ABSTRACT

This analysis focuses on different levels of Cross-Border Regional Planning (CBRP) processes in the Cascadia borderland. The region is home to the business-led initiative ‘Cascadia Innovation Corridor’ (CIC), designed to foster cross-border economic integration. The CIC strives to build a global innovation ecosystem in Cascadia, including a new high-speed train to connect Seattle and Vancouver. This paper focuses on the scope of the CIC as a CBRP case. The authors evaluate engagement of city governments and coherency between different planning scales to determine whether the CIC has been addressing the major challenges that may prevent tighter economicintegration in Cascadia. The analysis deploys secondary data as well as primary data collected through surveys and interviews. The results shed light on a discrepancy between supra-regional ‘soft planning’ and the urban planning level. The authors offer an evidence-based proposal to broaden the scope of the CIC from a CBRP standpoint.

1. Introduction

This paper defines the concept of Cross Border Regional Planning (CBRP) to convey a wide sample of actions, policies and strategies including land-use management, public infrastructure planning or projects in cross-border regions. The heterogeneous variety of border regions hampers clear and rigid classification. Here we aim to give a close look to practices at a small geographical scope that are often neglected in broader cross-border cooperation narratives.

To date, scholars have been conceptualizing planning in border regions in terms of stakeholder engagement and governance alliances, which are arguably effective to steer a development strategy for those territories. The authors here present a unique CBRP framework in order to better cast the discussion in a regional dimension, shifting from a transnational and integrative approach toward a more local cooperative approach (Bradbury Citation2016; Falkheimer Citation2016). By adopting a regional dimension, CBRP can better grasp the informality and the flexibility of cross-border governance structures (Noferini et al. Citation2019).

The CBRP concept reflects the strong interplay between spatial planning and economic growth devoting a new importance to border regions conceived as new hubs for knowledge economies. Accordingly, we present a distinctive case study where a multi-national company has been driving cross-border cooperation (CBC) in the ‘Cascadia’ region at the U.S. – Canadian border. In particular, the authors examine a public-private initiative known as the ‘Cascadia Innovation Corridor’ (CIC). The CIC initiative aims to both ‘rebrand’ the region as a tech hub on the global stage, and also to address major public and private investments towards planning a new transportation infrastructure to support a more economically integrated cross-border region. This article evaluates the CIC as a CBRP initiative by investigating cross-border governance through a multi-scalar approach involving local authorities and public and private actors actively engaged in economic cooperation within the CIC framework. The authors debate

the role of city governments in the CIC;

the coherency between the multiple scales of planning, and;

how the CIC can be enhanced to pursue a common territorial strategy to meet societal needs in Cascadia.

This study relies on extensive field research conducted in the region. The authors conducted structured interviews with forty representatives from organizations active in the CIC ecosystem. The authors processed primary data to gauge the embeddedness of the two city governments within the CIC, and to evaluate the interplay between the multiple scales of planning, addressing the discrepancy between soft planning/spaces and hard planning/spaces (Zimmerbauer Citation2018). Finally, open-ended questions let the surveyed actors identify potential triggers for tighter CBC.

This article is structured as follows: the second and third sections discuss literature review concerning the CBRP, and the current practices in Cascadia, while the fourth and fifth sections outline the research strategy and methodology. The final section presents results and discuss policy implications to guide CBRP decisions in the future.

2. Literature review

When it comes to driving development in cross-border areas, the complexity of regulatory, monetary, cultural, and historical differences between the two sides of the border surface sharply. In this regard, there is a widespread debate among policy-makers, academics and practitioners concerning the drivers and hindrances that affect the notion of Cross Border Cooperation (CBC). Noferini et al. (Citation2019, 4) define cross-border collaboration as ‘a network governance system that goes beyond national jurisdictions in order to develop cross-border joint initiatives.’ The complexity increases when decisions are required in the field of cross-border spatial planning, namely integrating various land-use interests and solving land-use conflicts (Deppisch Citation2012). Indeed, spatial planning involves ‘stakeholders embedded in divergent political, legal, and, more broadly, cultural contexts’ (Jacobs Citation2016, 69). As several scholars recognize, cross border spatial planning is generally a difficult task (Knippschild Citation2011), heightened by the ‘instability and adaptability of cross-border regions from a spatial perspective’ (Pupier Citation2019) because their perimeters can be fuzzy and changing over time. In this regard, cross-border spatial planning is intended to address ‘the need to develop a common project with a variety of actors on both sides of the border, in order to discuss a joint development strategy’ (Durand Citation2014, 4).

In the literature, there seems to be a lack of theoretical references about what cross-border spatial integration means in terms of spatial planning (Decoville and Durand Citation2017). For instance, what is conceived as cross-border spatial planning ranges ‘from strategic urban and regional planning to site and cross-border infrastructure development’ (Jacobs Citation2016, 70). On the other hand, there are a limited number of cases where clear planning strategies have been implemented in border regions (Noferini et al. Citation2019), which hampers a clear definition. Decoville and Durand (Citation2017) argue that it is not possible to consider cross-border spatial planning in a supra-national perspective since it is of pertinence to regional and local actors. This is arguably true in Europe, but less so in North American contexts, as our analysis highlights.

Through its Cohesion Policy, the European Union advocates an even development across its member states, including border regions. Spatial planning is not a supra-national competence (Decoville and Durand Citation2017, 67). However, the European Union leverages more cross-border spatial planning through nonbinding strategies, such as the European Spatial Development Perspective (ESDP) (1999), the Green Paper on Territorial Cohesion (2008), and the Territorial Agenda 2020. The European Group Territorial Cohesion (EGTC) can be considered as arenas of cooperation keen to tackle transnational issues, such as cross-border transportation (Caesar Citation2017) or align innovation policy embedded in a joint cross-border strategy (Oliveira Citation2015).

