance, pointed out that under Section 11 of the Urban Planning Act of 2007, the RS is required to give feedback on submitted plans within two months. However, this is hardly ever done. The evidence collected indicates that the process usually takes longer because of complicated procedures. Private firms have no control over timeframes and the smooth implementation of their work is often impeded. This in turn may affect the flow of income as well as their clientele base.

The complexities encountered in the delivery of planning and surveying services is significantly higher than other services within the land sector. This seems to be a consequence of the number and range of government agencies involved, which is greater than, for instance, those involved in services such as land use disputes and land administration. Moreover, whereas in other services the parties involved have recourse to alternative options – for example, landholders can opt for legal representation in Land Tribunals and Courts of Law in case of conflicts with regard to compensation – those who are applying for land titles and submitting land use plans do not have other administrative options to appeal to. It is worth pointing out that the kind of procedural complexities faced by private firms are not different from those that government offices encounter in delivering the same services. The involvement of private firms adds another actor to the process – the private firm, as well as the community and government offices – whereas government offices deal directly with communities. Intuitively, one might expect this to increase the time and costs involved, but because of the backlog of activities in the land sector, this is often not the case: rather, it might take even longer for the government offices to offer the same services because of limited capacity.

5.1.2. Political interference

Despite the existence of regulations to check abuse of power, undue political interference in the delivery of land services is an impediment. There are, for instance, the 2007 guidelines for the preparation of general planning schemes of regularization which emphasizes that political interests should not overshadow the consideration of professionals in the urban land use planning and surveying sector (MLHHSD Citation2007). Similarly, a directive from the MLHHSD bans councils from participating in land surveying activities, although they are still mandated to perform their role of approving schemes as stipulated by the law. However, this directive is not yet reflected in the prevailing legal and policy framework. Thus, despite existing regulations and directives, findings from the study reveal that councillors flout these restrictions. One of the main requirements in the urban planning standards and regulation is that detailed land use planning schemes must show land for public use such as roads, schools, health facilities, markets, recreation areas and so forth. However, using their political position, councillors often interfere during the preparation of these schemes. It was revealed by the private firm professional that councillors influence changes in the plans which may compromise the technical standards and ethics of firms. Respondents added that they are often forced to turn a blind eye to these violations, otherwise councillors will use their influence to block the approval of plans by the council as an official from a private firm attested:

… one time a councillor demanded that we change the location of the bus station on the plan. He had his own interest in the new location and little consideration for planning standards and location. This councillor threatened to block the approval process of the plan, if presented in the council meetings without complying with his wishes … sometimes, councillors make promises during election period and they exercise their authority when in office to fulfil them.

Local leaders also complained about political interference especially with regard to hiring of firms for land services. While there are clear bidding procedures for the services of private firms, the process may not always be transparent and fair to all bidding firms. For instance, some councillors present the names of private firms of their choice to the local leaders, which then get endorsed as having passed the selection processes although they may not be the best competitors in the process. In one of the sub-ward offices, it was revealed that a private firm which lacked planning professionals was hired as a result of political influence. When this came to light, a new tender process was initiated, leading to delays. The local community then lost faith in the sub-ward officials and ultimately, the whole project was delayed. The research also revealed that political party interest can undermine planning efforts in peri-urban areas. One of the local leaders noted that this was a particular concern in areas where local government officers are predominantly from opposition political parties. In some cases, their planning initiatives are thwarted by officials from the ruling party who lobby the local community to shun proposals presented to them by opposition leaders. These observations underline the difficult working environment facing private firms that attempt to deliver land services.

5.1.3. Delays in payments

The amount paid for land planning and surveying services varies according to the number of community members ready to participate and willing to pay. As indicated in , private firms mobilize resources from a group of community landholders: the greater the number of participants, the lower the cost for each one. MLHHSD and municipalities may also influence the cost of services offered by private firms, resulting in discrepancies in charges from one firm to another. Private firms are normally profit oriented and therefore strive to win contracts, under-bidding other firms in the tender process if necessary.

Table 1. Cost of planning and survey services in Tanzania shillings.