In fact, cross-border interdependent metropolitan areas reveal that balanced and integrated spatial development becomes one of the common policy objectives both in the EU (Fricke Citation2015) and U.S.(Herzog Citation2000). In this respect, the experience from the Detroit River International Bridge project at the U.S. – Canadian border between Detroit and Windsor discloses a complex, lengthy and controversial bi-national planning process (Bradbury Citation2016).

Therefore, this section reviews definitions and approaches concerning cross-border spatial planning more pertinent to the case study. Peña follows an institutional approach to study cross-border planning as ‘an institution-building process whose primary emphasis is on the facilitation of collective action with regards to the shared natural, built, and human environments constrained by territorial politics and boundaries of nation-states’ (Peña Citation2007, 1). On the other hand, Fricke underlines a more cooperative pattern, defining the cross-border spatial planning as ‘an exchange of information, coordination or cooperation with regard to the spatial development in the cross-border area’ (Fricke Citation2015, 855).

We refer also to the territorialist approach that points out reterritorialization as ‘the reorganization of social, economic and political activities at the sub-national scale’ (Noferini et al. Citation2019, 16). Within a territorialist approach, Zimmerbauer (Citation2018) raises the role of ‘agency’ in discussing how the actors nurture the idea of regional identity in planning practices. He points out the concept of soft space and soft planning which fits well with the CIC formation and its (early-stage) development patterns, as described in later sections.

In this study, the authors incorporate those multiple definitions in an effort to outline a concept of Cross Border Regional Planning (CBRP) as an evaluative concept to be applied to the CIC analysis. This focuses on regional scale in borderland partnerships which goes beyond cooperation between twin cities but encompasses actors in a larger geographical scope (+200 km distant). This drafts from the cross-border regionalism (e.g. Scott Citation1999), but captures the multiplicity of actors (and their networks) keen to bolster innovation-led economic development. This is more in line with a timely approach of innovation management: cross-border regional Innovation ecosystem (see Cappellano and Makkonen Citation2019). The CBRP add emphasis on regional planning that brings together different scales and systems of governance. Moving in the ‘grey area’ between public-private sectors (Lundquist and Trippl Citation2013), the CBRP attunes analysts and practitioners to the informality and the flexibility of cross-border governance structures (Noferini et al. Citation2019). It captures a new geo-spatial focus – a third level of governance (Marcu Citation2011) – which shifts from a transnational approach applied in EU Macro-regions where national states take the leading role, but awards decision-making power to regional actors. In fact, the participation of public and private actors allows for innovative approaches to foster a vision for development in the region. This vision encompasses not only public infrastructure expansion and economic integration, but also an agenda for research & innovation policies. The CBRP adds salience to a ‘constructivism perspective’ (Zimmerbauer Citation2018): the cross-border region builds over time supported by a local (bi-national city-based) cooperative approach (Bradbury Citation2016; Falkheimer Citation2016) where actors mobilize economic and social drivers toward the cross-border integration.

3. Cascadia study case

The original term Cascadia is historically credited to David Douglas, a nineteenth-century Scottish botanist, after whom the Douglas fir tree is named (Todd Citation2008, 4). The initial concept of the regional notion of Cascadia was also a natural, ecological one, developed by Professor David McCloskey in the late 1980s. Since this time, the Cascadia concept has grown into a more political and economic term, and is currently used by a number of academics and business organizations committed to a more pro-business environment within the Cascadia corridor. Specifically, Alan Artibise initiated ideas around not only the cultural connectivity, but also possible economic connectivity within the region of Cascadia in the early to mid-1990s.

In comparison to the other major regions of the Canada – U.S. border, the British Columbia-Washington State region is considered to have the most robust and advanced stage of cross-border collaboration and integration (Friedman, Conteh, and Phillips Citation2019; Border Policy Research Institute [BPRI] Citation2018). Over the past few decades, a substantial organizational infrastructure has evolved in the region that embraces common goals and objectives in the development of this cross-border region. Organizations such as the International Mobility and Trade Corridor Program, the Discovery Institute, the Border Policy Research Institute, and the Pacific Northwest Economic Region span government, private sector, and academia (for an in-depth analysis, see Konrad [Citation2015]). These entities, which engage in different yet overlapping aspects of cross-border collaboration, have helped to establish the momentum and reputation of Cascadia as an integrated region, contributing to the foundation upon which the CIC is currently constructed. Indeed, stakeholders from all of these organizations are active participants in the CIC effort.

Moreover, there is a longstanding relationship between the Governor of Washington and the Premier of BC, and cooperative agreements between them date back to the early 1990s (Wilson Citation2020). During the lead up to the Vancouver Olympics in 2010, the Premier and Governor worked closely on a number of cross-border initiatives, including the creation of the Enhanced Driver's License (Public Safety Canada Citation2008). This legacy of cross-border collaboration at the leadership level played an important role in the establishment of the CIC, which was announced in 2016 along with an MOU between Washington Governor Inslee and B.C. Premier Clark (Office of the Governor Citation2016).

The concept of Cascadia is not without its critics. Matt Sparke (Citation2000), has offered a sustained neo-Marxist critique of the more business-oriented approach to the idea of Cascadia. Clarke (Citation2000) provides a more balanced critique of the notion and evolution of Cascadia, comparing the initial and varied bottom-up activities within the Cascadia region to the more formal top-down activities in Europe’s border regions. Richardson (Citation2016, Citation2017) also revealed that despite Vancouver and Seattle’s close physical proximity and similar economic histories, the two cities were much more economically integrated with regions in the United States and beyond than with each other (see also Cappellano and Rizzo Citation2019). In the same vain, Cappellano and Makkonen (Citation2020) outline low levels of cross-border economic interaction despite high cognitive proximity.

The above helps to reveal that there are many different ideas, institutions, activities, actors, critics, and economic integration challenges that surround the idea and growth of Cascadia. We turn next to the inception of the Cascadia Innovation Corridor initiative as an ongoing development of many actors and interests advancing the notion of Cascadia and its development and evolution into the twenty-first century.

3.1. Cascadia innovation corridor

The Cascadia Innovation Corridor initiative originated in 2016, spurred largely by Microsoft. Part of Microsoft’s impetus in developing the CIC was a consequence of the opening of their Global Excellence Center in Vancouver in 2016 – a direct result of the restrictions – imposed by the U.S. immigration policies – on the high-skilled workers access in the U.S. The effort initially began as an annual conference, rotating each year between Seattle and Vancouver. The city of Portland, Oregon, has been involved to one degree or another (i.e. the high speed rail study), and was recently added to the CIC logo. However, Portland’s engagement remains limited.

To date, the CIC has been supported by two powerful business organizations: the Business Council of British Columbia and Challenge Seattle, which recruited both private partners (e.g. Microsoft) and public authorities at the state and provincial levels. In 2016, Washington State and British Columbia signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) on advancing the cross-border innovation economy. While the document does not represent any legal binding obligation, it does set a vision to develop the Cascadia Innovation Corridor to ‘connect and enhance both regions and create exciting new opportunities for young people and underserved populations’ (British Columbia - Washington MOU Citation2016). The Governor and Premier updated this MOU, and symbolically signed it at the 2018 CIC Conference.

The CIC promotes the vision to maximize the region’s competitive advantages and position the region as a global hub for innovation. This vision is rooted in a number of ‘pillars’, including transportation infrastructure, which ultimately would reduce the travel times between the main cities along the corridor and deliver new opportunities for regional economic growth. Local public authorities are committed to the CIC, as both the British Columbia provincial government and the Washington State government funded a feasibility study on the high-speed train project.

In July 2019, the Washington State Department of Transportation released the business case analysis concerning the Ultra-High-Speed Ground Transportation (UHSGT). This infrastructure would address the demand on transportation within the Cascadia region, estimated in between 3.5 and 4 million passengers commuting daily (along the routes of Seattle, WA – Portland, OR and Seattle – Olympia) and nearly 3 million via the cross-border route (Vancouver, B.C. – Seattle).

The study emphasizes a multi-faceted array of advantages the UHSGT is likely to deliver, which have been accounted for within the return of this investment. However, the estimated cost of this infrastructure – varying between $24 and $42 billion – slows its approval process.

Since October 2018, the CIC steering committee has self-regulated, revamping its structure, as described in the next section.

The financial support from private stakeholders provided the impetus to set up a new seaplane link to connect Seattle and Vancouver where multinational tech companies have their own headquarters. The service started in spring 2018 but due to its carrying capacity and ticket price, it cannot be considered a substantial solution for the transportation gap in services and infrastructure inherent in the region. Furthermore, charismatic leaders and world-class multi-national companies have been committed in this initiative driving attention of the public audience. Insofar, beyond the commitment of public resources to the High-Speed train project, there are a few accomplished milestones which keep the momentum towards closer integration, reported in .

Table 1. Key milestones achieved within the CIC.

3.2. The Cascadia steering committee

Since October 2018, the CIC steering committee has self-regulated, establishing seven main thematic sub-committees where two experts from each side of the border are appointed as leaders, coordinating each working group. The subcommittees cover a number of different topics which include:

Life Sciences;

Transformative Technologies;

Sustainable Agriculture;

Transportation, Housing and Connectivity;

Best and Diverse Talent;

Higher Education Research Excellence;

Efficient People/Goods Movement across the Border.

As the vision for the CIC has been refined in recent years, leadership for the effort began to take shape with the designation of the Business Council of B.C. and Challenge Seattle as co-leaders of the effort. In late 2018, the Steering Committee of the CIC was formed, which provides both a structure and an agenda for the goals of the CIC (B.C. Technology Citation2019).

The structure of the Steering Committee is intended to reflect both the depth and breadth of the goals of the CIC, as well as its bi-national partnership. To achieve these ends, there are two co-chairs of each key sector; one from Washington State and one from B.C. There are also several ‘members at large’ which includes government representatives and additional stakeholders.

Each key sector, or sub-committee is additionally composed of roughly ten members – experts in that sector – representatives from government, private industry, and academia. This diverse structure and combination of expertise ensures a holistic approach to tackling issues such as border delays, transportation, and life sciences. The Steering Committee has met on several occasions since its inception, to establish action items and agendas for the overall CIC effort. These meetings alone allow for both vertical and horizontal linkages between stakeholders across industry, government, and academia, as well as across the Canada – U.S. border. However, the Steering Committee primarily serves as a meso-structure within the broader linkages that will be discussed later.

4. Research strategy

The present research stems from the conception of spatial planning in cross-border regions [..] ‘as ongoing attempts by all sorts of organizations to inverse the barrier effect of the national border and stimulate development on and across it’ (Jacobs Citation2016, 2). The authors examine whether the CIC can be considered as a CBRP initiative, investigating cross-border governance through a multi-scalar approach involving local authorities, public and private actors actively engaged in the economic cooperation within the ethos of the CIC. In particular, the authors examine whether the CIC is positioned to ‘design a shared territorial vision by elaborating a common territorial strategy to meet societal needs’ (Durand and Decoville Citation2018, 6) in the Cascadia cross-border cooperation context. In this view, the analysis addresses the cross-border region limited to Washington State (U.S.) and the province of British Columbia (Canada).

Overall, the study adopts a mixed research approach blending qualitative and quantitative data collected primarily through interviews and surveys, but also taking into account policy documents concerning the major planning strategies in the regions within the CIC. The research has been organized in three main stages, as displayed in . Each stage deals with the topic of the research questions examined.

Table 2. Research strategy.