Once contracts are assigned, landholders may not pay service fees on time, even when local leaders and private firms create favourable payment terms, such as making provision for payment by instalment. Such delays in payments have a knock-on effect: the private firms may be unable to deliver the services contracted, which impacts on households that have met their obligations. This leads in turn to complaints against the firms and demoralization among the paid-up households. Local leaders in the study noted that some community members were reluctant to pay because they associate regularization of informal land with attempts by the government to increase tax collection. The leaders also revealed that they sometimes seek exemption of fees for vulnerable people who cannot afford to contribute. The fee charged covers the land regularization services for the whole community; if a small number of people do not contribute, this will reduce the profits of the contracted private firms, but the amount involved is not usually enough to cause substantial financial losses to the firm. Nevertheless, payment delays and defaults can affect the private firms’ revenues: when substantial numbers of people fail to pay for the services and others delay payments, registration activities cannot be completed. The whole process is then delayed and costs may vary over time, such that when the project is finally completed, the costs in the original bid quotation may no longer be valid.

5.1.4. Limited awareness

The participation of community members and the timely payment of fees for delivering planning and surveying services are also affected by the level of awareness among community members and local leaders. Karni and Viero (Citation2017) note that the level of awareness is a measure of citizens’ capacity to adopt and participate in a project, whether initiated by themselves, or others. In the present study, private firms pointed out that both community and local leaders are sometimes not aware of issues and tasks pertaining to planning and surveying processes, even when they have initiated regularization projects in their areas. This may result in some community members paying for planning and surveying services, while others do not cooperate, even though they are occupying land within an area undergoing regularization. During discussions with community members and ward leaders, it was confirmed that indeed some landholders were not included in the scheme because they had not paid the necessary costs. One of the occupants who refused to pay noted:

… I was told that land was being surveyed in my community at short notice … however, I am not so sure how this will help me as a community member. I believe that there is no benefit accruing from one's land being surveyed …

Professionals from the private firms also explained that while community members sometimes collaborate with local leaders in choosing a private firm to provide land services in their areas and in agreeing on payment arrangements, they are generally not conversant with the bureaucratic processes which private firms have to go through to deliver those services. As a result, they often have unrealistic expectations, and the process may take much longer than anticipated. Local leaders also complained that, because of their presence at the grassroots level, they are frequently disturbed by community members wanting to know the status of their planning scheme; yet, the leaders may not be in position to give convincing responses because they are not adequately informed themselves. The tendency of private firms to blame community members and local leaders for their limited awareness of procedures demonstrates the poor communications among stakeholders, including municipal officials responsible for land use planning and surveys. The following quote from a Municipal officer further illustrates the limited awareness among local communities:

… sometimes community members come to our office complaining against private firms due to delays in accomplishing an assignment, but when we do our investigation, we discover that the problem is associated with procedures and not the fault of firms.

Discussions with local leaders revealed that a number of bureaucratic initiatives have been taken to ensure that community members are aware of the importance of closely cooperating and participating in the planning and surveying activities assigned to private firms. Public address systems have been used in public awareness campaigns, and announcements are made during social gatherings. Social media platforms such as WhatsApp involving community groups and bulk phone messaging are used. There have also been initiatives by the government to sensitize communities to the issue of land use planning and surveying, for instance through periodic notices and announcements using print, radio and television media. The persistently low levels of public awareness, however, suggest that these efforts are still inadequate.

5.1.5. Inadequacies in compensation

Misunderstandings between private firms and landholders may occur when planners and surveyors are in the field, or when the plans are displayed for public examination. At that stage, a landholder might realize that a part of his/her land has been designated for an access road and there is no compensation for such land. Compensation is not a component of most land (planning and surveying) services, primarily because the process is initiated by community members for their mutual benefit as landholders and the public in general. The process of delivering land services includes negotiations between local leaders, private firms and landholders who are expected, where necessary, to donate part of their land for public use. Urban planning and space standards regulations state that an access road should have a width of 15 m (i.e. 7.5 m each side) (URT Citation2011). However, in developed areas, it is often not possible to provide such wide roads; where there is a permanent structure that precludes such a width, roads may measure as little as 3 m wide (i.e. 1.5 m each side). Even when the road size has been thus reduced, however, pieces of land can be affected. This arises from the fact that these areas were initially developed informally, without planning restrictions and overall design.

The situation is particularly complex when landholders have built permanent houses that have to be demolished under proposed plans. It is difficult for private firms to engage with occupants and to gain their consent or understanding. Private firms have their own strategies for implementing planning schemes despite such challenges. As one of the officials from a private firm remarked:

… plots of land marred with conflicts and areas where landholders are uncooperative are bypassed during the planning processes, but the location of these areas are captured in the planning scheme for future adjustment surveying.