The first stage examines the level of engagement of city governments (or planning agencies) in the CIC. The analysis sheds light on how the different levels of planning work together. Van Den Broek and Smulders pointed out that a system perspective to address studies on cross-border integration can be short-sighted. They implemented a micro-level approach – according to the ‘Multi-Level Institutional Approach’ (Van den Broek and Smulders Citation2014, Citation2015) – to evaluate whether the institutional actors are embedded through the ‘horizontal’ or ‘vertical dynamics’. In line with this approach, the authors inquire about the role of both Seattle and Vancouver city governments within the CIC.

First, the authors consider the degree of ‘horizontal’ collaborations between the two cities by examining the networks of organizations involved in the CIC. For instance, the city-twinning practices (Ganster and Collins Citation2017), or formal city-to-city relationships. Therefore, a Social Network Analysis was set up to disclose what the level of embeddedness of the two cities is and how the cross-border innovation ecosystem (Cappellano and Makkonen Citation2019) of these organizations may unfold across the border over time. Those results were verified through an analysis of the CIC documents (reports, working documents, official meetings). In so doing, the authors assessed the ‘vertical’ collaborations between the main public actors engaged in the CIC, namely the State of Washington the province of British Columbia and the cities of Vancouver and Seattle. The authors attended the CIC conferences held in 2018 and 2019.

During the second stage, the authors consider the interplay between different planning scales. Zimmerbauer (Citation2018) addressed the combination between ‘soft planning spaces’ and ‘hard planning spaces’ to create the regional identity in Cascadia. The definitions are recalled below ().

Table 3. Definitions from Zimmerbauer (Citation2018).

Therefore, the authors deploy these two concepts to evaluate their interplay and coherency in the juxtaposition between CIC and local planning documents in the two cities. This is particularly relevant in the case of the High-Speed train and its projected stations with the urban plans in Seattle and Vancouver, BC. Moreover, the authors deploy results from interviews – held in the summer 2018 – with planning officials from the two cities and key representatives of organizations involved in the CIC.

Taking into account the planning policy documents from the two planning authorities, the authors highlight their ‘inwardness’: how much these strategies look to the delimited territory rather than to the space on the other side of the border. Moreover, insights from interviews held with officials appointed in planning and economic development departments were used for the data triangulation, adding reliability to the unfolded city-city linkages gauged through the Social Network Analysis.

The third stage of the research identifies the possible catalyzers of further integration between the two sides of the border. To this end, the last part of the survey included two final open ended questions regarding the interviewees’ expectations from the CIC and, in general, from cross-border local integration policies. The respondents could include broad topics as well as definitive single projects. The data were then coded for analysis.

5. Methodology

The authors gathered primary data through an online survey and semi-structured interviews during their field analysis which lasted six months in 2018. The study deploys also secondary data including reports and official documents. Discussions with academics and key representatives of organizations well rooted in the region informed the survey building and the survey sample.

The survey framework was arranged, in line with other studies (see Cappellano and Makkonen Citation2019), into three sets of interview items related to: (I) general information on their organization, their economic links and relationships with the actors on the other side of the border; (II) opinion on critical triggers for tighter cross-border integration and; (III) the role of local public authorities within the cross-border cooperation process. The survey framework featured a mixture of multiple-choice and open-ended questions.

Interviews with planning departments followed open-ended questions regarding the process of CIC in order to disclose: its consistency with their planning strategy; the department involvement in any CIC structured meetings; the collaboration with their counterparts on the other sides of the border; the potential obstacles which may hamper their collaborations.

The 40 organizations interviewed highlighted a total of 102 organizations that are involved in the CIC. In order to simplify the Social Network Analysis, the authors removed less important actors out of the 102 organizations mentioned (at least once) in the interviews; only actors nominated more than three times were considered in the subsequent analysis (Dörry and Decoville Citation2016; Cappellano and Makkonen Citation2019). For the purpose of this analysis, the authors adopt a very simple metric counting the links of single actors in the networks.

Authors gathered information from official documents, local newspapers and, most notably, expert opinion (discussions with six external experts: three academics and three entrepreneurs) on the most central actors in the CIC region. Based on these, they drafted the roster of organizations to be surveyed/interviewed.

To refine the list, the authors attended official meetings of relevant cross-border arenas. Approaching key organizations’ representatives allowed the authors to heighten the accuracy of the survey sample which was built on the assumption that ‘innovation is strongly promoted by inter-organizational networks formed by organizations of different typology – in particular, firms, institutions and universities’ (Lazzeretti and Capone Citation2016, 5857). The online assisted survey was initially sent to 53 organizations and filled in during interviews held in person or by phone during the summer of 2018. As a result, responses from 40 different organizations (via the survey/interviews) were received leading to a response rate of 75% ().

Table 4. Interviewee per belonging organization type.

6. Results

What is the role of city governments in the CIC?

The engagement of both Seattle and Vancouver in the CIC appears limited. This emerged when reviewing the CIC structure: no cities’ officials appear in sub-committees or in the CIC steering committees. In fact, the only public authorities currently involved are at the state or provincial level. Nevertheless the City of Seattle and the City of Vancouver, B.C. do indeed engage with one anotherFootnote1 on a number of shared interests, which include pressing urban issues such as housing and the environment, but they tend to not coordinate with other actors. Likewise, an expert interviewee admitted: in the ethos of ‘the Cascadia innovation Corridor, there has been a connection between high-level policies, premiers, and so on. In the layers beneath that, we are not that integrated.’

Therefore, the vertical collaborations appear scant and weak, since the city government does not play a central role in the CIC. Accordingly, the authors processed the data collected during the survey campaign through the Social Network Analysis to gauge the embeddedness of the two cities in the CIC. The results reveal the most connected organizations in the region. As shown below (), only the city of Vancouver, B.C. is ranked among the 10 most connected actors. However, its linkages are mainly limited to actors on the Canadian side of the border rather than with U.S. peers.