It is clear from the above that the problems facing private firms are mainly technical, and that the existing legal and policy framework is not able to resolve these issues. This reduces the efficiency of the private firms and hampers the delivery of land (planning and surveying) services in peri-urban areas.

5.2 The significance of private firms in land services

The study showed that, amidst the multiple challenges they faced, private firms appreciated the government initiatives to promote their role in delivering land services, and government officials applauded the efforts of private firms. It was acknowledged that the work of private firms was supplementing government efforts in providing land services and thus reducing the backlog of planning and surveying activities in the land sector. The services of private firms have contributed particularly to the transformation of peri-urban areas. This has increased the land value in peri-urban areas and attracted many actors, both land service providers and consumers. During FGDs, participants concurred that the services of private firms would contribute to increasing the value of land in the area. This would enable the landholders in future to parcel out or sell their land at reasonable market prices. It was also mentioned that, should the government require land from occupants for public use, landholders could turn to private firms to survey their land at short notice, allowing them to reap more benefit from the land compensation plan than if the land was not surveyed. The regularization of land would also enable the holders to offer their land as security in order to access financial services. The services of private firms have also played a role in fulfilling the government mandate of providing access roads in areas where land planning and surveying services are embraced by the community members.

There was general agreement in the FDGs that land planning and surveying services by private firms had contributed to the reduction of land disputes associated with trespassing and encroachment, as a result of poor demarcation of plot boundaries. This was also emphasized by one of the local leaders:

… in my area of jurisdiction, I have noticed that ever since people started planning and surveying their plots, over the years, cases of land disputes reported in my office have been minimal.

It was noted that land inheritance disputes in particular had been reduced through the land regularization services offered by private firms, which had facilitated legal documentation of formerly inherited land. This legal documentation reduced the risk to landholders of their land being snatching by members of the family lineage.

The research also revealed that the services of private firms in the land sector had contributed to broadening the tax base in two ways; the private firms themselves pay taxes, while on the other hand landholders of surveyed land are expected to pay land rent tax. Participants acknowledged that the accrual of taxes enabled the government to provide infrastructure services in the area such as water, electricity and road maintenance.

During interviews with local leaders, it was observed that employment opportunities had been created in the land sector for both professionals and non-professionals. Officials from the private firms confirmed that they had been hiring skilled and unskilled people within the community. The study revealed that most private firms employ at least 10 professionals, excluding temporary workers. This has enabled planners and surveyors, most of whom are not employed by the government, to gain work experience and expertise, and even to establish their own companies. Private firms have thus played a role in building skills and contributing to professional advancement in the land service delivery industry.

6. Discussion

There is a growing consensus that private firms play a pivotal role in urban development in African countries and that many cities have experienced positive changes as a result (Van Noorloos and Kloosterboer Citation2018). It was the aim of this paper to explore the challenges of private firms’ participation in delivering land use planning and surveying services in the developed peri-urban areas in Dar es Salaam.

Land delivery (planning and surveying) services implemented by private firms are subject to the existing policy and legal frameworks within a country. In Tanzania, deficiencies within these frameworks are apparent. The law gives more authority to LGAs, RS and MLHHSD (URT Citation1995, Citation1999, Citation2007; Massoi and Norman Citation2010); these bodies all have power to amend and approve planning and surveying schemes, while private firms – as partners in land services delivery – do not have power to make significant changes or decisions (Babere and Ramadhani Citation2018). Government institutions sometimes operate high-handedly: they can, for instance, revise the planning schemes prepared by private firms without consulting them, even though the technical expertise of private firms, as implementers, is crucial. Existing laws guiding land services provision have also contributed to bureaucratic overload within the relevant departments and units. As Hayuma and Conning (Citation2006) observe, land procedures in Tanzania are lengthy, time-consuming and expensive for private firms, private individuals and the local poor. They represent a burden for land service providers and consumers alike.