Table 5. The most connected organizations in the Cascadia CBR based on links with partners from the US, Canadians or actors active in both sides.

The role of multi-national companies outlined above makes the CIC a unique case in the broader cross-border cooperation rhetoric. In fact, Microsoft is the most active participant in the CIC, but also Boeing and, to a lesser extent, Amazon has engaged in this public-private endeavour. A few Canadian public authorities have been found to be central in the network, such as the B.C. Government, the City of Vancouver, B.C. but most notably the Canadian Consulate based in Seattle which appears the most connected on both sides of the border. The two largest universities in the region (University of Washington and University of British Columbia) are demonstrated to be active despite being primarily connected with in-country actors. In line with official documents, business-organizations are central drivers in the CIC as the Business Council of the British Columbia co-leads the initiative.

Is there a coherency between the multiple scales of planning?

The second stage of the research reveals a short-sighted perspective on the economic opportunities to tap into a regional cross-border economic development strategy. Evaluating the ‘inwardness’ of planning policy documents from both cities addressed in this research, there is evidence of a scant interest on border issues, relationships with neighbours on the other side of the international border, and cross-border regional development. Authors reviewed the Regional Growth Strategy ‘Metro Vancouver 2040 Shaping Our Future’Footnote2 in Canada and the ‘Amazing Place: Growing Jobs and Opportunity in the Central Puget Sound Region’Footnote3 concerning the U.S. side of the border. Notwithstanding the two documents having a regional scope which covered multiple counties, only the U.S. strategy considered the CIC and the economic linkages with Vancouver, BC. In fact, the two planning documents reflect that ‘legally embedded spatial planning systems are often blind to what lies outside their jurisdiction’ (Jacobs Citation2016, 4).

During the interview campaign, it emerged that the two city governments had a line of communication regarding municipal topics concerning environments, social housing, and disaster resilience, there was no emphasis on collaboration in the field of economy or infrastructure (e.g. mobility). An official interviewed summarized the relationships among city governments as follows:

The relationships among Vancouver and Seattle City Governments are intense and diverse since the two cities’ officials meet regularly on a monthly basis for talking about a roster of ‘hot’ topics, including: housing, planning, resilience, GHG emission and their impacts in urban areas. The two cities used to collaborate within a few international platforms, including: the Pacific Coast Collaborative (PCC)Footnote4, the 100 Resilient CitiesFootnote5 and others. All in all, we meet regularly officials from [..] City Government in person (2–3 times a year) or on remote (once a month). We achieved the level to understand each other's needs and challenges. Unfortunately, we haven’t succeeded yet to tackle the most urgent matters jointly such as housing, planning, transportation and resilience.

I am not looking for meeting with multi-national companies since they want to compete with me. Our focus is overseas (e.g. EU, Korea). In Washington State there are more investors/competitors than customers. Since their size, they do tend to buy companies in B.C. rather than cooperate with them. It is a matter of size, indeed!

How can the CIC be strengthened to pursue a common territorial strategy to meet societal needs in Cascadia?

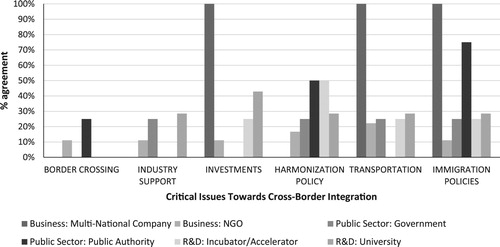

The final part of the survey addressed a few open-questions to gain insights about the interviewees’ expectations from the CIC and, in general, from the cross-border local integration policies. Firstly, the authors asked what could be a game-changer to bolster further integration throughout Cascadia. Results are listed in . Immigration policy was the most commonly identified hindrance, and was rated by all stakeholders as a critical turning point. The lack of mobility for skilled workers to travel across the border in Cascadia is reported also in other studies of the region (e.g. Richardson Citation2016). Transportation also emerged as a ‘hot topic’ for the region. Not surprisingly, private sector stakeholders attributed more attention to this topic as being one of the main CIC sponsors. In this regard, the respondents did not agree on a common strategy to implement. Some commented there is no regional plan to efficiently target this deficiency, advocating for a more comprehensive approach at a regional scale. Conversely, others strongly envision the high-speed train project as a turning point in this regard.

Others (as R&D centres and NGOs) consider the harmonization of policy including regulations concerning trade and business, work permits and foreign policy more broadly. Larger public investments are strongly advocated by private stakeholders, universities, incubators/accelerators and to a lesser extent the NGOs.

Greater private involvement was also advocated as an important component of the CIC. In line with the Microsoft example, a ‘critical mass of companies operating on both sides of the border would be the right trigger’ for tighter integration processes. On the other hand, some interviewees acknowledge there is a need to boost stronger cross-border networks. In particular, it was suggested that tighter collaboration should happen in the field of R&D and business communities where there is – according to the interviewees – a lack of knowledge about the business opportunities on the other side of the border.

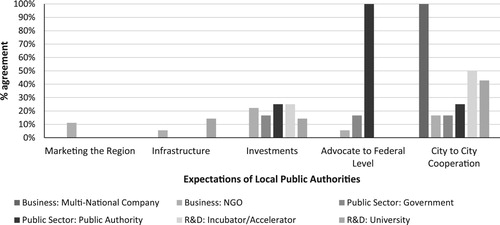

As the focus of the analysis was on planning, the authors asked what interviewees expected local government authorities to be responsible for, regarding the ethos of CIC. Results displayed in reveal that the majority of respondents would welcome tighter relationships (and a stronger commitment) among the cities. In fact, several interviewees remarked the need to build networks from the bottom up, such as, ‘Better established platforms for continued cross-border communication and collaboration’. Besides building networks with other peers, local authorities are asked to facilitate

many forums and events to bring the communities and the community leaders together and work together to listen and find out the challenges and things coming in the way, so that they can help address it. Such initiative requires that kind of coordination, private entities cannot facilitate this on their own.