Besides the legal and policy issues, studies in a number of developing countries have exposed the tendencies of politicians to abuse power. Although public projects in land use planning and surveying are expected to contribute positively towards the lives of local communities, achieving that goal may be frustrated by political interference. Politicians – most of whom do not have knowledge of planning and surveying – have the authority to decide on professional matters that concern land. As noted by Rogger (Citation2018), one of the obstacles to successful development projects in many African countries is political interference in technical aspects. Such political decisions may be influenced by the party, or by vested political or monetary interests. In Pakistan, Khan et al. (Citation2019) argue that the geopolitical environment has led to the slow development of infrastructure projects because the tendering process, and the progress of projects in general, are influenced by political and tribal interferences. Favouritism and corruption have led to projects being managed by unqualified companies. In Tanzania, Magigi and Majani (Citation2006) observe that political interference has adversely impacted upon land regularization in informal settlement projects in Dar es Salaam City, which has led in turn to the country losing support for land projects from international development partners. Political interference is not only manifested in the land sector in developing countries, but also in the provision of other services. For example, Adams, Sambu, and Smiley (Citation2018) reveal that private firms lobby politicians to win tenders for services in the water sector. This type of political interference thrives in an environment where there is limited awareness of peoples’ rights, and a lack of transparency.

Limited awareness among communities was one of the findings of the present study, but it has also been observed elsewhere. Inadequate public awareness can be seen as a major governance weakness in many developing countries because it prevents communities from participating in and managing their own projects which can lead those projects to fail (Iddi and Nuhu Citation2018). Magigi and Drescher (Citation2010) note that communities often lack relevant knowledge of the policy and legal frameworks that guide urban planning and land services. Lack of awareness has direct links with lack of interest and sensitivity to land matters, leading to delays in payment for land services. As noted above, where local community members are not conversant with land use planning and surveying procedures, they are reluctant to pay; consequently, private firms may face problems in implementing projects due to late and insufficient contributions from the community. Political leaders can either promote or obstruct awareness initiatives in communities; this can be intentional or without intent. A lack of cooperation between leaders due to partisan politics may be another stumbling block in the implementation of community projects. Whilst vested interests can be difficult to isolate from development activities, it is crucial to separate the two. Areas which provide strong political support often witness active implementation of government projects (Anyimadu Citation2016).

Despite the challenges encountered by private firms, their role in delivering planning and surveying services in Tanzania should not be underestimated. They strive to meet the increasing need for land planning and surveying services and facilitate secure tenure for many, who would not otherwise have access to such services. Due to the participation of private firms in the delivery of land services, the supply of building land in Dar es Salaam City has been increasing (Kasala and Burra Citation2016; Makundi Citation2017). Private firms have played an important role in filling the gap between the demand and supply of serviced land (Venables Citation2015; Ogunbayo et al. Citation2016; Kasala and Burra Citation2016; Kalabamu and Lyamuya Citation2017). In Tanzania, between 2002 and 2012, private firms were able to deliver approximately 68,000 plots in Dar es Salaam City; between 2013 and 2015, they were responsible for delivering 32,650 plots (Kasala and Burra Citation2016; Nuhu Citation2018). Kalabamu and Lyamuya (Citation2017) found out that the private sector in Botswana played a similar role, with nine (9) private firms delivering 1191 planned and serviced plots between 1998 and 2001.

There is growing evidence that the participation of private firms has increased and they are playing a significant role in the land sector in Sub-Saharan Africa (El-hadj, Faye, and Geh Citation2018). In Tanzania, private firms have been engaged in land regularization processes, provision of serviced land, supply of mortgaged houses and real estate development (Kasala and Burra Citation2016; Makundi Citation2017; Nuhu Citation2018; Stina, Amelia, and Joshua Citation2018). In Kenya, private firms has been instrumental in the cadastral processes, conducting more than 95 percent of the work (Nyadimo Citation2006). Lamond et al. (Citation2015) also note that in the Nigeria cities of Enugu, Lagos and Ibadan, private firms have contributed to urban land planning. These efforts across countries reveal that land use planning and surveying services delivered by private firms have not only enabled communities to access plots, but have also facilitated the acquisition of title deeds by landholders.

Land planning and surveying is a costly venture and, therefore, not easily affordable for many people (Silayo Citation2005). The present study estimates that land use planning and surveying for one plot costs 2–3 million Tanzanian Shillings if undertaken by an individual landholder. With the participation of private firms in regularizing informally accessed land for whole communities, the cost has reduced significantly because the community shares the costs of the services. The adoption of economic liberalization policies in many countries has enabled the registration of many private firms involved in the delivery of land services which were formerly provided exclusively by the public sector. As more private firms engage in land services delivery, competition in service provision increases, leading to the reduction of charges in order to win clients (Rondinelli Citation2003; Lugongo Citation2017). Through competition, costs are reduced not only for community members but also for the government. In Kenya, for instance, the participation of private firms in developing a participatory planning practice in Kitale proved to be cost effective (Majale Citation2009). It is argued that if the government had been engaged in purchasing supplies of building materials, quoted prices on invoices would have been hyped.

Private firms have also contributed to enabling peri-urban landholders to regularize their informal land rights. In turn, this can enable the government to collect more tax revenues and to provide better social services to previously neglected areas. Private sector real estate experts, planners and surveyors also have the capacity to deliver sustainable solutions for city growth (Kasala and Burra Citation2016).

7. Conclusion

This paper has offered an insight into the experiences of private firms delivering land use planning and surveying services in peri-urban areas of Dar es Salaam City. Private firms have emerged as important actors in land markets and urban development, enabling land regularization and thus enhancing security of tenure. This has promoted land use efficiency and contributed to reduction of land use disputes. The study has demonstrated that private firms are participating in a complex governance structure in the implementation of their activities. They are faced with external and internal challenges which have hindered efficient distribution and supply of serviced land. As a result, informal land access processes characterized by insecurity of tenure have largely prevailed. The expertise and competence of private firms has not been adequately exploited to improve land use efficiency due to these challenges. Certain measures would reduce these obstacles: procedural complexities should be simplified to enable efficient delivery of land services by revising planning and surveying related policies; land services should be decentralized to reduce bureaucratic procedures in the Ministry of Land; political interference in the land sector should be controlled through periodic performance-monitoring activities and through incorporating regularization projects into national plans. Finally, adequate community engagement and awareness creation by both the government and private firms is needed to enable local communities to appreciate the importance of land use planning and surveying, and thus participate effectively.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Abwe, F.G. 2009. Access to Land for Housing by the Urban Poor in Tanzania: A Case of 20,000 Plots Project in Dar es Salaam City. Paper Presented at the International Scientific Conference of Commonwealth Association of Surveying and Land Economy, June 29th–30th, 2009 at White Sands Hotel, Dar es Salaam City, Tanzania

- Adam, A. G. 2014. “Informal Settlements in the Peri-Urban Areas of Bahir Dar, Ethiopia: An Institutional Analysis.” Habitat International 43: 90–97. doi: 10.1016/j.habitatint.2014.01.014

- Adam, A. G. 2020. “Understanding Competing and Conflicting Interests for Peri-Urban Land in Ethiopia’s Era of Urbanization.” Environment and Urbanization, 1–14.

- Adams, E. A., D. Sambu, and S. L. Smiley. 2018. “Urban Water Supply in Sub-Saharan Africa: Historical and Emerging Policies and Institutional Arrangements.” International Journal of Water Resources Development, 1–24.

- Africa Union Commission. 2015. Agenda 2063: The African We Want. Final Edition, Popular Vision. Available at https://www.un.org/en/africa/osaa/pdf/au/agenda2063.pdf

- Agwanda, A., and H. Amani. 2014. Population Growth, Structure and Momentum in Tanzania. Background Paper No. 7, ESRF Discussion Paper 61. Dar es Salaam: Economic and Social Research Foundation.

- Altenburg, T., and C. von Drachenfels. 2008. Creating an Enabling Environment for Private Sector Development in Sub-Saharan Africa. Vienna: UNIDO and GTZ.

- Anyimadu, A. 2016. Politics and Development in Tanzania: Shifting the Status Quo. Chatham House.

- Babere, N., and I. Ramadhani 2018. Public and Private Planning Practice for Land Readjustment in Peri-urban Areas in Ilala, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Paper Prepared for Presentation at the 2018 World Bank Conference on Land and Poverty, March 19–23. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

- Birner, R. 2007. Improving Governance to Eradicate Hunger and Poverty. 2020 FOCUS BRIEF on the World’s Poor and Hungry People. Institute of Regional and Local Development Studies, 2013, Governance and Public Service Delivery: The case of water supply and roads services delivery in Addis Ababa and Hawassa Cities, Ethiopia

- Briggs, J., and D. Mwamfupe. 2000. “Peri-Urban Development in an Era of Structural Adjustment in Africa: the City of Dar es Salaam, Tanzania.” Urban Studies 37 (4): 797–809. doi: 10.1080/00420980050004026