Additionally, respondents encourage local authorities to brand the region internationally as a whole Cascadia region. The region has seen some success with a binational tourism strategy, by leveraging special offers to attract tourists throughout Vancouver, Seattle and Portland based on the ‘two nation vacation’ model, originally spearheaded by the Discovery Institute in the 1990s.

The second question concerned what interviewees expect to be the role of public local authorities in the CIC ethos to increase this initiative’s effectiveness. The authors coded the interview results and ‘weighted’ the results taking into account the number of each category of interviewees. As shown in , interviewees suggest that city councils establish more structured cooperation in order to raise the effectiveness of the CIC. This seems to be in line with the new partnership signed by the Seattle and Vancouver B.C. city governments to boost economic development. The second most urgent task is to advocate regional issues at the federal scale, while investments are also considered a compelling priority.

Private stakeholders privilege heightened cooperation at the city level, while other business-oriented actors consider all issues to be critical for the CIC with a slight emphasis on public-funded investments. The R&D actors privilege investments and infrastructure along with more city cooperation. Public authorities starkly prefer embarking on lobbying at federal/national levels.

Based on these findings, the authors summarized the results of the analysis in the .

Table 6. Research outcomes.

7. Conclusions

This article uses the case study of the Cascadia Innovation Corridor to explore the concept of Cross Border Regional Planning (CBRP), taking into account the coordination (or lack thereof) between multiple scales of planning. The CIC case study elaborates the important role of actors at the local level and the value of strengthening the interplay between spatial planning and economic growth in border regions. The relevance of this case study is threefold:

it represents a unique border region where private stakeholders have been playing a pivotal role in driving more cross-border cooperation (CBC) informing planning infrastructure (e.g. the High Speed rail project);

it makes the case for a larger cross border regional planning initiative (e.g. CIC) which targets an ambitious economic goal to make Cascadia a tech-hub of global significance;

despite a very fragmented political climate between the two countries, the regional actors continue to actively cooperate, acknowledging mutual benefits from deepened CBC.

While still nascent, the CIC is gaining momentum, becoming a more visible and consolidated effort, and achieving some tangible results. As mentioned previously, the CIC builds on a history of cross-border collaboration in the region, and has already benefited from the ‘culture of collaboration’ that exists in the region (Friedman, Conteh, and Phillips Citation2019). Interestingly, the advancement of the CIC since its inception in 2016, occurred alongside deteriorating bi-national relations at the federal scale between the U.S. and Canada. This divergence in policy collaboration between scales further underscores the immense value of regional planning efforts, particularly in a cross-border environment. The strength and validity of the cross-border organizational infrastructure in the region, combined with leadership at the state and provincial scale, has deepened cross-border ties between B.C. and Washington, despite major political and economic tensions (and in spite of the barriers associated with federal jurisdiction mentioned previously).

Despite these accomplishments, the CIC initiative has yet to establish a common vision for further regional development. This analysis shows that the two sides of the border still overlook one another in their development strategies. The ‘horizontal’ collaborations among the cities – regarded successful in other cross-border studies (Van den Broek and Smulders Citation2015) – are weak and limited in the case of Seattle and Vancouver. This may be shifting, however. In October 2019 the two city governments signed a partnership for boosting economic development.Footnote6 In fact, the role of cities is still marginal and this hints at a discrepancy between soft and hard planning (Zimmerbauer Citation2018) proved also by analyzing planning documents. This appears consistent with other bi-national planning experiences along the U.S. – Canadian border (Bradbury Citation2016). The interviewees acknowledge this aspect as a possible catalyst for further economic cross-border integration. Furthermore, a stronger interplay between the regional and city levels is highly advocated to enhance the effectiveness of the CIC to drive more CBC in the region.

The majority of the impediments to tighter cooperation in Cascadia pertain to federal level jurisdiction, which highlights the challenges of CBRP. Many interviewed were of the impression that US immigration policy, implemented after 9/11, constituted a severe barrier to the flow of people across the border

All in all, the CIC is still advocating for the high-speed rail project as a concrete action to address public transportation needs, mirroring many other examples in this field: namely, the Oresund Bridge between Sweden and Denmark or the tramway line from Strasbourg to the Kehl city in Germany (Durand and Decoville Citation2018). Still, there is room for improving the CIC by including a more holistic approach to cross-border spatial planning in a continued effort to shape public policy and service delivery around communities’ needs and places (Braunerhielm, Alfredsson, and Medeiros Citation2019). This includes branding the region as a whole Cascadia region to lure more private companies into the cross-border cooperation (CBC) process. Local institutions should set the ground for a more inclusive approach towards the CBC process by inviting NGOs, private stakeholders and the community to participate at bi-national forums. This has proved effective to create a shared vision for other border regions (see Tijuana & San Diego case in Cappellano and Makkonen Citation2019). Transportation projects should work towards reducing travel time from Seattle to Vancouver. To this end, the opening of the sea-plane service represents a tangible milestone in the process. The high-speed train would address this importantly perceived issue, but also would contribute as a ‘land-mark’ to brand the region as a tech-hub on the global stage.

Moreover, border infrastructure needs to be updated in order to diminish border crossing time. In this regard, technology-based programmes – such as NEXUS or mobile passport apps – can play a broader role to expedite the time spent at the ports of entry.

This study contributes to the wide rhetoric concerning cross-border cooperation (CBC) and more specifically to planning in border regions by proposing the CBRP, which includes: (a) the combination of economic growth and planning in driving development in border regions with the added element of a regional cross border steering secretariat that is also dedicated to more altruistic binational regional needs such public transportation, higher education, affordable housing, and food security; (b) a larger geographical scope which is more in line with current innovation policy discourses rewarding the regional scale as a primary scale for policy design. The Cascadia Innovation Corridor engages actors (+300 km distant each other) in a regional scale which in Europe is covered only by the EU Macro-Regions where the Member States take the leading role; (c) the nested scale of multi-level governance arrangements which attempts to cover the transnational, national, regional, sub-regional, and finally local actors, who are usually left off the roster of more traditional transnational planning practices and; (d) the added value of engaging champion private stakeholders committed to playing a key partnership role in addressing these contemporary cross-border issues, which reach beyond the purely economic.