- El-hadj, M. B., I. Faye, and Z. F. Geh. 2018. Housing Market Dynamics in Africa. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Farrell, K. 2017. “The Rapid Urban Growth Triad: a New Conceptual Framework for Examining the Urban Transition in Developing Countries.” Sustainability 9 (8): 1407. doi: 10.3390/su9081407

- Gough, K. V., and P. W. Yankson. 2000. “Land Markets in African Cities: the Case of Peri-Urban Accra, Ghana.” Urban Studies 37 (13): 2485–2500. doi: 10.1080/00420980020080651

- Hayuma, M., and J. Conning. 2006. “Tanzania Land Policy and Genesis of Land Reform Subcomponent of Private Sector Competitiveness Project.” Land Policies and Legal Empowerment of the Poor, 2–3.

- Holden, S. T., and K. Otsuka. 2014. “The Roles of Land Tenure Reforms and Land Markets in the Context of Population Growth and Land Use Intensification in Africa.” Food Policy 48: 88–97. doi: 10.1016/j.foodpol.2014.03.005

- Hossain, S., W. Scholz, and S. Baumgart. 2015. “Translation of Urban Planning Models: Planning Principles, Procedural Elements and Institutional Settings.” Habitat International 48: 140–148. doi: 10.1016/j.habitatint.2015.03.006

- Iddi, B., and S. Nuhu. 2018. “Challenges and Opportunities for Community Participation in Monitoring and Evaluation of Government Projects in Tanzania: Case of TASAF II, Bagamoyo District.” Journal of Public Policy and Administration 2: 1–10. doi: 10.11648/j.jppa.20180201.11

- Jones, H., C. Cummings, and H. Nixon. 2014. Services in the City: Governance and Political Economy in Urban Service Delivery. London: Overseas Development Institute.

- Kalabamu, F. T., and P. K. Lyamuya. 2017. “An Assessment of Public–Private-Partnerships in Land Servicing and Housing Delivery: The Case Study of Gaborone, Botswana.” Current Urban Studies 5 (04): 502. doi: 10.4236/cus.2017.54029

- Karni, E., and M. L. Viero. 2017. “Awareness of Unawareness: a Theory of Decision Making in the Face of Ignorance.” Journal of Economic Theory 168: 301–328. doi: 10.1016/j.jet.2016.12.011

- Kasala, S. E., and M. M. Burra. 2016. “The Role of Public–Private Partnerships in Planned and Serviced Land Delivery in Tanzania.” iBusiness 8: 10–17. doi: 10.4236/ib.2016.81002

- Khan, A., M. Waris, I. Ismail, M. R. Sajid, M. Ullah, and F. Usman. 2019. “Deficiencies in Project Governance: an Analysis of Infrastructure Development Program.” Administrative Sciences 9 (1): 9. doi: 10.3390/admsci9010009

- Kironde, J. L. 1997. “Land Policy Options for Urban Tanzania.” Land use Policy 14 (2): 99–117. doi: 10.1016/S0264-8377(96)00040-3

- Kironde, J. L. 2000. “Understanding Land Markets in African Urban Areas: the Case of Dar es Salaam, Tanzania.” Habitat International 24 (2): 151–165. doi: 10.1016/S0197-3975(99)00035-1

- Kironde, J. L. 2009. “Improving Land Sector Governance in Africa: The Case of Tanzania.” In Workshop on “Land Governance in Support of the MDGs: Responding to New Challenges. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- Kironde, J. M. L. 2015. “Good Governance, Efficiency and the Provision of Planned Land for Orderly Development in African Cities: The Case of the 20,000 Planned Land Plots Project in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania.” Current Urban Studies 3 (04): 348. doi: 10.4236/cus.2015.34028

- Kombe, W. J. 2001. “Institutionalising the Concept of Environmental Planning and Management (EPM): Successes and Challenges in Dar es Salaam.” Development in Practice 11 (2-3): 190–207. doi: 10.1080/09614520120056342

- Kombe, W. J. 2005. “Land use Dynamics in Peri-Urban Areas and Their Implications on the Urban Growth and Form: the Case of Dar es Salaam, Tanzania.” Habitat International 29 (1): 113–135. doi: 10.1016/S0197-3975(03)00076-6

- Kombe, W. J. 2010. ‘Land Conflicts in Dar es Salaam: Who Gains? Who Loses?’, Crisis States Working Paper 82 (Series 2). London: Crisis States Research Centre.