Based on manifold strands of literature, the CBRP concept is presented to assess the CIC effort in this Cascadia region. Cautiously, it could be adopted in other studies to test its potential explanatory power in other cross-border regions.

Acknowledgements

This paper was presented at the Association for Borderland Studies Conference in San Diego in April 2019. Special thanks must go to Prof. Teemu Makkonen, Dr. Natalie Baloy, and Dr. Annalisa Rizzo for their invaluable feedbacks on an earlier version of this paper. The authors credit the Editor and two anonymous referees for their contribution.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The two cities signed an MoU in 2016 which has been updated in 2018.

2 The document has been adopted in 2017. Metro Vancouver is a federation of 21 municipalities, one Electoral Area and one Treaty First Nation that collaboratively plans for and delivers regional-scale services. Its core services are drinking water, wastewater treatment and solid waste management. Metro Vancouver also regulates air quality, plans for urban growth, manages a regional parks system and provides affordable housing. The regional district is governed by a Board of Directors of elected officials from each local authority.

3 The document has been issued in 2011 and later updated in 2017. It is released by the Puget Sound Regional Council which convenes its members from King, Pierce, Snohomish and Kitsap counties in Washington State. The role of the regional Council is to design policies and coordinates decisions about regional growth, transportation and economic development planning within those counties. King County hosts the City of Seattle.

4 Please see http://pacificcoastcollaborative.org/.

5 Please see http://www.100resilientcities.org/.

References

- BC Technology. 2019. “Cascadia Innovation Corridor Announces New Steering Committee for Promoting Cross-Border Growth in Cascadia Region.” https://www.bctechnology.com/news/2018/9/18/Cascadia-Innovation-Corridor-Announces-New-Steering-Committee-For-Promoting-Cross-Border-Growth-in-Cascadia-Region.cfm.

- Border Policy Research Institute. 2018. “Regional Cross-Border Collaboration Between the U.S. & Canada.” Border Policy Research Institute Publications. https://cedar.wwu.edu/bpri_publications/113.

- Bradbury, S. L. 2016. “Making Connections and Building Bridges: Improving the Bi-National Planning Process.” International Planning Studies 21 (1): 64–80. doi:10.1080/13563475.2015.1114450.

- Braunerhielm, L., O. E. Alfredsson, and E. Medeiros. 2019. “The Importance of Swedish–Norwegian Border Residents’ Perspectives for Bottom-Up Cross-Border Planning Strategies.” Norsk Geografisk Tidsskrift - Norwegian Journal of Geography 73 (2): 96–109. doi:10.1080/00291951.2019.1598485.

- British Columbia–Washington MOU. 2016. “ British Columbia–Washington MOU [PDF].” https://news.gov.bc.ca/files/BC_WA_Innovation_MOU.pdf.

- Caesar, B. 2017. “European Groupings of Territorial Cooperation: A Means to Harden Spatially Dispersed Cooperation?” Regional Studies, Regional Science 4 (1): 247–254. doi:10.1080/21681376.2017.1394216.

- Cappellano, F., and T. Makkonen. 2019. “Cross-Border Regional Innovation Ecosystems: The Role of Non-Profit Organizations in Cross-Border Cooperation at the US-Mexico Border.” GeoJournal, 1–15. doi:10.1007/s10708-019-10038-w.

- Cappellano, F., and T. Makkonen. 2020. “The Proximity Puzzle in Cross-Border Regions.” Planning Practice & Research 35 (3): 283–301. doi: 10.1080/02697459.2020.1743921

- Cappellano, F., and A. Rizzo. 2019. “Economic Drivers in Cross-Border Regional Innovation Systems.” Regional Studies, Regional Science 6 (1): 460–468. doi:10.1080/21681376.2019.1663256.

- Clarke, S. 2000. “Regional and Transnational Discourse: The Politics of Ideas and Economic Development in Cascadia.” International Journal of Economic Development 2 (3): 360–378. doi:10.1057/978-1-137-39617-4_6.

- Decoville, A., and F. Durand. 2017. “Challenges and Obstacles in the Production of Cross-Border Territorial Strategies: The Example of the Greater Region.” Transactions of the Association of European Schools of Planning 1 (1): 65–78. doi:10.24306/TrAESOP.2017.01.005.

- Deppisch, S. 2012. “Governance Processes in Euregios. Evidence From Six Cases Across the Austrian–German Border.” Planning Practice and Research 27 (3): 315–332. doi:10.1080/02697459.2012.670937.

- Dörry, S., and A. Decoville. 2016. “Governance and Transportation Policy Networks in the Cross-Border Metropolitan Region of Luxembourg: A Social Network Analysis.” European Urban and Regional Studies 23 (1): 69–85. doi:10.1177%2F0969776413490528 doi: 10.1177/0969776413490528

- Durand, F. 2014. “Challenges of Cross-Border Spatial Planning in the Metropolitan Regions of Luxembourg and Lille.” Planning Practice and Research 29 (2): 113–132. doi:10.1080/02697459.2014.896148.

- Durand, F., and A. Decoville. 2018. “Establishing Cross-Border Spatial Planning.” In European Territorial Cooperation, edited by E. Medieros, 229–244. Cham, Switzerland: Springer.

- Falkheimer, J. 2016. “Place Branding in the Øresund Region: From a Transnational Region to a Bi-National City-Region.” Place Branding and Public Diplomacy 12 (2-3): 160–171. doi:10.1057/s41254-016-0012-z.

- Fricke, C. 2015. “Spatial Governance Across Borders Revisited: Organizational Forms and Spatial Planning in Metropolitan Cross-Border Regions.” European Planning Studies 23 (5): 849–870. doi:10.1080/09654313.2014.887661.

- Friedman, K., C. Conteh, and C. Phillips. 2019. “Cross-Border Innovation Corridors: How to Support, Strengthen and Sustain Cross-Border Innovation Ecosystems.” Brock University: Niagara Community Observatory Policy Brief (September). https://brocku.ca/niagara-community-observatory/policy/.

- Ganster, P., and K. Collins. 2017. “Binational Cooperation and Twinning: A View From the US–Mexican Border, San Diego, California, and Tijuana.” Baja California. Journal of Borderlands Studies 32 (4): 497–511. doi:10.1080/08865655.2016.1198582.

- Herzog, L. A. 2000. “Cross-Border Planning and Cooperation.” In The US-Mexican Border Environment: A Road Map to a Sustainable 2020, edited by P. Ganster, 139–161. San Diego, CA: San Diego State University Press.

- Jacobs, J. 2016. “Spatial Planning in Cross-Border Regions: A Systems-Theoretical Perspective.” Planning Theory 15 (1): 68–90. doi:10.1177%2F1473095214547149 doi: 10.1177/1473095214547149

- Knippschild, R. 2011. “Cross-Border Spatial Planning: Understanding, Designing and Managing Cooperation Processes in the German–Polish–Czech Borderland.” European Planning Studies 19 (4): 629–645. doi:10.1080/09654313.2011.548464.

- Konrad, V. 2015. “Evolving Canada - United States Cross-Border Mobility in the Cascade Gateway.” Research in Transportation, Business and Management 16: 121–130. doi:10.1016/j.rtbm.2015.08.004.

- Lazzeretti, L., and F. Capone. 2016. “How Proximity Matters in Innovation Networks Dynamics Along the Cluster Evolution. A Study of the High Technology Applied to Cultural Goods.” Journal of Business Research 69 (12): 5855–5865. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.04.068.

- Lundquist, K. J., and M. Trippl. 2013. “Distance, Proximity and Types of Cross-Border Innovation Systems: A Conceptual Analysis.” Regional Studies 47 (3): 450–460. doi:10.1080/00343404.2011.560933.

- Marcu, S. 2011. “Opening the Mind, Challenging the Space: Cross-Border Cooperation Between Romania and Moldova.” International Planning Studies 16 (2): 109–130. doi:10.1080/13563475.2011.561056.

- Noferini, A., M. Berzi, F. Camonita, and A. Durà. 2019. “Cross-Border Cooperation in the EU: Euroregions Amid Multilevel Governance and Reterritorialization.” European Planning Studies 28 (1): 35–56. doi:10.1080/09654313.2019.1623973.

- Office of the Governor. 2016. “British Columbia, Washington State to Create Cascadia Innovation Corridor to Promote Regional Economic Opportunities in Tech Industries.” News, September 20. https://www.governor.wa.gov/news-media/british-columbia-washington-state-create-cascadia-innovation-corridor-promote-regional.

- Oliveira, E. 2015. “Constructing Regional Advantage in Branding the Cross-Border Euroregion Galicia–Northern Portugal.” Regional Studies, Regional Science 2 (1): 341–349. doi:10.1080/21681376.2015.1044020.

- Peña, S. 2007. “Cross-Border Planning at the U.S.-Mexico Border: An Institutional Approach.” Journal of Borderlands Studies 22 (1): 1–18. doi:10.1080/08865655.2007.9695666.

- Public Safety Canada. 2008. Canada’s First Enhanced Driver’s Licence Launched in BC. News Release. https://archive.news.gov.bc.ca/releases/news_releases_2005-2009/2008OTP0008-000056.htm.

- Pupier, P. 2019. “Spatial Evolution of Cross-Border Regions. Contrasted Case Studies in North-West Europe.” European Planning Studies 28 (1): 81–104. doi:10.1080/09654313.2019.1623975.

- Richardson, K. 2016. “Attracting and Retaining Foreign Highly Skilled Staff in Times of Global Crisis: A Case Study of Vancouver, British Columbia’s Biotechnology Sector.” Population, Space and Place 22 (5): 428–440. doi:10.1002/psp.1912.

- Richardson, K. 2017. Knowledge Borders: Temporary Labor Mobility and the Canada–US Border Region. Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Scott, J. W. 1999. “European and North American Contexts for Cross-Border Regionalism.” Regional Studies 33 (7): 605–617. doi:10.1080/00343409950078657.

- Sparke, M. 2000. “Excavating the Future in Cascadia: Geoeconomics and the Imagined Geographies of a Cross-Border Region.” B.C. Studies: The British Columbian Quarterly 127: 5–44.

- Todd, D. 2008. Cascadia the Elusive Utopia: Exploring the Spirit of the Pacific Northwest. Vancouver, BC: Ronsdale Press.

- Van den Broek, J., and H. Smulders. 2014. “Institutional Gaps in Cross-Border Regional Innovation Systems: The Horticultural Industry in Venlo–Lower Rhine.” In The Social Dynamics of Innovation Networks, edited by R. Rutten, P. Benneworth, D. Irawati, and F. Boekema, 157–175. London: Routledge.

- Van den Broek, J., and H. Smulders. 2015. “Institutional Hindrances in Cross-Border Regional Innovation Systems.” Regional Studies, Regional Science 2 (1): 116–122. doi:10.1080/21681376.2015.1007158.

- Wilson, K. 2020. “Governing the Salish Sea.” Hastings Environmental Law Journal 26 (1): 169–162.

- Zimmerbauer, K. 2018. “Supranational Identities in Planning.” Regional Studies 52 (7): 911–921. doi:10.1080/00343404.2017.1360481.