- Kombe, W. J., and V. Kreibich. 2006. Governance of Informal Urbanisation in Tanzania. Dar es Salaam: Mkuki na Nyota Publishers.

- Kulaba, S. 2019. “Local Government and the Management of Urban Services in Tanzania.” In African Cities in Crisis, edited by R. E. Stream, and R. R. White, 203–245. New York: Routledge.

- Lamond, J., B. K. Awuah, E. Lewis, R. Bloch, and B. J. Falade. 2015. Urban Land, Planning and Governance Systems in Nigeria. Urbanisation Research Nigeria (URN) Research Report. London: ICF International. Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial-Share Alike CC BY-NC-SA.

- Lugongo, B. 2017. “Dar Strives to Reduce Survey fee.” Daily News. Dar es Salaam: The National Newspaper

- Lwasa, S. 2010. Urban Land Markets, Housing Development, and Spatial Planning in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Case of Uganda. UK: Nova Science Publishers.

- Magigi, W. 2013. “Public–Private Partnership in Land Management: A Learning Strategy for Improving Land use Change and Transformation in Urban Settlements in Tanzania.” Research on Humanities and Social Sciences 3 (15): 148–157.

- Magigi, W., and A. W. Drescher. 2010. “The Dynamics of Land use Change and Tenure Systems in Sub-Saharan Africa Cities; Learning from Himo Community Protest, Conflict and Interest in Urban Planning Practice in Tanzania.” Habitat International 34 (2): 154–164. doi: 10.1016/j.habitatint.2009.08.004

- Magigi, W., and B.B.K. Majani. 2006. Housing Themselves in Informal Settlements: A Challenge to Community Growth Processes, Land Vulnerability and Poverty Reduction in Tanzania. Proceedings of the 5th FIG Regional Conference, Accra, 8–11 March 2006, 1/24–24/24.

- Majale, M. 2009. Developing Participatory Planning Practices in Kitale, Kenya: Case Study Prepared for the Global Report on Human Settlements. Available at https://unhabitat.org/wp-content/uploads/2010/07/GRHS2009CaseStudyChapter04Kitale.pdf

- Makundi, D. I. 2017. Assessment of Policies and Practices of Land Delivery by Private Sector: A Focus on Two Projects in Kigamboni Municipality in Dar es Salaam City (Master’s Thesis). Ardhi University, Dar es Salaam.

- Mallik, C. 2018. “Public–Private Discord in the Land Acquisition Law: Insights from Rajarhat in India.” Singapore Journal of Tropical Geography, 1–20.

- Massoi, L., and A. S. Norman. 2010. “Dynamics of Land for Urban Housing in Tanzania.” Journal of Public Administration and Policy Research 2 (5): 74–87.

- Mkalawa, C. C., and P. Haixiao. 2014. “Dar es Salaam City Temporal Growth and Its Influence on Transportation.” Urban, Planning and Transport Research 2 (1): 423–446. doi: 10.1080/21650020.2014.978951

- MLHHSD. 2007. Guidelines for the Preparation of General Planning Schemes and Detailed Schemes for New Areas, Urban Renewal and Regularization. Dar es Salaam: Ministry of Lands, Housing and Human Settlements Development.

- Msale-Kweka, C. 2017. Land Use Changes in Planned, Flood Prone Areas: The Case of Dar es Salaam City (PhD Thesis). Ardhi University

- Mweti, A.M. 2013. Land Service Delivery and Economic Development: Opportunities and Challenges in the Municipality of Otjiwarongo (Masters Dissertation). The University of Namibia

- Nuhu, S. 2018. “Peri-urban Land Governance in the Developing Countries. Understand the Role, Interaction and Power Relation among Actors in Tanzania.” Urban Forum 29 (89): 1–16.

- Nuhu, S. 2019. “Land-Access Systems in Peri-Urban Areas in Tanzania: Perspectives from Actors.” International Journal of Urban Sustainable Development, 1–14.

- Nyadimo, E. 2006. The Role of Private Sector in Land Adjudication in Kenya: a Suggested Approach. Munich: FIG Congress-Community Involvement and Land Administration.

- Ogunbayo, B. F., O. A. Alagbe, A. M. Ajao, and E. K. Ogundipe. 2016. “Determining the Individual Significant Contribution of Public and Private Sector in Housing Delivery in Nigeria.” British Journal of Earth Sciences Research 4 (3): 16–26.

- Otiso, K. M. 2003. “State, Voluntary and Private Sector Partnerships for Slum Upgrading and Basic Service Delivery in Nairobi City, Kenya.” Cities 20 (4): 221–229. doi: 10.1016/S0264-2751(03)00035-0

- Rogger, D. 2018. The Consequences of Political Interference in Bureaucratic Decision Making: Evidence From Nigeria. Development Economics Development Research Group. Policy Research Working Paper 8554. The World Bank.

- Rondinelli, D. A. 2003. “Partnering for Development: Government-Private Sector Cooperation in Service Provision.” In Reinventing Government for the Twenty-First Century: State Capacity in a Globalizing Society, 219–239.

- Silayo, E. H. 2005. “Searching for an Affordable and Acceptable Cadastral Survey Method.” In FIG Working Week, 16–21. Cairo.

- Smit, W. 2018. “Urban Governance in Africa: An Overview.” In African Cities and the Development Conundrum, 55–77. Brill Nijhoff.

- Stina, M.W., K. Amelia, and C. Joshua. 2018. Urban land governance in Dar es Salaam, Actors, Processes and Ownership Documentation, C-40412-TZA-1

- Transparency International. 2017. Service Delivery in the Land Sector in the City of Kigali and Secondary Cities of Rwanda: Assessing Users’ Perception and Incidence of Corruption. Kigali: Rwanda: Transparency International.

- UG. 2013. The National Land Policy. Uganda: Kampala: Ministry of Lands, Housing and Urban Development.

- UN. 1996. Global Conference on Access to Land and Security of Tenure as a Condition for Sustainable Shelter and Urban Development, Istanbul, Turkey

- UN. 2008. Guidebook on Promoting Good Governance in Public–Private Partnerships. New York and Geneva: United Nations.

- UN. 2015. Transforming Our World: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development Goals. New York: United Nations.

- UN. 2017. Resolution Adopted by the General Assembly on 23 December 2016. New York: United Nations. Available at https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/generalassembly/docs/globalcompact/A_RES_71_256.pdf.

- UN-Habitat. 2016. Urbanization and Development Emerging Futures. World Cities Report. UK: Earthscan Publications.

- United Republic of Tanzania (URT). 1977. The Land Survey Act CAP.324. Tanzania: Dar es Salaam: The Government Printer.

- URT. 1995. National Land Policy. Ministry of Lands and Human Settlements Development. Dar es Salaam: Government Press.

- URT. 1999. Land Act of 1999. Ministry of Lands and Human Settlements Development. Dar es Salaam: The Government Printer.

- URT. 2000. National Human Settlement Policy. Ministry of Lands and Human Settlements Development. Dar es Salaam: Government Press.

- URT. 2007. Urban Planning Act of 2007. Ministry of Lands and Human Settlements Development. Dar es Salaam: The Government Printer.

- URT. 2011. Urban Planning and Space Standards Regulations. Ministry of Lands and Human Settlements Development. Dar es Salaam: The Government Printer.

- URT. 2012. 2012 Population and Housing Census: Population Distribution by Administrative Areas. Dar es Salaam: National Bureau of Statistics, Ministry of Finance.

- Van Noorloos, F., and M. Kloosterboer. 2018. “Africa’s New Cities: The Contested Future of Urbanisation.” Urban Studies 55 (6): 1223–1241. doi: 10.1177/0042098017700574

- Venables, T. 2015. Making Cities Work for Development (IGC Growth Brief 2). London: International Growth Center.

- Wehrmann, B. 2008. “The Dynamics of Peri-Urban Land Markets in Sub-Saharan Africa: Adherence to the Virtue of Common Property vs. Quest for Individual Gain.” Erdkunde 62 (1): 75–88. doi: 10.3112/erdkunde.2008.01.06

- Wenban-Smith, H. 2015. Population Growth, Internal Migration and Urbanisation in Tanzania, 1967–2012. International Growth Center.

- World Bank. 2015. Private Sector Participation in Regenerating Urban Land. Available at https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/video/2015/04/21/private-sector-participation-in-regenerating-urban-land

- World Population Review. 2020. Dar es Salaam Population 2020. Available at https://worldpopulationreview.com/world-cities/dar-es-salaam-population/